ABSTRACT

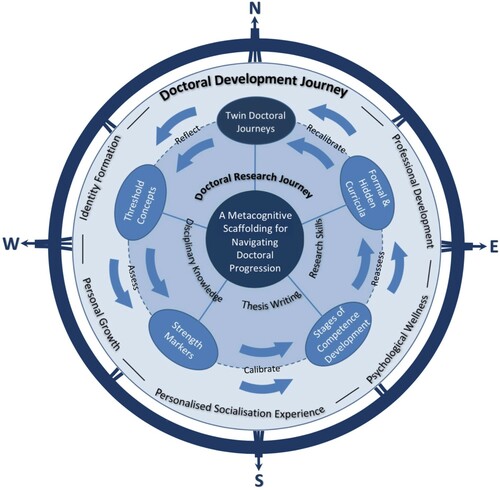

This conceptual paper contributes to a broader perspective on doctoral experience via a synthesis of several crucial concepts during the doctoral journey. The first part discusses the core challenges customarily confronting doctoral scholars due to the distinct PhD genre leading to introducing the main conceptual base. Metacognition, being central to doctoral knowledge creation, is explored through the stages of competence development and against the competing notions often faced by PhD scholars: the Imposter Syndrome and the Dunning-Kruger Effect. Drawing upon these metacognitive concepts, the implications of crossing competence stages during lengthy, non-linear doctoral trajectories in a high-performance academic culture are further explored. While recognising associated challenges, this paper also highlights a range of available tools, resources, and skillsets useful for the transitional period, doctoral learning progression and eventual completion. This paper has, therefore, interwoven and unified key doctoral experience concepts with a view to proposing a conceptual framework for a doctoral self-management strategy. This holistic framework, a form of metacognitive scaffolding for navigating the PhD experience, is likened to a ‘compass’ for trekking both the research landscape and the doctoral development landscape. In the absence of a doctoral ‘map’, employing one’s personal metacognitive ‘compass’ can empower doctoral scholars to manage a potentially complex experience – by identifying essential praxes to scaffold the entire doctoral process through iterative cycles of reflection, calibration and recalibration of strategic reflection and personal evaluation of one’s progression.

Introduction

Every long journey arguably deserves a map, and this includes doctoral learning journeys. Ironically, while contextualised in ‘a high-performance academic culture’, doctoral studies are often characterised by unstructured journeys with multiple possible routes capable of branching out in different directions (Angervall Citation2016, 235; Lovitts Citation2005). Since these journeys are interlaced with high expectations, challenges and other distinctive features integral to the doctoral processes (e.g. ‘a solitary affair’, ‘a long road’), scholars’ ‘unmapped journeys’ can intensify uncertainty, confusion and even trepidation (Cotterall Citation2013, 180, 185; Elliot, Reid, and Baumfield Citation2016, 2). Moreover, the requirements for successful outcomes remain high (Angervall Citation2016; Lovitts Citation2005). The entire doctoral experience is expected to yield not just a doctoral qualification, but to develop a scholarly identity (if aspiring to work in academia) and to acquire transferable skills (if transitioning to industry post-PhD) (Cotterall Citation2013; McAlpine, Skakni, and Pyhalto Citation2020). Additionally, an overall transformative learning experience, while maintaining a healthy work-life balance and sustaining sound psychological well-being during a PhD, are unspoken goals (Elliot et al. Citation2020).

Given the unique trajectories fraught with ambiguities, complexities and delightful surprises surrounding the doctoral experience, this paper investigates a conceptual nexus of the doctoral threshold model, prevailing doctoral practices and challenges, and relevant metacognitive concepts. This leads to a proposition for a conceptual framework on the essential praxes (or effective practices) for navigating the PhD while considering the existence of two distinct but interlinked landscapes. This framework can serve as a ‘compass’ to guide and enthuse doctoral scholars to employ metacognitive scaffolding as they trek on an ‘unmapped’ and complex journey, with support from doctoral allies, i.e. supervisors, researcher developers and Graduate Schools but also from doctoral scholars’ wider communities – both within and outwith academia.

An examination of distinctively challenging doctoral experience

In this paper, understanding the doctoral experience begins with an appreciation of the challenges inherent in its landscape – an ideal starting point leading to the discussion of specific challenges prevalent in the doctoral context. While a doctorate is traditionally viewed as a requirement for an academic career, doctoral graduates are increasingly sought after outside academia for their expert research and critical skills, too (Gemme and Gingras Citation2012). Their acquired cognitive and metacognitive competence in identifying problems, when combined with the resolution-seeking nature of research activates generation of new insights into knowledge and practice (Zohar Citation1999) that is also highly valued in industry. Irrespective of their post-PhD destination – academia, industry or elsewhere – their enhanced capacity for cognitive work gives them an edge.

In this connection, Berman and Smyth (Citation2015) argue for the centrality of metacognition (i.e. insights into one’s own mental processes) in a PhD. Accordingly, cognitive and metacognitive tools are at the crux of supporting doctoral scholars’ higher order thinking (or complex learning) skills, but equally, in facilitating abstract thinking in order to create or generate ‘new knowledge’ (128). Aligned with this idea, successful doctorates are often accompanied by and/or exhibited by demonstration of higher order thinking, specifically the acquisition of ‘doctoral-level research skills’, ‘research self-efficacy’ or research independence – from designing a study, through to fieldwork and research dissemination (Berman and Smyth Citation2015; Lovitts Citation2005; Overall, Deane, and Peterson Citation2011, 792). These ideas reinforce the role of cognitive work both during and post-PhD. Whereas Barnacle (Citation2005, 179) elaborates the concept of ‘becoming a researcher’ by stressing that the doctorate is a degree in philosophy, it can also be argued that in elucidating what underpins the PhD process itself as well as its expected outcomes, the psychological lens has a lot to offer, too. There are two reasons: (a) the doctoral process heavily entails the use and development of both cognitive and metacognitive competences (Berman and Smyth Citation2015) and (b) the biggest doctoral-related challenges are ‘psychological’ in nature (Deconinck Citation2015).

