?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

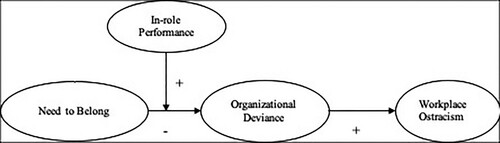

Although the need to belong, or the desire for interpersonal attachments, is a basic human motivation, understanding of how and when it influences workplace ostracism is notably limited. Based on belongingness theory, this study examines the negative relationship between the need to belong and exposure to workplace ostracism by focusing on the mediating role of organizational deviance and the moderating role of in-role performance. Data from 108 supervisor–subordinate dyads in China were collected at three time points. The results reveal that organizational deviance mediates the relationship between the need to belong and workplace ostracism. Additionally, in-role performance alleviates the negative relationship between the need to belong and organizational deviance. The implications for management theory and practice are discussed.

摘要

基于归属感理论,本研究通过聚焦于组织越轨行为的中介效应和角色内绩效的调节效应,探讨了归属感的需求对职场排斥的作用机制。通过分析三个阶段收集的108份领导-下属配对数据,研究结果表明:归属感的需求对职场排斥具有显著的负面作用;组织越轨行为在归属感的需求与职场排斥之间起中介作用,角色内绩效缓解了归属感的需求与组织越轨行为之间的负向关系。

Introduction

As the saying goes, no man is an island. All humans seek a sense of belonging and social connection (Baumeister et al., Citation2007; Brown et al., Citation2007; Carvallo & Gabriel, Citation2006). The need to belong, defined as the desire for interpersonal attachments, is a basic human motivation (Baumeister & Leary, Citation1995). Despite the basic need for belonging and social connection, little is known about how and when the need to belong helps individuals reduce ostracism in the workplace. Workplace ostracism is defined as ‘the extent to which an individual perceives that he or she is ignored or excluded by others’ in the workplace (Ferris et al., Citation2008, p. 1348). It is prevalent in organizations and has a destructive influence on employees (Lyu & Zhu, Citation2019; Scott & Duffy, Citation2015). A recent meta-analysis identified two main predictors of exposure to workplace ostracism, namely personality traits (e.g. the Big Five) and contextual characteristics (e.g. perceived leadership, social support), but indicated a nonsignificant and inconsistent relationship between the need to belong and workplace ostracism (Howard et al., Citation2020). This nonsignificant finding is surprising, as there is a theoretical link between belongingness and ostracism (Williams, Citation2001, Citation2007). In particular, scholars have used the need-threat/need-fortification framework to explain the relationship between the need to belong and ostracism. According to Williams (Citation2001), ostracism threatens the need to belong. Thus, the need to belong theoretically leads individuals to avoid provocative victim status, thereby reducing their likelihood of exposure to ostracism (Howard et al., Citation2020).

Despite this theoretical link between the need to belong and workplace ostracism, scholars have not provided consistent and robust evidence regarding how and when the need to belong prompts employees to decrease their exposure to workplace ostracism. Studying the effects of the need to belong on ostracism may provide evidence to support this theoretical link and, more importantly, suggest practical guidance for preventing ostracism, which has various negative outcomes, such as depression, job tension, emotional exhaustion, and turnover intention (Howard et al., Citation2020).

To advance the relevant theories and understand how and when the need to belong reduces the occurrence of workplace ostracism, we apply belongingness theory, which is based on two key assumptions. The first is that individuals avoid exhibiting inappropriate behaviors that destroy bonds and lead to their exclusion (Pickett et al., Citation2004). This argument suggests that inappropriate behavior serves as an important mechanism that mediates the need to belong and exposure to workplace ostracism. The second assumption is that people can fulfill their need to belong in various ways (Baumeister & Leary, Citation1995). This suggests that other channels that can help individuals fulfill their need to belong may buffer the effects of this need, and that decreasing inappropriate behavior is not the only way to achieve belongingness.

Accordingly, this study investigates the mediating role of organizational deviance and the moderating role of in-role performance in the relationship between the need to belong and workplace ostracism. Organizational deviance is unethical behavior that challenges organizational norms and may harm the organization (Bennett & Robinson, Citation2000; Robinson & Bennett, Citation1995, Citation1997; Robinson et al., Citation2014). Belongingness theory is not the only theory providing support for the claim that organizational deviance is an essential mediator. Bonding theory posits that people who are bonded to a social setting are less likely to demonstrate deviant behavior, which increases their opportunity to achieve acceptance (Bennett & Robinson, Citation2000). The victimization framework asserts that victims of mistreatment have a role or status with associated behaviors, and thus avoiding actions that contravene social norms helps them decrease their exposure to retaliatory ostracism (Aquino & Lamertz, Citation2004; Howard et al., Citation2020). Based on these arguments, we propose that the need to belong makes employees less likely to exhibit organizational deviance, thereby reducing the degree of workplace ostracism that they experience. In practical terms, identifying organizational deviance as a mediator can direct employees to avoid engaging in inappropriate behaviors to prevent ostracism.

In-role performance refers to ‘the effectiveness with which employees carry out their formally-prescribed job responsibilities (i.e. their in-role behavior)’ (Turnley et al., Citation2003, p. 189). In-role performance and deviant behavior represent the positive and negative components of overall job performance (Dalal et al., Citation2009), and they have interdependent effects (Dalal et al., Citation2009). We argue that in-role performance is an important channel through which employees can fulfill their need to belong. Thus, decreasing organizational deviance is not the only way to achieve belongingness. However, in-role performance is relatively stable, and employees have limited freedom to adjust it because they must perform at a certain level to survive in an organization (Organ, Citation1977). In-role performance is also likely to be constrained by age (Ng & Feldman, Citation2008) and cognitive ability (LePine & Van Dyne, Citation2001). Additionally, it has a weaker relationship with workplace ostracism than organizational deviance does (Howard et al., Citation2020). Hence, we consider in-role performance as a moderator and organizational deviance as a mediator.

Employees with a high level of in-role performance complete tasks successfully and position themselves favorably in the workplace. They are regarded as high performers because they stand out professionally (Tepper et al., Citation2011). Additionally, their ability and competence are highly respected by other organizational members, who tend to form favorable impressions of high performers. Respect and good impressions indicate high performers’ acceptance by others. Hence, high performers’ need to belong is not likely to be activated, thereby mitigating the effect of the need to belong on organizational deviance. Conversely, low performers cannot earn respect or make good impressions based on their performance. Thus, their need to belong is likely to be activated, motivating them to find ways to earn acceptance from their colleagues.

