ABSTRACT

This case study explores employee perceptions of, and commitment to, continuous improvement in a national public sector organisation. The survey of 593 employees is analysed across four management levels and evidences the employees desire to deliver service improvements and their frustrations across different levels of feeling unsupported and impacted by negative management behaviours. The study shows the areas where there are clear differences between organisational level, sub-cultures and individual commitment around motivation. The findings inform the need to go beyond a simple CI initiative no matter how well structured, ensuring all policies and practices support and reflect the need to shift culture to embed continuous improvement.

Introduction

The challenges for all organisations include the battles against waste and inefficiency and the drive for excellence. Within the public sector such battles continue to be driven in the context of reducing budgets following the global financial crisis of 2007 (HM Treasury, Citation2010) and increasing reform driven by inequality of access, unfairness, and inefficiency (HM Government, Citation2011) in the delivery of such services. These challenges have led to the exploration of approaches and methodologies associated with the private sector being introduced. New Public Management (NPM) emphasised the lessons that could be learned by public sector organisations from private sector organisations (Nclisscn et al., Citation2000).

The drive towards NPM also introduced continuous improvement and quality management methodologies to the public sector and some arguments remain that such methodologies do not translate from private sector to public (Carter et al., Citation2011). At the very least, it is argued that the introduction of private sector methods have impacted on the culture within the public sector (Pillay & Bilney, Citation2015). A further refinement of the debate around the effectiveness of perceived private sector methodologies introduced to the public sector is that due to budget pressures their implementation has been rushed (Papadopoulos & Meralli, Citation2008) or has been too short term and driven by quick wins rather than a sustainable long-term strategy (De Souza & Pidd, Citation2011).

This study is focused on the internal readiness, culture, and motivation within public sector organisations and how these relate to individual employees. Its purpose is to increase understanding of the disposition towards continuous improvement and through this, the provision of ‘value for money’ or ‘making a difference’ in public sector organisations based on outcomes in service delivery informed by public demand (Powell et al., Citation2010) and as such considers whether NPM and associated methodologies have a low cultural fit and limited chance of success due to incompatibility with public sector approaches and values or whether the ways in which they were implemented caused low cultural fit through lack of alignment with strategy or engagement with or empowerment of the workforce. Fundamentally, the question is asked whether NPM and CI methodologies such as lean or Six Sigma can be utilised to drive culture change in public sector organisations as suggested by Radnor and Osborne (Citation2013) and whether this can be kickstarted by identifying and harnessing organisational and associated sub-cultures and the motivation of the employees are already disposed towards delivering value and making a difference and whether this in turn is untapped. Do public sector organisations need to look closer to home to evolve and deliver success in the context of modern challenges?

Theoretical background of the study

This study is concentrated at the intersection of three bodies of knowledge, organisational culture in the public sector, public sector, and service motivation and finally the deployment of CI methodologies in the public sector as shown in ;

It has been historically asserted that culture is best captured by a classification system (Tylor, Citation1987). Where Handy (Citation1991) described his four corporate cultures around organisations embracing;

Power (Zeus) – Top down and centralised power and influence.

Role (Apollo) – Heavily bureaucratic, run defined roles, strict processes, and clear limitations to authority.

Task (Athena) – Small teams with clear tasks orientated towards solutions and results.

Person (Dionysius) – Values orientated supporting the self-actualisation of individuals within the organisation.

While these descriptions can be seen as familiar in practical terms, they can also be seen to not adequately describe the plural cultures that exist in organisations (Willcoxson & Millett, Citation2000). Schein (Citation2010) applies a public sector example to the argument for the importance of sub-cultures describing the doctors, he goes on to suggest that microcultures could be exampled by a group of doctors within a specific location. He goes on to argue that regardless of the business of an organisation, it is important to consider the executive sub-culture, as most managers share similar challenges and concerns as well as the operator sub-culture, the staff on the ‘front-line’ of the business.

