ABSTRACT

This study employs Walter Benjamin’s aura framework as a theoretical lens to look at religious consumption in virtual worlds, via a case study of the London megachurch Kingsway International Christian Centre. Findings suggest inter-personal authenticity contributes to authenticity in online religious consumption and emphasise the need to re-sacralise space and de-sanctify time to help congregant-audiences access sacred experiences. We also highlight the importance of re-mooring traditions and transformable rituals in replicating essential components of real-world worship gatherings through media and technologies. Proposing that the digital imbues its own aura, we develop the concept of ‘digital aura’, characterised by hypermediacy in media usage and remediation, which leads to the refashioning of certain practices and, ultimately, changes the way that audience members engage in ritual events.

Introduction

Despite increasing secularisation in Western Europe, over 84% of the world’s population still holds to a meaningful religious commitment (Pew Research Center, Citation2012), and significant majorities of the population in many Asian and African countries identify religion as the single most important influence upon their everyday lives. Religion remains a key determinant of behaviour (LaBarbera, Citation1987) for both societies (Hyodo et al., Citation2021) and individuals (Jung, Citation1960). Yet still, regrettably, ‘Religion and business are often seen as inhabiting separate social spheres’ (Yip & Ainsworth, Citation2015, p. 237). Phenomena, concepts and language from religion and spirituality have clearly influenced business practices and marketing thinking (cf. Hyodo et al., Citation2021; Yip & Ainsworth, Citation2020), almost a century since Weber (Citation1930) addressed the impact of religious affiliation on business decisions, behaviours and outcomes. At the end of the last century, research on religion in the marketing context (Belk et al., Citation1989; Hirschman, Citation1983) addressed negative associations between religiosity and materialism, trendiness, and hedonism (Hirschman, Citation1981; McDaniel & Burnett, Citation1990; Sood & Nasu, Citation1995), and considered how religious affiliation can shape consumer behaviour (Delener, Citation1990).

More recently, religion has made a valuable contribution to consumption studies (Higgins et al., Citation2019; Husemann et al., Citation2019), focussing both on consumers’ attitudes (Fam et al., Citation2004) and intentions (Skarmeas & Shabbir, Citation2011). Studies of the mediatisation of faith and religious practices started to emerge in the early 2000s (cf. Bratosin, Citation2020; Campbell, Citation2005; Hjarvard, Citation2011; Martino, Citation2020; Przywara et al., Citation2021). Hjarvard’s contributions to this field (Citation2008, Citation2011) highlight how interactive media services provide useful platforms for expressing and circulating beliefs, demonstrating how media uses pre-existing religious practices as source material. For Hjarvard (Citation2011), furthermore, the media are no longer separated from society, but have become integrated and intertwined into everyday life, taking over some of the historic cultural and social functions of religious institutions. Appreciating that the media are both independent from, and also integrated into, other social functions opens transformative new opportunities for religious institutions. Recent interest in the social (sometimes labelled ‘new-age’) mediatisation of religion (Al-Zaman, Citation2022) has demonstrated that the influence of different social media platforms on different religions is neither homogenous nor consistent (Frissen et al., Citation2017; Hazim & Musdholifah, Citation2021; Weng, Citation2019), inviting further empirical studies in this field (Al-Zaman, Citation2022).

In line with recent efforts to connect religion and marketing studies (Jafari & Süerdem, Citation2012; Karatas & Sandikci, Citation2013; Sandicki & Ger, Citation2010; Yip & Ainsworth, Citation2020), this paper considers the consumption of the sacred during the unsettled period in 2020 when physical sacred space was inaccessible due to the COVID-19 pandemic. During the lockdowns, religious institutions developed new practices to enable their congregants to continue their traditional religious observances (Baker et al., Citation2020; Bryson et al., Citation2020). Our research context also enables us to contribute to studies of mediatisation of religion, considering the social process through which religious institutions become, at least to some extent, dependent on the logic of the media (Hjarvard, Citation2011). Our study adds to existing research through its emphasis on mediatisation through social media (cf. Giaxoglou & Döveling, Citation2018), making an important empirical contribution here. We employ Walter Benjamin’s aura framework (Citation1968) as a theoretical lens to help us consider how faith communities create an auratic experiences for their audiences and understand the ways in which congregants engage with megachurches in digital space. The core conceptual components of Benjamin’s framework – authenticity, ritual, tradition, space, and time – highlight the obstacles technological reproduction and reproductive media pose to creating unique, authentic experiences, but also identify the potential for innovative practices to offer modern consumers new ways of engaging with a subject or brand. By employing Benjamin’s aura framework (Citation1968), we explore the digitisation of the churches’ messaging and their propagation of ‘aura’ on digital or social platforms, seeking to answer the following research questions:

How does the digitisation of the churches’ message affect their tradition?

How do the churches’ ritual practices change in an online environment?

What are the impacts of social media on the churches’ conceptualisation of ‘sacred space’?

How does the use of social media platforms impact the uniqueness of ritual time?

How does reliance upon reproduced-digitalised content change the notion of the authenticity of churches?

Megachurches (very large Christian congregations of over 2,000 attenders) are notable for their continuing growth in the face of declining religious observance in the West (Martin et al., Citation2011; Sircar & Rowley, Citation2020); their increasing digital engagement (Hackett, Citation2009; Kim, Citation2007); and their espoused concern for creating authentic experience – though their real commitment to the latter has been questioned (Drane, Citation2000). Digital-first delivery further challenges the way in which megachurches engage with their audience, since the transformational experiences they seek to offer, as well as the emotional and spiritual connections they promote, are traditionally bounded in physical space and time. However, many churches are finding that online worship can be engaging and create genuine spiritual experiences too (Bryson et al., Citation2020; Davies, Citation2021). We address these interests through a case study of Kingsway International Christian Centre (KICC), a British-African megachurch which aspires to be a ‘church without walls’ with members all around the world. KICC hosts approximately 450–500 online experiences a year, including worship services, inspirational experiences and special interest group events, alongside its traditional in-person gatherings. Our digital longitudinal ethnography (Canavan, Citation2021; Kozinets, Citation2015) collected various types of data, including participant observations, memos, and visual data from KICC’s website, YouTube, Instagram, and Facebook feeds from 2017 to 2021.

Drawing upon this data and adopting the approach of building theories from case studies (Eisenhardt, Citation1989), our paper proposes the construction of ‘digital aura’. We develop this concept from Benjamin’s ideas (Citation1968), which encapsulate the authenticity, ritual, and tradition of the offline religious experience, and we expand the common approach to notions of space and time in religious consumption. Our newly constructed digital aura framework focusses upon space and its potential for re-sacralisation to challenge the view of media as merely ‘profane’ space. Noting the intertwining of space and time, we also propose that an expansion of sanctified time is crucial for effective online engagement with worship. From this re-examination, we then propose that digital aura is constructed by a re-mooring of tradition, transformable rituals and a unique regime of authenticity. It is important to note that, while digital aura has its own value and characteristics, it is created from the original aura and should be seen as supplementing rather than replacing physical co-presence with fellow worshippers in a traditional church building. Among our theoretical contributions, we expand Benjamin’s reference to media (Citation1968) to also address new digital forms (including livestreaming and real-time interaction) that might exhibit digital aura. We also found that the pandemic, despite its undeniable disruptions, encouraged religious institutions to employ the strategy of ‘hypermediacy’, the explicit integration of multiple forms of media in delivering a feeling of fullness of experience which audiences can take as reality. Such harmonisation in the use of various media forms also constructs the ‘remediative’ nature of digital aura, which only occurs when a combination of new and old practices leads to the refashioning of certain practices and, ultimately, changes in the way that audience members engage in ritual events. In so doing, our findings contribute new insight into the social mediatisation of religion, expand current studies by examining the roles of media in extending human interaction beyond immediate time and space, and explain how the logic of the media can be accommodated by religious institutions and practices.

