Abstract

Purpose: Early pregnancy complications are common and often result in pregnancy loss, which can be emotionally challenging for women. Research on the emotional experiences of those attending Early Pregnancy Assessment Units [EPAUs] is scarce. This analysis explored the emotions which women spontaneously reported when being interviewed about their experiences of using EPAU services.

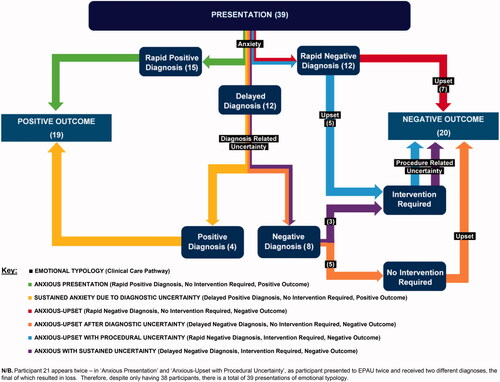

Materials and methods: Semi-structured telephone interviews were conducted with a purposive sample of 38 women. Using Thematic Framework Analysis, we identified six unique emotional typologies which mapped onto women’s clinical journeys.

Results: Women with ongoing pregnancies were characterized as having: “Anxious Presentation” or “Sustained Anxiety due to Diagnostic Uncertainty”, dependent on whether their initial scan result was inconclusive. Women with pregnancy loss had one of four emotional typologies, varying by diagnostic timing and required interventions: “Anxious-Upset”; “Anxious-Upset after Diagnostic Uncertainty”; “Anxious-Upset with Procedural Uncertainty”; “Anxious with Sustained Uncertainty”.

Conclusions: We provide insights into the distinct emotions associated with different clinical pathways through EPAU services. Our findings could be used to facilitate wider recognition of women’s emotional journeys through early pregnancy complications and stimulate research into how best to support women and their partners, in these difficult times.

Introduction

Pregnancy is often associated with positive emotions, however, complications in early pregnancy are common and the first few months can be uncertain and emotionally troubling for women and their partners [Citation1,Citation2]. In the UK, it has been estimated that a third of women experience bleeding in early pregnancy [Citation3], with 12–24% of all clinically-recognized pregnancies ending in early miscarriage [Citation4]. In the UK, women with early pregnancy complications are cared for in Early Pregnancy Assessment Units [EPAUs], specialist units that form an integral part of the National Health Service [NHS] provision. The EPAU teams (usually comprising nurses, midwives, sonographers, and doctors) offer clinical assessments, ultrasound scans, and laboratory investigations, as well as treatment and advice. Women can self-refer or be referred to EPAUs by their GP, midwife, or any other healthcare professional if they experience bleeding, pain, or other pregnancy-related complaints or have previously had an early pregnancy loss.

Pain and bleeding in early pregnancy are associated with fear of pregnancy loss, which is reported to have longstanding consequences on psychological health [Citation5]. The field of psycho-obstetrics has traditionally focused on postnatal depression [Citation6]; however, perinatal anxiety has recently received more research attention [Citation7,Citation8]. Negative psychological responses to the risk of, or to the actual pregnancy loss, have been found to manifest over time and can be detrimental to maternal mental health [Citation1,Citation2,Citation9]. Research has demonstrated poor psychological outcomes associated with pregnancy loss with a potential “carry-over” effect on future pregnancies [Citation10,Citation11].

Following calls for more qualitative work exploring women’s perspectives of pregnancy loss management [Citation12], the aim of this analysis was to explore the emotions which women experience during their EPAU care.

Materials and methods

This qualitative analysis forms part of a large national prospective study, which evaluated how the organization of EPAUs affected a variety of clinical, service, and patient-centered outcomes (VESPA Study [Citation13–15]). The VESPA study received ethical approval from the North West—Greater Manchester Central Research Ethics Committee, 26/09/2016, ref: 16/NW/0587. This analysis pertains to the development of emotional typologies which women experience whilst being cared for in EPAUs. All women spontaneously expressed emotional insights into their experiences of EPAU care, in the interviews without being directly questioned, as this was not part of the interview schedule (Supplementary Appendix 1). However, during analysis the importance of women’s emotions became clear, and associations with clinical pathways began to emerge, which warranted closer examination. This allowed us to perform a secondary analysis in addition to that which was first intended and has been reported elsewhere [Citation15].

