Abstract

In higher education, there is a tension between teachers providing comments to students about their work and students developing agency in producing that work. Most proposals to address this tension assume a dialogic conception of feedback where students take more agency in eliciting and responding to others’ advice, recently framed as developing their feedback literacy. This conception does not however acknowledge the feedback agency students exercise implicitly during learning, through interactions with resources (e.g. textbooks, videos). This study therefore adopted a different framing - that all feedback is internally generated by students through comparing their work against different sources of reference information, human and material; and that agency is increased when these comparisons are made explicit. Students produced a literature review, compared it against information in two published reviews, and wrote their own self-feedback comments. The small sample size enabled detailed analysis of these comments and of students’ experiences in producing them. Results show students can generate significant self-feedback by making resource comparisons, that this feedback can replace or complement teacher feedback, be activated when required and help students fine-tune feedback requests to teachers. This widely applicable methodology strengthens students’ natural capacity for agency and makes dialogic feedback more effective.

Introduction

Researchers have identified self-regulation as a learning goal for students in university and feedback processes as critical to its development (Butler and Winne Citation1995; Nicol and Macfarlane-Dick Citation2006; Allal Citation2016; Panadero, Lipnevich, and Broadbent Citation2019). Yet there is a tension between students developing as self-regulating learners and teachers telling them how to improve their work through the provision of feedback, as written comments or through dialogue (Nicol and Macfarlane-Dick Citation2006; Boud and Molloy Citation2013). According to research, the way to address this tension, here referred to as the feedback agency tension, is for students to take a more active and agentic role in eliciting, processing and acting on feedback information from others, usually teachers but also peers (Nicol Citation2010; Carless et al. Citation2011; Van der Kleij, Adie, and Cumming Citation2019). This has recently been framed as developing students’ feedback literacy (Carless and Boud Citation2018; Molloy, Boud, and Henderson Citation2020).

Despite the central role that dialogue plays in feedback processes, reframing students’ as active agents in their dialogue with teachers and others is too narrow a framing to address the agency tension. Dialogue here refers to both written and verbal interactions with students about their work. From a practice perspective, power and knowledge differences between teachers and students will always impede attempts to shift agency in dialogue to students (Steen-Utheim and Wittek Citation2017). However, the main limitation of the dialogic perspective is conceptual rather than practical. This conception does not acknowledge the feedback agency which students exercise naturally and informally, for example, when they use information in a textbook to update an assignment they are working on (Nicol Citation2019, Citation2021; Jensen, Bearman, and Boud Citation2023). This is part of a wider concern in feedback research, that the context within which dialogue operates is not sufficiently acknowledged (Gravett Citation2022; Tai et al. Citation2023). Against this background, we devised an intervention that did not rely on dialogue as the primary locus for addressing the agency tension.

This intervention drew on Nicol’s inner feedback model (2019, 2021). Students produced some work, compared it against information in some material resources (in this case, information in journal articles) and wrote their own self-feedback comments before receiving any comments from their instructor. The hypothesis was that if students could author high-quality feedback comments on their own work, this would constitute robust evidence of their exercise of feedback agency. This was evaluated by a detailed examination of the nature of the comments that students produced, with complementary data also collected about how this approach influenced students’ perceptions of agency. The results provide compelling reasons to rethink current approaches to shifting feedback agency to students.

Literature review

Feedback literacy

Building on Sutton (Citation2012), Carless and Boud (Citation2018) define feedback literacy as ‘the understandings, capacities and dispositions needed to make sense of information and use it to enhance work or learning strategies’ (1315). They identify four inter-related capabilities and dispositions that students need for effective uptake of feedback: appreciating feedback; making judgements; managing affect; and taking action. This framework has been further developed by Molloy, Boud, and Henderson (Citation2020). The main addition is that students producing feedback for peers is also identified as a component of feedback literacy.

Although feedback literacy is a relatively new concept, many approaches to developing student agency have been proposed based on this framing (Molloy, Boud, and Henderson Citation2020; Wood Citation2021; Malecka, Boud, et al. Citation2022; de Kleijn Citation2023), with some implemented (Little et al. Citation2023). The latter include designing learning opportunities and preparing students so that they proactively elicit, process and respond to feedback information from teachers and others, rather than passively waiting to receive it (Hill and West Citation2020; O’Connor and McCurtin Citation2021; Malecka, Ajjawi, et al. Citation2022; Hui et al. Citation2023), developing students’ capacity to make evaluative judgements through planned activities such as self-assessment, peer review and/or analysis of exemplars (Hoo, Deneen, and Boud Citation2022; Tam Citation2021).

Most proposals and interventions to develop feedback literacy are founded on socio-constructivist principles where feedback is conceived as a dialogue between teachers and students and student peers. This is evident in the language used in feedback literacy research, for example, that students need to develop proactive recipience for feedback (Winstone, Mathlin, and Nash Citation2019), that they co-construct feedback meanings with their teachers (Heron et al. Citation2023) or that we need to support students’ uptake of feedback (Wood Citation2022). While Carless and Boud (Citation2018) do use the word information in their definition of feedback literacy, in their writing they primarily identify information as comments, as do Molloy, Boud, and Henderson (Citation2020) in their update of the literacy framework. Also, a core pillar of that framework is managing affect which is about students managing ‘defensive responses to feedback, particularly when comments are critical, or grades are low’ (Carless and Boud Citation2018, 1317). Even activities such as self-assessment, peer review and analysis of exemplars have an underlying aim to support student agency in dialogue and in uptake of feedback from others. Indeed, dialogue is often integral to these interventions (Han and Xu Citation2020; Hoo, Deneen, and Boud Citation2022). For example, Smyth and Carless (Citation2021) contend that analysis of exemplars will be more effective if teachers facilitate a discussion of them with students.

The centrality of dialogue is also signified in the recently developed instrument to measure students’ feedback literacy (Dawson et al. Citation2023). This instrument, which focuses on what students do in feedback processes, has 24 items. Sixteen mention the word comments (e.g. I check whether my work is better after I have acted on comments) and six imply comments (e.g. other people provide an input about my work, and I listen or read thoughtfully). While we do not dispute that human dialogue is central to feedback processes, and indeed to all learning, the argument here is that the dialogic conception on its own is problematic as a framing for feedback literacy and to address the feedback agency tension. There are pragmatic concerns but more importantly significant conceptual issues.