Within a public sector context, a longitudinal study within the education sector suggested that a particular facet of public sector culture was that change is very slow, will not occur on its own, and resistance to such culture change can meet significant resistance (Chandler et al., Citation2017). Similarly, the implementation of private sector methodologies as popularised through NPM and exampled in a CI perspective as Lean and Six Sigma are a low cultural fit (Parker & Bradley, Citation2000). Contrasting these challenges, it is asserted that public sector employees are drawn towards their jobs and professions by a sense of duty and desire to make a difference (Perry et al., Citation2010) albeit that while public sector employees are not as motivated by or dependent on extrinsic reward, there does remain a need to consider such rewards and attractions such as job security, pensions, and career paths play a role in the motivation of employees (Perry & Hondeghem, Citation2008). Literature therefore suggests that public service motivation is only one factor in public sector employment.

The body of knowledge around the use of continuous improvement methodologies within the public sector is continuing to grow, with early examples appearing in the literature as early as 2004 in the US and 2008 in the UK (Rodgers & Antony, Citation2019). By 2019, 157 peer reviewed publications across 24 countries were identified (ibid.). However, while much of the body of knowledge provides evidence of the successful deployment of methodologies through case studies of specific projects, their remain significant gaps around the sustained and successful integration of CI methodologies across or within public sector organisations.

It is recognised that some scholars retain the view that NPM and perceived private sector methodologies are not suitable to deliver efficiency or effectiveness in the public sector (Carter et al., Citation2012; Lindsay et al., Citation2014) or at the very least methodologies such as Lean need adaptation and contextualisation for the public sector (Hines et al., Citation2008). However, other scholars express the view that use of CI has been too focused on the deployment of individual tools and techniques which has led to an overreliance on events such as Rapid Improvement (Kinder & Burgoyne, Citation2013; Radnor et al., Citation2012; Radnor & Osborne, Citation2013). It has been further argued that CI has been the subject of rushed implementation focussed on ‘quick wins’ rather than culture change and embedding CI as an integral aspect of the organisations approach to service delivery (Barton, Citation2013; Papadopoulos & Meralli, Citation2008; De Souza & Pidd, Citation2011)

As such, the existing body of knowledge identifies a gap in evidence around the strategic and cultural alignment of CI in deployments in the public sector as well as the use of CI as a system rather than combinations of tools and techniques (Rodgers & Antony, Citation2019). This study explores the intersection of these bodies of knowledge through the understanding and experience of different sub-cultures in relation to a national public sector organisations deployment of CI.

Methods

Research aim

As discussed, this research explores the phenomena of sustained and integrated continuous improvement (CI) within public sector organisations and the gap between strategic intention and perceptions and practice through exploration of employee experience across all levels of the organisation. The following questions are addressed:

What are the employee perspectives on the ways in which CI activities are complemented or inhibited by the organisational culture and values?

Do managerial sub-cultures vary in their perceptions and attitudes to CI?

Is the concept of public sector or public service motivation a factor for employees in their openness, or otherwise, to embedding CI within the organisation?

What are the challenges and opportunities presented by the introduction of CI activities at an organisational wide level?

Public services in Scotland

While some public services are part of the reserved function in the UK government, such as the armed forces or foreign office, functions such as local government, police and fire services, health service, and devolved civil service functions account for 488,000 jobs (Scottish Government, Citation2016). The population of Scotland aged between 16 and 74 is 4 m people (National Records for Scotland, Citation2018) with 2.5 m of those in employment. The public sector accounts for 20% of working adults. The census additionally shows that the largest single industry sector was Health and Social Work accounting for 15% of the working population.

The Scottish Government have additionally shown an interest in continuous improvement methodologies having commissioned a review of the use of Lean in the public sector (Radnor et al., Citation2006) and more broadly commissioned a review of improvement in the Scottish public sector in order to have a more a holistic approach to efficiency and effectiveness of public services and while the financial crisis of 2007 and its consequences were referenced, the key principles which emerged included reform to ‘empower individuals and Communities receiving public services by involving them in the design and delivery of the services they use’, to integrate service provision and to ‘become more efficient by reducing duplication and sharing services wherever possible’ (Christie, Citation2011).

Case study organisation

This paper focuses on a single case study of the Scottish Ambulance Service (SAS) which has operated as part of the National Health Service since 1947. First, it existed as a contracted service to St. Andrews Ambulance Service and since 1974 directly as part of the health service (St. Andrews First Aid, Citation2019). The service currently operates as a special health board and has 4500 employees and an annual budget of around £214 m, the service is overseen by a board whose responsibility it to ensure that it meets its obligations to its patients (Scottish Ambulance Service, Citation2019). Like most public sector bodies in Scotland, Audit Scotland is responsible for auditing the ambulance service through their NHS Scotland responsibilities (Audit Scotland, Citation2019). The largest trade union representing health services and the Scottish Ambulance Service is UNISON (UNISON, Citation2019).

