ABSTRACT

With the growing trend of globalisation and the internationalisation of higher education, China actively recruits more international students to study at Chinese universities. Notably, international doctoral students are a significant cohort in this trend. Although many studies have investigated international students’ learning experiences in China, few have explored their motivations to pursue doctoral degrees in China. To fill this gap, through the push–pull model, we explored the motivation of 55 international doctoral students from three Chinese universities. The findings show that various national, institutional, and individual factors comprehensively influenced their choice to pursue doctoral studies in Chinese universities. Their experiences also reflect that China is progressively establishing a systematic mechanism to attract international doctoral students by taking advantage of economic development and Chinese academic returnees. While these advantages attract international doctoral students to study in China, Chinese universities may still play an alternative role in international doctoral education. This study contributes to international higher education and doctoral education. Implications and suggestions for future studies are discussed.

Introduction

Understanding international students’ motivation to study abroad has become an important research topic in international higher education (HE). Many studies (e.g., Dai, Citation2021; Zhou, Citation2014, Citation2015) have explored students’ transitions from developing (e.g., China, Malaysia, and Vietnam) to developed countries (e.g., the USA, the UK, and Canada). Recently, a growing number of studies have paid attention to international students’ issues (e.g., motivation, learning, and adjustment) in developing countries, for example, China. As a traditional origin country notable for its high number of outbound students, China has attempted to attract more international students to improve HE competitiveness (Ma, Citation2017). Notably, Shen et al. (Citation2016) advocate that it is essential to recruit more international postgraduate students to conduct research-based studies in China, which could diversify the source of knowledge creation and improve the global competitiveness of Chinese HE.

Postgraduate research students, especially at the doctoral level, are a substantial part of the modern HE system, reflecting the quality of HE in a country (Shen et al., Citation2016; Shin et al., Citation2018). Thus, many Chinese universities plan to recruit more international students, especially high-level doctoral students. However, the factors that motivate international doctoral students to choose China as a learning destination remain under-researched. Hence, this study aims to investigate those factors.

With this research goal, we conduct a qualitative exploratory study to investigate influentical factors based on the ‘push–pull’ model (e.g., Mazzarol & Soutar, Citation2002; Li & Bray, Citation2007; Wen & Hu, Citation2019; Wu et al., Citation2021). In the following sections, we first review the research on international students’ motivation to study abroad, followed by an overview of international doctoral education in China. The research gap is then identified, along with an illustration of the significance of this study. Next, we critically analyse the push–pull model to explore potential factors in this study. Then, we introduce the research methods. Finally, findings and implications are presented, followed by a concluding remark.

International students’ motivation to study abroad

International education constitutes the foundation of international student mobility. This mobility usually flows vertically (i.e., towards economically and academically more advanced systems), or horizontally (i.e., between countries of more or less equal academic quality) (Kehm & Teichler, Citation2007). Specifically, studies have investigated doctoral students’ motivation to conduct vertical mobility from developing to developed countries. In pursuing the US doctoral education, students are interested in research, teaching, and the high utility of a US-earned degree (Zhou, Citation2015). Similarly, for Chinese students attending Australian doctoral education, research enthusiasm and enriching life experiences are key drivers (Yang et al., Citation2018). Supervisor reputation and potential collaboration between home and host institutions are also considered essential (Li et al., Citation2021). These findings reveal that opportunities for advanced research development are significant motivations for seeking degrees in more developed host countries (Zhou, Citation2015).

Although horizontal student mobility regarding doctoral education has been rarely discussed in recent literature, some studies have investigated student motivation and learning experience (e.g., Ahmad & Shah, Citation2018; Dai & Hardy, Citation2022; Dai & Hardy, Citation2023; Ding, Citation2016; Ma, Citation2017; Wen & Hu, Citation2019) in developing countries. For instance, Ding (Citation2016) found that Chinese language and China’s economic development attract international students. Similar findings identified by Ma (Citation2017), suggest that ‘an optimistic belief in China’s future development was a critical factor in almost every participant’s decision to study in China’ (p. 569). More recently, Gbollie and Gong (Citation2020) surveyed 537 international students in Chinese universities and found that visa and programme policies, and citizens’ welcoming attitude attract students to China. Compared to more developed countries, China’s visa policies appear to be less stringent (Gopal, Citation2016).

