ABSTRACT

There are no consistent answers to why challenging behaviour is perceived to be a problem across time and place. This article explores challenging behaviour and how it is constructed as a problem by professionals in North West England. The research was designed as a qualitative single case study that analysed the perspectives of staff from two primary schools and a local authority. The works of Michel Foucault and his interlocutors form the basis of the theoretical framework. This article shows that there are competing perspectives amongst practitioners regarding the problem of challenging behaviour. Deconstructing representations of challenging behaviours offers practitioners and researchers insight into how differing constructions of the problem shape policy solutions and educational experiences in schools.

Introduction

This article explores how challenging behaviour is constructed, by professionals, in mainstream primary schools in North West England. I examine how pupils with challenging behaviour are identified and understood as a problem. In UK schooling, the implementation of practice-based policy is often shaped and developed by larger-scale government policies. The Office for Standards in Education (Ofsted) is a (non-ministerial) department of the UK government, responsible for inspecting school standards and policy implementation including those related to pupil behaviour. Over recent decades within the UK, behaviour management has emerged as an area of professional training and development that has generated many ‘tools’ and approaches that have been implemented with varying degrees of success (Bennett Citation2017; DfE 2016a; Menzies and Baars Citation2015; Ofsted Citation2012; Emerson Citation2001; Cooper Citation1999). Teachers in England are required to manage pupil behaviour as part of their professional performance as outlined in the teaching standards (DfE Citation2012). ‘Challenging’ behaviour is a contested term adopted by schools in the UK to define pupil behaviour that teachers may find difficult to manage. Solutions for tackling ‘challenging’ behaviour have formed part of government policies for many decades, including the recent Special Educational Needs and Disability (SEND) Code of Practice (2015); however, the problem persists despite many studies and constant policy attention.

In England, the SEND Code of Practice (2015) was published with the expectation that professionals identify the underlying reasons why pupils may present with ‘challenging’ behaviour. This policy drew attention to causation as the problem focusing on underlying difficulties a pupil may be identified as having. Pupils consistently identified as presenting with challenging behaviour may be categorised as having or experiencing ‘Social, Emotional and Mental Health Difficulties’ (SEMHD). As demands on schools increase, resources are further stretched and policies and guidelines, such as the SEND Code of Practice, highlight the difficulty in locating a planned and/or open assessment of resources to implement government policy (HoC Citation2018). Clarity on how challenging behaviour is problematised is difficult to achieve if different stakeholders, such as those within schools and local authorities, have different interpretations of what the ‘problem’ is.

The expectations and descriptions of pupils’ behaviour have been continually reviewed and changed within English schools. Currently, behaviours perceived to fall outside of expected norms are often categorised and placed within an educational, social and health model that is supported by the SEND Code of Practice. This policy is also influenced by debates surrounding two main competing models of disability: (1) a social model; and (2) a medical model. The medical model assumes that a pupil’s disabilities are the problem and need to be fixed. In contrast, the social model does not identify the individual with special educational needs and disabilities as the problem. The problem is instead located in society and a pupil’s difficulty accessing society is attributed to factors such as a lack of responsiveness or support. As Childerhouse argues, ‘professionals implementing the documentation [SEND Code of Practice], such as classroom teachers, will be influenced by the discourses dominant within the policies’ (Citation2017, 21).

The categorisation and problematisation of challenging behaviour encompass different contextual features such as environment and social and cultural expectations (Cole and Knowles Citation2011; Emerson Citation2001; Cooper Citation1999). An emphasis on ‘fixing’ the pupil is often seen as the solution when their behaviour is deemed challenging and problematic (Maguire, Ball, and Braun Citation2010). An increased number of pupils identified as ‘challenging’ and unmanageable in mainstream schools has resulted in higher referrals and admission to alternative provision such as special schools and pupil referral units (DfE Citation2017; HoC Citation2018).

Many authors have identified how pupils are manoeuvred through a system that categorises their behaviour to justify actions applied to them (Childerhouse Citation2017; McClusky et al. Citation2016; MacLure et al. Citation2012; Maguire, Ball, and Braun Citation2010; Graham, Citation2005a; Macleod Citation2006). The expectations and pressures upon professionals to enact a policy are often compounded by the differing perceptions and discourses that shape the interpretation and implementation of individual or competing policies (Casimiro Citation2016; Braun, Ball, and Maguire Citation2011; Ball Citation1993, Citation2003). As a practitioner and researcher, I believe there is a need to revisit policies and practices in order to critically analyse the discursive constructions underpinning how a problem such as ‘challenging’ behaviour is represented. The main aims and purposes of this article are to deconstruct how professionals problematise challenging behaviour.

In this article, I will give a brief account of the theoretical framework on which my findings are underpinned. Next, I will explain the methodology and research design, providing a detailed description of the context and how the data were analysed. Then, I move on to a detailed account of my study findings followed by some concluding remarks.

