ABSTRACT

The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) offers a global blueprint to achieve a better and more sustainable future for every person, through universal action to address social, economic, and environmental inequity and inequality (United Nations Development Programme, 2021). For educators, SDG Goal 4 aims to ensure an equitable quality education that promotes lifelong learning opportunities and this goal has been endorsed by Pacific United Nations States in order to pave the road towards an inclusive education for all. We wish to argue, however, that attempting to meet global development goals for inclusive education is fundamentally problematic because of the nuances of the regions and contexts. For example, Pacific states, might better benefit from its own inclusive education trajectory that reflects individual contexts and understanding of distinct educational complexities. We propose the alignment of the global goals that positions local discourses of knowledge, values and understanding alongside inclusive education frameworks. The Pacific Disability Model offers a third space for disability discussions and actions that intersects global and local policy and practice binaries. By doing so, it is hoped that an inclusive approach to education can reach its potential for all, and particularly, students with disabilities in Pacific nations.

Introduction

In this article we address the issue that approaches to inclusive education can be imported problematically, in ways that by pass ontological and epistemological ways of being and thinking in regional contexts. Specifically we undertake a policy review and propose a model for inclusive education that can foreground local knowledge systems. Inclusive education, in development terms, was founded on position statements made in the Salamanca Statement (UNESCO Citation1994), paving the way for the practice to be enshrined into international law within Article 24 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) (United Nations General Assembly Citation2006) (Kanter Citation2019). Article 24 stipulates that persons with disabilities should have the ‘right without discrimination and on the basis of equal opportunity’ to an ‘inclusive education system’ (United Nations General Assembly Citation2006, para 1). While contention remains about the validity of inclusive education as a human right (for example see Breidlid Citation2013), it remains at the forefront of educational discourse around the world.

Globally, the United Nations has continued to press for government bodies to ensure they meet their human right obligations by delivering inclusive systems for children at every level of their education. Nations in the Pacific have responded to these global imperatives by addressing inclusive education plans, particularly for those students who have disabilities (Sharma et al. Citation2016; Tones et al. Citation2017). Consequently, these wider Pacific goals include the United Nations Sustainable Goals 2030 (Citation2015), which among them, speaks to an equitable and inclusive education (SDG 4).

Equity underpins the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The goals offer an international and co-ordinated approach for a better and more sustainable future for every person, especially for those in low to middle-income countries (Boeren Citation2019). Sustainable Development Goals are to be realised through universal action to address social, economic, environmental, and educational inequality (United Nations Citation2018). For educators and those interested in teaching and learning, SDG Goal 4 is significant in that it aims to ensure an equitable quality education that promotes lifelong learning opportunities. The premise underlying SDG4 is that it highlights the importance of educating children for whom access to education has been a challenge, specifically children with disabilities (Kusimo, Chidozie, and Amoo Citation2019). Goal 4 of the SDG was endorsed by Pacific United Nations countries in 2015 in order to pave the way towards an inclusive education for all (UNESCO Citation2018).

In recent times, Pacific Island countries have strengthened their commitment to challenging the barriers faced by students with disabilities, and most countries in the region having ratified the CRPD (Pacific Disability Forum Citation2018). Global support for this treaty is intended to promote and support the human rights and freedoms of people with a disability. The development of the 2016–2025 Pacific Framework for the Rights of Persons with Disabilities represents another significant step in the direction towards SDG Goal 4 where rights, as outlined in the CRPD, are protected, and regional applications are made. Additionally, Pacific Island governments, in the 2017 Pacific Roadmap for Sustainable Development, highlighted the rights of students with disabilities as one of the issues that requires a cooperative response (Pacific Islands Forum Secretariat Citation2017). This roadmap further guides the regional response towards the broader set of sustainable development goals.

We argue that attempting to meet global development goals for inclusive education in the Pacific without consideration of the local ontologies and epistemologies is fundamentally problematic because contextual nuances can be overlooked when measuring success via a set of pre-determined, global indictors. Examination of these global indictors through a critical lens brings to the fore their Eurocentric nature, a problem that exists within many human rights universals that can be particularly challenging for countries with a colonised history (Zembylas Citation2017), including disability rights activists in the Global South (Meekosha and Soldatic Citation2011). To help mitigate this, Pacific states may experience greater benefit from their own inclusive education trajectory, one that better reflects their individual contexts and where there is understanding of distinct educational complexities. We propose a different focus that prioritises a vision for students with disabilities that is locally defined. By doing so, goals that can be achieved are set, and ‘what was possible’ is reported. This is preferable to a focus on goals that were never likely to be enacted.

We contend that global goals need to be positioned alongside local discourses of knowledge, values, traditions, and understandings. Existing or developing inclusive education frameworks need to be foregrounded for consideration. There is an inherent risk in perceiving the two paradigms (Global North and Local) as binary, rather than as informing each other. As Rhodes (Citation2014) points out, cultural values are fundamentally important and shape economic, political, geographical and historical perspectives:

… in some cultures, equality is more important, whereas in others, hierarchy is more important, so perceptions about those who should have access to capacity-strengthening opportunities in these contexts will differ. Also, cultures can be placed along an individualistic/collectivist spectrum which in capacity terms means that expectations and roles related to individual or group learning will be different. (p. 3).

We propose that global and local perspectives can be beneficial to integrate if a third space – the Pacific Disability Model – is co-created. This ensures that the two policy approaches are about to intersect. By doing so, it is hoped that an education that is enacted in an inclusive way can support learning for all students, with and without a disability, in Pacific nations. Although prevalence is difficult to determine across the Pacific region due to different types of questions in censuses (Forlin et al. Citation2015), trends across Pacific nations for children with a disability provides a context for the significance of the model. These global trends are consistent with and include reported data from Pacific regions:

children with a disability are less likely than their peers to start school and are less likely to stay at and move through school (Filmer Citation2008),

children with a disability who do go to school have much lower success rates at school (World Health Organization Citation2011),

children with an intellectual or sensory disability are the least likely group to attend school,

children with a disability who do not attend school are more likely to live in poverty as an adult (World Health Organization Citation2011),

children with a disability who do attend school are more likely to be educated in targeted specialised settings, which may reinforce their marginalisation (Stubbs Citation2008),

approximately one third of the world’s children who are not currently in school (around 72 million) have a disability (Balescut and Eklindh Citation2006).

This article commences with detail on the complexity of setting goals on a global scale.

An argument is presented which addresses the policy and knowledge tensions of grounding the universal in the local, issues around introducing global goals in different cultural contexts, and the contrast between systems and relationality approached to policy implementation. Finally, a local Pacific Disability Model is conceptualised that is designed to foster a third space which supports stakeholder dialogue and a culturally responsive to inclusive education policy development and enactment.

Literature review

The complexity of global goals

Inclusive Education has been conceptualised in various forms. The United Nations (Citation2016) defines Inclusive Education as:

… a process of systemic reform embodying changes and modifications in content, teaching methods, approaches, structures and strategies in education to overcome barriers with a vision serving to provide all students of the relevant age range with an equitable and participatory learning experience and the environment that best corresponds to their requirements and preferences. (para. 11)

The Policy Guidelines for Inclusive Sustainable Development Goals (United Nations Citation2020) lay out a set of actions to meet the targets of Goal 4 by 2030, specifically for students with disabilities:

develop and implement a system of inclusive education,

provide access to, and completion of a quality and inclusive education,

provide quality early childhood education, care, and pre-primary education,

provide access to higher education and make available scholarships to people with disabilities,

assist in the development of employment skills, that will lead to employment for people with disabilities.

