Abstract

Aims: To investigate the feasibility and acceptability of a serious mobile-game intervention on older adults’ engagement, affect, and cognitive function. Methods: In this single-subject design, twenty older adults, six of whom living with dementia, participated in a 16-session mobile-game intervention. Before and after the intervention, participants had sessions involving traditional paper-based cognitive activities. Engagement and affect were measured in each session. Cognitive measures were administered before and after the intervention. Acceptability was explored through interviews. Results: After the intervention, there was a statistically significant increase in engagement in 37% of participants, and in affect in 21% of participants. Participants preferred the mobile games to the paper-based activities. Cognitive measures showed improvement in four participants with dementia. Conclusions: Although not conclusive, participants experienced higher levels of engagement and positive affect while playing the mobile games compared to paper-based activities. The results indicate feasibility and acceptability of the mobile game intervention.

Keywords:

Introduction

In 2015, nearly 47 million people were living with dementia, and this number is projected to triple by 2050. Dementia and the cognitive impairment that precedes it impact not only those individuals with this condition who gradually lose their independence due to cognitive decline, but also their relatives who experience an increase in their loved ones’ care-related demands. Citation1 Engagement in cognitively stimulating activities can help prevent cognitive decline in healthy older adults. Evidence from longitudinal studies with cognitively intact older adults suggests that cognitive reserve is a dynamic property that can change as a result of cognitive interventions. Citation1 However, in older adults with cognitive impairments or dementia, the evidence of the effect of cognitive training and stimulating interventions on cognitive improvements is inconclusive. Citation2–4 This may be because cognitive impairments prevent older adults from engaging in traditional cognitively stimulating activities (e.g., paper-based word search games). Citation5 A lack or low level of engagement prevents people with cognitive impairments from benefiting from the therapeutic effects of these activities. Citation6

Engagement is a psychological state that has cognitive, emotional, and behavioral dimensions. Citation7 The cognitive dimension is related to high levels of attention and concentration that allow an individual to be immersed in a task. The emotional dimension pertains to positive emotions associated with perceiving an activity as enjoyable. Citation8 The behavioral component is related to the observed manifestations of participation, such as the motor behaviors needed to interact with an activity (e.g., looking at the activity, manipulating materials). The foremost theoretical foundation of engagement is the Flow Theory. Citation9 According to the Flow Theory, when an individual is totally engaged or involved in an activity they experience a flow state which is described as “a subjective state that people report when they are completely involved in something to the point of forgetting time, fatigue, and everything else but the activity itself”. Citation9(p230) The characteristics of being in a flow state include a balance between a task’s challenges and the individual’s skills, awareness of action, clear task goals, immediate feedback, concentration on the task, a sense of control, loss of self-consciousness, and transformation of the perception of time. Citation9

The use of serious games as a low-cost, low-risk, enjoyable, and effective alternative to cognitive interventions is an emerging field receiving increasing attention from researchers and practitioners. Also, older adults perceive playing games as a meaningful activity. Citation10 Serious games, including table-top, board, paper-based and digital, are designed for purposes other than entertainment (e.g., improving memory or attention). Citation11 When digital games are implemented in mobile devices, such as tablets and smartphones, they are called serious mobile games (hereafter referred to as mobile games). Four technical features of digital serious games may make them superior in engaging older adults in cognitive training and stimulation activities than traditional table-top, board, or paper-based games. First, a task’s challenge can be easily adjusted according to an individual’s skills; as a result, the individual is more likely to feel skillful and successful, and less frustrated, anxious, or bored. Second, digital serious games provide clear task goals, so the individual knows what is expected from him. Third, digital games provide unambiguous and immediate feedback, showing the individual adjustments needed to accomplish the goal. Citation12 Fourth, digital games can be played on an individual basis, thus allowing individuals with cognitive impairment or dementia to practice cognitive exercises in an enjoyable and independent way, which contributes to self-confidence and self-efficacy. Citation13 Despite these potential advantages, factors such as familiarity with technology may affect the play experience of older adults with digital games and, in turn, the acceptance of interventions using these technologies. Further, the 2014 World Alzheimer Report reported that cognitively stimulating activities, including serious games, may be beneficial in terms of improving or maintaining cognitive functioning in older adults with cognitive decline; however, most of these activities have not been investigated in clinical trials Citation14 and whether paper-based or digital games are more engaging for older adults remains an unanswered question.

The literature suggests that digital games have a positive impact on some cognitive functions (e.g., memory, cognitive flexibility) in cognitively healthy older adults. Citation15–18 Recent systematic literature reviews have synthesized evidence from published studies that investigated the effects of serious digital games on the cognitive skills of older adults with mild cognitive impairment or dementia. Some interventions using these technologies have a small effect on memory, speed of processing, attention, executive function, visuospatial skills, and overall cognition. Citation19,Citation20 However, evidence of these technologies on preventing or reversing dementia in older adults is inconclusive Citation14. Further, the effects of digital games on cognitive functioning depend on the technical features of the games used and the cognitive skills being trained.

Our team at the University of Alberta has developed a collection of four serious (Android) web-based mobile games (entitled Vibrant Minds - http://vibrant-minds.org) that share a common back end. These games were developed for the assessment and intervention of cognitive functions in older adults with and without dementia or cognitive impairments. We believe that cognitive activities using mobile games designed for older adults with dementia may increase their levels of engagement and positive affect, which in turn can facilitate improvement in their cognitive functioning. This study investigates the following research questions.

Do engagement and affect improve among cognitively healthy older adults and among those with mild to moderate dementia while they are playing mobile games compared to paper-based cognitive activities?

Are there changes in the cognitive functions of those that are cognitively healthy and those with mild to moderate dementia after playing these mobile games?

