Abstract

Chinese geographic imaginaries such as the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) are increasingly treated as taken-for-granted political concepts. The political language pertaining to BRI now overlaps, and interacts with, established narratives of geographic space. In this analysis, we focus on Beijing’s diplomacy, as well as scholarly and official discourse, with the aim to locate Chinese representations of the ‘South’ or understanding(s) of ‘developing’ regions within what we describe as China’s global connectivity politics. In this context, we show that instead of developing a fixed perspective on the ‘South’, the idea of the ‘Global South’ or ‘South–South’ cooperation, Chinese discourse increasingly defines the ‘South’ based on countries’ responses to, or role within, Beijing’s political initiatives and regional dialogue platforms. The Chinese reconfiguration of the geographic scope of the South therefore extends to Central and Eastern Europe and, possibly, beyond. Beijing exerts discourse power by categorising countries of the ‘South’ as being located relationally to China. This reframing, or broadening, of the idea of the ‘South’ also produces a less dichotomous differentiation between developed and developing states (a dichotomy which Beijing tries to avoid).

What role does the idea of the ‘South’ (still) play within broader developments of contemporary Chinese foreign policy? Based on a qualitative analysis of Chinese policy documents, academic writing and diplomatic practices as they change through time, we argue that in China’s foreign policy discourse the ‘South’ has been progressively reconfigured: Beijing’s interpretation of the South has increasingly become a function of its overarching ‘connectivity politics’. The latter is here understood as an approach to diplomacy and foreign policy that aims to proactively connect the rest of the world to China while only selectively integrating with existing international norms and principles.Footnote1 Hence, for Chinese leaders, the ‘South’ – and membership therein – has become less defined according to geographical north–south dichotomies or socio-economic parameters that traditionally inform dominant conceptualisations of the ‘Global South’ in many international organisations. Beijing’s view of the South has become increasingly vague and is ‘global’ in the sense that the South is less a description of its members than it is a manifestation of a type of diplomacy – a particular relationship with China – which allows Beijing to wield proactive agenda-setting power and connect the world to China.

While recognising that Chinese academic ruminations as well as official diplomatic rhetoric contain multiple overlapping (and contending) conceptualisations of the South, we emphasise the importance of an increasingly flexible South/non-South dichotomy. Due to this increasing vagueness, the South/non-South dichotomy might eventually dissolve within the greater logic of connectivity politics that we discuss throughout this article. For now, however, we recognise that foreign policy elites in Beijing frequently work with a conceptualisation of the South that is, on the one hand, tied to China’s long-term self-perception of being a primus inter pares among developing nations, and, on the other hand, based on the assumption that an increasingly large ‘circle of friends’ can be engaged according to the diplomatic toolbox stemming from China’s experiences with South–South relations.Footnote2

Thus, our interpretation of the conceptual realm of China’s take on the ‘South’ goes beyond how China’s South–South relations are normally described. With regard to the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), for example, observers like Timothy R. Heath remind us that ‘Chinese authorities insist any country can become a partner, but a closer look at official statements makes clear that the real aim is to build a political coalition of developing countries’ (RAND Blog, October 8, 2018, https://www.rand.org/blog/2018/10/what-does-chinas-pursuit-of-a-global-coalition-mean.html). While we agree with Heath’s depiction of Chinese official statements, we interpret them somewhat differently and argue that basically any country, rich or poor, can now join said coalition and ‘become a partner’ insofar as it accepts the Beijing-centred vision of diplomatic relationships that China expects to have with the developing world and, consequently, at least partially acquiesces to China’s proposal for a new meta-geography of the world.

In the remainder of this article, we first differentiate the BRI framework from what we call the meta-geography of China’s connectivity politics. Based on this, we discuss how Chinese representations of (global) space have changed in China’s foreign policy discourse under Xi Jinping and dissect the meaning of the ‘South’ in its relation to China’s connectivity politics. In the second part of the article we then portray how connotations of China’s long-standing emphasis on ‘being a developing country’ are slowly being transformed by novel formulations such as ‘a new (type of) South–South cooperation’. Overall, we argue that Beijing’s foreign policy elites have been re-categorising the ‘South’ as being located relationally to China. Beijing’s current view of the ‘South’ is hence tied to a less dichotomous differentiation between developed and developing states.

The ‘South’ in Beijing’s connectivity politics

As introduced by Martin Lewis and Kären Wigen, the notion of meta-geography stands for ‘the set of spatial structures through which people order their knowledge of the world’Footnote3 and is a way to grasp the emergence and persistence of global structures and their geographical imaginaries (e.g. East/West, North/South). As Beijing’s overarching approach of connectivity politics is in full swing around the world,Footnote4 this article looks at Chinese political practice and accompanying academic discourse in order to locate therein the role and evolution of distinctly Chinese representations of the ‘South’, the ‘Global South’ and ‘South–South’ cooperation as well as related geopolitical notions of ‘developing’ states and regions. Meta-geographies are particularly powerful because they ‘lose their specific spatial coordinates and become imbued with extraneous conceptual baggage’ (such as ‘discussions of Japan as [a] Western nation’).Footnote5 From Beijing’s perceptive, however, the ‘South’ is more than just a mirror image of the Washington-led ‘West’. Beijing’s ‘South’ manifests itself less through a common denominator of political values or institutional similarities and more by means of diplomatic practice and symbolism – in particular, relations towards Beijing.

It is hence important to differentiate between the rather concrete and often more regionally limited geographical ideas pertaining to the BRI – i.e. its corridors, sea lanes and hubs – and a broader, more abstract meta-geography of connectivity politics that can – potentially – serve as a framework of sense-making for China’s relations with every state in the world. In this regard, it is worth emphasising that in our reading of publicly available accounts, the language and ideas associated with corridors and hubs has had a rather superficial impact on the thinking of Beijing’s foreign policy elites. Instead, what matters in the minds of strategists and academics is the emergence of a global meta-geography of connectivity, which shows itself through a particular bilateral diplomatic connection – one in which China reproduces its relationships with the South at a global level. This relationship is frequently (though not exclusively) symbolised by BRI memoranda.

Importantly, the argument put forward in this article denies neither the prowess of China’s smaller, regio-spatial narratives nor their interrelatedness with the emerging meta-geography we are outlining. Indeed, the self-promotion as a ‘hub’ of the BRI by some countries illustrates this latter point as much as the actions by governments and citizens who find themselves in a position of having to interpret, participate in or resist Chinese geographic imaginaries. In this sense, it is beyond the scope of this article to inquire into the actual acceptance and internalisation of specific geographical ideas. Here, our contribution is limited to pointing out how the notion of the South is re-interpreted by Chinese actors and thereby lies at the heart of China’s own emerging model for a global meta-geography; hence, we specifically focus on diplomatic practices in the context of South–South relations. Seen through the broader prism of connectivity politics, the idea of the South is more than just another time-tested rhetorical resource that Beijing’s leaders can mobilise en route to fashioning an international system more compatible with China’s authoritarian one-party state.Footnote6 The conceptual trajectory of the term shows how, from China’s perspective, the South has long been a space in which Beijing could claim a leadership role and inculcate acceptance thereof. As China becomes richer and more powerful, its leaders are beginning to apply the mechanisms and logic of their engagement with developing countries to the rest of the world.

