ABSTRACT

In 2014 the International Journal for Academic Development (IJAD) issued a call for papers for ‘Beyond learning and teaching: Extending the frontiers of academic development’. Though it was never published, the conceptual and definitional opacity that this special issue was expected to address, along with prevalent epistemic parochialism, remain problematic for academic development scholarship, and this article focuses on them. The article incorporates a critique of the field’s scholarship within a conceptual analysis of academic development that culminates in presentation of the author’s original conceptual model of the componential structure of academic development. Academic development scholarship, it is argued, is poised at a crossroad; its epistemic development is dependent upon its adopting a wider focus and agenda that its critical scholars are calling for, to diffuse the mainstream focus on teaching and learning. Mainstream scholarship is ripe for epistemic expansion into neighbouring fields, to encourage academic developers to shift their focus from what it is they do, to what they do is.

Academic development had its genesis in the 1960s and ’70s. In the wake of the massification of higher education (HE), cadres of academic developers were appointed in higher education institutions (HEIs) to support academics in dealing with the diverse learning needs of an expanded student population. Reflecting this original remit to develop the quality of HEI teaching, as I discuss below, prioritisation of the teaching and learning aspect of academic work has prevailed as the status quo within the academic development field, defining its mainstream focus. Yet a growing constituency of academic developers continue to question the narrowness of this focus of their practice and, by extension, of their scholarship.

My interest in this field that is not my own was prompted by the International Journal for Academic Development’s (IJAD) call (issued in 2014) for contributions to Beyond learning and teaching: Extending the frontiers of academic development. Planned for 2016, this special issue was aimed at ‘set[ting] the course for a broadened scholarship of academic development’, encompassing ‘new areas’ beyond learning and teaching, into which academic development teams were urged to ‘branch out’ (Anon, Citation2014). The IJAD’s then editor, Brenda Leibowitz, envisaged the special issue’s pointing the way out of the field’s ‘definitional quagmire’ and ‘shed[ding] light on the extent to which there is engagement in aspects of academic development that are beyond the frame of “learning and teaching”’ (Leibowitz, Citation2014, p. 359). Yet, with the issue’s failure to materialise, such hopes remained forlorn – until 2018, when the IJAD then published a special issue that, as its editor implies, reinvigorated the spirit of its ‘lost’ predecessor:

IJAD had put out a call for contributions to a special issue tentatively titled ‘Beyond learning and teaching: Extending the frontiers of academic development’ to be published in 2016. We had in mind, then, an issue similar to the one you now hold in your hands or read on your screen. The issue did not transpire, however, as we did not receive enough submissions. Over the last couple of years, though, various pieces of work have since been submitted to IJAD that challenge traditional conceptions of academic development, and help readers think differently about the academic development project. … [T]he editorial team have gathered these pieces up and offer them now as the final issue for the year, coalescing around this ‘found’ theme of ‘holistic academic development’. (Sutherland, Citation2018, p. 262)

This ‘tale of two special issues’ reflects the vision and resilience of those members of the academic development community who recognise both that ‘[s]hifting landscapes require us to adjust and re-establish our footing and perhaps find alternative paths to pursue as new possibilities come into view’ (Le-May Sheffield & Timmermans, Citation2021, p. 119), and that their field’s continued epistemic development is dependent not only on (in the words of Sutherland, cited above) ‘challeng[ing] traditional conceptions of academic development’, but also (and in doing so) addressing the fundamental question that shapes their work: what is meant by academic development?

I have made this question the focus of my paper, for, as Parkinson et al. (Citation2020) note, how academic development is defined and where its parameters lie remain sources of tension. This tension is reflected in repeated attempts over the last decade or so on the part of the field’s pioneering visionaries – not least (but not only) through the IJAD special issue initiatives – to raise awareness of the need for prioritising fundamental conceptual issues. There are clear signs that the academic development field is reaching a critical point in its development. Following the lead of Parkinson et al. (Citation2020, p. 184) in both attempting to extend ‘the conceptual and contextual scope’ of the academic development field and choosing to do so in a multi-focal forum, I aim to engage with a readership representing multiple cross-sector constituencies who, as academics, have a right to be involved in defining the conceptual parameters of academic development as a concept, as practice and as a field of scholarship. Yet I locate my contribution within a discursive, and associated lexical, framework appropriated from the IJAD, whose aborted 2016 special issue sub-title sums up, for me – and, it seems, for the initiators of and contributors to the IJAD’s 2018 special issue, referred to above – a topic that needs placing at the top of the academic development field’s agenda: extending the frontiers of academic development.

Frontier-extension: re-imaginings and re-conceptualisation

In a general context, frontier-extension may occur by force – most often as a result of conflict, and through the translation of physical strength into power or might – or by negotiation, willing surrender or gifting, prompted by beneficence or expediency. But frontiers may also be extended by re-adjustment and re-imagining – by re-identification of oneself, or of others, or of the places and spaces that contribute to informing identities and identification. I refer here principally not to physical but to the intangible, invisible frontiers that we identify, strengthen, or tear down – individually or collectively – in all aspects of our lives, and that we use to categorise, compartmentalise, and explain away attitudes, emotions and behaviours. Yet re-imagining or re-identification involves re-conceptualisation. Whether concrete or abstract, all frontiers are (also) concepts. They cannot therefore be truly or meaningfully extended without being re-conceptualised; the frontier that is not re-conceptualised has not shifted in the mind of the individual whose conceptualisation of it remains unaltered – though the shift, it is important to note, may be slight, and occurring through gradual, potentially barely perceptible, expansion of how we perceive or think about something. By presenting an outline conceptual analysis that culminates in an original conceptual model of academic development, this article contributes towards such re-conceptualisation.

I begin by outlining some of what, as I have found and interpret it, the field’s literature indicates to be prevalent conceptualisations of academic development.