Materials and methods

Study design

This was a single-subject multiple baseline design with three phases: baseline, intervention, and withdrawal (A1BA2). This study also used a multimethod approach. It had a quantitative component (outcome measures) and a qualitative component (interviews), which we utilized for the social validation of the intervention in terms of its effects on cognitive functions and acceptance of the intervention. We believe that a single-subject research design was suitable for informing future research, as it allowed us to compare the outcome variables between the phases with a small sample size, while at the same time providing insights into understanding the older adults’ experiences during the intervention. A single-subject design involves the manipulation of an independent variable and repeated measures. These varying levels of intervention are referred to as phases, where one phase serves as a baseline or comparison. Citation21 In this study, the independent variable was the type of cognitive activity the participants completed where the sessions involving mobile games constituted the intervention (phase B), and the sessions involving paper-based games constituted the control conditions (Phase A1 and A2). Dependent variables were measured several times and were compared between phases (between-phase examination) where each participant served as their own control. When single-subject studies incorporate replication, randomization, and multiple participants, they are designed to have external validity for the generalizability of the results. Citation21 This was the case for the present study.

Participants

We included the participants if they were adults aged 60 years or older, cognitively intact, or with a self-reported mild cognitive impairment or dementia, and who were able to attend the scheduled sessions. We excluded participants who did not understand and speak English, had moderate or severe limitations in the control or movement of their upper extremities, had severe visual, hearing, or cognitive impairments that prevented them from interacting with the research staff or mobile games. The study participants were recruited from the community. Those participants with dementia were recruited through a community organization that provides support for people with dementia and their families. This study was approved by the University of Alberta ethics board (Pro00069138). Written consent was obtained from participants or substitute decision makers. The participants received a coffee shop gift card (CAN$10-$25 value) after completing each phase.

Settings

The study was conducted at two locations, a supportive living facility, and a community organization providing support to persons with dementia and their families both located in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada.

Materials

Mobile games

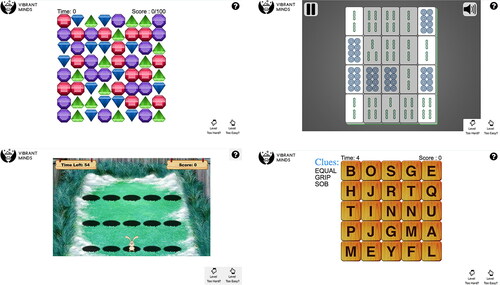

We used the “Vibrant Minds” mobile games including Whack-A-Mole (WAM), Word Search, Bejeweled, and Mahjong Solitaire (See ). These mobile games were co-designed with older adults who provided input regarding what themes and activities could be stimulating for this population. WAM is a game that older adults in North America were likely to have played at fairs when they were young; Mahjong Solitaire was proposed as a culturally appropriate game for the older adult community with Asian heritage living in the geographical area where the study was conducted; Word Search is a common paper-based game played by older adults for leisure; and Bejeweled is a popular mobile game among older adults. Our tablet version of the games involved few rules and used a simple interface, thus making them suitable to be played by older adults with dementia. The mobile games were designed in a way that as gameplay improved, each mobile game became progressively more difficult. Each game was designed to practice the specific mental functions of sustained attention, processing speed, regulation of the quality of motor production, and discrimination of visual information. In addition, WAM was designed to train selective attention and the regulation of the speed of motor production. Word Search and Mahjong Solitaire were designed to train short-term memory. These mobile games were played on 10-inch Android tablets provided by the research team. One participant (P14) used his personal iPad which accommodated his visual impairment. Stylus and supports (e.g., wedges) were provided as needed. In a pilot study, we found that older adults with dementia were able to play the four games and enjoyed the activities. Citation22

Paper-based cognitive activities

We used four sets of paper-based cognitive games (cancellation activities (e.g. start cancellation), word search, matching activities, and paper-based Mahjong), each with various levels of difficulty. To select the paper-based cognitive games, we carried out an activity analysis of the cognitive functions used during the four mobile games, and during the paper-based cognitive activities and games commonly used in cognitive training in rehabilitation settings using the methodology proposed in Thomas (2015).Citation23 In this method, the activity is divided into steps, and the required body functions, body structures, and performance skills are identified for each step. One of the researchers (ARR) used the activity analysis method to identify the required cognitive body functions to play each mobile game and paper-based activity. Each cognitive function was rated as “Greatly challenged,” “Minimally challenged,” or “Not challenged.” Those cognitive functions that were “Greatly challenged” in the mobile games were used to select the paper-based cognitive activities and the games to be used during the baseline and withdrawal phases. We selected paper-based games where the same cognitive functions were greatly challenged. This allowed us to ensure that the paper-based and mobile games were used to train the same cognitive functions.

Dependent variables and measures

The outcome variables of this study were engagement, affect, and cognitive function.

Engagement

Engagement was measured using a four-point Likert-style self-reported questionnaire that we developed for this study. Citation24 Through a literature review, we identified which methods were used to measure engagement while individuals were performing serious computer game tasks and found that there was no suitable questionnaire for use with older adults with dementia. Citation25 Thus, we created an eight-item questionnaire that reflected the main characteristics of engagement in flow-producing activities. Citation9 We selected those items already used in existing questionnaires of engagement or flow-state and adapted them so that every item was short, thus allowing older adults with mild or moderate dementia to understand them (i.e., “I felt successful”, “I felt skillful”, “I forgot everything around me”, “I felt like time passed quickly”, “I felt completely absorbed”, “I felt good”, “I felt I had control over the task”, “I felt that I could deal with the task”). Citation26

