?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Reflecting on stressors from a detached perspective – a strategy known as distancing – can facilitate emotional recovery. Researchers have theorised that distancing works by enabling reappraisals of negative events, yet few studies have investigated specifically how distancing impacts stressor appraisals. In this experiment, we investigated how participants’ (N = 355) emotional experience and appraisals of an interpersonal conflict differed depending on whether they wrote event-reflections from a linguistically immersed (first-person) or distanced (second/third-person) perspective. Partly replicating previous findings, distanced reflection predicted increases in positive affect, but not reductions in negative affect, relative to immersed reflection. Linguistic distancing also predicted increases in motivational congruence appraisals (i.e. perceived advantageousness of the event), but did not influence other appraisal dimensions. We discuss how linguistic distancing may facilitate emotional recovery by illuminating the benefits of stressful experiences, enabling people to “see the good in the bad”.

Reflecting on unpleasant events can be adaptive, or it can spiral into rumination and exacerbate distress. Adopting a detached perspective – a strategy known as distancing – can help prevent the downward spiral into rumination and promote emotional recovery by enabling cognitive change (Kross et al., Citation2014). Distancing is thought to facilitate changes in how distressing events are appraised – a key driver of emotional experience (Moors et al., Citation2013). Yet, few studies have linked distancing with appraisal change, and even fewer have examined which specific appraisals are impacted by distancing. We addressed these gaps in the current study by exploring the emotional benefits of distancing through the lens of appraisal theory. Specifically, we report the results of an experiment investigating how distanced reflection on an interpersonal stressor impacts the key appraisal dimensions identified by Smith and Lazarus (Citation1993), as well as people’s affective experiences in response to the stressor. This approach represents an important step towards understanding the mechanisms driving the proposed emotional benefits of distancing.

Distancing involves “stepping back” and adopting a detached observer’s perspective on mental experience (Kross & Ayduk, Citation2009). Like other forms of decentring, distancing helps individuals to de-identify from thoughts and feelings, and to perceive conscious experience as fleeting and subjective (Bernstein et al., Citation2015). For instance, imagining events from a physically distant perspective (e.g. a bird’s eye view) – known as visual distancing – reduces negative affect (NA) and rumination (Kross & Ayduk, Citation2009), and increases positive affect (PA) following reflections on negative autobiographical events (Ranney et al., Citation2016). A related strategy – known as linguistic distancing – involves using second-person (“you”) or third-person (e.g. “she”), rather than first-person (e.g. “I”), pronouns to describe experiences. Linguistic distancing is a more common and effortless distancing strategy (Orvell et al., Citation2019) that has also been shown to reduce NA and increase PA in response to stressors in the lab (e.g. Kross et al., Citation2014) and in daily life (e.g. Orvell et al., Citation2020; Ranney et al., Citation2016).

Researchers have theorised that distancing facilitates emotional recovery by promoting cognitive change, specifically by changing how events are appraised (e.g. Kross et al., Citation2014). Supporting this view, Kross et al. (Citation2014) showed that linguistic distancing promoted greater challenge, as opposed to threat, appraisals of an anxiety-inducing event. Similarly, an earlier meta-analysis revealed that visual distancing increased the tendency to appraise events in ways that promote insight (Kross & Ayduk, Citation2009). Finally, linguistic distancing has been found to reduce the perceived importance of negative events (Gu & Tse, Citation2016).

Although there is preliminary evidence supporting the theorised effects of distancing on cognitive appraisal change, a comprehensive test of this hypothesis on multiple appraisal dimensions is lacking. Thus, it remains unclear whether these isolated effects of distancing on specific appraisals are unique or rather represent broader patterns of change across multiple dimensions identified in appraisal theories. Understanding how distancing impacts the appraisal process more broadly will help to identify the circumstances under which distancing might be more or less effective in engendering emotional recovery.