Academic development: examining the concept

As an academic, rather than an academic developer, it had never occurred to me that, as the call for papers for the planned 2016 IJAD special issue begins, ‘learning and teaching are seen as the heart of academic development’, or that any deviation from this perspective should be seen as novel – as indicating acknowledgement of a ‘new area’ (Anon, Citation2014). I have always considered it axiomatic that, since academic work involves so much more than teaching, then so too should academic development. With its implication that there is another constituency of HE professionals that does not necessarily or consensually see it this way, the call for papers was an eye-opener. It set me wondering how this constituency conceives its principal function and focus, and just how closely aligned with academic work and working life is such a conception. If frontiers are to be crossed or pushed back, I wondered, what are the nature and degree of the re-conceptualisation needed? To address this question, I needed to know how academic development, within its current boundaries, is conceived.

I accordingly searched the literature for definitions of academic development. Predictably, perhaps, in the light of Linder and Felton’s (Citation2015, p. 1) observation that ‘a precise and shared definition’ remains elusive, I found none – none, that is, that qualifies as a stipulative definition: ‘a precise, unambiguous explanation that stipulates what something is and that is exclusive in applicability’ (Evans, Citation2002, p. 64), or, in Richard Pring’s (Citation2000, pp. 9–10) words: an explanation, ‘in precise and unambiguous terms’, of ‘what you mean when you use a particular word’. I then set my sights lower, seeking out what I call conceptual interpretations (Evans, Citation2002) – which equate to what Pring (Citation2000, p. 11) categorises as a way of defining through thinking ‘of the different ways of understanding which are brought together under this one label’.

Conceptual interpretations of academic development are plentiful. Expressed in vaguer terms – such as Leibowitz’s (Citation2014, p. 359) use of ‘about’ in: ‘academic development is about the creation of conditions supportive of teaching and learning, in the broadest sense’ - than appear in stipulative definitions, they skirt around, rather than get to the core of, the essence of whatever they are focused on explaining. In describing rather than defining, they may indicate what something includes, looks like, or concerns, but fall short of stipulating precisely what it is. How, then, is academic development as a concept interpreted in the field’s literature?

From myopic to expansive vision: a continuum of conceptualisation

I identify within the literature what may best be described as a continuum of interpretative or conceptual expansiveness. At one end lies a narrow conceptualisation of academic development that equates it (academic development) to – or rather, conflates it with – development that focuses exclusively on teaching and learning-related academic work. This conflation is in many cases implicit; seemingly widely accepted as a given, it privileges teaching-and-learning-speak as the lingua franca of academic development territory. Fluency in this lingua franca seems pervasive, reflecting Blackmore and Blackwell’s (Citation2006, p. 380) concern that ‘the “default” position in the minds of many academic developers, and others in universities, is that academic development for faculty is wholly or mainly about teaching and learning’.

Well over a decade and a half since Blackmore and Blackwell expressed it, their concern about a teaching and learning-focused default position remains relevant and justified. The opening sentence of Baume and Popovic’s (Citation2016) edited book on academic development practice, for example, reads: ‘We suggest an overall purpose for academic development – to lead and support the improvement of student learning’ (Popovic and Baume, Citation2016, p. 1), while Green and Little’s (Citation2013) examination of boundary-crossing is confined to consideration of academic development as educational development, just as Winter et al. (Citation2017, p. 1504) claim that ‘[t]he aim of academic development is to promote academic practice in higher education lecturers with emphasis on enhancing teaching and learning’, and Sutherland and Grant (Citation2016, p. 189) note the ‘likelihood that much of our research is about teaching and learning’. Debowski’s (Citation2014, p. 50) description of academic developers as ‘influencing agents seeking to guide policy, practice, and broader sectoral debate about learning and teaching matters’ (emphasis added) suggests similar alignment with the ‘default position’, and, more recently – despite identifying a potentially widened role for academic developers that encompasses supporting (and even contributing to) institutional strategy, Fossland and Sandvoll (Citation2021, p. 11) clearly retain a narrow teaching and learning focused perspective on the substantive parameters of such a role: ‘educational leaders at all levels … need to position ADs as experts on teaching and learning and as contributors to educational change – beyond their work on teaching development and support’ (emphasis added). Moreover, my impressionistic analysis, based on my reading of them, indicates that in the ‘Latest articles’ section of the International Journal for Academic Development’s website, at the time of writing (mid-June, 2023), out of 48 listed articles, all except nine − 18.75% − through explicit definition or conceptual interpretation or/and through the article’s substantive focus, implied a conceptualisation of academic development as predominantly focused on academics’ teaching and learning-focused development.

Given its genesis and history, it is understandable that the academic development field emerged with a dominant focus on teaching and learning. Yet it is clear that – and this reflects the tension referred to above – some academic developers are pushing for a wider agenda; amidst the literature’s conflation-of-academic-development-with-teaching-and-learning chorus, I discern other tongues trying to make themselves heard. A broader vocabulary – including words such as ‘holism’, ‘coherence’ and ‘de-fragmentation’ – reveals within the discourse on academic development’s remit, focus and parameters a critical sub-text that ranges from questioning to challenging its (academic development’s) conflation with education development. Such sub-text permeates Sutherland’s (Citation2018, p. 261) editorial in the 2018 IJAD special issue referred to above:

We could be more ‘holistic’ about academic development.

We could broaden our focus beyond learning and teaching to consider the whole of the academic role. (original emphasis)

One dimension of this critical discourse is recognition (by, for example, Gibbs, Citation2016; Khoo, Citation2021; Matthews et al., Citation2014; Petrova & Hadjianastasis, Citation2015; Stensaker et al., Citation2017; Zou & Geertsema, Citation2020) that research is in many institutional and cultural contexts a pre-eminent academic activity, afforded at least as much attention as teaching, and that some academics self-identify first and foremost as researchers.

