ABSTRACT

Children growing up with a parent with mental ill-health are a hidden and vulnerable group. Positioned at the intersection between adult and children services, and health and social care, these children fall between the gaps, rarely acknowledged in policy or practice. This is exacerbated when the young person is excluded under the auspices of patient confidentiality and age appropriateness. This article reports findings from research which captured young carers’ retrospective accounts of professional support when caring for a parent with mental illness. Participants in this research study described being ‘involved but not included’; they provided significant care to their parent and were relied on by professionals to provide support. However, they were simultaneously omitted from any discussion or understanding of the decisions made. This article explores the relevance of these accounts for current service provision. It concludes with recommendations for involving young carers in care planning and ensuring that young carers have their own needs assessed and acknowledged by professionals.

Introduction

Children growing up with a parent with mental ill-health are a vulnerable group with specific needs related to their family circumstances. Over the past 20 years research has consistently shown that this group of children and young people face adverse outcomes in terms of their own physical and mental health, educational attainment, social network and transition into adulthood (Aldridge & Becker, Citation2003; Blake-Holmes, Citation2019; Reupert & Maybery, Citation2016; Wepf & Leu, Citation2022). Such is the strength of this evidence that growing up with a parent with mental ill-health has been recognised as one of the Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACES) (Sherman & Hooker, Citation2018).

It is important to note that neither parents with mental ill-health nor their children are a homogeneous group. Not all parents will have their ability to parent compromised, nor will all children step into a caring role or be significantly affected by this (Boursnell, Citation2007). Recent research has begun to move beyond considering whether children will be adversely affected to explore why some children (and families) are impacted more than others (Janes et al., Citation2021), and what mechanisms could be put in place to support and safeguard both the children and their parents (Charles et al., Citation2016; Reupert & Maybery, Citation2016). It is also crucial to consider these families’ needs in the context of other adversities they might face such as poverty, social isolation, drug and alcohol misuse, instability and stigma.

We know that a significant number of children are growing up with a parent with mental ill-health (Reupert & Maybery, Citation2016). International research estimates that 23% of children grow up with a parent with mental ill-health (Reupert et al., Citation2022) and that 36% of patients receiving adult mental health services have a child under the age of 18 (Ruud, Citation2019). However, there are no consistent figures measuring the prevalence of parental mental illness within the UK (Cooklin, Citation2010; Yates & Gatsou, Citation2021). As such there has been a historic trend of such vulnerable young people being ‘hidden and ignored’ (James, Citation2017, p. 1), in both policy and practice.

Families’ involvement with professional services

Over the past 20 years there has been a growing political awareness of the needs of young carers (Joseph et al., Citation2020). This is reflected in the statutory duties written into UK social policy and legislation which seek to support vulnerable families and young people caring for family members. These range from Child in Need provisions under S17 Children Act 1989, to Carers assessments under both the Care Act 2014 and Children and Families Act 2014. However, research shows that despite these mechanisms, families living with parental mental ill health and facing adversity are often underrepresented in early help and preventative services (Lagdon et al., Citation2021).

Several studies have examined the perceptions of professionals working with families experiencing parental mental ill-health (Butler et al., Citation2021; Cooklin, Citation2010; Sherman & Hooker, Citation2018) and there are several recurrent themes. On an individual level, professionals and practitioners demonstrated a lack of awareness of the impact that mental ill-health has upon the family system, the increased stressors placed upon the parents and the potential adverse outcomes for the children. Those that were aware of these issues did not feel sufficiently confident to take a proactive approach in addressing them (Cooklin, Citation2010).

Health and social care teams generally work with individuals and may consider additional work with family members as not within their remit or that these needs will be met elsewhere (Cooklin, Citation2010). This is exacerbated by the long-standing separation of both child and adult services and health and social care services within the UK. The lack of integration between mental health and children’s services combined with the general individual patient focus of adult mental health services (which is often the first substantial point of contact for parents with mental ill-health) means that their status as parents, and the consequential impact on the children is often not recognised (Yates & Gatsou, Citation2021). In response to the Big Ask Survey conducted in 2021, the Children’s Commission commented on the ongoing (unmet) needs of children facing challenges and pressures as a result of parental mental ill-health, stating ‘too often we are still trying to “solve” the problems of one member of a family without seeing the family as a whole’ (Children’s Commissioner, Citation2023).