In order to fully understand the context and approach which the organisation takes to CI, a series of four semi-structured interviews were conducted with members of the organisations executive and management board. The interviewees presented a consistent vision for and approach to CI. The organisation has adopted a single tool for organisation-wide improvements by the workforce ‘Plan-Do-Study-Act’ (PDSA) and are of the view that the approach is widespread and embedded in the organisation. As one interviewee stated, the approach has been adopted “ … from front line staff all the way up to board level”. Another member of the executive team stated “I think I can safely say, has now undergone significant cultural change, with continuous improvement being at the heart of everything that we do.” They went on to comment on what they perceived as the length of the journey but also the scale of the improvement culture in the organisation by observing “So, it didn’t happen overnight. Don’t let me pretend it did because it has taken us a long number of years to get to the level, we’re at now. Where I know I could go to any division in Scotland and, if I was to call for improvement posters to be presented to me, I would get 12, 20 in every division, of active work that’s going on right now.”

The executive members presented a clear and consistent view that the embedding of CI was not complete but also was widespread within all levels of the organisation and significant progress towards embedding a culture of CI had been made. The view of the current state of CI can be summarised through one interviewee’s comment, “I have brought that focus into a service which, I think I can safely say, has now undergone significant cultural change, with continuous improvement being at the heart of everything that we do.” The focus of this research is to understand whether this is the experience through all levels of the organisation and whether and how management sub-cultures may experience or perceive this differently.

Research population

The research population was defined as the employees of the case study organisation and consisted of staff at all levels of seniority. A survey was developed using Qualtrics and was piloted in advance of delivery in order to ensure the relevance of each section and question and ensure accessibility. The finalised survey was made available to the whole population through the organisations intranet website and a total of 694 responses were received with 593 of those being fully complete and suitable for analysis.

Data collection

In order to align the survey with the research questions, the sections of the survey are described as;

Organisational Culture and Preparedness for CI

Leadership for CI

Motivation for working in organisation and contributing to CI

Challenges and Opportunities for embedding a culture of CI in the organisation

The survey consisted of a mix of open and closed questions, however the design principle additionally sought to maximise consistency and format of question types (McGuirk & O’Neill, Citation2016) in order to increase usability. As such, closed questions were most commonly formatted as ‘rating’ questions and used a ‘Likert’ format with five option response. The mean result is used for all responses. Each section concluded with an open question allowing respondents to add any additional comment and the final section was comprised only of open questions in order to allow respondents to freely express their views around both challenges and opportunities.

Data analysis

The quantitative data from the survey were analysed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 24 in order to carry out an appropriate range of analysis (Collis & Hussey, Citation2003) in addition to Microsoft Excel which was utilised to create the figures for presentational purposes. The initial consideration for the quantitative data was the internal reliability of the data as it relates to the design and delivery of the survey as well as the participants common understanding of the meaning of the individual aspects of the questionnaire (Bryman & Bell, Citation2015; Cooper & Schindler, Citation2008). Internal reliability was tested using Cronbach’s’ Alpha. The results are presented in . While there are differences in opinion regarding the acceptable values for the test, generally, 0.70 to 0.95 have been deemed to be valid (Bland & Altman, Citation1997; DeVellis, Citation2003; Nunnally & Bernstein, Citation1994), however, tt has been argued that 0.6 to 0.7 is an acceptable level of reliability whereas above 0.7 through to 0.95 is a good or greater indication of reliability (Griethuijsen et al., Citation2014; Ursachi et al., Citation2015).

Table 1. Internal reliability of survey data.

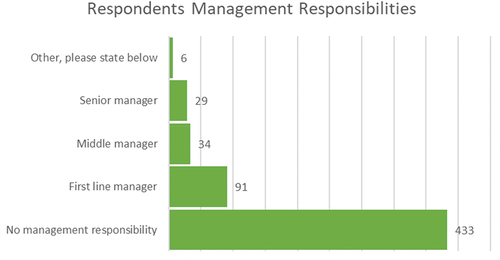

The unit of analysis for the questionnaire was the respondents place within the organisational hierarchy and through this the sub-cultures within levels of management were explored across the organisation. The breakdown of this is shown in .

