Abstract

Assessment and feedback are common sources of student dissatisfaction within higher education, and employers have shown dissatisfaction with graduates’ communication skills. Authentic assessment, containing ‘real-world’ context and student collaboration, provides a means to address both issues simultaneously. We discuss how we used authentic assessment within a biological sciences degree programme, replacing an individually written essay coursework assignment with learner-generated podcasts. We outline our implementation strategy in line with existing theory on learner-generated digital media, assessment for learning and self-regulated learning. Quantitative and qualitative analysis of survey data (2020 and 2021) indicate students prefer podcast assignments over traditional essay coursework, perceiving them to be more enjoyable, authentic, allowing for greater creativity, and better for building their confidence as communicators. Podcasting as an assessment may have a positive influence on knowledge retention and promote deep learning too. Our assessment design provides opportunities for community building, formative peer review and enhancing assessment literacy, while also being flexible enough to be used across any discipline of study and/or as an inter-disciplinary assessment.

Introduction

Student dissatisfaction with assessment is not new (Gibbs and Simpson Citation2004; Price et al. Citation2011). Price et al. (Citation2011) claim that part of the problem is too much focus devoted to the teaching of content with not enough forethought afforded to assessment and its constructive alignment with intended learning outcomes (ILOs) and learning methods (Biggs and Tang Citation2011). Within a particular unit or degree programme, ILOs should focus on both academic as well as transferable skills, e.g. communication. Good communication allows for accurate dissemination of information and aids effective teamwork; skills that professionals needed during the Covid-19 pandemic and that future graduates will require as humanity seeks to addresses various global challenges. Twenty-first century graduates need to combine elements of digital literacy with their academic training in research, critical ability and independent thought to accurately assess and evaluate the wealth of digital information available to them. While higher education institutions recognise communication and teamwork skills as important, the mode of communication (typically written essays and reports) and target audience (typically academic) are often lacking in variety and authenticity, particularly within science degrees. This may impact students’ career opportunities as many employers are ‘dissatisfied with the communication skills of many science graduates’ (Stevens, Mills, and Kuchel Citation2019, 1).

Authentic assessment, that which adds ‘real world value’ to the task, is a key feature of assessment for learning (AfL) (Sambell, McDowell, and Montgomery Citation2012). Fundamental elements of authentic assessment include an element of challenge, collaboration, metacognition, transfer of knowledge and some form of product or performance (Ashford-Rowe, Herrington, and Brown Citation2014). Such authenticity should not only enhance employability but also elevate student satisfaction and ‘promoting behaviour’ where ‘students talk positively about their subject of study to their peers’ (James and Casidy Citation2018, 402). Assessments that involve teams of students producing a digital media product align with these principles of authentic learning.

Podcasts are digitally edited content that are available online as (downloadable) audio files. Frequently they are available as episodes that follow a unique theme in a series and which users can subscribe to, but they can be standalone audio files too. Podcasts have been used in educational settings for more than a decade and approaches have been categorised as ‘substitutional/coursecasting’, ‘supplementary’, ‘integrated’ and ‘creative’ (Drew Citation2017). The first three approaches are teacher-generated and, while they hold educational value, they can result in a passive learning environment. In contrast, ‘creative podcasting’ promotes an active learning experience, as learners become constructors of knowledge (McGarr Citation2009). The Covid-19 pandemic resulted in an increase in teacher-generated digital media via online and blended teaching approaches, yet there is still a lack of research addressing the value of learner-generated digital media (LGDM), especially in STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) subjects (Reyna and Meier Citation2018a). Research suggests that creative podcasting allows students to more thoroughly comprehend course material, promote deeper learning and achieve higher grades (Lazzari Citation2009; Pegrum, Bartle, and Longnecker Citation2015). LGDM projects can also promote self-regulated learning (SRL) and foster 21st century skills needed by graduates (Stevens, Mills, and Kuchel Citation2019; Shrader and Louw Citation2021).

In this paper, we interlace three key components. First, we outline our pedagogic rationale for this assessment change. Second, we detail how we replaced individually written essays with learner-generated podcasts (LGPs) as an authentic assessment within an undergraduate unit. In doing so, we provide a working template for others to utilise, gain confidence from and build on. Finally, we present the results of a mixed methods study evaluating students’ experience of LGPs and teamwork across two years. We adopted an interpretivist approach to better understand the value of team-based LGPs for students, and to compare podcasts with traditional essays in various categories (enjoyment, creativity, communicator confidence, deeper learning, time required to complete, overall preference) from the student perspective. We chose these categories to align with topics of student (dis)satisfaction with assessment, assessment design and transferable skills. Additionally, we investigated students’ desire for additional teamwork opportunities and their preferences for team size and membership allocation.

