ABSTRACT

During the last decade, there has been an unprecedented increase in the number of Syrian asylum seekers, including forced displaced academics (FDAs), in Turkey. Along with providing essentials, there is the issue of social integration for these people. To efficiently deal with this problem, Turkish authorities have developed both educational policies and some legal arrangements to accommodate the employment process for FDAs. This study aims to investigate Turkey’s higher education policy for FDAs by examining the lived experiences of these academics based on political, social, and cultural dynamics. The findings illustrate major themes surrounding the academic identity of FDAs and what distinguishes them from other international academics, as well as their experiences in the Turkish higher education system, and the challenges they have faced. The study provides important implications for the purpose of generating effective policies and practices regarding the successful integration of FDAs into the higher education system both in Turkey and worldwide.

Introduction

The Arab Spring upheavals in the Middle East sparked an outbreak of a war in Syria, causing millions of people to flock towards neighbouring countries. As one of the closest safe zones, Turkey has witnessed an unprecedented rise in the number of asylum seekers for almost a decade (Erdoğan, Citation2019). According to the authorities, there are 3,675,485 Syrian asylum seekers in Turkey under temporary protection (Directorate General of Migration Management, [DCMM], Citation2021, making Turkey the country with the largest number of Syrians outside of Syria itself (UNHCR, Citation2018). Individuals who are rich in knowledge and skills, such as academics, have also taken shelter in Turkey among these large migrant groups (İnce, Citation2019). Therefore, there appears an urgent need to develop precautionary financial, social, and educational tools to address the problem of forced displacement for this group (Arar et al., Citation2020).

As the number of ‘forced displaced academics’ (FDAs) in the Turkish higher education system has grown in parallel with the numbers of migrants, the issue of integrating these professionals into the higher education system has arisen. Policymakers have developed several policies to facilitate employment procedures for FDAs. For instance, the International Labour Force Law (ILFL) was passed in 2016, regulating working conditions and permits for all migrants, yet it exceptionally targets high-skilled individuals including international academics and FDAs (Directorate General of Migration Management, [DCMM], Citation2017). This law employs a selective policy on migrant qualifications to determine who would be allowed to work in Turkey. Section IV of the act identifies certain types of foreigners including international academics, doctors, and investors eligible for exceptional work permits which could be extended upon a renewed application. As an extension of this act, Turkish authorities also started granting high-skilled people with a special ‘Turquois Card’, which, in practice, resembles American Green Card or European Union Blue Card, only given to those who ‘ … have internationally recognized studies in the academic area, and those distinguished in science, industry, and technology … ’ in article 11/5 of ILFL. Besides, Turquois Card holders are exceptionally granted Turkish citizenship upon the approval of the Council of Ministers, provided that they do not pose any threat to national security and public order (Çelik, Citation2017). In a broader sense, Turkish authorities passed this regulation as part of the policies integrating high-skilled people into a larger societal setting, with the purpose of creating desirable working conditions by facilitating exceptional work permits and citizenship opportunity.

An additional step taken in the context of Turkish higher education is the establishment of the Foreign Academic Information System (FAIS), which was initially organised for the employment of Syrian academics and later broadened to include academics from other countries (Council of Higher Education [CoHE], Citation2017). In the ensuing years, the CoHE (Citation2020) issued new requirements for international academics, such as scholarly publication of either a book or five articles and having a year of work experience to increase the quality of international academics in the system. This new regulation also requires FDAs to meet the requirements in two semesters (12-month period), otherwise their contracts will not be renewed. Yet, prior to this regulation, it was deemed sufficient for those employed in language preparatory schools having a BA and for those at faculties holding a PhD degree to give lectures and, therefore, many universities did not require job experience or scholarly publishing prerequisites (CoHE, Citation2020). Following the ILFL, the CoHE (Citation2020) noted unequivocally that international academics cannot be paid any additional funds from the revolving fund, which covers the expenses for extra classes and summer schools. This regulation also governs the labour contracts for international academics by authorising universities to decide upon the duration between at least three months and two years at most. Additionally, another challenge refers to the law on higher education personnel. According to article 16 of the law, the number of international academics on contracts cannot exceed 2% of the total number of Turkish academics (CoHE, Citation1983). With the legislation, the CoHE has restricted the number of international academics, thereby limiting potential job opportunities for them (Şeremet, Citation2015). Although the ILFL seemed to enable international academics including FDAs with Turquois Cards, exceptional work permits and citizenship, the current regulations issued by the CoHE pose risks to their job security impacting the quality of life and well-being of these people. FDAs working as Arabic instructors in theology faculties, in particular, are on the verge of losing their jobs, as the majority of them only hold a B.A. and cannot match the above-mentioned qualifications. Due to the issues described above, there is a need for more sound and comprehensive higher education policies aimed at providing FDAs with better settlement, integration, and employment opportunities. However, there is paucity of research to inform relevant policy and practice regarding FDAs (Arar et al., Citation2019; Council for At-Risk Academics [CARA], Citation2019; Erdoğan & Erdoğgan, Citation2018; Universities UK International [UUKI), Citation2018), which causes Turkey’s policy initiatives to remain as reactionary and instituted as short-term precautionary principles. Against this backdrop, our study focuses on the current conditions and issues for FDAs at Turkish universities, in an effort to capture a better understanding of their needs and the challenges they face in the process of being integrated within the Turkish higher education system. Results may also promote further discussion on what the international community can do to improve conditions for FDAs and illuminate key lessons to be learned from the Turkish case. Thus, the present research aims to analyse the Turkish higher education policy for FDAs by examining their lived experiences, explaining current conditions, and describing pushing and pulling factors behind their choice to resettle in Turkey. More specifically, we aim to answer the following research questions:

What does it feel like to be a forced displaced person?

What does being an academic mean for FDAs?

Which HE policies have been developed regarding FDAs in the Turkish higher education system?

What are the experiences of FDAs in Turkish higher education institutions?

