ABSTRACT

We investigated how the sequence of presenting social media sources in an unsupervised inductive learning setting supports the acquisition of source evaluation skills in two different age groups. Participants were 63 upper and 59 lower secondary students. They had to identify characteristics of trustworthiness while studying sources labeled as trustworthy and untrustworthy presented in one of two ways: interleaved (alternating sequence) or blocked (without alternation). Upper secondary students recognized expertise and benevolence as key source characteristics earlier than their younger counterparts and discerned more reliably between trustworthy and untrustworthy sources. Interleaving fostered upper secondary students’ ability to recognize benevolence and elevated their trust in and use intention for trustworthy sources. This was reflected in higher perceived learning scores. For lower secondary students, unsupervised inductive learning resulted in low discernment scores, irrespective of sequence. Recognizing benevolence based on professional affiliations is particularly difficult for younger students with low social media experience.

Introduction

In today’s digital age with information readily available at our fingertips, the ability to evaluate online sources is of utmost importance (Britt et al., Citation2019). Although the Internet serves as a vast repository of information, not all of it is trustworthy. Due to the abundance of misinformation in social media and the ease with which false information can be created and disseminated, it is crucial to develop and promote skills for evaluating the trustworthiness of online sources. Accordingly, an increasing number of source evaluation trainings have been devised (for an overview, see Brante & Strømsø, Citation2018).

However, what many intervention studies have overlooked so far is that inductive learning from source exemplars is an intrinsic component of any intervention package. Such inductive learning requires individuals to identify the principles of category membership from exemplars by themselves and on their own, that is, without explicit explanation. Nonetheless, such interventions have paid little attention to established instructional principles that facilitate inductive learning from easily confusable categories. One such principle relates to the manipulation of the sequence in which learning materials are presented during learning (henceforth called the study sequence). In particular, presenting learning materials in an interleaved sequence, in which exemplars of different categories are juxtaposed, has proven to be more conducive to learning than a blocked sequence in which categories are presented without alternation (Brunmair & Richter, Citation2019).

Against this backdrop, the present research aimed to optimize unsupervised inductive learning from social media sources by manipulating the sequence of source presentation during learning. The target groups were lower and upper secondary students, two groups that are increasingly using social media to find out about factual content (Smahel et al., Citation2020). This situates the present research at the crossroads of research on study sequence effects in inductive learning and research on the acquisition of source evaluation skills. Combining these strands of research has the potential to empower learners to discern between trustworthy and untrustworthy sources by fostering their ability to identify the crucial yet nuanced distinctions between them.

Evaluation of source information while reading

Evaluating source information is a crucial epistemic strategy that readers can use to validate online information, especially when they lack accurate topic knowledge (Bromme et al., Citation2010; Stadtler & Bromme, Citation2014). Consistent with Britt and Rouet (Citation2012), we define source information as any data enabling readers to reconstruct the contextual backdrop against which a document was created. This encompasses various elements such as the document’s authors, their motivations, and their expertise in the subject matter; the intended audience; the publication date; and the information resource (e.g., a social media platform) on which the document has been disseminated. Hence, the term “source” is an umbrella concept that integrates the available source information and can thus take on values on such dimensions as expertise or benevolence.

One influential theory of reading comprehension, the document model framework by Britt and Rouet (Citation2012), delineates how readers mentally represent source information and connect it to the content they are reading about. It is assumed that readers store source information in so-called document nodes and that when they read multiple documents, these are interconnected into an intertext model. The intertext model complements the representation of contents: the “integrated mental model.” When both layers—the intertext model and the integrated mental model—are connected, Britt and Rouet call this a full documents model. Although representing source and content information in this way can be a laborious task, it is nonetheless productive because it enables readers to evaluate contents in light of their respective source.

Among the criteria that influence whether readers trust a source, two stand out: Readers evaluate whether a source is able (i.e., competent) and willing (i.e., benevolent) to provide accurate information (Mayer et al., Citation1995). For a source to be deemed competent, it must possess the necessary expertise to make a valid claim. Expertise is usually acquired through professional training and may thus be deduced from a source’s occupation and academic credentials. Benevolence, in contrast, is a more malleable construct, ascertainable from a source’s past conduct (Sperber et al., Citation2010) or organizational affiliations (Mayer et al., Citation1995). For instance, scientists affiliated with public universities are frequently regarded as benevolent, that is, characterized by the virtuous intentions of the organizations they work for (Wintterlin et al., Citation2021). In contrast, individuals whose affiliations imply vested monetary or political interests may not merit the designation of benevolence, because they could be spreading biased information that advances what are predominantly their personal objectives rather than those of the information recipient.

Developmental work has shown that the skill of evaluating sources forms early in a child’s development. Children as young as 3 years, for instance, have been found to consider a source’s competence when deciding whom to trust. When doing this, they base their assessment on the accuracy of the informant in preceding trials (see, e.g., Jaswal & Malone, Citation2007; Koenig & Harris, Citation2005). Similarly, children around that age prefer the account of a benevolent rather than that of a malevolent source (Vanderbilt et al., Citation2011). Nonetheless, it should be noted that these early skills are far from perfect and need to be practiced, refined, and applied to ever new and more abstract contexts during later stages of development.

Source evaluation skills develop during adolescence. Pieschl and Sivyer (Citation2021), for instance, used a cross-sectional design to compare 7th, 9th, and 11th graders’ evaluation of internet blog posts. Whereas 9th and 11th graders successfully discerned trustworthy from untrustworthy blog posts, 7th graders failed to do so. Likewise, Potocki et al. (Citation2019) observed a progression in source evaluation skills from fifth grade to the university level, albeit noting that some of these skills continued to be suboptimal among older readers. Indeed, many secondary students fail to spontaneously evaluate source information while reading, despite knowing about the potential benefits of attending to sources (Paul et al., Citation2017; Walraven et al., Citation2009).

Against this backdrop, research has seen an increasing number of interventions aiming to promote source evaluation skills among secondary students (Brante & Strømsø, Citation2018; Pérez et al., Citation2018). One prominent example is the intervention by Braasch et al. (Citation2013), who targeted upper secondary students’ source evaluation skills. The core instructional principle of this 60-minute intervention was to present students with contrasting cases of better and poorer source evaluation practices. The researcher-led intervention had a positive impact on the students’ capacity to evaluate the relevance of documents for specific inquiry tasks based on their assessments of source trustworthiness. Another positive outcome of this intervention was that students incorporated more precise scientific concepts from trustworthy documents into their essays after reading.

Drawing on this research, Bråten et al. (Citation2019) implemented a teacher-led 6-week intervention aiming to promote source evaluation skills among upper secondary students. Similar to the approach adopted by Braasch et al. (Citation2013), this study also asked learners to examine contrasting cases both individually and in cooperation with other students. This methodology enabled learners to effectively compare and contrast inferior and superior source evaluation practices throughout the processes of source selection, reading, and writing from multiple sources. Results showed that students who engaged in the sourcing intervention exhibited a heightened appreciation for source information when selecting texts and demonstrated a greater commitment of time and effort to comprehending the texts they selected. Furthermore, they were more inclined to acknowledge the sources of the ideas presented in the text compared to students who had participated in conventional classroom activities. These effects were particularly evident in tasks requiring the application of knowledge to diverse contexts involving multiple documents on various subjects that had been written for different purposes. Moreover, these effects endured over a period of 5.5 weeks.

The common core of both interventions lies in the use of contrasting cases to illustrate different approaches to the evaluation and use of source information. This procedure may be a promising approach to highlight subtle differences between exemplars of more and less trustworthy sources and thereby focus on corresponding evaluation practices that might otherwise go unnoticed. One natural limitation of this research, however, is that it used a comprehensive approach mixing a variety of instructional principles including, to name a few, inductive learning from contrasting cases, collaborative work, and teacher-led instruction. Hence, the specific effects of single instructional principles such as inductive learning from viewing contrasting exemplars remain unclear (cf., Brante & Strømsø, Citation2018).