In line with Ma’s (Citation2017) study, Wen and Hu (Citation2019) indicate that China’s HE quality is advanced to some extent, as reflected by its universities’ global ranking – a vital pull factor. Moreover, Ahmad and Shah (Citation2018) suggest that the academic environment in Chinese universities draws international students. Meanwhile push factors include recommendations by close contacts, lack of high-quality education and development opportunities in the home country. In sum, internal and external factors influence international students’ destination choices, and their mobility to China can be both vertical and horizontal (Wu et al., Citation2021).

Paulino and Castaño (Citation2019) summarise that ‘personal, cultural, economic, social, legal, political, environmental, and institutional factors systematically influence students’ motivations to choose their learning destinations’ (p. 142). While study abroad motivation has been researched at undergraduate and postgraduate levels (e.g., Bodycott, Citation2009; Maringe & Carter, Citation2007), recent studies are seeking to understand factors influencing doctoral students’ destination choices (e.g., Li et al., Citation2021). As the review illustrates, while many studies have explored motivation-related topics, few have specifically investigated international doctoral students’ motivation to attend Chinese HE. To fill this gap, we propose the following research question: What factors motivate international students to pursue doctoral research in China?

International doctoral education in China

In the last few years, China has seen a rapid increase in the amount of international students studying at Chinese universities. In 2018, China attracted 492,185 international students from 196 countries (MOE, Citation2019). Among this cohort, most came from Asia (59.95%), followed by Africa (16.57%), Europe (14.96%), Americas (7.26%), and Oceania (1.27%). By 2020, China ranked fourth globally in international student recruitment right after the US (1,075,496), UK (551,495), and Canada (503,270) (IIE, Citation2020).

The number of international doctoral students in China within the last two decades has risen significantly. In 2003, there were only 1,637 international students pursuing doctoral education in China. By 2018, this number had risen to 25,618 (MOE, Citation2004, Citation2019). The growing number of doctoral students in China indicates the country’s emerging role in global talent production. In 2015, the Chinese government initiated the ‘Double World-Class’ project and began making substantial investments for universities to establish high-level research with the goal of building a world-class HE system (Ma & Zhao, Citation2018).

China’s doctoral education system comprises of approximately 800 postgraduate institutions and has issued over 600,000 doctoral degree certificates in the recent decade. According to Bao et al. (Citation2018), China is the largest producer of doctoral degrees worldwide. This productivity and increase in students are strongly backed by national strategic development plans such as the Study in China Plan (SiCP) and governmental support towards internationalisation (Li & Xue, Citation2022). As China seeks to expand its internationalisation of HE, attracting international students is important and part of its internationalisation ethos (Ma & Zhao, Citation2018). With the domestic advancements in doctoral education and HE internationalisation, international students have indeed become more attracted to China as a study destination and educational hub (Glass & Cruz, Citation2022; Wen & Hu, Citation2019).

Theoretical lens: push–pull model

Researchers (e.g., Altbach, Citation1998; Mazzarol & Soutar, Citation2002) have attempted to develop a push–pull model to study the influencing factors of student mobility. Altbach (Citation1998) investigated international student mobility by using the push–pull model and found that some students were pushed by unfavourable conditions in home countries while being pulled by opportunities in host countries. Similarly, Mazzarol and Soutar (Citation2002) indicate that the lack of study opportunities in the home country, and the desire for a different experience pushes students to move abroad. Pull factors were found to be the reputation/quality of HE, possible immigration, and post-graduation job opportunities in the host country. However, there are some limitations to the push–pull framework. Traditionally, many studies on motivation have applied push–pull from a macro perspective, focusing on external factors such as social, political, and economic factors (Altbach, Citation2003; Knight, Citation2004). Micro-level push–pull elements which concern student subjectivity in the decision-making process have been overlooked. As Teichler (Citation2004) points out, personal characteristics (e.g., gender, age, academic ability) are essential for analysing student mobility. Thus, some scholars propose that research should explore internal and external factors, to deepen the understanding of students’ destination choices (Findlay et al., Citation2012).

In addition, some researchers (e.g., Findlay et al., Citation2012) have modified the push–pull model by focusing on the relationship between factors/forces, which in previous studies (Altbach, Citation1998) always conceived push force as existent only in home countries and pull force only in host countries. However, both home and host countries can simultaneously accommodate a series of push and pull factors that engage students in a dialectic process of decision-making. As Li and Bray (Citation2007) suggest, ‘the positive forces at home and negative forces abroad can be called reverse push-pull factors’ (p. 795). In other words, origin countries may have ‘pull’ forces to attract students, while destination countries may also include ‘push’ forces that discourage international students from studying there (Findlay et al., Citation2012).