Forced displaced academics (FDAs)

Located at the junction of Asia, the Middle East, and Europe, Turkey has experienced increasing mass migration inflows over the last century and has become a safe harbour for millions (Arar et al., Citation2020). In particular, since the outbreak of the war in Syria, not only ordinary or poorly educated civilians but also highly trained individuals including academics have been forcibly displaced and migrated to Turkey from the Middle East (İnce, Citation2019). In this study, we operationally define these scholars as ‘forced displaced academics’ instead of migrants, immigrants, refugees, or asylum seekers to differentiate them from other international academics in the Turkish higher education system. This conceptualisation has a theoretical basis since the terms ‘migrant’ and ‘immigrant’ are mainly used for people who migrate for economic reasons, rather than political or social rationales such as inner turmoil or security concerns (Özkan, Citation2013). Therefore, they do not fit well to describe this particular group. Neither is it appropriate to use the other term ‘refugee’ because Turkey, as a signatory (with territorial limitation) of the 1951 Geneva Convention, recognises only refugees from European countries, thus it does not grant refugee status to those arriving from the East (Kaya & Yılmaz Eren, Citation2015). In addition, the reason that the term ‘asylum seeker’ is not preferred is because it typically refers to people who have applied for refugee status but whose claim has not yet been determined (Özkan, Citation2013). A final reason for this conceptualisation is that Turkey has only given Syrians ‘temporary protection status’, which grants Turkey the legal right to deport these people back to their own country or to a third country (Kaya & Yılmaz Eren, Citation2015).

Theoretical framework

Internationalisation in higher education (IHE) has grown more rapidly in recent years, thereby becoming a policy priority. In this sense, higher education institutions (HEIs) have been internationalising for a variety of reasons; yet research in this area only concentrated on certain dimensions. Larsen (Citation2013) categorises the available literature on IHE into three major frameworks: strategies (strategy forms, practices, and initiatives), locations (internationalisation at home or abroad), and motivations (rationales). Various studies on IHE also suggest at least three other frameworks that could be incorporated into Larsen’s categorisation. The first is the ‘conceptual’ framework, which defines and traces key terms such as globalisation, intercultural, and multicultural education; the second is the ‘critical’ framework, which provides literature on the IHE’s benefits, opportunities, and challenges, while the third is the ‘students’ framework, which details the results of studies on international and domestic students’ experiences and perceptions (Khorsandi Taskoh, Citation2014).

Despite this centrality of IHE studies, there remain some important aspects that need to be brought to the fore of IHE research and policymaking. Arar et al. (Citation2020) indicate that higher education for displaced people should be prioritised in IHE policies due to its growing importance with the increasing numbers of international migrants, as well as its mitigating role for forcible displacement. We therefore grounded our study in IHE theory, blending it into this new area of research for IHE, which holds potential to provide deeper insight into FDAs’ unique experiences in host countries’ HEIs. However, the lived experiences of forced displaced people require another theoretical perspective to channel our efforts to understand the prevailing factors for migration. Therefore, we consulted international migration theories (Massey et al., Citation1993), both to clarify our conceptualisation of FDAs and to explain the rationales behind their choice of Turkish HEIs.

The factors affecting migration are generally classified as push-pull factors (World Economic Forum, Citation2017). Positive features of a place that attract people are called pull factors, while the negative features that force people to move away are considered push factors. Push factors include poverty, unemployment, unsustainable livelihoods, political instability, security concerns (such as ethnic, religious, racial, or cultural persecution), conflict or threats, slavery or forced labour, inadequate or limited urban service and infrastructure (such as health, education, public services, and transportation), climate change (including natural disasters), crop failure, and food shortages. Pull factors include better job opportunities, hope for better income, family reunification, independence and individual freedom, food security, affordable and accessible urban services (including health, education, public services, and transportation), abundance of natural resources and minerals (e.g. water, oil, uranium), and favourable climate conditions (World Economic Forum, Citation2017).

Several factors could explain the fact that millions of people are choosing Turkey as a final destination or temporary shelter before European nations. First, Turkey has a very strategic location, which makes it a suitable place for migration (İçduygu & Keyman, Citation2000). Second, Turkey has ties of culture, ethnicity, history, and religion with related communities in Central Asia, the Caucasus, the Balkans, and the Middle East. Therefore, it is regarded as a preferable destination for immigrants in times of political and regional crises (Kondakci & Onen, Citation2019). As has happened in the case of Syrian asylum seekers, which are by far the largest group of forced displaced people, Arar et al. (Citation2020) stress that the main reasons behind Syrians’ decision to migrate to Turkey are to avoid the raging war in northern Syria (Bélanger & Saracoglu, Citation2019) and to flee to Western Europe (Watenpaugh etal., Citation2014).

Method

Research design

Employing a phenomenological research design (Creswell, Citation2012), this study explores the lived experiences of FDAs in the Turkish higher education system. The basic purpose of a phenomenological study is to ‘reduce individual experiences with a phenomenon to a description of the universal essence’ and to understand in depth ‘what they have experienced’ and ‘how they experienced it’ (Creswell, Citation2013, p. 76). As the study seeks to understand the current situation from the point of view of people who have experienced it, this approach was deemed effective for understanding the perspectives of FDAs and their first-hand experiences in Turkish HEIs.

Participants

The study sample consists of 10 FDAs working at a university in western Turkey. Working in various departments, participants were selected using a snowball purposive sampling technique (Patton, Citation2002), where researchers used the FDAs’ communication network to find suitable participants. We utilised several strategies to obtain trust and build rapport to generate rich and insightful data. In building rapport, the first author took advantage of his personal friendship and good communication with the first participant as they have been working in the same department for more than a year. This good relationship and trust resulted in easily obtaining the trust of other participants as FDAs were all in close contact with one another. Over these favourable connections, anticipating the participants' needs and maintaining consistent contact got easier, which helped researchers build rapport. Besides, each interviewee was granted anonymity and told by the researcher about the purpose of the study (Creswell, Citation2012). Even though the researchers and interviewees are from the same institution, nine of the interviewees work in different departments than the researchers. Furthermore, both researchers in the study are male and Turkish, and neither hold any superior positions which could either create power imbalance intimidating interviewees to talk freely or jeopardise the data collection procedure and trust between the researchers and interviewees.