Affect

Affect was conceptualized as a basic sense of feeling that is organized in few fundamental bipolar dimensions, including degrees of pleasantness, intensity, and motivation. Citation8 Affect was measured using the positive affect negative affect schedule (PANAS), which is composed of two subscales, positive affect (PA) and negative affect (NA). The PA subscale has ten items (e.g., Interested, Excited, and Active), and the NA subscale also has ten items (e.g., Distressed, Upset, and Ashamed). Each item is rated on a five-point Likert-style scale (1 = not at all, 5 = extremely), where an individual indicates to what extent they feel at a particular moment. The sum of the ratings of each subscale indicates an individual’s level of positive and negative affect. Citation27 The PANAS has good construct-related validity, criterion validity, and external validity for both the PA and NA subscales when used with older adults. Citation28 It also has high internal consistency when used with this population, Citation28,Citation29 and very good test-retest reliability. Citation30

Cognitive functions

These were measured using the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) and the Trails Making Test (TMT). The MoCA is a 30-item screening test that is used to detect cognitive impairments. It assesses several cognitive domains including visuospatial skills, executive functioning, visuoperception, naming, memory, attention, language, abstraction, and orientation. Citation31 The MoCA has strong concurrent and criterion validity even in older adults with mild cognitive impairment who have a low level of education and varying literacy, Citation31–33 has adequate convergent validity, Citation32 good test-retest reliability, internal consistency, Citation33 and inter-rater reliability, Citation34 and it is a responsive tool. Citation35

The TMT is a timed paper and pencil task where an individual connects numbers in ascending order (TMT-A) and alternating numbers and letters in ascending numerical and alphabetical order (TMT-B). Citation36 This instrument is used to screen for the cognitive abilities of executive functioning, divided attention, visuospatial skills, sequencing, processing speed, cognitive flexibility, and working memory for older adults with and without mild cognitive impairments or dementia. Citation37,Citation38 The TMT has high inter-rater reliability and is a responsive tool. Citation39,Citation40

Procedure

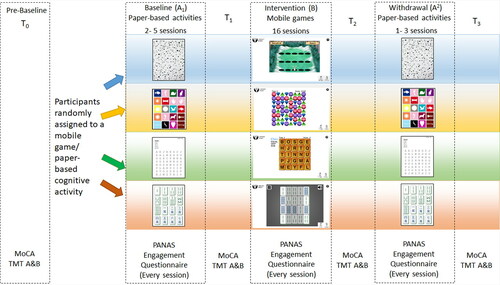

presents an overview of the study design and procedure. After the consent and assent were obtained, each participant had an initial meeting where the MoCA and TMT A&B were administered for the first time (Pre-Baseline T0). Then, each participant was randomly assigned to one of the four mobile games and matching paper-based cognitive games. In single-subject design studies, the primary outcome (dependent variables) measurements are recorded repeatedly for every participant between times and phases (independent variables). Citation21 In this study, the Engagement questionnaire and the PANAS were the primary outcome variables; thus, right after each participant had finished each session, they filled out the Engagement questionnaire and PANAS.

Figure 2. Overview of study design and procedure.

MoCA = Montreal Cognitive Assessment. TMT A&B = Trails Making Test part A and B. T0 = Assessment at pre-baseline. T1 = Assessment right after baseline phase ends. T2 = Assessment right after intervention phase ends. T3 = Assessment right after withdrawal phase ends. PANAS = Positive affect negative affect schedule.

During the Baseline phase (A1), the participants received traditional paper-based cognitive games. The length of the baseline varied between the participants, as it depended on the stability of the data. Citation41 We planned to have a minimum of three data points at the baseline phase, and ideally between four and five data points; however, some of the participants became noticeably anxious to start the intervention, so we decided to start the mobile game intervention phase earlier with them. The MoCA and TMT A&B were administered for the second time (T1) at the end of the Baseline phase. The Intervention phase (B) started with one fifteen-minute training session on how to use the Vibrant Minds mobile games. Each mobile game also contained a short demonstration video showing step-by-step instructions. The intervention consisted in sixteen sessions with one of the four mobile games over a period of eight weeks. The MoCA and TMT A&B were administered for the third time (T2) at the end of the Intervention phase. The Withdrawal phase (A2) phase comprised the same characteristics as the Baseline phase. The MoCA and TMT A&B were administered for the fourth time (T3) at the end of the Withdrawal phase.

Each session during every phase (Baseline, Intervention, Withdrawal) was conducted in a room where the participants were seated at a table to do either the paper-based or mobile game activities, depending on which phase each participant was at for any given moment. Before starting each session, we asked the participants about their current mood and any exceptional events. The sessions were conducted twice per week and scheduled on the same days of the week and at the same time whenever possible. The participants performed the activities individually, but in the same room. Two to five research assistants were present during each session to set up the room, materials, and equipment, provided instructions, and helped the participants as necessary during the activities and when filling out the Engagement questionnaire and PANAS. Each activity lasted 30 minutes and the same verbal instructions were given to the participants at each session: “We prepared these activities for you. We want you to do these for 30 minutes.”

Procedural fidelity

A detailed protocol guided the setup of every session (Baseline, Intervention, and Withdrawal) and a checklist was used to ensure adherence to the protocol. Procedural fidelity was achieved through strict adherence to the protocol during every session while considering Gresham’s verbal, physical, temporal, and spatial parameters. Citation42 The research assistants checked the protocol before, during, and after each session, and noted any event that happened during the session; for example, a noisy environment, a cellphone rang, somebody interrupted the session, or a technical issue with the games. Once all data had been collected, a research assistant who did not participate in the data collection assessed the procedural fidelity from the checklists for 100% of the sessions. There were 22 protocol parameters that needed to be met per participant per session. Procedural fidelity was assessed by calculating the percentage of the times that the protocol parameters were met in every session and by every participant over the total of the parameters in the whole study (i.e., number of parameters per participant per session (n = 22) * total number of sessions all participants (n = 422) = 9,284 parameters to be met). The total percentage of the protocol adherence was 90% (8,356 parameters met).

