ABSTRACT

Changing relationships between government and the higher education system have created a wide range of new tasks within universities. Many have been adopted by an emerging workforce known alternately as professional, non-academic, or support staff. Its rapid growth has sparked a debate about ‘administrative bloat’. We aim to move beyond this negative, dismissive framing by reviewing the literature to explore whether and how professional staff influence academic knowledge development. While this specific question has received little scholarly attention, we found relevant research in 54 documents from a diffuse group of journals and authors. Our review makes two specific contributions. First, we examine the competencies and relationships of professional staff and their influence on conditions and processes in universities. We find that professional staff increasingly have a private sector background, but that the implications of such a background for competencies remain opaque. Furthermore, their relationships with university leadership and academics as well as actors beyond the home organization place them in strategic positions in their networks. We claim that their involvement in strategy development and implementation, daily management, and academic practices demonstrate a potential to influence knowledge development. Second, we propose a research agenda to understand this influence. The agenda is built around the institutional logics of professional staff, the institutional work that they engage in to promote these logics, and the resulting influence on knowledge development. We hypothesize that professional staff stimulate convergence in knowledge production and strengthen the higher education system’s external legitimacy as a producer of knowledge.

1. Introduction

In this article we review the literature related to the influence of professional staff (PS) on academic knowledge development in the higher education (HE) system. Based on a review of definitions and descriptions of PS and 18 related terms in the literature, we define PS as ‘degree holding university employees who are primarily responsible for developing, maintaining and changing the social, physical and digital infrastructures that enable education, research and knowledge exchange’ (De Jong Citationin press). This definition builds upon descriptions of PS such as Whitchurch’s (Citation2008, 379) as employees with ‘academic credentials such as master’s and doctoral level qualifications’ and adds a focus on their function of enabling primary tasks (c.f. Gibbs and Kharouf Citation2020; Kallenberg Citation2016). It not only includes PS whose responsibilities closely relate to research, such as grant advisers who enable the acquisition of financial resources for research, but also PS who enable research in other ways, such as human resource managers who enable the recruitment of research staff. This new definition of PS allows us to integrate the state of art and propose a research agenda with the aim of improving our understanding of their influence on academic knowledge development, which will complement our current understandings of PS as a category of university employees (see the body of work on ‘third space professionals’ by Celia Whitchurch or a study by Schneijderberg (Citation2015), for example).

A changing relationship between governments and the HE system in the United Kingdom, the United States of America, and several member states of the European Union, such as Denmark and the Netherlands, introduced new organizational tasks in universities in the late twentieth century and early twenty-first century. From the 1980s onwards, governments aimed to make universities more efficient and productive (e.g. Bleikli Citation2018; Deem and Brehony Citation2005). To this end, they granted more autonomy to the boards of universities to enable them to operate in a market-like environment (Ferlie et al. Citation2009). This resulted in a demand for strategic, financial, and legal support (Gornitzka and Larsen Citation2004; Kehm Citation2015b). At the same time, governments introduced performance agreements and quality monitoring (Braun Citation2005), for which performance figures had to be collected (Leslie and Rhoades Citation1995; Rhoades Citation2009). Besides providing education and developing new knowledge, universities were also expected to transfer their knowledge more effectively to industry, which required commercialization competencies (Rhoades and Slaughter Citation1991). Additionally, the performance of these new tasks had to be coordinated, which resulted in an increase of the number of managers in universities (Stage and Aagaard Citation2019). The general strive for efficiency induced further task specialization (Macfarlane Citation2011; Musselin Citation2013).

The complex and ongoing organizational shifts in HE over the past several decades have thus resulted in a workforce comprising a highly diverse set of jobs. For example, it includes administrators, information technology staff, student counselors, quality assurance staff, financial controllers, human resource managers, institutional researchers, and technology transfer professionals (Allen-Collinson Citation2007; Gander, Girardi, and Paull Citation2019; Gibbs and Kharouf Citation2020; Harman and Stone Citation2006; Kallenberg Citation2016; Rosser Citation2004; Szekeres Citation2011). Over the past half century, the share of this group of staff notably increased in several countries, such as the US (since the mid-1970s) (Gumport and Pusser Citation1995; Leslie and Rhoades Citation1995; Rhoades Citation2009; Rhoades and Sporn Citation2002), Norway (since the late 1980s) (Gornitzka and Larsen Citation2004) and Denmark (since the early 2000s) (Stage and Aagaard Citation2019). In prominent HE systems, including the UK (Gibbs and Kharouf Citation2020), Australia (Croucher and Woelert Citation2021; Gander Citation2018; Gray Citation2015), and the US, the share of these types of jobs is currently between 50% and 60%.

Rhoades (Citation2009) suggests making distinctions within this set of new jobs based on responsibilities (managerial or administrative), work content (involved in or closely related to education and research or not), educational background (vocational or academic) and position within the organization (central, or local, such as the school or department level). We refer to the academically trained part of this workforce as ‘professional staff’, as this is the preferred term of the employees themselves (Sebalj, Holbrook, and Bourke Citation2012), and is the most commonly used term in the literature (Whitchurch Citation2020).

Both in popular and academic debate, the increase of PS has been pejoratively referred to as ‘administrative bloat’, which is linked to the bureaucratization of universities (e.g. Ginsberg Citation2011; Hedrick, Wassell, and Henson Citation2009) and accounts of managed academics (Rhoades Citation1998). Although more nuanced perspectives on PS are presented, for instance in the body of work of Whitchurch, existing research questions largely revolve around ascertaining whether PS are ‘good’ or ‘bad’ for HE systems. Coccia (Citation2009), for instance, finds a negative relationship between the time researchers in Italian public research labs spend on administrative procedures and research output. Andrews, Boyne, and Mostafa (Citation2017), however, found a positive relationship between the relative size of the administration of universities in the United Kingdom and research performance. Baltaru (Citation2019) did not find an effect on research quality in British universities, measured as Research Excellence Framework scores, but did conclude that a moderate increase in the share of professional staff positively affects degree completion.

Despite the rise in numbers of PS, the polarized popular discourse, and contradictory findings in the academic literature about the effects of their presence on universities’ organizational performance, PS remain an understudied component of universities compared to academics and university leadership (Angus Citation1973; Bossu, Brown, and Warren Citation2018; Derrick and Nickson Citation2014). Most of the studies that go beyond numbers either focus on characteristics and identities of PS or on their relationships with academics (often portrayed as challenging). For example, reviews are available about job satisfaction (Bauer Citation2000; Johnsrud Citation2002), career development (Gander Citation2018), organizational tasks and roles (Schneijderberg and Merkator Citation2013), relationships with academics (Schneijderberg and Merkator Citation2013; Szekeres Citation2011) and the general debate about PS (Veles and Carter Citation2016). (See Whitchurch and Schneijderberg (Citation2017) for a more detailed overview of the different discussions around changing characteristics and identities of PS.)

In particular, we found little qualitative work with the main aim of understanding the influence of PS on the primary task of research, moving beyond the binary debate of either positive or negative effects. The above-mentioned quantitative studies by Andrews, Boyne, and Mostafa (Citation2017) and Baltaru (Citation2019) are exceptions, but do not shed light on how these influences come about. Hence, we argue that complementary to conceptualizing PS as a group of employees, unravelling the mechanics of their influence on the primary tasks of universities is an opportunity for further theory development (Whetten Citation1989). In other words, we see an opening for HE researchers to move the popular debate beyond whether PS are a help or a hindrance to research and education, by asking how they influence – and are influenced by – processes of academic knowledge development, both as individuals and as a fluid and developing collective. Our goal with this review is to facilitate this movement by bringing together the diffuse body of research that examines the specific characteristics, connections and activities of PS and, based on this literature, drawing inferences about the influence of PS on academic knowledge development.

