?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

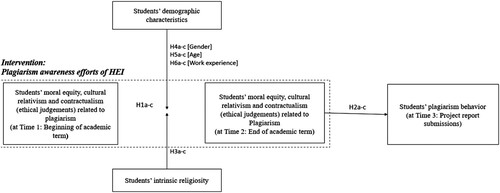

Widespread academic dishonesty among higher education (HE) students has been a concern for higher education institutes (HEIs). Ethics literature reports that unintentional plagiarism is more prevalent among HE students and the root cause is, limited or no awareness of nuances of ethics concerning plagiarism resulting in poor ethical judgments. This study attempts to examine what is students’ ethical reasoning for unintentional plagiarism and how HEIs’ ethical awareness efforts impact students’ ethical judgments which ultimately shape their ethical behavior. The study also explored whether and how individual-level factors such as intrinsic religiosity, age, gender, and work experience moderate the focal relationships. A longitudinal quasi-experimental field study was conducted. The subjects of the study were 294 postgraduate students of an internationally accredited higher education institution in India. The pretest–posttest design involved a set of experimental manipulations reflecting the HEI's endeavors to explicate the unethical implications of plagiarism.

1. Introduction

The increasingly frequent incidents of unethical behavior in the global corporate world have shown a spotlight on the role of higher education institutes (HEIs) in promoting ethical behavior among future corporate employees (Blau and Eshet-Alkalai Citation2017; Gottardello and Pàmies Citation2019; Gullifer and Tyson Citation2014). Widespread academic dishonesty among higher education (HE) students who are future employees and entrepreneurs is certainly a concern for HEIs (Abbas et al. Citation2021; Bernardi and Higgins Citation2020). Dishonest behavior of students in academic settings can manifest itself as unethical behavior at the workplace such as; payment of bribes, misrepresentation of facts, breach of confidentiality, etc. (Holland and Albrecht Citation2013). In fact, there is empirical evidence that students who exhibit dishonesty in academic settings are more likely to behave unethically at their workplace as well (Rupp et al. Citation2015; Tzini and Jain Citation2018).

Despite profound scholarly discussions, there is no consensus about the definition of academic dishonesty that explains the types of behaviors constituting types of dishonesty (Jamieson and Howard Citation2019) and duly considers all stakeholders’ concerns (Aluede, Omoregie, and Osa-Edoh Citation2006). Lacking a precise definition and agreement on behaviors describing academic dishonesty, various terms are used interchangeably such as ‘cheating,’ ‘dishonesty,’ and ‘academic immorality’ (Burrus, McGoldrick, and Schuhmann Citation2007; Lee, Kuncel, and Gau Citation2020). Previous studies have suggested that one of the most prominent and reported forms of academic dishonesty prevailing in the students’ community is plagiarism (Radulovic and Uys Citation2019; Şendağ, Duran, and Fraser Citation2012). According to Gotterbarn, Miller, and Impagliazzo (Citation2006) Plagiarism refers to the ‘inappropriate, unauthorized, unacknowledged use of someone else’s ideas as if they were original or common knowledge [including] … incomplete or vague references that tend to mislead the reader into misidentifying one person’s ideas for another.’ In simple words, plagiarism is an act of unauthorized use of someone else's work without due attribution (Devlin and Gray Citation2007). It covers copying and careless paraphrasing of others’ work (Honig and Bedi Citation2012). Several previous studies have found that due to a lack of awareness about ethical concerns related to plagiarism, HE students do not perceive plagiarism as a serious ethical misdemeanour (Abbas et al. Citation2021; East Citation2010; Khathayut, Walker-Gleaves, and Humble Citation2022). Moreover, students and academic staff can have different views on the unethicality associated with plagiarism (Evans Citation2006).

However, it is important to note here that the plagiarism continuum ranges from unintentional to intentional plagiarism (Fatemi and Saito Citation2020; Sutherland-Smith Citation2005). Intentional plagiarism is an act of deliberate ignorance of plagiarism policy and rules, whereas unintentional plagiarism results from a student’s lack of understanding or different understanding of the nuances of ethics surrounding plagiarism (Anson Citation2011; Fatemi and Saito Citation2020; Gullifer and Tyson Citation2010). Ethics research has frequently reported that unintentional plagiarism is more prevalent among HE students and the root cause is, limited or no awareness of nuances of academic ethics concerning plagiarism which results in poor ethical judgments (Farahian, Avarzamani, and Rezaee Citation2022; Ruedy and Schweitzer Citation2010). Ethical judgment which is an individual’s evaluation of the ethicality of action in a given situation is found to be a strong predictor of ethical behavior (Otaye-Ebede, Shaffakat, and Foster Citation2020). These interacting issues highlight HEIs’ responsibility to sensitize and educate students about ethical issues concerning plagiarism.

Ethics research argues that HEIs should arm their students with a deeper understanding of plagiarism ethics which is beyond just a pragmatic view of why plagiarism is unacceptable. Plagiarism education and awareness exercises can significantly improve students’ ethical sensitivity and critical-thinking approach to ethical decision-making. Their ability to make strong ethical judgments in academic settings is expected to lead to ethical behavior in professional settings too (Chang et al. Citation2019; Sulaiman et al. Citation2022; Youmans Citation2011). Dedicated efforts are required at HEIs’ level to create awareness among students about plagiarism ethics because unlike other acts of academic dishonesty such as cheating, plagiarism is not defined for new HE students. Although many HEIs have started disseminating information among students to define plagiarism and explain its unethicality through handbooks, regulations, awareness exercises, code of ethics, and plagiarism ethics policies, etc., these efforts have not been able to contribute much. Preventive measures such as software to detect plagiarism and punitive measures have failed to discourage students from plagiarizing (Nwosu and Chukwuere Citation2020). This is primarily because preventive measures may deter dishonest actions in certain situations but cannot bring a behavioral change (Davis et al. Citation1992). Therefore, it becomes important for HEIs to direct plagiarism awareness efforts toward students’ moral development instead of treating plagiarism merely as a penal action (Ryan et al. Citation2009). This is how they can encourage students to embrace ethical behavior not only in academic settings but also in the workplace.

Considering lack of awareness to be the primary reason for poor ethical judgment concerning academic ethics in general and plagiarism in particular, and its impact on students’ ethical behavior, there are a few interacting questions for HEIs and educators. Important among these are what is students’ ethical reasoning of the acts of academic dishonesty such as; plagiarism and how HEIs’ ethical awareness efforts impact students’ ethical judgments which in turn promote ethical behavior. Additionally, HEIs should consider the findings of previous ethics research suggesting that an individual's personal and demographic characteristics such as intrinsic religiosity, age, gender, work experience, etc. are strongly linked with ethical judgments and are instrumental in predicting the ethical conduct of a person in a given situation (Alshehri, Fotaki, and Kauser Citation2021; Bateman and Valentine Citation2010; Januarti Citation2011). Therefore, it will be useful to explore whether and how individual-level factors such as intrinsic religiosity, age, gender, etc. moderate the impact of HEIs’ plagiarism awareness efforts on students’ ethical judgments and ultimately their ethical behavior.

This study attempts to answer these questions empirically by conducting a longitudinal quasi-experimental field study (Campbell Citation1963; Cook and Campbell Citation1979). This research design is apt for empirical validation of the causal effects of real-world interventions on the potential attitudinal and behavioral outcomes (Deaton and Cartwright Citation2018). Data for the field study was collected from a sample of 297 postgraduate students of an internationally accredited HEI in India. The experiment data were analyzed using multivariate statistical methods (Hair et al. Citation2010). The remaining sections of this paper are organized as follows. In the next section, we explain the theoretical background of this study, followed by a literature review and hypotheses development. The fourth section outlines the methods and results are provided in the fifth section. Discussion and implications are explained in the sixth section, followed by the conclusion and limitations of this study in the last section.