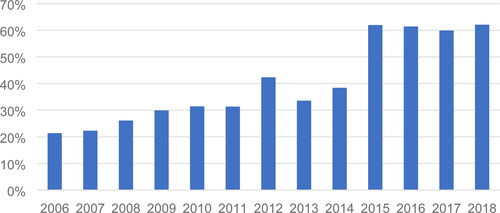

Beijing’s view of the ‘South’ thus matters in two different ways: First, Beijing’s policies and diplomacy towards developing countries can be seen as the forerunner of its broader connectivity strategy that is now potentially compatible with any other country. Instead of coming up with a geographically fixed (and thus insufficient) definition of the South, it is therefore more important to analyse how the South is used in China’s foreign policy discourse. Second, the idea of the South and South–South relations not only matters as a rhetorical resource vis-à-vis long-standing partners but is (still) evoked as a spatial realm in which connectivity politics can unfold. Consequently, the notion of the South should not be considered to represent, by itself, a dominant meta-geography of China’s foreign policy discourse. Rather, as both a blueprint for and a vehicle of Chinese connectivity endeavours, the South is becoming an ever more expansive notion that (rhetorically) merges with the discourse of global connectivity. China’s foreign policy elites do so by means of at least three rhetorical and diplomatic strategies that will be further discussed below. Firstly, official statements often blur the differences and boundaries between ‘South–South’ and ‘North–South’ cooperation, or juxtapose these notions. Chinese commentators like to describe Xi Jinping’s BRI as ‘realizing the unification of “South–South Cooperation” and “South–North Cooperation”’ (Study Times, February 26, 2018), echoing the leaders’ communique of the 2017 BRI Forum, which listed ‘advancing North–South, South–South, and triangular cooperation’ as its major objective. Incidentally, fewer and fewer Chinese academics still write pieces in which ‘North–South relations’ are studied on their own – without reference to ‘South–South relations’ (see ).

Figure 1. Percentage of Chinese articles mentioning ‘North–South relations’ that also cite ‘South–South relations’.

Authors’ compilation of data gathered via CNKI China Knowledge Resource Integrated Database China Academic Journals Full-text Database. Accessed July, 2019.

Secondly, the conceptual opposite of the ‘South’ or even of ‘developing countries’ is more and more vaguely defined (see below). Thirdly, in Chinese political discourse, numerous China-centric multilateral mechanisms (particularly regional ‘China + X’ forums) have been promoted under the label of South–South relations, even though some of its members are not traditionally subsumed under the moniker of developing countries nor do they self-identify as such. Moreover, what matters for many Chinese scholars is the particular centrality of China in these arrangements. In the words of Wang Yiwei, one of Beijing’s most prominent academic commentators, China is now a ‘super-developing-country’ (超级发展中国家), that ‘can become the bridge or the link between developed and developing countries, just as the BRI is both South–South and North–South cooperation’ (Huanqiu, 15 August, 2019, http://opinion.huanqiu.com/hqpl/2019-08/15302790.html?agt=15422; emphasis added). What hence emerges is the underlying logic of Beijing’s increasingly dominant meta-geography of connectivity, in which the South is neither a major identity nor a major objective – but conceptually resonates as a space in which China can legitimately project and claim a ‘guiding role’ (引领作用).Footnote7 Centrally, this meta-geography implies a new way to order the location and positioning of states in the international system based on a willingness to connect (politically, economically, technically) with China – on Chinese terms. Along these lines, numerous scholars among Beijing’s foreign policy circles now speak of a ‘new type of South–South Cooperation that has as its objective the creation of a Community of Common Destiny’,Footnote8 the latter being the official Chinese Communist Party (CCP) phraseology for an ideal-type world that is fully connected to – and thus wholly compatible with – the PRC.

China’s shifting spatial representations of the global

Since Xi Jinping’s announcement of the Silk Road Economic Belt and the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road – now jointly known as the ‘Belt and Road Initiative’ – scholars have noted that ‘[m]ultiple actors are in the process of creating diverse and interrelated geographies in these twin multi-scalar projects’.Footnote10 Though not always directly tied to the BRI, China’s growing political emphasis on new ‘corridors’ (走廊), technical and regulatory ‘ecosystems’ (生态圈/生态系统), ‘hubs’ and ‘fulcrums’, in conjunction with the financing of new transport links, has invigorated cooperation and competition between neighbours; for some, such as Georgia or Kazakhstan, in order to take advantage of the BRI;Footnote11 for others, like India, to hedge against it.Footnote12 In consequence, new cohorts of area studies scholarship are now ‘tracing the shifting geo-visions’.Footnote13 Some, for instance, point to the impact of infrastructure on geography and are searching for ‘glimpses into the techno-political construction of Eurasia in an age of massive infrastructural investments’.Footnote14

A particularly influential example of Beijing-driven concepts of geographic space is the ‘China–CEEC’ initiative, which links a group of Central and Eastern European Countries (CEEC) to China. This expanding regional grouping includes members of the European Union (EU) as well as non-EU members. The China–CEEC cooperation initiative was originally called ‘16 + 1’, but since the addition of Greece in early 2019, the moniker ‘17 + 1’ has also been used to reflect the increased number of participating states (New York Times, 12 April, 2019). Since its inception in 2012 (i.e. prior to BRI), the format has seen a quick growth in sub-institutions, associations and the like.Footnote15 Yet various scholars have observed that the foundational institutional design of China–CEEC – including its secretariat in Beijing – provides asymmetrical advantages to the Chinese side. Some authors hence view it as ‘a platform for sixteen [now seventeen] bilateral relationships with Beijing’ Footnote16 that shifts the ways of ‘political deal making’Footnote17 towards Chinese standards. Hence, not least because of conflicting EU and Chinese public procurement standards,Footnote18 China–CEEC has encountered much criticism in Brussels and other Western European capitals. It has become the go-to example for accusations regarding Beijing’s divide et impera politics towards EuropeFootnote19 and the challenge it poses to the politico-spatial conceptualisation of the European continent.

Notably, the China–CEEC mechanism had long been treated as a mechanism of ‘South–South Cooperation’ by Chinese leaders. Acknowledging the higher per-capita income levels in some Eastern European countries, this was slightly modified around 2016 when Xi Jinping and other leaders called it ‘a new platform for South–South cooperation with the characteristics of North–South cooperation’ (People’s Daily, November 27, 2015), and the public classification of China–CEEC as ‘South–South cooperation’ has since been muzzled. Yet this did not happen because the Chinese side thought otherwise, but arguably because the European partners felt that the moniker was not appropriate.Footnote20 Foreshadowing the argument of this paper, Chinese think tank researchers continue to emphasise that in spite of established economic metrics that define what normally counts as ‘developing’, these European countries and diplomatic mechanisms should still be subsumed under China’s ‘collective diplomacy for developing regions’ (发展中地区整体外交).Footnote21 According to this reasoning, some internal factors of the region in question may be considered (e.g. that these 17 countries tend to be economically inferior relative to other states on the European continent), but it is also maintained that such a framing is applicable because ‘in its cooperation with China they are treated as one complete unit’ (与中国的合作中被当作一个整体对待).Footnote22 In other words, in this strand of Chinese political thinking, Beijing’s conceptualisation of the geographic scope of the ‘South’ is tied to – and reproduced by – a category of diplomatic practices and exchanges. The implemented mode of (group) diplomacy is seen as a central constitutive element to an imagined geographic space or region of ‘development’. ‘China–CEEC’ is seen as a ‘southern’ mechanism because it works analogously to other regional forums with developing countries that are defined relationally to China, i.e. by a group of states’ relationship with the PRC in which Beijing still yields asymmetrically strong agenda-setting power. This is exacerbated by the fact that regional initiatives such as the ‘China–CEEC’ often overlap with existing regional mechanisms and produce new spatial groupings that fit into China’s overall politics of global connectivity. Hence, as an analytical category, ‘South’ can potentially be applied to any state around the globe.

Such shifts in Beijing’s political representation of the global can also be found in other contexts, most notably BRI. China’s leaders have continually added new spatial or conceptual dimensions (such as ‘arctic’ or ‘digital’ silk roads) to the initiative, and most scholars agree that BRI should now be treated as having ‘potentially global reach’.Footnote23 Elsewhere we have shown in some detail that, since 2014, references to BRI as a bundle of regional ‘neighbourhood’ initiatives have decreased. Footnote24 Instead, BRI and the often-associated regional mechanisms have been progressively used to indicate a more global scope of Chinese foreign policy. China now increasingly makes its own suggestions to define the reference point of the ‘global’. For instance, over many years China has come to present and define itself as an ‘Arctic stakeholder’.Footnote25 China is now among a group of governments that are ‘imagining themselves as ‘near-Arctic’ states’, thereby actively pushing the concept of a ‘global Arctic’.Footnote26 This position better aligns with China’s interests in fishing, transport and resource exploitation, and is shared with some other states whose territorial positions inhibit direct claims to the Arctic. Similarly, under the global banner of a ‘community of common destiny for humankind’, Beijing increasingly juxtaposes its own concept to the notion of ‘international community’ in deliberative bodies of the United Nations (UN).Footnote27 It is no coincidence that these various new Chinese visions and reference points of the ‘global’ emerge at the same time as Beijing’s connectivity initiatives gather steam.