This review paper is structured as follows. In the next section, we explain our methodology, which consists of a review of 54 documents about PS. Section 3 comprises the first contribution of this review: taking stock of the dispersed research about PS’s contributions to academic knowledge development. For contributions to occur, we assume that there must be a foundation of competencies, by which we mean knowledge, skills and other personal characteristics, such as attitudes (Boyatzis Citation1982). These competencies enter the academic knowledge production system through the relationships of PS with other actors, and their involvement with objects (such as policy documents) and processes (such as strategy development). Hence, if we aim to unravel the influence of PS on academic knowledge development, we should (1) characterize their competencies, developed during training and in practice, (2) map their professional relationships, and (3) understand the potential avenues of influence that their competencies and relationships These are the three main dimensions that guide our review. In Section 4 we discuss a research agenda to motivate further empirical studies about PS as well as theory building, with the ultimate goal of creating a more detailed and nuanced picture of the contribution of PS to academic knowledge development. The research agenda is the second contribution of this review. The overarching question in this agenda is ‘What is the influence of PS on transformations in knowledge development in the HE system and how do these influences come about?’ We propose to make use of the meta theory of institutional logics (Thornton and Ocasio Citation1999), which deals with the patterns that inform our thinking and behavior, and the concepts of institutional work (Lawrence and Suddaby Citation2006), which explains how everyday activities of individuals may affect these patterns, to deepen our understanding of the role of PS in transforming HE. We then draw on actor-network theory (Latour Citation1987), an approach for understanding social processes of knowledge production, and the cycle of credit (Latour and Woolgar Citation1986), a concept explaining how conversions of resources drive research, to delve into how PS influence knowledge development specifically. In Section 5 we conclude our review.

2. Method

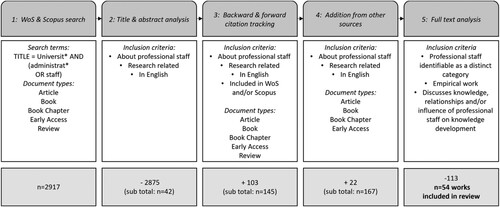

We conducted a literature review of publications on PS in English. Our method consists of six steps, which we explain below and which we have visualized in .

Step 1: Web of Science (WoS) and Scopus search

As PS remain under-researched (Bossu, Brown, and Warren Citation2018; Derrick and Nickson Citation2014; Rhoades Citation2009), we expected the literature to be dispersed, so we cast a wide net. We searched the WoS (June 21, 2021) and Scopus (July 13, 2021) for titles containing: universit*Footnote1 AND (administrat* OR staffFootnote2). At all steps in the process articles, books, book chapters, reviews, and ‘early access’ in the case of WoS, were included, unless otherwise indicated. The WoS search resulted in 1136 documents and the Scopus search in 2219 documents. After removing 438 duplicates, step 1 resulted in 2917 unique documents.

Step 2: Title and abstract analysis

We selected documents that, based on the title and abstract fields, (1) were written in English, (2) were unambiguously about PS and (3) discussed their direct or indirect role in research. To establish whether a document met criterion 2, in several instances we had to consult the main text to determine whether ‘administrators’ referred to PS or to university leadership. We retained 42 out of the initial 2917 documents.

Step 3: Backward and forward citation tracking

We aimed to capture documents meeting our inclusion criteria that our database searches did not retrieve due to variation in terms used to describe PS. National differences add to this complexity, as particular roles may have different job titles in different countries (Acker, McGinn, and Campisi Citation2019; Bossu, Brown, and Warren Citation2018), making it infeasible to search for individual job titles.Footnote3 We repeated the forward and backward citation tracking for each document that we identified until we no longer found documents that were not already included in our set. Step 3 resulted in the identification of an additional 103 documents.

Step 4: Other sources

We added documents meeting our inclusion criteria from alternative sources, including articles indexed in the WoS and Scopus that peers recommended during presentations of our work in progress, articles from journals that are not included in these databases, and chapters from recently published books. In this step, in which we did not include reviews, we added a total of 20 additional documents.

Step 5: Full text analysis of the collected literature

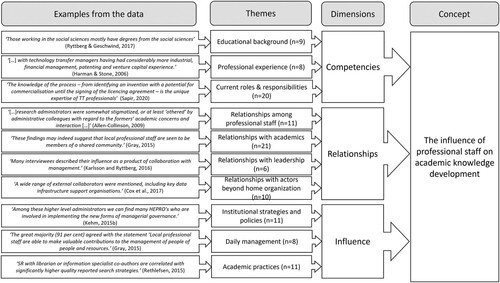

We only included documents that presented original empirical work, thus excluding reviews (although we used their reference lists in step 3) and opinion pieces in this final step. The remaining documents were analyzed in NVivo (version 12.6.1) software for qualitative analysis. Our analysis is inspired by the Gioia methodology (Gioia, Corley, and Hamilton Citation2012), which guides systematic inductive qualitative analysis. During full-text analysis of the 167 documents that resulted from step 4, we used our expert judgement to determine whether they discussed any of the three broad dimensions, competencies, relationships, and influence. Only documents that present empirical work related to at least one of the three dimensions are included in the review. Additionally, we only included documents in which we could clearly identify PS as a distinct category of staff. Studies that unrecognizably grouped PS with academic staff in the presentation of results were excluded, for instance. , in Section 3, shows the resulting data structure based on the analysis of the remaining 54 documents.

2.1. Description of the dataset

Our final data set includes 54 documents: 8 book (chapter)s and 46 articles from 26 different journals and 71 unique authors. The relatively large number of journals compared to the number of articles confirms our expectation that the discussion about PS is dispersed. In we present the most prominent journals and authors in the final data set. It stands out that four of the five most-represented authors (Whitchurch, Allen-Collinson, Ryttberg and Szekeres) have been or are employed as PS.Footnote4 gives insight into the coverage of countries and organizational roles in the reviewed documents. A total of 24 countries are represented as research contexts. Taken together, the UK and Australia account for almost half of the included studies. Only five specific organizational roles (the top 5 in ), receive detailed, but not necessarily stand-alone, attention in more than one document in the set.

Table 1. Most prominent journals and authors in final data set.

Table 2. Most prominent countries and organizational roles covered in final data set.

Although an elaborate report on the theoretical and methodological foundations of the included studies falls beyond the scope of this paper, we believe that the following observations deserve mentioning. Regarding theoretical foundations, eighteen studies introduce the context of the research and provide a brief discussion of the literature (e.g. Berman and Pitman Citation2010; Pinfield, Cox, and Smith Citation2014; Sanches Citation2015), and fifteen studies provide a more comprehensive literature review (e.g. Joo and Schmidt Citation2021; Kehm Citation2015b; Wohlmuther Citation2008), but none of these studies explicitly elaborate a theoretical or conceptual framework. A total of fifteen studies do include a conceptual framework, often drawing on identity (e.g. Allen-Collinson Citation2006; Whitchurch Citation2010), neoliberalism (e.g. Beime, Englund, and Gerdin Citation2021; Krücken, Blümel, and Kloke 2013) and the ‘Third Space’ (e.g. Daly Citation2013; Kallenberg Citation2016). The remaining six studies draw on institutional theory (e.g. Ryttberg Citation2020; Sapir Citation2020 (in combination with boundary work)), multi-level governance theory (Qu Citation2021), network theory (Ryttberg and Geschwind Citation2017), sense-making theory (Ryttberg and Geschwind Citation2019), and social practice theory (Shelley Citation2010). With respect to methodology, seventeen studies use interviews (e.g. Acker, McGinn, and Campisi Citation2019; Gibbs and Kharouf Citation2020; Karlsson and Ryttberg Citation2016), another seventeen employed a survey (e.g. Cox and Verbaan Citation2016; Szekeres and Heywood Citation2018) and ten developed a mixed-methods approach (e.g. Beime, Englund, and Gerdin Citation2021; Hockey and Allen-Collinson Citation2009). The methods of the remaining studies are document analysis (n = 5); case studies (n = 3) or were not detailed (n = 2).