We also used criterion-based purposive sampling to select participants, who had spent at least two academic periods at a Turkish university (Patton, Citation2002). The demographic characteristics of the participants are given in.

Table 1. Participants’ profile

As seen in, all of the participants in the present study were male, with ages ranging from 38 to 60. Six participants were from Syria, three were from Iraq, and one was from Palestine. Half of the participants were employed in the Theology Department at the university, while others were employed in various departments such as Western Language and Literature, Engineering, and English Language Teaching. Three participants held the rank of assistant professor, one was a full professor, one was an associate professor, and the remaining five were lecturers. The duration of the participants’ stays in Turkey ranged from 1.5 to 6 years.

Instrumentation and procedure

In this study, we used a semi-structured interview form and face-to-face interviews to gather data (Marshall & Rossman, Citation2016). The interview form was composed of nine questions grouped under six categories: demographic information, reasons for choosing Turkey, challenges that FDAs face in obtaining access to the Turkish higher education system, FDAs’ needs during the employment process, factors affecting their academic performance, and evaluation of the Turkish higher education system and other services and infrastructure provided to FDAs. The interviewees and researchers are both affiliated with the same university. The Ethical Review Committee of the Institution provided approval for the research before data collection began. After reading and signing an informed consent form in English and Arabic, all participants permitted audio recording before the interviews. The interviews were conducted by the researchers, with an Arabic-Turkish translator when needed. Each interview was conducted individually on a separate day, in a place where each participant agreed to meet up, and lasted approximately 45–60 minutes. Since the researchers received their B.A. in an ELT department and four participants were from the Western Language and Literature department and fluent in English, these interviews were conducted in English. One participant, of Turkish descent but born and raised in Syria, spoke Turkish and Arabic fluently and assisted as a translator during the interviews with the other speakers of Arabic. Besides, all interviewees have been in Turkey for at least 1.5 to 6 years at the time of the study and, therefore, were competent enough at understanding basic Turkish, which greatly aided our communication.

Data analysis

In this study, we followed the qualitative content analysis process proposed by Creswell (Citation2012, p. 237). This process starts with preparing the collected data for analysis and continues with reading through the raw data. The data is then coded by locating text segments and assigning them code labels. The process ends with the text being coded for themes to be mentioned in the research report. Therefore, we transcribed audio recordings verbatim. Then, the transcribed data set was sent to each participant for member checks to ensure that their responses to the interview questions reflected their experiences (Creswell, Citation2012). To build a general sense of understanding, the entire data set was read several times by each researcher. One of the researchers then prepared the first code list by marking and categorising each piece of data with a representative code. Using this initial code list, another researcher then coded the interviews. If a piece of data was not represented by any codes in the list, a new code was formed, and this process was repeated until no new codes were introduced (to ensure saturation). Common codes were then pooled, and major themes were identified.

Findings

The FDAs who participated in this study were asked about how they made sense of being an academic in the Turkish higher education system where higher education policies had been developed regarding FDAs, and what they experienced in the system as an FDA. Findings yielded three major themes, each with several categories.

The nature of being an FDA

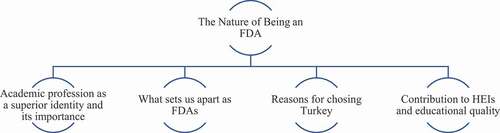

The first major theme that originated from participants’ responses aimed to unveil the nature of being an FDA and what distinguishes them from other international academics. This broad theme yielded several categories, as seen in .

The academic profession as a superior identity and its importance

The first category focuses on the meaning that participants attributed to their academic identities. The vast majority of the participants considered themselves to be an academic and considered their profession as a superior identity. One of the participants explains:

I am proud of my academic identity and I consider this profession is superior to all other professions because this profession is the seed, the beginning and the ancestor of other professions and whatever seed you plant in the community, it grows. (P8)

Some participants defined being an academic from a fundamentally similar but individual perspective. The disparity in meanings might stem from different interpretations of their roles depending on the nature of academia in their respective fields. Accordingly, one of the participants expressed:

I consider being an academic as a sacred duty, after all, this profession is a prophetic profession, and we reveal the ore within people. (P2)

When establishing their own professional identity, participants articulated some ideas related to their profession, such as its basic functions, the ability to contribute to society, raising future generations, a sacred profession, ancestor of other careers, prophetic profession, and serving as an inspiration for students. One of the participants expresses his views as follows:

Being an academic is an incredibly difficult and committed career. You are not just teaching the content of the course while you are in class but becoming an inspirational role model for your students. You have the ability to influence their lives, to help them settle with their personality. You do want to instill a sense of curiosity about what you are doing in your classes. (P3)

This expression mostly accords with the basic principles of Higher Education Law of Turkey (CoHE, Citation1981), which identifies that all faculty members, including FDAs, are primarily expected to provide instruction related to their field of expertise across undergraduate, graduate, and postgraduate levels. It seems that participants first and foremost tend to define themselves as an academic, and they consider their profession as a superior identity. Within the framework of this identity, they perceive the basic functions of their career as providing a service to society, being an inspirational role model, influencing future generations, conducting research, and producing scientific knowledge.