In this respect, higher order thinking competence springs from and is arguably, strengthened by years of intense doctoral work, moulded by the PhD’s genre. A PhD – being a long and lonely endeavour prone to uncertainty and confusion and high requirements for success – serves as both a challenge and a reward in itself (Angervall Citation2016; Berman and Smyth Citation2015; Cotterall Citation2013). To illustrate, despite the ‘turbulent nature of doctoral research’ – with prevailing stress, depression, anxiety, student debt, vague job prospects affecting mental health – 38% of 6300 participants nevertheless reported experiencing ‘sustained satisfaction’ in the last two years (see www.nature.com). Deep-seated enjoyment seemingly explains scholars’ propensity to work for over 40 hours per week. This suggests how the first major challenge among doctoral scholars, i.e. the intellectual challenge, may doubly serve as an intrinsic motivator (see Skakni Citation2018). A doctoral thesis, as an intellectual masterpiece, mandates scholarly arguments, with a view to generating novel insights, while working in partnership with a supervisory team (Benmore Citation2016). The doctorate’s business is primarily to generate and transfer knowledge ensuring originality in knowledge contribution (Barnacle and Mewburn Citation2010; Lee Citation2018; Skakni Citation2018). Essentially, it aims to push the boundaries of knowledge – a considerable intellectual challenge commensurate with all the expectations of the ‘pinnacle of formal education’ (Berman and Smyth Citation2015, 130).

Apart from the intellectual challenge, it has been recognised that those who pursue doctoral education are likely to have previously demonstrated acumen and capacity for academic achievement, motivating further acceptance of challenging endeavours (Lovitts Citation2005). Scholars come with varied personal, educational and professional work experience and may have even played diverse roles prior to becoming a PhD scholar (Holbrook et al. Citation2014). Often, each of these elements serves as a source of personal strength fuelling the PhD drive. Doctoral scholars’ combination of strengths – observed via their cognitive competence, research literacy, language proficiency, received learning orientation, level of persistence and individual or collective values – reveals great diversity. Such strengths may also, at times, pose personal challenges. Holbrook et al. (Citation2014, 329), describe how a priori experience from ‘preconceived ideas’ may subsequently inform PhD expectations, e.g. views on supervision, learning environments, PhD demands. There is a danger, however, that such ideas – innocuous as they are – can lead to misaligned or mismatched doctoral expectations leading to frustration, dissatisfaction, even dropout. These personal challenges are highly individualised and are largely dependent upon the person’s trajectory. They are informed by a range of factors including academic, social, and cultural background; disciplinary or research competence; or personal circumstances, e.g. in full-time or part-time learning mode, local or international learner, living alone or with family (Elliot et al. Citation2016). In turn, the distinct impact of personal challenges depends on each scholar’s context.

Interestingly, despite recognition of earlier academic success, work and unique life experiences, Devos et al. (Citation2017) point out how a PhD necessitates reverting to a ‘learner’ status, which may involve conceding to the unknown and unfamiliar components of the doctoral study. Becoming a learner again mandates managing new challenges presented by doctoral work, despite the fact that doing so might be uncomfortable and/or linked to something previously encountered. This idea is somehow supported by Belavy et al.’s (Citation2020) assertion that ‘previous academic outcomes and research training [were] unrelated to outcomes’ (1). With the long doctoral process, a specific challenge may inevitably converge with other challenges at the emotional, social or psychological level, thus exacerbating what could already be a stressful experience (Deconinck Citation2015). Working closely with the supervisory team tends to shape scholars’ expectations based largely on an open understanding that doctoral scholars are the real ‘drivers’ of their research (Benmore Citation2016). At times, however, conflicting expectations arise between doctoral scholars and their supervisors leading to the former’s (mis)perception of being in a relationship that is not supportive or where only minimal support is offered (Holbrook et al. Citation2014). The sentiment conveyed in McAlpine and McKinnon’s (Citation2013, 267) argument is a reflection of this, i.e. the diversity in the quality of the supervisory experience makes the supervision component to be deemed ‘the most variable of variables’ in the doctoral experience. Likewise, Lovitts (Citation2005) assertion of the necessity of a ‘critical transition’ is worth noting, as doctoral scholars ‘make a crucial shift’ from previously being a ‘consumer’ and transmitter of knowledge to a producer of knowledge. Doctoral transition denotes moving away from structured modules, course outlines, prescribed reading lists, and lectures and assessments, all in ‘controlled environments’, towards learning in ‘unstructured contexts’ that generates ‘uncertain processes’ (138). This then makes entering a doctorate analogous to a steep learning curve that mirrors the immensity of the challenge of the learning adjustment entailed in the distinct doctoral genre.

