ABSTRACT

In addition to crossing state lines, networks of natural gas transmission pipelines in the US cross multiple local jurisdictions, each potentially with its own local comprehensive plans and zoning ordinances. Under federal preemption, these interstate pipeline projects present new challenges to local land use planning. We examine aspects of the planning process of a portion of an interstate natural gas transmission pipeline in Ohio. The goal of this research is to explore how local planners navigate the interstate pipeline planning process under the limitations they face due to the regulatory framework in which these projects exist.

Introduction

Increased interest in natural gas development in the U.S. has meant intensification of hydraulic fracturing, or fracking. Infrastructure, in the form of transmission pipelines, is needed to move the natural gas from source sites to distribution networks and out to market. These pipeline systems are generally owned and operated by private companies and can extend hundreds of miles from the drilling source. They cross local jurisdictional and state lines across the U.S., and, in some cases, international borders. There are over 300,000 miles of interstate and intrastate natural gas transmission pipelines throughout the U.S. (U.S. EIA, n.d.).

The federal government, through the Department of Energy’s Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC), is responsible for interstate pipeline approvals. Local governments are largely excluded from direct, proactive involvement in the approval and development process for the private pipeline entity. At the same time, local governments have individual comprehensive plans and zoning ordinances to manage land within their jurisdictions into the future. Land use changes related to the natural gas market extend beyond drilling and development to include pipeline infrastructure siting and resulting rights-of-way, which impact and may be incompatible with current and future local land use planning efforts.

The impacts of pipeline siting and construction on local planning efforts and wider impacts on land use governance across jurisdictions in the U.S. are largely unknown. This study builds on previous work and asks: what are the impacts of an interstate natural gas pipeline planning process on local land use planning, and do they prompt a collaborative interjurisdictional response from affected planning communities? Related questions left unanswered in the planning literature and for practitioners, in general, include what role, if any, do local planners and comprehensive plans play in the interstate pipeline planning process (e.g. before pipeline construction)? and, what land use planning challenges do local planners encounter with respect to these proposed private interstate pipeline projects?

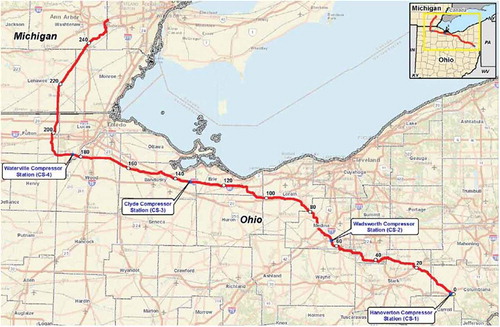

This paper is an exploratory analysis of planning and collaborative efforts between planning departments, government entities, and the private pipeline company before construction. The objective is to gain an understanding of experiences of planning professionals with the pipeline planning process for one section of an interstate natural gas pipeline project. We focus on the Ohio section of the FERC-approved interstate NEXUS natural gas transmission pipeline. The route begins in eastern Ohio, traveling northwest through Michigan and into Canada (Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC), Citation2016, EIS, p. 2), see . To address the research question, we used a targeted interview instrument of selected local professional planners and related departments in Ohio municipalities, townships, and counties along the proposed NEXUS pipeline route prior to construction. With the expansion of such pipeline infrastructure networks across the U.S. and applications for new projects currently under FERC review, planners need to be aware of the connections between land use and energy issues and understand the potential for local land use impacts and conflicts related to such pipeline projects (as called for by Kaza & Curtis, Citation2014).

Figure 1. NEXUS route through Ohio and Michigan (Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC), Citation2016, p. 2–2)

The first section of this study describes natural gas transmission pipelines in the U.S., as well as the regulatory context in which they exist in relation to local land use planning. A review of the literature follows, with a focus on interjurisdictional collaboration and private governance considerations, situating the interstate natural gas pipeline planning conversations within this framework. Next, we describe the study area, methods, and results of our study of an interstate pipeline planning process in Ohio. The paper ends with a discussion and direction for future land use planning and pipeline siting research.

Interstate Natural Gas Transmission Pipelines

Natural gas transmission pipelines transport gas from development and production sites to distribution for transport to market. The interstate regulations for moving natural gas across state lines fall under federal government authority through FERC. When in operation, safety issues are regulated at the federal level within the Pipeline and Hazardous Material Safety Administration (PHMSA) Office of Pipeline Safety (OPS), under the U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT) (U.S. Department of Transportation, Citation2018). State-level agencies regulate intrastate pipelines, as well the drilling activities in the development stages. Designated state agencies are also required to conduct inspections and enforcement of intrastate pipelines based on PHMSA OPS safety regulations (U.S. Department of Transportation, Citation2018). Some states are also certified by OPS to inspect interstate pipelines within state boundaries. For example, the Public Utilities Commission of Ohio regulates intrastate pipelines and is also able to inspect interstate natural gas transmission pipelines within Ohio.

Federal power over interstate pipeline projects was established by the Natural Gas Act of 1938 (Earle, Citation2017). As the federal government agency that regulates interstate transmission activities, FERC ‘approves the location, construction and operation of interstate pipelines, facilities and storage fields involved in moving natural gas across state boundaries’ (Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC), Citation2016, p. 4). A company that intends to construct an interstate pipeline must submit an application to FERC, who then completes an Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) or Environmental Assessment based on the proposed route as predetermined by the company, as required under the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) (Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC), Citation2016, p. 4). FERC Commissioners then decide if the proposed project is a ‘public convenience and necessity’ based on ‘weighing factors such as the proposal’s market support, economic, operational, and competitive benefits, and environmental impacts’ in order to move forward with issuing a certificate (Earle, Citation2017, p. 715). Moving into the construction phase requires a ‘Notice to Proceed’ which is also determined by FERC. The 1938 Act also gives private pipeline companies the power of eminent domain after FERC approval (Warner & Shapiro, Citation2013; Earle, Citation2017), essentially upending land use planning intentions set forth in local comprehensive plans.