Theoretical framework

My theoretical framework is underpinned by a Foucauldian perspective. Foucault (Citation1972, Citation1977, Citation1984) identifies discourse as a process that establishes and embeds knowledge within practice. Foucault does not look to solve problems but rather seeks to understand how problems have been constructed, as I aimed to do in my study.

As an educational practitioner, it has been important to bring Foucault’s works into a contemporary framework that has credible theoretical foundations but also provides tools for a practitioner and researcher such as myself to explore phenomenon such as challenging behaviour. Therefore, I have drawn on the work of several authors who have developed approaches drawing on Foucault (Bacchi Citation2012; Graham Citation2011; Hacking Citation2007). The work of these scholars’ transports Foucault’s concepts into the exploration of contemporary education, making his ideas and concepts more easily accessible to practitioners and researchers.

First, Hacking (Citation2007) provides a contemporary interpretation of how discourse becomes knowledge. Building on Foucaults works, Hacking refers to ‘engines of discovery’ and emphasises how administrative systems are used by professionals to mobilise discourse and to establish ‘truths’.

Secondly, Graham (Citation2005a, 2005b, Citation2011) conducted research in primary schools in Australia and demonstrated how a Foucauldian approach to discourse analysis, can be successfully applied to interpret and analyse the problematisation of challenging behaviour. Drawing upon Graham’s work, this study applies Foucauldian discourse analysis in the different context of English schools and specifically in relation to my own professional practice.

Thirdly, the works of Bacchi (Citation2012), particularly her ‘What is the problem represented to be?’ (WPR) framework, has provided a practical approach to investigate how and why a problem is constructed. Bacchi highlights how the analysis of policy and practice provides an insight into the interpretations of a given ‘problem’ and what is left unproblematised.

Foucault’s writings have inspired many researchers to demonstrate how they can apply aspects of his methodology to their work (Freie and Eppley Citation2014; Raaper Citation2016; Graham Citation2011; Cooke Citation1994). However, as Graham (Citation2011) argues, there are no actual rules, clear processes or general methods in Foucault’s approach. Graham suggests that to argue Foucault had a precise approach to research methodology would be hypocritical as this is opposite to what Foucault advocates throughout his works. This makes it difficult to follow one ‘true’ Foucauldian approach. Therefore, using Foucauldian theory may be viewed as ‘inaccessible and dangerous, which deters some researchers from engaging with this form of analysis, particularly those in more practice-oriented fields’ (Graham Citation2011, 2). In response, Graham (Citation2011) claims that a Foucauldian analysis of discourse can be undertaken by analysing three processes: (1) description of how things are validated; (2) recognition of how discourse validates the description; and (3) classification of the body of knowledge that validates statements.

To explore how challenging behaviour is constructed as a problem in education, Foucauldian-inspired approaches, such as Bacchi’s (Citation2012) What is the problem represented to be? (WPR) framework, encourage the researcher to investigate the strategies and forces involved in the problematisation process. Bacchi (Citation2012) has provided us with a useful tool to undertake this investigation. Her six guiding questions attempt to identify the meanings and implications behind a policy’s creation. Bacchi’s (Citation2012, 21) questions to be applied in the analysis of problem representation are:

What is the problem?

What presuppositions or assumptions underpin this representation of the problem?

How has this representation of the problem come about?

What is left unproblematic in this representation? Where are the silences? Can the problem be thought about differently?

What effects are produced by this representation of the problem?

How/where has the representation of the problem been produced, disseminated and defended? How has it been (or could be) questioned, disrupted and replaced?”

Using these questions to critically analyse policy, according to Bacchi, reminds us that both problem and solutions are ‘heavily laden with meaning’ (Citation2012, 23) that may be presupposed by policy writers and subjects of policy. Unravelling discourses attached to a problematisation aids the understanding of why the problem is perceived as such. The WPR framework provides an aid to discourse analysis, which can help researchers to understand policy practices but also to apply this critical analytical approach more broadly.

Through Foucault’s understanding of problematisation, a researcher is able to deconstruct established ‘truths’ that have been woven through discursive frameworks. Arguing that problematisation occurs through discursive frameworks and practice depends on the view ‘that truth is always contingent and subject to scrutiny’ (Graham Citation2011, 4).

Methodology

To understand how challenging behaviour in schools has become problematised, I worked within an interpretive paradigm drawing on a Foucauldian approach. I applied an inductive approach to what people do and how they do it by identifying features of discourse, administrative measures and practice actions as if they were techniques or devices. This in turn has assisted ‘in identifying connections between different elements that exist’ in the problematisation of pupil’s behaviour (Cooke Citation1994, 57).

