Abstract

This paper evaluates the resilience of social rental housing in the UK, Sweden and Denmark. Throughout the OECD, processes of retrenchment and privatization, alongside the growth of the owner-occupied and private rental sectors, have led to nigh universal declines in the size and scope of social rental housing. These processes have not transpired evenly, however. Embracing a historical institutionalist approach, alongside novel data and methodology, this paper assesses the variegated patterns of sectoral decline and resilience in these three northern European countries. We find the Danish, association-based model - with its polycentric governance and multi-level system of financing - to have been the most robustly resilient hitherto. In the UK and Sweden, we observe patterns of decline and evidence that the non-profit and needs-based principles which traditionally underpinned these systems have reached precarious thresholds. Nevertheless, despite manifold retrograde threats and vulnerabilities over the past decades, the social rental sectors in Sweden and the UK have proved surprisingly resilient.

1. Introduction

The provision of good quality, accessible and affordable homes is the specified objective of housing policy worldwide, however articulated. And yet, housing has been labelled ’the wobbly pillar under the welfare state’ (Torgersen, Citation1987); ’unique among social programs’ (Pierson, Citation1994:74), constituting both ’a market commodity and a public good’ (Bengtsson, Citation2001:256). Given its unique characteristics, Harloe (Citation1995:2) argues that housing has, ’retained an ambiguous and shifting status on the margins of the welfare state’.

Today, in many countries, social rental housing has, rather unambiguously, been pushed further to the margins of the welfare state. However, despite similar trends, the processes of retrenchment have not transpired evenly. Embracing a historical institutionalist approach, we evaluate the resilience of social rental housing in the UK, Sweden and Denmark, assessing the extent to which they have retained the social character and properties which characterized them during the post-War period.

Following World War II, housing was considered a central pillar of the contract between the state and its citizens (Poggio and Whitehead, Citation2017:2). The variegated forms of social rental housing which developed throughout Europe at this time produced socially equitable outcomes; alleviating the numerical shortfalls produced by war and underinvestment. The overall living standards of mainstream working households improved markedly (Whitehead, Citation2017:4), with social rental housing ‘immeasurably improving the lives of [the] working class’ (Boughton, Citation2018:31), and, ‘…foster[ing] upward mobility’ (Lévy-Vroelant, Reinprecht & Wassenberg, 2008:38).

Nevertheless, social rental housing has come ’under fire’ in recent decades (Tutin, Citation2008:47), and Lau and Murie (Citation2017:271) have argued that debates around social rental housing need to ’grapple with different patterns of decline’. In this article, we respond by examining said patterns in the UK, Sweden and Denmark. Which of these systems have proved most resilient to decline? And which institutional mechanisms have acted most successfully as bulwarks against privatisation, retrenchment, and residualisation?

We select these cases for two reasons. First, all have traditionally operated large social rental housing sectors1. Second, at various times, they have all had a commitment to universalism, i.e., a social rental sector not only directed at households of lesser means.

We argue that a potential component for explaining resilience is the degree of political centralisation governing social rental housing provision, and its financing. As we elaborate, the social rental sector in Denmark, characterized by its polycentric, association-based structure (Larsen & Lund Hansen, Citation2015), and multilevel system of financing, appears to be the most robust system of our three cases. In the UK and Sweden, where social rental housing has traditionally been more centralized and reliant on state funding (local and central), it has, to a larger extent, become prey to processes of retrenchment, residualisation and marginalization.

The paper begins with a theoretical discussion, where we define our central concepts. Following this, we explore the general characteristics of the rental housing systems in our three cases during the post-War era. In Section 4, we discuss the development from these years to the present time, and, building upon this, in Section 5, we apply our theoretical and methodological tools to empirically assess the resilience of social rental housing in our cases. Section 6 concludes and expounds our theoretical and empirical findings.

2. Resilience and social rental housing

Firstly, what do we mean by ‘social rental housing’? How can we assess its performance, and what does ‘resilience’ mean in this context?

We define social rental housing as rental housing that is operated on the basis of meeting housing need and not primarily in order to make profit for the landlord. Even though the role of social rental housing is contested, we do not see this definition as controversial.

We further suggest three basic criteria for assessing the performance of a social rental system, derived from the idea that it should provide affordable and secure housing of good quality, primarily to households that otherwise may be ‘unable to exercise effective demand’ (Oxley, Citation2009:5).

Our first criterion is that social rental sectors should be operated in accordance with an ethos of meeting housing need and on the basis of non-profit principles. Such a housing need/non-profit ethos is what ideal-typically distinguishes social rental housing from private, profit-oriented arrangements.

Our second criterion is that social rental housing should be of good quality in terms of space, equipment, and local environment and ‘produce no negative externalities’ (Oxley, Citation2009:5). We claim that to be successful, social rental housing should have as high, if not higher, standards than what is supplied on the private market.

Our third criterion is that residents should have security of tenure – both formal and real – implying that they are protected from being arbitrarily evicted, but also from rent increases which would, in practice, necessitate them leaving their homes.

Evidently, as we explore, trade-offs exist between these criteria, e.g., the goal of meeting housing need in each of our cases, has, at various times and in the context of budgetary restraints, erred towards the provision of large-scale social rental housing estates where the infrastructure and amenities are poor.

Other aspects are also important, e.g., affordability and non-residualisation, but we do not use them as independent criteria. Instead, we discuss affordability as a possible corollary of the housing need/non-profit ethos. Residualisation within the social housing stock means that, ’those with choice [can] exit the tenure, leaving neighbourhoods comprised of those with least resources and opportunities’ (Jacobs et al. Citation2011:11). In our analysis, we see residualisation as a possible socio-economic cause and/or effect of a deterioration in our three criteria.

Much has been written on resilience with reference to social-ecological systems, but this approach has also been extended to the study of institutions, where it is often related to theories about path dependence and change (Rampp, Citation2019:59). In this tradition, the resilience of systems or institutions depends upon their ’capacity […] to absorb disturbance and reorganize while undergoing change so as to still retain essentially the same function, structure, identity, and feedbacks’ (Walker et al., Citation2004).

To be fruitful, this understanding demands a distinct formulation about what is the institutional core (or identity) of a system. With our definition and three criteria we have tried to pinpoint the core functions and properties of social rental housing. In our analysis, we gauge the extent to which these institutions have been preserved, bolstered, or undermined over time.

It bears noting here that ‘disturbance’ need not be exogenous; it may come in the form of practices and policies. As Streeck and Thelen (Citation2005:19) note, ‘institutions are not only periodically contested; they are the object of ongoing skirmishing as actors try to achieve advantage by interpreting or redirecting institutions in pursuit of their goals’. Thus, the more a social rental sector is able to successfully resist contestations threatening its core functions and properties, the more resilient the sector will be deemed.

Our task in the following sections is to evaluate the extent to which the institutional core (or identity) of the social rental systems in our three cases have changed over time by relating to the criteria suggested above. Has the housing need/non-profit ethos been undermined? Have standards deteriorated? And has tenure security been weakened? The more those elements have retrograded, the less appropriate it will be to talk about resilience.