Problems with a sole focus on feedback as dialogue

Practical concerns

When feedback is conceptualised as a dialogue between teachers and students any attempt to address the agency tension is in danger of being compromised. First, the uneven power relationship will impede some students from taking more responsibility, especially lower-ability students (Orsmond and Merry Citation2013) and those from cultures ‘where strict hierarchies and great power distance’ are the norm (Rovagnati, Pitt, and Winstone Citation2022, 351). Second, as this concept involves teachers making judgements about students’ work, some students might come to rely on these judgements, rather than make their own. Even if teachers are sensitive in the way they handle dialogue, or dialogue is used to facilitate student self-assessment, peer review or exemplar-based activities, there is still the risk that students will follow the teacher’s insights rather than make the effort to independently form their own. Also, given that students require different levels of support and different support at different stages during learning, teachers will need considerable sensitivity and adaptability to meet individual students’ needs and to fade out support as student’s agency increases (Malcolm Citation2023). Similar issues arise with peer dialogue, but also different agency issues such as students not believing their peers have the capacity to make judgements or that it is desirable for them to do so (Kaufman and Schunn Citation2011).

Conceptual limitations

A more important issue is that the dialogic conception on its own is too narrow a framing of feedback processes. It does not acknowledge the feedback agency that students are already exercising implicitly and naturally in everyday life and during study (Nicol Citation2019, Citation2021; Jensen, Bearman, and Boud Citation2023).

Nicol (Citation2021), drawing on earlier research by Butler and Winne (Citation1995) and by others on student self-regulation (Nicol and Macfarlane-Dick Citation2006; Allal Citation2016; Yan and Brown Citation2017), maintains that conceiving feedback only as a communicative exchange results in an artificial separation of planned and formal feedback processes from natural and implicit feedback processes (see also, Jensen, Bearman, and Boud Citation2023). Students, like all of us, are exercising feedback agency and generating feedback all the time, even when there are no comments from or dialogue with others. Nicol (Citation2022) refers to this as inner feedback and provides the following definition:

the new knowledge that students generate when they compare their current knowledge against some reference information, guided by their goals. (1)

From a related perspective, there is now a growing body of research that challenges the dialogic conception underpinning feedback literacy on the grounds that it fails to take account of the context within which dialogue operates. Gravett (Citation2022), for example, notes that in feedback literacy research feedback is usually portrayed as a ‘binary dialogic event between individuals’, rather than as an event situated in a social and material context (271). Context here is broad and includes the technology used, power, space, time, institutional structures and procedures as well as resources such as journal articles, diagrams and video recordings. Taking this wider view, agency does not reside in individuals, neither students nor teachers: rather, it is enmeshed within complex social and material arrangements (Tai et al. Citation2023). Although this socio-material framing helps us better understand feedback dialogue, its complexity - that everything interacts with everything else - makes it difficult for teachers to identify practice ideas they could easily implement to increase students’ agency, and that would impact in the short rather than long term. So, how might we address the feedback agency tension without overly relying on dialogic processes alone?

Addressing the feedback agency tension

In this study, we investigated feedback agency using the model of inner feedback proposed by Nicol (Citation2021, Citation2022). A key concept in that model is comparison, seen as the core mechanism by which students generate inner feedback (i.e. ideas for improvement). To learn from teacher comments, even if provided during a dialogue, students must compare them, or more accurately their interpretation of them, against their work and generate inner feedback out of that comparison. However, as alluded to, students implicitly use other information for comparison and for feedback generation besides comments. As they are producing academic work (e.g. writing a report, solving a problem) they will compare their developing work against their goals and against different sources of information that will help them reach those goals. That information might be generated internally (e.g. from memories of past performance) or derived externally from resources (e.g. textbooks, videos, rubrics) or from observations of people or events (e.g. chemical reaction in the laboratory). In this study, the comparison information was in published journal articles.

Given that most feedback comparisons happen naturally and implicitly and are thus below conscious awareness, the most important principle in Nicol’s model (2021, 2022) is that to capitalise on their pedagogical power teachers must plan for them. This translates into the following implementation sequence which can be repeated cyclically across a task or course. Students do/produce some work, then compare what they have produced against some information in a resource (or resources) and make explicit/tangible the output of those comparisons, as written self-feedback comments and/or through discussion and/or in actions for improvement. In this investigation students were required to write their own feedback comments.

This perspective on feedback is neither purely cognitive nor socio-constructivist. Rather it is situated, as it acknowledges that what feedback meanings learners construct depends on their interactions with people and resources in the learning environment and beyond. In other words, resources and people serve as co-regulating influences on students’ self-regulatory processes (Allal Citation2020). Hence this conceptualisation also offers a practical way to begin to address concerns of socio-materialist researchers. Resources can be viewed as the proximal material context for dialogic feedback interactions (and vice versa). Information in disciplinary resources is already the subject matter of most feedback dialogue, but surprisingly is not usually harnessed deliberately by teachers as a specific driver to support student feedback agency. Yet, resources are one of the easiest contextual factors to bring into play, as recent research shows.

Research on feedback comparisons

In a study by Nicol and McCallum (Citation2022), first-year students compared a 500-word essay they had written against two peer essays plus a high-quality exemplar essay. After each comparison they wrote what they learned as self-feedback comments. These comments not only matched the comments the teacher would have provided but went beyond them, in level of detail, number of action points and through inclusion of comments not given by the teacher (e.g. on alternative ways of structuring the essay). Berg and Moon (Citation2022) had chemistry students compare their analysis of gold extraction against three different teacher-constructed exemplar analyses. Again, students generated significant self-feedback and improved their understanding of gold extraction without receiving teacher comments.

Lipnevich et al. (Citation2014) had psychology students produce a draft research report, then different groups were given a rubric and/or three exemplar reports to help them update their draft report. All groups improved their grades from draft to redraft with the rubric-alone group showing most improvement. This shows not only that students can generate their own feedback from resources of different kinds, but also that this method can reduce teacher workload. In a follow-up study, secondary school students wrote an essay, and then updated it using either teacher comments or annotated exemplars, or both (Tomazin, Lipnevich, and Lopera-Oquendo Citation2023). All students made equal grade improvements from draft to redraft, evidencing that teacher comments are not necessarily the better comparator. Sambell and Graham (Citation2020) showed that to benefit from inner feedback processes, students had to deliberately compare the exemplars against their own work. It was not enough just to provide exemplars.

The current study

Research focus

While the studies above show that resource comparison have potential to address the feedback agency tension, none of them provide any detail regarding the self-feedback that students generate from making comparisons. One provides quantitative data on how students’ self-feedback comments compare with teacher comments, others provide evidence of learning gains after making comparisons, and one provides a mix of data including students’ perceptions of their learning from comparisons. The comparators in each study differed (i.e. exemplars, rubrics, comments, peer works) and student feedback agency was not their prime focus.

Given this research gap, this study had two inter-related objectives:

to gain more insight into what self-feedback comments students generate when they compare their work against information in resources;

to determine whether writing such self-feedback helps alleviate the feedback agency tension.