Family-focused approaches

Families where a parent has mental ill-health can present with complex and multi-faceted needs requiring a number of responses from different services (Davidson et al., Citation2023). There is convincing evidence that a family focused approach to support can be beneficial to the whole family, both as a unit and its individual members (McCarten et al., Citation2022).

Family focused practice is not a new concept with specific interventions implemented internationally (Reupert & Maybery, Citation2016). These approaches prioritise working with the family as a whole, rather than individual members – especially in cases where parents are experiencing mental ill-health. However, these approaches have generally represented small pockets of positive practice. Of the evaluative research that has examined family focused practice, there has been a clear demonstration of positive influence on both the parents and the children, including: enhanced parent/child relationships, reduction in relapse and hospital admission for the parent, and increased adaptive coping mechanisms and resilience for the children (Yates & Gatsou, Citation2021). Despite their documented benefits, family focused interventions appear difficult to implement and sustain due to a lack of organisational, policy and resource commitment (Allchin et al., Citation2022).

Despite the government’s commitment to the Think Family agenda of implementing family inclusive practice (McCarten et al., Citation2022) and the legal rights of vulnerable children under the United Nation Convention on the Rights of the Child, there remains scant multiagency collaboration and family focused service provision across the UK, which has been identified as a public concern (Butler et al., Citation2021; Yates & Gatsou, Citation2021). The past decade of austerity has exacerbated difficulties in both health and social care provision (widening the gap between adult and children’s services and favouring short-term interventions) at a time when economic hardship and welfare reform have left many families at increased vulnerability to hardship, crisis and breakdown (Barford & Gray, Citation2022). These difficulties have disproportionately impacted families living with adversity such as parental mental ill-health (Children’s Commissioner, Citation2023).

Methods

The study that this article draws from asked people to reflect on their childhoods growing up with a parent with mental ill-health, how they made sense of the experience and their role within it. This qualitative research consisted of biographical narrative interviews (Wengraf, Citation2001) with 20 individuals from across the United Kingdom. The study was not limited to specific mental illnesses or engagement with services. However, from their accounts, it appeared that all participants’ parents would have met the threshold required for secondary mental health services.

Adopting this biographical approach gave a valuable insight into how experiences impact on different individuals across the life course, how they are perceived and responded to and how they are viewed in retrospect. Key themes from this study and have been reported elsewhere. These include the coping mechanism of ‘acquiescence’ that was developed as a result of their experience through childhood (Blake-Holmes et al., Citation2023) and the impact that this has as the young person transitions in to adulthood and what this means within the family dynamic, as children, parents and siblings (Blake-Holmes, Citation2019) This article focuses specifically on relationship participants recalled with the professional health and social care services who were attending to their parents’ needs.

Ethics

Ethical approval was granted by the University Ethics Committee. Given the sensitive nature of the research careful consideration was given to the impact of the research on participants. The nature of the research and interview process was discussed with participants before they gave consent, and they were encouraged to consider what support they might require during and after the interview. Debrief sheets were provided to each participant with advice regarding support services tailored to their geographic location. A plan to report safeguarding concerns was also formulated and agreed by the participants as part of their consent. The decision was made not interview participants under the age of 16, due to the potential risk they would not have adequate support available to them to manage issues or distress caused by discussing current difficulties. As such it was determined that it would not be appropriate to ask children to reflect on current concerns and challenges without offering them an ongoing space in which to process these feelings and/or access support.

The decision to focus on participants aged 16 years and over was also made in line with McAdams and Adler (Citation2010) theory of narrative identity. McAdams proposed that a person’s narrative was constructed through an internalised and evolving story, and that this story continued to develop as the person moved through into their adult life. As a research method, using this autobiographical narrative lens allows us to analyse the participants’ narratives, taking into consideration their transitions, turning points and redemptive arcs. Interviewing adult about their experience of growing up with a parent with mental ill-health (rather than children) allowed us to capture how their perspective evolved across the life course. It was notable, for instance, that many participants viewed childhood experiences as a young carer in a different light once they themselves became parents. While it is recognised that the participants’ comments on services are not ‘current’, their experiences align closely with existing mental health service structures and approaches (as defined under the Mental Health Act 1983 and Care Programme Approach 1990) (NHS, Citation2021) and resonate with many of the themes reported in the contemporary literature.

