Abstract

E-assessment typically seeks to improve assessment designs through the use of innovative digital tools. However, the intersections between digital technologies and assessment can be seen as increasingly complex, particularly as the sociotechnical perspectives suggest assessment must be relevant to a digitally-mediated society. This paper presents an organising framework, which articulates this nuanced relationship between the digital and assessment design. It draws together literature from diverse domains, including educational technologies, assessment pedagogies and digital literacies. The framework describes three main purposes for designing the digital into assessment: 1) as a tool for improvement; 2) as a means to develop and credential digital literacies; and 3) as a means to develop and credential uniquely human capabilities. Within each purpose, it offers considerations for assessment and feedback design. In addition, it offers researchers analytical tools to understand the role of the digital in assessment. The framework seeks to connect assessment and feedback design to the digital world, and in so doing ensure that higher education will be relevant for graduates’ digital futures.

Introduction

Digital technologies have transformed society, but assessment design may not have kept pace with the digital world. Educational technologies tend to reproduce established academic practices (Selwyn Citation2014) and, while there may be new means of implementation, such as learning management systems or online proctoring, the fundamentals of assessment design appear to remain constant (Bearman, Boud, et al. Citation2020). This is exemplified by current research. For example, Slade et al. (Citation2021, 15) report that, during the pandemic, the necessary move to purely digital assessment formats took place with “little change” to disciplinary practices. This suggests that educators may only engage instrumentally with the digital. However, for assessment to be fit for educational purpose, it should reflect contemporary society. Therefore, there is a need to prompt educators and researchers to consider how assessment and feedback designs can connect our students to a digital world.

University teachers consider technology-supported assessment to be “contemporary and innovative” (Bennett et al. Citation2017, 676) and this view is likely be a key driver for many technology-based assessment designs. However, technology in and of itself is not a panacea, it needs to take account of the complex social realities of educational practice (Kearsley Citation1998; Selwyn Citation2010). According to Bayne (Citation2015, 17), educational technologies are “generally described in instrumental or essentialist terms which either subordinate social practice to technology or subordinate technology to social practice”. At the same time, assessment designers and assessment researchers cannot ignore digital technologies. Technological innovations do allow assessment designs to function in ways that they could not do before. Some kinds of assessments are no longer relevant to contemporary workplaces which are immersed in digital technologies. This paper therefore offers an organising framework to aid navigating the complex intersections between a digital world and assessment design.

A challenge facing researchers and practitioners is the debate surrounding the term “technology” within educational settings (Bayne Citation2015): a choice of words can imply particular usages that restrict shared understandings (e.g. computer-assisted, computer-based, etc). This paper therefore offers an alternative discourse: we use the term ‘the digital’. This reflects the duality of the digital being both a technology and a social practice. The digital therefore also encompasses practices that are necessary for living with technology, such as for example teamwork and collaboration, that do not in and of themselves focus on using technology. The phrase designing the digital into assessment reflects our primary intention: to support the development of assessment designs relevant to a digital world.

Overview of research into assessment and digital technologies in higher education

For many years, the intersection between the digital and assessment has commonly been taken to mean e-assessment: “all the assessment tasks using a computer or the Web” (Guàrdia, Crisp, and Alsina Citation2017, 38). The literature provides many implicit and explicit ways of categorising this work. The most common frameworks appear to rely on assessment task format (e.g. quizzes, virtual simulations and peer assessment software (see Guàrdia, Crisp, and Alsina (Citation2017) or Jisc resources (jisc.ac.uk)). Another organising principle is by approach to testing; for example, a simple quiz or a highly sophisticated ‘intelligent’ system’ (Guàrdia, Crisp, and Alsina Citation2017). Overall, the emphasis of these frameworks is on practical improvement or more efficient performance.

The focus on practicalities means frameworks do not distinguish between a particular intentional use of technology within an assessment design and the pervasive technology-mediated presentation of all assessments. For example, while broad definitions of e-assessment look beyond the task to the “end-to-end assessment process from the perspective of learners, tutors, learning establishments, awarding bodies and regulators, and the general public” (Jisc Citation2007, 6), this continues to focus on what might be called ‘use cases’. Therefore, e-assessment is often categorised by purpose such as plagiarism detection or reporting results (Pachler et al. Citation2009). Moreover, according to the broadest definition, e-assessment now includes almost all assessment designs. For example, almost all universities record grades electronically and learning management systems (LMSs) commonly present assessment tasks.

In addition to the e-assessment literature, which focusses mostly on assessment of learning or summative assessment purposes (Mimirinis Citation2019), there is a parallel and diverse literature exploring the role of technology in feedback processes. For example, the employment of video for delivering comments has been well-explored (Mahoney, Macfarlane, and Ajjawi Citation2019), and the learning analytics literature is increasingly concerned with feedback (Pardo et al. Citation2019; Shibani, Knight, and Buckingham Shum Citation2020). Again, the emphasis is on practical improvement and efficiencies. While there is an acknowledgement that managing technology must be part of teacher and student feedback repertoires (Carless and Boud Citation2018; Wood Citation2021), this literature does not consider the broader context of how assessment and feedback might be designed for a digital world. To explore this further, we articulate what we mean by assessment and assessment design.