Aura: a theoretical framework

‘Benjaminian aura’ (Benjamin, Citation1931, Citation1968) remains one of the most commonly invoked concepts in the field of media research (Bolter et al., Citation2006). Benjamin uses the analogy of aura in nature to suggest the sense of distance needed in appreciating the beauty of the arts. This quality of ‘the unique phenomenon of a distance, however near it may be’ (Benjamin, Citation1931, p. 222) has become central to Benjamin’s later writings on aura, which he later conceives of as ‘the creation of a psychological inapproachability’ (Benjamin, Citation2008, p. 14). For Benjamin, the distance-no-matter-how-near of aura is hampered by technological reproduction, since technology creates a sense of proximity ‘no matter how far the subject really is from the physical location’ (Bolter et al., Citation2006, p. 28). Benjamin was concerned that photography, film and other ‘reproductive’ media diminished the magical aura that belonged only to original artefacts, fearing that the substitution of artificial objects and experiences for the real would provoke a less authentic experience of the sacred and, consequently, ‘life itself would become less meaningful under these circumstances’ (Belk, Citation1996, p. 88). Benjamin developed his aura framework based on technologies of representation available to him at that time (Citation1968), highlighting particularly authenticity, the uniqueness of space and time, and the role of tradition and rituals.

The multi-facets of authenticity

Authenticity both constitutes an object in itself and also serves ‘as something that requires contemplation and immersion from the viewer’ (Gelan, Citation2020, p. 119). Authenticity, for Benjamin (Citation1968), goes far beyond the straightforward reality of an object and speaks also to the reality of the experience it creates.

Emerging reflection on authenticity within marketing discourse (Belk & Costa, Citation1998; Goulding, Citation2000; Goulding & Derbaix, Citation2019) has focussed on the negotiation of consumer goals as linked to perceptions of the authentic (Beverland & Farrelly, Citation2010); paradox, contradiction and negotiation in authentic or hyperauthentic experience (Rose & Wood, Citation2005); and the various cues for validating the authentic object or experience (Grayson & Martinec, Citation2004). Furthermore, authenticity has become a foundational concept of marketing, cultural and arts studies, in fields ranging from music consumption to tourism and heritage (Bolter et al., Citation2006; Goulding & Derbaix, Citation2019; Graburn, Citation2004; Rickly-Boyd, Citation2012). Besides, marketing scholars also put significant effort into developing various genres of the concept (Grayson & Martinec, Citation2004; MacCannell, Citation1973; Selwyn, Citation1996). Importantly, authenticity has been portrayed not only as a feature of a particular object but also as based on the person or group being authenticated (Dolan, Citation2010; Moore, Citation2002). Wang’s study (Citation1999) introduces ‘existential authenticity’, as distinct from objective or object-related authenticity. Existential authenticity focuses on activities and experiences and can be further classified into intra-personal and inter-personal authenticity. Inter-personal authenticity encourages consumers to ‘search for the authenticity of, and between, themselves’ (Wang, Citation1999, p. 364), using the object to call people together to experience an authentic inter-personal relationship. The intra-personal dimension, on the other hand, invites one to reach inwards to search for bodily pleasure and feelings, whether relaxation, recreation, or refreshment and excitement (Cohen, Citation1979; Wang, Citation1999). Wang’s model has proven invaluable in examining religious consumption, especially through the experience of pilgrimage, where gaining authentic religious value is the primary purpose of the journey. The increasing popularity of cyber or online-only pilgrimage (Helland, Citation2007; Tzanelli, Citation2020), however, invites reflection over whether such digitally mediated religious experiences are as authentic as offline expressions, reminding us of Benjamin’s fear of the elimination of authenticity in the age of mechanical reproduction (Hill‐Smith, Citation2011).

The sacredness of space and time

Benjamin suggests the three concepts of space, time and authenticity are inter-related and mutually interoperative: aura is described as ‘a strange weave of space and time’, ‘the unique appearance of a distance’ (Citation1931, pp. 222–223). It is the effort of ‘determining the space and time of a work of art that enables the location of the presence’ (Gelan, Citation2020, p. 122); the uniqueness of contemporary ‘here-and-now’ experiences guides an aura’s ‘authenticity’, with the latter evoked through the convergence of space and time (Gelan, Citation2020).

‘Space’ for Benjamin (Citation1968) refers to both the environment in which the object is placed and the so-called ‘meeting space’ in which the audience encounters the object, and by which aura is constructed. The resonance between artwork and environment constructs a particular relationship between object and space which, for Benjamin, constitutes the object’s auratic value. In religious studies, space is often considered through the contrasting labels of ‘sacred’ and ‘profane’. Sacred space differs from ordinary, mundane profane space as the former represents the location of ongoing, inexplicable spiritual irruptions into human existence, varieties of ‘numinous’ (Otto, Citation1971) or ‘hierophanic’ experiences (Eliade, Citation1959). Physical demarcation between sacred and profane space can be defined, for example, by various architectural signifiers within religious buildings as worshippers move into the sacred space (Jacobs, Citation2007). Religious adherents believe that ‘experience of the mysterium tremendum in place grants [that location] a spiritual essence and poetic quality’ (Kong, Citation2001, p. 409), which sets it apart from the profane and ordinary. However, as Chidester and Linenthal (Citation1995, p. 17) rightly highlight, the sacred/profane binary opposition is all too easily collapsed, given its reliance upon the tension between other binaries: ‘hierarchical power relations of domination and subordination, inclusion and exclusion, appropriation and dispossession’ which are held in balance by ‘entrepreneurial, social, political and other profane forces’. Benjamin’s model of space as both an environment and context of encounter applies perfectly to understandings of sacred space in religion, but also challenges the preservation of aura in online religious observance, where the space of divine encounter relocates from the sanctified ground of the church to the profane environment of mass media. We might legitimately wonder whether sacred space can continue to exist if its threshold and boundary are so porous.

Benjamin’s aura framework acknowledges the intertwining between space and time to create ‘the here and now’ Citation1968, which evokes a sense of reverence among the audience. Accordingly, a replica cannot possess the authentic aura of the original (Gelan, Citation2020), and any reproduction would impede the uniqueness of the artwork (Bolter et al., Citation2006). Religion too often views space and time as very much intertwined; Eliade (Citation1957) acknowledges the connection (Kiong & Kong, Citation2000), suggesting time and space are neither homogeneous nor continuous, and both can also be classified as profane and sacred (Hwang, Citation2021; Pawlaczyk, Citation2021). The sacredness of time is an important theme of Christian theology and the biblical traditions, reinforced in daily liturgical recitations (Markus, Citation1994). Whilst sacred time is directly related to ritual events that can create ‘a sort of eternal mythical present’ (Eliade, Citation1958, p. 388), profane time refers to the ordinary, ‘without religious meaning’ (Eliade, Citation1957, p. 68). Time in Benjamin’s writing, referring to the creation of experience (Gelan, Citation2020), therefore seems to align well with Eliade’s understanding. Clearly, however, congregants do gain much from their participation in asynchronous online worship experiences (Morehouse & Saffer, Citation2021), and see them as offering a vital ‘point of contact’ with the divine (Asamoah-Gyadu, Citation2005; Cartledge, Citation2022). This reality invites reflection as to whether Benjamin’s concept of time needs reconsideration in the context of religious consumption.