Case study design

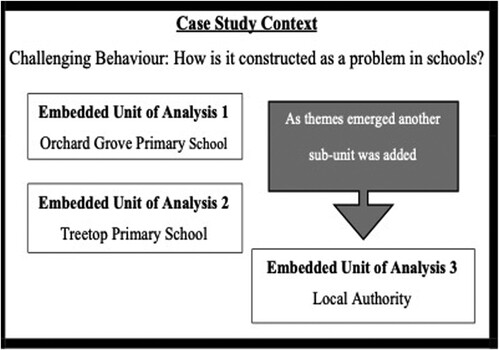

I adopted an embedded single case study design, as described by Yin (Citation2003), allowing me to collate data from different sources within the same context. State run schools within England are governed by a local authority (LA) within the same geographical location. Two state mainstream primary schools and one LA from the same geographical area were included in this case study. The number of pupils, in both schools, with special educational needs (SEN), pupils on free school meals (FSM), ‘disadvantaged’ pupils receiving pupil premium funding (PPF) and pupils who receive support for SEND are all above the national average.

The main data collection method employed in my case study was interviews with professionals in schools and the LA. All interviews were semi-structured. Having a more open structure facilitated the emergence of themes rather than dictating them. To ensure anonymity and confidentiality, I used a pseudonym for each school and only referred to respondent’s job title rather than their name. Throughout this research project, data was collected in line with the British Educational Research Association recommendations to ensure it is of a high ethical standard (BERA Citation2018).

Initially, I focused my research within two mainstream primary schools and used pseudonyms – Orchard Grove Primary School and Treetop Primary School. As the study evolved, it was evident that the LA, who govern these schools and also supply services to support pupils, were often perceived by school participants as part of the ‘problem’. I, therefore, decided to include LA participants to enrich my data and provide a more balanced analysis.

Using a case study approach to explore the discourse, professional knowledge and actions in schools and a LA has enabled me to ‘cover contextual conditions, believing them to be highly pertinent to the phenomenon of study’ (Yin Citation2003, 12). My single embedded case study contained three sub-units as illustrated in .

Participants’ Context

Three organisations took part in the main body of this study. Five participants are from ‘Orchard Grove Primary School’, five are from ‘Treetop Primary School’ and three from the LA. Local authorities (LAs) have control over local services, including education, within a given geographical area. They have an administrative function on behalf of the government, such as implementation of policies. Three services of the LA were perceived to have an impact on Orchard Grove and Tree Top schools in relation to challenging behaviour and therefore a senior manager in each of the following services was interviewed.

Special educational needs and disabilities support services

The role of this LA service is to make sure children and young people with special educational needs and/or disabilities are identified and their needs met. They have the responsibility for agreeing additional funding for pupils assessed as needing it.

Behaviour support services

This service is financed by both primary and secondary mainstream schools, although it is managed by the LA. They provide support to schools who have difficulty managing pupils with emotional and behavioural difficulties.

Family services

The development of Family Services has seen the integration of children’s health professionals with LA early years, safeguarding, protection and specialist workers to provide a coordinated and joined up offer to families in need.

Interviewing LA participants and a mix of school staff ensured the ‘breadth and variation among interviewees’ provided a wider response coverage to my research aim and questions (Alvesson Citation2011, 6). A list of all 13 participants and their role are outlined below in .

Table 1. Participants.

Data analysis

I have worked within an interpretive paradigm that incorporates a Foucauldian approach to examining discourse and deconstructing ‘truths’ to understand the problematisation of challenging behaviour. Analysing how the statements from participants are underpinned by ‘bodies of knowledge’ provides a useful pathway to understanding how ‘challenging’ behaviour is problematised. Drawing on the works of Bacchi (Citation2012) and Graham (2005, Citation2011), I carried out a thematic discourse analysis through a Foucauldian lens and within a framework that provided consistency and rigour.

Maguire, Ball, and Braun (Citation2017, 3354), drawing on the works of Braun and Clarke (Citation2006), suggest that a six-step framework is useful when undertaking thematic analysis and I used a similar approach when conducting my analysis. The six steps in the framework are:

Become familiar with the data

Generate initial codes

Search for themes

Review themes

Define themes

Write-up themes

I took an inductive approach to search for data using the six-step thematic framework. As themes became more concrete, I began to match them consistently with the research questions and the theoretical/conceptual framework. Braun and Clarke (Citation2006) do not see these steps as linear or inflexible but used in relation to research questions. According to Braun and Clarke (Citation2006, 84), there are two distinguishable levels of themes: the ‘semantic’ level that looks at the surface meaning of the data, and the ‘latent’ level that goes beyond this and examines ‘the underlying ideas, assumptions, and conceptualisations – and ideologies – that are theorised as shaping or informing the semantic content of the data.’ Conducting a latent level of analysis as themes became more concrete, allowed me to not only look at the semantics in terms of patterns emerging, but to then extend my thematic analysis into a Foucauldian analysis of discourse.

