Abstract

Uncontrolled hypertension is associated with an increased risk of adverse clinical vascular outcomes and death. Hypertension management guidelines from China and the USA recommend initiation of antihypertensive pharmacotherapy with a single drug for patients without severe hypertension at presentation. Current European hypertension guidelines take a different approach and recommend the use of combination therapy from the time of diagnosis of hypertension for most patients. This article reviews the burden of hypertension in these countries and summarises the evidence base for the use of antihypertensive combination therapy contained within a single tablet (single-pill combinations, SPC). Typically, half or less of populations from China, Europe and the USA who were found to have hypertension were aware of their condition, less than half of those receiving treatment, and fewer still achieved adequate blood pressure (BP) control. The reasons for the unaddressed burden of hypertension are complex and multifactorial, with contributions from factors related to patients, healthcare providers and healthcare systems. The use of SPCs of antihypertensive therapies helps to optimise adherence with therapy and is likely to result in superior BP control. There is a strong evidence base to support current European guideline recommendations on the initiation of antihypertensive therapy with SPCs for the majority of people with hypertension.

Introduction

Arterial hypertension is an early manifestation of cardiovascular disease that is associated strongly with adverse long-term clinical outcomes such as myocardial infarction (MI), stroke, heart failure (HF) and renal dysfunctionCitation1. The management of hypertension is based on controlling blood pressure (BP) to <140/90 mmHg, or lower in patients who are already at elevated cardiovascular risk through the presence of concomitant conditions such as atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) or diabetes. Recent iterations of the European guidelines for the management of hypertension and reduction of cardiovascular risk have increasingly stressed the importance of establishing control of BP promptlyCitation2,Citation3. It is well known that adding a second antihypertensive agent to an insufficiently effective monotherapy is more effective in lowering BP and achieving BP goals than maintaining or titrating the dose of the monotherapyCitation4–9. Box 1 lists the abbreviations for the main classes of antihyperteneive agents used in this review.

Box 1 Abbreviations for antihypertensive drug classes used in this article.

ACEI: Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor

ARB: Angiotensin II receptor blocker

BB: β-blocker

CCB: Calcium channel blocker

This narrative literature review, based on a structured literature search (see below), considers the evidence base for the use of single-pill combinations (SPCs) of antihypertensive agents in the management of hypertension, in terms of their antihypertensive efficacy and impact on adherence to therapy. Our perspective includes consideration of the current burden of hypertension in China, Europe and the USA, and the benefits and limitations of SPCs in the management of hypertension.

Why do we need to improve the effectiveness of antihypertensive therapy?

Global burden of hypertension

A global survey of hypertension and its treatment, that included data from a total of 104 million subjects enrolled in 1204 individual studies found that for the year 2019 less than half of people with hypertension received treatment for the condition, and that hypertension was controlled adequately in just 23% (credible interval 20–27%) of women and 18% (16–21%) of men with hypertensionCitation10. The World Health Organization reported that, globally, 42% of adults with hypertension receive a diagnosis, and only half of these patients receive treatmentCitation1. Comparable recent (2017–2021) data are available from other countries, including IrelandCitation11, KoreaCitation12, UKCitation13, EgyptCitation14, and Guinea-BissauCitation15.

Hypertension in China

Data from the China Hypertension Survey, from 2015 to 1019 and based on a nationally-representative sample of 451,755 adults, found that the age-standardised prevalence of hypertension (defined as BP >140/90) was 23.2%; an additional 41.3% had pre-hypertension (defined as BP 120–139/80–89 mm Hg)Citation16. Less than half (46%) of people with hypertension were aware of the condition. Among people receiving treatment for hypertension, BP control was achieved in 37.5% (15.3% for the overall population). An additional estimate of the burden of hypertension in China came from the population-based “China Patient-Centered Evaluative Assessment of Cardiac Events (PEACE) Million Persons Project”, which surveyed BP in 1,738,886 residents of all parts of mainland China between 2014 and 2017Citation17. A higher age-standardised prevalence of hypertension was observed in this study (37.2%). Again, less than half were aware of their hypertension (36.0%), with low proportions receiving treatment (22.9%) and achieving BP control (only 5.7% overall). About four-fifths of patients (81.5%) with uncontrolled BP despite antihypertensive treatment were receiving antihypertensive monotherapy.

Hypertension in Europe

A real-world study from Italy published in 2020 showed that the use of antihypertensive monotherapy was common and that only 14% of these patients achieved the BP targets proposed in the 2018 European guideline for the management of hypertensionCitation18. The use of dual-agent combination therapy only increased this proportion to 18%. A survey from Bahrain found that older patients were more likely to receive antihypertensive combination therapies supported by guidelines (77% vs. 69%, respectively, p < .0001), but were less likely than younger patients to receive a SPC (45% vs. 63%, p < .0001)Citation19. Data from BENELUX countries showed that only 45% of patients receiving 2 antihypertensive agents in general practice achieved their BP target, despite 61% receiving an SPC, with or without additional agentsCitation20. Only 32% of patients in Poland who were receiving two antihypertensive therapies were receiving an SPC in 2018, according to a registry study conducted thereCitation21. Similar data are available from ItalyCitation22.

Hypertension in the USA

In the USA, the nationally representative National Health and Nutrition Survey 2015–2018 cohort reported that hypertension was controlled to local targets there in only 22% of women and 18% of menCitation23, and a survey of 6546 people with hypertension in 10 countries found that 48% were treated and 39% were controlledCitation24.

