ABSTRACT

Although the nature of the academic profession and related career advancement has been well documented, little empirical evidence has been provided on the professional agency that academics employ to advance from one academic rank to another. Adopting an agency focus, this study therefore investigates what strategies academics adopt when seeking promotion. Through semi-structured interviews with 37 participants from a representative Australian university, the study identifies promotion seeking as a two-stage process involving two clusters of six interrelated strategies. A Framework of Agency in Academic Promotion (FAAP) is proposed, demonstrating how, with motivation to climb the career ladder, academics engage in both self-oriented and socially oriented strategies, initially to ‘become promotable’ and then to write a promotion application. The study confirms and elaborates the role of professional agency in academic promotion, supports the argument that strategies are an important enabler of agency, and contributes to the scarce empirical literature in this field. Academics and their managers, developers and mentors can use the FAAP model to craft promotion strategies and career development plans.

Introduction

Career advancement, the upward progression of one’s career, represents an important achievement in a working life. However, for academics, this journey is fraught with difficulty (Brew et al. Citation2017), not only because of the current state of academic labour markets (Larsen and Brandenburg Citation2022), but because the academic profession is complex and challenging with no single model or pathway for advancement (C. Whitchurch, Locke, and Marini Citation2023). Knowledge about academic career development, and the agency of academics in creating that career, remains patchy (Zacher et al. Citation2019), but we know that career advancement is typically self-initiated and that internal promotion remains the most popular route, compared to moving to another university (Francis and Stulz Citation2020).

By achieving internal promotions, academics gain internal recognition of their contributions, external reputation and monetary rewards, as well as being able to further their academic activities within a familiar context. However, the processes involved in applying for promotion are daunting (Francis and Stulz Citation2020), and academics who fail to earn a promotion tend to feel stigmatised. Reapplying after an initial rejection not only involves putting together new documentation, but also better navigation of the application process itself. We therefore chose to investigate the strategic use of individual agency within the internal promotion process, aiming both to shed light on a practical problem for academics and to make a theoretical contribution through the development of a framework of agency in academic promotion.

Despite increased competition in academic labour markets and the rising precariousness of academic and research work (Leathwood and Read Citation2022), there is still room for individual agency (C. Whitchurch, Locke, and Marini Citation2023), even where academic careers are very strongly institutionally configured and ‘scripted’ (Dany, Louvel, and Valette Citation2011) and where the ‘strategic academic’ is a production of a specific evaluation and promotion culture (Kenny Citation2017). To examine the strategic use of agency specifically in internal academic promotion, we conducted a small empirical study in an Australian university, interviewing 37 staff members about their application experiences and strategies developed. The study particularly addresses the need to identify effective promotion strategies (Zacher et al. Citation2019) and thus contributes to the growing body of literature on career advancement in higher education.

Promotion as part of socialisation into the academic organisation

Socialisation into the applicant’s own academic organisation is essential to successful internal promotion because internal promotion is based upon demonstrated ability and merit, and the fulfilment of expectations regarding research output, teaching performance and contributions to the university (C. Whitchurch, Locke, and Marini Citation2023). In turn, these expectations are shaped according to broad national requirements (Finkelstein Citation2015) and each university’s expectations and structural support for career advancement (Arokiasamy et al. Citation2011). Socialisation into the academic profession ranges from graduate study and mentoring to undertaking internal service roles and generating forms of output (Flowers Citation2006). While universities can support the neophyte in these socialisation processes through deliberate organisational socialisation tactics (Kowtha Citation2018), individuals’ ongoing exercise of professional agency is an essential component (Wanberg and Kammeyer-Mueller Citation2000). For example, academics can proactively build relationships and networks, and seek information and feedback from colleagues and mentors (Batistič and Kaše Citation2015). Such proactive behaviour necessarily involves strategic agency, which is the central interest of this study.

Agency as facilitator in career advancement

Academic career agency is a relatively new area of study (O'Meara, Terosky, and Neumann Citation2008), recently defined as taking strategic actions, or assuming perspectives, or ways of thinking, to accomplish career outcomes (O'Meara and Stromquist Citation2015). For Kuvaeva (Citation2019), such agency is context-specific, shaped by local constraints and supports, and it also involves both personal and professional agency. Personal agency refers to academics’ abilities to build relationships in their family that help manage their multiple personal roles (e.g. articulating their own needs and priorities, allocating household tasks among family members). Professional agency refers to capacity in fulfilling various professional roles and career objectives (e.g. in academic promotion, administrative leadership, and research productivity), although exercising it effectively is necessarily influenced by constraints on personal agency. In addition, based on gender roles and beliefs, male and female academics may exercise these two forms of agency differently (Hakiem Citation2022), hence their chances of being promoted may differ (Cooper Citation2019). Other factors may also influence the promotion process such as biases in evaluation (Auster and Prasad Citation2016) and variations in disciplinary expectations (Durodoye et al. Citation2020).

