Abstract

Objective

The value of patient involvement to the design, conduct, and outcomes of healthcare research is increasingly being recognized. Patient involvement also provides greater patient accessibility and contribution to research. However, the use of inaccessible and technical language when communicating with patients is a barrier to effective patient involvement.

Methods

We analyzed peer-reviewed and gray literature on how language is used in communication between healthcare researchers and patients. We used this analysis to generate a set of recommendations for healthcare researchers about using more inclusive and accessible language when involving patients in research. This scoping review adheres to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) extension for Scoping Review (PRISMA-ScR) checklist.

Results

Four major themes about the use of language were developed from the literature analysis and were used to develop the set of recommendations. These recommendations include guidance on using standardized terminology and plain language when involving patients in healthcare research. They also discuss the implementation of co-development practices, patient support initiatives, and researcher training, as well as ways to improve emotional awareness and the need for greater equality, diversity, and inclusion.

Discussion and conclusion

The use of inclusive, empathetic, and clear language can encourage patients to be involved in research and, once they are involved, make them feel like equal, empowered, and valued partners. Working toward developing processes and guidelines for the use of language that enables an equal partnership between researchers and patients is critical.

PLAIN LANGUAGE SUMMARY

Patient and public involvement is when patients, carers, and the public are included as partners in all stages of healthcare research. Patient involvement has been shown to have a positive impact on people and on research itself, but researchers often use language that is complicated, confusing, or unsuitable for patients. This can lead to less meaningful patient involvement in research.

Our work looked at two areas: (1) how using unsuitable language can be a barrier to effective and meaningful patient involvement; and (2) what can be done to help improve communication between healthcare researchers and patients.

We started by finding out what has already been researched and published in these areas. We looked in medical journal databases for articles that were relevant to the topic. We also searched Google and the websites of relevant organizations. From looking at these sources, we found four common themes. These themes are: (1) lack of standardized terminology for patients involved in research; (2) consistent overuse of technical, scientific, and medical language; (3) positive outcomes of using language to show emotional understanding; and (4) language as a powerful tool for promoting diversity, equality, and inclusion of patients involved in research.

Using these themes, we then developed seven recommendations to help improve how healthcare researchers and patients communicate with each other. These recommendations are: (1) using standardized terminology; (2) using plain language; (3) co-developing patient information; (4) providing patient training, mentoring, and support; (5) introducing researcher training; (6) having emotional awareness; and (7) improving equality, diversity, and inclusion.

A graphical plain language summary can be found as Supplementary material for this article.

Introduction

Language definitions

For the purpose of this paper, we use the term “patients” to encompass all patients, family members, and carers who share their concerns and perspectives in healthcare research, irrespective of their sex, gender, ethnicity, education, socioeconomic status, or age. We use the terms “involvement” and “patient centricity” to describe the active engagement and participation of patients in the design, conduct, and/or dissemination of health research. Finally, we use the term “healthcare researcher” to describe any professional, either publicly funded or industry-sponsored, who works directly with patients or patient data, to conduct research on health, disease, and treatments.

Background

The involvement of patients in healthcare research or healthcare decision-making is often termed “patient and public involvement,” “patient engagement,” or “patient centricity.” Although these terms vary and are used inconsistently, they share some common concepts: listening to and partnering with patients and placing their perspectives and well-being at the core of all initiativesCitation1,Citation2.

The value that patients can bring to the design and conduct of healthcare research is being increasingly recognizedCitation3–5. Partnering with patients in research has been shown to improve individual and public health outcomesCitation3. Patient centricity enables patients to contribute as equal partnersCitation4 in a democratic mannerCitation6, allows an empowered and emancipated patient voice to effect tangible change in research processesCitation7,Citation8, and leads to greater patient accessibility to researchCitation5. Patient involvement in healthcare research has also been shown to have a positive impact on researchers themselves, allowing them to gain new insights into disease experience, to learn how to better communicate with patients about their disease, and to re-evaluate their own personal and professional valuesCitation9,Citation10.

Healthcare researchers, whether they are publicly funded or industry-sponsored, must therefore carefully consider how to meaningfully partner with and involve patients. Several guidelines are available for publicly funded researchers on best practice, particularly in the UKCitation11–14, and patient involvement is a requirement in many grant applications. Additionally, regulatory agencies, such as the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) in the UK, have also published patient involvement guidelines for their work and employees, including training programs focused on patient involvement best practiceCitation15. A comparable level of requirement and guidance on patient involvement is still lacking within industry-sponsored healthcare research, although some progress has been made in recent yearsCitation5,Citation16.

Even when patient involvement is planned for in a research project, it may not always be effective. To be meaningful and have impact, patient involvement must overcome several barriers. One major barrier that hampers effective patient involvement is a lack of clear, open, and transparent language for communication between healthcare researchers and patientsCitation17. Examples include the use of technical, scientific, or generally inaccessible language by researchers when communicating important information with patients, particularly those who are vulnerable (e.g. elderly patients or those who have difficulty communicating or understanding) or have low levels of health literacyCitation18. Another example includes the use of language that does not enable effective involvement of patients from minority groups, who are under-represented in contemporary healthcare researchCitation19. Poor communication by healthcare researchers can have an ostracizing effect on patients and can result in patients not feeling they are able to actively contribute to research, or not feeling like they are involved in the first instanceCitation20.

It is therefore important to understand how language is used in communication between healthcare researchers and patients in the design and conduct of healthcare research, and to assess whether it allows for a diverse population of patients to contribute meaningfully and equally to the design and conduct of research.

Objective

This scoping review seeks to address several research questions.

Question 1. What terminology is used to refer to patients who are involved in the design and/or conduct of health research? Are these terms clear and uniform, and are they well understood by patients?

Question 2. What strategies and interventions have industry and academia adopted to ensure more inclusive and accessible language in their communication with patients, and what were the outcomes of these interventions?

Question 3. Within communication in English, is there a consideration to ensure the equality, diversity, and inclusivity of different perspectives, especially across different races and ethnicities?

After synthesizing the available literature, this paper offers a set of recommendations for professionals working in health research, in particular life science industries, about how they can adopt more inclusive and accessible language when involving patients as partners in research.

Methods

The research team comprised multiple stakeholders including academic researchers, industry researchers, and patients. We chose a scoping review format because of the wide scope of the topic and the fact that the source information is dispersed across both peer-reviewed and gray literature. We also determined that it would identify common themes and other qualitative data, as well as highlight knowledge gaps within the literature, better than other review methodologiesCitation21–29. This methodology allowed us to critically appraise and answer specific questions to produce our set of recommendations. This scoping review adheres to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) extension for the Scoping Review (PRISMA-ScR) checklistCitation21,Citation30,Citation31.

Patient and public involvement

The development of the research questions and outcome measures were informed by inclusion of a patient within the authorship team who was involved in the conceptualization, design, searching, and writing for this article. During the conceptualization and design discussions within the authorship team of this research, the patient contributed their lived experience as a patient, as well as their expertise from working for and with patient–carer groups. This helped to guide how the research was to be undertaken, how the literature search should be conducted, and informed our recommendations. Patient and public involvement in this work adheres to Guidance for Reporting Involvement of Patients and the Public (GRIPP2) short form guidanceCitation32.

Initial scoping

Before initiating a comprehensive literature search, a targeted web search using Google and Google Scholar was conducted to identify relevant terms, definitions, and frameworks common across a range of sources, and to determine the potential importance of material within the gray literature.