Finally, a specific challenge may potentially arise from the doctoral learning context, over which participants may have very little control – referred to as a contextual challenge. To illustrate, the lack of local research group communities of scholars may exacerbate the perceived or potential shortcomings of the lack of doctoral structure or support at the institutional level. For instance, when comparing the UK model with other doctoral models, whereas mandatory taught courses, teaching experience and publishing experience may be embedded in the latter’s doctoral process, this is not standard in the UK setting. In turn, doctoral scholars in the US and Scandinavian countries often leverage from their models, in which scholars’ learning and socialisation experience are integral to being part of a research community – arguably crucial to their learning experience.Footnote1 The community itself is a channel for learning as doctoral scholars work with supervisors, postdocs and other scholars in the field. Access to regular and direct interactions in a scholarly community afford academic and non-academic learning opportunities, e.g. scholarly identity development, acquisition of research experience, and social and psychological support (Cai et al. Citation2019; Mantai Citation2017). Non-academic support becomes even more crucial when various forms of doctoral challenges start to accrue, or unprecedented challenges happen (e.g. a pandemic). In the UK, with the exception of those working in Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM), the majority of doctoral scholars tend to miss what these research communities can offer. It is arguably crucial to stress these existing contextual differences, e.g. the presence or absence of local research groups or communities, the mandatory (or non-mandatory) nature of course participation and publication experience, as well as the differing quality, focus or extent of doctoral provision at the institutional level, can make a qualitative difference to the PhD experience.

Altogether, a combination of intellectual, personal, learning adjustment, and contextual-related challenges contributes, shapes, and enriches the tapestry of experience fashioning the composition of each doctoral journey – making each doctoral venture inherently distinct. The multifaceted and highly context-dependent nature of the doctoral experience prompts a systematic consideration of the metaphorical ‘unmapped’ doctoral journeys. This then suggests that preparing scholars who venture on doctoral journeys may require strategic, personalised, holistic approaches involving the use of metacognitive tools to enable them to see ‘how the different pieces fit together’ (Deconinck Citation2015, 369). We will now turn to what might be regarded as a key piece of the doctoral puzzle, i.e. threshold concepts in doctoral education.

Threshold concepts in doctoral education

While ‘maps’ may not exist, there remain doctoral expectations and general standards to be reached. There are proposed threshold concepts that each doctoral scholar needs to master to achieve a successful and transformative PhD experience (Deconinck Citation2015; Lee Citation2018). These threshold concepts, i.e. skilful use of argument, theorising a research framework, knowledge creation, analysis and interpretation of research data and an in-depth comprehension of research paradigms, are intended to equip doctoral scholars with the requisite knowledge, skills, values and dispositions (Kiley Citation2009, Citation2019; Kiley and Wisker Citation2009) to scaffold scholars’ emergence as independent and competent researchers (Overall, Deane, and Peterson Citation2011). As in other disciplines, fully understanding each threshold concept is a prerequisite for doctoral scholars ‘crossing’ the threshold and progressing with learning. Linking to Meyer and Land’s (Citation2006) original conceptualisation of threshold concepts, the capacity for threshold-crossing can be characterised initially, by four criteria: (a) ‘transformative’ (i.e. learners’ understanding has transformed their views on disciplinary knowledge and their role as learners); (b) ‘irreversible’ (i.e. the state in which learners’ full comprehension of the concept is not likely to be reversed); (c) ‘integrative’ (i.e. learners’ capacity for integrating seemingly disparate knowledge into ‘an integrated whole’; and (d) ‘troublesome’ (i.e. learning being highly challenging that can restrict learners’ experience to ‘being in a liminal space’). Two more considerations were added latterly: ‘discursive’ and ‘reconstitutive’. Whereas ‘discursive’ indicates how learners’ enhanced grasp of the concept manifests itself via the way they talk about the concept, ‘reconstitutive’ conveys the occurrence of the ontological shift that permits genuine learning leading to integration and conceptualisation even of diverse forms of information (Kiley Citation2019, 140–141; Timmermans and Meyer Citation2019).

Likewise, doctoral scholars are expected to secure an advanced disciplinary understanding, research competence, a high level of reasoning, project management and time management – equally crucial components for conducting research. On top of this, translating everything they have learned into scholarly writing is in itself ‘an essential research skill’ (Deconinck Citation2015, 370; Thomson and Kamler Citation2016). Wisker (Citation2019) points out additional complexity entailed by academic writing, particularly in lengthy doctoral writing, e.g. several stages embedded in the writing process; or experience of competing ‘blockages’ and ‘breakthroughs’ (217). Since a PhD is largely research-based, a doctoral scholar’s brilliance is often enhanced or weakened by their academic writing (Wisker Citation2019) as it is via scholars’ written work that other scholars judge a study’s overall quality. Unsurprisingly, Timmermans and Meyer (Citation2016), stress that key to supervisors’ remit includes being doctoral scholars’ academic ‘writing teachers’.

Despite the threshold concepts being clearly conceptualised, scholars’ depth of understanding and capacity to apply these concepts are not necessarily aligned, particularly when doctoral scholars and supervisors’ perspectives are examined. This may not come as a surprise since supervisors have amassed deeper and broader knowledge of the subject since their own PhD completion; through a number of years of research experience (and possibly supervisory experience), they have obtained deeper insight. During the EARLI biennial conference, Holbrook, O’Toole and Fairbairn (Citation2019) elucidated the differing levels of cognition and metacognition in operation when doctoral scholars are compared with their more experienced supervisors. The differences in how scholars of various levels of experience apply cognitive processes raise invaluable insights, with implications for the supervisory direction and guidance taking place during supervisory meetings.

In the next two sections, competence development and the competing notions of Imposter Syndrome and the Dunning-Kruger Effect will be examined to highlight the cognitive and metacognitive impact of such concepts on doctoral scholars’ progress, and by extension, on supervisor and institutional provision.