Orientation towards assessment and assessment design

Our orientation towards assessment takes a holistic view. We consider assessment takes place any time a judgement is articulated about student work or performance (Bearman et al. Citation2016). This judgement can be derived from educator, student, self or machine and can lead to grades or insights about the work. Educators ideally design opportunities for assessment across a unit of study or an entire program.

We also take a holistic view of assessment design. Assessment design concerns the materials associated with describing singular assessment tasks, associated feedback design, grading processes, and how the various assessment elements work in relation to each other. Here, we go beyond a task genre (e.g. quiz, essay) to the specific assessment designed for a unique time and place. Educators design assessments influenced by their circumstances, such as their disciplines and their relationship with colleagues and infrastructure (Bearman et al. Citation2017). These circumstances also affect how educators work with technology in their assessment designs, responding to their perceptions of the costs, student responses, their desire to be innovative and how they managed logistical challenges (Bennett et al. Citation2017).

These studies reinforce the notion that assessment and technology are not a-contextual but are shaped by the circumstances of their use. For example, an educator employs an online quiz because the LMS has an easy-to-use tool and there is limited budget for markers, rather than coming to the idea as a neutral design solution. We also note that this focus on design does not include what the students actually do to fulfil the assessment task, such as work in virtual study groups, searching the Internet or completing a task in the LMS, but rather what the teachers intend (Goodyear, Carvalho, and Yeoman Citation2021). Finally, even though our framework places educators as central, we note they are not always the only designers of assessment. For example, student partnership in co-designing assessment has been increasingly noted in research literature (e.g. Matthews et al. Citation2021).

The need for an organising framework

Our view is that educators and researchers alike can benefit from explicitly and critically considering the role of the digital within assessment design. In Bennett et al.’s (Citation2017) study, university educators describe two main reasons for employing digital technology as part of assessment design. Firstly, they see it providing efficiencies (real or imagined). Secondly, they describe its innovative nature and the need to be “contemporary”. However, beyond this work, there is a striking absence in the literature. Moreover, there is little information to guide educators who wish to take account of the digital in assessment design. While there are helpful well-known educational technology and assessment frameworks, the former do not appear to focus on assessment and the latter do not appear to consider the digital.

This paper proposes an organising framework for understanding the multiple and overlapping reasons to purposively consider the digital in relation to assessment design. We elaborate how a deliberate focus on particular aspects of the digital can prompt assessment design relevant to a digital world. We call this an organising framework because it draws together other helpful assessment and educational technology frameworks and/or categories, where relevant. Before we outline this framework, we briefly comment on the role of digital platforms.

The role of digital platforms in assessment design

While we are mostly concerned with deliberately designing the digital into assessment, we live in a digitally-mediated society. Therefore, almost all university assessment and grading relies on software and hardware platforms. Drawing from Bogost and Montfort (Citation2007, 176), we consider digital platforms to be the software and hardware “that supports other programs”. In this way, digital platforms are those which assessment designers cannot alter; educators must employ this software and hardware irrespective of assessment design. Examples include using software to detect plagiarism, learning analytics to predict at-risk students, and even uploading student grades into student record systems. While these digital platforms can be changed, generally speaking they are fixed constraints that educational designs need to take into consideration (Bearman, Lambert, and O’Donnell Citation2021). We therefore do not include these software platforms within our proposed framework but treat them as part of the general context for assessment design, alongside policies and departmental norms (Bearman et al. Citation2017).

Assessment design in a digital world: an organising framework

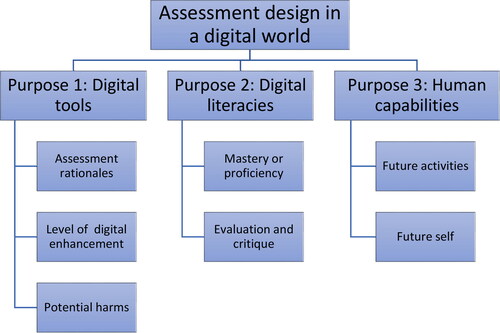

We now detail an organising framework for designing the digital into assessment. It is divided into three purposes as outlined within . The first purpose focusses on employing the digital – as a tool to support better assessment. The second purpose considers how assessment should concern engaging with digital technologies as a key part of modern society, that is to develop students’ digital literacies. The third purpose looks to how students increasingly need to develop uniquely human capabilities to complement the work that digital technologies will be performing into the future. These purposes can be held simultaneously and elements can be in tension. Under each purpose, we outline considerations that can assist educators and researchers in conceptualising why and how they will design assessments in a digital world.

This organising framework is based on extensive reading of the digital assessment literature, the e-assessment literature, our own expertise as assessment researchers and digital education researchers, and finally from our own experiences as educators who have employed digital technologies within assessment designs. We developed the three purposes and underlying themes iteratively, drawing from existing assessment and digital technology frameworks to help understand the complexities underpinning assessment within a digital world, including ethical concerns (Bearman, Dawson, et al. Citation2020). It is intended to inform assessment designs by embracing both a sociotechnical and a practical view of the digital. We now describe each of the three purposes and their associated considerations in turn.