What sets us apart as FDAs

Another component of the first major theme stems from participants’ need to identify themselves from a perspective that differs from their Turkish-born peers. The overwhelming majority of them demonstrate that they have distinguishing features from other international academics, as articulated through their narratives. This shared experience coalesces around these two unique features of the research group: (1) they have recently entered Turkish HEIs from countries with similar circumstances, and (2) they left their home countries due to various push factors. Accordingly, most participants claim that they differ from other international academics because they have been forced to flee their homeland, thereby identifying themselves as forced displaced academics (FDAs). In addition to the participants’ own self-categorisation as FDAs, they also discussed the factors contributing to this definition, such as their main reasons for choosing Turkey, the circumstances that caused them to leave their homeland, and how they know they are an FDA. One participant accordingly explains:

I love my country very much, but for obvious reasons, I had to leave. Thank God I am very happy here, but I believe that the day will come sooner or later, and I can get back home. (P3)

Similarly, another participant expressed his painful experiences and security risks that forced him to leave:

They abducted me during the sectarian war in my country, I do not want to tell the details about my experiences, but I have a family, I have children, their safety was more important than anything. For the very reason, I am here. (P7)

Reasons for choosing Turkey

Most participants shared their deep-down sorrow of being forced to leave their homeland, mainly due to push factors such as security issues, inner turmoil, and political instability. Yet, they did not seem to have lost hope of returning. Most participants underlined the fact that they had to leave their country, even though they would not have chosen to leave in easier circumstances. In order to provide more detailed explanations of the driving factors behind their displacement, some participants shared that, at first, they had to leave their country with a hope of return due to the war, but later the war escalated, and they could not return home. One participant expressed his opinions in this regard:

I went to Jordan, Dubai and Saudi Arabia before I came here, they looked at you differently, if you’re not a citizen, you’re not respected and you’re treated as second-class citizens, but there’s no such thing here. (P2)

With the aforementioned narratives, participants highlighted the reasons behind their choice of Turkey over Saudi Arabia and other Gulf countries, where they claim there is prejudice or discrimination against them. They point out that Turkey has been a friendly nation and largely meets their needs. One participant shared his thoughts as follows:

I think Turkey is quite a developed country, where you will find a combination of both West and East, a natural bridge for ages. Frankly, Turkey is a kind of European country, it is much better to be here than in any Arabic country. (P5)

Contribution to HEIs and educational quality

Some participants mentioned that their presence in the Turkish higher education system has generated some potential increases in the quality of education at their institution. Accordingly, one participant described their contribution as follows:

International academics are people who can bring a different taste and texture to the country they are located in. I believe our being here is improving the quality of education. For someone who has already written in the most respected engineering journals, I work in the same way here and I hope I will be having better publications here. Besides all, I am trying to instill my students with the love of science. (P2).

Participants believed that their assets contributed significantly to the Turkish higher education system. It can therefore be assumed that the participants feel they are adding an international dimension to Turkish HEIs, playing a substantial role in improving educational standards.

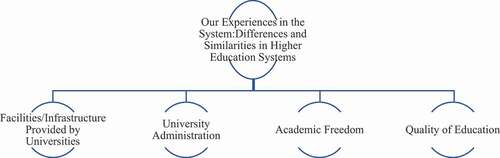

Our experiences in the system: differences and similarities in higher education systems

The second major theme reflects a comparative analysis of the Turkish higher education system and the higher education systems in the participants’ countries. The participants described their experiences in the Turkish HEIs and established a sense of compatibility with their past experiences, both interpreting and comparing the systems from their own perspectives. It is worth noting that, in addition to revealing their opinions on the Turkish higher education system, the participants’ comparisons revealed several notable categories: the facilities/infrastructure provided by universities, features of Turkish university administration, academic freedom, and the quality of education. These categories are shown in .

Facilities/infrastructure provided by universities

The first point that draws attention in this theme was that some participants could not make a definitive comparison regarding the current situation of the HEIs in their own country. Particularly, a few Syrian participants emphasised that the ongoing war in the country has not only forced many academics to move, but also ruined the entire higher education system, causing the deterioration of the economy and the destruction of infrastructure, making it unfair to compare higher education systems. One participant stated:

… to make a comparison between Turkish and Syrian HE systems is almost impossible. In Syria, the school quality has dropped significantly because many of us had to leave the country. In today’s circumstances, Turkey is in every way much better than Syria. (P9)

However, a few participants drew comparisons between their home HEIs and those in Turkey. These participants mostly focused on the superior facilities and infrastructure offered by Turkish HEIs. In this vein, many participants were aware of Turkey’s economic power and claimed that they had greater access to facilities and resources in Turkish universities. One participant shared his views on this issue as follows:

… . when I started here, they gave me my room immediately and then brought a laptop in a week. In my country, there is a lot of paperwork, you have to wait for ages. I waited a year to get a room, I do not even remember how long to get a computer. The internet service here is exceptional, the infrastructure in the building should be quite new. Under these conditions, I am more motivated to work. (P7)

University administration

Multiple participants expressed salient experiences with the administration at their old universities. Some of them detailed their experiences as follows:

If you are not a state partisan, you’re never given the chance to be a manager. They just appoint someone according to how they want him to manage, not as per his qualifications (P2)

… in my country people have long been under pressure, so if there is oppression how can you talk about democracy? The university administration is no exception, they are also puppets of the regime. (P5)

The participants generally indicated that they were not pleased with their home countries’ governments and their authoritarian administrative actions, which also emerged in HE administrations. Participants tend to view the administration of Turkish HEIs as transparent, and therefore more inclusive, and welcoming. One participant from Palestine reflects his ideas as follows:

Palestinian administration is much tougher, and there are more rules. There is a very bad attitude about obtaining permission to go abroad. Faculty administrators are more authoritarian in my country. Here, they help and make my work easier. (P6)

Academic freedom

In general, the academics’ narratives revealed not only pressure in their home countries, but also limits on freedom and resources. Participants explained that they had little autonomy or academic freedom, and the processes they had to undergo to perform scientific research were difficult and arduous. One participant explained his experiences as follows:

… universities and academics in Turkey have better facilities. Academic publishing is much more developed and simpler here. There are formations courses such as Dergi Park and YÖK thesis. Systems are integrated, but nothing is that easy in my country. If you want to do research, it is not clear how long you’re going to wait for permission. (P8)