I locate yet further along the conceptualisation continuum evidence of recognition that academic practice involves much more than teaching and research. Boud and Brew (Citation2013), for example, acknowledge the multi-dimensional and multi-faceted nature of most academics’ work, and the need for institutions to provide opportunities for their academic employees to develop across their range of roles’ (p. 208, emphases added). Åkerlind (Citation2011, p. 184), too, highlights the constraining consequences of ‘a fragmented perspective on academic development’ that separates ‘teaching and teaching development from other aspects of academic work, in terms of academics’ experiences of their own growth and development’, and Blackmore and Blackwell (Citation2006, p. 373) similarly argue for ‘an integrated conception of academic development’ that includes ‘teaching, research, knowledge transfer and civic engagement, leadership, management and administration, and … their interrelationships’ (p. 375).

Such holistic perspectives on academic development are evident in literature that incorporates foci on overarching change to academic work in its widest sense, including the structures that frame and support it. Highlighting two key concepts – change practice and change agency – as central to academic development, McGrath (Citation2020), for example, adopts a generic interpretation of academic developers as change brokers, and proposes a new model of practice for academic development ‘to shift the focus from identifying the individual as a recipient of training to one where academic development is more focused on context-based change practice’ (p. 103), within a ‘new paradigm’ of academic development work. Parkinson et al. (Citation2020), too, offer a distinct perspective on and conceptualisation of academic development: as academic community development.

With their evident wider visions, all such authors located at varying degrees of distance from what I call the narrow-teaching-and-learning-focused-conceptualisation-of-academic-development end of my continuum represent the field’s epistemic expansionists: its boundary-shifters. As occurs with all fields of scholarship, such pioneering perspectives inevitably constitute a critical community that, in initiating and sustaining a critical discourse, distinguishes itself from more conservative and ‘traditional’ perspectives that, by comparison, become identified as the mainstream. Indeed, within the philosophy and history of science, such spreads (or continua) of perspectives, vision and agendas – and the controversy and disagreement that they inevitably spawn – are recognised as key stages in a field’s epistemic development; as Kitcher (Citation2000, p. 27) notes, ‘complete homogeneity is frequently a very poor distribution in terms of advancing the community’s epistemic state’. He (Kitcher, Citation2000) highlights diversity of practices as the catalyst for development, and outlines the process through which a critical wing or community challenges the mainstream:

Individual practices plainly outrun consensus practice. Hence, the basis for controversy is always present. A controversy erupts when some individual (or group of individuals) within the community proposes that a particular component of consensus practice should be modified to become more closely aligned with the individual practice(s) of the proposer. (p. 23)

Kitcher (Citation2000, p. 29) argues that such dissension towards mainstream perspectives and practices – what he calls ‘scientific controversies’ – occur(s) on a ‘field of disagreement in which alternative individual practices compete as candidates for the modification of consensus practice’ (original emphasis), and that scientific controversies have beginnings, middles and endings, and may persist for substantial periods of time – often several decades. I discern such a field of disagreement to be being marked out on the academic development scholarship landscape, to house a ‘controversy’ (to use Kitcher’s term) that, despite having emerged as critical commentary well over a decade ago, is still at its protracted ‘beginning’ stage – which involves, inter alia, distinguishing the field’s mainstream scholarship on the basis of what are identified as limitations that are perceived by critical scholars as compromising the stability of the field’s foundations.

A field with shaky foundations? Critical perspectives on academic development scholarship

As Boud and Brew (Citation2013, p. 208) observe: ‘academic development … remains an under-theorised field of endeavour’, and Cunningham (Citation2022, p. 2) notes that ‘the field of academic development (what it is, its nature or identity) is itself under-theorised’. Taking Suddaby’s (Citation2014, p. 407) explanation of theory as ‘a way of imposing conceptual order on the empirical complexity of the phenomenal world’, I apply here a wide interpretation of ‘theoretical’, to include conceptual and epistemological clarity and bases – both of which, as I imply above, are elusive in the mainstream academic development literature. Whilst Harland and Staniforth (Citation2008, p. 669) complain that ‘the field does not have widely shared values or epistemological foundations’, a striking limitation is that its literature is dominated by interpretations and perspectives of academic development as work, with ‘academic development’ frequently applied as a term that describes, delineates and discusses the academic development community’s practice as developers or change agents; indeed, Clegg (Citation2009, p. 403) describes it as a ‘field of practice in higher education’ (emphasis added).

This predominantly practical focus may stem from institutional factors: specifically, appointments criteria, for McNaught (Citation2020, p. 84) expresses bemusement ‘by the appointment of academic development staff only on professional terms with no requirements for any scholarly endeavours … academic writing and publication – what I consider essential to closing the evidential loop – are not part of the job description and so rarely done’. Despite claims that the academic development knowledge base is both broad and inter-disciplinary (see, for example, Kensington-Miller et al., Citation2015; Sutherland & Grant, Citation2016), evidence of academic developers tapping into some of the key knowledge-gains made in the last two decades into how people learn and develop professionally is elusive – to the extent that, whilst it certainly exists, such scholarship cannot justifiably be considered a key or core strand of the field’s scholarship. Indeed, it was their rarity within the academic development field’s literature that drew me to a collection of articles (Chadha, Citation2021; Dorner & Belic, Citation2021; Thomson & Barrie, Citation2021; Thomson & Trigwell, Citation2018) that are distinct in reflecting such knowledge-gains into professional learning: specifically, those relating to informal and implicit learning.