To achieve these objectives, we examined both the self-feedback comments students produced through the lens of feedback agency (self-feedback data) and the effects of writing feedback comments on students’ perceptions of agency (perception data). Importantly, students wrote their self-feedback before receiving any feedback comments from an educator. Hence, this research, where students author their own feedback comments, provides both a distinctive and robust test of their feedback agency.

Context of implementation

The context of this study was the writing of a thesis literature review by final-year undergraduate economics students. Thesis writing is a complex task that is usually new to undergraduate students. Hence, supervisors invariably provide detailed comments on student’s writing, and many follow up with one-to-one feedback dialogue. At this level of study, students are also expected to take significant responsibility for their learning. The tension between supervisor feedback and students exhibiting agency in their thesis production is widely discussed in research on supervision; and like the research cited earlier, recommendations to address this tension invariably focus on how supervisor-student dialogue is enacted (Greenbank and Penketh Citation2009; Roberts and Seaman Citation2018; Malcolm Citation2023). Hence this constitutes an ideal context to investigate the feedback agency tension.

Methods

Student sample

Given the aim was to collate detailed data on students’ self-feedback comments, an in-depth exploratory investigation with a small number of students was appropriate (Sleker Citation2005). The participants were three students attending a UK university who were writing their dissertation thesis in economics. These students are identified by the pseudonyms Alex, Blake and Cameron or by the pronoun ‘her’. For ethical reasons it is not possible to provide more detail other than that they differed in nationality, gender, in the type of research they were engaged in (quantitative or qualitative), and in the quality of the draft review they produced before the comparison activities. All were aged between 18-25 and one was a joint honours student studying Economics and English literature. Ethical approval was provided by the University College of Social Sciences Ethics Committee for Non-Clinical Research Involving Human Subjects [reference number 400170120]. Students provided written consent to use their data anonymously.

Resources for comparison

Before the intervention reported here each student had already written a draft literature review. The resources for the comparison activities were two published literature reviews drawn from top quality economics journals. These two literature reviews differed from each other and from each student’s own review in economics subject content, as the intention was that students generate feedback on the writing process (argument, structure, use of evidence). This differs from most prior research where students compare their written work against peer works or exemplar works on the same subject topic (e.g. Nicol and McCallum Citation2022). We use the term ‘resources’ rather than exemplars in this study, as it is the information in resources that students compare their work against, and because resources can differ in subject content and in presentation format with reference to the students’ own work. An electronic proforma was created with prompts to collect data from the comparison activities (see supplemental materials).

The intervention

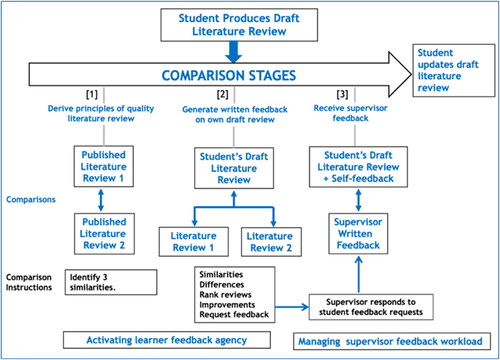

Students engaged in two different comparison activities in sequence then formulated feedback requests for the supervisor. The latter, comparing what they know versus what they would like to know, can also be seen as a comparison activity ().

Comparing two published literature reviews

In the first comparison, students compared the two published literature reviews against each other and wrote down what they learned as self-feedback comments. Specifically, students were prompted to identify three similarities across the two reviews that would warrant calling them high quality and to provide a written rationale for each (see online supplemental materials). This was intended to encourage students to generate an internal standard of good quality writing. Prior research shows that when students compare two similar entities that differ in subject content but are similar at the deep structural level, they invariably see beyond the surface features of these entities and identify and extract the common concepts, principles and structures that they share (Gentner and Maravilla Citation2017). This supports transfer of knowledge to new contexts.

As the first comparison was sequenced after students had produced their own draft literature review, we anticipated students would not only generate comments about what makes a quality review but would also spontaneously generate internal feedback about their own literature review, as occurred in Nicol, Thomson, and Breslin (Citation2014).

Comparing published reviews against own literature review

In the second comparison, students compared each published literature review, one after the other, against their own draft review and wrote self-feedback comments. They were also asked to rank all three literature reviews, to give a reason for their ranking decision and to write what improvements they would make to their own work. The externalisation of inner feedback in writing is critical at both comparison stages as are the instructional prompts as these also mediate students’ feedback productions (Nicol Citation2022).

Requests for supervisor feedback

The last prompt during the second comparison asked students to write feedback requests for the supervisor. This encouraged them to identify what feedback they thought they still required and/or perceived themselves as unable to generate. These requests were conceived as a bridge linking resource-generated feedback to supervisor provision of feedback. For research purposes, the supervisor wrote her initial feedback before she saw the students’ written feedback. She then added further feedback and addressed students’ feedback requests. Students thus made both comparisons and wrote their requests before receiving supervisor comments.

Data collection

Two sets of data were collected in this study: students’ written self-feedback comments and their perceptions of the feedback comparison approach. Ranking with explanations, stating what improvements students would make to their literature review and writing feedback requests all constitute self-feedback data. Perception data was collected using a questionnaire which students completed after all comparison activities (see supplemental materials). The authors also met students as a group to discuss their experiences and to enable them to elaborate on their questionnaire responses. Both the questionnaire and focus group provided data on the perceived value of different comparison activities and about the relative value of generating self-feedback comments versus receiving supervisor comments.

Data analysis

A qualitative interpretivist methodological approach was appropriate to this research (Denzin Citation2001). The students’ self-feedback comments were interpreted in relation to the notion of student feedback agency (as per the inner feedback model) with a specific focus on how resource comparisons help students exercise feedback agency. Demonstrating the practical value of the implementation sequence as a way of addressing the feedback agency tension was the prime focus, hence the small number of students and the detailed data on their self-feedback comments (Sleker Citation2005). The thematic analysis of the questionnaire and focus group data was mostly deductive in relation to ideas of feedback agency and the inner feedback model. Neither in the questionnaire nor focus group did we ask questions using the word agency or its equivalent. Both authors coded the data separately in relation to agency themes. There were no differences of any substance in their thematic coding.

Results

Given the extent of written feedback comments students generated, we present a more elaborate account of Alex’s data with that from Blake and Cameron used to enrich the analysis, mainly through highlighting similarities and differences. While each student’s self-feedback data is presented separately, the perception data for all three students is collated and presented in a separate section.

Alex’s self-feedback comments

Comparing two external literature reviews

All students were able to identify key principles that constitute a good quality literature review by comparing two published reviews. shows what Alex generated.

Table 1. Alex: feedback generated from comparing two external literature reviews.