Study team and philosophical underpinning

The authorship team is multi-disciplinary, comprised of a psychologist (SAS), medical doctors (JAH, MM, VG, JS, and SJ), and a social scientist (GB), with expertise in women’s mental health (SAS), public health (JAH, GB, JS, and VG), and early pregnancy loss management and care in obstetrics and gynaecology (MM and DJ). Given the nature of the multi-disciplinary team, we adopted an ontological (what we know about a phenomenon) and epistemological (how we acquire knowledge about that phenomenon) stance rooted in paradigmatic pragmatism [Citation16], allowing for interpretation of experiences in relation to the context in which participants inhabit [Citation17]. This meant we collected data and subsequently analyzed them in a nonjudgmental way accepting the participants’ narratives and framed these within the parameters of social norms within the UK with regard to pregnancy loss.

Recruitment and participants

Women had attended one of 26 EPAUs from the VESPA study within the 18-month period prior to the date of the interview, had completed the self-reported component of the VESPA study, and had consented to be re-contacted. Recruitment for interviews took place between January and May 2018 and women received a £20 voucher as reimbursement. To create a maximum variation sample, we employed several sampling criteria including pregnancy outcome; the configuration and geographical location of the EPAU women had attended; and their satisfaction with care (). Recruitment ceased when a fair representation of the maximum variation sampling frame we had devised had been covered.

Table 1. Sampling frame characteristics and participant demographics.

Data collection and analysis

Telephone interviews were carried out by one researcher (SAS) who had an experience of in-depth interviewing. This enabled the collection of data from across the UK due to not being restricted by geography, as is a common issue in qualitative research [Citation19]. Interviews were digitally recorded, professionally transcribed, pseudo-anonymized, and uploaded to NVivo for management and analysis. We used thematic framework analysis to analyze our data, which comprised the following stages: (1) familiarization; (2) developing a thematic framework/coding frame; (3) indexing (applying the codes systematically to the data; (4) charting (re-arranging the thematic data to allow within and between case analysis; and (5) mapping and interpretation [Citation20,Citation21]. Data reflecting women’s emotions were originally grouped into one overarching theme “Emotional Responses” within the framework and were then re-coded in a more granular fashion. After several iterations this was refined to four main codes: Anxiety (including apprehension, concern, nervousness, scared, and worried); Uncertainty (related to whether the pregnancy was viable); Uncertainty (related to how a pregnancy loss was managed); and Upset (including grief and sadness). This coding framework was then deductively applied to all transcripts to identify corresponding data. The analysis was carried out by two researchers (SAS, JAH) and was iterative and consultative; including regular sense-checking with other VESPA team members. Inter-rater reliability was not statistically measured, but consensus on a final coding framework and corresponding data was achieved through regular discussion, consultation, and negotiation of terminology [Citation22,Citation23]. As is appropriate for Thematic Framework Analysis [Citation15,Citation20,Citation21], saturation is not sought after, but rather importance is placed on the presence or absence of data for particular groups from within the population recruited (i.e. type of pregnancy outcome).

Results

One-hundred and fifty-three women were invited to interview; 39 participated. One woman was later excluded from the analysis due to her interview and clinical data not matching, meaning qualitative analyses were based on 38 women (). Women’s ages ranged between 29 and 45 (MAge = 35.5 years) and we achieved representation from women living in neighborhoods representing all levels of deprivation (). Most women were married (25/38, 66%), employed (32/38, 84%), and most pregnancies were planned (33/38, 87%). Parity ranged from 0 to 4 and gravidity ranged from 1 to 7. Clinical indication for EPAU admission included bleeding (23/38, 61%); pain (10/38, 26%); previous or suspected early pregnancy loss (3/38, 8%); and “other/not specified” (2/38, 5%).

We identified six distinct patterns of emotions or “emotional typologies” (Box 1). Each emotional typology is described using illustrative, supporting quotations from participants’ interviews.

Box 1. Emotional typologies of women accessing EPAUs.