In a more striking statement, one participant added:

There is no academic freedom or the freedom of speech in Syria since the intelligence service is very strong, and even an intelligence agent can arrest a rector if necessary. I do not feel the pressure here, I can conduct scientific research without feeling that terror. (P2)

Quality of education

The participants claimed that the standard of education in Turkey is reasonably good, with wider opportunities and facilities provided to the students. One of the participants expressed his ideas thusly:

I think it is pretty decent facilities provided to students in Turkey. I would also like to note that the academics with whom I work are professional. (P5)

Some participants evaluated university teaching based on quality assurance and the presence of international students. One of them expressed his ideas intimately:

In my country’s universities, students do not have the opportunity to benefit from international exchange programs such as Erasmus and Mevlana. Only rich people within a certain group close to the government have the opportunity to send their children to study abroad, but the others don’t have this opportunity (P1)

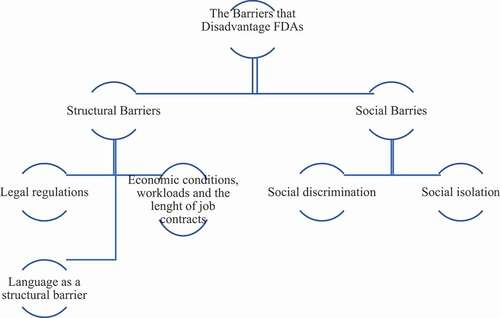

The barriers that disadvantage FDAs

The participants were asked about the barriers that they have experienced in Turkish HEIs, which forms the third major theme. We classified the findings under two broad themes: structural and social barriers (see ).

Structural barriers

Legal regulations

The majority of the participants stated that they had faced problems regarding the legal regulations around their work permits at Turkish HEIs. Some participants pointed out the problem as follows:

Many of our friends want to leave Turkey because they have obtained citizenship and their jobs are now terminated. Something needs to be done for these people. There should be an Arabic version of this ALES exam to facilitate job requirements, or these people should be tested from their own field. (P10)

I am afraid of losing my job if Turkey takes me as a citizen. I just want to have job security and work more comfortably. I don’t want to work on a temporary and short-term contract. (P4)

Most of the participants celebrated being given the privilege to obtain Turkish citizenship, but more of their time in interviews was devoted to criticising the legal regulations surrounding employment requirements. These participants indicated that the law requiring them to provide a score from the Academic Personnel and Graduate Studies Exam [ALES in Turkish] should be changed, or they should be given an exceptional status to work for Turkish universities as Syrian academics.

Economic conditions, workloads, and the length of job contracts

Other challenges that participants faced included economic conditions, workload, and the length of their job contracts. Some participants expressed displeasure about their salaries, and not having the opportunity to work for summer schools.

I’m making more money here than I do in my country, but it’s not enough for the basic needs. I have not made any savings yet for my family. However, we do not get a chance to work in the summer school, even though we are willing to work more. (P9)

Another participant referred to the length of job contracts:

Our job contract will be longer, because after it’s finished all the paperwork needs to be done again. Universities will immediately extend the contract and continue to work with the instructor they want. Otherwise, I would not want to witness the same vicious cycle again and again. I want to rid myself of this formality. (P7)

Language as a structural barrier

Along with the challenges mentioned above, some participants claimed that they experienced language barrier with the official documents.

I couldn’t speak Turkish when I first started school, but now I can communicate in it. Official documentation is still tough for me, and I sometimes need assistance of Turkish academics fluent in Arabic.’(P10)

Similarly, another participant stated,

Since most official documents are in Turkish and the school lacks personnel capable of speaking neither English nor Arabic, I constantly seek assistance from my students. (P8)

Social barriers

Social discrimination

The majority of the participants stated that they did not encounter any discrimination at work:

When I first arrived, I was a little afraid, but now I understand I see that the Turkish people are not treating us badly. On the contrary, they show more respect when they say that I am a professor at university. (P2)

However, a few expressed that they have faced some sort of social discrimination:

One night my little daughter had a toothache, and I took her to the hospital. The doctor there first spoke Turkish to me and then started to shout when she realized I did not understand her. I said I could speak English, and I tried to explain my problem, but the doctor called security and they took us out, which made me very upset. I had to go to the hospital the next day. (P8)

A shopkeeper didn’t respond to me as I didn’t speak Turkish and asked me to leave his store and I never forget the day. (P4)

Social isolation

Language emerged as another important social barrier. A few outlined the problem as follows:

I can say that the issue that challenges me and my family the most is the Turkish language. (P9)

Because of the language barrier my daughter feels resented as she has this difficulty in making friends at school and my wife also highlights that she is only in close contact with other Arab women. (P5)

Under this broad theme, participants noted that they have experienced a number of uncertainties related to job contracts and faced economically challenging conditions. They also reported that language emerges as an element that challenges them both in work and social life. Overall, our findings suggest that living and working in precarious situations proves to have negative effects on varying sides of their life.

Discussion and conclusion

The present study aimed to examine Turkey’s higher education policy for FDAs by analysing their lived experiences based on the political, social, and cultural dynamics that have shaped them. Results revealed that participants identified themselves as academics and described their profession as a superior identity. Within the framework of the basic functions of their career – such as serving society, being a role model, influencing future generations, teaching, conducting research, and producing scientific knowledge – these participants made sense of their professional identity in a new national and educational context. Participants also prioritised their professional identity and regard it as an important tool for bringing universal values to society. Hayden et al. (Citation2003) stated that internationalisation in higher education serves as a structure to support the socio-cultural and intellectual development of students as well as democratic values, beliefs, and cultural diversity. It can also be assumed that FDAs are adding an international dimension to the higher education institutions in the country, and that they serve an essential role in improving educational standards. Similarly, Teichler (Citation2009) emphasises that international academics contribute to the quality of education and cultural diversity in the countries where they are located, thus increasing the international recognition of their universities.