Another limitation is that we do not know whether the instructional principles used can enhance source evaluation skills equally well in both younger and older students. Not only do lower and upper secondary students vary in their source evaluation abilities, they also differ in their familiarity with navigating digital information landscapes. For example, in Germany, 11% of 9- to 11-year-old children who use the internet report using social media daily or almost daily, several times a day, or all the time. This proportion increases over time to 50% for 12- to 14-year-old and 75% for 15- to 16-year-old lower secondary school students (Smahel et al., Citation2020). Accordingly, we can assume that most children who have just entered lower secondary school are starting to gain experience with social media, whereas most students in upper secondary school may well have already gathered substantial experience.

Given the age-related disparities in experience with social media and source evaluation skills, an instructional approach that has proven to be effective in cultivating digital source evaluation skills in lower secondary students may not yield the same benefits for upper secondary students, or vice versa. However, research on aptitude–treatment effects in fostering source evaluation skills is scant. Therefore, one important research desideratum is to understand how far instructional principles are suitable for learners of different ages.

Study sequence as an instructional principle for inductive learning

Inductive learning from exemplars is an intrinsic component in both nonguided informal learning and teacher-orchestrated study scenarios. Previous research on inductive learning has revealed the significance of the sequence in which exemplars of to-be-learned categories are presented. Meta-analysis (Brunmair & Richter, Citation2019) showed that learners are better able to distinguish between easily confusable categories (e.g., A and B) and, in turn, classify novel exemplars more reliably when they study category exemplars in an interleaved (switching ABABAB) rather than a blocked sequence (separating AAABBB). Interleaving effects have been shown for different age groups ranging from elementary (Nemeth et al., Citation2021) to university students. This research typically uses pictorial study stimuli such as painting styles (Kang & Pashler, Citation2012), mathematical learning tasks such as calculating the volume of geometric figures (e.g., Rohrer et al., Citation2014), or probability tasks (Schalk et al., Citation2020). Moreover, the implementation of interleaving has been extended to expository texts on semantic categories such as psychological disorders (Zulkiply et al., Citation2012), crime cases (Helsdingen et al., Citation2011), and animal taxonomy (Abel et al., Citation2020). While reading an interleaved text, learners are more likely to compare the categories spontaneously and, in turn, detect the underlying regularities among their characteristics (Abel et al., Citation2020). Furthermore, as Maier et al. (Citation2018) demonstrated, after reading belief-consistent and belief-inconsistent texts in interleaved sequence, readers are more likely to integrate belief-inconsistent information (see also Maier & Richter, Citation2013).

The similarity between the to-be-learned categories is a boundary condition for unfolding the interleaving effect (Carvalho & Goldstone, Citation2015), with interleaving being particularly beneficial if categories are easily confusable. Juxtaposing categories via interleaving helps learners to tell the categories apart by highlighting those differences that predict category membership (cf., Abel et al., Citation2021).

Interestingly, learners usually do not recognize the relevance of distinguishing between categories as a learning goal and lack the awareness that distinguishing requires the identification of predictive differences (Abel, Citation2023a; Abel et al., Citation2024). In fact, learners consider finding commonalities across the exemplars of the same category more important than finding differences between categories (Yan et al., Citation2017). Consequently, they perceive their learning progress as lower when studying in an interleaved manner and generally refrain from using interleaving (Janssen et al., Citation2023; Kirk-Johnson et al., Citation2019; Onan et al., Citation2022).

Present research

In the present experiment, we focused on optimizing unsupervised inductive learning processes of upper (11th grade) and lower secondary (7th grade) students facing social media posts explicitly labeled as trustworthy and untrustworthy. For this purpose, we manipulated the sequence in which Twitter user profiles and their respective posts were presented (interleaved vs. blocked). Interleaved means an alternated presentation of trustworthy and untrustworthy sources, whereas blocked means no alternation between these two types. Additionally, we prompted learners to find out for themselves what makes a source trustworthy or untrustworthy based on explicitly classified source exemplars. We assessed both learners’ pace of recognizing the key characteristics of trustworthiness (expertise and benevolence) during the study phase and subsequent learning effects, that is, their ability to discern trustworthy sources from the untrustworthy ones.

Inductive learning requires learners themselves to identify what makes a social media source (un)trustworthy from social media source exemplars. Hence, it can impose substantial challenges, and this makes it necessary to take into account learners’ preconditions such as their experience with social media. Based on previous research, we assumed that lower secondary students in seventh grade are just starting to gain experience with social media and have accordingly poor discernment skills. Upper secondary students, in contrast, have already gathered substantial experience with social media (cf., Pieschl & Sivyer, Citation2021; Smahel et al., Citation2020). This difference in experience with social media guided our sample choice.

Our hypotheses were based on the premise that trustworthy and untrustworthy sources can be deceptively similar, with the essential distinctions of expertise and benevolence being only subtle. An interleaved study sequence may highlight source characteristics that are key to making valid trustworthiness judgments and consequently enable learners to discern reliably between untrustworthy and trustworthy sources.

Research questions and hypotheses

Age-related differences hypothesis (H1)

We expected that compared to lower secondary students, upper secondary students would recognize earlier two respective dimensions of trustworthiness, expertise and benevolence, and discern untrustworthy and trustworthy sources more reliably in terms of their trust judgments and use intention.

Interleaving hypothesis (H2)

We expected that in the interleaved study sequence as compared to the blocked study sequence, both upper secondary students and lower secondary students would recognize earlier two respective dimensions of trustworthiness, expertise and benevolence, and more reliably discern untrustworthy and trustworthy sources in terms of their trust judgments and use intention.

RQ: does study sequence matter for perceived learning?

Given the finding that students are usually unaware of the beneficial effect of interleaving, we examined learners’ perceived learning. More specifically, we studied how perceived learning changed throughout the study phase depending on the study sequence and whether learners were sensitive to the potential effectivity of interleaved sequences.

Methods

The present experiment was not preregistered. We used a 2 × 2 between-subjects design with age group (upper vs. lower secondary students) as a quasi-independent variable and study sequence of information sources (interleaved vs. blocked) as an experimental factor.

Participants

We adopted our power analysis for linear mixed models and adopted the averaged interleaving effect size from the meta-analysis by Brunmair and Richter (Citation2019) of d = 0.42. To estimate the optimal sample size for a linear mixed-model analysis with discernment test performance as dependent variable, we used the web-based app PANGEA (https://jakewestfall.shinyapps.io/pangea/) with fixed factors (age group, sequence, and actual trustworthiness of sources) and random factors (subjects and test items). To find a sequence effect of d = 0.42 at the alpha level of .05 and with a power of .80 on learners’ discernment performance, which would be reflected in an interaction term between sequence and trustworthiness of sources, implying higher trust for trustworthy sources and lower trust for untrustworthy sources, we needed 120 subjects.

Fifty-nine lower secondary students from seventh grade (29 German native speakers; 33 girls; M = 12.33 years, SD = .58) and 63 upper secondary students (44 German native speakers, 34 girls; M = 17 years, SD = .81) participated in our experiment. All 122 students were attending Gymnasium, the highest track in the German tripartite secondary school system. The Ethics Review Committee of Ruhr University Bochum approved the study (reference number: EPE-2022–024). We received written informed parental consent for all participants under 18 in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Students were randomly assigned to the interleaved and blocked study conditions. Data were collected in the classroom where students worked individually on tablets.

Study materials

During the study phase, participants were presented with 25 fictitious yet realistic Twitter profiles, each sharing a link to a document. These linked documents purportedly covered one of five topics: aspartame, e-mobility, fighting dogs, charging stations, and solar panel systems. Although the participants could view the links, they were unable to access the actual documents or discern the Twitter users’ positions on these topics. This was important to mitigate potential belief-(in)consistency bias implying that learners’ perceptions of trustworthiness are influenced by their (dis)agreement with the message (cf., Wertgen et al., Citation2021). Each Twitter profile was displayed individually on separate slides (), allowing learners to study them at their own pace and decide when to proceed to the next profile.