2. Theoretical framework

Given that HEIs consider plagiarism an issue of academic ethics and are inclined to develop effective plagiarism awareness exercises for HE students, more knowledge about students’ ethical reasoning for plagiarism could be insightful. To understand the interaction of students’ ethical reasoning for plagiarism and the responsibility of institutes/universities to promote ethical behavior, we referred to previous studies on students’ academic dishonesty, ethical theories, and theoretical models explaining the cognitive process of ethical behavior. The following sub-sections summarize our review of relevant theories.

2.1. Students’ ethical reasoning of plagiarism – the perspective of ethical theories

Intentional Plagiarism (IP) demonstrates unethical academic behavior as it transgresses core academic values namely, fairness, honesty, and trust in which the plagiarist student fraudulently uses the original author’s intellectual property (Hansen et al. Citation2011; Keohane Citation1999). Ownership of intellectual ideas is at the core of academic pursuits and intellectual theft erodes the moral values of academic honesty (Gullifer and Tyson Citation2010; Perfect and Stark Citation2012). IP by students is attributed to violating the academic ethics policy of the university, ignorance of referencing rules, and authorship acknowledgements, and to procrastination leading to expediency and cheating to secure better grades (Anson Citation2011; Khathayut, Walker-Gleaves, and Humble Citation2022). Plagiarist students earn personal gains over the good of other students and the integrity of the academic institution and therefore, it is a form of immoral behavior (Staats et al. Citation2009). While there is a consensus about IP being unethical behavior, a group of scholars feels that unintentional plagiarism (UIP) may not be considered unethical behavior and it should not be dealt with rigorous punishment/penalty (Jamieson Citation2016). UIP can be prevented by the institutions/universities by making efforts to create plagiarism ethical awareness among the students.

An in-depth review of several studies on academic ethics revealed some types of reasoning used by students in different ethical contexts. Students quite often use some ethical philosophies to justify the act of IP (Granitz and Loewy Citation2007). For example, students may use utilitarian philosophies to argue that IP leads to better outcomes in terms of greater learning and higher grades without harming anyone and thus creating the greatest total utility (De George Citation1990). Previous studies have reported another ethical context to justify IP which is inspired by the rational self-interest perspective of ethics (Ashworth, Bannister, and Thorne Citation1997; Waltzer and Dahl Citation2021). Where plagiarist students believe that plagiarism is not unethical because they are engaged in a fair exchange of value. For example, they may feel that by using others’ work they are helping the author publicize his/her work. Similarly, research indicates that plagiarists embrace Machiavellianism ethical context to defend IP where the students are primarily motivated to act in their self-interest (Granitz and Loewy Citation2007). The student may experience a thrill when he/she gets by without catching the professor’s attention to his/her plagiarized act (Webster and Harmon Citation2002).

The subscribers of deontology extend the continuum of ethics to personal values, i.e. what a person feels is right (De George Citation1990). The locus of right and wrong is self-directed and therefore, a student who follows a deontological perspective of ethics can only plagiarize when he/she lacks a clear understanding of what type of activities are covered under plagiarism (Bugeja Citation2001). In the same vein, a student may derive the meaning of right, wrong, fair, unfair, justice, and injustice from his/her cultural attributes (Donaldson Citation1989). Since all cultures do not follow the same ethical standards, ethical judgment about an action may vary across cultures (Granitz and Loewy Citation2007; Hayes and Introna Citation2005). Therefore, it is not unlikely that students’ perception of a plagiarism activity differs based on their cultural background. Some of them may not consider plagiarism activity as an unethical action because it is acceptable in their culture while others from a different cultural background may feel just the opposite. Demonstrating a relativist approach, previous studies have found that cultural background is an important determinant of students’ ethical behavior (Hay Citation2002). It should be noted that students who apply deontology or cultural relativism in making ethical judgments may not be necessarily aware of the transgression. They may not even realize that they are indulging in an unethical act. However, students subscribing to utilitarianism self-interest, or Machiavellianism are fully aware of their wrongdoings.

2.2. Students’ ethical reasoning of plagiarism – cognitive moral development theory perspective

To understand students’ ethical reasoning for plagiarism, we referred to the cognitive moral development theory proposed by Kohlberg (Citation1969). A vast majority of studies on ethical behavior and ethical decision-making have based their work on this theory to understand what can be done to promote ethical behavior (Cahyono and Sudaryati Citation2023; Jordan et al. Citation2013; Latif Citation2000). The theory defines a person’s ethical reasoning as ‘an ability to interpret the situation and analyze consequences of possible actions to himself/herself and others; judge a morally right course of action; give precedence to morally right consideration over others, and follow the intention to act morally’ (Trevino Citation1992, 445). In the ethics literature, the terms ‘ethics;’ and ‘moral’ are intractably used (Treviño, Weaver, and Reynolds Citation2006). Thus, according to this theory, students’ ethical reasoning for plagiarism will comprise three broad concepts: ethical awareness, ethical judgment, and ethical behavior (intention and action). Ethical awareness is embedded in interpreting the ethical dilemma; ethical judgment is rooted in analyzing available courses of action and their consequences and identifying what is ethically right, and ethical intention and action are implied in giving priority to ethical action over the other considerations and doing what is ethically right (Nwosu and Chukwuere Citation2020). It is implied in the theory that the cognitive moral development of a student for plagiarism ethics will be significantly affected by his/her ability to interpret the ethical dilemma, i.e. ethical awareness because ethical judgment is guided by the correct interpretation of the situation which in turn will affect ethical behavior (Treviño, Weaver, and Reynolds Citation2006).

In this study, we aim to study students’ ethical reasoning for plagiarism and HEIs’ role in shaping students’ ethical behavior in academic settings. To attain this objective, we examined the impact of HEIs’ plagiarism ethics awareness efforts on students’ ethical judgment which in turn is expected to influence ethical behavior. For measuring students’ ethical judgment, we referred to Multidimensional Ethics Scale (MES) proposed by Reidenbach and Robin (Citation1990) which is the most recommended and widely used instrument (Pelegrín-Borondo et al. Citation2020). This scale views ethical judgment as a multidimensional construct such that ethicality is a function of three broad-based philosophies: moral equity, relativism, and contractualism. Moral equity which is the most complicated dimension captures how a person perceives fairness and justice. Right and wrong are measured on an individual’s principles of fairness and moral propriety (LaFleur et al. Citation1995). The relativism dimension concentrates on social/cultural requirements, guidelines, and norms than individual considerations. Right, and wrong is guided by norms and principles inherent in the social/cultural system than individuals’ viewpoints. The third dimension, contractualism captures normative philosophies in terms of an individual's perception of right or wrong based on an implied contract between him/her and society. The ethicality of action is based on the notion of violation/non-violation of implicit duties, rules, and promises made with society (Reidenbach and Robin Citation1990).

In the following sections, we propose the hypotheses after reviewing the literature on the impact of ethical awareness efforts on ethical judgment and how improved ethical judgment affects ethical behavior.

3. Literature review and hypothesis

3.1. Ethical awareness efforts and ethical judgment related to plagiarism

Achieving academic integration is a complex challenge faced by the majority of HE students. To be successful, students have to meet the explicit academic standards (structural academic integration) in a way that is deemed acceptable by the institution (normative academic integration) (Braxton and Lee Citation2005; Schaeper Citation2020). Attaining academic integration may be particularly difficult if students lack enough knowledge about normative academic standards (Coll and Stewart Citation2008). The problem is compounded when there is a fundamental disjuncture between the ethical views of students and academic staff, or students’ understanding of what comprises AI is different from that of the professors. This situation indicates a lack of ethical awareness among the students which may result in poor ethical judgments (Ayton et al. Citation2022).