We also discuss a fourth variable related to resilience: size. Even if a social rental sector has not deteriorated in terms of our three criteria, it could still be said to lack resilience if the sector has diminished considerably in size, giving fewer citizens access to non-speculative housing.

In the following empirical sections, we discuss to what extent these core functions have been resilient in the UK, Swedish and Danish social rental sectors from the post-War years to the present day, adopting a comparative historical approach. Our discussion starts with the unprecedented investments during the immediate post-War decades; continues with the variegated processes of retrenchment from the 1970s henceforth; and rounds up by applying our criteria of non-profit, quality, security of tenure, and size to the present-day situation.

3. The post-War era: Identifying the core functions of social rental housing in post-War Britain, Sweden and Denmark

In this section we highlight the core functions and properties of the respective social rental housing systems in our three cases as they developed during the post-War era.

3.1. United Kingdom

Social rental housing in the UK can be traced back to the mid-19th century. The sector’s growth was initially lacklustre but, following The Housing, Town Planning, &c. Act of 1919, over one million social rental dwellings were built during the interwar years. The building quality was high, and these dwellings catered mainly for the ‘affluent and aspirational working class’ (Boughton, Citation2018:47).

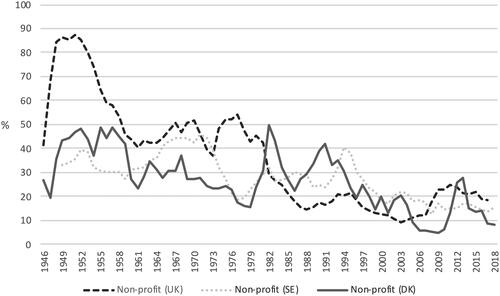

Following 1945, the levers of the UK’s wartime economy were directed towards housing, and local authorities were permitted to borrow from the Public Works Loan Board (PWLB) at favourable rates. Municipal planning was strengthened, and the 1949 Housing Act saw a commitment to ‘general needs’ housing, with high quality housing constructed ‘in unprecedented numbers’ (Lundqvist, Citation1992:17). By the early-1950s, council house completions made up nearly 90 per cent of all housing output (), with the average income of council tenants exceeding the national median (Bentham, Citation1986:161).

Figure 1. Share of non-profit rental housing construction in the UK, Sweden and Denmark in relation to all completions, 1946–2018.

Sources: Ministry of Housing, Communities & Local Government (Citation2019c; Citation2020); Statistics Sweden (Citation1958; Citation2004; Citation2019); UN (Citationvarious years); Statistics Denmark (Citation2019).

While these impressive building programmes continued apace, the seeds of the protracted demise of universalism were sown as early as the mid-1950s (Malpass, Citation2004). Subsidies for ‘general needs’ housing were reduced, restrictions on private housing construction lifted, and quantity became the watchword. The Conservatives introduced Right-to-Buy-style legislation in 1952, and a graduated system of subsidies incentivizing high-rise construction (Boughton, Citation2018:107). Council house sales were initially modest, however, and access to this sector formally remained universal.

3.2. Sweden

Sweden’s first social rental municipal housing companies (MHCs) date back to the late-1910s, but it was not until the 1930s, and particularly the 1940s, that MHCs became entrenched within government housing policy. Following World War II, the Social Democrats laid the foundations for the universal housing policy which, rhetorically at least, has been dominant ever since, with MHCs, allmännyttan, functioning as the mainstay.

In the 1940s, a housing finance system with state loans directed towards all tenure forms was established. MHCs had, in the 1930s, been tasked with the ‘selective’ undertaking of providing housing for large families of limited means but were now given their present role of providing housing for all. They were expected to forestall speculation in the rental market and make housing production and management less sensitive to market fluctuations, with the 1947 Building and Planning Act augmenting municipal capacities to achieve these goals. The universal role of MHCs was also the basis of the integrated rental market (Kemeny, Citation2005), whereby private and public housing were, in principle, to compete for the same households.

The nationwide shortage of affordable housing persisted, however, and it was only with the Million Programme 1965–74 that housing deficit turned to surplus. Yet, as Hall & Vidén (Citation2005) note, many large-scale rental housing estates had ‘a desolate external environment’ (ibid.:303), and ‘vicious spirals of increasing management problems, vacancies and segregation developed shortly after completion’ (ibid.:313).

The wartime ‘provisional’ Rent Control Act of 1942 combined rent regulation with direct security of tenure and was largely based on corporatist representation. The Rent Control Act survived until 1978, when new legislation further institutionalized the unique Swedish system of collective rent-setting.

3.3. Denmark

As in the UK, social rental housing in Denmark dates back to the 19th century. However, it was not until 1919 that the Joint Organization of Non-profit Danish Housing Companies was formed (BL, 2019) and during the inter-War and post-War years the state provided low-interest loans to these non-profit housing concerns (Larsson & Thomassen, Citation1991:21). Following the 1946 Housing Subsidy Act and the 1949 Regulation of Built-up Areas Act, social rental building activity increased apace ().

Unlike in the UK and Sweden, where local authorities took command of social rental provision, Danish social rental housing (almene boliger) took the form of association-based models (Larsen & Lund Hansen, Citation2015). The housing associations maintained financial independence; they were, and remain today, independent but publicly subsidized and regulated. The National Building Fund (Landsbyggefonden) was established in 1967 to promote self-financing but, despite its name, this was (and remains) a private fund that is financed by tenants’ rent contributions and borrowing on capital markets, supported by municipal base capital and state guarantees (BL, 2019).

Prior to 1958, around 75% of social rental housing construction was assisted by state loans, but by the mid-1970s, that figure was down to 17% (Esping-Andersen, Citation1985:186). Despite this, approximately one quarter of the 800,000 housing units that were constructed throughout Denmark during the 1960s and 1970s were social rental (Bech-Danielsen & Christensen, Citation2017:18).

All housing associations are managed through so-called ‘tenant democracy’. Local tenants elect the boards of the individual estates, and their representatives elect a board for the entire organization (BL, 2019). Access to this sector is formally universal, but municipalities have the right of disposition over one quarter of the housing units (Larsen & Lund Hansen, Citation2015:268), integrating a means-tested component, which has become more pronounced since the 1980s (Scanlon & Vestergaard, Citation2007:3).

***

This section has highlighted the attributes which characterized social rental housing in each of our countries during the post-War era. In each case, the commitment to meeting housing needs was strong and underpinned by non-profit principles. The accommodation provided security of tenure and was generally of comparatively good quality in terms of space, equipment, safety and physical environment; although this can be said to have deteriorated in the UK from the 1960s onwards and in Sweden, in terms of local environment, in some Million Programme estates. In Denmark, some of the suburban high-rise estates were lacking in physical and environmental qualities (Vestergaard, Citation2004), but in all three countries, these sectors grew robustly, albeit at different tempos.

4. Post-1960: Patterns of decline and resilience

During the 1970s, social rental housing was exposed to several structural and political threats in all three countries. In the context of sclerotic economic growth, rising inflation, and significant current account deficits, the era of social rental decline had begun (Harloe, Citation1994:47).