Tradition

Highlighting the capacity of authenticity to transcend mere genuineness, Benjamin frequently acknowledges (Bolter et al., Citation2006), that the development of an object’s authenticity depends upon its tradition – the story of an artefact’s history and the past, ‘the quintessence of all that is transmissible in it from its origin on’ (Benjamin, Citation2006, p. 103). Thus, in exactly the same way that both ends of the axis of physical distance have impact on the auratic experience, both past and present together shape authenticity too. The significance of history and the past in Benjaminian thought is widely acknowledged; Jeffrey (Citation2015), for example, highlights how, for Benjamin (Citation1968), the sensation of being close to the past is key, emphasising how the thrill of proximity to a historic artwork enables and furthers the connection of the viewer to the piece. Translating Benjamin’s work, McCole (Citation1993) suggests that Benjamin sees tradition as ‘communicability, the transmissibility of experience’ more than ‘a particular canon of texts or values’ (p. 2), further asserting that all auratic experience ‘is a matter of tradition’ which individuals accumulate unconsciously throughout life (p. 2). The sense that one is just the latest among many individuals over many generations to interact with an object elevates significantly the experience the engagement creates.

Benjamin himself sees reproduction as bringing the past and present of the aesthetic to the audience, proposing that the singular, auratic object is manifested by its history and functions, ‘which enshroud it like a veil and render it resistant to use in the present’ (Benjamin, Citation2002, p. 127). Technological reproduction is capable of stripping away this veil, freeing the object from its physical history. By emancipating an object from its embeddedness in tradition, technology frees it from a dependence upon ritual and renders it malleable, albeit, perhaps, at some cost to its authenticity. Religious consumption, too, acknowledges the possibility of such changes in tradition, recognising that structure, details, and interpretations of traditions can be changed over time and place (Bell, Citation2009; in Kapoor et al., Citation2022). The traditional and the innovative may from time to time converge, and such alignments are always significant, even if temporary, since they serve to refine and reframe the tradition (Kapoor et al., Citation2022).

Rituals

Embedding an object in tradition is crucial to its ‘auratisation’, therefore, and this embedding is often accompanied or facilitated by ritualisation. Benjamin even suggests that the value placed on the uniqueness of the authentic work of art has its origin in notions of ritual function – which, in ancient times, was often either religious or magical (Benjamin, Citation1968, Citation2008). Similarly, Bell notes the innate capacity of ritual to build tradition around itself, emphasising how rituals both reflect and comprise formalised tradition (Citation2009, p. 124),

Marketing scholars have long been interested in the study of rituals (Bonsu & Belk, Citation2003; Otnes & Scott, Citation1996; Rook & Levy, Citation1983; Wallendorf & Arnould, Citation1991; Yoko et al., Citation2011). To date, though, Rook’s (Citation1985) study of rituals has perhaps been most widely cited. Defining ritual as a symbolic activity performed in episodic sequence and repeated over time with inner intensity and sincerity, Rook identifies four components of rituals: artefacts are the objects and products to be used in the ritual; scripts are a sequence of behaviours performed by those holding ritual roles; the audience is the group of people targeted by a ritual; and performance roles identify the various functions of participants in ritual whilst still acknowledging some flexibility in those duties.

Rituals have long been an interest of scholars of society, culture, and, particularly, religion, of course. In the context of religious consumption, ritual artefacts, scripts and performance can all be open to change and revision to facilitate new forms of engagement and new audiences (Kapoor et al., Citation2022). In religious consumption, worshipful response is key (Lèvi-Strauss, Citation1969), and for Benjamin, this response would be an auratic experience too. Benjamin (Citation1968) argued that auratic value requires dialogue, interaction between the viewer and the object, suggesting that it is the encounter that opens the space of auratic contemplation (the emergent space between object and subject, in which one approaches the other). This conceptualisation invites new forms of ritual participation that can reaffirm the position of the sacred and recreate engagement with the audience through identifying new roles for traditional religious components in ritualistic practice (Golan & Martini, Citation2018).

Research gaps

Benjamin’s aura framework (Citation1968) has been influential across a variety of academic disciplines. Aura and authenticity are commonly used especially in studies on tourism (i.e. Brida et al., Citation2014; Carter, Citation2019; Christou & Hadjielia Drotarova, Citation2022; Knudsen et al., Citation2016; Rickly-Boyd, Citation2012; Shehade & Stylianou-Lambert, Citation2020; Szmigin et al., Citation2017). The interaction between time and authenticity have been discussed in Hannam and Ryan’s study on museum and photographic storytelling (Citation2019), while notions of space and authenticity feature in studies on education (Imai, Citation2003; Peim, Citation2007) and urban experience (Kang, Citation2009). Golan and Martini (Citation2018) drew on Benjamin’s perspective on site and place to discuss the mediation of holy sites and experiences. Recently, Goulding and Derbaix (Citation2019) discussed the association between aura, authenticity and tradition in their study on music consumption, whereas Alexander and Doherty (Citation2022) developed their understanding of brand aura within the management, marketing and tourism literature with reference to Benjamin’s framing of aura and authenticity in time and space.

It can be seen, therefore, that other studies have tended to employ selected theoretical concepts from Benjamin’s aura framework (Citation1968) in examining a particular phenomenon. In our study, we aim to understand the digitisation of the churches’ message and consider how they capture their ‘aura’ on digital and social media platforms. We aim to deploy the key elements of Benjamin’s aura framework (authenticity, tradition, rituals, space, and time) to develop a holistic theoretical lens to look at religious consumption in the digital era. Concepts that are key to Benjamin’s aura framework, including rituals, traditions, relational discourse, and conceptualisations of the sacred and profane, are all foundational concepts in the study of religion, and indeed have their origin there. For instance, religious studies readily acknowledge the connection of authenticity to related concepts such as tradition, truth, and modes of legitimation and authority (Gauthier, Citation2021). In addition, concepts of time and eternity (common themes across religions) also offer rich context for further understanding the concepts of space and time which could expand the framework of aura originally proposed by Benjamin. Further, both religion and marketing scholars are interested in examining how a lack of physical co-presence reshapes experiences. The Internet’s liberation of space and time may pose increasing challenges to worship experiences, which are traditionally constructed by physical location and bounded by a specific space and time. Exploring the digital presence of megachurches in cyberspace serves as our research focus in the light of growing interest in understanding how megachurches represent themselves in cyberspace and enhance visitors’ participation (Cartledge & Davies, Citation2014, p. 65). It is thus important to see how megachurches can maintain and enhance their continuing engagement with online congregants despite emotional, psychological or physical distance. Furthermore, as the novelty wears off and the high levels of online participant engagement during the early stages of the pandemic fade away, it is worth considering what churches might do to maximise the benefit of their crisis experience to sustain and promote digital relational interactions in more ‘normal’ times.

Our focus on the aura of megachurches and how it can be promoted through strategic social media activities also contributes to wider appreciation of the mediatisation of religion (Hjarvard, Citation2011; Przywara et al., Citation2021), by offering some key empirical insights. We aim to expand our understanding of the ‘dialectic relationship’ between religion and the media (Hoover, Citation2011, p. 613), allowing us to obtain new insights into the adaptation of religious practices to align with media platforms and, in turn, explore the transcendent role of the media in accommodating churches to deliver their ritual experiences to online congregants.

Methodology

In this study, we employed an interpretivist, qualitative approach to gain multiple perspectives upon our defined research problem (Greener, Citation2008). Case study is one of the frequently used methodologies in qualitative research (Creswell, Citation2013; Marshall & Rossman, Citation2014; Patton, Citation1990), and is eminently suitable for new research areas (Eisenhardt, Citation1989), since it enables a real-time phenomenon to be explored within its naturally occurring context, with the consideration that context will create a difference. Following the pattern established by many other studies of online religion (e.g. Canavan, Citation2021; Sircar & Rowley, Citation2020; Yip & Ainsworth, Citation2020), we chose a specific case study to illustrate how churches utilise social media to connect with congregants during and post-pandemic. We focused on Kingsway International Christian Centre (KICC), a British-African megachurch which has a longstanding tradition of reliance upon technology (including but not limited to digital space) to promote its religious practices and identity and its aspirations to be a ‘church without walls’. (Please see Appendix A for a justification for our choice of KICC as Case Study).