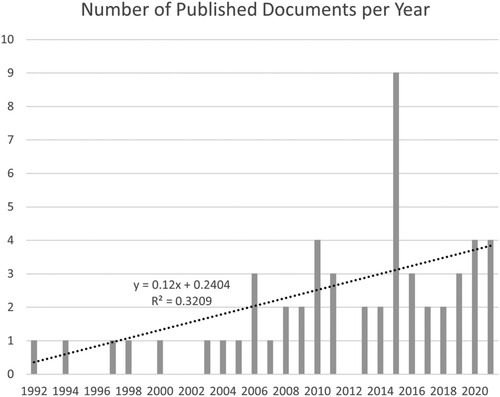

Finally, despite PS remaining understudied (Bossu, Brown, and Warren Citation2018; Derrick and Nickson Citation2014; Rhoades Citation2009) the distribution of documents included in our dataset over the years demonstrates a small upward trend (see ). This trend and the publication of the book edited by Bossu, Brown, and Warren (Citation2018) suggests a rising interest in PS as a topic for scholarly studies.

3. Competencies, relationships, and influence

In this section we present the results of our literature review, which entails the first contribution of this review. presents the data structure that resulted from the analysis of the documents, including the number of documents that discussed each theme within brackets – please, note that a document may discuss multiple themes. This structure will support the discussion about the proposed research agenda to further our understanding of the influence of PS on academic knowledge development in Section 4 as well.

3.1. Competencies

Studies that explicitly consider the competencies of PS are a minority in our set, though many documents provide hints as to what these competencies might entail. A study by Schneijderberg (Citation2015) stands out in this respect, and finds that PS in Germany consider ‘communication skills, sense of responsibility, organization and planning skills, self-reliance, knowledge of the organization and processes, resilience/stress-resistance, and time management skills’ to be the most important competences for their work. Our analysis of the literature resulted in three main themes regarding the development and application of PS competencies: (1) educational background, (2) professional experience and (3) current role and responsibilities.

3.1.1. Educational background

Although the figures differ between countries, it seems to be an international trend for PS to increasingly have obtained master and even doctoral degrees (Kirkland and Stackhouse Citation2011). Some authors link this increase to more demanding job qualifications (Gornitzka and Larsen Citation2004; Shelley Citation2010), whereas others link the increase in doctoral degrees in particular to the professional credit it provides (Allen-Collinson Citation2007; Szekeres Citation2011). These percentages also seem to differ between PS roles. A doctorate seems to be the most common in research support (Acker, McGinn, and Campisi Citation2019; Ryttberg and Geschwind Citation2017) and technology transfer (Berman and Pitman Citation2010; Krücken, Blümel, and Kloke 2013), where at least a third and in some cases a significant majority holds a doctorate degree. PS link the skills obtained while pursuing their advanced degrees to being successful in their current roles (Acker, McGinn, and Campisi Citation2019).

Some authors have investigated PS’s disciplinary backgrounds, which also seem to correlate with organizational roles. A humanities degree is most common in roles related to internationalization and quality management (Krücken, Blümel, and Kloke 2013; Ryttberg and Geschwind Citation2017), whereas a social sciences degree is reported to be more common in career services and post-academic training (Krücken, Blümel, and Kloke 2013), and a natural sciences or engineering degree, and to some extent a legal degree, are common in technology transfer (Harman and Stone Citation2006; Ryttberg and Geschwind Citation2017). Krücken, Blümel, and Kloke (2013) report that in Germany a legal background is decreasingly common for the heads of university administration, whereas the importance of a background in the social sciences, humanities, economics, and business administration is on the rise.

3.1.2. Professional experience

Differences in professional backgrounds prior to taking up PS roles correlate with current roles and responsibilities as well. In research management and support, many PS have experience as (post-doctoral) researchers. Backgrounds in the public sector, for instance at research councils or public research institutes, and the private sector seem to be equally common in this group (Acker, McGinn, and Campisi Citation2019; Ryttberg and Geschwind Citation2017; Shelley Citation2010). On the other hand, experience in the (international) private sector is more common among those working in technology transfer. PS with this background bring in competencies related to financial management, patenting and venture capital and experience in consultancy, entrepreneurship, project management and research (Ryttberg and Geschwind Citation2017). Those working in development and alumni relations bring in their experience from the non-profit sector (Daly Citation2013).

Yet, the professional background of PS is changing, with public sector or academic experience being increasingly supplanted by private sector experience (Karlsson and Ryttberg Citation2016; Krücken, Blümel, and Kloke 2013). For instance, Szekeres and Heywood (Citation2018) studied faculty managers, typically the most senior PS role at faculty level, at Australian universities and found that within this subgroup of PS the influx from the private sector increased from 30% to 45% between 2004 and 2016, whereas that from the public sector had decreased from 40% to 20%. The authors conclude that universities nowadays are ‘more interested in those who come with business or commercial skills’. Shelley (Citation2010) writes that ‘Some [in research management and support] had previously worked in business or industry and brought with them flavors of those work cultures’.

3.1.3. Current role and responsibilities

The three most prominent subthemes regarding competencies that are related to PS’s current role and responsibilities are their home organization, the environment in which that organization operates, and academic processes. These competencies support the design of adequate steering and monitoring mechanisms (Kehm Citation2015b) and thereby support PS’s role in developing and implementing the strategies of universities (Karlsson and Ryttberg Citation2016).

Knowledge about the home organization first concerns knowledge about explicit policies, as is for instance the case for technology transfer officers, who are responsible for ensuring academics’ compliance with the intellectual property policies of their university (Sapir Citation2020), and for those involved in fundraising, who need an understanding of the university’s mission (Daly Citation2013). Furthermore, knowledge about universities’ organizational structures and processes helps PS to leverage influence and, perhaps for this reason, is an important selection criterion when hiring new managers (Krücken, Blümel, and Kloke 2013; Schneijderberg Citation2015; Whitchurch Citation2015). Second, it concerns tacit knowledge about the operation of universities (Harman and Stone (Citation2006)). More specifically, Hockey and Allen-Collinson (Citation2009) find that knowledge about the home organization helps PS to navigate meetings thanks to their awareness of sensitive topics, which helps them and the academics they support to achieve their goals. This finding resonates with Whitchurch’s (Citation2015) observation that political awareness without becoming partial helps to participate in debates while safeguarding trust.

A second subtheme concerns the environment in which the home organization operates. For example, Berman and Pitman (Citation2010) found that PS in research administration and support believe that their knowledge of the national and international research environment is foundational to the work that they are responsible for. Stackhouse and Day (Citation2005), Harman and Stone (Citation2006), Hockey and Allen-Collinson (Citation2009) and Cox and Verbaan (Citation2016) all suggest that research administrators are or must be aware of policies of funding bodies and government programs to successfully translate these to organizational strategies and day to day responsibilities. For instance, to ensure that the organization performs well in national research evaluations (Allen-Collinson Citation2006). According to both Karlsson and Ryttberg (Citation2016) and Qu (Citation2021) this policy awareness also constitutes detailed knowledge on political priorities and European level funding schemes. Daly (Citation2013), provides further evidence of the importance of this type of knowledge: ‘She [a director of development who helped an academic to secure a donation] advised the donor on the benefits of giving via the then-government’s match funding scheme’.

