ABSTRACT

This article analyses the media coverage of the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) by progressive and conservative media outlets in South Korea from 2000 to 2018. Through systemic content analysis, the study reveals that the tones and content of PISA-related articles were largely influenced by the political alignment between the media outlet and the government in power, rather than the actual PISA results. This finding highlights the opportunistic and circumstantial nature of Korean media coverage of PISA, guided by their contrasting educational agendas towards excellence and equity. This research reveals PISA’s function as a projection screen for reflecting local political intentions and as ammunition data to protect specific agendas from criticism. By uncovering the political expediency inherent in media reports on PISA, this study illuminates the role of PISA as a politicised science that shapes educational agendas and strengthens the OECD governance.

KEYWORDS:

Introduction

Looking abroad at policy models has become a common practice in many countries to improve education systems at home since the nineteenth century. Recently, the emergence of international organisations and international large-scale assessments (ILSAs) has diverted policymakers’ attention from focusing on single-country models to international standards and league tables (Steiner-Khamsi, Citation2003; Waldow et al., Citation2014). The rise of ‘evidence-based policymaking’ (Sutcliffe & Court, Citation2005) has made ILSAs a particularly attractive source of information for policymakers seeking validated information through numerical data and international comparisons (Auld & Morris, Citation2016; Waldow & Steiner-Khamsi, Citation2019). The Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD)’s Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) is one of the most influential ILSAs that impacts education policymaking in numerous countries. PISA enables policymakers to diagnose, monitor, and improve their education systems from an external standpoint, referencing their performance at international league tables and insights from other countries (OECD, Citation2020).

However, beyond its practical value, the use of PISA data is often contextual and political, deviating from the ideal of objective and neutral evidence-based policymaking. Policymakers and the media tend to selectively interpret and utilise PISA data in ways that align with their respective reform agendas (Takayama, Citation2008; Waldow & Steiner-Khamsi, Citation2019). This often results in the incorporation of PISA numbers into educational reform efforts with a political agenda disguised as scientific objectivity, leading to controversies regarding its application in policymaking (Araujo et al., Citation2017; Saltelli, Citation2017). Therefore, the politics inherent in selecting and framing PISA results with local meanings deserve special scholarly attention to consider the potential pitfalls of invoking science in education policy discourses and policies.

This study analyses the media coverage of PISA in South Korea (hereafter Korea) to explore the politics of using science in educational debates and the process of local meaning-making of global educational knowledge. Previous research studies have focused on the influential role of the media in filtering PISA information and influencing related policy decisions (McCombs & Shaw, Citation2007; Pizmony-Levy, Citation2018; Takayama, Citation2008). Understanding how the media generates PISA discourses within specific national contexts provides valuable insights into the politics involved in using PISA to inform policy, alongside nuanced local interpretations of global educational ideas (Hu, Citation2022; Pizmony-Levy, Citation2018; Takayama et al., Citation2013). To contribute to the existing literature, this study incorporates the political leanings of the media and the government in power as analytical units in analysing PISA media coverage. This article considers these supplementary elements to comprehensively examine the media portrayal of PISA, given that the political context strongly influences local interpretations of global educational references (Waldow & Steiner-Khamsi, Citation2019). Furthermore, this study adopts a longitudinal approach, spanning two decades and covering seven cycles of PISA from 2000 to 2018, and employs text mining in addition to article content coding to conduct a thorough and in-depth analysis of the media coverage of PISA.

Specific research questions are as follows: 1) How did conservative and progressive news media in Korea frame the results of PISA differently during changes in administration? 2) How did both media outlets construct different meanings from PISA results to their respective educational agendas? This article aims to identify how selective and creative local meaning-making of PISA occurs on the media screen politically. By uncovering the political expediency inherent in media reports on PISA, this study illuminates the role of PISA as a politicised science that shapes educational agendas and strengthens the OECD governance.

Background

The influence of PISA on Korean educational reforms

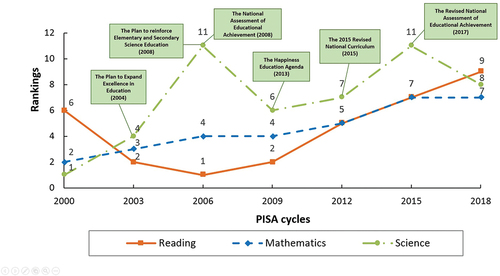

Korea’s consistent participation in PISA and the significant national attention given to its results make the country an ideal case for media analysis. illustrates the fluctuations in Korean students’ PISA rankings over time and the main educational reforms following PISA releases. Despite facing challenges in rankings as more countries participate in recent cycles, Korean students have been generally successful in PISA. However, instead of merely celebrating their success, the Korean government has been proactive in identifying areas for improvement and implementing necessary changes promptly, demonstrating increased governance by the OECD in the country (Shin & Joo, Citation2013).

Figure 1. Korean students’ PISA rankings over time and subsequent educational reforms.

As shown in , the results of PISA 2000 and 2003 were used as part of the argument for the introduction of the Plan to Expand Excellence in Education in 2004 during the Roh Moo-hyun administration. Some educators, along with the media, criticised the education equalisation system implemented in 1999, which aimed to reduce academic burdens and provide equal educational opportunities to all students (Kim, Citation2017). The critique argued that the existing education equalisation system was insufficient for top-ranked students to reach their full potential, calling for the policy plan to provide gifted education for the top 5% of students (Hong, Citation2004). Similarly, the criticism against PISA 2006, focusing on the declined scientific literacy ranking, attacked the 7th national curriculum (1997~2006), which reduced lesson hours and removed difficult learning content (Jung & Oh, Citation2007). This critique, referred to as ‘PISA science shock’, contributed to the argument for introducing the Plan for Reinforcing Elementary and Secondary Science Education (2008–2012) during the Lee Myung-bak administration, aiming to invest in school laboratories and to double the number of science teachers (Park, Citation2017). Additionally, the Lee Myung-bak administration introduced the national assessment of educational achievement to promote excellence in education (The Academy of Korean Studies, Citationn.d.). In 2009 and 2012, further critiques highlighted the low well-being of Korean students behind their high PISA achievements, influencing the introduction of the Happiness Education agenda and the 2015 revised national curriculum (2015–2021) during the Park Geun-hye administration. These policies were aimed at reducing academic burdens and increasing students’ life satisfaction. In a similar vein, the Moon Jae-in administration revised the national assessment of educational achievement to reduce academic competition and enhance student well-being (The Academy of Korean Studies, Citationn.d.). Based on this national context, this study focuses on the interpretation of PISA science as policy evidence presented in the media space, which impacts educational policies in Korea.