This study makes three important contributions to the literature. First, we integrate the need to belong and workplace ostracism into a single model based on belongingness theory. This approach answers the call to study the relationship between belongingness and ostracism (Williams, Citation2007). Second, we contribute to belongingness theory by focusing on the mediating role of organizational deviance in the relationship between the need to belong and workplace ostracism. Examining this mediating mechanism deepens our understanding of how the need to belong directs individuals toward behaviors that reduce workplace ostracism and provides evidence that organizational deviance is the bridge linking the need to belong to workplace ostracism. Third, we test the boundary condition of belongingness theory by examining the moderating role of in-role performance in both the main effect (i.e. on organizational deviance) and the indirect effect (i.e. on workplace ostracism via reduced organizational deviance) of the need to belong. In this way, we clarify who benefits most from the need to belong and develop practical implications by identifying leverage points for strengthening the influence of the need to belong. In sum, our key contribution is our incorporation of the mediating and moderating mechanisms into a single model that explains how and when the need to belong reduces workplace ostracism based on belongingness theory. presents our research model.

To test our theoretical model and hypotheses, we conducted a time-lagged survey study and collected supervisor–subordinate dyadic data from a consulting firm in China. This research design helped to alleviate concern regarding common method bias and to apply belongingness theory to a service industry in an Eastern cultural context.

Hypothesis development

Belongingness theory has three main components that guide our hypothesis development. First, the need to belong motivates individuals to maintain their interpersonal attachments and pursue acceptance from others (Baumeister & Leary, Citation1995). Hence, we propose that employees with a high need to belong are inclined to pursue acceptance from their colleagues. Second, the need to belong typically leads individuals to avoid conflict via behavioral and emotional reactions (Baumeister & Leary, Citation1995; Carvallo & Pelham, Citation2006). We therefore propose that employees with a high need to belong are likely to avoid behaviors that inconvenience others. In particular, such employees will tend to reduce behaviors characterized by organizational deviance in an effort to avoid conflict with and facilitate acceptance by others. Finally, people can fulfill their need to belong by developing connections and contributing in many contexts, such as workplace, society, family, school, and community environments (Baumeister & Leary, Citation1995; Thompson & McRae, Citation2001). The need to belong in organizations can be fulfilled in many ways. Reducing deviant behavior is one way to avoid conflict and exclusion. Another is to excel at one’s job, as this allows employees to effectively show their organization and colleagues their contributions (Dalal et al., Citation2009). As a high degree of in-role performance can meet employees’ need to avoid exclusion (Howard et al., Citation2020), we propose that the effects of the need to belong on organizational deviance may be alleviated by a high degree of in-role performance.

Need to belong, organizational deviance, and workplace ostracism

Belongingness theory contends that individuals desire to maintain attachments and behave in ways that minimize conflict (Baumeister & Leary, Citation1995). Satisfying the need to belong produces a host of positive outcomes, such as the sense of living a meaningful life and fitting in (Dewall et al., Citation2011; Lambert et al., Citation2013), job satisfaction (O’Reilly et al., Citation2015), the subjective experience of positive relationships (Pickett et al., Citation2004), shared social identity (Haslam et al., Citation2009), cooperation (De Cremer & Leonardelli, Citation2003), and connection to social change (May, Citation2011). In contrast, a thwarted need to belong is associated with detrimental physical, psychological, and work-related consequences, such as health problems (O’Reilly et al., Citation2015), anger and aggression (Leary et al., Citation2006), hurt feelings (Leary & Leder, Citation2009), social anxiety (Brown et al., Citation2007), decisional frustration (De Cremer & Leonardelli, Citation2003), discrimination (Carvallo & Pelham, Citation2006), and bullying (Underwood & Ehrenreich, Citation2014).

Individuals are inclined to follow norms and regulations to establish and maintain positive relationships, and they are likely to avoid behaviors that may offend others. Similarly, bonding theory posits that people who feel attached to social institutions are inclined to control themselves and suppress deviant behaviors to gain acceptance (Bennett & Robinson, Citation2000). The victimization framework identifies aggressive and hostile behaviors that may lead others to retaliate against perpetrators (Aquino & Lamertz, Citation2004). Organizational deviance is a type of aggressive and harmful behavior that occurs in the workplace (Robinson & Bennett, Citation1995). It can be assumed that individuals who engage in such deviant behavior risk backlash from colleagues who suffer from or observe the behavior. For example, there is evidence that the relationship between the exhibition of organizational deviance and exposure to abusive supervision is reciprocal (Lian et al., Citation2014). As argued earlier, people with a strong need to belong are particularly attuned to others’ perceptions and evaluations (Carvallo & Pelham, Citation2006). As these people are eager to establish and maintain interpersonal attachments in the workplace, they tend to exhibit less organizational deviance. Based on the above reasoning, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1: The need to belong is negatively related to organizational deviance.

Scholars have identified various antecedents of ostracism. For example, research has shown that neuroticism is positively associated with workplace ostracism, whereas agreeableness and extraversion are negatively associated with it (Wu et al., Citation2011). Other factors that lead to employee ostracism include envy (Mao et al., Citation2020), competitive goal interdependence, conflict with supervisors (Wu et al., Citation2015), and failure to conform to others’ opinions (Williams et al., Citation2000).

Drawing on belongingness theory, we posit that individuals tend to ostracize those who violate social norms (Baumeister & Leary, Citation1995). Social norms are behavioral standards expected by organizational members and are important for organizational effectiveness and functioning (Howard et al., Citation2020). In the workplace, where relationships have many subtle and uncertain aspects (Fiset et al., Citation2017), individuals use ostracism as a punitive or defensive approach to show their displeasure with those who break social norms without directly confronting them (Wu et al., Citation2015).

The mistreatment of others is regarded as a threat to relationships and effectiveness in the workplace (Scott et al., Citation2013). Organizational deviance represents a detrimental form of job performance, which includes unfavorable behaviors (e.g. violating safety guidelines, destroying facilities) and illegal behaviors (e.g. stealing, drug abuse; Rotundo & Sackett, Citation2002). Employees who exhibit organizational deviance are regarded as social liabilities at work and are thus targeted for workplace ostracism. Therefore, workplace ostracism may be a response to organizational deviance intended to keep employees in line. In other words, workplace ostracism may be intended to induce a behavioral change by ostracizing ‘bad apples’ who exhibit organizational deviance. A meta-analytic study found a positive relationship between the exhibition of workplace deviance and perceptions of workplace ostracism (Howard et al., Citation2020). Hence, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2: Organizational deviance is positively related to workplace ostracism.