Purpose 1: Digital tools for better assessment

This first and most obvious purpose for employing digital technologies is as a tool to improve assessment or assessment processes, including feedback. This purpose appears both self-evident and predominant. For example, educators design digitally-mediated assessment tasks, such as e-portfolios, wikis, video tasks and so on, to improve student learning through assessment. Similarly, they incorporate digital tools, such as automated grading, to make assessment processes more efficient. However, the nature of this improvement is often not well articulated. Therefore, within this broad purpose, we distinguish three areas of consideration for assessment designers: assessment rationales, level of digital enhancement and potential harms. provides key questions associated with these considerations.

Table 1. Key considerations related to using digital tools to enhance assessment design.

Assessment rationales

The first consideration is to articulate the overall rationale for the assessment, to ensure the employment of the digital aligns with these intentions. We follow Boud and Soler (Citation2016) in describing three rationales for employing assessment. The first is to credential a student through demonstrated attainment, often called assessment of learning. The second rationale is to promote student development through completing the assessment task, often called assessment for learning. The third rationale is to ensure the assessment leads to longer term development for the student. This is generally called sustainable assessment and is associated with building the students’ evaluative judgement. Evaluative judgement enables the student to learn standards and qualities associated with the assessment task, which can promote development once they complete the formal unit of study (Tai et al. Citation2018).

These rationales can align or be in tension with each other; thus, any design decision should consider how these rationales relate to one another (Bearman et al. Citation2016). Educators should reflect upon how the digital aligns with these intentions. For example, an educator who is most interested in a task that emphasises sustainable assessment might ask students to curate an e-portfolio of authentic skills used in practice. However, another educator, who needs to satisfy professional accreditation requirements, might reflect that assessment of learning is the most important focus. They would hence design an online viva format with high assessment security and increased efficiency relative to a face-to-face option.

Level of digital enhancement

The next consideration revolves around how the technology is employed to fulfil the educators’ objectives. Drawing from the general educational technology literature, we describe the substitution, augmentation, modification and redefinition (SAMR) framework, which offers a useful way of articulating the purposeful integration of the technological tool into task design. SAMR divides the uses of technology into a four-level hierarchy (Puentedura Citation2009) of increasing pedagogic enhancement.

At the first level of SAMR, educators use the technology as substitution for a non-technological task, although employing a new digital technology now usually means replacing another. For example, consider a multiple-choice examination which exchanges a machine-readable book to one where questions are asked via a tablet. This new design simply substitutes an older technology (pen, paper and optical scanner) for an alternative (digital presentation). There is no fundamental change in what students are asked to do, although frequently, as in our example, it may be more efficient. The next level is augmentation, where the task mostly remains the same, but it is enhanced by the technology. Drawing from the example above, this might be when the tablet randomly selects different multiple-choice questions or provides students with automated pre-populated feedback following the examination. The third level is modification, which presents a substantially different task: for example, the test items adapt to the students’ choices, hence allowing the examination to be based around authentic and challenging scenarios. The fourth level, redefinition, means that a digital task provides a completely different way of working. In our example, the examination format could be replaced by an online simulation where teams of students “role-play” stakeholders addressing a complex real-world scenario, such as damming a major river system (Hirsch and Lloyd Citation2005).

SAMR allows educators to consider how innovative their use of the digital actually is. Without overlooking the value of increased efficiency, it is useful particularly for researchers to consider how new assessment designs can transform what students do. For example, an e-portfolio that allows students to track and visualise their feedback over time (Winstone Citation2019) represents a digital tool that utilises technology to assemble different sources of information (e.g. images, video, voice recordings, social media) in a way that is readily accessed by broader professional communities.

Potential harms

The final consideration when employing a digital tool to improve assessment design is to acknowledge the potential for harm as well as the benefits. As mentioned, technology is usually associated with a belief that innovation will make a positive difference or, at least, that it will be neutral. For example, there is no SAMR category describing how the digital might make the student experience worse not better. This is a limitation associated with this purpose: if you are intending to develop an improvement, it becomes easy to forget that technologies can have unintended and unproductive impacts, such as steering instrumental student behaviours (Henderson, Selwyn, and Aston Citation2017). For example, an online proctoring program may enhance assessment security but simultaneously negatively impact student experience through raised anxiety levels (Woldeab and Brothen Citation2019). Similarly, inaccessible assessment designs are a serious concern – no matter how innovative or transformative – as they might further exclude students with disabilities.

Avoiding these challenges may be impossible in the first instance as harms may only become apparent when students complete an assessment task. However, as assessment designs tend to be iterative (Bearman et al. Citation2017), evaluating for initial unintended negative impacts (and incorporating findings into future designs) becomes very important. This requires a shift from a romanticised view of technology-mediated assessments (Bennett et al. Citation2017) to a more nuanced perspective. The corollary to this is that such articulation of harms should be more commonly reported in scholarly forums and publications.

Purpose 2: Developing and credentialling digital literacies

The second purpose for designing the digital into assessment is to promote and credential how students engage with technologies. In this instance, the assessment design is aligned with learning outcome(s) that specifically concern how students engage with digital technologies. We use the term digital literacies as this appears to be a commonly employed label. However, we encompass a large body of work including “digital literacy”, “digital fluency”, “digital competencies” and “data literacies”. Central to this purpose is that higher education can intentionally teach technologically-focussed ways of knowing and doing and that this is a matter for assessment design. In other words, digital literacies also require assessment and feedback, the same as any other form of teaching.