Ethical awareness refers to a person’s belief that there exists an ethical problem in a given situation (Singhapakdi et al. Citation1996). While measuring this construct, a person is asked to report if he/she believes a problem stated in a given case raises ethical concerns. Recognition of ethical issues leads to cautious consideration of their ethicality and consequences for self and others which results in fair ethical judgments (Barnett and Valentine Citation2004). Empirical studies have found that due to a lack of plagiarism ethical awareness, students faced difficulty in understanding the nuances of plagiarism (Abbas et al. Citation2021; Breen and Maassen Citation2005). A poor understanding of plagiarism ethics adversely affects students’ ethical judgments leading to unethical behavior. For instance, Breen and Maassen (Citation2005) found that despite having a clear appreciation that quoting direct words from a source was an academic offence, students struggled with paraphrasing and idea citations.

Given the role of ethical awareness in facilitating ethical judgments, institutions/universities can play an active role in creating plagiarism ethical awareness among students. Extant literature suggests that ethical awareness efforts in the form of library instructions, antiplagiarism policy, honor codes, and integrating lecture sessions on plagiarism ethics have significantly improved students’ ethical judgment (Belter and Du Pre Citation2009). Awareness of the unethical implications of plagiarism helps the students analyze the alternative options and identify the ethically correct course of action. Supporting these claims, several empirical studies have reported that ethical awareness is positively related to ethical judgments (Abbas et al. Citation2021; Latan, Chiappetta Jabbour, and Lopes de Sousa Jabbour Citation2019; Pan and Sparks Citation2012). Literature on academic ethics makes us believe that plagiarism ethics awareness efforts will improve students’ ethical judgments related to plagiarism and we propose;

H1a–c: Plagiarism awareness efforts positively influence students’ ethical judgment (H1a-moral equity, H1b-relativism, H1c-contractualism) related to plagiarism.

3.2. Ethical judgment and plagiarism behavior

Ethical judgment refers to an individual’s belief that an action is morally acceptable (Gifford Citation2007). The values and principles making the code of ethics direct an individual's way of forming judgments concerning what is ethically right or wrong (Aaker Citation1989). And therefore, individuals possessing high ethical values are likely to be more sensitive toward the ethicality of an issue (ethical awareness) and they are assumed to form better ethical judgments (Abdullah, Sulong, and Said Citation2014). We refer to social cognitive theory (Bandura Citation1989) to understand the impact of ethical judgment on ethical behavior. The theory suggests a human agency model that explains how internal and external parameters influence an individual's ability to engage in a targeted behavior (Martin et al. Citation2014). This theory proposes that an individual’s moral judgments guide their moral conduct (Otaye-Ebede, Shaffakat, and Foster Citation2020; Wood and Bandura Citation1989). Drawing from this theory we believe that students’ ethical judgments will form the basis for their ethical behavior.

It is important to mention here that cognitive moral development theory suggests that ethical judgments lead to ethical intention which influences ethical actions. In the same vein, the theory of reasoned action also proposes that an individual’s behavioral intention to act is the predictor of his/her behavioral action (Ajzen and Fishbein Citation1975). However, some previous ethical behavior studies have reported a disconnect between behavioral intention and ethical behavior (Moon, Habib, and Attiq Citation2015). It indicates that students might report a strong intention to act ethically but they may not subsequently act following their level of intention to act. Therefore, we decided to record behavioral action instead of behavioral intention, which is considered a stronger indicator of ethical behavior. Numerous previous studies have included ethical judgment as a key indicator of ethical behavior (Chang et al. Citation2019; Otaye-Ebede, Shaffakat, and Foster Citation2020). Therefore, efforts should be made to improve students’ ethical judgment related to plagiarism.

Earlier studies suggest that through ethical awareness efforts such as the use of case studies presenting plagiarism ethical dilemmas, and awareness lecture sessions, student’s ability to make ethical judgments can be improved (Elbe and Brand Citation2016; Kim and Park Citation2019). Learning from the ethical judgments will help the students develop a degree of automaticity in their ethical decision making resulting in consistency between ethical judgments and ethical behavior (Halder et al. Citation2020). Automaticity in the present context refers to the ease with which students make ethical decisions and act accordingly without conscious reasoning or much mental struggle (Lapsley and Narvaez Citation2004). Thus, the more the ability to make ethical judgments, the higher the likelihood of demonstrating ethical behavior (Otaye-Ebede, Shaffakat, and Foster Citation2020). In light of the scholarly arguments supporting a relationship between ethical judgments and ethical behavior, we propose to test the following hypothesis:

H2a–c: Students’ ethical judgment related to plagiarism (H2a-moral equity, H2b-relativism, H2c-contractualism) positively influences their ethical behavior.

3.3. Moderating role of intrinsic religiosity

Religiosity has been consistently reported to influence ethical outcomes because individuals’ behaviors are primarily guided by the values, principles, and moral duties embedded in their sociocultural and religious beliefs (Arli, Tkaczynski, and Anandya Citation2019). To uncover the role of religiosity in ethical decision making we refer to the Hunt-Vitell model (Citation1986) which explains three ways in which religiosity influences ethical judgments. First, an individual’s deontological norms (personal values and principles) are a function of religious beliefs, and his/her deontological evaluation (ethical judgment) may vary from person to person. Second, in the ethical decision-making process, the relationship between deontological and teleological norms is impacted by the relative importance of individual perspective, and therefore, more religious individuals may give higher importance to deontological norms while making ethical judgments (Hunt and Vitell Citation2006). Third, religiosity may restrict some potential alternative actions if they are not aligned with religious beliefs (Hansen et al. Citation2011).

An Individual’s religious orientation can be broadly classified into two categories: extrinsic and intrinsic religiosity. Extrinsic religiosity captures an individual’s religious motivation for personal gains while intrinsic religiosity relates to an individual’s motivation driven by core values and principles of the religion (Allport and Ross Citation1967). The scope of this study is to examine the moderating impact of intrinsic religiosity which has clear ethical implications (Vitell, Paolillo, and Singh Citation2005). On the other hand, extrinsic religiosity is found to be either unrelated or negatively related to ethical behaviors (Walker, Smither, and DeBode Citation2012). Intrinsic religiosity is described as the degree to which religion is integrated into the follower’s life (Pargament Citation2002). It is important to note the difference between religion and religiosity because it is religiosity that drives individuals’ ethical behavior and not religion. A person may claim to believe in a religion, but he/she may not be religious unless the values of that religion are practised (Parboteeah, Paik, and Cullen Citation2009) and belief in a religion and religiosity are not the same because belief without practice is immaterial. In this study religiosity of an individual is a measure of how religious he/she is (Hoge Citation1972).

The literature argues that individuals’ actions/behaviors are motivated or restricted by their religious beliefs i.e. religiosity (McAndrew and Voas Citation2011). In the ethical behavior contexts, previous studies have extensively examined the impact of religiosity on an individual’s behavior (Bhuian et al. Citation2018), and generally, intrinsic religiosity is reported to motivate ethical judgments and pro-social behaviors (e.g. Paxton, Reith, and Glanville Citation2014). Despite some disagreements on the relationship between religiosity and ethical judgment, a majority of the studies have found a significant positive relationship between the two (Alshehri, Fotaki, and Kauser Citation2021; McAndrew and Voas Citation2011; Walker, Smither, and DeBode Citation2012). Individuals who consciously follow the doctrine of their religion are more sensitive toward ethical issues and therefore can easily identify ethical challenges in a given scenario leading to fair ethical judgment (Putrevu and Swimberghek Citation2013). Empirical studies have supported this argument by recording individuals with high or moderate religiosity making stronger ethical judgments than the ones with lower religiosity scores (Choe and Lau Citation2010; Walker, Smither, and DeBode Citation2012). Given the role of religiosity in ethical decision-making, we believe that religiosity could influence the impact of plagiarism ethics awareness efforts on students’ ethical judgments.

H3a–c: Intrinsic religiosity moderates the impact of plagiarism awareness efforts on students’ ethical judgment (H3a-moral equity, H3b-relativism, H3c-contractualism) related to plagiarism.