A further consideration in regard to the analysis of the quantitative data and linked to the research questions as they related to culture, was the relationship between sub-cultures in the organisation as expressed through the hierarchy of management roles within the public sector bureaucracies examined in the case studies. The Kruskal–Wallis test is used to test the differences among three or more independently sampled groups and is an extension of the two group Mann–Whitney test (McKight & Najab, Citation2010). The test can be used to analyse the differences in ranks where the individual groups are different types of managers (Foster et al., Citation2011). Accordingly, the Kruskal–Wallis test was selected to analyse the data from the sub-culture perspective of the managerial hierarchy in order to understand whether there were different perspectives across the group’s themes or question areas of the questionnaire. The qualitative data from the survey was analysed using NVivo 12 Pro.

Results

In this section, the specific findings and answers to the central research questions are presented.

What are the employee perspectives on the ways in which CI activities are complemented or inhibited by the organisational culture and values?

Employee responses as to whether they considered it part of their job to make improvements and whether they had a personal desire to make improvements were analysed. The mean scores of each management groups responses are shown in along with the result of the Kruskal Wallis H test;

Table 2. Breakdown of Employee Perspectives on CI by level of management responsibility.

There can be seen to be a general agreement across all levels of the organisation around a stated desire to improve service to the public. This is suggestive of theories on public service motivation where staff are driven to public service in order to make a difference. However, there can be seen to be a lesser positive viewpoint on internal improvements, where staff are less supportive of process changes or organisational changes if they are not perceived to directly link to service improvement. A clear gap emerges across management perspectives when employees are asked to consider whether it is their job to make improvements. The results of the H test evidence the significance of the differences between the different management groups and show that the distribution is not the same across those groups. This suggests that particularly for front-line employees and their first line managers they share a desire to make improvements but do not see it as their role to do as strongly as their more senior colleagues.

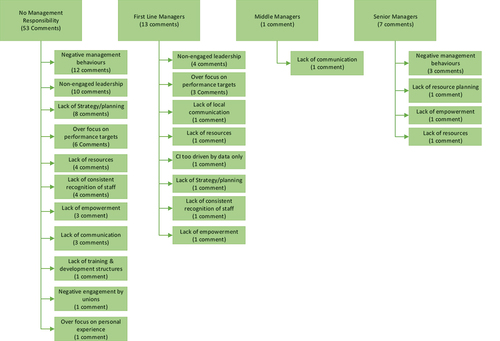

In order to further explore the cultural considerations around CI further, 74 of the respondents provided free text comments in relation to these theme which were analysed and are presented below in as an affinity diagram.

The analysis suggests a clear gap in regard to an existing culture of CI, where although staff perceive themselves to be disposed to making improvements, the organisation lacks positive management behaviours across all levels which would encourage and recognise improvement activity. A negative impact on perceived overfocus on delivering performance targets as well as the lack of an overall improvement strategy and plan are also observed by employees.

From an organisational culture perspective all employees feel strongly that they would like to make improvements but those employees less senior do not strongly feel that it is their role to do so. Exploring this through the qualitative data, the implications are that CI is impeded through a lack of strategy and clear plan and exacerbated by perceived non-engaged leadership and negative management behaviours. Accordingly, leadership and management experiences are further explored in the next section.

Do managerial sub-cultures vary in their perceptions of and attitudes to CI?

The survey explores the increasing organisational commitment to delivering CI from encouraging employees, through to support and ultimately managers actually providing time to make such improvements. These results are presented in .

Table 3.: Breakdown of Employee Perspectives on the leadership of managers in relation to CI.

The H test again clearly shows that each management sub-culture experience is significantly different. It is perhaps notable that what is valued by each staff member in terms of their own managers support for them is less strongly reflected in their own behaviour as a manager. This also raises the connection between employees feeling that CI is not their job and the way in which that belief was either created or reinforced by their line manager not encouraging or supporting their improvement suggestions. This stated, employee responses suggest that the views towards the organisations commitment to CI and its approach to CI are not consistently perceived across the four groups.