Importance of adherence for improving outcomes in people with hypertension

Adherence and outcomes

Effective control of BP, using pharmacologic antihypertensive therapies for the majority of patients with hypertension, holds the key to improving outcomes in hypertension, as described aboveCitation2,Citation3. It is reasonable to assume that a drug treatment will not be effective if a patient does not take it regularly, and yet less than half of patients with hypertension are reported as being adherent to antihypertensive therapy at one year following its prescriptionCitation25. A meta-analysis that included data from 27 million subjects in 161 studies reported a prevalence of non-adherence to antihypertensive therapy that lay between 27% and 40%, depending on how it was measuredCitation26. Worryingly, this situation showed no sign of improvement between 2010 and 2020. Almost half (48%) of patients in Asian countries were non-adherent to antihypertensive therapy, according to a recent meta-analysisCitation27. Other reports, including some of those cited above, confirm that poor medication adherence is more common in lower vs. higher income countries, and in non-western vs. western countriesCitation25–27.

Reliance on indirect measures of adherence is a limitation of most studies in this area and measurement of serum levels of antihypertensive agents, or of their urinary metabolites, provides a more quantitative approach. One such study measured the levels of 23 antihypertensive agents in serum of patients participating in a national study in NorwayCitation28. The proportion with confirmed non-adherence was relatively low compared with the other studies cited here (7.3%). Interestingly, the number of subjects who self-reported non-adherence (53) was lower than the number identified using serum drug concentrations (69). A study from the UK that used measurement of metabolites of antihypertensive agents in urine as a reliable and quantitative measure of adherence, found that 25% of patients were partially or totally non-adherent to their antihypertensive medicationCitation29.

The study from Norway, described above, showed that sub-optimal adherence was associated with higher diastolic blood pressure (DBP)Citation28. In other studies, sub-optimal adherence to antihypertensive has been associated with uncontrolled hypertension, hypertensive crises, increased risk of a broad range of microvascular and macrovascular outcomes, cognitive decline, increased healthcare use (including emergency care), and increased healthcare costs (reviewed elsewhereCitation25). As an example, study from a US health insurance database found that the risk of cardiovascular events increased in subjects who were non-adherent to antihypertensive medication (hazard ratio [HR] 1.58 (95% 1.45–1.71)Citation30. Moreover, with the highest quartile of adherence as reference (quartile 1), there was an apparently linear relationship between the increasing risk of adverse cardiovascular outcome and increasing quartiles of non-adherence (HRs 1.23 [1.10–1.38] for quartile 2. 1.68 [1.51–1.88] for quartile 3, and 2.15 [1.93–2.40] for quartile 4).

The problem of sub-optimal adherence to antihypertensive therapy is global and multifactorial and related to behaviours and beliefs and cultural backgrounds of patients and healthcare providers, and barriers inherent in healthcare systemsCitation31. The delivery of antihypertensive treatment is an important factor within this phenomenon. Patients with hypertension are often older with multiple comorbidities that result in a high likelihood of polypharmacy and complex therapeutic regimensCitation25,Citation32. The adherence to a regimen tends to decrease as its complexity increasesCitation25,Citation31,Citation33,Citation34. The following sections summarise the evidence base for the use of SPCs as one approach to simplifying the management of people with hypertension and improving their treatment outcomes.

Clinical utility of single-pill combinations

Efficacy

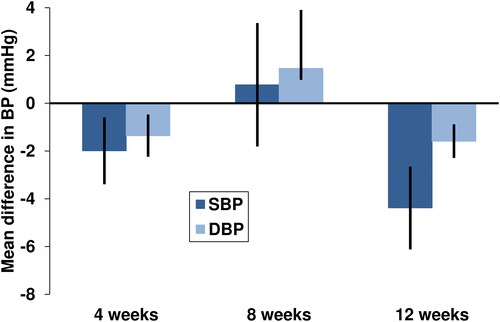

A recent (2021) and comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis compared the effects of SPCs on BP compared with the corresponding free combinations from 20 trials that provided these dataCitation35. Nine studies involved treatment with the free combination followed by a switch to the SPC at baseline. All of these trials reported improvements in systolic BP (SBP) after switching to the SPC, with 6 demonstrating a statistically significant effect, and a further 3 not providing statistical evaluation. Statistically significant or numerical reductions in diastolic BP (DBP) were seen in 7/8 of these studies. In addition, statistically significantly or robustly numerically larger proportions of patients achieved BP targets after switching from the free combination to the SPC. For the remaining 11 studies, changes in BP were statistically comparable for 8 studies, with a further 3 studies demonstrating a significant or numerical reduction in SBP for the SPC vs. the free combination. Meta-analysis showed that the effect on BP of the SPC and free combination diverged over time, with larger and statistically significant differences in favour of the SPC appearing at longer treatment durations ().

Figure 1. Mean differences changes in blood pressure over time in patients with hypertension receiving a single-pill combination vs. a free combination of the same treatments from a meta-analysis. Data shown are mean treatment differences for SPC vs. free combination from a fixed effects model meta-analysis; bars are 95%CI. Negative treatment differences favour the single pill combination (SPC). Drawn from data presented in referenceCitation34.

A further meta-analysis (2020, 11 studies) took a different approach, of excluding randomised, controlled trials (RCTs)Citation36. The rationale for this methodology was that the tightly monitored environment of a RCT would likely influence patient behaviour and confound attempts to measure differences in treatment outcomes that depend on patient behaviours such as adherence or persistence; excluding RCTs would therefore provide an analysis that would be better aligned with routine clinical practice. Patients receiving free combinations were significantly less likely to achieve their blood pressure goal compared with patients receiving a SPC (odds ratio [OR] 0.77 [95%CI: 0.69 to 0.85], p < .001). Moreover, SPC vs. free combination resulted in fewer hospital visits for any cause (OR 0.79 [95%CI 0.67 to 0.94], p = .009), and fewer emergency visits for any cause (OR 0.75 [95%CI 0.65 to 0.87], p = .001) or for a cause related to hypertension (OR 0.65 [95%CI 0.54 to 0.80], p < .001).