Literature Review

Local receptions of PISA through the media: recontextualisation, externalisation, and mediatisation

The global success of PISA has elevated the influence of OECD on national policymaking through ‘governance by comparison and numbers’ (Grek, Citation2009; Martens, Citation2007). According to Steiner-Khamsi’s (Citation2003) typology, countries display different reactions to PISA, even with similar scores, labelled as scandalisation (highlighting the negatives of one’s education system), glorification (highlighting the positives of one’s education system), and indifference. These reactions reflect politics that arise when certain aspects of PISA numbers are emphasised, often involving the selection of ‘reference societies’ (Bendix, Citation1978). Policymakers in many countries intentionally exaggerate or omit certain elements of their PISA results to justify specific educational agendas or reforms. For example, Australia concentrated on national average scores while neglecting regional disparities (Baroutsis & Lingard, Citation2017). The prominence of Finnish education often overshadows the PISA success of Asian countries due to the negative portrayal of Asian education as exam-focused (Waldow et al., Citation2014).

In essence, PISA acts as a ‘projection screen’ (Waldow, Citation2017) or an ‘empty vessel’ (Steiner-Khamsi, Citation2014) that varies depending on local meaning-making. Concerning this, researchers have paid attention to the role of the media in ‘filtering’, ‘framing’, and ‘priming’ PISA results. The media has the power to control access to certain types of information (filtering), shape the presentation of realities (framing), and provide preconceptions as references for new information (priming) (Herman & Chomsky, Citation1988; Iyengar, Citation1990; Iyengar & Kender, Citation1982). Previous studies on media coverage of PISA have analysed these strategies through the lenses of ‘recontextualisation’ (Schriewer, Citation2000; Steiner-Khamsi, Citation2014), ‘externalisation’ (Schriewer, Citation1990; Steiner-Khamsi, Citation2004), and ‘mediatisation’ (Strömbäck, Citation2011; Thomas, Citation2006).

Recontextualisation refers to modifying borrowed ideas or policies to fit local contexts (Steiner-Khamsi, Citation2014). This process can occur through two mechanisms: externalisation and mediatisation, as indicated by prior literature. Externalisation stands for the actions of local actors who draw upon ideas or policies from outside their home country to legitimise their proposed solutions or exert pressure for reforms (Steiner-Khamsi, Citation2004). References to ILSAs involve two forms of externalisation: invoking scientific rationality and citing effective educational systems identified in international comparisons (Steiner-Khamsi, Citation2003). Scholars have investigated how PISA is recontextualised within local media through the politics of externalisation in various countries (e.g. Takayama, Citation2009; Takayama et al., Citation2013; Waldow et al., Citation2014). Mediatisation is defined as a process where the media shape and reshape public discourses and policy decision-making (Strömbäck, Citation2011; Thomas, Citation2006). Researchers have uncovered the recontextualisation of PISA media discourses through mediatisation and its (possible) impacts on national education policies (e.g. Baroutsis & Lingard, Citation2019; Grey & Morris, Citation2018; Hu, Citation2022).

Delving deeper into how national media fill the conceptual screen or vessel of PISA with local meanings within the frameworks of recontextualisation, externalisation, and mediatisation is crucial to grasping the underlying socio-political logic of PISA coverage and OECD governance. Previous literature on media communications has unveiled the media’s varying coverage patterns, driven by ideological biases that propagate conservative or progressive values on specific topics, such as presidential elections and climate change (e.g. Dotson et al., Citation2012; Peng, Citation2018). Some studies have illuminated the emergence of a conservative media bias, attributing it to factors such as corporate ownership, profit motives, the sway of conservative interest groups, and reliance on authoritative sources such as governmental think tanks (e.g. Alterman, Citation2003; Bagdikian, Citation2004; Herman & Chomsky, Citation1988). Likewise, a liberal media bias has been acknowledged, tied to factors including the personal liberal leanings of media personnel and the rise of a new elite class that challenges traditional values (e.g. Groseclose & Milyo, Citation2005; Lichter et al., Citation1990). Nevertheless, counterclaims have arisen, asserting that the alleged ideological media bias lacks substantial empirical evidence (e.g. Covert & Wasburn, Citation2007; D’Alessio & Allen, Citation2000).