Implementation

The design of our podcast intervention largely aligned with the LGDM framework proposed by Reyna, Meier, et al. (Citation2017) which considers eight stages needed for effective design and deployment of LGDM projects. This model also serves as a sensible scaffold for explaining the implementation of our podcast assessment. Years indicate year ending; i.e. ‘2020’ refers to the 2019–2020 academic year.

Pedagogy

This investigation involved biological sciences undergraduates studying a second-year optional unit entitled ‘Conservation Biology’, upon which 156 students enrolled in 2020 and 136 in 2021. Prior to 2019, the coursework component (40% of unit marks) consisted of an individually written essay on a topic chosen by the unit director. In 2019 we added ‘communicate conservation issues using digital media’ as a new unit ILO and changed the coursework to a LGP that would be produced in pairs. In addition, a formative assessment was included to provide students with the opportunity to practice making a podcast (including researching, scriptwriting, recording and editing) and to provide students with constructive feedback prior to their summative attempt. There were several pedagogical reasons for these changes: (i) to give students the opportunity to improve/hone their communication skills, as effective communication is arguably one of the most important, yet under-emphasised, elements in formal teaching of conservation biology (Bickford et al. Citation2012); (ii) to promote a deeper learning experience for students (Lazzari Citation2009; Pegrum, Bartle, and Longnecker Citation2015), including promotion of critical debate between students; (iii) to offer an additional opportunity for collaborative learning within their programme of study; (iv) to diversify the assessment landscape across the programme (written essays and laboratory reports dominate the associated degree programmes); and (v) to develop digital media training in-line with programme-level ILOs and desirable graduate attributes.

Refinements were made after the first iteration (2019) and here we present analysis of data from 2020 and 2021. In both years teaching was spread across six weeks; in 2020 this consisted of 15 × 50 minute in-person lectures and additional practical elements, in 2021 all in-person teaching was replaced with short online videos and synchronous online workshops due to Covid-19 restrictions. Teaching staff and core content remained the same between cohorts.

Student training

Students were introduced to podcasts via a three-hour practical session and an interactive e-handbook containing instructions on the podcast-making process (https://tinyurl.com/WakefieldPodcast). Students were then set a formative task of creating a five-minute podcast. We re-used the summative podcast title from 2019 as the formative title in 2020 and 2021 so that students had access to a range of marked exemplars on the same topic. In doing so, we hoped to boost self-efficacy and motivation for the following summative task via social modelling/vicarious experiences (Bandura Citation1977). Given the novelty of the task, inclusion of a formative assessment was essential for building assessment literacy. Furthermore, its inclusion is likely to have had a valuable role in fostering SRL (Andrade and Brookhart Citation2020), as well as providing an opportunity to practice key skills required for the summative podcast.

Teaching during the first practical mirrored the conceptual, functional and audio-visual components of the ‘digital media literacies framework’ (Reyna, Hanham, et al. Citation2017). Students were: (i) instructed to research relevant content, to think critically and to draft a script prior to recording (conceptual domain); (ii) given access to, and shown how to use, relevant features of various technological proxies (i.e. digital equipment) including audio recorders, mobile phones, laptops and Audacity® editing software (functional domain); (iii) prompted to consider audio levels, backing music/sound effects, copyright considerations and background noise (audio-visual domain). Students were directed towards popular environmental themed podcasts for examples of best practice but were free to choose the best format for presenting their podcasts. Students were provided with some creative freedom and encouraged to think critically about the most effective way to convey their topic, thus fostering a culture of SRL. Despite these freedoms, there were some technical constraints imposed upon students. Time limits were set for the duration of each podcast with more time allowed for the summative (eight minutes) than the formative (five minutes) podcast. Students were not allowed to conduct interviews with third parties and only students from each pair should be heard on their podcast. A mix of creative freedom and technical constraints has been successfully deployed with LGPs elsewhere (Lazzari Citation2009).

Having submitted their formative podcast, student pairs then attended a second, ‘review and feedback’, session during which they completed a partially filled marking rubric for use within a self and peer-assessment task. This activity was designed to make students active participants in the feedback process by gaining the perspective of the marker. By producing feedback in this way, rather than being mere recipients, we hoped students would evaluate their own efforts more thoroughly (Nicol, Thomson, and Breslin Citation2014). Orsmond, Merry, and Reiling (Citation2002) used a similar approach with pairs of students completing a poster assessment, reporting that exemplars improve students’ understanding of marking and feedback, foster higher quality outcomes, and that peer-assessment can promote greater objectivity compared to self-assessment.

Following the return of feedback students began work on a summative podcast. Summative titles varied between 2020 and 2021 and were chosen by staff to allow students to meet the appropriate ILOs which were: ‘explain why it is worth conserving biodiversity’; ‘explain and debate solutions for conserving biodiversity’; ‘recognise the inter-disciplinary nature of conservation biology’; and ‘communicate conservation issues using digital media’.