Tolerability

Side-effects with antihypertensive therapies tend to be dose-related and the additive effects of the individual components of a combination treatment mean that substantial BP reductions can be obtained at lower doses than monotherapy. Peripheral oedema with higher doses of amlodipine provides one such example. A randomised trial compared different strengths of a 3-agent low-dose SPC (CCB-ARB-thiazide, each given at between one quarter and half their usual minimum dose as monotherapy) or to ARB or CCB monotherapy (amlodipine 5 mg or 10 mg) for 8 weeksCitation37. Mean SBP reductions were similar with the low-dose combinations (between −14.9 mmHg and −19.5 mmHg) and amlodipine 10 mg monotherapy. Peripheral oedema (a common side-effect of amlodipine, measured here as ankle circumference) occurred during treatment with amlodipine, but not with the low-dose combinations. Similarly, the TEAMSTA-5 study involved randomisation of people with hypertension uncontrolled on amlodipine to telmisartan-amlodipine combinations (40/5 mg or 80/5 mg), or to monotherapy with amlodipine 5 mg or 10 mgCitation38. Mean reductions in SBP with the combinations were −13.6 mmHg and −16.0 mmHg, respectively, compared with −6.2 mmHg for amlodipine 5 mg (significantly lower than the reduction with either combination tablet) and −11.1 with amlodipine 10 mg (significantly lower than the reduction with the 80/5 mg combination tablet). The incidence of oedema for the pooled combination therapy groups was 4.3%, compared with 8.6% for amlodipine 5 mg and 27.2% for amlodipine 10 mg. A further study randomised patients with hypertension to an SPC containing amlodipine-ramipril 2.5/2.5 mg or amlodipine 2.5 mg, with BP-directed titration towards maximum doses of 10/10 mg or 10 mg. respectivelyCitation39. Changes in mean ambulatory SBP and DBP, and in office SBP, were larger for the SPC vs. monotherapy, but the SPC was associated with a significantly lower (p = .011) incidence of peripheral oedema (7.6% vs. 18.7%, respectively)Citation39. Not all randomised comparisons of low-dose amlodipine-containing combination treatments with titrated amlodipine have demonstrated such a benefit, howeverCitation40–42. Conversely, in principle, the cause of adverse drug reactions will be more difficult to locate and eliminate when more than one treatment is started at the same time, with the SPC approach preventing withdrawal of a single agent to see if the symptoms disappear.

Adherence/persistence

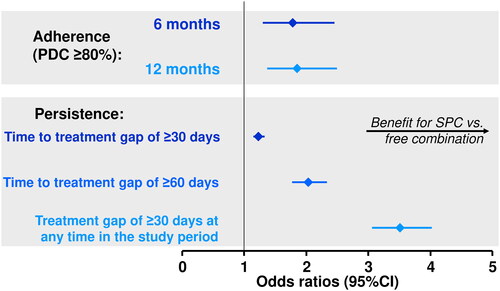

A 2021 systematic review and meta-analysis described above also considered adherence (the proportion of doses of medicine taken as directed by the physician, usually measured as proportion of days covered [PDC] or medication possession ratio [MPR]) and persistence (time to discontinuation of the medication)Citation35. Nineteen of 23 studies that measured adherence found a significant or substantial numerical benefit for the SPC vs. the free combination, with 3 studies reporting similar adherence and 1 study reporting a benefit for the free combination (). Data for persistence were comparable, with clear benefit for the SPC (). This analysis confirmed and extended the results of a previous meta-analysis, where adherence and/or persistence were also generally higher for SPCs vs. free combinationsCitation43.

Table 1. Adherence and persistence with antihypertensive therapy with 2-agent single pill combinations (SPC) vs. the corresponding free combination (FC) from a systematic review and meta-analysis.

Another recent meta-analysis of non-randomised trials (see above) evaluated the impact of SPC vs. free combinations of antihypertensive agents on the likelihood of achieving good adherence with therapy, using the common definitions for this outcome of PDC ≥80% or MPR ≥80%Citation36. Persistence was measured as the likelihood of a gap in treatment of at least 6 months. Prescription of SPC vs. a free combination approximately doubled the odds of both good adherence and good persistence with therapy (). Earlier meta-analyses reported an increase in medication adherence for SPC vs. free combination of 15% (2018, 9 studies)Citation44, 14% in patients previously treated with antihypertensive agentsCitation45, 21% (2010, 15 studies)Citation46, or 24% (2007, 9 studies)Citation47. These analyses also usually reported improved persistence with the SPC.

Figure 2. Odds of achieving good adherence and persistence with antihypertensive therapy for treatment with a single-pill combination (SPC) vs. free combination of antihypertensive agents from a meta-analysis. Data for adherence show odds ratios of achieving proportion of days covered (PDC) or medication possession ratio (MPR) ≥80% for SPC vs. free combination. Data for persistence = hazard ratios for time to a treatment gap of at least 30 or 60 days for SPC vs. free combination, or for an answer of “yes” to the question “was there a 30 day treatment gap at any time during the study?”. Drawn from data presented in referenceCitation35.

A randomised trial enrolled 145 patients with hypertension whose BP was sub-optimally controlled by 2 antihypertensive agents and randomised them to either a 3-component SPC (CCB-ARB-thiazide) or to a free combination of ARB-thiazide SPC + the CCB given separately (all dosages were equivalent) for 3 monthsCitation48. Modest but significant (p = .04) benefits were seen for the SPC vs. the two tablet combination for the proportion of days on which medication was taken (median 95 vs. 92 days) and the proportion of days on which medication was taken correctly (91 vs. 89 days).