Stages of competence development

Earlier discussion pertaining to stages of competence development (i.e. unconscious incompetence; conscious incompetence; conscious competence and unconscious competence) has been associated with the field of counselling psychology, particularly with reference to the professional development of counsellors (Castle and Buckler Citation2018; Donati and Watts Citation2005). Nevertheless, as we argued elsewhere, this conceptual framework equally facilitates a deeper metacognitive reflection of the tricky transitional experience that the majority of doctoral scholars inevitably go through as part of the doctoral learning process (see Elliot et al. Citation2020). While the terminology for this framework seemingly denotes a deficit model, the terms employed aptly offer an analogy to depict the gradual progression in competence development, e.g. doctoral threshold concepts – particularly acquired aptitude on argumentation, knowledge production, or research paradigm comprehension (Kiley Citation2009, Citation2019; Kiley and Wisker Citation2009). Moreover, there are invaluable doctoral principles to be learned; despite doctoral scholars being smart individuals, Deconinck (Citation2015) asserts that ‘what is lacking is perhaps a good understanding of what a PhD is’ (360), in which supervisors’, researcher developers’, Graduate Schools’ and the doctoral community’s contribution is indispensable. Therefore, in developing competences, acknowledging one’s deficiency and practising humility are both invaluable and practically useful since there are certain aspects in the doctoral process that entail not even knowing what questions to raise, if the question is worth asking or whether the question is, at all, answerable (Deconinck Citation2015). Due to the personalised nature of this journey, however, no two scholars take the same length of time when transitioning from one stage of competence development to another.

Starting with unconscious incompetence, this term often pertains to doctoral scholars’ status as novice researchers who at this stage, are probably still learning many of the ‘tricks of the trade’, including those that they are not yet aware of. Unsurprisingly, they might not have yet even realised a deficiency in certain doctoral areas. For example, given the contested notions and multiple conceptual understanding of critical thinking, doctoral scholars’ understanding of this concept may initially be both blurred and lacking in depth, severely restricting their capacity to employ critical thinking in academic writing. In the next stage, i.e. conscious incompetence, greater understanding of the doctoral standards comes with the realisation of the various knowledge and skills that they still need to master (Elliot et al. Citation2020). This stage can be exceptionally daunting as it likewise generates pressure to accomplish other tasks deemed essential in the doctorate. Linking it to critical thinking, through supervisors’ feedback, doctoral scholars are increasingly made aware that the critical component remains absent from their writing. A feasible explanation could be that at this stage, their understanding has not yet necessarily been transferred into academic writing practice. As doctoral scholars continue to learn broadly and deeply, greater awareness of their shortcomings could lead simultaneously to experiencing both pressure and disappointment.

A steady progression from the second stage of competence development results in experiencing conscious competence, where greater strides are made in terms of the acquisition of ‘more knowledge, insights, skills, and understanding of the various facets of the doctorate, e.g. threshold concepts’ (Elliot et al. Citation2020, 11; Kiley Citation2009, Citation2019; Kiley and Wisker Citation2009). With the competence gained through becoming more consciously cognisant and equipped with cognitive tools, it is likely that doctoral scholars have now reached the stage where their confidence has strengthened and their expertise blossomed, channelled via a clearer, critical and authorial writing voice. Finally, through continuous advancement of growth and development in knowledge and skills pursued individually, in collaboration with supervisors, or through participation in wider scholarly activities, doctoral scholars are predicted to arrive at the final stage, i.e. unconscious competence. Citing Evans (2011) and Kamler and Thomson (2014), Mantai (Citation2017) explains how ‘researcher identification in the PhD is … an amalgamation of a variety of developmental opportunities that may often appear mundane and insignificant’ (647). Likewise, Mantai (Citation2017) asserts that ‘the lines between formal and informal, social and personal spaces where professional researcher growth occurs are blurred’ (Mantai Citation2017). This suggests that scholarly activities – comprising formal (e.g. article publication, conference presentations); semi-formal (e.g. fieldwork research, general writing); and informal (e.g. scholarly discussion with peers) – can complementarily shape and strengthen researchers’ identity development. For many scholars, achieving the highest level of competence typically requires years of ‘continuous use of the desired skills leading to a type of proficiency that comes almost naturally and/or with much less effort’ (Elliot et al. Citation2020, 11). Such competence may mean acquisition of a sufficient level of proficiency to teach a skill. With numerous knowledge and skills vital for doctoral-level research, competence development varies, where at the end of the doctorate, scholars achieve unconscious competence for many, but not necessarily for all desired skills.

In exploring the four stages of competence development, a focus on the first two is of greater relevance in this paper. The transition from the unconscious incompetence to the conscious incompetence stage is arguably the trickiest in the doctoral journey. The realisation of one’s lack of readiness to meet the very high doctoral standards can be viewed as a steep learning curve for many doctoral scholars. In turn, the move to the conscious incompetence stage may then ironically entail fear, frustration, even distress while tacitly feeling ‘already defeated’ due to how high the metaphorical doctoral bar is, how much of a gap exists between their perceived levels of competence/incompetence and how little time they have to reduce such a gap. Deconinck (Citation2015) has illuminated this ‘psychological’ struggle by explaining how not even knowing what questions to ask can make scholars ‘feel stupid’ and psychologically-challenged, particularly for those who are both highly motivated and very smart (361). Under this huge pressure, many doctoral scholars may not be fully cognisant of what, how and/or where they can seek support in order to move from the conscious incompetence to conscious competence stage, which is aligned to the feeling of ‘being in a liminal space’ prior to crossing the threshold (Kiley Citation2009, Citation2019; Kiley and Wisker Citation2009). At a stage where doctoral scholars experience mixed negative emotions, e.g. being overcome by the fear of the unknown, feeling overwhelmed and intimidated, inter alia, this unsurprisingly leads to occurrence of Imposter Syndrome (Deconinck Citation2015).