These targets are underpinned by an extensive number of completion goals, and further recommendations. However, each goal is complex in nature (it could be argued that countries globally have been working towards the first goal for decades, without success), and even at a glance, are not likely to be realised within the suggested time frame. While these complexities are highlighted, we do acknowledge many successful initiatives that have taken place in the Pacific. One example that can be showcased is the Access to Quality Education Program in Fiji in 2012 that initiated and evaluated a local model of inclusion. Project outcomes have included evidence of shifts towards positive attitudes and teacher practices regarding students with disabilities, and revised policies that relate specifically to the implementation of inclusive practices (Sprunt et al. Citation2017). Other very successful systems tools have been implemented in addition, such as the Pacific Education Management Information System which is a management tool that allows education administration to make informed decisions to support learning in schools. Described as a game changer by organisations such as the South Pacific Community (SPC), the system is able to track students who are marginalised and at risk so that targeted support can be provided (Naisoro, Citationn.d.)

In order to explore the development of inclusive education policy and practices in the Pacific region, we provide a policy review that addresses the following research questions:

How is inclusive education defined and enacted across the Pacific?

How do these relate to the global SDG goals?

What are the local challenges for Pacific nations in reaching global SDG goals?

While global goals may be intuitively sensible and collectively agreed upon, if they were easily attainable Pacific countries would already be implementing the actions contained within them. To investigate these questions, it is necessary to explore the development of inclusive education practices in the region. By looking at the why, or the contextual situation which currently defines the state of inclusive education in any given Pacific country, the how can be determined to afford meaningful forward planning. We frame the investigation within a theoretical backdrop of ‘third spaces’ and position the study within a ‘policy third space’ where co-construction occurs and individuals before state are privileged. Third space can be defined as a hybrid cultural in-between space (Bhabha Citation1994). We draw from third space literature linked to identity (Bhabha Citation1994), epistemology (Grudnoff et al, Citation2017), and socio-cultural relation (Bhabha Citation1994), technological factors (Packer, Citation2014), geographical factors (Soja, Citation1996), and professional practice negotiations (Zeichner Citation2010). Epistemologies converge and intersect in third spaces, providing opportunity for binary borders to become meeting zones where new initiatives and models emerge and co-constructed policies are produced.

Global north and local policy and knowledge tensions

To begin, it is necessary to explore what we mean when using the terms Global North and Global South within the context of this chapter. We have adopted the definition of Meekosha (Citation2011), who states: “Southern countries’ are, broadly speaking, those historically conquered or controlled by modern imperial powers, leaving a continuing legacy of poverty, economic exploitation and dependence … The ‘North’ … refers to the centres of the global economy in Western Europe and North America’ (p. 669). The influence of the Global North on Global South goal development is evidenced within current Pacific state policies and associated knowledge priorities. Given the complex nature of the relationship between Pacific nations and the Global North, both historically and present day, it is not surprising this influence has been problematic. Koya Vaka’uta (Citation2017) reflects on how ‘knowledge’ is shaped within Global North and Global South. The dominant beliefs, attitudes and behaviours of Global Northern knowledge are infused with a specific set of values which enforce particular conceptions of ‘space, time, gender, objectivity, subjectivity, knowledge and researcher privilege/power – all of which were/are conceptualised in the Global North’ (p. 2). Accepted notions of disability have too been framed within the knowledge space of the ‘hegemonic global North’, without consideration for the histories, cultures and contexts of nations in the Global South (Grech and Soldatic Citation2015, 2). It is unsurprising that Ferguson et al. (Citation2019) state it is no secret that these power dynamics influence policies and practices in education. From the vantage point of the Global North, the focus and value of measurement and quantitative assessment of the SDG4 reflect the ideals set by these countries (Ferguson et al. Citation2019). As a result, SDG4 goals are more likely to be more achievable by countries in the North compared to the South. In practice, the implementation of accountability through measurement can be challenging, as data collection and analysis is expensive (Johnstone, Schuelka, and Swadek Citation2020). The implication, therefore, is that although countries in both the North and South regard accomplishing these targets as important, the implementation of policies and subsequent practices to support the achievement of the goals will be based on available resources.

It is likely that, regardless of their commitment to the SDG, countries in the Global South may be unable to achieve the goals due to a lack of resources and subsequent support from policy and programmes (Sprunt et al. Citation2017). Johnstone, Schuelka, and Swadek (Citation2020) state that a cycle of dilemma is created in the Global South, where many ‘fail’ to meet targets despite possessing the necessary intellectual understanding and ability to achieve the goals:

… universal design approaches to assessment, testing accommodations, and modifications are either non-existent or in a nascent stage for global instruments and in member states. Further, while the metadata are helpful for tracking global trends, further elaboration on what a high-quality inclusive education experience means is needed – and can possibly be accomplished through more qualitative and locally relevant indicators. (p. 115)

It follows that countries in the Global South must begin to define and develop their own terms of sustainable development and strategic approach to achieving the targets, while considering the lessons from countries in the Global North. This is achievable if the divide of ‘knowledge’ is reframed between the North and South. The reframing of what is considered relevant knowledge may in part address the tensions that exists between Global North scientific knowledge and local knowledge, which are significant for both SDG4 goals and the overarching focus of inclusive education (Inoue and Moreira Citation2017). Working ‘alongside’ should be viewed with caution, however. Many development analysts observe that, despite shifts in Global North dominated North/South rhetoric towards partnerships, little has been done to dismantle the longstanding hierarchies between the Northern ‘benevolent provider of knowledge and material assistance’ and their Southern partners (Mawdsley Citation2017, 108).

The challenge of bringing global goals to a local context

One of the challenges that the SDGs pose is they are largely system focused and driven, where systems are understood from a Eurocentric paradigm, as they require ‘systemic reform’. Some examples of intention towards systemic reform are provided in the recommendations set out in the Policy Guidelines (United Nations Citation2020). These include: to ensure the education of all students, including students with disabilities, are led and governed by Ministries of Education; to establish inclusive education units to lead national policies and plans to transition towards inclusive education; and to establish coordination mechanisms that link the Ministries of Education with other Ministries, government disability focal points and other public bodies. The framing of the SDGs within reform that is designed to be led or guided by systems, may not align with the structures that embody systems of government in the Pacific states, particularly nations with small populations.

Another challenge is created by the way success is understood. Success is defined by the production of a quantifiable outcome, rather than driven by the quality of what is being done (Boeren Citation2019). Boeren (Citation2019) refers to this application of SDG targets as ‘governance by numbers’ (p. 1). The emphasis on quantifiable empirical data was prominent in the earlier iteration of global goals, the Millennium Development Goals. Interestingly, many of these continue to frame the current Sustainable Development agenda (Höne Citation2015), which brings into question the efficacy of the process. Yet this prevailing paradigm ensues, with a focus on finance and data for development. Quantitative indicators are seen as an identifiable measure for reporting and have been noted as important by education development organisations. Loewe (Citation2015) argues the problematic nature of this in local contexts, as the relevance of education for improving the economic, social, and political aspects of societies is not considered when only inputs are measured, and outputs or impact are ignored.

