ABSTRACT

Governments and other agencies seeking to tackle racism have been calling for better empirical evidence, including complaint data based on reports by people who have experienced racism. This approach requires much of those who face racism, often while offering little effective support or redress for them. There is a need to understand reporting or not reporting experiences of racism as a result of a complex interplay between different factors – as a (non-) reporting journey, rather than as a singular moment of decision. Reporting is at risk of remaining an ineffective strategy for responding to racism where the reporting pathways and support services are not sufficiently aligned with the expectations and needs of those who experience racism. This article discusses the findings of three place-based community engagement and research projects across four local municipalities in Melbourne. The projects examined locally specific community perspectives and expectations in relation to reporting pathways and support services for those experiencing racism. The analysis of this community input resulted in anti-racism roadmaps specific for each local area, which were co-developed with local communities.

Introduction

The empirical scholarship on racism is enormous and keeps growing. People who identify with a community affected by racism have been asked in countless surveys to share – and thus, in some ways, to relive – their experiences with racism, while an ever-increasing number of studies and systematic meta-studies (e.g. Paradies et al. Citation2015; Ben et al. Citation2023) examine racism from various angles. Today we know more about racism, its historic roots and evolution, its mechanisms and effects, its manifestations and its individual, collective, societal and economic consequences than ever before. However, while that research has been important in providing empirical evidence, the extensive scholarly attention does not seem to have sufficiently translated into effective ways to tackle racism. Many of those who face racism continue to feel unheard and disillusioned about the prospect of real change.

Racism itself has not diminished. In recent years, human rights agencies, community groups and academics have argued the COVID-19 pandemic has led to a global increase in racism – most conspicuously against people of Asian background, but also in antisemitism, Islamophobia and xenophobia (Human Rights Watch Citation2020; Australian Asian Alliance Citation2021; Pew Citation2021; Kamp et al. Citation2022; Huang et al. Citation2023). As the UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres stated in May 2020, ‘the pandemic continues to unleash a tsunami of hate and xenophobia, scapegoating and scare-mongering’ (UN Citation2020).

Public attention to ‘COVID-19 racism’ coincided with renewed global racial justice movements, notably including responses to the police murder of George Floyd in the US. In this context, shaped by global and local factors, many countries have seen a significant increase in the public awareness of interpersonal and structural racism as a persistent problem. Australia, where we have conducted the research for this article, is no exception. According to the Australia Talks survey in 2021, three quarters of Australians agreed that ‘there is still a lot of racism in Australia these days’ (Crabb Citation2021). The annual Mapping Social Cohesion study found that, in 2022, 61 per cent of survey respondents regarded racism as a ‘very big’ or ‘fairly big problem’ in Australia – a significant increase from 2020 when only 40 per cent expressed such a view (O’Donnell Citation2022: 69). In this climate of growing public reckoning in Australia, different stakeholders – from governments and law enforcement to human rights agencies – have focussed their attention on implementing effective ways to respond to racism. These include, among others, the development of a new national anti-racism framework by the Australian Human Rights Commission, a first-ever anti-racism strategy in the state of Victoria, planned or passed state legislative changes to (racial) vilification legislation, renewed emphasis on anti-racism support by the Victorian Equal Opportunity and Human Rights Commission, and public multilingual campaigns of law enforcement agencies in Victoria and New South Wales.

Efforts to increase reporting of racism constitute an important element of many of these initiatives. Acknowledging that racism is severely under-reported has prompted police to encourage those who have experienced racism to report it. Similarly, human rights commissions (e.g. AHRC Citation2020), governments (e.g. Victorian State Government Citation2021), and academics have also repeatedly highlighted the importance of reporting racism and of complaint data, often arguing that under-reporting contributes to a lack of empirical insights into how and where racism occurs, which hampers the development of more targeted anti-racism interventions.

The starting point for our research and the fundamental argument in this article is that, while these calls for increased reporting are well-intended and important, they tend to be shaped by the mandate of the external agencies instead of prioritising the expectations and support needs of those who have experienced racism. We do not suggest that both perspectives – more empirical data and stakeholders’ motives on the one hand and better support on the other – are mutually exclusive. To the contrary, one key premise of effective anti-racism in general is that there needs to be a multi-stakeholder commitment informed by robust and locally specific evidence. However, as we argue in this paper, the experiences, needs and expectations of those who face racism need to play a (more) central role in shaping anti-racism actions, delivered by various agencies and organisations (Wong and Christmann Citation2008; Myers and Lantz Citation2020).

This article discusses findings from three place-based community engagement and research projects across four Melbourne municipalities, examining the perspectives of people from local communities affected by racism in relation to (non-) reporting racism. Rather than only identifying reporting barriers as previous studies have done, we seek to make an original contribution by providing empirical insights into the interplay between personal experiences, motives and support needs, and the systemic factors that shape a person's journey towards reporting (or not reporting) or accessing support. We will further discuss how this research has been designed with a change-oriented rationale and commitment to centring community voices. This has informed the co-development of local anti-racism roadmaps, specific to the reporting and support needs of communities in each locality.

What we Know About (Under-)Reporting Racism: A Brief Overview

It is well established that racism often goes unreported. Many incidents of racist or other hate crimes (i.e. incidents that meet the criminal threshold) are often not brought to the attention of law enforcement or other relevant agencies. Research across the world has tried to quantify what Pezzella et al. (Citation2019) call ‘the dark figure of hate crime underreporting’. An overview of key findings is presented here.