Two fields in particular – workplace learning (including, most notably, the work of Michael Eraut, which Thomson and Barrie, referred to above, draw upon), and the broader field of professional learning and development – have made great epistemic strides, including the development of conceptual and processual models (see Boylan et al., Citation2018, for an analysis of ‘five significant contemporary analytical models’ of professional learning) that have much to offer academic development scholarship. Located within the latter field and informed by the former, my analysis below proposes an adaptation of one such model – my own – as a way forward through the conceptual quagmire identified by Leibowitz (Citation2014), cited above, and towards addressing the question posed by Sutherland (Citation2018): what do we mean by academic development?

The academic development field’s mainstream discourse incorporates a marked focus on academic developers’ consideration of themselves as, collectively, a community of practitioners dispensing a form of relational – and often responsive – change-effecting agency. Academic development is thus conceptualised, by extension (and, in most cases, implicitly), as experienced activity. Presented as: how I/we ‘do’ academic development, this experienced activity seems to be the default analytical starting point, with how I/we should ‘do’ academic development representing the analytical terminus. Clegg (Citation2009, p. 409) identifies the epistemological narrowness of this prevalent mode of scholarship:

The knowledge we have about academic development practice is notable for its rhetorical functioning and degree of reflexive interiority. Unlike knowledge of many other social domains this knowledge is largely produced by practitioners, about themselves, their theories-in-use, organisational structures and values.

She then highlights the limitations of academic developers’ accounts of their practice: ‘this writing represents an important resource in understanding the project of academic development itself. The danger is that it can produce an uncritical and self-justificatory rhetoric’ (Clegg, Citation2009, p. 412).

My own criticism of this dominant mainstream discourse is that it lacks both analytical depth and perceptual expansiveness. Interpreting and ‘analysing’ academic development narrowly as something that academic developers do (or should do) is akin to considering primary education as simply something that primary teachers do, disregarding not only the other key constituency in question – primary school children – but also, through lack of stipulative definitional precision, the very notion or concept of primary education: what it is. While those whom I call critical academic development scholars may engage in conceptualisation- and definitional-focused discourse, the mainstream is distinguished by its scholars’ evident predilection for examining themselves within the niches of a mirror-lined epistemic fortress from which they may on occasion peer out to see what lies beyond. This tendency is highlighted not only by ‘outsiders’ such as Clegg, cited above, but also by those from within the academic development community; David Baume (Citation2016, p. 97), for example, suggests: ‘perhaps we might choose to spend a little less time looking into the mirror at ourselves and our field, and more time looking out of the window, or, more useful still, striding out through the doorway’, while Sutherland (Citation2018, p. 261) suggests, more generally: ‘we could be more capacious, and more critical, in our view of the support we provide, the development we offer, and the research we read, write, share and publish’ (emphasis added).

‘If academic development aspires to being “academic”, then one is forced to ask what our subject is and where our knowledge comes from’, observe Harland and Staniforth (Citation2008, p. 675). In response to Ray Land’s (Citation2001) argument that academic developers are focused on effecting change, we might pose a similar question: what, precisely, is it that they wish to, or intend to, or should be trying to, change? The answer, I believe, is tied to the question that is my main focus: what is academic development? Below, I present my response(s) to both questions.

(Re-)conceptualising academic development

If those who research and write about it retain a conceptualisation of academic development that is limited to what they, as academic developers, do, they will remain hemmed into a small ‘territory’, from where they will struggle to make out what lies beyond, in neighbouring fields that could most usefully, and relatively easily, become common ground, yielding rich pickings for all who traverse them. Expansion into such fields requires mainstream scholars to follow the lead of their critical academic development colleagues in, rather than centring their discourse on what it is they do, turning their attention to consideration of what they do is. As Sutherland and Grant (Citation2016, p. 194) argue: ‘[n]ot all our work needs to be concerned with what we or others do’.

What is academic development?

Those academic developers who place themselves – their practice(s), their purpose(s), their community/ies, their service(s), their units – at the centre of their scholarship are effectively (and probably unwittingly) inflating their importance. More significantly, this developer-centric perspective represents a distorted picture of a development process that is predicated upon the requirement for both a developer and developee(s), whose role titles (within the context of the development process) indicate who is the doer and who the done-to or done-by – rather like the subject and object of a sentence whose verb is ‘to develop’. My objection to such an academic developer-centric perspective is disinterested; it is totally unrelated to my own position as an academic, and hence a putative or potential developee – my point is semantic, not proprietorial, in focus. I would make precisely the same point about lion taming or fruit picking: to perceive them purely and simply (or even predominantly) as actions performed by one who (tries to) tame(s) lions or one who picks fruit is to limit them as concepts. But even in cases where the focus of analysis is intended to be narrowly aligned with delineating the role or purpose of the agents or agencies performing the actions – of taming lions or picking fruit – such delineation will be deficient if it is not grounded upon conceptual clarity. To understand what makes an effective fruit picker, one must first grasp what the verb ‘to pick’ denotes, what the action of picking involves, and what fruit is. Ditto for lions and taming. All components of the concept (fruit and picking; taming and lion) must be clear, otherwise one could end up picking vegetables instead of fruit, or being devoured by lions.

Mainstream academic developers’ key preoccupations seem to be with their own contexts, their own positionings and resultant identities, and their own practices. They seem to be focused on academic developing, rather than development – indeed, as recently as 2022 an entire issue (volume 27, issue 4) of the IJAD was devoted to presenting the stories of academic developers and academic development researchers. Yet there is, as Leibowitz (Citation2014) and Sutherland (Citation2018) imply, a need to backtrack: to consider first what academic development is – or, more precisely, to consider versions of what academic development may be (since, in the interests of advancing the field by stimulating debate, I neither seek nor aim to achieve conceptual or definitional unanimity). Here, I propose one such version.

Developing what?

A key question to consider, when we refer to academic development, is what (note: not whom), precisely, is it that is being (or intended to be) developed?