3.4. Demographic characteristics and ethical judgment related to plagiarism

The extant literature suggests that personal demographic characteristics are linked with ethical judgments made by individuals in various ethical contexts. In the context of academic ethics, numerous studies have found that demographic factors such as age, gender (Bateman and Valentine Citation2010; Eweje and Brunton Citation2010), and work experience (Eweje and Brunton Citation2010; Januarti Citation2011) are associated with ethical judgments leading to ethical/ moral behavior. In the following section, we discuss the potential moderating effect of demographic factors on the relationship between plagiarism awareness efforts and students’ ethical judgments related to plagiarism ethics.

3.4.1. Gender

A rich body of literature exists on gender differences between ethical judgments made by men and women (e.g. Howell, Roberts, and Mancin Citation2018; Pan and Sparks Citation2012; Roxas and Stoneback Citation2004). There are two main explanations provided in the literature. One explanation is based on biological determinism which suggests that individuals are biologically predisposed to act/behave in a certain manner and this predisposition makes men and women behave more ethically or less ethically in each situation (Miller and Costello Citation2001). In simple words, this view suggests that a person’s ethical judgment and consequent behavior are embedded in his/her biological roots and thus they are born with specific ethical or unethical tendencies which shape their ethical judgments (Udry Citation2001). While this viewpoint is found to be weak and unconvincing by the majority of ethics scholars, the other explanation based on early socialization processes adopted by males and females has been able to convince a larger community of ethics scholars. This viewpoint proposes that men’s early socialization emphasizing ambition and competition determines their ethical judgments while women’s socialization stressing care, harmony and warmth guides their ethical judgments (Roxas and Stoneback Citation2004). The scant literature on socialization and behavior has consistently maintained that socialization plays a key role in shaping individuals’ ethical judgments. Although there is a large body of literature suggests that women make stricter ethical judgments as they apply more rigid and firm ethical standards than their counterparts (Howell, Roberts, and Mancin Citation2018; Marques and Azevedo-Pereira Citation2009; Pan and Sparks Citation2012), there are a group of studies that claimed that this argument lacks sufficient empirical evidence (Klein and Shtudiner Citation2021; Taylor and Curtis Citation2010). Irrespective of varying explanations for gender differences in ethical judgment and lack of consensus on the directions of gender differences in ethical judgment, the literature guides us for the following hypothesis:

H4a–c: Gender will moderate the relationship between plagiarism awareness efforts and students’ ethical judgment (H4a-moral equity, H4b-relativism, H4c-contractualism) related to plagiarism.

3.4.2. Age

Individuals’ viewpoints and evaluations are shaped by their age and maturity. Research on ethical judgments has also corroborated this argument by providing evidence showing an increase in ethicality with age (Valentine and Godkin Citation2019). Several studies have reported that younger respondents act less ethically than older ones (Chiu Citation2003), and the explanations for this finding suggest that adults go through different phases of moral development as they grow old (Kohlberg and Candee Citation1984). Several empirical findings have supported these claims (Chen et al. Citation2022; Eweje and Brunton Citation2010; White and Lam Citation2000). For example, Chen et al. (Citation2022) found in their studies that younger respondents were more engaged in unethical and illicit activities than older ones. While a majority of the studies have found a positive relationship between age and ethical judgments, a few have reported no or insignificant relationship between the two. These studies argue that age difference does not explain individuals’ moral development and ethical judgments, rather other factors such as, family-systems are better determinants of ethical decision-making (White and Lam Citation2000). Similar to gender, there is no consensus about the impact of age on ethical evaluations, however, theoretical consensus suggests that moral development progresses with age which leads to better ethical judgments.

H5a–c: Age will moderate the relationship between plagiarism awareness efforts and students’ ethical judgment (H5a-moral equity, H5b-relativism, H5c-contractualism) related to plagiarism.

3.4.3. Work experience

Experience helps individuals gain knowledge which helps them to develop the ability to interpret and integrate evidence and apply mental models while making judgments. Previous studies have found that experienced people are seen to be more strictly and effectively dealing with ethical dilemmas (Latan, Chiappetta Jabbour, and Lopes de Sousa Jabbour Citation2019; Marques and Azevedo-Pereira Citation2009; Pan and Sparks Citation2012). The literature explains this relationship based on workplace socialization. Individuals follow workplace norms during workplace and benchmark their ethical standards against the organization’s high standards for ethical judgments (Hunt and Vitell Citation1986; Valentine, Hanson, and Fleischman Citation2019). Thus, the more time spent at work greater the impact of high ethical standards followed at the workplace leading to strict ethical judgments (Hunt and Vitell Citation1993). Several studies have contributed empirical evidence supporting the positive impact of work experience on ethical judgments (Eweje and Brunton Citation2010; Pan and Sparks Citation2012; Sivaraman Citation2019). Grounded on these arguments, we believe that students with work experience are likely to apply the memory structures and knowledge developed during the work while exposed to plagiarism ethics awareness efforts made by the institution/university. Thus, they are expected to better respond to ethics awareness efforts which will affect their ethical judgments.

H6a-c: Work experience will moderate the relationship between plagiarism awareness efforts and students’ ethical judgment (H6a-moral equity, H6b-relativism, H6c-contractualism) related to plagiarism.

4. Methods

To test the conceptual model (), a longitudinal quasi-experimental field study was conducted. Unlike true experiments based on randomized trials, quasi-experimental designs involve the use of nonexperimental manipulations in the independent variable under study, essentially by imitating experimental treatments/conditions wherein participants are non-randomly assigned to the treatments (Campbell and Stanley Citation1966; Cook and Campbell Citation1979). The quasi-experimental design employed for this study was a pretest-posttest design (with no control group) which involves the use of a pretest and posttest of participants to establish a causal association between an intervention and an outcome (Cook and Campbell Citation1979; Shadish, Cook, and Campbell Citation2002). This between-subjects experimentation design is widely employed in medical, education, psychology, and social science research fields to evaluate the implications of the design and implementation of interventions (Tipton and Olsen Citation2018). The research design is considered apt for this study, first, it enabled to have a high degree of external validity for evaluating the real-world effectiveness of interventions (Deaton and Cartwright Citation2018) i.e. plagiarism awareness efforts in this study; second, it is suitable for conducting experiments as part of field studies, where randomized controlled trials are deemed unattainable or unethical (Shadish, Cook, and Campbell Citation2002).

4.1. Study context and subjects

India as a country offers one of the largest HE setups in the world with more than 350 government universities (both central and state government-owned), 129 deemed universities and more than 180 private universities (Singh Citation2016). Like other countries, plagiarism cases are rapidly rising in Indian HEIs, involving HE students, research scholars and also faculty members. The main reasons for the rise in plagiarism cases are a lack of knowledge on plagiarism and academic ethics, clear policies to deal with plagiarism cases and policy guidelines for academic writing (Juyal, Thawani, and Thaledi Citation2015). Taking note of the gravity of the problem, the Government of India recently notified regulations for all Indian universities and HEIs on ‘Promotion of Academic Integrity and Prevention of Plagiarism in Higher Educational Institutions.’ These regulations define plagiarism and provide guidelines for academic integrity. The regulations were enforced through University Grant Commission (UGC), the main statutory body regulating the activities of Indian universities (Kadam Citation2018). Additionally, INFLIBNET Centre on Shodhganga (repository of e-theses of Indian universities) offers two plagiarism-detection software: ‘iThenticate’ and ‘Turnitin’ to Indian universities. It is mandatory for the universities which are covered under section 12B of the UGC Act, 1956 and receiving grants from UGC to check the plagiarism level in P.D. thesis and Dissertations before approval (Singh Citation2016). Despite organized efforts, plagiarism is a growing concern for regulators and educators in India.