The role of the state-level governments in the interstate pipeline process is mainly that of permitting projects post-FERC approval. State power is limited to certification processes authorized by the Clean Water Act, Coastal Zone Management Act, and Clean Air Act (Kooistra, Citation2015; Murrill, Citation2016). For example, Section 401 of the Clean Water Act (CWA) requires pipeline companies to apply for Water Quality Certificates at the state level (Kooistra, Citation2015). Such certification and permitting are generally the only oversight that states are authorized in interstate pipeline planning. Under a 2017 FERC order, states cannot delay permitting as a potential means of blocking pipeline construction (Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC), Citation2017). This came about when the New York Department of Environmental Conservation requested more information to complete the CWA certification, and then denied the CWA certification for the Millennium Pipeline Project almost two years later (Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC), Citation2017). FERC intervened to uphold a one-year allowance for CWA approvals at the state level, noting that New York waived any authority provided to the state agency under the CWA (Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC), Citation2017).

Recent large-scale pipeline infrastructure projects, like the Dakota Access and Keystone XL projects, in the U.S. have been contentious. Protest and legal battles have brought to public attention the determination of proposed routes, the power of eminent domain by private companies, and the overall FERC approval process. This also was the case with the proposed NEXUS route in Ohio, the focus of this study.

Local governments and other stakeholders have two public comment opportunities in the pipeline process: through the EIS process and state certification processes. FERC also encourages companies to ‘start early, be pro-active, [and] involve key stakeholders’ in the pipeline planning process through identifying and communicating with state and local agencies, such as state environmental agencies, planning and zoning boards, and local councils (Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC), Citation2001, p. 4). While this prescription seeks to address concerns regarding stakeholder involvement and improved coordination with local governments, it is unclear whether and how local planners are involved in such pipeline planning processes. Understanding how local land use planning issues are considered for these extensive projects is important for planners and local governments alike. Important to practitioners are implications for comprehensive planning and local zoning by both the private company’s decision-making during the pipeline planning process as well as physical considerations for future land uses after natural gas transmission pipelines are constructed.

Literature Review

Our research attempts to expand such land use-energy discussions in planning literature and practice by examining the pipeline planning process and its impacts, including interjurisdictional collaboration and issues of private governance. In this section, we begin with a review of planning literature related to local regulation of natural gas development and land use considerations for natural gas pipeline infrastructure projects. Next, we examine governance issues for pipeline planning processes and risk management, including collaboration across jurisdictions and the role of planners in these instances. The section closes with a review of private governance from public policy literature and its connection to interstate pipeline projects.

Natural Gas Infrastructure and Planning

On the development side of natural gas extraction, planning-related research focused on the adoption of fracking policies by local governments. In a survey of communities in states with active fracking operations, Loh and Osland (Citation2016) found that, as of their study, over half of the communities included in the survey did not have policies related to fracking activities or its impacts. While the authors found that the lack of local policies was not related to state-level government prevention (Loh & Osland, Citation2016), other studies indicated that fracking-related policies can be influenced by state-level regulations, which vary by state, and in some cases, can attract divisive political pressure between state and local governments (Warner & Shapiro, Citation2013; Davis, Citation2014).

Local governments that have tried to regulate fracking and related waste disposal within their jurisdictions have had mixed success. A related study of land use policies and fracking in Texas highlighted home rule cities (i.e. those provided self-government power under state constitutions) as having more flexibility to enact regulations (e.g. zoning requirements) for fracking and related issues from drilling activities than places without home rule; however, this is not the case for all home rule states, as the extent of power to regulate such activities can be questioned and curtailed by state energy commissions and state-level governments (Davis, Citation2014). In other instances, state-level regulation has impacted the role of local governments in regulating fracking through related land use and zoning practices. Local governments in Pennsylvania and New York have successfully overturned state requirements that would allow fracking in places banned by local zoning ordinances (Warner & Shapiro, Citation2013). On the other hand, in Ohio, legal rulings regarding fracking activities have largely overruled local governments’ arguments for protection under home rule (State ex rel. Morrison v. Beck Energy Corp., Citation2015; State ex rel. Walker v. Husted, Citation2015).

The few studies in planning-specific literature that focused directly on natural gas pipelines examined the issue from a risk management and hazard mitigation perspective (Osland, Citation2013, Citation2015). For pipeline safety measures, states are responsible for safety inspections of interstate pipelines, and local governments must develop land use tools to protect the community and the environment post-construction. Land use tools commonly associated with such efforts were found to be in the form of regulations, informative notifications, and/or incentives, and these efforts took place mainly at the local-level (Osland, Citation2013). Among the 85 North Carolina communities that Osland (Citation2013) surveyed, land use tools were limited in use and those that were used ultimately required less input from planning departments and more from the private sector. Thus, planning literature has focused on extraction or development-related implications for local governments and land use planning, as well as safety measures for places with established pipeline networks. Instead, in this research, we sought to understand the pre-construction planning process for interstate pipelines.