Global goals in different cultural contexts

Many indicators of the SDG 4 are based on norms that may not be applicable in all cultural contexts. Well-intentioned desires to navigate tensions between policy priorities and principles of equity can at times lead to compromises within systems (Fisher and Fukuda-Parr Citation2019). For example, SDGs education indicators emphasise formal schooling at the expense of informal learning opportunities (Béné et al. Citation2016). This goal neglects to acknowledge the importance of situations in which children learn from helping their parents with tasks at home and the community, where they can gain local knowledge to enhance their skills and abilities by growing up and living in the Pacific (Nalau et al. Citation2018). Similarly, assumptions are also made that prioritises the individual, which may be at odds with local perspectives on collective well-being and community practices (McNamara et al. Citation2020). By persisting with indicators that run counter to local norms, the SDGs run the potential risk of long-term negative impacts in Pacific communities.

Critics have argued since the Millennium Development Goals, that global goals miss the mark in terms of including culturally specific aspects of education and the role education plays within specific contexts (Barrett Citation2009). Likewise, SDG 4 is under scrutiny for failing to include locally contextualised data. The issues include an absence of, or weak policy or plans to support children with disabilities, inflexible assessment, untrained teachers, difficulty in physical access to education, negative attitudes to disability by teachers and other community members, access to specialist services, and poverty (Miles, Lene, and Merumeru Citation2014; Sharma, Loreman, and Simi Citation2017).

Sprunt et al. (Citation2017) reported the findings of an investigation into Fijian priorities for measuring the success of efforts within the process of disability-inclusive education relating to SDG 4. The paper concluded that the targets within SDG 4 were comparable with Fijian priorities, however additional indicators that related to locally prioritised changes were required. Fourteen indicators were listed in order of those proposed most to least frequently: 1) academic achievement; 2) participation in school and school-related activities; 3) participation in the community, which including faith-based organisations; 7) peer interaction and social skills; 8) self-esteem/confidence; 9) transition through the different levels of education; 10) family support for their child’s education; 11) child’s happiness and quality of life; 12) stakeholder participation and approval; 13) school attendance; and 14) discrimination. This list of priorities highlights the contextual issues for attaining SDG 4 that reflect in part the need to consider the capacity (infrastructure capabilities as well as human resources) for Pacific countries to deliver SDG targets, and have already been interpreted as aspirational goals (Pacific Islands Forum Secretariat Citation2017).

Systems versus relationality

As noted earlier, the SDGs are measurement based and SDG 4 recommendations place a strong emphasis on systems. For example, the Policy Guidelines for Inclusive Sustainable Development Goals (United Nations Citation2020) suggest possible actions that include:

Strengthening the education management information system to engage in systematic data collection and disaggregation, ensure coordination of data systems with the national statistical office and support research to identify gaps in provision, with a view to strengthening the implementation of inclusive education, and

Establishing accessible mechanisms through the educational authorities, as well as independent accountability mechanisms for students, parents and representative organizations, to lodge complaints concerning the implementation of inclusive education, including claims of disability-based discrimination. (p. 10)

The goal of measurement and specifically the quantification of various systems has been positioned as fundamental to the ‘successes’ of inclusive education programmes and practices. However, a focus on the importance of systems discounts a central tenant of Pacific thinking, this is of relationality. Relationality collectively defines identity and being in Pacific contexts (Armstrong, Johansson-Fua, and Armstrong Citation2021). Furthermore relationality also defines behaviour expectations and social norms (Thaman Citation2009). Therefore, any conversation regarding inclusion needs to be framed through the notion of connectivity between people, time, place, and land (Armstrong, Johansson-Fua, and Armstrong Citation2021). Once the role of relationality is acknowledged and appreciated, top-down and ‘borrowed’ applications of systemic measurement come under question as the primary method of assessing successful inclusive education.

A further example illustrates this point. A strategy noted in SDG 4 to achieve inclusive education is to raise awareness of disability to change community attitudes (United Nations Citation2020). Raising awareness involves making the suggestion to students, teachers, and parents that disabled people have the right to education. Raising awareness is, in itself, a superficial but easily achievable goal if one was to deliver a workshop, deliver a campaign, or communicate through social media. However, in many Pacific regions, children with disability are marginalised because of strong cultural beliefs around the value of educating students with a disability (Page et al. Citation2018; Tones et al. Citation2017). Challenging these widely held beliefs is a very complex proposition. Although a focus on awareness may shift negative attitudes towards people with disability (United Nations Citation2020), to create true transformative change one must address to the heart of the issue which evokes various discourses relating to Pacific peoples’ conceptualisations of disability (Picton and Tufue-Dolgoy Citation2018). It follows that situation-specific goals must be articulated for the goal of quality inclusion to be fully realised.

In recognition with the sentiment that people precede systems, Slee (Citation2018) provides an alternative definition to that of the United Nations (Citation2016). Instead of beginning with ‘inclusion involves a process of systemic reform … ’ (United Nations, para 11) Slee (Citation2018) defines inclusive education as:

… securing and guaranteeing the right of all children to access, presence, participation and success in their local regular school. Inclusive education calls upon neighbourhood schools to build their capacity to eliminate barriers to access, presence, participation, and achievement in order to be able to provide excellent educational experiences and outcomes for all children and young people. (p. 8) … Inclusive education is secured by principles and actions of fairness, justice and equity. It is a political aspiration and an educational methodology. (p. 9)

This definition positions the student as the focus of attention, and the systems as a means of support. It acknowledges the importance of relationships. This emphasis is echoed by Pacific organisations such as the Pacific Islands Forum Secretariat (Citation2009). Here, inclusive education is defined as:

… an approach which seeks to address the learning needs of all children, youth and adults with a specific focus on those who are vulnerable to marginalisation and exclusion. Inclusive education implies that all learners with or without disabilities are able to learn together through access to common ECCE provisions, schools and community educational settings with an appropriate network of support services. (p. 11)

These relational definitions encapsulate conceptualisations of inclusion that reflect notions of full participation in the classroom for all students. Of note is the existence and role that special schools play in the Pacific, as they provide another example of the problem of one-size-fits-all SDG 4 global targets. Special schools in Pacific regions grew from the inheritance of a special education ideology that originated from the Global North (Sharma et al. Citation2013). Many island states continue to rely on the educational provision of special schools (e.g. The Republic of Nauru, Fiji, Samoa, Solomon Islands) or units attached to mainstream schools (e.g. The Cook Islands). This is despite the SDG 4 Policy (United Nations Citation2020) clearly advocating against special schools, indicating that systems need ‘to avert the reliance on special education structures such as special schools, separate classrooms, or setting exclusively for students with disabilities’ (p. 36). Yet, it might be argued that the role of special schools in the Pacific is different in comparison with Global North countries (Tones et al. Citation2017). In the Global North, the presence of special schools continues despite philosophical shifts towards inclusion (Boyle and Anderson Citation2020) for reasons such as the provision of additional and specialist services for children and young people with complex and multiple needs (Bovair Citation2018). While this argument holds for Pacific nations, their trajectory towards inclusive education has been very different (Tones et al. Citation2017). It could be said therefore, that special schools serve an additional function in Pacific Island states as they provide an opportunity for students with a disability to participate in an education, where many in the past have stayed at home.