Similarly, when asked about how empowered they felt to make improvements in their respective roles, senior managers felt most empowered decreasing through the management levels to those with no management responsibility. This presents a clear gap between levels of management in the organisation where staff do not feel empowered or listened to in suggesting or making improvements in the organisation. Again, this is reflected in the comments presented in where it is clear that the individual experience of CI in the organisation is directly impacted by the individuals seniority in the organisation. This is particularly concerning from a CI perspective in that the person who is most up to date and experienced in delivering a service is most disengaged from improving the service but evidences a desire to do so.

From an organisational perspective it additionally means that any strategy and delivery plan around CI is not invested in the whole organisation and is less visible or accessible as it passes through the hierarchical levels of management.

Is the concept of public sector or public service motivation a factor for employees in their openness, or otherwise, to embedding CI within the organisation?

In seeking to understand the sub-cultures within the organisation and in particular motivations for working for the public sector in general and the case study organisation in particular, respondents were first asked to prioritise their motivation with ‘5’ being the most important or significant reason and ‘1’ being the least important. The results are summarised in .

Table 4.: Breakdown of Employee priorities on working for organisation.

As is suggested by the literature, the concept of making a difference or public service motivation is shown to be the strongest influencer but equally should not be taken in isolation as other factors, most notably, job security are influencers and so it is suggested that such factors should not be taken in isolation but the strength of response around making a difference is an indicator of a pre-disposition of employees of wanting to contribute to CI activities. It can also be seen that the questions around motivation are the first section of the study where the distribution of responses is not influenced by the perspective of different management level within the organisations. In other words, motivation is shown to be down to the individual regardless of seniority. The only consideration where the responses can be grouped by level of seniority is the importance of job security.

In focusing further on actually delivering CI rather than disposition towards making improvements, respondents were also asked how they would seek to be rewarded for delivering improvements. This is intended to further explore the motivation of employees around making contributions, as shown in .

Table 5.: Breakdown of employee preferences for reward & recognition.

Similar to employee reasons for working in the organisation, the expectations of reward and recognition for delivering improvements vary by individual rather than management sub-culture. This adds complexity to the important factor of reward and recognition approaches as it is clear that while all employees expect some form of recognition there cannot be a ‘one size fits all approach and HR policies around promotion, appraisal or employee review and training and development selection all have a part to play in recognising the commitment and contribution of staff, as do individual managers in thanking and supporting their teams.

What are the challenges and opportunities presented by the introduction of CI activities at an organisational wide level?

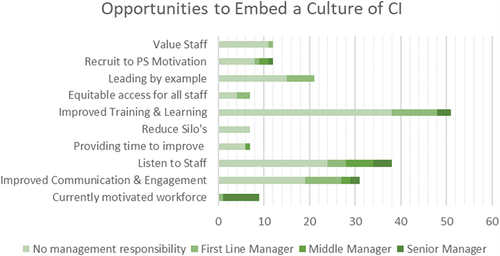

Having considered the employees own beliefs around continuous improvement as well as their expectations around their managers and organisation in terms of support, reward and recognition, It is clear that a gap exists between the executive perceptions of the current culture of continuous improvement and different management levels around the organisation. The survey went on to gather employee perspectives on what opportunities existed within the organisation in order to enhance and embed a culture of continuous improvement. The overview of comments is shown in .

The largest number of respondent comments linked improved staff training and development to enhancing or embedding a culture of CI. Fifty-one comments related to further development of this area creating an opportunity for CI improvement. The only group not to comment in this area was middle managers. The views ranged from specifically course-based learning to carrying out ‘debriefs’ timeously but was most concentrated on localised CPD to support learning and improvement.

The clearest direct opportunity to embedding CI was the defined theme on listening to staff, where thirty-eight comments explicitly stated that staff had the knowledge and desire to improve but the organisation needed to listen and to have clear structures and processes to harvest this data and desire. This is additionally linked to improved communication and engagement where beyond simply listening to staff, comments related to opportunity being created by more clear and increased communication around CI and the ways in which staff could engage and be encouraged to do so. These two areas were commented on by all four staff groups, the only other area where there was comment across all groups was the opportunity to recruit staff with a public sector motivation outlook who were driven to make a difference and had fresh ideas and approaches. This is a broader recommendation for public sector organisations who do not consistently prioritise this in their recruitment (Ritz et al., Citation2016).