Moreover, push–pull forces not only exist between home and host countries but also in the global educational and economic scenario where students compare the pull factors of different destinations. As reviewed previously, international student mobility in Chinese HE is not singularly vertical or horizontal, given China’s status as an emerging educational hub. Scholars have therefore advocated the integration of macro and micro factors and explored the competing forces between the factors to understand mobility (Wen & Hu, Citation2019). The current study follows this rationale by adopting the push–pull model to explore how different factors across several levels stimulate international students to pursue doctoral research in China.

Research design

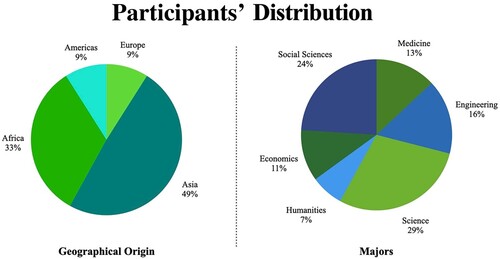

The purpose of this qualitative exploratory study is to understand the motivations of international doctoral students to study in the Chinese HE context. As qualitative researchers, we believe that participants are subjectively different due to learning, life experiences, and worldviews (Merriam, Citation2009). Purposeful and snowball sampling methods were used to recruit participants as these approaches allowed us to focus on the key cohort and recruit more participants through their networks. Finally, a total of 55 participants from three research-intensive Chinese universities in Beijing (University A), Shandong (University B), and Guangdong (University C) voluntarily participated in this study. These universities were chosen as they are considered to be ‘Double-First Class’Footnote1 universities in their region and representative study destinations regarding their geographical locations (MOE, Citation2019). Moreover, these universities are actively recruiting international students as a key strategy to improve the internationalisation of HE. Besides, it was convenient for the researchers to approach participants there given their networks with local students and faculty. Detailed participant information is indicated in Appendix I and the distribution of participants’ geographical origins and majors is displayed in .

Semi-structured interviews were conducted, including key questions on why participants chose to study in China (see Appendix II). The interview questions were created based on the push–pull model and the first author’s previous study about international students in China (see Dai & Elliot, Citation2022; Dai & Hardy, Citation2023). Each interview lasted 45–60 minutes and was audio-recorded. Participants were given a pseudonym to ensure anonymity and confidentiality. Moreover, the ethical application was approved by the selected universities before data collection, and interview questions were assessed by two experienced qualitative researchers. All interviews were conducted in English to ensure the accuracy of the conversation. The interview process lasted from November 2019 to April 2020, with 18 interviews conducted online due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

To analyse data, we adopted both inductive and deductive approaches. First, we conducted an inductive analysis, a ‘bottom-up’ process. Based on Braun and Clarke’s (Citation2019) thematic approach, we transcribed interviews and coded the data to identify potential factors. We categorised our findings hierarchically into three levels (i.e., macro-, meso-, and micro-) to understand the participants’ experiences in their contexts; these levels will be explained in the findings section. Then, based on the push–pull model, we deductively realigned the factors identified in the inductive analysis into distinct categories through several cycles of coding. Regarding researchers’ positionality, one author currently teaches international students in a Chinese institution; another author is an international doctoral student in China, while two authors have also undertaken doctoral studies in Western institutions as international students. Jointly, we undertake insider-outsider roles in the Chinese and global HE fields to facilitate collaborative analysis. Selected quotations based on specific themes are presented in our findings.

Findings

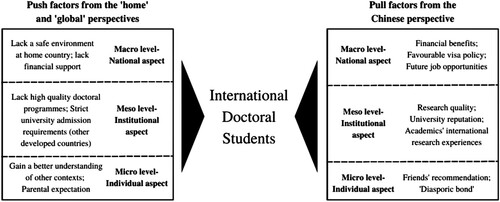

In identifying the motivation for international students to pursue doctoral degrees in China, our analysis categorised macro-, meso-, and micro-factors into three levels: national, institutional, and individual. The findings indicate that participants are systematically motivated by various factors.

Push–pull factors at national level

Financial benefits and potential career development in China

One of the most attractive pull factors is the economic benefits in China. For some students, economic benefits translate directly into financial support for living expenses. As Wen and Hu (Citation2019) stated, scholarships and low living cost are important direct pull factors for doctoral students from some developing countries, especially for those who need to bring their families to China. Thus, financial benefits offered by the Chinese government and universities play a significant role in attracting some doctoral international students from low-economic backgrounds. This national pull factor is mentioned by Ulugbek (M, 30, Mechanical Engineering, Kazakhstan):

To be honest, I need the scholarship for Ph.D. students offered by the Chinese government, and I can get approximately 6000–8000 Chinese Yuan per month, which is enough for me to take care of my wife and children in China. Meanwhile, my university also offers cheap accommodation on campus.