Real world analyses have also demonstrated improved adhere and/or persistence with SPC vs. free combinations in populations with hypertension. About one-seventh (15%) of a population of 63,448 new users of antihypertensive therapy in Italy was started on an SPC in one studyCitation22. These individuals had a higher likelihood of high adherence (risk ratio 1.18 [1.16–1.21]) and a lower risk of low adherence (risk ratio 0.42 [0.39–0.45]), compared with those receiving initial monotherapy. A nationwide study in Korea that enrolled 116,667 users of a CCB and ARB found a modest but significantly (p < .01) higher adherence (MPR) in those taking these medicines as an SPC vs. a free combination (89.7 [95%CI 89.3–90.0] and 87.2 [95%CI 86.7–87.7], respectively)Citation49. A database study from Japan found that adherence was higher with SPC vs. free combination during a 12-month follow-up periodCitation50, Other studies from Japan found that switching from a free combination to an SPC for delivering CCB + ARB therapy improved adherence significantlyCitation51 and that adherence was higher for SPCs of CCB + ARB vs. the corresponding free combination, but not for other comparisons of SPCs with free combinationsCitation34. Finally, a study from the database of a large pharmacy claims manager in the USA demonstrated that adherence and persistence to thiazide-based antihypertensive therapy were lower when the diuretic was given as monotherapy compared with SPCs that also included a BB, ARB or ACEI (HRs 0.40–0.50 for adherence and HRs 0.37–38, each for monotherapy vs. SPC)Citation52.

Uncontrolled, real-world evaluations of SPCs in populations with persistence have reported high levels of good adherence, for example, 86%Citation53, 97%Citation54 or 98%Citation55 with a CCB-ACEI combination at 4 months in Greece, 89% with CCB-ARB in IndonesiaCitation56, 94% on renin inhibitor-CCB over 3 months in AustriaCitation57, 99% with thiazide-CCB over 7 weeks in IndiaCitation58, 66–100% with CCB-ARB or CCB-ARB-thiazide over 6 months in PakistanCitation59, 97% with CCB-ARB over 6 months in TurkeyCitation60, 99% with CCB-BB in 6 Eastern European countriesCitation61.

Healthcare costs

A meta-analysis calculated an average reduction in total and hypertension-related annual per person healthcare costs of USD −2039 and USD −1357, respectively, when SPC was used rather than a free combinationCitation45. An observational study from Japan reported that switching from a free combination of a CCB + ARB to the corresponding SPC reduced the cost of medications by 31%Citation50. Routine administration of an ACEI/thiazide SPC reduced treatment and hospital cost, and was cost effective for reducing mortality, in a health economic analysis based on the Action in Diabetes and Vascular Disease: Preterax and Diamicron-MR Controlled Evaluation (ADVANCE) trial in patients with type 2 diabetes and hypertensionCitation62. It is important to remember, however, that the structure of the local healthcare system is the prime determinant of healthcare costs. The expectation that the use of SPCs for antihypertensive therapy will reduce treatment costs may not be met in all locations.

What do the guidelines say?

summarises key current guidance on the initiation of antihypertensive pharmacotherapy and the use of combination antihypertensive therapy in current guidelines from China, Europe and the USA, as well as global guidelines from the International Society for Hypertension (ISH) and the World Health Organization (WHO)Citation2,Citation3,Citation63–67. It should be noted that this article focuses on the use of antihypertensive pharmacotherapy, and all guidelines stress the importance of improvements in lifestyle (diet and physical activity) to improve BP control and to reduce cardiovascular risk in people with hypertension.

Table 2. Overview of key recommendations for the initiation of pharmacologic management of hypertension in guidelines from China, Europe and the USA and from selected global guidelines.

The most recent guideline for the management of hypertension from China dates from 2018Citation63, with a separate but complementary guideline published in the following yearCitation64. Any of the five main classes of antihypertensive agents (ACEI, ARBs, CCB, diuretics, BBs) may be used to initiate pharmacologic antihypertensive therapy, with the individual patient presentation driving the choice of initial treatment. Combination therapy is generally reserved for more severe hypertension, although low-dose antihypertensive therapy can be considered at any level of severity of hypertension. These guidelines are about to be updated and the optimal combination therapy recommended in clinical practice in China are CCB + ARB, CCB + ACEI, ARB + thiazide, ACEI + thiazide, CCB + thiazide, and CCB + BB (CCBs are dihydropiridine in each case). USCitation65 and EuropeanCitation2,Citation3 guidelines are broadly similar, but for the exclusion of BB from initiation of therapy in the absence of compelling indications, such as stable ischaemic heart disease or stable congestive heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. The US guideline also takes a similar approach to the 2018 guideline from China on the use of drug combinations to initiate antihypertensive therapy, although the guideline from China lists the SPCs available there.

The current (2021Citation2,Citation3) European guidelines for the management of hypertension take a radically different approach to the use of combination therapy. This guidance anticipates that most people with hypertension will require more than one antihypertensive agent to control their BP, and that most of these patients, i.e. all with hypertension except those with grade 1 hypertension (BP 140–149/90–99 mmHg) without additional cardiovascular risk factors, should receive a combination of two antihypertensive therapies from the time of diagnosis of hypertension. It is recommended further that SPC should be used for this purpose from the time of diagnosis of hypertension, where possible, to limit the potential for polypharmacy and to support good compliance and adherence to therapy.

The recent (2020) global guideline from the ISH also provides strong support for initial use of combination therapy, for all except patients with low-risk stage 1 hypertension or for very elderly or frail patientsCitation66. SPCs are preferred to free combinations, as in the European guideline. Recent (2021) guidance from the WHO supports the use of SPCs where combination therapy is prescribed, though the use of combination therapy for all patients from diagnosis is not supported hereCitation67.