Clear evidence exists that when academics enact agency, and when there are no insurmountable structural or contextual barriers (O'Meara, Terosky, and Neumann Citation2008), they can achieve favourable professional outcomes, including career satisfaction, academic rank promotion, administrative leadership promotion, and research productivity (Kuvaeva Citation2019). Existing studies have focused on how academics exercise agency for scholarly learning (Neumann Citation2009) or career actions of particular cohorts, notably female academics (Angervall and Beach Citation2020), academics in certain disciplines (e.g. Roberts and Hilty Citation2017), Indigenous academics (Staniland, Harris, and Pringle Citation2020), and early career (Sutherland Citation2017) or senior academics (Blackstone and Gardner Citation2017). The literature on a ‘whole of university’ perspective on agency is scarce (O'Meara Citation2015; O'Meara and Stromquist Citation2015), with studies citing agency behaviours (e.g. Mahat and Tatebe Citation2019) lacking empirical data. This study examines how both men and women academics from various career stages and disciplines exercise their professional agency in seeking internal promotion.

Strategies as enabler of agency

An academic’s abilities to assume and enact agency are influenced by structural factors, such as departmental contexts (Campbell and O’Meara Citation2014) or a specific leadership program (Templeton and O'meara Citation2018) and also by personal factors, such as individuals’ agentic perspectives (O'Meara Citation2015), professional networks (O'Meara and Stromquist Citation2015), and strategies (Terosky and O'Meara Citation2011). In considering the nature of strategy in the context of scholarly learning, Neumann (Citation2009, 140) noted:

Strategy transforms professors’ agency from abstract desire – to engage in scholarly learning – to specific action, thought through and pieced together yet revised as needed, so that professors may realise their desires concretely. Strategy emerges from desire, wilful agency, and directed (ideally, reflective) action. It is proactive and optimistic, rooted in assumptions of self-efficacy and possibility. Thus, strategy activates agency.

Research design

The study adopts a qualitative approach (Merriam and Tisdell Citation2015). The overarching research question is: What strategies do academics employ to advance from a lower to a higher academic rank? Expanding on this we ask:

What do academics need to do to achieve promotion?

How do academics need to behave toward others to achieve promotion?

Research context

The Australian university model of promotion is similar to the UK, Canadian and New Zealand models, represented as a ladder (Caplow and McGee Citation1958) because it features officially regulated ascending academic positions, unlike the US system, with its early intense selection to tenure-track positions (time-limited posts) leading to tenured positions (Enders and Musselin Citation2008). The Australian government regulates hiring and promotion through a national set of standards detailing the skills, knowledge and abilities for academics at each step (Larkin Citation2016). The Minimum Standards for Academic Levels (MSALs) describe five levels of appointment: Level A (Tutor/Associate Lecturer), Level B (Lecturer), Level C (Senior Lecturer), Level D (Associate Professor) and Level E (Professor). Levels B and C, D, and E are analogous to the Assistant Professor, Associate Professor, and Professor, levels, respectively, in the US system. In 2021, by current duties classification, 30% of the total FTE academic staff across all universities in Australia work at level D & E; 23% work at level C; and 47% at levels A and B (Department of Education and Training (DET) Citation2020).

Although hiring and promotions decisions need to be based on the MSALs, the promotion process itself varies across universities in terms of promotion committees, interview processes, and promotion guidelines. outlines the promotion process at the research site, a public university considered medium-sized in Australia, and ranked within the top 300 on the 2022 Academic Ranking of World Universities (ARWU).

Academics must clearly evidence not only the work they have done but also its quality, impact, and progression, reflecting a ‘performativity’ system (Kenny Citation2017). At the research site, an internal promotions committee, comprising faculty-wide representation, is appointed to assess the written applications. Applications for promotion are judged solely on the paperwork, and evaluation may not include what committee members know of the applicant beyond what is in the application. Furthermore, unless deemed necessary by the committee in some rare special cases, neither the applicant nor their manager are invited to attend an oral interview or appear before the committee. These procedures mean that all relevant evidence must be supplied as part of the written application, making its preparation central to promotion-seeking.

With neoliberal reforms in higher education in the past decades, all Australian universities have applied corporate managerial practices (Kenny Citation2017). Universities, faculties, and individual academics must demonstrate their research and teaching efficiency and productivity. With the Australian research engagement and impact evaluation exercise experimented in 2010, all Australian universities have been under pressure to enhance their research output, excellence, and impact. In this context, at the case study university, academics are expected not only to teach well (their traditional mission) but also to publish research in high-ranking outlets. Promotion has been based heavily on academics’ research performance and outputs. It is also important to note that promotion not available in general to casual or sessional academic staff.

Participant sampling

Using a purposive ‘total’ sampling strategy (Patton Citation2002) we invited participation from all promotion committee members and 207 academics promoted during 2012–20, resulting in 37 respondents: 33 academics, 3 committee members who are academics, and one human resources professional, also a committee member. Among the academic participants, ten had initially failed before subsequently succeeding. The number of participants at each academic level roughly represents the university’s overall promotion rate at each level. provides participant details by gender, discipline, and academic level.