Hosting and distribution

Students submitted podcasts as team assignments within our virtual learning environment. Podcasts were uploaded as MP3 files with an accompanying PDF transcript; the latter was used for originality checking. Except for the exemplar podcasts from 2019, student podcasts were not distributed further.

Marking schemes

The formative-summative model for the assessment ensured parity between this unit and other optional units within our school, and the 40% weighting for the task is above the 20% minimum recommended for this type of assessment (Reyna et al. Citation2016; Reyna and Meier Citation2018b). The eight-minute duration was chosen to ensure student preparation and production time aligned with that required for written coursework being offered in other 10 credit point optional units on the programme. Our marking rubric was a modified version of our existing essay marking criteria, listing ‘content’, ‘argument and understanding’ and ‘presentation’ as major components. This approach had the triple benefit of being: (i) familiar to students; (ii) familiar to markers; and (iii) quick to implement.

Team contribution

Students were randomly assigned a partner for the formative task but required to choose a new partner for the summative task. Podcasts were marked as a team assignment with no mark or feedback discrimination between team members. Time was formally scheduled during practicals for partners to collaborate on their podcasts (both formative and summative), after which students were afforded the opportunity to hone their time management and teamwork skills themselves.

Feedback

Near the end of the ‘review and feedback’ practical, students received structured feedback (provided by trained postgraduate student demonstrators) on their formative podcast attempts. A numerical mark was not provided for the formative podcasts in the hope that students would focus their attention on the feedback and utilise this within the two-stage assessment setup (Gibbs and Simpson Citation2004). To promote SRL, students were instructed to collate their various feedback components and to discuss with their formative partner what they would do differently if asked to repeat the task together.

Student reflection

Students also reflected on their experiences via an end of unit evaluation survey. One additional question was added in 2021 to gauge students’ views on the amount of time required to complete a podcast relative to traditional essay assignments. The survey was voluntary to complete and comprised of both open and closed-answer questions. The survey had four sections: (1) questions asking students to compare podcasts and essays against various learner-centred attributes; (2) questions focused on teamwork; (3) an open question regarding the value of creative podcasting; and (4) more generic unit satisfaction questions relating to all of the teaching within the unit. Students completed the survey within one month of the end of the unit.

Evaluation

We used an interpretivist mixed methods approach (Mcchesney and Aldridge Citation2019) to understand students’ experiences of LGPs and teamwork. Responses from closed-answer questions were analysed quantitatively in R (RStudio, v.1.0.153) using Pearson chi-squared tests to investigate student opinions within cohorts, as well as between cohorts (2020 and 2021), using 0.5 expected distributions. Qualitative data were analysed using thematic analysis with a largely inductive and semantic approach (Braun and Clarke Citation2006, Citation2012). For trustworthiness, we: archived the data; kept reflective accounts of our thoughts as we conducted the thematic analysis; held several meetings involving researcher triangulation of the initial codes we independently assigned to student comments; and collectively vetted the subsequent themes (Nowell et al. Citation2017). Analysis was conducted using NVivo Pro 12 (QSR International) and Excel (Microsoft).

Results

Of the 292 students enrolled, 50% (N = 79/156) and 51% (N = 70/136) submitted an end of unit evaluation in 2020 and 2021 respectively. This is a slightly higher than average rate of response for surveys of this type (Porter and Umbach Citation2006). Data from both cohorts were combined in the following analyses, unless stated otherwise.

Quantitative analysis

Podcast assessments

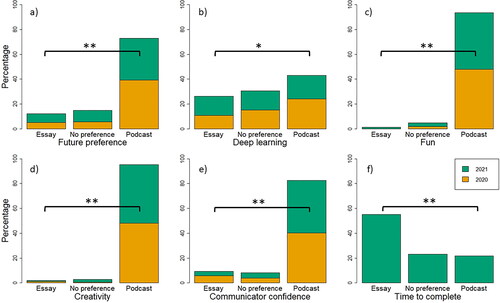

When asked to compare podcasts against traditional essays, students believed that podcasts allowed for greater: understanding of the content (Χ2(1, N = 102) = 6.63, p = 0.01); creativity (Χ2(1, N = 145) = 133.25, p < 0.01); and confidence as communicators (Χ2(1, N = 136) = 85.77, p < 0.01). They also reported that podcasts were more fun (Χ2(1, N = 139) = 131.12, p < 0.01) and took less time to work on than traditional essays (Χ2(1, N = 53) = 9.98, p < 0.01, [2021 data only]). When asked which assessment they would prefer in future, more students voted for podcasts than essays (Χ2(1, N = 127) = 65.21, p < 0.01) ().

