Abstract

This work examines how intrusive advertising negatively impacts brand outcomes, and how this negativity is mitigated by mechanisms that support consumers feeling a greater sense of control. We contend that intrusive advertising leads to psychological reactance and consequently a loss of sense of agency, which results in negative brand outcomes. We examine how this is differentially mitigated by giving agency to consumers through skip, countdown, and choice mechanisms. Across a series of experiments, we show an option to skip advertisements enhances preference but leads to poorer memory for the advertised brand. Adding a countdown that precedes the skip function is similarly associated with enhanced preference but poorer memory. In contrast, we identify that the situations most positive for both preference and memory outcomes are where there is a countdown to the end of the advertisement with no skip functionality, or where consumers have choice over when to view advertisements.

Introduction

Online advertising continues to see significant year-on-year increases with an estimated total global spend of US$835.82 billion predicted by 2026 (Statista Citation2023). In line with this, intrusive advertising practices employed by marketers continues to grow (Riedel, Weeks, and Beatson Citation2018). Examples of common intrusive advertisements (ads) include banner ads and pop-up ads, which can often be forced upon consumers and may be obstructive (covering a part of the screen) and distracting to enhance noticeability. Intrusive advertising has been shown to result in a range of negative consequences (Jeon et al. Citation2019, Ying, Korneliussen, and Grønhaug Citation2009) including negative behavioral outcomes like advertising avoidance (Fransen et al. Citation2015) and decreased purchase intention (McCoy et al. Citation2008).

By forcing intrusive ads on consumers, where they are unable to exit and where attention is taken away from focal content (e.g. entertainment/informational content), psychological reactance (Brehm and Brehm Citation1981) likely results. Psychological reactance leads to emotions like annoyance or frustration, and in the context of online advertising, behaviors like ad avoidance and exiting websites (Riedel, Weeks, and Beatson Citation2018). Practical responses to these reactions have led advertising publishers and website developers to include a range of mechanisms that support greater consumer control, or perceptions of control, over intrusive ads. These include mechanisms such as skip buttons, where a skip button appears on the screen and an individual can exit out of the advertisement, countdowns, where there is a countdown to either the end of the advertisement or countdown to a skip option, advertisement viewing choices where the individual is offered the option to view ads at the beginning or throughout entertainment content, or various combinations of these functionalities. These approaches are common on popular online video platforms like YouTube and Vimeo, music platforms like Spotify, and across many mobile device and gaming applications.

In addition to psychological reactance, it is likely that a reduced sense of agency is experienced when the viewing activity or focal task is interrupted by intrusive advertising (Rodgers and Thorson Citation2000). Sense of agency refers to the feeling of control people have over their experiences and how they interact with the external world (Moore Citation2016). It has been described as key to satisfaction in user experience with technology and human-computer interactions (Coyle et al. Citation2012) in that people have a desire to be in charge of the systems and technologies they use and can react aversively when control is absent or lost (Shneiderman and Plaisant Citation2004). As such, when someone is viewing entertainment content for example, they likely have a sense of agency in that they have chosen that activity/content and can control their consumption experience (Sundar et al. Citation2015). When an ad is forced on them, they are likely to experience a reduced sense of agency, in that control is taken away (Riedel, Weeks, and Beatson Citation2018).

Limited research has empirically examined the effects on brands of using skip, countdown and choice mechanisms as a way of mitigating psychological reactance and reduced sense of agency caused by intrusive advertising, despite the common use of these mechanisms (cf. Jeon et al. Citation2019; McCoy et al. Citation2008). Importantly, research is yet to explore the interactive effects of when these mechanisms are used in conjunction (e.g. countdown to the appearance of a skip button vs countdown to the end of an advertisement), even though such combinations are now in widespread use by advertisers. Previous studies have predominantly focused on advertising intrusiveness itself, including its conceptualization (Riedel, Weeks, and Beatson Citation2018) and the effect intrusiveness has on non-brand outcomes such as attitudes toward the website (McCoy et al. Citation2008), purchase intentions of advertised products (Nam, Lee, and Jun Citation2019) and viewers’ coping responses to intrusive advertisements on social media platforms (Youn and Shin Citation2020). As such, this study aims to identify the effect of utilizing skip, countdown, and choice mechanisms, and importantly, combinations of these mechanisms, to provide a reduction in psychological reactance and an increase in sense of agency on outcomes including brand preference and memory for the advertised brand. These are important areas of research given the substantial amounts of money brands spend on online advertising to achieve brand-related objectives, and the vast numbers of consumers who encounter this type of advertising (Statista Citation2023).

Theoretical background

Intrusive advertising

Research suggests that with the increase in content available online, advertisements are being designed in a more intrusive manner to cut through the online message clutter (Ha and McCann Citation2008; Riedel, Weeks, and Beatson Citation2018; Shavitt, Vargas, and Lowry 2004). Intrusiveness has been defined as a ‘psychological consequence that occurs when an audience’s cognitive processes are interrupted’ (Li, Edwards, and Lee Citation2002, p. 39). Advertising intrusiveness presents a concern for platforms and brands alike, as intrusive ads 1) may cost a publisher money with consumers actively avoiding returning to websites which use these methods (Goldstein et al. Citation2014), 2) can lead consumers to develop negative perceptions (Shavitt, Vargas, and Lowrey Citation2004) and 3) can create circumstances where consumers avoid attending to the advertisement entirely (Edwards, Li, and Lee Citation2002). There have been several studies that have examined the conceptualisation and impact of intrusiveness of online advertisements. For example, Li, Edwards, and Lee (Citation2002) suggested that the perceived intrusiveness of an advertisement is due to online users being goal-orientated and the advertisement interrupting their ability to achieve their goal (Li, Edwards, and Lee Citation2002). Edwards, Li, and Lee (Citation2002) extended this finding by examining the effects of advertisement congruence, thought intensity and interruption duration on perceived advertising irritation and avoidance. Riedel, Weeks, and Beatson (Citation2018) furthered understanding of the conceptualization of advertising intrusiveness by developing a conceptual model of the drivers and consequences of advertising intrusiveness.

These studies provide helpful insight into understanding how and why an advertisement is perceived as intrusive. They do not however, examine the way negative effects of intrusive advertising might be mitigated through affording control to individuals through skip, countdown, and choice mechanisms (and various combinations of these mechanisms). Belanche, Flavián, and Pérez-Rueda (Citation2017) examined the use of skippable advertisements and specifically, how to increase the effectiveness of online video advertisements. The authors suggested that high-arousal stimuli increase the effectiveness of the advertisements in terms of the length of time they are viewed. Belanche, Flavián, and Pérez-Rueda (Citation2020) extended this by studying how exposure to skippable ads influences feelings of control and processing of the information in the advertisement. Finally, Jeon et al. (Citation2019) studied how the provision of temporal uncertainty through a timer (countdown) and a skip mechanism helped mitigate ad irritation and in turn, viewers’ likelihood of skipping the advertisement. The current study adds to this literature by investigating how skip, countdown and choice mechanisms, in isolation and in combination, mitigate the perceived intrusiveness of an advertisement and how this impacts preference for the advertised brand and memory for the advertising brand. By examining effects in terms of psychological reactance and loss of sense of agency, and the causal sequence of effects, it is one of the few studies that seeks to understand and explain underlying psychological processes.

Sense of agency

To examine the effects of intrusive advertising, previous research has largely been underpinned by theoretical concepts such as low attention processing (Santoso et al. Citation2020), interruption (Rejer and Jankowski Citation2017) and cognitive processes (Lewandowska and Jankowski Citation2017). While these concepts have contributed to furthering our understanding of advertising intrusiveness, they do not adequately explain how level of control over an intrusive advertisement may influence response. One theoretical concept that does provide such understanding is sense of agency. Sense of agency is typically described as when an individual experiences a feeling of having control over their experiences and how they interact with the external world (Moore Citation2016). As noted above, it is relevant in the current context, in that when people choose to view entertainment content, that likely feel a sense of control over that experience, with intrusive advertisements impeding on that sense of control (Riedel, Weeks, and Beatson Citation2018). Sense of agency is closely related but distinct from perceived behavioral control. Perceived behavioral control refers to the extent people feel they have the ability and resources to perform a behavior (Trafimow et al. Citation2002). In the current research, we believe intrusive advertising leads to a loss of sense of agency rather than loss of perceived behavioral control, since it impacts the sense of control over the experience and not necessarily the behavior of viewing content (Moore Citation2016).