Table 1. Selected demographic details of participants.

Data collection

The primary method of data collection was semi-structured interviews lasting 45–60 min. These allowed in-depth discussion of participants’ promotion strategies, and enabled us to engage actively with participant responses within the prearranged structure. Following general questions about educational background and career, we asked about actions, and social abilities perceived as necessary to gain promotion.

Data analysis

We transcribed all 37 interviews and used the qualitative analysis software program NVivo to manage the data. To ensure rigorous analysis and theorisation, we applied the Gioia Methodology, a systematic approach to develop new concepts and articulate grounded theory (Gioia, Corley, and Hamilton Citation2013). This involves identifying first order concepts, second order themes and overarching aggregate dimensions.

To generate first order concepts, we read each transcript and coded all items that addressed the overall research question, adhering to informants’ terms. To create second order themes, we grouped similar or related first order concepts and labelled each group with a theme name. We went ‘back and forth’ with grouping and re-organising first order concepts until we reached ‘theoretical saturation’ – no additional themes being found from the first order concepts.

To create ‘aggregate dimensions’, we explored whether second order themes related to one another in ways that could contribute to useful conceptualisation of promotion seeking. We assembled first order terms, second order themes, and aggregate dimensions into two distinct ‘data structures’. To further build theory, we explored possible interrelationships among the second order themes and aggregate dimensions, drawing on studies of academic socialisation and agency.

Results

The Gioia analytic process established academic promotion seeking in this setting as a two-stage strategic process involving two distinctive clusters of strategies.

A two-stage strategic process

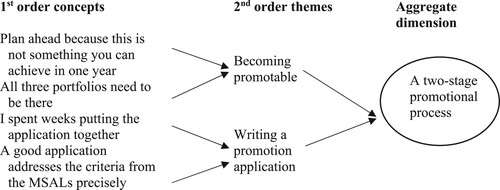

An initial series of first order concepts indicated two related themes and one aggregate dimension (see ).

‘Becoming promotable’ involved a range of precursor activities taking place over months and often years prior to making an application, while writing a promotion application involved a shorter more intense period. Both were dependent on being motivated to apply for promotion, not just initially but over time, representing a significant underlying presence throughout the data.

The six strategies typically comprised several sub-strategies, as detailed in the following.

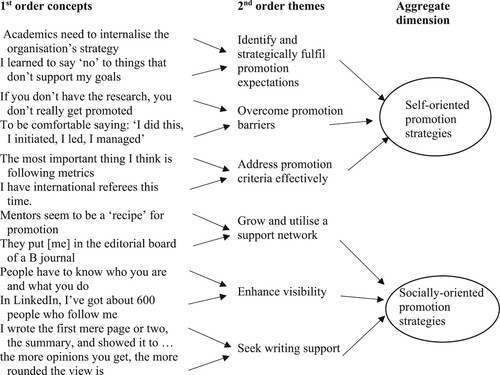

Self-oriented promotion strategies

Self-oriented strategies refer to inward focused actions that academics do largely by themselves, but which may also lead them to seek support from others.

Identify and strategically fulfil promotion expectations

A core strategy for most participants was to work out exactly what was expected from them to become promotable and then actively to find ways to fulfil those expectations. Failure to appreciate the requirement to gain a PhD, for example, delayed the promotion of F1 (Level E), who remained at Level C for 14 years despite attracting large research grants, producing numerous publications, and achieving widespread recognition. She was promoted to Level D as soon as she obtained her PhD. Others applied all the following sub-strategies.

Make a ‘far-thinking’ career plan

Most participants emphasised the importance of being clear in their career goals and being ‘strategic’, ‘far-thinking’ and ‘forward thinking’. ‘Plan ahead, because this is not something you can achieve in one year’ (F18, Level D). Committee members also confirmed the importance of ‘career trajectory’, ‘career planning’, and ‘actively managing their career’ (M5, Level E).

Grow performance strategically

Most participants took deliberate actions to identify and address their performance gaps: ‘I’ve been specific in what I apply my time to’ (F5, Level B). Participants who failed in the promotion process responded strategically to feedback provided, addressing gaps in their performance and attending closely to procedural requirements, for example, engaging internationally (F6, Level E) or seeking more service roles (M13, Level D).

Align performance with organisational goals

Committee members identified published university missions, visions and strategic plans as key guideposts for academic promotion: ‘If we see staff deliberately aligning to those, it’s only going to assist them in their promotion application’ (M5 CM, Level E). However, ‘if you’ve been here ten years, and the organisation has changed direction and you have not changed with it, you’re unlikely to get promoted’ (M4, Level E).