Perspectives on the role of SPCs in the management of hypertension

The majority of clinical evidence reviewed above supports the European guideline recommendations for initiating antihypertensive therapy with an SPC (in most cases), as multiple studies and meta-analyses have confirmed that this approach is likely to deliver superior antihypertensive efficacy and higher levels of adherence/persistence with therapy, compared with administration of a free combination. Numerous combinations of different antihypertensive agents are available, which brings flexibility to prescribing, e.g. for a patient with ischaemic heart disease or HF (who requires treatment with a combination regimen that contains a BB), or for a patient with chronic kidney disease (who requires ACEI-CCB or ARB-CCB therapy)Citation2,Citation3. Inability to titrate individual components of the regimen separately has often been cited as a limitation of the SPC approach. However, the range of tablet strengths available for most SPCs usually supports a switch between tablets where the dose of only one component is increased. In theory, treatments taken at different times of the day would be unsuitable for inclusion within an SPC, although guidelines give strong support to the use of once-daily antihypertensive agents that provide 24-h BP controlCitation2,Citation3.

Some knowledge gaps remain. Not all individual studies have demonstrated improvements in BP, adherence and persistence with SPC vs. free combinations, however, especially in populations where adherence was already highCitation68,Citation69. Also, while there appears to be a clear relationship between sub-optimal adherence and adverse clinical outcomes in people with hypertension, no clinical trial has yet demonstrated added benefit in this regard from prescribing an SPC rather than a free combination. However, it is known that even relatively modest reductions in BP are likely to confer significant outcomes benefits, as it has been shown that a reduction in SBP of 5 mmHg reduces the risk of a major cardiovascular event by about 10%, irrespective of the starting level of BP, or the presence or absence of cardiovascular diseaseCitation70.

A study that used administrative claims data to review a total of 459,465 prescriptions for accuracy and safety provides a further note of caution relating to the use of SPCsCitation71. Duplication of an existing prescription was uncommon when prescribing combination therapy, and occurred with only 0.8% of prescriptions. Nevertheless, the risk of duplication was doubled when an SPC was used, compared with a free combination (adjusted relative risk [RR] 2.24 [95%CI 1.77–2.83], p < .001, from propensity score-matched cohorts). “Potentially serious” drug-drug interactions were more common when applying combination therapy (10.6% of cases). A small but statistically significant excess of these drug interactions occurred in the SPC vs. free combination group (adjusted RR 1.07 [95%CI 1.01–1.13], p = .030]). The impact (and direction of effect) of a switch to SPC-based antihypertensive therapy may also differ between healthcare systems, as described above.

Therapeutic inertia – the failure to titrate or add to an insufficiently effective regimen – is an important cause of sub-optimal treatment outcomes in hypertension as in other conditions. Interestingly, one study found that prescription of a SPC increased clinical inertia in a population with hypertension, although 6-month BP outcomes were still superior to those attained with usual careCitation72. The use of SPCs early in the course of hypertension does not absolve physicians from the need to monitor their patients and intensify therapy when necessary.

We have used the burden of hypertension in three major regions – Europe, the USA and China – to demonstrate the need for improved management of this condition, including greater use of antihypertensive SPCs. Nevertheless, hypertension is a global problem and affects countries outside this selectionCitation73. For example, clinical inertia and sub-optimal adherence is an important contributor to poor hypertension control in sub-Saharan AfricaCitation74,Citation75 and Latin AmericaCitation76,Citation77. This is a limitation of our approach, although the principles of improving management by simplifying therapy would apply to other regions.

Conclusions

The use of SPCs of antihypertensive therapies helps to optimise adherence with therapy and is likely to result in superior BP control compared with treatments such as free combinations of antihypertensive agents. There is a strong evidence base to support current European guideline recommendations on the initiation of antihypertensive therapy with SPCs for the majority of people with hypertension.

Supporting information

Search strategy

This narrative review is based on two PubMed searches:

hypertension AND ("fixed dose" OR "fixed-dose" OR "single-tablet" OR "single-pill" OR "single pill"), limited to Abstract, English, randomised, controlled trial

hypertension AND (adherence OR persistence OR compliance) AND ("combination treatment" OR "fixed dose" OR "fixed-dose" OR "single-tablet" OR "single-pill" OR "single tablet" OR "single pill"), limited to Clinical Trial, Meta-Analysis, Observational Study, Randomized Controlled Trial

Search hits were reviewed manually to identify relevant references. For the first search, preference was given to meta-analyses, given the large number of individual trials in this area. For the second (relating to adherence to therapy), observational and database studies were also considered as evaluations of treatment adherence are often based on real world analyses. Reference lists of identified articles and authors’ reference collections also served as sources of material. The primary focus of the review was to compare the effects of SPCs and free combinations of antihypertensive efficacy and adherence/persistence; for reasons of space, this review does not seek to compare the efficacy of individual SPCs. Abbreviations for antihypertensive drug classes are given in Box 1, and not spelled out in the text, for conciseness and clarity.

Transparency

Ethics statement

This review article is based on previously conducted studies and the clinical expertise of the authors. No new clinical studies were performed by the authors and no patients were involved in the production of this article, beyond their involvement in the previously published studies we cite. Accordingly, no ethical approval is required for this article.

Acknowledgements

A medical writer (Dr Mike Gwilt, GT Communications) provided editorial assistance, funded by Merck Healthcare KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

UG-H is an employee of Merck Healthcare KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany. NS declared that she had no duality of interest. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed. Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no other relevant financial relationships or otherwise to disclose.