There is no ‘right’ answer, of course; any reasonable and reasoned response is as acceptable as the next. Before I offer mine, and to set the context for it, it is important to explain that I see academic development as a specific form or component of the wider concept of professional development – or, perhaps more precisely, as a specific focus of professional development. I present professional development as an overarching concept that encompasses other, more specific, forms of it, as implied by labels such as: teacher development, headteacher development, academic development, or researcher development. Of all these silo-focused labels, academic development is potentially the most contentious to define since, as I note elsewhere in my conceptualisation of academic leadership (Evans, Citation2018), ‘academic’ may be used as a noun or as an adjective. I interpret academic development as essentially a form of professional development that applies to those who may be categorised as academics, or who carry out what may be considered academic work.

In response to the question posed above, I contend that, in the case of professional development, it is people’s professionalism that is the focus of development. In the more specific case of academic development, it is academics’ professionalism that is (or intended to be) developed. This contention is underpinned by what I propose as an umbrella definition of academic development – one that defines it as a process. Adapting slightly my published umbrella definition of professional development (e.g. Evans, Citation2014a, Citation2019), I define academic development as the process whereby academics’ professionalism may be considered to be enhanced. Since, within this definition, the notion and importance of professionalism are pivotal, I make a detour in order to present my interpretation of what I call professionalism.

Professionalism: examining the concept

In the vernacular, professionalism is perceived as something desirable, commendable and praiseworthy. Being ‘professional’ carries positive connotations, whilst ‘unprofessional’ is uncomplimentary. Moreover – and a factor that explains why those two adjectives (professional and unprofessional) have acquired such wide general usage and application – professional status seems to have been appropriated by increasing numbers of occupational groups over the last few decades.

Yet this appropriation of professional status by the many, rather than the elite few, reflects a societal shift that has reshaped specialist academic conceptions of professionalism; as a result, in the sociology of professions the focus has shifted away from issues related to professional status and who should have it, since, in the context of 21st century working life, these are no longer important (if they ever were). I am with Julia Evetts (Citation2013, p. 780), who points out that ‘[t]o most researchers in the field it no longer seems important to draw a hard and fast line between professions and occupations but, instead, to regard both as similar social forms which share many common characteristics’. The consequence of this shift of priorities, she argues, is that we need ‘to look again at the theories and concepts used to explain and interpret this category of occupational work’ (p. 779).

Accordingly – and in common with others (e.g. Barnett, Citation2011; Nixon, Citation2001; Noordegraaf, Citation2007) who have proposed original conceptualisations that reflect the context of 21st century working life – I present my own distinct interpretation of professionalism. To me, professionalism is, quite simply, a description of people’s ‘mode of being’ in a work context, or of how they ‘go about’ their work – irrespective of whether that translates into practice that is praiseworthy or practice that is despicable. So-interpreted, professionalism overlaps with, yet is ‘bigger’ than, practice, since it (professionalism) incorporates what underlies and influences ‘mode of being’ in a work context. Involving qualitatively-neutral practice, professionalism, to me, is not – as the wo/man in the street would probably have it – a merit-laden concept, so the term ‘unprofessional’ becomes both meaningless and redundant: professionalism is something that everyone ‘has’ or ‘does’ in a work context.

Since it is an over-arching, comprehensive feature of all persons at work, rather than a kitemark of quality, professionalism does not denote status that is pursued or aspired to. As I interpret it, it relates to and conveys: what practitioners do; how and why they do it; what they know and understand; where and how they acquire their knowledge and understanding; what (kinds of) attitudes they hold; what codes of behaviour they follow; what their function is: what purposes they perform; and what quality of service they provide.

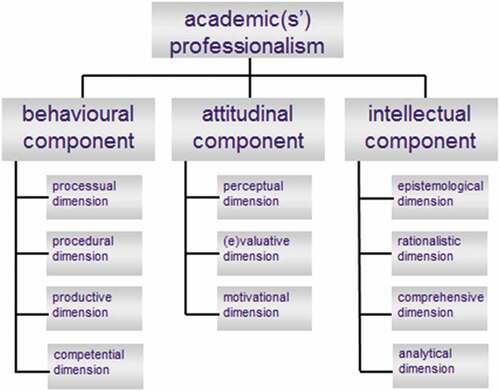

The list above represents what I currently consider the key elements or dimensions of professionalism, and for greater specificity it (the list) may be adapted to denote academic(s’) professionalism by replacing the word ‘practitioners’ with ‘academics’. My conceptualisation of academic professionalism, represented in (adapted from my conceptual models of professionalism more generally, e.g. Evans, Citation2018; Evans & Cosnefroy, Citation2013), essentially deconstructs professionalism into such key constituent parts, labelled concisely and generically.

I identify three main constituent components of (academic, or academics’) professionalism: behavioural, attitudinal, and intellectual. Each incorporates its own dimensions, of which I currently identify eleven, indicated in (their vertically-sequenced presentation does not imply hierarchical positioning). In representing what I conceive as professionalism’s composition, through its componential structure the model demonstrates what I consider to be its (professionalism’s) ‘essence’: what it essentially is.

The behavioural component of academic professionalism relates to what academics physically do at work. Its sub-components: the processual, procedural, productive, and competential dimensions, relate respectively to: processes and procedures that academics apply to their work (the processual and the procedural dimensions); academics’ output, productivity and achievement (how much they ‘do’ and what they achieve); and their skills and competences. The processual dimension accounts for a disproportionately large element of practitioners’ – in this case, academics’ – work. By ‘processes’ I include, for example, interpersonal interaction (direct or indirect, face-to-face or virtual/remote; verbal or non-verbal – and, if verbal, whether oral or in writing); this may involve work-related interaction with any constituency. ‘Processes’ also includes the vast range of other activities that constitute academic work, and that may variously be categorised as, inter alia: research, knowledge exchange, teaching, administration, leadership, and citizenship – each of which potentially involves a myriad of diverse activities that, representing different hierarchical levels, may be categorised as being subsumed within others, which are subsumed within others, and so on: reading, writing, listening, speaking, reflecting, hypothesising, analysing, data-collecting, disseminating, etc.