Sample

Recruitment was conducted through the researcher speaking at public events, such as Mind, Young Carers’ conferences and through social media. The sample represented a diverse group as illustrated in . Their ages ranged between 19 and 54 years old with a mean age of 31. Four of the participants identified themselves as coming from a minority ethnic background. Four were siblings and six still lived with their parents. The gender imbalance in the participants (five male, fifteen female) was also reflected in the parent that they spoke about; five of the participants spoke about their fathers, twelve spoke of about their mothers and three spoke about both their parents as being mentally ill, however they tended to focus predominately on their memories of their mother. This representation of mothers requiring care and support is also reflected in young carers’ literature (James, Citation2017).

Table 1. Participants.

Interviews

Consistent with the biographical narrative method (Wengraf, Citation2001), participants were invited to tell their story from childhood to the present day with minimal interruption, questions or prompts. To understand the relationship between children growing up with a parent with mental ill-health and the relevant health and social care services, the question ‘what would have helped?’ was asked at the end of the biographical section of the interview – this enabled the identification of ‘missed opportunities’ for professionals to support the child. The interviews were completed in-person across the UK. They were audio recorded, lasted an average of 2.25 hours and were transcribed verbatim.

Analysis

The data was analysed using a thematic narrative method (Riessman, Citation2008) with regular opportunity to review the data analysis with the project team. Transcripts were coded and an index was created for each participant. Emerging themes around professional involvement were visually mapped for each participant. These were not selected to be statistically representative, but rather to develop theoretical exploration and argument. To retain a sense of the narrative, a biographical account was developed for each interview, isolating and ordering narrative episodes into a chronological timeline. Keeping the narratives separate, each interview was analysed individually, in an iterative process of expanding and collapsing thematic categories and narrative interpretation. Finally, coding and chronologies were combined to examine the way themes and narratives interacted within and across the cases. The findings reported here focus on participants’ experiences of professional services and support from health and social care.

Findings

When looking back at their childhood experiences (of growing up with a parent with mental ill-health) participants were generally critical of their involvement with services.

Within participants’ account of their experience of professional services, key themes emerged and will be explored in turn. These include missed opportunities, barriers to recognition and provision of care, and a sense of disconnect that was felt by the children in terms of their relationship to their parent’s needs and the professional intervention.

Overall, the interface (or perceived lack of interface) between health and social care services and families ran through all the interviews. The perception of the availability, responsiveness and professionalism of services was often interwoven with the participants’ understanding of their parent’s mental ill-health. This includes its severity, its societal construction and indeed a reflection of their own culpability and self-worth. By developing an understanding of the participants’ perspectives on service intervention, we explore the dichotomy that most of the participants described in terms of being involved but not included. Finally, we discuss the overwhelming consensus amongst the participants about what they felt was missing and what would have been helpful.

Children’s experiences of services – missed opportunities

Children who grow up with a parent with severe and enduring mental ill health encounter health and social care professionals in a range of settings during their life. As for most children, school is the primary place where they are observed by and interact with professionals. Given the complex needs of their parents, the participants within this study also had contact with professionals from secondary (or specialist) services such as community mental health teams, nursing staff within psychiatric hospitals, children’s services and child and adolescent mental health services. Despite extensive contact with professionals, many of the participants described feeling overlooked by services, and that there were missed opportunities to identify and respond to their specific needs.

Participants described how professionals such as doctors, nurses and social workers came to the house, yet rarely spoke to them. They described how their parent would book appointments during the school day or at a community clinic. This could have been perceived by professionals as their patient proactively engaging with their care and attempting to limit the impact of their mental ill-health on their children. However, for some participants this meant that they were neither seen nor considered and their parent could present a picture to professionals that did not reflect how things were at home. For two participants, child protection services were involved but once they withdrew, the support the child received also ceased and there was no mention of support continuing under S17 Children Act 1989. Similarly, mental health services tended to offer extensive support during periods of crisis but soon drifted away when the issue became complex or chronic. Holly described how this left her feeling abandoned and trapped:

You try so much to try and help them, but all of a sudden nothing works anymore because you’ve tried everything and that hasn’t helped, I think when it gets to that stage that everyone goes ‘Right I can’t deal with this’ and they have the option to walk away, I don’t. – Holly

Several participants described visiting their parents in psychiatric hospital and finding the environment intimidating. None of the participants recalled their parent’s treatment or condition being explained to them by nursing staff, nor was any family therapy offered. This was a missed opportunity to help the child understand of their parent’s mental health needs. This also meant that the child’s own needs were missed. In one powerful example, Jess described herself aged 13 taking the bus to visit her mother in hospital every day after school for three weeks. At no point did any professional speak to her for long enough to realise that during this time she was living alone, with no access to money for the electricity meter or food other than her school ‘dinner disc’.