Imposter syndrome vs the Dunning-Kruger Effect

There are two well-known psychological phenomena that can add to an enhanced metacognitive understanding of the intellectually demanding and psychologically challenging doctoral journey. Starting with the Imposter Syndrome defined as –

A subjective experience of phoniness in people who believe that they are not intelligent, capable or creative despite evidence of high achievement, and who are highly motivated to achieve but live in perpetual fear of being ‘found out’ or exposed as frauds. (Colman Citation2015, 368)

Despite these two well-known psychological phenomena being in direct opposition to each other, both the Imposter Syndrome and the Dunning-Kruger Effect offer valuable insights in metacognitively understanding the potential impact on scholars. Albeit in different ways, both can act as psychological hindrances to doctoral scholars’ progress. Scholars’ mis-assessment of their actual competence may subsequently discourage them from seeking suitable support to develop and improve. In directly linking these two phenomena to the arguably tricky doctoral transition from unconscious incompetence to conscious incompetence, a recognition of both phenomena warrants doctoral scholars’ honest introspection and accurate evaluation of competences as a vital step to facilitate their competence progression.

Tools, resources and skillsets during doctoral scholars’ transition, learning progression and overall experience

The literature has shown how a range of challenges is linked to the genre of the doctoral process itself. A consolidation of the threshold concepts in doctoral education, the stages of competence development and the competing notions of the Imposter Syndrome and the Dunning-Kruger Effect, offer holistic and metacognitive perspectives and subsequently, an insightful appreciation of the complex process characterising each doctoral scholar’s learning journey.

Notably, a lot of doctoral studies to date have considered concepts in relation to the initial transition, e.g. the multiplicity of factors underpinning doctoral scholars’ motivations and a priori experience, inter alia, as they embark on a doctorate (Holbrook et al. Citation2014; Skakni Citation2018). The initial transition period is crucial since it is where doctoral scholars are typically confronted with multiple and potentially overwhelming academic adjustments (Lovitts Citation2005) that can either serve as an impetus or a discouragement for the journey. From the beginning of the doctorate, scholars face mounting pressure to understand what the PhD entails, what disciplinary knowledge and research skills they need to equip themselves with to meet doctoral standards, and where and how to access the intellectual, psychological and physical resources essential for the journey. Scholars arguably require metacognitive tools (Berman and Smyth Citation2015) in journey planning to manage effectively two crucial PhD facets. These two doctoral facets constitute the ‘twin’ journey, each with its own distinct and multi-faceted learning demands: (a) doctoral level research and (b) scholars’ doctoral development.

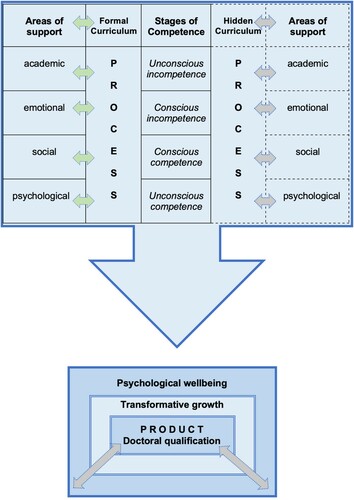

Since the PhD is a long journey, the overwhelming sentiments experienced at the beginning could be alleviated during doctoral progression, particularly as scholars increasingly understand and apply the required threshold concepts in doctoral education while gradually moving up the competence development ladder (Elliot et al. Citation2020; Kiley Citation2009, Citation2019; Kiley and Wisker Citation2009). Additionally, scholars’ appreciation of academic manoeuvres, acquisition of disciplinary and research understanding through meaningful discussions with supervisors, other scholars, and proactive participation in formal, semi-formal and informal scholarly activities as well as enhanced recognition of both standard doctoral provision and the hidden curriculum in doctoral education are likely to strengthen not only scholars’ confidence, but also support their trajectory towards becoming a competent, even an ‘excellent researcher’ (Angervall Citation2016, 225; Mantai Citation2017) ().

Figure 1. A conceptual framework of the formal and the hidden curricula within doctoral education using the four stages of competence (Elliot et al. Citation2020, 13).

In this connection, it is worth highlighting how the doctoral learning experience encompasses a much wider scope that is beyond the conventional channels of learning via the official processes or the formal curriculum. Instead, it can be argued that there co-exists the hidden curriculum in doctoral education, or the unofficial channels of genuine learning typically acquired within and/or beyond the physical and metaphorical walls of academia (see Elliot et al. Citation2020). While it is outside the scope of this paper to offer an in-depth discourse on the subject, it is sufficient to stress how leveraging the hidden curriculum, to support and reinforce what the formal curriculum offers, can enrich (and/or complicate) scholars’ management of time, energy and resources. Equally, although scholars could access various types of knowledge, resources and tools to develop their knowledge base and required skillsets, a persisting lacuna in understanding any threshold concept, or a blockage experienced in crossing the competence stages (possibly due to the Imposter Syndrome or the Dunning-Kruger Effect) may obstruct, even thwart doctoral learning progression.

The non-linear trajectory of doctoral education from beginning to end has been widely acknowledged (Angervall Citation2016; Lovitts Citation2005). The highly diverse nature of the ‘unmapped’ doctoral experience, with all its surprises, ambiguities and complexities, possibly increases substantially, the intellectual and psychological struggles by those who embark on this journey (Deconinck Citation2015). With countless decisions required at every step of the doctoral process – from the outset, throughout the whole experience, until the end of the journey – the one factor that seemingly underpins the whole experience is a series of multi-faceted learning for the ‘twin’ doctoral journey. Arguably, both sets of learning, i.e. the research and the doctoral development components, form a self-management strategy, are distinct yet strongly interlinked. Whereas the research landscape might be tailored to the scholar’s doctoral level research development, there also conceptually exists a doctoral development landscape to advance scholars’ doctoral development (see ). Therefore, in successfully completing a PhD, a metacognitive scaffolding to assist a suitably effective self-management strategy for the journey is arguably an indispensable tool.