Belongingness theory also suggests that behavioral responses play a mediating role in the relationship between the need to belong and acceptance (Baumeister & Leary, Citation1995). Researchers have recently proposed that ‘those with a need to belong are more likely to be cognizant of their social connections and less likely to perform behaviors that cause conflict resulting in ostracism’ (Howard et al., Citation2020, p. 581). This statement suggests that hostile behavior plays a mediating role in the association between the need to belong and workplace ostracism. Hence, we propose that organizational deviance mediates the negative relationship between the need to belong and perceptions of workplace ostracism. In other words, employees with a strong need to belong are less likely to exhibit organizational deviance, which reduces their risk of ostracism by colleagues. As such, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3: Organizational deviance mediates the relationship between the need to belong and workplace ostracism.

Moderating role of in-role performance

Belongingness theory suggests that people can fulfill their need to belong in various ways (Baumeister & Leary, Citation1995; Thompson & McRae, Citation2001). As noted above, in-role performance and deviant behavior are two key components of overall job performance (Dalal et al., Citation2009). In-role performance is relatively stable (Organ, Citation1977), whereas deviant behavior fluctuates daily due to its discretionary nature (Dalal et al., Citation2009). Therefore, we propose that in-role performance moderates the relationship between the need to belong and organizational deviance for the following reason.

Employees who demonstrate a low degree of in-role performance (low performers) tend to become targets for hostility because they signal low utility and may be harmful or threatening (Tepper et al., Citation2011). They make their colleagues look bad by negatively influencing shared tasks. This puts low performers at risk of exclusionary acts. Facing such unfavorable circumstances, low performers’ need to belong is activated, motivating them to avoid further provocation of their victim status. An effective way to achieve this is to suppress organizational deviance. Consequently, employees who perform poorly but wish to fulfill their need to belong are likely to reduce their organizational deviance. This circumstance is similar to the situation in which a person pays more attention to acquiring and storing food when their need to eat is at risk and thus activated (Maslow, Citation1954).

Conversely, a high level of in-role performance indicates a high degree of contribution to the organization. By virtue of their contribution to the organization, employees with high in-role performance attain high status. Research has shown that individual productivity is positively related to social status (Flynn, Citation2003). As status and acceptance are often correlated (Anderson et al., Citation2015), high status can represent a low risk of experiencing workplace ostracism (Cullen et al., Citation2014; Wu et al., Citation2020). As high performers work in favorable and secure environments, their need to belong is less likely to be activated. As such, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 4: In-role performance moderates the negative relationship between the need to belong and organizational deviance such that the relationship is stronger when in-role performance is low rather than high.

Hypothesis 5: In-role performance moderates the indirect effect of the need to belong on workplace ostracism via organizational deviance such that this indirect effect is stronger when the level of in-role performance is low rather than high.

Methods

Sample and procedures

Data were collected from supervisor–subordinate dyads in a newly established (less than one year old) consulting firm in China. All 137 new frontline employees and their supervisors were targeted. Collecting data from two sources in field surveys is a common approach (e.g. Lee et al., Citation2017) that alleviates concerns surrounding common method bias (Podsakoff et al., Citation2003). A new employee is a person who has been recently hired and has no past work experience with the hiring organization (Son & Ok, Citation2019). Newcomers were targeted because they are likely to adjust their behaviors in the early socialization stages (Firth et al., Citation2014) and because they seek to fulfill basic psychological needs (Wu et al., Citation2019).

Participation was voluntary, and all of the respondents were promised anonymity in their responses. The questionnaires were coded before distribution. With the help of administrative staff, one of the researchers collected the survey data during work hours. To encourage participation, each respondent was gifted a notebook as an incentive.

A three-wave research design was used to test the hypothesized relationships between the key variables. At Time 1, data associated with the employees’ demographic variables, their need to belong, and their supervisors’ ratings of their in-role performance were collected. To avoid burdening the supervisors, each supervisor rated only one subordinate. When more than one subordinate respondent was possible, the respondent was randomly selected by drawing a number from a box. A total of 134 employee questionnaires and 130 supervisor questionnaires were returned, resulting in response rates of 97.8% for employees and 94.9% for supervisors. One month later, at Time 2, the supervisors were asked to rate their employee’s organizational deviance during the past month. A total of 120 supervisor questionnaires were returned, a response rate of 87.6%. One month later, at Time 3, the employees were asked to report their perceptions of workplace ostracism during the past month. A total of 115 employee questionnaires were returned, a response rate of 83.9%. To determine data collection intervals, the literature on the predictors of exposure to workplace ostracism was reviewed. Wide disparities were discovered between previous time-lagged field studies’ data collection intervals, ranging from 10 days (Wu et al., Citation2019) to 4 months (Wu et al., Citation2011). As we were examining a moderated mediation model that shows both underlying and interaction effects, a relatively long interval was applied to allow the respondents to evaluate, take action, and perceive reactions from their colleagues.

In total, 108 dyadic supervisor–subordinate data sets were collected, representing 78.8% of the targeted dyads. Following the suggestion of Goodman and Blum (Citation1996), the systematic response differences between the three data collection waves were examined using multiple logistic regression analyses and t-tests. No significant differences were found in the key variables across the three surveys. Hence, we suggest that targeted participants randomly dropped out of the study.

Of the 108 employees, 68 were female and 40 were male. In terms of educational background, 4 had a high-school level education or below, 9 had an associate degree, 46 had a Bachelor’s degree, and 50 had a Master’s degree or above. Eighty-eight employees (81.48%) were under 30 years old.

Measures

The questionnaires were in Chinese, but the key scales were originally developed in English. Scholars who have investigated in-role performance, organizational deviance, and workplace ostracism in Chinese settings were asked to provide the Chinese versions of their scales. One author translated the need to belong items from English to Chinese. Another author then back-translated those Chinese items to ensure measurement equivalence. Following the recommendations for back-translation, the Chinese and English versions of the measure were compared; all of the keywords were replicated in the back-translation (Brislin, Citation1970; Brislin & Freimanis, Citation2001). The responses to all of the items except the demographic variables ranged from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

Need to belong

A 10-item scale developed by Leary et al. (Citation2013) was used to measure the need to belong. A sample item reads as follows: ‘I need to feel that there are people I can turn to in times of need.’ Three of the items are reverse-coded so that higher scores represent higher levels of the need to belong. Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was .90.