In the current study, we sought to understand how distancing impacts emotional responding to an interpersonal stressor, through the lens of appraisal theory. In particular, we examined how distancing influences the appraisal dimensions proposed by Smith and Lazarus (Citation1993) and common to most appraisal theories (Moors et al., Citation2013): motivational relevance (i.e. importance), motivational congruence (i.e. advantageousness), problem- and emotion-focused coping potential (i.e. perceived ability to cope with events and consequent emotions); self- and other-accountability (i.e. attributions of responsibility); and future expectancy (i.e. expected likelihood of desirable outcomes). Taking this comprehensive, multi-dimensional approach to assessing appraisals allowed us to distinguish different kinds of re-appraisal (i.e. appraisal change) that may be facilitated by distancing. For instance, distanced reflection on an interpersonal conflict could engender reconstrual of the event (e.g. perceiving the conflict as less important than it initially seemed), or allow a person to focus on different goals when evaluating the event (e.g. seeing the conflict as a learning experience could increase its perceived advantageousness). Both forms of reappraisal may promote emotional recovery, but via different mechanisms (Uusberg et al., Citation2019).

Consistent with previous research, we expected linguistic distancing to result in greater reductions in NA and increases in PAFootnote1 relative to immersed reflection. We further hypothesised that, relative to immersed reflection, writing about the interpersonal conflict from a linguistically distanced perspective would promote a profile of appraisals consistent with greater emotional recovery. Specifically, we predicted that distancing would increase appraisals along dimensions that have previously been linked with reduced negative emotion and/or increased pleasant affect, namely motivational congruence, emotion- and problem-focused coping, other-accountability, and future expectancy (Brans & Verduyn, Citation2014; Kuppens et al., Citation2012). Additionally, since previous research has linked greater motivational relevance (i.e. importance) appraisals with more intense and long-lasting negative emotions (Brans & Verduyn, Citation2014), we hypothesised that distancing would reduce motivational relevance appraisals. Finally, although previous research has not directly linked self-accountability appraisals with affective experience, we reasoned that in the context of interpersonal conflict greater self-accountability should be related to increased guilt (Smith & Lazarus, Citation1993) and possibly other negative emotions. Thus, we predicted distanced reflection would lead people to perceive themselves as less blameworthy (i.e. lower self-accountability appraisals).

Method

This study was pre-registered (https://aspredicted.org/wx86g.pdf) and approved by the University of Melbourne Human Research Ethics Committee. Raw data, code (pre-processing, analyses) and supplemental materials are available at https://osf.io/7amsv/.

Participants

An a priori power analysis indicated that we required a sample size of N = 376 to have 90% power (with α = .01) to detect a medium sized (d = 0.40) between-group difference, similar to the effect of distancing on NA reported by Kross et al. (Citation2005). To account for attrition and data loss, we aimed to recruit 400 participants.

We recruited 402 participants from Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (MTurk). We restricted our sample to US citizens aged over 18 who were fluent in English because Mturk workers are predominantly based in the US (Difallah et al., Citation2018), and to ensure that participants had sufficient English proficiency to complete the study (which had a language-based manipulation). We excluded participants who (a) did not complete our experimental manipulation (i.e. the reflective writing task; n = 24); (b) wrote text that indicated careless responding (n = 10); (c) completed the study faster than the minimum completion time in our pilot studyFootnote2 (i.e.<10-min; n = 8), or so slowly as to suggest inattention (i.e. >2.5 hFootnote3; n = 3); or (d) due to a combination of these reasons (n = 2). The experiment also included instructional attention checks; however we decided not to exclude participants based on their attention check performance because completion time and essay responses are better data quality indicators (Kennedy et al., Citation2020).Footnote4

Our final sample comprised 355 participants (55.2% men; 73.8% Caucasian) aged 18–71 years (M = 34.79, SD = 10.14; full demographics in Supplementary Tables S1–S3). Although this sample size falls slightly below our target, it is still sufficient to have 85% power of detecting our target effect-size. Participants took 10.53-139.90 min (M = 31.66; SD = 18.85) to complete the study and were paid US$7.50.