Search strategy

A comprehensive literature search of MEDLINE, Embase, and the Cochrane Library was conducted for peer-reviewed articles published over a 10-year period, from October 2011 to October 2021. This time frame was chosen to allow for the inclusion of a sufficient volume of recent literature while keeping the amount of information manageable for review. Search terms included “patient centricity,” “patient-centred,” “patient involvement,” “patient-centric initiatives,” “patient-centred care,” “patient engagement,” “patient participation,” “patient communication,” and “patient carer” as well as Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms. Single search strings and combination search strings using Boolean operators “AND” or “OR” were utilized. A full list of search terms used in this peer-reviewed literature search is shown in . The search included both free text and MeSH terms.

Table 1. Keywords used for the peer-reviewed literature search.

During the initial scoping exercise, gray literature was identified as an important source of information about this topic. Therefore, a concurrent and comprehensive manual search of the gray literature was also conducted. The following abbreviated search strategy was determined through the co-authors’ expert knowledge of the field. The full gray literature search strategy is outlined in Supplementary Appendix S1.

An initial search using the keywords outlined in using Google Advanced Search, filtering results by “English Language” and searching only the first two pages of results.

A search using the keywords outlined in on the global and UK websites of the five largest pharmaceutical companies in the world, ranked by their revenue in 2021. These companies were Johnson & Johnson, Pfizer, Roche, AbbVie, and NovartisCitation33.

A search of the keywords outlined in on the websites of various healthcare initiatives, public–private partnership consortia, research funders, pharmaceutical forums, and industry bodies, which are outlined in Supplementary Appendix S1.

Table 2. Keywords used for the gray literature search.

The list of search terms used in the comprehensive gray literature search is shown in . These keywords are a subset of those in and were selected as the terms deemed to achieve a wide-ranging coverage of the relevant gray literature while keeping the search manageable. A small number of additional sources previously known to the authors were also included in the search.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies were included on the basis of predefined–defined eligibility criteria (). Studies were excluded if they focused on:

Table 3. Eligibility criteria for data extraction.

Health service design and provision, or communication with healthcare providers.

Dissemination of research to patients and other stakeholders.

Communication between patients and either industry or academic researchers in a language other than English.

Screening procedures

All articles that met the inclusion criteria in the comprehensive peer-reviewed literature search underwent title and abstract screening. The remaining articles were subsequently selected for full text review to identify the final articles for inclusion.

One reviewer conducted both the title and abstract screening. The same reviewer also conducted the full text review. A second reviewer independently screened 20% of the articles to check for agreement and avoid selection bias. The level of agreement between reviewers was quantified with a kappa score. The weighted kappa score was 0.73, indicating substantial agreement. Any discrepancies between reviewers were resolved by consensus.

One reviewer conducted the gray literature search and subsequent screen. All articles that were retrieved from the gray literature search were manually screened against the inclusion criteria and assessed for relevance following title and full text review.

Data extraction and synthesis

A data extraction table was developed to ensure systematic retrieval of the following information from the comprehensive peer-reviewed literature search: title, reference citation, year, country, study design, summary of methodology, results, and patient characteristics (Supplementary Appendix S2).

Thematic analysis, a method based on the analysis and identification of repeated patterns across a dataset, was used to systematically identify and sequentially derive emerging themes. Thematic analysis was conducted by two reviewers independently and then iterated through discussion with the whole authorship teamCitation21,Citation34.

During the full text review of the gray literature search, the sources were evaluated for their relevancy to discussing the use of language between healthcare researchers and patients. Irrelevant sources and those that did not contain useful data in order to discuss this topic were excluded. Records were also excluded if the source was inaccessible, a duplication, or a summary of a larger document. Data were manually extracted from each source and the following information was retrieved: title, author/organization, summary of information, within allocated time frame of search, and uniform resource locator (URL) (Supplementary Appendix S3).

A scoping approach was chosen to synthesize the data and generate new insights beyond a summary of the findingsCitation21–29.

Results and discussion

Literature search, screen, and exclusion process

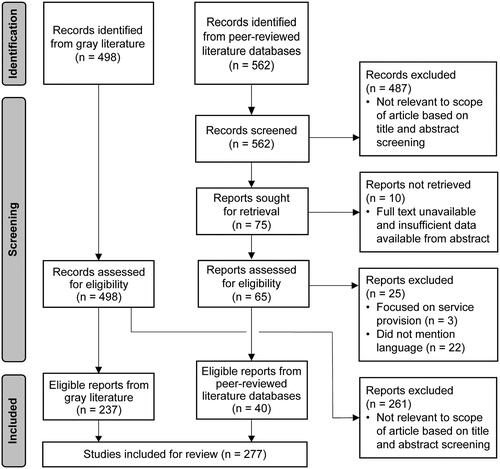

In total, 562 articles were retrieved from the peer-reviewed literature search, and 487 were excluded. Seventy-five remaining articles were selected for full text review to identify the final articles for inclusion.

A further 498 articles, guidelines, and resources were identified from the gray literature search, of which 261 were excluded.

After full text review, 40 articles from the comprehensive peer-reviewed literature search (Supplementary Appendix S2) and 237 items from the gray literature search (Supplementary Appendix S3) were identified for inclusion. The full selection process, including reasons for exclusion, is represented in a flow diagram ()Citation30,Citation31.

Figure 1. Flow diagram outlining the process for identification, screening, and inclusion of studies from peer-reviewed literature databases and the gray literatureCitation30,Citation31.

Four major themes were developed from the literature analysis to help answer our research questions

Question 1. What terminology is used to refer to patients who are involved in the design and/or conduct of health research? Are these terms clear and uniform, and are they well understood by patients?

Theme 1. There is a lack of standardized terminology for patients involved in research

Based on our expertise, the terminology regarding the roles, tasks, and responsibilities of patients involved in research clearly appears to be growing, but our searches revealed inconsistent use of this terminology in research (). Terms such as “engagement,” “involvement,” “partnership,” and “co-production,” among many others, are rarely defined and, although similar, often represent distinct conceptsCitation35.

A horizon scan of terms and definitions related to patient involvement found more than 20 terms used across multiple sectorsCitation36. The scan also found that single terms had up to seven different definitionsCitation36. These findings corresponded with our own analysis of terminology, in which 12 different terms for involvement and five terms to describe patients were coded ().

Table 4. Terms coded within our analysis for involvement and to describe patients.

Beyond being an etymological concern, this variety and disparity in terminology makes it difficult to establish clear aims for patients involved in research and is a barrier to the active collaboration of researchers and patientsCitation37–39. For instance, there may be language barriers in the interpretation of words like “engagement” and “involvement,” with one study noting that “engagement” in some languages may imply that there is a fee for serviceCitation40. Another study notes that the interchangeable use of terms such as “involving,” “participating,” “collaborating,” “consulting,” and “engaging” when referring to patients can be confusing for both patients and researchers, and that terms like “co-production” may imply consulting patients regularly or that they are actively involved in collecting and interpreting research dataCitation41.

Using language precisely and consistently can avoid negative consequences, such as unclear expectations, power imbalances, or hesitation from patients about being involved in researchCitation42. Several institutions, such as the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR)Citation43, UK Research and Innovation (UKRI)Citation44, and CochraneCitation45, have sought to clarify the terms used for referring to patients involved in research.

Additionally, a Dutch study has reported a tool designed to specifically describe and explain the different roles of patients and researchers within distinct stages of a research project. Titled the “Involvement Matrix,” the tool describes five different roles (listener, co-thinker, advisor, partner, and decision-maker) and three different stages in which patient involvement can occur (preparation, execution, and implementation)Citation46. A similar tool developed by the International Association for Public Participation (IAP2) also describes a spectrum of terms (inform, consult, involve, collaborate, and empower) and their associated desired outcomes for patient involvement in healthcare researchCitation47.