The field study setting was a postgraduate program offered at HEIs in India. The two campuses of the selected institute offered postgraduate programs in Business Studies. These programs were spread over two years and divided into six terms of 14–15 weeks of duration each. Amongst the top HEIs specialized in business studies, the selected institute was accredited by AACSB and AMBA.Footnote1 There was a strong impetus to cultivating academic integrity and combating academic dishonesty among students across all programs. The selection of the study setting was based on the accessibility and ease of participation selection for survey administration considering the association of authors with the institute. This convenience sampling approach to participant selection is common in quasi-experiments and widely employed by past research on dilemmas in ethical decision-making in different contexts (Nguyen and Biderman Citation2008).

This data was collected three consecutive times (referred to as Time 1, 2 and 3) over a period of four months (one term) i.e. July 2022 to October 2022. During this period, a set of structured interventions (described in section 4.2) was implemented for creating plagiarism awareness among students enrolled in a compulsory course on Corporate law, offered in the first term of the program. Students enrolled in this course were selected as subjects for the experiment because, first, the learning objectives of the course align with the study aims (learning objectives- to encourage students to develop responsible Citizen Consciousness and demonstrate ethically conscious decision-making). Second, the pedagogy of the course was case-oriented and therefore students were accustomed to examining ethical dilemmas in hypothesized business situations. Additionally, most students hold prior experience in managerial positions in organizations. A similar sampling approach for drawing a cross-section of participants enrolled for ‘required’ courses in graduate programs was adopted by Nguyen and Biderman (Citation2008). Thus, postgraduate students enrolled for the compulsory course on Business and corporate law in the first term were the subjects of this study.

4.2. Experimental manipulations and timelines

For manipulating the independent variable i.e. plagiarism awareness efforts, a set of experimental treatments reflecting the HEI’s and course instructor’s endeavors to explicate the unethical implications of plagiarism and to help the students identify an ethically correct course of action was implemented during the period of this study. A description of the three treatments used for manipulation is presented.

4.2.1. Treatment-1: library instructions

The participants were familiarized with issues of academic integrity and plagiarism during a classroom session conducted by the Librarian of the school as part of a library orientation program. This orientation program was organized during the second week of the first term for all postgraduate graduate students, and the session duration was 90 mins.

4.2.2. Treatment-2: seminar on plagiarism fundamentals

The participants attended a seminar on plagiarism fundamentals conducted by the course instructor of the Business and Corporate Law course. During this 90-minute seminar, conducted for each section, students were introduced to plagiarism fundamentals such as types of plagiarism practices, its consequences, and ways of avoiding such as the use of quotes and citing sources. The seminar was conducted during the third week of the first term (Appendix A-1).

4.2.3. Treatment-3: email on academic ethics guidelines for course submissions

The participants received written guidelines on academic ethics through email in the fourth week. These guidelines outlined the standards for plagiarism-free work in the conduct of written course submissions such as assignments and project reports. It described rules for ethical writing, similarity index/scores (computation based on Turnitin, an online service for plagiarism detection), and penalties for plagiarized submissions. The email was sent by the course instructor (Appendix A-1).

4.3. Measures

The construct of ethical judgment related to plagiarism is operationalized using the multidimensional ethics scale (MES) developed by Reidenbach and Robin (Citation1990). Rooted in the normative moral philosophies and literature (Ferrell and Gresham Citation1985), the original MES scale comprised 33 items representing five dimensions. For this study, we used the refined MES version based on a single-factor model with eight items signifying the three dimensions i.e. moral equity, relativism, and contractualism (excluding utilitarianism and egoism dimensions). Prior studies on ethical judgments and moral dilemmas in general management (Loo Citation2004), tax & accounting (Cruz, Shafer, and Strawser Citation2000), have used the eight-item MES version and found it to be a reliable and valid measure for ethical reasoning. For this study, the moral equity dimension is defined as students’ perception of fairness and justice and what is right and wrong and measured using four items i.e. unfair–fair, unjust–just, morally wrong–morally right, and acceptable–unacceptable to the family (McMahon and Harvey Citation2007). The relativism dimension is defined as students’ perception of what is right versus wrong based on guidelines rooted in their social system, rather than their reflections. It is measured using two items: traditionally unacceptable–traditionally acceptable; culturally unacceptable–culturally acceptable. The dimension of contractualism dimension is defined as students’ perception of what is right against wrong based on their notions of an implied contract that exists between students and academic institutions. This dimension is assessed using two items: violates–does not violate an unspoken promise, and violates – does not violate an unwritten contract (Nguyen et al. Citation2008). All items were measured on a 5-point scale (1: strongly disagree and 5: strongly agree).

The dependent variable of Ethical behavior related to plagiarism represents the students’ actions according to the school’s standards of academic integrity and plagiarism ethics. It is evaluated using a direct measure i.e. similarity score or index of students’ coursework submissions including assignments and project reports. The similarity index is a percent score assessing how many phrases of a document match to those in a formerly published document. In comparison to self-reported measures of ethical behavior (Newstrom and Ruch Citation1975), a ratio measure of similarity score of students’ submissions offered a reliable measure of students’ ethical behavior in this study. A few studies in academic ethics have used similar direct measures for determining students’ ethical conduct (Bretag and Mahmud Citation2009). We assessed the similarity index of project reports submitted as coursework submissions by the students enrolled in the Business Ethics & Law course offered to the postgraduate program of the institute, selected as the study setting. The index ranged from 0 to 100% based on the extent of text similarity. The submissions were evaluated for similarity index by using Turnitin, a widely used institutional-license-based software tool for plagiarism detection (Garden Citation2009). This tool is used due to its wide acceptance as an instrument to fight plagiarism and to cultivate academic ethics among university/academic institute students (Batane Citation2010; Bretag and Mahmud Citation2009).

Additionally, categorical variables were used to gather participants’ demographic information. The demographic questions solicited participants’ information including their age, gender, work experience, undergraduate academic stream, and internal religiosity. Participants’ internal religiosity was assessed using the item (Religiosity: Participants responded to the question ‘are you religious?’ Participants’ responses yes and no were coded as 1 and 2, respectively) adapted from Mubako et al. (Citation2021).

4.4. Data collection and analysis

A total of 450 students enrolled in the postgraduate Business and Corporate Law course were invited to participate in this study in July 2022 (Time 1). Before the beginning of the study, the course instructor sent an e-mail with a cover letter to students informing them about the purpose of the study, and the voluntary nature of their participation. No student names were collected, and anonymity was assured. To encourage study participation, students completing both the pre-and post-test survey were recorded into a drawing for a US $10 e-gift card. Experimental psychologists have observed that providing compensation (monetary or non-monetary) to subjects for participation improves the response quality (Brase, Fiddick, and Harries Citation2006) and there is no reason to believe that such a practice would induce any systematic bias in the study.

Before implementing interventions to spread plagiarism awareness (described in section 3.2), students across all sections were asked to complete a pretest survey. Following Reidenbach and Robin (Citation1990), the students were presented with a short-written scenario about a dilemma related to plagiarism and actions taken by a hypothetical student. Next, they were asked to complete a self-administered MES survey based on their ethical judgment of the actions taken. Responses were measured on a 5-point Likert scale (1: strongly disagree, 5: strongly agree). In addition to eight items of the MES scale, the survey instrument comprised items on demographic characteristics. Out of 450 students who enrolled for the Business ethics and law course, 311 students participated in the pretest survey.

Next, a set of manipulations reflecting plagiarism awareness efforts were implemented through August 2022 as per the timeline described in section 4.2. The post-test survey was administered to gauge the students’ ethical judgment, one week before the end of the term in October 2022 (Time 2). Only students who participated in the pre-test survey were permitted to participate in the post-test survey. This self-administered survey was conducted in classrooms after presenting another written scenario reflecting a real dilemma in academia facing a hypothetical postgraduate student. Both pre-test and post-test scenarios were designed by the researchers (see Annexure A-2) and presented in the English language, considering it was the language for the course delivery. The purpose of keeping a time gap of over 10 weeks between the two surveys was to diminish the testing effects such as learning effects which may manifest the participants’ post-test scores due to their familiarity with the experiment after the pre-test (Campbell and Stanley Citation1966). 301 students participated in the post-test survey. An overlapping set of 294 responses across the pre-test and post-test surveys was used for analysis. shows the demographics of the study participants. Among these, 54.76% were male 64.97% were more than 25 years and 56.12% had work experience of more than two years. Most of the participants i.e. 69.73% had an undergraduate in the science & engineering stream.