Analysis and discussion

The analysis and discussion in this article focus on three main themes that emerged as significant: (1) how challenging behaviour is perceived; (2) resourcing the problem, and (3) exploring solutions to the problem.

How is challenging behaviour perceived?

All school-based participants said they had experienced and witnessed what they perceive to be challenging behaviour in their schools. However, there was no single definition of a pupil presenting with challenging behaviour within the discourses about behaviour in these schools. This supports the position taken by others who state there is no clear definition of challenging behaviour and it is dependent on the social context (Emerson Citation2001; Cooper Citation1999; Cole and Knowles Citation2011). How challenging behaviour is perceived falls into three main areas: (1) Levels of behaviour; (2) Medicalising challenging behaviour and (3) the LA perspective.

Levels of behaviour

There is a belief in both schools that a ‘regular handful’ of pupils display behaviours that become hard to control within their behaviour management strategies. A few pupils that present challenging behaviour are seen to be continually resisting the disciplinary technologies within schools. This has resulted in staff deeming them unmanageable and consequently, both schools are unable to meet their needs. Staff believed the ability to manage pupils was a problem, with one teacher stating, ‘it becomes challenging when we are unable to manage their behaviour’ (Orchard Grove Class Teacher). The headteacher at Treetop school believed managing behaviour is expected but there are some pupils whose behaviour they are not able to manage.

The three that really struggle, it would be them where I'd be asking for the support. The children [whose] behaviour isn't great, we can accept that, and we can do something about that, but it's the ones with so many needs that it doesn't fall into the remit. (Treetop Headteacher)

Sometimes they withdraw and just do not engage … this can be challenging but usually I can encourage them to get involved before their behaviour escalates or becomes a problem. (Treetop Class Teacher)

I suppose, the classic challenges would be, you have the overt physical aggression when things are being thrown, and the child is really obviously really angry. That's coming out in aggression, that's a challenge. Other kinds of challenge would be around when a child [who] almost does the opposite of that, and they just go completely into themselves. (Orchard Grove Pastoral Manager)

When staff at both Treetop and Orchard Grove discussed ‘high-level’ challenging behaviour, the same few pupils were given as examples of being the most challenging, even by staff who did not work on a regular basis with these pupils. In both schools where these ‘few’ pupils are continually exemplified as ‘challenging’, discourse serves to enhance both the label and the associated problem. The behaviour discourse associated with these pupils appears to be accepted as official knowledge about them and their needs. Bacchi and Bonham (Citation2014) argue that discourse evolves into knowledge. Once a pupil is labelled as having ‘challenging behaviour’ this can be viewed as a ‘true’ assessment of them. From a Foucauldian perspective, it is evident that ‘normalisation’ and accepted levels of behaviour have been established in both schools. As agents of the classification of ‘normal’ and ‘challenging’ behaviour, teachers and other staff look to identify anomalies and then reclassify them as challenging, because it is beyond their control to manage them in the classroom.

‘Medicalising’ challenging behaviour

Mental health was raised by staff across both Orchard Grove and Treetop as a factor contributing to pupils’ behaviour. How and why staff believed pupils to have mental illness was unclear, and from observations of staff, it was not a ‘diagnosis’ based on a professional medical opinion. Several staff believed there to be a lack of mental health expertise and support within, and externally accessible to, schools.

The government guidance on mental health and behaviour in schools states that schools and staff should try to identify pupils with mental health problems.

Only medical professionals should make a formal diagnosis of a mental health condition. Schools, however, are well-placed to observe children day-to-day and identify those whose behaviour suggests that they may be suffering from a mental health problem or be at risk of developing one. This may include withdrawn pupils whose needs may otherwise go unrecognised. (DfE Citation2018, 12)

Orchard Grove, has a pupil resource unit for up to 10 pupils requiring support with profound and multiple learning and physical difficulties. It also caters for other pupils that may be assessed as requiring specialised support. All staff thought that a small number of pupils in the resource unit presented with the most challenging behaviour, in particular a pupil who was previously in a mainstream class and who has consistently displayed challenging behaviour since joining the school. Several staff suggested this pupil should not have been placed in the resource room but could not be taught and managed in her mainstream class either.

This child will refuse to do absolutely anything asked. We very rarely get any work from this child … you will see them around the school, throwing things, destroying the library, breaking things, which she does on a regular basis. It hasn't helped the resource room. You can see a decline with the children in the resource room, in their behaviour, since that child moved into the room. They don't like her, and they're scared of her. (Orchard Grove TA)

Local authority perspective

LA participants held a different perspective on challenging behaviour, arguing that schools are amplifying the ‘problem’ due to the initial approach taken when a pupil does not fit into the usual and expected pattern of behaviour. LA senior managers felt that behaviour in schools is sometimes problematised when it should not be, or that pupils are wrongly labelled. The Family Support Lead (LA-FS) gave an example of visiting a school and, whilst standing inside a school entrance, observing a senior member of staff raising their voice and reprimanding a pupil walking to the entrance who did not have a school tie on. The pupil had his tie in his pocket. This pupil was previously identified as a ‘challenge’ and when approached in this way the label was reinforced by him being verbally abusive. It later emerged that the pupil had intended to wear his tie as soon as he was in school, but because he had been approached in such a way, his behaviour confirmed the senior teacher’s perceptions. As this participant explained, ‘[t]here is an assumption that if pupils don’t behave as expected [wearing a tie] they are a problem’ (LA-FS).