However, although several studies and guidelines advocate for different terms to refer to patients involved in research, this may have unintentionally added to the growing lexicon and created more confusion rather than clarity.

Summary statement. To tackle the growing, unclear, and confusing lexicon for patient involvement in research, standardized terminology should be implemented across industry and academia when referring to the types of research involvement that patients can have.

Question 2. What strategies and interventions have industry and academia adopted to ensure more inclusive and accessible language in their communication with patients, and what were the outcomes of these interventions?

Theme 2. There is consistent overuse of technical, scientific, and medical language

Researchers often communicate with patients using technical, scientific, and medical language. This technical language can be a significant barrier to establishing effective partnerships with patients. Jargon, acronyms, and superfluous medical or clinical terms are often not known or understood by patientsCitation48–51. Patients can also feel overwhelmed by a large amount of new information and have difficulty discerning what the most important points areCitation52,Citation53. As a result, patients may not completely understand the process and direction of the research being undertaken, limiting their ability to contribute in meaningful and feasible waysCitation54. In addition, patients may feel intimidated and alienated from the researchCitation53 and become less actively involvedCitation55.

Overuse of technical language can also reinforce power imbalances between patients and researchersCitation56. These effects are more evident for certain patient populations, such as pediatric patientsCitation57–61, older patientsCitation62,Citation63, and those living with dementiaCitation50,Citation64. The overuse of technical language also has immediate consequences for researchers, because it can lead to the false perception that patients are not equipped or able to contribute, and may reduce efforts to involve patients, especially those considered to be from harder-to-reach groups. Often, patients with lived experiences offer valuable insights that can substantially aid research design and implementation, thus helping with patient recruitment, adherence, and retention. Technical and inaccessible language can create barriers to hearing these valuable insights by triggering and alienating patients into feeling that they cannot adequately contribute. It may also lead to research results not being truly representative, because the profile of the patients involved does not match the studied populationCitation65.

Summary statement. The overuse of technical, scientific, and medical language when communicating with patients has frequently been shown to be a barrier to effective and meaningful patient involvement. Despite this, healthcare researchers continue to overuse jargon, acronyms, and superfluous medical information. Using plain language and health literacy principles when communicating with patients could ensure more inclusive and accessible patient involvement.

Theme 3. Positive outcomes of using language to show emotional understanding

The language used when involving patients should recognize the social and emotional needs of patients, as well as their experience of living with a disease and the impact that this has on themCitation66. Patients can feel that the discussions and meetings they participate in are solely scientific and task-oriented. Patients tend to appreciate more unstructured and social language and having more informal introductions and discussions with the study team, because this makes them feel valued as individuals as well as research partnersCitation67,Citation68. Patients also appreciate when time is given to understanding their storiesCitation69, how and why they became involved in research, and what impact they could haveCitation49. They also appreciate hearing about the impact of their involvement from the researchers with whom they are workingCitation49.

The benefits of using emotionally engaged and inclusive communication have also been felt by researchers. An emphasis on sharing and understanding the individual stories and experiences of patients and researchers can lead to mutual learning and new insightsCitation9. In one study, researchers reflected on how this allowed them to connect with patients, relate to their experience of disease, and feel empowered to understand and approach patients about all the aspects of their diseaseCitation9. Another study reported that meeting patients who were involved in research had a “profound impact” on the personal and professional values of some researchers. This included one researcher re-evaluating their career and another calling for a change in how researchers conduct their work. Some of the researchers within this study also reported being surprised at the level of interest and enthusiasm about research that was shown by the patientsCitation10.

Our findings also highlight the importance of using language to show an understanding of the constraints and needs of patients, many of whom have other occupations and may be living with a chronic illnessCitation70. For instance, patients appreciate language that acknowledges that they may be busy and have other commitments, including jobs or familyCitation57, and that the researchers were being thoughtful and accommodating of these circumstancesCitation67,Citation71. Patients appreciate receiving acknowledgment of the benefits of their contribution, such as reports about how their input was used in researchCitation72, and messages of thanks for their contributionsCitation72, or celebrating major milestonesCitation9,Citation72.

Beyond highlighting the importance of using emotionally aware language, one study designed a communication tool that enabled patients to share what was important to them as research partners, and how to jointly set an agenda. This tool also guided both patients and researchers on how to navigate disagreements through the use of constructive and empathic languageCitation73.

Summary statement. Several studies have shown the positive outcomes of using emotionally aware language when communicating with patients. These positive outcomes are not limited to patients either, as healthcare researchers have frequently reported positive impacts on their working practices and outlook.

Question 3. Within communication in English, is there a consideration to ensure equality, diversity, and inclusivity of different perspectives, especially across different races and ethnicities?

Theme 4. Language as a powerful tool for promoting diversity, equality, and inclusion of patients involved in research

It is important to involve patients who reflect the diversity of the population and of a particular conditionCitation74. This is particularly true of those from under-represented and vulnerable groups (e.g. minority, poor, rural, inner city, and underserved populations)Citation75,Citation76, and this is considered within NIHR standardsCitation77. There is currently insufficient diversity among patients involved in researchCitation65,Citation66,Citation78, especially with regard to people from minority ethnic communities and faith groups, as well as single parents, non-heterosexual people, those with disabilities, and those who do not have a university educationCitation53.

The use of language that is not inclusive or tailored to the needs of patients may result in the involvement of only those patients with higher levels of education, more financial security, and more available timeCitation79. This may lead to patients turning into professionals and the development of so-called “professional” patient representativesCitation80. If only a select few “professional” patient representatives are involved in research, there may be a substantial bias, leading to decreased inclusivity and equity in the positions and opinions that come across through the inclusion of patient perspectivesCitation81. Although barriers to diverse, equal, and inclusive patient involvement can arise at any time during a research project, many studies have shown that inappropriate recruitment materials are often a major hurdle for such involvement. Therefore, high-quality and tailored recruitment materials using the appropriate language are critical to achieve greater diversity, equality, and inclusion for patient involvement in researchCitation82.

Summary statement. It is well known that there is a lack of diversity in the patient populations involved in healthcare research. The proper use of inclusive and tailored language can create a patient demographic involved in research that is more representative of the diverse populations we live in and of a specific condition.

Recommendations

Our literature analysis and personal experience highlight several gaps and pitfalls relating to the use of language in healthcare research.

Here, we outline several recommendations to help improve the communication between healthcare researchers and patients.

We believe that these recommendations should lead to more meaningful recruitment, involvement, and retention of patients throughout healthcare research processes. However, although we recommend that key standardized practices are implemented across healthcare research, we acknowledge that there is a need for individualized processes in many situations.

Standardized terminology

To ensure transparency and clear expectations, we advocate for standardized terminology across industry and academia that can be universally used to refer to the types of involvement that patients can have, and how terminology shapes the patients’ roles and responsibilitiesCitation18. This would require the relevant bodies across industry and academia to come together to standardize and implement. The standardized terminology can be used to establish a common ground between researchers and patients at the beginning of a research project, before developing individualized terminology within each projectCitation18. However, once individualized terminology is introduced within a specific research project, it is the researcher’s and organization’s responsibility to ensure that the language used is continuous and consistent in order to avoid confusion and ambiguity. Standardized and individualized terminology should be designed in partnership with a diverse demographic of patients and be accessible and culturally awareCitation56,Citation83.