In order to access and explore the online activities and interaction between the church and its congregants, our research adopted a ‘netnographic’ approach. ‘Netnography’, coined by Kozinets (Citation2015), refers to digital ethnography that acknowledges the cultural significance of virtual spaces as worlds of meaning-making (Sumiala & Tikka, Citation2013), highlighting the complexity and nuance that they provide and their increasingly important contribution to everyday social behaviour (Canavan, Citation2021; Mkono & Markwell, Citation2014). As Wu and Pearce (Citation2014) suggested, netnography can be used to positive effect in exploring newly emerging phenomena. This study draws on four years of content from KICC’s website and its key three social media platforms: its YouTube channel, Facebook page, and Instagram feed, from August 2017 to August 2021. This dataset features over 2,000 original posts of inspirational textual and visual content as well as online events. We collected screengrabs as visual data to illustrate consumers’ interactivity and engagement with the church through social media (Gurrieri & Drenten, Citation2019). Both authors engaged in participant observation in online worship experiences available through these sites. This time scale was chosen because 2017 marked a strategic ‘step up’ in KICC’s development and online engagement, with a wide variety of hybrid events, both onsite and online. After completely switching to online delivery mode during the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic lockdowns, it was really not until August 2021 that KICC returned fully to its previous hybrid mode to align with the government guidance which was operative at the time.Footnote1

Data collection

Data collection consisted of reviewing, fortnightly, KICC’s website content and its public posts on its social media. We also conducted sampled online observations of the church services, attending carefully to the changing role and style of these events as the pandemic took hold from March 2020, and the development of new experiences (such as the ‘Morning Glow’ service). We reviewed older, pre-pandemic posts to ‘acclimatise’ ourselves to the culture and wider approach of the church (cf. Canavan, Citation2021), gaining insight into the distinctive dynamic of the interaction between congregants and the church’s leadership. Close observation of more recent material enabled us to examine critically the content delivered in the preaching, the observance of rituals in the online platforms, and the ways in which online congregants respond to the pastor and the church during and after the service. The status of the authors as participant observers, and our distinct subject specialisms, allowed us to draw at various times upon both emic and etic perspectives in our analysis. Combining pre-, peri- and post-pandemic data sets, we generated a longitudinal perspective – a panoramic snapshot, perhaps – of the ongoing evolution of a religious community (cf. Canavan, Citation2021).

To maintain the uninhibited manner characteristic of online ritual events and the religious communities in general (Mkono & Markwell, Citation2014), we adopted a covert, passive form of netnography that prohibits researchers from revealing their research activity to online participants as well as from participating in online activities. This approach is common among tourism researchers and also religion scholars (i.e: Canavan, Citation2021), and such a passive stance is proven to do no harm to the intimate or extended participation with an online community. To address Kozinets’s (Citation2015) critique of the potential ethical drawbacks of the passive approach, we ensured full compliance with appropriate ethical guidance (cf. Association of Internet Researchers [AoIR], Citation2019; British Sociological Association [BSA], Citation2017). This includes maintaining the anonymity of participants through blurring the faces and screen names of online participants who interacted with the church’s livestreams, took part in their events, or commented or posted on the church’s platforms. We did not make any posts or comments ourselves or seek to access any data that was not clearly intended for open public access or was published behind any kind of paywall or registration system.

Data analysis

When interpreting empirical material, we performed our coding in accordance with guidance for case study analysis (Coffey & Atkinson, Citation1996; Flick et al., Citation2004; Hesse-Biber & Leavy, Citation2011). We particularly used the PESI approach (preparation, exploration, specification, and integration) (Rashid et al., Citation2019), with each author analysing the data individually during the first three steps, before we then aggregated our observations.

We started by processing all forms of data including both textual and visual formats, which then helped us to move to develop a range of open codes. For the website data, we considered histories, narratives, texts, images, podcasts, global networks, and commercial activities (Cartledge & Davies, Citation2014). Facebook posts were recorded as both texts and screenshots and organised in a chronological order. These posts were considered in relation to a memo created by the first author, who attended KICC live stream worship services on Facebook. To organise and analyse visual data generated from Instagram posts, a manual coding process was adopted. Each author looked at 30 posts, seeking to analyse key messages, uses of images and colour scheme, and the context of the posts. We also used posts’ captions and hashtags to support the manual coding of images, which is a useful practice adopted by qualitative researchers who conducted research on Instagram (Filieri et al., Citation2021). We then developed together agreed coding frames, which then allows the thematic codes to emerge (Nowell et al., Citation2017). At the exploration step, key codes were developed and re-examined constantly and then transformed into concepts based on their differences and similarities. This enabled us to move to the third PESI stage, at which we can see the connections between concepts from which we can observe the patterns and reflect on literature to create relevant categories. At the final step, we compared our empirical interpretation to see the crosscutting patterns and significant differences to develop and expand a framework for this study. To assist the process of content analysis, we applied Benjamin’s aura framework (Citation1968) as the methodological lens to develop themes of findings and extend our analysis.

Findings

Re-mooring traditions

In popular usage, ‘tradition’ implies an unchanging and fixed approach to an activity – something that has remained constant over time. However, under crisis situations, the established manner of observance of a tradition becomes unnecessary, undesirable or impossible, which leads to transient and short-lived changes in traditions (Kapoor et al., Citation2022). KICC, like many other churches and religious institutions during the pandemic, responded to the crisis by adopting ‘invented tradition’, integrating their creative responses to the emergency circumstances into their ongoing practice and identifying opportunities to recontextualise their traditions. As such, the church prioritised clinging to the values, calendar and ritual practices which established its distinctive identity, retaining, repeating and reemphasising its vocabulary and core messaging to assure continuity with historic practice (Hobsbawm, Citation1983) and underpin the continuing ritualisation of its online experience. KICC relied entirely upon digital platforms to support the creation and dissemination of new symbolic meanings and traditions of the church in cyberspace, a process which has been labelled as ‘re-mooring traditions’, since it allows the various symbolic forms of the church’s ritual practice to be produced and circulated into wider and other contexts ‘than what is bounded by face-to-face interaction’ (Thompson, Citation1995, p. 180).

What are those symbolic forms? Perhaps among the most prominent in KICC and many British African congregations is the status and personality of the senior pastor or leader of the church. Senior pastors in the Pentecostal tradition, especially in the African context, do not hold the same role as the Anglican vicar or Roman Catholic priest, not least in that their personality is often more important than their professional status. Their strength, charisma, ‘anointing’ (Asamoah-Gyadu, Citation2005) and spiritual power are intensely valued by congregants and fellow ministers, and they are often perceived to have a strong and direct connection to God (Ojewole & Ehioghae, Citation2018), frequently being labelled a ‘man of God’. The authority and authenticity of religious experience depends, in Pentecostalism, upon the ‘divine mystique’ (Ojewole & Ehioghae, Citation2018, p. 327) of the man of God much more than upon correct liturgical observance. KICC’s Senior Pastor, Pastor Matthew Ashimolowo, came to the UK from Nigeria in 1992 to establish the church, and thus holds even higher status and recognition as its founder, through which he has had primary responsibility for the shaping of the church’s values, activities and practices. Before the pandemic, Pastor Ashimolowo already functioned as a mediator of KICC’s religious traditions, embodying the church’s cultural and social aspects. In person and in most visual representations he comes across as a dynamic man of action, power and influence (Cartledge & Davies, Citation2014). His smart suits and polished presentation (https://www.instagram.com/p/CdV-5peKalw/?igshid=MzRlODBiNWFlZA%3D%3D) mark him out as a successful professional and prosperous entrepreneur, asserting his high status within the community. He serves as a visual affirmation of the promise that God will cause KICC congregants to flourish in every area of their lives if they put God and God’s kingdom first (a key theme of the church’s teaching).