When engaging with technology and technology-facilitated activities, such as with viewing online content, people are suggested to be more satisfied when they feel in control of the experience (Kim, Song, and Lee Citation2019) or have a sense of agency over the experience (Shneiderman and Plaisant Citation2004). At a consumer level, the impact of automation on perceived sense of agency might be considered in relation to everyday human-computer interactions, for example, with auto-correct typing functionality, song requests via voice assistants, or the consumption of personalized entertainment content (Moore Citation2016). When low levels of automation that align with the consumer’s goals make for a smoother experience, a feeling of agency is likely retained. However, when automation is too great, or when it produces an outcome inconsistent with the consumer’s goal (e.g. auto-correct updating words to non-intended ones), the feeling of agency may be reduced (Limerick, Coyle, and Moore Citation2014; Moore Citation2016). The same applies to intrusive advertising where automated ads are served in a way that interrupts a user’s chosen media experience and forces attention to content that does not align with their expected consumption goals. It is perhaps the case that when automation is inconsistent with consumer goals, it interrupts the implicit feeling of agency, and instead evokes a judgment that agency is lacking (or is attributed externally) that leads to negative reactions (Wen and Imamizu Citation2022). In the current research we contend that when viewing online content, consumers perceive a sense of agency in that they are in control, but that this is reduced when intrusive advertising occurs which can lead to negative brand outcomes. The potential for this loss of sense of agency is thus, one of the key foci of the current work.

Brand outcomes

Memory for the advertised brand

Memory effects stemming from advertising have been extensively investigated (e.g. Yoo Citation2008). Typically, it is found that greater or more frequent exposure to advertising increases memorability for the advertised message and brand (Pechmann and Stewart Citation1988). Memory effects however may develop very quickly even for advertising messages of short duration, and that longer exposures to very simple information like brand names or logos does not necessarily lead to significantly greater learning benefits than shorter exposures (Singh and Cole Citation1993; Varan et al. Citation2020). This is relevant to the current research given that motivations for making ads intrusive can often include increasing levels of brand exposure and subsequent memory (Pechmann and Stewart Citation1988). Offering consumers a skip button to exit early may help to mitigate reduced sense of agency, but also naturally decreases brand exposure time if the ad is exited early. Singh and Cole (Citation1993) work may suggest that this is not problematic however, as long as sufficient exposure has been achieved prior to exiting, although this is a matter for further investigation.

Where this becomes somewhat more complex, relates to the way consumers learn to ‘seek-out’ or anticipate skip functionality once they know it will be available in a series of online ads. Thus, although skip functionality may or may not be problematic for memory in terms of exposure duration, the anticipation and search for the skip button could reduce the extent of processing that the actual brand and advertised message receives. As explained in the work of MacInnis, Moorman, and Jaworski (Citation1991), consumers allocate cognitive resources to the goals they are motivated to achieve. If a consumer is motivated to look for a skip button, lesser resources will be available for processing brand information and the advertised message. This makes memory for the advertised brand an important outcome to examine in the current research, since the provision of skip functionality may be detrimental to memory.

Preference for the advertised brand

Preference for the advertised brand refers to a consumer’s willingness to choose the advertised brand over other brands, and has been the focus of a considerable amount of work in the marketing literature (e.g. Liu and Shankar Citation2015). It is important to consider preference in the current research as online advertising commonly has brand-related objectives, and preference is a predictor of purchase behavior (Chen and Chang Citation2008). Furthermore, preference is often impacted implicitly without conscious effort from the consumer (Bornstein and D’Agostino Citation1994), as would be the case when consumers’ direct minimal deliberate attention to an ad as a result of low-level processing and incidental advertising effects, which can be assumed to be the case with many types of online advertising where the ad is not the consumer’s focus (Shapiro, MacInnis, and Heckler Citation1997). Examination of these types of advertising effects is important since consumers may frequently not pay deliberate attention to online advertising, and in the case of intrusive advertising, may actively seek to avoid it (Riedel, Weeks, and Beatson Citation2018).

Past research has suggested that the presence of online ads can lead to negative website attitudes and decreased intentions to revisit a website (McCoy et al. Citation2017). It is possible that these negative perceptions could generalize to the brand, particularly if this is associated with a negative reaction resulting from a reduction in sense of agency. Thus, intrusive advertising might actually be counter-productive for brands if it negatively impacts preference for the brand. The provision of skip, countdown, or choice functionality, which may mitigate perceived loss of agency, could help to improve brand perceptions and hence preference, in that it is associated with a reinstatement (or reduced loss) of sense of agency. Thus, in contrast to past research that finds intrusive advertising leads to negative outcomes, the current research considers potential positive impacts on measures of brand preference when skip, countdown, and choice functionality is incorporated.

Differential impacts on brand outcomes due to psychological reactance

Previous literature suggests that intrusive advertising is likely to result in a psychological reactance (Brehm and Brehm Citation1981, Li et al. Citation2002), which may have negative effects for the brand. Theory around psychological reactance suggests that if consumers feel their behavioral freedom is threatened, a negative reaction may occur with the consumer being motivated to regain control (Brehm and Brehm Citation1981). Psychological reactance captures both negative cognitions and anger (anger, irritation, and annoyance; Youn and Kim Citation2019). When applying this to advertising intrusiveness, ads forced onto consumers lead to psychological reactance as a loss of control and freedom over task engagement is experienced. This negative psychological reactance remains until sense of agency and control over the task is regained.

As noted above, provision of skip functionality may help to mitigate this reduced sense of agency and psychological reactance the consumer experiences, leading to potentially positive impacts on preference for the associated advertised brand as consumers are experiencing a perceived form of control (Brehm and Brehm Citation1981). This skip functionality, however, might also result in lesser memory for the advertised brand than would otherwise occur, since consumers may be motivated to search or attend to the skip button reducing cognitive resources available for processing brand information (MacInnis, Moorman, and Jaworski Citation1991). Consumers are likely to look for the skip button to decrease their psychological reactance and regain their sense of agency (Brehm and Brehm Citation1981). It is proposed that these effects would be experienced regardless of the size of the intrusive advertisement as consumers would be utilizing the same resources to search for the skip button irrelevant of the size of the advertisement. This leads to the following hypotheses:

H1: Memory for an advertised brand will be poorer when consumers are provided with a ‘skip’ button that allows them to exit an intrusive ad early, as compared to when no ‘skip’ button is present. This will be apparent for brands presented in banner ads and also pop-up ads.

H2: Preference for an advertised brand will be improved when consumers are provided with a ‘skip’ button that allows them to exit an intrusive ad early, as compared to when no ‘skip’ button is present. This will be apparent for brands presented in banner ads and also pop-up ads.

One possibility for optimizing both memory and preference could be when consumers are provided with a countdown instead of a skip. Countdowns may work to signal to consumers that the reduced sense of agency is temporary (resulting in lesser negative reactance), while still supporting exposure and processing of brand information since a predictable countdown removes the urgency associated with the goal of clicking a skip button as quickly as possible (freeing up cognitive resources to support memory; MacInnis, Moorman, and Jaworski Citation1991). In thinking about combinations of these mechanisms, it is not immediately clear whether a countdown to a skip option (where a skip button appears only after a countdown) would be sufficient, or whether a countdown without an impending skip would be necessary (where a countdown is displayed to the end of the ad). Notably, for ads where there is simply a countdown to the end of the ad, there is no real time or control benefit for the consumer, but the countdown may nonetheless be positively perceived as it signals that the loss of control is temporary (Sundar Citation2008).

When considering memory, it is therefore proposed that a countdown provides consumers with a steady and predictable count toward the end of the ad that does not need to be intently monitored, and which does not have the urgency associated with anticipating, searching for, and clicking, as with a skip button. This means that a countdown enables cognitive resources to be left available for processing brand information in the ad, hence supporting memory for the brand (MacInnis, Moorman, and Jaworski Citation1991). We therefore expect that the countdown itself may help to draw attention toward the ad when presented in the context of ongoing focal activity (video), which might reasonably lead to improved memory for the brand. This makes a countdown beneficial to memory. Accordingly, we predict that in the absence of any skip function, intrusive ads that have a countdown present (counting down to the end of the ad) will be associated with stronger memory for the advertised brand than will ads that have no countdown present.