Figure 1. Two exemplary fictitious Twitter user profiles. Each profile shared a link to its document covering a particular topic, in these examples, aspartame. The left profile was visibly labeled as untrustworthy and the right profile as trustworthy. Each profile was presented separately and accompanied by a prompt to find out what makes an information source untrustworthy or trustworthy. Critical source information was related to user’s professional qualifications (expertise) and affiliation (benevolence). The language used is German.

Importantly, all Twitter profiles were explicitly labeled as either trustworthy or untrustworthy. Untrustworthy sources failed to meet at least one of two essential criteria: expertise or benevolence. Expertise was operationalized based on a source’s academic and professional qualifications in the relevant subject matter. For instance, a nutritional scientist making claims about artificial sweeteners was considered an expert, whereas individuals lacking comparable qualifications, such as high school students or those with unrelated academic backgrounds such as engineers, were deemed to lack the necessary expertise. Similarly, benevolence was operationalized by assessing whether a source’s professional affiliation could potentially introduce conflicts of interest that might bias their intent to provide objective information. For instance, a sales manager employed by Coca Cola making claims about artificial sweeteners was considered to lack benevolence, whereas someone in a position without vested interests, such as a university researcher, was seen as benevolent in terms of the information they shared.

Before beginning the study phase, learners received the following instruction: Your task is to find out what makes a source trustworthy or untrustworthy. During the study phase, participants could view a classification label above each profile indicating whether a source is trustworthy or untrustworthy. Providing these labels was necessary to ensure that participants would accurately assess the trustworthiness of the sources and to prevent them from making wrong classifications. Learners were not provided with explanations for these classifications. Instead, as indicated by the instruction, they were prompted to generate their own justifications for the assigned classification. Each classification label was accompanied by a short prompt encouraging learners to elaborate on how to recognize it.

Additionally, beyond the source information relevant for making trustworthiness judgments, the Twitter profiles also included surface characteristics such as username, user image, gender (counterbalanced across profiles), hobbies, number of followers, and number of accounts followed. Throughout the study phase, learners were thus required to abstract over various topics and characteristics of fictitious Twitter users that were not predictive of their trustworthiness. Note that the external validity of our study setting is open to question, because we did not control for participants’ familiarity with Twitter. However, such characteristics of profile appearance are universal across social media platforms suggesting a high representativeness for our fictitious user profiles.

Study phase

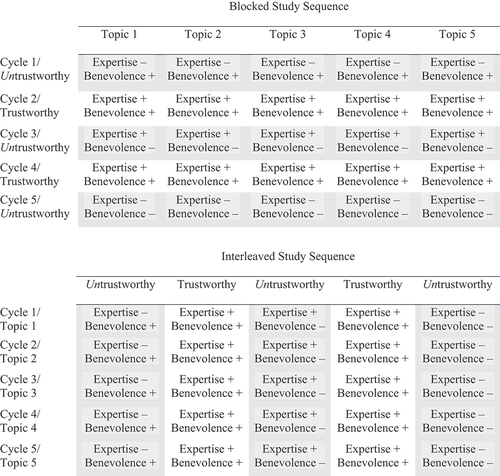

Learners progressed through the study phase in five cycles with five Twitter profiles per cycle. After each cycle, participants engaged in a free-response task in which they were prompted to articulate the factors influencing source trustworthiness. Additionally, participants provided a judgment of learning (JOL) to gauge their perceived learning. Following a between-subjects design, learners viewed the trustworthy and untrustworthy Twitter profiles in either an interleaved or a blocked order ().

Figure 2. Blocked and interleaved sequences. During the study phase, source exemplars (25 cells in total) were presented one by one, from left to right, cycle by cycle. Cycles were interspersed with a free-response task after each cycle. In the blocked sequence, per cycle, sources differed in topic but shared whether they respectively had the expertise and benevolence. In the interleaved sequence, per cycle, sources differed in their trustworthiness but shared the topic. Untrustworthy sources are highlighted in gray.

Interleaved sequence

Per cycle, all five sources referred to the same topic, but untrustworthy and trustworthy sources were presented alternately. Holding surface features such as the topic constant per cycle is essential for interleaving to be implemented successfully: When posts are similar, learners are better able to attribute changes in classification labels to key differences between the sources, level of expertise, and/or level of benevolence (cf., Abel et al., Citation2021). An untrustworthy source was placed in the first position (being benevolent, but without expertise), third position (having expertise, but not being benevolent), and fifth position (neither having expertise nor being benevolent). A trustworthy source was placed in the second and fourth positions.

Blocked sequence

Per cycle, all five sources were either untrustworthy or trustworthy without alternation but referring to different topics. According to research on the variability effect, exposing learners to a wide range of contexts and surface features helps them to recognize the underlying pattern (Likourezos et al., Citation2019). Holding the level of trustworthiness constant per cycle but varying topics might thus help learners to recognize the key characteristics of trustworthiness, and this should ensure a strong control condition. Untrustworthy sources were presented in the first cycle (all being benevolent, but without expertise), third cycle (all having expertise, but not being benevolent), and fifth cycle (all neither having expertise nor being benevolent). Trustworthy sources were presented in the second and fourth cycles.

Measures

Prior source evaluation strategy knowledge

To assess learners’ prior source evaluation strategy knowledge, we asked them to recall all strategies for evaluating statements from social media with which they were familiar. For coding, we adapted a schema applied by Barzilai et al. (Citation2023) and coded whether relevant strategies were mentioned (1 per mentioned strategy and 0 per not mentioned strategy). The maximum score was 10. We differentiated strategies for source identification (0–2), source evaluation (0–4, including expertise, benevolence, and currency), and corroboration (0–4). We provide here an authentic example of an upper secondary student’s response, who achieved 5 out of 10 points: Check if a source is provided (1 point for source identification); Check what the author’s background is and if it would be in their interest to tell a lie (2 point for source evaluation); Check if these claims can be found on other, more reputable, pages (2 points for source corroboration). The inter-rater reliability for 24 participants was very good Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC = .96). This measure served to assess age-related differences prior to the study phase and to check for the success of randomization. Note that we did not use this measure as a covariate for our analyses, because it would have interfered with the age-related differences that were our focus of interest.

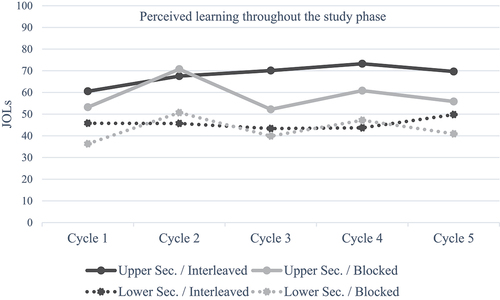

Perceived learning

After each of the five study cycles, we collected learners’ JOLs to assess perceived learning. We asked learners to indicate how many Twitter profiles out of 100 they would correctly classify as (un)trustworthy.

Pace of recognizing the dimensions of trustworthiness

After each out of five study cycles, we collected learners’ free responses on what makes a source (un)trustworthy and coded how many cycles it took learners for their response to reflect the respective dimensions of trustworthiness, expertise, and benevolence. For each dimension, we coded 0 if neither of the learner’s response reflected it, 1 if a learner recognized it in the fifth cycle, 2 if in the fourth, 3 if in the third, 4 if in the second, and 5 if in the first cycle. Inter-rater reliability was very good for expertise (Cohen’s κ = .89) and benevolence (Cohen’s κ = 1.0).

