ABSTRACT

This article reports on baseline data gathered as part of an intervention project which aims to enhance academic performance, encourage retention and broaden the educational and career aspirations of senior cycle students in schools which serve socio-economically disadvantaged communities. The experiences and perceptions of 405 students attending 16 DEIS (Delivering Equality of Opportunity in Schools) schools who are participating in a voluntary after-school tuition programme are reported. Specifically, the article provides a demographic profile of the students in relation to familial education levels and parental occupations; explores whether the students had previously considered leaving school and what specific factors influenced their retention; and reports on the results of two standardised questionnaires, measuring perceived self-efficacy and sense of school belonging. Findings indicate that students reported an overall low level of self-efficacy but a positive sense of belonging in schools, with no differences reported across gender. Differences were observed, however, between those who had considered early school leaving and those who had not, with the former cohort recording lower self-efficacy and sense of belonging scores. This article presents an important, and possibly the first, profile of senior cycle students from DEIS schools who have demonstrated academic resilience in terms of school retention, career ambition, and availing of additional support in their schools through this intervention project.

Introduction

This paper is based on data gathered at the initial stages of a major research project, entitled Power 2 Progress, which involves an initiative to enhance academic performance, encourage retention and participation and broaden the educational and career aspirations of senior cycle students in schools which serve socio- economically disadvantaged communities.Footnote1 A total of 607 students from 16 DEIS post-primary schools are participating in the research. The primary focus of the initiative is to provide additional, in-school, out of hours, tuition to students over two years of the senior cycle as they prepare for the Leaving Certificate examination, which is the terminal examination taken by Irish students, as they exit second-level education. Other initiatives include full-day visits to the university in which the research is based and the involvement of personnel from a corporate entity which is funding the research to encourage students to widen their horizons in terms of educational and career options. A core focus of the research is to enhance the social and cultural capital of participating students and to ‘level the playing field’ with students from more affluent communities.

Policy context

The orthodoxy within political and policy circles is to pledge a commitment to social justice and a drive to realise this objective through the education system. This social justice narrative runs, however, alongside, and often in collision with, a neoliberal agenda, as manifested in international assessment regimes such as PISA, in which targets and metrics reign supreme over experience and well-being (Rizvi and Lingard Citation2010). In a global, ethereal space where scores and targets hold sway and where student experience and well-being rank as subordinate, inequalities become re-presented as issues that pertain to the individual, an individual school or school type, and a particular community setting (Ball Citation2008). A deficit discourse facilitates this reasoning, and creates a political and public policy narrative in which the ‘problem’ is located elsewhere, in the ‘disadvantaged school, the ‘disadvantaged community’ and the ‘disadvantaged student.’ The very term educational disadvantage can contribute to this discourse, adding to the construction of deficited ‘cultural models’ in which ‘the disadvantaged’ become a recognisable entity that is different, othered, objectified and often vilified’ (Gee Citation2011, 174; Cahill Citation2015).Footnote2

Despite the accentuation of policy in the area of educational disadvantage, recent scholarship has highlighted how the education system propagates and legitimates inequality, reproducing intergenerational advantages for dominant social groups and exposing the close relationships between education, inequality and class (Fleming and Harford Citation2021). The corpus of research also suggests that not only is social class continuing to shape and predict individual outcomes, the social class divide is becoming even more pronounced empowering those already advantaged to use their social and cultural capitals to mobilise further advantage, a phenomenon which has intensified in the Irish context since the 1970s (Raftery and Hout Citation1993). An intensification of after-school tuition, usually in the form of grinds, is particularly evident in recent years because of the high-stakes nature of the Leaving Certificate examination, with many higher-income families accessing private tuition or grinds, as well as summer camps which focus on languages, science and a range of other curricular areas (Lynch and Crean Citation2018; McAvinue Citation2020; McCoy and Byrne Citation2022). This activity ensures the cultural reproduction of the middle classes in a market-driven system (Canny and Hamilton Citation2018) despite the financial burden; the Irish League of Credit Unions reported that 27% of Irish families found themselves in debt in 2020 paying for their children’s education (ILCU Citation2020).

The financial as well as personal stress experienced by parents and guardians of students in DEIS schools was exacerbated by the recent Covid 19 pandemic (Mohan et al. Citation2021). Learnings from Covid 19 confirm the fact that disruption to the rhythm of school-life, particularly attempts to move to remote learning, was more acutely felt among students from socio-economically disadvantaged backgrounds, as well as students with special needs, two groups which evidence significant overlap (Murray et al. Citation2021). Recent research from the Educational Research Centre (Nelis et al. Citation2021) found that almost a quarter of students in DEIS schools, (compared to one-seventh in non-DEIS schools) had special educational needs (SEN).