In seeking to understand how these opportunities were missed in so many cases, it is important to consider it from the standpoint of the professional services and the child themselves. In terms of the services, a primary factor may have been the patient-centred ethos of mental health services. This derives from the individualist nature of the medical model of mental illness which is often the dominant ideology of health services (Glasby & Tew, Citation2015). The holistic assessment of the patient as a parent is often omitted, and consideration of the children is not viewed to be part of mental health services remit. This was reflected in participants’ description of themselves as invisible to services. A restricted focus on the patient, and the separation between health, social care and education can also lead to the assumption that the child’s needs are being addressed elsewhere. This is echoed in Jess’s sense of being surrounded by professional ‘bystanders’ who observed but did not intervene:

At what point was somebody going to do something like, it was serious bystanders like oh somebody else is probably dealing with this one leave it or I don’t know, absolutely bizarre. – Jess

Professionals can also be hesitant to look too closely at the child’s experience, reluctant to appear that they are reinforcing the stigma experienced by parents with mental ill-health or intruding on their privacy as a family. Equally they could be concerned about ‘opening a can of worms’ they feel ill-equipped to deal with. Nevertheless, while there may not necessarily be child protection concerns for children who grow up with a parent with mental ill health, there is often a need for additional support, a point made by Sophia:

There are certain things that were missing, that could have made it easier, I just don’t think you should be left to your own devices, because you’re not capable, you’re not competent as a parent, not to say you can’t have your kids, we were never in danger, nothing was ever going to happen to us, it was better than being in care I’m not even trying to say it wouldn’t be. I always knew that our mum loved us, but if they there was a little bit more help, a little bit more support around helping you do children things and being a child, I think that would have been helpful. – Sophia

This perception of support not being available continues to be highlighted in research, in a survey conducted by the Children’s Commissioner (Citation2016) over 80% of young carers did not receive support, with carer assessments being viewed as tick box exercises prioritising bureaucracy over the young person’s needs. However, in several narratives, service intervention was avoided, for fear that it would result in the family being separated. This was reflected in Jess’s sense that she ‘got away with’ hiding her highly risky home life by not ‘kicking up a fuss’ or being ‘naughty’. This fear of negative or punitive service intervention is identified in research examining the experience of parents with mental ill-health (Jeffery et al., Citation2013). This fear on the part of the parent can in turn reinforce the fear for the child.

Barriers to recognition

As identified above, participants reported that professionals did not routinely communicate with the child. However, the child themselves also experienced barriers to communicating with professionals. For instance, participants described not feeling able to fully express their experiences. Many recalled that, as children, they didn’t realise their situation wasn’t ‘normal’ until they began to spend time at their friends’ homes and began to compare them with their own. However, as the realisation of difference developed so did their awareness of associated stigma. Many participants discussed their need as children and adolescents to appear normal and to fit in with their peers. Many of the participants minimised the difficulties they had faced – ‘it’s not ideal but okay’ (Roman) and it was apparent they had done this for much of their childhood. They explained that they felt unable to confide in friends, as they believed peers would not be able to relate to their experiences, that it might be upsetting for others to hear and/or it might result in them being teased. They also kept their parent’s ill-health secret as a way of protecting their parent and felt that expressing their own needs and difficulties would cause their parents to feel guilty. They feared that this guilt would in turn exacerbate their parent’s distress and consequently make things harder for them. Typically, they positioned the needs of their parents above their own (Blake-Holmes et al., Citation2023).

Five participants described being prevented from speaking openly to services, because they never had the opportunity to talk without their parent present. Speaking to services about their own needs or contradicting the parent’s beliefs and/or demands would have been seen as a betrayal:

There’s that expectation from the ill person that you’re going to be their advocate and if you don’t get the result they want, they’re not happy and you haven’t shouted loud enough. – Terry

Provision of care

Ten of the participants grew up in a single parent household and provided the bulk of the care to their parent. Of the other ten who had another parent present, four spoke of the other parent (fathers) being predominately occupied by work with the major share of the emotional and physical care of the ‘ill’ parent resting with the participant. Equally, given the severity of their mental ill-health described by the participants, it was surprising to discover how many parents did not appear to have ongoing support from mental health services, a factor which could have influenced by the amount of ongoing care and support that the children provided.