Transitioning to the education field, wider studies have explored media reporting of PISA in various countries, including Australia (Baroutsis & Lingard, Citation2017; Crome, Citation2022; Takayama et al., Citation2013; Waldow et al., Citation2014), China (Hu, Citation2022; Liu, Citation2019), Germany (Takayama et al., Citation2013; Waldow, Citation2017; Waldow et al., Citation2014), Japan (Takayama, Citation2008), Portugal (Santos et al., Citation2022), Singapore (Crome, Citation2022), Sweden (Lundahl & Serder, Citation2020), the UK (Grek, Citation2008), and the US (Saraisky, Citation2015). Several common findings about contextual disparities between conservative and progressive media outlets, observed in some of these prior studies, indicate that the conservative media tends to embrace PISA, while the progressive media expresses greater scepticism (e.g. Saraisky, Citation2015; Takayama, Citation2009). This divergence in coverage patterns becomes more detailed when examining the case of Korean media coverage of PISA. For example, Takayama et al. (Citation2013) and Waldow et al. (Citation2014) revealed that both progressive and conservative media tended to downplay the Korean PISA success, with this tendency being more prominent in the progressive media. It was observed that progressive journalists employed PISA results to validate their rejection of neoliberal market-oriented educational reforms, whereas conservative writers used PISA to legitimise them. In terms of reference societies, the Korean progressive media often lionised Finnish education, while the conservative media more frequently cited Shanghai and Japan as evidence in favour of competition-oriented education. These findings raise the question of whether they are valid in the broader landscape of Korean media discourse on PISA over two decades and across a wider range of media outlets. In response, this study revisits the media coverage of PISA in Korea to scrutinise the extent and nature of ideological media bias in Korean PISA coverage.

Data and methods

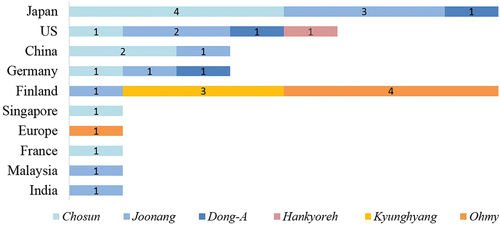

This study conducted systemic content analysis drawing on a total of 132 articles from six news media outlets in Korea to explore how the media utilised PISA differently according to their political stance. I selected three conservative media (Chosun Daily, JoongAng Daily, Dong-A Daily) and three progressive media (Hankyoreh News, Kyunghyang News, Ohmy News) based on well-known symbolic acronyms for the most representative conservative and progressive media in Korea, Cho-Joong-Dong and Han-Kyung-oh.Footnote1 All the selected media are not government-controlled and rank within the top 10 for print circulation in 2019, except for Ohmy News. In 2019, the influence rankings of news providers (including both newspaper and broadcast companies) were: Chosun Daily (2nd), JoongAng Daily (3rd), Dong-A Daily (4th), Kyunghyang News (16th), Hankyoreh News (17th), and Ohmy News (unranked) (Jang, Citation2019).

Using the Korea Integrated News Database System (BIGkinds) and each six media outlets’ websites, I searched for relevant news articles published within a month from the release date of the results of seven PISA cycles from 2000 to 2018. I used the search words ‘PISA’ and ‘Gukje Hakup Sungchido Pyunga (PISA in Korean)’, and then excluded duplicates and irrelevant results. My search yielded a total of 155 articles, of which 132 were screened and selected in the final data according to this exclusion criteria. Out of these articles, 85 were published by conservative media outlets (36 in Chosun Daily, 25 in Dong-A Daily, and 24 in JoongAng Daily), while 47 appeared in the progressive media (23 in Kyunghyang News, 9 in Hankyoreh News, and 15 in Ohmy News). This distribution demonstrates that, despite the progressive media’s lower influence rankings, progressive media outlets produced a comparable number of PISA-related articles to the conservative media, excluding Hankyoreh News.

Next, all the articles were thoroughly analysed in three steps. A coding protocol was initially developed based on the work of Saraisky (Citation2015) to examine the patterns of media coverage of PISA in Korea, which consisted of five sections: the tone of the article headline, descriptions of PISA, presentations of PISA results, content of the text, and implications of PISA results. As with previous studies (e.g. Hu, Citation2022; Saraisky, Citation2015), the majority of the analysis focused on descriptive statistics, such as percentages. The protocol was pilot-tested and modified based on the results, which were validated by another Korean-speaking researcher. One adjustment made was to analyse the tone of the article headlines instead of assessing the overall tone of the entire article content by the observation that most articles in the pilot study exhibited a mixed tone throughout their content, while their titles adeptly conveyed the writer’s primary emphasis and political intentions. Following the coding process, a detailed codebook was created to capture the nuances and hidden meanings present in the article content. Lastly, text mining was employed using all the text data from 132 articles, totalling 47,091 words. I visualised word clouds using Python 3.8 to display the most prominent words in each conservative and progressive media discourse on PISA. Word clouds are valuable tools for intuitively outlining and comparing the content of two politically contrasting media discourses. Additionally, they help detect less frequent but meaningful words that frequency counts may overlook.

Findings

Patterns of the media coverage of PISA in conservative and progressive media

This section provides an overview of how Korean news media, classified as conservative and progressive, covered the PISA outcomes since its first cycle in 2000. presents the results of the coding protocol, outlining the content of 132 articles from both types of media outlets (85 from the conservative media and 47 from the progressive media). In , dark cells are highlighted for better readability, indicating a noteworthy difference of more than a four-percentage-point gap between the two media in certain categories.

Table 1. Features of Korean media coverage of PISA 2000–2018.

Overall, the majority of article headlines tended to be negative, especially evident in the conservative media. Over half of the headlines in the conservative media (56%) carried a negative tone, whereas only 19% had a positive tone. In contrast, 40% of the headlines in the progressive media were negative, while 34% were positive. Both media outlets extensively covered various aspects of PISA, including the PISA acronym, the role of the OECD, and the methodology, with a greater emphasis observed in the progressive media. The limitations of PISA, such as the exclusion of non-participating countries, were scarcely mentioned by both media, suggesting a high level of regard for PISA as a credible reference. When presenting PISA results, both media preferred rankings over raw scores and percentiles, with a higher preference observed in the conservative media.