Figure 1. Student views (years 2020 and 2021) on podcast relative to essay assessments. Percentage responding when asked which mode of assessment: (a) they would prefer in the future; (b) allowed for greater understanding of content; (c) was more fun; (d) afforded greater creativity; (e) gave them greater confidence as communicators; (f) took more time to complete (2021 cohort only). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

No association was found between cohort (2020 and 2021) and student assessment preference for any of the attributes: understanding of the content (Χ2(1, N = 102) = 2.06, p = 0.15); creativity (Χ2(1, N = 145) = 0.20, p = 0.65); confidence as a communicator (Χ2(1, N = 136) = 0.81, p = 0.37); fun (Χ2(1, N = 139) = 2.38, p = 0.12); and future assessment preference (Χ2(1, N = 127) = 0.97, p = 0.33).

Teamwork preference

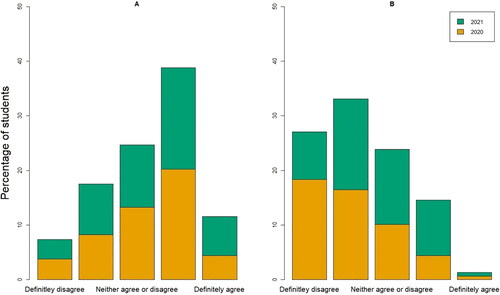

Most students were either in favour of, or ambivalent to, the prospect of more team assessment in the future, and opinion on this was similar between cohorts (). In contrast, when asked if they would like to work in larger groups (three or more members), there was a slight difference in opinion across years (). Pre-Covid (2020) 69% of students disagreed with this statement, whereas only 51% disagreed during the pandemic (2021).

Figure 2. Student views on groupwork before (2020, N = 79) and during (2021, N = 69) the Covid pandemic. (A) Student responses to the statement ‘I would like more group assessment in the future’. (B) Student responses to the statement ‘I would like to work in larger groups (three or more members)’. From left to right, columns are ‘Definitely disagree’, ‘Mostly disagree’, ‘Neither agree or disagree’, ‘Mostly agree’ and ‘Definitely agree’.

Qualitative analysis

Through thematic analysis, we identified seven main themes from the free text responses within the surveys. These were: skills development; random allocation of partner; choice of partner; emotional awareness; motivation; assessment literacy and feedback; and authentic assessment. We defined these themes using our coded student responses.

Skills development

Responses in this theme commonly referenced the skills gained/honed by creating a podcast, including research, critical ability, teamwork, time management, digital capabilities, resilience and leadership. Communication was discussed in terms of collaboration with partners, consideration of the podcast listener, as well as science communication more generally. For example, ‘[The assignment] allows for creativity, teamwork and development of communication skills’, and ‘Communication (not just the information in the podcast but also within your pair) … and portraying the information you’ve learnt in a way that’s accessible to a different type of audience compared to if you were writing an essay’.

Some students spoke of knowledge retention: ‘I am confident that because the assessment was interesting I can tell you more about [subject] than I could for many other assessments. Often you forget the research you have done quickly but telling it to an audience and to a partner does help you remember’. Others touched upon deep learning: ‘Making it accessible for a general audience was a good way to make the information more understandable. Reinstating the research definitely facilitated learning. I also got into quite deep discussions about the podcast subjects with my partners which furthered my understanding and helped me consider different viewpoints’.

Random allocation of a partner

Responses in this theme related to students’ opinions of being allocated a random partner to work with for the formative task. Some students highlighted it was a stressful experience, such as ‘Randomly assigned partners is not fair to some people who struggle with things like anxiety, as they find it hard to call, communicate with people they’ve never met and it would lead to them not being able to contribute equally’. Others felt it prevented a potentially difficult experience of finding a partner themselves, such as ‘It was also difficult choosing my own partner because I have now spent the majority of my degree virtually, it can be embarrassing being asked to choose a partner when you haven’t had the time to develop the friendships with your peers’.

Others were happy to have been given the opportunity to meet new friends within the cohort, such as: ‘I’m pretty socially awkward … I wouldn’t have thought I’d enjoy the podcast a lot. But being paired first with a random girl and then pairing with a friend I didn’t know too well was a lot of fun! … I made friends I never normally would have’.

Some were happy to work outside of their existing friendships: ‘I think it’s nice to hear about other person’s perspective on the assignment and topic and mix that with your own, you might learn something new from your partner’ and ‘I liked being randomly assigned a partner and would’ve preferred the summative one be partner assigned as well as there was an obligation to work with friends when they’re not necessarily the best partners’.