H3: For intrusive ads without skip functionality, memory for the advertised brand will be improved when consumers are provided with a countdown mechanism that runs until the end of the ad, compared to when there is no countdown.

In the presence of advertising with skip functionality, the addition of a countdown is not expected to improve memory performance due to the drain on cognitive resources that seeking to engage with the skip function creates, regardless of whether it is preceded by a countdown. In this instance the countdown leading to the skip may actually create greater anticipation and potentially frustration, reinforcing the drain on cognitive resources. We expect that when skip functionality is present, both with and without a countdown, memory performance will be similarly poor. Further, it can be expected that while ads that have skip functionality will lead to poorer memory (both with and without a countdown), those that have a countdown without skip will lead to comparatively better memory performance, and comparatively better performance than ads where there is no countdown, nor skip. This is because having a countdown present removes the need for consumers to actively search for the exit button or dedicate cognitive resources to anticipate the appearance of the exit button.

When considering preference, we expect a positive brand outcome when a countdown mechanism is present. This is because a countdown serves to signal to consumers that the reduced sense of agency is only temporary and places an explicit fixed time duration on it, reducing psychological reactance toward the ad and associated brand (Brehm and Brehm Citation1981). Importantly, we expect these positive effects will be observed even when the countdown runs until the end of the ad, without providing any real early exit benefit. This is as the countdown is providing a perceived level of control, signaling the loss of control is temporary (Sundar Citation2008), and in turn, reducing the psychological reactance and increasing one’s sense of agency. That is, in the absence of any skip functionality, ads displaying a countdown mechanism will be associated with greater preference for the advertised brand than will ads without a countdown mechanism, even when the countdown simply runs until the very end of the ad.

H4: For intrusive ads without skip functionality, preference for the advertised brand will be improved when consumers are provided with a countdown mechanism that runs until the end of the ad, compared to when there is no countdown.

Conversely, in the presence of skip functionality, we expect that providing the addition of a countdown (i.e. a countdown to the skip) will deliver little, if any, extra benefit to consumers since both the countdown and skip serve similar functions in mitigating the negativity and psychological reactance associated with intrusive ads. Importantly, if the provision of a countdown operates as we propose, mitigating the negativity associated psychological reactance with intrusive advertising by serving as a signal that any reduced sense of agency will be temporary, then preference for the advertised brand should be just as high in the countdown-only condition (no skip) as it is in either of the skip conditions (countdown-to-skip, no countdown-to-skip).

Underlying psychological mechanisms

In line with previous discussion, it is expected that when a consumer is exposed to an intrusive advertisement that this will lead to a psychological reactance. The psychological reactance results due to the individual feeling their freedom is threatened as they are no longer able to complete their original task and in turn, experience a negative reaction (Brehm and Brehm Citation1981). It is then proposed, in line with Cognitive Appraisal Theory that an individual cognitively appraises their emotional reaction (captured through psychological reactance) and attributes that reaction to a source or reason (Watson and Spence Citation2007). In this case, the consumer would experience the emotional reaction (psychological reactance) and attribute this to the intrusiveness of the advertisement and reduced sense of agency (Moore Citation2016). When a consumer experiences a lack of control or agency over their interactions with technology this leads to negative outcomes such as decreased satisfaction (Kim, Song, and Lee Citation2019). It is therefore expected that when a consumer does not have a sense of agency, in the absence of control mechanisms such as a countdown or control over when an advertisement is viewed, in line with H3-4, that this will lead to lower memory and preference for the advertised brand. As such, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H5: The relationship between control (countdown) over advertisements and preference for the brand will be mediated by psychological reactance, perceived intrusiveness, sense of agency, and brand memory, for conditions where control (choice) mechanisms are not provided.

Overview of studies

In Experiment 1, we examine how the presence of a skip button (which in reality might also be presented as an ‘Exit’ button or an ‘X’ or similar) affects memory (Experiment 1 A) and preference (Experiment 1B) for the advertised brand for both high and low intrusive advertisements (pop-up and banner ads respectively). In Experiment 2, we use a factorial design to cross the presence or absence of a countdown mechanism in intrusive advertising with the presence or absence of skip functionality. This is in line with the rationale regarding skip and countdown functionality mitigating the reduced sense of agency caused by intrusive advertising. Memory (Experiment 2 A) and preference (Experiment 2B) are examined. Finally, in Experiment 3, we examine how offering consumers a choice of whether to view ads at the beginning or throughout video content affects memory and preference. Specifically, choice functionality is crossed with countdown mechanism availability and we test both memory and preference in the one study. In this experiment the mediating mechanisms of psychological reactance and sense of agency are established, as well as that memory precedes preference in terms of brand outcomes.

Experiment 1A

Method

Design and participants

Experiment 1A employed a 2 (skip functionality: skip, no-skip) x 2 (ad type: banner, pop-up) between-subjects factorial design. Half the participants received exposure to banner ads while the other half received exposure to pop-up ads, with half of each of those groups having a skip button present, and the other half having no skip button. Subsequent memory for the advertised brand was measured. The sample consisted of 134 participants (53% female, Mage = 37.3 years, age range 19–73 years) who were US citizens recruited through Amazon Mechanical Turk (MTurk).

Stimulus development

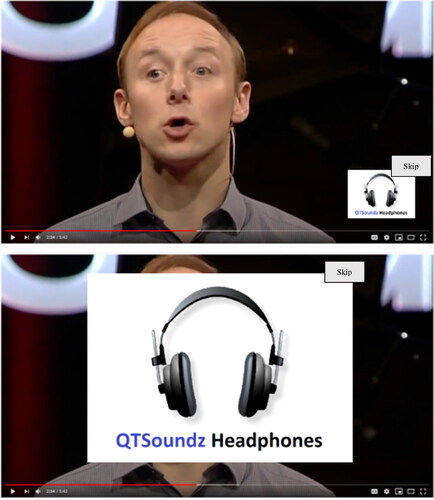

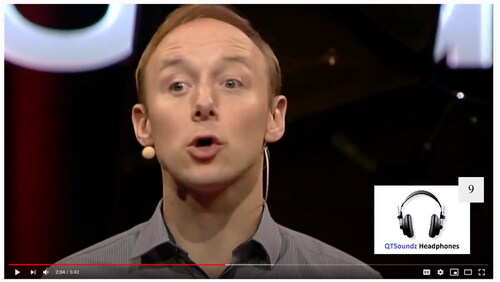

The experiment was instantiated using YouTube Studio as a video editing and curation platform, and participants watched videos as embedded YouTube clips. All participants viewed a six-minute segment from a video titled ‘Myth of the Rogue Shark’. The video was a TED Talk presented by a researcher discussing the politics of shark attacks and in particular, the three common myths about sharks. For the ad type manipulation, 12 ads were developed for display within the one video. Examples of these ads are found in Appendix A. The ad and video content were consistent across participants. The same ads were used as both banner and pop-up stimuli, with banner ads being presented as smaller ads in the lower right portion of the screen and pop-up ads being presented as larger ads obscuring a significant portion of the screen. In line with past work (Riedel, Weeks, and Beatson Citation2018) all ads were designed similarly and were intrusive (with pop-ups covering more of the screen and as such, being more intrusive than banner advertisements), incongruent to the shark topic of the video, and intrusive (confirmed through a manipulation check). Banner and pop-up ads were selected as these are some of the most simple yet prevalent forms of intrusive advertising utilized online. As such, consumers are used to these forms of advertising and engaging with them on an online platform (Riedel, Weeks, and Beatson Citation2018). Utilizing these forms of advertisements allowed for the controlling of external factors such as novelty of advertisement type and in turn, the specific investigation of the relationships of interest. Their design was based off real print ads taken from the popular press but with new fictitious brand names added. This ensured a sense of realism while limiting history effects, brand familiarity and pre-established brand attitudes and involvement. This technique has been employed previously by researchers such as Shapiro and Krishnan (Citation2001).