Finding the South in China’s connectivity politics

What becomes apparent is that any endeavour to locate the South – or the notion of a ‘Global South’ – in Beijing’s foreign policy must happen against the backdrop of China’s own meta-geography. The perspective of ‘connectivity politics’ (Konnektivitätspolitik) – understood as a combination of political visions and strategies that go far beyond the realm of infrastructure – can be a helpful approach to systematically study China’s current logic of foreign policy. Elsewhere we have shown through corpus-linguistic analyses of English translations of Chinese foreign policy speechesFootnote28 how ‘connectivity’ became a collective representative of the discourse on BRI and foreign policy in general. So far, it has been the key foreign policy term of the Xi Jinping era, whose (statistical) significance has consistently grown with each passing year. Taking a closer look at the terms that most frequently collocate with ‘connectivity’ (such as cooperation, infrastructure, development, trade or projects) a multi-dimensional pattern of geographical, financial, political and technological relationality becomes visible.Footnote29

The framework of Konnektivitätspolitik is based on our reading of Beijing’s supposition that connectivity is not only a form of power, but the central instantiation of power in world politics of the twenty-first century. In other words, Beijing holds the view that the country which gains control over (existing and future) connectivity resources also gains the power to (re)shape the space and contours of international politics. China’s approach reflects an understanding of connectivity as organic and multidimensional, which is mirrored by Chinese leadership aspirations in sectors particularly relevant for technical and scientific innovation. The idea of connectivity-as-power is therefore not another take on network theory, even though many of China’s decision makers probably suffer from the same kind of ‘pathological sovereignty’ that network models have been criticised for.Footnote30 Contrary to the idea of networks, connectivity politics involves a particular emphasis on (re-)activating or creating (new) boundaries and territorial entities; consequently, nodes and spaces of networks are not taken for granted. In contrast to network theory, connectivity politics is based on a differentiated account of types and modalities of relations and connections. In this sense, connectivity politics is not so much about the distinct thematic clusters of connectivity that are often showcased in ‘Belt and Road’ public relations materials, but ‘the interactions between the dimensions of different technological layers and geographic spaces, such as economic corridors, supply chains, transit regions and cities, underwater cables, mobile networks and satellites’.Footnote31 In the context of BRI, one of many Chinese academic commentaries dealing with these multidimensional interactions emphasises, for example, the amalgamation of ‘three networks, one zone and one chain’ (三网一区一链). This overlap represents an integrated development approach for the transportation network, the energy network and the information network that together shape an industrial agglomeration area that is part of one international supply chain.Footnote32 Following this logic, the construction of interconnected ecosystems leads to new geographic and political spaces.

From Beijing’s perspective, ‘developing countries’ are crucial counterparts for these types of connectivity politics. With regard to China’s Beidou satellite system, for instance, scholars have already outlined how Beijing is incentivising BRI countries to use Beidou receivers. At least in the case of Thailand, the latter have been ‘funded mostly by Beijing as part of its foreign aid program’.Footnote33 The understanding that digital systems tend to quickly scale up and often result in quasi-monopolistic ecosystems has had Beijing scrambling to introduce a wide range of technology within China and beyond,Footnote34 from smart-port technology to digital payment systems like Alipay (支付宝). Packaged together with BRI loans and grants, an increasing number of BRI memoranda now explicitly include e-commerce agreements (China Daily, August 2, 2017; Xinhua, November 10, 2018; Xinhua, May 16, 2017; ERR, November 27, 2017). In other words, the markets of developing countries are seen as key arenas for the introduction of Chinese innovations and industrial standards en route to fully globalising them (Washington Post, 10 June 2019, https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2019/06/10/what-do-we-know-about-huaweis-africa-presence/).

Yet the creation of ecosystems is not only technical. Developing countries are seen as important partners and amplifiers for globally projecting Chinese ideas. Proactivity (主动性) in establishing connective platforms is therefore a key aspect in the playbook of the Chinese government, notably to make sure that potential asymmetries favour China. Importantly, this does not mean that these platforms have to be new. Since China’s recent embrace of connectivity politics, many existing platforms have been re-awakened, deepened and reframed. Connectivity politics does hence not exclude those mechanisms that are generally associated with a ‘liberal order’, such as participation in World Bank initiatives, the G20 club or various bodies of the UN system. All of them represent ways to amass connectivity resources. We thus approach ‘connectivity with’ as an analytical counterpoint to ‘integration into’ the liberal order, not least because Beijing is conscious of the fact that by mere participation in international affairs, China’s own clout and size almost automatically reshape the general understanding of what constitutes the international order and its underlying principles. Evan Feigenbaum has made a very similar argument, arguing that ‘Beijing’s revisionism and demands for change often play out within the existing international framework’, as ‘China accepts most forms but not necessarily our preferred norms’.Footnote35 Thus, the popular argument focussing on Beijing’s ‘parallel’ international institutions misses the point. As long as the institutions and forums in question allow Beijing to act with proactivity, the maxim ‘a lot helps a lot’ applies to its connectivity politics.

This logic manifests itself below, and beyond, the level of leadership summits in China’s regional forum diplomacy. China has shored up and increased the versatility of a number of regional forums in recent years. Similar to the China–CEEC (‘17 + 1’) forum introduced above, numerous components were added to the Forum for China–Africa Cooperation (FOCAC), and China now gives the whole forum much more prominence.Footnote36 While FOCAC was founded in 2000, it is only since 2012 that China has regularly referenced this forum when debating African matters in the UN Security Council.Footnote37 Furthermore, over the span of these years, numerous FOCAC sub-forums have emerged and grown. Among them are the ‘China–Africa People’s Forum’ (2011),Footnote38 ‘China–Africa Media Forum’ (African Union Website, August 26, 2012, https://au.int/en/newsevents/26540/first-sino-african-mediaforum-cooperation-beijing-china) and a ‘China–Africa Think Tank Forum’ (2011).Footnote39 Importantly, these latter platforms are all ‘instigated and financially supported by Beijing’.Footnote40

China’s intent to ‘influence’ foreign publishing houses, media, think tanks and universities has been subject to numerous studies, but, when viewed systematically, a pattern emerges indicating that China views its ideational connectivity projects in developing countries as a stepping stone for the global projection of its discourse power (话语权). While many scholars have noted that China has long sought support from developing countries on various global issues,Footnote41 it is the intensity, the coordination and the centralisation (on Beijing’s side) that represent a new development. Whether it is China–FOCAC, the China–Arab States Cooperation Forum (CASCF), the Forum of China and the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (China–CELAC), China–CEEC or Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa (BRICS), China has spent recent years pushing for (and bankrolling) new think tank networks, media exchanges, political party dialogues and other such mechanisms for almost all its multilateral groupings.Footnote42

As more generally epitomised by the BRI, there is a clear trend to combine and merge different China + X (sub)mechanisms. Chinese authorities have referred to different China + X types of diplomatic cooperation as regional ‘communities of common destiny’ (命运共同体) with the insinuation that they will globally converge into a single such community of destiny. Along these lines, when Beijing hosts sub-formats of China + X mechanisms, they are often merged and ‘coherently held’ (配套举行). China + X mechanisms, therefore, highlight the aim to build up connectivity (power) with a particular relationality, mostly orientated at Beijing and organised on Chinese terms. For instance, the international department of the CCP’s Central Committee hosted an event in Beijing (2017) and Shenzhen (2018) called ‘Dialogue with World Political Parties’, which included ‘thematic sessions’ like the ‘2nd China–Central Asia Political Party Forum’ (Xinhua Net, December 1, 2017), the ‘3rd China–Africa Political Parties Theoretical Seminar’ (The Paper, 29 November, 2017), the ‘2nd China–CELAC Political Parties Forum’, the ‘4th China–Africa Young Leaders Forum’ and a Forum for Marxist Parties (CGTN, 28 May, 2018). While these events are combined not only for strategic but also for logistical reasons, it is noteworthy that in both Beijing and Shenzhen they were held under the same banner: a globe-shaped logo that directly speaks to the ‘China + X’ logic of diplomatic connectivity, by which China – in this case the CCP – yields significant agenda-setting and representational power (see ).

