ABSTRACT

Evidence suggests that many higher education institutions have difficulty in managing student expectations around assessment and feedback, particularly on the clarity of criteria and the fairness of outcomes. Because of its importance students also have strong emotions linked to the process, as do those who teach them. This research sought to explore how students and staff think and feel about assessment and feedback and the implications for assessment literacy. It adopted an interpretive methodology, using qualitative data from focus group interviews combined with an innovative technique of using cartoon illustrations, which were annotated by participants. The results revealed the wide range of emotions associated with assessment and feedback amongst both students and staff. Most emotions were negative. Students feel uncertain about the tasks set. The data also revealed a lack of dialogue between students and staff, with staff often actively avoiding it for fear of conflict. An underlying issue seemed to be that students did not understand many of the backroom processes and roles related to assessment and feedback, partly because of obscure terminology such as ‘moderation’ and ‘unfair means’. This points to deficits in assessment literacy, but the extent of existing staff emotional labour suggests that a literacy lens is inadequate in itself and we should consider the role of wider structures in creating failures of dialogue. The innovative cartoon annotation method was successful in bringing out aspects of both the emotional and cognitive experience of assessment, including hidden assumptions.

Introduction

Assessment and feedback are critical parts of learning, but they are rather complex processes, open to differing interpretation and misunderstanding. For example, much of the jargon around the process in the Higher Education (HE) context, such as ‘moderation period’, ‘anonymous marking’ or ‘external examiner’, is far from transparent. Explanations offered in student handbooks tend to be written in a bureaucratic style. Assessment descriptions often also have low readability (Roy, Beer, and Lawson Citation2020). This may explain why National Student Satisfaction surveys in the UK continue to show that many students, albeit a minority, still do not feel that assessment is clearly explained or fairly marked (Office for Students Citation2019).

Assessment and feedback are surrounded by many emotions for students. Students have a strong investment in a positive outcome from a process that they evidently do not fully understand or trust. Furthermore, it is an area where staff are also inevitably conflicted, because they both desire to foster learning and need to offer objective assessment. Given their different roles, students and staff are bound to experience the process very differently emotionally, but this creates ample room for misunderstanding and conflict. Research suggests that feedback is too often a one-way transmissive process that lacks the sort of dialogic exchange, which might help address these misunderstandings and differing emotions (West and Turner Citation2016; Yang and Carless Citation2013).

Recent work around feedback literacy has pointed to the need for students to be seen more as active partners in a dialogue than as passive recipients of information. For this to be possible, students need to develop the skills to recognise the value of feedback, evaluate quality in work and take action to improve, whilst managing their feelings (Carless and Boud Citation2018; Molloy, Boud, and Henderson Citation2020). Teachers on their side need the literacy to design learning to give students these cognitive skills, manage practicalities and be sensitive to the emotionality of feedback (Carless and Winstone Citation2020).

It follows that examining the alignment of student and staff understanding and emotions are central to improving the important processes of assessment and feedback. In this context, the purpose of this study is to explore differences in the understanding and feelings about assessment and feedback between students and staff. More specifically, it seeks to answer the following research questions:

What are the differences between students’ and teachers’ perception of assessment and feedback?

What emotions do students and staff experience during assessment and feedback?

What are the implications for our understanding of assessment literacy?

In searching for an answer to these two questions, we need methods that give voice to tacit beliefs and the emotion associated with assessment and feedback. Arts-based methods are increasingly being used in educational research because they have this sort of quality. In this study, we explored the use of a novel type of data collection method, cartoon annotation.

The paper begins by examining evidence of differing perceptions of assessment and feedback, before considering its emotional aspects for students and staff. The materials and methods used in the study are then explained, with emphasis given to explaining the innovative data collection method of cartoon annotation. The findings section first presents a content analysis of the cartoons and then considers the four main themes drawn from qualitative analysis of the cartoons and related focus group data. The discussion reflects on the significance of the main findings, and in the conclusion, practical recommendations are developed resting on these.

Differing perspectives on assessment and feedback

Research suggests that students and staff in Higher Education perceive assessment and feedback differently. For example, a number of studies have shown that staff see the feedback they give as better, more useful and fairer than do students (Carless Citation2006; Fletcher et al. Citation2012; Mulliner and Tucker Citation2017). This may reflect staff awareness of processes to ensure quality, such as moderation, which, however, are less visible to students (Fletcher et al. Citation2012). It may also arise from difficulties that students have in interpreting some of the languages used in assessment and feedback (Williams Citation2005). Research has also often suggested that staff unfairly perceive students to only be concerned with marks (Mulliner and Tucker Citation2017). This may be linked to why staff have been found to focus on praise and correcting errors more than offering advice to improve in later assessment tasks (Orsmond and Merry Citation2011). This could also arguably be caused by the way that modularisation acts as a barrier to assessment for learning.

Another fundamental difference in perception is around what counts as assessment. Maclellan (Citation2001) found that students experience assessment as ubiquitous, partly because they consider self-assessment to be important, whereas staff disregard self-assessment and purely focus on formal assessment processes. In fact, neither group’s responses show a full appreciation of the range of principles of good feedback (Di Costa Citation2010). Neither group, in this sense, have full ‘assessment literacy’ (Stiggins Citation1995; Carless and Winstone Citation2020). Students should understand its purposes and processes, understand how to evaluate the quality of work, and know how to act on feedback (Charteris and Thomas Citation2017; Carless and Boud Citation2018). Staff need to have a good grasp of assessment purposes, of appropriate assessment tasks and quality standards, and of how to avoid bias (Stiggins Citation1995; Carless and Winstone Citation2020). On the staff side, gaps in assessment literacy may arise from lack of formal training in the topic and from time pressures (Mellati and Khademi Citation2018).