In-role performance

A 5-item scale originally developed by Williams (Citation1988) and later adapted by Hui et al. (Citation1999) in a Chinese setting was used to measure in-role performance. A sample item reads as follows: ‘[The subordinate] fulfilled responsibilities specified in the job description.’ Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was .95.

Organizational deviance

A 12-item scale originally developed by Bennett and Robinson (Citation2000) and later applied by Wang et al. (Citation2012) in a Chinese setting was used to measure organizational deviance. A sample item reads as follows: ‘[The subordinate] spent too much time fantasizing or daydreaming instead of working.’ Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was .98.

Workplace ostracism

A 10-item scale originally developed by Ferris et al. (Citation2008) and later applied by Wu et al. (Citation2012) in a Chinese setting was used to measure workplace ostracism. A sample item reads as follows: ‘Others ignored me at work.’ Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was .98.

Control variables

The employees’ demographic variables were controlled for because they may affect job performance (Choi & Lee, Citation2014; Ng & Feldman, Citation2008) and/or workplace ostracism (Wu et al., Citation2015). Age had four categories: 29 years old or under, 30–39 years old, 40–49 years old, and 50 years old or above. Gender was dummy coded as 0 for male and 1 for female. Education had four categories: high school diploma or below, associate degree, Bachelor’s degree, and Master’s degree or above. Organizational tenure was measured by the number of months that a respondent had been with the company.

Results

Confirmatory factor analysis

To examine the distinctiveness of the variables, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted with Mplus 7.4. Due to the small sample size, the ratio of the number of cases to the number of items was less than five, which is not appropriate for factor analysis (Hair et al., Citation1998). To meet the gold standard associated with the model fit indices (Williams & O’Boyle, Citation2008), a common parceling approach was used to reduce the number of indicators (Little et al., Citation2002). According to the exploratory factor analysis results, the highest factor loading items were combined with the lowest factor loading items by taking their average until three to five aggregate items were obtained for each form (see Appendix 1).

As shows, the proposed four-factor model demonstrated better fit than the alternative models, with acceptable model fit indices (χ2 = 285.32, df = 146, CFI = .95, TLI = .95, RMSEA = .09, SRMR = .04). The one-, two-, and three-factor models yielded unacceptable fit indices. These results support the discriminant validity of the key variables.

Table 1. Results of confirmatory factor analyses.

Descriptive statistics

presents the means, standard deviations, and correlations of the variables. The need to belong was negatively correlated with organizational deviance (r = −.23, p < .05) and workplace ostracism (r = −.19, p < .05). Additionally, organizational deviance was positively correlated with workplace ostracism (r = .26, p < .01). All of these findings provide preliminary support for Hypotheses 1, 2, and 3. Regarding the demographic variables, only gender was significantly correlated with workplace ostracism (r = −.22, p < .05). The nonsignificant relationships of workplace ostracism with age, education, and tenure may be explained by the small sample size. Furthermore, checking the normality results revealed that the Q-Q plots of the four key variables showed that the dots were very close to a diagonal line, representing a normal distribution.

Table 2. Means, standard deviations, and correlations among variables.

Hypothesis testing

Hierarchical regression and bootstrapping analyses were conducted to test the proposed hypotheses. Hypothesis 1 predicts that the need to belong is negatively related to organizational deviance. Hypothesis 2 predicts that organizational deviance is positively related to workplace ostracism. As the hierarchical regression analysis results in show, the need to belong had a significant negative effect on organizational deviance (β = −.22, p < .05, Model 2), and organizational deviance had a significant positive effect on workplace ostracism (β = .26, p < .05, Model 7). Therefore, Hypotheses 1 and 2 were supported.

Table 3. Results of regression analysis.

Hypothesis 3 proposes that organizational deviance mediates the relationship between the need to belong and workplace ostracism. The bootstrapping analyses recommended by Hayes (Citation2009) were conducted. The indirect effect of the need to belong on workplace ostracism via organizational deviance was significant. The 95% confidence interval based on 1,000 bootstrap samples of the indirect effect was [−.12, −.01], excluding zero. Thus, Hypothesis 3 was supported.

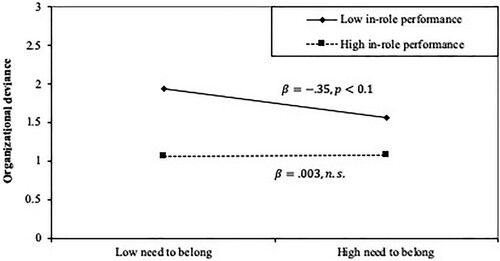

Hypothesis 4 proposes that in-role performance moderates the relationship between the need to belong and organizational deviance. As shows, the interaction between the need to belong and in-role performance was positively related to organizational deviance (β = .27, p < .05, Model 4). illustrates the interaction effects using the slopes one standard deviation above and below the mean score of in-role performance, consistent with the approach of Dawson (Citation2014). The interaction patterns support Hypothesis 4. In particular, the negative relationship between the need to belong and organizational deviance was stronger when in-role performance was low (β = −.35, p < .01, one standard deviation below the mean) rather than high (β = .00, n.s., one standard deviation above the mean).

Figure 2. Effect of the interaction of need to belong and in-role performance on organizational deviance.

Hypothesis 5 predicts that in-role performance moderates the indirect effect of the need to belong on workplace ostracism via organizational deviance. Following Edwards and Lambert (Citation2007), the moderated path analysis method was used to test Hypothesis 5. The findings in show that the indirect effect of the need to belong on workplace ostracism through organizational deviance was not moderated by in-role performance (β = −.04, n.s.), rejecting Hypothesis 5. However, the results in indicate that in-role performance moderated the relationship between the need to belong and organizational deviance (i.e. the first-stage effect;

γ = .35, p < .01), further supporting Hypothesis 4.

Table 4. The interactive effect of need to belong, and in-role performance on workplace ostracism.