The range of care tasks performed by the participants was extensive, from physical care to emotional containment and crisis management. At the point when services did enter the equation, older children, (those approximately nine years and above), took on tasks within the care plan, such as managing medication, monitoring mood and encouraging daily structure. Participants described feeling that there was an expectation from services that they would provide a care for their parent and that, at times, professionals directly requested them to perform tasks beyond their ability. For instance, Sophia describes leaving home and her younger brother Roman having to ‘step in’ and provide the care that she had done in the past.

The crisis team came in and they said to [Roman] it was his responsibility to make sure mum takes her drugs, my mum don’t like to take them and [Roman] has Asperger’s so you just told him it’s his responsibility to make sure she takes her drugs so basically he’s trying to force these drugs down her throat because she won’t take them and as far as he knows he’s going to get in trouble. – Sophia

Participants also described being used by professionals as a source of information about their parent. However, they felt that the flow of information was largely one way as they were rarely given information regarding their parent’s mental ill-health in return, nor were they invited to care plan meetings, or made privy to aftercare arrangements following their parent’s discharge from hospital. It seemed that on some occasions, this lack of inclusion and information was based on a notion that it would not be age-appropriate to involve the children in care discussions and decision-making. However, as Lucy described this concept of what is age-appropriate is skewed when the child is already directly involved with the ill-health and necessary care:

People think we won’t tell them because we don’t want to burden them when we were really burdened already, like we were burdened with all the responsibility of living alone with our mother, and I think people were like, they’re too young, we don’t want to involve them in mum’s treatment cos they’re young and they won’t understand, well you know, we don’t … but then we’re left with not understanding but having to deal with it. So, we were too young to be involved in my mum’s discharge planning meeting, but we weren’t too young to actually have to look after her all those years afterwards. So, the implications of all those decisions that were being made had such a profound effect on us, but these decisions were completely out of our control. – Lucy

This resulted in her feeling side-lined and unsupported throughout the process yet left with a great deal of responsibility:

I was seen as too young to be in be involved in her care … well I was too young to be involved in her care, but I wasn’t too young to be involved in looking after her when she got home … so I had all this responsibility but no control, I had no say in my mum’s treatment. – Robyn

Even as the children grew older, they continued to feel excluded from the care planning process. At 19 years old, Holly describes how this lack of information hindered her role as a carer and as such had a negative impact on her mother’s recovery:

I rang them a few times and said look I’m her carer, I need to know what’s going on and I need to know what you’ve said and what you’ve done so I can put things in place for her when she comes home. – Holly

This lack of inclusion also meant that professionals’ decisions were often made upon a snapshot assessment of the parent, and the expertise of the child who saw them around the clock was missed:

Because at the end of the day I am an expert on it, like maybe not because I’m his child, but because I’m the person who’s seen him for the past few weeks being … more and more out of control. And whether I’m 15 or 25, at what point do I get credibility for really knowing what’s going on and knowing what he needs. Because they want to ask me all these questions about his medication and they want to ask me all these questions about his behaviour, that like are quite complex stuff, and to be honest I didn’t know the medication stuff but I definitely knew all the other stuff. But then when they … they come to decision making I’m not allowed to say what’s best for him … I thought it was hypocritical that the crisis team was like asking all these questions but not actually listening. – Natalie

Discussion

Involved but not included

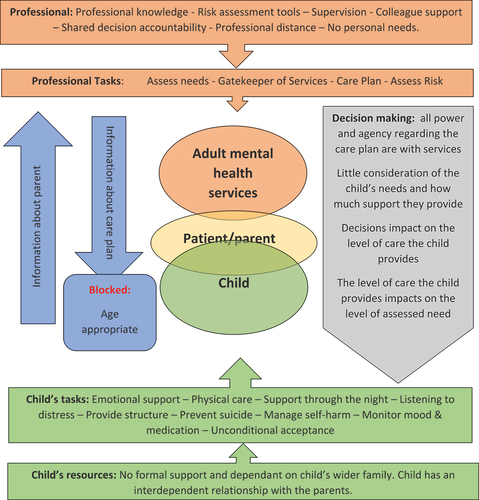

Participants’ accounts suggested that they were intrinsically involved yet paradoxically, not included by professionals. The model below conceptualises participants’ experiences of managing the interface between Drawing together the participants experiences of managing the interface between the care that they provided and the health and social care intervention available to their parents a model of involved but not included was created ().