The Delivering Equality of Opportunity in schools (DEIS) scheme

The response of the Irish government to the issue of educational disadvantage was to devise a scheme formalised in 2005, the DEIS scheme, which was essentially a policy of positive discrimination, whereby additional resources were to be allocated to schools which catered for high numbers of students, from low socioeconomic status (SES) backgrounds. The scheme introduced an independent standardised system for determining which schools were entitled to participate based on a deprivation index, which included variables such as employment status, education levels, single parenthood, overcrowding and dependency rates. Schools which were thus identified as providing for high proportions of students from low SES backgrounds were assigned additional resources in order to help break down barriers and stem the cycle of inter-generational disadvantage (DES Citation2005; Weir Citation2016). Almost seventeen years on, the scheme remains the roadmap for addressing educational disadvantage and currently includes 658 primary and 194 post-primary schools. While the DEIS initiative has led to some improvements, the two-tier nature of access to higher education suggests that the programme is not comprehensive enough nor adequately resourced. Moreover, the linear, narrow and segregationist nature of the scheme (Fleming and Harford Citation2021) is such that it fails to take account of thousands of children who are reported by the Children’s Rights Alliance (Citation2020) and Social Justice Ireland (Citation2019) to be living in consistent poverty, not all of whom attend DEIS schools. While there is considerable evidence to support the view that the DEIS scheme has had a number of benefits, there is also a body of evidence to suggest that the scheme has merely reinforced the existing hierarchy within the education system and has in fact ghettoised schools. Analysis of the data for 2018/19 demonstrates that there were on average 4.9 students from disadvantaged areas to every 10 students from affluent areas accessing higher education, with only 55 students nationally coming from ‘extremely disadvantaged’ backgrounds. The most prestigious courses in areas such as law, medicine, pharmacy and dentistry, also the courses with the highest points, enrolled only 4 percent of students from disadvantaged backgrounds (HEA Citation2021). This is clearly not just an Irish phenomenon but is replicated internationally (Chesters and Watson Citation2013; McCowan and Bertolin Citation2020). According to Fleming and Harford (Citation2021, 15), ‘while marginal progress has been made since the introduction of the DEIS scheme in 2005, educational disadvantage continues to be viewed as a school-based issue, with a lack of recognition and response at a policy level of its fundamental, deep-seated relationship with wider economic inequalities across Irish society’.

The most recent version` of the DEIS scheme, the 2017 DEIS Review, articulates the objective of the DEIS scheme as follows: ‘for education to more fully become a proven pathway to better opportunities for those in communities at risk of disadvantage and social exclusion’ (DEIS Citation2017, 6). The same report articulates the Department’s ambition ‘to become the best in Europe at harnessing education to break down barriers and stem the cycle of inter-generational disadvantage by equipping learners to participate, succeed and contribute effectively to society in a changing world’ (Ibid). Among the targets outlined in DEIS Citation2017 are improved literacy and numeracy standards, increased second-level school retention rates, and increased rates of progression to further and higher education. The aims of the current research project, on which this paper is based, align closely with these broad aims. The Department of Education proposed to meet these targets through five key goals: implementing a more robust and responsive assessment framework for identification of schools and effective resource allocation; improving the learning experience and outcomes of students in DEIS schools; augmenting the capacity of school leaders and teachers to engage, plan and deploy resources to their best advantage, supporting and fostering best practice in schools through interagency collaboration; and supporting the work of schools by providing research, information, evaluation and feedback to achieve the goals of the plan (DES Citation2017, 9). Supporting young people to ‘develop resilience’ and ensuring that ‘mental resilience and personal wellbeing are integral parts of the education and training system’ (Ibid., 37) are also core objectives of this plan.

Beating the system

Despite the systemic, pervasive and engrained nature of educational disadvantage, a minority of students succeed in ‘beating’ the system, exhibiting personal and academic resilience. The OECD defines resilient students as those ‘who come from a disadvantaged socioeconomic background and perform much higher than would be predicted by their background’ (OECD Citation2010, 62). Resilience in students is considered to be a key factor that contributes to a high-quality school experience, realised through constructive relationships, school support, access to material resources, food, and fair treatment to enable a strong identity and a sense of social justice (Theron and Theron Citation2014; Tatlow-Golden et al. Citation2016). Resiliency theory postulates that both innate and external protective factors can support individuals in overcoming adversity (Benard Citation2004), however, it is clear that a more detailed, nuanced understanding of the processes associated with academic resilience is required (Schoon Citation2006; Rutter Citation2012). The minority of students who exhibit the level of resilience required to ‘make it through’ is evidence of the diversity of experience of students in DEIS schools and illustrative of the importance of not employing social and cultural capital theories as ‘static concepts for dichotomous class comparisons’ (Kettley and Whitehead Citation2012, 503) or over-stating homogeneity of experience based on social class (Irwin and Elley Citation2011). This further emphasises the need to explore both individual and broader contextual factors, including, but not confined to, school and family, in exploring academic resilience.

The study

The Power 2 Progress (P2P) intervention aims to enhance the school experiences of senior cycle students in 21 DEIS schools, by providing them with additional tuition in subjects identified as priorities by the students and by encouraging them to broaden their educational and career ambitions.Footnote3 The tuition is delivered principally by student teachers, supplemented by a small number of qualified teachers. Data on the intervention is being gathered at three time-points: the beginning of Fifth Year, the end of Fifth Year and the end of Sixth Year. The research employs a mixed-methods approach, involving questionnaires with students, tutors, and current class teachers; focus group interviews with students and tutors; and individual interviews with parents and with key informant school personnel. Data on school attendance during the junior cycle years (pre-intervention) is being compared with attendance during the intervention period, that is, during the senior cycle. Student academic performance in terms of Junior Certificate and Leaving Certificate results will also be compared.