Discussion

Belongingness research has left no doubt that the need to belong influences individuals’ likelihood of being accepted (Baumeister & Leary, Citation1995). We provide empirical evidence to support the theoretical link between the need to belong and workplace ostracism. In particular, we find that organizational deviance mediates the relationship between the need to belong and workplace ostracism. In addition, in-role performance alleviates the main effect of the need to belong on organizational deviance. These findings have several important theoretical and managerial implications.

First, this study contributes to the belongingness literature by applying belongingness theory (Baumeister & Leary, Citation1995) and integrating the need to belong and workplace ostracism. This approach answers the call to link belongingness and ostracism (Williams, Citation2007). The pursuit of belonging motivates individuals to eliminate the negative states associated with feelings of exclusion and bitterness (Dewall & Bushman, Citation2011). Examining the need to belong widens the scope of antecedents to workplace ostracism by focusing on motivational predictors (Williams & Sommer, Citation1997). As discussed earlier, studies have focused on personalities (e.g. Wu et al., Citation2011) and work contexts (e.g. Wu et al., Citation2015) to account for exposure to workplace ostracism (see Mao et al., Citation2018, for a review). Inconsistent with the conventional wisdom regarding the negative relationship between the need to belong and ostracism (Williams, Citation2007), a recent meta-analytic study provided evidence of a nonsignificant relationship between the need to belong and workplace ostracism (Howard et al., Citation2020). Studies have focused on the moderating role of the need to belong in buffering the destructive effects of exposure to workplace ostracism, but have not considered the main effect of the need to belong on workplace ostracism (Eck et al., Citation2017; Yang & Treadway, Citation2018). We were inspired by these studies to investigate the association between the need to belong and workplace ostracism using a fine-grained approach. Drawing on belongingness theory (Baumeister & Leary, Citation1995), this study is one of the first attempts to empirically bridge the research divide between the need to belong and workplace ostracism. We hope that our findings will stimulate future research on the motivational antecedents of workplace ostracism.

Second, this study contributes to the literature by exploring the mediating role of organizational deviance to explain the underlying behavioral mechanism that links the need to belong and workplace ostracism. Although research has provided evidence linking personality traits with perceptions of workplace ostracism (Wu et al., Citation2011), the mediating mechanism has not been explored. Therefore, it is unclear how and why individual characteristics result in employees’ exposure to workplace ostracism. Belongingness theory suggests that individuals driven by belonging-related motivations engage in fewer destructive behaviors, thereby increasing their likelihood of acceptance by others (Baumeister & Leary, Citation1995). Commitment to reducing organizational deviance has been conceptualized as an effective tool to avoid rejection by colleagues. This study extends the application of belongingness theory by regarding organizational deviance as a key mediator to explain why people with a high need to belong are less likely to experience workplace ostracism. Future research may investigate the mediating role of organizational deviance in the relationship between other individual characteristics and exposure to workplace ostracism or to other deviant behaviors, such as bullying, gossip, incivility, and sexual harassment (Anasori et al., Citation2020; Robinson & Bennett, Citation1995; Tian et al., Citation2019).

Third, this study provides evidence that in-role performance serves as a boundary condition for the effect of the need to belong on organizational deviance. A high degree of in-role performance is perceived by organizational members as a high level of contribution to the organization. This favorable situation is not likely to activate the need to belong. However, low performers sense their unfavorable circumstances, which activates their need to belong. Importantly, our findings add a consideration of in-role performance to the belongingness literature. Based on the argument of belongingness theory that the need to belong can be fulfilled in various ways (Baumeister & Leary, Citation1995), our finding regarding the moderating role of in-role performance in alleviating the negative relationship between the need to belong and organizational deviance bridges the gap between in-role performance and belongingness.

However, our findings also reveal that in-role performance does not moderate the indirect effect of the need to belong on workplace ostracism through organizational deviance. Other mediators not considered in this study (e.g. those that are important in avoiding rejection, such as citizenship behavior and creative behavior) may have roles that are moderated by in-role performance. Future research may include other mediators to explain the mechanism underlying the relationship between the need to belong and workplace ostracism.

Recent meta-analytic research has provided evidence of the positive relationship between the exhibition of workplace deviance and exposure to workplace ostracism (Howard et al., Citation2020), which is consistent with our findings. Researchers have also examined whether the relationship between deviance and workplace ostracism differs when deviance is measured before workplace ostracism (e.g. Peng & Zeng, Citation2017; Quade et al., Citation2017) and when deviance is measured after workplace ostracism (e.g. Ferris et al., Citation2015; Yang & Treadway, Citation2018). The meta-analytic effect sizes of these two methodological designs are comparable, without significant differences (Howard et al., Citation2020). We apply belongingness theory to propose that organizational deviance is a proximal outcome of the need to belong and that workplace ostracism is a relatively distal outcome influenced by the need to belong (Baumeister & Leary, Citation1995). Our approach thus supports the claim that organizational deviance may be better conceptualized as a predictor of workplace ostracism (Howard et al., Citation2020).

Consistent with Howard et al. (Citation2020), our correlation analyses indicate that gender is significantly correlated with workplace ostracism, but age and tenure are not. In particular, men are more likely than women to perceive workplace ostracism. Surprisingly, our findings indicate a nonsignificant relationship between education and workplace ostracism, which is inconsistent with the meta-analytic finding that employees with high education levels tend to perceive workplace ostracism (Howard et al., Citation2020). Generally, our findings support the claim that demographic variables only have weak relationships with workplace ostracism (Howard et al., Citation2020).

Practical implications

Our findings have several managerial implications. First, belongingness can serve as a form of therapy by assisting individuals who endure frequent or lengthy episodes of ostracism (Williams, Citation2007). As the need to belong is a key human motivation for interpersonal attachments (Baumeister & Leary, Citation1995), it deserves recognition in the workplace through managerial practices that seek to mitigate organizational deviance and thereby minimize workplace ostracism. It is critical for organizations to recognize the negative association between belongingness and organizational deviance and workplace ostracism. Organizations can implement belongingness support programs that include training and opportunities for interactions (Ozcelik & Barsade, Citation2018). These programs may focus on satisfying individuals’ need to belong and managing motivations to reduce the occurrence of workplace ostracism. Organizations should also foster environments that facilitate individuals’ pursuit of belonging.