The array of examples provided here highlights the mismatch between the Global North and Pacific notions of inclusive education. Although there has been extensive policy borrowing from the Global North, the Pacific has made and continues to make sense of inclusion and inclusive education practices (Armstrong, Johansson-Fua, and Armstrong Citation2021). This is despite long-held top-down policies and practices that, on reflection, hold little relevance for the communities and schools in the Pacific country (Panapa Citation2014). Sharma, Loreman, and Macanawai (Citation2015) argues that, although many governments in the Pacific are committed to inclusive education and SDG 4, very little progress has been made. It has been suggested that top-down strategies are likely to fail where initiatives meet resistance from teachers and others involved in education (McDonald and Tufue-Dolgoy Citation2013). Resistance is more likely in situations where fundamental principles of inclusive education and responses to issues of disability are inconsistent with local cultural values and attitudes and communal beliefs (Miles, Lene, and Merumeru Citation2014; Page et al. Citation2018; Page, Mavropoulou, and Harrington Citation2021).

Pacific and Global North notions of inclusive education need not be regarded in binary terms. Rather, lessons that can be learned from the Global North, to inform quality inclusive educational practices in the Pacific. Baskin (Citation2002) speaks of multiple ways of knowing, but highlights the need for these to ‘occur according to the terms of all participants and not only through the conditions and decisions made by the dominant group’ (p. 3). This is further explored in Kamenopoulou’s (Citation2018) conceptualisation of inclusive education in the Global South which highlights a ‘simple but fundamental distinction’ (p. 130) between notions of inclusive practice that are generic and can therefore be generalised across different nations (such as some aspects of knowledge from the Global North), and those that ‘can only be known or understood if … specific contexts (such as different countries in the Global South) are explored’ (p. 130); both generic and enactment of inclusive education. We argue that the two world views can be brought together and accommodated within the frame of inclusive education, where evidence-based research and local ways of knowing merge to create and enact contextually relevant goals.

The Pacific disability model

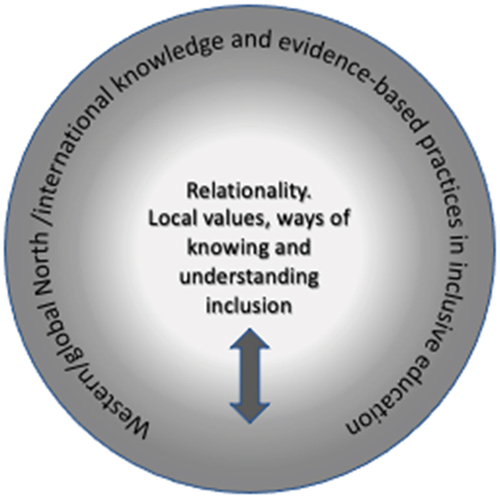

We propose a conceptualisation of inclusive education in the Pacific that positions Pacific relationality, values, and ways of knowing at the centre, and situates global knowledge and understanding of inclusive education around it. What is understood as inclusion is informed by international policy while privileging the local contexts of Pacific states. This ‘third space’ is illustrated in .

The model addresses the historical imposition of inclusion policy and philosophy in the Pacific region. In doing so, we recognise the differences between and within Pacific nations in their knowledge, understanding and values towards inclusion. As Sharma et al. (Citation2019) point out, an understanding of the context also involves an understanding that Pacific nations are similar and different in language culture and religion. These differences and similarities need to be considered together in order to engage in the realities of education systems in efforts to move forward in the inclusion journey.

Relational ontology and epistemology is common in many local paradigms (Chilisa, Major, and Khudu-Petersen Citation2017; Pérezts, Russon, and Painter Citation2020) and the notion of prioritising relationality is not new (Armstrong, Johansson-Fua, and Armstrong Citation2021; Cobb, Couch, and Fonua Citation2019; Keddie Citation2014). Armstrong, Johansson-Fua, and Armstrong (Citation2021) speak of Pacific people identity being defined by the collective. Identity is also formed in connection to the land. Wendt (Citation1999) describes this relationality as va, where ‘va is the space between, the betweenness, not empty space, not space that separates but space that relates, that holds separate entities and things together’ (p. 402). Much of the literature on va originates from Samoa and Tonga, yet the concept is part of many Pacific cultures. While the meaning of va differs between Pacific nations, it is generally understood as the basis of social interaction where interpersonal and social interactions set the expectations for social norms and behaviours (Thaman Citation2008). Va is maintained through family, community, and individual contexts. Maintaining relationships is important to maintaining harmony between different people, therefore relationality matters.

The significance of va is acknowledged in the Pacific Disability Model: A policy third space to inform practice (). Conversations around inclusive education for students with disabilities need to occur within a relational context which connects to both people and place. If relationality is ignored, any progress in inclusive education is unlikely to gain traction. Reynolds (Citation2016) outlines the danger of not understanding the importance of va:

There is a case for a better understanding of [Pacific] education through developing an understanding of va, a concept indigenous to some Pacific groups, as a significant strand among the interwoven values and strategies in the … education system. We need to seek and then use ways in which relatedness is better configured, maintained and nurtured in both teaching and research as we pursue [Pacific] success. (p. 200)

The significance of collaboration

The Pacific Disability Model recognises and understands the importance of va, and the methods of collaboration that take place within this space. Local peoples’ values and knowledges are situated at the centre of this strategy, with global knowledge regarding inclusive education the layer surrounding it. This brings together two sets of knowledges to make a stronger whole. Fa’avae (Citation2018) suggests the benefit of this approach is that it enables learning from and working together, in order to discover new ways ‘to support and strengthen Oceanic people and their educational needs’ (p. 81). Supporting and strengthening can be achieved by using sources of knowledge from the inclusive education research. Instead of adopting models that work in Global North settings, Pacific nations can appropriate relevant evidence-based knowledge, where it is deemed useful, and merge this with their own knowledge, to inform culturally responsive inclusive policies and practices. The role here of Global North knowledge is to contribute to a mutual interest to progress of change (Gaztambide-Fernández Citation2012), in this case for children and young people with disabilities in the Pacific.

It must be noted here that we do not rest on assumptions that current global understandings and practices of inclusion are without criticism, and acknowledge that no country can yet lay claim to indisputable success in this space. Slee (Citation2018) makes this point about the current state of inclusive education in many Global North nations:

Local conditions are crucial, but they mustn’t stop us from questioning overarching global theories and practices that sustain the exclusion of vulnerable students such as children with disabilities. For example, traditional special education sustains ableist assumptions about disability through longstanding practices of categorisation and separation of children according to deficits. Exclusion is attributed to individual student impairment rather than to the disabling cultures and practices of schooling (Slee Citation2018, 14).

