?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

The use of individual tutoring as a method of educational instruction has been prevalent for several decades. One popular tutoring practice is Paired Reading, a reading support technique specifically designed for non-professionals. The accessible nature of Paired Reading makes it an attractive option for schools who wish to capitalise on support offered by community members. This paper reports a multi-faceted evaluation of a Paired Reading programme with primary school children experiencing reading fluency and comprehension difficulties as tutees and university students as volunteer tutors. Tutees engaged in one-on-one reading support sessions with tutors for either 5 or 8 weeks, with each session including 20 min of reading. Although there was no evidence to suggest that Paired Reading improved tutee's reading performance, feedback from tutees and tutors indicated the programme was an extremely positive experience. School staff also welcomed the subjective benefits of the programme. Parents of Paired Reading tutees reported a range of positive observed changes in the reading behaviours and attitudes of their children. This study builds on and contributes to work in the reading support literature, highlighting Paired Reading as a wide-ranging experience offering both tutees and tutors a variety of benefits spanning academic, social, and leisure domains.

Introduction

The use of individual tutoring as a method of educational instruction has been popular worldwide for several decades. Practices incorporating tutoring have been shown to be effective for improving performance on a variety of educational outcomes (e.g. Cohen, Kulik, and Kulik Citation1982; Ritter et al. Citation2009; Wasik and Slavin Citation1993), and have been recognised as a way of efficiently using scarce resources in educational settings. According to Topping (Citation1998), tutoring practices are characterised by a high focus on curriculum content, and specific role-taking (i.e. someone is a tutor while the other(s) act(s) as tutee(s)). Tutoring projects usually have specific procedures for interaction between tutor and tutee, in which both parties have been trained.

Many forms of tutoring practices exist, with many kinds of tutors (peers, parents, community volunteers, or university students). One particularly popular tutoring practice is Paired Reading, a form of additional reading support which has been the focus of extensive evaluation in recent decades (e.g. Brooks Citation2016, Citation2013; Lavan and Talcott Citation2020; Shah-Wundenberg, Wyse, and Chaplain Citation2012; Topping Citation1990). Paired Reading is a reading support technique specifically designed for non-professionals, making it an attractive option for schools and other educational bodies who may wish to capitalise on support offered by local community members.

Paired Reading

Paired Reading is a formalised process entailing a specific and structured technique (see Topping Citation2003), aligning it with the definition of tutoring provided above. In Paired Reading, a tutee and tutor read together, with the aim of improving tutee reading ability. A Paired Reading session begins with Reading Together, where the tutee and tutor read aloud in unison. The tutor modulates their reading pace to match that of the tutee and provides a good model of competent reading. It is important that the text chosen for reading is slightly above the independent readability level of the tutee, but not above that of the tutor. The process of Reading Together continues until the tutee feels confident enough to read aloud independently. The pair agree on a signal for the tutor to stop Reading Together, at which point the tutee reads aloud independently. The tutor corrects all mistakes if they occur (by pointing to the word and saying it aloud), after allowing four seconds for tutee self-correction. If a mistake goes uncorrected by the tutee, the pair returns to Reading Together. Praise is given regularly by the tutor, especially for good reading of difficult words, getting all the words in a sentence right, and self-corrections. Tutors are encouraged to not only sound pleased, but to look pleased.

Paired Reading is thus a straightforward process that accentuates flow, context, and meaning-making. The approach is not centred on the active teaching of words but instead provides opportunities for readers to see reading strategies modelled, with appropriate encouragement and praise. The practice allows readers to read more complex texts in a supportive environment before being required to employ reading strategies and critical thinking independently (Doughtery Stahl Citation2012). It is thought that Paired Reading allows a child to read texts at a higher level of difficulty than they normally could (in line with Vygotsky’s (Citation1978) idea of the zone of proximal development). Several design elements of the Paired Reading process echo the work of Willingham (Citation2015), who describes the three key elements for reading enthusiasm – decoding, comprehension, and motivation. He suggests that reading in 20 min intervals, allowing students choice in selecting what to read, facilitating a sense of community through reading with an adult, and focusing on reading for pleasure are all important factors in supporting reading enthusiasm.

Paired Reading effectiveness

Paired Reading has been evaluated extensively, and has been shown to improve reading performance in a variety of settings, including controlled research settings, and more naturalistic large-scale field trials (e.g. see Topping et al. Citation2012; Topping et al. Citation2011). Topping (Citation1990) evaluated 155 Paired Reading projects across 71 schools, both primary and secondary. Pre–post effect sizes for reading accuracy were 0.87 and for comprehension, were 0.77. The mean pre–post test gain in reading accuracy was 6.97 months of reading age. This was more than three times what might ‘normally’ be expected, if an approximately ‘normal’ expectation may be assumed to be a gain of one month of reading age in one chronological month. The pre–post test gain for reading comprehension was 9.23 months, an increase of more than four times ‘normal’ gains. Importantly, while the practice of Paired Reading can be beneficial for improving reading performance, it has few, if any, negative effects (Topping Citation2014). Paired Reading practice has also been found to be effective on subjective levels, including tutee gains in reading motivation, self-esteem, and improved relationships between tutor and tutee (Monteiro Citation2013; Lam et al. Citation2013). Paired Reading can also be beneficial for tutors (e.g. improved parent–child relationships and self-efficacy reported by parent tutors in Lam et al. (Citation2013)).

Furthermore, the low resource burden of Paired Reading means that it is generally attractive to schools. A meta-analysis by Leung, Marsh, and Cravem (Citation2005) found that short (<30 min) sessions, which occurred at least 3 times a week, displayed larger effect sizes for academic achievement in comparison to other arrangements (although it should be noted that this result refers to peer tutoring for academic achievement outcomes). However, recommendations for intervention duration and intensity are mixed, and others (e.g. Topping et al. Citation2012) found no relationship between intensity of tutoring and progress in attainment.