Underreporting Racism and Racist Hate Crimes

One of the largest studies delivering robust empirical insights into these questions is the pan-European EU-MIDIS II survey among 25,515 ‘immigrants and ethnic minorities’, commissioned by the EU Fundamental Rights Agency (FRA Citation2017). Of those who experienced ‘discrimination because of their ethnic or immigrant background, as well as potentially related characteristics, such as skin colour and religion’ (p. 13), only 12 per cent reported the most recent incident to police, a human rights agency or the institution where the incident occurred (formal reporting). Indeed the reporting rate declined, compared to 18 per cent in a 2008 FRA study. The 2017 study identified large differences between ‘migrant or minority groups’ and between national contexts, with reporting rates ranges between 30 per cent to only 2 per cent. People of Sub-Saharan African or Turkish background, for example, reported discrimination more commonly than other groups, and reporting rates were also significantly higher in some countries (especially Sweden, Finland, Ireland and the Netherlands) than others (p. 42-49).

In contrast to this pan-European survey on racial and ethnic discrimination, various studies have focussed on hate crime (under-)reporting. Not surprisingly, racially motivated incidents above the criminal threshold are reported proportionally more often than those that may not constitute a crime. Nevertheless, under-reporting of racist hate crimes has also been identified as a significant problem. Referring to previous research (Herek et al. Citation1999; Sandholtz et al. Citation2013), Myers and Lantz (Citation2020) argue in their US and UK comparative study that ‘hate crimes are reported to the police less frequently than non-hate crimes’. This has also been confirmed in the Australia context (Wiedlitzka et al. Citation2018). Meanwhile, Myers and Lantz (Citation2020) found in the UK and the USA that 46 per cent of racist hate crimes were reported to authorities (see also Harlow Citation2005). Without specifying the under-reporting of hate crimes in the US, Pezzella et al. (Citation2019, 2–3) point to the enormous ‘magnitude of the difference between victim (NCVS) and police (UCR) accounts of hate crimes’. An analysis of America's National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS) showed ‘victims perceived bias-motivated victimizations on average of approximately 269,000 per year’ (2004–2012), however, the official Uniform Crime Report (UCR) counted only an average of 8770 hate crimes per year during this period.

Although the evidence is less robust in Australia, emerging research indicates that racist and/or hate-related incidents and crimes are significantly underreported here also (Mason et al. Citation2017). Vergani and Navarro (Citation2020) conducted an explorative survey of 260 Australians, most of them from diverse (non-white) ethnic, cultural and religious backgrounds. Their sample also includes people with a disability and people who identified as LGBTIQ+. They found that, while many respondents stated they would report certain hate-related incidents (reporting intention), only very few who experienced such situations actually did so. For example, only a minority (five out of 13) ‘reported being the victim of a violent physical attack’ and an even smaller proportion (13 out of 96) ‘had reported verbal abuse through any official avenue’. Another Australian study found even lower reporting rates. In a collaboration between the Centre for Multicultural Youth and the Australian National University, Doery et al. (Citation2020: 22) surveyed 376 young people (aged 15-26) from multicultural backgrounds in June 2020. Asked about their response to experiences of ‘discrimination or unfair treatment because of [their] ethnicity, cultural background, religion or immigration status’, only 6.3 per cent stated they formally reported it, 7.1 per cent spoke about it to their teacher or health professional, and 29.1 per cent told their friends or family. Almost six in ten ignored the incident entirely.

A recent survey among Asian-Australians confirms the issue of under-reporting, although it points to slightly higher reporting rates. Surveying 2003 self-identified Asian-Australians between late 2020 and early 2021, Kamp et al. (Citation2022: 34) found that 47.9 per cent had experienced racism prior to the COVID-19 pandemic and 39.9 per cent after January 2020. Asked whether they have reported any of these incidents, three out of ten stated they had never reported any of these experiences. This proportion fluctuated significantly depending on where the incident occurred – from 19 per cent never reporting racism that happened in a taxi/Uber, to 52.3 per cent never reporting incidents that happened in shops. Only a few respondents stated they had reported ‘all the time’ – between 1.9 per cent (public spaces) and 7.6 per cent (friend/family's home).

Reporting Barriers

Numerous studies have identified factors that discourage people from reporting racism or hate crimes. Vergani and Navarro (Citation2020, 12) identified and reviewed a total of 29 empirical studies, most of them from the UK but also from Australia and the US, that sought to identify ‘barriers to reporting hate crime’. Based on their review, which also includes hate crimes not related to racism (e.g. anti-LGBTIQ+), they developed a typology of internal and external barriers: ‘internalization’ and ‘lack of awareness’ (internal), and ‘fear of consequences’, ‘lack of trust in statutory agencies’, and ‘accessibility’ (external). These were further specified, as outlined in .

Table 1. Reporting barriers as identified in Vergani and Navarro (Citation2020)

Applying this typology to 260 survey responses in their Australian study, Vergani and Navarro (Citation2020: 31) concluded that internal barriers were more common in what the authors describe as ‘less serious incidents, such as rude gestures from teenagers or verbal assault’, while external barriers ‘were more likely to explain underreporting of more serious incidents, like assault or vandalism’. Moreover, prevalence of reporting barriers differed between different communities groups, although their survey sample was too small for any conclusive assessments (p. 33).

Other studies with larger samples have also generated empirical evidence on the barriers for reporting racism and ethnic/religious discrimination. The European EU-MIDIS II (FRA Citation2017: 49) survey found that among the most commonly mentioned reasons for not reporting racism was the personal sentiment that ‘nothing would change’ and that the incident was ‘too trivial’ or not ‘worth reporting’. Other barriers related to people's normalisation and acceptance of racism (‘it happens all the time’), not being able to provide the required evidence, not wanting ‘to cause trouble’ and concerns about negative consequences (secondary victimisation). It is worth noting that the main reasons for not reporting vary significantly between different migrant and minority groups and depend also on where the incident occurred. For example, the most frequent reason for not reporting racism to school authorities was related to people's concerns about negative consequences.

Not feeling confident that reporting would lead to a meaningful outcome or change is identified in several Australian studies (Doery et al. Citation2020; Kamp et al. Citation2022) as a key factor influencing reporting behaviour. Other identified barriers include concerns about negative repercussions, not knowing where to report, and feelings that the report would not be taken seriously or dealt with appropriately. Mason et al.'s (Citation2017: 91–96) research specifically on policing hate crime identified several factors that influenced the (non)reporting and recording of hate crimes, including different interpretations of terminology, ‘police-community trust’ and perceptions of ‘procedurally just practices’.