We must be discerning about what knowledges from the Global North may best contribute to the mutual interests and shared goals of inclusive education in the Pacific. Attention must also be placed on the role of resistance, as mentioned earlier in this paper: that resistance is more likely when principles of inclusive education and community inclusion of marginalised groups are not consistent with local values, attitudes and beliefs (Miles, Lene, and Merumeru Citation2014; Page et al. Citation2018; Page, Mavropoulou, and Harrington Citation2021). To address this, the Pacific Disability Model identifies the role that collaboration plays in contesting resistance. An approach of working alongside is one example of successful application of collaborative practices. This was effectively demonstrated in a recent project in the Republic of Nauru where community and stakeholder consultation and collaboration, embedded within a culturally relevant framework, enabled the successful co-construction of a systems model of inclusive education practice for teachers across the country (Page et al. Citation2021).

Standing in the centre

Williams and Staulters (Citation2014) report on the current educational climate that has lent itself to the phenomena of isolated, disconnected programmes being offered by those in the Global North. These are often delivered as one-off workshops that are designed to address identified gaps in education in the South. Williams and Staulters argue that to achieve change, more considered and comprehensive programmes are required to embed fidelity and integrity. The guiding principles for programmes should be teamwork and collaboration, within partnerships. Several criteria have been identified that underpin a successful partnership: a meaningful relationship between participants, shared aims and goals, complementary capabilities of those involved, and a shared understanding of the expectation of and problem-solving processes for the collaboration (Goddard, Cranston, and Billot Citation2006). Rosenfield (Citation2008) describes a form of collaboration that involves three central elements for working together, if a partnership is considered worthwhile: (a) developing the necessary communication and relationship skills for sustaining trusting relationships; (b) working through problem-solving stages that are necessary to define the problem, generate hypotheses, identify and implement interventions, and document the effectiveness of interventions; and (c) using evidence-based assessment and intervention strategies for effective progress. All components, particularly element (b), must be viewed through the key principles that are held at the centre of the model – relationality, and the primacy of local values, ways of knowing, and understanding.

Activities can be transformed through partnerships and collaborations if there is a focus on relational space (Koya Vaka’uta Citation2017). These spaces acknowledge how beliefs, attitudes, and behaviours are shaped by local understandings rather than being framed exclusively by the beliefs and values of the Global North. Issues are framed differently, priorities are considered differently, problems are defined differently, and people participate on different terms (Smith Citation2021). In a context that foregrounds relationality, the request to access information from the community is seen as an act of negotiation, rendering the partners tied in a relational space that is determined by the cultural understandings of reciprocity, and governed by the rules of engagement that the negotiation demands. This partnering is of particular importance when working in a contested space, such as inclusive education and disability.

It is vital that the presence of partners from the Global North should benefit the people in the Pacific. At times, it has been noted that what is regarded as ‘important’ does not always capture local values and learning. While international assistance may be required to improve educational outcomes for teachers and students in the Pacific, in some circumstances funding has been attached to projects that international partners have decided should be a priority (Fa’avae Citation2018). This is problematic. Panapa (Citation2014) describes it like this:

… even at a national level, such as in Tuvalu, policy development and decision-making begins at the macro level (national and regional) and descends to the micro level (community, school, and class- room). This trickle-down approach assumes that central governments will develop education, and the benefits of education will, in due course, trickle down to the community and schools. However, many times, trickle-down approaches fail. All these factors make it difficult for education to thrive in many countries, particularly those that are developing. (p. 54)

These failed experiences highlight the need to manage partnerships and collaborations differently and supports the call for change. This change can be realised through the approach advocated for in the Pacific Disability Model, as presented in . The model privileges an exchange between ways of knowing (represented by the two headed arrow); knowledge from the Global North and local knowledge are not binary, but rather come together. The grey transition circle around the centre circle illustrates this point. This sense of reciprocity is reinforced by Höne’s (Citation2015) notion of the ‘pluriverse’ (p. 11) where, instead of a universal one meaning made, multiple meanings are able to be realised. This reiterates the the problem indicated previously of a primary focus on empirical quantitative data, particularly in relation to the SDG 4 and the emphasis on ‘what gets measured gets done.’ When stakeholders come together in a space that allows multiple meanings the focus can shift from an exclusive focus on ‘what can be measured’, to the quality of the work that is required. An emphasis on a plurality of solutions calls for culturally relevant alternatives that are complemented by and not defined through Global North knowledge and ontological understandings.

The impact of colonisation places education in the Pacific under a scrutinising lens have been clearly articulated (Scaglion Citation2015; Thaman Citation2014). Authors have examined this impact of colonisation on inclusive and special education policies and practices specifically (Le Fanu and Kelep-Malpo Citation2015; McDonald and Tufue-Dolgoy Citation2013; Miles, Lene, and Merumeru Citation2014). Findings from this work indicate that inclusive and special education policies in the Pacific have undeniably been influenced by thinking from the Global North. This is evidenced by the impact of donor funding, monitoring, and evaluation agendas on the local feel and flavour of inclusive practice and approaches (Aiafi Citation2017).

The influence of international perspectives and directions for the good of global interests persists with the SDG 4. Pacific education ministries continue to grapple with general budgetary and resource constraints that can place pressure on countries to make forced choices between investing in improving and providing a quality education for all, and other major initiatives (Pacific Disability Forum Citation2018). SDG 4 in particular has expressed a bold agenda for inclusive education and children with disabilities (Ferguson et al. Citation2019), and has placed a complex piece of work at the feet of governments and local schools in the Pacific (Pacific Disability Forum Citation2018).

Conclusion

Despite an acknowledgment that inclusive education is a cost-effective way to improve equity and access, and provide a quality education for all, there remains a resistance to the realisation of this goal in the Pacific. It has been suggested this is because inclusive education continues to be considered a subset of policies rather, than an overarching objective for all children (Pacific Disability Forum Citation2018).

Sustainable development is almost entirely centred on a Global northern epistemological and ideological framework, and this position is reflected among UN organisations (Breidlid (Citation2013). These globalised ideas and ideologies in education play a fundamental role in the subsequent development of policy (Sayed and Moriarty Citation2020). The term global itself has become a condition of the world, as a prominent discourse with international reach, highlighting who key actors and organisations are. It has been argued these changes were a result of ‘the complex reworking, re/bordering and re/ordering of education spaces to include a range of scales of action’ (Robertson Citation2012, 18), underlining the geographically situated position of the ‘international’ powerhouses.

Participation and community involvement has been a guiding principle of work in the Pacific to grow inclusive education practices (Sharma Citation2020; Sprunt et al. Citation2017). Yet, the concepts rarely go beyond the provision of donor aid and they seldom influence attitudes and practices within the wider community (Carm Citation2014). This article provides a way to reposition local knowledge and participation. To achieve this aim, the Pacific Disability Model has been proposed that merges Pacific knowledges with knowledge from the Global North. The model seeks to provide a framework to address some of the pitfalls of the externally imposed aims and goals of SDG 4 with its inherent Global North bias. It prioritises local values and knowledges, and recognises relationality an essential element of third space partnerships. The conceptualisation of third space helps bridge the global – local binary and aspires to create sustainable, meaningful, and culturally responsive inclusive practices across Pacific nations.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Angela Page

Dr Angela Page is an experienced educational psychologist and special education teacher who has worked as an inclusive education advisor in New Zealand, Australia Asia and Pacific countries such as Indonesia, the Philippines, the Republic of Nauru, Tuvalu, Fiji, the Cook Islands, and Vanuatu. Her research and practice interests are focused in addressing the needs of marginalised children and youth within new and emerging contexts within the Asia-Pacific region.