In the Irish context. The Department of Education and Skills (Citation2019) have endorsed Paired Reading as an effective approach to the teaching of reading. The approach also corresponds to the Reading Association of Ireland's belief that interventions should be responsive to the needs of the learners and be active and engaging (Reading Association of Ireland Citation2011). Research in Ireland has provided further support for the effectiveness of Paired Reading. For example, Nugent (Citation2001) found Paired Reading to be effective with children attending a special school for children with mild general learning difficulties, while Lohan and King (Citation2016) found the approach can be effective with those with social, emotional and behavioural difficulties. Similarly, O Riordan (Citation2013) documented how Paired Reading not only improved reading skill, but also reader self-esteem.

Suas Paired Reading literacy support

Existing research has supported the use of Paired Reading as a method of additional reading instruction. This is important, as literacy support is continually needed around the world, with Ireland being no exception to this trend. Literacy has been identified as an urgent priority for the Irish education system (see the National Strategy to Improve Literacy and Numeracy among Children and Young People [2011–2020]). Several national organisations are working to respond to the call for action issued by this strategy. Suas Educational Development (the word ‘suas’ means ‘up’ in Irish) is one such body, who provide children from disadvantaged communities in Ireland with educational support. One method of support that the Suas Literacy Support programme provides is Paired Reading. The decision to offer Paired Reading is grounded in the ample research base supporting the practice's effectiveness in improving academic achievement, as well as subjective gains reported in the literature by tutors and tutees (both outlined above). The Suas Paired Reading programme operates on a voluntary basis whereby university volunteer tutors are recruited and trained to work with primary/secondary students in weekly Paired Reading sessions. The Suas Paired Reading programme is thus classified as a community-supported literacy intervention. Research examining the effectiveness of tutoring programmes that use non-professional adult volunteer tutors is relatively scant in comparison to that which has examined the use of peers or parents as tutors. Existing research has, however, indicated that participation in tutoring programmes utilising non-professional adult volunteers as tutors can have a positive effect on tutee achievement. In their meta-analysis of 21 studies examining the effectiveness of volunteer tutoring programmes for elementary and middle school students, Ritter et al. (Citation2009) found that programmes did not have to use a particular type of tutor to have positive effects on reading and math outcomes, nor did the programmes have to be highly structured. The use of university students as tutors in the research reported here is thus justified. Indeed, university students may offer unique strengths as tutors e.g. very high literacy levels, interest in and willingness to speak about higher level education, time available to devote to tutoring, and the ability to act as positive role models for tutees.

Suas have undertaken a number of evaluations of their support programmes. In 2018/19, the organisation supported 1273 children with one-to-one reading and maths mentoring in disadvantaged schools. The average reading age of children across the Paired Reading projects in 2018/19 increased by 4 months over the 2-month duration of the project. 65% of children reporting reading more often, 52% of children felt happier to read aloud, and 85% of children agreed they were better at reading (Suas Annual Report, Citation2019).

The current study

This research aimed to conduct a multi-faceted evaluation of the Suas Paired Reading programme as a method of reading support for primary school children experiencing reading difficulties. Although many studies investigate the effect of Paired Reading on reading outcomes or subjective outcomes, this research aimed to take a more holistic approach to ‘improvement’. It examined not only reading performance, but self-reported and observed behaviours and attitudes of tutees. The research also aimed to capture the experience of the tutees and tutors as they engaged in the programme. The research questions were:

How effective is Paired Reading for improving reading outcomes among older primary school children?

Are there any changes in the self-reported reading behaviours and attitudes of the tutees over time?

Do parents and teachers observe any changes in Paired Reading tutee reading behaviours and attitudes?

What is the experience of the tutees and tutors participating in Paired Reading?

Method

Participants

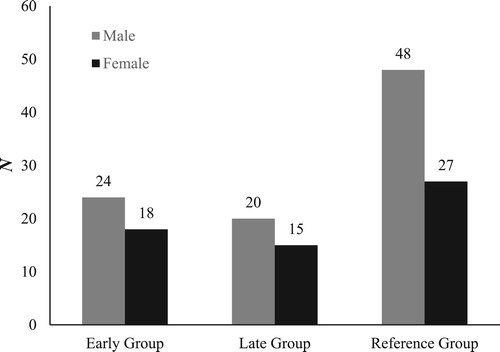

Tutees were 96 primary school children within the 3rd to 6th classes (age range: 8 years, 2 months – 13 years, 5 months). Participants were recruited from four schools in Cork city, Ireland. All schools held DEIS (Delivering Equality of Opportunity in Schools) status, which is applied to schools where a significant proportion of the school population is from a disadvantaged community. Teachers were asked to nominate tutees who they felt needed additional reading instruction, particularly in terms of reading fluency and reading comprehension. Due to the nature of Paired Reading practice (with its focus on modelling, encouragement, and praise as opposed systematic teaching of word decoding skills), teachers were asked to nominate those children who, while in need of reading support, were not extremely weak in word recognition ability.

Although 96 children were invited to participate in Paired Reading, complete data for only 77 of those children were available for analysis, as some parents did not consent to their children participating in the assessments, and some children were absent from school on days when the assessments took place.

Paired Reading tutors were 192 undergraduate students within University College Cork. Most tutors studied within the College of Arts, Celtic Studies, and Social Sciences.

Teachers and parents of Paired Reading tutees also provided reports on changes they had observed in tutee reading behaviours and attitudes.

Design

The study employed a crossover design (see ) whereby Paired Reading tutees were split into two groups; an ‘early Paired Reading’ group (participated in school term 1) and a ‘late Paired Reading’ group (participated in school term 2). Allocation of tutees to either the early or late participation groups was organised by class teachers, who were eager to organise the allocation of children to groups themselves. Teachers were advised to divide students of differing abilities across the two groups as evenly as they could. Specifically, teachers were advised not to group the weakest children in the early participation group as this was noted as a potential trend. A reference group was also drawn from the same classes as children engaging in Paired Reading. Children were included in the reference group if their standard scores on at least two of the three literacy measures described below fell within one standard deviation of the mean, ensuring that those children were performing at an average level.