Materials and procedure

The experiment, completed via Qualtrics, comprised baseline (T0), recall (T1) and manipulation (T2) phases (see Supplementary Figure S1).

Baseline phase (T0)

Participants completed several global self-report scales, including measures of habitual reappraisal and rumination (see Supplemental Materials for measures) before rating their momentary affect.

Momentary affect

Like Kross et al. (Citation2005), we used 21-items from the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule-Extended Form (Watson & Clark, Citation1994). Participants rated to what extent they were “experiencing each feeling right now” for 15 negative feelings (e.g. sad, angry) and 6 positive feelings (e.g. happy, calm), from 1 (not at all) to 6 (extremely). We averaged ratings on negative and positive items to create NA (α = .96) and PA scales (α = .91), respectively. We selected these 21 items from seven emotions subscales that were most relevant to the context of interpersonal conflict and common to previous distancing studies (e.g. Kross et al., Citation2005, Citation2014; Ranney et al., Citation2016), namely anger (a.k.a., “hostility”), sadness, fear, anxiety, guilt, happiness (a.k.a., “joviality”), and serenity. We included three items per subscale to assess affective experiences reliably and comprehensively, while minimising participant burden. Separate analyses for these seven subscales are presented in the supplemental materials.

Recall phase (T1)

Like Kross et al. (Citation2005), we prompted participants to recall a relatively recent and unresolved interpersonal conflict involving a romantic partner, close friend, or family member, which had caused them to feel “angry, upset, or disappointed”. We gave participants as much time as needed to retrieve an appropriate memory before proceeding. They were then instructed to mentally reflect on this event for at least 60 s (full instructions in supplemental materials).

Next, participants again rated their momentary NA (α = .91) and PA (α = .93) while thinking about the conflict event.

Event appraisals

Next, participants rated to what extent the conflict event was important (motivational relevance); (dis)advantageous (motivational congruence); their responsibility (self-accountability); someone else’s responsibility (other-accountability); something they could change (problem-focused coping potential); something they could emotionally cope with (emotion-focused coping potential); and to what extent the event had turned out as they wanted (future expectancy). These appraisal items – adapted from Brans and Verduyn (Citation2014) and Kuppens et al. (Citation2012) – were rated from 1 (not at all) to 6 (very much), except motivational congruence which was rated from 1(very disadvantageous) to 6(very advantageous).

Finally, participants reported how resolved the event was (resolution status), how much time had elapsed since the event (memory age), and to what extent they had adopted a first- vs. third-person visual perspective when reflecting on the event (spontaneous visual distancing). See supplemental materials for full descriptions of these measures.

Manipulation phase (T2)

Next, we randomly allocated participants to a linguistically distanced (n = 181) or immersed (n = 174) condition, where they completed a reflective writing task about the interpersonal conflict event from their assigned perspective.

Linguistic distancing manipulation

Consistent with Kross et al. (Citation2014), we instructed participants to “write about the stream of thoughts that flow[ed] through [their] mind as [they] reflect[ed] on this interpersonal conflict”. Participants in the distanced condition were told to complete this task using “the pronouns ‘you’, ‘he/she/they’ and ‘[your name]’ as much as possible”. By contrast, participants in the immersed condition were told to complete this task using “the pronouns ‘I’ and ‘my’ as much as possible”. Full instructions appear in supplemental materials. To increase task engagement, participants had to write at least 480 characters (approx. 80 words) before proceeding.

Finally, participants rated their NA (α = .93), PA (α = .93), event appraisals, resolution status, and spontaneous visual distancing using the items described above.

Data analyses

Data were cleaned and analysed using R (Version 4.1.2).

To check the success of our linguistic distancing manipulation, we used Linguistic Inquiry Word Count (Pennebaker et al., Citation2007) to calculate the percentage of first-person pronouns in participants' written reflections.Footnote5 We compared the percentage of first-person pronouns used by participants in the distanced vs. immersed conditions using a Wilcoxon rank-sum test (conducted with the stats R-package).