Choice of partner

Many students liked being randomly assigned a partner for the formative podcast so long as they could choose their partner for the summative assessment. Many students believed that working with existing friends would be more productive, less stressful, lead to a higher mark for the assignment, or some combination of these ideas. For instance, ‘I think for the formative task having worked with an assigned partner was nice and gave an opportunity for me to mix with peers I may not have before however I think it’s good we chose our partners for the summarise task since you know them so you’re more likely to have a cohesive piece of work that’s not awkward or at risk of the other person bringing your mark down’ and ‘the stress of being paired with someone you do not work well with really harms your mental health’.

Emotional awareness

There were numerous comments relating to emotional awareness. Responses included recognition of one’s own emotions (including comfort zones, confidence, stress, anxiety and enjoyment) as well as recognition of others’ emotions (e.g. partner or audience). Some found teamwork stressful, e.g. ‘Having my grade depend partially on someone else is very stressful, especially when we have different opinions on how best to complete the assignment’. However, most found the podcast assessment ‘fun’, engaging, and refreshing, e.g. ‘The summative podcast where I could work with a friend creatively and have fun exploring [topic] was one of my highlights of the course so far’. Many cited a sense of pride in their achievements, e.g. ‘Creating the podcast was so fun as we got to work with people we never would have otherwise, it felt so much more satisfying and I was really proud of what we produced’. Others commented on enhanced confidence following the task, for example, ‘It definitely allowed more creativity to complete, was much more enjoyable than writing an essay, and built my confidence in communicating effectively’, and ‘[podcasting] still requires high levels of competency and belief in oneself which I think this assignment helped me improve’.

Motivation

Responses in the motivation theme were largely positive and referred to both self and team-motivation, as well as social drivers of this. We noted comments relating to ‘focus’ (or lack of) on a particular task as well as comments conveying excitement for the next task or future learning such as: ‘feeling confident to create your own project and deliver your own "product" The feeling is so satisfying. I will create my own podcast’; ‘I also found that I was much more motivated to work on it than I have been with reports and essays’; and ‘Podcasts are different and are more fun so makes me more motivated to do research on the topic. But would not want them all the time, a mixture is good’.

Assessment literacy and feedback

This included students reflecting on the benefits and limitations of different assessment approaches, with others commenting on the ambiguity of the assessment instructions and/or marking criteria. Some students highlighted issues of student parity, workload, and the ability to demonstrate learning for the marker, such as ‘it would be good to get more guidance on how to gain top marks in this as it’s a little unclear, e.g. I have heard from some people that fake interviews are a good idea but the plagiarism aspects of this is a bit confusing’. This theme also included comments relating to feedback, self-evaluation and students’ suggestions for improvement: ‘Only thing I would say to improve the format would be to give us more freedom on the topic, understand that makes marking harder but maybe a choice of like three questions would be a happy compromise’.

Authentic assessment

Responses included a handful of students recognising that certain elements of the assessment, including randomised teamwork and communication skills, would be directly relevant to professional life/future practice (including within their degree programme), such as ‘in some ways it is a more realistic situation to have to collaborate with someone whom you do not know and thus it pushes you further out of your comfort zone; perhaps it even brings another side out of you’. Similarly, ‘Podcasts allow students to be more creative in the process. Also allows us to feel more confident with our presentation skills and to talk about conservation topics in a conversation. It’s also more fun than an essay and could be useful for our careers’.

Discussion

Combining quantitative and qualitative data, our results indicate an overwhelming preference for podcasts over traditional essay coursework that remained consistent between pre- and post-Covid-19 student cohorts. Perceived enjoyment, creativity and confidence as communicators were the most salient factors, but our data suggest that knowledge retention and deep learning could be enhanced via creative podcasting too. Student feedback shows that, with minimal alteration of unit ILOs, teaching activities and assessment guidelines, it is possible to assess the same core academic skills of students while providing a fun, creative and authentic mode of assessment that students deem appropriate and manageable. Furthermore, our students reported spending less time on podcast assignments than traditional essays, although we imagine this might be an artefact of students enjoying the podcast task.

Our use of LGPs required students to become self-regulated learners and to hone transferable skills they will need as graduates, and many students commented on this authenticity in our surveys. Furthermore, student responses indicate that our pedagogic motives (to improve communication skills, to promote deep learning and critical debate, to provide opportunities for collaborative learning, to improve digital media training, and to diversify the assessment landscape) have been met. While most students said they would prefer a podcast over an essay assignment in the future, qualitative results illustrate that a mix of assessment types is preferable. Indeed, the novelty factor associated with this assessment task is likely to have contributed to students’ positive reflections.

Teamwork

The assessment involved students working in pairs. Students thought this worked best when they were randomly allocated a partner for a formative task but given a choice of partner for the summative task. Almost half of the students expressed a desire for more teamwork in their degree programme but only 16% wanted to work in teams of three or more in the future. Qualitative and quantitative results indicate that students studying online during Covid-19 (2021) showed more of a desire for teamwork than their predecessors, perhaps owing to their remote learning experiences at the time. Our results show that offering students a novel team assessment with an element of randomised team membership can be a good way to remove students from their comfort zone and to allow them to feel more connected with their degree programmes.