Overall, research has established a series of factors that may influence a person's decision to report (or not to report) an experience of racism. These factors often apply in significantly different ways depending on the severity of the incident (Wong and Christmann Citation2008) and the area of life where it occurred. In addition, while ethnic, cultural and religious groups not only differ in their inclination to report, their reporting behaviour is also influenced by a series of other factors. The interplay of factors that influence (non)reporting behaviours, however, has not been sufficiently explored, especially not in locally specific contexts. These insights underscore that reporting racism is highly complex – a personal journey guided by a constellation of various factors, rather than a singular decision.

The (non-) Reporting Journey

Myers and Lantz (Citation2020, 1035) stress the procedural nature – and many hurdles – of the reporting journey in the context of their study on racist hate crimes in the US and the UK. Drawing on previous research, they highlight a seemingly obvious but often under-appreciated dynamic. The victim of a hate crime ‘must first recognize they were the victim of a crime and then, also recognize that the crime was motivated by bias or prejudice’. Second, they must ‘decide to notify the police of the incident’. Third, the police must be aware of hate crime recording procedures. Fourth, police must ‘acknowledge and recognize the bias motivation’.

Emerging research has explored how those who experience racism respond, both through psychological strategies and actions – which may or may not include formal reporting. This qualitative scholarship has added important nuances to our understanding of the journey towards (non-) reporting racism. Ben’s (Citation2022) qualitative study within Melbourne's Eritrean community examined the issue of ‘downplaying racism’, identifying five reasons why participants refrained from reporting. The first reason is the difficulty of recognising racism and a related uncertainty as to whether a given incident constitutes racism. Second, some participants downplay their experiences with racism in Australia as they compare it to ‘other racisms’ (Ben Citation2022: 933), in particular more overt manifestations they faced in the past and in other national contexts. Compared to those harsher encounters with racism, experiences with often more subtle racism in Australia may be disregarded. Third, Ben found that a sense of ‘gratitude’ towards Australia as a country that has given them new opportunities encourages some to dismiss personal experiences with racism. Fourth, several participants emphasised meritocratic values and expressed a firm belief that those who work hard will succeed – racism and discrimination may exist and create barriers but on a personal level one can overcome these obstacles and still move up in life. The fifth reason for downplaying racism and not reporting it is related to participants’ desire to reject ‘narratives of powerlessness and victimhood’ (p. 936) as a way to claim agency and control.

To better understand the reporting journey, it is important to acknowledge that reporting is only one of many potential actions a person who experiences racism can take. A qualitative study among (mostly Black) people facing racism in Norway (Ellefsen et al. Citation2022: 442) differentiates between five typical ‘forms of resistance to racism’: deliberately ignoring, confronting and talking back, sharing with family or peers, reporting to authorities, and collectively protesting. For each of these five response types the researchers identify specific functions and potential positive and negative outcomes. The most common response among the study participants was to confront the perpetrator and talk back, while ‘participants rarely reported racism to authorities’. Meanwhile, as the authors argue, ‘reporting racism is often the modus operandi of public agents in antiracism initiatives and the preferred strategy of government, local municipalities and other authorities’. For the participants, however, formal reporting was seen as coming ‘at too great personal cost and seldom had positive outcomes’ (p. 449).

Overall, the existing evidence not only underscores the magnitude of under-reporting but also suggests that various external stakeholders which call on communities to formally report racism may underestimate the complexities of the (non-) reporting journey and the potential viability of, or individual preferences for, alternative responses to racism. Against this backdrop, we argue the perspectives, needs and agency of those experiencing racism deserve greater attention. That is where this article offers an empirical contribution.

Methodology: Place-based Community Survey and Focus Groups

The findings discussed in this article are based on data collected within three separate but similarly designed place-based community engagement and research projectsFootnote1 across four local municipalities in Melbourne's outer-southwest (Wyndham – WY), outer-north (Whittlesea – WH) and outer-southeast (a joint project in Casey and Greater Dandenong – CGD). Demographically, all these local areas are characterised by populations that are more culturally, ethnically and religiously diverse than is the case in most Australian municipalities – and increasingly so. The project combined traditional research methods with extensive community engagement, pursuing a change-oriented agenda.

The research was carried out on the unceded lands of the Wurundjeri, Bunurong and Wadawurrung peoples of the Kulin Nation. The three researchers and authors of this article are all settlers: Mario Peucker is of German background and immigrated to Australia in 2010; Tom Clark is of north-west European heritage and a descendant of clergy on the first fleet that proclaimed the colony of New South Wales in 1788; and Holly Claridge is of Lebanese and German background. We acknowledge the complicity of academia and our respective academic disciplines in colonisation and in systemic racism as well as our own unearned privileges. Eager to learn and to improve our practice around decolonising research, we share a deep commitment to centring the voices, experiences and knowledge of people with lived experience of racism, as well as an acknowledgment that communities with lived experience are not responsible for ‘fixing’ racism. We consider this process as an ongoing personal, professional and societal journey and are committed to learning from our own mistakes, by listening and by challenging whiteness as a default basis in academia and beyond.

The aim of the projects was to examine local perspectives and expectations in relation to reporting pathways and support services for those experiencing racism. Combining a survey and focus groups, each project captured the views of residents (aged 18+) of the respective municipalities who self-identified with any culturally, ethnically or religiously diverse (non-Anglo-Saxon) community or communities.Footnote2 Our understanding of ‘community’ is based on the definition as ‘networks of people tied together by solidarity, a shared identity and set of norms, that does not necessarily reside in a place’ (Bradshaw Citation2008: 5). Given the place-based nature of these projects, we refer in particular to those members of these various communities who live, work or spend a significant amount of time in the respective local municipality.