Figure 2. Logo of CPC’s ‘Dialogue with World Political Parties’.

Source: People’s Daily, “CPC Holds High-Level Dialogue.”Footnote9

In comparison, for other dialogue mechanisms that stem from a diplomatic tradition of sovereign equality (i.e. dialogue mechanisms and organisations that are not defined by the presence of a single country), China cannot apply such logic. Incidentally, the ‘1st Forum for Political Parties of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization’ (SCO) was formally treated as a stand-alone event (lacking the above logo), even though it was taking place at the same time and location as the other above-mentioned dialogues.

Historical dis/continuities of China’s commitment to the South

Some contemporary Chinese scholars differentiate four approaches among China’s diplomatic relations with the developing world, namely ‘bilateral’, ‘global multilateral’ (i.e. UN diplomacy), ‘collective diplomacy for developing regions’ (such as FOCAC or 17 + 1) and ‘group-type multilateral diplomacy’ (such as ‘G77 and China’).Footnote43 Yet these four categories are quite differently grounded in China’s historical commitment to, and diplomacy with, states that China identifies as developing countries. In order to get a better understanding of the continuities and ruptures of Beijing’s diplomacy towards the South, it is worthwhile to look at the differences among these four categories in more depth. ‘Collective diplomacy for developing regions’ is a relatively new mode, with FOCAC starting in the year 2000 and the first FOCAC Summit being held in 2006. Global multilateralism and group-type multilateral diplomacy, are, to a large degree, contingent on UN membership,Footnote44 which the mainland Chinese government took over from Taiwan in 1971. In other words, particularly throughout the ‘UN Development Decade’Footnote45 of the 1960s, Beijing was not directly involved in the political bickering around the creation of UN institutions central to the Southern agenda. In addition, the domestic Cultural Revolution incapacitated Chinese foreign policymaking at the time. Put differently, even though China was able to repair relations and reclaim the ethos of a shared identity (and struggle) with many developing countries by 1969/1970, the legacy of ‘common desires and demands’,Footnote46 as emphasised by Premier Zhou Enlai at the 1955 Bandung conference, had not been without interruptions and setbacks. It was especially through bilateral relationships that China was able to successfully cooperate with other developing countries, and it continues to do so today.Footnote47

In contrast, the moniker ‘G77 and China’, which Chinese authors view as an example of ‘group-type multilateral diplomacy’, only began to be used for official statements in 1991,Footnote48 even though the G77 had been around since the 1960s and China had generally been supportive of their agenda.Footnote49 Starting in the 1980s, China sometimes joined the G77 as a ‘special invitee’.Footnote50 While Chinese sources expound that, after UN entry in 1971, the PRC was viewed with suspicion by some G77 members and was hence unable to integrate itself among the G77,Footnote51 other commentators have stressed that it was mostly for practical and strategic reasons that China decided to stay outside of the group.Footnote52 In any case, these assessments are not mutually exclusive. As summed up by one observer at the time, Beijing presented as a pretext for its decision to remain outside the G77 that it ‘could be more effective in helping the causes of the Third World by working outside rather than inside the Group’.Footnote53 As a Security Council veto power upon its entry to the UN, China had indeed acquired a more significant identity for the UN context, which overshadowed, or at least conflicted with, the identity as one of many developing countries. Even if the Chinese leadership had preferred a different outcome regarding its relations with the G77 at the time, the first inklings of the China + X logic for the developing world can be found in this example. These inklings received clearer contours once the ‘G77 and China’ format was further institutionalised, receiving particular global attention as international climate change negotiations progressed. The latter moniker mirrored the institutionalisation of an ambiguous internal relationship between China and the group - somewhere amid observer status, membershipFootnote54 and even leadership.Footnote55 Overall, neither G77 nor ‘G77 and China’ figures prominently in Chinese foreign policy discourse. A slightly cynical interpretation of their coverage within Chinese mainstream media indicates that outlets tend to refer to the G77 as a stand-alone grouping (without reference to China) when it serves the propagandist purpose of insinuating that the use of Chinese foreign policy vocabulary in their documents (like the ‘community of common destiny’) came about voluntarily, as a soft-power win, without China pushing for it (Renminwang, September 12). Yet with regard to recent foreign policy statements by high-ranking officials, the more frequent portrayal of ‘G77 and China’ as a ‘mechanism’ (机制, i.e. not just a ‘mode’) of diplomacy (Global Times Europe, September 12, 2018) further points to attempts to treat this group more like the type of ‘China + X’ regional forum diplomacy, in which Beijing yields asymmetrical agenda-setting power. In short, Beijing sees the cumbersome and complex group diplomacy among the South – i.e. ‘G77 and China’ or BRICS – as potentially valuable but comparatively outdated. One Chinese scholar thus portrays the regional China + X formats as ‘crucial bridges’ (关键性桥梁) that can be ‘docked’ (对接) to these old group formats to improve China’s overall diplomacy with the developing world.Footnote56

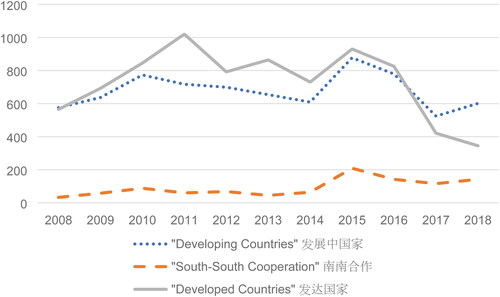

China’s versatile view of the ‘South’ and preferred vocabulary of ‘South–South cooperation’ can be contrasted with the overlapping – but more dichotomist – imaginary of developing country solidarity, which is less compatible with China’s rise and emergent identity as a global donor state.Footnote57 This assessment is mirrored by the fact that official CCP outlets have drastically reduced their references to ‘developed countries’ over the last two years (see ). While the language of solidarity with, or between, developing countries continues to be opportune (and apt) for Beijing in many contexts, the broader juxtaposition of international cooperation and South–South cooperation serves as a more flexible narrative – often keeping it an open question whether a suggested partnership is framed as the former or the latter. This trend, epitomised by the BRI to which all countries are at least rhetorically invited, is tied to a focus on the mechanisms and procedures of diplomacy and cooperation, which can be expanded to places beyond a more narrowly defined developing word (see ). Similarly, this approach allows China to widely project an ethos of benevolence – harking back to Bandung – while avoiding the relational contradictions with poorer countries that emerge as China reaches its domestic economic goals and uses development cooperation to further consolidate its status as a global power.

Figure 3. Annual references in People’s Daily.

Authors’ compilation of data gathered via CNKI China Core Newspaper Database. Accessed March, 2019.

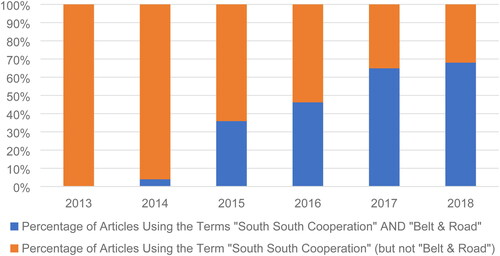

Figure 4. ‘South–South’ dissolving in ‘belt & road’?

Authors’ compilation from full search via CNKI China Academic Journals Full-text Database. Accessed March, 2019.