Two themes which were very defined by organisational hierarchy were firstly a view that opportunity would be created if managers led by example in the context of CI and empowered staff, were open to ideas, supported staff in implementing those ideas. These comments came from staff with no management responsibility or first-line managers. The second theme, focussed on the view of an existing opportunity to drive CI, which was the senior manager perspective that the organisation had a motivated and committed workforce in terms of delivering services and which should support the implementation of CI.

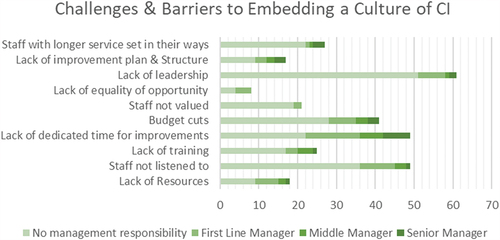

The flip side of this was perspectives on challenges and barriers as summarised in .

The most common response was ‘leadership for CI’ which was commented on by all levels of management within the organisation but accounted for over 20% of all comments made by respondents with no management responsibility. The comments focussed on employee perceived negative behaviours areas such as consistency of message, support for making improvements, leading by personal example and attitudes and behaviours which would not support CI. This theme can also be linked to the perceived barrier on staff feeling that they are not listened to as regards suggestions for improvement or the effectiveness of planned change. The area of most agreement across the management sub-cultures was the view that unless improvement activities are actually built into roles and workloads, there will be no capacity for CI within the organisation.

The comments around staff not feeling valued as well as fairness of opportunity related in particular to reward and recognition and a feeling of a small few within the organisation receiving training and opportunities came in particular from the groups of first-line managers and those with no management responsibility but were not commented on by senior and middle managers. Which again, reinforces the importance of examining multiple sub-cultures and identifying inhibitors which might otherwise not be surfaced.

Overall, all groups additionally commented on external influences and the nature of budget cuts and associated short-term activities to meet financial targets being a barrier to undertaking improvement activity.

Future research

The data presented in this case study is for a single organisation and the generalisation of the findings would be supported by the completion and comparative analysis of further public service organisations.

Conclusion

It is clear from the information and detail presented by the executive staff within the Scottish Ambulance Service that they have identified and supported a CI methodology and have a clear concept of how it is deployed and operated. The purpose of this research was to develop an understanding of the employees commitment to and perception of CI and whether these varied by organisational sub-cultures as exampled by levels of management responsibility. The clear positive outcome from this research is the overall desire by the workforce to make improvements. It is also evidenced that staff feel more drawn to participating in change which is intended to improve the experience or outcomes of the service user, than internal or cost saving improvements. In securing employee commitment to CI this is an important distinction for the purpose and values ascribed to a CI initiative.

This stated, the strength of the commitment lessens as the respondents shift from senior managers to those with no management responsibility. It is also evidenced that there is a difference in the desire to make improvements as well as employees views on whether it is their job to do so. This brings in the consideration of the role of the HR function in the organisation, the job descriptions of all staff and activities such as objective setting as part of any PDR or appraisal process. Clear messaging around responsibility of employees to contribute can support this in particular where the outcome of the survey evidences that the employees strongly wish to improve services.

It is also clear that the most senior employees feel that they are encouraged, listened to and afforded time to make improvements by their managers, but this perception lessens as the staff are less senior. It is of note that the behaviours that individuals value from their managers are exhibited on a diminishing scale through each level of the organisation. This is suggestive of a need to support any CI initiative with leadership and management training, which can support greater empowerment and trust from managers to their teams to further gain the commitment of staff to improvement activity. Staff feeling listened to is a common theme in the barriers and challenges commented on by respondents to the survey.

To this point, there is clear different strength of feeling, viewpoints, and experiences across the four sub-cultures of management levels explored. The desire for reward and recognition for participating in CI activities and the nature that recognition should take is however shown to be a very individual view and is not based on position within the hierarchy of the organisation, the only exception being the desire for additional training. This confirms that reward and recognition is an important aspect of CI but any policy or approach cannot be prescriptive, it also suggests that public sector employees value both extrinsic and intrinsic rewards and so integrates concepts around public service and public sector motivation.