Praxes for the ‘Twin’ doctoral journey: a conceptual perspective

In an attempt to consolidate the many concepts and contributory factors of the doctoral experience, a unified conceptual perspective of the entwined praxes is proposed here. Having such a holistic perspective is deemed critical in navigating the stereotypically ‘unmapped’ doctoral journey. Although it may not make the journey shorter or easier, ascertaining how large the gap is (in terms of disciplinary knowledge, research skills, soft skills, dispositions, etc.) serves as a crucial point in journey planning. It may also prompt a more proactive and tailored engagement with supervisors, various scholarly communities and other key players in this journey, including those outside academia. This proposed conceptual framework, driven by a self-management strategy, has three underpinning strands. Firstly, achieving the ‘pinnacle’ of education calls for bright minds with cognitive capabilities and dispositions necessary to develop the skills and competence required for the doctorate (Berman and Smyth Citation2015). It was pointed out, however, that even bright minds need a strategy when managing their own journey for doctoral development (Deconinck Citation2015), or strategically planning a personalised journey that can sustain a high level of motivation amongst scholars until completion.

Secondly, doctoral scholars are presented with numerous opportunities for growth and development via the formal and the hidden curricula (Elliot et al. Citation2020). Fully recognising the crucial work of doctoral supervisors, with complementary support from graduate convenors, researcher developers and doctoral provision at the institutional level, they together comprise the formal curriculum. Doctoral learning, however, is not solely dependent on these formal aspects; they are complemented, even reinforced by the co-existence of the hidden curriculum (Elliot et al. Citation2020). As an illustration, although a sound comprehension and application of doctoral threshold concepts (e.g. knowledge creation) are typically initiated by learning through the official channels (i.e. the formal curriculum), one’s understanding is often deepened via informal conversations with other scholars (i.e. the hidden curriculum) (see Mantai Citation2017). This second strand particularly stresses how interdependence between both curricula is at the crux of doctoral education.

Thirdly, the distinct nature of doctoral education can explain the multiplicity of the challenges that confront those who pursue it. Deconinck (Citation2015) has pointed out not only the intellectual challenges commonly associated with doctoral education but also the psychological challenges which might explain the increasingly reported impact on doctoral researchers’ mental health and well-being (Barry et al. Citation2018; Byrom et al. Citation2020; Levecque et al. Citation2017). Perhaps, the accumulation of ‘unmapped’ and non-linear doctoral trajectories, when combined with doctoral scholars’ (initial) dearth of competence against the high threshold concepts and type of learning embedded with random challenges and experiences of disturbing psychological phenomena, can reinforce the pressure (Mackie and Bates Citation2019). In turn, continuing intellectual and psychological challenges from the initial transition, through to learning progression until completion, may elucidate why doctoral scholars find themselves ‘lost’ in their journey, at times, causing them to discontinue (Angervall Citation2016; Deconinck Citation2015; Lovitts Citation2005).

Taking these three key strands into consideration, doctoral scholars are, therefore, likely to benefit from a tool to help map their journey, bearing in mind the twin praxes for both doctoral research and doctoral development. Such a journey may comprise: (a) a metacognitive and holistic understanding of the doctoral requirements; (b) awareness of how to tap into the vast learning opportunities from formal and hidden curricula; and (c) application of the essential praxes for addressing the multiple doctoral challenges.

Wisker (Citation2019) suggests that doctoral scholars ‘are always renewing, reviewing and moving on’ (224). From the outset, a doctoral journey requires an iterative cycle of reflection, self-assessment and recalibration for continuous learning and reinforced improvement as depicted in . An awareness of and reflection on the doctoral thresholds as a starting point, aims to identify personal strength markers (e.g. expert organisational skills; capacity for creative thinking; academic writing proficiency) that are invaluable for the doctorate. Authentic reflection, perhaps in conjunction with the supervisor, is intended to lead to honest deliberation, indicating where doctoral scholars need to improve (perhaps significantly). Such self-assessment then prompts calibration in terms of purposefully harnessing formal and hidden curricula. Benefits and rewards from these co-existing curricula serve as critical conduits for more focused learning, projected to improve confidence and increase competence. Acquired competence is expected to lead to a greater sense of focus and continues to inform doctoral scholars’ further assessment and recalibration following a build-up of doctoral competences. Due to the extensive range of knowledge and skills essential for doctoral studies, this cycle is likely to continue throughout the entire doctoral period, until doctoral completion, or even beyond. The course of scholarly development continues after all, long after the doctorate is over.

It is noteworthy that whereas the number of required learning iterations may vary quite radically from one doctoral scholar to another, endorses a shared factor at the crux of the cycle of essential doctoral praxes, i.e. doctoral scholars need to adopt a self-directed metacognitive approach, serving as scaffolding, to understanding what underpins the doctoral process. Promoting a metacognitive and holistic understanding of the doctoral processes that embed a cyclical approach to learning and development may then require applying the principles of ‘psychoeducation’ for both doctoral scholars and their supervisors. Borrowing from the psychological field, psychoeducation principles can promote a better orientation of scholars’ understanding and usage of the higher order thinking processes that can be employed in doctoral learning (Zohar Citation1999). The process proposed in , while cyclical, offers a focused and strategic approach that encourages not merely a sense of direction but capability to pursue, make and manage strategic decisions – in support of a personalised ‘twin’ doctoral journey. This conceptual paper strongly advocates a robust metacognitive grasp of the ‘twin’ doctoral journey as well as a manageable and personalised effort to reflect, calibrate and recalibrate for both the research and doctoral development components. While this framework is not intended to provide a detailed direction or ‘a personal map for actions’ for individually complex and unmapped endeavours, it serves as a metaphorical ‘compass’ to support doctoral scholars’ journeys and progression along the way, with support from doctoral allies. Likened to a cyclical explanation of the value of positive emotions (Fredrickson Citation2003), a personalised framework may lead to scholars’ deeper metacognitive understanding, encourage a reflective disposition, set targets and sustain their confidence, while constantly assessing their progress as part of the iterative learning cycle. This can, arguably, be described as genuinely empowering for the doctoral journey, and even post-PhD.