The surveys and the focus groups coincided with the COVID-19 pandemic; data collection took place during in Wyndham in 2020, in Whittlesea between mid-2021 and 2022, and in Casey and Greater Dandenong between late 2021 and 2022.

The Community Survey

The questionnaire encompassed closed and open-text questions, covering four themes:

Experiences with racism.

Reporting motives, barriers and experiences.

Support needs after experiencing racism.

Ways to improve reporting pathways and support services.

targeted and personal community engagement through formal and informal networks, established by the researchers and their project partners (a community organisation and three local councils and their community engagement units) with individuals, a variety of community organisations, grassroots groups and local networks, as well as service providers working with people from various ethnic, cultural and/or religious (non-Anglo-Saxon) backgrounds; and

use of public communication channels such as social media postings and publicly displayed flyers and posters at strategically selected locations (e.g. in local libraries and community hubs).

Due to this convenience sampling approach and sample size, the survey results are not statistically representative, but they afford exploratory quantitative insights. All responses were checked for validity leading to a total of 305 responses. These were descriptively analysed using Excel and Qualtrics.

Of these 305 respondents 73 per cent were women. Two-thirds were aged between 18 and 45, with 9.2 per cent between 18 and 25, 21.3 per cent between 26 and 35, and 36.1 per cent between 36 and 45. Almost 80 per cent of survey respondents answered the voluntary open-text question about their cultural, ethnic and religious identity. Respondents were from a diversity of backgrounds, with one third describing themselves as Muslims, often intersecting with other cultural or ethnic identities. Due to the often multifaceted, subjective (and non-mandatory) self-identification in the survey it is not possible to precisely quantify the sample in terms of respondents’ backgrounds. Our analysis of this open-text category showed that the sample included significant numbers of people from South Asia (e.g. Afghanistan, Pakistan, India, Sri Lanka, Nepal; approx. 55) and other parts of Asia (e.g. Burma/Myanmar, Cambodia, China, approx. 40), from the Middle East (e.g. Palestine, Lebanon, Syria, Iraq, Egypt; approx. 30), as well as various African backgrounds (e.g. South Sudan, Ethiopian; approx. 25) and from Pasifika communities (e.g. Tonga, Samoa, Māori, approx. 20). A smaller number was from South American or southern European background. Eight respondents identified as Aboriginal.

Focus Groups

We held 25 focus groups with residents who identified with a culturally, ethnically, religiously diverse (non-Anglo-Saxon) or Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander community. The focus groups, which discussed the same four thematic areas as the survey, were organised and led by peer facilitators. Facilitators were from the respective local area, identified themselves as being from a community affected by racism (except for one facilitator) and held positions of trust among their participants. After they participated in a training session preparing them for the role as facilitators, they organised ‘their’ focus group with typically five or six participants in a way that ensured a high level of cultural safety and confidentiality. The recruitment of focus group participants was usually based on the facilitators’ networks and relationships with members of various communities. Facilitators were paid for their time and received a certificate of appreciation. Each focus group participant received a gift voucher.

While most focus groups were held in English, some were conducted in community languages (e.g. Burmese, Chinese, Farsi, Urdu). Most of them were audio-recorded; where this was not possible, extensive notes were taken. For groups held in a community language, the facilitators provided either a written summary report in English or took notes that were shared and discussed with the project team. The collected data was analysed according to the four thematic areas.

A total of 127 people participated in the focus groups across the four municipalities. Many groups comprised members from one particular cultural, ethnic or religious community (e.g. Muslims, Burmese, Chinese, Pasifika, Aboriginal peoples), others were multicultural, and some of them brought together specific groups (e.g. young people, recent arrivals). Many groups were gender-mixed, others women-only or men-only.

Findings and Outcomes: Experiences with Racism, Reporting and Support Needs

This section presents selected findings from our quantitative-qualitative analysis of the survey and focus groups. Following an overview on participants’ experiences with racism and how their understanding of racism influences the reporting journey, we discuss their motivations for reporting, reporting barriers and their support needs, as well as their perspectives on how support services could be more responsive. Note that this article offers findings that span the four municipalities involved.

Experiences of Racism and Effects on the Reporting Journey

Across the three surveys, 63.1 per cent of female and 54.4 per cent of male respondents (average 61.3 per cent) stated that they, or someone from their household, had experienced racism in the previous 12 months. Almost eight out of ten respondents (78.9 per cent) had faced racism within their local municipality in the past. Of those who had experienced racism, 17.2 per cent stated it happens frequently, 37.6 per cent sometimes; 33.9 per cent once or twice; the remaining 11.3 per cent described the frequency in their own words and in a way that could not be clearly assigned to these categories. Our focus group analysis identified that the perceived frequency of experiences with racism ranged widely – some stated they have never experienced racism but have witnessed it and others described racism as an ‘everyday thing’ (WH 3), which they face ‘all the time’ (CGD 3). ‘This happens 100 times a day, but people [in our community] don't talk about it’, said one participant (WY 1).

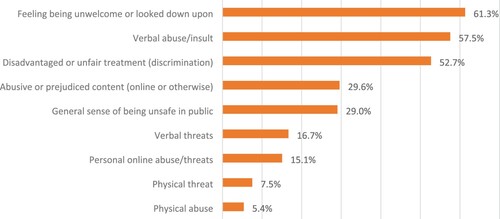

Participants experienced racism across all areas of life. Public spaces, including shopping centres (50.6 per cent), public transport (40.9 per cent) and in the street or in parks (33.5 per cent), were mentioned most often. This was followed by employment (48.3 per cent), education/schools settings (39.8 per cent), on social media (35.2 per cent), in health care (25.0 per cent), in the context of media reporting (23.3 per cent) and when encountering police (15.3 per cent). These experiences ranged from systemic and institutionalised manifestations (which were discussed in particular in the focus groups) and microaggressions, to verbal insults and physical abuse. A majority of survey respondents have faced microaggressions, which made them feel unwelcome and denigrated (61.3 per cent), and many also experienced racist verbal abuse and insults (57.5 per cent) and unfair, disadvantaged treatment (discrimination; 52.7 per cent) because of their cultural, ethnic or religious background. A smaller but notable proportion experienced verbal or physical threats and in some cases even physical abuse ().