Since the ‘One Belt, One Road’ initiative (BRI), many countries have wanted to cooperate with China. As for me, I also want to learn deeply about China through doing my doctoral research about the influence of this initiative on economic development in Vietnam. After returning to Vietnam, I can be a ‘bridge’ between the two countries.

Favourable visa policies

Another advantage of studying in China, as students indicate, is the favourable visa policy compared to some Western destinations. Notably, some students perceive their national backgrounds to be a risk factor when applying for student visas in advanced fields like IT and engineering. For students from Islamic countries like Iran, Pakistan, and Egypt, they feel respected by China’s favourable issuance of visa. This policy is therefore a significant pull factor to attract some students to study in China, where they are treated equally as researchers rather than a ‘security threat’, a quote from Hazeem (M, 33, Biological Engineering, Pakistan), who explains:

It is difficult for us (from Pakistan) to gain a visa to some developed countries, for example, the US or the UK, perhaps due to political reasons. Even if we have good research proposals and ideas, we do not have opportunities to study in these countries. However, it is easier to obtain a visa from China, with solid research foundations in engineering or other fields.

Unsound socioeconomic environment at home country

Some students mentioned that the lack of a peaceful or economically thriving environment at home country propelled them to China. For example, Zosar (M, 28, Egypt, Physics) and Ankia (F, 26, South Africa, Medicine) are concerned about social instability at home, such as criminal issues and high unemployment rate. Even for students from relatively stable regions, a stagnant economy and gloomy job market for social science majors pushed them to China. This view is shared by Giovanni (M, 27, Education, Italy), Remi (M, 34, Language, US), and Dhia (F, 32, Finance, Malaysia). The double push factors of social and economic instability are reflected in Patricia’s (F, 34, Finance, Brazil) decision:

My country has crime issues. People hold arms freely and use them for criminal purposes. Even with a finance degree, it was hard for me to find a decent job that paid well. The only job I did was accounting, even then I risked losing my job any time because of the economy. My friends who came to China told me about how safe Chinese cities are. Being a girl, walking alone on the street at 11 pm was unthinkable in Brazil but not in China. I could even start a business here in cross-border trade after graduation.

Lack of funding at home or other developed countries

The cutbacks of university funding for doctoral students in participants’ home countries or some developed countries (e.g., the US and the UK) also pushed students to study in China. In many developed countries, the number of international doctoral students applying for scholarships is significantly higher than available quota. This is a significant push factor motivating students to seek opportunities in non-traditional destinations, like China, where research funding may equate to or even exceed that of some developed countries. As Sanoh (F, 26, Biological Engineering, Thailand) says:

I got several Ph.D. offers from universities in Australia and the UK but without a scholarship. It is too difficult to apply for a scholarship in these developed countries. I think maybe the Covid-19 pandemic made university financial situations worse. So, I gave up these opportunities. Fortunately, I got scholarships from China to keep my research.

Push–pull factors at the institutional level

Increasing research quality and university reputation in China

For research students, the quality, reputation, and ranking of a university are important pull factors when they choose a destination for doctoral education overseas. It is the same case with China. Most international doctoral students hope to conduct high-quality research to improve their international competitiveness. Given China’s increasing domestic competition among leading universities, many institutions are committed to enhancing research output. Thus, research strength and academic environment have become key determinants of China’s most outstanding universities, which appeals to international students. Rita (F, 35, Pharmacy, Malaysia) brimmed with satisfaction when discussing her doctoral research:

The key to our doctoral research is data from research experimentation as science students. In China, we do not worry about the level of laboratories, and we can devote ourselves to scientific research experiments because my supervisors can always support us and provide us with appropriate research equipment.

Chinese academics’ international research experiences

Chinese academics’ overseas research experience is a significant pull factor attracting many international students who cannot study in developed countries. Academic returnees from developed countries in China have become a ‘bridge’ between some international students and the so-called West-dominated knowledge field. As Purabi (F, 34, Social Work, Bangladesh) shares:

Initially, I wished to study in the US, but without enough money. Luckily, I found my professor’s information who got his doctoral degree from a top-ranked university in the US and had research experiences in several reputable institutions. Suppose I could study with my professor, I could potentially learn advanced knowledge from him, who seems to become a ‘broker or mediator’ between me and the developed academic context.