Other LA participants also questioned the approach taken by schools when dealing with pupils who present with ‘challenging’ behaviour. They believed more could and should be done in schools to support pupils and prevent them from becoming identified as having challenging behaviour that then becomes a problem. The LA SEND manager believed; ‘Pupils are labelled at the lower-level disruption stage and then escalated to challenging behaviour rather than being dealt with and helped at low-level stage.’ The LA behaviour support manager believed schools need to identify ‘the behaviours that are causing the difficulty and how is the difficulty described, what is the barrier to learning? (LA-BSS)

There is an inconsistency between schools and the LA in terms of how challenging behaviour is constructed, including in relation to views about when and why it is a problem. The discourse appears multi-faceted, with actors not being consistent in their interpretation of the ‘what’, ‘how’ and ‘why’ of behaviour that is perceived as a problem. This may be due to the differing context in which problematisation takes place, such as policy implementation and resource allocation, and how practice is embedded in those contexts (Ball Citation1993; Casimiro Citation2016; Bacchi Citation2012).

Resourcing the problem

The financial and resource implications of meeting the needs of ‘challenging’ pupils, whichever approach is seen to be most benefiting, was a constant aspect of all participants’ problematisation of challenging behaviour. This section explores how as schools work within a finite budget, the management of resources becomes a crucial element of enacting policies, procedures and practice. This is evident in the implementation of the SEND Code of Practice (2014) and the management of resources.

The SEND code of practice

Those pupils identified as needing SEND support, fall within one or more of four categories (sensory/physical, communication/interaction, cognitive/learning or social, emotional and mental health difficulties). An outcome of labelling pupils within the SEND Code of Practice is acknowledgment that they have the right to support and resources. An education, health and care (EHC) plan is a tool identified within the SEND Code of Practice to identify a pupil’s needs and how they can be met. Information collated and submitted from schools on their observations of a pupil, and the impact of support already in place, forms part of the assessment process. The LA uses this information to decide if the initial assessment process has correctly identified unmet needs that require ongoing assessment and intervention arrangements, through the implementation of an EHC plan. If the schools documented evidence within the initial assessment is considered insufficient, the LA can refuse to implement an EHC plan. Schools then have to continue to implement different strategies within their own resources to meet the pupils’ unmet needs until they have enough ‘evidence’ to demonstrate the pupil’s need for an EHC plan. A report published by the Department of Education (Citation2019) stated that, nationally, a significant number of mainstream pupils with SEND requiring additional support did not have an EHC plan. The report claims that the drop in the provision of EHC plans is likely to be related to how pupils are identified as needing a plan and how the application process is administered.

The administrative response of collecting written evidence on a pupil’s behaviour can be linked to Foucault’s theories of surveillance and disciplinary techniques. The LA controls schools through the implementation of SEND policies and procedures, such as those underpinning the EHC assessment process. This process enforces self-observation of how financial and behaviour management within the school has helped meet the needs of pupils. This ‘evidence’ then becomes, as Hacking (Citation2007) would define it, part of the discovery and engineering of categories by the schools and their affirmation by the LA. The schools’ compilation of dossiers and reports is used to identify how a pupil’s behaviour has deviated from the pattern of expected behaviours. Responses and actions are documented to ‘prove’ how staff have tried to channel a pupil back to the expected pattern of behaviour or that this is not possible. This is required in order to move a pupil into a designated category of the EHC plan. This in turn gives a ‘rite of passage’ to use the label as a key to possible solutions such as additional funding to manage the identified unmet needs of a pupil. For example, additional funding may be used for intervention strategies provided by a teaching assistant or specialised support staff. What the EHC process does is provide a documented history of the ‘truth’ of a problematisation. However, what the findings of this study highlight are ambiguity regarding what ‘truth’ is. The ‘truths’ behind the problematisation of challenging behaviour differ between the LA and schools. Participants in each site see aspects of each other’s practice and management as the problem when trying to meet the needs of pupils.

Within both Treetop and Orchard Grove, nearly all participants commented on the problems with the EHC planning process. It is seen as slow and not meeting the needs of some special educational needs pupils who may need the additional support.