This paper reports on findings from the pre-intervention questionnaires which were administered to the participating students prior to the commencement of weekly tuition sessions. The questionnaire was administered anonymously through Qualtrics software and included both open and closed questions on student demographics, family education history, and student career aspirations, as well as two standardised questionnaires that were slightly modified for the Irish context. The first standardised questionnaire was the Self-Efficacy Formative Questionnaire by Gaumer Erickson et al. (Citation2018) which measures students’ perceived level of proficiency in two components of self-efficacy, which are: the belief that ability can grow with effort and belief in one’s ability to meet specific goals and/or expectations. The second standardised questionnaire was the Sense of Belonging in School questionnaire first designed in 1994 by Hagborg which included 18 items but which was subsequently adapted by McLellan & Morgan in Citation2008 to include 12 items. The questionnaire covers three areas: a general sense of belonging, feeling different, and respect.

Participants

A total of 607 students enrolled in the P2P programme in September 2021 and a total of 429 students completed the survey, which is a response rate of 70.7%. After cleaning the data, the number was reduced to 405 participants. All fifth year students in the participating schools were presented with information relating to the programme by the programme team in the previous academic year. Potential participants also had the option of availing of the tuition, without participating in the research project. The majority of students who signed up to the programme are studying the traditional Leaving Certificate curriculum, although a minority are engaged with the Leaving Certificate Applied (LCA) programme, on which performance is assessed by continuous assessment rather than by terminal examination. presents demographic data as reported by the 405 respondents. Not all 405 participants fully completed the entire questionnaire, which explains discrepancies in the numbers of participants throughout the results.

Table 1. Demographic data (N = 405).

The majority of the respondents were female, with a female to male ratio approaching 2:1. In relation to ethnicity, almost three-quarters of respondents identified as ‘White’, with Asian and Black students also represented. English was identified as the language spoken at home for the vast majority of respondents, although, in the case of 30 participants (7.4%), English was spoken either ‘rarely’ or ‘not at all’ in the home. Approximately, two-thirds of respondents had completed Transition Year, which is an optional year offered in most Irish post-primary schools post completion of the Junior Cycle (Years 1-3) prior to embarking on the Senior Cycle (Years 5-6).

Findings

All 405 participants responded to a question relating to parental levels of education. Just over 11% (N = 45) reported that their parents or guardians had left school before the age of 16 years, and a similar proportion reported that their parents or guardians had completed apprenticeships. Twenty-nine per cent (N = 117) of students reported that their parents had completed the Leaving Certificate Examination. Approximately 11% (N = 45) of students reported that their parents had obtained a graduate qualification, with approximately 9% (N = 37) reporting postgraduate parental education. Participating students were asked to provide information on parental occupations and the majority of the identified occupations were of a manual nature, i.e. decorator, care assistant, construction worker, hairdresser, chef, and factory worker, with a small proportion reporting careers such as nurses (14), doctors (3), and lawyers (1). In total, 63.5% (N = 257) reported that their parents were employed full time, while 16.3% (N = 66) were employed part-time, 3% (N = 12) were seeking employment, 1.5% (N = 6) were retired, 4.7% (N = 19) were unable to work for medical reasons, and 11.1% (N = 45) were unemployed. In relation to educational history of older siblings, one-third of participants did not have older siblings and, of the remaining 274, a total of 69 (25%) reported that their siblings did not proceed on to further education.

A total of 395 students responded to a question relating to future educational and occupational aspirations (See ), with some participants selecting more than one option. The vast majority of students (87%; N = 345) indicated an ambition to proceed on to higher education, with the gender balance broadly reflecting the gender balance of the overall sample. Approximately 14% (N = 56) were hoping to enter further education, for example, a Post Leaving Certificate (PLC) course, with a similar proportion opting for an apprenticeship, the majority of whom were males, despite there being a majority of females in the sample, reflecting the gendered nature of apprenticeships. Almost 20% (N = 78) were expecting to enter unskilled employment. These trends were reflected in responses to a question about their preferred occupations, as the majority of the career choices would require a bachelor’s degree for their chosen occupation, i.e. pharmacy, teacher, lawyer, medicine, accounting, and graphic designer. There was also a small minority of students who aspired to work in skilled labour occupations which did not require a degree, such as, garda, carpenter, beautician, or chef.

Table 2. Educational and Occupational Aspirations (N = 395).

Students were asked to indicate if they had ever considered leaving school, to which approximately 23% (N = 89) replied ‘Yes’, with relatively similar proportions of males (24.5%) and females (21.3%) reporting this response. The factors which led students to consider leaving school are ranked in , with stress and mental health being identified most frequently, by over one-quarter of the 94 respondents, with 14 of these respondents preferring not to identify a reason. In a related question as to why they then decided to remain on in school, the most frequently selected options were ‘parental pressure’, the desire ‘to have an education’, ‘to go to college’ and ‘better my future’ with 23 of the 94 respondents opting not to select a response.

Table 3. Factors Influencing Consideration to Leave School (N = 94).