My supervisor has more than ten years’ experience in learning and research in the UK and then the US. Now, he brings what he had learned to a Chinese university as a returnee who also knows Chinese sociocultural situations. So, I can access advanced knowledge through his international experiences; meanwhile, I can learn from him about the Chinese context and knowledge, which will benefit my future development.

Lack high-quality doctoral programmes at home

The lack of high-quality doctoral programmes in some majors in students’ home countries pushes them to study in China. Notably, digitisation and the increasing reliance on avant-garde technology like big data means that the supplying research fields also need to be backed by a strong research infrastructure. This is especially the case for students in engineering, business, and natural sciences, whose home country institutions lack sufficient resources to power research. Meanwhile, for students in the social sciences and humanities, studying in China offers access to standardised doctoral education which many institutions in the home country fail to provide. Robert (M, 30, Education, Chad) shares:

Many academics in my country could not provide high-level research courses for students who want to study pedagogy, and they do not see it as a major. The lack of choices in majors pushed me to turn my eyes to other countries.

Strict university admission requirements in developed countries

Strict university admission requirement in some developed countries is another push factor which can explain why some students are driven from Western developed countries to China. That is, the strict entrance requirements (e.g., GPA, language test, and GRE) for doctoral students in some developed countries (e.g., the US and Canada). Many doctoral applicants turn their attention to China due to relatively easier enrollment criteria. In China, universities encourage international doctoral students who are native English speakers or have previously completed an English-taught degree programme to write their dissertations in English. In this way, the Chinese language test becomes optional for these international students. Giovanni (M, 27, Education, Italy) explains how this practice encouraged him to study in China:

I cannot speak Chinese. However, it does not influence my doctoral study in China. Many Chinese academics can speak English, and we do not need to write our doctoral theses in Chinese. Professors encourage students to write and publish papers in English.

Push–pull factors at the individual level

Diasporic bond of foreign-born Chinese

Some participants are Chinese descendants whose family culture influenced their learning destination choices. The diasporic bond embedded in these foreign-born Chinese motivates them to move to China for study. As Emilia (F, 30, Public Administration, Guatemala) said:

I am a descendant of the Chinese in Guatemala. When I was a young girl, I was taught and used Chinese with my family. My family celebrates every Chinese festival each year. So, I want to find my cultural roots and recognise my ancestors in China. I also hope that I can bring my family returning to their homeland and help them reunite with their Chinese relatives in the future. For this reason, I chose to have a research degree at a Chinese university.

Cultural curiosity and familiarity

Notably, some participants from Europe and the Americas expressed their interest and curiosity in the Chinese language, history, and culture when choosing China as a study destination. As Ma (Citation2017) indicates, ‘Chinese language education worldwide is a booming industry’ (p. 571), facilitating Chinese language learning and motivation to study in China. For instance, Remi (M, 34, Language, US) shares:

Chinese is a modern language worldwide. I want to conduct my doctoral research on the ‘Chinese language education industry in the world’. Because I am fascinated by the mystery of Chinese culture. I hope to have an unforgettable experience in China.

Family expectations and friend recommendations

Driven by the parents’ wish for cultural exposure and quality education, many students were encouraged to pursue doctoral studies in China. This personal factor is similar to the push factors motivating international students to pursue education in some developed countries (Kim, Citation2011). As Dhia (F, 32, Finance, Malaysia) says:

My parents encouraged me to study in China to extend my international horizon as a global citizen. They believed that China is an emerging country with strong international influence in the future. If I can study at Chinese universities, I will understand the difference between Western and Chinese social, educational, and economic systems.

Discussion

The study attempts to illustrate national, institutional, and individual factors to analyse international students’ motivations for conducting doctoral research in China beyond the macro-micro perspective. Overall, the findings reflect the dynamic negotiation students engage with when deciding to pursue doctoral education in China. The three-level analytical framework () could provide a systematic theoretical tool to explore factors influencing international doctoral students’ motivations to study in China (or other places).

Considering the push–pull factors at the national level, financial benefits (e.g., scholarship and job opportunities) and visa policies are essential in driving international doctoral students to China. In particular, some participants perceive the unsound social and economic development of their home countries. While doctoral education may become necessary for future development for some students, the lack of funding at home or in other developed countries drives them to China, where their academic needs can be met. In general, these findings apply to students across majors, yet students from developing and BRI-partner countries perceive more professional benefits in a Chinese doctoral degree. Furthermore, China’s favourable visa policies also indicate a welcoming attitude towards international students regardless of religions or national backgrounds. Also, as Zhou (Citation2014) mentioned, doctoral students’ motivation is influenced by positive career aspects and immigration purposes. In sum, at the macro-level, many students contrast domestic socioeconomic situations, financial support for research, and global migration control against the preferable factors in China.