Results illustrated that participants shared some common characteristics and articulated that they had distinguishing features from other international academics. Most participants claimed that since they have been forced to leave their homeland due to push factors such as wars, political instability and security concerns, they differ from other foreign academics, thereby describing themselves as forced displaced academics (FDAs). Results also indicate that they feel agony for being forced to leave their countries. Respectively, this result resonates with the linked concepts of push and pull factors (World Economic Forum, Citation2017). In terms of push factors, participants feel the grief of their traumatic experiences and being forced to leave their homeland. The pull factors behind their choice of Turkey include its locational proximity; cultural, ethnic, and religious ties; low level of discrimination; strength as a Middle Eastern nation; and its implementation of an open-door policy for asylum seekers. Therefore, these push and pull factors can be considered as the underlying reasons for participants’ beliefs that they differ from other international academics.

In the eyes of these participants, government policies and administrative procedures in their home countries were implemented in oppressive manners. Results proved their displeasure with their countries’ governments and authoritarian administrative actions, and this discontent was also found in their HE administrations. They also emphasised the lack of academic freedom at their home institutions and the difficulties and discontentment that arose from these experiences. Based on their experiences at Turkish HEIs, however, participants consider Turkey’s HEI administration to be more transparent, inclusive, and welcoming. This finding suggests that by preventing structural and social problems ahead of integration, the Turkish higher education system can benefit more from these academics in increasing its teaching and research capacity. This finding also concurs with previous studies emphasising the importance of enacting democratic values visibly in higher education, as well as building administrative structures in accordance with modern management principles (Çetinsaya, Citation2014; Linda, Citation2003).

Our results also show that participants have favourable opinions of the Turkish higher education system in terms of university administration, educational quality, academic freedom, and facilities offered by universities. The majority of the participants are not only happy working at Turkish universities, but they also find the infrastructure of these institutions to be satisfactory, which they claim increases their motivation and academic performance. Furthermore, they suggest that the quality of education is higher than that of their home countries’, causing them to feel a greater sense of academic autonomy in Turkey. Consequently, participants mentioned that the overall quality of HEIs in their own countries is lower and they have more limited opportunities offered to them there.

The aforementioned findings could be regarded as a strong indicator for recently implemented policies and practices aimed at supporting international quality assurance at Turkish universities, as well as those in other developing countries. Accordingly, Seggie and Ergin (Citation2018) examined these steps to improve the IHE cycle at Turkish HEIs by highlighting the importance of recognisable international standards designed to attract both international students and academics. Thus, the Council of Higher Education (Citation2017) noted in a report that the IHE process has become a policy priority, thanks to the growing efforts to significantly increase the number of international students and scholars in recent years.

The results indicate that there are structural and social barriers that disadvantage FDAs. Among structural barriers, work permits stand out as the most frequently experienced one. In the work permit issue, the participants faced a ‘double-edged sword’ situation. On one hand, FDAs are provided with the privilege to obtain Turkish citizenship, which they consider as an opportunity to permanently settle in Turkey. On the other hand, they also mention that if they choose to become a citizen, they must give up their current job because the labour law requires them to apply for the same position as a Turkish citizen. This results in a serious barrier that disadvantages FDAs as they are obliged to succeed in the Academic Personnel and Graduate Studies Exam, which is a Turkish language-based test. Given that participants’ positions do not require them to teach in Turkish, thus they only have basic competence in the Turkish language and that there is little language support for such temporary staff to build their skills, it is hardly possible for them to compete in an open competition for tenure track positions. More specifically, participants underline the fact that the legal regulations regarding employment requirements should be modified, or FDAs should be granted with an exceptional FDA status providing job security. Furthermore, the participants often addressed the language barriers they experience in their professional lives. Since official documents are all in the Turkish language, these FDAs need constant assistance in translation, particularly at the initial stages of their employment process. They also complain that there is no office or unit responsible for language assistance and orientation for international academics since there is a shortage of personnel fluent in either English or Arabic at their institutions. They propose that Turkish universities should offer language support or arrange free Turkish language courses accordingly. Therefore, our results imply that policymakers should make significant efforts to minimise the structural and social barriers that disadvantage FDAs. More specifically, Turkey needs more comprehensive and compatible policies and facilitating approaches that will set the stage for FDAs to operate more effectively in the system, possibly resulting in more contribution from them to improve the research and instruction capacity of Turkish universities.

The participants also highlighted other structural problems regarding their economic conditions, workload, and contract duration. They not only fiercely criticised the short-term job contracts, but also the legal regulations that prevent foreign academics from working in summer schools. This frustration with the aforementioned issues originates mostly from the CoHE’s restrictions, which limit international academics’ access to revolving funds to cover cost for extra classes and summer schools, as well as limiting their employment contracts to two years at most (CoHE, Citation2020). The findings, therefore, highlight FDAs’ demand for wider social opportunities and legal rights. Similarly, Seggie and Ergin (Citation2018) suggest offering more competitive and long-term work contracts to attract international academics, as well as the need to reduce these academics’ course loads according to international standards. Thus, our results point to an urgent need for further legal arrangements aimed to provide FDAs with proper and equal conditions within the system.

In terms of social discrimination as a social barrier, the majority of participants reported that they have not faced discrimination, and that their academic identity is highly valued within Turkish society. However, there are also participants who stated they have been subjected to discriminatory treatment by some people in society. This suggests that social discrimination intersects with social and educational status. This finding is important as it contrasts with previous research indicating that the level of social tolerance for migrants is strong in the Turkish society and that Turkish people largely consider migrants, asylum seekers, and refugees as guests and have a high level of empathy for them (Erdoğan, Citation2014; Sezgin & Yolcu, Citation2016; Tunç, Citation2015).