The analysis of the open text responses and the focus groups highlighted that participants operated with very different notions of racism and that many were often unsure as to whether an incident was racist or not. ‘Is this just because they don't like me or is it racism’, one focus group participant asked (CGD 1). These factors not only raise questions about the methodological validity of survey questions on personal experiences with racism, but they can also crucially affect the (non-) reporting journey. Some participants were highly attuned to the complexity and subtlety of racism, pointing to frequent exposure to so-called microaggressions (Williams et al. Citation2021) and systemic racism. Others were reluctant to use the term ‘racism’, confining it to more blatant manifestations. Several focus group participants alluded to these divergences in the perceptions of racism, some arguing ‘there is no awareness in the community about racism at all, although it is existing at a very large scale’ (CGD 3).

Resonating with Ben’s (Citation2022) study among Eritrean-Australians, we identified a range of reasons why people either do not recognise racism or choose not to actively respond to it. Some who migrated to Australia themselves were worried they would appear ungrateful for the opportunities they felt Australia offers if they spoke out about racism. ‘Some people just ignore [racism], they feel they need to be grateful for being here in Australia’ (CGD 8). Others were concerned that reporting would negatively impact on their chances to achieve their personal aspirations. This relates to what Ben (Citation2022) described as beliefs in meritocratic values but is also linked to concerns about secondary victimisation. A focus group participant recalled how she had frequently experienced racism at school but her mother had advised her to endure it if ‘you want to chase your goals, … if you want to be strong and independent’. She explained:

I stepped on every feeling that I had … I have to face racism, I have to face people judging me and keep it in my heart as much as I can until I pass those two years, Year 11 and 12 [in high school], and just get over it. And I did. (WY2)

Other factors contributing to participants’ tendency to not recognise or ignore racism included the often-concealed nature of racism (e.g. discrimination in employment), as well as the structural and systemic nature of racism. A survey respondent stated:

Racism is a systemic issue, and not a personal or isolated issue. Racism, prejudice and discrimination is as much ingrained in institutions like the judicial systems, police, employment and education, and is usually carried out by people, who are only relaying the messages and ideas reinforced on large scale media platforms …

We know that racism is systemic, so the last thing we want to do is tap into an organisation that follows those structures. I think that's why we don't report because that level of trust is just not there, because those systems keep imposing those same traumas over and over again.

Reporting Racism

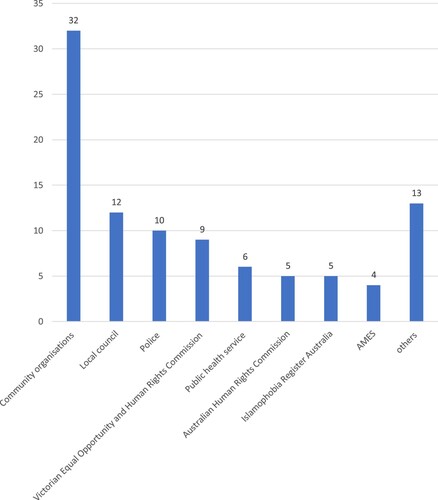

16.3 per cent of survey respondents stated that they had formally reported an experience of racism to an organisation; just over half (51.4 per cent) only ever told family or friends; the remaining 32.3 per cent never told anyone. Of those who reported to an organisation, few had reported to police or to a specialised agency (e.g. state or federal human rights commission) with a mandate to record and respond to complaints of racism. Instead, an overwhelming majority reported to community organisations, and some to their local council (). It is plausible to assume that this reporting pattern was in parts due to the recruitment of survey participants also through existing community networks of councils and certain community organisations. It is important to note that in most cases, these community organisations and local councils are not set up to provide specialised anti-racism support.

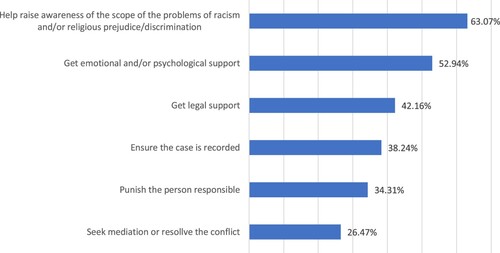

While the number of those who had reported was small, the accounts of their reporting experiences are noteworthy. Among those survey respondents who had formally reported, 82.9 per cent agreed or strongly agreed that they felt better after reporting the incident, which suggests the potentially positive effect of speaking out against and reporting racism. This is despite the fact that less than half of them (46.2 per cent) also stated they had received the support they were hoping for (possibly partially attributed to the choice of organisation they reported to), and two-thirds felt they had to prove that the incident was a form of racism. Crucially, 56.1 per cent stated that their reporting experience made it less likely they would report a similar incident again in the future. We interpret these mixed sentiments expressed in the survey as an indicator that the act of speaking out itself during the reporting process has overall positive emotional effects on many, this may be explained by their advocacy-related reporting motive of raising awareness of racism (see below, ). However, individuals’ positive emotions were often outweighed by their disappointment and dissatisfaction with the reporting procedures and the outcomes of the process.

The focus group discussions confirmed this. Many participants said their previous experiences with reporting racism to police, their employers or other agencies had been so unsatisfactory that they would refrain from reporting again. One participant stated:

We have clear policies and procedures at my workplace to report racism related incidents, but I haven't seen any positive outcome after the inquiries. These kinds of practices discourage employees to make a complaint when racism happens (CGD 2).