The attitudinal component of academic professionalism relates to academics’ attitudes. Its sub-components: the perceptual, (e)valuative, and motivational dimensions, relate respectively to: academics’ perceptions, beliefs and views (including those relating to oneself, hence, self-perception and identity); their values, and what matters to them and what they like and dislike; and their levels of motivation, job satisfaction and morale.

The intellectual component of academic professionalism relates to academics’ knowledge and understanding, and their knowledge structures. Its sub-components – the epistemological, rationalistic, comprehensive, and analytical dimensions – relate respectively to: the bases of academics’ knowledge; the nature and degree of reasoning that they apply to their practice; what they know and understand; and the nature and degree of the analyticism that they incorporate into or apply to their work.

Academic development: examining the concept

Since I argue that it is one or more of the dimensions of academic professionalism that academic development is involved in, or focused on, changing, my conceptual model of academic development, illustrated in , closely resembles that of academic professionalism (). It is distinct from the model of the componential structure of academic professionalism only in relation to the terminology used to label the constituent elements: ‘development’ and ‘change’ are used instead of ‘component’ and ‘dimension’.

Located within my ‘umbrella’ definition of academic development as: the process whereby academics’ professionalism may be considered to be enhanced (which, with the word ‘enhanced’, implies change or modification that may be considered to be for the better), I currently define each of behavioural, attitudinal and intellectual development as, respectively, the process whereby an academic’s: physical, or otherwise potentially visible, activity is modified; attitudes are modified; and knowledge, understanding or reflective or comprehensive capacity or competence are modified. The meanings of the eleven more specific dimensions of change – processual, procedural, productive, competential, perceptual, (e)valuative, motivational, epistemological, rationalistic, comprehensive and analytical – may easily be determined by reference to the explanations of them as dimensions of professionalism, presented above.

The multi-dimensionality of academic development

As I perceive it then, academic development is multi-dimensional. Its scope encompasses much more than changing behaviour, or increasing skillsets or ranges of competencies; it may just as often (also) involve changing, inter alia, how people view things, their capacity for analysing or rationalising, what matters or is important to them, or their morale or motivation levels. While a single developmental ‘episode’ (to use Eraut’s [Citation2004] term), for it to count as development, requires change to just one dimension, it will most often involve change to several, through a kind of imperceptible chain reaction or domino-effect. A practitioner’s – an academic’s – professional development throughout her/his entire career will involve the accumulation of a vast, incalculable number of such micro-level developmental episodes, merged together, each probably indistinguishable from others.

I propose, then – consistent with my conceptualisation and definition(s) presented above – that all aspects of academics’ ‘mode of being’ at work should be the focus of, and encompassed within what is meant by, academic development. Enhancement of the individual academic’s professionalism (by change for the better to one or more dimensions of her/his professionalism), is, by my conceptualisation, fundamentally what academic development is, and all broader contextually-determined concerns or activities, such as developing teaching, raising research quality, institutional strategic planning, or McGrath’s (Citation2020) ‘change practice’ and ‘change agency’, should reflect consideration of, and be informed by, and aimed at, that fundamental endeavour which underpins policies, procedures and practices that purport or aim to be categorised as examples of academic development.

This multi-dimensional interpretation does not preclude academic development’s encompassing different distinct foci or emphases on specific aspects of academic work, such as leadership, service and citizenship, teaching and supporting students, and researching. I see these, and others, as elements of academic development; elsewhere, for example (Evans, Citation2012, Citation2014b), I note that researcher development is ‘an element of professional development, or, more specifically, of academic development’ (Evans, Citation2014b, p. 48). Agencies focused on researcher development, such as the UK’s Vitae and its researcher development framework, therefore sit under the academic development umbrella (which, in turn, sits within the overarching ‘professional development’ umbrella); I share Khoo’s (Citation2021, p. 2) perspective on developing research: ‘[r]esearcher development staff are at the forefront of … research culture work … . This is an important dimension of academic development work’.

At the risk of exceeding the remit I set myself in writing this paper – to present a conceptual, rather than a processual, analysis – it is worth digressing slightly to emphasise the point that, as research into workplace learning and development shows, and as some academic developers and academic development researchers (e.g. Chadha, Citation2021; Dorner & Belic, Citation2021; Haigh, Citation2005; Hoessler et al., Citation2015; Thomson & Barrie, Citation2021; Thomson & Trigwell, Citation2018) evidently recognise, most developmental episodes occur ‘informally’, or even ‘implicitly’ (Eraut, Citation2004), outside any designated professional or academic development provision. ‘Implicit’ episodes creep up on people silently and stealthily, catching them entirely unawares – so much so that they typically assimilate their developmental product unconsciously, without ever being able to recall what spawned it. Academic developers, then, seldom play leading roles on the academic development stage; each is merely one of a cast of thousands within such multi-dimensional performances that are billed as academic development. I make this point neither to denigrate their work nor to question their value, but to encourage those of them who need to do so, to understand that academic development is not, fundamentally, what they – academic developers – do; it is a (largely unseen) process that, more often than not, without our knowing how, effects change for the better in one or more dimension of an academic’s professionalism. It is, I argue, that process, not academic developers’ work or practice, that is what academic development is.

Breaking through frontiers: new points of departure

While Sutherland and Grant (Citation2016, p. 193) note academic developers’ ‘desire for academic credibility’, Chapman (Citation2005, p. 310) reminds us that ‘the academy judges by the theory and scholarship emerging from a particular field and discipline. … We stand or fall by the weight others attribute to our scholarship’. What weight might ‘others’ attribute to the scholarship of academic development? its practitioners and researchers ought now to be asking.