There are multiple children at our school I feel should have an EHC plan but the process of getting them is very slow. It’s just a really poor system and lets children down in my opinion. It is really disappointing. (Orchard Grove Headteacher)

It's up to the school to look at their SEND population. If there’s challenging behaviour popping out anywhere, it's because of unmet needs. It’s up to a school as a whole to look at needs and organize their resources accordingly. If you've got challenging behaviour popping out from somebody, it's like having a health and safety risk, isn't it? (LA-BSS)

There is a continued and significant difference of opinion between the LA and schools as to ‘why’ ‘how’ and ‘when’ a pupil should have an EHC plan. This clearly represents a lack of joint working to understand how challenging behaviour is problematised.

Exploring a solution to the problem

As Bacchi (Citation2012) argues, the solutions to a problem depend on what the problem is represented to be. After I had explored with participants how they identified and responded to pupils’ perceived as ‘challenging’, participants were asked what they would put in place if they had a ‘magic wand’, five main solutions were suggested ().

Table 2. Main solutions in participants’ ‘wish list’.

All school participants said an internal unit that included staff with the skills to help pupils is desirable. LA participants also believed that an internal provision in primary schools could be a possible way to help meet the needs of pupils. However, participants were still hesitant on how such provision would be developed and funded. There was the suggestion by the LA that maybe headteachers within a consortium could fund and access such a provision as they would not need to establish one in every primary school. The LA’s response is an indication of how they perceive the ‘problem’ as a responsibility of the schools to ‘solve’ within their given resources. Therefore, the solution continues to present differing problematisations – for the school, it is resources, for the LA it is the schools lack of managing the ‘problem’.

Associating ‘challenging’ behaviour to social, emotional and medical needs to attain additional funding will have limited success as a strategy when specialist support is limited. Also, the onerous administrative tasks to evidence such observations create increased pressures on school staff to categorise a pupil. Clarity and equity of the SEND process were believed by school participants to be necessary to implement it effectively. Although the LA’s Ofsted report (2018) graded the LA’s SEND services as ‘inadequate’, the LA did not see a problem on their part in the implementation of the SEND process. Analysing policy perceptions of participants from schools and the LA again demonstrates the differing problematisations of challenging behaviour which continue in their ‘wish list’ of possible ‘solutions’. With the reduction in staff combined with the additional needs of pupils falling within SEND categories, school staff believed more financial support to employ additional specialist staff would help. However, LA participants argued that there are no additional funds for such resources, and schools should manage with current resources.

The ‘wishes’ of participants in relation to meeting the needs of pupils with challenging behaviour do not conflict with past studies and government policies (DfE, Citation2015, 2016a, 2016b, Citation2017, Citation2018, Citation2019; Ofsted Citation2009, 2010, Citation2011, Citation2012; HoC Citation2018). Internal alternative provision facilitating ‘nurture’ type approaches and facilities run by skilled and trained staff is a common theme throughout government behavioural policy. Indeed, recommendations over the last decade in several government policies and reports have included within them the ‘magic wand’ wishes of this study’s research participants. However, in searching for a solution, there are a number of presuppositions and assumptions made by both school and LA participants in their construction of the ‘problem’. The consistent lack of agreement on what the problem is represented to be, is unsurprisingly, also woven into what the solutions could be.

Bacchi (Citation2012) argues that when looking to find a solution, the problem itself should be deconstructed to identify ‘what the problem is represented to be’ (WPR). What Bacchi’s WPR approach allows us to do as practitioners are to question the assumptions we make in the framing of problems. Analysing the data from this case study, and addressing Bacchi’s questions in , has provided insight into how schools and the LA framed challenging behaviour. If schools and local authorities worked together to deconstruct how challenging behaviour is problematised, it would provide a greater insight into alternative solutions.

Table 3. Snapshot application of Bacchi’s (Citation2012) WPR questions.

Conclusion

This study has drawn on Foucault’s concepts and ideas to explore how discursive frameworks are used to mobilised establish ‘truths’. Foucault’s works are brought alive by utilising the works of contemporary scholars such as Hacking (Citation2007), Graham (Citation2011) and Bacchi (Citation2012). A study that explores the problematisations of a phenomenon such as ‘challenging’ behaviour ‘offers researchers the possibility of getting inside thinking – including one’s own thinking – observing how ‘things’ come to be’ (Bacchi Citation2012, 7). When there are two competing representations of the ‘problem’ of challenging behaviour, the possible ‘solutions’ are unlikely to address both constructions. Schools believe they have a small number of pupils presenting with high-level challenging behaviour that has become problematic and consequently both schools are unable to meet their needs. The LA believe schools are not managing low-level behaviour effectively enough to prevent escalation to a high-level. The SEND Code of Practice has become the dominating discourse that channels ‘solutions’ through the EHC process. At the centre of the problematisation of managing resources is the EHC assessment and planning process. As soon as a pupil is perceived to meet the SEND criteria, they have an additional resource available to them. How a pupil’s needs are supported becomes the issue between the schools and LA. However, the evident lack of professionals working together results in an absence of joint understanding and agreement on pupils’ needs. This in turn blocks access to redistribution of resources or agreement on additional funds or external resources. This has resulted in the EHC assessment and planning process becoming the problem rather than the solution that is intended.