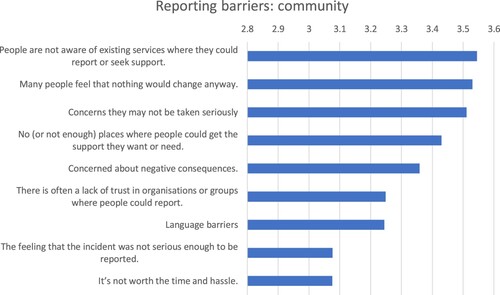

The deterrent effect of previous reporting experiences constitutes one of many reporting barriers; and our analysis identified several other barriers, largely confirming what earlier research has found (for an overview, see Vergani and Navarro Citation2020). We asked about reporting barriers from two perspectives: first, respondents’ views on why others in their community refrain from reporting; second, their personal reasons for not reporting. As the following paragraphs show, there was a consistency of discussion across the two perspectives. The most common factors, from the perspective of survey respondents, for non-reporting in their community () were related to limited awareness of existing services, the view that reporting would not lead to any changes, and concerns that their report would not be taken seriously. Other reasons included a lack of support services, concerns about negative consequences, low levels of trust in organisations that provide services, and language barriers.

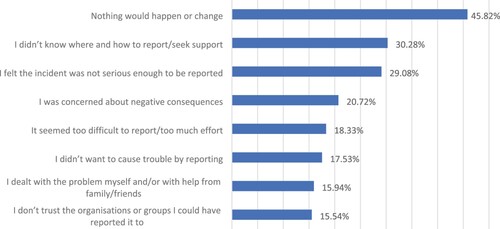

The analysis of survey respondents’ main personal reasons for not reporting racism paints a similar picture (). Almost half of them (45.8 per cent) shared the sentiment that ‘nothing would happen or change’ as a result of reporting. Three out of ten did not know how and where to report and seek support (30.3 per cent) and felt that the incident was not serious enough (29.1 per cent). As one focus group participant put it: ‘We can't make a complaint every day. To whom should you complain?’ (WH2). Concerns about negative consequences were mentioned by 20.7 per cent; this included, among others, fears that reporting could have negative repercussions for their legal status. ‘If I do that [reporting], it may affect my visa’, as one participant shared (WY2), and others pointed to their prospect of obtaining Australian citizenship. Around one in six respondents did not report because they found the reporting process too difficult (18.3 per cent), did not want to cause trouble (17.5 per cent) or did not trust the organisation they could have reported to (15.5 per cent) (provided they were aware of such an organisation).

Another significant barrier to reporting relates to widespread perceptions that they would need to provide evidence of their experience. This was stressed by several focus group participants. As proving the racist incidents was often seen as impossible or very difficult, they chose not to report at all. Many explained that they usually do not know the perpetrator, especially when it happens in public places, and that they have no witnesses or any evidence especially when it happens covertly (e.g. discriminatory recruitment decisions). ‘It is literally impossible to prove, and there is no formal encouragement to report, we have other important things to do so we just swallow it and move on’, as one focus group participant stated (CGD 4).

In most cases, participants indicated that several factors were simultaneously at play, discouraging them from reporting. The analysis of the focus groups, for example, showed that some were initially determined to report an incident of racism but considered the police their only option – unaware of other agencies that may have been better suited in the particular instance. The experience of reporting to police therefore becomes a negative experience with unsatisfactory outcomes and as such may increase their inclination to not report any incident of racism in the future.

What motivates someone to report racism? What kind of response or support would they hope to receive? Finding answers to these questions is key to developing more adequate reporting and support services tailored to different community expectations. Among those few (n = 43) who had formally reported racism themselves, the majority were driven by the motivation to contribute to change (‘If no one reports, nothing will ever change’; n = 26), and the desire to ‘make sure the incident does not go unrecorded’ (n = 21) as well as by their desire to simply ‘talk to someone about it’ (n = 26). Other less common factors included the intention to seek legal advice (n = 16), ‘punishing’ the person responsible (n = 11) and/or getting emotional/psychological support (n = 8).

Asking all survey respondents about what they consider the main reasons for people in their community to report racism, the findings () confirm that raising awareness of the persistence of racism was the most common purpose, with almost two-thirds regarding this as a key reason for reporting (63.1 per cent). More than half believed that getting emotional/psychological support was important for many who have experienced racism (although this seemed to apply less to themselves, see above). Around four in ten thought people would report to get legal support (42.16 per cent) and/or to ensure the incident is recorded (38.24 per cent), while ‘punishing the person responsible’ (34.31 per cent) and ‘seeking mediation or resolving the conflict’ (26.47 per cent) were mentioned by slightly fewer participants.

Our analysis indicates that most participants did not think that reporting would generally meet these expectations. As our analysis has shown, for example, participants were often sceptical that their report would contribute to change or to raising awareness of racism and did not feel they would receive adequate support when reporting. The perceived unsuitability of reporting pathways and procedures – or in some cases, previous experiencing with reporting – significantly deters many from reporting racism.

Community Perspectives: How to Encourage More Reporting

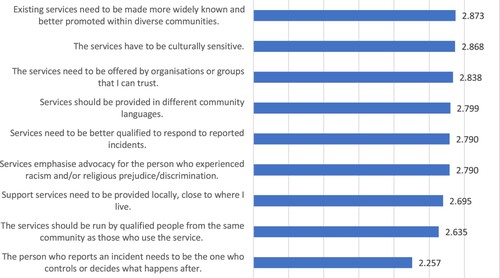

Only around one quarter of survey respondents agreed or strongly agreed that there were enough services that offer appropriate support for people from their local area who experience racism; 36.4 per cent disagreed or strongly disagreed and 25.8 per cent were not sure, possibly reflecting a low level of knowledge about such services. This latter interpretation is supported by the fact that the most commonly shared view among survey participants on how to encourage more reporting of racism was to make existing support services more widely known in their communities. Almost all respondents agreed with that statement with a median approval score of 2.873 (3.0 would mean that all respondents consider it ‘very important’) (). Similarly important to respondents was that anti-racism support services needed to be culturally sensitive (2.868), offered in different community languages (2.799) and provided by an organisation that people can trust (2.838). In addition, the support services should be better qualified, they should be provided locally, and these services need to offer advocacy for the person who has experienced racism.