Data analysis

We used descriptive statistics to summarize participant demographics. The engagement score was calculated by adding up the score of each item, resulting in a total value between 8 and 32 where higher values indicated higher levels of engagement. For the PANAS score, some of the participants had high scores in both PA and NA. Since we were interested in the effect of playing the games on affect, and considering that the PA and NA scales are represented as orthogonal dimensions, Citation27 we combined both PA and NA for our outcome variable as used by Subramaniam and colleagues. Citation43 That is, the sum of the values of the NA subscale was subtracted from the sum of the values of the PA subscale (PA-NA), resulting in a number between −50 and 50 as a measure of affect. Positive values meant that there was more of a positive affect than a negative affect.

We followed the guidelines for single-case research to assess the data. Citation41 We assessed the baseline stability of the primary outcome variable (PA - NA) using an X-moving range chart when there were three or more data points. Citation44 We assessed the data autocorrelation by running a lag-1 autocorrelation for the series of data at the baseline and intervention. The autocorrelation was corrected using the first difference transformation procedure. Citation45 The levels, latency, and trends were assessed through a visual analysis of each phase and compared between the adjacent phases. Citation41 The slopes for both the baseline and intervention were calculated using the celeration line for each phase. Citation45 We established the statistical significance of the change if at least two consecutive data points of the intervention phase and withdrawal phase fell outside the two standard deviation band (2 SD band method) calculated using the baseline data. Citation44 The evidence provided by the study was assessed according to the rules of evidence for a single-case design. Citation41 Strong evidence was established if at least 75% of the participants per mobile game demonstrated a significant change at the intervention along with no non-effects; there was moderate evidence when at least 75% of the participants per mobile game demonstrated a significant change at the intervention, with 25% demonstrating no significant change; and a non-effect meant that less than 75% of the participants per mobile game had demonstrated a significant change at the intervention on the dependent variable. We used Microsoft Excel 2013 for all statistical analyses.

The MoCA score was calculated according to the MoCA manual. Citation31 The TMT part B was subtracted from the TMT part A, as it minimizes visuoperceptual and working memory demands, thus providing a relatively pure indicator of executive functioning. Citation38

Social validation of the results was established through subjective evaluation through interviews used to explore the acceptability of the intervention by the participants. Citation46 At the end of the study, three senior members of the research team interviewed 19 participants about their experiences with the intervention. It was not possible to conduct the interview with participant P12 due to her low cognitive status resulting in her inability to understand and respond to the interview questions. The interviews were recorded and transcribed. The data were coded and analyzed using a conventional approach to content analysis. Citation47

Results

Participants’ description

There were originally 24 participants in the study. Three participants withdrew from the study, and one participant passed away during the study. A total of 20 older adults finished the study, six of them living with dementia (Alzheimer disease). Nine participants were from a supportive living facility. Five participants were older adult relatives of participating older adults with dementia. The demographic characteristics of the complete sample are presented in and the specific information for each participant is presented in . One of our participants (P12, woman, 85 years old) had a very low cognitive status, so the only outcome measure we administered was the MoCA at the pretest. However, P12 completed all of the study phases.

Table 1 Demographics.

Table 2. Individual participants’ information and values per phase per outcome variable.

Sixteen participants (80%) used computers, six used tablets (30%), and six used smartphones on a daily basis. Almost half (9/20, 45%) of the older adults played computer or mobile games on a daily basis, while four played games between twice per week and less than once per month. Most of the participants were right-handed (17/20, 85%).

Results of the outcome variables

Visual and statistical analyses were performed on a plot diagram per participant per outcome variable (These 38 plot diagrams are available on request). The values per phase per participant are presented in , and the summary per outcome variable per mobile game is presented in . Between four and six participants played each of the games; by chance, no participants with dementia were allocated to the Bejeweled game (See ).

Table 3. Results per outcome variable per game.

Engagement

The data showed no autocorrelation. Cronbach’s alpha for the eight items in the engagement questionnaire was 0.841, demonstrating good internal consistency. The visual analysis (see ) revealed that for the engagement questionnaire scores, the mean of the intervention (level) was higher than at the baseline for 15 participants (79% of the entire sample, between 60% and 100% of the participants per mobile game). A change was observed immediately after the intervention started (latency) in three participants. A decrease in the engagement mean scores at the withdrawal was observed in 10 participants (53%). Three participants showed a decreasing trend during the baseline and an increasing trend during the intervention. The engagement increased statistically significantly, according to the 2SD band method, in seven participants (P7, P8, P9, P18, P21, P23, and P24) (37% of the entire sample, between 25% and 40% of the participants per mobile game) (see ).

Affect

Three series of data at the intervention phase showed an autocorrelation which was corrected before performing the visual and statistical analyses. All the PA-NA values at every phase were positive, indicating that the participants experienced more positive affect than negative affect during the study (see ). Visual analysis of the levels revealed that the affect mean at the intervention was higher than at the baseline for 15 participants (79% of the entire sample, between 50% and 100% of the participants per mobile game). A change was observed immediately after the intervention started (latency) in five participants. A decrease in the PA-NA scores at the withdrawal was observed in ten participants (53%). Three participants showed a decreasing trend during the baseline and an increasing trend at the intervention. The PA-NA scores increased statistically significantly according to the 2SD band method in four participants (P9, P18, P19, and 24) (21% of the entire sample, between 10% and 25% of the participants per mobile game) (see ).