Anxious Presentation

Sustained anxiety due to Diagnostic Uncertainty

Anxious-Upset

Anxious-Upset after Diagnostic Uncertainty

Anxious-Upset with Procedural Uncertainty

Anxious with Sustained Uncertainty

Anxious presentation

The first emotional typology comprised women who presented to EPAUs with pregnancy-related anxieties and who, after investigation, were discharged with the diagnosis of normal pregnancy, which relieved their anxiety to some extent. There were 15 women with this emotional typology, 13 of whom went on to have a live birth. Two women later lost their pregnancies (one had a miscarriage which was surgically managed, and one had a termination of pregnancy due to a foetal anomaly).

“I’m the kind of person, I quite like answers, I like to know why something is happening or what’s caused it. I was quite… not frustrated, I was quite anxious about why they couldn’t tell me what could cause the spotting, so that was kind of playing in the back of my mind, but I definitely left more reassured, I think that was just purely seeing the heartbeat.”

(Participant-34:Ongoing)

Sustained anxiety due to diagnostic uncertainty

Women with this emotional typology were anxious on presentation to the EPAU and received non-diagnostic scan results (often due to the fact that it was too early for the pregnancy to be visualized on the scan) perpetuating, rather than allaying their concerns. It was not uncommon for women to have to attend the EPAU several times before the final diagnosis could be reached which relieved their anxiety. All four women in this typology had a live birth.

“Initially I was very worried, I thought I’d lost it, then when they said there was something there then that was kind of a relief. Obviously, there was no heartbeat so then kind of gone back worried again. Yes, I was still quite worried.”

(Participant-39:Ongoing)

Anxious-Upset

Some women presented to the EPAU with concerns about their pregnancy and it was rapidly confirmed the pregnancy had ended. Their main emotion transitioned from anxiety to ‘upset’. The seven women in this typology comprised six who miscarried, and one who had a pregnancy of unknown location [PUL].

“I just felt really anxious and nervous as I walked in, I think because I knew what I was going to be told, and then once I went through the meeting with the first nurse, I did feel a lot more relaxed. I mean, I was sad about what was happening, but I just felt a lot… like I was in safe hands, if that makes sense. I felt cared for. Yes, I did throughout the whole thing. My anxiety did lessen a lot.”

(Participant-38:Miscarriage)

Anxious-Upset after diagnostic uncertainty

Women with this emotional typology had to return to the EPAU at least once as the initial scans were inconclusive, similar to the second emotional typology. Follow-up scans confirmed a non-viable pregnancy but no further treatment was required, and women were discharged. They experienced anxiety at presentation, and uncertainty while waiting for a diagnosis, and became upset on confirmation of pregnancy loss. There were five women in this typology: four had a miscarriage and one had a persistent PUL.

“For me it was more the not knowing. It was more being in that kind of in between state where you are not sure whether you are allowed to get excited about it progressing or you don’t know whether you are supposed to start preparing yourself for the worst.”

(Participant-27:Miscarriage)

Anxious-Upset with procedural uncertainty

Within this emotional typology, women presented to the EPAU and were immediately confirmed to have a non-viable pregnancy or to be experiencing a pregnancy loss, which required medical or surgical intervention. Women experienced anxiety, followed by uncertainty surrounding the procedure, and finally upset at the loss of their pregnancy. Five women were in this typology: two had ectopic pregnancies; two had miscarriages; and one woman initially had an ongoing pregnancy confirmed, but later re-presented to the EPAU requiring surgical management of miscarriage.

“I don’t think they mentioned to me, the EPAU, that it would be surgery, they just said to me that whatever it was shouldn’t be there and they were going to look after me and I’d be referred up to the ward, but they didn’t explain what would happen when I got up to the ward. I don’t think that was mentioned until I got up actually onto the gynaecology ward and spoke with the consultant…”

(Participant-9:Ectopic)

Anxious with sustained uncertainty

The final emotional typology was typified by women attending the EPAU on multiple occasions to establish whether or not the pregnancy was viable. When they finally received a negative diagnosis, they required medical or surgical intervention. Having presented with anxiety, women also experienced uncertainty at both the diagnostic and procedural stages. Three women followed this typology: two had miscarriages and one had a molar pregnancy.

“I mean, everyone was really empathetic. It felt like everyone understood what I was going through and everyone wanted me to get an answer but it was just really frustrating and everyone was like, “Oh we just need to be sure, we don’t want to do the wrong thing,” but, as you can imagine, it was a bit of a difficult time thinking am I pregnant, am I not pregnant and every time you think you’ll get an answer it was like, “Oh go away and come back next week”. It was quite trying… quite a difficult period of time.”