For all other analyses, we ran 2 × 2 mixed ANOVAs using the afex (Singmann et al., Citation2016) and lsmeans (Lenth, Citation2016) packages, with Condition (distanced vs. immersed) as a between-subjects factor and Time (baseline [T0] vs. recall [T1]; or recall [T1] vs. manipulation [T2]) as a within-subjects factor. We ran follow-up t-tests, which were not pre-registered. However, as our ANOVAs were pre-registered, no corrections were applied for multiple comparisons.

Results

Manipulation checks

Affect induction

Mixed ANOVAs testing for change in affect from baseline to recall revealed significant main effects of Time for NA [F(1, 352) = 344.55, p < .001, = .50] and PA [F(1, 353) = 417.54, p < .001,

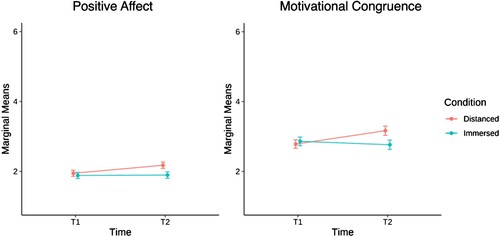

= .54], indicating successful affect induction: participants reported greater NA and lower PA after recalling the interpersonal conflict than at baseline (see ). Neither the main effects of Condition (ps ≥ .39), nor the Condition × Time interactions (ps ≥ .14) were significant, indicating successful randomisation.

Table 1. The means and standard deviation of NA, PA and appraisals across baseline (T0), recall (T1) and manipulation (T2) phases.

Memory age

To estimate the recency of recalled events, we trimmed the sample by 10% (i.e. removed 5% of participants on each tail end of the distribution) to exclude outliers in memory age. Participants in this trimmed sample (n = 319) recalled an event that had occurred, on average, 93 days (SD = 110 days) prior to recall. This aligns with previous distancing studies, which instructed participants to recall events no older than 12 months (e.g. Gu & Tse, Citation2016).

Linguistic distancing manipulation

A Wilcoxon rank sum test revealed that immersed participants used a higher proportion of first-pronouns in the writing task than distanced participants (W = 1984, p < .001, median difference = 10.58, 95% CI [9.90, 11.32]). In addition, a mixed ANOVA indicated that distanced participants reported greater visual distancing after the manipulation than at recall, whereas immersed participants showed the opposite pattern (see Table S5). Therefore, our distancing manipulation was successful.

Main analyses

Affect

Mixed ANOVAs, testing whether changes in PA and NA from recall to manipulation differed by condition, showed significant main effects of Time for NA [F(1, 352) = 4.52, p = .03, = .01] and PA [F(1, 353) = 7.53, p = .006,

= .02]. Thus, on average, participants (across conditions) reported decreases in NA and increases in PA after writing about their interpersonal conflict event (see ). The main effect of Condition was not significant for either NA or PA (ps ≥ .13,

= .006).

Partially supporting our hypothesis, the main effect of Time was qualified by a significant ConditionTime interaction for PA [F(1, 353) = 6.17, p = 0.01,

= .02], but not for NA [F(1, 352) = 0.10, p = .76,

< .001]. To aid interpretation, we plotted simple slopes of time predicting PA for each condition (see , left panel). Follow-up t-tests revealed that PA significantly increased following the manipulation among distanced participants, t(180) = 3.29, p = .001, MΔ = 0.23, 95% CI [0.09, 0.37], but not immersed participants, t(173) = 0.12, p = .83, MΔ = –0.01, 95% CI [–0.11, 0.09].

Appraisals

We next ran mixed ANOVAs testing whether changes in event appraisals from recall to manipulation differed by condition. These analyses revealed significant main effects of Time for self-responsibility [F(1, 352) = 10.79, p = 0.001, = .03] and problem-focused coping appraisals [F(1, 352) = 6.24, p = 0.01,

= .02]. Thus, across both experimental conditions, participants appraised their interpersonal conflict as easier to cope with but also more their own responsibility (see ) after writing about it. The main effect of Condition was not significant for any of the appraisals (ps > .09).