The qualitative analysis of the focus groups and the open text sections in the survey offered further insights into what communities regarded as adequate anti-racism support and what would encourage more people to report. Many called for greater efforts to promote existing reporting pathways and support options, but most also expressed the view there are significant gaps in the existing service landscape. The findings highlight that participants wanted these gaps filled by community-led support, provided by trusted organisations that are both culturally and geographically accessible and can take a strong advocacy-oriented approach in their support. A survey respondent's comment captures the views of many others:

[We need] to have a place which is solely related to racism, that is warm and welcoming, with friendly, helpful staff, who genuinely care, and who follow through with the victim by staying in contact with them and update them with what has happened with their case, and the changes/results/outcome.

Resonating with the expected emphasis on advocacy, as articulated in the survey responses, many focus group participants stressed the importance of empathetic listening and understanding instead of having to comply with bureaucratic processes: ‘They should hear us. A person with responsibility should at least hear us, should give sympathy’ (CGD5), one focus group participant said. Another believed, ‘There needs to be someone who is hearing us and available with support services on the local level’ (CGD7).

Towards Local Anti-racism Roadmaps

In the focus groups, participants discussed specifically which (local) organisations would enjoy trust within significant segments of their communities, while the survey contained a locally specific section where respondents could indicate which local organisations they consider particularly well-suited to provide support to those who have experienced racism. These insights, together with all the other community input, informed a process of collaboratively developing locally specific anti-racism ‘roadmaps’ for each area – a recommended set of practical actions to improve anti-racism reporting pathways and support services in line with the expectations of various segments of local communities. These roadmaps are not the principal theme of this article, which is focused on ‘the (non-) reporting journey’, however they were outcomes sought by the partner organisations that supported these projects.

The three local roadmaps are distinctive, insofar as each is tailored to specific input from various sections of local communities and the organisational landscape and capacities in the respective municipalities. However, all included two core recommendations:

| 1. | An expansion of racial literacy in the community (e.g. what is racism, what are my rights, what support is available?). | ||||

| 2. | The establishment of a local anti-racism support network. | ||||

Concluding Discussion

Formally reporting racism is one of many possible actions in response to experiences with racism. Deploying the concept of reporting journeys draws attention to the complex interplay between the personal and structural factors that influence these processes, which may or may not lead to reporting. Our research confirms a number of reporting barriers as identified in previous studies (Vergani and Navarro Citation2020), but it goes beyond the existing scholarship by providing deeper empirical insights into how these barriers manifest and sometimes interact and shape a complex, multifaceted reporting journey. While the research was primarily aimed to provide an empirical basis for change-oriented local anti-racism roadmaps, the findings also make significant scholarly contributions. We identified specific motives that encourage individuals to report, the goals they pursue, the support they seek after experiencing racism, who should provide this support and how they should do it. These are vital contributions to better understanding the underreporting of racism. Importantly, it also helps enable practical actions to improve reporting pathways and anti-racism support services tailored to the specific needs of local communities that are affected by racism.

Our analysis showed that speaking out against racism and reporting experiencing with racism can have positive emotional effects on the individual. Calls to report racism can be an important encouragement for communities, but only if reporting pathways and procedures are aligned with community expectations, lead to more satisfactory outcomes for the individual and are connected to the anti-racism support that different segments of the local communities need. Otherwise, calling on those who face racism to report may not only remain ineffective; it may also draw individuals into disempowering processes that require individuals to invest a lot of time, effort and emotional labour and offer little in return. Doing so may place an additional burden on those who already face racism. It may even lead, implicitly and unintentionally, to a situation where those who choose not to report may feel responsible for the lack of data on racism – and, by extension, for inadequate anti-racism interventions.

The design and implementation of these place-based projects were intended to afford locally specific evidence to support changes in the reporting pathways and support services available to those experiencing racism. Community voices were – and needed to be – at the centre of the projects: it was crucial not merely to consult with communities, but to be guided by their expertise and input – to engage in a genuine, respectful partnership. We are not the judges of whether we have succeeded in this. This principle of centering community voices has informed all three projects, and the participants have frequently remarked on it as grounds for their engagement and support.

There are structural and systemic challenges for such partnership-based engagement. Despite the crucial role of community expertise, the funding for such research is not only generally limited but the bulk of it also tends to go to research institutes and universities (like ours) rather than to community organisations. This mandates long-term efforts to recalibrate funding models and grant procedures in anti-racism research (Fleming et al. Citation2023), as well as respectful and transparent engagement with communities. Specifics might include (remunerated) roles of influence and decision-making within the research for community members (e.g. genuine co-design, peer-facilitation with high levels of autonomy). However, the emphasis on active involvement of communities must not shift the responsibilities for the project's successful outcome or, more broadly, for effectively tackling racism onto communities. That onus remains squarely within the institutions and people who have historically and continuously been complicit in, shaped by and benefitted from racial hierarchies and injustices. Against this backdrop, for anti-racism to be effective it requires concerted efforts from a wide range of stakeholders, maintaining the responsibility and commitment to work jointly towards change, whilst centring the expertise of those with lived experiences.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Each of these projects received Ethics approval from Victoria University's Human Ethics Committee (HRE19-165; HRE21-065 and HRE21-118).

2 While this also included Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander (Indigenous) communities, we acknowledge that racism against Indigenous peoples is significantly different to racism targeting non-Indigenous communities.

In relation to the labels used in this work to refer to communities affected by racism, we further acknowledge that, as Achille Mbembe (Citation2017, 10) stated, ‘we can speak of race (or racism) only in fatally imperfect language’ and that race is ‘at once real and fictive’. Ultimately, we sought to include the voices of all those who identify with a community affected by racism in all its manifestations (including systemic racism); the applied understanding racism followed their subjective perspectives and was not limited by any pre-defined, externally imposed definitions.