The most recent large scale, cross-institutional study of differences in views on feedback revealed that, whilst their perspectives do continue to differ, both staff and students have relatively progressive views of the subject (Dawson et al. Citation2019). Both groups see feedback as about improvement, not just about grades. But perspectives did diverge more on what constitutes effective feedback. Staff emphasised design of feedback, timeliness and the linking of feedback from one task to the next. Students emphasised the importance of detailed and specific feedback. Quality of feedback comments was mentioned much less by staff.

Student and staff emotions in higher education

Such differences between students and staff are not confined to cognitive understanding, they also emerge in the domain of emotion, though this has been less researched. Emotion is now recognised as a central aspect of learning for university students and it is acknowledged that they experience a wide range of feelings, from joy and love to anger and fear. Until around 10 years ago, emotion in HE learning was a rather neglected topic of research (Beard, Clegg, and Smith Citation2007; Värlander Citation2008; Zembylas Citation2005). But given the dominance of the notions of constructivism in learning in theory and practice and the growth of interest in the social aspects of learning, it is not surprising that the importance of emotion in learning has become more recognised (Pekrun Citation2019). Current concerns with student well-being and mental good health also imply recognition of the role of emotion in learning (Thorley Citation2017).

Nevertheless, there remain large gaps in research on learning emotions, such as about the role of positive emotions, such as pleasure at achievement or a sense of belonging (Beard, Humberstone, and Clayton Citation2014). The emotion specifically around assessment and feedback also remains a relatively neglected topic for research (Shields Citation2015; Alqassab, Strijbos, and Ufer Citation2019). But it is suggested that feedback has a strong effective dimension (Yang and Carless Citation2013; Kluger and DeNisi Citation1996). Ingleton (Citation1999) suggests that the commonest emotions in learning are shame and pride. Wass et al. (Citation2018) emphasise annoyance and frustration. However, Rowe, Fitness, and Wood (Citation2014) found a very wide range of positive and negative student emotions around feedback. Some areas such as exam anxiety and achievement emotions seem better understood than others such as the emotions arising from the social aspect of learning (Rowe, Fitness, and Wood Citation2014). It is agreed that there needs to be recognition of the importance to motivation of emotional aspects of feedback (Pekrun et al. Citation2002) and the emotional response to feedback affects how it is used (Värlander Citation2008). Yang and Carless (Citation2013) point to the need to manage the feedback process to account for students’ emotional responses and many new approaches to feedback recommend a more dialogic approach to giving feedback because it allows emotions to be acknowledged and worked through. Thus, an important aspect of feedback literacy is students’ ability to manage their emotions and staff sensitivity to the affective dimension (Carless and Boud Citation2018; Carless and Winstone Citation2020).

The emotions of university teachers are also an under-researched area, yet staff too experience a wide range of feelings in their role (Hagenauer and Volet Citation2014; Lahtinen Citation2008; Pekrun Citation2019). As Hargreaves (Citation1998) puts it, teaching is an ‘emotional practice’. Teaching could also be seen as a form of emotional labour, where staff work hard to have the emotions deemed appropriate to the professional context (Steinberg Citation2008). Teachers’ emotions around assessment and feedback in particular remain under-researched. One study found that university teachers find assessment to be emotionally challenging (Stough and Emmer Citation1998). It is understood that students feel stress around assessment, e.g., exam stress, but it is less recognised that teachers also feel stress around assessment and feedback especially anticipating problems from low achievers and from high achievers who might get less good mark than expected (Stough and Emmer Citation1998). Emotion is social, because it is linked to student behaviour and performance. Hagenauer and Volet (Citation2014) found that in terms of negative emotions, annoyance and insecurity were the main ones: they did not find the anger found in studies of school teachers. The authors found that joy and satisfaction were the main positive feelings.

Materials and methods

Visual methods

There is increasing interest in visual and arts-based methods in research in social science (Rose Citation2016; Pink, Citation2001) and in education, in particular (Moss and Pini Citation2016; Prosser Citation2007; Metcalfe and Blanco Citation2019; Mulvihill and Swaminathan Citation2019). They encompass a wide range of techniques – mostly data collection methods – such as photoelicitation in interviews (Kahu and Picton Citation2020; Bates, Kaye, and McCann Citation2019), the analysis of found images (e.g., of visual representations on web sites) and researcher initiated drawing or graphical tasks to elicit data (Brown and Wang Citation2013), including photovoice (Cheng and Chan Citation2020). They are usually combined with more traditional methods such as interviews or focus groups.

There are a number of reasons why researchers see value in visual methods. As non-textual forms of communication, they have potential to unlock alternative aspects of experience from those we are used to talking or writing about. This might mean people reveal more or different levels of experience (Kearney and Hyle Citation2004). Visual methods can help participants express complex ideas (Copeland and Agosto Citation2012). Kearney and Hyle (Citation2004) found asking participants to draw to be an effective way to elicit emotion and that elicited a concise expression of experiences. Visual methods are also good for research with particular groups such as children and others that find it hard to articulate their thoughts or feelings orally or writing (Sewell Citation2011). Depending on the topic, they may be particularly appropriate, e.g. map drawing when investigating spatial practices. They may simply be more engaging and help establish rapport between participants and the researcher. They also have benefits for data analysis and dissemination, in terms of potential impact.

However, visual methods do pose challenges. In particular, there is a question about what the data are and how they should be analysed. There needs to be a choice made between analysis of the images themselves (e.g. through image-based analytic theories such as semiotics) or primarily through analysis of the more traditional data such as interviews elicited with the images. It is critical – as with any data collection – how the task is framed to what the data will be and what kind of interpretation can be made of it (Kearney and Hyle Citation2004).