Pastor Matthew is a focus of aspiration, therefore, as well as of unity and cohesion. KICC’s social and digital platforms continued to deliver these elevated images of the pastor through posts and edited images throughout the pandemic. However, the emergence of daily church online events which began with the first UK lockdown led to something of a ‘levelling down’ of the pastor’s image to a more informal and approachable status, in which the pastor wore casual shirts to deliver his preaching (https://www.instagram.com/tv/CfHLejOK8w4/?igshid=MzRlODBiNWFlZA%3D%3D).

This dual representation serves an important purpose. In cyberspace, digital representations are the only way by which followers can engage with their leader. Recent studies have highlighted the significance of such a paradoxical emphasis on distance and directness in visual representation on social media platforms, such as Instagram, in creating congregants’ perceptions of the pastor as both an approachable figure and an elevated man of God (Golan & Martini, Citation2020). Both these contrasting presentations matter, especially in a context where in-person engagement is impossible, in order for the pastor to be seen as a fully rounded character. His elevated status presents him as elite, different, bigger, stronger, wiser, and better than the congregants, worthy of respect and worth listening to. His more approachable and everyday representations show him to be someone who is just like a member of the congregation, someone facing the same challenges, but clinging to his faith and his values in confronting them, modelling the way to behave but in a way that followers can relate to (Shamir, Citation1995). In discussing the increasingly mediatised relationship between the leaders and those they lead, Antonakis and Atwater (Citation2017) highlight the significance of both physical distance and perceived social distance between the two groups. The mediatised forms of leadership Pastor Ashimolowo embodies, created from both his elevated and approachable statuses, thus increase the levels of physical distance between the church leader and the congregants, a distance required for the creation of aura (Benjamin, Citation1968). Whilst his elevated representation creates distance and strengthens his status as a ‘man of God’, simultaneously his approachable representation reduces the levels of perceived social distance to develop a sense of closeness and compassion (Golan & Martini, Citation2020). During the pandemic, a sense of closeness, frequency and quality of interaction was important for congregants to maintain their engagement and connection with the church. They needed a sense of continuity but also a new level of intimacy in their interactions; the traditional portrayal of the pastor needed to be reinterpreted and re-moored for a new context.

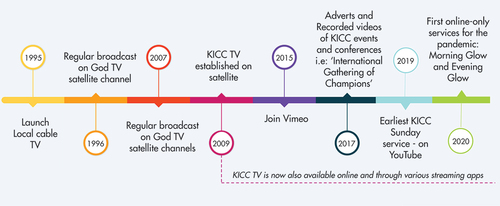

Besides the mediatisation of the pastor, KICC also effectively uses its website to communicate its own tradition as an organisation – the history it presents and the past it embodies – to ensure its ongoing work is anchored in its historical growth and development. The church draws upon this narrative to generate and sustain its relationship with its audience to create a sense of continuity and of ‘being close to the past’ among its congregants (Appendix B). Established congregants need, in the height of the pandemic when they are unable to access in-person worship, to be assured that they are still participating in fundamentally the same experience. The church’s distinctive rhetoric and core language are kept consistent throughout its website content, showing that KICC places a strong focus on themes of ‘raising champions’ and on miraculous divine intervention. KICC’s Christianity emphasises very strongly aspiration, opportunity, personal success, and prosperity at every stage. We should note that KICC’s history shows how the church has some prior experience of the reinvention of tradition through re-mooring, dating back to their use of various audio-visual platforms even before the pandemic ().

Whilst KICC has long been a media-savvy and media-sensitive congregation, their comprehensive mediatisation during lockdown endowed their traditional observance with fresh vigour and re-moored their tradition into new online contexts (Kapoor et al., Citation2022) through digital transformation of its rituals. Rituals and traditions are closely related; as Catherine Bell has observed, ‘Ritual can be a strategic way to … construct a type of tradition’ (Citation2009, p. 124). It is therefore important to examine the changes and adaptation in rituals performed by KICC during the pandemic.

Transformable rituals

For Benjamin (Citation1968), rituals do not only create relationships between audience and the auratic object, but also expand to social relations, the connection and interaction among people. Benjamin proposed that the auratic values of an object are also constructed by ‘the relationship of otherness’ and intimacy with which the audience could establish a connection (Johnson, Citation2010, p. 10). As we noted, for Benjamin, technological replication could hinder the traditions, rituals and relations, and a dissolution of social interaction would impose a potential threat to auratic value. KICC actively addressed this challenge through practices we label ‘transformable rituals’, a term we coin to acknowledge how KICC manages to maintain the key elements of religious rituals and, simultaneously, develop appropriate and dynamic variations in the virtual service’s content and process (O’Leary, Citation1996). Adopting Rook’s approach to ritual elements (Citation1985), we observed changes in two key ritual elements of KICC during the pandemic: script and performance.

Adaptation of ritual script

Ritual is a central component of pretty much any religious experience. Expressions of Christian worship across all the many and varied expressions of the church worldwide have a number of core elements in common, including observation of the Eucharist, the ministry of the word (reading of the Bible and generally a sermon or homily), sung worship, corporate and private prayers, and a blessing and final dismissal. These components – and sometimes the words used to introduce and explain them, the liturgy – date back to the very earliest days of the Christian church. Though Pentecostal worship has distinctive stylistic differences, it too tends to observe traditional overarching patterns of worship which are recognisable worldwide (Kay, Citation2009) even though they tend to follow an oral rather than formal written liturgy:

Most of the core ritual elements are in evidence in KICC’s worship gatherings both before and during the pandemic. The church’s online worship experiences often include prayers, bible readings, announcements of upcoming activities and invitations to participate, an extended and interactive sermon and lots of enthusiastic singing, with frequent responses (including applause, shouts of ‘Amen’, ‘praise the Lord’ and dancing), often prompted by the pastor or other members of the platform team, and often relying upon stereotypical language (‘let’s give the Lord our praise’, etc.) and reflected back from the congregation. (Researchers’ memo, August, 2020).

Significant adaptations can of course be observed, however, to accommodate worship in a virtual environment, especially during lockdown:

KICC’s in-person services could easily last for 2.5 to 3 hours, including extensive time of sung worship, bread and wine provision, and financial giving … The church’s first online-only service for the pandemic (29 March 2020) lasts for just 54 minutes, and Pastor Matthew is the only person to appear onscreen. The service is presented live from KICC’s main auditorium, but without a congregation, so there are no shouts of praise in response to the pastor’s own ritualised expressions, and the emptiness of the auditorium is very much evident from the audio too. Other than that Ashimolowo’s preaching delivery is very much as usual, with an inspirational and encouraging message, emphasising in his conclusion the need to obey the lockdown legislation but stay faithful and trust God. (Researchers’ memo, 29 March 2020)

By keeping to the core scripts performed by the pastor, KICC’s online ritual events still offered the same key components to the congregants despite their condensed time. Some reductions in rituals were straightforwardly practical. For example, observations of the Eucharist during the pandemic required congregants to provide their own bread and wine at home (using unconsecrated bread and wine in this way would not have been considered a valid observation of the eucharistic ritual by some traditions of Christianity but is entirely acceptable to Pentecostals). Financial giving within the ritual script was transformed and integrated into the livestream in the form of a banner advertising online donations (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_otaOVjuYlo, at 2:24:43). This was a practice KICC initiated before the pandemic, but it became more crucial in the pandemic since online financial giving in this way became their only source of donations when the physical campus was closed. This element was therefore more directly included in the ritual script for online worship.