Figure 1. ‘Involved but not included’ – the interface of the provision of care to a parent with mental ill health between the child and mental health services.

As seen in the centre of the model the child and the services both touch upon the parent, although not on each other, and the overlay between the child and the parent is much greater. The mental health professionals’ tasks focus on the assessment of need and provision of services, and within this role they are backed up by a wealth of professional knowledge and collegial support. In contrast, the child provides a wide range of support for the parent with very little formal support or understanding of how or why it is necessary. With the almost total overlay with the parent, the child also has little opportunity to create a sense of distance from the parent’s mental health needs and at times must subjugate their own needs, which would ordinarily be met by the parent.

Participants often described being asked to give information to services regarding their parent’s mental state, behaviour and/or medication concordance. Yet this flow of information was predominately one way as they were considered too young to be involved in discussions regarding their parent’s mental ill health and associated risks, or such conversations were kept within the bounds of patient confidentiality.

Finally, in terms of decision making, participants’ perceived that the power rested entirely with mental health professionals. They perceived little appreciation of the needs of the child, the amount of support they were providing and the impact the decision made about the parent would have had on the child. In several interviews the participants described their parents being discharged from services or declining services, however this was only made possible by the daily support that the parent was receiving from their child (or children).

This sense of being excluded from the care planning process and the issues discussed within the model, is not new or unique to children of parents with mental ill-health. Many other family members who take on the care role for spouses or adult children have described feeling unsupported and without the relevant knowledge to enable them to cope with their caring role in an effective and safe manner. Indeed, this tendency of mental health services to focus on the individual needs of the person with the ill-health is often seen as person-centred. However, difficulties present when is there little appreciation of their social relationships or environment. This is exacerbated by a lack of understanding of family focused practice and statutory and legislative processes which prioritise individual assessments and the protection of personal confidentiality (Glasby & Tew, Citation2015). The navigation of these processes and tension between the rights and needs of both the carer and the cared for is made more complex when the person holding the care role is under 18 years old.

What participants really wanted from services

When asked the final question of ‘what would have helped?’, there was a remarkable consensus across the group. The key message about what participants felt would have been helpful from services did not point towards dramatic interventions or complex (or expensive) resources. Instead, it was about a transformation of the relationship between services and children who grow up with a parent with a mental ill-health. As illustrated in , participants wanted to be included, noticed, acknowledged, respected and considered. They wanted to become visible and to be noticed by the professionals providing care and support to their parent. They wanted the care and the support they provided to be acknowledged both in terms of the impact that it had upon their lives and also the expertise that they held as a result. They wanted their families and themselves to be treated with respect, and hoped for a reduction of stigma which would enable them to speak more openly about their specific circumstances and reach out for support when required. They wanted their need for information to be considered and for it to be individualised to their own understanding not based on professional views of age-appropriateness. Finally, they called to be not just involved in the provision of care but truly included in their process with their voices and needs written into decisions made.

Conclusion

This paper explored the perception of people who grew up with a parent with mental ill health, their perceptions of their relationships with health and social care services and the support that they received. This was broken down into the themes of missed opportunities, barriers to recognition and provision of care.

Missed opportunities

There were several accounts of young people not being ‘seen’ by professions or only coming to the attention of professionals when their parent was in crisis. Participants perceived that opportunities were missed on several occasions to engage with them as a young person, to identify them as either a child in need or a young carer or to refer them for further support. As seen within the literature this could be because of the fragmented nature of services the focus on the individual service recipient as opposed to the whole family and a tacit assumption that someone else is working with the child.

Barriers to recognition

Identifying and addressing need is itself a complicated process. There are multiple reasons why families may not seek the help they require, through fear of intervention, minimising the need or not having a conscious awareness themselves both of the need or the support available. Time and resources need to be available to enable professionals to engage with the young person, to discuss the care they provide, the concerns that they hold and their own needs. It is only with this available to professionals that the full extent of the young person’s needs can be identified and addressed in a meaningful manner.