Partially supporting our hypothesis, we found a significant Condition × Time interaction for motivational congruence [F(1, 352) = 9.08, p = .003, = 0.03]. We probed this interaction by plotting simple effects (see , right panel) and running follow-up t-tests, which revealed that motivational congruence increased from recall to manipulation among distanced participants, t(179) = 3.30, p = .001, MΔ = 0.38, 95% CI [0.15, 0.61], but not among immersed participants, t(173) = 0.89, p = .37, MΔ = 0.10, 95% CI [−.12, .31].

Supplemental results

We report results of several additional analyses, as well as full output from our main analyses, in the supplemental materials (see https://osf.io/7amsv/). The full ANOVA output for our manipulation checks and main analyses (including analyses of individual emotion subscales) can be found in Tables S5–S6 and Tables S7–S9, respectively. Our main findings remained robust when we ran non-parametric versions of our ANOVAs to account for non-normally distributed outcomes (see Tables S10–S12) and when we excluded participants who took <2.5 h, who failed at least one attention check, and whose essays failed our quality check (see Tables S13–S15). Importantly, ANOVAs on positive emotion subscales suggest that the observed effects of linguistic distancing on PA were driven by increased feelings of serenity, as indicated by a significant Condition × Time interaction, p = .01, = .02: specifically, serenity increased following the manipulation among distanced participants, t(180) = 3.96, p < .001, MΔ = 0.36, 95% CI [.18, .54], but not immersed participants, t(176) = 0.58, p = .56, MΔ = 0.04, 95% CI [–.19, .10]. In contrast, there was no significant Condition × Time interaction for happiness, p = .12,

= .01.

Finally, we explored whether changes in appraisals from recall to manipulation were associated with corresponding changes in affect, by estimating Pearson correlations (reported in Table S16), and whether such associations differed by Condition, using regression analyses (reported in Table S17). We found that greater NA reductions correlated with greater increases in emotion-focused coping potential and future expectancy appraisals (p ≤ .006). Greater PA increases correlated with greater increases in emotion-focused coping potential and motivational congruence appraisals (p ≤ .02).

Discussion

Reflecting on stressful experiences from a distanced perspective has been theorised to promote emotional recovery by facilitating reappraisal. We report a novel and comprehensive test of this hypothesis by investigating how linguistic distancing influences changes across several key appraisal dimensions common to many appraisal theories. Our aims were twofold.

First, we sought to replicate prior findings regarding the affective benefits of distancing. We found that linguistic distancing predicted increases in PA when reflecting on an interpersonal conflict, relative to immersed reflection. Thus, our results build on previous research, which has documented that distancing reduces the intensity (Gu & Tse, Citation2016) and duration (Verduyn et al., Citation2012) of PA when reflecting on positive events, by showing that distancing can enhance PA in the context of negative events (see also Ranney et al., Citation2016).

Contrary to our hypothesis, we found no effect of linguistic distancing on NA. This finding is inconsistent with prior research examining the effects of linguistic distancing on negative emotions in response to lab-induced (e.g. Kross et al., Citation2014; Nook et al., Citation2019) and daily life (Gu & Tse, Citation2016) stressors. But this finding does align with Seih et al.’s (Citation2011) finding that a single session of distanced writing did not impact NA in response to a real-world stressor. Thus, linguistic distancing may require repeated practice to reliably reduce NA. More generally, research on expressive writing suggests that at least three sessions are required to achieve the deep reflection needed to yield health benefits (Reinhold et al., Citation2018).