Drawing has had some, but rather limited use in Higher Educational research (Everett Citation2019; (Brown and Wang Citation2013). It has also been used as a means of eliciting student evaluation of teaching (Mckenzie, Sheely, and Trigwell Citation1998). Drawing or ‘graphic’ methods share the challenges of all visual methods, but an additional issue is that they rely to some degree on drawing skills. Particularly in professional contexts, the participant may be embarrassed by the quality of their drawing, damaging the trust of participants in the research process. This could also raise questions about the value of gathering data through a medium that is unfamiliar or participants unskilled at communicating in.

Participants, data collection and analysis

In the current research, the method chosen was to ask participants to annotate cartoons combined with a more traditional focus group interview. The value of cartoons has been recognised for involving participants in co-production of research analysis (Darnhofer Citation2018) and disseminating results by Bartlett (Citation2013), but it has not been much used for data collection. Our approach was to offer a wide range of templates that the participants annotated, rather than expecting them to draw the whole cartoon. This arguably might make the data less rich than a hand drawing; however, it also made less demands on participants in terms of skills. It enabled them to capture a number of key incidents, rather than spending a lot of time on a single drawing. The resulting cartoons might also be easier to interpret because the textual annotations effectively explain the intended meaning.

Twenty cartoon templates were created using Storyboardthat, online storyboarding software. These simple templates featured single or multiple characters, suggesting in a very broad way different experiences or interactions. They included empty speech bubbles that participants could fill out. The templates also had a space to write an explanation of what had been drawn. Prior to the focus group interview, participants were given 10 minutes to work individually on annotating print outs of the cartoons with the instruction that:

We would like to invite you to visually present your views around assessment and feedback using cartoon templates in front of you. You can use these templates to describe your experience by adding backgrounds and text description, adding more figures. You can draw your own cartoons if you wish.

This had the additional benefit of prompting participants to reflect on the issues prior to the focus group discussion, as well as capturing their individual thoughts separately from the group transcription. Unlike in the semi-structured questions in the following focus groups, participants could pick any topic they wanted around assessment and feedback.

Focus group participants were drawn from two academic departments within the Faculty of Social Sciences at [anonymised institution] in the summer after all assessment had taken place. Email announcements were sued to recruit students and staff participants. Seven focus groups were held with four to five participants in each. Students were selected to represent a range of levels of study and home and international origins. Staff were selected to represent a range of roles involved in the assessment and feedback process, including academics, teaching assistants, and professional service staff. Two focus groups included staff from each department; the other five focus groups were for students. Participants included students (n = 21) and staff (11) in various roles and backgrounds, including home students (n = 10), international students (n = 11), female students (n = 9), male students (n = 12), UG students (n = 12), PGT students (n = 9), female staff (n = 9), male staff (n = 2), academics (n = 4), teaching assistants (n = 5) and professional service staff (n = 2). Thus, students were selected to represent a range of levels of study and home and international origins. Staff were selected to represent a range of roles, including academics, teaching assistants and professional services members. Two focus groups included staff from each department; the other five focus groups were for students. Focus group questions were organised around four topics: the meaning of assessment, pre-submission, the marking period and feedback. Each focus group lasted approximately an hour.

The approach to analysis was twofold. The cartoons were first analysed through content analysis. Cartoons were classified by theme and emotions informed by Plutchik’s wheel of emotions (Citation1980). Emotions were further categorised into two spectrums, positive and negative (Nogueira et al. Citation2015; Pekrun et al. Citation2007). The quantitative data arising from this content analysis were analysed and visualised using SPSS. This allowed us to offer a quantitative overview of the cartoon data. The second round of data analysis was more qualitative with a thematic analysis of the focus group interview data and cartoons being combined, with the main emphasis in our presentation below being on the cartoon data (Braun and Clarke Citation2006). Although such an analysis could be deemed subjective, personal knowledge of the institution and its practices helped ensure that our interpretation can be seen as reliable. Participants were asked to explain their cartoons and so again our interpretation can be deemed reliable. This paper mainly focuses on the visual data supported by evidence from the focus group interviews. In the following analysis, what student and staff participants said in the focus groups are referred to as the ‘focus group’ data and although the cartoons were also collected during the focus groups, they are referred to as ‘the cartoons’.

Results: overview of the cartoon data

A total of 187 cartoons were collected, of which 136 were valid, i.e. relevant to assessment and feedback. Of all the valid cartoons, 80 cartoons were created by students and 56 by staff, an average of four cartoons per participant. One student assembled narrative storyboards across multiple cartoons and two staff drew their own cartoons in addition to the templates provided for them. The majority of participants, however, used the individual cartoon templates to illustrate their feelings and experiences.

Fourteen themes around assessment and feedback and 17 types of emotions in relation to them were identified in the cartoons through coding the cartoons and participant annotations as can be seen in . In addition, the number of cartoons associated with each type of emotion is presented in . The most frequently mentioned five themes around assessment and feedback among all participants were as follows: Clarity on how marks are allocated and feedback (26), student preparation for assessment (19), group work as an assessment method (16), clarity on assessment brief (14) and Grade (14). Emotions of students and staff around the first four themes were overwhelmingly negative (see ), whilst in contrast, emotions around grade tend to be positive (related to joy). Some activities typically attracted one emotion (e.g. grade), whilst other attracted a wide range of emotions, e.g. clarity of mark allocation.

What is striking is the wide range of emotions, at least of negative emotion experienced (). Joy was the commonest positive emotion for both groups. Confusion seemed to be very much the dominant negative emotion for students, with some disapproval and sadness. For staff, there seemed to be a mix of frequently felt negative emotions such as anger, frustration, confusion and disapproval.

Overall, the feeling around assessment and feedback for both students and staff tended to be negative (). Of 80 student cartoons, 59 were negative (74%). Similarly, of 56 staff cartoons, 41 were negative (73%).