4.1. United Kingdom2

In the UK, social rental housing continued to be built throughout the 1970s, but political and public support for the sector had waned. Under a two-party system, the dynamics of British housing policy resembled a pendulum motion of reduced subsidies under the Conservatives and increased subsidies under Labour.

At no other time had the vulnerability of this sector been so exposed as during the 1980s. The introduction of Right-to-Buy was combined with restrictions on council borrowing; giving tenants the option to choose their landlords; and the ‘ring fencing’ of Local Housing Revenue Accounts which ‘prohibit[ed] cross-subsidizing new production from rent receipts’ (Lundqvist, Citation1992:35). Private, non-profit housing associations became the preferred option of housing investment under Margaret Thatcher, and the generosity of rent allowances and supply-side subsidies were reduced across the board.

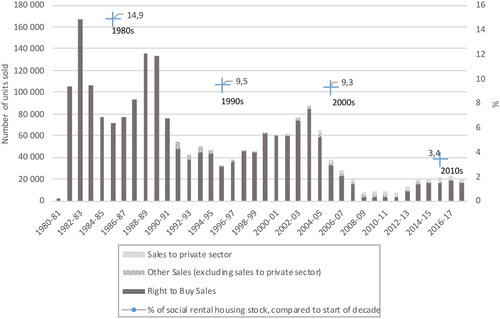

Pierson (Citation1994:78) notes that the Thatcher government’s housing record was defined by the promotion of owner occupation, the restructuring of housing subsidies to marginalize the public sector; and the attempt to reinvigorate the private rental sector. Some of these processes were evident prior to the 1980s, but Right-to-Buy, supported by heavy discounts, and the lifting of mortgage lending ceilings, resulted in nearly one million social rental housing units being transferred to sitting tenants in England alone during the 1980s ().

Figure 2. Sales of social rental housing in England by type of sale (absolute figures) and as % of social rental stock at the start of the decade (base years = 1980; 1990; 2000; 2010).

Source: Ministry of Housing, Communities & Local Government (Citation2018)

The sector was undermined by centralized political decision-making during the 1980s and 1990s, and the policies which had undermined it were not reversed with the election of a Labour government in 1997. In 1980, nearly 1 in 3 Britons lived in social rental housing. By the year 2000, that figure was 1 in 5.

4.2. Sweden

In Sweden, the mid-1970s marked the terminus of the Million Programme. While it was expectation that high volumes of housing production would continue (Hall & Vidén, Citation2005:321), demand for rental apartments ‘drastically reduced’ (ibid.). Assisted by increased mortgage liquidity, higher wages, and generous mortgage interest tax deductibility ‘…the middle classes began to flee from municipal residences’ (Sejersted, Citation2011:264).

We witness a slight revival in social rental construction during the 1980s, although 21,200 units were sold. While such volumes were trifling compared to the UK at this time, it was merely a prelude. Social rental housing production was curtailed significantly following the early-1990s Banking Crisis, which signalled the end of the subsidy model which had endured throughout the post-War era hitherto. By 1994, some 60% of social rental housing tenants were drawn from the lowest two income quintiles (Borg, Citation2019), and that figure would increase steadily henceforth, with the sector becoming more residual and segregated (Andersson & Kährik, Citation2016:127).

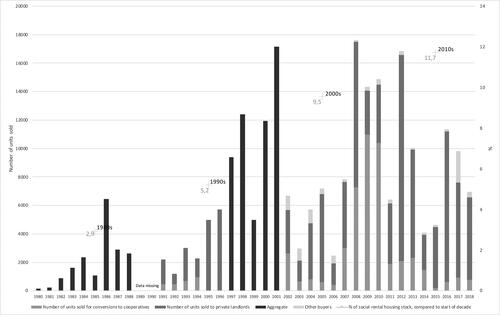

Following legislation in 1992, conversions of social rental housing at discounted rates abounded (), increasing residential segregation (ibid.). Furthermore, in 2011, legislation was introduced forcing MHCs to operate on the basis of ‘business-like principles’. Consequently, many MHCs set up minimum income requirements for tenants. While there is still no formal system of means-testing for the municipal social rental sector, there has been a growth in ‘social contracts’, whereby municipal social services sublet apartments (Grander, Citation2017:338). As Stephens (Citation2015) notes, these are often managed as a kind of ‘probationary tenancy’, with requirements for tenants to meet employment or training obligations, thus representing both a residual and demeaning form of tenancy.

Figure 3. Sales of social rental housing in Sweden by type of sale (absolute figures) and as % of social rental stock at the start of the decade (base years = 1980; 1990; 2000; 2010).

Sources: Elander (Citation1991) and Boverket (Citationvarious years)

In recent years, major renovations in combination with considerable rent increases (‘renovictions’) have been used, both by private and public landlords, as an instrument to circumvent the security of tenure formally afforded by Sweden’s rent-setting system; thus making it possible to raise rent levels and displace tenants (Boverket Citation2014). With a diminishing stock due to sales to private investors, as well as conversions to cooperatives (), the role of Swedish rental housing has, in practice, become more residual.

4.3. Denmark

Throughout much of the 1980s and early 1990s, the proportion of social rental housing construction was higher in Denmark than in the UK and Sweden. The growth of the sector was robust between the 1980s and 2000s. At the same time, however, the sector has become more selective. Despite various attempts to implement Right-to-Buy-style legislation, none of these have been particularly successful (Kristiansen, Citation2007; Larsen & Lund Hansen, Citation2015), and the association-based structure, embedded in ‘tenant democracy’, has been pointed out as a core explanation here (Nielsen, Citation2010; Bengtsson and Jensen, Citation2020).

Unlike in the UK and Sweden, mortgage credit was heavily regulated throughout much of the 1980s (Wood, Citation2019:841) and, despite a series of regulatory reforms from 1989 onward, which would see robust mortgage credit growth (ibid.), homeownership increased modestly between the 1980s and 2010s, while the proportion of Danes living in social rental housing steadily increased.

While the subsidy system in Denmark was more modest than in the UK and Sweden, it remains intact today, in the form of municipal base capital and credit guarantees. These features, coupled with the sector’s independence and a stable system of bond-based housing finance, have been core components of the relative resilience of the Danish social rental model.

***

During the final decades of the twentieth-century, we witness several retrograde threats to the social rental sectors in out three cases, including: deterioration in tenure security; threats to the non-profit structure; and stock transfers. Subsidies moved decidedly from supply-side support of social rental construction to housing allowances, help-to-buy subsidies, and mortgage interest tax deductions. As a result, far fewer social rental homes were built following the 1980s, making the systems, in practice, more residual. All of these features were more evident in the UK and Sweden than in Denmark.

Still, the comparatively strong path dependence mechanisms of efficiency, legitimacy and power in housing institutions (Bengtsson & Ruonavaara, Citation2010) made the systems more resistant than might have been expected (see Bengtsson & Jensen, Citation2020 on Denmark and Sweden, and Malpass, Citation2011 on the UK).