In terms of content, the conservative media placed more emphasis on student achievement, differences over time, and the gap between top-performing and bottom-performing students. On the other hand, the progressive media paid greater attention to student attitude/engagement, and differences in student achievement linked to gender, family socioeconomic status (SES), and schools within the country. While nearly every article covered student achievement, student attitude/engagement received comparatively less attention in both media. Over half of the articles in both media discussed changes in PISA results over time, and nearly 60% introduced PISA results of other countries, primarily those within the top 10 rankings, for comparison. However, the progressive media highlighted differences within the country more (66%) than the conservative media did (62%). The mention of the gender gap was similar in both media at about 15%, but the coverage of the gap related to family SES and schools was more prevalent in the progressive media, by around 4%.

Although over 60% of the total articles in both media referred to PISA results of other countries, only about 20% called for policy learning from foreign countries. As shown in , the conservative media often referenced neighbouring countries such as Japan and China, as well as Western developed countries such as the US and Germany. In contrast, the progressive media almost solely focused on Finland as a model for equitable education. This focus on Finland by the progressive media, coupled with their interest in broader national disparities like the family SES gap and school gap, signifies their commitment to addressing educational inequality.

These findings suggest implicit fundamental differences in the coverage patterns of conservative and progressive media, despite the relatively small gap in percentage points observed in many categories between these media. The similarity in article content may be attributed to the media’s efforts to maintain neutrality, the restricted number of articles in my data, and shared writing practices employed to provide comprehensive information about PISA results for their readers. To gain a deeper understanding of how PISA was utilised in these media, it is crucial to consider whether these tendencies consistently persisted or varied depending on the national political circumstances. Additionally, it is necessary to analyse how similar the actual content of the articles from conservative and progressive media was when they covered the same aspects of PISA results. These questions will be addressed in the subsequent sections.

Changes in the tone of article headlines in parallel with government changes

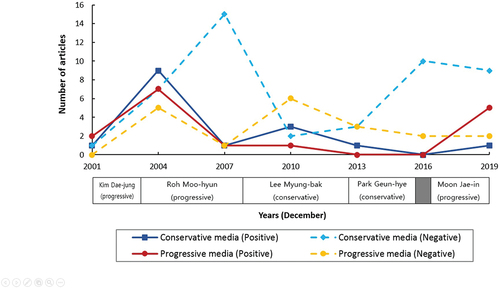

This section delves into the media’s utilisation of PISA as a political tool for advocacy or criticism by analysing the influence of government changes on the tone of PISA-related article headlines. illustrates the number of articles from conservative and progressive media that employed either negative or positive headlines in parallel with changes in the country’s government from 2001 (PISA 2000) to 2019 (PISA 2018). To ensure a clear comparison, neutral or mixed-tone headlines were not depicted. Throughout the period, five administrations were in place: two conservative ones – Lee Myung-bak administration (2008–2013), and Park Geun-hye administration (2013–2017) – and three progressive ones – Kim Dae-jung administration (1998–2003), Roh Moo-hyun administration (2003~2008), and Moon Jae-in administration (2017–2022). It is worth noting that the number of articles from the conservative media (85) exceeds that from the progressive media (47) when interpreting .

Figure 3. Trends in article headline tone aligned with government changes.

According to , the tone of article titles in both media was significantly associated with the political alignment between the media and the government. The tone of the headlines did not always align with changes in Korean students’ PISA performances (see ). In general, both media tended to have negative headlines when the ruling government had a different political orientation from the media’s political view. The conservative media published more positive headlines in 2010 during a right-oriented government’s tenure, as indicated by the dark blue solid line in . Conversely, the progressive media showed more positive headlines in 2001, 2004, and 2019, coinciding with periods when a left-oriented government held power, as evident in the red solid line. Counter to the positive trend, the conservative media generated more negative headlines in 2007, 2013, 2016, and 2019 when a right-oriented government was in power, except for 2013, as indicated by the light blue dotted line. In contrast, the progressive media tended to carry negative headlines in 2010, 2013, and 2016 when a right-oriented government was in control, as shown by the yellow dotted line. As a result, the light blue and yellow dotted line in exhibit a roughly symmetrical pattern, particularly noticeable between 2014 and 2019.

The common belief is that lower PISA rankings may result in more negative article tones. However, my findings from challenge this assumption. Sometimes, even with lower PISA rankings than before, article headlines in Korean media exhibited more positivity. This pattern implies that certain articles aimed at neutral reporting of PISA facts, while others may have displayed a biased attitude driven by political motivations. To enhance our understanding of ideological media bias in PISA coverage in Korea, conducting an in-depth content analysis considering national contexts is necessary, which will be explored in the following section.

Different meaning-making of PISA results: excellence versus equity in education

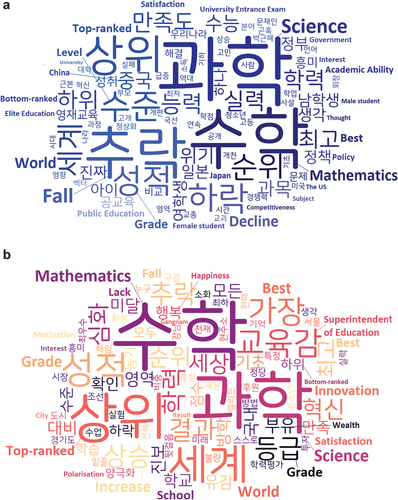

presents word clouds illustrating the most frequent words in the PISA-related articles from both conservative and progressive media. In , the top 10 salient keywords in the conservative media include ‘science’ (569), ‘mathematics’ (540), ‘fall’ (455), ‘top-ranked’ (394), ‘decline’ (260), ‘grade’ (153), ‘level’ (141), ‘rank’ (136), ‘world’ (101), and ‘academic ability’ (91). These words reflect the primary concern of the conservative media, which centres around the decreasing PISA rankings, particularly in science and mathematics. The word cloud of the progressive media shares similar keywords with the conservative media, albeit with a slightly more positive tone. Its top 10 frequently used words are ‘mathematics’ (225), ‘science’ (215), ‘top-ranked’ (184), ‘world’ (131), ‘grade’ (110), ‘superintendent of education’ (107), ‘best’ (106), ‘fall’ (97), ‘result’ (89), and ‘increase’ (82).