Self-efficacy

The participating students completed an adapted standardised self-efficacy formative questionnaire. This questionnaire is designed to measure a student’s perceived level of belief that ability can grow with effort (5 questions) and belief in one’s ability to meet specific goals and/ or expectations (8 questions). The questionnaire scores were converted into a 100-point scale and the overall self-efficacy scores were categorised into three groups, 0-77 = Low self-efficacy, 78-91 = Average self-efficacy and 92-100 = High self-efficacy (Gaumer Erickson, and Noonan Citation2016). As outlined in , the average overall self-efficacy score for 397 respondents in this study was 74.4872 (SD = 15.06), which would be categorised as a low self-efficacy score (Gaumer Erickson et al. Citation2018). Likewise, the mean personal ability score was low, while the belief that ability grows with effort score was average, suggesting that, despite below average perceptions of their abilities, the students believed that they could progress with effort.

Table 4. Self-Efficacy Scores (N = 397).

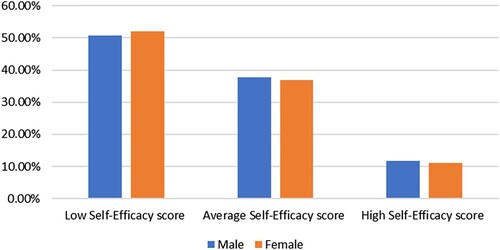

As demonstrated in , approximately 50% of students reported low perceived self-efficacy scores, just over one-third reported average scores, with only about 11% reporting high levels of perceived self-efficacy. The trends were almost identical across gender (See ). Self-efficacy scores were also compared across groups of those who had, and who had not, considered leaving school early and almost 70% (n = 63) of those who had considered early school-leaving reported low perceived self-efficacy scores, compared to 46% (N = 141) within the group who had not contemplated early school-leaving.

Sense of belonging

The sense of belonging questionnaire was first designed in 1994 by Hagborg which included 18 items but was subsequently adapted by McLellan & Morgan in Citation2008 to include 12 items. Within this study we adapted the McLellan and Morgan (Citation2008) version in order to make it appropriate for the Irish schools’ setting. The questionnaire was completed by 391 students, who responded on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from regarding a statement as ‘not at all true’ to ‘completely true’. The mid-point of the scale was thus 2.5, a score above which would indicate an overall positive response to a positively worded statement, and below which a score would indicate a negative either agreement with, or a neutral response to, most of the positive statements. The indications are: students felt respected by teachers; perceived teachers noticed when a student was good at something; there was at least one teacher perceived as being approachable when necessary; teachers were interested in students’ progress; the wider school community was regarded as ‘friendly’; and participants generally felt proud to be students in their schools. Similarly there was disagreement with negative statements such as finding it difficult to fit into the school or not feeling that they belonged in the school or feeling different from most students. One exception to this trend was a low level of agreement with a statement about being an important part of the school (Mean = 2.09). Overall, the data suggests a positive sense of belonging to, and fitting into, school, though the standard deviations reported in indicate a considerable degree of spread across scores.

Table 5. Sense of belonging questionnaire.

The 12 items in this scale can be conceptualised as three different factors as follows: ‘Sense of Belonging’ in a school community, based on seven questions; ‘Feeling Different’ from other students, based on four questions; and ‘Respect from Peers’, based on three questions. The descriptive statistics for these three scales are provided in . The mean score of 18.55 on the Sense of Belonging Scale is slightly above the mid-point of 17.5, suggesting that the students reported an average sense of belonging to their school community. The high Cronbach co-efficient of 0.765 would suggest that this is a unitary scale, yielding a reliable score. Likewise the Cronbach co-efficient of 0.789 on the Respect from Peers scale is reliable and the mean score of 8.42 is above the midpoint of 7.5, suggesting positive perspectives of participants in relation to perceived respect from peers. These scores suggest that, overall, the students feel an average level of belonging in their schools and feel respected by peers. The mean score of 8.61 for ‘Feeling Different’ is below the mid-point score of 10, but because this scale is comprised of negatively formulated questions, this would indicate an overall positive perception that they do not feel different from others and the Cronbach co-efficient of 0.815 is considered high.

Table 6. Descriptive Statistics for Sense of Belonging Scale (N = 391).

Differences across gender were explored in relation to scores on each of the three dimensions of School Belonging and no significant differences were found, as outlined in .

Table 7. Gender differences on dimensions of school belonging.

When these scores were compared between those who had contemplated leaving school and those who had not considered early school leaving, significant differences were found between the groups on each of the three dimensions (< 0.05), as outlined in . Students who had not considered leaving school reported a higher sense of belonging to the school community and reported higher levels of perceived respect from peers. Those who had considered leaving school achieved significantly higher scores on the Feeling Different scale than those who had not done so. Because these are negatively formulated statements, higher scores constitute a negative perception and a greater sense of perceived difference from peers, with the caveat that this is not a unitary scale. The findings suggest that potential early school-leavers have a lower sense of school belonging, perceive themselves as commanding less respect from peers and report higher levels of feeling different from peers, when compared to those who had not considered leaving school.

Table 8. Differences between groups according to consideration of early school-leaving.

Finally, scores on the various dimensions of the two standardised questionnaires, Gaumer Erickson, and Noonan’s (Citation2016) Self-efficacy Questionnaire and McLellan and Morgan’s (Citation2008) Sense of Belonging Questionnaire, were examined for correlations. The correlations are provided in .