Author contributions

Prof. Sun and Dr Gottwald-Hostalek contributed equally to the development of this article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- World health Organization. Hypertension. [cited November 2022]. Available from https://www.who.int/health-topics/hypertension.

- Williams B, Mancia G, Spiering W, et al. 2018 Practice guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension and the European Society of Cardiology: ESH/ESC Task Force for the Management of Arterial Hypertension. J Hypertens. 2018;36(12):2284–2309.

- Visseren FLJ, Mach F, Smulders YM, et al. 2021 ESC guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice. Eur Heart J. 2021;42(34):3227–3337.

- Foch C, Feifel J, Gottwald-Hostalek U. An anchored simulated treatment comparison of uptitration of amlodipine compared with a low-dose combination treatment with amlodipine 5 mg/bisoprolol 5 mg for patients with hypertension suboptimally controlled by amlodipine 5 mg monotherapy. Curr Med Res Opin. 2022;38(4):587–593.

- Park CG, Ahn TH, Cho EJ, et al. Comparison of the efficacy and safety of fixed-dose S-amlodipine/telmisartan and telmisartan in hypertensive patients inadequately controlled with telmisartan: a randomized, double-blind, multicenter study. Clin Ther. 2016;38(10):2185–2194.

- Chow CK, Atkins ER, Hillis GS, et al. Initial treatment with a single pill containing quadruple combination of quarter doses of blood pressure medicines versus standard dose monotherapy in patients with hypertension (QUARTET): a phase 3, randomised, double-blind, active-controlled trial. Lancet. 2021;398(10305):1043–1052.

- White WB, Calhoun DA, Samuel R, et al. Improving blood pressure control: increase the dose of diuretic or switch to a fixed-dose angiotensin receptor blocker/diuretic? the valsartan hydrochlorothiazide diuretic for initial control and titration to achieve optimal therapeutic effect (Val-DICTATE) trial. J Clin Hypertens. 2008;10:450–458.

- Mancia G, Coca A, Chazova I, FELT investigators, et al. Effects on office and home blood pressure of the lercanidipine-enalapril combination in patients with stage 2 hypertension: a European randomized, controlled clinical trial. J Hypertens. 2014;32(8):1700–1707; discussion 1707.

- Rhee MY, Baek SH, Kim W, et al. Efficacy of fimasartan/hydrochlorothiazide combination in hypertensive patients inadequately controlled by fimasartan monotherapy. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2015;9:2847–2854.

- Risk Factor Collaboration NCD. Worldwide trends in hypertension prevalence and progress in treatment and control from 1990 to 2019: a pooled analysis of 1201 population-representative studies with 104 million participants. Lancet. 2021;398:957–980.

- Murphy CM, Kearney PM, Shelley EB, et al. Hypertension prevalence, awareness, treatment and control in the over 50s in Ireland: evidence from the Irish longitudinal study on ageing. J Public Health (Oxf). 2016;38(3):450–458.

- Kim KI, Ji E, Choi JY, et al. Ten-year trends of hypertension treatment and control rate in Korea. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):6966.

- Tapela N, Collister J, Clifton L, et al. Prevalence and determinants of hypertension control among almost 100 000 treated adults in the UK. Open Heart. 2021;8(1):e001461.

- Hassanein M. Adherence to antihypertensive fixed-dose combination among Egyptian patients presenting with essential hypertension. Egypt Heart J. 2020;72(1):10.

- Turé R, Damasceno A, Djicó M, et al. Prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension in Bissau, Western Africa. J Clin Hypertens. 2022;24(3):358–361.

- Wang Z, Chen Z, Zhang L, et al. Status of hypertension in China: results from the China hypertension survey, 2012. Circulation. 2018;137(22):2344–2356.

- Lu J, Lu Y, Wang X, et al. Prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension in China: data from 1•7 million adults in a population-based screening study (China PEACE million persons project). Lancet. 2017;390(10112):2549–2558.

- Tocci G, Presta V, Citoni B, et al. Blood pressure target achievement under monotheraphy: a real-life appraisal. High Blood Press Cardiovasc Prev. 2020;27(6):587–596.

- Al Khaja KAJ, James H, Veeramuthu S, et al. Antihypertensive prescribing pattern in older adults: implications of age and the use of dual single-pill combinations. High Blood Press Cardiovasc Prev. 2019;26(6):535–544.

- Leeman M, Dramaix M, Van Nieuwenhuyse B, et al. Cross-sectional survey evaluating blood pressure control ACHIEVEment in hypertensive patients treated with multiple anti-hypertensive agents in Belgium and Luxembourg. PLoS One. 2018;13(11):e0206510.

- Filipiak KJ, Tomaniak M, Płatek AE, et al. Negative predictors of treatment success in outpatient therapy of arterial hypertension in Poland. Results of the CONTROL NT observational registry. Kardiol Pol. 2018;76(2):353–361.

- Rea F, Savaré L, Franchi M, et al. Adherence to treatment by initial antihypertensive mono and combination therapies. Am J Hypertens. 2021;34(10):1083–1091.

- Department of Health and Human Services. Estimated hypertension prevalence, treatment, and control among U.S. adults. [cited June 2022]. Available from https://millionhearts.hhs.gov/data-reports/hypertension-prevalence.html.

- Melgarejo JD, Maestre GE, Thijs L, et al. Prevalence, treatment, and control rates of conventional and ambulatory hypertension across 10 populations in 3 continents. Hypertension. 2017;70(1):50–58.

- Burnier M, Egan BM. Adherence in hypertension. Circ Res. 2019;124(7):1124–1140.