Angelinah Vira

Angelinah Vira is a PhD student at the University of Newcastle and lives in Vanuatu. She is also employed at the Vanuatu Ministry of Education and Training and has extensive experience as an inclusive education specialist. Professor Susan Ledger is Head of School - Dean of Education at the University of Newcastle. Susan is a dedicated educator, researcher and advocate for the teaching profession who has a passion for connecting people, places and projects. Susan has had a range of educational experiences in both primary, secondary and tertiary settings around the globe.

Joanne Mosen

Dr Jo Mosen has extensive experience in inclusive development across the Asia Pacific region. Her work spans disability inclusion in education programs, gender and disability sensitivity in curriculum development, disability rights and the intersectionality of disability and gender in development programming. She also has skills in research and evaluation relevant to informing an evidence-based understanding of the lived experience of marginalised groups in developing contexts. Joanna Anderson (PhD) is a Senior Lecturer in inclusive education in the School of Education, University of New England, Australia. She has a growing research profile and her areas of interest include inclusive education in pacific contexts, school leadership and inclusive education, and inclusive education in new build schools, and the ethical and moral considerations of inclusive education. Associate Professor Jennifer Charteris is an experienced researcher. Jennifer’s research interests span fields of professional learning and school learning environments. As a teacher educator with teaching experience in Aotearoa/New Zealand, Australia and the UK, Jennifer has worked with principals, teachers, students, school communities, and professional learning providers across the primary, secondary and tertiary sectors.

Christopher Boyle

Christopher Boyle, PhD is a Professor of Inclusive Education and Psychology at the University of Adelaide. He is a Fellow of the British Psychological Society and a Senior Fellow of the Higher Education Academy. Chris has various experiences in the Pacific region – he is an Adjunct Professor in the School of Education at the University of Fiji, has collaborated on research in the Cook Islands with Dr Angela Page, is an invited member of the Fiji Higher Education Commission External Reference Group

References

- Aiafi, P. R. 2017. “The Nature of Public Policy Processes in the Pacific Islands.” Asia & the Pacific Policy Studies 4 (3): 451–466. doi:10.1002/app5.196.

- Armstrong, D., A. C. Armstrong, and I. Spandagou. 2011. “Inclusion: By Choice or by Chance?” International Journal of Inclusive Education 15 (1): 29–39. doi:10.1080/13603116.2010.496192.

- Armstrong, A. C., S. Johansson-Fua, and D. Armstrong. 2021. “Reconceptualising Inclusive Education in the Pacific.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 1–14. doi:10.1080/13603116.2021.1882057.

- Balescut, J., and K. Eklindh. 2006. Historical Perspective on Education for Persons with Disabilities. Background Paper for EFA Global Monitoring Report. Paris: UNESCO.

- Barrett, A. 2009. “Working Paper No. 16. EdQual: A Research Programme Consortium on Implementing Education Quality in Low Income Countries.” http://r4d.dfid.gov.uk/PDF/Outputs/ImpQuality_RPC/workingpaper16.pdf

- Baskin, C. 2002. “Re-generating Knowledge: Inclusive Education and Research.” Paper presented at the Annual Conference of the Canadian Indigenous and Native Studies Association. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED476849.pdf

- Béné, C., R. M. Al-Hassan, O. Amarasinghe, P. Fong, J. Ocran, E. Onumah, R. Ratuniata, T. Van Tuyen, J. A. McGregor, and D. J. Mills. 2016. “Is Resilience Socially Constructed? Empirical Evidence from Fiji, Ghana, Sri Lanka, and Vietnam.” Global Environmental Change 38: 153–170. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2016.03.005.

- Bhabha, H. K. 1994. “Anxious Nations, Nervous States.” In Supposing the Subject, edited by J. Copjec, 201–217, London, Verso.

- Boeren, E. 2019. “Understanding Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 4 on “Quality Education” from Micro, Meso and Macro Perspectives.” International Review of Education 65 (2): 277–294. doi:10.1007/s11159-019-09772-7.

- Bovair, K. 2018. “A Role for the Special School.” In Special Education in Britain after Warnock, edited by J. Visser and G. Upton, 110–125, London, Routledge.

- Boyle, C., and J. Anderson. 2020. “The Justification for Inclusive Education in Australia.” Prospects 49 (3): 203–217. doi:10.1007/s11125-020-09494-x.

- Breidlid, A. 2013. Education, Indigenous Knowledges, and Development in the Global South: Contesting Knowledges for a Sustainable Future. Vol. 82. New York, Routledge.

- Carm, E. 2014. “Inclusion of Indigenous Knowledge System (IKS)–A Precondition for Sustainable Development and an Integral Part of Environmental Studies.” Journal of Education and Research 4 (1): 58–76. doi:10.3126/jer.v4i1.10726.

- Chilisa, B., T. E. Major, and K. Khudu-Petersen. 2017. “Community Engagement with a Postcolonial, African-based Relational Paradigm.” Qualitative Research 17 (3): 326–339. doi:10.1177/1468794117696176.

- Cobb, D. J., D. Couch, and S. M. Fonua. 2019. “Exploring, Celebrating, and Deepening Oceanic Relationalities.” International Education Journal: Comparative Perspectives 18 (2): 1–10. https://openjournals.library.sydney.edu.au/index.php/IEJ

- Fa’avae, D. T. M. 2018. “Complex Times and Needs for Locals: Strengthening (Local) Education Systems through Education Research and Development in Oceania.” International Education Journal: Comparative Perspectives 17 (3): 80–92. https://openjournals.library.sydney.edu.au/index.php/IEJ

- Ferguson, T., D. Ilisko, C. Roofe, and S. Hill. 2019. SDG4 Quality Education: Inclusivity, Equity and Lifelong Learning for All. Bingley, Emerald.

- Filmer, D. 2008. “Disability, Poverty, and Schooling in Developing Countries: Results from 14 Household Surveys.” The World Bank Economic Review 22 (1): 141–163. doi:10.1093/wber/lhm021.

- Fisher, A., and S. Fukuda-Parr. 2019. “Data, Politics and Knowledge in Localizing the SDGs.” Journal of Human Development and Capabilities 20 (4): 375–485. doi:10.1080/19452829.2019.1669144.

- Forlin, C., U. Sharma, T. Loreman, and B. Sprunt. 2015. “Developing disability-inclusive Indicators in the Pacific Islands.” Prospects 1–15. doi:10.1007/s11125-015-9345-2.

- Gaztambide-Fernández, R. A. 2012. “Decolonization and the Pedagogy of Solidarity.” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society 1 (1): 41–67.

- Goddard, J., N. Cranston, and J. Billot. 2006. “Making It Work: Identifying the Challenges of Collaborative International Research.” The International Electronic Journal of Leadership in Learning 10 (11). http://hdl.handle.net/10292/5827

- Grech, S., and K. Soldatic. 2015. “Disability and Colonialism: (Dis)encounters and Anxious Intersectionalities.” Social Identities 21 (1): 1–5. doi:10.1080/13504630.2014.995394.

- Grudnoff, L, M Haigh, M Hill, M Cochran-Smith, F Ell, and L Ludlow. 2017. “Teaching for Equity: Insights from International Evidence with Implications for a Teacher Education Curriculum.” The Curriculum Journal 28 (3): 305–326. doi:10.1080/09585176.2017.1292934.