The final subtheme relates to academic practices. Some of these practices, such as applying for funding, have been introduced or amplified by the changing relationship between government and universities that we have described in the introduction. Often, PS concentrate on specific academic practices, which allows them to develop specialized competencies. For example, regarding technology transfer officers, as Sapir (Citation2020) notes: ‘The knowledge of the process – from identifying an invention with a potential for commercialization until the signing of the licensing agreement – is the unique expertise of TT professionals, i.e. their know-what’. Similarly, librarians have become experts in research data management, including the requirements set by funders, and information retrieval (Antell et al. Citation2017), and the publication process, which for instance includes open access publishing and copyright issues (Cox and Verbaan Citation2016). Research administrators, on their turn, have developed specialized competencies in the context of external funding. These members of PS know how to identify funding opportunities; develop funding applications, including financial and ethical aspects as well as internal approval and agreements with partners; and manage projects, including financial management and reporting to funders (Acker, McGinn, and Campisi Citation2019; Allen-Collinson Citation2009; Allen-Collinson Citation2007; Harman and Stone Citation2006; Qu Citation2021; Shelley Citation2010). Furthermore, faculty managers have specialized in financial and business skills (Szekeres and Heywood Citation2018) and directors of development and alumni relations have developed expertise in the identification and management of donors (Daly Citation2013). Finally, as Whitchurch (Citation2015) found, the understanding of academic practices is key to understand the difference in rhythm between academic and administrative work and that academics may need time to get familiar with this difference.

3.2. Relationships

Developing and maintaining relationships are at the core of PS’s work (Daly Citation2013; Hüther and Krücken Citation2018, 210; Szekeres and Heywood Citation2018). We identified four categories of relationships: (1) among PS, within and beyond home organizations, (2) with academics, (3) with organizational leadership and (4) with other actors beyond their home organization. Remarkably we have not found detailed discussions of relationships with other university employees that have a direct role in research, such as technical staff (c.f. Shapin Citation1989) or clinical staff, or may have a more indirect role, such as clerical staff.

3.2.1. Relationships among PS

The first subtheme of relationships among PS are the tensions between different departments and categories of PS. For instance, Allen-Collinson (Citation2009) found that those closely working with research and academics were othered by their colleagues whose work did not relate as directly to research. On top of that, tensions may also occur within the same category of professional staff. In a study on research administration, Shelley (Citation2010) found that central offices regularly exclude local offices from meetings or do not welcome their contributions to discussions.

Other authors write about positive working relationships. Several studies indicate that other members of PS are the primary information source for PS (Sprague Citation1994; Wilkins and Leckie Citation1997). Also, members of PS often need to collaborate to achieve their goals, for instance by having their requests prioritized by their colleagues (Hockey and Allen-Collinson Citation2009) or because of working on joint projects. Pinfield, Cox, and Smith (Citation2014) found that in the collaborative development of research data management programs by librarians, IT staff and legal advisers, different perspectives and even disagreements were taken for granted, while at the same time good relationships, especially between managers of different units, were perceived as crucial to move the program forward. A study by Joo and Schmidt (Citation2021), also on research data management, echoes these results. Furthermore, Ito and Watanabe (Citation2021) found that ‘the knowledge-sharing environment perceived by research management professionals had a significant positive relation with external research funding at the organizational level’. It might therefore be no surprise that managers of PS units or joint projects strive to establish positive working environments (Whitchurch Citation2015).

A smaller number of authors write about deliberately formed networks of PS, both within and between organizations. These networks provide opportunities for joint problem solving, knowledge acquisition and reflection (Gornitzka and Larsen Citation2004; Ryttberg and Geschwind Citation2019; Shelley Citation2010). A global survey among research managers found that almost-three quarters of respondents were managers of such professional networks (Stackhouse and Day Citation2005).

3.2.2. Relationships with academics

Although a global study among research managers shows that half of the respondents felt highly valued by academics (Kirkland and Stackhouse Citation2011), a considerable number of authors observe a tension between PS and academic staff (e.g. Allen-Collinson Citation2007; Dobson Citation2000; Mcinnis Citation1998; Szekeres Citation2011). This divide may contribute to the often problematic and frustrating relationship between the two categories of staff (e.g. Allen-Collinson Citation2006; Citation2009; Daly Citation2013; Gibbs and Kharouf Citation2020; Szekeres Citation2006).

Yet, other authors argue for the existence of fuzzy boundaries between the work of PS and academic staff (e.g. Kallenberg Citation2016; Whitchurch Citation2015), often discussed within the context of the Third Space Professional framework developed by Whitchurch (Citation2008). Gray (Citation2015)’s findings even ‘suggest that local PS are seen to be members of a shared community’ by academics. Qu (Citation2021) observes that PS’s relationships with a wide variety of academics allow them to facilitate the development of academic networks.

Conditions that influence the development of positive relationships between PS and academics are the first’s competencies related to research processes and academic culture, indicated by a doctoral degree, as well as the accumulated competencies related to their current role, which provide trust and credibility (Berman and Pitman Citation2010; Ryttberg Citation2020; Takagi Citation2015). Yet, having a doctorate but no longer holding an academic position could also lead to the perception of ‘a failed academic’ (Whitchurch Citation2015). Frequently joining meetings in which academics are present (Qu Citation2021; Ryttberg and Geschwind Citation2019) and involvement in the education of students further support the development of relationships with academics (Cox and Verbaan Citation2016). PS also provide formal education to academics regarding issues that enter academia from the policy domain, such as research data management (Joo and Schmidt Citation2021), and such professional education is another way for PS to get in touch with academics (Sanches Citation2015).

3.2.3. Relationships with organizational leadership

PS’s relationships with organizational leadership, such as presidents, rectors, deans, and heads of academic departments, seem to have received less attention in the reviewed literature than the other two types of relationships within the home organization. In these relationships, PS collaborate with presidents, vice-chancellors, and rectors to develop and implement organizational strategies, by arranging meetings with relevant individuals, having conversations and meetings with internal and external parties and drafting documents (Daly Citation2013; Karlsson and Ryttberg Citation2016). More operational aspects are part of this relationship as well. PS may provide leadership with information and guidance regarding the execution of specific tasks, such as fundraising. All in all, a good relationship with organizational leadership is ‘an important success factor’ for PS (Ryttberg and Geschwind Citation2017). A global study among research managers showed that a small majority felt highly valued by organizational leadership (Kirkland and Stackhouse Citation2011).

3.2.4. Relationships with actors beyond the home organization

Relationships with key actors beyond their home organization is the fourth subtheme of relationships that PS engages in. Yet, we found little concrete information about these relationships. One possible explanation is that although PS consider external relationships to be of importance, internal responsibilities often do not allow them to invest in such relationships (Daly Citation2013).

The concrete relationships with actors beyond the home organization seem to be closely tied to the responsibilities of particular categories of PS. For example, librarians cooperate with national data services providers (Cox et al. Citation2017), (directors of) policy staff with ministries of research and education (Frølich, Christensen, and Stensaker Citation2019) and technology transfer officers collaborate with companies and government agencies (Harman and Stone Citation2006). Directors of development nourish relationships with (potential) donors (Daly Citation2013) and research administrators establish links with funders to better understand their policies and to inform academics about these policies (Cox and Verbaan Citation2016; Stackhouse and Day Citation2005). Internationalization officers maintain relationships with funders and embassies as well as governments and universities abroad (Qu Citation2021). Such relationships require considerable time to develop and maintain trust but enable PS to become aware of policy and organizational changes early on and thus to do their job (Hockey and Allen-Collinson Citation2009).

PS have specific functions in these relationships. First, in the case of supporting leadership in their interactions with external partners, they secure continuity as they often occupy the same post longer than leadership (Frølich, Christensen, and Stensaker Citation2019). Second, in case of supporting academics in their relationships with external partners, they broker between knowledge users on the one hand and academics on the other hand (Sapir Citation2020) and may promote, negotiate, and authorize formalization of such relationships (Kirkland and Stackhouse Citation2011; Stackhouse and Day Citation2005).