“I’d never had a general anaesthetic before. I don’t know… but it was just a huge thing in my head, it was like a really scary thing coming up, about going to sleep and being anaesthetised.”

(Participant-13:Molar)

Additional emotional responses

While all women expressed anxiety some women reported additional emotional responses, such as isolation and blame, which, in our data did not map to specific typologies. Feeling isolated was discussed in relation to how women felt immediately after being informed they had lost their pregnancy, especially if they felt unsupported by EPAU staff, if they had attended alone, or if they were waiting for results in public areas with women with ongoing pregnancies.

“I didn’t feel supported, I felt more like a number or almost like just a medical procedure as opposed to like a person, and I had been through something traumatic.”

(Participant-19:Miscarriage)

Feelings of blaming themselves were only mentioned by women who had lost their pregnancy. Women were often not given a reason for their loss, and they often feared they were at fault.

“I mean they’ve said that there’s nothing that you could have done, these things happen, but I think as much as they’ve got to try and reassure you, you’ve always got that in the back of your mind that it was something that you had done…”

(Participant-17:Miscarriage)

Regardless of typology, several women emphasized the importance of potential or actual pregnancy loss and were keen to know where support could be sought after discharge from the EPAU. This included requests for follow-up appointments that addressed the psychological effects of pregnancy loss as well as checking on physical health, especially if women were considering a subsequent pregnancy:

“I suppose in one way it’s a little odd that you can have quite a physically horrific experience and potentially have no other interaction beyond that event. I don’t know if that is an oversight……… I wonder if they could fall through the net in a very emotional point in their life.”

(Participant-14:Miscarriage)

“…I think the main thing for me is just having some form of counselling or psychotherapy in place and just almost checking the welfare of the mother, for example… when I gave birth to my little one, the health visitor comes out and she checks on you, “Have you got baby blues? Is the baby okay?” But when you have a miscarriage, it’s like you are not given the same treatment I suppose and I think what I would like to see in place in the future that it is treated like a real pregnancy, yes you have had a miscarriage but a health visitor is checking on, “Do you have depression, are you grieving, what support can we give you?””

(Participant-19:Miscarriage)

Mapping of emotional typologies to clinical care pathways

Uniquely, we were able to map women’s emotional typologies to their clinical care pathways and pregnancy outcomes which have been previously described [Citation15], as shown in . As women transitioned through different EPAU services, they were seen to present with different emotional responses depending on the aspect of the care they were experiencing. For example, all women presented anxiously to begin with, but delayed diagnoses made women feel uncertain about what was happening with their pregnancy; and negative outcomes (pregnancy losses), resulted in feelings of upset.

We were able, therefore, to establish two emotional typologies (linked to clinical care pathways) which resulted in an ongoing pregnancy: “Anxious Presentation” (Rapid Positive Diagnosis, No Intervention Required, Positive Outcome); and “Sustained Anxiety due to Diagnostic Uncertainty” (Delayed Positive Diagnosis, No Intervention Required, Positive Outcome). Whereas, there were four emotional typologies (and associated clinical care pathways) identified in women who suffered pregnancy loss: “Anxious-Upset” (Rapid Negative Diagnosis, No Intervention Required, Negative Outcome); “Anxious-Upset after Diagnostic Uncertainty” (Delayed Negative Diagnosis, No Intervention Required, Negative Outcome); “Anxious-Upset with Procedural Uncertainty” (Rapid Negative Diagnosis, Intervention Required, Negative Outcome); and “Anxious with Sustained Uncertainty” (Delayed Negative Diagnosis, Intervention Required, Negative Outcome).

Of the 38 women, 37 had one emotional typology, however, one woman had two presentations to the EPAU and experienced a different typology on each encounter, giving a total of 39 assignations to emotional typologies. Another participant, who was discharged with an ongoing pregnancy and therefore assigned to the “Anxious Presentation” emotional typology, and subsequently had a termination of pregnancy due to a foetal anomaly, without further EPAU involvement, is in our sample classified as termination of pregnancy. Therefore, due to these two women’s circumstances, there are 19 positive outcomes in the emotional typologies, despite only 17 ongoing pregnancies in the sample. Most women reported seeking care from the EPAU due to having concerns about their pregnancy, indicating that anxiety formed the base of all emotional typologies. contains a brief accompanying summary of their clinical care pathway for those whose quotations we have depicted.