The results also demonstrated that FDAs and their families face loneliness and isolation and have difficulty engaging fully in social life because of their inability to speak the Turkish language. This result echoes Seggie and Ergin's (Citation2018) argument that the orientation process should aim to adjust foreign academics and their families to their new community and help them with the problems of education and housing. Previous research has identified that the inability of individuals to speak the language of their host country negatively affects their socio-cultural adaptation, thereby causing loneliness and psychological adjustment problems (Ataca & Berry, Citation2002; Maydell-Stevens et al., Citation2007). Given these language barriers, we recommend that policymakers and educational administrators build a comprehensive social support policy encompassing the basic needs of FDAs, such as language assistance, social orientation programmes, housing, and schooling for their children, in order to elevate FDAs contribution to their institutions.

This study has also several limitations that need to be considered when interpreting findings. First, the data came from the FDAs employed in a single Turkish university. Therefore, more research is needed to further explore the lived experiences of FDAs regarding their current status in the Turkish higher education context. Second, even though the researchers do not hold any positions of formal authority to jeopardise trust and rapport in the study, their being Turkish citizens, who enjoy a level of privilege that FDAs do not, could create a potential limitation which might have shaped the interviewees’ responses. Third, the Turkish society largely consider people like FDAs as guests. This image may have triggered the interviewees to behave like ‘good guests’ during the interviews and paint a happier picture of their experience than they would if talking with fellow FDAs. Finally, our sample did not include any female respondents, which hinders our ability to gain deeper insight into the lived experiences of female FDAs in the system. The disproportionate gender representation stems from the fact that there were only two female FDAs at the university, both of whom refused to participate in the study. Since both authors were male, this might have created a potential/partial factor in female invitees’ refusal to participate in the study. Thus, we advise future research may address this issue by finding ways to include female FDAs into their sample. Furthermore, the literature may benefit from research that contains a mixture of views and experiences from both Turkish scholars and FDAs to achieve a comparative analysis. Since the study was designed as a phenomenological inquiry, employing different research designs could also offer new insights. Consequently, it is beyond the scope of this research to fully explore the phenomenon in all dimensions, such as FDAs’ social adaptation problems, psychological well-being, and factors affecting their job satisfaction. For instance, we still know little about the nature and extent of social discrimination that FDAs experience, as well as how it relates to their social, economic, or educational status. Therefore, we recommend further research to shed light on such issues, which promises to inform effective higher education policies to address the issues around FDAs’ challenges and needs.

Grants and Funding Statement

The authors received no specific grants or funding for this work.

Acknowledgments

We thank the academics participated in the research.

Disclosure statement

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Kürşat Arslan

Kürşat Arslan, PhD candidate, is a lecturer in the School of Foreign Languages at Karabuk University. He received his BA in ELT department at Istanbul University and completed his MA studies in Educational Administration at Karabuk University. During his career, Arslan has fulfilled roles in various professional fields, including English Language Teaching and Educational Administration, presented papers in national and international conferences, and published various research articles. He has a particular research interest in educational administration, organizational and educational leadership, higher education studies, internationalization of higher education, refugee and displacement studies in educational context.

Ali Çağatay Kılınç

Ali Çağatay Kılınç, PhD, is a full professor of educational administration and leadership in the Department of Educational Sciences at Karabuk University, Turkey. He received his PhD from the Department of Educational Sciences, Division of Educational Administration, Gazi University, Ankara, Turkey in 2013. His research focus is on educational leadership, school improvement, teacher learning and practices, and internationalization of higher education.

References

- Arar, K., Haj-Yehia, K., Ross, D. B., & Kondakci, Y. (2019). Higher education challenges for migrants and refugee students in a global world. In K. Arar, K. Haj-Yehia, D. B. Ross, & Y. Kondakci (Eds.), Higher education challenges for migrants and refugee students in a global world (pp. 1–23). Peter Lang.

- Arar, K., Kondakci, Y., Kaya Kasikci, S., & Erberk, E. (2020). Higher education policy for displaced people: Implications of Turkey’s higher education policy for Syrian migrants. Higher Education Policy, 33(2), 265–285. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1057/s41307-020-00181-2

- Ataca, B., & Berry, J. W. (2002). Psychological, sociocultural, and marital adaptation of Turkish immigrant couples in Canada. International Journal of Psychology, 37(1), 13–26. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00207590143000135

- Çetinsaya, G. (2014). Büyüme, kalite, uluslararasılaşma: Türkiye yükseköğretimi için bir yol haritası. Yayın No: 2014/2. Ankara: Yükseköğretim Kurulu.

- Çelik, N. B. (2017). Güncel gelişmeler ışığında Türk vatandaşlığının istisnai haller kapsamında kazanılması. Türkiye Baralor Birligi Dergisi, 130, 357–418. http://tbbdergisi.barobirlik.org.tr/m2017-130-1666

- Bélanger, D., & Saracoglu, C. (2019). Syrian refugees and Turkey: Whose “crisis”? In C. Menjı´var, M. Ruiz, & I. Ness (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of migration crises(pp. 279–296). Oxford University Press

- Council for At-Risk Academics (CARA) (2019). Annual report 20182019. https://www.cara.ngo/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/190920-Annual-Report-2018-19-FINAL.pdf.

- Council of Higher Education [CoHE] (1981). The law on higher education (Law 2547). https://www.yok.gov.tr/Documents/Yayinlar/Yayinlarimiz/the-law-on-higher-education.pdf

- Council of Higher Education [CoHE] (1983). The law on higher education personnel (Law 2914). https://www.mevzuat.gov.tr/MevzuatMetin/1.5.2914.pdf

- Council of Higher Education [CoHE] (2017). Yükseköğretimde uluslararasılasma strateji belgesi. https://yok.gov.tr/

- Council of Higher Education [CoHE] (2020). Yükseköğretim Kurumlarında Yabancı Uyruklu Öğretim Elemanı Çalıştırılması Esaslarına İlişkin Bakanlar Kurulu Kararı. https://yok.gov.tr/

- Creswell, J. W. (2012). Educational research: Planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research (4th ed. ed.). Pearson.