Intervention procedure

Extensive advertising for student volunteers was completed at the start of the academic year within University College Cork. Volunteers attended a training evening which covered issues such as the rationale behind the Literacy Support programme, child protection, and building the tutee-tutor relationship. Volunteers were briefed on the history of Paired Reading as a practice and the potential benefits of the practice were outlined. Volunteers were taught the practice of Paired Reading through means of an oral presentation and video demonstration. The tutors were instructed to apply the exact procedure recommended by Topping (Citation2003) as described in the previous section, including Reading Together and Reading Alone routines. Tutors received information packs with all the training materials in printed format. Representatives from each participating school also attended the training evening and met with tutors, giving them a sense of the school environment they would be working in. It should be noted that tutor's treatment fidelity was not formally evaluated. Extensive observation would need to take place in person or through the use of audio/visual recordings to facilitate such an evaluation. These resources were unfortunately not available in the context of this study.

The Paired Reading sessions took place twice weekly, with each session lasting for 20 min. Extra time was included in the schedule for tutors and tutees to greet each other and, where appropriate, to choose their reading material. Each tutor read separately with two tutees during their time on school grounds (tutors were on school grounds for a total of one hour). The early Paired Reading group participated in sessions for a total duration of eight weeks. The late Paired Reading group participated in sessions for a total duration of five weeks. This shortened duration was a result of unavoidable logistical and timetabling issues, mainly to do with the amount of time it took volunteers to be vetted. The amount of sessions available to children was decided upon following consultation between Suas and the participating schools. The decision was based on the number of tutors available, and school timetabling considerations. The tutors were bussed to the schools where the Paired Reading sessions took place (usually in a library or sports hall), supervised by a school staff member.

Measures and assessment procedure

Cork Test of Reading Speed

All paired Reading tutees and the reference group completed a group assessment – the Cork Test of Reading Speed (Szczerbinski Citation2011) – at the three time points. The first assessment took place before either group began Paired Reading sessions. The second occurred after the early participation group had finished Paired Reading, and before the late participation group started Paired Reading. The final assessment was completed after the late participation group had finished Paired Reading. The test was group administered in class. It consisted of the following measures. For each, the outcome was the number of correct choices made in the time allotted:

Word recognition

Participants were presented with 35 rows, each containing one real word and two pseudo-words. Their task was to locate the real word in each row and to underline it. They were given 45 s to complete as many rows as possible. Participants completed two trials of this task and a composite score created (maximum available score = 70). Each trial contained different stimuli. Test–retest reliability (based on the correlation between scores at T1 and T2) was 0.90.

Sentence verification

Participants were presented with 30 short sentences, designed to measure reading fluency at the sentence level. Their task was to decide if each sentence was true or false. Participants had 45 s to verify as many sentences as they could. Participants completed two trials of this task and a composite score created (maximum available score = 60). Each trial contained different stimuli. Test–retest reliability was 0.87.

Reading comprehension

Participants were presented with four short texts (average length of 125 words). Two of the texts were narrative and two expository. Within each text there were several word pairs printed in bold. The participant's task was to decide which word in each pair made sense within the context of the story and to underline it. Participants were given two minutes to read as much of the texts as they could. Participants completed two trials of this task (each containing two stories) and a composite score was created. The four texts used in the reading comprehension task changed at every assessment occasion as this task was thought to be susceptible to practice effects (maximum available score: T1 = 56; T2 = 52; T3 = 51). Test–retest reliability was 0.93.

Additional measures

Tutee attitudes towards reading scale

At each of the three time points, tutees were asked to complete a short questionnaire. It consisted of 11 items which were intended as brief, simple indicators of tutee reading behaviours and attitudes towards reading. Two of the items (‘I think I am a good reader’ and ‘I am getting better at reading’) were taken from the Reader Self-Perception Scale (Henk and Melnick Citation1995), while the remaining items were self-developed.

Tutee questionnaire

A short questionnaire for Paired Reading tutees was devised which they completed once, at the end of their Paired Reading sessions. One question was asked about tutee's enjoyment of the project (‘Yes/No’ response format), and one open-ended question concerning aspects of the sessions they liked and did not like was asked. Tutees were also asked about their attitudes towards reading (drawing a smiling, happy, or indifferent face to indicate their agreement or disagreement to three statements about reading).

Teacher questionnaire

A questionnaire was administered to the teachers of Paired Reading tutees. Teachers completed the questionnaire for each child once, at the point when children had finished all of their Paired Reading sessions. All the items bar one were taken from Topping’s (Citation1990) doctoral thesis where a similar evaluation was conducted. It consisted of nine items, and was intended to explore if teachers felt that participation in Paired Reading had produced positive effects in children which affected their reading in the classroom. Questions were asked about attitudes to reading, oral reading skills, and reading comprehension. For each item respondents could choose one of three options: ‘Yes’, ‘No’, or ‘No change’.

Parent questionnaire

A questionnaire was also administered to the parents of Paired Reading tutees. Parents completed the questionnaire for their child once, at the point when the child had finished all of their Paired Reading sessions. Again, all items bar one in the parent questionnaire were taken from Topping’s (Citation1990) doctoral study. It contained six items, and was intended to explore if parents felt that participation in Paired Reading had produced positive effects in their child which had affected the child's reading in the home. Questions were asked about the amount and variety of reading at home, and attitudes to reading. Questions pertaining to oral reading skills and comprehension were not given to parents as, given the older age of children, it was not assumed that children would read aloud for their parents. For each item respondents could choose: ‘Yes’, ‘No’, or ‘No change’.

Tutor questionnaire

An online questionnaire was completed by tutors which they completed once, at the end of their Paired Reading sessions. It sought to assess any changes in attitudes or skills the tutors experienced, and to allow tutors to comment on their experience. It consisted of 27 questions; seven open-ended questions and 20 questions which were answered using a 5-point Likert scale (responses ranged from ‘Strongly Agree’ to ‘Strongly Disagree’).

Staff members responsible for overseeing Paired Reading questionnaire

School staff members responsible for overseeing Paired Reading were also asked by Suas to comment on their experiences of the programme. The online questionnaire consisted of 10 questions; four open-ended questions and six questions answered using a 5-point Likert scale.