Table 2. Emotional typologies and participant exemplars.

Discussion

This analysis has demonstrated the complex nature of emotions related to early pregnancy complications. Previous investigations of EPAUs have been largely focused on functionality [Citation3,Citation13–15,Citation24–27]. We believe this to be the first study to examine women’s emotional experiences associated with EPAU attendance. The emotional responses found in our analysis range from anxiety, shown by all women regardless of their presenting complaint or clinical outcome, to uncertainty, and upset. The originality of these findings lies in the clear mapping of women’s distinct emotional journeys onto their clinical care pathways. This showed how varied these pathways could be and yet also demonstrated similarities, such as anxiety being consistently reported as the primary emotion onto which others are overlaid. The fact that women experiencing early pregnancy complications and/or losses demonstrate a range of emotional responses is unsurprising. Knowledge of specialist early pregnancy services is low amongst women of reproductive age, and mental health help-seeking behavior remains uncommon in nulliparous women [Citation28]. Adverse psychological health linked to (early) pregnancy concerns [Citation8,Citation29] or (early) pregnancy loss [Citation1,Citation30] has been a recurring factor of psycho-obstetric work [Citation5].

Preconception education on early pregnancy complications whilst providing appropriate signposting to newly pregnant women may be effective in validating women’s concerns and normalizing (mental) health-seeking behaviors. The emotional typologies displayed by women in the present study’s context of EPAUs provide a basis for future research to explore how different antenatal journeys may make women feel, and what might be required to make those experiences more positive. The literature suggests psychological support for early pregnancy loss is lacking, and that there is a need for better mental health care across the antenatal and postpartum periods [Citation31,Citation32]. To date, no randomized controlled trial has assessed the effect of psychological support on mental health outcomes in subsequent pregnancies [Citation5]. Our findings also support the need to further research into what type of psychological support might be appropriate to offer women using EPAU services to prevent latent effects of pregnancy-related distress [Citation12,Citation33].

Strengths, limitations, and future research

Major strengths of our analysis are a rigorous methodological approach and multi-disciplinary nature of the research team, which helped to make our findings relevant to theory and practice in psychology, obstetrics and gynaecology, and public health. This has also responded to previous calls [Citation34,Citation35] for these disciplinary areas to work more symbiotically to provide women with the best possible early pregnancy and associated mental health care, as is done for other aspects of obstetric, gynaecological, and maternity care [Citation31,Citation36].

The use of telephone interviews allowed us to interview women from across the UK who had received EPAU care in different regions of the country. This is a major strength of the study, but we acknowledge the reliance on telephone interviews meant visual cues, such as body language and non-verbal communication were missed during data collection [Citation19].

Limitations include a very small number of women with the rarer pregnancy losses (i.e. ectopic and molar pregnancies, or terminations). More research is required to further examine specific emotional experiences associated with these less frequent causes of early pregnancy loss. Analysis of women’s emotions was not a primary aim of the VESPA study and our analysis relied on the emotional experiences which were spontaneously discussed. Our analysis would have had greater depth if we had specifically focused on women’s emotions during the interviews. Furthermore, we do not know whether the emotional typologies identified in this study are also experienced by women who do not access specialist services for early pregnancy complications, and more research should be conducted on women who traditionally avoid engagement with healthcare settings and professionals [Citation38].

Future research should consider the application of this emotional typology pathways analysis to other diagnoses where there is a degree of uncertainty (e.g. cancer), and may also look at conducting qualitative studies of this nature in tandem with objective measures of psychological state to triangulate clinical diagnoses and qualitative experiences of uncertain clinical care pathways.