Assessment and feedback do not feature heavily in the discussion of digital literacies in higher education (Littlejohn, Beetham, and McGill Citation2012) and, similarly, research on assessment literacies rarely explicitly address the role of digital technologies (e.g. Smith et al. Citation2013). However, there is an extensive body of work on digital literacies in general higher education, including two recent systematic reviews. These describe how digital literacies range from specific skills in using particular software programs (Spante et al. Citation2018) to developing complex modes of meaning making (Lea and Jones Citation2011) to surfacing the impacts of datafication surveillance (Raffaghelli and Stewart Citation2020). Spante et al.’s (Citation2018) review suggests that conceptions of literacies are broad-ranging and indeed ambiguous, while Raffaghelli and Stewart (Citation2020) suggest that particular terms such as ‘data literacy’ often lend themselves to instrumental views. From the school sector, Pangrazio and Sefton-Green (Citation2021) distinguish two categories of digital literacy: “mastery and operational proficiency” and “evaluation and critique”. These are not binary; some forms of mastery may be necessary for critique, and arguably mastery necessarily entails some level of evaluation. However, we use these two approaches to prompt considerations for assessment design ().

Table 2. Key considerations related to developing and credentialling digital literacies.

Mastery or proficiency

Those designing digital in assessment may wish to consider how their designs build mastery or proficiency with respect to digital literacies. For example, Reyna, Hanham, and Meier (Citation2018) describe an assessment designed to promote and evaluate digital media literacies through tasks such as preparing a public health information brochure. This has an operational proficiency focus: the assessment task requires the student to develop an approach that will convey the appropriate information, through effective use of the software tools and visual design principles. On a less instrumental note, O’Donnell (Citation2020) proposes that digital assessment designs should ideally prompt knowledge creation rather than replication or consumption; for example, mastering knowledge production with blogs, wikis and social media.

Development of digital literacy skills and capabilities is sometimes regarded as an incidental side-effect of a digital assessment design. For example, students uploading videos as part of their assessment are assumed to enhance their digital skills (Scott and Unsworth Citation2018). However, if digital literacies are an outcome that is developed and judged through assessment, then the program must support the development of these capabilities. Educators should not assume that by undertaking a particular task, students will osmotically master digital skills. Thus, digital literacies must be incorporated in some form into teaching. It is unfair to expect outcomes based purely on what learners bring to a course of study; assumed digital literacies can form barriers for equity groups (Wickens and Miller Citation2020).

Evaluation and critique

Another consideration for assessment design is how to promote students’ capability to evaluate and critique the digital. This presents an opportunity. While critical approaches to digital literacies are very rare within the assessment literature they are more frequently seen within the data literacies literature, prompted by concerns about the rising integration of big data and artificial intelligence techniques into society (e.g. Pangrazio and Selwyn Citation2019; Williamson, Bayne, and Shay Citation2020). An assessment design example is within a Masters of Digital Education, where students interact with presentations of their own digital data, critically reflecting on how educational data is synthesised and communicated (Knox Citation2017). In this instance, the critical reflections about data form a key part of assessment design.

Purpose 3: Developing and credentialling human capabilities for a digital world

The last purpose focusses on the broader capabilities, beyond digital literacies, required for living and working in a digital world. These capabilities can be distinguished by their emphasis on uniquely human characteristics: human contributions to society that cannot be performed by autonomous machines. In this way, Aoun (Citation2017) suggests that developing students’ creativity and collaboration may be more important than learning procedural programming skills. If we have defined digital literacies as technologically-focussed ways of knowing and doing, we can distinguish these other capabilities as ways of knowing, doing and being within a digitally-mediated society. The emphasis in this purpose is assessment designs that promote or credential living and working within a digital world, rather than focussing on digitally-mediated activities. This invokes the notion of ‘authentic’ assessment design, that is tasks that are directly relevant to broader society, most frequently, professional work contexts. We also suggest assessment designers should consider ‘future-authentic assessment’ that represents the “likely future realities” (Dawson and Bearman Citation2020, 292).

This is the least described purpose in the assessment literature, with almost no examples of actual task designs. We therefore elaborate more fully. We first briefly outline the well-known twenty first century skills literature and then distinguish what we mean by uniquely human capabilities for a digital world.

There is a resemblance between ways of knowing, doing and being within a digitally-mediated society and what are often called “twenty first century skills”. The latter were conceptualised in the last few decades of the twentieth century (Bybee Citation2009). At this time, it was recognised that knowledge production was accelerating exponentially and routine cognitive and mechanical work would be increasingly assumed by machines; education should therefore develop skills necessary for an increasingly automated world. The types of domains included within twenty first century skills, in addition to digital literacies, are collaboration, communication, citizenship, creativity, critical thinking, problem-solving and developing quality products (Voogt and Roblin Citation2012). These also appear similar to the types of graduate attributes, often called generic attributes, that universities seek to develop within their students. We wish to distinguish the uniquely human capabilities explicitly linked to a digital world from these generic twenty first century skills notions of creativity or critical thinking.