Results

Paired reading attendance

Information on the attendance rates of tutees in the early participation group is available for three of the four participating schools, and is presented in .

Table 1. Attendance rates of tutees in the early participation group.

Information on the attendance rates of participants in the late participation group is available for three of the four participating schools, and is presented in .

Table 2. Attendance rates of tutees in the late participation group.

Data preparation and analysis

As the distribution of gender and class was not exactly equal across groups (see ), two Chi-Square Tests for Independence were performed to examine whether that imbalance was statistically significant. The results indicated no significant association between gender and group (χ2 (2) = 0.75, p = 0.69, Cramer's V = 0.07), or class and group (χ2 (6) = 3.00, p = 0.81, Cramer's V = 0.10). Thus, gender and class were not controlled for in subsequent analyses.

During the assessments, it was apparent that some children were frequently guessing their answers. This is problematic, as blind guessing may result in inflated scores. A correction for guessing formula (as cited in Diamond and Evans Citation1973) was applied to the data obtained from the Cork Test of Reading Speed to remedy this problem. Within this formula, . The formula returns an accuracy score corrected for the rate of guessing. It has been argued that the use of this correction increases both the reliability (Mattson Citation1965) and validity (Lord Citation1963) of the test being used.

Descriptive statistical analyses were first conducted on the corrected data, followed by a series of 3×3 mixed between-within subjects analyses of variance (ANOVA), with a within-subject factor of Time (T1, T2, T3), and a between-subjects factor of Group (reference vs. early playing vs. late playing group). In this context, it is the interaction effect that is of greatest interest, as a significant interaction effect is expected if changes across time are different among the groups i.e. there is an effect of the intervention.

As separate ANOVAs were conducted, a more stringent alpha value was utilised to reduce the risk of Type 1 error. With three independent variables, the conventional alpha value of 0.05 was divided by 3, resulting in a value of 0.02. Where significant main effects were observed, post-hoc Bonferroni adjusted multiple comparisons were conducted.

The effect of Paired Reading on literacy outcomes

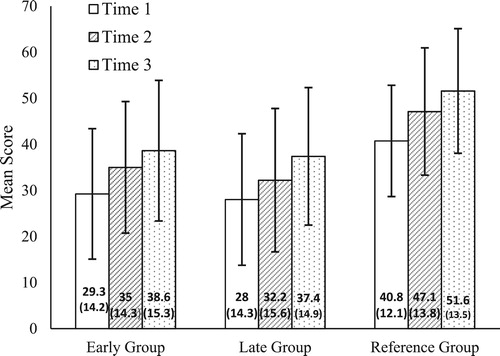

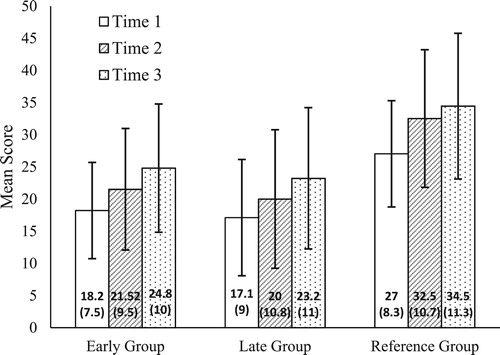

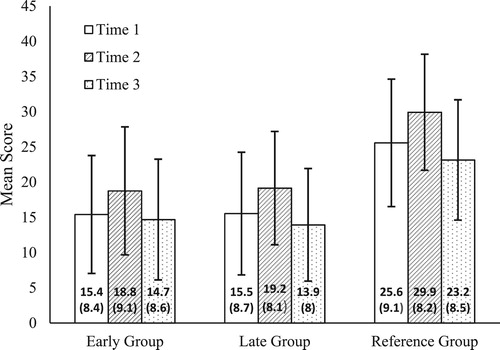

Descriptive statistics for each of the outcome measures are available in .

Figure 2. Mean Scores of Three Groups across Three Time Points on the Word Recognition Task. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

Figure 3. Mean Scores of Three Groups across Three Time Points on the Sentence Verification Task. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

Figure 4. Mean Scores of Three Groups across Three Time Points on the Comprehension Task. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

Descriptively, scores for all three groups increased over time on the word recognition and sentence verification tasks. Performance on the reading comprehension task was the exception, as scores for all three groups increased from T1 to T2, but decreased from T2 to T3.

Across all tasks, there were no statistically significant interaction effects, indicating no obvious effect of the intervention on performance (this was also the case when the traditional alpha level of 0.05 was used). Substantial main effects of Time were observed across all measures, with performance improving significantly from one assessment point to the next (see ). The one exception to this trend was the reading comprehension task, where performance improved significantly from T1 to T2 but then dropped again, with T3 performance being significantly worse than both T1 and T2.

Table 3. Mixed between-within subject analysis of variance: main effect for time summary.

Across the word recognition, sentence verification, and reading comprehension measures, significant main effects of Group were also observed (see ). Post-hoc comparisons revealed that the reference group outperformed both Paired Reading groups, although the latter two did not differ significantly.

Table 4. Mixed between-within subject analysis of variance: main effect for group summary.

Tutee reading behaviours and attitudes towards reading

Of most interest here were the responses from both Paired Reading groups, before and after their participation in Paired Reading. Descriptively, there were marginal positive changes in responses to a number of items across time, for both Paired Reading groups. To systematically investigate differences in questionnaire responses across the three time points, a series of Friedman tests were conducted for the early and late Paired Reading groups, as well as the reference group. An adjusted alpha level was used for the Friedman tests, to reduce the potential for Type 1 error. An adjusted alpha level of 0.007 was utilised (0.05 divided by 7, the number of hypotheses tested within each group). Results indicated no statistically significant differences in any of the responses of either the early or late Paired Reading groups across the three time points.