These keywords characterising the portrayal of PISA by conservative and progressive media imply that both produce seemingly similar articles based on the same PISA results from a neutral perspective. However, the less frequently used yet meaningful words identified in the word clouds hold the potential to tell a different story. In , words such as ‘best’, ‘elite education’, ‘competitiveness’, ‘China’, ‘Japan’, and ‘the US’ emerge, shedding light on the conservative media’s interest in promoting excellence in public education to not fall behind in the global competition. In contrast, includes words such as ‘happiness’, ‘interest’, ‘motivation’, ‘satisfaction’, ‘city’, ‘Gangnam’,Footnote2 ‘polarisation’, and ‘wealth’, most of which are absent in the conservative media’s word cloud. This indicates the progressive media’s focus on reduced competition, student well-being, and regional student inequality.

The analysis of word clouds suggests that conservative and progressive media in Korea interpreted PISA results through the lens of their distinct educational agendas: excellence or equity in education. A more detailed examination of the article content reveals substantial differences in the messages conveyed by each media outlet. further elucidates how these media infused PISA data with varying meanings from PISA 2000 to PISA 2017, reflecting their divergent pursuits and responses to shifts in government. The table delineates the five prominent facts driven by PISA that were highlighted in the media: Top-level achievement/Improvement of achievement, Decline in achievements, Educational models, Low student well-being, and Student achievement gap, along with sample quotes. The specific choice of words and the emphasis in the articles offer insights into how each media framed the same PISA evidence differently to advocate for their respective educational agendas.

Table 2. Different meaning-making of PISA by conservative and progressive media in Korea.

In Korean media, the PISA fact related to Top-level achievement/Improvement of achievement was utilised to convey positive messages, suggesting the efficacy of the current education system and government initiatives. However, upon delving into the article content, it became apparent that conservative and progressive media interpreted this fact differently over multiple periods. Conservative media articles often portrayed right-oriented governments as successful in educating students and emphasised the significance of their policies, such as the national assessment of educational achievement, in fostering educational excellence. In contrast, the progressive media highlighted the effectiveness of left-wing government policies in advancing educational equity and student well-being, exemplified by the education equalisation system.

Similarly, the fact of Decline in achievement was frequently used by the conservative media to criticise left-wing educational policies that prioritised educational equalisation. They blamed policies focused on equity for the decline in PISA rankings and called for educational reforms aimed at nurturing more elites through competition. Even when Korean students’ overall PISA performances were good, the conservative media pointed out declines in the achievements of top-performing students to support their excellence-centred agenda. On the other hand, the progressive media stressed the importance of supporting underperforming students using PISA results. They criticised educational policies that promoted competition, expressing concerns about their potential adverse effects on educational equality and student well-being.

The fact regarding Educational models, which suggests that Korea can learn from other countries to improve its education system based on PISA results, was also interpreted differently by each media outlet. The conservative media cited education policies in economically developed countries where elite education was pursued, such as the UK, the US, and Singapore. They also pointed out examples where left-wing-style education reforms had failed, such as Japan. Japan’s return to the traditional competitive system from Yutori (relaxed) education, which reduced the content and hours of instruction in core academic subjects, served as compelling evidence for the conservative media to bolster their excellence-centred agenda. On the other hand, the progressive media often argued that Korea should learn from Finland’s equal and less competitive education system. They asserted that the education equalisation system, successful in Finland, could also be effectively implemented in Korea.

Additionally, the fact concerning Low student well-being was addressed differently by conservative and progressive media. The conservative media aimed to convey the message that Korea should strive to ‘catch up with’ other countries with higher levels of student life satisfaction, on par with the OECD average. On the contrary, the progressive media emphasised the significance of reducing competition in education to prioritise students’ well-being and happiness. Similarly, the fact of Student achievement gap was subject to different meaning-making by the two types of media. The conservative media perceived it as a matter of national competitiveness, focusing on the relatively lower performance of Korean males and top-ranked students compared to their international counterparts. Conversely, the progressive media approached it from an equity perspective, considering it as an issue of domestic educational inequality.

These varied interpretations of PISA facts by conservative and progressive media shed light on their distinct mechanisms of understanding and presenting PISA data, driven by their respective educational agendas. These findings offer potential explanations for the contrasting tones of PISA-related articles from conservative and progressive media during administration changes, as revealed in previous sections (see ). For example, the negative responses of the conservative media to PISA results can be partially attributed to their intention to criticise educational policies that prioritise equity, often implemented by left-wing governments. They understated the credit given to left-wing governments for the successes in PISA 2000 and 2003, pointing out the relatively lower achievements of top-ranked students. With regards to PISA 2006, they focused on the declined science ranking instead of the high rankings in reading and mathematics to critique the equity-centred policies of the leftist government. The decline in PISA 2015 and 2018 rankings was utilised as evidence of the failure of prior policies that placed less emphasis on competition, without considering other potential contributing factors, such as the increase in the number of participating countries in PISA. In contrast, the progressive media, which initially portrayed a more positive view of PISA results from PISA 2000 to 2006, altered their stance from PISA 2009 to 2015 when rightist governments took office. Their criticism of the competition-oriented educational policies of conservative governments, in light of Korean students’ high academic achievements but low well-being, affected educational reforms with an emphasis on prioritising student happiness. These examples illustrate how the divergent meaning-making process of PISA data, influenced by the respective agendas of conservative and progressive media, underpins the contrasting tones observed in PISA-related articles within each media during shifts in administrations.