Procedure

Participants were randomly assigned to one of the four conditions. They were informed that they needed to watch a video clip in its entirety and would be asked questions at the end. Participants individually watched the video (approximately six minutes in length) which was interspersed with either the 12 developed banner ads or 12 pop-up ads (one every 30 seconds to ensure an even spread throughout the video). This approach was selected to ensure that both a wide range of advertising brands were shown and to reflect real world practice. The product categories of the advertisements such as crisps, headphones and jewelry, were selected to ensure a wide range of product categories were examined. All participants were exposed to the same 12 advertisements displayed in either banner or pop-up format (). Participants in the ‘skip’ conditions could close the ads once these appeared by clicking on a skip button. Through YouTube Analytics it was identified that 88% of the ads were skipped in total, suggesting that participants readily took advantage of the skip functionality. Participants in the ‘no-skip’ condition were unable to close the ads. Each ad remained on the screen for 10 seconds before disappearing. At the completion of the video, participants answered several questions about the video content (rogue sharks) and several distractor questions (e.g. math problems, favorite television character) for approximately one minute to provide a distraction interval between the content and test questions. Participants then responded to questions gauging memory for the advertised brand and answered a number of items that served as manipulation checks on advertising intrusiveness and ad incongruence. The manipulation check of incongruence was included since previous research has identified incongruence as a key driver of advertising intrusiveness (Riedel, Weeks, and Beatson Citation2018).

Measures

After viewing the video and completing distractor questions, participants were presented with the 12 product categories from the video on a computer screen. Each product category had two fictitious brand names listed beneath it, one that was included in the video and one that was not. Participants were instructed to select the brand name that was advertised in the video, hence testing their recognition memory. If they selected the correct brand name, this was considered a correct selection. This method is similar to previous marketing studies investigating memory (e.g. Yang et al. Citation2006).

To confirm that the ads were perceived as intrusive, participants also completed an advertising intrusiveness scale as developed by Li, Edwards, and Lee (Citation2002), composed of seven items using a 7-point Likert scale (distracting, disturbing, forced, interfering, intrusive, invasive, obtrusive; Cronbach’s alpha = .95). Incongruence of the ads to the video content was checked by displaying a picture from the video together with each ad and asking participants how closely matched they felt the video content and ad were. They indicated their response on a 7-point scale (poorly-matched to well-matched).

Results

The intrusiveness manipulation check confirmed the banner ads were perceived as moderately intrusive by participants, while pop-up ads were significantly more intrusive, t(131) = 5.59, p < .001, (Ms = 4.25 and 5.71 respectively). All ads were also perceived as moderately incongruent to the video’s content (Ms = 4.39 to 5.30). These manipulation check results were confirmed similarly in all subsequent experiments. It was also identified that there was no difference in attention check performance across pop-up and banner advertisements, t(110) = −.73, p = .469.

To minimize session primacy and recency effects, results for the first two and the last one ad presented to each participant were removed (Humphreys and Chalmers Citation2016; for consistency and rigor, this same approach was used for subsequent experiments). This is as previous research has identified the order in which stimuli is presented to participants and in particular, those stimuli presented first or last, can lead to differences in recall performance (Li Citation2010). Memory scores were based on the number of brands that participants were able to accurately identify from the experiment.

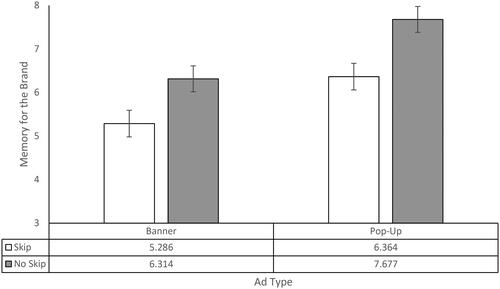

To test H1, a 2 × 2 between-subjects analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed. This revealed a significant main effect of skip functionality, F(1, 130) = 14.86, p <.001. In line with predictions, lesser memory for the brand was displayed by participants who had a skip option (M = 5.83) compared to those that had no skip option (M = 7.00). Ad type also produced a significant difference in memory, F(1, 130) = 16.13, p <.001, with pop-ups leading to greater memory for the brand (M = 7.02) compared to banner ads (M = 5.80). The interaction between skip functionality and ad type was however not significant, F(1, 130) = .22, p = .640 suggesting that skip functionality impacted both ad types similarly. This supports H1. The results are depicted graphically in . To rule out effects of age and gender, the main effects of these variables were examined, and it was identified that there were no significant differences in memory due to age, F(1, 130) = .82, p = .753, or gender, F(1, 130) = 1.68, p = .199.

Discussion

Experiment 1 A indicates that when consumers are presented with the option to skip ads, their memory for the advertised brand is poorer, compared to when they have no option to skip. This occurs for both banner ads and pop-up ads, although pop-up ads appear to produce higher levels of memory for advertised brands overall, possibly because of their larger intrusive nature. Some level of memory is evident for both ad types even when ads are skipped, which can be attributed to participants getting sufficient exposure to support later recognition (Singh and Cole Citation1993) even if that exposure is incidental or secondary to their main focus (Shapiro, MacInnis, and Heckler Citation1997). In Experiment 1B we consider effects on preference for the advertised brand.

Experiment 1B

Method

Design and participants

Experiment 1B employed a 2 (skip functionality: skip, no-skip) x 2 (ad type: banner, pop-up) between-subjects factorial design. Half the participants received exposure to banner ads while the other half received exposure to pop-up ads, with half of each of those groups having a skip button present, and the other half having no skip button. Subsequent preference for the advertised brand was measured. The sample consisted of 112 participants (46.4% female, Mage = 36.9 years, age range 21–68 years) who were US citizens recruited through Amazon Mechanical Turk (MTurk).

Measures

The materials and procedure for Experiment 1B were similar to Experiment 1 A, except instead of utilizing a measure of memory, we examined preference for the advertised brand. Preference for the advertised brand was measured by randomly presenting participants with 24 product category titles one at a time on screen, with 12 of these being the categories advertised in the video and 12 being distractor categories. No reference to the video or ads from the video was made. Under each product category two brand names were displayed side-by-side. Of the 12 categories advertised in the video, one of the answer options was the brand name used in the video and the other was not. For the 12 distractor pairs, none of the brands had appeared in the video and these were not included in the analysis. The purpose of these were to distract participants from simply remembering the advertisements included in the video and responding in turn. Participants were asked to select the brand that appealed to them most—specifically the one they felt would be the better brand, worthy of consideration if purchasing from the given category. If they selected the brand in the video, this was considered a ‘correct’ choice and an indication of brand preference for the advertised brand. As such, participants received a score out of nine where nine corresponded to a participant indicating preference for all advertisements shown in the video. In all cases, brand names were fictitious to avoid history effects. Each brand name was developed to have the same number of letters—an approach similar to other studies of brand preference in the literature (e.g. Florack and Scarabis Citation2006).

Results

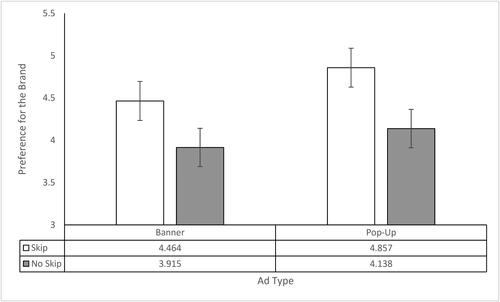

A 2 × 2 between-subjects analysis of variance (ANOVA) revealed a main effect of skip functionality, F(1, 108) = 8.85, p = .004. As expected, greater preference for the brand was observed for participants who had a skip option (M = 4.66) compared to those who had no skip option (M = 3.98). There was no effect of ad type, F(1, 108) = 2.42, p = .123, with participants who viewed banner ads (M = 4.14) displaying similar preference to those viewing pop-up ads (M = 4.50). The interaction between skip functionality and ad type was not significant, F(1, 108) = .02, p = .880, suggesting the same pattern of skip functionality effects was present for both banner and pop-up ads. This supports H2. Results are shown in .

Discussion

The results of Experiment 1B indicate that for intrusive ads that include a skip button, greater preference for the advertised brand is observed, as compared to when there is no skip button. A similar effect is seen for both banner ads and pop-up ads, which suggests that the agency effects stemming from the provision of a skip button apply across ads with both lower and higher degrees of intrusiveness. These results accord with H2. Thus, while intrusive ads may lead to a negative impact for the advertised brand, it would appear that this can be mitigated by the provision of skip functionality, at least in terms of brand preference. It is important to note here that an additional supplementary experiment was conducted to confirm that the memory effects were in fact due to people dedicating cognitive resources toward seeking-out and attending to a skip button rather than variation in exposure length. This experiment can be seen in Supplementary File 1.