References

- Australian Asian Alliance. 2021. Covid-19 Racism Incident Report Survey Comprehensive Report 2021. Available from: https://asianaustralianalliance.net/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Comprehensive-AAA-Report.pdf [Accessed 3 April 2023].

- Australian Human Rights Commission (AHRC). 2020. Where’s all the data on COVID-19 racism? Available from: https://humanrights.gov.au/about/news/opinions/wheres-all-data-covid-19-racism [Accessed 3 April 2023].

- Ben, J., 2022. “People love talking about racism”: downplaying discrimination, and challenges to anti-racism among Eritrean migrants in Australia. Ethnic and racial studies, 46 (5), 921–943.

- Ben, J., et al., 2023. Racism data in Australia: A review of quantitative studies and directions for future research. Journal of intercultural studies, 1–30. DOI:10.1080/07256868.2023.2254725

- Bradshaw, T.K., 2008. The post-place community: contributions to the debate about the definition of community. Community development, 39 (1), 5–16.

- Crabb, A. 2021. Australia Talks shows we agree there’s a lot of racism here, but less than half say white supremacy is ingrained in our society, ABC. Available from: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-05-31/annabel-crabb-analysis-racism-australia-talks/100172288 [Accessed 3 April 2023].

- Doery, K., et al., 2020. Hidden Cost: Young Multicultural Victorians and COVID-19. Melbourne: Centre for Multicultural Youth.

- Ellefsen, R., Banafsheh, A., and Sandberg, S., 2022. Resisting racism in everyday life: From ignoring to confrontation and protest. Ethnic and racial studies, 45 (16), 435–457.

- European Union Fundamental Rights Agency (FRA). 2017. EU-MIDIS II: Second European Union Minorities and Discrimination Survey. Available from: https://fra.europa.eu/sites/default/files/fra_uploads/fra-2017-eu-midis-ii-main-results_en.pdf [Accessed 3 April 2023].

- Fleming, P.J., et al., 2023. Antiracism and community-based participatory research: synergies, challenges, and opportunities. American journal of public health, 113 (1), 70–78.

- Harlow, C.W. 2005. Hate Crime Reported by Victims and Police. Bureau of Justice Statistics Special Report, U.S. Department of Justice. Available from: https://www.prisonpolicy.org/scans/bjs/hcrvp.pdf [Accessed 3 April 2023].

- Herek, G.M., Gillis, J.R., and Cogan, J.C., 1999. Psychological sequelae of hate-crime victimization among lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology, 67, 945–951.

- Huang, J.T., et al., 2023. The cost of anti-Asian racism during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nature human behavior, 7, 682–695. DOI:10.1038/s41562-022-01493-6

- Human Rights Watch. 2020. Covid-19 fueling anti-Asian racism and xenophobia worldwide. Available from: https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/05/12/covid-19-fueling-anti-asian-racism-and-xenophobia-worldwide [Accessed 3 April 2023].

- Kamp, A., et al., 2022. Asian Australians’ Experiences Of Racism During The COVID-19 Pandemic. Melbourne: Centre for Resilient and Inclusive Societies.

- Mason, G., et al., 2017. Policing Hate Crime: Understanding Communities and Prejudice. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.

- Mbembe, A., 2017. Critique of Black Reason. Durham/London: Duke University Press.

- Myers, W., and Lantz, B., 2020. Reporting racist hate crime victimization to the police in the United States and the United Kingdom: A cross-national comparison. The British journal of criminology, 60 (4), 1034–1055.

- O’Donnell, J. 2022. Mapping social cohesion 2022, Scanlon Foundation Research Institute. Available from: https://scanloninstitute.org.au/sites/default/files/2022-11/MSC%202022_Report.pdf [Accessed 3 April 2023].

- Paradies, Y., et al., 2015. Racism as a determinant of health: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLos One, 10 (9), 1–48.

- Pew Research Centre (PEW). 2021. One-third of Asian Americans fear threats, physical attacks and most say violence against them is rising. Available from: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2021/04/21/one-third-of-asian-americans-fear-threats-physical-attacks-and-most-say-violence-against-them-is-rising/ [Accessed 3 April 2023].

- Pezzella, F.S., Fetzer, M.D., and Kelle, T., 2019. The dark figure of hate crime underreporting. American behavioral scientist, 1–24. DOI:10.1177/0002764218823844

- Sandholtz, N., Langton, L., and Planty, M. 2013. Hate Crime Victimization, 2003–2011 (Report No. NCJ 241291). Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics.

- United Nations. 2020. Secretary-General Denounces ‘Tsunami’ of Xenophobia Unleashed amid COVID-19, Calling for All-Out Effort against Hate Speech, SG/SM/20076 (8 May). Available from: https://press.un.org/en/2020/sgsm20076.doc.htm [Accessed 3 April 2023].

- Vergani, M., and Navarro, C. 2020. Barriers to Reporting Hate Crime and Hate Incidents in Victoria. CRIS: Melbourne.

- Victorian Government. 2021. Victorian government response into anti-vilification protections. Available from: https://www.vic.gov.au/response-inquiry-anti-vilification-protections [Accessed 3 April 2023].

- Wiedlitzka, S., et al., 2018. Perceptions of police legitimacy and citizen decisions to report hate crime incidents in Australia. International journal for crime justice and social democracy, 7 (2), 91–106.

- Williams, M.T., Skinta, M.D., and Martin-Willett, R., 2021. After pierce and Sue: A revised racial microaggressions taxonomy. Perspectives on psychological science, 16 (5), 991–1007.

- Wong, K., and Christmann, K., 2008. The role of victim decision-making in reporting of hate crimes. Community safety journal, 7 (2), 19–35.