Team membership proved an interesting topic and one that provided a link between many of the other themes. For example, students discussed how working in a pair allowed for development of teamwork and communication skills, but also how it afforded them a more holistic view of the subject. They showed emotional awareness when reflecting on having to work with a random partner yet could also recognise how this was an authentic experience and drove their motivation.

As well as fostering academic and transferable skills, we hoped the introduction of teamwork would scaffold for SRL, community building and peer-learning. Students’ sense of anonymity within large cohorts is not new (Mulryan-Kyne Citation2010), but when coupled with a higher proportion of online and blended learning there is a risk that students could miss important opportunities for collaboration and for developing social skills. Our results show that LGPs can provide a scaffold for these skills while delivering an assessment that is considered enjoyable, both by students taught within a traditional lecture-based format and those taught with a blended approach (years 2020 and 2021 in this study respectively). While increased cohort sizes can be squeezed into lecture theatres or taught online at no extra time cost, ‘the trick when designing assessment regimes is to generate engagement with learning tasks without generating piles of marking’ (Gibbs and Simpson Citation2004, 8). A by-product of team assessment is a reduction in marking, and/or the ability to introduce a formative assessment at no net marking cost.

In 2019, we randomised team membership for both formative and summative tasks, but this strategy was not as well received by students. Some felt that their partner’s efforts hampered their ability to score well on the summative assessment. A blend of randomly-allocated and student-allocated teams promotes cohort building, social skills and authentic activities, coupled with high student satisfaction. More frequent use of randomised teamwork in the first year of study could aid community building and provide the necessary social contacts for instances where students need to self-allocate into teams later in their degrees. Thorough integration of teamwork within degree programmes would give students greater opportunity to build learning networks in which peer-assisted learning can flourish.

LGDM, motivation and satisfaction

We conclude that existing LGDM frameworks (Reyna, Hanham, et al. Citation2017; Reyna, Meier, et al. Citation2017) were helpful aids for effective assessment design and delivery but debate one aspect. Reyna and Meier (Citation2018b) state that uploading students’ work to open platforms (e.g. YouTube) is a ‘vital feature’ of LGDM projects as audience awareness is important for motivating students to complete LGDM tasks and students will be more motivated if they know their work will be seen by more than an audience of one (the marker). While we agree that this is a good idea, our data suggests that it is not vital, as despite no a priori motivation that their work would be accessible for others, many of our students reported motivation due to enjoyment with the task. In some cases, students were motivated because they did not want to let their partner down, in other cases because they needed to compensate for a partner’s lacking effort. The product of a team project is inherently visible to all other members of the team with no extra hosting effort to staff, and this provides a source of motivation despite the product not being as widely visible.

Nevertheless, sharing digital media products with a wider audience can ‘foster discussion and consideration of ideas’ (Reyna, Meier, et al. Citation2017, 2), and Shrader and Louw (Citation2021) put this into practice by incorporating an element of peer-review at the end of their LGDM project. In contrast, we included a peer-review element mid-way through the unit, such that students could modify their strategies prior to the summative assignment. The combination of a formative assignment followed by a self and peer-assessment task where students can adopt the role of the marker affords students training without fear of failure and allows for ‘discussion and consideration of ideas’ before the summative assignment. We believe this workflow can help improve student self-efficacy for the summative task via both mastery and vicarious experiences (Bandura Citation1977). As our students had fun, it is likely that their confidence will have been boosted via positive emotional states at the time they received feedback on their formative efforts. Feedback from partners, other teams, friends and family, were all possible between formative and summative assignments and could boost self-efficacy further via both social persuasion as well as emotional states.

Limitations and next steps

Our finding that students perceive podcasts as better than essays for deep learning should be interpreted with caution as we did not measure this directly, and students’ perceptions of learning do not necessarily correlate with actual learning (Persky, Lee, and Schlesselman Citation2020). It is also important to note that most student survey responses were collected prior to the return of marks and feedback on the summative podcast; thus, it would be interesting to see if/how student reflection changed in light of their marks.

Gibbs and Simpson (Citation2004, 3) assert that assessment should be designed to focus on ‘worthwhile learning’ first, then reliability later. Currently in its fifth iteration, this assessment has overcome initial hiccups and is now running smoothly, yet we continue to adjust based on student feedback and our own confidence as academics to introduce new elements. The year following this study we implemented our students’ suggestions for a longer duration and a greater choice of title topics such that the summative podcast is now 10 minutes long with three titles for students to choose from. Anecdotally, our students have reflected positively to such choice, just as they have within other LGDM projects (Shrader and Louw Citation2021). Additionally, we now inform students that the best podcasts in each topic will be made publicly available on the departmental website (with student permission). While theory predicts such hosting and distribution of student products can be a motivating factor for student engagement, we believe it could also be motivating for future learners in the form of engaging material for outreach, widening participation and open days.