In summary, the outcomes of this research suggest that in order to embed a culture of continuous improvement, a clear improvement strategy or plan is insufficient to deliver such fundamental change and all values, policies, and practices are needed to reflect and support such an initiative for success by ensuring recruitment, training, manager behaviours, staff development processes and so on contribute to the CI intentions. The commitment of leaders and managers is often listed as a critical success factor for CI initiatives (Fryer, Antony & Douglas, Citation2007) this study suggests that the commitment is crucial at every level of management and such managers need to have clear understanding of the expectations on them as well as the tools and knowledge to deliver such commitment. While this is a single case study supported by the existing broader work around critical success factors for CI initiatives, it is argued that while the outcomes may be different, the factors to be investigated and the importance of their exploration is relevant to the wider public sector beyond the ambulance service.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the Scottish Ambulance Service for their support, openness, and transparency in giving access to staff across the organisation for this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Audit Scotland. (2019). About us, Retrieved Feb 12, 2019, from. https://www.audit-scotland.gov.uk/about-us/audit-scotland

- Barton, H. (2013). Lean’ policing? New approaches to business process improvement across the UK police service. Public Money & Management, 33(3), 221–224. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540962.2013.785709

- Bland, J., & Altman, D. (1997). Statistics notes: Cronbach’s alpha. British Medical Journal, 314(7080), 275. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.314.7080.572

- Bryman, A., & Bell, E. (2015). Business research methods (4th ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Carter, B., Danford, A., Howcroft, D., Richardson, H., Smith, A., & Taylor, P. (2011). All they lack is a chain: Lean and the new performance management in the British civil service. New Technology, Work and Employment, 26(2), 83–97. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-005X.2011.00261.x

- Carter, B., Danford, A., Howcroft, D., Richardson, H., Smith, A., & Taylor, P. (2012). Nothing gets done and no one knows why: PCS and workplace control of lean in HM revenue and customs. Industrial Relations Journal, 43(5), 416–432. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2338.2012.00679.x

- Chandler, N., Heidrich, B., & Kasa, R. (2017). Everything changes? A repeated cross-sectional study of organisational culture in the public sector. Evidence-based HRM: A Global Forum for Empirical Scholarship, 5(3), 283–296. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBHRM-03-2017-0018

- Christie, C. (2011). Commission on the future delivery of public services. The Scottish Government Retrieved July 15, 2020, from https://www2.gov.scot/Topics/archive/reviews/publicservicescommission

- Collis, J., & Hussey, R. (2003). Business research: A practical guide for undergraduate and postgraduate students (2nd ed.). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Cooper, D. R., & Schindler, P. S. (2008). Business research methods (10th ed.). McGraw-Hill.

- de Souza, L. B., & Pidd, M. (2011). Exploring the barriers to lean health care implementation. Public Money & Management, 31(1), 59–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540962.2011.545548

- DeVellis, R. (2003). Scale development: Theory and applications: Theory and application. Sage.

- Foster, S. T., Jr, Wallin, C., & Ogden, J. (2011). Towards a better understanding of supply chain quality management practices. International Journal of Production Research, 49(8), 2285–2300. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207541003733791

- Fryer, K.J., Antony, J., & Douglas, A. (2007). Critical success factors of continuous improvement in the public sector: A literature review and some key findings. The TQM Magazine, 19(5), 497–517. https://doi.org/10.1108/09544780710817900

- Griethuijsen, R. A. L. F., Eijck, M. W., Haste, H., Brok, P. J., Skinner, N. C., & Mansour, N. (2014). Global patterns in students’ views of science and interest in science. Research in Science Education, 45(4), 581–603. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11165-014-9438-6

- Handy, C. (1991). Gods of management: The changing work of organisations. Business Books.

- Hines, P., Martins, A. L., & Beale, J. (2008). Testing the boundaries of lean thinking: Observations from the legal public sector. Public Money & Management, 28(1), 35–40. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9302.2008.00616.x

- HM Government. (2011). Open public services white paper. Retrieved Feb 12, 2017, from https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/open-public-services-white-paper

- HM Treasury. (2010). Spending review 2010. Retrieved Feb 12, 2017, from, from https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/spending-review-2010

- Kinder, T., & Burgoyne, T. (2013). Information processing and the challenges facing lean healthcare. Financial Accountability and Management, 29(3), 271–290. https://doi.org/10.1111/faam.12016

- Lindsay, C., Commander, J., Findlay, P., Bennie, M., Dunlop Corcoran, E., & Van Der Meer, R. (2014). Lean, new technologies and employment in public health services: Employees’ experiences in the National Health Service. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 25(21), 2941–2956. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2014.948900

- McGuirk, P. M., & O’Neill, P. (2016). Using questionnaires in qualitative human geography. In I. Hay (Ed.), Qualitative research methods in human geography (pp. 246–273). Oxford University Press.