Parent and teacher feedback

Parental feedback was very positive, with parents reporting a variety of positive changes in children's attitudes towards reading and reading behaviours. According to parents (n = 56), 73% of children were reading more at home and 63% were reading different kinds of books at home. Eighty-four percent were displaying more confidence in reading, while 68% were more willing to read. Seventy-seven percent showed more interest in reading, and 71% exhibited more pleasure in reading.

Teacher feedback was less positive than parental feedback (although it should be noted that most questions given to parents and teachers differed). According to teachers (n = 63), 57% of students were displaying more confidence in reading, 43% were more willing to read, and 52% showed greater pleasure in reading. Thirty-four percent were showing greater reading comprehension, while 37% read with improved reading accuracy. Between 22% and 25% were displaying greater speed, expressiveness, and pacing in their reading.

Tutee feedback: closed response items

Ninety six percent of tutees reported enjoying the Paired Reading sessions. Since participating in Paired Reading, 81% believed they were better at reading, 69% claimed to be reading more often, and 58% were happy to read out loud. The majority of tutees thus reported positive changes in their reading since participating in Paired Reading.

Tutee feedback: open response items

Tutees were asked to write down three things they liked about Paired Reading, and three that they did not like. These data were subjected to Thematic Analysis. The analysis followed the procedure for thematic analysis as described in detail by Braun and Clarke (Citation2006), and was conducted by the first author. Analysis began with verbatim transcription of the data. Active reading and re-reading of the data followed, searching for initial patterns. Initial responses to the text were noted at this stage. Initial responses were translated into initial codes which identified an interesting feature of the data. As much of the text as possible was coded.

The next phase involved a consideration of the relationship between codes. Codes were grouped together to form overarching themes. A review and refinement of the themes followed, ensuring that data within the themes fitted together meaningfully. Finally, themes were named and a narrative account for each produced.

The analysis resulted in the creation of several themes, presented below. Quotes from tutees have been transcribed verbatim. Data from 69 Paired Reading participants (39 from Term 1, and 30 from Term 2) were available for analysis.

Data from the online questionnaire distributed to school staff members responsible for overseeing Paired Reading are also included in the analysis below. Although these data come from different sources, it is thought that the inclusion of both sets of responses generates a clearer sense of how Paired Reading was incorporated into school life, and illustrates how the intervention was responded to by staff and students alike. Quotes from school staff have been included verbatim.

The social aspect

Reading as a shared experience. The manner in which tutees spoke about Paired Reading indicated that, for them, it was an enjoyable social event. Tutees viewed their interactions with their tutors as positive, and comments on tutee-tutor interaction were frequent. The novelty of meeting new people through Paired Reading was acknowledged, as was the enjoyment gained from sharing reading with another person.

Things I liked: I liked reading with new people. (Boy, 3rd class)

Informal, opportunistic conversations with school staff members echoed this point. Many teachers and principals commented on how the benefits of Paired Reading extended beyond potential reading improvements to include the creation of a positive social environment for tutees and tutors. A recurring theme in conversations with staff members centred on the fact that tutors had provided highly positive role models for participants, showing dedication and interest in both education and individual tutees. Also, for many tutees, interaction with tutors was their first introduction to third-level education. The subjective benefits of Paired Reading are echoed in the following quote from a Vice-Principal who provided written feedback to Suas:

There are many qualitative benefits for the children participating. Role models – life-long learning, demystifying college – UCC, enjoyment of books and increased motivation to read for leisure. Overheard child saying ‘I want to go to UCC.’ Children looking forward to it – has become a highlight in the school week.

Assistance as a positive experience. Tutees were keen to acknowledge how much they enjoyed receiving personal assistance from their tutors. Several tutees specifically mentioned their tutors by name, and seemed to relish the personal attention and support they received.

Things I liked: If I got a word wrong they would help me get it write. (Girl, 6th class)

The positive nature of assistance was also noted in the feedback provided by teachers to Suas. For example, one teacher states:

The boys don't very often get a chance to read alone with an adult at school, so we found this the most beneficial … All of the boys enjoyed the experience. They love the one to one attention and they like to work with a ‘new’ person.

Positive reinforcement. Elements of positive reinforcement also seemed to be at play within the tutee-tutor dynamic. Tutors were instructed in their training sessions to provide children with appropriate praise and encouragement. This emphasis within the sessions was recognised and appreciated by the tutees.

Things I liked: When they said I did a good job. (Girl, 4th class)

Reading as an activity

Just reading. Being afforded the space and time to read was a treat for many children, with several tutees content with the simple act of ‘just reading’ Indeed, this is what we may expect from children who have come to enjoy reading as a hobby. Several children described the experience of reading as ‘fun’, accompanying such descriptions with smiling faces.

Things I liked: I liked about suas is that to you could read. (Boy, 5th class)

Materials. The activity of reading is of course closely tied to what one is reading. How much enjoyment participants experienced in the sessions seemed largely linked to the materials they were provided with. Many children referenced specific books or authors when speaking about aspects of the sessions they had enjoyed:

Things I liked: Reading the book of space. (Boy, 3rd class)

The novelty associated with reading a variety of materials, some new, also appears as a source of enjoyment for the tutees:

Things I liked: I read lots of nice books. (Girl, 6th class)

Ownership

Tutee independence. A sense of ownership in Paired Reading, and enjoyment associated therewith, was voiced by a number of tutees. For example, the fact that the sessions afforded children a space in which they could read out loud was deemed enjoyable. The fact that all reading was conducted in a supportive, encouraging environment may have contributed to a sense of comfort for the tutees:

Things I liked: I loved reading out loud. (Girl, 4th class)

Tutees also spoke of the enjoyment they experienced having the freedom to read independently of their tutor:

Things I liked: Reading on my own. (Girl, 5th class)

Indeed, some tutees noted that they did not enjoy the process of reading together with their tutors, preferring independent reading. The balance between reading together and independent reading is obviously dependent on the ability of the child, both in terms of reading skill and confidence to signal for independent reading. These tutee statements raise the question of how well some children are able to navigate this relationship with their tutor, and how this relationship should be managed by the tutor.