Establish and maintain portfolio evidence: Successful applicants for promotion deliberately collected performance evidence over an extensive period. For example, ‘I kept everything that shows evidence of performance of outstanding capabilities, of excellence – because that’s what your application must have’ (F7, Level D). F18 (Level D) recommended her staff to immediately file any evidence to support development in a portfolio area, as well as its social impact.

Overcome promotion barriers

Participants expressed a need to consciously learn ways of overcoming two types of promotion barrier: the ‘portfolio barrier’ and meeting cultural expectations.

Balance portfolio requirements

Failure to achieve promotion was typically due to failure to adequately demonstrate achievements in each area of the promotion portfolio: teaching, research, and service. Most unsuccessful applicants mentioned the struggle to improve research performance while having to keep up with the workload of teaching and leadership. ‘For those staff members who are teaching only it is really difficult to get the promotion’ (F12 failed B to C). ‘My leadership and my teaching were fine with them, but my research didn’t get me over the line’ (F6, Level E). Some mentioned dropping a leadership position to focus on research.

Meet cultural expectations

Being able to signal one’s achievements as part of a promotion strategy was considered vital, but many, especially women from certain cultural backgrounds, reflected on their discomfort in talking up their strengths: ‘You want to be moderate, or you want to be humble. So, it’s a lot of struggling inside as well (F4, Level C). The University’s women’s mentoring program was seen as valuable in overcoming this barrier.

Address promotion criteria effectively

This strategy is particularly relevant in writing the promotion application. Individuals who addressed the criteria effectively tended to follow the institutional guidelines, provide strong evidence, and invest enough time in preparing the application.

Follow institutional guidelines

All interviewees noted the usefulness of the university guidelines which expressed expectations for performance at five levels, based on the national MSALs. They ‘studied the guidelines very closely’ (F9, Level C) and ‘structured [the] application around the guidelines’ (M7, Level C), addressing key performance indicators (F1, Level E). F9, Level C, who failed in her promotion application, acknowledged, ‘I did not capture the matrix’.

Provide strong evidence

Most participants highlighted the importance of showing one’s work impact clearly with supporting evidence, including international validation (M1, Level E; F9, Level C).

Invest enough time in preparing applications

Of the academics who failed in their first attempts at promotion, several acknowledged that they had not invested enough time in writing the application. ‘I rushed that promotion application … . And I didn’t get up’ (F6, Level E). Participants noted: ‘you would have to start thinking about a year ahead about what you want to put in’ (F4, Level C) or alternatively, ‘two years is a good timing to get everything to put together’ (M16, Level D).

Socially oriented promotion strategies

Socially oriented strategies relate both to drawing on other people as a resource for achieving promotion and making oneself known as a person suitable for promotion.

Grow and utilise a support network

Growing and utilising a support network was seen as a participatory strategy, a learning strategy, a means of becoming noticed as part of the community, and a way to receive mentoring.

Reach out

Reaching out to ‘surround yourself with academic friends, not just in the university, but outside’ (M13, Level D) was considered essential but not always easy:

I was not very strategic about building relationship with other people. I was too busy developing the courses and making sure that students were satisfied. (F16, Failed Level B-C)

Obtain mentors and learn from them

All participants identified mentoring as key to their promotion success: ‘Mentors seem to be a recipe for promotion’ (F2, Level E); ‘this person worked with me hands-on and changed the game’ (M13, Level D). Such mentors needed to be both ‘supportive’ (M17, Level B) and ‘capable’ (F4, Level C). Lack of a mentor (F14, Level E) or the shortage of the ‘right mentor advice’ (F1, Level E) was suggested as a reason for promotion failure.

Follow pathways made available through the network

Members of support networks offered various pathways that applicants could follow to fulfil their performance gaps strategically. For example, one participant had in their network someone who ‘put [me] on the editorial board of a B journal’ (F4, Level C); others received coaching on overcoming specific promotion barriers.

Enhance visibility

Successful applicants made their work performance known both within and beyond the university – hosting visitors from industry, government, university, and community (F3, Level E) and gaining LinkedIn followers. Some unsuccessful participants attributed their failure to lack of visibility.

People have to know who you are and what you do, even if you have the metrics. In my first failed effort, I think that was probably a visibility issue. I was away for a couple of years, and then applied for promotion when I came back so I hadn't established myself’. (M13, Level D)

Seek writing support

Having grown a support network, participants found they needed to keep using it across both stages of promotion seeking.

Learn self-presentation skills

Mentors typically provided mentees with their own previous successful promotion applications, modelling self-presentation skills, for which they also gave coaching. F9, Level C said that although her first application was ‘honest and true’, she probably ‘underplayed’ her contributions. So, in her second attempt, instead of saying ‘I wrote this [curriculum component]’, she put ‘I was a part of the leadership group’.

Seek feedback on the written application

Most participants asked someone to review their applications at an early stage, and several indicated surprise at the benefits, changing their approach to the task. ‘I wrote the first mere page or two, the summary, and showed it to […] who said ‘Well, you’ve got to tell more of a story of you as a person, not what you’ve done since the last promotion’ (M1, Level E).