We define uniquely human capabilities for a digital world as those capabilities which can be conceptualised differently from pre-digital times. By human capability, we mean "an integration of knowledge, skills, personal qualities and understanding used appropriately and effectively-not just in familiar and highly focused specialist contexts but in response to new and changing circumstances" (Stephenson Citation1998, 2). We are interested in those that are unique to the digital world. For example, problem-solving is a well-known twenty first century skill that has not shifted over the last century, but new capabilities are required for synthesising an increasing flood of digitally-mediated information. While there are digital literacies involved, such as understanding how text search algorithms work, there are also ways of knowing and doing and being now needed to construct knowledge from this oversupply of information.

We offer two considerations for assessment designers, with respect to developing capabilities for 1) future activities and 2) future self. As with digital literacies, we note that teaching, feedback and assessment must be aligned here: an assessment task in and of itself will not build these types of capabilities without being deeply embedded within a curriculum (and experienced by students as such). offers prompting questions for educators.

Table 3. Key considerations related to developing and credentialling human capabilities for a digital world.

Future activities

The first consideration for assessment designers is to reflect on how a digital world impacts upon our students’ future activities beyond developing digital literacies. For example, Bearman and Luckin (Citation2020) describe how assessment might respond to the rise of artificial intelligence (AI) as a fundamental part of our society. In particular, they note that AI has some significant deficiencies: machines cannot define quality or set standards. Therefore, assessment designs that focus on promoting the uniquely human capability of defining quality or setting criteria may become more significant for a digital world (Bearman and Luckin Citation2020).

This example underlines how the uniquely human capabilities that students need for a digital world are not necessarily about directly engaging with the digital. Designing the digital into assessment sometimes means anticipating a sociotechnical context rather than predicting the affordances of particular technologies. This sustainable approach underlines that every assessment task has the potential to address the complexities of learning, working and living in a digital world.

Future self

A sense of self is a human characteristic, not possessed by machines in the foreseeable future. Therefore, we suggest that educators should consider how assessment can orient students towards a future self in a digital world. Such assessment designs emphasise what students are becoming rather than what they are doing or will do in the future. For example, an assessment can ask students to dynamically and strategically construct a professional self within relevant online social networks and communities (Ajjawi, Boud, and Marshall Citation2020). Thinking in this way offers untapped potential for assessment design. For example, diverse human characteristics (which include family commitments, disabilities or previous life experiences) are sometimes framed as deficits that require assessment adjustments. Assessments that incorporate students’ developing sense of self offer a way to reframe diversity as uniquely human and therefore particularly meaningful within a digital world.

The organising framework in use: supporting assessment design

This framework is intended to assist educators in designing assessments to take account of a digital world. The literature tends to emphasise employing technologies to develop better assessment, but by using this framework educators can also make additional technology-related design choices. By offering key considerations around three purposes, assessment design can both employ technology as a tool and integrate sociotechnical dimensions. We note three advantages. Firstly, the framework integrates key concepts from two different literatures: digital technologies and assessment design. Secondly, the framework provides a means whereby educators can make their assessments digitally authentic – that is reflective of the technologies and skills required for an (already) digital world. Finally, this approach shifts developing students’ literacies and capabilities from an implicit part of assessment design to highlighting these as necessary learning outcomes within a digital world.

We anticipate the framework will be used prospectively to guide new assessment designs, as well as retrospectively for iterative improvement. We now review one of our own assessments to illustrate how using the framework may play out in practice.

Illustrative case example: e-portfolio in pre-service teacher education

In this example, we review an implementation of an e-portfolio: a form of assessment that enables students to demonstrate their learning in diverse and multimodal ways (e.g. text, video, images). Our case is set in a masters level course about digital assessment in mathematics education (approximately 20 students), taught by JHN (second author) and Dr Matti Pauna at the University of Helsinki in 2018. The e-portfolio was intended to be an example of authentic assessment. Students were asked to provide four predetermined artefacts:

A research-based assessment plan for one (imaginary) learning unit/subject.

A formative assessment task for secondary school mathematics, including feedback design.

A digital self or peer-assessment form (linked to a mathematical learning goal).

A small collection of mathematical tasks conducted in the authentic digital matriculation examination environment with digital feedback.

Everyone who returned all the artefacts passed the course. Teachers provided written comments on the e-portfolios to develop them for actual use beyond graduation.

Reviewing the e-portfolio using the framework

We commence the review by noting that the e-portfolio was employed as a digital tool for better assessment. As intended, its format aligned with a sustainable assessment rationale: students demonstrated their skills in diverse digital and authentic ways, including authentic digital artefacts such as assessment plans and digital, formative assessment tasks. The students experienced first-hand the affordances of such an assessment design which hopefully transferred to their own future classroom practice. The digital nature of the e-portfolio format enabled multiple enhancements (and possibly transformations) relative to a physical portfolio; it was transportable, dynamic, multimodal and able to store large volumes of information in a stylish, presentable manner. However, in using the framework to review this assessment, we noted that the original design did not consider potential harms. In coming to use such a design again, we would review the impact that the digital technologies had on students. These might be issues such as frustrations with constrained choices and clunky software, or difficulties with equity access due to internet speed.