Material selection. Tutees appreciated the fact that they had choice in terms of their reading materials. Both the capacity to choose books of personal interest and to continue exploration of another book once finished with the first were documented by tutees:

Things I liked: Reading the things I liked. (Boy, 4th class)

Learning

Engagement in the learning process. Tutees were aware that Paired Reading was a space in which learning happened and seemed happy to be engaged in the learning process. Tutees stated that they enjoyed progressing in the mechanics of reading (e.g. learning new words) but that they also enjoyed engaging in new topics explored in their reading materials:

Things I liked: I liked when I got to learn more words. (Girl, 4th class)

Things I liked: I learned new things. (Boy, 4th class)

Tutees also evidenced awareness of the emphasis placed on reading comprehension in Paired Reading:

Things I liked: Explaining things. (Girl, 3rd class)

On the other hand, there were also a small number of instances where tutees felt they did not have appropriate mastery over their reading material.

Things I did not like: Not understanding. (Boy, 4th class)

As this feedback was gathered after all of the Paired Reading sessions had finished, it is not clear whether this child's lack of understanding was apparent during the sessions. If it had been, alternative texts more fitting to the child's ability should have been offered.

Programme implementation

The design of the Paired Reading programme was such that tutees had two reading sessions a week, each involving a different tutor. These same two tutors were then assigned to work with the tutees every week over the course of the programme. However, logistical issues sometimes meant that tutees read with different tutors over the duration of the programme (e.g. in instances where tutors were unwell and a replacement tutor took over). Comments below indicate that tutees were unhappy about tutor inconsistency, although it is unclear which aspect of inconsistency (tutors changing because of programme design or tutors changing because of unavoidable circumstances) they are referring to:

Things I did not like: When don't have the same helper. (Boy, 3rd class)

Tutees also felt that the Paired Reading sessions were too short and voiced a desire for longer reading sessions:

Things I did not like: It was to fast. (Girl, 3rd class)

Tutor Feedback

Paired Reading tutors completed a questionnaire which included a variety of closed and open-ended questions. Tutors reported very positive experiences, indicating that their tutoring practice had resulted in a range of personal and professional skill improvements. For example, 99% of tutors reported growth in self-confidence, 100% reported improved tutoring abilities, 97% reported improved communication skills, 97% found tutoring to be a positive experience, and 100% felt inspired to volunteer again. Within the questionnaire, tutors were also given the opportunity to share any stories or observations about particular tutees who they believed had benefited from Paired Reading. Eighteen tutors chose to share such stories (a selection of these stories is available in Appendix 1). Also included is a selection of comments taken from the ‘Any other comments?’ section of the questionnaires, where eight tutors responded.

The stories provided by tutors were overwhelmingly positive, and highlighted the positive changes tutors witnessed in tutees over the course of the Paired Reading programme. Several tutors commented on how much they had personally enjoyed tutoring, and voiced a desire to continue volunteer work. One tutor reported a negative comment, describing how the tutee had struggled to engage with the books available to him in Paired Reading.

Discussion

The aim of this research was to evaluate Paired Reading as a method of additional reading support for primary children experiencing reading difficulties. The evaluation was multi-faceted and included an examination of tutee reading performance, tutee reading behaviours and attitudes towards reading, parent and teacher observations of tutee reading attitudes and behaviours, and both tutee and tutor's experiences of participation in the Paired Reading programme. When evaluated across this number of levels, it is possible to appreciate the programme for its successes, and to identify its shortcomings.

Evaluations of tutee reading performance were disappointing, and there was no evidence to suggest that the Paired Reading programme was effective for improving reading outcomes. Similarly, there were no statistically significant changes in tutee self-reported reading behaviours and attitudes across the period of intervention. Considering the brief duration (8 or 5 weeks) and low intensity (two 20 min sessions per week) of the Paired Reading programme, these findings are perhaps unsurprising. Indeed, previous research has suggested that the effects of interventions which focus on skills such as reading fluency and reading comprehension may take some time to emerge (Gunn et al. Citation2002). Here, feedback from tutors and tutees suggested that a number of tutees may have experienced greater interest in reading after participating in Paired Reading. This greater interest may ultimately translate into a larger volume of reading, and increased reading practice. Delayed post-testing would be needed to detect such effects. Furthermore, children in need of additional reading support may learn at slower rates than their typically performing peers, and may also have histories of academic failure. Such children may need more intensive instruction. This is particularly important for interventions such as Paired Reading, where students may learn more gradually through a modelling-based learning approach. Although research has produced mixed findings surrounding the level of intensity required by literacy interventions, it is likely that more intensive support than was offered here is required.

Both parents and teachers reported observing a range of positive changes in Paired Reading tutees. Feedback from parents was particularly positive, and a majority of parents reported that their children were reading more at home, were reading different kinds of books, and were displaying increased confidence, willingness, interest, and pleasure in reading. Feedback from teachers was less positive than that from parents, and across most items, teachers reported that they saw no change in Paired Reading tutees. Teachers did, however, report that over 50% of Paired Reading tutees were showing more confidence and interest in reading after their participation in the programme. Although teacher feedback was somewhat disappointing, it is useful to remember Topping’s (Citation2014) observation that although Paired Reading may not always result in academic improvement, it has few, if any, negative effects.

Feedback from tutees regarding their experience of Paired Reading was overwhelmingly positive, and served to highlight the subjective benefits of tutoring programmes such as Paired Reading. Tutees reported enjoying their time spent with tutors, and relished in the one-to-one attention received. Tutors also found Paired Reading to be a predominantly positive experience. Tutors reported experiencing growth in a range of personal and professional skills, including self-confidence, tutoring skills, communication skills, and commitment to volunteering.