These principles are consistent with the main advice, in articles and guidance documents, on how to produce a good literature review (Maier Citation2013; Hart Citation2018). Common recommendations are that writer(s): (i) make the scope of their review clear at the outset; (ii) discuss major issues and debates around the research topic; (iii) only use external literature insofar as it is directly relevant to their own research; (iv) identify gaps in the extant literature (e.g. theoretical, methodological, empirical) and show how their own research addresses those gaps and adds to the literature.

Comparing published reviews with own literature review

shows what feedback Alex produced when asked to compare two external literature reviews against her own draft review. Note that in response to the first question in , Alex benchmarks her own review back to the principles of quality that she identified through her prior comparison. From this she identifies a range of weaknesses in her own literature review, ‘it did not… compare and contrast’, ‘I made no references to my own methodology’, ‘I brought up evidence but not as succinctly’. These typify the comments a supervisor might provide but Alex generates them herself, by exercising her own feedback agency.

Table 2. Alex: feedback generated from comparing published reviews against own review.

Ranking and improvements

When asked to rank all three reviews Alex provides a coherent rationale for what makes literature review 2 better than 1, with both considered better than her own. For Alex, ranking activates feedback on the relative quality of her literature review against these high-quality external reviews. As such, it anchors Alex’s self-feedback to quality standards, which is what supervisors try to do with comments. When asked what she would do to improve her own literature review, Alex wrote: ‘I would rewrite it almost completely’. She then explains why. It is notable that this explanation also draws on her earlier comparison of the two published reviews as well as the ranking.

Self-generated feedback in relation to supervisor feedback

The supervisor provided eight comments on the writing and five on the subject content of Alex’s literature review. As expected, Alex provided no content feedback. All supervisor comments focused on how Alex had used the prior literature and research to position her own research:

You have picked up some interesting and related papers… However… missing in this review is that it is not always clear how these are related to your paper. Or even, how your paper contributes to the big picture. What you present here is a good first step… There should be next steps to refine this presentation by linking your own work in terms of similarities and differences… You can create sub sections and discuss literature in relation to those.

I feel as though I have a clear idea of how I want my review to look after examining these pieces… although, I would appreciate feedback on specific issues. Is the first paragraph of my review better suited somewhere else? Does a literature review require a general introduction to the market being studied?

Action on feedback

All students had the opportunity to update their draft literature review after the feedback intervention. In her final submission, Alex successfully highlighted the centrality of her own work in connection to the wider literature producing a much higher quality literature review, based on the feedback she generated through resource comparisons, which was endorsed and reinforced by the supervisor comments.

Blake’s self-generated feedback

Comparing two external literature reviews

Blake derived similar principles to Alex from comparing the two published reviews. However, what distinguished her comparative analysis is that her approach reflected her status as a joint-honours student studying Economics and English Literature. This was evident in her use of the term discourse markers which is a phrase, often used at the beginning of a sentence, that plays a role in managing the flow and structure of a piece of writing:

Both [reviews]… begin and continue to use clear discourse markers, to signal the manner in which their piece relates to previous contributions to the field… both include statements… such as "this paper extends the approach…” "This study is related to several studies that have looked at… “and “To further highlight the differences”.

Comparing published reviews with own literature review

Blake also identifies differences (i.e. weaknesses) in her literature review with reference to the qualities she identified in the published reviews. For example:

Considering the extent to which I clarify what this thesis hopes to contribute to the field the amount of explanation I extend about the dissertation’s USP… [unique selling point] is unclear… it should be as clear as that of Lit. 2, who repeatedly clarify and contrast and outline their USPs.

Table 3. Examples of supervisor’s responses to Blake’s feedback requests.

Ranking and improvements

Blake, like Alex, also ranks literature review 2 as best and her own as least good. She clearly identifies weaknesses in her own review ‘Features too many political and legislative facts for context purposes of which the relevance is not explicit’. Blake’s ranking also reflects her language studies background, for example, ‘Lit 2 shows the best linguistic dexterity’. Her ideas for improvement also refer back to the principles she derived from her earlier comparison of the two published reviews:

I aim to better explain how it is that my approach differs from that of the contributors I am mentioning, with tightly interwoven, shorter more succinct sentences.

Self-generated feedback in relation to supervisor feedback

For Blake, there were seven supervisor comments on her writing and none on content. Similar to Alex, the feedback that Blake generated overlapped significantly with the supervisor’s feedback comments. However, Blake had five feedback requests, more than the others. Hence the supervisor added significantly to the comments she had already provided to address these requests. shows two examples of supervisor comments in relation to Alex’s requests. Feedback requests have been advocated in the feedback literacy literature (e.g. de Kleijn Citation2023). Yet, this investigation shows that anchoring such requests in prior resource comparisons would increase their power, as students will have invested effort in creating a more elaborate knowledge and prior feedback platform from which to formulate them (e.g. first request).

Action on feedback

Blake’s draft literature review submission lacked structure and focus. She made significant improvements in the final version with better engagement with the wider literature and deeper connections with her own work, showing that she was able to implement her own feedback insights.

Cameron’s self-generated feedback

Comparing two external literature reviews

Cameron identified similar principles of a good literature review to Alex and Blake. However, she provided significantly more detail. From the first comparison, she produced 3093 words in contrast to 187 and 256 from Alex and Blake respectively. Most of this detail comprised elaborate examples, with citations drawn from the two published literature reviews, explaining how the writer had implemented the principle. The following shows the pattern:

These two literature reviews show the state of current studies in relation to the research questions. For example, review 1 shows three contemporaneous works which are related to its research. First… Gopinath (2006) studied the importance of shock in the trend in emerging countries… Second, Yue (2006) found the effect of the bargaining power of the lender and borrower on… Lastly, Cuadra and Sapriza (2006) discovered…

Comparing published reviews with own literature review

Cameron maintains that she had already implemented the principles she extracted from the first comparison in her own draft review. She provides considerable detail to prove this claim using extensive examples from her own review. The following, again, shows the pattern of her response:

My literature review represents a detailed outline as well as aims. For example, section 2 explains the outline that the research paper will explain the structure of the UK housing market and goes on to state its aim to analyse how the determinants impact house prices. In addition [my]… research paper shows the state of current knowledge in relation to a research question. In section 2.2, for example…

Ranking and improvements

Cameron ranks her own review as better than the two published reviews. She justifies this by identifying weaknesses and critiquing the other reviews. She backs her claims with evidence. Whether Cameron’s ranking is accurate is not the issue here. Her work was of high-quality, and she saw her literature review as written for a dissertation rather than for publication: so that was the basis of her ranking. What is important to note is the depth and extent of self-feedback that ranking generates when one of the items ranked is the students’ own work.