Second, our results show that organizational deviance mediates the relationship between the need to belong and workplace ostracism. For organizations and managers, this underscores the importance of paying attention to organizational deviance (Bennett & Robinson, Citation2000). Organizations seeking to reduce workplace ostracism should discourage managers and employees from engaging in organizational deviance. To reduce organizational deviance, managers and employees should be trained to build positive relationships in the workplace, such as supportive, high-quality relationships between leaders and members (Ferris et al., Citation2009).

Finally, we find that in-role performance moderates the negative relationship between the need to belong and organizational deviance, such that the relationship is stronger when in-role performance is low rather than high. Hence, organizations should pay close attention to employees with high in-role performance and help them to build healthy relationships in the workplace.

Limitations

Several potential limitations of this study are worth mentioning. Organizational deviance was measured using supervisor ratings to avoid common method bias (Podsakoff et al., Citation2003), but supervisors may not accurately judge their subordinates’ organizational deviance, as it is impossible for them to observe their subordinates’ behaviors at all times. Individuals may hide their deviant behaviors and pretend to engage in positive behaviors to secure promotions. Therefore, we encourage future studies to use different sources, including peers, to rate focal employees’ organizational deviance.

Second, all of the respondents were Chinese, which may limit the generalizability of the results. Chinese culture has a high degree of collectivism, and thus, Chinese people are more likely to be influenced by the need to belong than people from Western cultures are. Cross-cultural research comparing the findings of Chinese and Western samples is desirable.

Third, a time-lagged research design was applied in this study, which cannot provide solid evidence for causal relationships (Law et al., Citation2016). Exposure to workplace ostracism may lead targets to exhibit organizational deviance. Therefore, we call for a longitudinal study to measure all of the variables at each time point.

Fourth, we did not include others’ ostracizing behaviors in the proposed model. Yang and Treadway (Citation2018) indicated that the link between coworkers’ ostracizing behaviors and perceptions of such behaviors is moderated by victims’ need to belong. More specifically, employees with a high need to belong are more likely to detect others’ ostracizing behaviors and develop perceptions of such behaviors than employees with a low need to belong. To rule out this possibility, colleagues should be asked to rate their own ostracizing behaviors toward the focal employee.

Finally, all of the respondents were newcomers, which may limit the generalizability of our findings to other settings. As newcomers do not have a network or experience in the organization, they may not be able to perceive ostracism accurately as they lack relationships with other organizational members. However, a recent meta-analysis showed that tenure does not affect exposure to workplace ostracism (Howard et al., Citation2020). Hence, our findings may be generalizable to employees with longer tenure. Nevertheless, we call for future research to test our model with general employees.

Conclusion

Drawing on belongingness theory, we focus on fundamental human motivations and show how the need to belong is negatively associated with perceptions of workplace ostracism. Our results indicate that organizational deviance is an important mediator of the link between the need to belong and workplace ostracism. In-role performance moderates the negative relationship between the need to belong and organizational deviance such that the relationship is stronger when in-role performance is low rather than high. By advancing a model linking the need to belong and workplace ostracism, we offer a new perspective on the mechanisms involved in this relationship.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Anasori, E., Bayighomog, S. W., & Tanova, C. (2020). Workplace bullying, psychological distress, resilience, mindfulness, and emotional exhaustion. The Service Industries Journal, 40(1-2), 65–89. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02642069.2019.1589456

- Anderson, C., Hildreth, J. A. D., & Howland, L. (2015). Is the desire for status a fundamental human motive? A review of empirical literature. Psychological Bulletin, 141(3), 574–601. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038781

- Aquino, K., & Lamertz, K. (2004). A relational model of workplace victimization: Social roles and patterns of victimization in dyadic relationships. Journal of Applied Psychology, 89(6), 1023–1034. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.89.6.1023

- Baumeister, R. F., Brewer, L. E., Tice, D. M., & Twenge, J. M. (2007). Thwarting the need to belong: Understanding the interpersonal and inner effects of social exclusion. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 1(1), 506–520. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2007.00020.x

- Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117(3), 497–529. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.497

- Bennett, R. J., & Robinson, S. L. (2000). Development of a measure of workplace deviance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85(3), 349–360. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.85.3.349

- Brislin, R. W. (1970). Back-translation for cross-cultural research. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 1(3), 185–216. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/135910457000100301

- Brislin, R. W., & Freimanis, C. (2001). Back-translation. In S.-W. Chan & D. E. Pollard (Eds.), An encyclopedia of translation: Chinese-English, English-Chinese (pp. 22–40). Chinese University Press.

- Brown, L. H., Silvia, P. J., Myin-Germeys, I., & Kwapil, T. R. (2007). When the need to belong goes wrong: The expression of social anhedonia and social anxiety in daily life. Psychological Science, 18(9), 778–782. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01978.x

- Carvallo, M., & Gabriel, S. (2006). No man is an island: The need to belong and dismissing avoidant attachment style. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 32(5), 697–709. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167205285451

- Carvallo, M., & Pelham, B. W. (2006). When fiends become friends: The need to belong and perceptions of personal and group discrimination. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 90(1), 94–108. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.90.1.94

- Choi, Y., & Lee, D. (2014). Psychological capital, Big five traits, and employee outcomes. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 29(2), 122–140. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/JMP-06-2012-0193

- Cullen, K. L., Fan, J., & Liu, C. (2014). Employee popularity mediates the relationship between political skill and workplace interpersonal mistreatment. Journal of Management, 40(6), 1760–1778. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206311435104

- Dalal, R. S., Lam, H., Weiss, H. M., Welch, E. R., & Hulin, C. L. (2009). A within-person approach to work behavior and performance: Concurrent and lagged citizenship-counter productivity associations, and dynamic relationships with affect and overall job performance. Academy of Management Journal, 52(5), 1051–1066. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2009.44636148

- Dawson, J. F. (2014). Moderation in management research: What, why, when and how. Journal of Business and Psychology, 29(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-013-9308-7

- De Cremer, D., & Leonardelli, G. J. (2003). Cooperation in social dilemmas and the need to belong: The moderating effect of group size. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice, 7(2), 168–174. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2699.7.2.168

- Dewall, C. N., Anderson, C. A., & Bushman, B. J. (2011). The general aggression model: Theoretical extensions to violence. Psychology of Violence, 1(3), 245–258. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/a0023842

- Dewall, C. N., & Bushman, B. J. (2011). Social acceptance and rejection: The sweet and the bitter. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 20(4), 256–260. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721411417545