Governance and Collaboration

The scale of natural gas pipeline infrastructure projects presents governance complexities for land use planning under siting decisions and for safety post-construction. Collaborative governance processes bring together stakeholders and government representatives (at various levels) for consensus-based decision-making (Ansell & Gash, Citation2008). Within resource management, consensus-based decision-making literature highlights examples of successful outcomes from collaborative governance networks and interjurisdictional collaboration (see among others: Nunn & Rosentraub, Citation1997; Ansell & Gash, Citation2008). Interactions among diverse stakeholders also allow for information sharing that otherwise might not be available. For technical issues, like those related to pipeline safety, broad stakeholder participation might be difficult due to the lack of interest and lower prioritization by local governments (Osland, Citation2013).

In a similar infrastructure project, Späth and Scolobig (Citation2017) examined stakeholder participation and empowerment in electricity transmission line planning and siting decisions in France and Norway. The authors emphasized how participation can ‘smooth the planning process, decrease opposition, [and] diffuse conflicts’ (Späth & Scolobig, 2017, p. 189). An important finding of the study was that participation and empowerment have the most impact early in the planning process. Equally important is the level of stakeholder participation and empowerment which can vary from simply providing information to full stakeholder involvement in the planning process (Späth & Scolobig, 2017). This is similar to the natural gas pipeline transmission project guidance and suggestions from FERC to the private pipeline companies, which recommends early stakeholder participation and building consensus among stakeholders in the FERC pre-filing, planning, and approval periods (Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC), Citation2001).

Interjurisdictional collaboration between governments and sectors can involve agreements, projects across jurisdictions, and in the establishment of organizations consisting of multiple jurisdictions (Nunn & Rosentraub, Citation1997). This can be materialized through common objectives. Further, Kim and Jurey (Citation2013) noted that planning-related coordination across jurisdictions can be powerful, especially when planners come to ‘better understand the full advantages and disadvantages of their governance structures’ (p. 120). Collaboration can be examined vertically (local, state, and federal government integration) and horizontally (across municipalities or organizations). Vertical collaboration can also emerge through connections between community members and organizations and agencies. In the case of natural gas pipeline infrastructure, the private companies operating the networks are required to ‘make efforts to increase public awareness of pipelines and potential safety issues’ (Scott & Scott, Citation2019, p. 333). Additionally, the strength of vertical and horizontal coordination has been found to impact resiliency in hazard mitigation and recovery after a disaster (Berke & Smith, Citation2009; Smith & Birkland, Citation2012). In these instances, increased vertical and horizontal collaboration between groups, departments, governments, policies, and plans can provide more detail into issues and needs at the local level (Smith & Birkland, Citation2012).

Interstate pipeline planning is an example of a planning process that has ‘important land use dimensions but [is] traditionally led by non-planning professionals’ (Lyles et al., Citation2013, p. 16). Lyles et al. (Citation2013) demonstrated the importance of local planner involvement in hazard mitigation planning processes (another example of such planning process not typically led by planners); the authors noted that planner involvement brings local and technical knowledge about land uses and policy practicality. This can be extended to the case of pipeline infrastructure project, where planners’ technical knowledge can provide for robust discussions early in project development, especially related to local and regional land use issues for route determination, and inter-jurisdictional discussions along the pipeline route. For example, in terms of vertical integration, planning skills are well suited in instances of outreach to/from landowners, assessing local needs, and for connecting local land use and development issues to the state agencies and pipeline companies along proposed pipeline routes.

Specific to established natural gas pipeline infrastructure, studies have examined collaboration in terms of hazard mitigation and safety management for transmission and distribution pipelines already in operation (Osland, Citation2015; Scott & Scott, Citation2019). The interstate pipeline siting and approval processes are a precursor to the hazard mitigation and safety concerns addressed in the post-construction environment. Pipeline safety programs at the state level, that are funded by grants from the federal government, increasingly stress collaboration and public education as main objectives for safety programming (Scott & Scott, Citation2019). Scott and Scott (Citation2019) contend that collaboration in pipeline safety management is challenging due to ‘technical uncertainties,’ like pinpointing pipeline locations, garnering necessary information from different stakeholders, and collecting detailed data in the case of safety program spending (p. 344). Additionally, stakeholders’ views and assessments of uncertainty and risk creates additional challenges for safety planning efforts (Scott & Scott, Citation2019).

Private Governance

Governance complexities and challenges associated with natural gas pipeline infrastructure are amplified by decisions made by private entities. Research on private governance in the field of public policy also provides a base for this examination of the interstate pipeline planning process and related implications for local land use planning. The idea of private governance is separated from public–private partnerships commonly exercised by planning practitioners in that ‘decisions are made wholly or in part by private entities’ and these decisions impact the public (Rudder, Citation2008, p. 901). Rudder et al. (Citation2016) argued that private governance is often evident in standard setting, and provide examples such as LEED accreditation, which is a current topic in planning and urban design. LEED standards are created and set by the U.S. Green Buildings Council, a private organization. The certification system for green buildings has been mandated by some local governments across the U.S. for new construction, for both public and private construction; in addition, local governments can provide incentives to construct and maintain LEED accredited buildings measurable by the standards set by this private organization (Retzlaff, Citation2009).