Transformation of ritual performance

One specific advantage of the move to online worship, perhaps, is the facilitation of new opportunities for interaction and engagement in worship. Jacobs (Citation2007) points to the important distinction between synchronous and asynchronous ritual interactions. Traditional in-person worship, for most Christians, is synchronous and congregational. Christianity is not, like some other religions, a faith that is principally observed within the family or by individuals alone in isolation. Shared, corporate engagement in physical locations has always been a focal point of Christian worship. The live chat functionality on a platform, such as YouTube, seeks to replicate something of that shared experience by enabling remote congregants to participate actively in the experience and add their own comments and expressions of praise (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=58EYgjwBbpc).

KICC online brings people together into a virtual communal worship space, creating a positive and affirming, yet relaxed and informal environment and approach to the service. Participants via both YouTube and Facebook can freely type their expressions of gratitude and love towards God and the community in the chat box using emojis, using the heart icon and prayer hands to illustrate their emotions and reflect the physical actions that they would have been undertaking if they’d been in the physical church building. The church livestream host typed responses to some of these comments. These textual and graphical responses replace the vocalisations and hand and body movements which are typical of in-person worship in Pentecostal churches. The adjustment in response and reciprocation between the pastor and the congregants forms the second unique character of the online ritual practices.

These uses of ‘like’ functions and emojis on social media platforms have been referred to as ‘social media affordances’ (Cabiddu et al., Citation2014), where social media design features are utilised to aid and trigger user engagement on social media (Majchrzak et al., Citation2013). Social media affordances have different characters, among which connectivity is ‘at the very heart of social media’ (Olsson & Eriksson, Citation2016, p. 191), which is built on the notion of sharing, interacting, and talking (Cabiddu et al. (Citation2014). This explains how social media affordances emerge from the interaction between social media and users. These affordances are both closely linked to ‘opportunities of actions provided by the design and socialisation features of social media’ (Lin & Kishore, Citation2021, p. 3) and able to aid users to achieve their communicational goals via social media features. Social media affordances also allow the online congregants to participate synchronously and perform a ritual as a collective at the same time (McSherry, Citation2002). The ‘real-time comments’ component of Facebook’s livestream video provision offers similar functionality with the additional benefit that later commenters can also comment at specific times in the video, enabling them to feel that they are adding additional value to everyone else’s experience of engagement in the worship experience. The capability of providing feedback and impressions through commentaries on social media further confirmed CitationCabiddu et al’.s (Citation2014) findings of the capability of social media affordances in enabling a degree of real-time interaction and enhancing the immediacy of conversations, enabling the persistent engagement much needed in religious ritual events.

Following Collin’s account (Citation1992), conventional religious ritual comprises three key components: first, the sentimental, emotional energy through the physical co-presence of people; second, the ritualisation of actions through gesture and voice co-ordination of participants; and third, a symbolic sacred object for reification purpose. In an online environment, physical co-presence transforms into a social media co-presence, whereby each congregant of KICC will be recognised by their profile picture or an avatar of their choice. A sense of co-presence and co-ordination is achieved through participants’ contributions at the keyboard, as they type their responses to the Pastor’s invocations. Participants’ voice and gestures are recognised through their chat messages and their use of emojis. Such changes in a digital ritual environment are not absent in existing research. Rather, virtual ritual practices with relevant variations have been acknowledged as novel ways to reproduce some of the essential features of a charismatic gathering in the ‘real world’ (Young, Citation2022).

Asynchronous engagement with livestreamed experiences is also an interesting and significant phenomenon. Later viewers are, on Facebook, unable to contribute to the live chat, but they can leave a comment on the video as a whole subsequently, and a general review of the comments shows that some respondents do indeed use these comments in the same way as the chat function, i.e. to respond directly to specific moments in the worship experience (https://www.facebook.com/KICCUK/videos/232834988640888).

Comments include more generic thanks to the Pastor and praise to God but also specific responses such as ‘I receive this’, ‘yes sir’, ‘amen’. At least some worshippers try to replicate the synchronous experience of participation through asynchronous engagement. In this way, asynchronous ritual performance blurs perceptions of ritual time, and indeed of sequence, since asynchronous viewers can so easily pause and skip, rewind and fast-forward, and thus control the parameters of their engagement with the experience. As Castells (Citation2000) notes, this means that end users have more control over their engagement with the ritual performance than those who are conducting it; ritual loses its chronology and potentially also its sense of direction and purpose and is broken down into a series of individual time-limited components depending upon the viewer’s need and context.

The re-sacralisation of profane space

Churches predominantly depended upon their physical presence until the pandemic meant in-person gathering was impossible. However, megachurches have long been expert in the creation of the spectacular ritual spaces and heavily reliant upon technology to carry their ritual experiences beyond the four walls of the building. KICC, a megachurch positioned as a ‘church without walls’ with a large reach on multiple (online and physical) spaces, thus invites us to revisit concepts of space in religious consumption. Importantly, KICC’s inclusive approach to spaces during the pandemic encourages some expansion of Benjamin’s concept of auratic space (Citation1968), which originally referred to a singular space required in order to create a unique existence – the auratic object.

KICC launched its online daily Morning Glow and Evening Glow livestreams during the pandemic given the growing demand for church services during the national lockdowns, and these have been made accessible via various platforms since 2020. Many churches worldwide turned to livestreaming to support the needs of their congregations during lockdowns (Przywara et al., Citation2021). For KICC, these online daily services supported anxious congregants at the onset of the global pandemic but have also become an important part of the wider ritual experience offered by the church since then. Accessing a church service from one’s home even enables the process of meaning seeking and the creation of experience, as engagement has become possible by participants’ own arrangement. Bringing religious space into the home has been described as ‘living-room ritual’ and ‘cyber-ritual’ by Kong (Citation2001), who propounds the possibility of vicarious experience in cyberspace. There can be no distancing from – or transition to – ritual space which now finds embodiment in the home and moves beyond the physical location to become a sacred moment in time in a fundamentally profane space. This understanding fits in well with Björkman’s (Citation2002) perspective, built upon Benjamin’s framework (Citation1968), which discusses the importance of an intervening space that allows participants to actively engage with the organisation and become involved in the process of meaning construction. KICC offered these daily church services to provide spiritual support to its congregants at a time of unprecedented fear and uncertainty across the world.

The church’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic and its impact on the shape and functioning of societies (Przywara et al., Citation2021) represents and embodies the acceleration and intensification of the mediatisation processes of religion. Mediatisation is the process whereby media institutions and representations take over control of imaging, messaging and meaning-making from the social agencies which previously lead such functions, thus reshaping and reconfiguring cultural expectations in their own image (Lövheim & Lynch, Citation2011). During the national lockdown, the use of media platforms became the only way for churches to continue to host public worship. Thus, these platforms started to dominate the social order, and churches needed to follow the logics of the media (and social media) platforms. The media platforms are of course entirely secular, but assumed a dominance and importance as great as any that religion could ever have had . Importantly, mediatisation theory demonstrates that, while the media acts independently, it can embed itself within and thus transform societal institutions. As Hjarvard (Citation2008) explained, mediatisation also results in the two-way adaptation of logics between media and other social institutions. Religious ideas, values and messages are circulated in a wide variety of ways online, and the Internet invites replication and reconfiguration of the various elements of worship to suit the needs of online audiences (Szocik & Wisła-Płonka, Citation2018, p. 86). Such reconfiguration and alignment thus enable faith communities to rely on the tools offered by traditional and social media to promote their work and build their platform (Graca, Citation2020). This phenomenon is evident in the ways in which KICC has reconfigured its approach for an online audience. There are a variety of other ways in which KICC has aligned its approach to Pentecostal rituals and traditions with the logics of websites and social media platforms, encouraging both synchronous and asynchronous interactions, as found in .