The results of Experiments 1 A and 1B together can be seen as demonstrating that differential brand outcomes may result from the provision of a skip button. The presence of skip functionality appears to disadvantage memory (Experiment 1 A) but enhance preference for the advertised brand (Experiment 1B). Moreover, these effects generalize across both banner and pop-up ads. This presents something of a conundrum for brands since both memory and preference outcomes are commonly considered desirable. One mechanism that possibly resolves this issue is the use of a countdown mechanism in place of a skip option, and this is the focus of Experiments 2A and 2B.

Experiment 2A

Method

Experiment 2A employed a 2 (skip functionality: skip, no-skip) x 2 (countdown mechanism: present, absence) between-subjects factorial design. The skip manipulation was consistent with previous experiments. When available, the countdown involved a count display (see ) which counted down to either the appearance of a skip button (i.e. countdown-to-skip condition) or to the end of the ad (countdown no-skip condition). For the countdown instantiation where there was no skip, a count from 10 to 1 appeared at a rate of one count per second, in the lower right corner of the screen, superimposed on the ad (in the same location that the skip button appeared). For the countdown with a skip condition, a count from 5 to 1 appeared and then the skip button was present for the remaining 5 seconds. Banner ads consistent with the previous experiments served as the ad stimuli, and all other materials, measures, and procedures were similar to Experiment 1 A. The sample consisted of 121 participants (48.7% female, Mage = 37.8 years, age range 18–66 years), who were US citizens recruited through MTurk.

Results and discussion

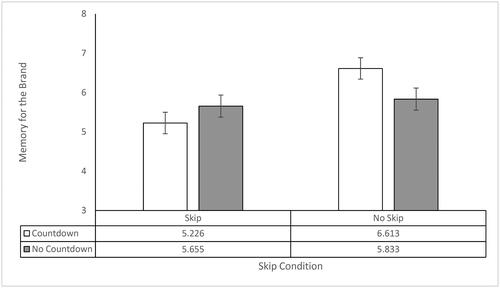

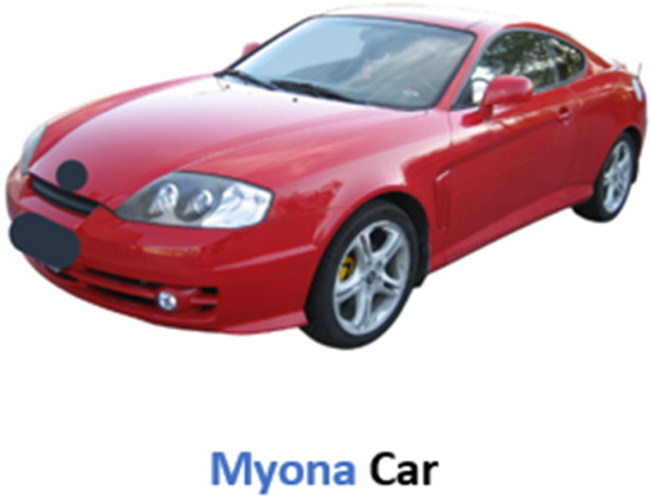

A 2 × 2 between-subjects ANOVA was conducted to test H3. Results showed that skip functionality had a significant effect on memory for the advertised brand, F(1, 117) = 8.04, p = .005, consistent with Experiment 1 A. Participants in the skip condition displayed poorer memory performance (M = 5.44) than participants in the no-skip condition (M = 6.22). There was no significant effect of countdown mechanism, F(1, 117) = .40, p = .527, but importantly, there was a significant interaction between skip functionality and countdown mechanism, F(1, 117) = 4.80, p = .031. This interaction is displayed in . Follow-up analyses revealed that, for the no-skip conditions, the presence of a countdown to the end of the ad led to greater memory for the advertised brand (M = 6.61) than when no countdown was present (M = 5.83), t(59) = 2.04, p = .047. This provides support for H3. For the conditions where skip functionality was present, there was no significant difference in memory performance for participants who saw ads with and without countdowns (M = 5.23 and M = 5.66 respectively), t(58) = −1.08, p = .286. Additional analysis further showed that memory for the advertised brand was significantly better for no-skip countdown ads, compared to ads that had skip with countdown, t(60) = 3.73, p < .001, and ads that had skip without countdown, t(58) = −2.42, p = .019. These results suggest that skip functionality was associated with poorer memory for the advertised brand, but the presence of a countdown mechanism was associated with improved memory. Notably, this improved memory performance occurred when the countdown was to the end of the ad, but not when it led to a skip button.

Experiment 2B

Method

Design and participants

Experiment 2B employed a 2 (skip functionality: skip, no-skip) x 2 (countdown mechanism: present, absence) between-subjects factorial design. Preference for the advertised brand was the outcome of interest and was measured similarly to Experiment 1B. The sample consisted of 135 participants (48% female, Mage = 34.7 years, age range 19–68 years).

Results and discussion

A 2 × 2 between-subjects ANOVA was conducted to test H4. As predicted, this revealed a significant main effect of skip functionality on preference for the advertised brand, F(1, 119) = 4.26, p = .041, with participants in the skip condition displaying significantly stronger preference (M = 5.61) than participants in the no-skip condition (M = 5.04). This aligns with the findings of Experiments 1B. There was no main effect of the countdown mechanism, F(1, 119) = .432, p = .512, but importantly, there was an interaction between skip functionality and the countdown mechanism, F(1, 119) = 4.094, p = .045. This can be seen in . In line with predictions, follow-up analysis revealed that in the no-skip conditions, the presence of a countdown was associated with stronger preference (M = 5.41) than when no countdown was available (M = 4.67), t(67) = 2.00, p = .049. This supports H4. In the skip conditions, there was no significant difference in preference between when there was a countdown (M = 5.417) and when there was no countdown (M = 5.79), t(51) = −.94, p = .354. Further analysis additionally showed that preference for the advertised brand was similarly high in the countdown no-skip condition as it was in the countdown-to-skip condition, t(59) = −.03, p = .976, and also in the no-countdown skip condition, t(64) = −1.11, p = .273. These results indicate that the use of a countdown is similarly valuable in supporting positive preference for the advertised brand as the use of skip functionality. Only when intrusive ads have no countdown mechanism available and no skip functionality available, is preference lower.

Discussion

The results of Experiments 2 A and 2B demonstrate that countdown mechanisms can serve to reduce the negative impacts of intrusive advertising on brand outcomes. Similar to skip functionality, countdowns may help mitigate a reduced sense of agency and associated psychological reactance that intrusive advertising creates. Experiment 2B showed that like Experiment 1B, skip functionality helped support enhanced preference toward the advertised brand, and that so too did the presence of a countdown mechanism. Experiment 2 A showed that like Experiment 1 A, skip functionality was associated with poorer memory for the advertised brand, but the presence of a countdown mechanism was associated with improved memory. Notably, this improved memory performance occurred when the countdown was to the end of the ad, but not when it led to a skip button. This is an important result, because this condition of presenting a countdown to the end of the ad (without skip) was the only condition to produce positive effects for both preference and memory outcomes. All other conditions differentially produced either positive preference outcomes with poorer memory outcomes (e.g. skip functionality with or without countdown) or poorer preference outcomes with favorable memory outcomes (e.g. no skip functionality, no countdown). Thus, while in practice advertisers commonly use skip functionality and countdown-to-skip functionality, our results suggest that only a countdown to the end of the ad (without skip) may lead to positive outcomes in terms of both brand preference and brand memory. Advertisers using other combinations may inadvertently be generating poor brand outcomes on at least one of these measures.

Experiment 3

Experiment 3 builds on the previous experiments with three key aims. First, we set out to extend our empirical investigation of mechanisms that afford greater consumer control, by studying whether a third approach of offering consumers choice over when to view advertisements helps to mitigate negative brand outcomes (i.e. an option to watch advertisements at the beginning of entertainment content, or throughout the entertainment content). We test this in conjunction with the use of countdowns (identified as providing the most positive overall brand outcomes in Experiment Two). Choice of when to view advertisements is an approach used by a number of entertainment platforms, for example Spotify, a popular music streaming platform and as such, its inclusion increases the external validity of the research. Second, in the previous experiments, the use of psychological reactance and sense of agency as underlying psychological mechanisms was theorized. In Experiment 3 we empirically test the entirety of this theorization through mediation analysis. Third, the research seeks to examine whether memory for the brand precedes preference as proposed in the previous studies and as such, is part of the serial mediation sequence. This allows for a more comprehensive understanding of the relationships examined in previous studies and specifically, the relationship between memory and preference.