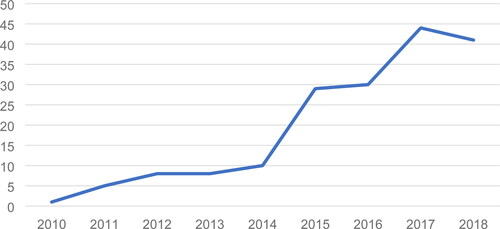

Figure 5. Frequency of the Expression “New Type of South-South Cooperation” (新南南合作 / 新型南南合作).

Authors’ compilation from full search via CNKI China Academic Journals Full-text Database. Accessed March, 2019.

Some Chinese commentators like to boast of Xi Jinping’s BRI ‘realizing the unification of ‘South–South Cooperation’ and ‘South–North Cooperation’ ‘(实现了’南南合作’与’南北合作’的统一, Study Times, February 26, 2018). Here, Beijing aims to – again – include higher income countries such as Austria (Xinhua, April 7, 2018), but follows the playbook of creating a grouping with ‘multilateral elements’Footnote58 yet with limited formalisation, ensuring that principles of sovereign state equality cannot ‘undermine its relative power in these asymmetric relationships’.Footnote59 This speaks to the centrality of the above-emphasised notion of ‘proactivity’ in China’s connectivity politics and also explains, for example, why China has been keen to add new members to BRICS: even though this grouping continues to be of value by providing diplomatic avenues for managing the complex bilateral relations with Russia and India, it is no longer in sync with Beijing’s organisational preferences.

When Chinese leaders push forward membership expansion of institutions such as BRICS, it has three potential advantages for China: firstly, it adds connectivity resources; secondly, additional members exacerbate the economic and political asymmetries of these groupings to Beijing’s advantage; and, thirdly, it increases the similarity of the membership to that of Beijing’s BRI project and thus makes it easier for China to insinuate political overlap and, therefore, leadership by retaining a clear position of primus inter pares. Echoing all these elements, and in the absence of resonance for Beijing’s ‘BRICS Plus’ proposals, the CCP’s international department has used its role heading the Chinese side of the BRICS think tank allianceFootnote60 to organise meetings in which the future of South–South cooperation is unequivocally associated with the BRI. In the words of the CCP’s international department deputy head Guo Yezhou, this means ‘pushing for a new type of South–South cooperation’ (emphasis added; 推动新型南南合作) that ‘takes the international cooperation of :Belt and Road” as its platform’ (以’一带一路’国际合作为平台) and ‘the BRICS and other cooperation mechanisms among emerging countries as starting points [literally ‘as handles’]’ (金砖合作等新兴国家合作机制为抓手, People’s Daily, February 2, 2018). This raises the question whether – from Beijing’s perspective – the idea of a ‘new type of South–South Cooperation’ (新型南南合作) is just a synonym for the (global) BRI. Along these lines, the expression of being ‘a new platform for South–South cooperation’ has been employed by Chinese officials not only to describe the 17 + 1 mechanism but also to describe the trajectory of the evolving BRI itself (Speech by Wang Yi, Xinhua, January 20, 2018, www.xinhuanet.com/world/2018-01/30/c_1122343349.htm; ‘Yidai Yilu’ Dajian’, Xinhua, August 7, 2015, http://www.xinhuanet.com/fortune/2015-08/07/c_128101147.htm.) as well as in the context of Beijing’s plans to expand the BRICS grouping to a ‘BRICS Plus’ type of grouping (Renminwang, August 31, 2018).

A ‘new (type of) South–South cooperation’?

Coming from the highest levels of policymakers, the Chinese suggestion of a ‘new type of South–South cooperation’ is a rather novel phenomenon. This does not come as a surprise. Under Xi Jinping it has simply become fashionable for Chinese scholars and cadre-theoreticians to employ the attribute ‘new type’, echoing official Party phraseology. The idea of a ‘new type of South–South cooperation’ adds to a long list of concepts like a ‘new type of international relations’ (新型国际关系) or the ‘new type of major power relations’ (新型大国关系). The concept emerges at a time when China is accelerating its outreach to developing countries, and its use of the label ‘South–South cooperation’ more generally (see ).

In the age of US President Trump’s inward turn, Beijing now sees a ‘period of historical opportunity’ (历史机遇期, People’s Daily, January 14, 2018) to expand its leadership on global governance matters. This means Chinese commentators and scholars studying South–South relations now have to deal with a new situation, because ‘China has begun to position itself as a status quo power intent on preserving and consolidating the institutional foundations of the established international order that the US did so much to create’.Footnote61 Some of the most recent Chinese academic contributions therefore suggest a highly pragmatic attitude to the (re)definition of South–South cooperation:

On the one hand, ‘New South–South Cooperation’ has inherited the political legacy of non-interference in internal affairs, in a new era of global development it emphasizes respect for the principles of different national demands and mutual benefit; on the other hand, understood against the backdrop of a global crisis … ‘New South–South cooperation’ is about working hard to maintain the fruits of globalisation.Footnote62

In other words, Beijing’s leadership is highly conscious of the fact that China’s ongoing rise hinges on the continuation of dominant international free-trade and investment regimes; one may ask whether the Chinese concept of ‘new South–South cooperation’ contains much of value to the more emancipatory projects often associated with the Global South.

Beijing tries to square the rhetorical circle (of a ‘southern’ actor connecting to the formerly ‘northern’ order) mainly by stressing what its own successful developmental trajectory has to offer to other developing countries. In the words of the above-cited Chinese scholars: ‘China itself has become the main path of experience for “new South–South cooperation”’ (中国已经成为’新南南合作’的主要经验路径).Footnote63 Beijing thereby aims to carry some of the progressiveness of the South–South rhetoric into Xi Jinping’s ‘new era’. This two-pronged approach may not be sustainable. Some observers have already documented that Southern countries are increasingly voicing their ‘concerns regarding shortcomings in the relationship [with China]’.Footnote64 Accordingly, some perceptive Chinese scholars emphasise the importance of remembering the values of China’s traditional South–South relations which were built on mutually confirmed values.Footnote65

However, for the time being, the pragmatic approach of referencing Southern solidarity while simultaneously trying to defend the status quo of the world trade order and blurring the lines of the South/non-South dichotomy is what works in China’s interest. Beijing’s global connectivity projects come with financial incentives that make it rather implausible for China’s partners to openly question Beijing’s interpretation of South–South cooperation.

Conclusion

China is likely to continue to expand its own spatial representations of the ‘South’. In this paper we have argued that for China, one important – albeit implicit – definition of the South and ‘South–South Cooperation’ relates to Beijing’s ability to engage states and other actors according to the logic of connectivity. From the macro perspective of Beijing’s political discourse, the South is located relationally to China.Footnote66 The insights of this article can therefore be applied to research on China’s foreign policy and international relations more generally and help to explain both the emergence and underlying logic of ‘connectivity politics’ as a meta-geography that orders the world in relation to China. In this sense, the South is potentially a global space and it might be necessary to understand connectivity politics in general – and the BRI in particular – not primarily as an extension of China’s Neighbourhood Realm and Policy but as China’s defining meta-geography.Footnote67 Hence, the spatial representation of these initiatives is tied to a particular mode of diplomacy that originates from China’s interactions with Southern countries and is now broadened to a wider array of states and political contexts, through political mechanisms and technological innovations in which China can wield asymmetric agenda-setting power. In this context, Beijing is now increasingly echoing what Behrooz Morvaridi and Caroline Hughes have recently described as ‘harnessing … nostalgia for state-led development to an ideological fix that in fact shores up the neoliberal world order in the context of a potentially destabilizing shift in the functioning of global capital’.Footnote68 In addition to its numerous ambitious identities as a global ‘great power’, China therefore likes to see itself portrayed as an ‘active leader of South–South cooperation’ (中国是南南合作积极领导者, People’s Daily, May 28, 2018). Judging by the amount of leverage China garners through the promises of BRI grants and loans, as well as the amount of South–South conferences and exchanges that China is currently organising, the debate about what constitutes ‘South–South Cooperation’ – and who speaks for the South – is entering a pivotal phase. Against this backdrop, international reactions, such as the 2019 EU Commission paper entitled ‘EU–China – A strategic outlook’, that directly postulate that China ‘can no longer be regarded as developing country’ (European Commission, 12 March, 2019) will likely appear more frequently in the future. Not least because of such shifts in attitudes elsewhere, China will continue to go to great lengths to relate its vision of the ‘South’ as a space of connectivity that is relationally defined vis-à-vis China and – at least rhetorically – as a ‘community of common destiny’.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Paul Joscha Kohlenberg

Paul J. Kohlenberg was a Research Associate at the German Institute for International and Security Affairs (Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik, SWP) in Berlin. Together with Dr Nadine Godehardt, he recently co-edited the volume The Multidimensionality of Regions in World Politics, which is forthcoming with Routledge in 2020. [Link: https://www.routledge.com/The-Multidimensionality-of-Regions-in-World-Politics/Kohlenberg-Godehardt/p/book/9780367280833].