3.3. Influence

In this section we discuss the findings on PS’s influence on the conditions and processes within HE, as a first step to understanding how this leads to direct or indirect influence on academic knowledge development.

Some authors doubt whether PS have influence within universities. These authors conclude that power in universities still lies with academics and that the influence of PS is therefore limited (Gornitzka and Larsen Citation2004; Kehm Citation2015a; Wohlmuther Citation2008). Kallenberg (Citation2020) briefly explains this position by stating that ‘knowledge is power, and knowledge lies with the academics’. This statement implies that research is the sole source of knowledge. As we have seen in Section 3.1, PS acquire and exchange their own particular competences, including knowledge. This knowledge may equally serve as a source of influence, for example in advisory roles which provide opportunities for convincing others (Whitchurch Citation2015) and raising specific issues within the organization (Krücken, Blümel, and Kloke 2013).

Indeed, other authors do believe that PS exert influence. Whitchurch (Citation2015) writes that, according to PS, the absence of formal power is precisely the basis of their influence as it allows them to operate under the radar. Some even observe a transfer of powerfrom academics to PS (e.g. Macfarlane Citation2011; Shelley Citation2010). Schneijderberg (Citation2015) states that the influence of PS may differ across national higher education systems, which could explain the contradictory perspectives in the literature.

The studies that do attribute some influence to PS found that they exert it over three aspects of the university: (1) the longer-term strategy of universities (2) daily management of the university and (3) academic practices. The first two types can be seen as indirect influence onknowledge development through shaping the conditions in which it occurs. The third type constitutes direct influence on knowledge development.

3.3.1. Strategies and policies

PS influence the strategies of universities through the policies that they develop (Acker, McGinn, and Campisi Citation2019; Kirkland and Stackhouse Citation2011; Shelley Citation2010; Stackhouse and Day Citation2005), projects that they launch and support (Whitchurch Citation2015), and by preparing leadership for meetings by informing them about sensitive issues, potential sources of resistance and counterarguments (Hockey and Allen-Collinson Citation2009). Frølich, Christensen, and Stensaker (Citation2019) observe that the role of PS in strategic processes has become more important. In some cases, the authors noticed, PS were even in control of implementing policies. Although in contrast to organizational leadership PS often do not have formal authority, they do have more time and capacity to collect and interpret information and determine their input for discussions (Karlsson and Ryttberg Citation2016). PS’s influence is further strengthened as their tenure in a particular position increases, as this positively correlates with requests for and acceptance of advice (Schneijderberg Citation2015); the (co-)initiation of policy development (Cox et al. Citation2017) and in some cases even autonomous operating from academic leadership (Higman and Pinfield Citation2015; Takagi Citation2015). Through these activities, PS contribute to transforming the organizational structure of universities (Shelley Citation2010), with some authors finding that they make universities more strategic and goal oriented (Karlsson and Ryttberg Citation2016), and, based on self-reporting by PS, increase the reputation and income of their organization (Kirkland and Stackhouse Citation2011).

3.3.2. Daily management

Furthermore, PS contributes to the professionalization of daily management of universities (Kehm Citation2015b). Following increased financial authority (Mcinnis Citation1998; Szekeres and Heywood Citation2018), their influence on daily operations seems to primarily concern the management of financial and human resources (Gray Citation2015) and projects funded by external partners (Stackhouse and Day Citation2005). Henkin and Persson (Citation1992) as well as Gray (Citation2015) suggest that in some instances academics are willing to hand over control of these resources to local level PS to improve their management. By taking up such bureaucratic work that used to be the responsibility of academics (Cox and Verbaan Citation2016), academics perceive local level PS to lower their workload without introducing new red tape and bureaucratic procedures. For central level PS, however, academics do perceive them as increasing the bureaucracy (Gray Citation2015). Apart from managing resources, PS remind other actors in the university of its strategic goals and how to achieve them (Karlsson and Ryttberg Citation2016). Thus, one result of the influence of PS on daily management of universities is an increased focus on productivity and efficiency (Szekeres Citation2006).

3.3.3. Academic practices

Thirdly, PS may influence knowledge development directly via their involvement in academic practices. Most papers that discuss this involvement focus on funding acquisition and collaboration. PS write and review up to half of all applications and organize organizational approval before submission (Shelley Citation2010; Stackhouse and Day Citation2005). As a result, on the one hand PS have the potential to positively influence the acquisition of research funds (Ito and Watanabe Citation2021; Qu Citation2021), while on the other hand promoting the policy objectives of research funders, for example around collaboration, interdisciplinarity, open access and societal impact (Cox and Verbaan Citation2016). This may affect project designs, for instance concerning consortia composition and dissemination plans (Qu Citation2021). Additionally, grant support officers strengthen the competitive attitude of academics through proposal writing trainings (Stackhouse and Day Citation2005), and by informing them about funding opportunities and corresponding ‘rules of the game’ as well as preparing them to compete with other researchers (Beime, Englund, and Gerdin Citation2021). In the words of the Beime, Englund, and Gerdin (Citation2021), they are ‘a form of “mediator” between neoliberal markets and those that populate such markets (i.e. the researchers) […]’, facilitating the marketization of academia. In collaborations with companies, technology transfer officers rely on their prior experience with such interactions to facilitate the communication between academics and companies (Szekeres Citation2006) and provide training on intellectual property, for instance (Stackhouse and Day Citation2005). PS may even use their competencies to make academics comply with policies of their university and organizations in their university’s environment, such as funders. In doing so, they draw on their knowledge of these policies, such as on intellectual property rights, research data management or even laws, for instance in the case of copy-right issues, (Cox and Verbaan Citation2016; Sapir Citation2020; Pinfield, Cox, and Smith Citation2014). PS are also involved in the training of doctoral students and staff (Schneijderberg Citation2015), which can serve as a conduit for influencing academic practices. Furthermore, our dataset includes documents that discuss how traditional tasks of librarians, for example literature searches, improved academic output (Ducas and Michaud-Oystryk Citation2003; e.g. Rethlefsen et al. Citation2015). As we are interested in PS in the context of shifts in roles and responsibilities, we have decided not to discuss the effects of such contributions and instead focus on their new tasks, such as promoting open access.

Finally, it may not come as a surprise that, due to the lack of formal power, an important condition for the influence of PS seems to be their relationship with organizational leadership (Karlsson and Ryttberg Citation2016). The closer PS and leadership collaborate and the more frequent their communication is, the more influence PS can have on strategies and daily management (Krücken, Blümel, and Kloke 2013) and thereby on academics and academic knowledge development. As PS often also have close relationships with academics they can act as a buffer (Allen-Collinson Citation2006) or broker (Ryttberg Citation2020) of information between them and leadership, which puts them in a potentially influential position.

4. Moving research on the influence of PS forward

In Section 3 we discussed the existing research on the competencies, relationships and finally the influence of PS on conditions and processes of the university. Taken together, these begin to reveal their influence on knowledge development specifically. In this section, we build upon these insights to propose a research agenda to facilitate future research into this topic. Rather than aiming to further conceptualize professional staff as a category of university employees, the proposed agenda aims to understand their influence on knowledge development. The following agenda is the second contribution of this review.

4.1. Overarching research question

Given the changing competencies, relationships with key actors in the HE system and increased influence on strategy and daily management of universities, the overarching research question that we propose to guide further research on PS is: ‘What is the influence of PS on transformations in knowledge development in the HE system and how does this influence come about?’