Trust judgments and use intention in the discernment test

To assess learning outcomes—that is, learners’ subsequent ability to discern trustworthy and untrustworthy sources—we asked learners to rate the trustworthiness of 12 Twitter profiles and to indicate their intention to use a respective source when preparing a presentation (both on a 6-point Likert scale ranging from 1 [absolutely disagree] to 6 [fully agree] with overall 24 test items). Learners were faced with trustworthy (3 per topic) and untrustworthy information sources (3 per topic) on two novel topics: 5 G and fracking. The design of untrustworthy sources for the discernment test followed the same pattern as that presented in for the study phase: Out of three untrustworthy sources per topic, one violated expertise, one violated benevolence, and one violated both conditions. This time, the Twitter profiles were presented without a trustworthiness label.

Sequence effectivity judgments

After they had completed the discernment tasks, we asked students to indicate the most effective sequence for studying information sources (a) one-at-a-time sequence, that is, to study the trustworthy sources first and then the untrustworthy ones (or the other way around), which corresponds to blocking; (b) alternating sequence, that is, to mix trustworthy and untrustworthy sources, which corresponds to interleaving; or (c) both were equally effective.

Results

The data and the analyses script for SPSS are publicly available at https://osf.io/udac7/?view_only=b291f5cde30e49e8a988db0f539161b5. Across the analyses, we incorporated the demographic variable of whether learners were native German speakers as covariate. displays the mean scores and standard deviations of all dependent measures as a function of age group and sequence manipulation.

Table 1. Means and standard deviations of dependent measures as a function of age group and study sequence manipulation (with whether German is native language as a covariate).

Prior source evaluation strategy knowledge

As suggested by previous research (cf., Pieschl & Sivyer, Citation2021), upper secondary students had superior source evaluation skills compared to lower secondary students, F(1,113) = 15.38, p < .001, ηp2 = .12, MD = 0.56, SE = 0.14. However, from the whole sample, only two upper secondary students reported checking for expertise and only one upper secondary student reported checking for benevolence. There were no differences between either the upper or lower secondary students who worked on the interleaved and blocked sequence, Fs < 1.

Discernment test performance

To test our hypotheses on discerning trustworthy and untrustworthy sources in terms of trust judgments and use intention, we ran a linear mixed-model analysis (with whether German is the native language as a covariate). As fixed effects, we entered respectively the interaction terms of age group, sequence, and item type (test items assessing trust judgment vs. use intention) with the actual level of trustworthiness of the sources in question (trustworthy vs. untrustworthy) in the models. As random effects, we entered subjects, test items, sources, and topic of sources.

displays the pattern of trust judgments for trustworthy sources (left) and untrustworthy sources (right) as a function of age group and sequence manipulation (note, the same pattern applies to the use intention). Additionally, displays the pattern of how well learners discern untrustworthy and trustworthy sources in terms of trust judgments (left) and use intention (right). For this purpose, we subtracted their scores for untrustworthy sources from their scores for trustworthy sources.

Figure 3. Mean number and standard errors for learners’ trust judgments. Trust judgments (on a Likert scale from 1 to 6) in trustworthy sources (left) and untrustworthy sources (right) as a function of age group (upper secondary vs. lower secondary students) and study sequence (interleaved vs. blocked). The same pattern applies to the use intention.

Figure 4. Mean number and standard errors for learners’ ability to discern trustworthy and untrustworthy sources. Values for untrustworthy sources were subtracted from the values for trustworthy sources with a theoretical range between 5 and −5. Discernment is reported in terms of trust judgments (left) and use intention (right) as a function of age group (upper secondary vs. lower secondary students) and study sequence (interleaved vs. blocked).

Age-related differences hypothesis (H1)

We expected that upper secondary students would discern more reliably between trustworthy and untrustworthy sources than their lower secondary counterparts. In line with this expectation, we found a significant interaction between age group and trustworthiness, F(2, 1369) = 67.77, p < .001, ηp2 = .09. Upper secondary students discerned untrustworthy and trustworthy sources more reliably in their trust judgments and use intentions than lower secondary students. They placed more trust in and reported a greater intention to use trustworthy sources, p < .001, 95% CI [0.42, 0.71], MD = 0.57, SE = 0.80, as well as less trust in and less intention to use untrustworthy sources, p < .001, 95% CI [−0.83, −0.53], MD = −0.68, SE = 0.80. There was no three-way interaction with item type, F(2, 1369) < 1, p = .457, ηp2 = .00. Accordingly, the pattern was the same for trust judgments and use intention, fully supporting our hypothesis.

Interleaving hypothesis (H2)

We expected that interleaved learning would result in a more reliable discernment than blocked learning. Inconsistent with our expectation, we found no interaction effect between sequence and trustworthiness, F(2, 1369) = 1.37, p = .255, ηp2 = .00. There was also no three-way interaction with item type, F(2, 1369) < 1, p = .845, ηp2 = .00.

Exploring interaction between age group and sequence

We tested whether the effect of interleaved learning differed between the upper secondary students and their lower secondary counterparts. We found a three-way interaction between age group, sequence, and trustworthiness, F(2, 1369) = 13.04, p < .001, ηp2 = .02, and no four-way interaction including item type, F(2, 1369) < 1, p = .696, ηp2 = .00. To decompose the three-way interaction, in the following, we tested the interleaving hypothesis on the discernment of trustworthy and untrustworthy sources for both age groups separately.

Interleaving hypothesis for upper secondary students

Consistent with our expectation, upper secondary students placed more trust in and reported a greater intention to use trustworthy sources when studying in the interleaved sequence as compared with the blocked sequence, p < .001, 95% CI [0.30, 0.71], MD = 0.51, SE = 0.10. However, they did not report placing less trust in and less intention to use untrustworthy sources, p = .782, 95% CI [−0.18, .24], MD = 0.03, SE = 0.11.

Interleaving hypothesis for lower secondary students

Unexpectedly, lower secondary students placed less trust in and reported less intention to use trustworthy sources when studying in the interleaved sequence compared with the blocked sequence, p = .017, 95% CI [−0.47, −0.05], MD = −.26, SE = 0.11. There was no difference for trust in or intention to use untrustworthy sources, p = .979, 95% CI [−0.22, 0.22], MD = −0.00, SE = 0.11.

Recognition pace of expertise and benevolence

The linear mixed-model analysis of discernment test performance showed an interaction effect of age group and sequence indicating that interleaving was advantageous only for upper secondary students. This made it plausible to also expect a potential interaction effect for the recognition pace of expertise and benevolence during the study phase. However, we did not use linear mixed models for the recognition pace measures, because these measures were not manipulated within subjects. Because our power analysis was not designed to assess an interaction effect via an ANCOVA (our study would have been underpowered for this), we decided to run one-tailed contrasts to test our interleaving hypothesis (H2) directly in each separate age group. Note, because we did not test directly whether the impact of sequence depended on age group, results should be interpreted with caution. Furthermore, we found only a weak correlation between the recognition pace for expertise and for benevolence across upper secondary students (r = .33, p = .009) and no significant correlation across lower secondary students (r = .19, p = .148), suggesting that we should run separate contrasts for expertise and benevolence. displays the pattern for the recognition pace of expertise (left) and benevolence (right) during the study phase as a function of age group and sequence manipulation.

Figure 5. Mean number and standard errors for the pace of recognition of source dimensions expertise (left) and benevolence (right). Numbers are presented as a function of age group (upper secondary vs. lower secondary students) and study sequence (interleaved vs. blocked). Coding here is reversed: Numbers closer to 5 stay for an early recognition. We coded 5 if a source dimension was recognized after the first cycle, 4 after the second cycle, … 1 after the fifth (last) cycle, and 0 if not at all. The recognition paces for expertise and benevolence can also be contrasted particularly by comparing the bars of interleaved sequences between left and right.

Age-related differences hypothesis (H1)

As expected, upper secondary students recognized both source dimensions earlier than lower secondary students: expertise, t(120) = 2.79, p = .003, d = 0.51, MDFootnote1 = 2.07, SE = 0.74, and benevolence, t(120) = 2.98, p = .002, d = 0.55, MD = 1.48, SE = 0.50.