The e-portfolio design explicitly embraced the second purpose of developing students’ digital literacies from a mastery perspective. From the beginning of the course, it was emphasised to students that both the learning artefacts and the portfolio design represent authentic, digital tools needed for future professional practice. For example, an explicit learning outcome for completing the portfolio was to learn to use the digital matriculation system used in Finnish high schools. Therefore, we stipulated that one of the artefacts include evidence of their design of tasks through this system. However, again we noted in our review that this design could have highlighted critique more strongly. The then-recent high school reform digitized the matriculation examinations in Finnish high schools, ultimately placing stronger emphasis on test results in the digitized matriculation examination, and especially in mathematics. While this problem was implicitly encountered, we could have incorporated this aspect more strongly in the overall design through requiring submission of reflective artefacts.

The final purpose of building human capabilities for a digital world revolved around developing students’ digital professional identities and their career narratives. While we reflected upon its incorporation, the consideration of future activities did not lead to changes to the assessment design. However, we noted that the students were already encouraged to build a portfolio that constructs their future selves through developing their personas as future professional educators. Personas are strategic constructions of self for a specific audience through, for example, building digital networks within the disciplines that the student seeks to join (Ajjawi, Boud, and Marshall Citation2020). The e-portfolio supported their student employability through the sharing of their portfolio in social media and in so doing the students constructed their identities within future potential communities.

This example illustrates both the three purposes and how the framework can be used to highlight strengths and opportunities in an assessment design. It also shows how not all considerations need to be addressed in every assessment design, but that the process of engaging with the framework surfaces awareness of purpose and offers opportunities for improvement.

The organising framework in use: supporting assessment research

We believe this framework also has value for those researching the intersection of the digital and assessment design. It provides options for analysis and hence invites research into different purposes for designing the digital into assessment. Valuable areas of future research might be investigating the tensions between the purposes; in our case example there was an interesting tension between the authenticity of the e-portfolio artefacts and providing digital literacy skills that supported future employability. Moreover, we suggest that the negative unintended consequences of technology are generally underacknowledged and this may be particularly true for assessment. This forms a very important area for future research.

Conclusions

In this paper, we have presented an organising framework for employing the digital in assessment design. In so doing, we join multiple relevant literatures into three purposes: 1) digital tools for better assessment; 2) building and credentialling digital literacies; and 3) building and credentialling human capabilities for a digital world. The framework provides a means to design the digital into assessment, an increasing necessity for higher education within a digital world.

Declarations and ethics statements

This is a conceptual article and does not need ethical approval, informed consent and has no data to store. The authors have no competing interests and this paper was not funded. We acknowledge the invaluable comments from Professor Phillip Dawson during drafting.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Ajjawi, R., D. Boud, and D. Marshall. 2020. “Repositioning Assessment-as-Portrayal: What Can We Learn from Celebrity and Persona Studies?” In Re-Imagining University Assessment in a Digital World, edited by M. Bearman, P. Dawson, R. Ajjawi, J. Tai, and D. Boud, 65–78. Switzerland: Springer.

- Aoun, J. E. 2017. Robot-Proof: Higher Education in the Age of Artificial Intelligence. Cambridge MA: MIT press.

- Bayne, S. 2015. “What’s the Matter with ‘Technology-Enhanced Learning’?” Learning, Media and Technology 40 (1): 5–20. doi:10.1080/17439884.2014.915851.

- Bearman, M., D. Boud, and R. Ajjawi. 2020. “New Directions for Assessment in a Digital World.” In Re-Imagining University Assessment in a Digital World, edited by M. Bearman, P. Dawson, R. Ajjawi, J. Tai, and D. Boud, 7–18. Switzerland: Springer.

- Bearman, M., P. Dawson, S. Bennett, M. Hall, E. Molloy, D. Boud, and G. Joughin. 2017. “How University Teachers Design Assessments: A Cross-Disciplinary Study.” Higher Education 74 (1): 49–64. doi:10.1007/s10734-016-0027-7.

- Bearman, M., P. Dawson, D. Boud, S. Bennett, M. Hall, and E. Molloy. 2016. “Support for Assessment Practice: Developing the Assessment Design Decisions Framework.” Teaching in Higher Education 21 (5): 545–556. doi:10.1080/13562517.2016.1160217.

- Bearman, M., P. Dawson, and J. Tai. 2020. “Digitally Mediated Assessment in Higher Education: Ethical and Social Impacts.” Re-Imagining University Assessment in a Digital World, edited by M. Bearman, P. Dawson, R. Ajjawi, J. Tai, and D. Boud, 23–36. Switzerland: Springer.

- Bearman, M., S. Lambert, and M. O’Donnell. 2021. “How a Centralised Approach to Learning Design Influences Students: A Mixed Methods Study.” Higher Education Research & Development 40 (4): 692–705. doi:10.1080/07294360.2020.1792849.

- Bearman, M., and R. Luckin. 2020. “Preparing University Assessment for a World with AI: Tasks for Human Intelligence.” In Re-Imagining University Assessment in a Digital World, edited by M. Bearman, P. Dawson, R. Ajjawi, J. Tai, and D. Boud, 49–63. Switzerland: Springer.