Nadine Godehardt

Nadine Godehardt is the Deputy Head of the Research Division Asia at the German Institute for International and Security Affairs (Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik, SWP) in Berlin. Since 2015 she has co-edited the book series Routledge Studies on Challenges, Crises and Dissent in World Politics. From 2017 to 2019, she acted as project manager of a joint research project with ETH Zurich and the University of Geneva on Which Region? The Politics of the UN Security Council P5 in International Security Crises. Currently, she is working on a Routledge Handbook of Connectivity in World Politics with colleagues from Sciences Po, University of Oxford and KU Leuven. Together with Dr Paul J. Kohlenberg, she recently co-edited the volume The Multidimensionality of Regions in World Politics, which is forthcoming with Routledge in 2020. [Link: https://www.routledge.com/The-Multidimensionality-of-Regions-in-World-Politics/Kohlenberg-Godehardt/p/book/9780367280833].

Notes

1 See Godehardt and Kohlenberg, “China’s Global Connectivity Politics”; Godehardt and Kohlenberg, “Konnektivitätspolitik.”

2 While Beijing, since the early 1980s, officially denies any ambition to position itself as the leader of the developing world, Chinese official media likes to see the country portrayed as an ‘active leader of South–South cooperation’, even though such statements are attributed to foreign observers. See People’s Daily. “Zhongguo shi nannan hezuo jiji lingdaozhe” [“China is an Active Leader in South–South Cooperation”]. May 28, 2018. http://news.china.com.cn/world/2018-05/28/content_51525920.htm.

3 M. W. Lewis and Wigen, Myth of Continents, ix.

4 Godehardt and Kohlenberg, “Konnektivitätspolitik.”

5 Efferink, “Martin Lewis: Metageographies.”

6 Weiss, "A World Safe for Autocracy.”

7 See Ling, “Zhongguo tese daguo waijiao,” 75.

8 Xiaofeng, “Xinxing guojiguanxi,” 68 (emphasis added).

9 People’s Daily. “CPC Holds High-Level Dialogue.”

10 Blanchard and Flint, “Geopolitics of China’s Maritime Silk Road,” 225.

11 Smolnik, “Georgia Positions Itself”; Schiek, Movement on the Silk Road.

12 Wagner and Tripathi, India’s Response to the Chinese Belt; In a similar vein, China’s increasing presence and self-described identity as an aspiring ‘polar great power’ (极地强国) has produced calls for greater cooperation among regional states, ‘to be able to handle – not to mention benefit from – China’s increasing role’. Sørensen, China as an Arctic Great Power, 5.

13 Mayer and Balázs, “Modern Silk Road Imaginaries,” 216.

14 Ibid.

15 See Istenič, “China–CEE Relations,” 2.

16 Hala, “China in Xi’s ‘New Era,’" 84.

17 Ibid., 86.

18 See W. Wang, “China, the Western Balkans.”

19 Hala, “China in Xi’s ‘New Era,’" 84.

20 Hu, “Nannan hezuo,” 3.

21 Long, “Zhongguo yu fazhanzhong diqu.”

22 C. Zhang, “Zhongguo dui fazhan zhong diqu,” 24.

23 Rolland, “China’s ‘Belt and Road Initiative,’” 136.

24 Godehardt and Kohlenberg, “China’s Global Connectivity Politics.”

25 Dong, “Beiji liyi youguanzhe ‘shenden jiangou.’”

26 See Dodds and Hemmings, “Arctic and Antarctic Regionalism.” For Chinese reflections, see He, “Zhongguo-beiji guanxi.”

27 Other examples of Beijing's own visions of globality abound. See Hansen, Li, and Svarverud, “Ecological Civilization”; Segal, Chinese Cyber Diplomacy.

28 The text corpus contained 340 (English) speeches by Chinese leaders on matters of foreign policy from 2005 to 2017, parsed from the website of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MoFa). Godehardt and Kohlenberg, “China’s Global Connectivity Politics.”

29 Callahan, “China’s ‘Asia Dream.’”

30 Coward, “Against Network Thinking.”

31 Kohlenberg and Godehardt, “China’s Global Connectivity Politics.” (emphasis in original).

32 Pei, “‘Yidaiyilu’ jianshe.”

33 Wilson, China's Alternative to GPS, 7, citing Chen, “Thailand Is Beidou Navigation.”

34 D. Lewis, "China’s Global Internet Ambitions.”

35 Feigenbaum, “Reluctant Stakeholder.”

36 Eom, Brautigam, and Benabdallah, The Path Ahead.

37 Data from UNSCdeb8 database. See Kohlenberg et al., Introducing UNSCdeb8 (Beta).

38 This started as a NGO Forum (China Daily, August 29, 2011).

39 FOCAC/Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the PRC, “Declaration of the 1st Meeting.”

40 Alden and Alves, “China’s Regional Forum Diplomacy.”

41 Eisenman and Shinn, “China and Africa,” 842.

42 See Xinhua, “Xinhua BRICS Media Forum opens in Beijing “9 June, 2017, http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2017-06/08/c_136349340.htm; China–CELAC, “Subforums in Specific Fields,” accessed on 3 June, 2018, http://www.chinacelacforum.org/eng/zyjz_1/zylyflt/; China-CEEC Think Tanks Network, “Zhongguo zhongdong’ou guojia zhiku jiaoliu yu hezuo wangluo,” https://en.17plus1-thinktank.com/, accessed on 29 June 2020.

43 C. Zhang, “Zhongguo dui fazhan zhong diqu,” 31.

44 Geldart and Lyon point out that “[u]ntil 1971, therefore, it can be said that almost all of the substantive business of the G77 was related in some way to UNCTAD, and indeed principally directed to UNCTAD's plenary conferences.” Geldart and Lyon, "Group of 77,” 91.

45 Reinalda, Routledge History of International Organizations, 457.

46 Speech by Zhou Enlai at Plenary Session, reproduced in Roberts, Cold War: Interpreting Conflict, 411.

47 Eisenman, "Contextualizing China’s Belt,” 6.

48 Ding, “77 Guo Jituan;” Q. Zhang, “Zhongguo dui fazhanzhong guojia,” 25.

49 G77 acquired its name in 1964 as 77 countries used their joint voting power to convene UNCTAD, and has since expanded in membership numbers.

50 Abdenur, “Emerging Powers as Normative Agents,” 1886.

51 Yuan and Zhang, “G77 + Zhongguo,” 107.

52 Kim, “Behavioural Dimensions of Chinese Multilateral Diplomacy,” 124.

53 Ibid., 36.

54 China is listed as member state on the G77 website: http://www.g77.org/geninfo/members.htm

55 Kasa, Gullberg and Heggelund, “Group of 77 in the International Climate Negotiations.”

56 C. Zhang, “Zhongguo dui fazhanzhong diqu,” 31.

57 For a similar argument, see Abdenur, “Emerging Powers as Normative Agents,” 1888.

58 Jakóbowski, “Chinese-Led Regional Multilateralism,” 6.

59 Alden and Alves, "China’s Regional Forum Diplomacy,” 16.

60 Luo, “Jinzhuan Guojia Zhiku,” 49.

61 Beeson and Zeng, "BRICS and Global Governance,” 2.

62 Li and Xiao, “Xin nannan hezuo,” 1 (emphasis added). Original quote: “一方面, “新南南合作”继承了南南合作中不干涉内政的政治遗产, 在新的全球发展时期强调尊重国家需求导向和互利互惠原则;另一方面, “新南南合作”在全球危机的背景下努力维护全球化的成果.”