Even though she saw her own work as of high quality, Cameron still identifies improvements she would make to her draft review from the comparison activities:

To improve my literature review additional relevant studies to fully support criticisms raised [could be included]… For example, the review can include… Furthermore, the review can present more findings such as…

Student-generated feedback in relation to teacher feedback

The supervisor only provided three comments on the writing process in Cameron’s draft review, and one was an affirmation of the quality of Alex’s writing (‘you have indicated how these studies relate to yours’). This acknowledges that Cameron’s work was of high quality and that significant improvements were not needed, at least from the supervisor’s perspective.

Nonetheless, Cameron still believed that she would benefit from supervisor feedback, yet her request does not specify what feedback she would like.

At this stage, I think I would benefit most from some feedback provided by a professional researcher for evaluation of my work and any recommendation on how to improve my research and writing skills for the future.

This request is understandable as we all value human feedback, especially reader response feedback on our writing, as this differs in its merits and limitations from resource generated feedback. Hence, the argument in this article is not that we replace human feedback with resource-based feedback. Rather it is that we use both in productive ways so one supports the other. Staging resource comparisons before dialogic comparisons is one simple way of achieving this.

Action on feedback

Cameron produced a very-high quality draft literature review. Nonetheless, she still made significant improvements in her final submission. This shows that even students who have produced high quality work can be challenged by resource comparisons to further improve the standard of that work.

Student’s perceptions of the value of the different comparison processes

The data from the questionnaire and focus group provide further evidence, alongside students’ self- feedback comments, that making resource comparisons before receiving teacher comments increases students’ own feedback agency.

Comparing two external literature reviews

All students reported that comparing the two literature reviews helped them grasp what constitutes a good quality review. However, while acknowledging that making such comparisons was a natural process they might engage in implicitly, for example by consulting journal articles and handbooks they reported that the requirement to make the output explicit in writing promoted deeper thinking:

you are making all these comparisons in your head, but when you are actually forced to write it down you realise how much more you have to think about it. [Alex]

It is better to have something first then you’re aware of how you could apply what you find from the comparison and improve your own. [Blake]

Had there only been a single piece of work, the consistency between good literature reviews would not have been obvious… comparing two ideal examples helps cement what I might otherwise have skipped… if you’ve got two you say, this is the standard, if you had more… you would get lost. [Alex]

Comparing the published reviews with their own draft review

When asked about their experiences from explicitly comparing the two literature reviews against their own, students responded that this was:

the most helpful exercise – it helps build criticism for my own work and understand what went wrong/right. The real benefit in the comparisons was comparing the consistency between the two literature reviews against mine, seeing what both the authors had done that I had not. [Alex]

I had always made implicit comparison with other work but having a structured framework, with which to work through, made the process more efficient and helped tease out better comparisons. [Alex]

Writing the results… has helped me organise the important points… also helped me reflect upon them thoroughly and make reference to them in the future so that I could apply the lessons to improve. [Cameron]

Added value of resource comparisons over supervisor feedback

When asked what the comparison process adds to their feedback over and above the feedback a supervisor provides, students’ responses centred on their agency, and on a reduction in their dependency on the supervisor. Indeed, Alex provides a compelling case for including this explicit comparison methodology from the first year of university:

The comparison process… because it takes more personal effort to generate… holds a lot of weight. Had I started this self-generated feedback process earlier in my university career, I would be a lot more proficient at it and think I would require less supervisor feedback as I would have the confidence to build my own feedback system.

I feel empowered to ask more incisive questions, because I am more confident that I understand the basic tenets… having to ask basic questions, means I feel like I’m asking too many questions…[this] skews my perception of how well I am working independently. This [making comparisons] …has so much value, I have always needed feedback, but this drills down, it really is retained differently in my head.

The comparison process was an internal learning procedure which I believe needs to precede in order to benefit fully from the supervisor’s feedback… This has helped me structure my review… before I could further improve the draft based on the supervisor’s feedback.

you get [supervisor] feedback but it is slow… with this method you are not waiting for supervisor feedback. Generating your own feedback is lot quicker and you can use it for anything. [Alex]

Importantly, students maintained that generating their own feedback before requesting feedback enabled them to identify how the supervisor could best help them.

Supervisor feedback is the fine tuning which is as it should be as they have a set of specific skills that… if you can figure something out by yourself then why not do it that way and then what is left over… and then it can be refined by someone who really knows what they are doing. [Alex]

What supervisors provide that making comparisons does not

Making comparisons against resources does not however diminish the importance of external feedback advice from a teacher. Indeed, all students gave reasons why they valued supervisor comments:

I think that it’s an important yardstick… I do still want faculty reassurance. [Blake]

The feedback from the supervisor… was really helpful because I couldn’t identify those errors myself, even after having read my dissertation [thesis] many times. [Cameron]

Supervisor feedback tends to cut to the core of issues more concisely… also provides guidance and reassurance… and a more trusted source… to trust my own self-feedback as well. [Alex]

Taking responsibility for own comparisons

Students confirmed that their experience with the comparison method would influence what they would do in future:

This experience has taught me that both comparing different studies and making comparisons with my own work are helpful in improving my project. For the future I… will definitely be using this method. [Alex]

Discussion

Students as the generators of feedback

Overall, the results of this investigation show that students are able to generate high-quality self-feedback comments by making resource comparisons, with minimal supervisor prompting. This feedback not only mirrored the comments their supervisor subsequently provided, but it was also more detailed and individualised. Students successfully utilised this self-feedback to improve their work. These findings constitute compelling evidence of student feedback agency. The perception data add to this evidence by showing that students experience generating their own feedback as empowering, as reducing their reliance on supervisor comments. Students also believed they could use this comparison method to generate feedback immediately and at any time without waiting for supervisor feedback, with one student having already done so. Further, they reported that after generating their own feedback using resources, they were better able to formulate feedback requests for their supervisor.

Practical considerations

Nature of the comparison information

In this study, students only generated feedback on the writing process and not the subject content. This might suggest there are limits to students’ ability to exercise feedback agency. However, the focus on writing was deliberate. The published reviews were on a different topic from each other and from the students’ own, and the instructional prompts directed students towards the writing quality. If supervisors wished students to generate content feedback, they could instead provide literature reviews on the same topic as the student’s own and formulate appropriate prompts. However, such comparators might lead to concerns about copying of subject content (Handley and Williams Citation2011). Hence other comparators might be used such as a video of experts discussing different positions relevant to an aspect of the literature review content. This focus on different format comparators, in this case text against a video, is unexplored territory in feedback research.