Interleaving hypothesis (H2) for upper secondary students

Upper secondary students in the interleaved sequence did not recognize expertise as a source dimension earlier than upper secondary students in the blocked sequence, t(61) = 0.46, p = .324, d = 0.09, MD = −0.23, SE = 0.51. As expected, upper secondary students recognized benevolence earlier when studying in the interleaved sequence compared with the blocked sequence, t(61) = 2.43, p = .011, d = 0.46, MD = 0.79, SE = 0.34.

Interleaving hypothesis (H2) for lower secondary students

Lower secondary students did not recognize the source dimensions earlier when studying in the interleaved sequence as compared with the blocked sequence for either expertise, t(57) = 1.65, p = .051, d = 0.29, MD = −0.87, SE = 0.53, or benevolence, t(57) = 0.10, p = .459, d = 0.00, MD = 0.04, SE = 0.35. Note, the numerical tendency for the pace of recognition of expertise was not in favor of interleaving (which might be a methodical artifact; the same tendency was also found in upper secondary students).

Exploratory analysis: is evaluating benevolence cognitively more challenging than evaluating expertise?

To explore whether learners recognized expertise earlier than benevolence, we ran separate two-tailed t tests for dependent groups on upper secondary students and on lower secondary students in the interleaved condition. We used the data from the interleaved condition alone, because in this condition, expertise and benevolence both varied from the first cycle of the study phase. In the blocked sequence, in contrast, students were already faced with various sources lacking only expertise during the first cycle, whereas the sources lacking only benevolence were not presented until the third cycle.

We found the same pattern for both age groups: later recognition of benevolence as compared to expertise in upper secondary students (as numerical tendency), t(30) = 2.01, p = .054, d = 0.44, and lower secondary students, t(30) = 2.09, p = .048, d = 0.53. For a comparison, see (black bars left and right). For the study materials applied, it could be confirmed that benevolence was cognitively more challenging than expertise.

RQ: does study sequence matter for perceived learning?

To determine how learners’ perceived learning changed throughout the study phase, we ran a repeated measures ANCOVA with two between-subjects factors, age group and study sequence; study cycle as within-subjects factor; whether native speakers of German as covariate; and JOL measure as dependent variable. displays the pattern of results.

Figure 6. Averaged judgments of learning across five consecutive cycles of study phase as a function of age group (upper secondary vs. lower secondary students) and study sequence (interleaved vs. blocked).

Upper secondary students exhibited higher JOLs than lower secondary students, F(1, 113) = 18.43, p < .001, ηp2 = .14, MD = 17.55, SE = 4.09. We found a two-way interaction between study sequence and study cycle, F(4, 110) = 3.78, p = .006, ηp2 = .12, and a three-way interaction between age group, study sequence, and cycle, F(4, 110) = 3.01, p = .020, ηp2 = .10. Inspection of the graphic plot reveals monotonic curves in the interleaved sequence and fluctuating curves in the blocked sequence. When learning in the interleaved sequence, upper secondary students continuously increased their JOLs throughout the study phase (except for the last cycle), whereas lower secondary students barely changed their JOLs. For the blocked sequence, in contrast, upper and lower secondary students showed the same fluctuating pattern across the study phase with no clear progression. Hence, upper secondary students recognized their learning gains throughout an interleaved study phase.

To analyze the impact of age and study sequence on sequence effectivity judgments, we ran an ordinal regression analysis. We found no effect of study sequence, β = −.37, SE = 0.35, Wald’s χ2 = 1.17, df = 1, p = .279. Probably, sequence effectivity judgments mainly reflected learners’ prior beliefs. Age group, however, had an impact, β = .85, SE = 0.35, Wald’s χ2 = 5.91, df = 1, p = .015. Whereas 38.7% of upper secondary students considered interleaving more effective than blocking, only 19% considered blocking more effective, and 41.9% considered both sequences equally effective. In contrast, only 23.2% of lower secondary students considered interleaving more effective, but 37.5% considered blocking more effective, and 39.3% considered both sequences equally effective.

Discussion

The aim of the present research was to investigate the impact of study sequence in unsupervised inductive learning from trustworthy and untrustworthy source exemplars. Viewed through the lens of research on study sequence effects in inductive learning, the present research makes a significant contribution to the field by investigating the impact of study sequence (interleaved vs. blocked) on a novel dependent variable critical to digital literacy, specifically source evaluation, across two distinct student age groups, namely, upper and lower secondary students.

Studying source exemplars is an integral part of any source evaluation intervention. Viewed through the lens of source evaluation skills acquisition research, the added value lies in our basic approach that focuses on unsupervised inductive learning. This approach allows us to investigate the impact of student age (upper vs. lower secondary) and study sequence (interleaving vs. blocking) on learners’ ability to recognize essential source characteristics of trustworthiness, namely, expertise and benevolence, and the impact on learners’ ability to discern trustworthy and untrustworthy sources. Therefore, our findings should be considered when developing comprehensive sourcing interventions as well as when decomposing their effects on the acquisition of source evaluation skills.

To sum up our key findings: In line with our age-related differences hypothesis (H1), upper secondary students recognized expertise and benevolence as essential source characteristics of trustworthiness earlier than their lower secondary counterparts. In turn, upper secondary students evaluated information sources more reliably, displayed increased trust toward trustworthy sources, and displayed reduced trust toward untrustworthy sources lacking at least one of the essential characteristics of expertise and/or benevolence. Notably, in line with the interleaving hypothesis (H2), the interleaved sequence further supported upper secondary students’ source evaluation skills acquisition, primarily by accentuating the dimension of benevolence and consequently elevating their trust in trustworthy sources. This pattern was also reflected in their perceived learning outcomes.

In contrast, lower secondary students did not benefit from an interleaved presentation of sources. In fact, they placed more trust in trustworthy sources after blocked presentation. Overall, an unsupervised inductive learning approach proved unsuitable for them, irrespective of the study sequence. This was reflected in their limited ability to discern between trustworthy and untrustworthy sources. Nonetheless, lower secondary students accurately recognized their limited ability, as indicated by their perceived learning outcomes barely surpassing chance levels. The primary challenge lay in recognizing benevolence, whereas they had comparatively less difficulty in recognizing expertise.

Why study sequence matters for upper secondary students

The interleaving hypothesis (H2) was supported for upper secondary students with regard to some but not all critical measures. Interleaving proved effective in facilitating the recognition of benevolence: On average, benevolence was recognized between the two last cycles of the study phase in the interleaved sequence. In contrast, in the blocked sequence, in which the sources with a conflict of interest were presented together (during the third cycle), benevolence was recognized either only during the last cycle or not at all.

Consequently, the interleaved sequence enhanced the ability of upper secondary students to reliably discern trustworthy sources in terms of trust judgments and use intention. We observed that participants placed more trust in trustworthy sources and were more likely to indicate that they wanted to use them, whereas there was no effect indicating less trust and less use intention in untrustworthy sources. Obviously, upper secondary students hesitated to dismiss untrustworthy sources altogether, which is reasonable, especially when the available information about the source is limited and prior topic knowledge is low.

However, we did not observe an effect of study sequence on the pace of recognition of expertise. This discrepancy may be attributed to a methodological artifact because in the blocked sequence, all five sources lacking only professional qualifications were presented in the very first cycle (whereas these sources were dispersed throughout the study phase in the interleaved sequence). Accordingly, the blocked sequence provided many opportunities to recognize expertise as a key source characteristic right from the beginning of the study phase. However, this did not appear to hinder the upper secondary students in the interleaved condition, because the recognition of expertise occurred somewhat later but was still accomplished successfully, on average, before the penultimate cycle.