Households became less credit constrained from the 1970s onward in the UK and Sweden and from the 1990s in Denmark, making owner-occupation more accessible to middle-class households. In Denmark, nevertheless, the social rental housing sector continued to grow following the 1980s.

5. Gauging decline and resilience

In this section, we apply our criteria developed in Section 2 in order to evaluate the trajectories of decline and/or resilience in our cases.

5.1. Housing need/non-profit ethos

The needs-based component of social rental housing provision in our cases has undergone profound change over the past 70 years. During the 1950s, all three systems were largely universal, but we see a drift towards selectivity, first in the UK, and later in Sweden and Denmark.

Technically, to this day, there exist no formal income limits for accessing social rental housing in these three countries, but all have erred towards more selective systems over the past decades. However, and crucial to our definition, historically these systems have been largely off market, and thus the price mechanism has not been the principal factor determining whether a household is able to access social rental housing. Instead, local supply/availability and waiting lists have, to a large extent, fulfilled this role.

In the UK, selectivity varies between municipalities based on a variety of ‘priority’ criteria, as well as the demand for, and supply of, social rental housing locally. Formally, any British citizen who has been ‘habitually resident’ can be placed on the housing register. However, the varying allocation systems usually favour those with urgent housing needs (Shelter, 2021).

In Sweden, while there are no formal criteria for social rental housing allocation, those from the lowest two income quartiles are significantly overrepresented (Borg, Citation2019). Further, since 2011, MHCs have shown a preference for selecting wealthier households, setting minimum income thresholds for tenants, whilst using ‘social contracts’ as a means to house more disadvantaged households (Grander, Citation2017).

The Danish system blends selectivity and universalism. Municipalities allocate 25% of social rental units, but most vacancies are distributed via waiting lists. In sum, the notion of needs-based social rental housing is clearly more of a residual, selective one today than it was during the immediate post-War decades, and universalism has been eroded across the board, albeit to a lesser extent in Denmark.

To assess outcomes in terms of need fulfilment, we have to look to overall rental housing due to a lack of disaggregated data on Sweden and Denmark; note, however, that the allocation policies of the large social rental sectors in these countries can be expected to have spill-over effects on private rentals. Here we focus on two core elements at the national level: affordability and overcrowding (Bramley et al., Citation2010).

There is a remarkable degree of congruence between the median rent burden as a share of disposable income of the bottom income quintile in each of our cases (OECD, Citation2019). Between 2010 and 2018, the average median burden of rent payments as a share of disposable income for tenant households drawn from this quintile was consistently higher in Sweden (over 40%) than in the UK (39%) or Denmark (35%) (ibid.). Rental housing, irrespective of whether it is public or private, is among the most expensive in the OECD in our three cases (relative to incomes in the aforementioned quintiles) and those at the lower end of the income distribution are affected disproportionately. One could question, therefore, the efficacy of social rental housing in lowering the cost burden for poorer households, and whether the needs-based component of social rental housing is robust today.

Among renters in the lower income distribution, overcrowding is most pronounced in Sweden (OECD, Citation2019). Indeed, at the aggregate level, Sweden’s rental housing system is failing many of the poorest households, with 40% of tenants in the bottom income quintile defined by Eurostat and the OECD as living in overcrowded conditions, compared to around 25% in Denmark and 10% in the UK (OECD, Citation2019).

***

The non-profit principle has witnessed marked changes since the late-20th century, particularly in the UK and Sweden. MHCs in Sweden are required, since 2011, to operate in accordance with business-like principles and generate surpluses. While the surplus produced must be recycled through the municipality, this has eroded the non-profit component of social rental provision and the ability to meet general needs; particularly those of poorer households. As Baeten et al. (Citation2017:638) note, ‘the housing stock which remains in the hands of city is increasingly used to trigger profits used for non-housing purposes’. While rents are, on average, lower in the social rental housing stock than the private (SCB, 2019), this ongoing development has the potential to undermine the system.

In the UK, the social rental housing system has bifurcated over the past few decades, with the non-profit housing associations becoming the largest providers. Today, local council housing comprises merely 6.7% of the housing stock in England (1.59 million units), and housing associations, comprise 10.5% (2.59 million units) (Preece et al. Citation2020:1216). Both must reinvest surpluses, as in Sweden. However, following policy changes in 2011 under the Conservative-led coalition, capital spending on housebuilding was cut by two-thirds (FT, 2014), and the government allowed social rental landlords to charge ‘affordable rents’ instead of ‘social rents’ − 80% of market rents instead of (circa) 60%. This has eroded the non-profit model but, notably, 98.9% of the social rental dwellings operated by councils still apply social rents (MHCLG, 2019a).

The government recently introduced a one percentage point increase on PWLB loans, which councils have been using increasingly to build new social rental housing (Butler, Citation2019). While the non-profit principle remains in principle, then, the conditions of financing (as in Sweden) have deteriorated, increasing the costs for non-profit entities, which inevitably affects both supply and rents; and thus, impacting on affordability.

The recent erosion of the non-profit models in Sweden and the UK has not been matched in Denmark. Social rental housing in Denmark operates according to the so-called balancing principle. Rents must cover operating and maintenance costs, as well as capital expenditure (Rogaczewska, Citation2017). Thus, income and expenditure must balance out, and no surplus should be extracted. This has been intrinsic to the Danish association-based model since its inception, and there are currently few incentives (legal or otherwise) to extract a surplus from the social rental housing stock.

This principle is also mirrored in the financing of Danish social housing with the match funding principle which ensures a balance between the mortgage a borrower assumes and the bonds which the mortgage institute emits to finance said loan; thus limiting both liquidity and risk (Rogaczewska, Citation2017). 88% of the cost of new dwellings has typically been financed on ‘normal market terms’ via the mortgage institutes (ibid.) with the municipalities providing interest-free base capital (10%) and tenants’ deposits covering the rest (2%). Such a regime, by providing social rental housing associations secure and long-term finance, has helped to bolster the non-profit principles and need-based component. Indeed, rents in the private rental system have been calculated to be 37% higher per square metre than the social rental sector (Kristiansen, Citation2007:34).

5.2. Standards and quality

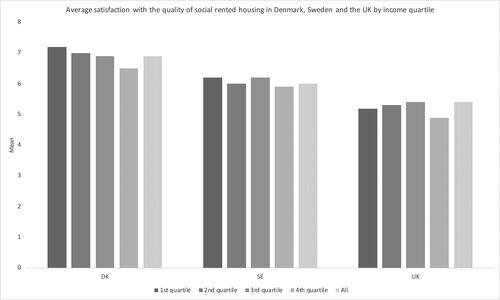

The data on perceived quality presented in , below, are derived from the European Quality of Life Survey, which breaks down respondents’ satisfaction ratings (on a scale of 1 − 10) by income quartile. The questions asked are consistent across our three cases and refer to the social rental housing forms explored in this paper (Eurofound, Citation2016a). In Denmark, those within the lower income quartile are most satisfied with the quality of social rented housing, with Swedes from the first and third quartiles both expressing higher than average levels of satisfaction.