The fact that distancing did not reduce NA may seem to reflect unsuccessful emotion regulation. But mixed emotion theories posit otherwise: the co-activation of PA and NA facilitates meaning-making for stressful events, by encouraging individuals to accept (vs. disregard) NA and turn adversity into a learning experience (Larsen et al., Citation2003). Indeed, the co-occurrence of PA and NA correlates with eudaemonic wellbeing, following attempts to process important life events (Berrios et al., Citation2017). Thus, while our findings suggest that distanced (vs. immersed) reflections do not promise greater NA reductions, the co-occurrence of PA and NA may reflect the catharsis of meaning-making processes.

Second, we sought to investigate how distancing influences cognitive appraisals. Partly consistent with our predictions, linguistic distancing facilitated increases in motivational congruence appraisals of an interpersonal conflict. This finding aligns with the mindfulness-to-meaning theory (Garland et al., Citation2015), which posits that decentring strategies (such as distancing) encourage egocentric detachment, thereby increasing flexibility in how stressful events are appraised, in turn facilitating positive reappraisals of adversity. Positive reappraisal is equivalent to updating motivational congruence appraisals: both involve identifying advantageous aspects of a stressor and thereby illuminate its consistency with existing beliefs or desires.

Contrary to our hypotheses, distancing did not induce changes in other appraisal dimensions, relative to immersed writing. We speculate that the relatively narrow profile of appraisal change we observed reflects the wide range of interpersonal conflicts described by participants and their resultant variations in reappraisal affordances (Uusberg et al., Citation2019). Distancing may only facilitate reappraisal insofar as the emotion-eliciting situation affords it. For instance, a situation where the outcome is difficult to reverse (e.g. divorce) may be particularly difficult to reappraise in terms of problem-focused coping potential. Future studies should consider studying how distancing influences appraisals of different classes of stressors that vary in “reappraisability”.

Limitations and future directions

To examine if emotions and appraisals are more amenable to change following distanced (vs immersed) reflection, we used a between/within-subjects design, which departs from the purely between-subjects design commonly adopted by previous distancing studies (e.g. Kross et al., Citation2014). By instructing participants to reflect on their event twice, the emotions and appraisals reported initially at recall may have crystallized their reactions to the event, preventing some hypothesised effects from emerging (e.g. of distancing on NA). Future studies could consider dropping pre-manipulation assessments to see if our findings are robust. However, note that we asked participants to write their reflections only once, namely at manipulation. Written reflections are likely to be more powerful in modifying and crystallizing people’s emotional reactions and appraisals, than purely mental reflections.

Our mixed between-within subject design may also have induced demand effects. By asking participants to complete the same affect and appraisal measures both before (T1) and after (T2) the distancing manipulation, we may have hinted to participants that our aim was to demonstrate the benefits of expressive writing in general, thus inducing participants across both conditions to respond consistently. This may explain the significant main effects of Time we observed for several outcomes. However, demand effects cannot explain the Condition × Time interactions, given that distancing was manipulated between subjects. Another possibility is that the main effects of Time were due to general cognitive and emotional benefits of expressive writing (e.g. Reinhold et al., Citation2018). However, since we did not include a no-writing or neutral-writing control, we cannot determine if our findings were due to expressive writing (as opposed to writing in general) or simply the passage of time. Likewise, without a control condition, we cannot rule out the possibility that Condition × Time interaction effects were (partly) driven by detrimental effects of immersed writing, which may trigger or prolong rumination and thereby impede emotional recovery, rather than exclusively due to beneficial effects of distanced writing.

Another limitation is that we recruited only US-based participants from MTurk. Researchers have questioned data quality from MTurk participants, who may not represent the general population (Kennedy et al., Citation2020). Although we took several steps to ensure quality data (e.g. closely inspecting written responses), this study should be replicated with community participants. Additionally, future research should investigate whether culture influences the effectiveness of distancing (e.g. Cohen et al., Citation2007). Furthermore, instead of using single-item appraisal measures, for which internal consistency cannot be established, future studies should consider multi-item measures of appraisals (see e.g. Uusberg et al., Citation2021).