At the institutional level, many doctoral students attach importance to the education quality and reputation of Chinese universities. This finding is in line with Li et al.’s (Citation2021) research that university international ranking is a critical pull factor impacting international doctoral students’ decision-making process. For doctoral students, research support including funding, facilities, and internship experience plays a vital role in motivating them to China. Similar factors attract international doctoral students to study in the US (Zhou, Citation2015). It is evident that when students compared different destinations to conduct their doctoral research, they realise that China is becoming an emerging HE hub. China possesses quality research facilities, an increasingly standardised educational system, and a symbiotic relationship between research and industries. Supervisors with international research experience are also a pull factor for doctoral students to study in China. Essentially, Chinese academic returnees act as ‘mediators’ as they bring Western knowledge to international students who may not have opportunities to study in developed countries but are eager to gain high-level research experience. These experiences may indicate Chinese universities are situated as an in-between learning space for some international doctoral students (Dai & Hardy, Citation2023).

While this phenomenon indicates that the research training system in the Chinese HE context may still engage in a process of Westernisation (Guo et al., Citation2022), the doctoral recruitment process in China demonstrates greater flexibility with its focus on student quality. For instance, stringent language requirements in developed countries, alongside other complicated admission procedures, are not required in many doctoral programmes in China.

Furthermore, concerning the individual aspect, especially for foreign-born Chinese doctoral students, the Chinese ‘blood bond’ in their identity (Hu & Dai, Citation2021), or diasporic attachment pulls them to conduct doctoral research in China, as some wish to gain more opportunities for personal development, given the challenges of fully integrating into their countries of migration. For non-ethnic Chinese students, their motivations include both cultural curiosity and affinity gained from remote exposure to Chinese popular cultural products. This finding is in line with Movassaghi et al.’s (Citation2014) suggestion that students study abroad based on a desire to live in other cultures, a ‘non-program’ factor in their decision-making. Considering push factors, like previous studies (e.g., Lee & Sehoole, Citation2015; Ma, Citation2017; Wu et al., Citation2021), relatives’ and peers’ suggestions also influence participants’ decisions to conduct doctural study in China.

Theoretically, this study extends the binary analytic angle of the push–pull model beyond the macro-micro, home-host dimensions into a dynamic approach. The findings show that those who conduct a doctoral study in China undergo a complex process of considering the interaction of national, institutional, and individual factors, across macro-, meso-, and micro-domains. Notably, international doctoral students’ decision is a result of push–pull negotiation of factors embedded in the home, Chinese, and international HE fields. The emerging role of the Chinese HE field in the global context mayencourage students to perceive it as an ‘in-between’ space in their doctoral study (Dai & Hardy, Citation2023). This analytical framework may be applied to investigate international doctoral students’ motivation in other contexts.

Several implications can be drawn from this study. While recruiting international students is a strategy for enhancing China’s soft power and shaping HE as global common goods (Tian & Liu, Citation2021), economy-related benefits still appear as a main priority for many doctoral students in China. As the findings indicate, China may function as an alternative for doctoral students who cannot study in developed countries, and does not yet sufficiently attract students from developed regions. This insight suggests that Chinese universities play complex roles (e.g., semi-peripheral or middle) in the world knowledge system (Yang, Citation2022). Pursuing doctoral research in China is an opportunity for international students to develop cosmopolitan capital with academic returnees and experience Chinese sociocultural contexts. To enhance the quality of doctoral education, Chinese universities may need to progressively upgrade quality assessment and assurance systems to improve teaching, research, and learning activities.

Conclusion

This study analyses factors motivating international students to pursue their doctoral research in China. It classifies the factors into three aspects according to the push–pull model, specifically, macro-, meso-, and micro-factors from the aspects of nation, institution, and individual, which comprehensively influence students’ choice of China as a learning destination. As the findings suggest, China is becoming a popular learning destination for many international doctoral students. While China is progressively improving the competitiveness of its HE sectors, it becomes imperative to increase the quality of HE to attract international doctoral students. This study also has some limitations. It did not utilise quantitative research analysis to investigate a large sample. Thus, the findings cannot be generalised. Future studies may investigate a larger sample size of international doctoral students in China. Meanwhile, it is also necessary to compare doctoral students’ motivation to study in different countries.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (35.1 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 ‘Double-First Class’ plan is a university development initiative proposed by the Chinese government in 2015. It aims to comprehensively develop selected elite institutions (most of them are former 985–211 universities) to become ‘world-class’ universities by the end of 2050.