Rudder et al. (Citation2016) also maintain that decisions in the public realm made by private groups can be ‘authoritative,’ ‘affect a broader public,’ and ‘have a substantial impact’ (p. 14). These three elements are evident in the case of natural gas pipelines, especially those with routes through undeveloped land, crossing multiple jurisdictions and states lines. The power granted to private companies through both the Natural Gas Act of 1938 (e.g. power of eminent domain) and decision-making influence through the permitting process under FERC (e.g. routes), are examples of the authoritative power of private pipeline companies. Next, the siting decisions for rights-of-way and the resulting risk and hazard mitigation standards that accompany pipeline construction highlight the potential impacts to the public as a result of these generally private decisions. As described above, private companies propose routes, which in some cases alter the potential use of previously undeveloped land and acquire new temporary and permanent easements, as is the case for greenfield pipelines, like the interstate transmission pipeline at the center of this research. In terms of the impact of pipeline projects, the planning and construction phases both ‘exert influence across sectors, industries, and territories’ (Rudder et al., Citation2016, p. 15). Moreover, ‘private participation’ in agreements for rights-of-way and easements takes place between landowners and pipeline companies, influencing local land use decisions beyond the purview of planners and local governments (Jacquet, Citation2015). This limited ‘public’ stakeholder participation coupled with the lower urgency of hazard mitigation by local governments (Osland, Citation2015) presents new challenges for land use planning post-construction.

The role of private pipeline companies and the federal oversight in decisions impacting local land use planning has not been fully examined within planning literature. Land use planning issues related to natural gas development and transmission pipeline hazard mitigation provide insight into local government power in this domain; however, the role of local land use plans and policies in relation to interstate pipeline planning is less understood. Under the FERC certification process for these interstate projects and powers provided to private companies under the Natural Gas Act, the power of local governments and related planning departments to make route adjustments based on existing planning documents is uncertain.

Further, the private decisions of the pipeline company contradict traditional public planning processes and raise the potential of multiple jurisdictions facing similar impacts of the same pipeline. Therefore, more information is needed about the role of interjurisdictional collaboration during the pipeline planning process. As related to assessing collaboration horizontally and vertically, our research considers the role of planning professionals in natural gas pipeline planning processes, as the ‘technical experts’ (following Osland, Citation2015) for local land use planning dimensions. Understanding implications for land use governance associated with such pipeline infrastructure projects is also key to the research at hand.

Study Area

The study area for this research included the Ohio section of the (at the time the time of the study) proposed NEXUS natural gas transmission pipeline. The pipeline runs approximately 255 miles through Ohio and Michigan, with most of the pipeline, about 210 miles in length, located within Ohio (Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC), Citation2016). The route begins in Hanoverton, a village in eastern Ohio and continues to northwestern Ohio, crossing the border with Michigan through Fulton County, Ohio (Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC), Citation2016). It transects parts of 13 counties and numerous local municipalities, townships, and unincorporated areas in Ohio. The pipeline is underground, 36 inches in diameters, and transports up to 1.5 billion cubic feet of natural gas per day through Ohio (Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC), Citation2016). The proposed route also included four above-ground compressor stations in Ohio, in Hanoverton, Wadsworth, Clyde, and Waterville (Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC), Citation2016).

As an interstate pipeline, the project required federal approvals. The initial application for the NEXUS pipeline was submitted to FERC in November of 2014, and the final environmental impact statement (EIS) was filed in November of 2016 (Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC), Citation2016). FERC issued its final approvals in late August 2017 for pipeline construction (Ohio Environmental Protection Agency (Ohio EPA), Citation2017). Following the federal application process, the company sought permits from the Ohio EPA for water quality certification and was approved by the Ohio EPA in September 2017. As of the end of 2018, the pipeline is in operation and transporting natural gas through Ohio.

The NEXUS pipeline project was contentious with opposition from landowners, residents, environmental groups, and local and county governments. Public comment opportunities are required during the EIS/EA period, in addition to public notice during state certification period (i.e. CWA Section 401 certification). In Ohio, the City of Green, through its Planning Department, proposed alternative routes and included these in public comments to the EIS through FERC (Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC), Citation2016). In addition to submitting comments during these periods, some local governments, groups, and individual landowners sought legal avenues to fight the proposed FERC approval and land taking for rights-of-way under eminent domain. Despite the availability for comment and public meetings held by FERC, Ohio EPA, and NEXUS, these local stakeholders viewed legal recourse as the best available option to challenge the pending pipeline construction.

In addition to the lawsuits against the pipeline company, the Sierra Club, Coalition to Reroute NEXUS, the City of Oberlin, Communities for Safe and Sustainable Energy, and Sustainable Medina County requested a rehearing of the August 2017 approval by FERC (Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC), Citation2018). The main arguments for the request for the rehearing were that the EIS did not consider climate change and greenhouse gas emissions; there was no public need for the project; and objections to eminent domain authority (Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC), Citation2018). In July 2018, FERC denied the rehearing of the NEXUS certification, in a majority vote (3–2), with two FERC Commissioners dissenting (Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC), Citation2018).

In July 2018, during pipeline construction, 20,000 gallons of drilling fluid were discharged into a tributary to the Maumee River prompting an Ohio EPA violation (Ohio Environmental Protection Agency (Ohio EPA), Citation2018). The Maumee River runs north 20 miles to Toledo and into Lake Erie, a major source of drinking water for the region. The Ohio EPA issued a violation and fined NEXUS for the discharge (Ohio Environmental Protection Agency (Ohio EPA), Citation2018). As of the end of 2018, the remaining local governments (plaintiffs) settled with the pipeline company and dropped lawsuits challenging the route and construction. Settlements included monetary compensation from the pipeline company and safety agreements; in particular, one city is to receive 7.5 USD million in the settlement for safety measures for city land in proximity to the pipeline, mainly parks and recreation areas (City of Green, Ohio, Citation2018a). Additional lawsuits continue post-construction, with landowners suing the pipeline company and contractors for property damage (Hoover, Citation2018).