- Lee EKP, Poon P, Yip BHK, et al. Global burden, regional differences, trends, and health consequences of medication nonadherence for hypertension during 2010 to 2020: a meta-analysis involving 27 million patients. J Am Heart Assoc. 2022;11(17):e026582.

- Mahmood S, Jalal Z, Hadi MA, et al. Prevalence of non-adherence to antihypertensive medication in Asia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Clin Pharm. 2021;43(3):486–501.

- Bergland OU, Halvorsen LV, Søraas CL, et al. Detection of nonadherence to antihypertensive treatment by measurements of serum drug concentrations. Hypertension. 2021;78(3):617–628.

- Tomaszewski M, White C, Patel P, et al. High rates of non-adherence to antihypertensive treatment revealed by high-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (HP LC-MS/MS) urine analysis. Heart. 2014;100(11):855–861.

- Lee H, Yano Y, Cho SMJ, et al. Adherence to antihypertensive medication and incident cardiovascular events in young adults with hypertension. Hypertension. 2021;77(4):1341–1349.

- Hamrahian SM, Maarouf OH, Fülöp T. A critical review of medication adherence in hypertension: barriers and facilitators clinicians should consider. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2022;16:2749–2757.

- Mukete BN, Ferdinand KC. Polypharmacy in older adults with hypertension: a comprehensive review. J Clin Hypertens. 2016;18(1):10–18.

- Pantuzza LL, Ceccato MDGB, Silveira MR, et al. Association between medication regimen complexity and pharmacotherapy adherence: a systematic review. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2017;73(11):1475–1489.

- Ishida T, Oh A, Hiroi S, et al. Treatment patterns and adherence to antihypertensive combination therapies in Japan using a claims database. Hypertens Res. 2019;42(2):249–256.

- Parati G, Kjeldsen S, Coca A, et al. Adherence to single-pill versus free-equivalent combination therapy in hypertension: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hypertension. 2021;77(2):692–705.

- Weisser B, Predel HG, Gillessen A, et al. Single pill regimen leads to better adherence and clinical outcome in daily practice in patients suffering from hypertension and/or dyslipidemia: results of a meta-analysis. High Blood Press Cardiovasc Prev. 2020;27(2):157–164.

- Hong SJ, Sung KC, Lim SW, et al. Low-dose triple antihypertensive combination therapy in patients with hypertension: a randomized, double-blind, phase II study. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2020;14:5735–5746.

- Neldam S, Lang M, Jones R. Telmisartan and amlodipine single-pill combinations vs amlodipine monotherapy for superior blood pressure lowering and improved tolerability in patients with uncontrolled hypertension: results of the TEAMSTA-5 study. J Clin Hypertens. 2011;13(7):459–466.

- Miranda RD, Mion D, Jr, Rocha JC, et al. An 18-week, prospective, randomized, double-blind, multicenter study of amlodipine/ramipril combination versus amlodipine monotherapy in the treatment of hypertension: the assessment of combination therapy of amlodipine/ramipril (ATAR) study. Clin Ther. 2008;30(9):1618–1628.

- Izzo JL, Jr, Purkayastha D, Hall D, et al. Comparative efficacy and safety of amlodipine/benazepril combination therapy and amlodipine monotherapy in severe hypertension. J Hum Hypertens. 2010;24(6):403–409.

- Kang SM, Youn JC, Chae SC, et al. Comparative efficacy and safety profile of amlodipine 5 mg/losartan 50 mg fixed-dose combination and amlodipine 10 mg monotherapy in hypertensive patients who respond poorly to amlodipine 5 mg monotherapy: an 8-week, multicenter, randomized, double-blind phase III noninferiority study. Clin Ther. 2011;33(12):1953–1963.

- Wang KL, Yu WC, Lu TM, et al. Amlodipine/valsartan fixed-dose combination treatment in the management of hypertension: a double-blind, randomized trial. J Chin Med Assoc. 2020;83(10):900–905.

- Tsioufis K, Kreutz R, Sykara G, et al. Impact of single-pill combination therapy on adherence, blood pressure control, and clinical outcomes: a rapid evidence assessment of recent literature. J Hypertens. 2020;38(6):1016–1028.

- Du LP, Cheng ZW, Zhang YX, et al. The impact of fixed-dose combination versus free-equivalent combination therapies on adherence for hypertension: a meta-analysis. J Clin Hypertens. 2018;20(5):902–907.

- Sherrill B, Halpern M, Khan S, et al. Single-pill vs free-equivalent combination therapies for hypertension: a meta-analysis of health care costs and adherence. J Clin Hypertens. 2011;13(12):898–909.

- Gupta AK, Arshad S, Poulter NR. Compliance, safety, and effectiveness of fixed-dose combinations of antihypertensive agents: a meta-analysis. Hypertension. 2010;55(2):399–407.

- Bangalore S, Kamalakkannan G, Parkar S, et al. Fixed-dose combinations improve medication compliance: a meta-analysis. Am J Med. 2007;120(8):713–719.

- Sung J, Ahn KT, Cho BR, et al. Adherence to triple-component antihypertensive regimens is higher with single-pill than equivalent two-pill regimens: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Transl Sci. 2021;14(3):1185–1192.

- Kim SJ, Kwon OD, Cho B, et al. Effects of combination drugs on antihypertensive medication adherence in a real-world setting: a Korean nationwide study. BMJ Open. 2019;9(6):e029862.

- Saito I, Kushiro T, Matsushita Y, et al. Medication-taking behavior in hypertensive patients with a single-tablet, fixed-dose combination in Japan. Clin Exp Hypertens. 2016;38(2):131–136.

- Kumagai N, Onishi K, Hoshino K, et al. Improving drug adherence using fixed combinations caused beneficial treatment outcomes and decreased health-care costs in patients with hypertension. Clin Exp Hypertens. 2013;35(5):355–360.