Figure 4. Average satisfaction with the quality of social rented housing in Denmark, Sweden and the UK by income quartile (2016).

Source: Eurofound, Citation2016b

Unfortunately, we can only trace these same questions back to 2011 but this survey reveals that overall satisfaction across the income spectrum has remained steady in Denmark and Sweden (Eurofound, Citation2012). There has been a decline in satisfaction in the UK over a five-year period, however, where the mean satisfaction score has declined from 6 in 2011 (ibid.) to 5.4 today.

Beyond the EQLS, we have to rely on rather disparate data sources. In England using energy efficiency (SAP) as a proxy for building quality, social rental housing typically performs much better than private rented or owner-occupied dwellings (DCLG, 2010:100; 2012). For Sweden, broad surveys from 2005, 2010 and 2015 of tenants’ attitudes in to different aspects of their housing and housing management show consistently higher values for social than private sector tenants (Hyresgästföreningen, Citation2017), and similar patterns have been found to exist in Denmark (Till, Citation2005:169). Judging from this somewhat heterogeneous material, the standards and quality of social rental housing have been consistently better than the private rental sector over time.

5.3. Security of tenure

In England, formal security of tenure has been eroded in recent years. Since 2012, social rental landlords in England have been given powers not to offer 'lifetime' tenancies to new tenants (Wilson, Citation2018:16). This did not have much impact, however, with only 15% of social housing tenancies let on a fixed term basis by councils in 2014 and 2015 (ibid.). The Housing and Planning Act 2016 attempted to restrict councils’ ability to offer long-term tenancies (ibid.), but this was later abandoned. Furthermore, the lowering of housing allowances and the so-called Bedroom Tax has hit the poorest tenants’ real security of tenure hard. Social rental tenants had their benefits reduced by between 14% and 25% according to whether they had one or (≥) two spare bedrooms (Butler and Siddique, Citation2016), and a study by the National Housing Federation in 2014 found that two-thirds of the 523,000 affected tenants had fallen into arrears (Morrison, Citation2017:472-473).

In Sweden, rental legislation has given tenants with a first-hand contract strong formal tenure security, while the rent-setting system has provided real security of tenure. However, loopholes in this system have made it possible for landlords to raise rents significantly; most prominently the aforementioned possibility of considerable rent increases in cases of major renovations: so-called ‘renoviction’. The growing marketization of Swedish MHCs has also contributed to expanding markets for second-hand renting and black markets for rental dwellings, alongside the above-mentioned ‘social contracts’ with the municipal social service as economic guarantee. In all these forms of rental housing, the tenants’ security of tenure is seriously undermined both in formal and real terms.

While changes in formal and real tenure security have been marked in the UK and Sweden, no comparable deterioration is observable in Denmark (Larsen & Lund Hansen, Citation2015). While rents can be increased following renovations, this is not imposed top-down, as in the case of Sweden, and local tenants have a very large say about the forms these renovations take. As a report into tenancy law notes, ‘[t]he tenants’ rights with regard to social dwellings are […] based on the view that, through a number of legal bodies, the tenants to a great extent are the landlords and take decisions as to how the dwellings in which they live should be managed’ (Juul-Sandberg, Citation2014:20). Further, renovations and developments in the existing stock are usually supported by the National Building Fund (BL, 2019), so costs are pooled.

We have to caveat the above assessment on security of tenure in Denmark, however. As part of a recent so-called Ghetto package, proposals have been put forward to ‘change the composition of residents and housing in exposed residential areas’. A ghetto area is defined as ‘a residential area with at least 1,000 residents, where the proportion of immigrants and descendants from non-Western countries exceeds 50 per cent’ and where other criteria such as educational levels, crime and income are factored in (Danish Transport Ministry, Citation2018, authors’ translation). The law, legislated in 2018, implies that ‘rental rules are tightened and that recipients of certain transfer income are not allowed to move into the toughest ghetto areas’. Further, it ‘extends the rules governing the sale and demolition of properties that include social rental housing’ (Danish Parliament, Citation2018). Such a move can force social rental housing associations in areas designated as ‘severe ghettos’ to ‘reduce the share of non-profit housing stock to 40% through relabelling, demolition and sale of buildings’ (Olsen, Citation2019).

The distribution of immigrants over the country and between social housing estates is highly uneven and, thus, this legislation is designed to target specific estates. Regardless, such legislation has the potential to undermine the Danish model of social rental housing.

5.4. Size and residualisation

In the UK and Sweden, the social rental sector has diminished considerably in size due to sales, conversions and decreasing newbuild activity. The implications of a considerably reduced social rental housing stock due, in part, to conversions, are clear: overrepresentation of the lowest income groups in the social rental sector and increased segregation.

One could make the case that, due to the concentration of poorer households residing in social rental housing, such a system is perhaps better targeting those who can least serve their housing needs independently. In our perspective, however, a social rental sector lacks resilience if it has diminished considerably in size, thereby giving fewer citizens access to non-speculative housing.

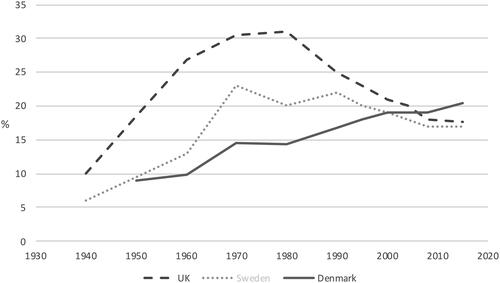

We witness different trajectories in our three cases. As we saw in Section 3, the share of social rental housing production in all three countries is presently at or around their historic lows. Relative and absolute declines in the stock of social rental dwellings () are visible since the 1970s in the UK and Sweden, but not in Denmark.

Figure 5. Social rental dwellings as proportion of total dwelling stock, 1940–2015.

Sources: Ministry of Infrastructure of the Italian Republic (Citation2006); Dol and Haffner (Citation2010); Turner (Citation1997); Det økonomiske Råd (Citation2001:234); Landsbyggefonden (Citation2018); Ministry of Housing, Communities & Local Government (Citation2019b); Sveriges Allmännytta (Citation2019); Statistics Sweden (Citation2019).

To understand these variegated trajectories, we return to the three components, which Pierson identified in relation to Thatcherite housing reforms: Firstly, right-to-buy never took off in Denmark, and the share of social rental housing has not decreased as it has in the UK and Sweden. Secondly, the social rental sector in Denmark is not ‘public’. It is association-based and the subsidy system is less reliant on central government financing and subsidies. Thirdly, the private rental stock has consistently diminished in size since the 1980s in Denmark, contra Sweden where it has remained relatively stable and, the UK, where the private rental sector has experienced robust growth since 2000.

In both Sweden and (particularly) the UK, the size of the social rental stock has been reduced due to sales and conversions, which has led to a more selective and residualized sector. However, seen in an international perspective, the sectors are still large, and the size as such of the remaining stock in both countries should not be an obstacle to the functioning of a social rental housing system based on our three criteria.