As discussed above, some authors have argued that PS exert little or no influence within HE.. Maassen and Stensaker (Citation2019) attribute this to the de-coupling of administrative processes from primary processes in universities. Abbot’s (Citation1998) perspective on professions helps in interpreting task division. He states that professionals gain the most status from engaging with professional knowledge. Tasks that do not engage with professional knowledge do not contribute to status and may even harm it. To maintain exclusive and uncompromised engagement with professional knowledge, professionals will delegate tasks that require interaction with the outside world with others, who, as a result, have lower status (Abbot Citation1988, 119). In higher education this general development of task division can be recognized in the surge of PS following the introduction of new tasks beyond the core of academic work and related to the changed relationship between governments and HEIs from the 1980s onward: here, academics are Abbot’s professionals, delegating the lower-status work of interacting with the outside world to PS.

Yet, as our review shows, and as the name professional staff implies, PS constitutes a rapidly growing, highly educated and specialized, and well-connected new profession. It is hard to imagine that such a workforce that is establishing its own jurisdiction, body of expertise and networks to allocate resources (c.f. Liu Citation2018) has no influence on academic knowledge development at all. From a cynical perspective, one would at least expect PS to affect academic knowledge development through diverting financial resources to administrative processes.

Based on our review, however, we expect their influence to be more profound. Although the precise nature of their contributions is open for investigation, our review allows for formulating expectations. For instance, the specialization of PS in specific tasks on the one hand and the development of professional networks on the other hand leads to the development of shared perspectives and practices. Consider, as an example, shared perspectives on ‘competitiveness’ of resumes of researchers or particular research topics and methods. Such perspectives inform research administrators in their roles as trainers who instruct academics in writing funding proposals as well as gatekeepers who determine which applications may be successful in competitions and will therefore receive organizational support (Beime, Englund, and Gerdin Citation2021; Stackhouse and Day Citation2005). In such ways we anticipate that shared perspectives and practices will translate into homogenization processes across the HE system (DiMaggio and Powell Citation1983). We therefore expect that PS contribute to convergence in academic knowledge development to an even greater degree than professional networks of academics already achieved, whereas knowledge development benefits from a diversity of approaches (Danchev, Rzhetsky, and Evans Citation2019). Another example concerns PS’s contribution to safeguarding resources for the HE system. We anticipate that their knowledge of and interaction with governments and other funders, including companies, on the one hand and their involvement in developing policies in response to the requirements of these actors on the other hand is crucial to maintaining the HE system’s legitimacy as a producer of knowledge (Hessels, van Lente, and Smits Citation2009). Maintaining this legitimacy may only entail safeguarding the status quo that enables the continuation of knowledge development, but it might also involve reshaping perspectives on what type of research to promote, for example in terms of topics, collaborators, or distance to application, to maintain HE’s legitimacy as a producer of knowledge.

Below we suggest further investigations to fill the gaps in the existing literature about each of the three themes of our review: competencies, relationships, and influence of PS on conditions and processes in HE. We also suggest analytical lenses, drawn from organizational studies and science & technology studies, that we believe will be useful in increasing our understanding of how PS are influencing academic knowledge development.

4.2. Competencies & institutional logics

Our review suggests that the competencies of PS are changing. Not only do they increasingly have master and doctoral degrees, their disciplinary and professional backgrounds are changing as well. One of the most notable developments, which several authors write about, is the growing number of PS with experience in the private sector. As Whitchurch and Gordon (Citation2009) argue, the frequent exchange of staff between universities and other organizations ‘suggests that influences from elsewhere are likely to permeate’. The influx of external competencies is a potential driving force behind transformations in the HE system that influence academic knowledge development. Our understanding of what these competencies entail, however, is limited.

The lens of institutional logics (IL) (Thornton and Ocasio Citation1999) can clarify how new competencies of PS change the conditions for research. Thornton and Ocasio (Citation1999, 804) define IL as ‘the socially constructed, historical patterns of material practices, assumptions, values, beliefs and rules by which individuals produce and reproduce their material subsistence, organize time and space, and provide meaning to their social reality’. Put differently, IL are foundational to what we think and do. Thornton, Ocasio & Lounsbury (Thornton, Ocasio, and Lounsbury Citation2012, 77) argue that competing logics provide ground for transformations. We pose that the rapid surge of a new body of staff constitutes a significant change and therefore may have profound effects on IL, which, we believe, justifies the IL lens to study the influence of PS (Suddaby Citation2010).

Our own reading of a recently reviewed body of literature about IL in HE by Cai and Mountford (Citation2021) shows that only 16 out of 54 publications include PS and only one is exclusively about PS. In this study, Oertel (Citation2018), however, surveyed diversity and inclusion officers to analyze university-level logics rather than aiming to identify the logics of the respondents. Such an approach in which PS are included as units of observation, rather than the unit of analysis, is common in the other available studies about IL in HE (e.g. Bruckmann and Carvalho Citation2018; Larsen Citation2020; Wang and Jones Citation2021).

In other words, the IL that drive the thinking and acting of PS are hardly explored. A better grasp of their logics would help to understand how PS may influence the conditions for academic knowledge development. For example, aligning more with a professional logic, do they prioritize reputation within the academic community, or, following a market logic, status beyond the HE system? Through their involvement in strategy development and implementation, such positioning could influence the balance between curiosity-driven and societal challenge-driven research priorities of universities, for instance.

Shields and Watermeyer (Citation2020) developed a survey with 28 statements to measure the IL of academic staff that could be adapted to identify the logics of PS. For example, these statements consider the role of universities to stimulate entrepreneurialism, provide academic freedom, or develop knowledge that improves people’s lives. The authors identified ‘utilitarian’, ‘autonomous’ and ‘managerial’ logics, which roughly correspond to market, professional and state logics (Thornton, Ocasio, and Lounsbury Citation2012) respectively, to be present among academic staff.

Considering qualitative approaches (see Reay and Jones (Citation2016) as well), documents related to the development and maintenance of PS’s professional identities could be analyzed to understand their changing logics and competencies, for instance: syllabi of educational programs in HE and research management and professional organizations such as the European Association of Research Managers and Administrators and the Society of Research Administrators International; abstracts submitted for presentation during professional conferences, such as the International Network of Research Management Societies; or job advertisements for PS (cf. Krücken, Blümel, and Kloke 2013).

4.3. Relationships & institutional work

We have grouped the relationships of PS into four categories: among PS, with academics, with leadership, and with other actors beyond their home organization. PS seem to mediate relationships between academics and leadership within their organization and between academics and external actors, such as funders and companies, who often are not communicating directly. Such strategic positions enable them to control information flows (Burt Citation2005) and might further facilitate the introduction of new logics into universities. Previous research has characterized these relationships in terms of their nature, the role of PS in these relationships and the conditions that affect these relationships. To move from understanding PS as individuals and as a group of employees to understanding their effect on knowledge production in HE, a fuller characterization of these relationships and their secondary and higher order connections will be useful. Furthermore, how PS make use of their brokering positions and what is actually exchanged in their relationships remains rather unclear, yet is essential to our understanding of how the IL of PS and other actors align or compete.

In mapping out the relationships that PS cultivate within and outside of their organizations, the birds-eye perspective of social network analysis (see for example Easley and Kleinberg (Citation2010) for an introduction to core concepts and applications) may be useful as we seek to understand the location of PS in their organizations and in the knowledge-producing HE system. A combination of survey and other quantitative techniques, such as analyzing LinkedIn data, could be used to map the social networks of PS at different levels.