The LA solution is for schools to manage both behaviour and resources more effectively before accessing the EHC process. They focus on the responsibility of schools to meet pupils’ needs rather than identifying the ‘cause’. Both schools focus on how to ‘fix’ the pupil and the need for additional funding. They also see a solution in the allocation of support services based on need, not the current equal distribution between schools. The solutions within the implementation of policies and procedures both within schools and the LA, such as the SEND Code of Practice and internal behaviour policies, appear to amplify at the same time as camouflage what is left unproblematic. Solutions such as medicalisation of pupils may be functional; however, both schools and the LA fail to deconstruct the initial problem and establish a firmer understanding of how they have framed the ‘problem’ or question the assumptions made by all parties.

For practitioners and researchers, it is often easier and more convenient to look for a solution rather than explore problems. However, a plethora of solutions in relation to tackling ‘challenging’ behaviour have formed part of government policies for many decades – yet still, the ‘problem’ persists in schools. Such ‘solutions’ have become interwoven with the ‘problem’. This study provides insight into how previous and current ‘solutions’ are not in place, such as access to specialist internal units. Also, ‘solutions’ that are not effectively implemented, such as joint working between stakeholders to ensure both the characterising and meeting of pupils needs. This study has shown that ‘solutions’ are unlikely to resolve the ‘problem’ of challenging behaviour in the context of this case study, due to the differing and conflicting construction of the ‘problem’ amongst schools and the LA. The nature of problems and how to solve them differs depending on whose ‘truth’ is heard.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Alvesson, M. 2011. Interpreting Interviews. Sage Publications Ltd. [Online]. Accessed September 24, 2019. doi:10.4135/9781446268353.

- Bacchi, C. 2012. “Why Study Problematizations? Making Politics Visible.” Open Journal of Political Science 2 (1): 1–8. [Online April] in SciRes. Accessed October 2018. http://www.SciRP.org/journal/ojps.

- Bacchi, C., and J. Bonham. 2014. “Reclaiming Discursive Practices as an Analytic Focus: Political Implications.” Foucault Studies 17: 173–192. Special Edition: Foucault and Deleuze. doi:10.22439/fs.v0i17.4298.

- Ball, S. 1993. “What is Policy? Texts, Trajectories and Toolboxes.” Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education 13 (2): 10–17. doi:10.1080/0159630930130203. Accessed July 2018.

- Ball, S. J. 2003. “The Teacher's Soul and the Terrors of Performativity.” Journal of Education Policy 18 (2): 215–228. DOI: 10.1080/0268093022000043065.

- Bennett, T. 2017. “Creating a Culture – How School Leaders Can Optimise Behaviour.” Independent Review. Department of Education 24, March 2017. Ref: DFE-00059-2017.

- Braun, A., S. Ball, and M. Maguire. 2011. “Policy Enactments in Schools Introduction: Towards a Toolbox for Theory and Research.” Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education 32 (4): 581–583. doi: 10.1080/01596306.2011.601554.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3: 77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- British Educational Research Association. 2018. Ethical Guidelines for Educational Research (4th edition). https://www.bera.ac.uk/researchers/publications/ethical-guidelines-for-educational-resaearch-2018 (Accessed February 2020).

- Brown, C., and S. Carr. 2019. “Education Policy and Mental Weakness: A Response to a Mental Health Crisis.” Journal of Education Policy 34 (2): 242–266. doi: 10.1080/02680939.2018.1445293.

- Casimiro, L. A. 2016. “The Theory of Enactment by Stephen Ball: And What if the Notion of Discourse Was Different?” Education Policy Analysis Archives 24: 1–19. Accessed October 2018. Arizona State University.

- Childerhouse, H. (2017) ‘Supporting Children with ‘Social, Emotional and Behavioural Difficulty (SEBD)’ in Mainstream: Teachers’ Perspectives. A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements of Sheffield Hallam University for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. [Online]. Accessed May 2019. http://shura.shu.ac.uk

- Cole, T., and B. Knowles. 2011. How to Help Children and Young People with Complex Behavioural Difficulties: A Guide for Practitioners in Educational Settings. London and Philadelphia: Jessica Kingsley.

- Cooke, M. L. 1994. “Method as Ruse: Foucault and Research Method.” Mid-American Review of Sociology 18 (1/2): 47–65. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23253062.

- Cooper, P. 1999. Understanding and Supporting Children with Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties, edited by P. Cooper, Jessica Kindsley Publishers.

- Department for Education. 2016a. Behaviour and Discipline in Schools: Advice for Head Teachers and School Staff. London: Department for Education.