Finally, future research should explore how distancing influences the dynamic interplay between appraisals and emotions over time. Uusberg et al. (Citation2019) theorised that one successful instance of reappraisal confers durable appraisal shifts. Through iterative practice, the cumulative effects of such reappraisals may explain the long-term emotional benefits of distancing, as reported in prior studies (e.g. Ranney et al., Citation2016). An experimental longitudinal design, involving multiple instances of distanced reflection on the same stressful event, may shed light on this question.

Conclusion

Our findings add to the distancing literature by demonstrating that linguistic distancing promotes emotional recovery and reappraisal by increasing PA and motivational congruence appraisals, suggesting that reflecting on stressors from a distanced perspective enables people to see the good in the bad.

DistancingAppraisals_SupplementalMaterials_V7.docx

Download MS Word (204.4 KB)Acknowledgement

We would like to acknowledge the assistance of Bruce McIntyre, Julia Schreiber, and Yaoxi Shi with design and data-collection of this experiment.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data and analysis code supporting the findings of this study are openly available on the Open Science Framework at https://osf.io/7amsv/.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Our pre-registered hypothesis focused on NA, but PA should also increase given prior research findings.

2 Pilot study information can be found in the supplemental materials.

3 When we exclude participants (n = 22) based on a more conservative cut-off of 60 min, the main findings do not change. Therefore, we retain these participants to maximize sample size.

4 The number of people who passed the essay quality criteria, completion time criteria and attention checks are broken down in Supplementary Table S4.

5 We only counted first-person pronouns, because we cannot distinguish whether a participant used third-person pronouns to address themselves (indicating linguistic distancing) vs. other people involved in the event.

References

- Bernstein, A., Hadash, Y., Lichtash, Y., Tanay, G., Shepherd, K., & Fresco, D. (2015). Decentering and related constructs. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 10(5), 599–617. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691615594577

- Berrios, R., Totterdell, P., & Kellett, S. (2017). When feeling mixed can be meaningful: The relation between mixed emotions and eudaimonic well-being. Journal of Happiness Studies, 19(3), 841–861. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-017-9849-y

- Brans, K., & Verduyn, P. (2014). Intensity and duration of negative emotions: Comparing the role of appraisals and regulation strategies. Plos ONE, 9(3), e92410. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0092410

- Cohen, D., Hoshino-Browne, E., & Leung, A. K. (2007). Culture and the structure of personal experience: Insider and outsider Phenomenologies of the self and social world. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 39, 1–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0065-2601(06)39001-6

- Difallah, D., Filatova, E., & Ipeirotis, P. (2018). Demographics and dynamics of mechanical Turk workers. Proceedings of the Eleventh ACM International Conference on Web Search and Data Mining (pp. 135–143). https://doi.org/10.1145/3159652.3159661

- Garland, E., Farb, N. A., Goldin, P., & Fredrickson, B. (2015). Mindfulness broadens awareness and builds eudaimonic meaning: A process model of mindful positive emotion regulation. Psychological Inquiry, 26(4), 293–314. https://doi.org/10.1080/1047840X.2015.1064294

- Gu, X., & Tse, C. (2016). Narrative perspective shift at retrieval: The psychological-distance-mediated-effect on emotional intensity of positive and negative autobiographical memory. Consciousness And Cognition, 45, 159–173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.concog.2016.09.001

- Kennedy, R., Clifford, S., Burleigh, T., Waggoner, P., Jewell, R., & Winter, N. (2020). The shape of and solutions to the MTurk quality crisis. Political Science Research and Methods, 8(4), 614–629. https://doi.org/10.1017/psrm.2020.6

- Kross, E., & Ayduk, Ö. (2009). Boundary conditions and buffering effects: Does depressive symptomology moderate the effectiveness of self-distancing for facilitating adaptive emotional analysis? Journal of Research in Personality, 43(5), 923–927. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2009.04.004

- Kross, E., Ayduk, O., & Mischel, W. (2005). When asking “Why” does not hurt distinguishing rumination from reflective processing of negative emotions. Psychological Science, 16(9), 709–715. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2005.01600.x