- Patel BV, Remigio-Baker RA, Thiebaud P, et al. Improved persistence and adherence to diuretic fixed-dose combination therapy compared to diuretic monotherapy. BMC Fam Pract. 2008;9:61.

- Liakos CI, Papadopoulos DP, Kotsis VT. Adherence to treatment, safety, tolerance, and effectiveness of perindopril/amlodipine fixed-dose combination in Greek patients with hypertension and stable coronary artery disease: a Pan-Hellenic prospective observational study of daily clinical practice. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2017;17(5):391–398.

- Manolis A, Grammatikou V, Kallistratos M, et al. Blood pressure reduction and control with fixed-dose combination perindopril/amlodipine: a Pan-Hellenic prospective observational study. J Renin Angiotensin Aldosterone Syst. 2015;16(4):930–935.

- Vlachopoulos C, Grammatikou V, Kallistratos M, et al. Effectiveness of perindopril/amlodipine fixed dose combination in everyday clinical practice: results from the EMERALD study. Curr Med Res Opin. 2016;32(9):1605–1610.

- Setiawati A, Kalim H, Abdillah A. Clinical effectiveness, safety and tolerability of amlodipine/valsartan in hypertensive patients: the Indonesian subset of the EXCITE study. Acta Med Indones. 2015;47:223–233.

- Rosenkranz AR, Ratzinger M. Efficacy, safety, and tolerability of antihypertensive therapy with aliskiren/amlodipine in clinical practice in Austria. The RALLY (rasilamlo long lasting efficacy) study. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2015;127(5-6):203–209.

- Jadhav U, Hiremath J, Namjoshi DJ, et al. Blood pressure control with a single-pill combination of indapamide sustained-release and amlodipine in patients with hypertension: the EFFICIENT study. PLoS One. 2014;9(4):e92955.

- Khan W, Moin N, Iktidar S, et al. Real-life effectiveness, safety, and tolerability of amlodipine/valsartan or amlodipine/valsartan/hydrochlorothiazide single-pill combination in patients with hypertension from Pakistan. Ther Adv Cardiovasc Dis. 2014;8(2):45–55.

- Kızılırmak P, Berktaş M, Yalçın MR, et al. Efficacy and safety of valsartan and amlodipine single-pill combination in hypertensive patients (PEAK study). Turk Kardiyol Dern Ars. 2013;41(5):406–417.

- Hostalek U, Koch EMW. Treatment of hypertension with a fixed-dose combination of bisoprololand amlodipine in daily practice: results of a multinational non-investigational study. Cardiovasc Disord Med. 2016;1:10.

- Glasziou PP, Clarke P, Alexander J, et al. Cost-effectiveness of lowering blood pressure with a fixed combination of perindopril and indapamide in type 2 diabetes mellitus: an ADVANCE trial-based analysis. Med J Aust. 2010;193(6):320–324.

- Joint Committee for Guideline Revision. 2018 Chinese guidelines for prevention and treatment of hypertension-a report of the revision committee of Chinese guidelines for prevention and treatment of hypertension. J Geriatr Cardiol. 2019;16:182–241.

- Hua Q, Fan L, Li J. 2019 Chinese guideline for the management of hypertension in the elderly. J Geriatr Cardiol. 2019;16(2):67–99.

- Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on clinical practice guidelines. Hypertension. 2018;71:1269–1324.

- Unger T, Borghi C, Charchar F, et al. 2020 International Society of Hypertension global hypertension practice guidelines. Hypertension. 2020;75(6):1334–1357.

- World health Organization. Guideline for the pharmacological treatment of hypertension in adults. 2021. [cited December 2022]. Available from https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240033986.

- Chung S, Ko YG, Kim JS, et al. Effect of FIXed-dose combination of ARB and statin on adherence and risk factor control: the randomized FIXAR study. Cardiol J. 2022;29(5):815–823.

- Choi J, Sung KC, Ihm SH, et al. Central blood pressure lowering effect of telmisartan-rosuvastatin single-pill combination in hypertensive patients combined with dyslipidemia: a pilot study. J Clin Hypertens. 2021;23(9):1664–1674.

- Blood Pressure Lowering Treatment Trialists’ Collaboration. Pharmacological blood pressure lowering for primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease across different levels of blood pressure: an individual participant-level data meta-analysis. Lancet. 2021;397:1625–1636.

- Moriarty F, Bennett K, Fahey T. Fixed-dose combination antihypertensives and risk of medication errors. Heart. 2019;105(3):204–209.

- Wang N, Salam A, Webster R, et al. Association of low-dose triple combination therapy with therapeutic inertia and prescribing patterns in patients with hypertension: a secondary analysis of the TRIUMPH trial. JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5(11):1219–1226.

- Chow CK, Teo KK, Rangarajan S, et al. Prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension in rural and urban communities in high-, middle-, and low-income countries. JAMA. 2013;310(9):959–968.

- van der Linden EL, Agyemang C, van den Born BH. Hypertension control in Sub-Saharan Africa: clinical inertia is another elephant in the room. J Clin Hypertens. 2020;22(6):959–961.

- Seedat YK. Why is control of hypertension in Sub-Saharan Africa poor? Cardiovasc J Afr. 2015;26(4):193–195.

- Rubinstein A, Alcocer L, Chagas A. High blood pressure in Latin America: a call to action. Ther Adv Cardiovasc Dis. 2009;3(4):259–285.

- Brettler JW, Arcila GPG, Aumala T, et al. Drivers and scorecards to improve hypertension control in primary care practice: recommendations from the HEARTS in the Americas innovation group. Lancet Reg Health Am. 2022;9:1–11.