LGPs involve discussion and debate and expose students to new perspectives. This can, and should, be taken further through implementation of interdisciplinary team assignments, where students consider different perspectives on a topic. We think that LGDM projects related to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals would provide a topical base for students from various disciplines to convene and to widen perspectives (students’ and audiences’ alike) on pressing global issues. For instance, one could imagine students studying biology, geography and politics working together to produce a podcast on the topic of nature-based solutions to climate change. Perhaps students enrolled in psychology could collaborate with business and marketing students to discuss solutions to food/fashion/plastic waste. These ideas resonate with McArthur’s (Citation2022) perspective that authentic assessment should enable students to be positive transformers of society rather than simply mirroring the world of work in its current state. We suspect that this type of assessment design would not only be authentic and fun but transformative and fulfilling.

Conclusion

We encourage others to consider including more authentic and team-based assessments. Podcasts offer an excellent starting point as they are less complicated than other forms of LGDM while allowing for a range of academic and transferable skills to be gained by learners. The ability to work in a team and to communicate orally in a clear and concise manner are important skills for scientists but hold similar importance within many other academic disciplines and career sectors. The ‘formative—review and reflect—summative’ structure of our assessment and the combination of randomised and student-chosen teams promotes SRL and peer-learning, and could be developed further to enhance community building and student confidence.

Acknowledgements

Good ethical principles were adhered to throughout the collection of the student views, including voluntary participation, right to withdraw and informed consent to collect the data for use in future publication. The University of Bristol Faculty of Life Sciences and Science Research Ethics Committee concluded that a formal research ethics review was not required for this education evaluation.

Disclosure statement

There is no conflict of interest concerning this project.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Andy Wakefield

Andy Wakefield is a Senior Lecturer in the School of Biological Sciences at the University of Bristol. He is a Fellow of the Higher Education Academy and the Technology-Enhanced Lead for the School. His research interests involve innovative approaches to teaching and learning, authentic assessment, and sustainability.

Rebecca Pike

Rebecca Pike is a Lecturer in the School of Biological Sciences at the University of Bristol. She is a Fellow of the Higher Education Academy and the Assessment & Feedback Lead for the School. Her research interests lie in curriculum development and innovative approaches to assessment and feedback, particularly with regards to assessment literacy, to improve the student experience.

Sheila Amici-Dargan

Sheila Amici-Dargan is an Associate Professor in the School of Biological Sciences at the University of Bristol. She is a Senior Fellow of the Higher Education Academy and a trustee of the Society for Experimental Biology. Her research interests include assessment and feedback practices in Higher Education and empowering students to engage in curriculum co-development.

References

- Andrade, H. L., and S. M. Brookhart. 2020. “Classroom Assessment as the Co-Regulation of Learning.” Assessment in Education; Principles, Policy & Practice 27 (4): 350–372. doi:10.1080/0969594X.2019.1571992

- Ashford-Rowe, K., J. Herrington, and C. Brown. 2014. “Establishing the Critical Elements That Determine Authentic Assessment.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 39 (2): 205–222. doi:10.1080/02602938.2013.819566

- Bandura, A. 1977. “Self-Efficacy: Toward a Unifying Theory of Behavioral Change.” Psychological Review 84 (2): 191–215. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191

- Bickford, D., M. R. C. Posa, L. Qie, A. Campos-Arceiz, and E. P. Kudavidanage. 2012. “Science Communication for Biodiversity Conservation.” Biological Conservation 151 (1): 74–76. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2011.12.016

- Biggs, J., and C. Tang. 2011. Teaching for Quality Learning at University. 4th ed. New York: Society for Research into Higher Education & Open University Press.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2012. “Thematic Analysis.” In APA Handbook of Research Methods in Psychology, Vol 2: Research designs: Quantitative, qualitative, neuropsychological, and biological, Chap. 4. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. doi:10.1037/13620-004

- Drew, C. 2017. “Edutaining Audio: An Exploration of Education Podcast Design Possibilities.” Educational Media International 54 (1): 48–62. doi:10.1080/09523987.2017.1324360

- Gibbs, G., and C. Simpson. 2004. “Conditions under Which Assessment Supports Students’ Learning.” Learning and Teaching in Higher Education 1 (1): 3–31.