Provision of care

Often the care that children and young people provide to a parent with mental ill-health goes unseen, it can be difficult to quantify both in terms of the emotional effort and the potential harm that is prevented. The care may extend beyond the expectations afforded to the as children and as such their contributions are not heard within the care planning process.

The findings from the present study suggest that young people’s relationships with services may be an important mitigating factor in the extent to which they are adversely (or not) affected by being a carer for their parent. This suggests that where young people are appropriately involved and included, they are more likely to feel more positive about themselves and able to identify and access appropriate formal and informal support.

Strengths and limitations

As noted in the introduction children growing up with a parent with mental ill-health are not a homogeneous group. The participants in this study spoke about their own very personal experiences, the accounts are by their very nature subjective, this account may differ from the recollection of a professional involved. Equally while the study aimed to gain understanding of all experiences from positive to negative, it is recognised that many participants came with stories or trauma. While this of course means that the findings from this study are not generalisable, nor can they be validated across practice, they are still important and vital to hear. Their subjectivity does not diminish their significance.

The wide geographical and age range allowed for themes to present themselves as consistent across political and service delivery trends. It has also given us an insight into potential challenges that children may be facing which will inform our research approach with children in the future. To expand this piece of research it would be beneficial to include the voices of children and the team of professionals around them. Future research could involve families, both children and parents who are receiving mental health services and the professional involved in their care.

Acknowledgments

Blake-Holmes was the primary investigator and devised the model. Cook contributed expertise and specific theoretical perspective.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Kate Blake-Holmes

Kate Blake-Holmes is a Lecturer in Social Work, and Director of the Approved Mental Health Professional programme at the University of East Anglia. Kate is also a member of the Young Carers Alliance and of the International Research Collaborative for Change in Parent and Child Mental Health. Her research focuses on the needs of families with parental mental illness, the application of family focused practice in service design and the experiences of young carers. Kate is a qualified social worker and continues to practice for the Local Authority as an Approved Mental Health Professional.

Laura Cook

Laura Cook is a Lecturer in Social Work and Acting Director of the Centre for Research on Children and Families at the University of East Anglia (UEA), UK. Her research focuses on decision-making, resilience, retention and professional identity in social work. Laura has published a number of articles on sense-making in social work, the conduct of initial home visits in child welfare, and the impact of COVID-19 on social workers’ practice and wellbeing. Most recently, Laura has completed a British Academy-funded research project examining the link between professional identity and retention among experienced social workers. Laura is a qualified social worker and teaches across the qualifying and continuing professional development social work programmes at UEA.

References

- Aldridge, J., & Becker, S. (2003). Children caring for a parent with mental illness. The Policy Press.

- Allchin, B., Weimand, B., O’Hanlon, B., & Goodyear, M. (2022). A sustainability model for family-focused practice in adult mental health services. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.761889

- Barford, A., & Gray, M. (2022). The tattered state: Falling through the social safety net. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences, 137, 115–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2022.09.020

- Blake-Holmes, K. (2019). Young adult carers: Making choices and managing relationships with a parent with a mental illness. Advances in Mental Health, 18(3), 230–240.

- Blake-Holmes, K., Maynard, E., & Brandon, M. (2023). The impact of acquiescence: A model of coping developed from children of parents with mental illness. Advances in Mental Health, 21(3), 199–217. https://doi.org/10.1080/18387357.2023.2206037

- Boursnell, M. (2007). The silent parent: Developing knowledge about the experiences of parents with mental illness. Child Care in Practice, 13(3), 251–260. https://doi.org/10.1080/13575270701353630

- Butler, J., Gregg, L., Calam, R., & Wittkowski, A. (2021). Exploring staff implementation of a self-directed parenting intervention for parents with mental health difficulties. Community Mental Health Journal, 57(2), 247–261. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-020-00642-3

- Charles, G., Reupert, A., & Maybery, D. (2016). Families where a parent have a mental illness, a service development strategy. Victoria, 37(2), 95–97. https://doi.org/10.1080/0145935X.2016.1104032

- Children’s Commissioner. (2016). Young carers, the support provided to young carers in England. Children’s Commissioner for England.