References

- Ahmad, A. B., & Shah, M. (2018). International students’ choice to study in China: An exploratory study. Tertiary Education and Management, 24(4), 325–337. https://doi.org/10.1080/13583883.2018.1458247.

- Altbach, P. G. (1998). Comparative higher education: Knowledge, the university and development. Ablex Pub. Corp.

- Altbach, P. G. (2003). The decline of the guru: The academic profession in developing and middle-income countries. Palgrave.

- Bae, J. S. (2020). Transnational student mobility: Educational and social experiences of mixed-race Koreans in Seoul. Multiculture & Peace, 14(2), 74–100. http://doi.org/10.22446/mnpisk.2020.14.2.004.

- Bao, Y., Kehm, B. M., & Ma, Y. (2018). From product to process. The reform of doctoral education in Europe and China. Studies in Higher Education, 43(3), 524–541. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2016.1182481

- Bodycott, P. (2009). Choosing a higher education study abroad destination. Journal of Research in International Education, 8(3), 349–373. http://doi.org/10.1177/1475240909345818.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 11(4), 589–597. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806

- Dai, K. (2021). Transitioning ‘In-between': Chinese students’ navigating experiences in transnational higher education programmes. Brill.

- Dai, K., & Elliot, D. L. (2022). ‘Shi men’ as key doctoral practice: Understanding international doctoral students’ learning communities and research culture in China. Oxford Review of Education, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/03054985.2022.2123309

- Dai, K., & Hardy, I. (2022). Language for learning? International students’ doctoral writing practices in China. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2022.2089154

- Dai, K., & Hardy, I. (2023). Pursuing doctoral research in an emerging knowledge hub: An exploration of international students’ experiences in China. Studies in Higher Education, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2023.2166917

- Ding, X. (2016). Exploring the experiences of international students in China. Journal of Studies in International Education, 20(4), 319–338. https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315316647164

- Findlay, A., King, R., Smith, F. M., Geddes, A., & Skeldon, R. (2012). World class? An investigation of globalisation, difference and international student mobility. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 37(1), 118–131. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-5661.2011.00454.x

- Gbollie, C., & Gong, S. (2020). Emerging destination mobility: Exploring African and Asian international students’ push-pull factors and motivations to study in China. International Journal of Educational Management, 34(1), 18–34. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEM-02-2019-0041.

- Glass, C. R., & Cruz, N. I. (2022). Moving towards multipolarity: Shifts in the core-periphery structure of international student mobility and world rankings (2000–2019). Higher Education, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-022-00841-9.

- Gopal, A. (2016). Visa and immigration trends: A comparative examination of international student mobility in Canada, Australia, the United Kingdom, and the United States. Strategic Enrollment Management Quarterly, 4(3), 130–141. https://doi.org/10.1002/sem3.20091

- Guo, Y., Guo, S., Yochim, L., & Liu, X. (2022). Internationalization of Chinese higher education: Is it westernization? Journal of Studies in International Education, 26(4), 436–453. https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315321990745.

- Hu, Y., & Dai, K. (2021). Foreign-born Chinese students learning in China: (Re)shaping intercultural identity in higher education institution. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 80, 89–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2020.11.010

- IIE. (2020). 2020 Project atlas infographics. https://www.iie.org/en/Research-and-Insights/Project-Atlas/Explore-Data/Infographics/2020-Project-Atlas-Infographics

- Kehm, B. M., & Teichler, U. (2007). Research on internationalisation in higher education. Journal of Studies in International Education, 11(3-4), 260–273. http://doi.org/10.1177/1028315307303534.