Plain language

Acronyms and jargon should be avoided where possibleCitation56,Citation61,Citation84, and plain language should be usedCitation38,Citation70,Citation83,Citation85,Citation86. Questions should be kept simple, unambiguous, and answerableCitation72. Health literacy guidelinesCitation51,Citation70, as well as tools for screening patients at risk of low health literacyCitation87, could be used when conducting patient involvement activities. Health literacy screening tools can help researchers to understand the level of health literacy of patients on a case-by-case basisCitation87. Researchers can then tailor their language appropriately for communication with individual patients and employ appropriate health communication techniques for patients with low health literacyCitation88.

Any information that is meant to be shared with patients involved in research should be reviewed with the specific purpose of improving readability and making sure both language and content are appropriateCitation1,Citation81. Industry and academia should embed health literacy processes and tools into their standard practices when producing all patient-facing materials and documents. There should also be opportunities for patients to check their understanding of information throughout the whole research project.

Although several interventions have been suggested or have already been adopted by industry and academia to overcome poor communication between healthcare researchers and patientsCitation43,Citation89–94, we believe there remains a need to develop specific processes and guidance about the language used when researchers and patients work together.

Co-development

All information and materials developed for patient use should be co-developed with patients to encourage involvementCitation70,Citation94,Citation95. There should be many opportunities for patients to contribute to the design and development of these materials, provide feedback, and ask questions throughout the development process. Co-development aids plain language, understandability, the use of culturally appropriate language, and actionabilityCitation96.

Patient training, mentoring, and support

Adequate tools and support, such as those offered by the European Patients’ Academy on Therapeutic Innovation (EUPATI)Citation93,Citation97,Citation98 and Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI)Citation99 should be advertised and made available by industry and academia for patients who want mentoring or training in order to fully participate in healthcare research processes. This includes improving patients’ understanding of the language and processes of researchCitation40,Citation54,Citation100, the background information on the relevant research topicCitation54, and how to interact effectively with researchersCitation54. Through condensed, easy-to-understand background information, patients can become acquainted with the language and terms used in a relevant area of research, at their own pace and preferenceCitation101. In time, this learning will allow patients to meaningfully contribute to all stages of the research processes, providing researchers with valuable insights from experienced patient research partnersCitation102.

Researcher training

Patient involvement training and tools are currently available for researchersCitation94,Citation103–108. These tend to focus on the value of patient involvementCitation4, how to ensure that the language used is simple and concise while still being scientifically accurate and compliantCitation106,Citation107, and how to use language in a way that encourages meaningful involvementCitation35,Citation63. However, training is usually not mandatory and is frequently not attended owing to the heavy and conflicting schedules of healthcare researchers. We therefore recommend that researcher training programs focused on patient involvement and patient-friendly language become mandatory as part of induction and early-career researcher processes.

Emotional awareness

Interactions between researchers and patients should not be transactional but true partnerships. Industry and academic processes should support these ways of working by using emotionally aware language that makes patients feel they are trusted and valued partners. Thanking patients and providing feedback should be routine across industry and academia, but we should go further. We recommend that researchers commit to building long-term relationships with patients and helping to support the emotional well-being of patients throughout the research processCitation56. For example, researchers could help to schedule regular check-ups with patients to discuss their well-being or help to set up support groups between patients with similar lived experiences. However, studies have also shown that for time- and money-limited researchers, realistically, this is beyond the remit of the individual researcher. Structural and organizational support is necessary, but often lacking, in order to support long-term and meaningful patient involvement practicesCitation109,Citation110.

Researchers have also described the emotional burdens that can occur upon themselves when building long-term relationships with patients. Patient involvement also tends to fall under the responsibility of junior staff, complicating the incorporation of emotive and meaningful patient involvement when power imbalances or a lack of support by senior staff are present. Furthermore, junior staff are often employed on short-term contracts, whereby long-term emotional and meaningful partnerships with patients will be hard to build. Therefore, practical and social support from organizations is fundamental to achieving long-term effective and emotive patient involvementCitation109,Citation110.

Equality, diversity, and inclusion

Researchers wanting to involve patients in research should use a broad range of channels and media for outreach, such as social media, online research networks, and videoCitation111–117. Recruitment information and training should be appropriate for a wide range of health literacy levelsCitation118, be readily accessible, and be available in multiple languagesCitation119,Citation120. A major issue encountered during our gray literature search was that resources related to patient involvement were not readily accessible through Google searches, and finding them required prior knowledge and expertise from the authors. This is in itself a problem and there is a need to make these resources more accessible, either by making them easier to find online – such as in places where patients can easily go and find them – or by providing the patients with the knowledge of how to find them. Recruitment and training materials also need to be appropriate and adjusted for those in more vulnerable patient communities, such as the elderlyCitation50,Citation57–60,Citation62–64. It can also be helpful to engage with a charity partner or directly with patient communitiesCitation18, where appropriate, as they can help to plan how to use language in a way that appeals to and engages diverse groups of peopleCitation79. Furthermore, researchers should consider meeting patients in person at inclusive locations, such as faith centers, community centers, schools, and libraries. This is particularly useful for recruiting patients from hard-to-reach communities, especially those who have low levels of computer literacy.

Limitations of this study

This review had several limitations. Firstly, it focused on barriers when communicating in English, as cross-language research presents additional challengesCitation121,Citation122. However, many of the principles and recommendations outlined within this review are likely to be applicable when conducting cross-language research. Secondly, there may be a publication bias, whereby information that shows the benefits and successes of patient involvement in research is more likely to be published over information that shows the challenges that can be involved. To minimize this potential bias, a comprehensive literature search, including gray literature from organizations conducting or advocating practices that support patient involvement, was undertaken to capture diverse and wide-ranging perspectives. However, the strategy in part relied on the expertise of the authorship team, so there may be other sources that were not discovered. In addition to this, because of the varied and inconsistent use of terminology around patient involvement within healthcare research, there is the possibility that other relevant sources using differing terminology were missed. Thirdly, while the authorship team includes academic, industry, and patient perspectives (two representatives from each group), the team is small and UK-based and may therefore not be fully representative. This study has also not differentiated between industry and academic sources during the scoping review process. In the authors’ experience, the ways of working and the understanding of the best practices around patient involvement often differ between industry and academia. Further work to differentiate between industry and academic information sources could help to clarify our recommendations. Penultimately, although our utilization of thematic analysis helped us to identify patterns in the literature data and develop our recommendations, it perhaps lacks the granularity of capturing language use patterns that a discourse analysis could provide. Future work employing a discourse analysis methodology could provide further important insightsCitation123–125. Finally, our analysis was focused on how language is used, rather than on the wider topic of how information is communicated between researchers and patients, which also impacts upon effective patient involvement in research.

Future directions

This work has focused on the current barriers and pitfalls related to the use of language that prevent meaningful patient involvement in healthcare research. To understand why these barriers exist in the first place, future research should focus on what prevents researchers from using clear, open, and transparent language with patients.

During our literature search, we also discovered that industry resources about patient involvement were far harder to find than academic resources. Future work should investigate why this is the case and whether industry should publish more on the topic of patient involvement.