The concept of ‘institutional work’ (IW) (Lawrence and Suddaby Citation2006) helps to reveal how PS actively create, maintain, and disrupt IL in their relationships by showing how micro-level processes embedded in everyday practices and routines (rather than deliberate actions captured by the concept of institutional entrepreneurship) contribute to institutional change (Wilmott Citation2011). Examples of such everyday activities are PS involvement in implementing organizational strategies and managing financial and human resources., Thus, IW could be a foundation to evaluate the influence of PS by means of process – and contribution-oriented methods of their activities rather than result-and attribution-oriented methods. Modell (Citation2022) adds that the lens of IW may help to understand how peripheral actors, such as PS, may become new elites who enforce their norms on others. We propose that studying IW in the relationships of PS will improve our understanding of their influence on transformative change in the HE system and research in particular and the IW of non-top executives in general (Lawrence et al. Citation2013). Simultaneously, this lens will also support further theorizing of the reported challenges in the relationship between PS and academics (e.g. Schneijderberg and Merkator Citation2013; Szekeres Citation2011), as competing logics could be a cause for these challenges. In our dataset, Sapir (Citation2020) is the only author who makes use of the concept of IW to study PS. Her promising results show that technology transfer officers support the creation of market logics that introduce the interests of companies to academic knowledge development, while simultaneously conducting maintenance work to protect academic professional logics against these interests.

Although we believe that studying PS through the lens of IW can increase our understanding of PS influence on transformations in the HE system that in turn affect academic knowledge development, some critical remarks are justified. First, developing such understanding requires nuanced accounts rather than ‘“heroic” depictions of individual agents, driving through change in a relatively forceful and unconstrained manner’ (Lawrence et al., Citation2009, 5.) for which applications of the IW framework have been criticized. Second, it requires attention for the interplay between IW and institutions, that we may access by comparing across types of HEIs and countries (Lawrence and Suddaby Citation2006). See Wilmott (Citation2011) and Modell (Citation2022) for additional critical reflections on the application of IW.

In addition to interviews, which are Sapir’s (Citation2020) main tool, observing interactions between PS and other actors in everyday work settings can help to capture the IW of PS. Analyzing consecutive draft documents authored by PS in the context of the development of a concrete strategy or policy can also be valuable in this respect, as well as the trainings and educational materials that PS provide to academics, following Beime et al.’s (Citation2021) study about grant support officers. Combining this qualitative data with social networks analysis can reveal how IW embedded in relations between different types of actors leads to the diffusion of logics within and between organizations in the HE system.

4.4. Influence, interactions & cycles of credit

The influence of PS on knowledge development via their involvement in strategy and policy development and implementation as well as daily management has hardly been studied and deserves further attention. A major question in this respect is whether PS are change agents themselves or whether they are merely channels through which leadership and organizations beyond the home organization influence academic knowledge development. To capture whether and how PS influence academic knowledge development, future research must focus on how PS’s IL and the results of their IW translate into concrete influence on the process, form, and content of research, either directly through negotiations with academics or indirectly via strategy and policy development as well as daily management.

In order to move from a general understanding of the IL and work of PS, to a specific understanding of how they influence research, we need a strategy that specifically addresses knowledge production. We propose to use a combination of actor-network theory (e.g. Latour Citation1987) and the Cycle of Credit (Latour and Woolgar Citation1986). Actor-network theory is both an approach that understands knowledge production as the results of the interactions of individuals, institutions, and non-humans, and their interests, as well as a set of strategies for mapping these networks and analyzing how they produce acceptance of certain forms of knowledge. The theory is therefore well-positioned to assist in analyzing how research is influenced by a connected set of academics and PS (as well as others) within and beyond universities.

To trace this influence, ethnographies of specific research efforts can be conducted. Once the network of relationships of PS are mapped out, how the research travels through this network and how it is modified by PS along the way can be examined. For instance, to an academic this research effort may represent an opportunity to increase their reputation within their peer community; to a grant adviser it may represent a project for which funding can be attracted; to an ethics adviser or data protection officer it may come across as a potential threat to the reputation of the organization; to an accountant it may represent an influx and outflux of resources; to a technology transfer officer it may represent a potential collaboration with industry; whereas a communication adviser may see it as a way to increase the visibility of the organization in the wider community. This hypothetical example, though limited to actors within a university, already suggests that the same research project can mean many different things to different actors within an organization. We hypothesize that what the research means to PS reflects both their organizational role as well as their particular IL, and that shaping research is both a mode and a result of IW. The question then is, how do the different interests of the involved actors and the interaction of these interests affect research efforts?

Latour and Woolgar’s (Citation1986) Cycle of Credit conceptualizes academic knowledge development by explaining how academics convert reputation into money, money into people and equipment, people and equipment into data, data into arguments, arguments into publications and publications back into reputation, starting a new cycle. As such, it serves as a perspective to link activities of PS to specific elements of knowledge development. We anticipate that PS contribute to academic knowledge development by affecting cycles of credit quantitatively, for instance by changing conversion rates (e.g. grant advisers who help to more effectively convert reputation into money or technology transfer officers who temporarily stall publications to secure intellectual property rights) or qualitatively, for instance by creating short cuts (e.g. technology transfer officers who assist in selling data to companies, skipping arguments, publications and reputation in the cycle). In the latter hypothetical but realistic example, we note the IW that may be taking place in the relationship between academics, for whom publications are essential aspects of their professional reputation, and tech transfer officers who must convince the academics to accept the tradeoff of investing time in commercialization rather than publication. Moreover, the nature of the resulting knowledge and its influence in society is likely to be different, demonstrating the potential of PS to intervene in influential ways in the networks that produce knowledge by linking a whole other set of actors (in this case, companies) to the conventional academic network. Comparable to understanding PS’s relationships and the IW that they embed, interviews and observations, for example through longer-term ethnographic studies in PS departments, will further our understanding of PS influence.

We recommend that colleagues who address any aspect of this research agenda consider national and disciplinary differences, as these are known to influence knowledge development (e.g. Whitley Citation2000). Regarding the first, we welcome studies that represent national contexts other than Australia and the UK and shed light on PS in HE systems in which the state has a stronger direct involvement in HE governance, such as in countries in southern Europe. As management practices differ across different types of universities (Paradeise and Thoenig Citation2013), future studies should be sensitive to organizational differences as well. For instance, we expect PS’s influence to be larger in non-elite universities. Contrary to elite universities, in those universities strategy making no longer is an ongoing and collective effort of leadership and academic staff but has become the exclusive domain of leadership, supported by professional staff, and is implemented top down (Paradeise and Thoenig Citation2013). Studies into non-elite universities could nuance statements about the limited influence of PS that are based upon analyses of elite universities (e.g. Maassen and Stensaker Citation2019). Hence, we suggest including the perspectives of PS, academics, and institutional leadership in the suggested studies to gain a better understanding of the relationships between these groups.

A final remark concerns subgroups of PS. The literature predominantly discusses those groups whose work directly relates to academic knowledge development, such as librarians, research administrators and technology transfer professionals (Kivistö and Pekkola Citation2017). In our dataset, Daly’s (Citation2013) study on directors of development is a rare exception. Although their work does not directly relate to research, these directors can be understood as influencing the conversion of reputation (on the level of the organization) to financial resources that enable knowledge development. Similarly, financial controllers and human resources professionals may affect the conversion of money into equipment and people through policies and advice, whereas institutional researchers and communication advisers may influence the conversion of publications into (organizational) credit by providing input for international rankings of universities and generating media presence, respectively. As such, groups of PS whose work does not directly relate to knowledge development, may still affect the conditions for it. The vast majority of documents that we reviewed do not consider these groups. Hence, we call for specific attention to these groups in furthering our understanding of the contributions to transformations in knowledge development in the HE system.

5. Conclusion

Changes in the relationship between governments and HE have introduced new tasks which have largely been taken up by a new group of employees: professional staff. The rise in numbers of professional staff has been negatively characterized as ‘administrative bloat’ that detracts from the research and teaching functions of the university (e.g. Ginsberg Citation2011). Yet, empirical data of the role that this large and heterogeneous group plays in the transformation of knowledge production from the microscopic to system-wide scale – data that would allow HE researchers and other stakeholders to assess these charges of administrative bloat – is scarce. To move beyond rhetoric around this understudied group of university employees, in this review paper we (1) took stock of the existing insights about PS’s influence on academic knowledge development and (2) proposed a research agenda to further our understanding of this influence. To this end, we have reviewed 8 book (chapter)s and 46 articles from 26 journals that we collected by means of a WoS and a Scopus search from the highly dispersed literature on PS. Three broad themes guided the analysis of the literature: competencies, relationships, and influence.