Summary of strategies

This study has identified six self-oriented and socially oriented strategies for achieving internal promotion, along with associated sub-strategies. Self-oriented strategies refer to inward focused actions that academics do largely by themselves, whereas socially oriented strategies relate both to drawing on other people as a resource for achieving promotion and making oneself known as a person suitable for promotion. Use of these strategies is subject to potential constraining or enabling factors, such as availability of suitable mentoring, clarity of institutional guidelines, and aspects of personal agency such as family responsibilities, and cultural characteristics. The strategies themselves are summarised in .

Table 2. Self-oriented and socially oriented promotion strategies.

A framework of agency in academic promotion

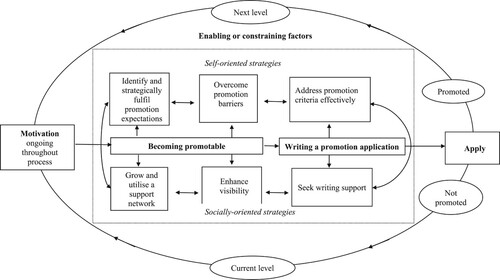

The preceding analysis foregrounds the importance of the identified strategies as instances of professional agency across a dynamic two-stage process: ‘become promotable’ and ‘write a promotion application’. Building on the data structures in and , we propose a Framework of Agency in Academic Promotion (FAAP), presented in .

The FAAP represents an interactive and multidimensional sequence and cycle of strategic action. The starting point for the model is ‘current level’. Following the arrow to the left around the outside of the model, being motivated to seek promotion, academics engage in self-oriented and socially oriented strategies first to ‘become promotable’ and then to ‘write a promotion application’. In this process, academics need to simultaneously work on identifying and fulfilling promotion expectations, developing and using a network, overcoming barriers and enhancing visibility. They then must continue to undertake these activities as they proceed to write their application, addressing the criteria and seeking writing support. Their application leads to either acceptance or rejection and to the applicant’s next cycle of promotion activity, as portrayed in the outer oval of the framework. At the core of the framework are six strategies interrelated both through their relevance to the end goal and through their orientation to self and society. These strategies and their associated sub-strategies all involve the use of professional agency, shaped by the strength of enabling or constraining factors in the institutional and personal environment. All also have potential outcomes that collectively facilitate success in promotion seeking.

We note that some academics may not be motivated to apply for promotion, either in general or after an unsuccessful promotion application. Such academics may disengage from this process, potentially after a ‘not promoted’ outcome. Further, some academics who have been promoted and who have reached the ‘next level’ may not be motivated to apply for promotion to the new next level. As such, the question of ‘motivation’ is an empirical one, to be considered on a case-by-case basis. This model applies to the context in which an academic is motivated to apply for promotion.

Discussion

In neoliberal environments focused on performativity and accountability (Kenny Citation2017), academic agency is seen as increasingly necessary in career advancement, so the present study contributes to this contemporary debate. By conceptualising promotion-seeking as a two-stage process involving both self-oriented and socially oriented strategies, the proposed Framework of Agency in Academic Promotion (FAAP) confirms the need for career self-management – an employee’s role in managing their own career by following their own strategic aims and visions (Greenhaus, Callanan, and Godshalk Citation2018). The FAAP model makes both theoretical and practical contributions to understanding academics’ professional agency in gaining internal promotion.

Theoretical contributions

The FAAP establishes promotion seeking as a two-stage process involving strategic investment in ‘becoming promotable’ followed by further strategic investment in writing and submitting a promotion application. The investment in ‘becoming promotable’ is prerequisite to a successful written application and is a long-term process that may span several years, also being dependent on an academic being motivated to apply for promotion and to maintain this motivation throughout the process. To manage this process effectively, academics in this study actively applied both self-oriented and socially oriented strategies across the two-stage promotion seeking process of ‘becoming promotable’ and ‘writing a promotion application’ providing all necessary evidence. By identifying the specific actions that academics undertake in climbing their career ladder, the study confirms the importance of individuals’ proactive use of agency in socialising into the academic profession (Wanberg and Kammeyer-Mueller Citation2000) in an ongoing way. Regardless of discipline, faculty, gender or career stage, the academics in this study proactively engaged in strategies aligned to organisational goals to advance their career. They ‘reconstructed’ their work conditions (e.g. deliberately dropping a leadership position) to achieve performance development goals (e.g. focusing more on research). They enhanced their visibility (e.g. volunteering to take committee roles outside universities) to forge their own ways to gain promotion.

The study suggests that academics who do not undertake the strategies identified in the FAAP may find their career advancement slowed. Having gone through one round of applying for promotion, Level C academics often realised the importance of being strategic, proactive, focusing time on work areas that count, and planning. In contrast, level D and E academics highlighted the importance of gaining leadership and visibility internationally. Thus, at different career stages, academics may exert different weighting on particular FAAP strategies.