Methods

The research design for the study included a targeted interview instrument and follow-up phone interviews with willing participants. We sent the online instrument to planning and zoning directors in eight municipalities and townships as well as all 13 counties along the proposed route in Ohio. Three of the municipalities were chosen based on the location of the proposed compressor stations along the route, due to the similar distances between the proposed locations for the stations. While there are four proposed stations, one of the stations is located within a village and nearby unincorporated areas that do not have local planning, zoning, or government offices. Unincorporated areas in Ohio include townships, which have the power of planning and zoning; however, many lack resources to support a planning department (Conroy & Jun, Citation2016). The remaining five municipalities and townships were chosen based on the following criteria: (a) transected by the proposed pipeline and located between the planned compressor stations; (b) has a population of at least 5,000 people (the minimum for incorporation); (c) has a planning/zoning department or a planner on city or township staff; and (d) has a comprehensive plan. The small number of cities and townships utilized in this study was due mainly to the fact that the proposed route transects many unincorporated areas with low populations and places without planning or related departments. Therefore, we included county-level planners in this study, as counties in Ohio are legally permitted to create comprehensive plans.

The 21 identified participants were invited by email to contribute through a link to the online interview instrument. Email contact information was collected online for planning and zoning directors. A reminder was sent one week after the initial invitation. Questions sought to gauge involvement in the pipeline planning process, interjurisdictional collaboration, and challenges to local planning efforts. There were 24 questions total, including: seven demographic and professional background questions; eleven questions related to jurisdictional and interjurisdictional collaboration; four questions that asked about local government involvement in the pipeline planning process; one question asking about potential challenges to local planning efforts post-construction; and one open-ended comment opportunity. Finally, participants were asked to provide contact information if they were interested in participating in a follow-up phone interview. Questions were a mix of rating scales, multiple choice, and free comment.

A total of 11 of the 21 online instrument invitations were fully completed (52% response rate). An additional three participants started the targeted interview instrument, but they did not respond to questions beyond the initial demographic/professional questions, so these were removed from the analysis. Data collected online were downloaded into Microsoft Excel for analysis. Following the targeted interviews, we conducted semi-structured phone interviews with two willing participants. Notes were transcribed after each interview. The purpose of the follow-up interview was to collect additional information about respondents’ professional experiences with the issue, based on the initial results.

Findings

The interview instrument asked respondents about their professional experiences with the NEXUS planning process and what they view as potential challenges to future land use planning efforts within their jurisdictions. Nine respondents represented county-level governments and two were from municipal-level governments. Their professional affiliations included six planning directors, one planner/GIS technician, two land development administrators, one engineer, and one conservation district manager. All but one of the jurisdictions, a county, have a comprehensive plan. These plans were completed and/or updated between 2000 and 2017. Respondents were asked about any potential updates to their comprehensive plans and if these updates would include natural gas transmission pipelines due to the challenges by local governments during the planning and FERC approval process. One county-level respondent noted that their comprehensive plan contained a chapter on or referenced natural gas transmission pipelines. The remaining respondents indicated that there are currently no scheduled updates to their plans. One respondent noted that their jurisdiction is currently updating their comprehensive plan over the next year and natural gas pipeline infrastructure will not be a part of the update.

The interview instrument addressed three broad issues for the local and county governments: involvement in the pipeline planning process, interjurisdictional collaboration, and potential challenges moving forward. Each issue will be addressed in turn highlighting the instrument responses as well as additional insights from the follow-up phone interviews where applicable.

Involvement in Pipeline Planning Process

In general, the results of the interview instrument show county and local planning and zoning departments had very minimal involvement in the pipeline planning process. Respondents overwhelmingly noted that they were not involved in the early planning process, nor did they serve as liaisons between the pipeline company and landowners, residents, or their local council members (see ). These findings are at odds with FERC guidance for pipeline planning discussed above. In terms of participation, the minimal involvement of planners in this particular pipeline planning process aligns with Späth and Scolobig (2017) ‘information’ level of empowerment, where information is simply provided to stakeholders. Additionally, most respondents noted that their professional expertise was not utilized in the planning process.

Table 1. Involvement in the pipeline planning process

Next, the participants were asked to rate the frequency of meetings with the pipeline company to specifically discuss the proposed pipeline as either regularly, ad hoc, or never from 2013 through 2017, corresponding with the year before the official filing with FERC and through the research date (September 2017). While all respondents indicated that they did not have regular meetings with the pipeline company from 2013 through 2017, the frequency of meetings, reported as ‘ad hoc,’ between the two did increase over this period, see .

Table 2. Meeting frequency between respondents and pipeline company from 2013–2017

When considering landowner and resident involvement, only one of the respondents noted their jurisdiction held a public meeting specifically to discuss the proposed pipeline. The respondent also indicated that, to their knowledge, the pipeline company did not participate in this particular meeting. The lack of public meetings initiated by local governments could be due to public meetings held by NEXUS, FERC, and Ohio EPA. Additionally, an underestimate of public meetings pertaining specifically to the proposed pipeline might be due to local council or county commission meetings in which the pipeline project might have been placed on the agenda, but the pipeline was not the sole purpose of the meeting. For example, some city councils passed resolutions opposing the pipeline project, as such a vote for a resolution might be part of a regularly scheduled city council meeting and not a separate event to solely discuss the proposed pipeline.