Critical research, Alvesson and Deetz (Citation2021, p. 6) argue, is:

oriented towards challenging rather than confirming that which is established, disrupting rather than reproducing cultural traditions and conventions, opening up and showing tensions in language use rather than continuing its domination, encouraging productive dissension rather than taking surface consensus as a point of departure.

I situate academic development scholarship at a mainstream-critical crossroad. The kind of questioning and challenging that Kitcher (Citation2000), cited above, associates with scientific controversies seems to be on the cusp of reaching a significant point in the field’s epistemic development – resonant of the beginnings, several decades ago, of the leadership scholarship’s ‘field of disagreement’, which gradually spawned both a critical and, more recently, also a ‘new wave’, of vibrant critical discourse (see Evans, Citation2022) – the latter having given rise to a sub-field that is now established as a leadership-sceptic challenger to the mainstream’s unevidenced claims of leadership’s, and by extension, leaders’, significance to institutional effectiveness.

Will the academic development field branch off along the path towards which its critical scholars are pointing, or will it continue without significant detour along the road that is well-travelled by mainstream scholars keen to retain the teaching and learning-focused status quo? The outcome will depend in no small measure on these scholars’ conceptualisations and definitions of academic development. For their consideration, I have thrown my own into the mix.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Linda Evans

Linda Evans is professor of education at the University of Manchester, where she currently holds the role of deputy head of the School of Environment, Education and Development. Her research focuses broadly on working life in education contexts, and includes studies of, inter alia: professionalism, professional development, researcher development, workplace morale, job satisfaction and motivation, and leadership (most recently incorporating a leadership-agnostic critical perspective). Before moving to the University of Manchester Linda was professor of leadership and professional learning at the University of Leeds. She has also worked at the University of Warwick. A former student of modern European languages, in 2011 she lived in France, where she was a visiting professor at the Ecole Normale Supérieure de Lyon.

References

- Åkerlind, G. S. (2011). Separating the ‘teaching’ from the ‘academic’: Possible unintended consequences. Teaching in Higher Education, 16(2), 183–195. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2010.507310

- Alvesson, M., & Deetz, S. (2021). Doing critical research. Sage.

- Anon. (2014). IJAD special issue call for papers. Retrieved July 14, 2023, from http://www.iced2014.se/docs/IJAD/SI3%20cfp%20extending%20frontiers.pdf

- Barnett, R. (2011). Towards an ecological professionalism. In C. Sugrue & T. D. Solbrekke (Eds.), Professional responsibility: New Horizons of praxis (pp. 29–41). Routledge.

- Baume, D. (2016). Analysing IJAD , and some pointers to futures for academic development (and for IJAD). International Journal for Academic Development, 21(2), 96–104. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2016.1169641

- Baume, D., & Popovic, C. (Eds.). (2016). Advancing practice in academic development. Routledge.

- Blackmore, P., & Blackwell, R. (2006). Strategic leadership in academic development. Studies in Higher Education, 31(3), 373–387. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070600680893

- Boud, D., & Brew, A. (2013). Reconceptualising academic work as professional practice: Implications for academic development. International Journal for Academic Development, 18(3), 208–221. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2012.671771

- Boylan, M., Coldwell, M., Maxwell, B., & Jordan, J. (2018). Rethinking models of professional learning as tools: A conceptual analysis to inform research and practice. Professional Development in Education, 44(1), 120–139. https://doi.org/10.1080/19415257.2017.1306789

- Chadha, D. (2021). Over a nice, hot cup of tea! Reflecting on the conditions for meaningful, informal conversations between academic developers and novice academics. International Journal for Academic Development, 26(3), 373–377. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2021.1932512

- Chapman, V. L. (2005). Attending to the theoretical landscape in adult education. Adult Education Quarterly, 55(4), 308–312. https://doi.org/10.1177/0741713605279473

- Clegg, S. (2009). Forms of knowing and academic development practice. Studies in Higher Education, 34(4), 403–416. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070902771937

- Cunningham, T. (2022). Parallels between philosophy and academic development: Under-labourers, critics, or leaders? International Journal for Academic Development, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2022.2137513

- Debowski, S. (2014). From agents of change to partners in arms: The emerging academic developer role. International Journal for Academic Development, 19(1), 50–56. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2013.862621

- Dorner, H., & Belic, J. (2021). From an individual to an institution: Observations about the evolutionary nature of conversations. International Journal for Academic Development, 26(3), 210–223. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2021.1947295

- Eraut, M. (2004). Informal learning in the workplace. Studies in Continuing Education, 26(2), 247–273. https://doi.org/10.1080/158037042000225245

- Evans, L. (2002). Reflective practice in educational research: Developing advanced skills. Continuum.

- Evans, L. (2012). Leadership for researcher development: What research leaders need to know and understand. Educational Management, Administration and Leadership, 40(4), 432–435. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143212438218

- Evans, L. (2014a). Leadership for professional development and learning: Enhancing our understanding of how teachers develop. Cambridge Journal of Education, 44(2), 179–198. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305764X.2013.860083

- Evans, L. (2014b). What is effective research leadership? A research informed perspective. Higher Education Research & Development, 33(1), 46–58. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2013.864617

- Evans, L. (2018). Professors as academic leaders: Expectations, enacted professionalism and evolving roles. Bloomsbury.