The FAAP model affirms several concepts that other researchers have identified as critical for career development. For example, this study found that academics identify and strategically fulfil promotion expectations within their given context. Similarly, Jones and DeFillippi (Citation1996) identified ‘knowing what’ (opportunities, threats, and requirements) as a core ‘career intelligent’ competency, while Baker, Gonzales, and Terosky (Citation2020) suggested that, in crafting career development strategies, early career academics should consider their university’s distinctive contexts carefully. The present study also found that, to advance their career, academics grow and utilise a support network, aligning with studies by Heffernan (Citation2021) and O'Meara and Stromquist (Citation2015).

In addition to confirming key findings from existing studies, our study makes clear that, to climb the career ladder, academics must overcome constraints to exercising their professional agency, actively addressing promotion barriers connected to their own professional and/or personal circumstances. For example, in this era of ‘research performativity’ (Kenny Citation2017), academics with a teaching-focused or administration-heavy workload individually found ways to overcome the ‘portfolio barrier’ to enhance their research productivity and quality, without which their road to promotion would be blocked, as Dobele and Rundle-Theile (Citation2015) found in their study. At levels D and E, where academics must establish themselves as global figures in their field of research (Beigi, Shirmohammadi, and Arthur Citation2018), academics undertook various actions such as volunteering to take committee roles outside universities to enhance their visibility.

The actions referred to above suggest that these academics were engaged in developing ‘concertina-like’ career pathways (Whitchurch, Locke, and Marini Citation2021), responding both to an ‘internal script’ interested in promotion and an ‘institutional script’ setting out essential requirements for achieving such promotion. The career making in this study was more representative of strategically managing the institutional script than of ‘modulating’ or ‘massaging’ it as in the study by Whitchurch, Locke, and Marini (Citation2021, 642).

Practical implications

Given the strong individualistic narratives of a career in academia (C. Whitchurch, Locke, and Marini Citation2023), the Framework of Agency in Academic Promotion (FAAP) is significant in that it provides academics with insights for crafting personal career advancement strategies, particularly in identifying specific strategies they are not yet applying adequately. All unsuccessful participants neglected at least one of the FAAP strategies, but subsequently acted deliberately in their areas of deficit, such as promoting their visibility by taking more service and leadership roles, obtaining a mentor, or spending more time on writing their application. Thus, in seeking internal promotion, academics can use the FAAP as a planning tool to identify what strategies they should apply and/or prioritise to enhance their chance of success. Similarly, academic managers and mentors can use the FAAP to help academics review their promotion strategies, identify gaps in their strategy use, and develop relevant promotion plans. Human resource development professionals can use the FAAP in developing career planning and career building workshops for academics, while an organisational challenge for the future is to assist academics to develop the full range of strategic action identified in the FAAP. While this paper highlights the importance of academics’ self-oriented and socially oriented strategies in gaining internal promotion, participants also touched on certain structural and contextual obstacles that impeded successful strategy enactment, as reported previously by O'Meara, Terosky, and Neumann (Citation2008). We suggest that universities play a critical role in minimising such obstacles and in designing the internal promotion process to help academics ‘socialise’ into their institutions (Kowtha Citation2018). Based on this study, universities need to provide clear promotion application guidelines, support academics in telling their career stories and achievements, provide specific feedback to unsuccessful applications, and provide mentoring (Howe-Walsh and Turnbull Citation2014).

Limitations and suggestions for future research

While this study makes an original contribution to knowledge about professional agency in promotion seeking among academics, we acknowledge its limitations. While the study confirms the role of academics’ professional agency and strategies in seeking internal promotion, it does not take account of external or personal conditions over which they have no control. Study of constraining and enabling factors on the exercise of professional agency in the promotion seeking process would be invaluable. In addition, although the FAAP model represents agency in promotion of both male and female academics from both STEM and HASS and at different career stages, the dynamics of gender, discipline, and career stage within the FAAP remains a question for future research. Importantly, since this study is based only on a single university, such future research could identify factors that provide opportunities and/or restrictions on the exercise of professional agency in a variety of contexts, and also identify variations in promotion strategies depending on the specific job description, career stage, career ambition, university promotion criteria and the wider higher education context.

Conclusion

This study explored the ways in which academics employ professional agency to advance from a lower to a higher academic rank through internal university promotion processes. The focus was on the self-oriented and socially oriented strategies that participating academics and committee members perceived as critical, resulting in the proposed Framework of Agency in Academic Promotion (FAAP). We believe this model is theoretically significant not only through the identification of proactive promotion strategies, but because it indicates the importance of first ‘becoming promotable’ through strategic precursor actions and then continuing to act strategically in the writing of the promotion application. The FAAP demonstrates that academics seeking to advance their careers through promotion must maintain motivation and apply both self-oriented and socially oriented strategies over time.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Angervall, P., and D. Beach. 2020. “Dividing Academic Work: Gender and Academic Career at Swedish Universities.” Gender and Education 32 (3): 347–62. doi:10.1080/09540253.2017.1401047.