63 Ibid.

64 Alden and Alves, "China’s Regional Forum Diplomacy,” 11.

65 Zha, “Nannan hezuo yundong licheng,” 10.

66 For a general discussion of differential modes of association in Chinese international relations, see Godehardt, No End of History, 14.

67 Bhattacharya, “Conceptualizing the Silk Road Initiative.”

68 Morvaridi and Hughes, “South–South Cooperation and Neoliberal Hegemony,” 867.

Bibliography

- Abdenur, Adriana Erthal. “Emerging Powers as Normative Agents: Brazil and China within the UN Development System.” Third World Quarterly 35, no. 10 (2014): 1876–1893. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2014.971605.

- Alden, Chris, and Ana Cristina Alves. “China’s Regional Forum Diplomacy in the Developing World: Socialisation and the ‘Sinosphere.’” Journal of Contemporary China 26, no. 103 (2017): 151–165. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10670564.2016.1206276.

- Beeson, Mark, and Jinghan Zeng. “The BRICS and Global Governance: China’s Contradictory Role.” Third World Quarterly 39, no. 10 (2018): 1962–1978. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2018.1438186.

- Bhattacharya, Abanti. “Conceptualizing the Silk Road Initiative in China’s Periphery Policy.” East Asia 33, no. 4 (2016): 309–328. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s12140-016-9263-9.

- Blanchard, Jean-Marc F., and Colin Flint. “The Geopolitics of China’s Maritime Silk Road Initiative.” Geopolitics 22, no. 2 (2017): 223–245. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14650045.2017.1291503.

- Callahan, William A. “China’s ‘Asia Dream’: The Belt Road Initiative and the New Regional Order.” Asian Journal of Comparative Politics 1, no. 3 (2016): 226–243. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/2057891116647806.

- Chen, Stephen. “Thailand Is Beidou Navigation Network’s First Overseas Client.” South China Morning Post, April 4, 2013. http://www.scmp.com/news/china/article/1206567/thailand-beidou-navigation-networks-first-overseas-client

- Coward, Martin. “Against Network Thinking: A Critique of Pathological Sovereignty.” European Journal of International Relations 24, no. 2 (2018): 440–463. . doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1354066117705704.

- Ding, Lili. “77 Guo Jituan” [“The Group of 77”]. Guoji Ziliao Xinxi 2001, no. 4 (2001): 29–32.

- Dodds, Klaus, and Alan Hemmings. “Arctic and Antarctic Regionalism.” In Handbook on the Geographies of Regions and Territories, edited by Anssi Paasi, John Harrison and Martin Jones, 489–503. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, 2018.

- Dong, Limin. “Beiji liyi youguanzhe ‘shenden jiangou’” [“The Construction of China’s Identity of ‘Arctic Stakeholder.’” Pacific Journal 2017, no. 6 (2017): 65–76. doi:https://doi.org/10.14015/j.cnki.1004–8049.2017.6.006.

- Efferink, Leonhardt van. “Martin Lewis: Metageographies, Postmodernism and Fallacy of Unit Comparability.” August, 2010. https://exploringgeopolitics.org/interview_lewis_martin_metageographies_postmodernism_fallacy_of_unit_comparability_historical_spatial_ideological_development_constructs_taxonomy_ideas_systems/

- Eisenman, Joshua. “Contextualizing China’s Belt and Road Initiative.” Written Testimony for the USCC Submitted on January 19, 2018. https://www.uscc.gov/sites/default/files/Eisenman_USCC%20Testimony_20180119.pdf

- Eisenman, Joshua, and David H. Shinn. “China and Africa.” In The Palgrave Handbook of African Colonial and Postcolonial History, edited by Martin S. Shanguhyia, and Toyin Falola, 839–854. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018.

- Eom, Janet, Deborah Brautigam, and Lina Benabdallah. The Path Ahead: The 7th Forum on China–Africa Cooperation. SAIS-CARI Briefing Paper, no. 1, China Africa Research Initiative, 2018.

- Feigenbaum, Evan A. “Reluctant Stakeholder: Why China’s Highly Strategic Brand of Revisionism Is more Challenging than Washington Thinks.” Macro Polo, April 27, 2018. https://macropolo.org/reluctant-stakeholder-chinas-highly-strategic-brand-revisionism-challenging-washington-thinks

- FOCAC/Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the PRC. “Declaration of the 1st Meeting of the China–Africa Think Tank Forum.” November 23, 2011. https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/zflt/eng/xsjl/t880276.htm

- Geldart, Carol, and Peter Lyon. “The Group of 77: A Perspective View.” International Affairs 57, no. 1 (1980): 79–101. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/2619360.

- Godehardt, Nadine. No End of History: A Chinese Alternative Concept of International Order? SWP Research Paper, 2016. http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-461135

- Godehardt, Nadine, and Paul J. Kohlenberg. “China’s Global Connectivity Politics: A Meta-Geography in the Making.” In The Multidimensionality of Regions in World Politics, edited by Paul J. Kohlenberg and Nadine Godehardt, Abingdon: Routledge, 2020 (forthcoming September).

- Godehardt, Nadine, and Paul J. Kohlenberg. “Konnektivitätspolitik: Geopolitik auf Chinesisch.” Politikum no. 2, 2019. https://wochenschau-verlag.de/neue-geopolitik-2872.html

- Hala, Martin. “China in Xi’s ‘New Era’: Forging a ‘New Eastern Bloc.’” Journal of Democracy 29, no. 2 (2018): 83–89. doi:https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2018.0028.

- Hansen, Mette Halskov, Hongtao Li, and Rune Svarverud. “Ecological Civilization: Interpreting the Chinese Past, Projecting the Global Future.” Global Environmental Change 53 (2018): 195–203. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2018.09.014.

- He, Guangqiang. “Zhongguo-beiji guanxi de biaoda yu fenxi; shijie ditu de shijiao” [Representation and Analysis of China–Arctic Relationship: From the Perspective of World Maps”] The Journal of International Studies [Guoji zhengzhi yanjiu] 2017, no. 3 (2017): 38–61.

- Hu, Yong. “Nannan hezuo shiye xia de zhongguo-zhongdongou guojiahezuo” [“China–Central and Eastern European Countries’ Cooperation from the Perspective of South–South Cooperation”]. Journal of Social Sciences [Shehui Kexue] 2017, no. 10 (2017): 3–14. doi:https://doi.org/10.13644/j.cnki.cn31-1112.2017.10.001.

- Istenič, Saša. “China–CEE Relations in the 16 + 1 Format and Implications for Taiwan.” Paper Presented at the 14th Annual Conference on China–EU Relations and the Taiwan Question, Shanghai, October 19–21, 2017. https://www.swp-berlin.org/fileadmin/contents/products/projekt_papiere/Taiwan2ndTrack_Sa%C5%A1a_Isteni%C4%8D_2017.pdf

- Jakóbowski, Jakub. “Chinese-Led Regional Multilateralism in Central and Eastern Europe, Africa and Latin America: 16 + 1, FOCAC, and CCF.” Journal of Contemporary China 27, no. 113 (2018): 659–673. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10670564.2018.1458055.

- Kasa, Sjur, Anne T. Gullberg, and Gørild Heggelund. “The Group of 77 in the International Climate Negotiations: Recent Developments and Future Directions.” International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics 8, no. 2 (2008): 113–127. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10784-007-9060-4.