- Kross, E., Bruehlman-Senecal, E., Park, J., Burson, A., Dougherty, A., Shablack, H., Bremner, R., Moser, J., & Ayduk, O. (2014). Self-talk as a regulatory mechanism: How you do it matters. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 106(2), 304–324. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035173

- Kuppens, P., Champagne, D., & Tuerlinckx, F. (2012). The dynamic interplay between appraisal and core affect in daily life. Frontiers in Psychology, 3. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00380

- Larsen, J. T., Hemenover, S. H., Norris, C. J., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2003). Turning adversity to advantage: On the virtues of the coactivation of positive and negative emotions. In L. G. Aspinwall & U. M. Staudinger (Eds.), A psychology of human strengths: Fundamental questions and future directions for a positive psychology (pp. 211–225). American Psychological Association Press.

- Lenth, R. (2016). Least-squares means: The R package lsmeans. Journal of Statistical Software, 69(1). https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v069.i01

- Moors, A., Ellsworth, P. C., Scherer, K. R., & Frijda, N. H. (2013). Appraisal theories of emotion: State of the art and future development. Emotion Review, 5(2), 119–124. https://doi.org/10.1177/1754073912468165

- Nook, E., Vidal Bustamante, C., Cho, H., & Somerville, L. (2019). Use of linguistic distancing and cognitive reappraisal strategies during emotion regulation in children, adolescents, and young adults. Emotion, 20, 525–540.https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000570

- Orvell, A., Ayduk, Ö., Moser, J., Gelman, S., & Kross, E. (2019). Linguistic shifts: A relatively effortless route to emotion regulation? Current Directions in Psychological Science, 28(6), 567–573, https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721419861411

- Orvell, A., Vickers, B., Drake, B., Verduyn, P., Ayduk, O., Moser, J., Jonides, J., & Kross, E. (2020). Does distanced self-talk facilitate emotion regulation across a range of emotionally intense experiences? Clinical Psychological Science, 9(1), 68–78. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167702620951539

- Pennebaker, J. W., Booth, R. J., & Francis, M. E. (2007). Linguistic inquiry and word count [computer software]. LIWC Inc.

- Ranney, R., Bruehlman-Senecal, E., & Ayduk, O. (2016). Comparing the effects of three online cognitive reappraisal trainings on well-being. Journal of Happiness Studies, 18(5), 1319–1338. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-016-9779-0

- Reinhold, M., Bürkner, P., & Holling, H. (2018). Effects of expressive writing on depressive symptoms-A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 25(1), e12224. https://doi.org/10.1111/cpsp.12224

- Seih, Y., Chung, C., & Pennebaker, J. (2011). Experimental manipulations of perspective taking and perspective switching in expressive writing. Cognition & Emotion, 25(5), 926–938. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2010.512123

- Singmann, H., Bolker, B., Westfall, J., & Aust, F. (2016). afex: Analysis of Factorial Experiments. R package version 0.16-1. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=afex

- Smith, C. A., & Lazarus, R. S.. (1993). Appraisal components, core relational themes, and the emotions. Cognition & Emotion, 7(3-4), 233–269. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02699939308409189

- Uusberg, A., Taxer, J. L., Yih, J., Uusberg, H., & Gross, J. J. (2019). Reappraising reappraisal. Emotion Review, 11(4), 267–282. https://doi.org/10.1177/1754073919862617

- Uusberg, A., Yih, J., Taxer, J. L., Christ, N. M., Toms, T., Uusberg, H., & Gross, J. (2021). Appraisal Shifts during Reappraisal. https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/ar4kj

- Verduyn, P., Van Mechelen, I., Kross, E., Chezzi, C., & Van Bever, F. (2012). The relationship between self-distancing and the duration of negative and positive emotional experiences in daily life. Emotion, 12(6), 1248–1263. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028289

- Watson, D., & Clark, L. A. (1994). The PANAS-X: Manual for the positive and negative affect schedule-expanded form.