- Arokiasamy, L., M. Ismail, A. Ahmad, and J. Othman. 2011. “Predictors of Academics’ Career Advancement at Malaysian Private Universities.” Journal of European Industrial Training 35 (6): 589–605. doi:10.1108/03090591111150112.

- Auster, E. R., and A. Prasad. 2016. “Why Do Women Still Not Make It to the Top? Dominant Organizational Ideologies and Biases by Promotion Committees Limit Opportunities to Destination Positions.” Sex Roles 75 (5): 177–96. doi:10.1007/s11199-016-0607-0.

- Baker, V. L., L. D. Gonzales, and A. L. Terosky. 2020. “Faculty-Inspired Strategies for Early Career Success Across Institutional Types: The Role of Mentoring.” In The Wiley International Handbook of Mentoring: Paradigms, Practices, Programs, and Possibilities, edited by B. J. Irby, 223–241. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

- Batistič, S., and R. Kaše. 2015. “The Organizational Socialization Field Fragmentation: A Bibliometric Review.” Scientometrics 104 (1): 121–46. doi:10.1007/s11192-015-1538-1.

- Beigi, M., M. Shirmohammadi, and M. Arthur. 2018. “Intelligent Career Success: The Case of Distinguished Academics.” Journal of Vocational Behavior 107: 261–75. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2018.05.007.

- Blackstone, A., and S. K. Gardner. 2017. “Faculty Agency in Applying for Promotion to Professor.” Journal for the Study of Postsecondary and Tertiary Education 2: 59. doi:10.28945/3664.

- Brew, A., D. Boud, K. Crawford, and L. Lucas. 2017. “Navigating the Demands of Academic Work to Shape an Academic job.” Studies in Higher Education 43 (12): 2294–304. doi:10.1080/03075079.2017.1326023.

- Campbell, C. M., and K. O’Meara. 2014. “Faculty Agency: Departmental Contexts That Matter in Faculty Careers.” Research in Higher Education 55 (1): 49–74. doi:10.1007/s11162-013-9303-x.

- Caplow, T., and R. J. McGee. 1958. The Academic Marketplace. New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers.

- Cooper, O. 2019. “Where and What are the Barriers to Progression for Female Students and Academics in UK Higher Education?” Perspectives: Policy and Practice in Higher Education 23 (2-3): 93–100. doi:10.1080/13603108.2018.1544176.

- Dany, F., S. Louvel, and A. Valette. 2011. “Academic Careers: The Limits of the ‘Boundaryless Approach’ and the Power of Promotion Scripts.” Human Relations 64 (7): 971–96. doi:10.1177/0018726710393537.

- Department of Education and Training (DET). 2020. Higher education statistics: Selected higher education statistics – 2020 staff data. https://www.dese.gov.au/higher-education-statistics/staff-data/selected-higher-education-statistics-2020-staff-data.

- Dobele, A. R., and S. Rundle-Theile. 2015. “Progression Through Academic Ranks: A Longitudinal Examination of Internal Promotion Drivers.” Higher Education Quarterly 69 (4): 410–29. doi:10.1111/hequ.12081.

- Durodoye, R., M. Gumpertz, A. Wilson, E. Griffith, and S. Ahmad. 2020. “Tenure and Promotion Outcomes at Four Large Land Grant Universities: Examining the Role of Gender, Race, and Academic Discipline.” Research in Higher Education 61 (5): 628–51. doi:10.1007/s11162-019-09573-9.

- Enders, J., and C. Musselin. 2008. Back to the Future? The Academic Professions in the 21st Century. Higher Education to, 2030, 125–150.

- Finkelstein, M. 2015. “How National Contexts Shape Academic Careers: A Preliminary Analysis.” In Forming, Recruiting and Managing the Academic Profession (Vol. 14), edited by U. Teichler, and W. K. Cummings, 317–28. New York: Springer International Publishing.

- Flowers, L. R. 2006. Exploration of Socialization Process of Female Leaders in Counselor Education. Doctoral dissertation: University of New Orleans.

- Francis, L., and V. Stulz. 2020. “Barriers and Facilitators for Women Academics Seeking Promotion: Perspectives from the Inside.” The Australian Universities’ Review 62 (2): 47–60.

- Gioia, D. A., K. G. Corley, and A. L. Hamilton. 2013. “Seeking Qualitative Rigor in Inductive Research: Notes on the Gioia Methodology.” Organizational Research Methods 16 (1): 15–31. doi:10.1177/1094428112452151.

- Greenhaus, J. H., G. A. Callanan, and V. M. Godshalk. 2018. Career Management for Life. Milton: Taylor & Francis Group.

- Hakiem, R. A. D. 2022. “Advancement and Subordination of Women Academics in Saudi Arabia’s Higher Education.” Higher Education Research & Development 41 (5): 1528–41. doi:10.1080/07294360.2021.1933394.