The following charts () show the different activities around assessment and feedback (organised in the order they happen chronologically) with the associated feelings attached to them, broken down between students and staff (), and further differentiating positive and negative feeling (). Positive emotions for both groups cluster around the grade; negative feelings cluster around the clarity of the brief, the assessment preparation process, and the clarity of mark (for students) and the marking process, mark allocation and unfair means for staff. The charts visually display the difference in emotion around different elements of assessment and feedback between students and staff.

Figure 4. Activities and emotions among students and staff differentiating positive and negative feelings

This quantitative analysis of the cartoons gives a sense of the overall wide range of emotions among both students and staff, although for both groups the main feelings were negative. The following sections explore some of these patterns in more depth and draw more on themes from the focus group interview data.

Results: emerging themes

Shared emotions between students and staff

Despite the difference in student and staff emotions around assessment and feedback, one result that was striking from the cartoon data was a parallelism in some of the experiences, with both staff and students picking the same templates to talk about parallel emotions. On the positive side, both students and staff felt a sense of joy at completing their respective tasks: preparing the assignment and marking it (). On the negative side, some student cartoons showed a sense of the considerable effort going into assignments, whilst, in parallel, staff felt that their work around assessment and feedback was rather onerous (). The staff cartoon in conveys a sense of staff weighed down by the bureaucracy around marking, even though some of these processes were central to making the process fair, such as moderation. shows common feelings among staff towards marking and explores the dilemma between the need to get the marking done in a timely way and giving high-quality feedback.

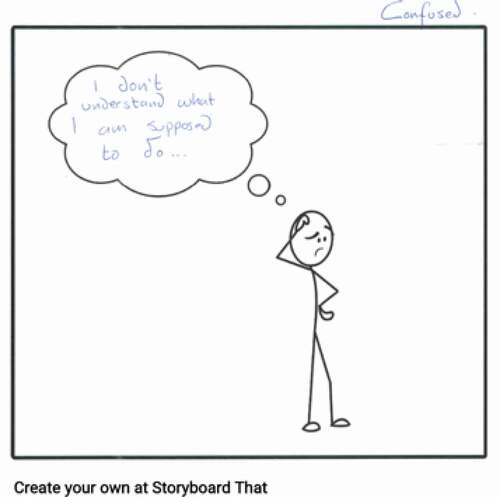

Student feelings of uncertainty

One of the main student emotions around assessment and feedback revealed by the cartoons was uncertainty. For example, there were a large number of cartoons reflecting confusion because of the lack of clarity of the assignment brief (). Student cartoons also suggested that feedback was sometimes unclear. One cartoon reflected dissatisfaction with lack of timely feedback to improve future performance – another the uncertainty created by the late release of marks. It is significant to observe that all these student cartoons implicitly suggest a strong engagement with the assessment task.

Further understanding of this comes from the focus group data.

I don’t understand why for some courses (modules) the coursework is already there when the course starts, but for others, why do they release the assignment in the middle of the semester like week six (Student)

Sometimes it is hard to find the guidelines because they may be in different folders … especially if there are a lot of folders in that module (Student)

Some of the briefs at some modules are a bit vague, and you do have to spend quite a while to see what it means, so, I think there is like a level of clarity that would be optimal (Student)

Thus, students become aware of significant differences in assessment tasks and expectations across modules on the same course, such as

what the assessment task was,

when the task was released,

whether there were examples of previous years,

what the criteria were,

how the task related to the module as a whole.

Staff recognised that students were unclear though they usually emphasised just lack of understanding of the mark given. They were puzzled by student failure to read the assessment brief provided for them.

During the group tutorial, a lot of the questions are about the assessment and module outline. I just tell them to read the module outline but they never do, it is probably too detailed. I don’t think they read it in that detail, they prefer to go and chat with someone about deadlines and everything like that […] (Staff)

One explanation of this confusion might have been that because of modularisation, staff were not as conscious that the range of tasks and style of briefs across a degree programme was quite large.

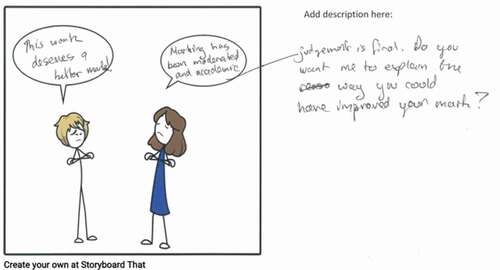

Students also compared marks with each other. A number of cartoons showed students discussing marks. They wanted to know roughly how they did against their cohort (e.g. if everyone had got low marks, they would not feel so bad). However, staff did not approve of students comparing marks, emphasising learning rather than comparison. Some staff believed that students comparing marks with each other could lead students to challenge academic judgment. Staff also thought that students showed aggressiveness/anger towards staff as a result, whereas students themselves mostly just expressed anxiety, at least in the cartoons. There seemed to be some evidence in the focus group interviews that students were frustrated by a lack of a clear procedure to appeal about marks.

Lack of dialogue

One of the main mismatches apparent in the focus groups was that whereas staff considered that students only cared about marks, in fact, most students were interested in learning and understood the point of feedback.

Not just telling them what they did wrong with that but pointing out to improve that to get a better mark (Student)

Staff consider that students are mark-oriented and this impacts the pattern of their engagement. If a lecture or an activity does not contribute to their final mark, staff thought that students do not typically engage.

Sometimes there is only the mark and they just want to pass, and it is just the outcome, the numerical thing that they get (Staff)

It is possible that this staff belief could explain another result from both sets of data: the lack of dialogue between staff and students. If staff think that students only care about the mark, there is no real need for a dialogue around feedback.