The interleaving effect in terms of more reliable discernment outcomes for trust judgments and use intention was reflected in students’ perceived learning. In the middle of the study phase, upper secondary students in the interleaved condition, unlike those in the blocked condition, began to recognize their learning progress. This finding challenges recent observations of lower perceived learning in interleaved sequences (Janssen et al., Citation2023; Kirk-Johnson et al., Citation2019; Onan et al., Citation2022; for an exception, see Abel, Citation2023b). Like we did, these studies elicited JOLs multiple times throughout the study phase. However, due to a higher mental effort investment during interleaved learning, their learners tended to lower their perceived learning. In our research, in contrast, the sensitivity to one’s own learning progress in interleaved sequences might be attributed to the explicit learning goal of discovering source characteristics that differentiate between trustworthy and untrustworthy. Unlike a typical general instruction in the field to learn categories for a subsequent classification test (cf., Brunmair & Richter, Citation2019), an explicit goal instruction to distinguish might have directed learners’ attention toward essential differences (cf., Abel et al., Citation2024). An interleaved sequence matches the learners’ goal of distinguishing by highlighting differences between trustworthy and untrustworthy sources. This alignment probably contributed to the increase in learners’ perceived learning. Because source characteristics covaried systematically with the changing trustworthiness label, learners could promptly adopt a hypothesis-testing strategy in the interleaved sequence, that is, guessing how source characteristics correspond to the trustworthiness label and then verifying, rejecting, and/or adjusting their hypotheses (Abel et al., Citation2021). In contrast, during blocked learning, fluctuations in perceived learning probably reflected the lack of frequent opportunities to promptly test one’s adjusted assumptions after rejecting the preceding ones.

It is worth noting that only a minority (1 in 5) of upper secondary students (irrespective of their sequence) judged blocking to be more effective than interleaving. We attribute the lack of the typical preference for blocking (for an exception, see Abel, Citation2023b) to the possibility that when the learning goal is oriented toward discrimination, learners’ judgments reflect their awareness that mixing categories (i.e., interleaving) highlights differences and that they then shift their preference from blocking toward interleaving (cf., Abel, Citation2023a; Abel et al., Citation2024).

Why study sequence did not matter for lower secondary students

Whereas interleaving facilitated source evaluation in upper secondary students’, their younger counterparts did not exhibit any notable improvements from an interleaved presentation of sources in either of the critical measures. In fact, lower secondary students placed less trust in trustworthy sources after the interleaved presentation compared with the blocked presentation. After analyzing the trust judgments for both trustworthy and untrustworthy sources, we rule out the possibility that interleaving made lower secondary students uniformly more or less critical, irrespective of whether the sources warranted trust. Furthermore, it is evident that both the interleaved and blocked sequences failed to manifest their distinct beneficial functions—discriminative contrast in the interleaved sequence versus topic variability within a cycle in the blocked sequence (Abel et al., Citation2021; Carvalho & Goldstone, Citation2015)—leading us to rule out an equally positive impact of both sequences.

We believe that for lower secondary students, unsupervised inductive learning was overwhelming, especially in light of their relatively limited experience with social media in general (cf., Smahel et al., Citation2020) and Twitter in particular, along with their unfamiliarity with evaluating source trustworthiness (as evidenced by their very low performance on prior source evaluation strategy knowledge). Inductively inferring the key source characteristics, expertise and especially benevolence, from source exemplars posed a substantial hurdle.

Despite a quite limited topic knowledge and world knowledge, lower secondary students were able to recognize how Twitter users’ professional qualifications reflect their expertise in the subject matter (i.e., topic knowledge) and that professional qualifications shape Twitter user’s ability to inform on the subject matter (i.e., world knowledge). This interpretation is in line with findings suggesting that secondary students might be capable of accurately rating the expertise of academic disciplines despite their limited topic knowledge (for fourth graders, see Bromme et al., Citation2010; for sixth graders, see Kiili et al., Citation2023; for seventh graders, see Lescarret et al., Citation2024; for ninth graders, see Paul et al., Citation2017; for upper secondary students, see Porsch & Bromme, Citation2010).

Yet, concerning the meaning of professional affiliation, in contrast, we observed that most lower secondary students failed to recognize it at all (as the value was barely above zero). It is plausible to assume that the lower secondary students either basically lacked the topic knowledge necessary to understand the relationship between the subject matter and one’s professional affiliation (cf., Bråten et al., Citation2011) and/or lacked the world knowledge that professional affiliation introduces conflicts of interest, which may bias the intention to inform in the subject matter.

When examining judgments of learning across the study phase, students predicted for approximately 50 of 100 sources that they could classify them accurately as either trustworthy or untrustworthy (i.e., binary decision). This reflects a chance level and could be a sign of their uncertainty. This uncertainty is also evident in discernment values for trust judgments and use intention. Whereas these values are positive, they are only just above zero (). Lower secondary students exhibited nearly equal levels of trust toward trustworthy and untrustworthy sources: The averaged scores for both trustworthy and untrustworthy values ranged between 3 and 4 (see in which 3.5 denotes a neutral position), suggesting uncertainty.

From the perspective of interleaving research, one might conclude that our study materials were unsuitable for investigating the sequence effects, and we partially agree. From the perspective of source evaluation research, however, this is a valuable finding, because it provides insight into what inductive conclusions lower secondary students are not only able but also unable to draw from social media source characteristics.

Aptitude–treatment interactions

In the context of interleaving research, there has been a growing interest in investigating aptitude–treatment interactions. Yet, so far, no moderation effects related to interindividual differences (such as working memory capacity, prior knowledge, or need for cognition) have been reported in the literature (Nemeth & Lipowsky, Citation2023; Sana et al., Citation2018). In fact, the interleaving effect has been demonstrated across diverse age groups utilizing different materials and varying degrees of top-down supervision (Brunmair & Richter, Citation2019). This spectrum includes support approaches ranging from unsupervised inductive learning using only category exemplars, across introducing the underlying principles, to engaging in practice with category exemplars and receiving subsequent feedback. Even though age is associated with a range of skill measures, previous research has not examined this aspect carefully. To gain deeper insight into how to utilize the benefits of interleaving, more research is needed to determine the cognitive (e.g., reading skills and prior knowledge on subject matter) and motivational prerequisites necessary for effective unsupervised inductive learning and to ascertain how far top-down approaches compensate for any potential deficiencies.

Limitations and future avenues

One novel aspect of our study is to have adolescents learn about the trustworthiness of sources in an inductive manner. Sources were presented as social media profiles, and this was motivated by the observation that social media are not used solely for leisure purposes but also for informational goals, especially among the younger generation (Newman et al., Citation2023). However, the use of social media as a reading environment to study source evaluation does not come without limitations. First, the profiles we presented to our participants contain only a small amount of discontinuous text. This distinguishes them significantly from other internet content such as complete websites or online encyclopedias in which learners have to read much longer, syntactically more complex blocks of information. On such websites, source information is often presented separately in “About us” sections and must be accessed actively by the reader, making source evaluation a more arduous task that many adolescent readers avoid (Paul et al., Citation2017). We believe that to have adolescents learn about the defining elements of more and less trustworthy sources, though, it is necessary to present sources in a salient manner. However, this prevents us from generalizing the results of our study to learning from more complex texts.

A further limitation results from the fact that our participants could not view the content of the social media users’ statements. This was because we wanted to prevent them from being guided in their trustworthiness judgments by the congruence of their preconceptions with the position of the statements they read (Barzilai et al., Citation2020; Lescarret et al., Citation2023; Wertgen et al., Citation2021). Instead, their full attention should be focused on the source information provided in the social media profile. Although this might be seen as a desirable simplification from a didactic perspective, it prevents us from generalizing the study results to reading situations in which readers have relevant preconceptions about the topics they are reading.

Furthermore, we operationalized untrustworthy sources as lacking only the expertise, or lacking only the benevolence, or lacking both. Their order across cycles in the blocked study sequence and within each cycle in the interleaved study sequence, however, was not counterbalanced. Accordingly, we cannot be sure that for upper secondary students, the impact of study sequence on the pace of recognition of expertise (numerically in favor of blocking) and of benevolence (significantly in favor of interleaving) is not simply an artifact. One possible explanation for this pattern is that all untrustworthy sources lacking only the professional qualifications were presented during the first cycle in the blocked study sequence (favoring blocking), whereas all untrustworthy sources with professional affiliations creating a conflict of interest were presented later in the third cycle (favoring interleaving). It is worth noting that interleaving and blocking of semantic categories are not fixed sequences but can be designed variably. Depending on their implementation, they can have different impacts on learning outcomes (cf., Pan et al., Citation2019). Note, to counteract this limitation, we addressed the exploratory question whether benevolence is more challenging than expertise by analyzing the pace of recognition only in interleaved study sequences in which various cases of untrustworthy sources were presented within each cycle.