- Höne, K. (2015). “What Quality and Whose Assessment: The Role of Education Diplomacy in the SDG process–A New Diplomacy for a New Development Agenda?” 3rd Nordic Conference on Development Research, Gothenburg, Sweden. http://www.educationdiplomacy.org

- Inoue, C. Y. A., and P. F. Moreira. 2017. “Many Worlds, Many Nature (S), One Planet: Indigenous Knowledge in the Anthropocene.” Revista Brasileira de Política Internacional 59 (2): 1–19. doi:10.1590/0034-7329201600209.

- Johnstone, C. J., M. J. Schuelka, and G. Swadek. 2020. “Quality Education for All? The Promises and Limitations of the SDG Framework for Inclusive Education and Students with Disabilities.” In Grading Goal Four, edited by A. Wulff, 96–115, Leiden, Brill Sense.

- Kamenopoulou, L. 2018. Inclusive Education and Disability in the Global South. 1st ed. Cham, Springer International Publishing. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-72829-2.

- Kanter, A. 2019. “The Right to Inclusive Education for Students with Disabilities under International Human Rights Law.” In The Right to Inclusive Education in International Human Rights Law, edited by G. de Beco, S Quinlivan, and J. Lord, 15–57. Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/9781316392881.003.

- Keddie, A. 2014. “Indigenous Representation and Alternative Schooling: Prioritising an Epistemology of Relationality.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 18 (1): 55–71. doi:10.1080/13603116.2012.756949.

- Koya Vaka’uta, C.F. 2017. “Rethinking Research as Relational Space in the Pacific: Pedagogy & Praxis.” In Relational Hermeneutics: Decolonisation and the Pacific Itulagi, edited by U. L. Vaai and A. Casimira, 65–84, Suva, University of the South Pacific.

- Kusimo, A., F. Chidozie, and E O. Amoo. 2019. “Inclusive Education and Sustainable Development Goals: A Study of the Physically Challenged in Nigeria.” Cogent Arts & Humanities 6 (1): 1–13. doi:10.1080/23311983.2019.1684175.

- Le Fanu, G., and K. Kelep-Malpo. 2015. “Papua New Guinea: Inclusive Education.” In Education in Australia, New Zealand and the Pacific, edited by M. Crossley, G. Hancock, and T. Sprague, 219–242, London: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Loewe, M. 2015. “How to Reconcile the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)?” https://www.die-gdi.de/en/briefing-paper/article/post-2015-how-to-reconcilethe-millennium-development-goals-mdgs-and-the-sustainable-development-goals-sdgs/

- Mawdsley, E. 2017. “Development Geography 1: Cooperation, Competition, and Convergence between ‘North’ and ‘South’.” Progress in Human Geography 41 (1): 108–117. doi:10.1177/0309132515601776.

- McDonald, L., and R. Tufue-Dolgoy. 2013. “Moving Forwards, Sideways or Backwards? Inclusive Education in Samoa.” International Journal of Disability, Development and Education 60 (3): 270–284. doi:10.1080/1034912x.2013.812187.

- McNamara, K. E., R. Clissold, R. Westoby, A. E. Piggott-McKellar, R. Kumar, T. Clarke, F. Namoumou, F. Areki, E. Joseph, and O. Warrick. 2020. “An Assessment of community-based Adaptation Initiatives in the Pacific Islands.” Nature Climate Change 10 (7): 628–639. doi:10.1038/s41558-020-0813-1.

- Meekosha, H. 2011. “Decolonising Disability: Thinking and Acting Globally.” Disability & Society 26 (6): 667–682. doi:10.1080/09687599.2011.602860.

- Meekosha, H., and K. Soldatic. 2011. “Human Rights and the Global South: The Case of Disability.” Third World Quarterly 32 (8): 1383–1397. doi:10.1080/01436597.2011.614800.

- Miles, S., D. Lene, and L. Merumeru. 2014. “Making Sense of Inclusive Education in the Pacific Region: Networking as a Way Forward.” Childhood 21 (3): 339–353. doi:10.1177/0907568214524458.

- Naisoro, T. n.d. “EMIS, a Game Changer for Pacific Education Systems.” SPC. https://www.spc.int/updates/blog/blog/2021/03/emis-a-game-changer-for-pacific-education-systems

- Nalau, J., S. Becken, J. Schliephack, M. Parsons, C. Brown, and B. Mackey. 2018. “The Role of Indigenous and Traditional Knowledge in ecosystem-based Adaptation: A Review of the Literature and Case Studies from the Pacific Islands.” Weather, Climate, and Society 10 (4): 851–865. doi:10.1175/WCAS-D-18-0032.1.

- Pacific Disability Forum. 2018. “From Recognition to Realisation of Rights: Furthering Effective Partnership for an Inclusive Pacific 2030.” https://www.internationaldisabilityalliance.org/sites/default/files/final_sdg_report_2018_print_.pdf

- Pacific Islands Forum Secretariat. 2009. Pacific Education Development Framework 2009-2015 (PEDF). https://www.yumpu.com/en/document/view/21051641/pacific-education-development-framework-pedf-2009-2015-pacific-

- Pacific Islands Forum Secretariat. 2017. The Pacific roadmap for sustainable development. https://www.forumsec.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/The-Pacific-Roadmap-for-Sustainable-Development.pdf

- Packer, R 2014. “Third Space Place of Other: Reportage from the Aesthetic Edge.” https://thirdspace-netwrok.com/defining-the-third-space/

- Page, A., C. Boyle, K. McKay, and S. Mavropoulou. 2018. “Teacher Perceptions of Inclusive Education in the Cook Islands.” Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education 47 (1): 81–94. doi:10.1080/1359866x.2018.1437119.

- Page, A., S. Mavropoulou, and I. Harrington. 2020. “Culturally Responsive Inclusive Education: The Value of the Local Context.” International Journal of Disability, Development and Education 67 (3): 1–14. doi:10.1080/1034912X.2020.1757627.

- Page, A., J. Anderson, P. Serow, E. Hubert, and O’Donnell-Ostini. 2021. “Creating Inclusive Classrooms in the Pacific Region: Working in Partnership with Teachers in the Republic of Nauru to Develop Inclusive Practices.” In Instructional Collaboration in International Inclusive Education Contexts, edited by S. Semon, D. Lane, P. Jones, and C. Forlin, Vol. 17. 7–22. Bingley, Emerald. doi:10.1108/S1479-363620210000017003.

- Panapa, T. (2014). Ola Lei: Developing healthy communities in Tuvalu [ Doctoral dissertation, Auckland University].

- Pérezts, M., J.-A. Russon, and M. Painter. 2020. “This Time from Africa: Developing a Relational Approach to values-driven Leadership.” Journal of Business Ethics 161 (4): 731–748. doi:10.1007/s10551-019-04343-0.

- Picton, C., and R. Tufue-Dolgoy. 2018. “Designing Futures of Identity: Navigating Aagenda Collisions in Pacific Disability.” In Indigenous and Decolonizing Studies in Education, edited by L. Tuhiwai Smith, E. Tuck, and K. Wayne Yang, 189–203, New York,Routledge.