Discussion and conclusion

This article provides empirical evidence on the media coverage patterns of PISA in Korea, highlighting the politically motivated use of PISA evidence in education policy debates. The findings show the persistence of previously identified ideological media bias in PISA coverage within the broader Korean media landscape. It is essential to note that not all news articles express explicit ideological media bias; some maintain a neutral perspective. Yet, the significance of this article lies in its capacity to illuminate the nuanced ideological media bias intertwined with differing educational agendas of equity and excellence. As indicated in previous studies, the Korean conservative media tends to support neoliberal market-oriented education policies, often referencing developed competitor countries. In contrast, the progressive media contests such policies, leaning towards the Finnish egalitarian education model. However, my findings suggest that the progressive media’s approach to PISA is not inherently more critical than that of the conservative media; the attitudes of the Korean media towards PISA fluctuate based on national circumstances, when distinct educational agendas of equity and excellence are underscored as national objectives by ruling governments. The conservative media in Korea strategically emphasises particular aspects of PISA results to legitimise their advocacy for increased competition and rigour in education. Consequently, when the ruling government holds a conservative stance, PISA-related articles in the conservative media tend to exhibit a more positive tone. In contrast, the progressive media highlight specific aspects of PISA information that align with their equity and well-being concerns, often leading to more positive headlines during periods when leftist governments are in power.

This observation unveils the intricate nature of ideological media biases on educational issues and underscores the opportunistic and circumstantial nature of Korean media coverage, thereby revealing the function of PISA as a ‘politicised science’. This pattern may not universally extend to all education-related media coverage in Korea, as it necessitates further studies involving subsequent PISA data, evolving media practices, and variations in educational issues. Nevertheless, it does yield meaningful insights into the selective and creative local meaning-making of global educational ideas. The Korean media recontextualises PISA and concocts local meanings of the PISA results according to their politics of externalisation and mediatisation. Through filtering, framing, and priming, their coverage of PISA (re)shapes national educational discourses, signalling shifts in government leadership and the overarching national educational agenda. The changes in media reportage of PISA during governmental transitions highlight PISA’s role as a projection screen that mirrors the political intentions of local voices and political circumstances. Additionally, these changes illustrate how PISA functions as ammunition data for local stakeholders to safeguard their specific education reform agendas against potential criticism.

Furthermore, this article suggests that the ‘political expediency’ inherent in Korean media coverage of PISA is one of the key impetuses of the growing influence of the OECD on the nation’s education landscape. The Korean government’s active responsiveness to PISA results, coupled with its efforts to introduce new educational reforms, has often been perceived by educational experts as a consequence of heightened OECD governance. However, this article notes that the local media’s reporting of specific PISA outcomes is often driven by political motives, giving rise to policy environments that align with their own preferences. This dynamic implies that various changes in Korean educational policies and agendas, ostensibly influenced by the governance of international organisations like the OECD, may, to some extent, be steered by ‘local voices’ echoed by domestic actors.

Moving forward, this study underscores the need for future research studies in diverse national contexts, aimed at investigating the tactics employed by local actors, including the media, in the intricate local meaning-making process of international educational data and ideas. The media coverage patterns identified in Korean conservative and progressive media, as elucidated here, may also manifest in other countries, which should be the subject of future studies. Specifically, countries where intense political conflicts exist between conservatives and liberals, and/or where policymakers are highly receptive to external educational ideas, akin to the Korean situation, may exhibit similar media coverage patterns regarding PISA. Moreover, this article acknowledges that the mechanisms influencing the media’s tendency towards political expediency may vary contingent on diverse factors, including geopolitical forces and the historical context of right-left conflicts, all of which require in-depth scrutiny. This study further emphasises the significance of a comprehensive understanding of the local meaning-making process applied to international evidence as a crucial pathway towards developing effective evidence-based policymaking in an era inundated with international data sources.

Acknowledgements

The author expresses gratitude to the editors and anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments on the earlier draft of this article. I extend my appreciation to Dr. Felicia Genie Tersan for her valuable writing advice and companionship during the initial phases of crafting this paper at Teachers College, Columbia University.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Subeen Jang

Subeen Jang is a PhD student at the University of California, Los Angeles. Her research interests centre on the use of global evidence in policymaking, the cultural and political economy of policy borrowing and referencing, and power and capital dynamics within educational decisions.

Notes

1. Cho(sun daily)-Joong(Ang daily)-Dong(−A daily)’, ‘Han(kyoreh News)-Kyung(hyang News)-Oh(my News)’

2. Gangnam is one of the richest districts in Seoul known for intense education fever.

References

- The Academy of Korean Studies. (n.d.). Encyclopedia of Korean culture: National assessment of academic achievement. https://encykorea.aks.ac.kr/Article/E0074725

- Alterman, E. (2003). What liberal media? The truth about bias and the news. Basic Books.

- An, S. (2010, December 8). Neglect of elite education… top students’ achievements are falling [In Korean]. Chosun Daily. https://www.chosun.com/site/data/html_dir/2010/12/18/2010121800034.html

- Araujo, L., Saltelli, A., & Schnepf, S. V. (2017). Do PISA data justify PISA-based education policy? International Journal of Comparative Education and Development, 19(1), 20–34. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCED-12-2016-0023

- Auld, E., & Morris, P. (2016). PISA, policy and persuasion: Translating complex conditions into education ‘best practice. Comparative Education, 52(2), 202–229. https://doi.org/10.1080/03050068.2016.1143278

- Bagdikian, B. H. (2004). The new media monopoly. Beacon Press.

- Baroutsis, A., & Lingard, B. (2017). Counting and comparing school performance: An analysis of media coverage of PISA in Australia, 2000–2014. Journal of Education Policy, 32(4), 432–449. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2016.1252856

- Baroutsis, A., & Lingard, B. (2019). Headlines and hashtags herald new ‘damaging effects’: Media and Australia’s declining PISA performance. In A. Baroutsis, S. Riddle, & P. Thomson (Eds.), Education research and the media: Challenges and possibilities (pp. 27–46). Routledge.