Explicitness: students writing their own feedback comments

A distinctive feature of this study was the methodology of having students render visible their own internal feedback processes as written self-feedback comments. Students reported this was critical as were the instructional prompts, as it encouraged them to think more deeply about the feedback they generated and to organise feedback points for future reference. Explicitness is a key principle in the inner feedback model. Nicol (Citation2021) maintains it has value, both for students and the teacher. For students it raises their metacognitive awareness of their own feedback capability. For teachers, it provides better diagnostic information on students’ learning. There are however other ways of making inner feedback tangible, for example, through peer discussion (Nicol and Selvaretnam Citation2022) or through improvements in work (Lipnevich et al. Citation2014), also deployed in this study. Nonetheless, there is special value in students authoring their own feedback comments, given that writing is a powerful learning activity in its own right (Klein and van Dijk Citation2019).

Role of instructional prompts

In this study, prompts were used to give focus to each comparison activity (i.e. identifying similarities, differences, ranking, requesting feedback and suggesting improvements). Based on this, readers might infer that prompting and providing feedback comments are similar in their effects on student agency. However, this is not how students perceived prompts, nor does it acknowledge that unlike comments, prompts are not judgements by others of students’ work: rather, they facilitate students to make their own judgements. This is important, as a prime cause of the feedback agency tension is students’ feelings of being judged. This is why models of feedback literacy emphasise that students learn to manage affect (Carless and Boud Citation2018; Molloy, Boud, and Henderson Citation2020). While feedback processes will always evoke some emotional response, it is notable that no student here reported discomfort or negative reactions from making resource comparisons. The perception data did however highlight an affective dimension, that supervisors, at times, reassure students about the value of their own feedback judgements.

Comparison sequence: before and after comparisons

This investigation differed from prior research (e.g. Nicol and McCallum Citation2022) in its two-stage comparison sequence. A question raised by this sequence concerns the timing of the first comparison. If the aim is to maximise student feedback agency, should it come before rather than after students produce their draft literature review? If before, students could use the results to generate better feedback while producing their work, rather than waiting until the redrafting stage. Research shows learning benefits when students compare similar entities before they produce their own work (Gentner and Maravilla Citation2017). However, if implemented, a different question is raised: What comparisons to enact after students produce the draft literature review so they can make further improvements? There are several possibilities. The same comparators could be used but with different instructional prompts, for example, that direct students to areas still weak in their work. Another possibility is that students compare their work against information in other resources and even those in a different format, for example, a flow-chart of the structures of some quality literature reviews. Again, this points to prospects for future research.

Workload implications for educators

Had this been solely a practice implementation rather than a research investigation, supervisor commenting workload might have been reduced, as she could have based her feedback not just on students’ draft literature review submission, but also on their written self-feedback comments. In other words, the supervisor could limit her comments to only those that students were not able to self-generate. Feedback requests also help supervisors tailor their comments to students’ individual needs, which makes their commenting more efficient. In effect, students’ self-feedback comments could either supplement supervisor comments or replace them, depending on the situation. However, whether supervisor workload is reduced or not will depend on the burden involved in reading students’ self-feedback, responding to their feedback requests and on whether this method will change the way educators enact feedback processes more generally. Hence studies investigating this will also prove valuable.

Theory and practice

Integrating resource comparisons and supervisor comment comparisons

While this investigation shows that students can write their own feedback comments, it is not an argument against supervisor-student feedback dialogue. Indeed, even though students reported this method increased their agency all expressed a need for and value in supervisor comments; for example, to help them identify weaknesses or gaps in their work they might not identify themselves. This aligns with the inner feedback model, that each comparison type, in this case dialogic and resources, have different merits and limitations, and that teachers create an appropriate mix.

The main recommendation here is to sequence feedback comparisons so that supervisor feedback comments come after students have generated their own feedback through resource comparisons. It is much easier to activate student feedback agency by harnessing resources than through modifications in students’ dialogic interactions with supervisors alone. Just as important is the finding that feedback requests after resource comparisons also increases students’ agency during dialogue with their supervisor. Feedback requests serve as a bridge, built by students out of resource-based comparisons, that productively links them to subsequent dialogic comparisons. This bridge can be strengthened further by having students engage in peer dialogue comparisons, after resource comparisons, with groups, instead of individuals, formulating feedback requests for the teacher. Indeed, resource comparisons and peer comparisons can be planned in iterative cycles across a series of learning activities or a course (Nicol and Selvaretnam Citation2022). The key, however, to increasing student feedback agency is always to end-load teacher comments, after other comparison activities.

Research methods and future studies

Generalisability of the findings or of the model

The small number of participants will for some raise issues about the generalisability of the findings to other student cohorts, disciplines and contexts. In response, it should be noted that this was not the intention of the study. The inner feedback model predicts that students will generate different self-feedback depending on individual differences and context. This was evidenced by the nature of the self-feedback the joint-honours student generated relative to others, and by the considerable detail that Cameron produced to the same instructional prompts. Nor was the purpose to prove that students could generate productive self-feedback. There is already evidence for this, direct and indirect. Rather, the purpose was to evaluate a methodology to increase students feedback agency by having them write their own feedback comments. It is this methodology, we argue, that can be generalised to other contexts. The main contribution of this article is in providing a relatively straightforward method of increasing students’ feedback agency - by sequencing resource comparisons before dialogic comparisons with feedback requests acting as the bridge between the two – that could easily be applied in other disciplines and contexts.

Future research

The scope is wide as this way of thinking about feedback is not commonplace in research or practice. Some questions related to student agency, for example might centre on:

the disciplinary nature of comparators (e.g., medicine versus sociology versus STEM subjects),

the relative effects on students’ agency of before and after comparisons and their combination,

the merits of using comparators of a different format to the students’ work (e.g., comparing textual information against information in diagrams),

instructional prompts and their varying effects in promoting agency,

further extending students agency by having them select comparators and/or formulate prompts for each other.

the effects of this methodology on teacher and student workload.

Research methodology

In thinking about future research, the methodology of students making tangible their own internal feedback as self-feedback comments will be important. This methodology not only has pedagogical value, but also research value in the data it provides. Data of this kind is essential if we are to scope the effects of different comparisons and prompts in different teaching and disciplinary contexts. A starting point would be to use this methodology to better understand what feedback students generate from teacher comments, as this is far from clear, despite its importance to feedback literacy research. For example, if collected, this would enable researchers to better understand the extent to which teacher comments help or hinder students’ agency development.

Conclusion

How to increase student agency in feedback processes is a pivotal issue permeating feedback research. Yet most models of feedback frame this issue in terms of students taking more agency in their dialogic interactions with instructors and with peers. This framing limits the potential of feedback for learning as it does not capitalise on the natural feedback processes that students engage in implicitly and incidentally when they compare their work against information in external resources (Nicol Citation2021). It also does not acknowledge that disciplinary resources are the immediate and intermingled context for dialogic feedback processes (Gravett Citation2022). Much more progress could be made in addressing the feedback tension by bringing into play comparisons against information in resources as a formal feedback method alongside dialogical comparisons. Overall, this research adds to the case for reconceptualising feedback as an inner process that relies, inter-alia, on different kinds of external information to fuel it (Nicol Citation2021). Another reason to embrace this conception is that it more accurately captures the common sense meaning of the word ‘information’ as used in the now widely cited definition of feedback literacy ‘the understandings, capacities and dispositions needed to make sense of information and use it to enhance work or learning strategies’ (Carless and Boud Citation2018, 1315).