- Evans, L. (2019). Implicit and informal professional development: What it ‘looks like’, how it occurs, and why we need to research it. Professional Development in Education, 45(1), 3–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/19415257.2018.1441172

- Evans, L. (2022). Is leadership a myth? A ‘new wave’ critical leadership-focused research agenda for recontouring the landscape of educational leadership. Educational Management, Administration and Leadership, 50(3), 403–435. https://doi.org/10.1177/17411432211066274

- Evans, L., & Cosnefroy, L. (2013). The dawn of a new academic professionalism in the French academy? Academics facing the challenges of imposed reform. Studies in Higher Education, 38(8), 1201–1221. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2013.833024

- Evetts, J. (2013). Professionalism: Value and ideology. Current Sociology, 61(5–6), 778–796. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011392113479316

- Fossland, T., & Sandvoll, R. (2021). Drivers for educational change? Educational leaders’ perceptions of academic developers as change agents. International Journal for Academic Development, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2021.1941034

- Gibbs, A. (2016). Improving publication: Advice for busy higher education academics. International Journal for Academic Development, 21(3), 255–258. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2015.1128436

- Green, D. A., & Little, D. (2013). Academic development on the margins. Studies in Higher Education, 38(4), 523–537. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2011.583640

- Haigh, N. (2005). Everyday conversation as a context for professional learning and development. International Journal for Academic Development, 10(1), 3–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/13601440500099969

- Harland, T., & Staniforth, D. (2008). A family of strangers: The fragmented nature of academic development. Teaching in Higher Education, 13(6), 669–678. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562510802452392

- Hoessler, C., Godden, L., & Hoessler, B. (2015). Widening our evaluative lenses of formal, facilitated, and spontaneous academic development. International Journal for Academic Development, 20(3), 224–237. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2015.1048515

- Kensington-Miller, B., Renc-Ro, J., & Morón-García, S. (2015). The chameleon on a tartan rug: Adaptations of three academic developers’ professional identities. International Journal for Academic Development, 20(3), 279–290. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2015.1047373

- Khoo, T. (2021). Creating spaces to develop research culture. International Journal for Academic Development, 28(2), 217–229. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2021.1987913

- Kitcher, P. (2000). Patterns of scientific controversies. In P. Machmaer, M. Pera, & A. Baltas (Eds.), Scientific controversies: Philosophical and historical perspectives (pp. 21–39). Oxford University Press.

- Land, R. (2001). Agency, context and change in academic development. International Journal for Academic Development, 6(1), 4–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/13601440110033715

- Leibowitz, B. (2014). Reflections on academic development: What is in a name? International Journal for Academic Development, 19(4), 357–360. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2014.969978

- Le-May Sheffield, S., & Timmermans, J. A. (2021). Creating a collaborative community spirit for the future of academic development. International Journal for Academic Development, 26(2), 117–120. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2021.1918851

- Linder, K. E., & Felten, P. (2015). Understanding the work of academic development. International Journal for Academic Development, 20(1), 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2014.998875

- Matthews, K. E., Lodge, J. M., & Bosanquet, A. (2014). Early career academic perceptions, attitudes and professional development activities: Questioning the teaching and research gap to further academic development. International Journal for Academic Development, 19(2), 112–124. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2012.724421

- McGrath, C. (2020). Academic developers as brokers of change: Insights from a research project on change practice and agency. International Journal for Academic Development, 25(2), 94–106. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2019.1665524

- McNaught, C. (2020). A narrative across 28 years in academic development. International Journal for Academic Development, 25(1), 83–87. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2019.1701476

- Nixon, J. (2001). ‘Not without dust and heat’: The moral bases of the ‘new’ academic professionalism. British Journal of Educational Studies, 49(2), 173–186. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8527.00170

- Noordegraaf, M. (2007). From ‘pure’ to ‘hybrid’ professionalism: Present-day professionalism in ambiguous public domains. Administration and Society, 39(6), 761–785.

- Parkinson, T., McDonald, K., & Quinlan, K. (2020). Reconceptualising academic development as community development: Lessons from working with Syrian academics in exile. Higher Education, 79(2), 183–201. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-019-00404-5

- Petrova, P., & Hadjianastasis, M. (2015). Understanding the varying investments in researcher and teacher development and enhancement: Implications for academic developers. International Journal for Academic Development, 20(3), 295–299. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2015.1048453

- Popovic, C., & Baume, D. (2016). Introduction: Some issues in academic development. In D. Baume & C. Popovic (Eds.), Advancing practice in academic development (pp. 1–16). Routledge.

- Pring, R. (2000). Philosophy of educational research. Continuum.

- Stensaker, B., Bilbow, G. T., Breslow, L., & van der Vaart, R. (Eds.). (2017). Strengthening teaching and learning in research universities. Palgrave Macmillan. Open access. https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007%2F978-3-319-56499-9.pdf

- Suddaby, R. (2014). Editor’s comments: Why theory? Academy of Management Review, 39(4), 407–411. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2014.0252

- Sutherland, K. (2018). Holistic academic development: Is it time to think more broadly about the academic development project? International Journal for Academic Development, 23(4), 261–273. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2018.1524571

- Sutherland, K., & Grant, B. (2016). Researching academic development. In D. Baume (Ed.), Advancing practice in academic development (pp. 188–206). Routledge.

- Thomson, K., & Barrie, S. (2021). Conversations as a source of professional learning: Exploring the dynamics of camaraderie and common ground amongst university teachers. International Journal for Academic Development, 26(3), 320–334. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2021.1944160

- Thomson, K., & Trigwell, K. (2018). The role of informal conversations in developing university teaching? Studies in Higher Education, 43(9), 1536–1547. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2016.1265498

- Winter, J., Turner, R., Spowart, L., Muneer, R., & Kneale, P. (2017). Evaluating academic development in the higher education sector: Academic developers’ reflections on using a toolkit resource. Higher Education Research & Development, 36(7), 1503–1514. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2017.1325351

- Zou, T. X. P., & Geertsema, J. (2020). Do academic developers’ conceptions support an integrated academic practice? A comparative case study from Hong Kong and Singapore. Higher Education Research & Development, 39(3), 606–620. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2019.1685948