Interjurisdictional Collaboration

The results also show limited collaboration between jurisdictions, both horizontally and vertically, as well as between local planners and the pipeline company. When considering horizontal coordination, only two of the respondents, both cities, indicated meeting with other cities along the proposed route to discuss the pipeline. These meetings reportedly took place on an ad hoc basis from 2014 through 2017. On the other hand, from 2013 through 2017, county-level planners reported that they did not meet with other counties along the route to discuss the pipeline during the planning process, see .

Table 3. Horizontal meeting frequency from 2013–2017

In terms of vertical coordination during the planning process, the instrument included questions about meeting frequency between cities, counties, and state-level agencies. From 2013 through 2015, one county reported ad hoc meetings with cities within their county to discuss the pipeline. Three of the counties reported ad hoc meetings with cities within their county in 2016 and two in 2017. Finally, from 2015 through 2017, only one respondent noted having meetings with state agencies/departments specifically regarding the pipeline, and these were on an ad hoc basis.

Potential Challenges

Finally, questions asked about challenges for planners and local land use planning moving forward post-construction, see . Notably, most planners stated that they view continued communication with the pipeline company as a challenge moving forward. This was echoed in one of the follow-up interviews, where an interviewee viewed the pipeline company’s approach to stakeholder engagement as mainly ‘reactive’ during the planning process. Both city-level respondents stated that they see continued communication with state-level agencies and departments as at least somewhat of a challenge moving forward. It should be noted that one respondent stated that the ‘pipeline reps were very cooperative and professional’; however, this reaction was not shared by other respondents. Similarly, one respondent noted that the pipeline efforts were outside of their authority and that their department took a more ‘hands-off approach’ to the issue.

In terms of planning activities, respondents’ views of challenges post-pipeline construction were split. When asked about revising their comprehensive plans, half saw this as challenging, while the other half stated it was not a challenge or that they were unsure of the challenge. Similarly, with regulating new development near the proposed pipeline, half of the respondents noted some level of challenge for this planning effort moving forward.

Moreover, one of the interviewees noted that although their comprehensive plan might not be central to the pipeline planning process, there could be other ways to communicate with the pipeline company and provide governments with meaningful avenues to address local planning concerns. For example, the interviewee indicated that road user maintenance agreements, in which energy developers agree to maintain roads used during drilling processes, have been successful near natural gas drilling and development sites in their jurisdiction. The interviewee saw this as a successful example of vertical collaboration between the State of Ohio, county-level and local governments, and stressed positive outcomes with private pipeline company cooperation.

Discussion

We acknowledge that this exploratory analysis is limited to a small group of local governments and is not necessarily generalizable to other areas. However, the goal of this research was to bring attention to a timely issue, as more applications for similar interstate pipeline projects are under FERC review across the U.S. Our focus on the Ohio section of the NEXUS interstate natural gas pipeline examined the role of planners in the pipeline planning process, interjurisdictional collaboration horizontally and vertically during the planning process, and challenges moving forward.

Overall, we found a general lack of horizontal and vertical interjurisdictional collaboration during the planning phase of this interstate pipeline project as reported by respondents. Literature on collaborative governance and interjurisdictional coordination provided an expectation of some form of interjurisdictional collaboration between local governments along the pipeline route, as these jurisdictions were facing similar impacts of the proposed pipeline corridor. Much of the local government response involved passage of local resolutions and opposition in the form of lawsuits to challenge the proposed route. These actions appear to have lacked a coordinated land use specific response by the involved jurisdictions to the proposed pipeline corridor. Instead, martialing a likely smaller array of resources at the individual jurisdictional level. The question remains if intergovernmental coordination would have been valuable in this case given the role of FERC oversight and power provided under the Natural Gas Act.

The involvement of local agencies and departments is one of the main recommendations made by FERC to the companies preparing to file applications for interstate pipelines (Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC), Citation2001). In the case of the NEXUS pipeline, the involvement of county and local planning and zoning departments was limited during the pipeline planning process. One respondent noted that ‘federal preemption of the approval process for projects of this type render local planning efforts virtually meaningless.’ The private pipeline company has only the recommendation of FERC in terms of local involvement for siting that irrevocably impact current and future local land policy. Our findings highlight that the involvement is minimal and typically ad hoc. This runs counter to the comprehensive planning process that attempts to establish land use policy based on an overall vision established through public input.

Private governance associated with pipeline planning runs counter to the participatory ideals of local land use planning. Because these pipelines transect multiple jurisdictions, and local governmental power is limited through FERC oversight, participation considerations are not isolated and local. We found that for the interstate pipeline project at hand, the role of local comprehensive plans and zoning ordinances was largely missing from the private pipeline planning process. The Environmental Impact Statements and Environmental Assessments do provide information for current land uses that would be impacted by the proposed route. However, it appears as though local comprehensive plans and related future land uses are expected to be rewritten post-pipeline construction to accommodate the route as determined by the pipeline company.

While the private governance process highlighted through examining this portion of the pipeline project in Ohio presented a situation that generally overlooked existing comprehensive plans, it must be noted that Ohio is not a comprehensive plan mandate state. As a result, we hypothesized that the strength of comprehensive plan policies in states with planning mandates might give local governments a more meaningful seat at the table. Thus, we attempted to replicate our study in Florida, a comprehensive plan mandate state, for a similar transmission pipeline project, the Sabal Trail. Due to a limited response (2 out of 19), we were unable to include further details. However, the responses received noted little coordination between jurisdictions and that local planning involvement remains limited under FERC’s authority.