- McKight, P. E., & Najab, J. (2010). Kruskal‐Wallis test. In I. B. Weiner, and W. E. Craighead (Eds.), The corsini encyclopedia of psychology, 1-1. Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470479216.corpsy0491

- National Records for Scotland. (2018). Labour Market. Retrieved Feb 03, 2020, from https://www.scotlandscensus.gov.uk/labour-market

- Nclisscn, N., Denhardt, R. B., & Lako, C. J. (2000). The pursuit of significance. Public Management an International Journal of Research and Theory, 2(2), 219–238. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719030000000011

- Nunnally, J., & Bernstein, L. (1994). Psychometric theory. McGraw-Hill.

- Papadopoulos, T., & Meralli, Y. (2008). Stakeholder network dynamics and emergent trajectories of lean implementation projects: A study in the UK National Health Service. Public Money and Management, 28(1), 41–48. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9302.2008.00617.x

- Parker, R., & Bradley, L. (2000). Organisational culture in the public sector: Evidence from six organisations. International Journal of Public Sector Management, 13(2), 125–141. https://doi.org/10.1108/09513550010338773

- Perry, J. L., Hondeghem, A., & Wise, L. R. (2010). Revisiting the motivational bases of public service: Twenty years of research and an agenda for the future. Public Administration Review, 70(5), 681–690. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2010.02196.x

- Perry, J. L., & Hondeghem, A. (2008). Motivation in public management;. Oxford University Press.

- Pillay, S., & Bilney, C. (2015). Public sector organisations and cultural change. Palgrave MacMillan.

- Powell, M., Greener, I., Szmigin, I., Doheny, S., & Mills, N. (2010). Broadening the focus of public service consumerism. Public Management Review, 12:3(3), 323–340. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719030903286615

- Radnor, Z. J., Holweg, M., & Waring, J. (2012). Lean in healthcare: The unfilled promise? Social Science and Medicine, 74(3), 364–371. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.02.011

- Radnor, Z., & Osborne, S. P. (2013). Lean: A failed theory for public services. Public Management Review, 15(2), 265–287. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2012.748820

- Radnor, Z., Walley, P., Stephens, A., and Bucci, G. (2006). Evaluation of the Lean Approach to Business Management and its use in the Public Sector. Available at: https://www2.gov.scot/resource/doc/129627/0030899.pdf. (Accessed on June 18, 2021).

- Ritz, A., Brewer, G. A., & Neumann, O. (2016). Public service motivation: A systematic literature review and outlook. Public Administration Review, 76(3), 414–426. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12505

- Rodgers, B., & Antony, J. (2019). Lean and Six Sigma practices in the public sector: A review. International Journal of Quality & Reliability Management, 36(3), 437–455. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJQRM-02-2018-0057

- Schein, E. H. (2010). Organisational culture & leadership (4th ed.). Jossey-Bass.

- Scottish Ambulance Service. (2019). The service. Retrieved Feb 09, 2019, from https://www.scottishambulance.com/theservice/Default.aspx

- Scottish Government. (2016). Public sector employment in Scotland statistics for 4th Quarter 2015

- St. Andrews First Aid. (2019). Our History. Retrieved Feb 10, 2019, from. https://www.firstaid.org.uk/charity/about-us/history/

- Tylor, E. B. (1987). The science of culture. In H. Applebaum (Ed.), Perspectives in cultural anthropology (p. 43). State University of New York Press.

- UNISON. (2019). About. Retrieved Feb 09, 2019, from http://www.unisonpolicestaffscotland.org/about/

- Ursachi, G., Horodnic, I. A., & Zait, A. (2015). How reliable are measurement scales? External factors with indirect influence on reliability estimators. Procedia Economics & Finance, 20, 679–686. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2212-5671(15)00123-9

- Willcoxson, L., & Millett, B. (2000). The management of organisational culture. Australian Journal of Management and Organisational Behaviour, 3(2), 91–99.