***

Our final task in this section is to assess the mechanisms which have promoted the variegated outcomes explored here. First, as others have argued (Larsen & Lund Hansen, Citation2015), the association-based model of social rental housing in Denmark – and its long-standing independence and tenant control – has certainly buffered the Danish social rental system from both structural economic change and the ’fluctuating political vogues [of] privatisation’ (Jensen, Citation1997). The differences in outcomes in terms of conversions and subsidy cuts between Denmark and our other two cases attest to this.

Second, the funding regime in both Sweden, and particularly the UK, has been erratic. In both countries, these systems developed historically with a large and, in retrospect, unhealthy reliance on government funding (Harloe & Paris, Citation1984:75); making them vulnerable to retrenchment (Pierson, Citation1994). If the financial basis of constructing social rental housing is unpredictable, and not oriented towards stable long-term investment, then borrowing costs will likely rise over time (Oxley, Citation2009:25) and the sector will suffer. In contrast, the Danish social rental housing sector has secured funding with low interest rates and long maturities, where limited grants, loan guarantees and the pooling of risk play an important role.

The decentralised, multi-layered nature of the Danish social rental model can be seen to correspond to a ‘polycentric governance system’ (Ostrom, Citation2001), consisting of ‘small-, medium- and large-scale democratic units that each may exercise considerable independence to make and enforce rules within a circumscribed scope of authority’ (ibid.). In such systems, according to Ostrom, ‘the smallest units can be viewed as parallel adaptive systems that are nested within ever-larger units that are themselves parallel adaptive systems’ (ibid.). We suggest that the adaptive nature of these nested democratic units may help to explain the relative resilience of the Danish system, although a more granular approach would be required to test this hypothesis robustly.

6. Concluding discussion

Before we conclude, we provide a brief summary of our findings along the criteria we adopted.

First, central to what constitutes social rental housing is that it should be operated on the principle of meeting general housing needs and in accordance with non-profit principles. Formally, all our studied systems are universal, but, in practice, social rental housing has become more selective since the 1970s. In Sweden, MHCs’ minimum income requirements, and, in the UK, the ‘Affordable Rents’ principle could severely undermine the needs-based ethos. However, these practices are still far from universally implemented, so it is still too early to gauge whether they will terminally undermine the needs-based and non-profit components of social rental housing.

The non-profit principle has also been undermined in the funding of the social rental sector both in the UK and Sweden. The centralized nature of the systems in the UK and Sweden made their social rental housing sectors vulnerable (Pierson, Citation1994); as was shown when subsidies were slashed during the 1980s and 1990s. Again, the Danish housing associations are much less reliant on government financing and the terms of borrowing have proved favourable and stable as a result.

In terms of standards and quality the social rental housing stock has proven generally resilient. The standards have been consistently better than the private rental sector, and this dimension has proven to be the most robust feature in each of our three cases, despite concerns over local-environmental quality.

In the UK, there were attempts to undermine formal security of tenure but, so far, these have had limited effects. Likewise, in Denmark, attempts to undermine security of tenure had very limited success. In Sweden, there have been few such attempts, but, in practice, security of tenure has been undermined via the process of ‘renoviction’ and the growth of secondary contracts.

In Sweden and the UK, the size of the social rental stock has been reduced, which has led to a more residualized sector. However, the sectors are still large, and the present size as such should not be an obstacle to a central role for social rental housing based on our three criteria. We summarize our main findings in , below.

Table 1. Gauging social rental housing resilience from the post-War era to the present day.

***

Has our approach been fruitful? Sjöstedt makes an important point when claiming that, ‘if path-dependent institutions persist in the absence of the forces responsible for their creation, resilience thinking needs to pay closer attention to the mechanisms of reproduction rather than assuming stability and rigidity or only focusing on external sources of change’ (Sjöstedt, Citation2015). With the housing shortages of yesteryear built away after the 1960s, higher median wages, and broadened access to housing finance, the forces behind the creation of social rental housing had been severely weakened by the 1970s. Aided and abetted by homeownership-friendly policies, these sectors became vulnerable to privatisation and retrenchment (cf. Jensen, Citation1997). The extent to which they have suffered though, has varied, with the Danish system proving, hitherto, more resilient than the systems in the UK and Sweden due, we suggest, to its institutionally decentralised, multi-layered nature and associated independence from central government control.

It is interesting to note that, based on our three cases, whether a rental system is labelled dualist or integrated (Kemeny, Citation2005), seems to matter little as to whether its social rental sector can buffer retrenchment. We have observed how subtle changes have meant that countries have successively moved away from these ideal types (cf. Stephens, Citation2016; Blackwell & Kohl, Citation2019). The resilience framework developed here, then, could have the potential to enrich our understandings of (non)variations in social rental systems in other contexts too, but this is a matter for future research.

The core properties and functions of the institutions of social rental housing are still upheld in a considerable part of the social rental housing stock in each of our cases, but the threats are more severe in the UK (particularly England) and Sweden than in Denmark. And yet, while these systems have proven to be vulnerable in the former two, they have also exhibited surprising levels of resilience. The social rental stock has been reduced markedly in both countries, and the scale of sales has led to a more selective and residualized sector, but this should not shroud the fact that the remaining stock is still of considerable size and quality and continues to have an important social function. The quality is higher, and rents are lower than in the private rental sector, and security of tenure is largely robust. As Grander (Citation2019:387) notes of Sweden: the ‘potential to retain the undertaking of ‘good housing for all’ still exists, but it is unevenly actualized’; and the same could be said about the UK. The systems in these two countries are arguably at a crossroads, but if history is any guide, then both countries may do well to seek inspiration from Denmark’s polycentric, tenant-led model in order to secure the future of their social rental housing systems.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Henrik Gutzon Larsen, Emma Holmqvist, Marie Rosberg, Per Törnqvist,Eszter Sandor, and three annonymous referees for their constructive engagement with the topics discussed in this paper. The usual disclaimers apply.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was provided by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 As Lau and Murie (Citation2017:273) note, ‘[e]xplanations for the resilience of public housing are unlikely to be informed by reference to countries where this tenure always played a minor part’.

2 Following the devolution Acts of the late 1990s, there has been a divergence in housing policy between the devolved regions in the UK (Stephens, Citation2019) and thus the focus of the article henceforth will primarily be England, unless stated otherwise.

References

- Andersson, R. & Kährik, A. (2016) Widening gaps: Segregation dynamics during two decades of economic and institutional change in Stockholm, in: Tammaru, T., Marcinczak, S., van Ham, M., & Musterd, S. (Eds) Socio-economic Segregation in European Capital Cities (London: Routledge).

- Baeten, G., Westin, S., Pull, E. & Molina, I. (2017) Pressure and violence: Housing renovation and displacement in Sweden, Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 49, pp. 631–651.

- Bech-Danielsen, C. & Christensen, G. (2017) Boligområder i bevaegelse Fortaellinger om fysiske og boligsociale indsatser i anledning af Landsbyggefondens 50 års jubilaeum (Copenhagen: Landsbyggefonden). [online] https://lbf.dk/om-lbf/publikationer/boligomraader-i-bevaegelse/sanering-byggeboom-og-omraadeloeft/byggeboom-og-sanering-1967-1973/#sectionLink1 (accessed 1November 2019).