Although our research has focused on technical, scientific, and medical language, the use of complicated legal language can also be a barrier to effective patient involvementCitation126,Citation127. Patients often encounter legal language in their first communications when joining a research project, such as in lengthy contracts. Therefore, ensuring that legal documents are clearly written in plain English should also be an essential step within effective patient involvement. Work in this area is being done, with the Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry (ABPI) advocating for the use of plain English and the avoidance of overly complex documents when developing written agreements and contracts. They also support the use of medical writing guides from the Plain English Campaign in order to help draft legal contracts for patients involved in researchCitation128,Citation129. Similarly, a joint report from eight British patient organization charities has shown that complex contracts are a barrier to effective patient involvement, as patients frequently do not understand the documents they are signing. The report has therefore recommended for legal contracts to be written in plain language or contain patient-friendly sectionsCitation130. Although the use of legal language is a gap in the authors’ experience, we believe that further work in the future is warranted to help to improve the use of plain English legal language within patient involvement practices.

To improve communication, it has been shown that specific training and education on patient involvement in research is valuable for both patients and researchersCitation131,Citation132. While several organizations within the UK and globally offer training for patients and researchers related to patient involvement in researchCitation41,Citation54, such training does not seem to be widely adopted as yetCitation17. In the authors’ experience, patients also frequently report that currently available training courses are often intensive, scarce, and frequently inaccessible for many demographic groups. Patients also reported that they would prefer short and informal workshops focusing on language, figures, computing, and the whys and hows of effective patient involvement. This shows a need to co-design training alongside patients and to tailor the teaching towards the needs of patients. We also believe that training materials must be provided in a variety of languages other than English, and also be accessible online as well as face to face. Future work should investigate how best to provide effective and meaningful training and how to minimize the barriers to the widespread adoption of such training.

To build upon the findings and recommendations of our work, a wider and more representative group of patients should be engaged. This group should include more patients and more people from outside of the UK and Europe, as well as people from socioeconomic and ethnic minority backgrounds who have been historically under-represented in healthcare research.

Conclusions

Language is a powerful tool. The use of inclusive and clear language can encourage patients to be involved in research and, once they are involved, make them feel like equal and valued partners. Working towards developing processes and guidelines for the use of language that enables an equal partnership between researchers and patients is critical.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This work was funded by Pfizer Ltd (award/grant number: not applicable).

Declaration of financial/other relationships

SD and NB are employees of Pfizer Ltd and hold Pfizer stock. RD, AB, and JP have no competing interests to report. Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Author contribution

Conceptualization: NB, SD, RD, and JP. Data curation: AB and Oxford PharmaGenesis. Formal analysis: AB and Oxford PharmaGenesis. Funding acquisition: NB and SD. Investigation: AB and Oxford PharmaGenesis. Methodology: NB, SD, RD, and JP. Project administration: NB and SD. Resources: NB and SD. Software: Not applicable. Supervision: NB, SD, RD, and JP. Validation: NB, SD, RD, and JP. Visualization: AB and Oxford PharmaGenesis. Roles/Writing – original draft: AB and Oxford PharmaGenesis. Writing – review and editing: NB, SD, RD, JP, AB, and Oxford PharmaGenesis.

Ethics statement

This work does not involve human participants and ethical approval was not required.

Patient consent statement

Any patients involved in this work confirm that they have seen the photo, image, text, or other material about themselves. They have read the article to be submitted and are legally entitled to give this consent.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (234.3 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (108.1 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (15.4 KB)Supplemental Material 1.docx

Download MS Word (17.3 KB)Supplemental Material 3. Gray literature.xlsx

Download MS Excel (51.2 KB)Supplemental Material 2. Peer-reviewed literature.xlsx

Download MS Excel (75.5 KB)Acknowledgements

Medical writing support was provided by Mark Elms PhD of PharmaGenesis London, London, UK, and Joana Osório PhD of Oxford PharmaGenesis, Oxford, UK, and was funded by Pfizer Ltd. These individuals have provided permission to be acknowledged. We also thank our patient advisors for their contribution to all aspects of this work.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the authors upon reasonable request.

References

- Collins SP, Levy PD, Holl JL, et al. Incorporating patient and caregiver experiences into cardiovascular clinical trial design. JAMA Cardiol. 2017;2(11):1263–1269. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2017.3606.

- Yeoman G, Furlong P, Seres M, et al. Defining patient centricity with patients for patients and caregivers: a collaborative endeavour. BMJ Innov. 2017;3(2):76–83. doi: 10.1136/bmjinnov-2016-000157.

- Harrington RL, Hanna ML, Oehrlein EM, et al. Defining patient engagement in research: results of a systematic review and analysis: report of the ISPOR patient-centered special interest group. Value Health. 2020;23(6):677–688. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2020.01.019.

- Domecq JP, Prutsky G, Elraiyah T, et al. Patient engagement in research: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14(1):89. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-14-89.

- Vat LE, Finlay T, Schuitmaker-Warnaar TJ, et al. Evaluating the “return on patient engagement initiatives” in medicines research and development: a literature review. Health Expect. 2020;23(1):5–18. doi: 10.1111/hex.12951.

- Frith L. Democratic justifications for patient public involvement and engagement in health research: an exploration of the theoretical debates and practical challenges. J Med Philos. 2023;48(4):400–412. doi: 10.1093/jmp/jhad024.

- Perestelo-Pérez L, Rivero-Santana A, Abt-Sacks A, et al. Patient empowerment and involvement in research. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2017;1031:249–264. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-67144-4_15.

- Williamson C. The patient movement as an emancipation movement. Health Expect. 2008;11(2):102–112. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2007.00475.x.

- Nierse CJ, Schipper K, van Zadelhoff E, et al. Collaboration and co-ownership in research: dynamics and dialogues between patient research partners and professional researchers in a research team. Health Expect. 2012;15(3):242–254. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2011.00661.x.

- Staley K, Abbey-Vital I, Nolan C. The impact of involvement on researchers: a learning experience. Res Involv Engagem. 2017;3(1):20. doi: 10.1186/s40900-017-0071-1.

- Parkinson’s UK. Patient and public involvement in research. [cited 2022 Apr 1]. Available from: https://www.parkinsons.org.uk/research/patient-and-public-involvement-research

- Diabetes UK. Patient and public involvement. Guidance for researchers. [cited 2022 Apr 1]. Available from: https://www.diabetes.org.uk/resources-s3/2017-09/0983_PPI%20resource_guidance-document_DL_v5.pdf

- National Institute for Health and Care Research. INVOLVE. Briefing notes for researchers: public involvement in NHS, public health and social care research. [cited 2022 Apr 1]. Available from: https://www.invo.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/9938_INVOLVE_Briefing_Notes_WEB.pdf

- National Health Service. Health Research Authority. Public involvement. [cited 2022 Apr 1]. Available from: https://www.hra.nhs.uk/planning-and-improving-research/best-practice/public-involvement/

- Medicines & Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. Patient involvement strategy: one year on. [cited 2023 Jul 17]. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/patient-involvement-strategy-one-year-on/patient-involvement-strategy-one-year-on

- Boutin M, Dewulf L, Hoos A, et al. Culture and process change as a priority for patient engagement in medicines development. Ther Innov Regul Sci. 2017;51(1):29–38. doi: 10.1177/2168479016659104.

- Smith SK, Selig W, Harker M, et al. Patient engagement practices in clinical research among patient groups, industry, and academia in the United States: a survey. PLoS One. 2015;10(10):e0140232. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0140232.

- Ocloo J, Garfield S, Franklin BD, et al. Exploring the theory, barriers and enablers for patient and public involvement across health, social care and patient safety: a systematic review of reviews. Health Res Policy Syst. 2021;19(1):8. doi: 10.1186/s12961-020-00644-3.

- Spinner JR, Haynes E, Nunez C, et al. Enhancing FDA's reach to minorities and under-represented groups through training: developing culturally competent health education materials. J Prim Care Community Health. 2021;12:21501327211003688. doi: 10.1177/21501327211003688.