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (120.1 KB)Acknowledgements

Thanks to Bas Trimbos of the Department of Curriculum and Instruction in the Netherlands, Jenni Rose from Manchester Alliance Business School and John McCormick of Brandeis University, Massachusetts, USA for their helpful feedback on this article. Thanks also to the Economics students who participated in this investigation and shared their time, insights and enthusiasm.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Allal, L. 2016. “The Co-Regulation of Student Learning in an Assessment for Learning Culture.” In Assessment for Learning: Meeting the Challenge of Implementation, edited by D. Laveault and L. Allal. Switzerland: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-39211-0_15.

- Allal, L. 2020. “Assessment and the co-Regulation of Learning in the Classroom.” Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice 27 (4): 332–349. doi:10.1080/0969594X.2019.1609411.

- Berg, S. A., and S. Moon. 2022. “Prompting Hypothetical Social Comparisons to Support Chemistry Students’ Data Analysis and Interpretations.” Chemistry Education Research and Practice 23 (1): 124–136. doi:10.1039/D1RP00213A.

- Boud, D., and E. Molloy. 2013. “Rethinking Models of Feedback for Learning: The Challenge of Design.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 38 (6): 698–712. doi:10.1080/02602938.2012.691462.

- Butler, D. L., and P. H. Winne. 1995. “Feedback and Self-Regulated Learning: A Theoretical Synthesis.” Review of Educational Research 65 (3): 245–281. doi:10.3102/00346543065003245.

- Carless, D., and D. Boud. 2018. “The Development of Student Feedback Literacy: Enabling Uptake of Feedback.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 43 (8): 1315–1325. doi:10.1080/02602938.2018.1463354.

- Carless, D., D. Salter, M. Yang, and J. Lam. 2011. “Developing Sustainable Feedback Practices.” Studies in Higher Education 36 (4): 395–407. doi:10.1080/03075071003642449.

- Dawson, P., Zi Yan, A. Lipnevich, J. Tai, D. Boud, and P. Mahoney. 2023. “Measuring What Learners Do in Feedback: The Feedback Literacy Behaviour Scale.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education. doi:10.1080/02602938.2023.2240983.

- de Kleijn, R. A. M. 2023. “Supporting Student and Teacher Feedback Literacy: An Instructional Model for Student Feedback Processes.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 48 (2): 186–200. doi:10.1080/02602938.2021.1967283.

- Denzin, N. K. 2001. Interpretive Interactionism. 2nd ed. SAGE

- Gentner, D., and F. Maravilla. 2017. “Analogical Reasoning.” In International Handbook of Thinking and Reasoning, edited by L. J. Ball and V. A. Thomson, 186–203. New York, NY: Psychology Press.

- Gravett, K. 2022. “Feedback Literacies as Sociomaterial Practice.” Critical Studies in Education 63 (2): 261–274. doi:10.1080/17508487.2020.1747099.

- Greenbank, P., and C. Penketh. 2009. “Student Autonomy and Reflections on Researching and Writing the Undergraduate Dissertation.” Journal of Further and Higher Education 33 (4): 463–472. doi:10.1080/03098770903272537.

- Han, Y., and Y. Xu. 2020. “The Development of Student Feedback Literacy: The Influences of Teacher Feedback on Peer Feedback.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 45 (5): 680–696. doi:10.1080/02602938.2019.1689545.

- Handley, K., and L. Williams. 2011. “From Copying to Learning: Using Exemplars to Engage Students with Assessment Criteria and Feedback.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 36 (1): 95–108. doi:10.1080/02602930903201669.

- Hart, C. 2018. Doing a Literature Review: Releasing the Research Imagination.” London: Sage.

- Heron, M. H., E. Medland, N. Winstone, and E. Pitt. 2023. “Developing the Relational in Teacher Feedback Literacy: Exploring Feedback Talk.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 48 (2): 172–185. doi:10.1080/02602938.2021.1932735.

- Hill, J., and H. West. 2020. “Improving the Student Learning Experience through Dialogic Feed-Forward Assessment.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 45 (1): 82–97. doi:10.1080/02602938.2019.1608908.

- Hoo, H. T., C. Deneen, and D. Boud. 2022. “Developing Student Feedback Literacy through Self and Peer Assessment Interventions.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 47 (3): 444–457. doi:10.1080/02602938.2021.1925871.

- Hui, L., K. Ippolito., M. Sarsfield., M. Charalambous. 2023. “Using a self-reflective ePortfolio and feedback dialogue to understand and address problematic feedback expectations.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2023.2232960

- Jensen, L. X., M. Bearman, and D. Boud. 2023. “Feedback Encounters: Towards a Framework for Analysing and Understanding Feedback Processes.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 48 (1): 121–134. doi:10.1080/02602938.2022.2059446.

- Kaufman, J. H., and C. D. Schunn. 2011. “Students’ Perceptions about Peer Assessment for Writing: Their Origin and Impact on Revision Work.” Instructional Science 39 (3): 387–406. doi:10.1007/s11251-010-9133-6.

- Klein, P. D., and D. van Dijk. 2019. “Writing as a Learning Activity.” In The Cambridge Handbook of Cognition and Education, edited by J. Dunlosky and K. A. Rawson, 266–291. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/9781108235631.012.

- Lipnevich, A. A., L. N. McCallen, K. P. Miles, and J. K. Smith. 2014. “Mind the Gap! Students’ Use of Exemplars and Detailed Rubrics as Formative Assessment.” Instructional Science 42 (4): 539–559. doi:10.1007/s11251-013-9299-9.

- Little, T., P. Dawson, D. Boud, and J. Tai. 2023. “Can Students’ Feedback Literacy Be Improved? A Scoping Review of Interventions.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education. doi:10.1080/02602938.2023.2177613.

- Maier, H. R. 2013. “What Constitutes a Good Literature Review and Why Does Its Quality Matter?” Environmental Modelling & Software 43: 3–4. doi:10.1016/j.envsoft.2013.02.004.

- Malcolm, M. 2023. “The Challenge of Achieving Transparency in Undergraduate Honours-Level Dissertation Supervision.” Teaching in Higher Education 28 (1): 101–117. doi:10.1080/13562517.2020.1776246.

- Malecka, B., R. Ajjawi, D. Boud, and J. Tai. 2022. “An Empirical Study of Student Action from Ipsative Design of Feedback Processes.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 47 (5): 801–815. doi:10.1080/02602938.2021.1968338.