Table 1. Demographics of the study participants.

At Time 3, data for the variable on students’ ethical behavior related to plagiarism was gathered. Turnitin software was used for extracting similarity reports of project work submissions in the last week of October 2022. The project was to develop a case study based on secondary sources on the given corporate scandals. The submission date for the project was two weeks after the post-test. The similarity report provides a summary of the matching text found in the submission and assigns a similarity score per cent. The similarity score is recorded for each of the 294 students who participated in both the pretest and posttest surveys.

For analyzing the experiment data, first, the reliability and validity of the MES constructs i.e. moral equity, relativism, and contractualism were assessed. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted using AMOS-25 for construct reliability and validity checks (Hair et al. Citation2010). Next, for analyzing the impact of plagiarism awareness efforts on students’ ethical judgment responses, paired samples t-test was conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics 26. The impact of participants’ demographic differences on the change in their ethical judgment responses across pre-and post-test scores was analyzed using independent samples t-test and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Structural equation modeling (SEM) was conducted to estimate the path coefficients of structural relationships between participants’ ethical judgments on their ethical behavior (Hair et al. Citation2010).

5. Results

5.1. Reliability and validity checks

CFA was conducted to demonstrate the unidimensionality and validity of the three latent constructs i.e. moral equity, relativism, and contractualism. The construct-wise reliability and validity estimates for the pre-test (T1) and post-test (T2) responses for moral equity (MOR), relativism (REL), and contractualism (CON) are presented in . All the constructs met the criteria i.e. composite reliability (CR), Cronbach α > 0.7, and average variance explained (AVE) > 0.5 (Hair et al. Citation2010).

Table 2. Construct reliability and validity.

For establishing divergent validity, the square root of the estimated AVE between a pair of constructs was compared with the absolute intercorrelation between the constructs (ϕ) following Fornell and Larcker's (Citation1981) approach. The results of the divergent validity are summarized in .

Table 3. Discriminant validity testing.

The fit indices of the measurement model, i.e. CMIN/df (relative chi-square index) = 1.909; CFI (comparative fit index) = 0.933; TLI (Tucker-Lewis index) = 0.99; RMSEA (root-mean-square error of approximation index) = 0.056, met the model fitness criteria recommended by Hu and Bentler (Citation1999) and thus deemed acceptable.

5.2. Hypotheses testing

For testing hypothesis H1 on the positive effect of experimental interventions (treatments 1, 2, and 3 for creating plagiarism awareness) on the change in participants’ ethical judgments, paired samples t-tests were conducted. The tests were used to check the statistical significance of the mean difference in ethical judgment responses in all three dimensions (MOR, REL, and CON) between pre-and post-intervention. This method of statistical analysis is generally used in education research to evaluate the impacts of educational interventions and policies on students’ learning (Gándara and Rutherford Citation2017; Hillman, Tandberg, and Fryar Citation2015). The results of the t-tests are shown in . The results showed that post-intervention scores for all three dimensions of ethical judgments i.e. MOR (mean difference = −0.36; t = 4.67***), REL (mean difference = −0.30; t = 4.43***) and CON (mean difference = −0.54; t = 7.09***) were higher and the mean difference was statistically significant. Thus, H1a, H1b, and H1c were supported.

Table 4. Test of significant difference between pre-intervention and post-intervention responses.

To determine the influence of participants’ ethical judgment dimensions on their ethical behavior i.e. H2, ordinary least square (OLS) regression analysis was conducted. In the regression model, the post-intervention (T2) responses for all three dimensions i.e. MOR, REL, and CON were regressed on participants’ ethical behavior (i.e. similarity index of project reports). Before testing the OLS regression models, assumptions of linearity, normality and homoscedasticity between the independent and dependent variables were assessed (Hair et al. Citation2010). Partial regression plots for the regression model were examined for testing linearity. Residual analysis and normality test were used to confirm the normality of the error term distribution (Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, p-value < 0.05). Further, homoscedasticity was established by evaluating the standardized residual plots. Multicollinearity between the independent variables was assessed using variance inflation factors (VIF). VIF values below 5 (Hair et al. Citation2010) allowed for disregarding this issue. Thus, the assumptions for OLS regression analysis were satisfied. Further, the scores for the three latent constructs were computed by means of the weighted average of original responses with the respective factor loadings as weights. Construct scores were standardized to evade scale effects (Hair et al. Citation2010), and inputted into the regression model. shows the OLS regression results.

Table 5. Regression results.

The results showed significant direct effects of MOR ( = −0.108***, t-value = −4.31, p- < 0.00), and CON (

= −0.122***, t-value = −5.85; p < 0.000) on ethical behavior, thereby supporting H2a and H2c (H2b not supported).

Next, for testing the hypotheses on moderating effect of participants’ intrinsic religiosity (H3a–c), gender (H4a–c), age (H5a–c), and work experience (H6a–c) on the change in their ethical judgment, a comparison of group means was conducted using independent sample t-test (for two group comparison) and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) (for multiple group comparisons. shows the results of a comparison of demographic differences in ethical judgment responses for all three dimensions. The results showed significant differences in MOR scores between participants in two religiosity groups (t value = 4.63, p = .00), thereby supporting H3a supported at 99% confidence. However, H3b and H3c on the moderating effect of participants’ religiosity on their REL and CON scores was not supported by the data. Between the two gender groups, MOR scores (t value = 2.09, p = .03) were significantly different, thereby supporting H4a at 95% confidence, however, H4b and H4c for the difference in REL and CON scores were not supported. Our analysis showed no significant difference in MOR, REL, and CON scores among the three age groups, thus, H5a, H5b, and H5c were not supported. Among the three groups of work experience, a significant difference was found in the MOR scores (F-value = 3.05, p = .03), thereby supporting H6a at 95% confidence). While H6b on the difference in REL scores was supported at 90% confidence (F-value = 2.49, p = .08), H6c on the difference in the CON scores was not supported.

Table 6. Moderating effect of participants’ demographic differences on ethical judgment.

6. Discussion

6.1. Discussion on main results

The first finding of this study underscores the importance of plagiarism ethics awareness efforts (i.e. treatment 1, 2, and 3) to improve students’ ethical judgment in academic settings (H1). A significant difference between the pre-test and post-test ethical judgment scores on all three dimensions (moral equity, relativism, and contractualism) indicates that HEI's efforts to create awareness about plagiarism ethics can significantly improve students’ understanding of ethical concerns surrounding plagiarism. A significant improvement was recorded in students’ overall understanding of plagiarism ethics from the perspective of what is morally wrong in plagiarism, why plagiarism is unacceptable in academic society, and how the act of plagiarism breaches the social contract (H1a, H1b, H1c accepted).

The second major finding of the study highlights the role of students’ ethical judgment in predicting ethical behavior related to plagiarism (H2). The results confirmed that moral equity (H2a) and contractualism (H2c) dimensions of students’ ethical judgments directly impact their ethical behavior related to plagiarism. These results indicate that students’ ethical behavior concerning plagiarism is majorly driven by two ethical perspectives: first, their moral and personal value-based views on fairness and justice, and second the notion of violation of perceived duty toward society. However, relativism dimensions showed an insignificant impact on students’ ethical behavior (H2b rejected). There are two possible explanations for this. First, previous research suggests that generations Y and Z are personally value-oriented, tolerant of cultural differences, adaptive to global cultural/societal values, are far more forgiving (Freestone and Mitchell Citation2004; Pichler, Kohli, and Granitz Citation2021; Weber Citation2017). These traits can explain why in the current times, HEI students’ ethical behavior concerning plagiarism is majorly governed by moral equity and contractualism dimensions and less by cultural relativism. While the relativism dimension concentrates on social/cultural expectations, norms and guidelines, the moral equity dimension is focused on an individual's values (Arli, Tjiptono, and Porto Citation2015; Reidenbach and Robin Citation1990). Since the current HE student generation decides right and wrong based on their personal values and not by the norms and principles of cultural systems confined to a specific society, the cultural relativism dimension becomes less important in ethical decision-making.