- Mathur S, DeWitte S, Robledo I, et al. Rising to the challenges of clinical trial improvement in Parkinson’s disease. J Parkinsons Dis. 2015;5(2):263–268. doi: 10.3233/JPD-150541.

- Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32. doi: 10.1080/1364557032000119616.

- Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. 2010;5(1):69. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-5-69.

- Colquhoun HL, Levac D, O’Brien KK, et al. Scoping reviews: time for clarity in definition, methods, and reporting. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67(12):1291–1294. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.03.013.

- Davis K, Drey N, Gould D. What are scoping studies? A review of the nursing literature. Int J Nurs Stud. 2009;46(10):1386–1400. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2009.02.010.

- Munn Z, Peters MDJ, Stern C, et al. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2018;18(1):143. doi: 10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x.

- Peters MDJ, Godfrey CM, Khalil H, et al. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2015;13(3):141–146. doi: 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000050.

- Sarrami-Foroushani P, Travaglia J, Debono D, et al. Scoping meta-review: introducing a new methodology. Clin Transl Sci. 2015;8(1):77–81. doi: 10.1111/cts.12188.

- Schultz A, Goertzen L, Rothney J, et al. A scoping approach to systematically review published reviews: adaptations and recommendations. Res Synth Methods. 2018;9(1):116–123. doi: 10.1002/jrsm.1272.

- Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. A scoping review on the conduct and reporting of scoping reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2016;16(1):15. doi: 10.1186/s12874-016-0116-4.

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71.

- Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–473. doi: 10.7326/M18-0850.

- Staniszewska S, Brett J, Simera I, et al. GRIPP2 reporting checklists: tools to improve reporting of patient and public involvement in research. Res Involv Engagem. 2017;3(1):13. doi: 10.1186/s40900-017-0062-2.

- Fierce Pharma. The top 20 pharma companies by 2021 revenue. [cited 2022 Apr 29]. Available from: https://www.fiercepharma.com/special-reports/top-20-pharma-companies-2021-revenue

- Vaismoradi M, Turunen H, Bondas T. Content analysis and thematic analysis: implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nurs Health Sci. 2013;15(3):398–405. doi: 10.1111/nhs.12048.

- European Patients’ Forum. The value + toolkit. [cited 2022 May 9]. Available from: https://www.eu-patient.eu/globalassets/projects/valueplus/value-toolkit.pdf

- FasterCures. Milken Institute. Expanding the science of patient input: the power of language. [cited 2022 May 9]. Available from: https://milkeninstitute.org/sites/default/files/reports-pdf/Expanding%20the%20Science%20of%20Patient%20Input-The%20Power%20of%20Language_0.pdf

- Pizzo E, Doyle C, Matthews R, et al. Patient and public involvement: how much do we spend and what are the benefits? Health Expect. 2015;18(6):1918–1926. doi: 10.1111/hex.12204.

- National Institute for Health and Care Research. Going the extra mile: improving the nation’s health and wellbeing through public involvement in research. [cited 2022 May 9]. Available from: https://www.nihr.ac.uk/documents/about-us/our-contribution-to-research/how-we-involve-patients-carers-and-the-public/Going-the-Extra-Mile.pdf

- Patient Focused Medicines Development. Patient centricity – a collaborative definition. [cited 2022 May 24]. Available from: https://patientfocusedmedicine.org/patient-centricity-collaborative-definition/

- Boudes M, Robinson P, Bertelsen N, et al. What do stakeholders expect from patient engagement: are these expectations being met? Health Expect. 2018;21(6):1035–1045. doi: 10.1111/hex.12797.

- Hoddinott P, Pollock A, O’Cathain A, et al. How to incorporate patient and public perspectives into the design and conduct of research. F1000Research. 2018;7:752. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.15162.1.

- Black A, Strain K, Wallsworth C, et al. What constitutes meaningful engagement for patients and families as partners on research teams? J Health Serv Res Policy. 2018;23(3):158–167. doi: 10.1177/1355819618762960.

- National Institute for Health and Care Research. INVOLVE. Jargon buster. [cited 2022 May 9]. Available from: https://www.invo.org.uk/resource-centre/jargon-buster/

- United Kingdom Research and Innovation. Understanding health research. Patient and public involvement. [cited 2022 Aug 16]. Available from: https://www.ukri.org/councils/mrc/facilities-and-resources/find-an-mrc-facility-or-resource/mrc-regulatory-support-centre/understanding-health-research/patient-and-public-involvement/#contents-list

- Cochrane Consumer Network. An international network on public involvement in health and social care research. [cited 2022 May 9]. Available from: https://consumers.cochrane.org/news/international_network

- Smits DW, Van Meeteren K, Klem M, et al. Designing a tool to support patient and public involvement in research projects: the Involvement Matrix. Res Involv Engagem. 2020;6(1):30. doi: 10.1186/s40900-020-00188-4.

- Banner D, Bains M, Carroll S, et al. Patient and public engagement in integrated knowledge translation research: are we there yet? Res Involv Engagem. 2019;5(1):8. doi: 10.1186/s40900-019-0139-1.

- van Bruinessen IR, van Weel-Baumgarten EM, Snippe HW, et al. Active patient participation in the development of an online intervention. JMIR Res Protoc. 2014;3(4):e59. doi: 10.2196/resprot.3695.

- Markle-Reid M, Ganann R, Ploeg J, et al. Engagement of older adults with multimorbidity as patient research partners: lessons from a patient-oriented research program. J Multimorb Comorb. 2021;11:2633556521999508. doi: 10.1177/2633556521999508.

- Diaz A, Gove D, Nelson M, et al. Conducting public involvement in dementia research: the contribution of the European Working Group of People with Dementia to the ROADMAP project. Health Expect. 2021;24(3):757–765. doi: 10.1111/hex.13246.

- National Health Service. Health Education England. Health literacy 'how to’ guide. [cited 2022 May 24]. Available from: https://library.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2020/08/Health-literacy-how-to-guide.pdf

- Keusch F, Rao R, Chang L, et al. Participation in clinical research: perspectives of adult patients and parents of pediatric patients undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2014;20(10):1604–1611. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2014.06.020.

- HealthTalk.org. Patient and public involvement in research. [cited 2022 May 9]. Available from: https://healthtalk.org/patient-and-public-involvement-research/overview

- Chakradhar S. Training on trials: patients taught the language of drug development. Nat Med. 2015;21(3):209–210. doi: 10.1038/nm0315-209.

- Allen D, Cree L, Dawson P, et al. Exploring patient and public involvement (PPI) and co-production approaches in mental health research: learning from the PARTNERS2 research programme. Res Involv Engagem. 2020;6(1):56. doi: 10.1186/s40900-020-00224-3.

- National Institute for Health and Care Research. Being inclusive in public involvement in health and care research. [cited 2022 May 24]. Available from: https://www.nihr.ac.uk/documents/being-inclusive-in-public-involvement-in-health-and-care-research/27365

- Boote J, Julious S, Horspool M, et al. PPI in the PLEASANT trial: involving children with asthma and their parents in designing an intervention for a randomised controlled trial based within primary care. Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2016;17(6):536–548. doi: 10.1017/S1463423616000025.

- Gwara M, Smith S, Woods C, et al. International Children’s Advisory Network: a multifaceted approach to patient engagement in pediatric clinical research. Clin Ther. 2017;39(10):1933–1938. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2017.09.002.

- Allsop MJ, Holt RJ. Evaluating methods for engaging children in healthcare technology design. Health Technol. 2013;3(4):295–307. doi: 10.1007/s12553-013-0062-7.