- Bennett, S., P. Dawson, M. Bearman, E. Molloy, and D. Boud. 2017. “How Technology Shapes Assessment Design: Findings from a Study of University Teachers.” British Journal of Educational Technology 48 (2): 672–682. doi:10.1111/bjet.12439.

- Bogost, I., and N. Montfort. 2007. “New Media as Material Constraint: An Introduction to Platform Studies.” Paper Presented at the Electronic Techtonics: Thinking at the Interface. Proceedings of the First International HASTAC Conference.

- Boud, D., and R. Soler. 2016. “Sustainable Assessment Revisited.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 41 (3): 400–413. doi:10.1080/02602938.2015.1018133.

- Bybee, R. W. 2009. The BSCS 5E Instructional Model and 21st Century Skills. Washington, DC: National Academies Board on Science Education.

- Carless, D., and D. Boud. 2018. “The Development of Student Feedback Literacy: Enabling Uptake of Feedback.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 43 (8): 1315–1325. doi:10.1080/02602938.2018.1463354.

- Dawson, P., and M. Bearman. 2020. “Concluding Comments: Reimagining University Assessment in a Digital World.” In Re-Imagining University Assessment in a Digital World, edited by M. Bearman, P. Dawson, R. Ajjawi, J. Tai, and D. Boud, 291–296. Switzerland: Springer.

- Goodyear, P., L. Carvalho, and P. Yeoman. 2021. “Activity-Centred Analysis and Design (ACAD): Core Purposes, Distinctive Qualities and Current Developments.” Educational Technology Research and Development : ETR & D 69 (2): 445–464. doi:10.1007/s11423-020-09926-7.

- Guàrdia, L., G. Crisp, and I. Alsina. 2017. “Trends and Challenges of e-Assessment to Enhance Student Learning in Higher Education.” In Innovative Practices for Higher Education Assessment and Measurement, edited by Elena Cano and Georgeta Ion, 36–56. IGI Global.

- Henderson, M., N. Selwyn, and R. Aston. 2017. “What Works and Why? Student Perceptions of ‘Useful’ Digital Technology in University Teaching and Learning.” Studies in Higher Education 42 (8): 1567–1579. doi:10.1080/03075079.2015.1007946.

- Hirsch, P., and K. Lloyd. 2005. “Real and Virtual Experiential Learning on the Mekong: Field Schools, e-Sims and Cultural Challenge.” Journal of Geography in Higher Education 29 (3): 321–337. doi:10.1080/03098260500290892.

- Jisc. 2007. “Effective Practices with e-Assessment." https://www.webarchive.org.uk/wayback/archive/20140613220103/http://www.jisc.ac.uk/media/documents/themes/elearning/effpraceassess.pdf.

- Kearsley, G. 1998. “Educational Technology: A Critique.” Educational Technology 38 (2): 47–51.

- Knox, J. 2017. “Data Power in Education: Exploring Critical Awareness with the “Learning Analytics Report Card.” Television & New Media 18 (8): 734–752. doi:10.1177/1527476417690029.

- Lea, M. R., and S. Jones. 2011. “Digital Literacies in Higher Education: Exploring Textual and Technological Practice.” Studies in Higher Education 36 (4): 377–393. doi:10.1080/03075071003664021.

- Littlejohn, A., H. Beetham, and L. McGill. 2012. “Learning at the Digital Frontier: A Review of Digital Literacies in Theory and Practice.” Journal of Computer Assisted Learning 28 (6): 547–556. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2729.2011.00474.x.

- Mahoney, P., S. Macfarlane, and R. Ajjawi. 2019. “A Qualitative Synthesis of Video Feedback in Higher Education.” Teaching in Higher Education 24 (2): 157–179. doi:10.1080/13562517.2018.1471457.

- Matthews, K. E., J. Tai, E. Enright, D. Carless, C. Rafferty, and N. Winstone. 2021. “Transgressing the Boundaries of ‘Students as Partners’ and ‘Feedback’discourse Communities to Advance Democratic Education.” Teaching in Higher Education : 1–15. doi:10.1080/13562517.2021.1903854.

- Mimirinis, M. 2019. “Qualitative Differences in Academics’ Conceptions of e-Assessment.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 44 (2): 233–248. doi:10.1080/02602938.2018.1493087.

- O’Donnell, M. 2020. “Assessment as and of Digital Practice: Building Productive Digital Literacies.” In Re-Imagining University Assessment in a Digital World, edited by M. Bearman, P. Dawson, R. Ajjawi, J. Tai, and D. Boud, 111–125. Switzerland: Springer.

- Pachler, N., H. Mellar, C. Daly, Y. Mor, D. Wiliam, and D. Laurillard. 2009. “Scoping a Vision for Formative e-Assessment: A Project Report for JISC.” http://www.jisc.ac.uk/media/documents/projects/scopingfinalreport.pdf

- Pangrazio, L., and J. Sefton-Green. 2021. “Digital Rights, Digital Citizenship and Digital Literacy: What’s the Difference?” Journal of New Approaches in Educational Research 10 (1): 15–27. doi:10.7821/naer.2021.1.616.