What was apparent in the cartoon data was that there was little sense of dialogue between students and staff in the cartoons. It was notable that among 136 student cartoons, there was not a single one illustrating student and staff communication – indeed staff do not appear in the student cartoons at all. Communications in student cartoons were exclusively between students rather than student to staff ().

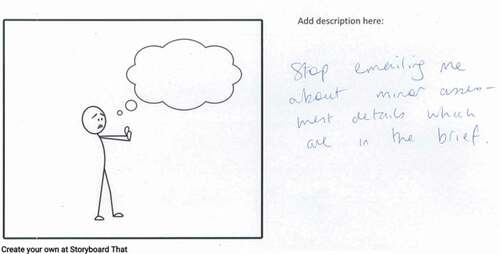

The focus group data also indicated a significant mismatch in terms of students wanting to ask questions about assignment brief interactively, whereas staff thought that the coursework brief should be enough. Indeed, some were suspicious that student questions sought to create ambiguity that they could exploit.

They are playing off the TAs against each other or against the module coordinator that is what they do (Staff)

Staff felt frustrated by attempts to communicate with them for clarification, when they believed everything was in the assignment brief ().

Staff cartoons did picture students and staff together, but it was generally in images of conflict. shows both figures stubbornly defending their position.

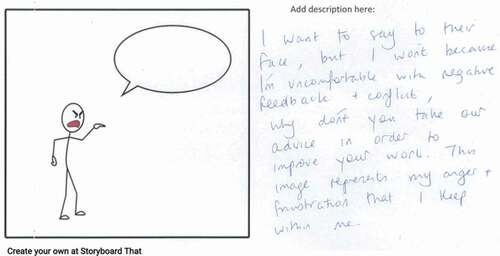

Another reason for failure of communication seemed to be staff avoiding communication because of fear of conflict, as illustrated in .

Staff were worried that students would be angry with them over their grade, especially if they got together and discussed their marks.

Lack of student understanding of backroom processes and roles

A major finding of the focus group data was that students often did not understand many of the backroom processes – such as turnaround deadlines, moderation and anonymous marking – and roles around assessment and feedback – such as exam officer and unfair means officer. Staff expected that students should learn about them from the student handbook. However, the focus group data suggested strongly that most students were unclear about many of these processes and roles. This is a critical failure because many of the processes that students did not understand such as anonymous marking and moderation exist to ensure fairness.

I heard that they moderate the grade, but I feel that I know nothing about this process (Student)

They were not aware of the term anonymous marking, for example. They approved of the idea when it was explained, although they pointed out that some courses are too small for it to work. Staff thought that students may know about anonymous marking but usually ignore it. Perhaps, this points to a failure to convey the benefits of anonymous marking.

They just ignore it, I don’t think they understand the concept, because you find it notice it but they put their names on (Staff)

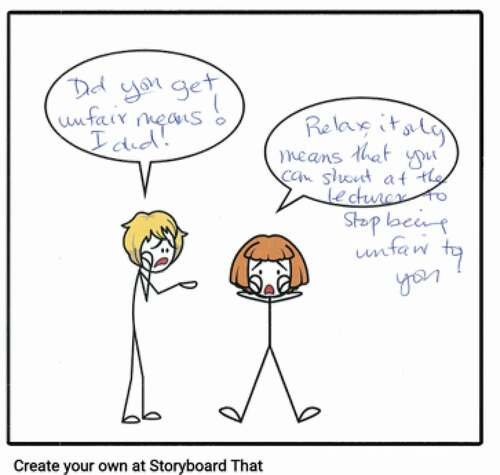

Just as they were unclear about backroom processes, the focus groups also revealed that students had not heard of the role of exam officer or unfair means officer. A staff belief that students did not understand some terms such as unfair means was also apparent in the cartoons. They thought that ‘unfair means’ was sometimes interpreted as a process of checking that marking had not been unfair ().

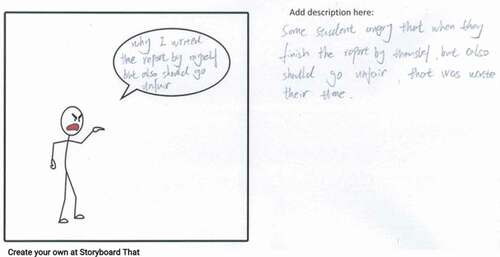

Staff felt suspicious of some student work, because of the difficulties of detecting unfair means. This might have fed into a sense that students did not respect the process of assessment ().

Discussion

Our study supports previous literature that suggests differing perspectives on assessment and feedback between staff and students, in terms of both understanding and with a central emphasis here on emotion. The finding of the sheer range of emotions for students and staff around assessment and feedback supports previous work, such as Rowe, Fitness, and Wood (Citation2014). Our research also suggests that staff have strong feelings and a wide range of emotions about assessment and feedback. The range and level of emotion may be comparable between the two groups, even if the actual feelings are not the same.

However, disappointingly, given that most of the feelings around learning are positive (Pekrun Citation2019), the emotion around assessment and feedback was distinctly more negative than positive in both groups. This may not imply that the overall experience is negative: for the student much may turn on a successful outcome, even if anxieties around the preparation dominate reflections on the process. There is a narrower range of positive emotions around successful results for students and completion of the task of marking by students and staff, confirming the literature’s focus on this negativity and contrary to Beard, Humberstone, and Clayton (Citation2014) suggestion to focus more on positive emotions. Interestingly, unlike Hagenauer and Volet (Citation2014), the findings show that anger did seem to figure in both sets of views.