- Deal LS, Goldsmith JC, Martin S, et al. Patient voice in rare disease drug development and endpoints. Ther Innov Regul Sci. 2017;51(2):257–263. doi: 10.1177/2168479016671559.

- National Institute for Health and Care Research. INVOLVE. Involving children and young people in research: top tips for researchers. [cited 2022 May 24]. Available from: https://www.invo.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/involvingcyp-top-tips-January2016.pdf

- McNeil H, Elliott J, Huson K, et al. Engaging older adults in healthcare research and planning: a realist synthesis. Res Involv Engagem. 2016;2(1):10. doi: 10.1186/s40900-016-0022-2.

- Myers R, Anderson M, Korba C. Striving to become more patient-centric in life sciences. [cited 2022 May 9]. Available from: https://www2.deloitte.com/us/en/insights/industry/life-sciences/patient-centricity.html

- Faulkner SD, Sayuri Ii S, Pakarinen C, et al. Understanding multi-stakeholder needs, preferences and expectations to define effective practices and processes of patient engagement in medicine development: a mixed-methods study. Health Expect. 2021;24(2):601–616. doi: 10.1111/hex.13207.

- ICON. Paving the way for diversity and inclusion in clinical trials: establishing a platform for improvement. [cited 2022 May 24]. Available from: https://www.iconplc.com/insights/patient-centricity/diversity-and-inclusion-in-clinical-trials/diversity-and-inclusion-in-clinical-trials-whitepaper/

- National Health Council. Genetic Alliance. Patient-focused drug development recommended language for use in guidance document development. [cited 2021 Dec 22]. Available from: https://nationalhealthcouncil.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/NHC-GA%20Feb2017.pdf

- Madrid S, Tuzzio L, Stults CD, et al. Sharing experiences and expertise: the Health Care Systems Research Network workshop on patient engagement in research. J Patient Cent Res Rev. 2016;3(3):159–166. doi: 10.17294/2330-0698.1272.

- Jinks C, Carter P, Rhodes C, et al. Patient and public involvement in primary care research – an example of ensuring its sustainability. Res Involv Engagem. 2016;2(1):1. doi: 10.1186/s40900-016-0015-1.

- Raber-Johnson ML, Stinson M, Dillon C, et al. Key steps toward a promotional communications strategy: collaboration best practices for teams creating promotional materials and regulatory colleagues. Ther Innov Regul Sci. 2021;55(4):696–704. doi: 10.1007/s43441-021-00272-1.

- Patient Focused Medicines Development. The PFMD book of good practices. 3rd ed. [cited 2022 May 24]. Available from: https://patientfocusedmedicine.org/bogp/2020/the-book-of-good-practices.pdf

- Dewulf L. Patient engagement by pharma – why and how? A framework for compliant patient engagement. Ther Innov Regul Sci. 2015;49(1):9–16. doi: 10.1177/2168479014558884.

- Lowe MM, Blaser DA, Cone L, et al. Increasing patient involvement in drug development. Value Health. 2016;19(6):869–878. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2016.04.009.

- Tai-Seale M, Sullivan G, Cheney A, et al. The language of engagement: "Aha!" moments from engaging patients and community partners in two pilot projects of the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute. Perm J. 2016;20(2):89–92. doi: 10.7812/TPP/15-123.

- United Kingdom Standards for Public Involvement. Inclusive opportunities. [cited 2022 May 9]. Available from: https://sites.google.com/nihr.ac.uk/pi-standards/standards/inclusive-opportunities

- Vat LE, Ryan D, Etchegary H. Recruiting patients as partners in health research: a qualitative descriptive study. Res Involv Engagem. 2017;3(1):15. doi: 10.1186/s40900-017-0067-x.

- UyBico SJ, Pavel S, Gross CP. Recruiting vulnerable populations into research: a systematic review of recruitment interventions. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(6):852–863. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0126-3.

- Staniszewska S, Denegri S, Matthews R, et al. Reviewing progress in public involvement in NIHR research: developing and implementing a new vision for the future. BMJ Open. 2018;8(7):e017124. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017124.

- Baquet CR. A model for bidirectional community-academic engagement (CAE): overview of partnered research, capacity enhancement, systems transformation, and public trust in research. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2012;23(4):1806–1824. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2012.0155.

- Oliver S, Liabo K, Stewart R, et al. Public involvement in research: making sense of the diversity. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2015;20(1):45–51. doi: 10.1177/1355819614551848.

- Borup G, Bach KF, Schmiegelow M, et al. A paradigm shift towards patient involvement in medicines development and regulatory science: workshop proceedings and commentary. Ther Innov Regul Sci. 2016;50(3):304–311. doi: 10.1177/2168479015622668.

- Haerry D, Landgraf C, Warner K, et al. EUPATI and patients in medicines research and development: guidance for patient involvement in regulatory processes. Front Med (Lausanne). 2018;5:230. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2018.00230.

- National Academies of Sciences Engineering and Medicine, Policy and Global Affairs, Committee on Women in Science Engineering and Medicine, et al. Improving representation in clinical trials and research: building research equity for women and underrepresented groups. Barriers to representation of underrepresented and excluded populations in clinical research. Washington (DC). National Academies Press (US). [cited 2023 Jul 7]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK584407/

- Drug Information Association. Considerations guide to implementing patient-centric initiatives in health care product development. [cited 2022 May 24]. Available from: https://synapse.pfmd.org/resources/considerations-guide-to-implementing-patient-centric-initiatives-in-health-care-product-development/download

- Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute. Plain language principles. [cited 2022 May 24]. Available from: https://www.pcori.org/sites/default/files/2052-PCORnet-Plain-Language-Principles-Infographic.pdf

- Patients Included. Patient information resources. [cited 2022 May 9]. Available from: https://patientsincluded.org/patient-information-resources/

- Fagan MB, Morrison CR, Wong C, et al. Implementing a pragmatic framework for authentic patient–researcher partnerships in clinical research. J Comp Eff Res. 2016;5(3):297–308. doi: 10.2217/cer-2015-0023.

- Pfizer. The newest vital sign. [cited 2022 May 24]. Available from: https://www.pfizer.com/products/medicine-safety/health-literacy/nvs-toolkit

- Pfizer. Health literacy. [cited 2022 Aug 4]. Available from: https://www.pfizer.com/health/literacy/healthcare-professionals

- Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry. Health jargon buster: an A to Z guide: Scotland. [cited 2022 May 23]. Available from: https://www.abpi.org.uk/media/jojevzyp/abpi-scotland-jargon-buster.pdf

- Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry. Health jargon buster: an A to Z guide: Wales. [cited 2022 May 23]. Available from: https://www.abpi.org.uk/media/afvjxexq/abpi-cymru-wales-jargon-buster-2021.pdf

- United States National Institutes for Health. Glossary of common terms. [cited 2022 May 23]. Available from: https://www.nih.gov/health-information/nih-clinical-research-trials-you/glossary-common-terms

- United States National Cancer Institute. NCI dictionary of cancer terms. [cited 2022 May 23]. Available from: https://www.cancer.gov/publications/dictionaries/cancer-terms

- European Patients’ Academy on Therapeutic Innovation. Toolbox. [cited 2022 May 23]. Available from: https://www.toolbox.eupati.eu/

- Patients Active in Research and Dialogues for an Improved Generation of Medicines. PARADIGM patient engagement toolbox. [cited 2022 May 23]. Available from: https://imi-paradigm.eu/petoolbox/

- National Institute for Health and Care Research. INVOLVE. Guidance on co-producing a research project. [cited 2022 May 23]. Available from: https://www.invo.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Copro_Guidance_Feb19.pdf

- Haynes D, Hughes KD, Okafor A. PEARL: a guide for developing community-engaging and culturally-sensitive education materials. J Immigr Minor Health. 2023;25(3):666–673. doi: 10.1007/s10903-022-01418-5.