- Eck, J., Schoel, C., & Greifeneder, R. (2017). Belonging to a majority reduces the immediate need threat from ostracism in individuals with a high need to belong. European Journal of Social Psychology, 47(3), 273–288. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2233

- Edwards, J. R., & Lambert, L. S. (2007). Methods for integrating moderation and mediation: A general analytical framework using moderated path analysis. Psychological Methods, 12(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.12.1.1

- Ferris, D. L., Brown, D. J., Berry, J. W., & Lian, H. (2008). The development and validation of the workplace ostracism scale. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(6), 1348–1366. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/a0012743

- Ferris, D. L., Brown, D. J., & Heller, D. (2009). Organizational supports and organizational deviance: The mediating role of organization-based self-esteem. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 108(2), 279–286. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2008.09.001

- Ferris, D. L., Lian, H., Brown, D. J., & Morrison, R. (2015). Ostracism, self-esteem, and job performance: When do we self-verify and when do we self-enhance? Academy of Management Journal, 58(1), 279–297. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2011.0347

- Firth, B. M., Chen, G., Kirkman, B. L., & Kim, K. (2014). Newcomers abroad: Expatriate adaptation during early phases of international assignments. Academy of Management Journal, 57(1), 280–300. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2011.0574

- Fiset, J., Hajj, R. A., & Vongas, J. G. (2017). Workplace ostracism seen through the lens of power. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1–19. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01528

- Flynn, F. J. (2003). How much should I give and how often? The effects of generosity and frequency of favor exchange on social status and productivity. Academy of Management Journal, 46(5), 539–553. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5465/30040648

- Goodman, J. S., & Blum, T. C. (1996). Assessing the non-random sampling effects of subject attrition in longitudinal research. Journal of Management, 22(4), 627–652. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/014920639602200405

- Hair, J. E., Anderson, R. E., Tatham, R. L., & Black, W. C. (1998). Multivariate data analysis (5th ed.). Prentice Hall.

- Haslam, S. A., Jetten, J., Postmes, T., & Haslam, C. (2009). Social identity, health and well-being: An emerging agenda for applied psychology. Applied Psychology, 58(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.2008.00379.x

- Hayes, A. F. (2009). Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Communication Monographs, 76(4), 408–420. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/03637750903310360

- Howard, M. C., Cogswell, J. E., & Smith, M. B. (2020). The antecedents and outcomes of workplace ostracism: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 105(6), 577–596. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000453

- Hui, C., Law, K. S., & Chen, Z. X. (1999). A structural equation model of the effects of negative affectivity, leader-member exchange, and perceived job mobility on in-role and extra-role performance: A Chinese case. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 77(1), 3–21. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1006/obhd.1998.2812

- Kwan, H. K., Zhang, X., Liu, J., & Lee, C. (2018). Workplace ostracism and employee creativity: An integrative approach incorporating pragmatic and engagement roles. Journal of Applied Psychology, 103(12), 1358–1366. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000320

- Lambert, N. M., Stillman, T. F., Hicks, J. A., Kamble, S., Baumeister, R. F., & Fincham, F. D. (2013). To belong is to matter: Sense of belonging enhances meaning in life. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 39(11), 1418–1427. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167213499186

- Law, K. S., Wong, C.-S., Yan, M., & Huang, G. (2016). Asian researchers should be more critical: The example of testing mediators using time-lagged data. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 33(2), 319–342. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-015-9453-9

- Leary, M. R., Kelly, K. M., Cottrell, C. A., & Schreindorfer, L. S. (2013). Construct validity of the need to belong scale: Mapping the nomological network. Journal of Personality Assessment, 95(6), 610–624. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2013.819511

- Leary, M. R., & Leder, S. (2009). The nature of hurt feelings: Emotional experience and cognitive appraisals. In A. Vangelisti (Ed.), Feeling hurt in close relationships (pp. 15–33). Cambridge University Press.

- Leary, M. R., Twenge, J. M., & Quinlivan, E. (2006). Interpersonal rejection as a determinant of anger and aggression. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 10(2), 111–132. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327957pspr1002_2

- Lee, D., Choi, Y., Youn, S., & Chun, J. U. (2017). Ethical leadership and employee moral voice: The mediating role of moral efficacy and the moderating role of leader–follower value congruence. Journal of Business Ethics, 141(1), 47–57. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2689-y

- LePine, J. A., & Van Dyne, L. (2001). Voice and cooperative behavior as contrasting forms of contextual performance: Evidence of differential relationships with big five personality characteristics and cognitive ability. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(2), 326–336. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.86.2.326

- Lian, H., Ferris, D. L., Morrison, R., & Brown, D. J. (2014). Blame it on the supervisor or the subordinate? Reciprocal relations between abusive supervision and organizational deviance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 99(4), 651–664. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035498

- Little, T. D., Cunningham, W. A., Shahar, G., & Widaman, K. F. (2002). To parcel or not to parcel: Exploring the question, weighing the merits. Structural Equation Modeling, 9(2), 151–173. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1207/S15328007SEM0902_1

- Lyu, Y., & Zhu, H. (2019). The predictive effects of workplace ostracism on employee attitudes: A job embeddedness perspective. Journal of Business Ethics, 158(4), 1083–1095. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-017-3741-x

- Mao, Y., He, J., & Yang, D. (2020). The dark sides of engaging in creative processes: Coworker envy, workplace ostracism, and incivility. Asia Pacific Journal of Management. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-020-09707-z

- Mao, Y., Liu, Y., Jiang, C., & Zhang, I. D. (2018). Why am I ostracized and how would I react? – A review of workplace ostracism research. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 35(3), 745–767. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-017-9538-8

- Maslow, A. H. (1954). Motivation and personality. Harper and Row Publishers.