The literature suggests that staff with good assessment literacy should be sensitive to student emotions (Carless and Winstone Citation2020). However, our data highlight the need to support staff emotions as well because it was evident that assessment and feedback involved considerable emotional labour for staff. This was apparent in the sense of the burden of marking, for example. The burden was perceived to be created by time pressure and bureaucracy. Staff emotion seemed to be linked to lack of communication. Although the literature generally points to the value of dialogue, precisely in order to accommodate student emotional responses to assessment (Mulliner and Tucker Citation2017), staff avoided communication with students during the assessment process, partly because they expected conflictual emotions from students. This supports the general finding that feedback processes tend to be one-way rather than dialogic (West and Turner Citation2016; Yang and Carless Citation2013). Staff often attributed anger to students, when it seemed that the emotion students chiefly expressed was anxiety or frustration. A particular concern seemed to be around students gathering together to discuss and then later dispute marks. This was doubly unfortunate because the data from students suggested considerable ongoing uncertainty about many aspects of the assessment tasks that greater dialogue could have helped address. The uncertainty was partly due to very different expectations between different modules.

There was an interesting sense of parallelism between the emotions felt through the process of assessment and feedback. Both found most of the process challenging, but they shared a common sense of joy at the completion of the process.

At a cognitive rather than emotional level, our data also reveal differences around understanding of terminology, such as unfair means and moderation. Perhaps some of the wider differences of understanding remarked on in the literature do result from lack of awareness of some of the behind-the-scenes activities such as moderation that make staff feel that their marking is fair. The jargon used in HE like ‘moderation’ and ‘unfair means’ is not easy to understand. In this sense, students lack elements of assessment literacy related to a full understanding of the processes involved (Charteris and Thomas Citation2017).

From a methodological perspective, it is apparent that cartoons are an effective way to elicit information about learning experiences, especially their emotional aspects. They also helped reveal hidden assumptions and patterns, such as the way they uncovered the lack of dialogue. A lot can be inferred by what is assumed in annotations. This responds to the need to further enrich the range of methods used to study emotion in learning (Lindblom-Ylänne Citation2019). In many studies based on drawing techniques, a central issue is participants’ lack of confidence with drawing. The approach here of offering templates was effective in overcoming the issue. As a way of enhancing focus group interviews, cartoon annotation is a research method that generates rich data.

Conclusion and recommendations

This paper explored the differences in how students and staff think and feel about assessment and feedback in Higher Education. The study confirmed the wide range of emotions felt by both groups but suggested that the most frequently occurring emotions are negative. There was an interesting parallelism in experience. However, a major finding was that staff often avoided communication with students because of fear of conflict. Yet such dialogue would have been useful because students were unsure about many aspects of assignments and did not understand many of the processes that were in place to ensure fairness.

This is by no means the first study to identify the strength of student and staff emotion around assessment and feedback. Nevertheless, we suggest that this is an aspect that needs greater recognition at the level of practice. Staff need to show empathy with students’ emotional journeys in learning. Perhaps, a way into this is revealed by our findings theme that the journey is to some extent a shared one. However, our data suggest several areas where staff misunderstand student feelings. Some of the misunderstanding may arise from lack of dialogue, an important theme in the data. But the lack of dialogue is itself created by staff feeling and a desire to avoid conflict and suspicions around unfair means, amongst other factors. They should potentially also be seen as arising from the long-term impact of managerialism and massification, leading to a certain level of staff alienation, not merely a personal breakdown in communication.

Student negativity around assessment and feedback can be addressed not just at an emotional level: a lot of the processes and roles around feedback were not understood by students, partly because of the jargon such as ‘moderation’ or ‘exams officer’, which do not have an obvious meaning. The theme of student understanding of backroom processes is of great importance. Staff may feel at times that these are bureaucratic processes; it is easy to forget their role in ensuring fairness. Explaining these concepts is hard. Student handbooks where they are usually explained are often couched in bureaucratic, almost legalistic terms. More effort is needed to explain these processes in a direct way focussing on what they contribute to a just assessment regime rather than emphasising the minutiae of rules and regulations.

Students were far from passive, but there was a lack of two-way communication around assessment and feedback. However, what appears strongly is how the strength of emotion throughout the assessment process (not just at the point of feedback) and on both sides, for staff and students, makes the management of the affective dimension so challenging. There is already a strong sense of emotional labour for staff. How far is it possible for staff to help manage student emotions when their own are rather challenged? We can suggest that this reflects the structural pressures on staff in mass education systems. In this context, focussing purely on literacies can only take us so far. There seemed to be evidence of a literacy deficit, but the breakdown may be created more by structures rather than skills. This demands action at the institutional and system-wide level.

This study was of a single institution and so extending it to different sorts of institutional settings would be useful to validate the findings and the value of the method. The data collection was performed by staff involved in teaching the participating students, which is considered a limitation. This might have inhibited the expression of certain sorts of emotion. Larger-scale studies using the method will enable more generalisable conclusions about the misalignments of student and staff understanding and enable improvements to be made.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Xin Zhao

Xin Zhao is a university teacher in the Information School, University of Sheffield.

Andrew Cox

Andrew Cox is a senior lecturer in the Information School, University of Sheffield.

Ally Lu

Ally Lu is a university teacher in the Department of Urban Studies and Planning, University of Sheffield

Anas Alsuhaibani

Anas Alsuhaibani is a Ph.D. candidate and a member of the Digital Societies Research Group in the Information School, University of Sheffield.

References

- Alqassab, M., J.-W. Strijbos, and S. Ufer. 2019. “Preservice Mathematics Teachers’ Beliefs about Peer Feedback, Perceptions of Their Peer Feedback Message, and Emotions as Predictors of Peer Feedback Accuracy and Comprehension of the Learning Task.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 44 (1): 139–154. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2018.1485012.

- Bartlett, R. 2013. “Playing with Meaning: Using Cartoons to Disseminate Research Findings.” Qualitative Research 13 (2): 214–227. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794112451037.