The subjective benefits of the Paired Reading programme are perhaps best attested to by the decision of three of the four participating schools to continue with the programme in the following year, despite tutee's disappointing performance on reading measures. Paired Reading was embraced as more than just an opportunity for reading practice; it was an experience entailing academic, interpersonal, and attitudinal benefits for tutees. From the point of view of remediation, the road to fluent reading skills is long. If the amount of reading activities a child engages in is critical, educators are challenged to design a training environment that is easy to implement day-to-day and which is deemed motivating by children. Furthermore, successful interventions require teams working to ensure user fidelity to the intervention, opportunities to create social learning environments, and strong commitment from those operating at the crux of the intervention. It appears that the challenge from a school's point of view is not to create some exceptional intervention, but rather to incorporate a simple practice into the school day which can operate consistently and systematically given the time, personnel, and space restrictions present within the school. From this point of view, a practice like Paired Reading, which has the potential to benefit both tutees and tutors, may be a highly promising intervention. Qualitative feedback from tutors indicated that many children experienced attitudinal changes towards reading, and on a broader level, education. It is argued that these changes occurred not merely as a result of direct exposure to reading, but exposure to reading in a context that was positive and encouraging, and enabled discussion and reflection between tutor and tutee. If increasing a child's exposure to text is paramount on the road to skilled reading (Share and Stanovich Citation1995; Stanovich and West Citation1989), it is argued that such exposure should occur within a context that is highly social, and teaches the child to consider reading in a positive light where the benefits and pleasures of reading become apparent.

Limitations

This research was a small-scale evaluation of a community based intervention programme. Sample sizes were small, and the results of reading performance reported here may be a reflection of low statistical power. Also, as previously mentioned, the duration of the programme was short, and tutees received only two 20-minute Paired Reading sessions per week. Tutees may simply not have had enough exposure to the practice to evidence objective benefits.

Furthermore, the evaluation reported here was lacking in-process data, and lack of insight into tutor fidelity is a serious limitation. We cannot know if the tutors followed the procedure outlined in their training (Topping Citation2003), and cannot know for sure if the non-significant results reported here are a result of poor tutor fidelity, or a genuine lack of effect. To collect process data, extensive observation would need to take place in person or through the use of audio/visual recordings. Future research should strongly consider these options.

Finally, much of the data were self-reported by participants. Common issues with self-report measures include lack of honesty, image management, lack of introspective ability, lack of understanding, and response bias. It is impossible to know whether such issues were present in this study, but the results reported here may have been influenced by such factors.

Concluding comments

When the Suas Paired Reading programme was evaluated purely in terms of measurable reading performance, we saw disappointing results. However, when the bigger picture was examined, and the multitude of potential benefits are considered, it is possible to appreciate the programme for its successes. To conclude, the advantages of Paired Reading (Topping Citation2014) and the associated positive outcomes evidenced in this evaluation are reiterated:

Children are given a space in which to pursue their own interests in reading material and the sessions increase the amount of reading practice a child receives. This was illustrated through tutor reports which stated that tutees had started to bring books home with them and were reading in the evening.

Paired Reading gives children a flexible amount of support to read their chosen book. Unrecognisable words are provided to children in a supportive and timely manner, and children are frequently praised. Furthermore, expressive and appropriately paced reading is modelled by the tutor. Much evidence of this support was seen as tutees spoke positively of the instruction and support they received from their tutors.

Children have a sense of control in the reading situation. Again, evidence for this is apparent in tutee questionnaire feedback when a sense of ownership in the Paired Reading experience is voiced by tutees.

Reading comprehension is an important focus within Paired Reading, and the practice provides readers with a sense of continuity in reading practice. The focus on reading comprehension within the practice was commented upon by tutees who enjoyed discussing the meaning of their reading material. Tutor feedback also reiterated the progress made by tutees in their understanding.

Paired Reading provides the child with individual attention. This aspect of the programme was well received by tutees and school staff members alike who commented on the enjoyment that one-to-one attention brought the tutees.

Overall, Paired Reading provides an uncomplicated, enjoyable way of assisting children. It avoids children getting confused, worried or frustrated about reading. The overall satisfaction that children displayed with the Paired Reading programme is testament to this idea.

The significance of the fact that Paired Reading is a simple, reasonably inexpensive, and flexible method of additional reading support cannot be overstated. The Paired Reading programme reported here ultimately functioned as a positive collaboration between a university and local school children, and allowed the schools to make efficient use of available support. Within the participating schools, Paired Reading was accepted as a wide-ranging experience, which offered its participants, both tutees and tutors, a variety of benefits spanning academic, social, and leisure domains.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Laura Lee

Dr. Laura Lee is the Research Manager in the Centre for the Integration of Research, Teaching and Learning (CIRTL) at University College Cork. This research was conducted as part of her PhD in Applied Psychology. Dr. Marcin Szczerbinski is a lecturer in psychology, University College Cork.

References

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research 3 (2): 77–101.

- Brooks, G. 2013. What Works for Children and Young People with Literacy Difficulties? The Effectiveness of Intervention Schemes. 4th ed. Bracknell: The Dyslexia-SpLD Trust.

- Brooks, G. 2016. What Works for Children and Young People with Literacy Difficulties? The Effectiveness of Intervention Schemes. 5th ed. The Dyslexia-SpLD Trust.

- Cohen, P. A., J. A. Kulik, and C. L. C. Kulik. 1982. “Educational Outcomes of Tutoring: A Meta-Analysis of Findings.” American Educational Research Journal 19 (2): 237–248.

- Department of Education and Skills. 2019. Effective Interventions for Struggling Readers: A Good Practice Guide for Teachers. 2nd ed. Department of Education and Skills.

- Diamond, J., and W. Evans. 1973. “The Correction for Guessing.” Review of Educational Research 4 (2): 181–191.

- Doughtery Stahl, K. A. 2012. “Complex Text or Frustration Level Text: Using Shared Reading to Bridge the Difference.” The Reading Teacher 66 (1): 47–51.

- Gunn, B., K. Smolkowski, A. Biglan, and C. Black. 2002. “Supplemental Instruction in Decoding Skills for Hispanic and non-Hispanic Students in Early Elementary School: A Follow-up.” The Journal of Special Education 36 (2): 69–79.

- Henk, W., and S. Melnick. 1995. “The Reader Self-Perception Scale (RSPS): A New Tool for Measuring How Children Feel About Themselves as Readers.” The Reading Teacher 48 (6): 470–482.