- European Patients’ Academy on Therapeutic Innovation. Welcome to EUPATI Open Classroom! [cited 2022 Jun 10]. Available from: https://learning.eupati.eu/

- European Patients’ Academy on Therapeutic Innovation. Your questions answered – patient engagement trainings. [cited 2022 May 24]. Available from: https://eupati.eu/news/your-questions-answered-patient-engagement-trainings/

- Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute. Research fundamentals: preparing you to successfully contribute to research. [cited 2022 May 24]. Available from: https://www.pcori.org/engagement/research-fundamentals

- Kirwan JR, de Wit M, Frank L, et al. Emerging guidelines for patient engagement in research. Value Health. 2017;20(3):481–486. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2016.10.003.

- Gaasterland CMW, Jansen-van der Weide MC, Vroom E, et al. The POWER-tool: recommendations for involving patient representatives in choosing relevant outcome measures during rare disease clinical trial design. Health Policy. 2018;122(12):1287–1294. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2018.09.011.

- Caeyers NP. SP0219 patient involvement in research: Flemish training of 18 patient research partners. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73(Suppl 2):56.3–56. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-eular.6319.

- Imperial College London. Public involvement training. [cited 2022 May 24]. Available from: https://www.imperial.ac.uk/patient-experience-research-centre/ppi/ppi-training/

- European Patients’ Academy on Therapeutic Innovation. EUPATI fundamentals. [cited 2022 May 24]. Available from: https://eupati.eu/eupati-fundamentals/

- European Patients’ Academy on Therapeutic Innovation. EUPATI essentials. [cited 2022 May 24]. Available from: https://eupati.eu/eupati-essentials/

- Patient Engagement Management Suite. Patient engagement training. [cited 2022 May 24]. Available from: https://pemsuite.org/patient-engagement-training/

- Patient Engagement Management Suite. Practical how-to guides for patient engagement. [cited 2022 May 24]. Available from: https://pemsuite.org/how-to-guides/

- Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute. Patient engagement toolkit. [cited 2022 May 24]. Available from: https://www.pcori.org/engagement/engagement-resources/Engagement-Tool-Resource-Repository/patient-engagement-toolkit

- Malm C, Jönson H, Andersson S, et al. A balance between putting on the researcher’s hat and being a fellow human being: a researcher perspective on informal carer involvement in health and social care research. Health Res Policy Syst. 2022;20(1):135. doi: 10.1186/s12961-022-00946-8.

- Boylan AM, Locock L, Thomson R, et al. “About sixty per cent I want to do it”: health researchers’ attitudes to, and experiences of, patient and public involvement (PPI) – a qualitative interview study. Health Expect. 2019;22(4):721–730. doi: 10.1111/hex.12883.

- Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute. Social Media and Research Toolkit (SMART). [cited 2022 May 24]. Available from: https://www.pcori.org/research-results/2016/social-media-and-research-toolkit-smart

- National Institute for Health and Care Research. Clinical Research Network. [cited 2022 May 24]. Available from: https://www.nihr.ac.uk/explore-nihr/support/clinical-research-network.htm

- PCORNet. Network. [cited 2022 May 24]. Available from: https://pcornet.org/network/

- European Patients’ Academy on Therapeutic Innovation. EUPATIConnect. [cited 2022 May 24]. Available from: https://connect.eupati.eu/

- European Patients’ Academy on Therapeutic Innovation. National Platforms. [cited 2022 May 24]. Available from: https://eupati.eu/eupati-national-platforms/

- Patient Engagement Management Suite. Patient engagement synapse. [cited 2022 Jun 24]. Available from: https://pemsuite.org/synapse/

- ForPatients by Roche. Welcome to ForPatients. [cited 2022 May 24]. Available from: https://forpatients.roche.com/

- Shippee ND, Domecq Garces JP, Prutsky Lopez GJ, et al. Patient and service user engagement in research: a systematic review and synthesized framework. Health Expect. 2015;18(5):1151–1166. doi: 10.1111/hex.12090.

- Goel N. Conducting research in psoriatic arthritis: the emerging role of patient research partners. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2020;59(Suppl 1):i47–i55. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kez338.

- Smith J, Damm K, Hover G, et al. Lessons from an experiential approach to patient community engagement in rare disease. Clin Ther. 2021;43(2):421–429. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2020.12.002.

- Squires A, Sadarangani T, Jones S. Strategies for overcoming language barriers in research. J Adv Nurs. 2020;76(2):706–714. doi: 10.1111/jan.14007.

- Willis A, Isaacs T, Khunti K. Improving diversity in research and trial participation: the challenges of language. Lancet Public Health. 2021;6(7):e445–e446. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(21)00100-6.

- Carbó PA, Ahumada MAV, Caballero AD, et al. “How do I do discourse analysis?" teaching discourse analysis to novice researchers through a study of intimate partner gender violence among migrant women. Qual Soc Work. 2016;15(3):363–379. doi: 10.1177/1473325015617233.

- Evans-Agnew RA, Johnson S, Liu F, et al. Applying critical discourse analysis in health policy research: case studies in regional, organizational, and global health. Policy Polit Nurs Pract. 2016;17(3):136–146. doi: 10.1177/1527154416669355.

- Starks H, Trinidad SB. Choose your method: a comparison of phenomenology, discourse analysis, and grounded theory. Qual Health Res. 2007;17(10):1372–1380. doi: 10.1177/1049732307307031.

- Zimmermann A, Pilarska A, Gaworska-Krzemińska A, et al. Written informed consent-translating into plain language. A pilot study. Healthcare (Basel). 2021;9(2):232. doi: 10.3390/healthcare9020232.

- Myeloma Patients Europe, WeCan, Patient Focused Medicines Development. Guiding principles on reasonable agreements between patient advocates and pharmaceutical companies. WECAN – final consensus document. [cited 2022 Aug 8]. Available from: https://patientengagement.synapseconnect.org/resources/guiding-principles-on-reasonable-agreements-between-patient-advocates-and-pharmaceutical-companies-1/download

- The Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry. Principles for working together. [cited 2023 Jul 17]. Available from: https://www.abpi.org.uk/partnerships/working-with-patient-organisations/working-with-patients-and-patient-organisations-2022-sourcebook-for-industry/principles-and-agreements/

- Plain English Campaign. Plain English Campaign. [cited 2023 Jul 17]. Available from: https://www.plainenglish.co.uk/index.php

- Versus Arthritis, Parkinson’s UK, Cystic Fibrosis Trust, et al. From transactional to truly collaborative: improving relationships between industry and patient organisations. [cited 2023 Jul 17]. Available from: https://www.versusarthritis.org/media/25664/improving-relationships-industry-patient-report.pdf

- Harrison JD, Auerbach AD, Anderson W, et al. Patient stakeholder engagement in research: a narrative review to describe foundational principles and best practice activities. Health Expect. 2019;22(3):307–316. doi: 10.1111/hex.12873.

- Stoner AM, Cannon M, Shan L, et al. The other 45: improving patients’ chronic disease self-management and medical students’ communication skills. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2018;118(11):703–712. doi: 10.7556/jaoa.2018.155.