- Bates, E. A., L. K. Kaye, and J. J. McCann. 2019. “A Snapshot of the Student Experience: Exploring Student Satisfaction through the Use of Photographic Elicitation.” Journal of Further and Higher Education 43 (3): 291–304. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2017.1359507.

- Beard, C., B. Humberstone, and B. Clayton. 2014. “Positive Emotions: Passionate Scholarship and Student Transformation.” Teaching in Higher Education 19 (6): 630–643. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2014.901950.

- Beard, C., S. Clegg, and K. Smith. 2007. “Acknowledging the Affective in Higher Education.” British Educational Research Journal 33 (2): 235–252. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01411920701208415.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101. doi:https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Brown, G. T., and Z. Wang. 2013. “Illustrating Assessment: How Hong Kong University Students Conceive of the Purposes of Assessment.” Studies in Higher Education 38 (7): 1037–1057. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2011.616955.

- Carless, D. 2006. “Differing Perceptions in the Feedback Process.” Studies in Higher Education 31 (2): 219–233. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070600572132.

- Carless, D., and D. Boud. 2018. “The Development of Student Feedback Literacy: Enabling Uptake of Feedback.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 43 (8): 1315–1325. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2018.1463354.

- Carless, D., and N. Winstone. 2020. “Teacher Feedback Literacy and Its Interplay with Student Feedback Literacy.” Teaching in Higher Education 1–14. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2020.1782372.

- Charteris, J., and E. Thomas. 2017. “Uncovering ‘Unwelcome Truths’ through Student Voice: Teacher Inquiry into Agency and Student Assessment Literacy.” Teaching Education 28 (2): 162–177. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10476210.2016.1229291.

- Cheng, M. W., and C. K. Chan. 2020. “‘Invisible in a Visible Role’: A Photovoice Study Exploring the Struggles of New Resident Assistants.” Journal of Further and Higher Education 1–16. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2020.1812547.

- Copeland, A. J., and D. E. Agosto. 2012. “Diagrams and Relational Maps: The Use of Graphic Elicitation Techniques with Interviewing for Data Collection, Analysis, and Display.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 11 (5): 513–533. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/160940691201100501.

- Darnhofer, I. 2018. “Using Comic-style Posters for Engaging Participants and for Promoting Researcher Reflexivity.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 17 (1). doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406918804716.

- Dawson, P., M. Henderson, P. Mahoney, M. Phillips, T. Ryan, D. Boud, and E. Molloy. 2019. “What Makes for Effective Feedback: Staff and Student Perspectives.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 44 (1): 25–36. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2018.1467877.

- Di Costa, N. 2010. “Feedback on Feedback: Student and Academic Perceptions, Expectations and Practices within an Undergraduate Pharmacy Course.” ATN Assessment Conference, 18–19, Sydney: University of Technology, November.

- Everett, M. C. 2019. “Using Student Drawings to Understand the First-year Experience.” Journal of College Student Retention: Research, Theory & Practice 21 (2): 202–220. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1521025117696824.

- Fletcher, R. B., L. H. Meyer, H. Anderson, P. Johnston, and M. Rees. 2012. “Faculty and Students Conceptions of Assessment in Higher Education.” Higher Education 64 (1): 119–133. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-011-9484-1.

- Hagenauer, G., and S. Volet. 2014. “‘I Don’t Think I Could, You Know, Just Teach without Any Emotion’: Exploring the Nature and Origin of University Teachers’ Emotions.” Research Papers in Education 29 (2): 240–262. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02671522.2012.754929.

- Hargreaves, A. 1998. “The Emotional Practice of Teaching.” Teaching and Teacher Education 14 (8): 835–854. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0742-051X(98)00025-0.

- Ingleton, C. 1999. “Emotion in Learning: A Neglected Dynamic.” HERDSA annual international conference, Melbourne, July, 12–15.

- Kahu, E. R., and C. Picton. 2020. “Using Photo Elicitation to Understand First-year Student Experiences: Student Metaphors of Life, University and Learning.” Active Learning in Higher Education. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1469787420908384.

- Kearney, K. S., and A. E. Hyle. 2004. “Drawing Out Emotions: The Use of Participant-produced Drawings in Qualitative Inquiry.” Qualitative Research 4 (3): 361–382. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794104047234.

- Kluger, A. N., and A. DeNisi. 1996. “The Effects of Feedback Interventions on Performance: A Historical Review, A Meta-analysis, and A Preliminary Feedback Intervention Theory.” Psychological Bulletin 119 (2): 254–284. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.119.2.254.

- Lahtinen, A. M. 2008. “University Teachers’ Views on the Distressing Elements of Pedagogical Interaction.” Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research 52 (5): 481–493. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00313830802346363.

- Lindblom-Ylänne, S. 2019. “Research on Academic Emotions Requires a Rich Variety of Research Methods.” Studies in Higher Education 44 (10): 1803–1805. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2019.1665333.

- Maclellan, E. 2001. “Assessment for Learning: The Differing Perceptions of Tutors and Students.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 26 (4): 307–318. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02602930120063466.

- Mckenzie, J., S. Sheely, and K. Trigwell. 1998. “Drawing on Experience: An Holistic Approach to Student Evaluation of Courses.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 23 (2): 153–164. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/0260293980230204.

- Mellati, M., and M. Khademi. 2018. “Exploring Teachers’ Assessment Literacy: Impact on Learners’ Writing Achievements and Implications for Teacher Development.” Australian Journal of Teacher Education 43 (6): 1. doi:https://doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2018v43n6.1.

- Metcalfe, A. S., and G. L. Blanco. 2019. “Visual Research Methods for the Study of Higher Education Organizations.” In Higher Education: Handbook of Theory and Research, edited by Michael B. Paulsen and Laura W. Perna, 153–202. Cham: Springer.