Conclusion

Anxiety underpinned a range of emotional experiences described by women presenting to EPAUs with suspected early pregnancy complications. Our findings can be used by clinicians and EPAU service providers to understand the range of emotions women experience when suspecting, or experiencing, early pregnancy complications. The overlaying of unique emotional typologies onto clinical care pathways may also provide the basis for tailored follow-up based on pregnancy outcomes. There is no doubt that EPAUs offer an essential and much-valued service to women. This qualitative analysis has produced innovative evidence showing that the clinical care pathway that women are on can give clinicians insight into the woman’s emotional journey and, potentially, the need for support. More research must be undertaken to achieve a complete picture of the emotions associated with early pregnancy complications and loss and must explore any lasting impact on psychological health including how best to support women, and their partners, during these difficult times.

Patient and public involvement and engagement

The study benefited from the patient and public involvement, with women who had experienced early pregnancy complications participated in the design and timing of the study, and management oversight through study steering committee membership. The Miscarriage Association acted as co-applicant and collaborator.

Consent to participate

All participants provided fully informed written consent at the time of recruitment.

Author contributions

Davor Jurković, Maria Memtsa, Judith Stephenson, and Geraldine Barrett: conceptualization. Geraldine Barrett, Jennifer A. Hall, and Sergio A. Silverio: methodology. Sergio A. Silverio and Jennifer A. Hall: formal analysis and investigation, and writing—original draft preparation. Sergio A. Silverio, Jennifer A. Hall, Geraldine Barrett, Venetia Goodhart, Davor Jurković, Maria Memtsa, and Judith Stephenson: writing—review and editing. Davor Jurković, Maria Memtsa, Judith Stephenson, and Geraldine Barrett: funding acquisition. Jennifer A. Hall and Davor Jurković: supervision.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (22.6 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the women who willingly gave their time to participate in the study and shared with us their experiences.

Disclosure statement

Sergio A. Silverio (King’s College London) is supported by the National Institute for Health and Care Research Applied Research Collaboration South London [NIHR ARC South London] at King’s College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care. All authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Data availability statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to the sensitive nature of these data but are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Carter D, Misri S, Tomfohr L. Psychologic aspects of early pregnancy loss. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2007;50(1):154–165.

- Volgsten H, Jansson C, Skoog Svanberg A, et al. Longitudinal study of emotional experiences, grief and depressive symptoms in women and men after miscarriage. Midwifery. 2018;64:23–28.

- Edey K, Draycott T, Akande V. Early pregnancy assessment units. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2007;50(1):146–153.

- Jurkovic D, Overton C, Bender-Atik R. Diagnosis and management of first trimester miscarriage. BMJ. 2013;346(7913):f3676–7.

- San Lázaro Campillo I, Meaney S, McNamara K, et al. Psychological and support interventions to reduce levels of stress, anxiety or depression on women’s subsequent pregnancy with a history of miscarriage: an empty systematic review. BMJ Open. 2017;7(9):e017802.

- Biaggi A, Conroy S, Pawlby S, et al. Identifying the women at risk of antenatal anxiety and depression: a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2016;191:62–77.

- Ayers S, Coates R Matthey S. Identifying perinatal anxiety. In: Milgrom J, Gemmill AW, editors. Identifying perinatal depression and anxiety: evidence-based practice in screening, psychosocial assessment and management. Chichester: Wiley Blackwell; 2015. p. 93–107.

- Rubertsson C, Hellström J, Cross M, et al. Anxiety in early pregnancy: prevalence and contributing factors. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2014;17(3):221–228.

- Silverio SA, Easter A, Storey C, et al. Preliminary findings on the experiences of care for parents who suffered perinatal bereavement during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Pregnancy Childb. 2021;21(840):1–13.

- Geller PA, Kerns D, Klier CM. Anxiety following miscarriage and the subsequent pregnancy: a review of the literature and future directions. J Psychosom Res. 2004;56(1):35–45.

- Wojcieszek AM, Boyle FM, Belizán JM, et al. Care in subsequent pregnancies following stillbirth: an international survey of parents. BJOG. 2018;125(2):193–201.

- van den Berg MMJ, Dancet EAF, Erlikh T, et al. Patient-centered early pregnancy care: a systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies on the perspectives of women and their partners. Hum Reprod Update. 2018;24(1):106–118.

- Memtsa M, Goodhart V, Ambler G, et al. Variations in the organisation of and outcomes from early pregnancy assessment units: the VESPA mixed-methods study. Health Serv Deliv Res. 2020;8(46):1–138.