Third, the current generation of HE students is more global in their viewpoints and experiences. They tend to demonstrate high respect for the intellectual property rights (ownership and copyrights) of the authors as much as they do for the known authors or peers (Ethics Resource Centre Citation2013). The tendency to honor the ownership rights of unknown authors demonstrates their consideration for the contractualism dimension of ethical judgment. HE students’ perception of acceptable code of behavior in the plagiarism context is based on the notion of violation/non-violation of implicit rules, principles, and promises made with the global society and not just the explicit norms of a specific society/culture. These results support the findings reported by previous studies claiming that Generation Z is more tolerant of social/cultural norms violation (Freestone and Mitchell Citation2004; Rinnert and Kobayashi Citation2005; Ross and Rouse Citation2015).

6.2. Discussion on moderator analysis

The first important finding of the moderator analysis is that religiosity moderated the impact of plagiarism awareness efforts only on the moral equity dimension on ethical judgment (H3a accepted) and not on the remaining two dimensions i.e. relativism and contractualism (H3b and H3c rejected). We found that students with high intrinsic religiosity responded more and better to the institution’s plagiarism awareness efforts which were reflected in their post-test strong moral equity judgments. This finding can be explained by symbolic interactionism theory arguing that a person develops a sense of self-identity in a large group by playing various roles (Nickerson Citation2021). Each of the various roles played by him/her carries specific role expectations and behavioral tendencies gets strengthened with frequent contact with other individuals associated with the corresponding role (Walker, Smither, and DeBode Citation2012). In the plagiarism awareness context, when students are frequently exposed to plagiarism ethical dilemmas and academic ethics policies, the role expectations of HEIs from them get clearer because repeated sensitization exercises increase the salience it has in students’ sense of self-identity. Students with higher intrinsic religiosity treat plagiarism ethics as a goal because they have a higher tendency of treating religious beliefs and moral practices as ends than their counterparts with lower religiosity (Omer, Sharp, and Wang Citation2018; Weaver and Agle Citation2002). Their quest for self-identity motivates them toward moral values and practices associated with the role played by them (Walker, Smither, and DeBode Citation2012). On the other hand, students with lower intrinsic religiosity may not be directly motivated toward role-related moral values and self-identity. Therefore, HEIs plagiarism awareness efforts may show a weaker impact on the moral equity dimension of ethical judgments made by students with lower intrinsic religiosity scores.

Further, we found similar results for moderating the impact of gender. While gender moderated the impact of plagiarism awareness efforts on the moral equity dimension of ethical judgments made by students (H4a accepted), the other two dimensions i.e. cultural relativism and contractualism remained immune from gender difference (H4b and H4c rejected). A group of previous studies argued that males and females respond differently to ethical issues (Friesdorf, Conway, and Gawronski Citation2015; Luo et al. Citation2022; Meyers-Levy and Loken Citation2015) while few others claimed that both are quite similar (Carrigan and Attalla Citation2001; Jaffee and Hyde Citation2000). The contrary results can be understood considering gender differences in the impact of ethics awareness exercises on three broad dimensions of ethical judgment (moral equity, relativism, and contractualism). Our findings provide deeper insights into the contradictory claims made by previous studies suggesting that there is no gender difference in ethical judgments when they are primarily guided by social/cultural norms (relativism) and implicit social duties (contractualism). Ethical awareness efforts will show the same impact on such ethical judgments without any gender difference. However, when the ethicality of an action is judged based on an individual’s moral norms and values (moral equity), ethical awareness efforts will not show an equal impact on both genders. Due to distinctive moral orientations, values, and traits, males and females respond differently to ethics awareness efforts resulting in dissimilar ethical judgments (Roxas and Stoneback Citation2004). For instance, females raise moral questions as a problem of empathy, care, and compassion while males’ moral questions are framed as a problem of justice and rights (Yankelovich Citation1972; Zhou, Zheng, and Gao Citation2019). We found that plagiarism awareness efforts made a significantly higher impact on the moral equity dimension of female students’ ethical judgment than male students. Greater sense of commitment to helping others motivated females to warmly respond to ethics awareness efforts resulting in stronger ethical judgments. Thus, our results support the argument that gender identity is at the core of personality and is irreversible (Roxas and Stoneback Citation2004).

Our results do not confirm moderating impact of age on the influence of plagiarism awareness efforts on students’ ethical judgments (H5 rejected). The results imply that the wisdom acquired by age does not influence students’ ethical judgment. In fact, previous research on ethics provides inconclusive findings on the relationship between age and ethical perceptions (Gupta et al. Citation2011). While results suggest that students’ age may not be a concern, our analysis underscores the importance of considering students’ work experience for HEIs designing plagiarism awareness exercises/policies (H6a and H6c accepted). We found that plagiarism awareness efforts by the institutions showed an unequal impact on moral equity and cultural relativism dimensions of the ethical judgment of students with different work experiences. We found that students with lesser work experience showed the highest difference between pre-test and post-test scores on moral equity and cultural relativism dimensions. And thus, the impact of the Institute’s plagiarism awareness efforts on students’ overall ethical judgment was most visible in this group. We refer to the arguments made by career researchers suggesting that individuals change over time when progress through different career stages (Cron, Dubinsky, and Michaels Citation1988; Marques and Azevedo-Pereira Citation2009). In the initial years of the career (exploration and establishment stages), individuals are committed to the work/occupation assigned to them and tempted to progress in it by following the organization’s/institution’s philosophies even if their individual viewpoints and cultural norms are not exactly aligned with them (Ahmed et al. Citation2022; Cron, Dubinsky, and Michaels Citation1988). Therefore, students who are undergoing initial career stages (with lesser work experience) received plagiarism awareness efforts better than their counterparts resulting in significant improvement in moral equity and relativism dimensions of post-test ethical judgments.

An important takeaway from this study is that the ethical judgments of current HE students are predominantly influenced by how they perceive fairness and justice (moral equity dimension). In simple words, the effect of plagiarism awareness efforts on HE students’ ethical judgments is largely moderated by the moral equity dimension. Current HE students’ (majorly millennials – Gen Z) personal value orientation explains this trend. Recent research uncovered that students from Gen Y & Gen Z are more cautious about personal norms and individual values than social norms and cultural values (Culiberg and Mihelič Citation2016; Weber Citation2019). Popular practices among HE students in the current time, such as clicking selfies, creating hashtags, and freely and frequently posting their personal viewpoints on social media reflect their personal-value orientation (Weber Citation2019). In our study, the impact of HE students’ personal value orientation is clearly visible in their ethical judgments as they placed greater importance on moral values aligned with their principles of justice and fairness (moral equity). Whereas the impact of plagiarism awareness efforts on relativism and contractualism dimensions showed low or no difference across subgroups created by moderators. This reinforces the belief that current HE students’ ethical judgments are predominantly based on individual values and norms. Principles and norms inherent in a society or culture play only a marginal role.

7. Implications for theory and practice

The finding of this experimental study has implications for theory and research methodology. It proposes and uses the well-grounded cognitive moral development theory (Kohlberg Citation1969) and associated measurement constructs (Reidenbach and Robin Citation1990) to offer an understanding of students’ ethical reasoning for plagiarism in HEI settings. It provides an understanding of the moderating effect of students’ intrinsic religiosity and demographic characteristics as well as HEIs’ efforts in shaping students’ ethical behavior.