- Kim, J. (2011). Aspiration for global cultural capital in the stratified realm of global higher education: Why do Korean students go to US graduate schools? British Journal of Sociology of Education, 32(1), 109–126. http://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2011.527725

- Knight, J. (2004). Internationalization remodeled: Definition, approaches, and rationales. Journal of Studies in International Education, 8(1), 5–31. https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315303260832

- Lee, J. J., & Sehoole, C. (2015). Regional, continental, and global mobility to an emerging economy: The case of South Africa. Higher Education, 70(5), 827–843. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-015-9869-7

- Li, F. S., Qi, H., & Guo, Q. (2021). Factors influencing Chinese tourism students’ choice of an overseas PhD program. Journal of Hospitality, Leisure, Sport & Tourism Education, 29, 100286. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhlste.2020.100286

- Li, F. (S.), & Qi, H. (2019). An investigation of push and pull motivations of Chinese tourism doctoral students studying overseas. Journal of Hospitality, Leisure, Sport & Tourism Education, 24, 90–99. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhlste.2019.01.002

- Li, J., & Xue, E. (2022). New directions towards internationalization of higher education in China during post-COVID 19: A systematic literature review. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 54(6), 812–821. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2021.1941866

- Li, M., & Bray, M. (2007). Cross-border flows of students for higher education: Push–pull factors and motivations of mainland Chinese students in Hong Kong and Macau. Higher Education, 53(6), 791–818. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-005-5423-3

- Ma, J., & Zhao, K. (2018). International student education in China: Characteristics, challenges, and future trends. Higher Education, 76(4), 735–751. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-018-0235-4

- Ma. J. (2017). Why and how international students choose mainland China as a higher education study abroad destination. Higher Education, 74(4), 563–579. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-016-0066-0

- Maringe, F., & Carter, S. (2007). International students' motivations for studying in UK HE. International Journal of Educational Management, 21(6), 459–475. http://doi.org/10.1108/09513540710780000.

- Mazzarol, T., & Soutar, G. N. (2002). ‘Push-pull’ factors influencing international student destination choice. International Journal of Educational Management, 16(2), 82–90. https://doi.org/10.1108/09513540210418403.

- Merriam, S. B. (2009). Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation (3rd ed.). John Wiley & Sons.

- MOE. (2004). 2003 statistical yearbook on foreign students in China. http://www.moe.gov.cn/srcsite/A20/moe_850/200402/t20040206_77826.html

- MOE. (2019). Statistics of international students in China in 2018. http://www.moe.gov.cn/jyb_xwfb/gzdt_gzdt/s5987/201904/t20190412_377692.html?from=groupmessage&isappinstalled=0

- Movassaghi, H., Unsal, F., & Göçer, K. (2014). Study abroad decisions: Determinants & perceived consequences. Journal of Higher Education Theory and Practice, 14(1), 69–80.

- Paulino, M. A., & Castaño, M. C. N. (2019). Exploring factors influencing international students’ choice. Review of Integrative Business and Economics Research, 8, 131–149.

- Shen, W., Wang, C., & Jin, W. (2016). International mobility of PhD students since the 1990s and its effect on China: A cross-national analysis. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 38(3), 333–353. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360080X.2016.1174420

- Shin, J. C., Postiglione, G. A., & Ho, K. C. (2018). Challenges for doctoral education in east Asia: A global and comparative perspective. Asia Pacific Education Review, 19(2), 141–155. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12564-018-9527-8

- Teichler, U. (2004). The changing debate on internationalisation of higher education. Higher Education, 48(1), 5–26. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:HIGH.0000033771.69078.41

- Tian, L., & Liu, N. C. (2021). Inward international students in China and their contributions to global common goods. Higher Education, 81(2), 197–217. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-020-00522-5

- Wen, W., & Hu, D. (2019). The emergence of a regional education hub: Rationales of international students’ choice of China as the study destination. Journal of Studies in International Education, 23(3), 303–325. https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315318797154

- Wu, M. Y., Zhai, J., Wall, G., & Li, Q. C. (2021). Understanding international students’ motivations to pursue higher education in mainland China. Educational Review, 73(5), 580–596. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2019.1662772

- Yang, P. (2022). China in the global field of international student mobility: An analysis of economic, human, and symbolic capitals. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education, 308–326. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057925.2020.1764334

- Yang, Y., Volet, S., & Mansfield, C. (2018). Motivations and influences in Chinese international doctoral students’ decision for STEM study abroad. Educational Studies, 44(3), 264–278. https://doi.org/10.1080/03055698.2017.1347498

- Zhang, Y., O'Shea, M., & Mou, L. (2021). International students’ motivations and decisions to do a PhD in Canada: Proposing a three-layer push-pull framework. Canadian Journal of Higher Education, 51(2), 61–73. https://doi.org/10.47678/cjhe.vi0.189027

- Zhou, J. (2014). Persistence motivations of Chinese doctoral students in science, technology, engineering, and math. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 7(3), 177–193. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037196

- Zhou, J. (2015). International students’ motivation to pursue and complete a Ph.D. In the U.S. Higher Education, 69(5), 719-733. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-014-9802-5