- Memtsa M, Goodhart V, Ambler G, et al. Differences in the organisation of early pregnancy units and the effect of senior clinician presence, volume of patients and weekend opening on emergency hospital admissions: findings from the VESPA study. PLOS One. 2021;16(11):e0260534.

- Hall JA, Silverio SA, Barrett G, et al. Women’s experiences of early pregnancy assessment unit services: a qualitative investigation. BJOG. 2021;128(13):2116–2125.

- Morgan DL. Pragmatism as a paradigm for social research. Qual Inq. 2014;20(8):1045–1053.

- Morgan DL. Paradigms lost and pragmatism regained: methodological implications of combining qualitative and quantitative methods. J Mix Method Res. 2007;1(1):48–76.

- Hawthorne G, Sansoni J, Hayes L, et al. Measuring patient satisfaction with health care treatment using the short assessment of patient satisfaction measure delivered superior and robust satisfaction estimates. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67(5):527–537.

- Irvine A. Duration, dominance and depth in telephone and face-to-face interviews: a comparative exploration. Int J Qual Method. 2011;10(3):202–220.

- Ritchie J, Spencer L. Qualitative data analysis for applied policy research. In: Bryman A, Burgess R, editors. Analysing qualitative data. London: Routledge; 1994. p. 173–194.

- Gale NK, Heath G, Cameron E, et al. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2013;13:117–118.

- Armstrong D, Gosling A, Weinman J, et al. The place of inter-rater reliability in qualitative research: an empirical study. Sociology. 1997;31(3):597–606.

- Campbell JL, Quincy C, Osserman J, et al. Coding in-depth semistructured interviews: problems of unitization and intercoder reliability and agreement. Sociol Method Res. 2013;42(3):294–320.

- Bharathan R, Farag M, Hayes K. The value of multidisciplinary team meetings within an early pregnancy assessment unit. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2016;36(6):789–793.

- Fox R, Savage R, Evans T, et al. Early pregnancy assessment; a role for the gynaecology nurse-practitioner. J Obstet Gynaecol. 1999;19(6):615–616.

- O’Brien N. An early pregnancy assessment unit. Brit J Midwifery. 1996;4(4):187–190.

- Tan TL, Khoo CLK, Sawant S. Impact of consultant-led care in early pregnancy unit. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2014;34(5):412–414.

- Da Costa D, Zelkowitz P, Nguyen T-V, et al. Mental health help-seeking patterns and perceived barriers for care among nulliparous pregnant women. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2018;21(6):757–764.

- Faisal-Cury A, Rossi Menezes P. Prevalence of anxiety and depression during pregnancy in a private setting sample. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2007;10(1):25–32.

- Broquet K. Psychological reactions to pregnancy loss. Prim Care Update OB/GYNS. 1999;6(1):12–16.

- Byatt N, Cox L, Moore Simas TA, et al. How obstetric settings can help address gaps in psychiatric care for pregnant and postpartum women with bipolar disorder. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2018;21(5):543–551.

- Megnin-Viggars O, Symington I, Howard LM, et al. Experience of care for mental health problems in the antenatal or postnatal period for women in the UK: a systematic review and meta-synthesis of qualitative research. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2015;18(6):745–759.

- Ahmed A, Feng C, Bowen A, et al. Latent trajectory groups of perinatal depressive and anxiety symptoms from pregnancy to early postpartum and their antenatal risk factors. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2018;21(6):689–698.

- Poleshuck EL, Woods J. Psychologists partnering with obstetricians and gynecologists: meeting the need for patient-centered models of women’s health care delivery. Am Psychol. 2014;69(4):344–354.

- RCOG. High quality women’s health care: a proposal for change; 2011.

- Coons HL, Morgenstern D, Hoffman EM, et al. Psychologists in women’s primary care and obstetrics-gynecology: consultation and treatment issues. In: Frank RG, McDaniel SH, Bray JH, editors. Primary care psychology. Washington, DC: APA; 2004. p. 209–226.

- Geller PA, Psaros C, Kornfield SL. Satisfaction with pregnancy loss aftercare: are women getting what they want? Arch Womens Ment Health. 2010;13(2):111–124.

- Rayment‐Jones H, Harris J, Harden A, et al. How do women with social risk factors experience United Kingdom maternity care? A realist synthesis. Birth. 2019;46(3):461–474.