- Bendix, R. (1978). Kings or people: Power and the mandate to rule. University of California Press.

- Covert, T. J. A., & Wasburn, P. C. (2007). Measuring media bias: A content analysis of Time and Newsweek coverage of domestic social issues, 1975-2000. Social Science Quarterly, 88(3), 690–706. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6237.2007.00478.x

- Crome, J. (2022). Panic and stoicism: Media, PISA and the construction of truth. Policy Futures in Education, 20(7), 828–839. https://doi.org/10.1177/14782103211064660

- Daily, J. (2004, December 22). Support elite education [In Korean]. JoongAng Daily. https://news.joins.com/article/427963

- D’Alessio, D., & Allen, M. (2000). Media bias in presidential elections: A meta-analysis. Journal of Communication, 50(4), 133–156. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2000.tb02866.x

- Dotson, D. M., Jacobson, S. K., Kaid, L. L., & Carlton, J. S. (2012). Media coverage of climate change in Chile: A content analysis of conservative and liberal newspapers. Environmental Communication, 6(1), 64–81. https://doi.org/10.1080/17524032.2011.642078

- Grek, S. (2008). PISA in the British media: Leaning tower or robust testing tool?. Centre for Educational Sociology, University of Edinburgh.

- Grek, S. (2009). Governing by numbers: The PISA ‘effect’ in Europe. Journal of Education Policy, 24(1), 23–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680930802412669

- Grey, S., & Morris, P. (2018). PISA: Multiple ‘truths’ and mediatised global governance. Comparative Education, 54(2), 109–131. https://doi.org/10.1080/03050068.2018.1425243

- Groseclose, T., & Milyo, J. (2005). A measure of media bias. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 120(4), 1191–1237. https://doi.org/10.1162/003355305775097542

- Gwak, S. (2019, December 4). Korean students’ academic achievements are declining for over 10 years [In Korean]. Chosun Daily. https://www.chosun.com/site/data/html_dir/2019/12/04/2019120400160.html

- Gwak, S., & Son, H. (2019, December 4). Korea is in danger of falling outside 10th place … China sweeps first place in all areas [In Korean]. Chosun Daily. https://www.chosun.com/site/data/html_dir/2019/12/04/2019120400173.html?utm_source=naver&utm_medium=original&utm_campaign=news

- Herman, E. D., & Chomsky, N. (1988). Manufacturing consent: The political economy of the mass media. Pantheon Books.

- Hong, J. (2013, December 18). Another war [In Korean]. Dong-A Daily. https://www.donga.com/news/article/all/20131218/59616612/1

- Hong, S. (2004, December 22). Discovering the gifted from the lower grades of elementary school [In Korean]. Dong-A Daily. https://www.donga.com/news/article/all/20041222/8141817/1

- Hu, Z. (2022). Local meanings of international student assessments: An analysis of media discourses of PISA in China, 2010-2016. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education, 52(3), 419–439. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057925.2020.1775553

- Hwang, G. (2010, December 8). The academic achievement of Korean students is the highest among OECD countries [In Korean]. Dong-A Daily. https://www.donga.com/news/article/all/20101208/33139623/1

- Iyengar, S. (1990). Framing responsibility for political issues: The case of poverty. Political Behavior, 12(1), 19–40. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00992330

- Iyengar, S., & Kender, D. R. (1982). News that matters: Television and American opinion. University of Chicago Press.

- Jang, J. (2019, December 19). Ranking of media activities in 2019 based on big data [In Korean]. Bigta News. https://www.bigtanews.co.kr/news/articleView.html?idxno=5214

- Jung, S., & Oh, Y. (2007, December 2). The 7th curriculum killed science education [In Korean]. Chosun Daily. https://www.chosun.com/site/data/html_dir/2007/12/02/2007120200600.html

- Kim, Y. (2017, August 25). Fearing to become like the Lee Hae-chan generation, the Kim Sang-gon generation roars [In Korean]. Chosun Daily. https://www.chosun.com/site/data/html_dir/2017/08/25/2017082500180.html

- Lichter, S. R., Rothman, S., & Lichter, L. S. (1990). The media elite. Hastings House.

- Liu, J. (2019). Government, media, and citizens: Understanding engagement with PISA in China (2009–2015). Oxford Review of Education, 45(3), 315–332. https://doi.org/10.1080/03054985.2018.1518832

- Lundahl, C., & Serder, M. (2020). Is PISA more important to school reforms than educational research? The selective use of authoritative references in media and in parliamentary debates. Nordic Journal of Studies in Educational Policy, 6(3), 193–206. https://doi.org/10.1080/20020317.2020.1831306

- Martens, K. (2007). How to become an influential actor – the ‘comparative turn’ in OECD education policy. In K. Martens, A. Rusconi, & K. Lutz (Eds.), Transformations of the state and global governance (pp. 40–56). Routledge.

- McCombs, M., & Shaw, D. (2007). The agenda-setting function of mass media. In O. Boyd-Barret & C. Newbold (Eds.), Approaches to media: A reader (pp. 153–163). Hodder Arnold.