Table 1. Aligning logics of KICC and logics of Instagram, YouTube, Facebook, website (Researchers’ memo).

KICC’s virtual sacred space accommodates both synchronous and asynchronous cyber rituals. The mediatisation of this space has determined the way in which religion and beliefs are disseminated throughout society, as well as created new patterns of communication within religious groups, often ‘transforming or destabilising traditional religious communication flows’ (Campbell, Citation2017, p. 18). Digital space thus should be seen as principally a place of meeting, primarily a space of ‘social interaction and communication’ (Wertheim, Citation1999, p. 232), rather than merely a store of information. In this context, the social function of ritual is ‘to unite adherents’ in a community, ‘as a form of communicative action’ (Jacobs, Citation2007, p. 1111, 1116) which connects beautifully to the opportunities that cyberspace affords for the creation of new forms of and contexts for such community. KICC has been consistently building up ‘webs of personal relationships in cyberspace’ (Rheingold, Citation1993b, p. 5) for years through various platforms. Thus, its techno-religious spaces are not just a temporary solution or a short-term alternative to their main church services – they are the official religious spaces, and are expanding further to perform the role of rituals, which is to ‘create things and satisfy needs’ (Tække, Citation2002, p. 23), and to offer a new communication environment that leads to transformation of time – space relations in communication (Drag, Citation2020, p. 94). The additional flexibility offered through online worship is not only about space, however, it is also about time.

De-sanctification of sacred time

Similarly to space, sacred and profane time can be integrated in a human’s lifetime, by taking part in sacred events which are able to guide communities to ‘pass from profane time to the sacred plane of existence’ (Geffen, Citation1974, p. 180). KICC offers their members infinite opportunities to transform their profane time into a sacred moment of engaging with their faith through the use of content reproduction, such as recorded videos on iTV, live streamed video on YouTube, Facebook and Instagram. KICC YouTube videos attract thousands of views each day, between 30K-70K/video.

At first sight, KICC might seem to break the rules of the uniqueness of each ritual event and time with its uses of recorded video and live streamed church services on multiple online platforms. However, a de-sanctification of sacred time enables the church to reconcile ‘competing temporalities’ – periods of lockdown, the British working week, livestream schedules, individual agendas and timetables (Mukherjee, Citation2022) – to serve the highest purpose of religious rituals: developing a connection between congregants and God, and among congregants. Importantly, it is the availability of time that helps church members to create sanctified time from their profane time. As explained by Eliade (Citation1958), the church indeed is enabling its attenders to gain more sacred time out of their ordinary lives, because of the power of ritual to interrupt the profane, helping adherents to transform their ordinary time to sanctified time. For Eliade, then, sacred time makes profane time more ‘bearable’ (Citation1958), and if people are able to disengage themselves from profane time through engaging with certain rituals, then they are capable of enduring a profane world (Eliade, Citation1959, p. 190). And if, as Geffen (Citation1974, p. 186) argues, profane time is ‘a burden to be endured’, then ‘[one’s] ability to transcend time largely results from her periodic renewals of vision and faith as she moves into the sacred time offered by [the religious event]’. An opportunity to access and expand one’s hierophanic time is even more crucial during the national lockdown, when people experienced uncertainty and chaotic time. KICC expanded this hierophanic time through various forms of exposure of messages on different platforms, both synchronously and synchronously, at different points of time to help congregants access the sacredness in their own arrangement ().

Table 2. Key messages of ‘stay strong and be hopeful’ from Morning Glow service (24 May 2021) across platforms and times (KICC Instagram, YouTube and Facebook feeds).

Modern electronic media changes our sense of time and of community by again enabling speech to be shared in the immediacy of real time (O’Leary, Citation2016), and subsequently repeated perfectly in different contexts at different times. Whilst one may challenge the ideas of a decay of the church’s aura due to the infinite capability of replay and reproduction, it should be noted that some theologians already view sacred time as circular, reversible, and periodically recoverable (cf. Eliade, Citation1959; in Geffen, Citation1974). The cause of erosion of the aura is thus not rooted in the repetition of time and recirculation of church events. Instead, it lies in the way in which people participate and how memory is created, as Eliade (Citation1959) emphasised. In this way, KICC breaks down the binary of profane and sacred time and focuses on the creation and expansion of pilgrimage time for its members.

A regime of authenticity

Benjamin’s assertion of the loss of authenticity during the reproduction process (Citation1968) has predominantly been used to support such classical approaches to the distinction between the ‘virtual’ and the ‘real’ (Radde Antweiler, Citation2012). In religious studies, critique of the authenticity of cyberspace rituals mainly questions the authenticity of experiences (i.e: Hughes-Freeland, Citation2006) or the sacrality of online space (e.g.Hill-Smith, Citation2009). Our previous observations on tradition, ritual, space, and time have, however, addressed these concerns. First, authentic participation experiences (Hutchings, Citation2010, p. 82) can be achieved through the use of traditional settings in religious online performances through transformable rituals, as we showed in highlighting the changes and adaptation of ritual script and ritual performance in the digital sphere. We also demonstrate how, whilst online services have long been part of the church, during the pandemic, KICC further adopted the re-mooring of traditions to consistently connect with, serve, and support its congregants. Second, we acknowledge the ongoing debate round the religious space and whether it is able to retain its sacredness when moving online. Authenticity is seen as something real, in contrast to ‘virtual’, implying that online worlds never achieve the state of being real (Rheingold, Citation1993a; Turkle, Citation1995). Our study shows that KICC was able to create an authentic virtual religious space through the dual use of re-sacralisation of profane space, aligning the logics of ‘secular’ media platforms with the logics of the sacred, and the de-sanctification of sacred time where sacred time is expanded through the use of media.

Besides addressing the two previously mentioned key critiques of authenticity in online religion, we also found that KICC develops its own approach to authenticity through a strong focus on human, personal growth and human interaction. This approach well aligns with Moore’s (Citation2002) suggestion that authenticity is less to do with the actual object, and more associated with the person or group being authenticated (Dolan, Citation2010). Such values offered by KICC could be examined and classified under two types of authenticity as proposed by Wang (Citation1999): intra-personal authenticity and inter-personal authenticity. Accordingly, the former refers to the embodiment of joy and personal fulfilment, while the latter focuses on authentic direct engagement with other participants (Goulding & Derbaix, Citation2019). Both of these states are crucial in creating a true, authentic self regardless of a person’s background.

Intra-personal authenticity

The defining marker of authenticity is, arguably, the primacy of personal experience in the validation and legitimation of practices and beliefs (Broo et al., Citation2015; Gauthier, Citation2020) and in the experience of self-orientation (Taylor, Citation2002), of embracing and exploring the reality of being true to oneself. KICC recognises all its members (and would-be members) as individuals, welcoming and encouraging them to freely exercise their right to choose within an open religious market. Seeking the meaning of true self is related to creating the meaning of authenticity (Steiner & Reisinger, Citation2006). KICC’s members choose to join a British-African church because the activities and practices offered by the church allow them to embrace independence and their whole selves, to express their tastes, their selves, and their true orientation. By placing the radicalisation of modern cultural logic at the forefront, KICC facilitates new types of authenticities which are in tune with people’s needs in everyday life, focusing on personal experience and aligning with the culture of authenticity. For megachurches like KICC, their dynamic church services effectively support congregants who are feeling isolated, lonely, and anonymous (Dougherty & Whitehead, Citation2011), which proved especially important during the national lockdowns in 2020–2021. Such pastoral care activities included, for example, the church’s weekly small group home meetings, ‘Caring Heart Fellowships’, which transitioned from in-person to online gatherings for the duration of the lockdowns (and continue, at the time of writing, to be bi-modal in delivery), as well as the church’s many other social welfare activities described online.