- Bengtsson, B. (2001) Housing as a social right: Implications for welfare state theory’, Scandinavian Political Studies, 24, pp. 255–275.

- Bengtsson, B. & Jensen, L. (2020) ‘Unitary housing regimes in transition – comparing Denmark and Sweden from the perspective of path dependence and change’. [online] http://uu.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1463975/FULLTEXT01.pdf (accessed 4December 2020).

- Bengtsson, B. & Ruonavaara, H. (2010) Introduction to the Special Issue: Path dependence in housing’, Housing, Theory and Society, 27, pp. 193–203.

- Bentham, G. (1986) Socio-tenurial polarization in the United Kingdom, 1953–83: The income evidence’, Urban Studies, 23, pp. 157–162.

- BL ( 2019) ‘The Danish social housing sector’. [online] https://bl.dk/in-english/ (accessed 3October 2019).

- Blackwell, T. & Kohl, S. (2019) Historicizing housing typologies: Beyond welfare state regimes and varieties of residential capitalism’, Housing Studies, 34, pp. 298–318.

- Borg, I. (2019) Universalism lost? The magnitude and spatial pattern of residualisation in the public housing sector in Sweden 1993–2012, Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 34, pp. 405–424.

- Boverket (2014) Flyttmönster till följd av omfattande renoveringar (Karlskrona: Boverket).

- Boverket (various years) Bostadsmarknadsenkäten Del 3 – Allmännyttan (Karlskrona: Boverket).

- Bramley, G., Pawson, H., White, M., et al. (2010). Estimating Housing Need. (Research Report. London: Department of Communities and Local Government).

- Boughton, J. (2018) Municipal Dreams: The Rise and Fall of Council Housing. (London: Verso).

- Butler, P. (2019) Government accused of wrecking plans to build more social housing. The Guardian. 11th October.

- Butler, P. & Siddique, H. (2016) The bedroom tax explained. The Guardian. 27th January.

- Danish Transport Ministry (2018) Ny Ghettoliste [online] https://www.trm.dk/nyheder/2018/ny-ghettoliste/ (accessed 9 November 2019).

- Danish Parliament (2018) L 38 Forslag til lov om aendring af lov om almene boliger m.v., lov om leje af almene boliger og lov om leje [online] https://www.ft.dk/samling/20181/lovforslag/L38/index.htm (accessed 1 November 2019).

- Det økonomiske Råd (2001) Dansk Økonomi, forår 2001 (København: Det økonomiske Råd).

- Dol, K. and Haffner, M. (Eds). (2010) Housing Statistics in the European Union 2010. (The Hague: Ministry of the Interior and Kingdom Relations).

- Elander, I. (1991) Good dwellings for all: The case of social rented housing in Sweden, Housing Studies, 6, pp. 29–43.

- Esping-Andersen, G. (1985) Politics Against Markets: The Social Democratic Road to Power (New Jersey: Princeton University Press).

- Eurofound (2012) European Quality of Life Survey 2011 ’How would you rate the quality of social housing services in your country? [online] https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/data/european-quality-of-life-survey-2011?locale=EN&dataSource=3RDEQLSNEW&media=png&width=740&question=Y11_Q53f&plot=heatMap&countryGroup=linear&subset=Y11_Agecategory&subsetValue=All&answer=Mean (accessed 24 February 2020).

- Eurofound (2016a) European Quality of Life Survey 2016 [Glossary] Unpublished.

- Eurofound (2016b) European Quality of Life Survey 2016 [online] https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/data/european-quality-of-life-survey (accessed 24 February 2020).

- Grander, M. (2017) New public housing: A selective model disguised as universal? Implications of the market adaptation of Swedish public housing, International Journal of Housing Policy, 17, pp. 335–352.

- Grander, M. (2019) Off the beaten track? Selectivity, discretion and path-shaping in Swedish public housing, ’ Housing, Theory and Society, 36, pp. 385–400.

- Hall, T. & Vidén, S. (2005) The Million Homes Programme: A review of the great Swedish planning project’, Planning Perspectives, 20, pp. 301–328.

- Harloe, M. & Paris, C. (1984) The decollectivisation of consumption, in: Szelenyi, I. (Ed) Cities in Recession: Critical Responses to the Urban Policies of the New Right (Vol. 30), 70–98 (London: Sage Publications).

- Harloe, M. (1994) The social construction of social housing’, in: Danermark, B. and Elander, I. (Eds) Social Rented Housing in Europe: Policy, Tenure and Design, 37–52 (Delft: Delft University).

- Harloe, M. (1995) The Peoples’ Home? Social Rented Housing in Europe & America (Oxford: Blackwell).

- Jacobs, K., Arthurson, K., Cica, N., et al. (2011). The Stigmatisation of Social Housing: Findings from a Panel Investigation (Melbourne: Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute).

- Jensen, L. (1997) Stuck in the middle? Danish social housing associations between state, market and civil society, Scandinavian Housing and Planning Research, 14, pp. 117–131.

- Juul-Sandberg, J. (2014) National Report for Denmark, Tenancy Law and Housing Policy in Multi-level Europe (TENLAW) (Bremen: University of Bremen).

- Kemeny, J. (2005) The “Really Big Trade‐off” between home ownership and welfare: Castles' evaluation of the 1980 thesis, and a reformulation 25 years on, Housing, Theory and Society, 22, pp. 59–75.

- Kristiansen, H. (2007) Housing in Denmark (Copenhagen: Centre for Housing and Welfare Research).

- Landsbyggefonden (2018) Omfanget af denalmene bolig-sektori kommunerne 2015-2018. Temastatistik 2018:8 [online] https://lbf.dk/media/1554865/temastatistik-omfang-endelig.pdf (accessed 29 November 2019).

- Larsen, H.G. & Lund Hansen, A. (2015) Commodifying Danish housing commons, Geografiska Annaler. Series B. Human Geography, 97, pp. 262–274.

- Larsson, L. & Thomassen, O. (1991) Urban planning in Denmark, in: Hall, T. (Ed) Planning and Urban Growth in the Nordic Countries (Abingdon: Taylor & Francis).

- Lau, K.Y. & Murie, A. (2017) Residualisation and resilience: public housing in Hong Kong, Housing Studies, 32, pp. 271–295.

- Lundqvist, L.J. (1992) ‘Dislodging the welfare state? Housing and privatization in four European nations’. Housing and Urban Policy Studies 3 (Delft: Delft University Press).

- Malpass, P. (2004) Fifty years of British housing policy: Leaving or leading the welfare state? European Journal of Housing Policy, 4, pp. 209–227.

- Malpass, P. (2011) Path dependence and the measurement of change in housing policy, Housing, Theory and Society, 28, pp. 305–319.

- Ministry of Housing, Communities & Local Government (2018) Table 678: Social housing sales: Annual sales by scheme for England: 1980-81 to 2017-18 [online] https://www.gov.uk/government/statistical-data-sets/live-tables-on-social-housing-sales (accessed 22 July 2019).