Cognitive functions

shows the scores for the cognitive functions for each participant at each measurement point (T0, T1, T2, and T3). Three participants with dementia demonstrated a MoCA score at T2 (assessment immediately after the Intervention phase ended) higher than their scores at T1 (assessment immediately after the Baseline phase ended) (P2, P3 and P14). For eight participants (42%), the highest MoCA score was obtained at T3 (assessment immediately after the Withdrawal phase ended). Three of these participants reported a diagnosis of dementia (P2, P10, and P14), and one (P19), who did not report a diagnosis of dementia but had a MoCA score of 19 (corresponding to a mild cognitive impairment) at the pre-baseline, also had her highest MoCA score at the end of the study (T3). With regard to the TMT B-A, which provides a measure of central executive functioning, five participants (26%), one (P8) with dementia, had their best performance at T2 (assessment immediately after the Intervention phase ended). Two participants (11%), one (P3) with dementia, had their best performance at T3 (assessment immediately after the Withdrawal phase ended). P12’s MoCA score at the pre-baseline was 3.

Table 4. Cognitive measures per participant.

Regarding their current mood, in 96.68% of the sessions the participants felt either normal or particularly good. Nine participants reported events at 18 sessions, including positive events such as attending an enjoyable activity (e.g., an opera), and negative events such as ailments, tiredness, and busy traffic. These events seemed to impact the participants’ affect at two sessions, and their engagement at five sessions.

Social validation

The analysis of the interviews revealed four themes related to the participants’ experience of the study, namely, (i) challenge, (ii) enjoyment, (iii) preference for mobile games over paper-based games, and (iv) the perceived benefits of the mobile games. Participants enjoyed the challenging aspect of the mobile games. They also regarded this challenge as an incentive to improve their performance. For example, P18 said, “I enjoyed it, it challenges my mind.” Conversely, a lack of challenge undermined their enjoyment; for example, P3, a participant with dementia said that, “It [the Word Search mobile game] was so repetitive.”

Every participant except one (P21) responded that they preferred the mobile games to the paper-based games. The participants preferred the mobile games over paper-based games because the easier interaction and learning; the faster pace; and receiving in-the-moment feedback. For example, P15 said, “I think I liked the tablet better. Just the way it functions. As soon as you complete a word, the colours change, so I knew that I had the word correct.”

With regard to the perceived benefits of the mobile games, some participants reported that they did not notice any changes in themselves, but others reported changes. Seven participants reported that they noticed increased attention or overall cognition as a result of playing the mobile games. P19 said, “…and you’re more alert. … Yeah, I think my son thinks I’m more alert.” P18 reported, “Certainly I find myself more focused … the days I came here [to the study].” P17 said, “Well I noticed that sometimes my brain worked a little bit faster. Actually, after you play, your brain gets into good gear.” When asked if they had noticed any changes in their mother’s cognition over the course of the study, P13, the daughter and caregiver of P12 said, “Yeah, there was definitely improvement in cognition. And thinking, and connecting with memories.” P1 said about her husband who has dementia, “I think throughout the study he’s been really level and not confused.”

Some of the participants enjoyed the social interaction that the study provided. They felt that playing the mobile games brought more opportunities for social interaction. P18 said, “People would go out to play it, any of the mobile games, as a way to go out. People need that conversation. They need to be out with people.”

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to investigate the effect of playing four mobile games on engagement, affect, and cognitive functions in older adults with and without cognitive impairment. In general, our participants showed a positive affect and high levels of engagement during the study. Regarding research question one, a statistically significant increase at the intervention compared with the baseline was observed in 37% (7/19) of the participants’ engagement and in 21% (4/19) of their affect. According to the evidence assessment rules for single-case designs, we found a non-effect in each mobile game, as less than 75% of the participants per mobile game demonstrated a significant improvement at the intervention in their engagement or affect. Pertaining to research question two, three participants with dementia showed an increase in their MoCA scores after the intervention and one participant with dementia showed improvement in their performance in the TMT B-A after the intervention.

Our results agree with previous studies that report that older adults with and without dementia are able to engage in activities using video game technologies with improvements in mood. Citation48–50 Although our study did not demonstrate that playing the four mobile games resulted in a statistically significant increase in all of our participants’ affect or engagement (research question one), we reported some notable findings. First, most of the participants (almost 80%) showed an increase in their levels of engagement and positive affect during the intervention compared to the baseline, and this change was statistically significant in some of the participants. This result was validated during interviews, when all but one participants said that they enjoyed the mobile games compared to the paper-based games. According to the Flow Theory, two of the conditions for reaching a Flow State are clear goals of the task and immediate feedback. Citation9 We believe that these two conditions depend more on the features of the game material (e.g., paper based versus mobile games) than on the players’ skills. The mobile games developed by our team incorporated these two flow state characteristics as technical features; for example, the goals of the mobile games were clearly stated, and the feedback provided by the mobile games was clear, immediate, and multisensory (i.e., visual and auditory). These features helped our participants to feel engaged in a flow-producing activity. Our results showed that this was particularly noticeable for those participants who played the Word Search game, where all of the participants showed an increase in their levels of engagement and affect at the intervention. Second, although P12 was not able to fill out the PANAS or engagement questionnaire, according to our field notes she tolerated the mobile games better. In contrast, she was reluctant to complete the paper-based games. Third, more than half of the participants showed a slight decrease in engagement and affect when the mobile games were withdrawn.