- Heffernan, T. 2021. “Academic Networks and Career Trajectory: ‘There’s no Career in Academia Without Networks’.” Higher Education Research & Development 40 (5): 981–94. doi:10.1080/07294360.2020.1799948.

- Howe-Walsh, L., and S. Turnbull. 2016. “Barriers to Women Leaders in Academia: Tales from Science and Technology.” Studies in Higher Education, 1–14. doi:10.1080/03075079.2014.929102.

- Jones, C., and R. J. DeFillippi. 1996. “Back to the Future in Film: Combining Industry and Self-Knowledge to Meet the Career Challenges of the 21st Century.” The Academy of Management Executive (1993) 10 (4): 89–103. doi:10.5465/AME.1996.3145322.

- Kenny, J. 2017. “Academic Work and Performativity.” Higher Education 74 (5): 897–913. doi:10.1007/s10734-016-0084-y.

- Kowtha, N. R. 2018. “Organizational Socialization of Newcomers: The Role of Professional Socialization.” International Journal of Training and Development 22 (2): 87–106. doi:10.1111/ijtd.12120.

- Kuvaeva, A. A. 2019. Women faculty agency: A case study of two universities in Russia [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. University of Maryland, College Park, Ann Arbor. ProQuest dissertations & theses A&I database. (13902929).

- Larkin, J. 2016. “Fading@ 50?”: A study of career management for older academics in Australia.

- Larsen, E., and R. Brandenburg. 2022. “Navigating the neo-Academy: Experiences of Liminality and Identity Construction among Early Career Researchers at one Australian Regional University.” The Australian Educational Researcher, doi:10.1007/s13384-022-00544-1.

- Leathwood, C., and B. Read. 2022. “Short-term, Short-Changed? A Temporal Perspective on the Implications of Academic Casualisation for Teaching in Higher Education.” Teaching in Higher Education 27 (6): 756–71. doi:10.1080/13562517.2020.1742681.

- Mahat, M., and J. Tatebe. 2019. “Demystifying the Academic Promotion Process.” In Achieving Academic Promotion, edited by M. Mahat, and J. Tatebe, 3–27. Bingley: Emerald Publishing Limited.

- Merriam, S. B., and E. J. Tisdell. 2015. Qualitative Research: A Guide to Design and Implementation. Newark: John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated.

- Neumann, A. 2009. Professing to Learn: Creating Tenured Lives and Careers in the American Research University. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- O'Meara, K. 2015. “A Career with a View: Agentic Perspectives of Women Faculty.” The Journal of Higher Education 86 (3): 331–59. doi:10.1080/00221546.2015.11777367.

- O'Meara, K., and N. P. Stromquist. 2015. “Faculty Peer Networks: Role and Relevance in Advancing Agency and Gender Equity.” Gender and Education 27 (3): 338–58. doi:10.1080/09540253.2015.1027668.

- O'Meara, K., A. L. Terosky, and A. Neumann. 2008. “Faculty Careers and Work Lives: A Professional Growth Perspective.” ASHE Higher Education Report 34 (3): 1–221. doi:10.1002/aehe.3403.

- Patton, M. Q. 2002. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, Calif.: Sage Publications.

- Roberts, L. W., and D. M. Hilty. 2017. Handbook of Career Development in Academic Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences. 2nd ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association Publishing.

- Staniland, N. A., C. Harris, and J. K. Pringle. 2020. “‘Fit’ for Whom? Career Strategies of Indigenous (Māori) Academics.” Higher Education 79 (4): 589–604. doi:10.1007/s10734-019-00425-0.

- Sutherland, K. A. 2017. “Constructions of Success in Academia: An Early Career Perspective.” Studies in Higher Education 42 (4): 743–59. doi:10.1080/03075079.2015.1072150.

- Templeton, L., and K. O'meara. 2018. “Enhancing Agency Through Leadership Development Programs for Faculty.” The Journal of Faculty Development 32 (1): 31–6.

- Terosky, A. L., and K. O'Meara. 2011. “The Power of Strategy and Networks in the Professional Lives of Faculty.” Liberal Education 97 (3/4): 54–9.

- Wanberg, C. R., and J. D. Kammeyer-Mueller. 2000. “Predictors and Outcomes of Proactivity in the Socialization Process.” Journal of Applied Psychology 85 (3): 373–85. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.85.3.373.

- Whitchurch, C., W. Locke, and G. Marini. 2021. “Challenging Career Models in Higher Education: The Influence of Internal Career Scripts and the Rise of the “Concertina” Career.” Higher Education 82 (3): 635–50. doi:10.1007/s10734-021-00724-5.

- Whitchurch, C., W. Locke, and G. Marini. 2023. Challenging Approaches to Academic Career-Making. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Zacher, H., C. W. Rudolph, T. Todorovic, and D. Ammann. 2019. “Academic Career Development: A Review and Research Agenda.” Journal of Vocational Behavior 110: 357–73. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2018.08.006.