- James, L. T., and R. Casidy. 2018. “Authentic Assessment in Business Education: Its Effects on Student Satisfaction and Promoting Behaviour.” Studies in Higher Education 43 (3): 401–415. doi:10.1080/03075079.2016.1165659

- Lazzari, M. 2009. “Creative Use of Podcasting in Higher Education and Its Effect on Competitive Agency.” Computers & Education 52 (1): 27–34. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2008.06.002

- McArthur, J. 2022. “Rethinking Authentic Assessment: Work, Well-Being, and Society.” Higher Education. Advance online publication. doi:10.1007/s10734-022-00822-y

- Mcchesney, K., and J. Aldridge. 2019. “Weaving an Interpretivist Stance throughout Mixed Methods Research.” International Journal of Research & Method in Education 42 (3): 225–238. doi:10.1080/1743727X.2019.1590811

- McGarr, O. 2009. “A Review of Podcasting in Higher Education: Its Influence on the Traditional Lecture.” Australasian Journal of Educational Technology 25 (3): 309–321. doi:10.14742/ajet.1136

- Mulryan-Kyne, C. 2010. “Teaching Large Classes at College and University Level: Challenges and Opportunities.” Teaching in Higher Education 15 (2): 175–185. doi:10.1080/13562511003620001

- Nicol, D., A. Thomson, and C. Breslin. 2014. “Rethinking Feedback Practices in Higher Education: A Peer Review Perspective.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 39 (1): 102–122. doi:10.1080/02602938.2013.795518

- Nowell, L. S., J. M. Norris, D. E. White, and N. J. Moules. 2017. “Thematic Analysis: Striving to Meet the Trustworthiness Criteria.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 16 (1): 160940691773384–160940691773313. doi:10.1177/1609406917733847

- Orsmond, P., S. Merry, and K. Reiling. 2002. “The Use of Exemplars and Formative Feedback When Using Student Derived Marking Criteria in Peer and Self-Assessment.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 27 (4): 309–323. doi:10.1080/0260293022000001337

- Pegrum, M., E. Bartle, and N. Longnecker. 2015. “Can Creative Podcasting Promote Deep Learning? The Use of Podcasting for Learning Content in an Undergraduate Science Unit.” British Journal of Educational Technology 46 (1): 142–152. doi:10.1111/bjet.12133

- Persky, A. M., E. Lee, and L. S. Schlesselman. 2020. “Perception of Learning versus Performance as Outcome Measures of Educational Research.” American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education 84 (7): ajpe7782. doi:10.5688/AJPE7782

- Porter, S. R., and P. D. Umbach. 2006. “Student Survey Response Rates across Institutions: Why Do They Vary?” Research in Higher Education 47 (2): 229–247. doi:10.1007/s11162-005-8887-1

- Price, M., J. Carroll, B. O’Donovan, and C. Rust. 2011. “If I Was Going There I Wouldn’t Start from Here: A Critical Commentary on Current Assessment Practice.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 36 (4): 479–492. doi:10.1080/02602930903512883

- Reyna, J., J. Hanham, and P. Meier. 2017. “A Taxonomy of Digital Media Types for Learner-Generated Digital Media Assignments.” E-Learning and Digital Media 14 (6): 309–322. doi:10.1177/2042753017752973

- Reyna, J., and P. Meier. 2018a. “Learner-Generated Digital Media (LGDM) as an Assessment Tool in Tertiary Science Education: A Review of Literature.” IAFOR Journal of Education 6 (3): 93–109. doi:10.22492/ije.6.3.06

- Reyna, J., and P. Meier. 2018b. “Using the Learner-Generated Digital Media (LGDM) Framework in Tertiary Science Education: A Pilot Study.” Education Sciences 8 (3): 106. doi:10.3390/educsci8030106

- Reyna, J., P. Meier, F. Geronimo, and K. Rodgers. 2016. “Implementing Digital Media Presentations as Assessment Tools for Pharmacology Students.” American Journal of Educational Research 4 (14): 983–991. doi:10.12691/EDUCATION-4-14-1

- Reyna, J., P. Meier, J. Hanham, P. Vlachopoulos, and K. Rodgers. 2017. “Learner-Generated Digital Media (LGDM) Framework.” INTED2017 Proceedings, 8777–8781. doi:10.21125/inted.2017.2080

- Sambell, K., L. McDowell, and C. Montgomery. 2012. Assessment for Learning in Higher Education. 1st ed. Abingdon: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780203818268

- Shrader, A. M., and I. Louw. 2021. “Using a Social Media Project as a Way to Get Students to Communicate Conservation Messages to the General Public.” Journal of Biological Education. doi:10.1080/00219266.2021.1924231

- Stevens, S., R. Mills, and L. Kuchel. 2019. “Teaching Communication in General Science Degrees: Highly Valued but Missing the Mark.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 44 (8): 1163–1176. doi:10.1080/02602938.2019.1578861