- Malecka, B., D. Boud, and D. Carless. 2022. “Eliciting, Processing and Enacting Feedback: Mechanisms for Embedding Student Feedback Literacy within the Curriculum.” Teaching in Higher Education 27 (7): 908–922. doi:10.1080/13562517.2020.1754784.

- Molloy, E., D. Boud, and M. Henderson. 2020. “Developing a Learning-Centred Framework for Feedback Literacy.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 45 (4): 527–540. doi:10.1080/02602938.2019.1667955.

- Nicol, D. 2010. “From Monologue to Dialogue: Improving Written Feedback Processes in Mass Higher Education.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 35 (5): 501–517. doi:10.1080/02602931003786559.

- Nicol, D. 2019. “Reconceptualising Feedback as an Internal Not an External Process.” Italian Journal of Educational Research Special Issue : 71–83. https://ojs.pensamultimedia.it/index.php/sird/article/view/3270.

- Nicol, D. 2021. “The Power of Internal Feedback: Exploiting Natural Comparison Processes.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 46 (5): 756–778. doi:10.1080/02602938.2020.1823314.

- Nicol, D. 2022. Turning Active Learning into Active Feedback. Introductory Guide from Active Feedback Toolkit, Adam Smith Business School, National Teaching Repository. doi:10.25416/NTR.19929290.

- Nicol, D. J., and D. Macfarlane-Dick. 2006. “Formative Assessment and Self-Regulated Learning: A Model and Seven Principles of Good Feedback Practice.” Studies in Higher Education 31 (2): 199–218. doi:10.1080/03075070600572090.

- Nicol, D., and S. McCallum. 2022. “Making Internal Feedback Explicit: Exploiting the Multiple Comparisons That Occur during Peer Review.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 47 (3): 424–443. doi:10.1080/02602938.2021.1924620.

- Nicol, D., and G. Selvaretnam. 2022. “Making Internal Feedback Explicit: Harnessing the Comparisons Students Make during Two-Stage Exams.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 47 (4): 507–522. doi:10.1080/02602938.2021.1934653.

- Nicol, D., A. Thomson, and C. Breslin. 2014. “Rethinking Feedback Practices in Higher Education: A Peer Review Perspective.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 39 (1): 102–122. doi:10.1080/02602938.2013.795518.

- O’Connor, Anne, and Arlene McCurtin. 2021. “A Feedback Journey: Employing a Constructivist Approach to the Development of Feedback Literacy among Health Professional Learners.” BMC Medical Education 21 (1): 413–486. doi:10.1186/s12909-021-02914-2.

- Orsmond, P., and S. Merry. 2013. “The Importance of Self-Assessment in Students’ Use of Tutors’ Feedback: A Qualitative Study of High and Non-High Achieving Biology Undergraduates.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 38 (6): 737–753. doi:10.1080/02602938.2012.697868.

- Panadero, E., A. Lipnevich, and J. Broadbent. 2019. “Turning Self-Assessment into Self-Feedback.” In The Impact of Feedback in Higher Education, edited by M. Henderson, R. Ajjawi, D. Boud, and E. Molloy. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-25112-3_9.

- Roberts, L. D., and K. Seaman. 2018. “Good Undergraduate Dissertation Supervision: Perspectives of Supervisors and Dissertation Coordinators.” International Journal for Academic Development 23 (1): 28–40. doi:10.1080/1360144X.2017.1412971.

- Rovagnati, V., E. Pitt, and N. Winstone. 2022. “Feedback Cultures, Histories and Literacies: International Postgraduate Students’ Experiences.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 47 (3): 347–359. doi:10.1080/02602938.2021.1916431.

- Sambell, K., and L. Graham. 2020. “We Need to Change What We’re Doing.” Using Pedagogic Action Research to Improve Teacher Management of Exemplars.” Practitioner Research in Higher Education 13 (2): 3–17. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1267730.pdf.

- Sleker, T. D. 2005. “Without 1, Where Would We Begin?: Small Sample Research in Educational Settings.” Journal of Thought 40 (1): 79–86. https://www.jstor.org/stable/42589814.

- Smyth, P., and D. Carless. 2021. “Theorising How Teachers Manage the Use of Exemplars: Towards Mediated Learning from Exemplars.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 46 (3): 393–406. doi:10.1080/02602938.2020.1781785.

- Steen-Utheim, Anna, and Anne Line Wittek. 2017. “Dialogic Feedback and Potentialities for Student Learning.” Learning, Culture and Social Interaction 15: 18–30. doi:10.1016/j.lcsi.2017.06.002.

- Sutton, P. 2012. “Conceptualizing Feedback Literacy: Knowing, Being, and Acting.” Innovations in Education and Teaching International 49 (1): 31–40. doi:10.1080/14703297.2012.647781.

- Tai, J., M. Bearman, K. Gravett, and E. Molloy. 2023. “Exploring the Notion of Teacher Feedback Literacies through the Theory of Practice Architectures.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 48 (2): 201–213. doi:10.1080/02602938.2021.1948967.

- Tam, A. C. F. 2021. “Undergraduate Students’ Perceptions of and Responses to Exemplar-Based Dialogic Feedback.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 46 (2): 269–285. doi:10.1080/02602938.2020.1772957.

- Tomazin, L., A. Lipnevich, and C. Lopera-Oquendo. 2023. “Teacher Feedback vs. annotated Exemplars: Examining the Effects on Middle School Students’ Writing Performance.” Studies in Educational Evaluation 78: 101262. doi:10.1016/j.stueduc.2023.101262.

- Van der Kleij, F. M., L. E. Adie, and J. J. Cumming. 2019. “A Meta-Review of the Student Role in Feedback.” International Journal of Educational Research 98: 303–323. doi:10.1016/j.ijer.2019.09.005.

- Winstone, N. E., G. Mathlin, and R. A. Nash. 2019. “Building Feedback Literacy: Students’ Perceptions of the Developing Engagement with Feedback Toolkit.” Frontiers in Education 4. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2019.00039.

- Wood, J. 2021. “A Dialogic Technology-Mediated Model of Feedback Uptake and Literacy.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 46 (8): 1173–1190. doi:10.1080/02602938.2020.1852174.

- Wood, J. 2022. “Supporting the Uptake Process with Dialogic Peer Screencast Feedback: A Sociomaterial Perspective.” Teaching in Higher Education. doi:10.1080/13562517.2022.2042243.

- Yan, Z., and G. T. L. Brown. 2017. “A Cyclical Self-Assessment Process: Towards a Model of How Students Engage in Self-Assessment.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 42 (8): 1247–1262. doi:10.1080/02602938.2016.1260091.