Keeping this prior limitation in mind, both upper (numerically) and lower secondary students (significantly) recognized benevolence later than expertise. Although both source characteristics, professional qualification and affiliation, covaried systematically with the (un)trustworthiness label, the inductive conclusion from affiliation to source (un)trustworthiness was more demanding than that from professional qualification. While we need more empirical backup to rule out the possibility that this finding is merely a study materials artifact (with more familiar professional qualifications and less familiar affiliations), it might provide a valuable insight suggesting that recognizing benevolence is cognitively more challenging. Future research should address the underlying reasons for this effect. It is plausible that the necessary world knowledge for drawing inductive conclusions from source affiliation to source (un)trustworthiness, namely, that professional affiliation introduces conflicts of interest that may bias the intention to inform in the subject matter, might be less accessible than the necessary world knowledge for drawing inductive conclusions from professional qualification. If world knowledge is inaccessible, it is possible that especially younger students confuse the meaning of professional affiliation with professional qualification.

Whereas we did measure learners’ prior source evaluation strategy knowledge and found indications of a very low familiarity with the essential source characteristics (only 3 upper secondary students referred to either of the critical dimensions, with none referring to both), we lack clarity on the degree to which particularly the upper secondary students acquired new insights about source characteristics from the source exemplars. To address this, it would be prudent for follow-up research to incorporate pretests and compare the gains between different student age groups and sequences.

The present research demonstrated age-related differences in terms of recognition of trustworthiness characteristics and source evaluation ability. These findings are consistent with the notion that cognitive development and increased experience with digital media may facilitate the ability to evaluate social media sources reliably. Despite the plausibility of this developmental interpretation, the cross-sectional nature of the study leaves room for alternative explanations. Differences in sociodemographic background or even cohort effects (i.e., differences between age groups due to exposure to different digital media technologies and learning experiences) could potentially account for our findings. To definitively determine the underlying cause of age-related differences, future research should employ longitudinal designs and track the same individuals over time.

Educational implications

During the period of 4 to 5 years that lies between students of lower and upper secondary school, a notable progression unfolds. Upper secondary students exhibit enhanced discernment: They place greater trust in trustworthy sources and less trust in untrustworthy ones. At the same time, their younger counterparts in lower secondary school are not yet sufficiently equipped and lack key evaluation skills (see also Pieschl & Sivyer, Citation2021), all the while being exposed to social media, unverified information, and misinformation. They have not yet mastered the ability to distinguish which sources warrant trust. Therefore, it becomes imperative to further support this developmental trajectory. Our results highlight that unsupervised inductive training proves unsuitable for this purpose. An important follow-up direction involves facilitating bottom-up inductive learning processes through instructional support from top-down learning approaches. The dimensions of expertise and especially benevolence should be explained, illustrating how these can be discerned from source information. When selecting source exemplars, preference should be given to those whose professional qualifications and affiliations are more familiar to lower secondary students. These trustworthy and untrustworthy source exemplars, presented in interleaved (vs. blocked) sequences, should be utilized for practicing. The success of interleaved practice, demonstrated by numerous studies within elementary and lower secondary school mathematics education, is noteworthy (Nemeth et al., Citation2021; Rohrer et al., Citation2014; Taylor & Rohrer, Citation2009). During a practice session with source exemplars, special emphasis should be placed on the link between a trustworthiness label and key source information by characterizing their adherence to or violation of each source dimension.

Ethical statement

The Ethics Review Committee of Ruhr University Bochum approved the study (reference number: EPE-2022–024). The research was conducted in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki and ethical standards of the DGPS (German Society of Psychology).

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the support of our colleague, Philipp Marten, and thank him for his dedicated work in creating and providing the fictitious Twitter profiles for our study phase. We extend our genuine appreciation to Sophia Kaja Bartsch in helping us to adapt the study materials and program the experiment. We also thank Eva-Lotta Nieswand, Kim Luisa Bühler, and Saniah Shah for collecting the data and coding learners’ free responses. In addition, we thank Jonathan Harrow for careful proofreading of the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data and the analyses script for SPSS are publicly available at https://osf.io/udac7/?view_only=b291f5cde30e49e8a988db0f539161b5.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Mean difference

References

- Abel, R. (2023a). Some fungi are not edible more than once: The impact of motivation to avoid confusion on learners’ study sequence choices. Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1037/mac0000107

- Abel, R. (2023b). Interleaving effects in blindfolded perceptual learning across various sensory modalities. Cognitive Science, 47(4). https://doi.org/10.1111/cogs.13270

- Abel, R., Brunmair, M., & Weissgerber, S. C. (2021). Change one category at a time: Sequence effects beyond interleaving and blocking. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 47(7), 1083–1105. https://doi.org/10.1037/xlm0001003

- Abel, R., de Bruin, A. B. H., Onan, E., & Roelle, J. (2024). Why do learners (dis)use interleaving in learning confusable categories? The role of metastrategic knowledge and utility value of distinguishing. Manuscript submitted for publication.

- Abel, R., Niedling, L. M., & Hänze, M. (2020). Spontaneous inferential processing while reading interleaved expository texts enables learners to discover the underlying regularities. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 35(1), 258–273. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.3761

- Barzilai, S., Mor-Hagani, S., Abed, F., Tal-Savir, D., Goldik, N., Talmon, I., & Davidow, O. (2023). Misinformation is contagious: Middle school students learn how to evaluate and share information responsibly through a digital game. Computers and Education, 202, 104832. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2023.104832

- Barzilai, S., Thomm, E., & Shlomi-Elooz, T. (2020). Dealing with disagreement: The roles of topic familiarity and disagreement explanation in evaluation of conflicting expert claims and sources. Learning and Instruction, 69, 101367. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2020.101367

- Braasch, J. L. G., Bråten, I., Strømsø, H. I., Anmarkrud, Ø., & Ferguson, L. E. (2013). Promoting secondary school students’ evaluation of source features of multiple documents. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 38(3), 180–195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2013.03.003

- Brante, E. W., & Strømsø, H. I. (2018). Sourcing in text comprehension: A review of interventions targeting sourcing skills. Educational Psychology Review, 30(3), 773–799. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-017-9421-7

- Bråten, I., Brante, E. W., & Strømsø, H. I. (2019). Teaching sourcing in upper secondary school: A comprehensive sourcing intervention with follow-up data. Reading Research Quarterly, 54(4), 481–505. https://doi.org/10.1002/rrq.253

- Bråten, I., Strømsø, H. I., & Salmerón, L. (2011). Trust and mistrust when students read multiple information sources about climate change. Learning and Instruction, 21(2), 180–192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2010.02.002

- Britt, M. A., Rouet, J.-F., Blaum, D., & Millis, K. K. (2019). A reasoned approach to dealing with fake news. Policy Insights from the Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 6(1), 94–101. https://doi.org/10.1177/2372732218814855

- Britt, M. A., & Rouet, J.-F. (2012). Learning with multiple documents: Component skills and their acquisition. In J. R. Kirby & M. J. Lawson (Eds.), Enhancing the quality of learning: Dispositions, instruction, and learning processes (pp. 276–314). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139048224.017

- Bromme, R., Kienhues, D., & Porsch, T. (2010). Who knows what and who can we believe? Epistemological beliefs are beliefs about knowledge (mostly) attained from others. In L. D. Bendixen & F. C. Feucht (Eds.), Personal epistemology in the classroom: Theory, research, and implications for practice (pp. 163–193). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511691904.006