The fact that our results were not statistically significant for engagement or affect may have been due to several reasons. First, we asked our participants to play the same mobile game throughout the entire intervention. Our rationale for this was that we wanted to isolate the effects of each game. As a result, some of the participants felt like they were doing a repetitive task for a long time. Playing the same mobile game repeatedly may have caused some of our participants to enter a state of boredom which, according to the Flow Theory, is opposite to being in a flow state. Citation9 The information from the interviews supported this assertion. Second, two participants showed a significant decrease in the outcome variables during the intervention in their affect (P1 and P4) and engagement (P1). These two participants were cognitively healthy and were randomly assigned to the most repetitive mobile games (i.e., Whack-A-Mole and Bejeweled). A balance between a task’s challenges and an individual’s skills is a factor in reaching a flow state and associated positive affect. Citation9 Thus, the fact that the participants’ skills were too high for certain mobile games may have contributed to a decrease in the outcome variables during intervention. Third, our research setting was designed for the participants to play alone, although they were in the same room. On some occasions, our participants reported that some of the conversations between the research assistants and the other participants, or verbal utterances made by some of the participants while they were playing the mobile games, affected their concentration and performance during their own gameplay. Also, during the baseline and withdrawal phases we observed that some participants, especially those with cognitive impairments, relied on the research assistants for clarification for the paper-based games, so social interactions occurred very frequently. At the intervention, social interactions with the research assistants were less frequent and were limited to technical problems with the mobile games. Thus, the social environment played a role in the results, either in the way that other people’s presence led to difficulties in concentrating during gameplay, or in that social interactions with the research assistants led the participants to overscore the outcome variables at the baseline and withdrawal phases, as they enjoyed and valued the social interactions associated with participating in the study.

Regarding research question two, the results from the older adults with dementia indicate a considerable variability in the participants’ performance in the MoCA. However, three participants’ MoCA scores were higher at the end of the intervention compared with their scores at the pre-baseline and at the end of the baseline (P2, P3, and P14). Interestingly, three participants (P2, P10, and P14) had the highest MoCA scores at the end of the Withdrawal phase compared to their scores at the precedent phases, showing an increase of between one and four points on this test. Even for P14, the last MoCA measurement was 28, which, according to the test cutoff scores, corresponded with having no cognitive impairment. Citation51 Reversion from having a mild cognitive impairment to being cognitively normal has been conservatively estimated at 5% to 10% per year. Citation20 However, this reversion has not been fully characterized. Citation52 P3, the participant with the lowest MoCA at the pre-baseline, increased by five points at the end of the intervention, while her score returned to the pre-baseline score after the study ended. Further, 89% (8/9) of the participants with the highest MoCA scores either at the end of the intervention or at the end of the study were those with dementia or the oldest in our sample. These results were consistent with previous research of three meta-analyses. Hill and colleagues Citation20 reported that the use of computerized cognitive training, including computer games, had a moderate effect size for participants with mild cognitive impairment and a small to moderate effect size for participants with dementia in terms of overall cognition. Also, larger effect sizes in overall cognition have been reported in participants older than 70 years than in those between 60 and 70 years of age. Citation15,Citation53

In general, the cognitive functions of the participants without any cognitive impairments were quite stable. Interestingly, P7, P9, and P17 had low MoCA scores at the pre-baseline measurement, which increased after the baseline finished and remained high for the rest of the study. We believe that this change could not have been attributed to the intervention, but to a learning effect or a change in personal conditions. Anxiety has been found to affect performance in cognitive tests in older adults without dementia. Citation54

Similarly, with the MoCA the TMT B-A scores showed significant variability in the participants’ performance. With such variability, we do not have a clear idea about the effects of the mobile games on these higher-level cognitive skills. In a systematic literature review, Sood and colleagues Citation19 found that some studies reported significant changes in attention combined with executive functioning in older adults with cognitive impairments, while others did not. Nguyen and colleagues Citation15 found that in cognitively intact older adults, at least 36 hours of multi-domain training is required before any effect on executive functioning can be observed. Thus, our intervention may have been too short to have an effect on executive functions. Although it is difficult to draw conclusions from this small and variable sample to answer research question two, our study contributes to the further possibility of exploring more in-depth, and with larger sample sizes, the effects of specially designed mobile games on the overall cognition and specific cognitive domains of older adults, including those with dementia.

The Word Search game showed the most promise as a cognitive activity that helps older adults to reach a flow state. All the games kept the participants engaged for 30 minutes. In fact, the simple rules of Whack-a-Mole game allowed a participant with moderate dementia to tolerate and enjoy the sessions. The length of sessions of a minimum of 30 minutes has shown to have an effect on older adults’ cognitive functions. Citation17 Thus, games similar to the four in Vibrant Minds can be used to engage older adults living with dementia in flow-producing activities, either in a supportive housing or community organization context.

Limitations

This study had some methodological limitations. The main limitation was the presence of short baselines. There were four participants with only two data points, and eight with three data points at the baseline. With such short baselines, some changes that may have occurred over time could not be captured; for example, a decreased trend in affect and engagement during the baseline. From the TMT B-A results, we observed that seven out of the ten participants whose best performance in the test was after the baseline ended had between two and three data points at the baseline, which was between one and one and a half weeks between the measurement times. The TMT was found to have large practice effects when administered less than six weeks apart. Citation36 Thus, the performance at the end of the baseline for these participants could have been impacted by the short baselines. Second, the version of MoCA we used in all the measurement points was the same. The results could respond to the practice effect even in those participants with dementia. Third, we observed considerable variability in the participants’ cognitive measures performance. Fourth, there were some technical and space issues; for example, there were problems with the Wi-Fi, the mobile games stopped working or automatically restarted, or the room assigned to our study was double-booked, so the participants had to move to a different room. Fifth, a few times we conducted two sessions on the same day due to the participants having other commitments.

Conclusion

This study shows that older adults with and without dementia tended to experience engagement in flow-producing activities and feel positive affect while playing four mobile games developed for cognitive training. However, the levels of engagement and affect were not statistically higher while playing the mobile games compared with those doing paper-based cognitive activities. Although the cognitive measures showed considerable variability between the measurement times, engagement in cognitive activities in the form of mobile games has the potential to positively impact the cognitive skills assessed by the MoCA in some older adults, in particular the oldest ones and those with dementia. The results indicate feasibility and acceptability of the intervention, and inform on the design of future studies with larger sample sizes, longer interventions, and outcome measures that account for the variability in the performance of older adults with dementia.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the study participants and sites (Alzheimer Society of Alberta and Northwest Territories, Revera) for contributing their time and feedback. We would also like to thank the research assistants, occupational therapy and computing science students, for their help with developing the Vibrant Minds games and with collecting and analyzing the data. Finally, we would like to thank Burn Evans and Ken Yu for their contributions to the game designs and instructional videos.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Livingston G, Sommerlad A, Orgeta V, et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care. The Lancet. 2017;390(10113):2673–2734. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31363-6.