- Creswell, J. W. (2013). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches (3rd ed.). Sage.

- Directorate General of Migration Management, [DCMM], (2017). 2016 Türkiye göç raporu (Migration report for 2016). https://www.goc.gov.tr/yillik-goc-raporlari.

- Directorate General of Migration Management, [DCMM], (2021). The number of Syrians under temporary protection. https://www.goc.gov.tr/gecici-koruma5638

- Erdoğan, A., & Erdoğgan, M. M. (2018). Access, qualifications, and social dimension of Syrian refugee students in Turkish higher education. In A. Curaj, L. Deca, & R. Pricopie (Eds.), European higher education area: The impact of past and future policies (pp. 259–276). Springer.

- Erdoğan, M. M. (2014). Türkiye‟deki Suriyeliler: Toplumsal Kabul ve uyum. Hacettepe Üniversitesi Göç ve Siyaset Araştırma Merkezi. http://www.hugo.hacettepe.edu.tr/HUGO-RAPORTurkiyedekiSuriyeliler.pdf

- Erdoğan, M. M. (2019). Türkiye’deki Suriyeli mülteciler. TAGU – Türk-Alman Üniversitesi Göç ve Uyum Araştırmaları Merkezi. https://www.kas.de/documents/283907/7339115/T%C3%BCrkiye%27deki+Suriyeliler.pdf/acaf9d37-7035-f37c-4982-c4b18f9b9c8e?version=1.0&t=1571303334464

- Hayden, M. C., Thompson, J., & Williams, G. (2003). Student perceptions of international education: A comparison by course of study undertaken. Journal of Research in International Education, 2(2), 205‒232. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/14752409030022005

- İçduygu, A., & Keyman, E. F. (2000). Globalization, security, and migration: The case of Turkey. Global Governance, 6(3), 383–398. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1163/19426720-00603006

- İnce, C. (2019). An evaluation on migration theories and Syrian migration. OPUS–International Journal of Society Researches, 11(18), 2579–2615.https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.26466/opus.546737

- Kaya, İ., & Yılmaz Eren, E. 2015. Türkiye’deki Suriyelilerin hukuki durumu, arada kalanların hakları ve yükümlülükleri. Rapor: 50. SETA.

- Khorsandi Taskoh, A. (2014). A critical policy analysis of internationalization in postsecondary: An Ontario case study. The University of Western Ontario. http://ir.lib.uwo.ca/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3340&context=etd

- Kondakci, Y., & Onen, O. (2019). Migrants, refugees, and higher education in Turkey. In K. Arar, K. HajYehia, D. Ross, & Y. Kondakci (Eds.), Refugees, migrants, and global challenges in higher education (pp. 223–241). Peter Lang.

- Larsen, M. A. (2013). Internationalizing higher education: A case study of ethical internationalization. Paper presented at the CIES Conference, New Orleans, March 2013. CIES.

- Linda, H. (2003). Article on leadership development: A strategic imperative for higher education. Harvard University.

- Marshall, C., & Rossman, G. (2016). Designing qualitative research (6th ed). Sage.

- Massey, D. S., Arango, J., Hugo, G., Kouaouci, A., Pellegrino, A., & Taylor, J. E. (1993). Theories of international migration: A review and appraisal. Population and Development Review, 19(3), 431–466. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/2938462

- Özkan, I. (2013). Göç, iltica ve sığınma hukuku. Seçkin.

- Maydell-Stevens, E., Masgoret, A. M., & Ward, T. (2007). Problems of psychological and sociocultural adaptation among Russian speaking immigrants in New Zealand. Social Policy Journal of New Zealand, 30, 178–198. http://hdl.handle.net/10536/DRO/DU:30034195

- Patton, M. Q. (2002). Qualitative research and evaluation methods (3rd ed.). Sage Publications.

- Seggie, F. N., & Ergin, H. (2018). Yükseköğretimin uluslararasılaşmasına güncel bir bakış: Türkiye’de uluslararası akademisyenler. (SETA) Siyaset, Ekonomi ve Toplum AraĢtırmaları Vakfı.

- Şeremet, M. (2015). A comparative approach to Turkey and England higher education: The internationalism policy. Journal of Higher Education and Science, 5(1), 27–31. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5961/jhes.2015.106

- Sezgin, A. A., & Yolcu, T. (2016). Social cohesion and social acceptance process of incoming international students. Humanitas, 4(7), 417–436.https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.20304/husbd.14985

- Teichler, U. (2009). Internationalization of higher education: European experiences. Asia Pacific Education Review, 10(1), 93–106. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s12564-009-9002-7

- The International Labour Force Law [ILFL], Law 6735) (2016). https://www.atakurumsal.com/en/international-labour-force-law-law-no-6735/

- Tunç, A. Ş. (2015). Refugee behaviour and its social effects: An assessment of Syrians in Turkey. Journal of TESAM Academy, 2(2), 29–63. https://dergipark.org.tr/tr/pub/tesamakademi/issue/12946/156434

- UNHCR. (2018) . Global trends: Forced displacement in 2018. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees.

- Universities UK International [UUKI). (2018). Higher education and displaced people. Retrived from https://www.universitiesuk.ac.uk/policy-andanalysis/reports/Documents/International/highereducation-and-displaced-people-final.pdf

- Watenpaugh, K. D., Fricke, A. L., & King, J. R. (2014). We will stop here and go no further: Syrian university students and scholars in Turkey. Institute of International Education. http://www.scholarrescuefund.org/sites/default/files/pdf-articles/we-will-stop-here-and-go-nofurther-syrian-university-students-and-scholars-in-turkey-002_1.pdf

- World Economic Forum. (2017). Migration and its impact on cities - An insight report. http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Migration_Report_Embargov.pdf