- Kim, Samuel S. “Behavioural Dimensions of Chinese Multilateral Diplomacy.” The China Quarterly 72 (1977): 713–742. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305741000020476.

- Kohlenberg, Paul Joscha, and Nadine Godehardt. “China’s Global Connectivity Politics. On Confidently Dealing with Chinese Initiatives.” SWP Comment no. 17 (2018): 2.

- Kohlenberg, Paul Joscha, Nadine Godehardt, Stephen Aris, Fred Sündermann, Aglaya Snetkov, and Juliet Jane Fall. Introducing UNSCdeb8 (Beta): A Database for Corpus-Driven Research on the United Nations Security Council. SWP Working Paper Asia Division no. 1. June 2019. https://www.swp-berlin.org/fileadmin/contents/products/arbeitspapiere/UNSCdeb8_Security_Council_Database.pdf

- Lewis, Dev. China’s Global Internet Ambitions: Finding Roots in ASEAN. ICS Occasional Paper, no. 14. 2017. https://www.icsin.org/uploads/2017/07/24/95ef81ecfcb1118bcfbf94b369d0ef1e.pdf

- Lewis, Martin W., and Kären Wigen. The Myth of Continents: A Critique of Metageography. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1997.

- Li, Xiaoyun, and JinXiao. “Xin nannan hezuo de xingqi: Zhonguo zuowei lujing” [“The Rise of New South–South Cooperation: China as a Path”]. Journal of Huazhong Agricultural University (Social Sciences Edition) 2017, no. 5 (2017): 1–11.

- Ling, Wei. “Zhongguo tese daguo waijiao de lilungoujian yu shijian” [“Theoretical Basis and Practical Innovation of Big Power Diplomacy with Chinese Characteristics”]. Frontiers, no. 10 (2019): 70–77. doi:https://doi.org/10.16619/j.cnki.rmltxsqy.2019.10.010.

- Long, Jing. “Zhongguo yu fazhanzhong guojia diqu zhengti waijiao xianzhuang pinggu yu weilai zhanwang” [“China’s Diplomacy vis-à-vis the Developing World: Evaluation and Prospects”]. Global Review [Guoji Zhanwang] 2017, no. 2 (2017): 40–60. doi:https://doi.org/10.13851/j.cnki.gjzw.201702003.

- Luo, Jia. “Jinzhuan Guojia Zhiku Hezuo de Xianzhuang, Kunjing, yu Celüe” [“The Status Quo, Dilemma and Strategy of the Cooperation of Difficult BRICS Countries”]. Think Tank Theory and Practice [Zhiku Lilun yu Shijian] 3, no. 2 (2018): 47–54.

- Mayer, Maximilian, and Dániel Balázs. “Modern Silk Road Imaginaries and the Co-Production of Space.” In Rethinking the Silk Road China’s Belt and Road Initiative and Emerging Eurasian Relations, edited by Maximilian Mayer, 205–226. Singapore: Springer, 2018.

- Morvaridi, Behrooz, and Caroline Hughes. “South–South Cooperation and Neoliberal Hegemony in a Post-Aid World.” Development and Change 49, no. 3 (2018): 867–892. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/dech.12405.

- Pei, Zhanghong. “‘Yidaiyilu’ jianshe de weilai fazhan qushi [“Future Development Trends of ‘Belt and Road’ Construction”]. China Social Science Network, April 22, 2017. http://www.cssn.cn/sf/bwsfgyk/yc_jjx/201704/t20170422_3495396.shtml

- People’s Daily. “CPC Holds High-Level Dialogue with World Political Parties Beijing.” November 30, 2017. http://en.people.cn/n3/2017/1130/c90000-9299100.html

- Reinalda, Bob. Routledge History of International Organizations: From 1815 to the Present Day. London: Routledge, 2009.

- Roberts, Priscilla. The Cold War: Interpreting Conflict through Primary Documents. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, 2018.

- Rolland, Nadège. “China’s ‘Belt and Road Initiative’: Underwhelming or Game-Changer?” The Washington Quarterly 40, no. 1 (2017): 127–142. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/0163660X.2017.1302743.

- Schiek, Sebastian. Movement on the Silk Road, China’s “Belt and Road” Initiative as an Incentive for Intergovernmental Cooperation and Reforms at Central Asia’s Borders. SWP Research Paper, no. 12, 2017. https://www.swp-berlin.org/fileadmin/contents/products/research_papers/2017RP12_ses.pdf

- Segal, Adam. Chinese Cyber Diplomacy in a New Era of Uncertainty. Hoover Institution Aegis Paper Series, no. 1703, 2017. https://www.hoover.org/sites/default/files/research/docs/segal_chinese_cyber_diplomacy.pdf

- Smolnik, Franziska. “Georgia Positions Itself on China’s New Silk Road: Relations between Tbilisi and Beijing in the Light of the Belt-and-Road Initiative.” SWP Comment, no. 13, 2018. https://www.swp-berlin.org/en/publication/georgia-positions-itself-on-chinas-new-silk-road

- Sørensen, Camilla T. N. China as an Arctic Great Power: Potential Implications for Greenland and the Danish Realm. Danish Defense Policy Brief. February, 2018. http://www.fak.dk/publikationer/Documents/Policy%20Brief%202018%2001%20februar%20UK.pdf

- Wagner, Christian, and Siddharth Tripathi. “India’s Response to the Chinese Belt and Road Initiative – New Partners and New Formats.” SWP Comment No. 7, 2018. https://www.swp-berlin.org/fileadmin/contents/products/comments/2018C07_wgn_Tripathi.pdf

- Wang, Wawa. “China, the Western Balkans and the EU: Can Three Tango?” Euractiv, May 17, 2018. https://www.euractiv.com/section/energy/opinion/china-the-western-balkans-and-the-eu-can-three-tango/

- Weiss, Jessica Chen. “A World Safe for Autocracy: China’s Rise and the Future of Global Politics.” Foreign Affairs 98 (2019): 92–102. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/china/2019-06-11/world-safe-autocracy

- Wilson, Jordan. China’s Alternative to GPS and Its Implications for the United States. US–China Economic and Security Review Commission, 2017. https://www.uscc.gov/sites/default/files/Research/Staff%20Report_China%27s%20Alternative%20to%20GPS%20and%20Implications%20for%20the%20United%20States.pdf

- Xiaofeng, Song. (宋效峰). “Xinxing guojiguanxi: neihan, lujing yu fanshi” [“New Type of International Relations: Meaning, Methods and Paradigms”]. Social Sciences in Xinjiang, 2 (2019): 65–71. https://www.sohu.com/a/321194940_618422.

- Yuan, Minchen, and Yan Zhang.“ ’G77 + Zhongguo’ Dui Nannan Hezuo de Zuoyong Tanxi” [“An Analysis of the Role of ‘G77+ China’ in South–South Cooperation”]. Journal of Chengdu Teachers College 33, no. 3 (2017): 105–108. doi:https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.2095-5642.2017.003.105.

- Zha, Daojiong. “Nannan hezuo yundong licheng: dui ‘Yidai Yilu’ de Qishi” [“The History of the South–South Cooperation Movement: Implications for BRI”]. Development Finance Research [Kaifaxing Jinrong Yanjiu] no. 3 (2018): 3–11. doi:https://doi.org/10.16556/j.cnki.kfxjr.2018.03.001.

- Zhang, Chun. “Zhongguo dui fazhan zhong diqu zhangti waijiao yanjiu” [“Research on China’s Collective Diplomacy for Developing Regions”]. Global Review [Guoji Zhanwang] 2018, no. 5 (2018): 18–35. doi: https://doi.org/10.13851/j.cnki.gjzw.201805002.

- Zhang, Qingmin. “Zhongguo dui fazhanzhong guojia zhengce de buju” [“The Composition of China’s Policy on Developing Countries”]. Foreign Affairs Review [Waijiao Pinglun] no. 1 (2007): 22–28. doi:https://doi.org/10.13569/j.cnki.far.2007.01.005.