Table 9. Correlations between dimension scores on self-efficacy and sense of school belonging scales.

The findings from the Pearson correlations between the variables found the following significant relationships; the students’ overall Sense of Belonging Score correlated positively with the students’ overall Self-Efficacy Score (r(397) = .322, p < .001); and with the scores on the two self-efficacy subscales (Perceived ability score: (r(397) = .268, p < .001); and belief that ability grows with effort score: (r(397) = .321, p < .001). Similarly, positive correlations were found between two of the Sense of Belonging subscales (General Sense of Belonging and Respect from Peers) and the Self-Efficacy scores. This means that students who reported a high sense of belonging and who felt respected by peers also reported high levels of perceived self-efficacy. In contrast, as would be expected, Feeling Different scores were negatively correlated with self-efficacy scores, though the correlation was not significant (r (391) = -.053, p. = 298).

Discussion

This paper is presenting baseline findings from an intervention study which aims to enhance academic resilience amongst senior cycle students in DEIS schools, with a focus on improving academic performance, encouraging school retention and broadening educational and career aspirations. Out of a total of 607 students participating in the study, by availing of additional tuition in subjects of their choice throughout the final two years of post-primary education, 405 students completed questionnaires yielding a demographic profile which may be the first such profile of senior cycle students in DEIS schools. Such schools are categorised in this way because a high proportion of their students are socially and economically disadvantaged. This does not mean that all students attending DEIS schools are disadvantaged, nor does it mean that all disadvantaged students attend DEIS schools. It is thus important to obtain a demographic profile of students in such schools. It is particularly important to construct a profile of the students in this study who are demonstrating academic resilience, in that they have remained in school beyond the compulsory school-attendance age and have availed of this opportunity to enhance their educational and career opportunities.

The pervasive, stubborn, inter-generational nature of educational disadvantage

One of the key findings which emerged from this study, in line with a wide corpus of literature in the field (Lynch and O’ Riordan Citation1998; Byrne and McCoy Citation2017; Reay Citation2017), was the pervasive, stubborn intergenerational nature of educational disadvantage. The link between the level of parental education and engagement with schooling and child outcomes is well-established (Dickson, Gregg, and Robinson Citation2016; Lundborg, Nilsson, and Rooth Citation2014). Eleven per cent of students in this study reported that their parents or guardians had left school before the age of 16 years. The majority identified their parents’ occupations as being of a manual nature, i.e. decorator, care assistant, construction worker, hairdresser, chef, and factory worker. Just over 10 per cent of students reported parental unemployment, and earlier studies have indicated the extent to which unemployment levels in DEIS communities can negatively pervade the work of the school (Weir et al. Citation2018; Fleming and Harford Citation2021). Pointing again to the systemic, cyclical nature of educational disadvantage, a quarter of students in this study who had older siblings reported they had had not progressed to higher education. This tallies with recent data on progression rates to higher education among DEIS students. Almost all Leaving Certificate students (99.7 per cent) from fee-charging schools progressed to third level institutions in 2021, compared with 62 per cent from DEIS schools (O’Brien, O Callai, and McGuire Citation2022). While there is evidence to suggest that some families from disadvantaged backgrounds may not value higher education as it is alien to their own experiences (Lynch and O’ Riordan Citation1998; Hutchings and Archer Citation2001), thus impacting on children’s attitudes towars further and higher education, recent research indicates a rise in expectations of parents of DEIS school students, with over half signalling expectations that their child will complete a university degree (Weir et al. Citation2018; Nelis et al. Citation2021). The impact of parental expectations is considered to be as important as that of teacher expectations (Zhu et al. Citation2014; Malmberg, Ehrman, and Lithén Citation2005; Young et al. Citation2008; Oyserman, Johnson, and James Citation2011), however in the absence of systemic supports for students in educationally disadvantaged contexts, the determination and encouragement of parents can hit a 'brick wall of constraint’ (Irwin and Elley Citation2013, 127). Interviews with parents and guardians of students enrolled in this programme will take place in 2023 at which point parent/guardian attitudes and expectations regarding their child’s progression to further and higher education will be examined.

What did emerge from this pre-intervention data phase, however, was a very clear indicator that students in this study wished to progress on to higher education. 87.35% indicated an ambition to proceed on to higher education, with the majority of career choices identified requiring a graduate qualification. Subsequent stages of data gathering will assess whether or not this figure translates into actual applications, or whether, in line with earlier research (Baker et al. Citation2014; Scanlon et al. Citation2019), this figure decreases owing to a lack of confidence, concerns about territorial stigmatisation, a sense of not being good enough and financial impediments. Importantly, while the ambition to progress on to higher education is often not realised, the intent to progress is unequivocal from the respondents in this study, reflecting their academic resilience, at least at this point of data capture. Maintaining this ambition and putting in place the support structures to see it to fruition is clearly what is required.