As a result, there are opportunities for future research to include comparisons across pipeline projects in other states, and for further investigations into the impacts on local zoning and comprehensive planning post-construction. The route determination and reported lack of consultation with local comprehensive plan documents suggest that impacts for local land use planning center on updating comprehensive plans and creating policies focused on safety and hazard mitigation. Such influences on local land use planning efforts as a result of the interstate pipeline planning process is an issue that should be examined in future studies, especially those looking at the post-construction environment of such pipeline infrastructure projects in the U.S. and internationally.

These natural gas infrastructure projects come with new responsibilities for local governments in the form of risk management and hazard mitigation efforts for pipeline routes determined by private companies and approved by FERC. Ultimately, resulting risk management and land use planning related to hazard mitigation post-construction are directly impacted by the decisions made during the pipeline planning process by private pipeline companies. For example, land use related guidance from the Pipelines and Informed Planning Alliance (Citation2010), sponsored by the U.S. Department of Transportation, provided best practices for land use decision-making in proximity to such pipelines. Planning-related issues include dealing with easements, updating zoning ordinances and comprehensive plans, and creating new development requirements and restrictions near transmission pipelines, and would thus be the expected focus of future land use planning responses to such new infrastructure. In the case of the NEXUS project, one city’s legal settlement with the pipeline company indicated that the agreement allows the city to ‘review, monitor and enforce policies to ensure the health, safety, and welfare of our residents’ set through local ordinances (City of Green, Ohio, Citation2018b). Further, the city indicated that as a result of the financial settlement they are able to ‘relocate’ public facilities that are close to the pipeline corridor (City of Green, Ohio, Citation2018b). Thus, it is evident that the implications for local planning practice will surface after pipeline construction.

Such a reactive response by local governments for pipeline projects that might contradict established local comprehensive plans and ordinances. The impact on future land uses are also echoed in Federal Technical Assistance Grants available to communities (Scott & Scott, Citation2019). These grants allow communities in proximity to pipelines to focus on local and regional safety measures (Scott & Scott, Citation2019). While decision-making regarding a community’s pipeline safety measures and related land use planning efforts takes place locally, natural gas pipeline infrastructure projects like the NEXUS case are not bound within a single municipality. Therefore, future research might also seek to address the connections between collaboration during the planning process and continued collaboration for safety and risk management programs for jurisdictions transected by newly constructed pipelines.

In the case of natural gas pipelines, planners can offer local insight and expertise into pipeline planning conversations that involve issues such as route determination, current, and future land uses, and planned developments. However, the permitting process under the Natural Gas Act and as overseen by FERC allows for route determination and siting by private companies often with local input limited to public meetings or public comment periods under NEPA required EIS or EA processes. The power provided to these private pipeline companies under the Natural Gas Act of 1938 comes with limited local influence under federal preemption (Murrill, Citation2016). Moving forward the role of the planner and land use planning efforts will be increasingly important post-construction, especially in places where pipelines will cross sensitive environmental areas or land slated for future development. Future planning research needs to assess land use governance within and across jurisdictions (for both intrastate and interstate projects), especially in instances of greenfield pipelines, like the Ohio portion of the NEXUS pipeline.

This research sought to understand the role of planners in an interstate natural gas pipeline planning process and highlighted how local governments must navigate these pipeline planning efforts under the limitations they face due to the regulatory framework in which these infrastructure projects exist. Thus, local governments should start to consider future land use tools and options for collaboration across jurisdictions for the post-construction environment. Further, future studies of similar pipeline planning efforts and construction activities are needed to continue and expand the research on land use-energy connections in planning.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Ansell, C., & Gash, A. (2008) Collaborative governance in theory and practice, Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 18(4), pp. 543–571. doi:10.1093/jopart/mum032

- Berke, P., & Smith, G. (2009) Hazard mitigation, planning, and disaster resiliency: Challenges and strategic choices for the 21st century, in: U. F. Paleo (Ed) Building Safer Communities. Risk Governance, Spatial Planning and Responses to Natural Hazards, pp. 1–20. (Amsterdam: IOS Press). doi:10.3233/978-1-60750-046-9-1)

- City of Green, Ohio (2018a) NEXUS pipeline information. Available at https://www.cityofgreen.org/nexus-pipeline-information (accessed 2 February 2019).

- City of Green, Ohio (9 February 2018b) NEXUS settlement agreement fact sheet. Available at https://www.cityofgreen.org/DocumentCenter/View/409/Settlement-Agreement-Fact-Sheet-PDF.

- Conroy, M. M., & Jun, H.-J. (2016) Planning process influences on sustainability in Ohio township plans, Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 59(11), pp. 2007–2023. doi:10.1080/09640568.2015.1103709

- Davis, C. (2014) Substate federalism and fracking policies: Does state regulatory authority trump local land use autonomy?, Environmental Science & Technology, 48(15), pp. 8397–8403. doi:10.1021/es405095y

- Earle, C. (2017) Survey Says …? An argument for more frontloaded FERC public use provider determinations as a means of streamlining the Commission’s regulatory role over interstate natural gas pipeline operators, William & Mary Environmental Law and Policy Review, 41(3), pp. 711–749. Article 8.

- Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) (2001) Ideas for better stakeholder involvement in the interstate natural gas pipeline planning pre-filing process: industry, agencies, citizens, and FERC staff. Office of Energy Projects Gas Outreach Team. Available at https://www.ferc.gov/sites/default/files/2020-05/stakeholder.pdf (accessed 28 August 2017).

- Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC). (2016) Final Environmental Impact Statement: NEXUS as Transmission Project and Texas Eastern Appalachian Lease Project (Washington, DC: Office of Energy Projects FERC/FEIS-270F).

- Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) (2017) Declaratory Order Finding Waiver Under Section 401 of the Clean Water Act. 160 FERC 61,065 (issued 15 September 2017).

- Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) (2018) Order on rehearing. 160 FERC 61,065. (issued 25 July 2018).

- Hoover, S. (6 December 2018) Lawsuits allege damage from NEXUS pipeline. Akron Beacon Journal. Available at https://www.ohio.com/news/20181206/lawsuits-allege-damage-from-nexus-pipeline (accessed 19 January 2019).

- Jacquet, J. B. (2015) The rise of “private participation” in the planning of energy projects in the rural United States, Society & Natural Resources, 28(2), pp. 231–245. doi:10.1080/08941920.2014.945056

- Kaza, N., & Curtis, M. P. (2014) The land use energy connection, Journal of Planning Literature, 29(4), pp. 355–369. doi:10.1177/0885412214542049

- Kim, J. H., & Jurey, N. (2013) Local and regional governance structures: Fiscal, economic, equity, and environmental outcomes, Journal of Planning Literature, 28(2), pp. 111–123. doi:10.1177/0885412213477135

- Kooistra, R. (2015) How FERC confuses the role of state and local authorities in regulating certified natural gas pipelines, The George Washington University Journal of Energy and Environmental Law, 6(1), pp. 59–68.

- Loh, C. G., & Osland, A. C. (2016) Local land use planning responses to hydraulic fracturing, Journal of the American Planning Association, 82(3), pp. 222–235. doi:10.1080/01944363.2016.1176535

- Lyles, L. W., Berke, P., & Smith, G. (2013) Do planners matter? Examining factors driving incorporation of land use approaches into hazard mitigation plans, Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 57(5), pp. 792–811. doi:10.1080/09640568.2013.768973

- Murrill, B. (2016) Pipeline transportation of natural gas and crude oil: Federal and state regulatory – authority. Congressional Research Service. R44432. Available at http://www.fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R44432.pdf (accessed 28 August 2017)

- Nunn, S., & Rosentraub, M. S. (1997) Dimensions of interjurisdictional cooperation, Journal of the American Planning Association, 63(2), pp. 205–219. doi:10.1080/01944369708975915

- Ohio Environmental Protection Agency (Ohio EPA) (2017)Ohio EPA issues water quality certification for NEXUS pipeline: Requires additional ‘contingency and storm water planning’ from NEXUS [Press Release]. Available at www.epa.ohio.gov/News/OnlineNewsRoom/NewsReleases/TabId/6596/ArticleId/1210/language/en-US/tag/401-certification/ohio-epa-issues-water-quality-certification-for-nexus-pipeline.aspx (accessed 20 September 2017)

- Ohio Environmental Protection Agency (Ohio EPA) (2018) Director’s final findings and orders NEXUS gas transmission, LLC (issued on 28 December 2018).

- Osland, A. C. (2013) Using land-use planning tools to mitigate hazards: Hazardous liquid and natural Gas transmission pipelines, Journal of Planning Education and Research, 33(2), pp. 141–159. doi:10.1177/0739456X12472372

- Osland, A. C. (2015) Building hazard resilience through collaboration: The role of technical partnerships in areas with hazardous liquid and natural gas transmission pipelines, Environment and Planning A, 47(5), pp. 1063–1080. doi:10.1177/0308518X15592307

- Pipelines and Informed Planning Alliance (November 2010) U.S. Department of Transportation, Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration, Office of Pipeline Safety. Partnering to Further Enhance Pipeline Safety in Communities Through Risk-Informed Land Use Planning. Final Report of Recommended Practices. Available at https://primis.phmsa.dot.gov/comm/publications/PIPA/PIPA-Report-Final-20101117.pdf

- Retzlaff, R. C. (2009) The use of LEED in planning and development: An exploratory analysis, Journal of Planning Education and Research, 29(1), pp. 67–77. doi:10.1177/0739456X09340578

- Rudder, C. (2008) Private governance as public policy: A paradigmatic shift, The Journal of Politics, 70(4), pp. 899–913. doi:10.1017/S002238160808095X

- Rudder, C. E., Fritschler, A. L., & Choi, Y. J. (2016) Public Policymaking by Private Organizations: Challenges to Democratic Governance (Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press).

- Scott, R. P., & Scott, T. A. (2019) Investing in collaboration for safety: Assessing grants to states for oil and gas distribution pipeline safety program enhancement, Energy Policy, 124, pp. 332–345. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2018.10.007

- Smith, G., & Birkland, T. (2012) Building a theory of recovery: Institutional dimensions, International Journal of Mass Emergencies and Disasters, 30(2), pp. 147–170.

- Späth, L., & Scolobig, A. (2017) Stakeholder empowerment through participatory planning practices: The case of electricity transmission lines in France and Norway, Energy Research & Social Science, 23, pp. 189–198 doi:10.1016/j.erss.2016.10.002

- State ex rel. Morrison v. Beck Energy Corp. (2015) 143 Ohio St.3d 271, 2015-Ohio-485.

- State ex rel. Walker v. Husted. (2015) 144 Ohio St.3d 361, 2015-Ohio-3749.

- U.S. Department of Transportation (15 March 2018) PHMSA’s mission. Available at https://www.phmsa.dot.gov/about-phmsa/phmsas-mission (accessed 19 January 2019).

- Warner, B., & Shapiro, J. (2013) Fractured, fragmented federalism: A study in fracking regulatory policy, Publius: The Journal of Federalism, 43(3), pp. 474–496. doi:10.1093/publius/pjt014