- May, V. (2011). Self, belonging and social change. Sociology, 45(3), 363–378. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038511399624

- Ng, T. W. H., & Feldman, D. C. (2008). The relationship of age to ten dimensions of job performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(2), 392–423. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.93.2.392

- O’Reilly, J., Robinson, S. L., Berdahl, J. L., & Banki, S. (2015). Is negative attention better than no attention? The comparative effects of ostracism and harassment at work. Organization Science, 26(3), 774–793. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2014.0900

- Organ, D. W. (1977). A reappraisal and reinterpretation of the satisfaction-causes-performance hypothesis. Academy of Management Review, 2(1), 46–53. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1977.4409162

- Ozcelik, H., & Barsade, S. G. (2018). No employee an island: Workplace loneliness and job performance. Academy of Management Journal, 61(6), 2343–2366. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2015.1066

- Peng, A. C., & Zeng, W. (2017). Workplace ostracism and deviant and helping behaviors: The moderating role of 360 degree feedback. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 38(6), 833–855. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2169

- Pickett, C. L., Gardner, W. L., & Knowles, M. (2004). Getting a cue: The need to belong and enhanced sensitivity to social cues. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 30(9), 1095–1107. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167203262085

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

- Quade, M. J., Greenbaum, R. L., & Petrenko, O. V. (2017). ‘I don't want to be near you, unless … ’: The interactive effect of unethical behavior and performance onto relationship conflict and workplace ostracism. Personnel Psychology, 70(3), 675–709. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/peps.12164

- Robinson, S. L., & Bennett, R. J. (1995). A typology of deviant workplace behaviors: A multidimensional scaling study. Academy of Management Journal, 38(2), 555–572. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5465/256693

- Robinson, S. L., & Bennett, R. J. (1997). Workplace deviance: Its definition, its manifestations, and its causes. In R. J. Lewicki, R. J. Bies, & B. H. Sheppard (Eds.), Research on negotiation in organizations (pp. 3–27). Elsevier Science/JAI Press.

- Robinson, S. L., Wang, W., & Kiewitz, C. (2014). Coworkers behaving badly: The impact of coworker deviant behavior upon individual employees. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 1(1), 123–143. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-031413-091225

- Rotundo, M., & Sackett, P. R. (2002). The relative importance of task, citizenship, and counterproductive performance to global ratings of job performance: A policy-capturing approach. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(1), 66–80. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.87.1.66

- Scott, K. L., & Duffy, M. K. (2015). Antecedents of workplace ostracism: New directions in research and intervention. Mistreatment in Organizations, 13, 137–165. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/S1479-355520150000013005

- Scott, K. L., Restubog, S. L. D., & Zagenczyk, T. J. (2013). A social exchange-based model of the antecedents of workplace exclusion. Journal of Applied Psychology, 98(1), 37–48. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/a0030135

- Son, J., & Ok, C. (2019). Hangover follows extroverts: Extraversion as a moderator in the curvilinear relationship between newcomers’ organizational tenure and job satisfaction. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 110, 72–88. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2018.11.002

- Tepper, B. J., Moss, S. E., & Duffy, M. K. (2011). Predictors of abusive supervision: Supervisor perceptions of deep-level dissimilarity, relationship conflict, and subordinate performance. Academy of Management Journal, 54(2), 279–294. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2011.60263085

- Thompson, D. A., & McRae, M. B. (2001). The need to belong: A theory of the therapeutic function of the black church tradition. Counseling and Values, 46(1), 40–53. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-007X.2001.tb00205.x

- Tian, Q. -T., Song, Y., Kwan, H. K., & Li, X. (2019). Workplace negative gossip and frontline employees’ proactive service performance. The Service Industries Journal, 39(1), 25–42. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02642069.2018.1435642

- Turnley, W. H., Bolino, M. C., Lester, S. W., & Bloodgood, J. M. (2003). The impact of psychological contract fulfillment on the performance of in-role and organizational citizenship behaviors. Journal of Management, 29(2), 187–206. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/014920630302900204

- Underwood, M. K., & Ehrenreich, S. E. (2014). Bullying may be fueled by the desperate need to belong. Theory into Practice, 53(4), 265–270. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00405841.2014.947217

- Wang, W., Mao, J., Wu, W., & Liu, J. (2012). Abusive supervision and workplace deviance: The mediating role of interactional justice and the moderating role of power distance. Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources, 50(1), 43–60. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-7941.2011.00004.x

- Williams, K. D. (2001). Ostracism: The power of silence. Guilford Press.

- Williams, K. D. (2007). Ostracism. Annual Review of Psychology, 58, 425–452. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085641

- Williams, L. J. (1988). Affective and nonaffective components of job satisfaction and organizational commitment as determinants of organizational citizenship and in-role behaviors [Unpublished doctoral dissertation], Indiana University, Bloomington.

- Williams, K. D., Cheung, C. K. T., & Choi, W. (2000). Cyberostracism: Effects of being ignored over the Internet. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79(5), 748–762. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.79.5.748

- Williams, L. J., & O’Boyle, E. H., Jr. (2008). Measurement models for linking latent variables and indicators: A review of human resource management research using parcels. Human Resource Management Review, 18(4), 233–242. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2008.07.002

- Williams, K. D., & Sommer, K. L. (1997). Social ostracism by coworkers: Does rejection lead to loafing or compensation? Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 23(7), 693–706. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167297237003

- Wu, L. Z., Ferris, D. L., Kwan, H. K., Chiang, F., Snape, E., & Liang, L. H. (2015). Breaking (or making) the silence: How goal interdependence and social skill predict being ostracized. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 131, 51–66. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2015.08.001

- Wu, C.-H., Kwan, H. K., Liu, J., & Lee, C. (2020). When and how impression management ameliorates workplace ostracism over time: Moderating effect of self-monitoring and mediating effect of popularity. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12328

- Wu, C.-H., Liu, J., Kwan, H. K., & Lee, C. (2016). Why and when workplace ostracism inhibits organizational citizenship behaviors: An organizational identification perspective. Journal of Applied Psychology, 101(3), 362–378. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000063

- Wu, W., Qu, Y., Zhang, Y., Hao, S., Tang, F., Zhao, N., & Si, H. (2019). Needs frustration makes me silent: Workplace ostracism and newcomers’ voice behavior. Journal of Management and Organization, 25(5), 635–652. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/jmo.2017.81

- Wu, L. Z., Wei, L., & Hui, C. (2011). Dispositional antecedents and consequences of workplace ostracism: An empirical examination. Frontiers of Business Research in China, 5(1), 23–44. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11782-011-0119-2

- Wu, L.-Z., Yim, F. H.-K., Kwan, H. K., & Zhang, X. (2012). Coping with workplace ostracism: The roles of ingratiation and political skill in employee psychological distress. Journal of Management Studies, 49(1), 178–199. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2011.01017.x

- Yang, J., & Treadway, D. C. (2018). A social influence interpretation of workplace ostracism and counterproductive work behavior. Journal of Business Ethics, 148(4), 879–891. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2912-x