- Nam, Y. (2016, December 7). Spike in underperforming male students… lagging behind female students in math and science [In Korean]. JoongAng Daily. https://www.joongang.co.kr/article/20971902

- News, K. (2019, December 4). Blaming the progressive superintendent for the decline in academic achievement? [In Korean]. Kyunghyang News. https://www.khan.co.kr/opinion/editorial/article/201912042049015

- OECD. (2020). PISA 2018 results (volume V): Effective policies, successful schools. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/ca768d40-en

- Oh, Y. (2019, December 3). Declining reading scores ‘for 12 years’… Korean students have lower life satisfaction [In Korean.]. Chosun Daily. https://www.chosun.com/site/data/html_dir/2019/12/03/2019120303200.html?utm_source=naver&utm_medium=original&utm_campaign=news

- Park, C. (2017, December 14). Increasing weight of ‘experimental assessment’ in science classes to 50% [In Korean]. Hankyoreh News. https://www.hani.co.kr/arti/society/schooling/257138.html

- Park, C. (2019, December 12). Schools only focus on subject grade levels… is there any class not caring about grades? [In Korean]. Kyunghyang News. https://www.khan.co.kr/national/education/article/201912120600045

- Park, S. (2010, December 31). Chosun Daily insists on elite education. Is that a good idea? [In Korean]. Ohmy News. http://www.ohmynews.com/NWS_Web/View/at_pg.aspx?CNTN_CD=A0001489951&CMPT_CD=SEARCH

- Peng, Y. (2018). Same candidates, different faces: Uncovering media bias in visual portrayals of presidential candidates with computer vision. Journal of Communication, 68(5), 920–941. https://doi.org/10.1093/joc/jqy041

- Pizmony-Levy, O. (2018). Compare globally, interpret locally: International assessments and news media in Israel. Globalisation, Societies & Education, 16(5), 577–595. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767724.2018.1531236

- Saltelli, A. (2017, June 12). International PISA tests show how evidence-based policy can go wrong. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/international-pisa-tests-show-how-evidence-based-policy-can-go-wrong-77847

- Santos, Í., Carvalho, L. M., & Portugal e Melo, B. (2022). The media’s role in shaping the public opinion on education: A thematic and frame analysis of externalisation to world situations in the Portuguese media. Research in Comparative & International Education, 17(1), 29–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/17454999211057753

- Saraisky, N. G. (2015). Analyzing public discourse: Using media content analysis to understand the policy process. Current Issues in Comparative Education, 18(1), 26–41. https://doi.org/10.52214/cice.v18i1.11526

- Schriewer, J. (1990). The method of comparison and the need for externalization: Methodological criteria and sociological concepts. In J. Schriewer & B. Holmes (Eds.), Theories and methods in comparative education (pp. 25–83). Lang.

- Schriewer, J., Ed. (2000). Discourse formation in comparative education. Peter Lang D. https://doi.org/10.3726/978-3-653-01100-5

- Shin, H., & Joo, Y. (2013). Global governance and educational policy in Korea: Focusing on OECD/PISA [In Korean]. Korean Journal of Educational Research, 51(3), 133–159.

- Song, J. (2019a, December 5). Basic academic skills deficit among poor students is three times greater compared to wealthier students [In Korean]. Kyunghyang News. https://www.khan.co.kr/national/education/article/201912032223005

- Song, J. (2019b, December 3). Domestic students’ reading, mathematics, and science performance is among the top in OECD [In Korean]. Kyunghyang News. https://www.khan.co.kr/national/education/article/201912031700011

- Steiner-Khamsi, G. (2003). The politics of league tables. Journal of Social Science Education, 2(1), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.4119/jsse-301

- Steiner-Khamsi, G. (Ed.). (2004). The global politics of educational borrowing and lending. Teachers College Press.

- Steiner-Khamsi, G. (2014). Cross-national policy borrowing: Understanding reception and translation. Asia Pacific Journal of Education, 34(2), 153–167. https://doi.org/10.1080/02188791.2013.875649

- Strömbäck, J. (2011). Mediatization and perceptions of the media’s political influence. Journalism Studies, 12(4), 423–439. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2010.523583

- Sutcliffe, S., & Court, J. (2005). Evidence-based policymaking: What is it? How does it work? What relevance for developing countries?. Overseas Development Institute. https://odi.org/en/publications/evidence-based-policymaking-what-is-it-how-does-it-work-what-relevance-for-developing-countries

- Takayama, K. (2008). The politics of international league tables: PISA in Japan’s achievement crisis debate. Comparative Education, 44(4), 387–407. https://doi.org/10.1080/03050060802481413

- Takayama, K. (2009). Politics of externalization in reflexive times: Reinventing Japanese education reform discourse through “Finnish PISA success. Comparative Education Review, 54(1), 51–74. https://doi.org/10.1086/644838

- Takayama, K., Waldow, F., & Sung, Y. K. (2013). Finland has it all? Examining the media accentuation of ‘Finnish education’ in Australia, Germany and South Korea. Research in Comparative & International Education, 8(3), 307–325. https://doi.org/10.2304/rcie.2013.8.3.307

- Thomas, S. (2006). Education policy in the media: Public discourses on education. Post Pressed.

- Waldow, F. (2017). Projecting images of the ‘good’ and the ‘bad school’: Top scorers in educational large-scale assessments as reference societies. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education, 47(5), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057925.2016.1262245

- Waldow, F., & Steiner-Khamsi, G. (Eds.). (2019). Understanding PISA’s attractiveness: Critical analyses in comparative policy studies. Bloomsbury Academic. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781350057319

- Waldow, F., Takayama, K., & Sung, Y. K. (2014). Rethinking the pattern of external policy referencing: Media discourse over the ‘Asian tigers’ PISA success in Australia, Germany and South Korea. Comparative Education, 50(3), 302–321. https://doi.org/10.1080/03050068.2013.860704

- Yun, G. (2019, December 31). The power of innovative education raised student happiness [In Korean]. Ohmy News. http://www.ohmynews.com/NWS_Web/View/at_pg.aspx?CNTN_CD=A0002600549&CMPT_CD=SEARCH

- Yun, J. (2013, December 26). Top in ‘performance’, bottom in ‘interest in studies,’ Korean students are not happy [In Korean]. Ohmy News. http://www.ohmynews.com/NWS_Web/View/at_pg.aspx?CNTN_CD=A0001937711&CMPT_CD=SEARCH