- Carrion C, Folkvord F, Anastasiadou D, Aymerich M. Cognitive therapy for dementia patients: A systematic review. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2018;46(1–2):1–26. ():doi:https://doi.org/10.1159/000490851.

- Fitzpatrick-Lewis D, Warren R, Ali MU, Sherifali D, Raina P. Treatment for mild cognitive impairment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. CMAJ Open. 2015;3(4):E419–27. doi:https://doi.org/10.9778/cmajo.20150057.

- Sherman DS, Mauser J, Nuno M, Sherzai D. The efficacy of cognitive intervention in mild cognitive impairment (MCI): a meta-analysis of outcomes on neuropsychological measures. Neuropsychol Rev. 2017;27(4):440–484. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11065-017-9363-3.

- Alzheimer Society of Canada. Guidelines for care: Person-centred care of people with dementia living in care homes. Framework. Guidelines for care. Person-centred care of people with dementia living in care homes: Executive summary. August 11, 2017. https://alzheimer.ca/en/Home/We-can-help/Resources/For-health-care-professionals/culture-change-towards-person-centred-care/guidelines-for-care. Accessed February 14, 2019.

- Yoshida K, Asakawa K, Yamauchi T, et al. The flow state scale for occupational tasks: Development, reliability, and validity. Hong Kong J Occup Therapy. 2013;23(2):54–61. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hkjot.2013.09.002.

- Fredricks JA, Filsecker M, Lawson MA. Student engagement, context, and adjustment: Addressing definitional, measurement, and methodological issues. Learn Instruct. 2016;43:1–4. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2016.02.002.

- Watson D, Wiese D, Jatin V, Tellegen A. The two general activation systems of affect: Structural findings, evolutionary considerations, and psychobiological evidence. J Personal Soc Psychol. 1999;76(5):820–838. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.76.5.820.

- Csikszentmihalyi M, Abuhamdeh S, Nakamura J. Flow and the Foundations of Positive Psychology. Netherlands: Springer; 2014.

- Hoppes S, Wilcox T, Graham G. Meanings of play for older adults. Phys Occup Ther Geriatr. 2001;18(3):57–68. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/J148v18n03_04.

- Wilkinson P. A Brief History of Serious Games. In: Dörner R., Göbel S., Kickmeier-Rust M., Masuch M., Zweig K. (eds) Entertainment Computing and Serious Games. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol 9970. Springer, Cham; 2016. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-46152-6_2.

- Jegers K. Elaborating eight elements of fun: supporting design of pervasive player enjoyment. Comput Entertain. 2009;7(2):1–3574. doi:https://doi.org/10.1145/1541895.1541905.

- Klimmt C, Hartmann T. Effectance, Self-Efficacy, and the Motivation to Play Video Games. Playing Video Games: Motives, Responses, and Consequences. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; 2006.

- Gates NJ, Vernooij RW, Di Nisio M, et al. Computerised cognitive training for preventing dementia in people with mild cognitive impairment. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;3(3):CD012279. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD012279.pub2.

- Nguyen L, Murphy K, Andrews G. Immediate and long-term efficacy of executive functions cognitive training in older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol Bull. 2019;145(7):698–733. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000196.

- Gates NJ, Rutjes AWS, Di Nisio M, Cochrane Dementia and Cognitive Improvement Group, et al. Computerised cognitive training for maintaining cognitive function in cognitively healthy people in late life. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019; 1–94. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD012277.pub2.

- Lampit A, Hallock H, Valenzuela M. Computerized cognitive training in cognitively healthy older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis of effect modifiers. PLoS Med. 2014;11(11):e1001756. doi:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001756.

- Palumbo V, Paternò F. Serious games to cognitively stimulate older adults: a systematic literature review. Paper Presented at: Proceedings of the 13th ACM International Conference on PErvasive Technologies Related to Assistive Environments, 2020.

- Sood P, Kletzel SL, Krishnan S, et al. Nonimmersive brain gaming for older adults with cognitive impairment: a scoping review. Gerontologist. 2019;59(6):e764–e781. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gny164.

- Hill NTM, Mowszowski L, Naismith SL, Chadwick VL, Valenzuela M, Lampit A. Computerized cognitive training in older adults with mild cognitive impairment or dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatr. 2017;174(4):329–340. doi:https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2016.16030360.

- Lobo MA, Moeyaert M, Baraldi Cunha A, Babik I. Single-case design, analysis, and quality assessment for intervention research. J Neurol Phys Ther. 2017;41(3):187–197. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/NPT.0000000000000187.

- Daum C, Rios-Rincón A, Miguel-Cruz A, et al. Computer games for older adults: Findings of a usability study. Paper Presented at: Canadian Association of Occupational Therapists, 2018. Vancouver.

- Thomas H. Occupation-Based Activity Analysis. 2nd ed. Grove Road: Slack Inc; 2015.

- Rios-Rincon A, Miguel-Cruz A, Liu L, Stroulia E. Computer games for older adults – engagement as an outcome. Paper Presented at AGE-WELL 2018 Conference, 2018. Vancouver, BC.

- Rios Rincon A, Miguel-Cruz A, Liu L, Stroulia E. Engagement during computer serious games: A rapid literature review. Paper Presented at: Canadian Association on Gerentology Conference; October, 2017. Winipeg.