Choosing to check out or stay engaged

Equally urgent is reaching those students who do not retain the academic resilience to hope for higher education progression, but who instead look to ‘check out’ at an earlier point. Almost a quarter of respondents in this study indicated that they had previously considered leaving school, with stress and mental health being identified most frequently as the trigger for this decision. These findings are not unexpected and dovetail with recent research in relation to stress levels and well-being among DEIS school students (Scanlon et al. Citation2019; Fleming and Harford Citation2021). While the Department of Education has responded to concerns in relation to well-being and stress levels by introducing the Wellbeing in Education initiative, greater resourcing of trained personnel with expertise to deal with the more serious cases is urgently required (Fleming and Harford Citation2021). In a related question as to why students in this study opted to remain on in school, the most frequently selected options were ‘parental pressure’, the desire ‘to have an education’, ‘to go to college’ and ‘better my future,’ indicating a broad understanding of the significance of education to their future life trajectories.

Low levels of self-efficacy

The study also examined levels of self-efficacy and of belonging through the administering of two standardised questionnaires, measuring perceived self-efficacy and sense of school belonging. Findings indicate that students reported an overall low level of self-efficacy but a positive sense of belonging in schools, with no differences reported across gender. Approximately one-half of respondents reported low perceived self-efficacy scores, just over one-third reported average scores, and only 11% reported high levels of perceived self-efficacy. These trends were almost identical across gender, but differed between those who had contemplated leaving school early and those who had not done so, with potential early school-leavers reporting lower levels of self-efficacy. These findings mirror those of MacPhee, Farro, and Canetto (Citation2013) who found that individuals from a lower social class reported lower levels of self-efficacy, yet after participating in a mentoring programme, self-efficacy scores increased. This resonates with more recent research in the Irish context which highlights the potential for mentors to build socio-economically disadvantaged students’ social capital and trust (Hannon, Faas, and O'Sullivan Citation2017). Relatedly, McAvinue (Citation2020) argues for the importance of students in DEIS schools being supported to develop a strong academic self-concept, academic self-worth more often than not proving tenuous in vulnerable students (Archer and Yamashita Citation2003).

Average levels of belonging

Responses to a Sense of Belonging Questionnaire (McLellan and Morgan Citation2008) indicate that, overall, students felt an average level of belonging in their schools and felt respected by peers. No significant differences were found across gender in this regard. Again, as might be expected, students who had not considered leaving school reported a higher sense of belonging to the school community and reported higher levels of perceived respect from peers. Exploration of correlations across dimensions of the two scales, Self-efficacy and Sense of Belonging, revealed significant correlations, indicating a relationship between students’ levels of perceived self-efficacy and their sense of belonging in school.

Concluding thoughts

This article presents an important, and possibly the first, profile of senior cycle students from DEIS schools who have demonstrated academic resilience in terms of school retention, career ambition, and availing of additional support in their schools through the intervention programme, Power2Progress. It confirms the pervasive, inter-generational nature of educational disadvantage, despite decades of rhetoric surrounding educational equality. It also testifies to the high number of students in DEIS schools who consider early school leaving, echoing previous research demonstrating the cleavage between the norms, values and aims of schooling and the lived reality of students on the margins. At the same time, the article highlights the ambition of the vast majority of students in this study to progress on to higher education. We know from previous research that this ambition is often stymied by of a range of social, cultural and economic obstacles. Hence, translating this ambition into actual progression to further and higher education must be recognised as a key national policy priority. While in the case of this particular intervention, the necessary funding, digital infrastructure, partnerships and personnel are in place in order to optimise the chances of this objective being realised, it is important to point out that only a minority of the cohort of senior cycle students nationally who attend DEIS schools participate in this programme. It must also be remembered that outside of the DEIS framework, there are many students who attend schools who are socially and economically disadvantaged and for whom equality of educational access, condition and outcome remains elusive. Thus, if meaningful, sustainable reform of the education system is to be achieved, and if the experience of education being inextricably linked with social class is no longer a reality, a national policy response which takes account of the deep-seated relationship between educational disadvantage and wider social and economic inequalities across Irish society, is urgently required.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Amalia Fenwick

Amalia Fenwick is a Ph.D. student at the School of Education, UCD and Co-Ordinator of the Power2Progress Programme. Her research interests are educational disadvantage and building academic resilience. She is co-author (with Billy Kinsella) of ‘A School Completion Initiative in a Primary School in Ireland’. Education Research and Perspectives, (2020), 47, 25-52.

Billy Kinsella

Associate Professor William Kinsella is Head of UCD School of Education. He lectures in Education, Special Education, and Educational Psychology. He is Course Director of three programmes within the School of Education, including the recently developed national online training programme for Special Needs Assistants (SNAs). Research Interests include Inclusive Education, Special Educational Needs and Disabilities, Ethical Education and Educational Disadvantage.

Judith Harford

Judith Harford is Professor of Education at the School of Education, UCD. Her research area is history of education with a particular focus on gender and social class. Her books include The Opening of University Education to Women in Ireland (Irish Academic Press, 2008); Secondary School Education in Ireland: History, Memories and Life Stories, 1922–67 (Palgrave Macmillan, 2015); A Cultural History of Education in the Modern Age (Bloomsbury, 2020) and Piety and Privilege: Catholic Secondary Schooling in Ireland and the Theocratic State, 1922–67 (Oxford University Press, 2021).