Subjective wellbeing, as a much broader concept than social status (Diener et al., Citation1999), is proven to help people to feel happier and improve self-control (Willard & Legare, Citation2017). Studies on consumer culture have long acknowledged the rise of products and services relating to self-development in line with increasing interest in a self-oriented form of spirituality (Dodds et al., Citation2018; Rindfleish, Citation2005). The global pandemic heightened this interest further, as across the world people sought in spirituality the meaning, purpose and wellbeing that they had lost along with their commonplace social and professional interactions (Del Castillo, Citation2021; Dodds et al., Citation2021; Finsterwalder & Kuppelwieser, Citation2020). Even before the pandemic, consumers increasingly demanded opportunities for self-actualisation (Basci, Citation2015; Rindfleish, Citation2005), spiritual transformation and inner-self exploration, in the quest for spiritual wholeness and better understanding of their whole selves. Such ‘transformation of their inner worlds’ has become a prominent aspiration for many, with rising popular interest in various forms of spiritual activities, including pilgrimages, meditation, yoga, and mindfulness (Basci, Citation2015, p. 446), and other services that aim at ‘authenticating, program-affirming celebrations of individual successes’ (Moisio & Beruchashvili, Citation2010, p. 871) are notably rising.

Inter-personal authenticity

The narrative of individual success is not, for KICC, a selfish one, however. The church has demonstrated since its inception a strong commitment to supporting wider society and encourages its congregants to reach out and give back to the community. This can be seen from its Community Initiatives webpage which promotes a range of services such as educational counselling, legal counselling, a hospital visitation team, and pastoral support services. Other social welfare projects the church pursues across London include programmes focussing on the rehabilitation of drug addicts, care for refugees and asylum seekers, and outreach services for the homeless, underprivileged and dispossessed. Through its website, the church receives donations to develop further services, including its foodbank and children’s playground.

Personal financial donations to the church create a network of reciprocity (Appau, Citation2021), and the congregation’s generosity arguably reflects their orientation towards mutuality (Arnould & Rose, Citation2016) as well as their willingness to give to God’s work. The very act of giving moves a person’s focus away from themselves and makes them a contributor to social change, facilitating a move, in Wrenn’s words, ‘from self-alone to others-before-self’ (Wrenn, Citation2010, p. 54). The various purposes of donations in religious organisations have been discussed in many studies and are well acknowledged as a means of contributing to an organisation’s mission of converting, educating, and improving the lives (and afterlives) of both believers and non-believers, physically and spiritually (Newman & Benchener, Citation2008). Through its donation schemes,Footnote2 KICC provides its members with the means to live a purposeful life on earth and ‘lay up treasure in heaven’ (Matthew 6:20; cf. Lim & Putnam, Citation2010), encouraging members to ‘contribute to the achievement of such goals by transforming self-interest to selfless interest in the welfare of others’ (Wrenn, Citation2010, p. 57). KICC’s messaging offers its adherents a vision of an extraordinary life and a pathway to reaching their aspirations through a commitment to God and to KICC.

At KICC, the connection between God, church and community expand to a much larger scale, with a wider range of events beyond donation and fundraising. Given the diversity of its audience, KICC has developed and maintained a range of events and activities before, during and after lockdown, to promote an authentic life and authentic self and appropriate the ‘culture of authenticity’ across the social spectrum. These key events are introduced on KICC website as well as on its social media platforms.Footnote3 KICC’s approach to abundance and its expansion of events to different groups of people with different exigencies has addressed this issue by introducing a unique regime of authenticity, commonly known as structuring characteristics and principles of group organisation (Gauthier, Citation2021). Indeed, just like other megachurches, KICC relies on small groups to build up a sense of belonging (von-der-Ruhr & Daniels, Citation2012) and enhance connection among members. Morehouse and Saffer (Citation2021) suggested this type of commitment is crucial to the church engagement since congregants may switch churches and take their donations with them if the sense of connection is lost. This engagement encompasses involvement, experiences, and familiarity with other church members, including congregants of the same church or among religious social media users (Campbell & DeLashmutt, Citation2014).

It can be observed that the special bond and connection in KICC’s inter-personal authenticity has added a unique element to the church’s authentic values. It is the connection that blurs the division between the real and the simulation, bridging the virtual and actual to construct the real, as Boellstorff emphasises: ‘What makes these virtual worlds real is that relationships, romance, economic transactions, and community take place with them – in short, that they are places of human culture. It is this social reality that links virtual and actual’.

Discussion: conceptualising ‘digital aura’

Our findings suggest that the digital imbues its own aura and accrues an auratic quality that influences its reception and impact (Jeffrey, Citation2015, p. 145), and defines the core value offered to the participants. Our research offers a closer look into the concept of digital aura, defining its dimensions in relation to the context of religion and community engagement in a virtual world. We will first discuss the emergence of digital aura from the classic aura framework. This will be followed by our re-construction of aura, in which we pay careful attention to the notions of authenticity, tradition, space, time, and rituals and resituate them in cyberspace. Finally, we will highlight the role of digital aura as a supplement to the Benjaminian framework (Citation1968).

From aura to digital aura

Benjamin develops his concept of aura (Citation1968) throughout his writings, highlighting the on-going ‘crisis’ of aura provoked by the development of reproductive media (Bolter et al., Citation2006). Newer practices go beyond older methods and challenge the old ways in which people perceive aura. For instance, photography exceeds the visual fidelity of portrait painting; edited film can improve upon performance due to post-production. Simultaneously, however, these technological enhancements might be seen as placing authenticity, and thus aura, at risk.

Our contemporary megachurch makes use of both photography and edited film, as discussed in Benjamin’s writings (Citation1968), but also new digital forms including broadcast, livestream, and real-time interaction. Our findings consistently show the cohesion between the various forms of technology and media used by the church, proving that digital media are not competing with each other, as Benjamin feared they would. Instead, these social media affordances are combined and aligned, built upon existing practices and technology that have worked for the megachurch even before the pandemic. The 2020–21 disruption compelled the church to rely on new interactive forms of digital engagement and media, such as livestream, which maintain KICC’s strategic engagement with its congregants. Such interaction between older and newer media forms is sometimes referred to as ‘remediation’ (Bolter & Grusin, Citation1999), embracing the advantages of media both old and new, and the opportunity to refashion the practices that are ‘already understood and appreciated by those audiences’ (Bolter et al., Citation2006, p. 32). Importantly, these new hybridised practices change the way in which people learn and receive KICC’s traditional values and engage and participate in ritual events. For instance, ritual participatory practices online have now accepted the use of emojis, reaction, folding the avatar’s hands for prayer (Radde Antweiler, Citation2012), and comments in real-time as a form of resonance and response to the pastor’s preaching. Livestream broadcast facilitates synchronous but dispersed engagement, a key quality that film or edited video cannot offer.

As these practices are refashioned, the presence of media and technology becomes ever more a focus of the church experience, and a combination of various digital forms engineers ‘a feeling of fullness’ of experience. Bolter and Grusin (Citation1999) describe this multiplicity as ‘hypermediacy’, explaining how ‘digital hypermedia seek the real by multiplying mediation so as to create a feeling of fullness, a satiety of experience, which can be taken as reality’ (p. 53). Hypermediacy marks a special turn in the perception of aura, moving from concealing the presence of digital media platforms to aligning the logics of the media and the church. Technology has been always part of the tradition of the megachurches. Rituals are open to technological adaptation and transformation, for instance by recorded music being used in an online ritual event or live-comment functionality being recognised as a legitimate way for congregants to respond to the pastor’s presentation.

Constructing digital aura