- Lam, S. F., K. Chow-Yeung, B. P. H. Wong, K. Kiu Lau, and S. In Tse. 2013. “Involving Parents in Paired Reading with Preschoolers: Results from a Randomized Controlled Trial.” Contemporary Educational Psychology 38: 126–135.

- Lavan, G., and J. Talcott. 2020. Brooks’s What Works for Literacy Difficulties? The Effectiveness of Intervention Schemes. 6th ed. The School Psychology Service Ltd.

- Leung, C. K. C., H. W. Marsh, and R. G. Cravem. 2005. “Are Peer Tutoring Programmes Effective in Promoting Academic Achievement and Self-Concept in Educational Settings: A Meta-Analytical Review.” Association for active Educational Researchers Annual Conference, Cairns, Australia.

- Lohan, A., and F. King. 2016. “A Cross-Age Peer-Tutoring Programme Targeting the Literacy Experiences of Pupils with Social, Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties (SEBD) and Pupils with Low Levels of Literacy Achievement.” Unpublished paper.

- Lord, F. M. 1963. “Formula Scoring and Validity.” Educational and Psychological Measurement 23: 663–672.

- Mattson, D. 1965. “The Effects of Guessing on the Standard Error of Measurement and the Reliability of Test Scores.” Educational and Psychological Measurement 25: 727–730.

- Monteiro, V. 2013. “Promoting Reading Motivation by Reading Together.” Reading Psychology, 34 (4): 301-335.

- Nugent, M. 2001. “Raising Reading Standards- the Reading Partners Approach, Cross age Tutoring in a Special School.” British Journal of Special Education 28 (2): 71–79.

- O Riordan, J. 2013. “An Investigation Into the Effectiveness of a six Week Paired Reading Intervention, Using Cross age Peer Tutors, on a Student’s Reading Development.” Journal of the Irish Learning Support Association 36: 66–89.

- Reading Association of Ireland. 2011. A Response by Reading Association of Ireland to the Department of Education and Skills Document – Better Literacy and Numeracy for Children and Young People: A Draft Plan to Improve Literacy and Numeracy in Schools. Dublin: Reading Association of Ireland.

- Ritter, G. W., J. H. Barnett, G. S. Denny, and G. R. Albin. 2009. “The Effectiveness of Volunteer Tutoring Programmes for Elementary and Middle School Students: A Meta-Analysis.” Review of Educational Research 79 (1): 3–38.

- Shah-Wundenberg, M., D. Wyse, and R. Chaplain. 2012. “Parents Helping Their Children Learn to Read: The Effectiveness of Paired Reading and Hearing Reading in a Developing Country Context.” Journal of Early Childhood Literacy 13 (4): 471–500.

- Share, D. L., and K. E. Stanovich. 1995. “Cognitive Processes in Early Reading Development: Accommodating Individual Differences in a Model of Acquisition.” Issues in Education 1: 1–57.

- Stanovich, K. E., and R. West. 1989. “Exposure to Print and Orthographic Processing.” Reading Research Quarterly 26: 402–429.

- Suas Annual Report 2019. 2019. https://www.suas.ie/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Suas-Annual-Final-Report-2019.pdf.

- Szczerbinski, M. 2011. “Group Reading Test-ENG.” Unpublished manuscript, University College Cork.

- Topping, K. J. 1990. “Outcome Evaluation of the Kirklees Paired Reading Project.” PhD diss. White Rose Etheses Online database.

- Topping, K. J. 1998. “Commentary: Effective Tutoring in America Reads: A Reply to Wasik.” The Reading Teacher 52 (1): 42–50.

- Topping, K. J. 2003. “Paired Reading with Peers and Parents.” Oideas 50: 103–124.

- Topping, K. J. 2014. “Paired Reading and Related Methods for Improving Fluency.” International Electronic Journal of Elementary Education 7 (1): 57–70.

- Topping, K. J., D. Miller, A. Thurston, K. McGavock, and N. Conlin. 2011. “Peer Tutoring in Reading in Scotland: Thinking Big.” Literacy 45 (1): 3–9.

- Topping, K. J., A. Thurston, K. McGavock, and N. Conlin. 2012. “Outcomes and Process in Reading Tutoring.” Educational Research 54 (3): 239–258.

- Vygotsky, L. S. 1978. Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Wasik, B. A., and R. A. Slavin. 1993. “Preventing Early Reading Failure with one-to-one Tutoring: A Review of Five Great Programmes.” Reading Research Quarterly 28 (2): 179–200.

- Willingham, D. T. 2015. Raising Kids Who Read: What Parents and Teachers Can Do. San Francisco: Jossey Bass.

Appendix 1

Quotes from tutors regarding their Paired Reading experience

Quotes from tutors have been included verbatim. Names of tutees have been changed to protect confidentiality.

I was paired with a fourth class girl who came on leaps and bounds with this programme. At the start she couldn't remember the title of the book but by the end she was bringing books home with her.

I was working with a 9 year old child all term. English was his second language, and his first was Polish. He found it so difficult to pronounce words that had silent letter in them, but i realised by the end of the term, he was pronouncing words like knife, calm and island with no bother. It made me very happy.

Brian had a big transformation from start to finish. He grew in confidence and strength each week and it was really fulfilling to know that you helped contribute to that change.

It was great to work with individual children and to see and track the progression in these children. The confidence building in the children is great to see too.

From my experience, I noticed a difference in the child I was working with from when we started to when we finished. The child, at first, had no interest in reading or continuing into third level education. Towards the end the child had told me that they were reading a couple of pages a night and their attitude for third level education had changed and that they hope to go to college someday.

It would be fantastic if you could make it [tutoring] a mandatory part of some courses, as I feel it would be of equal benefit to third level students as it is for primary school children.

I will definitely be signing up again for the third time now if my timetable allows. Such a worthwhile experience

Thank you so much for giving me the opportunity to partake in this programme. It has inspired me to help others and join more voluntary groups. I will definitely do it again.