Method

Design

Experiment Three employed a 2 (choice functionality: choice, no choice) x 2 (countdown mechanism: present, absence) between-subjects factorial design. The stimuli involved utilizing the same video as in previous experiments. Countdown was operationalized in the same way as in Experiment 2. Choice functionality was operationalized by providing consumers with the option of viewing ads at the beginning of the video or throughout (drawn from the ads used in the previous experiments). In the no choice condition, participants were randomized into either viewing ads at the beginning or throughout.

Measures

Intrusiveness was measured as in the previous experiments. Psychological reactance was measured consistent with Youn and Kim (Citation2019) utilizing six items and a 7-point Likert scale. Sense of Agency was measured utilizing an adapted version of Tapal et al. (Citation2017) scale which included seven items on a 7-point Likert scale. Memory and preference were measured similarly to the previous experiments, however, only two brands were studied. These two brands were either viewed at the beginning of the video (prior to it commencing), or were embedded within the video, together with an extra advertisement added prior to the two focal ads to help minimize primacy effects in testing, and an extra advertisement added after the two focal ads to help minimize recency effects in testing (hence when ads were viewed throughout the video content, participants saw four ads, with the first and final ads excluded from any analysis). The sample consisted of 113 participants (31% female, Mage = 36.9 years, age range 20–70 years), who were US citizens recruited through MTurk, paid US$1.20 for their time.

Results and discussion

First, to rule out issues related to multicollinearity, variance inflation scores were calculated. It was identified that these ranged from 1.07 to 1.78, all meeting the threshold of being below 5 (Akinwande, Dikko, and Samson Citation2015). Next, a 2 × 2 between-subjects ANOVA was conducted to examine H5. It was identified that no significant interaction was present between choice and countdown mechanisms on memory for the brand, F(1, 109) = 2.40, p = .124, or brand preference, F(1, 109) = .99, p = .321. This result suggests that providing a choice mechanism is just as effective as a countdown in terms of preference and memory benefits, and as such, brands can select to use either of these methods to achieve positive brand results.

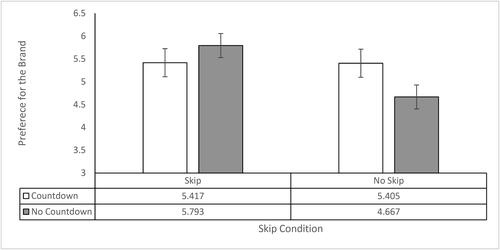

To address our predictions relating to the underlying mechanisms, a moderated serial mediation analysis was run (PROCESS Model 85; Hayes Citation2013) with 5000 resamples, with countdown mechanism as the independent variable, preference as the dependent variable, psychological reactance, intrusiveness, sense of agency and memory as the mediators, and choice as the moderator (as seen in ).

The PROCESS model analysis revealed that the interaction of choice and countdown had a direct effect on psychological reactance (B = .98, SE = .39, t(109) = 2.54, p =.004), psychological reactance had a direct effect on perceived intrusiveness (B = .93, SE = .12, t(109) = 7.58, p <.001), intrusiveness had a direct effect on sense of agency (B = −.16, SE = .07, t(109) = −2.30, p =.023), sense of agency had a direct effect on recall (B = .14, SE = .05, t(109) = 2.83, p =.006) and memory had a direct effect on preference (B = .46, SE = .12, t(109) = 3.93, p <.001). The index of moderated serial mediation was significant (index = −.01, SE = .01, 95 percent confidence interval [CI]: −.0414 to −.0001), thus the indirect effect of countdown mechanism on preference through psychological reactance, intrusiveness, sense of agency and memory, depends on the availability of the level of choice mechanism. Specifically, the mediated effect of countdown mechanism on preference through psychological reactance, intrusiveness, sense of agency and memory, is moderated when choice mechanism is absent (B =.008, SE = .010, 95 percent confidence interval [CI]: .0001 to .0309). However, a non-significant indirect effect was found for choice condition. This provides support for H5 and the overall conceptualization of the current study, with psychological reactance, intrusiveness and sense of agency explaining the results of the brand outcomes in Experiments 1 and 2.

General discussion

In the current work we forwarded the notion that intrusive advertising can produce negative psychological reactance because these ads reduce the sense of agency consumers feel when viewing digital content, and accordingly this negatively impacts brand outcomes. We proposed and empirically supported the idea that psychological reactance and reduced sense of agency can be mitigated by providing the option to skip ads (giving agency back to the consumer), by providing a countdown (signaling a time limit to the intrusion) or by providing control to consumers via choice (through offering an option of when advertisements are viewed) hence improving outcomes. Our results (see ) provide firm support for these ideas and identify that the use of a countdown to the end of an advertisement or a choice of when an advertisement is seen provides the most promising brand outcomes. Specifically, we evidenced that when consumers have the option to skip ads, their preference for the advertised brand is improved and this is apparent for banner ads that are deemed moderately intrusive, as well as pop-up ads that are more intrusive. We also showed that the skip option can lead to poorer memory outcomes, and we suggested that this is because consumers attend to the skip functionality rather than to ad content. The provision of a countdown mechanism produced similarly beneficial outcomes as the skip option in terms of preference and was also associated with improved memory performance. This was only when the countdown was presented in isolation (countdown to the end of the ad), not when combined with the skip function. The use of choice functionality, where a consumer could choose when they viewed the advertisement also led to positive outcomes but provided no additional benefit to the countdown to the end of the ad. As such, advertisers should use either a choice mechanism or a countdown with no skip functionality to decrease psychological reactance, increase sense of agency and in turn, produce more positive memory and preference outcomes for the advertising brand.

Table 1. Summary of experiment findings.

Thus, our work reveals that incorporating skip, countdown, and choice functionality to mitigate negative impacts of intrusive advertising can differentially affect brand outcomes linked to preference and memory, and that it is therefore critical for advertisers to understand how and why these mechanisms work. As such, advertisers can achieve optimal preference and memory brand outcomes by employing these mechanisms, which at the same time mitigate reduced sense of agency and feelings of psychological reactance.

Theoretical implications

At a theoretical level, our work helps to broaden discussion on sense of agency research beyond its usual domains of psychological well-being and job performance (Moore Citation2016), taking ideas about the impact of human-computer interaction on agency and applying these to intrusive advertising. It also highlights the importance of considering the effects of negative psychological reactance on brands that use intrusive advertising. Our research makes use of these ideas to reveal how skip, countdown, and choice functionality can help to mitigate the negative psychological reactance and reduced agency as a result of intrusive advertising, rather than focusing necessarily on reducing intrusiveness itself.

By using ideas about loss of sense of agency and examining ways to mitigate it, we open theoretical discussion for explaining other developments in advertising that provide control back to the consumer. For example, a number of entertainment platforms like YouTube and Spotify provide consumers with a basic free service where consumers are continually interrupted with ads, but also offer an option to pay for an ad-free subscription version of the service. This might naturally be conceptualized as these platforms using a punishment schedule to encourage subscription (Kelly, Kerr, and Drennan Citation2017) and may be perceived by consumers as an unnecessarily annoying attempt to manipulate people into paying for something they had considered free (Riedel, Weeks, and Beatson Citation2018). Accordingly, many consumers likely engage in advertising avoidance tactics or perhaps seek out questionable ways to access subscriptions (e.g. via peers) since they view the practice negatively. Using an explicit agency perspective however, this could be conceptualized differently. It might be assumed that subscription services are favorably viewed if consumers are encouraged to think about the agency of their media consumption experience that subscription services provide, rather than being considered a forced purchase to escape relentless advertisements.

Some gaming applications now also offer consumers an explicit level of control over advertising by giving gamers the option to earn tokens, unlock extra features, or restart games at an advanced level following a loss, by viewing extra advertisements. Here again, offering consumers choice and making the consumer control component explicit is likely to help instill a sense of agency. Future research that examines implicit versus explicit references to agency and control as part of mitigation approaches to intrusive advertising will help to show the extent to which this is beneficial to the consumer experience and how it affects the advertised brand.