Conclusion

A doctoral education is an intellectually and psychologically demanding and complex journey that is nonetheless filled with excitement. While offering a concrete map is impossible due to the PhD genre, the proposed conceptual framework can serve as a ‘doctoral compass’ to guide scholars to move in the right direction – sustaining their motivation and passion along the way until completion. The same factors may also discourage these scholars from withdrawing while indirectly safeguarding their psychological well-being. An apparent limitation of the proposed conceptual framework, i.e. a metacognitive scaffolding tool, as a self-management strategy for the ‘twin’ doctoral journey, is that this framework necessitates further investigation via empirical research. With this in mind, this framework raises a few questions. For example, what are the doctoral pedagogies that doctoral supervisors and researcher developers can employ to make threshold concepts more explicit? What practical strategies will support doctoral scholars to move from the tricky unconscious incompetence to the conscious incompetence stage while retaining their zeal to learn? Can a supportive doctoral community encourage scholars’ ongoing reflection on their progress in both doctoral research and doctoral development? Its strength, on the other hand, is that drawing upon recognised crucial concepts in doctoral education, and in turn connecting the dots, means that these novel insights into doctoral education offer comprehensive and holistic perspectives. While the ‘doctoral compass’ is primarily intended to empower doctoral scholars, it is equally intended to inspire action by other stakeholders. Responding to the questions raised by this framework necessitates adopting a joined-up approach, from supervisors, doctoral convenors, researcher developers, Graduate schools and institutions, with a view to enhancing existing doctoral provision.

Acknowledgements

To all doctoral scholars and colleagues from the University of Glasgow – thank you for the inspiration. Special thanks to Dr Rui He for her kind assistance in transforming my initial drawing of into a creative work of art.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 The arguments raised here originated from the author’s keynote address: ‘It’s about academia, but it’s not all about academia: Interconnected factors in understanding international doctoral researchers’ wellbeing’ at the University of Stavanger, Norway on 18th September, 2020.

References

- Angervall, Petra. 2016. “The Excellent Researcher.” Policy Futures in Education 14 (2): 225–37.

- Barnacle, Robyn. 2005. “Research Education Ontologies: Exploring Doctoral Becoming.” Higher Education Research & Development 24 (2): 179–88.

- Barnacle, Robyn, and Inger Mewburn. 2010. “Learning Networks and the Journey of ‘Becoming Doctor’.” Studies in Higher Education 35 (4): 433–44.

- Barry, Karen, Megan Woods, Emma Warnecke, Christine Stirling, and Angela Martin. 2018. “Psychological Health of Doctoral Candidates, Study-Related Challenges and Perceived Performance.” Higher Education Research and Development 37 (3): 468–83.

- Belavy, Daniel L., Patrick J. Owen, and Patricia M. Livingston. 2020. “Do Successful PhD Outcomes Reflect the Research Environment Rather Than Academic Ability?” PLoS ONE 15 (8): e0236327.

- Benmore, Anne. 2016. “Boundary Management in Doctoral Supervision: how Supervisors Negotiate Roles and Role Transitions Throughout the Supervisory Journey.” Studies in Higher Education 41 (7): 1251–64.

- Berman, Jeanette, and Robyn Smyth. 2015. “Conceptual Frameworks in the Doctoral Research Process: A Pedagogical Model.” Innovations in Education and Teaching International 52 (2): 125–36.

- Byrom, Nicola C., Larisa Dinu, Ann Kirkman, and Gareth Hughes. 2020. “Predicting Stress and Mental Wellbeing among Doctoral Researchers.” Journal of Mental Health. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/09638237.2020.1818196.

- Cai, Liexu, Dely L Dangeni, Rui He Elliot, Jianshu Liu, Kara A. Makara, Emily-Marie Pacheco, Hsin-Yi Shih, Wenting Wang, and Jie Zhang. 2019. “A Conceptual Enquiry Into Communities of Practice as Praxis in International Doctoral Education.” Journal of Praxis in Higher Education 1 (1): 11–36.

- Callender Aimee A., Ana M. Franco-Watkins, and Andrew S. Roberts. 2016. “Improving metacognition in the classroom through instruction, training, and feedback.” Metacognition Learning 11: 215–235.

- Castle, Paul, and Scott Buckler. 2018. Psychology for Teachers. 2nd ed. London: Sage.

- Colman, Andrew M. 2015. Oxford Dictionary of Psychology. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Cotterall, Sara. 2013. “More Than Just as Brain: Emotions and the Doctoral Experience.” Higher Education Research & Development 32 (2): 174–87.

- Deconinck, Koen. 2015. “Trust Me, I’m a Doctor: A PhD Survival Guide.” The Journal of Economic Education 46 (4): 360–75.

- Devos, Christelle, Gentiane Boudrenghien, Nicolas Van der Linden, Assaad Azzi, Mariane Frenay, Benoit Galand, and Olivier Klein. 2017. “Doctoral Students’ Experiences Leading to Completion or Attrition: A Matter of Sense, Progress and Distress.” European Journal of Psychology of Education 32: 61–77.

- Donati, Mark, and Mary Watts. 2005. “Personal Development in Counsellor Training: Towards a Clarification of Inter-Related Concepts.” British Journal of Guidance & Counselling 33 (4): 475–84.

- Elliot, Dely L., Vivienne Baumfield, Kate Reid, and Kara Makara. 2016. “Hidden treasure: Successful international doctoral students who found and harnessed the hidden curriculum.” Oxford Review of Education 42 (6): 733–748.