- Liu L, Rios Rincon A, Daum C, Miguel-Cruz A, Altura K, Stroulia E. Two measures of engagement developed for older adults living with dementia. October, 2018.

- Watson D, Clark L, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1988;54(6):1063–1070. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.1063.

- von Humboldt S, Monteiro A, Leal I. Validation of the PANAS: A measure of positive and negative affect for use with cross-national older adults. RES. 2017;9(2):10–19. doi:https://doi.org/10.5539/res.v9n2p10.

- Buz J, Pérez-Arechaederra D, Fernández-Pulido R, Urchaga D. Factorial structure and measurement invariance of the PANAS in Spanish order adults. Spanish J Psychol. 2015;18:1–11.

- Ostir GV, Smith P, Smith D, Ottenbacher KJ. Reliability of the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS) in medical rehabilitation. Clin Rehabil. 2005;19(7):767–769. doi:https://doi.org/10.1191/0269215505cr894oa.

- Nasreddine Z, Phillips N, Chertkow H. MoCA Version 3. MoCA. January 1, 2011. www.mocatest.org. Accessed November 8, 2016.

- Lam B, Middleton LE, Masellis M, et al. Criterion and convergent validity of the Montreal cognitive assessment with screening and standardized neuropsychological testing. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(12):2181–2185. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.12541.

- Julayanont P, Tangwongchai S, Hemrungrojn S, et al. The montreal cognitive assessment_basic: a screening tool for mild cognitive impairment in illiterate and low-educated elderly adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(12):2550–2554. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.13820.

- Gill DJ, Freshman A, Blender JA, Ravina B. The Montreal cognitive assessment as a screening tool for cognitive impairment in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2008;23(7):1043–1046. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/mds.22017.

- Koski L, Xie H, Finch L. Measuring cognition in a geriatric outpatient clinic: Rasch analysis of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2009;22(3):151–160. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0891988709332944.

- Bowie CR, Harvey PD. Administration and interpretation of the Trail Making Test. Nat Protoc. 2006;1(5):2277–2281. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/nprot.2006.390.

- Kortte KB, Horner MD, Windham WK. The trail making test, part B: cognitive flexibility or ability to maintain set? Appl Neuropsychol. 2002;9(2):106–109. doi:https://doi.org/10.1207/S15324826AN0902_5.

- Sánchez-Cubillo I, Periáñez J, Adrover-Roig D, et al. Construct validity of the Trail Making Test: Role of task-switching, working memory, inhibition/interference control, and visuomotor abilities. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2009;15(3):438–450. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S1355617709090626.

- Fals-Stewart W. An interrater reliability study of the Trail Making Test (Parts A and B). Percept Mot Skills. 1992;74(1):39–42. doi:https://doi.org/10.2466/pms.1992.74.1.39.

- Barker-Collo S, Feigin V, Lawes C, Senior H, Parag V. Natural history of attention deficits and their influence on functional recovery from acute stages to 6 months after stroke. Neuroepidemiology. 2010;35(4):255–262. doi:https://doi.org/10.1159/000319894.

- Kratochwill TR, Hitchcock J, Horner RH, et al. Single-case design technical documentation Version 1.0 (Pilot). What Works Clearinghouse. 2010. http://ies.ed.gov/ncee/wwc/pdf/reference_resources/wwc_scd.pdf. Accessed December 12, 2013.

- Gresham FM. Treatment Integrity in the Single-Subject Research. Design and Analysis of Single-Case Research. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1996.

- Subramaniam K, Kounios J, Parrish TB, Jung-Beeman M. A brain mechanism for facilitation of insight by positive affect. J Cognit Neurosci. 2008;3(21):415–432.

- Portney LG, Watkins MP. Foundations of Clinical Research: Application to Practice. 3rd ed. New Jersey: Prentice-Hall. Inc; 2008.

- Ottenbacher K . Analysis of data in idiographic research. Issues and methodsAm J Phys Med Rehabil. 1992;71(4):202–208. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/00002060-199208000-00002.

- Kazdin AE. Single-Case Research Designs. Methods for Clinical and Applied Settings. NY: Oxford University Press; 2011.

- Hsieh H, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277–1288. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687.

- Astell A, Alm N, Dye R, Gowans G, Vaughan P, Ellis M. Digital video games for older adults with cognitive impairment. Paper Presented at: Computers Helping People with Special Needs. ICCHP 2014. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, 2014. Cham.

- Belchior P, Marsiske M, Sisco S, Yam A, Mann W. Older adults’ engagement with a video game training program. Act Adapt Aging. 2012;36(4):269–279. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01924788.2012.702307.

- Moyle W, Jones C, Dwan T, Petrovich T. Effectiveness of a virtual reality forest on people with dementia: A mixed methods pilot study. The Gerontol. 2018;58(3):478–487. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnw270.

- Tan J, Li N, Gao J, et al. Optimal cutoff scores for dementia and mild cognitive impairment of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment among elderly and oldest-old Chinese population. J Alzheimers Dis. 2015;43(4):1403–1412. doi:https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-141278.

- Roberts RO, Knopman DS, Mielke MM, et al. Higher risk of progression to dementia in mild cognitive impairment cases who revert to normal. Neurology. 2014;82(4):317–325. doi:https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000000055.

- Toril P, Reales JM, Ballesteros S. Video game training enhances cognition of older adults: a meta-analytic study. Psychol Aging. 2014;29(3):706–716. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037507.

- Meltzer EP, Kapoor A, Fogel J, et al. Association of psychological, cognitive, and functional variables with self-reported executive functioning in a sample of nondemented community-dwelling older adults. Appl Neuropsychol: Adult. 2017;24(4):364–375. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/23279095.2016.1185428.