- Children’s Commissioner. (2023). Family and mental health. Retrieved February 8, 2024, from https://www.childrenscommissioner.gov.uk/blog/mental-health-and-family/

- Cooklin, A. (2010). “Living upside down”: Being a young carer of a parent with mental illness. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment, 16(2), 141–146. https://doi.org/10.1192/apt.bp.108.006247

- Davidson, G., Allchin, B., Blake-Holmes, K., Grant, A., Langdon, S., McCarten, C., Maybery, D., Nicholson, J., Rupert, A., & Chen, Q.-W. (2023). Supporting service recipients to navigate complex service systems: An interdisciplinary scoping review. Health & Social Care in the Community, 2023, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1155/2023/8250781

- Glasby, J., & Tew, J. (2015). Mental health policy and practice (3rd ed.). Palgrave.

- James, E. (2017). Still Hidden, Still Ignored. Who cares for young carers. Barnados.

- Janes, E., Forrester, D., Reed, H., & Melendez-Torres, G. (2021). Young carers, mental health and psychosocial wellbeing: A realist synthesis. Child: Care, Health and Development, 48(2), 190–202. https://doi.org/10.1111/cch.12924

- Jeffery, D., Clement, S., Corker, E., Howard, M., Murray, J., & Thornicroft, G. (2013). Discrimination in relation to parenthood reported by community psychiatric services users in the UK: A framework analysis. BMC Psychiatry, 13(120), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-13-120

- Joseph, S., Sempik, J., Leu, A., & Becker, S. (2020). Young carers research, practice and policy: An overview and critical perspective of possible future directions. Adolescent Research Review, 5(1), 77–89. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40894-019-00119-9

- Lagdon, S., Grant, A., Davidson, G., Devaney, J., Donaghy, M., Duffy, J., Galway, K., & McCartan, C. (2021). Families with parental mental health problems: A systematic narrative review of family-focused practice. Child Abuse Review, 30(5), 400–421. https://doi.org/10.1002/car.2706

- McAdams, D., & Adler, M. (2010). Autobiographical memory and the construction of a narrative identity: Theory, research, and clinical implications. In J. E. Maddux & J. P. Tangney (Eds.), Social psychological foundations of clinical psychology (pp. 36–50). The Guilford Press.

- McCarten, C., Davidson, G., Donaghy, M., Grant, A., Bunting, L., Deveney, J., & Duffy, J. (2022). Are we starting to ‘think family’? Evidence from a case file audit of parents and children supported by mental health, addictions and children’s services. Child Abuse Review, 31(3), 1–7.

- NHS. (2021). Care for people with mental health problems (Care programme approach). Retrieved February 11, 2024, from https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/social-care-and-support-guide/help-from-social-services-and-charities/care-for-people-with-mental-health-problems-care-programme-approach/

- Reupert, A., & Maybery, D. (2016). What do we know about families where parents have a mental illness? A systematic review. Child and Youth Services, 37(2), 98–111. https://doi.org/10.1080/0145935X.2016.1104037

- Reupert, A., Bee, P., Hosman, C., van Doesum, K., Drost, L. M., Falkov, A., Foster, K., Gatsou, L., Gladstone, B., Goodyear, M., Grant, A., Grove, C., Isobel, S., Kowalenko, N., Lauritzen, C., Maybery, D., Mordoch, E., Nicholson, J., Reedtz, C., … Ruud, T. (2022). Editorial perspective: Prato research collaborative for change in parent and child mental health - principles and recommendations for working with children and parents living with parental mental illness. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 63(3), 350–353. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.13521

- Riessman, C. (2008). Narrative methods for the human sciences. Sage.

- Ruud, T., Maybery, D., Reupert, A., Weimand, B., Foster, K., Grant, A., Skogøy, B. E., & Ose, S. (2019). Adult mental health outpatients who have minor children: Prevalence of parents, referrals of their children and patient characteristics. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 10, 163.

- Sherman, M., & Hooker, S. (2018). Supporting families managing a parental mental illness: Challenges and resources. International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine, 53(5), 361–370. https://doi.org/10.1177/0091217418791444

- Wengraf, T. (2001). Qualitative research interviewing: Biographical narrative and semi structured methods. Sage.

- Wepf, H., & Leu, A. (2022). Well-being and perceived stress of adolescent young carers: A cross-sectional comparative study. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 31(4), 934–948. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-021-02097-w

- Yates, S., & Gatsou, L. (2021). Undertaking family-focused interventions when a parent has a mental illness - possibilities and challenges. Practice, 33(2), 103–118. https://doi.org/10.1080/09503153.2020.1760814