- Pangrazio, L., and N. Selwyn. 2019. “Personal Data Literacies’: A Critical Literacies Approach to Enhancing Understandings of Personal Digital Data.” New Media & Society 21 (2): 419–437. doi:10.1177/1461444818799523.

- Pardo, A., J. Jovanovic, S. Dawson, D. Gašević, and N. Mirriahi. 2019. “Using Learning Analytics to Scale the Provision of Personalised Feedback.” British Journal of Educational Technology 50 (1): 128–138. doi:10.1111/bjet.12592.

- Puentedura, R. 2009. "As We May Teach: Educational Technology from Theory into Practice." Accessed 15 December 2021. http://www.hippasus.com/rrpweblog/archives/2014/08/22/BuildingTransformation_AnIntroductionToSAMR.pdf.

- Raffaghelli, J. E., and B. Stewart. 2020. “Centering Complexity in ‘Educators’ Data Literacy’ to Support Future Practices in Faculty Development: A Systematic Review of the Literature.” Teaching in Higher Education 25 (4): 435–455. doi:10.1080/13562517.2019.1696301.

- Reyna, J., J. Hanham, and P. C. Meier. 2018. “A Framework for Digital Media Literacies for Teaching and Learning in Higher Education.” E-Learning and Digital Media 15 (4): 176–190. doi:10.1177/2042753018784952.

- Scott, M., and J. Unsworth. 2018. “Matching Final Assessment to Employability: Developing a Digital Viva as an End of Programme Assessment.” Higher Education Pedagogies 3 (1): 373–384. doi:10.1080/23752696.2018.1510294.

- Selwyn, N. 2010. “Looking beyond Learning: Notes towards the Critical Study of Educational Technology.” Journal of Computer Assisted Learning 26 (1): 65–73. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2729.2009.00338.x.

- Selwyn, N. 2014. Digital Technology and the Contemporary University: Degrees of Digitization. London: Routledge.

- Shibani, A., S. Knight, and S. Buckingham Shum. 2020. “Educator Perspectives on Learning Analytics in Classroom Practice.” The Internet and Higher Education 46: 100730. doi:10.1016/j.iheduc.2020.100730.

- Slade, C., G. Lawrie, N. Taptamat, E. Browne, K. Sheppard, and K. E. Matthews. 2021. “Insights into How Academics Reframed Their Assessment during a Pandemic: Disciplinary Variation and Assessment as Afterthought.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education : 1–18. doi:10.1080/02602938.2021.1933379.

- Smith, C. D., K. Worsfold, L. Davies, R. Fisher, and R. McPhail. 2013. “Assessment Literacy and Student Learning: The Case for Explicitly Developing Students ‘Assessment Literacy.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 38 (1): 44–60. doi:10.1080/02602938.2011.598636.

- Spante, M., S. S. Hashemi, M. Lundin, and A. Algers. 2018. “Digital Competence and Digital Literacy in Higher Education Research: Systematic Review of Concept Use.” Cogent Education 5 (1) 1519143. doi:10.1080/2331186X.2018.:.

- Stephenson, J. 1998. “The Concept of Capability and Its Importance in Higher Education.” In Capability and Quality in Higher Education, edited by John Stephenson and Mantz Yorke, 1–13. London: Kogan Page.

- Tai, J., R. Ajjawi, D. Boud, P. Dawson, and E. Panadero. 2018. “Developing Evaluative Judgement: Enabling Students to Make Decisions about the Quality of Work.” Higher Education 76 (3): 467–481. doi:10.1007/s10734-017-0220-3.

- Voogt, J., and N. P. Roblin. 2012. “A Comparative Analysis of International Frameworks for 21st Century Competences: Implications for National Curriculum Policies.” Journal of Curriculum Studies 44 (3): 299–321. doi:10.1080/00220272.2012.668938.

- Wickens, C. M., and T. Miller. 2020. “Gender, Digital Literacies, and Higher Education.” In The Wiley Handbook of Gender Equity in Higher Education, edited by Nancy S. Niemi and Marcus B. Weaver-Hightower, 53–67. Chichester: Wiley Blackwell.

- Williamson, B., S. Bayne, and S. Shay. 2020. “The Datafication of Teaching in Higher Education: Critical Issues and Perspectives.” Teaching in Higher Education 25 (4): 351–365. doi:10.1080/13562517.2020.1748811.

- Winstone, N. 2019. “Facilitating Students’ Use of Feedback: Capturing and Tracking Impact Using Digital Tools.” In The Impact of Feedback in Higher Education, edited by M. Henderson, R. Ajjawi, D. Boud, and E. Molloy, 225–242. Switzerland: Palgrave-Macmillan.

- Woldeab, D., and T. Brothen. 2019. “21st Century Assessment: Online Proctoring, Test Anxiety, and Student Performance.” International Journal of E-Learning & Distance Education/Revue Internationale du e-Learning et la Formation à Distance 34 (1) . http://www.ijede.ca/index.php/jde/article/view/1106.

- Wood, J. 2021. “A Dialogic Technology-Mediated Model of Feedback Uptake and Literacy.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 46 (8): 1173–1190. doi:10.1080/02602938.2020.1852174.