Notes

1 This research was funded by the Z Zurich Foundation.

2 The term ‘educational disadvantage’ is used in this article as this is the term used in the Education Act of 1998 which defines educational disadvantage as ‘the impediments to education arising from social or economic disadvantage which prevent students from deriving appropriate benefit from education in schools’.

3 An additional five schools were recruited to the programme in September 2021 bringing the overall number of participating schools to 21 as a result of funding from Rethink Ireland.

References

- Archer, L., and H. Yamashita. 2003. “Knowing Their Limits'? Identities, Inequalities and Inner City School Leavers’ Post-16 Aspirations.” Journal of Education Policy 18 (1): 53–69.

- Baker, W., P. Sammons, I. Siraj-Blatchford, K. Sylva, E. C. Melhuish, and B. Taggart. 2014. “Aspirations, Education and Inequality in England: Insights from the Effective Provision of Pre-School, Primary and Secondary Education Project.” Oxford Review of Education 40 (5): 525–542.

- Ball, S. J. 2008. The Education Debate. Bristol: The Policy Press.

- Benard, B. 2004. Resilience: What We have Learned. San Francisco: WestEd.

- Byrne, D., and S. McCoy. 2017. “Effectively Maintained Inequality in Educational Transitions in the Republic of Ireland.” American Behavioral Scientist 61 (1): 49–73.

- Cahill, K. 2015. “Seeing the Wood from the Trees: A Critical Policy Analysis of Intersections Between Social Class Inequality and Education in Twenty-First Century Ireland.” International Electronic Journal of Elementary Education 8 (2): 301–316.

- Canny, A., and M. Hamilton. 2018. “A State Examination System and Perpetuation of Middle-Class Advantage: An Irish School Context.” British Journal of Sociology of Education 39 (5): 638–653.

- Chesters, J., and L. Watson. 2013. “Understanding the Persistence of Inequality in Higher Education: Evidence from Australia.” Journal of Education Policy 28 (2): 198–215.

- Children’s Rights Alliance. 2020. https://www.childrensrights.ie/childrens-rights-ireland/childrens-rights-ireland.

- DES (Department of Education and Science). 2005. DEIS: Delivering Equality of Opportunity in Schools. Dublin: Author.

- DES (Department of Education and Skills). 2017. DEIS Plan 2017: Delivering Equality of Opportunity in Schools. Dublin: Author. https://www.education.ie/en/Publications/Policy-Reports/DEIS-Plan 2017.pdf.

- Dickson, M., P. Gregg, and H. Robinson. 2016. “Early, Late or Never? When Does Parental Education Impact Child Outcomes?” . The Economic Journal 126 (596): F184–F231.

- Fleming, B., and J. Harford. 2021. “The DEIS Programme as a Policy Aimed at Combating Educational Disadvantage: Fit for Purpose?” Irish Educational Studies, 1–19. 10.1080/03323315.2021.1964568.

- Gaumer Erickson, A. S., and P. M. Noonan. 2016. Research guide: Self-efficacy. Competency Framework. http://www.cccframework.org.

- Gaumer Erickson, A. S., J. H. Soukup, P. M. Noonan, and L. McGurn. 2018. Self-efficacy Formative Questionnaire Technical Report. University of Kansas.

- Gee, J. P. 2011. How to do Discourse Analysis. Oxon: Routledge.

- Hannon, C., D. Faas, and K. O'Sullivan. 2017. “Widening the Educational Capabilities of Socio-Economically Disadvantaged Students Through a Model of Social and Cultural Capital Development.” British Educational Research Journal 43 (6): 1225–1245.

- HEA (Higher Education Authority). 2021. National Access Plan 2022–2026 consultation paper. Layout 1 (hea.ie).

- Hutchings, M., and L. Archer. 2001. “‘Higher Than Einstein’: Constructions of Going to University among Working-Class non-Participants.” Research Papers in Education 16 (1): 69–91.

- ILCU (Irish League of Credit Unions). 2020. “ILCU survey shows marked increase in average debt of parents coping with, Back to School costs.” Available at: Back to School Costs - The Irish League of Credit Unions.

- Irwin, S., and S. Elley. 2011. “Concerted Cultivation? Parenting Values, Education and Class Diversity.” Sociology 45 (3): 480–495.

- Irwin, S., and S. Elley 2013. “Parents' Hopes and Expectations for their Children's Future Occupations.” The Sociological Review 61 (1): 111–130.

- Kettley, N. C., and J. M. Whitehead. 2012. “Remapping the “Landscape of Choice”: Patterns of Social Class Convergence in the Psycho-Social Factors Shaping the Higher Education Choice Process.” Educational Review 64 (4): 493–510.

- Lundborg, P., A. Nilsson, and D. O. Rooth. 2014. “Parental Education and Offspring Outcomes: Evidence from the Swedish Compulsory School Reform.” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 6 (1): 253–278.

- Lynch, K., and M. Crean. 2018. “Economic Inequality and Class Privilege in Education: Why Equality of Economic Condition is Essential for Equality of Opportunity.” In Education for All? The Legacy of Free Post-Primary Education in Ireland, edited by J. Harford, 139–160. Oxford: Peter Lang.