- Molloy, E., D. Boud, and M. Henderson. 2020. “Developing a Learning-centred Framework for Feedback Literacy.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 45 (4): 527–540. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2019.1667955.

- Moss, J., and B. Pini. 2016. “Introduction.” In Visual Research Methods in Educational Research, edited by J. Moss and B. Pini, 1–11. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Mulliner, E., and M. Tucker. 2017. “Feedback on Feedback Practice: Perceptions of Students and Academics.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 42 (2): 266–288. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2015.1103365.

- Mulvihill, T. M., and R. Swaminathan. 2019. Arts-based Educational Research and Qualitative Inquiry: Walking the Path. London: Routledge.

- Nogueira, P. A., R. Rodrigues, E. Oliveira, and L. E. Nacke. 2015. “Modelling Human Emotion in Interactive Environments: Physiological Ensemble and Grounded Approaches for Synthetic Agents.” Web Intelligence 13 (3): 195–214. doi:https://doi.org/10.3233/WEB-150321.

- Office for Students. 2019. “Student Satisfaction Rises but Universities Should Do More to Improve Feedback.” https://www.officeforstudents.org.uk/news-blog-and-events/press-and-media/student-satisfaction-rises-but-universities-should-do-more-to-improve-feedback/

- Orsmond, P., and S. Merry. 2011. “Feedback Alignment: Effective and Ineffective Links between Tutors’ and Students’ Understanding of Coursework Feedback.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 36 (2): 125–136. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02602930903201651.

- Pekrun, R., A. C. Frenzel, T. Goetz, and R. P. Perry. 2007. “Chapter 2 - the Control-Value Theory of Achievement Emotions: An Integrative Approach to Emotions in Education.” In Educational Psychology, edited by P. A. Schutz and E. Pekrun, 13–36. Amsterdam: Academic Press.

- Pekrun, R. 2019. “Inquiry on Emotions in Higher Education: Progress and Open Problems.” Studies in Higher Education 44 (10): 1806–1811. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S1096-7516(00)00016-6.

- Pekrun, R., T. Goetz, W. Titz, and R. P. Perry. 2002. “Academic Emotions in Students’ Self-regulated Learning and Achievement: A Program of Qualitative and Quantitative Research.” Emotion in Education 37 (2): 91–105. doi:https://doi.org/10.1207/S15326985EP3702_4.

- Pink, S. 2001. Doing Visual Ethnography. London: Sage.

- Plutchik, R. 1980. “A General Psychoevolutionary Theory of Emotion.” In Theories of Emotion, 3–33. Amsterdam: Academic press. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-558701-3.50007-7.

- Prosser, J. 2007. “Visual Methods and the Visual Culture of Schools.” Visual Studies 22 (1): 13–30. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14725860601167143.

- Rose, G. 2016. Visual Methodologies: An Introduction to Researching with Visual Materials. London: Sage.

- Rowe, A. D., J. Fitness, and L. N. Wood. 2014. “The Role and Functionality of Emotions in Feedback at University: A Qualitative Study.” The Australian Educational Researcher 41 (3): 283–309. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-013-0135-7.

- Roy, S., C. Beer, and C. Lawson. 2020. “The Importance of Clarity in Written Assessment Instructions.” Journal of Further and Higher Education 44 (2): 143–155. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2018.1526259.

- Sewell, K. 2011. “Researching Sensitive Issues: A Critical Appraisal of ‘Draw-and-write’as a Data Collection Technique in Eliciting Children’s Perceptions.” International Journal of Research & Method in Education 34 (2): 175–191. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1743727X.2011.578820.

- Shields, S. 2015. “‘My Work Is Bleeding’: Exploring Students’ Emotional Responses to First-year Assignment Feedback.” Teaching in Higher Education 20 (6): 614–624. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2015.1052786.

- Steinberg, C. 2008. “Assessment as an ‘Emotional Practice’.” English Teaching: Practice and Critique 7 (3): 42–64.

- Stiggins, R. J. 1995. “Assessment Literacy for the 21st Century.” Phi Delta Kappan 77 (3): 238.

- Stough, L. M., and E. T. Emmer. 1998. “Teachers’ Emotions and Test Feedback.” International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education 11 (2): 341–361. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/095183998236809.

- Thorley, C. 2017. Not by Degrees: Not by Degrees: Improving Student Mental Health in the UK’s Universities. London, UK: IPPR. https://www.ippr.org/research/publications/not-by-degrees

- Värlander, S. 2008. “The Role of Students’ Emotions in Formal Feedback Situations.” Teaching in Higher Education 13 (2): 145–156. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13562510801923195.

- Wass, R., J. Timmermans, T. Harland, and A. McLean. 2018. “Annoyance and Frustration: Emotional Responses to Being Assessed in Higher Education.” Active Learning in Higher Education. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1469787418762462.

- West, J., and W. Turner. 2016. “Enhancing the Assessment Experience: Improving Student Perceptions, Engagement and Understanding Using Online Video Feedback.” Innovations in Education and Teaching International 53 (4): 400–410. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14703297.2014.1003954.

- Williams, K. 2005. “Lecturer and First Year Student (Mis)understandings of Assessment Task verbs:‘Mind the Gap’.” Teaching in Higher Education 10 (2): 157–173. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1356251042000337927.

- Yang, M., and D. Carless. 2013. “The Feedback Triangle and the Enhancement of Dialogic Feedback Processes.” Teaching in Higher Education 18 (3): 285–297. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2012.719154.

- Zembylas, M. 2005. “Beyond Teacher Cognition and Teacher Beliefs: The Value of the Ethnography of Emotions in Teaching.” International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education 18 (4): 465–487. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09518390500137642.