- Brunmair, M., & Richter, T. (2019). Similarity matters: A meta-analysis of interleaved learning and its moderators. Psychological Bulletin, 145(11), 1029–1052. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000209

- Carvalho, P. F., & Goldstone, R. L. (2015). What you learn is more than what you see: What can sequencing effects tell us about inductive category learning? Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 505. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00505

- Helsdingen, A., van Gog, T., & van Merriënboer, J. (2011). The effects of practice schedule and critical thinking prompts on learning and transfer of a complex judgment task. Journal of Educational Psychology, 103(2), 383–398. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022370

- Janssen, E. M., van Gog, T., van de Groep, L., de Lange, A. J., Knopper, R. L., Onan, E., Wiradhany, W., & de Bruin, A. B. H. (2023). The role of mental effort in students’ perceptions of the effectiveness of interleaved and blocked study strategies and their willingness to use them. Educational Psychology Review, 35(3), Article 85. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-023-09797-3

- Jaswal, V. K., & Malone, L. S. (2007). Turning believers into skeptics: 3-year-olds’ sensitivity to cues to speaker credibility. Journal of Cognition and Development, 8(3), 263–283. https://doi.org/10.1080/15248370701446392

- Kang, S. H. K., & Pashler, H. (2012). Learning painting styles: Spacing is advantageous when it promotes discriminative contrast. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 26(1), 97–103. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.1801

- Kiili, C., Räikkönen, E., Bråten, I., Strømsø, H. I., & Hagerman, M. S. (2023). Examining the structure of credibility evaluation when sixth graders read online texts. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 39(3), 954–969. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcal.12779

- Kirk-Johnson, A., Galla, B. M., & Fraundorf, S. H. (2019). Perceiving effort as poor learning: The misinterpreted-effort hypothesis of how experienced effort and perceived learning relate to study strategy choice. Cognitive Psychology, 115, 101237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cogpsych.2019.101237

- Koenig, M. A., & Harris, P. L. (2005). Preschoolers mistrust ignorant and inaccurate speakers. Child Development, 76(6), 1261–1277. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00849.x

- Lescarret, C., Magnier, J., Le Floch, V., Sakdavong, J.-C., Boucheix, J.-M., & Amadieu, F. (2023). “Because I agree with him”: The impact of middle-school students’ prior attitude on the evaluation of source credibility when watching videos. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 39(1), 77–104. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-023-00678-5

- Lescarret, C., Magnier, J., Le Floch, V., Sakdavong, J.-C., Boucheix, J.-M., & Amadieu, F. (2024). Do you trust this speaker? The impact of prompting on middle-school students’ consideration of source when watching conflicting videos. Instructional Science, 52(1), 41–69. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11251-023-09637-5

- Likourezos, V., Kalyuga, S., & Sweller, J. (2019). The variability effect: When instructional variability is advantageous. Educational Psychology Review, 31(2), 479–497. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-019-09462-8

- Maier, J., & Richter, T. (2013). Text-belief consistency effects in the comprehension of multiple texts with conflicting information. Cognition and Instruction, 31(2), 151–175. https://doi.org/10.1080/07370008.2013.769997

- Maier, J., Richter, T., & Britt, M. A. (2018). Cognitive processes underlying the text-belief consistency effect: An eye-movement study. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 32(2), 171–185. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.3391

- Mayer, R. C., Davis, J. H., & Schoorman, F. D. (1995). An integrative model of organizational trust. The Academy of Management Review, 20(3), 709–734. https://doi.org/10.2307/258792

- Nemeth, L., & Lipowsky, F. (2023). The role of prior knowledge and need for cognition for the effectiveness of interleaved and blocked practice. European Journal of Psychology of Education. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-023-00723-3

- Nemeth, L., Werker, K., Arend, J., & Lipowsky, F. (2021). Fostering the acquisition of subtraction strategies with interleaved practice: An intervention study with German third graders. Learning and Instruction, 71, 101354. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2020.101354

- Newman, N., Fletcher, R., Eddy, K., Robertson, C. T., & Nielsen, R. K. (2023). Reuters institute digital news report 2023. Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. CID: 20.500.12592/9dhxj5. Retrieved January 10, 2024 https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2023-06/Digital_News_Report_2023.pdf

- Onan, E., Wiradhany, W., Biwer, F., Janssen, E. M., & de Bruin, A. B. H. (2022). Growing out of the experience: How subjective experiences of effort and learning influence the use of interleaved practice. Educational Psychology Review, 34(4), 2451–2484. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-022-09692-3

- Pan, S. C., Lovelett, J., Phun, V., & Rickard, T. C. (2019). The synergistic benefits of systematic and random interleaving for second language grammar learning. Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition, 8(4), 450–462. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jarmac.2019.07.004

- Paul, J., Macedo-Rouet, M., Rouet, J., & Stadtler, M. (2017). Why attend to source information when reading online? The perspective of ninth grade students from two different countries. Computers and Education, 113, 339–354. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2017.05.020

- Pérez, A., Potocki, A., Stadtler, M., Macedo-Rouet, M., Paul, J., Salmerón, L., & Rouet, J.-F. (2018). Fostering teenagers’ assessment of information reliability: Effects of a classroom intervention focused on critical source dimensions. Learning and Instruction, 58, 53–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2018.04.006

- Pieschl, S., & Sivyer, D. 2021. Secondary students’ epistemic thinking and year as predictors of critical source evaluation of Internet blogs. Computers and Education, 160, 104038. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2020.104038

- Porsch, T., & Bromme, R. (2010). Which science disciplines are pertinent? Impact of epistemological beliefs on students’ choices. In K. Gomez, L. Lyons, & J. Radinsky (Eds.), Learning in the disciplines: Proceedings of the 9th International Conference of the Learning Sciences (pp. 636–642). International Society of the Learning Sciences.

- Potocki, A., de Pereyra, G., Ros, C., Macedo-Rouet, M., Stadtler, M., Salmerón, L., & Rouet, J.-F. (2019). The development of source evaluation skills during adolescence: Exploring different levels of source processing and their relationships. Journal for the Study of Education and Development, 43(1), 19–59.

- Rohrer, D., Dedrick, R. F., & Burgess, K. (2014). The benefit of interleaved mathematics practice is not limited to superficially similar kinds of problems. Psychonomic Bulletin and Review, 21(5), 1323–1330. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-014-0588-3

- Sana, F., Yan, V. X., Kim, J. A., Bjork, E. L., & Bjork, R. A. (2018). Does working memory capacity moderate the interleaving benefit? Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition, 7(3), 361–369. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jarmac.2018.05.005

- Schalk, L., Roelle, J., Saalbach, H., Berthold, K., Stern, E., & Renkl, A. (2020). Providing worked examples for learning multiple principles. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 34(4), 813–824. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.3653

- Smahel, D., Machackova, H., Mascheroni, G., Dedkova, L., Staksrud, E., Ólafsson, K., Livingstone, S., & Hasebrink, U. (2020). EU Kids Online 2020: Survey results from 19 countries. EU Kids Online. https://doi.org/10.21953/lse.47fdeqj01ofo

- Sperber, D., Clément, F., Heintz, C., Mascaro, O., Mercier, H., Origgi, G., & Wilson, D. (2010). Epistemic vigilance. Mind & Language, 25(4), 359–393. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0017.2010.01394.x

- Stadtler, M., & Bromme, R. (2014). The content–source integration model: A taxonomic description of how readers comprehend conflicting scientific information. In D. N. Rapp & J. Braasch (Eds.), Processing inaccurate information: Theoretical and applied perspectives from cognitive science and the educational sciences (pp. 379–402). MIT Press.

- Taylor, K. M., & Rohrer, D. (2009). The effects of interleaved practice. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 24(6), 837–848. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.1598

- Vanderbilt, K. E., Liu, D., & Heyman, G. D. (2011). The development of distrust. Child Development, 82(5), 1372–1380. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01629.x