- Reynolds, M. 2016. “Relating to Va: Re-viewing the Concept of Relationships in Pasifika Education in Aotearoa New Zealand.” AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples 12 (2): 190–202. doi:10.20507/AlterNative.2016.12.2.7.

- Rhodes, D. 2014. Capacity across Cultures: Global Lessons from Pacific Experiences. New York, Inkshed Press Pty Limited.

- Robertson, S. L. 2012. “Researching Global Education Policy: Angles in/on/out.” In Global Education Policy and International Development: New Agendas, Issues and Policies, edited by A. Verger, M. Novelli, and H. K. Altinyelken, 33–51, London, Continuum Publishers.

- Rosenfield, S. 2008. “Best Practice in Instructional Consultation and Instructional Consultation Teams.” Best Practices in School Psychology 5: 1645–1660.

- Sayed, Y., and K. Moriarty. 2020. “SDG 4 and the ‘Education Quality Turn’: Prospects, Possibilities, and Problems.” In Tensions, Threats, and Opportunities in the Sustainable Development Goal on Quality Education, edited by A. Wulff, 194–213. Leiden, Brill Sense. doi:10.1163/9789004430365_009.

- Scaglion, R. 2015. “History, Culture, and Indigenous Education in the Pacific Islands.” In Indigenous Education, edited by W. J. Jacob, S. Y. Cheng, and M Porter, 281–299, Dordrecht, Springer.

- Sharma, U., C. Forlin, J. Deppeler, and G. Yang. 2013. “Reforming Teacher Education for Inclusion in Developing Countries in the Asia Pacific Region.” Asian Journal of Inclusive Education 1 (1): 3–16.

- Sharma, U., T. Loreman, and S. Macanawai. 2015. “Factors Contributing to the Implementation of Inclusive Education in Pacific Island Countries.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 20: 1–16. doi:10.1080/13603116.2015.1081636.

- Sharma, U., C. Forlin, M. Marella, B. Sprunt, J. Deppeler, and F. Jitoko. 2016. “Pacific Indicators for Disability-Inclusive Education: The Guidelines Manual.” https://www.monash.edu/education/research/projects/pacific-indie/outcomes/docs/pacific-indie-report.pdf

- Sharma, U., T. Loreman, and J. Simi. 2017. “Stakeholder Perspectives on Barriers and Facilitators of Inclusive Education in the Solomon Islands.” Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs 17 (2): 143–151. doi:10.1111/1471-3802.12375.

- Sharma, U., A. C. Armstrong, L. Merumeru, J. Simi, and H. Yared. 2019. “Addressing Barriers to Implementing Inclusive Education in the Pacific.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 23 (1): 65–78. doi:10.1080/13603116.2018.1514751.

- Sharma, U. 2020. “Inclusive Education in the Pacific: Challenges and Opportunities.” Prospects 49 (3): 187–201. doi:10.1007/s11125-020-09498-7.

- Slee, R. 2018. Inclusion and education: Defining the scope of inclusive education. http://disde.minedu.gob.pe/bitstream/handle/MINEDU/5977/Defining%20the%20scope%20of%20inclusive%20education.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- Smith, L. T. 2021. Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples. London, Zed Books.

- Soja, E. 1996. Journeys to Los Angeles and Other Real-And-Imagined Places. Malden, Blackwell.

- Sprunt, B., J. Deppeler, K. Ravulo, S. Tinaivunivalu, and U. Sharma. 2017. “Entering the SDG Era: What Do Fijians Prioritise as Indicators of disability-inclusive Education.” Disability and the Global South 4 (1): 1065–1087.

- Stubbs, S. 2008. Inclusive Education. Where There are Few Resources? Oslo, Atlas Alliance Publishers.

- Thaman, K. H. 2008. “Nurturing Relationships and Honouring Responsibilities: A Pacific Perspective.” In Living Together, edited by S. Majhanovich, C. Fox, and A. P. Kreso, 173–187, Dordrecht, Springer.

- Thaman, K. H. 2009. “Towards Cultural Democracy in Teaching and Learning with Specific References to Pacific Island Nations (Pins).” International Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning 3 (2): 1–11. doi:10.20429/ijsotl.2009.030206.

- Thaman, K. H. 2014. “No Need to Whisper: Reclaiming Indigenous Knowledge and Education in the Pacific.” In Whispers and Vanities: Samoan Indigenous Knowledge and Religion, edited by T. Suaalii-Sauni, M. A. Wendt, N. F. V. Mo’a, R. Va’ai, and S. Filipo, 301–314, Wellington, Huia.

- Tones, M., H. Pillay, S. Carrington, S. Chandra, J. Duke, and R. M. Joseph. 2017. “Supporting Disability Education through a Combination of Special Schools and disability-inclusive Schools in the Pacific Islands.” International Journal of Disability, Development and Education 64 (5): 497–513. doi:10.1080/1034912X.2017.1291919.

- UNESCO. 1994. “The Salamanca Statement and Framework for Action on Special Needs Education.” Adopted by the world conference on special needs education: Access and quality. Salamanca, UNESCO.

- UNESCO. 2015. Education 2030. Incheon Declaration and Framework for Action. Incheon, UNESCO. http://uis.unesco.org/sites/default/files/documents/education-2030-incheon-framework-for-action-implementation-of-sdg4-2016-en_2.pdf

- UNESCO. 2018. Paving the Road to Education: A target-by-target Analysis of SDG 4 for Asia and the Pacific. UNES. http://sdghelpdesk.unescap.org/e-library/paving-road-education-target-target-analysis-sdg-4-asia-and-pacific

- United Nations. 2015. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. United Nations. https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/post2015/transformingourworld

- United Nations. 2016. “Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities: General Comments No. 4.” United NationsS. https://tbinternet.ohchr.org/_layouts/15/treatybodyexternal/Download.aspx?symbolno=CRPD/C/GC/4&Lang=en

- United Nations. 2018. “Sustainable Development Goals.” United Nations. https://sdgs.un.org/goals

- United Nations. 2020. Policy Guidelines for Inclusive Sustainable Development Goals. New York, United Nations.

- United Nations General Assembly. 2006. Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. New York, United Nations. https://www.un.org/esa/socdev/enable/rights/convtexte.htm

- Wendt, A. 1999. “Afterword: Tatauing the post-colonial Body.” In Inside Out: Literature, Cultural Politics, and Identity in the New Pacific, edited by V. Hereniko and R. Wilson, 399–412, Oxford, Rowman & Littlefield.

- Williams, S. A., and M. L. Staulters. 2014. “Instructional Collaboration with Rural Educators in Jamaica: Lessons Learned from an International Interdisciplinary Consultation Project.” Journal of Educational and Psychological Consultation 24 (4): 307–329. doi:10.1080/10474412.2014.929968.

- World Health Organization. 2011. World report on disability 2011. World Health Organization.

- Zeichner, K. 2010. “Rethinking the Connections between Campus Courses and Field Experiences in College- and university-based Teacher Education.” Journal of Teacher Education 61 (1–2): 89e99. doi:10.1177/0022487109347671.

- Zembylas, M. 2017. “Re-contextualising Human Rights Education: Some Decolonial Strategies and pedagogical/curricular Possibilities.” Pedagogy, Culture & Society 25 (4): 487–499. doi:10.1080/14681366.2017.1281834.