Our work shows that not all approaches to mitigating loss of sense of agency operate similarly, and that they can have differential effects on brand outcomes. For example, while skip functionality can be assumed to work by giving agency back to the consumer, countdowns may simply serve as a signal that the loss of agency is temporary (Sundar Citation2008). Choice may afford greater agency to the consumer while not actually offering complete control. This is notable, since we found countdowns and choice were more effective in generating positive preference and memory outcomes, whereas skip functionality was positive for preference but detrimental to memory. Understanding how and when these mechanisms work is important since it provides guidance for advertisers on which is most appropriate to use given specific brand objectives. With online advertising it may be the anticipation of skip functionality that leads to reduced memory performance because of a drain on cognitive resources—something that warrants further research. Understanding this is important, since many advertisers may often aim to maximize length of exposure (including by delaying the presentation of skip options) when this might not actually be necessary.

Practical implications

For advertisers and brands, our work highlights that intrusive ads can lead to negative impacts on brand outcomes, but that this can be mitigated by affording some level of control or agency to the consumer. Rodgers, Ouyang, and Thorson (Citation2017) have previously described that the internet has given considerable control to consumers over advertising, but that developments across time have seen advertisers seek to re-intrude upon that control, for example with forced advertising. Our work provides evidence to show that giving control back to consumers can be valuable for brand outcomes, but that some approaches (e.g. countdowns) are more effective than others. By drawing on ideas about reduced sense of agency and understanding which mechanisms impact specific brand objectives, advertisers can be more strategic in their choices. For example, it is not uncommon to encounter intrusive ads that make use of skip functionality, and countdown-to-skip functionality, yet our research shows these approaches are not similarly beneficial. Somewhat counter-intuitively, the more optimal approaches are to provide a countdown without any skip functionality, even though the countdown itself serves no real time reduction benefit to consumers, or a choice of when advertisements are viewed.

In an effort to continue to reach consumers, and deliver on objectives highlighting brand preference and memory, advertisers should look to restructure how they communicate with consumers online. With consumers able to take ultimate control through ad-blocker technology, advertisers need to find a way not to alienate consumers to avoid this drastic step. Recognizing the importance of consumer control ensures advertisers understand the balance between control with achieving brand communication objectives. Advertisers should therefore provide a countdown button informing the consumer how long they have until the end of the advertisement in all online advertising. A number of current online platforms, such as Vimeo and Spotify, already take this approach in their freemium version where they have advertisements. Countdowns were found to be suitable in the current research, for both pop-up advertisements and banner advertisements. These countdowns appear to be more frequent on pop-up advertisements (homepage takeover or overlay advertisements as termed by Spotify), however our results indicate that they are suitable for banner advertisements as well. By signaling time for the intrusion through the countdown, a sense of agency is provided to the consumer. Advertisers should not offer this in conjunction with skip functions as commonly done, as our results indicate this lowers brand memory and brand preference.

The other option which ensures maintaining brand memory and brand preference, is providing the consumer with a choice about when they see advertisements online. With different subscription models available for a number of online platforms, such as Netflix, online providers can work with advertisers to ensure a suitable model which satisfies a broad range of consumers and maximizes return for all parties. When consumers sign up to an online platform, in addition to being allowed to select a subscription level, those consumers who do not want the premium (no advertisement offerings) level, can be asked when they want to see advertisements. This ensures consumers gain a sense of agency, online platforms benefit from advertising fees, and advertisers can maximize their brand memory and preferences with the consumer.

Limitations and future work

In the current work we outlined how intrusive advertising can interrupt a consumer’s media viewing experience, forcing attention to content that does not necessarily align with their entertainment, informational, or educational goals, hence leading to reduced sense of agency. However, not all consumption is necessarily ‘goal oriented’. Research such as Noguti and Waller (Citation2020) that considers whether similar levels of interruption and intrusiveness are perceived among consumers who are goal oriented in their viewing motivations (e.g. viewing a chosen program) versus those who are just casually browsing entertainment content (i.e. ‘surfing’) will help to reveal if a loss of sense of agency is similar across both types of consumers. In parallel, it can be useful to consider the nature of ad content. In our work, participants were exposed to ads that were unrelated to the video content, and negative impacts on brand preference were observed. If ad content is related/relevant (or behaviorally targeted), it may be that lesser interruption is perceived, and that negative impacts on the brand are less evident since loss of sense of agency is not as great. Similarly, if products featured in ads are of interest, or there is contextual compatibility, loss of sense of agency and perceived intrusiveness may be less. Additionally, in our studies, we showed that people reacted positively to a countdown when it ran to the end of an ad that lasted ten seconds. There may be a point at which countdowns for much longer ads elicit a negative response if the countdown signals the need to wait too long, and so future research that establishes the point at which this occurs would be valuable.

In our research we measured outcome variables immediately after a distraction task. Although the distraction task separated the responses from the exposure by approximately one minute, future studies could increase the length between exposure and measurement to identify whether results are consistent with a longer delay, since product choices are not always made soon after advertising exposure. Future research may also consider examining ads of longer duration, given that our results were all examined in the context of short ads (10 seconds). For longer ads, loss of sense of agency and negative psychological reactance may be greater, and skip/countdown mechanisms even more powerful. The experimental design of the current study also involved advertisements being displayed every 30 seconds. This was designed to ensure the advertisements were perceived as intrusive and also to reflect the frequency of advertisements in the real world however, future research should look to examine the effect of advertisements displayed less frequently and also on a more spontaneous schedule. Further, the behaviors being undertaken whilst the countdown is present need further examination. For instance, whether the individual is switching tabs or even viewing the content alone or group viewing may prove to influence the individuals memory.

Future research could also examine whether the type of the advertisement directly influences Sense of Agency and psychological reactance. The current study identified no impact on recall or preference for advertisement type (banner or pop-up), however, future investigation into the direct effect on Sense of Agency and psychological reactance may provide additional insights as to the impact of advertisement types. Future research that examines other mechanisms will additionally help to reveal additional ways the negative effects of intrusive ads might be mitigated, such as offering control over advertising exposure through subscription service options, or offering consumers rewards for viewing ads, such as with tokens in some gaming applications.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (18.3 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Akinwande, M. O., H. G. Dikko, and A. Samson. 2015. Variance inflation factors as a condition for the inclusion of suppressor variable(s) in regression analysis. Open Journal of Statistics 05, 07: 754–67.

- Belanche, D., C. Flavián, and A. Pérez-Rueda. 2017. Understanding interactive online advertising: Congruence and product involvement in highly and lowly arousing, skippable video ads. Journal of Interactive Marketing 37, no. 1: 75–88.

- Belanche, D., C. Flavián, and A. Pérez-Rueda. 2020. Brand recall of skippable vs non-skippable ads in YouTube: Readapting information and arousal to active audiences. Online Information Review 44, no. 3: 545–62.

- Bornstein, R.F, and P.R. D’Agostino. 1994. The attribution and discounting of perceptual fluency: Preliminary tests of a perceptual fluency/attributional model of the mere exposure effect. Social Cognition 12, no. 2: 103–28.

- Brehm, S.S, and J. Brehm. 1981. Psychological reactance: a theory of freedom and control. New York: Academic Press.

- Chen, C., and Y. Chang. 2008. Airline brand equity, brand preference, and purchase intentions—The moderating effects of switching costs. Journal of Air Transport Management 14, no. 1: 40–2.

- Coyle, D., J. Moore, P.O. Kristensson, P. Fletcher, and A. Blackwell. 2012. I did that! Measuring users’ experience of agency in their own actions. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 2025–2034.

- Edwards, S.M., H. Li, and J.-H. Lee. 2002. Forced exposure and psychological reactance: Antecedents and consequences of the perceived intrusiveness of pop-up ads. Journal of Advertising 31, no. 3: 83–95.

- Florack, A., and M. Scarabis. 2006. How advertising claims affect brand preferences and category–brand associations: the role of regulatory fit. Psychology and Marketing 23, no. 9: 741–55.

- Fransen, M.L., P.W. Verlegh, A. Kirmani, and E.G. Smit. 2015. A typology of consumer strategies for resisting advertising, and a review of mechanisms for countering them. International Journal of Advertising 34, no. 1: 6–16.