As a first step towards a better understanding of the contribution of PS academic knowledge development, the review of the literature shows that their competences are rooted in their educational and professional background as well their current roles and responsibilities; that they engage in relationships with other members of PS, academics, institutional leadership and organizations in the environment in their home organization; and that their influence on knowledge development can be indirect, via their involvement in developing and implementing strategies and policies on the one hand and daily management on the other hand, and direct, via their involvement in academic practices.

The research agenda that we propose revolves around the question ‘What is the influence of PS on transformations in knowledge development in the HE system and how does this influence come about?’. In seeking answers to this question, we believe that the meta theory of IL (Thornton and Ocasio Citation1999), the concept of IW (Lawrence and Suddaby Citation2006) and the methodology of actor-network theory (e.g. Latour Citation1987) grounded in the Cycle of Credit (Latour and Woolgar Citation1986) provide a set of analytical tools to understand how micro-level actions of PS contribute to macro-level changes. Hence, the proposed knowledge agenda aims to shed light on what academic knowledge development in a future HE system, influenced by the logics of PS, may look like.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank two anonymous reviewers, James Evans, the members of the Knowledge Lab at the University of Chicago, Reetta Muhonen, Andreas Kjaer Stage, Silje Marie Tellmann, Susi Poli, Alessandra Migliore and participants in the ‘Organizing Academia’ theme of the 38th EGOS Colloquium for their valuable comments during the development of this review paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 To test whether the term ‘university*’resulted in the exclusion of relevant publications, after step 4 we conducted alternative WoS searches using ‘college*’ (no relevant documents retrieved) and ‘higher education’ (8 relevant documents retrieved, which were already included in our set). Similarly, we replaced ‘administrat* OR staff’ by ‘manager* OR officer*’, which did not result in the retrieval of additional relevant documents. This suggests that our decision to cast a wide net did not result in major blind spots.

2 Our results are limited to scholarly publications included in these databases. PS have authored such publications (see step 5 and table 1), and authors with current or previous positions as PS dominate the top 5 of most represented authors in our dataset. Yet, by excluding gray and professional literature we may not fully do justice to all perspectives of PS. Realizing this potential bias, we still believe that our review of scholarly literature contributes to further both scholarly and professional and debates about the contribution of PS to academic knowledge development.

3 To verify whether our strategy based on searching for more general terms excluded relevant publications, we searched for documents that included ‘research administrators’, ‘accountants’, ‘human resource managers’ and ‘business developer*’ in their title in addition to ‘universit*’ but excluding ‘administrat* OR staff’. This yielded only one relevant result that was not yet included in our dataset (Kirkland and Stackhouse Citation2011). We added this document as well as one document included in its references (Stackhouse and Day Citation2005) in Step 4. Again, this suggests that our decision to cast a wide net did not result in major blind spots.

4 To be transparent, SdJ previously worked an impact and grant adviser, and central level policy officer at Leiden University and CdJ previously worked as a librarian at Wesleyan University.

References

- Abbot, A. 1998. The System of Professions: An Essay on the Division of Expert Labor. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

- Acker, S., M. McGinn, and C. Campisi. 2019. “The Work of University Research Administrators: Praxis and Professionalization.” Journal of Praxis in Higher Education 1 (1): 61–85. https://doi.org/10.47989/kpdc67

- Allen-Collinson, J. 2006. “Just ‘non-Academics’?: Research Administrators and Contested Occupational Identity.” Work, Employment and Society 20 (2): 267–88. https://doi.org/10.1177/0950017006064114.

- Allen-Collinson, J. A. 2007. “Get Yourself Some Nice, Neat, Matching box Files!’ Research Administrators and Occupational Identity Work.” Studies in Higher Education 32 (3): 295–309. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070701346832.

- Allen-Collinson, J. 2009. “Negative ‘Marking’? University Research Administrators and the Contestation of Moral Exclusion.” Studies in Higher Education 34 (8): 941–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070902755641.

- Andrews, R., G. Boyne, and A. M. S. Mostafa. 2017. “When Bureaucracy Matters for Organizational Performance: Exploring the Benefits of Administrative Intensity in Big and Complex Organizations.” Public Administration 95 (1): 115–39. https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12305.

- Angus, W. S. 1973. “University Administrative Staff.” Public Administration 53 (1): 17–39. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9299.1973.tb00125.x

- Antell, K., J. B. Foote, J. Turner, and B. Shults. 2017. “Dealing with Data: Science Librarians’ Participation in Data Management at Association of Research Libraries Institutions.” College & Research Libraries, https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.75.4.557.

- Baltaru, R.-D. 2019. “Do non-Academic Professionals Enhance Universities’ Performance? Reputation vs. Organisation.” Studies in Higher Education 44 (7): 1183–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2017.1421156.

- Bauer, K. W. 2000. “The Front Line: Satisfaction of Classified Employees.” New Directions for Institutional Research 2000(105) (105): 87–97. https://doi.org/10.1002/ir.10508.

- Beime, K. S., H. Englund, and J. Gerdin. 2021. “Giving the Invisible Hand a Helping Hand: How ‘Grants Offices’ Work to Nourish Neoliberal Researchers.” British Educational Research Journal 47 (1): 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1002/berj.3697.

- Berman, J. E., and T. Pitman. 2010. “Occupying a ‘Third Space’: Research Trained Professional Staff in Australian Universities.” Higher Education 60 (2): 157–69. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-009-9292-z.

- Bleikli, I. 2018. “New Public Management or Neoliberalism, Higher Education.” In The International Encyclopedia of Higher Education Systems and Institutions, edited by P. N. Teixeira and J. C. Shin, 2338–41. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Bossu, C., N. Brown, and V. Warren. 2018. “Professional and Support Staff in Higher Education: An Introduction.” In Professional and Support Staff in Higher Education, edited by C. Bossu and N. Brown, 1–8. Singapore: Springer.

- Boyatzis, R. E. 1982. The Competent Manager: A Model for Effective Performance.

- Braun, D. 2005. “How to Govern Research in the “Age of Innovation”: Compatibilities and Incompatibilities of Policy Rationales.” In WZB Discussion Paper 2005-101, New Governance Arrangements in Science Policy, edited by M. Lengwiler and D. Simon, 11–37. Berlin: Social Science Research Center Berlin .

- Bruckmann, S., and T. Carvalho. 2018. “Understanding Change in Higher Education: An Archetypal Approach.” Higher Education 76 (4): 629–47. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-018-0229-2.

- Burt, R. S. 2005. Brokerage and Closure. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Cai, Y., and N. Mountford. 2021. “Institutional Logics Analysis in Higher Education Research.” Studies in Higher Education 0 (0): 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2021.1946032.

- Coccia, M. 2009. “Research Performance and Bureaucracy Within Public Research Labs.” Scientometrics 79 (1): 93–107. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-009-0406-2.

- Cox, A. M., M. A. Kennan, L. Lyon, and S. Pinfield. 2017. “Developments in Research Data Management in Academic Libraries: Towards an Understanding of Research Data Service Maturity.” Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology 68 (9): 2182–200. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.23781.

- Cox, A. M., and E. Verbaan. 2016. “How Academic Librarians, IT Staff, and Research Administrators Perceive and Relate to Research.” Library & Information Science Research 38 (4): 319–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2016.11.004.

- Croucher, G., and P. Woelert. 2021. “Administrative Transformation and Managerial Growth: A Longitudinal Analysis of Changes in the non-Academic Workforce at Australian Universities.” Higher Education, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-021-00759-8.