- Department for Education. 2016b. Mental Health and Behaviour in Schools. London: Department for Education.

- Department for Education. 2017. Exclusion from Maintained Schools, Academies and Pupil Referral Units in England: Statutory Guidance for Those with Legal Responsibilities in Relation to Exclusion. London: Department for Education.

- Department for Education. 2018. Permanent and Fixed Period Exclusions in England. 2016–17, National Statistics. London: Department for Education.

- Department for Education. 2019. Support for Pupils with Special Educational Needs and Disabilities in England. HC 2636 SESSION 2017–2019. September 11, 2019

- Department of Education. 2012. Teaching Standards: Guidance for School Leaders, School Staff and Governing Bodies. Ref: DFE-00066-2011

- Department of Education and Department of Health. 2015. Special Educational Needs and Disability Code of Practice: 0-25 Years. Ref: DFE-00205-2013.

- Dix, P. 2017. When the Adults Change Everything Changes. Independent Thinking Press.

- Emerson, E. 2001. Challenging Behaviour: Analysis and Intervention in People with Severe Intellectual Disabilities. 2nd ed. Cambridge University Pres. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511543739.

- Foucault, M. 1972. The Archaeology of Knowledge. Translated by A.M. Sheridan Smith. New York: Pantheon Books.

- Foucault, M. 1977. Discipline and Punishment: The Birth of Prisons. New York: Penguin Books.

- Foucault, M. ed. 1984. The Foucault Reader. London: Penguin Books (Rabinow, P.).

- Freie, C., and K. Eppley. 2014. “Putting Foucault to Work: Understanding Power in a Rural School.” Peabody Journal of Education 89 (5): 652–669. doi: 10.1080/0161956X.2014.958908 (Online November 2018).

- Graham, L. 2005a. “Schooling and ‘Disorderly’ Objects: Doing Discourse Analysis Using Foucault.” Queensland University of Technology. Paper presented at Australian Association for Research in Education 2005 Annual Conference, Sydney, 27th November–1st December. Accessed October 2018. https://eprints.qut.edu.au.

- Graham, L. 2005b. “Discourse Analysis and the Critical use of Foucault.” Queensland University of Technology. Paper presented at Australian Association for Research in Education 2005 Annual Conference, Sydney, 27th November–1st December. Accessed October 2018. https://eprints.qut.edu.au.

- Graham, L. 2011. “The Product of Text and ‘Other’ Statements: Dis- Course Analysis and the Critical Use of Foucault.” Educational Philosophy and Theory 43 (6): 663–674.

- Hacking, I. 2007. “Kinds of People: Moving Targets.” Proceedings of the British Academy 151: 285–318.

- House of Commons. 2018. Alternative Provision: Education in England. HoC Briefing Paper. No 08522, March 12.

- Macleod, G. 2006. “Bad, mad or sad: Constructions of Young People in Trouble and Implications for Interventions.” Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties 11 (3): 155–167.

- MacLure, M., L. Jones, R. Holmes, and C. MacRae. 2012. “Becoming a Problem: Behaviour and Reputation in the Early Years Classroom.” British Educational Research Journal 38 (3): 447–471.

- Maguire, M., S. Ball, and A. Braun. 2010. “Behaviour, Classroom Management and Student Control: Enacting Policy in English Secondary School.” International Studies in Sociology of Education 20 (2): 153–170. doi:10.1080/09620214.2010.503066. Accessed November 1, 2017.

- McClusky, G., S. Riddell, E. Weedon, and M. Fordyce. 2016. “Exclusion from School and Recognition of Difference.” Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education 37 (4): 529–539. doi: 10.1080/01596306.2015.1073015.

- Menzies, L., and S. Baars. 2015. The Alternative Should Not Be Inferior – What Now for ‘Pushed Out’ Learners? London: Inclusion Trust.

- Ofsted. 2010. Inspecting Behaviour. (Ref No 090192) p4.

- Ofsted. 2011. Supporting Children with Challenging Behaviour Through a Nurture Group Approach. (Ref no: 100230).

- Ofsted. 2012. Additional Provision to Manage Behaviour and the Use of Exclusion. (Ref No: 1200180).

- Raaper, R. 2016. Discourse Analysis of Assessment Policies in Education: A Foucauldian Approach. Sage Research Method Cases. Sage Publications. 2017. doi:10.4135/9781473975019.

- Skipp, A., and V. Hopwood. 2016. Mapping User Experience of the Education, Health and Care Process: A Qualitative Study. Department of Education – Research Report, April.

- Wright, A. 2009. “Every Child Matters: Discourses of Challenging Behaviour.” Pastoral Care in Education 27 (4): 279–290. doi: 10.1080/02643940903349344. Accessed July 1, 2017.

- Yin, R. K. 2003. Case Study Research: Design and Methods. 3rd ed. London: Sage Publications.