- Ministry of Housing, Communities & Local Government (2019a) Local authority housing statistics: Year ending March 2018, England. [online] https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/773079/Local_Authority_Housing_Statistics_England_year_ending_March_2018.pdf (accessed 12 June 2019).

- Ministry of Housing, Communities & Local Government (2019b) Table 102: Dwelling stock: by tenure, Great Britain (historical series) [online] https://www.gov.uk/government/statistical-data-sets/live-tables-on-dwelling-stock-including-vacants (accessed 11 June 2019).

- Ministry of Housing, Communities & Local Government (2019c) Table 241 House building: permanent dwellings completed, by tenure [online] https://www.gov.uk/government/statistical-data-sets/live-tables-on-house-building (accessed 11 June 2019).

- Ministry of Housing, Communities & Local Government (2020) Table 244 House building: permanent dwellings started and completed, by tenure [online] https://www.gov.uk/government/statistical-data-sets/live-tables-on-house-building (accessed 12 February 2020).

- Ministry of Infrastructure of the Italian Republic (2006) Housing Statistics in the European Union, 2005/2006 (Federcasa: Italian Housing Federation).

- Morrison, J. (2017) Essential Public Affairs for Journalists (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

- Nielsen, B.G. (2010) Is breaking up still hard to do? – Policy retrenchment and housing policy change in a path dependent context’, Housing, Theory and Society, 27, pp. 241–257.

- OECD (2019) Affordable Housing Database (Paris: OECD).

- Olsen, S.H. (2019) ‘A place outside Danish society. Territorial stigmatisation and extraordinary policy measures in the Danish ‘Ghetto’’. Master’s thesis (Department of Human Geography, Lund University) [online] http://lup.lub.lu.se/student-papers/record/8981758 (accessed 12 February 2020).

- Ostrom, E. (2001) Vulnerability and polycentric governance systems, IHDP Update, 3, pp. 1–4.

- Oxley, M. (2009) Financing Affordable Social Housing in Europe (Nairobi: UN-HABITAT).

- Pierson, P. (1994) Dismantling the Welfare State? Reagan, Thatcher and the Politics of Retrenchment (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

- Poggio, T. & Whitehead, C. (2017) Social housing in Europe: Legacies, new trends and the crisis, Critical Housing Analysis, 4, pp. 1–10.

- Preece, J., Hickman, P. & Pattison, B. (2020) The affordability of “affordable” housing in England: Conditionality and exclusion in a context of welfare reform, Housing Studies, 35, pp. 1214–1238.

- Rampp, B. (2019) The Question of ‘identity’ in resilience research. Considerations from a sociological point of view, in: Rampp, B., Endreß, M. & Naumann, M. (Eds) Resilience in Social, Cultural and Political Spheres (Wiesbaden: Springer).

- Rogaczewska, N. (2017) Danish Non-profit Social Housing and Mortgage Institutes – A Common Stand on Future Financial Regulation. ECBC European Covered Bond Fact Book 2017 (Brussels: European Mortgage Federation).

- Scanlon, K. & Vestergaard, H. (2007) The solution, or part of the problem? Social housing in transition: the Danish case. European Network for Housing Research 2007 [online] http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/29945/1/The_solution_or_part_of_the_problem_(author).pdf (accessed 4 December 2019).

- Sejersted, F. (2011) The Age of Social Democracy: Norway and Sweden in the Twentieth Century (Princeton: Princeton University Press).

- Sjöstedt, M. (2015) Resilience revisited: Taking institutional theory seriously, Ecology and Society, 20, pp. 23.

- Statistics Denmark (2019) Det samlede boligbyggeri (historisk oversigt) efter byggefase og bygherreforhold [online] https://www.statbank.dk/10063 (accessed 2 December 2019).

- Statistics Sweden (1958) Statistisk årsbok för Sverige (Stockholm: Statistiska centralbyrån).

- Statistics Sweden (2004) Bostads- och byggnadsstatistisk årsbok 2004 (Stockholm: Statistiska centralbyrån).

- Statistics Sweden (2019) Bostadsbestånd efter hustyp, upplåtelseform och region (omräknad) 1990–2018 [online] https://www.scb.se/hitta-statistik/statistik-efter-amne/boende-byggande-och-bebyggelse/bostadsbyggande-och-ombyggnad/bostadsbestand/pong/tabell-och-diagram/antal-lagenheter-efter-hustyp/ (accessed 25 June 2019).

- Stephens, M. (2015) Housing in Sweden, not such a paradise. I-SPHERE Policy Blog, November 30. [online] https://www.i-sphere.hw.ac.uk/housing-in-sweden-not-such-a-paradise/ (accessed 12December 2019).

- Stephens, M. (2016) Housing Regimes 20 Years After Kemeny (Edinburgh: Urban Institute).

- Stephens, M. (2019) Social rented housing in the (DIS) United Kingdom: Can different social housing regime types exist within the same nation state?, Urban Research & Practice, 12, pp. 38–60.

- Streeck, W. & Thelen, K.A. (2005) Beyond Continuity: Institutional Change in Advanced Political Economies (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

- Sveriges Allmännytta (2019) Sveriges Allmännyttas medlemmar och associerade medlemmar [online] https://www.sverigesallmannytta.se/allmannyttan/statistik/ (accessed 4 August 2019).

- Hyresgästföreningen (2017) Riksenkäten 2015 (Stockholm: Swedish Union of Tenants).

- Till, M. (2005) Assessing the housing dimension of social inclusion in six European countries, Innovation: The European Journal of Social Science Research, 18, pp. 153–181.

- Torgersen, U. (1987) Housing: The wobbly pillar under the welfare state, Scandinavian Housing and Planning Research, 4, pp. 116–126.

- Turner, B. (1997) Municipal housing companies in Sweden: On or off the market?, Housing Studies, 12, pp. 477–488.

- Tutin, C. (2008) Social housing and private markets: from public economics to local housing markets, in: Scanlon, K., and Whitehead, C. (Eds) Social Housing in Europe II: A Review of Policies and Outcomes (London: LSE).

- UN (various years) Annual Bulletin of Housing and Building Statistics for Europe (New York: United Nations).

- Vestergaard, H. (2004) Boligpolitik i velfaerdsstaten, in: Ploug, N., Henriksen I, and Kaergaard, N. (Eds) Den danske velfaerdsstats historie: Antologi (04:18), 260–286 (København: Socialforskningsinstituttet).

- Walker, B., Holling, C.S., Carpenter, S. & Kinzig, A. (2004) Resilience, adaptability and transformability in social–ecological systems, Ecology and Society, 9(2): 5. [online] URL: http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol9/iss2/art5/

- Whitehead, C. (2017) Social housing models: Past and future, Critical Housing Analysis, 4, pp. 11–20.

- Wilson, W. (2018) Social Housing: Flexible and Fixed-term Tenancies (England). Briefing Paper Number 7173, 2 September 2018 (London: House of Commons Library).

- Wood, J.D.G. (2019) Mortgage credit: Denmark’s financial capacity building regime, New Political Economy, 24, pp. 833–850.