- Goldstein, D.G., S. Suri, R.P. McAfee, M. Ekstrand-Abueg, and F. Diaz. 2014. The economic and cognitive costs of annoying display advertisements. Journal of Marketing Research 51, no. 6: 742–52.

- Ha, L., and K. McCann. 2008. An integrated model of advertising clutter in offline and online media. International Journal of Advertising 27, no. 4: 569–92.

- Hayes, A.F. 2013. Mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: a regression-based approach. New York: Guilford Press.

- Humphreys, M.S, and K.A. Chalmers. 2016. Thinking about human memory. United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press.

- Jeon, Y. A., H. Son, A.D. Chung, and M.E. Drumwright. 2019. Temporal certainty and skippable in-stream commercials: Effects of ad length, timer, and skip-ad button on irritation and skipping behavior. Journal of Interactive Marketing 47, no. 1: 144–58.

- Kelly, L., G. Kerr, and J. Drennan. 2017. Between an ad block and a hard place: Advertising avoidance and the digital world. Digital advertising: Theory and Research. 243–255. New York: Routledge.

- Kim, H.Y., J.H. Song, and J.H. Lee. 2019. When are personalized promotions effective? The role of consumer control. International Journal of Advertising 38, no. 4: 628–47.

- Lewandowska, A., and J. Jankowski. 2017. The negative impact of visual web advertising content on cognitive process: towards quantitative evaluation. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies 108: 41–9.

- Li, C. 2010. Primacy effect or recency effect? A long-term memory test of super bowl commercials. Journal of Consumer Behaviour: An International Research Review 9, no.1: 32–44.

- Li, H., S.M. Edwards, and J.H. Lee. 2002. Measuring the intrusiveness of advertisements: Scale development and validation. Journal of Advertising 31, no. 2: 37–47.

- Limerick, H., D. Coyle, and J.W. Moore. 2014. The experience of agency in human-computer interactions: a review. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 8, Article 643: 643.

- Liu, Y., and V. Shankar. 2015. The dynamic impact of product-harm crises on brand preference and advertising effectiveness: an empirical analysis of the automobile industry. Management Science 61, no. 10: 2514–35.

- MacInnis, D.J., C. Moorman, and B.J. Jaworski. 1991. Enhancing and measuring consumers’ motivation, opportunity, and ability to process brand information from ads. Journal of Marketing 55, no.4: 32–53.

- McCoy, S., A. Everard, D.F. Galletta, and G.D. Moody. 2017. Here we go again! the impact of website ad repetition on recall, intrusiveness, attitudes, and site revisit intentions. Information & Management 54, no. 1: 14–24.

- McCoy, S., A. Everard, P. Polak, and D.F. Galletta. 2008. An experimental study of antecedents and consequences of online ad intrusiveness. International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction 24, no. 7: 672–99.

- Moore, J.W. 2016. What is the sense of agency and why does it matter? Frontiers in Psychology 7, Article 1272: 1272.

- Nam, Y., H.-S. Lee, and J.W. Jun. 2019. The influence of pre-roll advertising VOD via IPTV and mobile TV on consumers in Korea. International Journal of Advertising 38, no. 6: 867–85.

- Noguti, V., and D. Waller. 2020. Motivations to use social media: Effects on the perceived informativeness, entertainment, and intrusiveness of paid mobile advertising. Journal of Marketing Management 36, no. 15–16: 1527–55.

- Pechmann, C., and D.W. Stewart. 1988. Advertising repetition: A critical review of wearin and wearout. Current Issues and Research in Advertising 11, no. 1–2: 285–329.

- Rejer, I., and J. Jankowski. 2017. Brain activity patterns induced by interrupting the cognitive processes with online advertising. Cognitive Processing 18, no. 4: 419–30.

- Riedel, A.S., C.S. Weeks, and A.T. Beatson. 2018. Am I intruding? Developing a conceptualisation of advertising intrusiveness. Journal of Marketing Management 34, no. 9–10: 750–74.

- Rodgers, S., S. Ouyang, and E. Thorson. 2017. Revisiting the interactive advertising model (IAM) after 15 years. In Digital advertising: Theory and research, 1–18. New York: Routledge.

- Rodgers, S., and E. Thorson. 2000. The interactive advertising model: How users perceive and process online ads. Journal of Interactive Advertising 1, no. 1: 41–60.

- Santoso, I., M. Wright, G. Trinh, and M. Avis. 2020. Is digital advertising effective under conditions of low attention? Journal of Marketing Management 36, no. 17–18: 1707–30.

- Shapiro, S., and H.S. Krishnan. 2001. Memory-based measures for assessing advertising effects: a comparison of explicit and implicit memory effects. Journal of Advertising 30, no. 3: 1–13.

- Shapiro, S., D.J. MacInnis, and S.E. Heckler. 1997. The effects of incidental ad exposure on the formation of consideration sets. Journal of Consumer Research 24, no. 1: 94–104.

- Shavitt, S., P. Vargas, and P. Lowrey. 2004. Exploring the role of memory for self-selected ad experiences: Are some advertising media better liked than others? Psychology and Marketing 21, no. 12: 1011–32.

- Shneiderman, B., and C. Plaisant. 2004. Designing the user interface: Strategies for effective human-computer interaction. India: Pearson Education.

- Singh, S.N, and C.A. Cole. 1993. The effects of length, content, and repetition on television commercial effectiveness. Journal of Marketing Research 30, no. 1: 91–104.

- Statista. 2023. Digital advertising spending worldwide from 2021 to 2026. Statista, https://www.statista.com/statistics/237974/online-advertising-spending-worldwide/

- Sundar, S.S. 2008. The MAIN model: A heuristic approach to understanding technology effects on credibility. In Digital media, youth, and credibility, ed. M. Metzger and A. Flanagin, 73–100. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Sundar, S., J.T. Haiyan, F. Waddell, and Y. Huang. 2015. Toward a theory of interactive media effects (TIME) four models for explaining how interface features affect user psychology. Handbook of the Psychology of Communication Technology : 47–86.

- Tapal, A., E. Oren, R. Dar, and B. Eitam. 2017. The sense of agency scale: a measure of consciously perceived control over one’s mind, body, and the immediate environment. Frontiers in Psychology 8, Article 1552.

- Trafimow, D., P. Sheeran, M. Conner, and K. A. Finlay. 2002. Evidence that perceived behavioural control is a multidimensional construct: Perceived control and perceived difficulty. The British Journal of Social Psychology 41, no. Pt 1: 101–21.

- Varan, D., M. Nenycz-Thiel, R. Kennedy, and S. Bellman. 2020. The effects of commercial length on advertising impact: What short advertisements can and cannot deliver. Journal of Advertising Research 60, no. 1: 54–70.

- Watson, L., and M. T. Spence. 2007. Causes and consequences of emotions on consumer behaviour: A review and integrative cognitive appraisal theory. European Journal of Marketing 41, no.5/6: 487–511.

- Wen, W., and H. Imamizu. 2022. The sense of agency in perception, behaviour and human–machine interactions. Nature Reviews Psychology 1, no. 4: 211–22.

- Yang, M., D.R. Roskos-Ewoldsen, L. Dinu, and L.M. Arpan. 2006. The effectiveness of in-game advertising: Comparing college students’ explicit and implicit memory for brand names. Journal of Advertising 35, no. 4: 143–52.

- Ying, L., T. Korneliussen, and K. Grønhaug. 2009. The effect of ad value, ad placement and ad execution on the perceived intrusiveness of web advertisements. International Journal of Advertising 28, no. 4: 623–38.

- Yoo, C.Y. 2008. Unconscious processing of web advertising: Effects on implicit memory, attitude toward the brand, and consideration set. Journal of Interactive Marketing 22, no. 2: 2–18.

- Youn, S., and S. Kim. 2019. Understanding ad avoidance on Facebook: Antecedents and outcomes of psychological reactance. Computers in Human Behavior 98: 232–44.

- Youn, S., and W. Shin. 2020. Adolescents’ responses to social media newsfeed advertising: The interplay of persuasion knowledge, benefit-risk assessment, and ad scepticism in explaining information disclosure. International Journal of Advertising 39, no. 2: 213–31.

Appendix A

Example advertisements included in study

The images in these advertisements are examples of those included in the study and the images were sourced under CC with attribution to Piotr Siedlecki, John Loo and Cryostasis.