- Lynch, K., and C. O’ Riordan. 1998. “Inequality in Higher Education: A Study of Class Barriers.” British Journal of Sociology of Education 19 (4): 445–478.

- MacPhee, D., S. Farro, and S. S. Canetto. 2013. “Academic Self-Efficacy and Performance of Underrepresented STEM Majors: Gender, Ethnic, and Social Class Patterns.” Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy 13 (1): 347–369.

- Malmberg, L. E., J. Ehrman, and T. Lithén. 2005. “Adolescents’ and Parents’ Future Beliefs.” Journal of Adolescence 28 (6): 709–723.

- McAvinue, L. 2020. Tackling Educational Disadvantage: What can Schools do? Retrieved from: Tackling Educational Disadvantage_July2020.pdf.

- McCowan, T., and J. Bertolin. 2020. Inequalities in Higher Education Access and Completion in Brazil (No. 2020-3). UNRISD working paper.

- McCoy, S., and D. Byrne. 2022. “Shadow Education Uptake among Final Year Students in Secondary Schools in Ireland: Wellbeing in a High Stakes context.” ESRI Working Paper No. 724.

- McLellan, R., and B. Morgan. 2008. “Pupil Perspectives on School Belonging: An Investigation of Differences between Schools Working Together in a School University Partnership.” Paper presented at the British Educational Research Association Annual Conference, Heriot-Watt University, Edinburgh.

- Mohan, G., E. Carroll, S. McCoy, C. Mac Domhnaill, and G. Mihut. 2021. “Magnifying Inequality? Home Learning Environments and Social Reproduction During School Closures in Ireland.” Irish Educational Studies 40 (2): 265–274.

- Murray, A., E. McNamara, D. O'Mahony, E. Smyth, and D. Watson. 2021. “Growing Up in Ireland: Key Findings from the Special COVID-19 Survey of Cohorts’ 98 and ‘08.” ESRI Growing Up in Ireland. https://www.esri.ie/system/files/publications/BKMNEXT409.pdf.

- Nelis, S. M., L. Gilleece, C. Fitzgerald, and J. Cosgrove. 2021. Beyond Achievement: Home, School and Wellbeing Findings from PISA 2018 for Students in DEIS and non-DEIS Schools. Dublin: Educational Research Centre.

- O’Brien, C., É O Callai, and P. McGuire. 2022, 7 January. Students in Fee-Charging Schools More Likely to Progress to Courses with High Points. The Irish Times.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. 2010. PISA 2009 Results: Overcoming Social Background: Equity in Learning Opportunities and Outcomes (Volume II). Paris: OECD Publishing.

- Oyserman, D., E. Johnson, and L. James. 2011. “Seeing the Destination but not the Path: Effects of Socioeconomic Disadvantage on School-Focused Possible Self Content and Linked Behavioral Strategies.” Self and Identity 10 (4): 474–492.

- Raftery, A. E., and M. Hout. 1993. “Maximally Maintained Inequality: Expansion, Reform, and Opportunity in Irish Education, 1921–75.” Sociology of Education 66 (1): 41–62.

- Reay, D. 2017. Miseducation: Inequality, Education and the Working Classes. Bristol: Policy Press.

- Rizvi, F., and B. Lingard. 2010. Globalising Educational Policy. London: Routledge.

- Rutter, M. 2012. “Resilience as a Dynamic Concept.” Development and Psychopathology 24: 335–344.

- Scanlon, M., H. Jenkinson, P. Leahy, F. Powell, and O. Byrne. 2019. “‘How are we Going to do it?’An Exploration of the Barriers to Access to Higher Education Amongst Young People from Disadvantaged Communities.” Irish Educational Studies 38 (3): 343–357.

- Schoon, I. 2006. Risk and Resilience: Adaptations in Changing Times. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Social Justice Ireland. 2019. https://www.socialjustice.ie/content/publications-home.

- Tatlow-Golden, M., C. O’Farrelly, A. Booth, C. O’Rourke, and O. Doyle. 2016. “‘Look, I Have my Ears Open’: Resilience and Early School Experiences among Children in an Economically Deprived Suburban Area in Ireland.” School Psychology International 37 (2): 104–120.

- Theron, L. C., and A. M. Theron. 2014. “Education Services and Resilience Processes: Resilient Black South African Students’ Experiences.” Children and Youth Services Review 47: 297–306.

- Weir, S. 2016. Raising Achievement in Schools in Disadvantaged Areas. Cidree Yearbook 2016, pp. 76–89.

- Weir, S., L. Kavanagh, E. Moran, and A. Ryan. 2018. Partnership in DEIS Schools: A Survey of Home-School-Community Liaison Coordinators in Primary and Post-Primary Schools in Ireland. Dublin: Educational Research Centre.

- Young, R. A., S. K. Marshall, J. F. Domene, M. Graham, C. Logan, A. Zaidman-Zait, and C. M. Lee. 2008. “Transition to Adulthood as a Parent-Youth Project: Governance Transfer, Career Promotion, and Relational Processes.” Journal of Counseling Psychology 55 (3): 297–307.

- Zhu, S., S. Tse, S. H. Cheung, and D. Oyserman. 2014. “Will I get There? Effects of Parental Support on Children's Possible Selves.” British Journal of Educational Psychology 84 (3): 435–453.