The study offers several practical implications for HEIs and educators. First, HEIs need to position plagiarism as an ethical issue because students usually do not consider plagiarism as a particularly ethical misdemeanour. In general paraphrasing, academic content without acknowledgement, written cut and paste, and fabricating bibliographies are perceived as just minor misconduct by students (Barrett and Cox Citation2005; Sheard, Markham, and Dick Citation2003). Previous studies on plagiarism issues in higher education consistently suggested that the best way to prevent plagiarism in HE is to create awareness of academic and plagiarism ethics (Abbas et al. Citation2021; Ramzan et al. Citation2012). For instance, Nwosu and Chukwuere (Citation2020) suggested that HEI must have a comprehensive policy defining academic dishonesty and plagiarism. Clear guidelines pertaining to what constitutes plagiarism should be attached to the group assignments and projects. Likewise, Ramzan et al. (Citation2012) recommended that the plagiarism ethics policy of the HEI should be made prominently visible to all stakeholders by publishing it in students’ handbooks, official websites and through plagiarism awareness programs. Through these efforts, a clear and strong message can be sent to HE students about zero tolerance for academic dishonesty. However, there will always be some who will indulge in plagiarism despite relevant knowledge of plagiarism ethics. Therefore, HEIs and universities should continue deploying technology and plagiarism-detection software and strictly implement anti-plagiarism policies. Thus, a balance of prevention, detection and punishment is required to reduce plagiarism cases in HEIs (Jereb et al. Citation2018). Our results corroborate the claims of several previous studies that efforts directed toward plagiarism awareness can substantially improve students’ ethical judgment on plagiarism (Abbas et al. Citation2021; Pan and Sparks Citation2012; Ramzan et al. Citation2012). HEIs should make a dedicated effort to design and conduct plagiarism awareness exercises not only to disseminate information about plagiarism but also to position the act of plagiarism as an unethical act. The use of compelling case-based scenarios explaining the moral issues, academic society norms, and implicit duties toward society can provoke HE students’ critical thinking about the ethicality of plagiarism actions both on micron and macro levels. This can help students think beyond a pragmatic understanding of plagiarism and consider plagiarism acts in an ethical context.

Second, the finding of this study reveals that HE students’ ethical judgments are primarily determined by their personal moral values instead of social/cultural norms. They may not have a feeling of ethical guilt even if the questioned act which is aligned with their personal values, violates social/cultural norms. (Weber Citation2017). In simple words, HE students’ ethical behavior will largely depend on their moral and value-based views and how they justify plagiarism (Mihelič and Culiberg Citation2014). If they judge that plagiarism is unfair, wrong, and unjustifiable, such judgment is more likely to lead to ethical behavior in their academic pursuits. Therefore, plagiarism awareness exercises and policies of HEIs should explain how plagiarism conflicts with the sense of justice, rightness, and moral obligation. The personal value orientation of HE students should be duly considered while designing and conducting plagiarism awareness exercises. Overemphasis on cultural/social norms may not lead to desired ethical behavior unless students feel that plagiarism constitutes a serious violation of moral values (Jones Christensen, Mackey, and Whetten Citation2014).

Third, HE students’ strong to contractualism dimension of ethical judgment reflects their respect for global societal norms. The current generation of HE students is more global in their viewpoints and experiences. They tend to demonstrate high respect for the intellectual property rights (ownership and copyrights) of the authors as much as they do for the known authors or peers (Ethics Resource Centre Citation2013). Therefore, in the plagiarism awareness exercises and policies, HEIs should strongly emphasize global societal norms and students’ implicit duties toward global society to reduce their tolerance for plagiarism violations.

Fourth, the results of the moderator analysis indicated that students with high religiosity scores are highly motivated to follow role-related moral values and therefore are likely to follow plagiarism ethics (Walker, Smither, and DeBode Citation2012). However, their counterparts may not demonstrate the same behavior. Therefore, HEIs plagiarism awareness efforts may show a weaker impact on the moral equity dimension of ethical judgments made by students with lower intrinsic religiosity scores. HEIs should duly consider these findings while conducting plagiarism awareness exercises as differences in students’ intrinsic religiosity may enhance or constrain the impact of sensitization exercises on their ethical judgments.

Additionally, HEIs and educators should not forget that ethical judgments are gender sensitive, and gender is the core element of an individual’s personality. Females are found to be more sensitive toward ethical concerns. Therefore, ethics awareness efforts may not very much change the way male students perceive fairness or justice at the individual level while the same may not be true for female students (Roxas and Stoneback Citation2004). Lastly, our results indicate that students with lesser work experience responded more positively to plagiarism awareness efforts than their counterparts. This is an important finding suggesting that HEIs should consider the students’ career goals and motivations associated with different career development stages while developing plagiarism ethics education programs. Because tolerance for misalignment between an individual's personal moral values, cultural/societal norms, and ethical norms of the institution may not be the same for all students having unequal work experience.

8. Conclusion

To understand the interaction of students’ ethical reasoning for plagiarism and the responsibility of institutes/universities to promote ethical behavior, the study empirically examined the impact of HEIs’ efforts to create plagiarism awareness among students on students’ ethical judgments which in turn shapes students’ ethical behavior. The study provided deeper insights into these relationships by analyzing the moderating impact of individual-level factors. A set of three experimental interventions reflecting the HEI's endeavors to explicate the unethical implications of plagiarism revealed that HEI’s efforts to disseminate plagiarism-related rules and guidelines and to position plagiarism as an unethical act boosted students’ ethical beliefs related to moral equity, relativism, and contractualism. The significant individual-level factors that moderate the impact of HEI’s efforts on students’ beliefs in moral equity were religiosity, gender, and work experience. Further, the findings showed a significant role of students’ ethical judgments inspired by moral equity and contractualism in envisaging their ethical behaviors in academic settings.

8.1. Limitations and future research directions

One limitation of this study is that the experimental subjects are postgraduate students. Prior studies on ethical behaviors in HE contexts have used student participants and reached insightful conclusions (Christensen, Cote, and Latham Citation2016; Mubako et al. Citation2021). Moreover, the current students of postgraduate business studies are future business leaders, thus, we believe there is value in the study. Further research studies may compare different student groups (e.g. undergraduate, graduate, postgraduate) in terms of their observed ethical judgments and behaviors related to academic dishonesty. Another limitation of the experiment design used in this study is an analysis of the combined effect of plagiarism awareness efforts (treatments 1, 2 and 3) on students’ plagiarism behavior. Future studies may examine how different plagiarism efforts (e.g. emailing anti-plagiarism instruction, dedicated classroom sessions on plagiarism ethics) had a greater or lesser impact on student’s plagiarism behavior. Another limitation is the duration of our longitudinal quasi-experiment study was 16 weeks (appx. 4 months). Although this duration may be considered an appropriate time frame for a full-time higher education program of two years, however, the ethical behavioral outcomes measured at a later point in time may provide more accurate predictions of causal effects. Thus, future studies may measure the effects of plagiarism-related interventions and policies in a longer time frame.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (238.4 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Awarded by global accreditation bodies to the institute for a continuous focus on quality in student learning, teaching, research, and curriculum development.

References

- Aaker, J. L. 1989. “The Malleable Self: The Role of Self-Expression in Persuasion.” Journal of Marketing Research 36 (1): 45–57. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224379903600104

- Abbas, A., A. Fatima, A. Arrona-Palacios, H. Haruna, and S. Hosseini. 2021. “Research Ethics Dilemma in Higher Education: Impact of Internet Access, Ethical Controls, and Teaching Factors on Student Plagiarism.” Education and Information Technologies 26 (5): 6109–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-021-10595-z

- Abdullah, A., Z. Sulong, and R. M. Said. 2014. “An Analysis on Ethical Climate and Ethical Judgment among Public Sector Employees in Malaysia.” Journal of Applied Business and Economics 16 (2): 133–42.