- Elliot, Dely L., Soren S. E. Bengtsen, Kay Guccione, and Sofie Kobayashi. 2020. The Hidden Curriculum in Doctoral Education. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Elliot, Dely L., Kate Reid, and Vivienne Baumfield. 2016. “Searching for ‘a Third Space’: A Creative Pathway Towards International PhD Students’ Academic Acculturation.” Higher Education Research & Development 35 (6): 1180–95.

- Fredrickson, Barbara, L. 2003. “The Value of Positive Emotions: the Emerging Science of Positive Psychology is Coming to Understand why It’s Good to Feel Good.” American Scientist 91: 330–5.

- Gemme, Brigitte, and Yves Gingras. 2012. “Academic Careers for Graduate Students: A Strong Attractor in a Changed Environment.” Higher Education 63: 667–83.

- Holbrook, Allyson, and O’Toole Hedy Fairbairn. 2019, 16 August. “Key Considerations in Interpreting PhD Examiner Feedback.” 18th European Association for Research on Learning and Instruction (EARLI) Conference, Aachen, Germany.

- Holbrook, Allyson, Kylie Shaw, Jill Scevak, Sid Bourke, Robert Cantwell, and Janene Budd. 2014. “PhD Candidate Expectations: Exploring Mismatch with Experience.” International Journal of Doctoral Studies 9: 329–46.

- Kiley, Margaret. 2009. “Identifying Threshold Concepts and Proposing Strategies to Support Doctoral Candidates.” Innovations in Education and Teaching International 46 (3): 293–304.

- Kiley, Margaret. 2019. “Threshold Concepts of Research in Teaching Scientific Thinking.” In Redefining Scientific Thinking for Higher Education: Higher-Order Thinking, Evidence-Based Reasoning and Research Skills, edited by Mari Murtonen and Kieran Balloo, 139–55. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Kiley, Margaret, and Gina Wisker. 2009. “Threshold Concepts in Research Education and Evidence of Threshold Crossing.” Higher Education Research & Development 28 (4): 431–41.

- Kirschner, Paul A., and Carl Hendrick. 2020. How Learning Happens: Seminal Works in Educational Psychology and What They Mean in Practice. London: Routledge.

- Kruger, Justin, and David Dunning. 1999. “Unskilled and Unaware of it: How Difficulties in Recognizing One’s own Incompetence Lead to Inflated Self-Assessments.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 77 (6): 1121–34.

- Lee, Anne. 2018. “How Can we Develop Supervisors for the Modern Doctorate?” Studies in Higher Education 43 (5): 878–90.

- Levecque, Katia, Frederik Anseel, Alain De De Beuckelaer, Johan Van der Heyden, and Lydia Gisle. 2017. “Work Organization and Mental Health Problems in PhD Students.” Research Policy 46 (4): 868–79.

- Lovitts, Barbara E. 2005. “Being a Good Course-Taker is not Enough: A Theoretical Perspective on the Transition to Independent Research.” Studies in Higher Education 30 (2): 137–54.

- Mackie, Sylvia Anne, and Glen William Bates. 2019. “Threshold Concepts in Research Education and Evidence of Threshold Crossing.” Higher Education Research & Development 28 (4): 431–41.

- Mantai, Lilia. 2017. “Feeling Like a Researcher: Experiences of Early Doctoral Students in Australia.” Studies in Higher Education 42 (4): 636–50.

- McAlpine, Lynn, and Margot McKinnon. 2013. “Supervision – the Most Variable of Variables: Student Perspectives.” Studies in Continuing Education 35 (3): 265–80.

- McAlpine, Lynn, Isabelle Skakni, and Kirsi Pyhalto. 2020. “PhD Experience (and Progress) is More Than Work: Life-Work Relations and Reducing Exhaustion (and Cynicism).” Studies in Higher Education. Published online

- Meyer, Jan H. F., Ray Land, eds. 2006. Overcoming Barriers to Student Understanding: Threshold Concepts and Troublesome Knowledge. London: Routledge.

- Overall, Nickola C., Kelsey L. Deane, and Elizabeth R. Peterson. 2011. “Promoting Doctoral Students’ Research Self-Efficacy: Combining Academic Guidance with Autonomy Support.” Higher Education Research & Development 30 (6): 791–805.

- Pennycook, Gordon, Robert M. Ross, Derek J. Koehler, and Jonathan A. Fugelsang. 2017. “Dunning-Kruger Effects in Reasoning: Theoretical Implications of the Failure to Recognise Incompetence.” Psychonomic Bulletin & Review 24: 1774–84.

- Skakni, Isabelle. 2018. “Reasons, Motives and Motivations for Completing a PhD: A Typology of Doctoral Studies as a Quest.” Studies in Graduate and Postdoctoral Education 9 (2): 197–212.

- Thomson, Pat, and Barbara Kamler. 2016. Detox Your Writing: Strategies for Doctoral Researchers. London: Routledge.

- Timmermans, Julie A., and Jan H. F. Meyer. 2019. ““A Framework for Working with University Teachers to Create and Embed ‘Integrated Threshold Concept Knowledge’ (ITCK) in Their Practice.” International Journal for Academic Development 24 (4): 354–68.

- Wisker, Gina. 2019. “Developing Scientific Thinking and Research Skills Through the Research Thesis or Dissertation.” In Redefining Scientific Thinking for Higher Education: Higher-Order Thinking, Evidence-Based Reasoning and Research Skills, edited by Mari Murtonen and Kieran Balloo, 203–32. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Zohar, Anat. 1999. “Teachers’ Metacognitive Knowledge and the Instruction of Higher Order Thinking.” Teaching and Teacher Education 15: 413–29.