ABSTRACT

As part of their international higher education experience, international students in some degree programs are required to secure and complete work placements. This is challenging to many, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic. Despite this, there is limited research on how international students navigate challenges to secure placements in their host country, which informed the current study. Data was gathered through 39 semi-structured interviews with 13 international engineering students and eight interviews with eight WIL staff. The study contributes to the literature by formulating the Perceiving–Planning–Performing Model (3-P Model), untangling students’ cognitive, attitudinal, and behavioral engagement in securing placements. The Model informs stakeholder strategies in nurturing international students’ agency to secure placements and post-graduation work in their host country and globally.

Introduction

With increasing labor market competition, many students choose to study abroad to enhance competitive advantage (Gribble et al., Citation2015; Tran, Citation2019). Integral to the decision to study overseas is the desire to obtain work experience in the host country, usually through work placements. In this study, WIL is understood as ‘an educational approach that uses relevant work-based experiences to allow students to integrate theory with the meaningful practice of work’ (IJWIL, Citationn.d., para. 2). Work placement (or ‘placement’) is a form of workplace-based WIL.

WIL, particularly placement, is recognized worldwide as an effective strategy for the work-readiness development of students, including international students (Aprile & Knight, Citation2020; Tran & Nguyen, Citation2019). Placements in the host country are beneficial for international students’ global career prospects as they offer students opportunities to experience local workplace cultures, professional practices, industry relationships, and labor market dynamics. The knowledge and skills developed through such opportunities enhance international students’ capacity to work globally (Gribble et al., Citation2015).

Some degree programs require students to source and complete placements prior to graduation. Securing placements is challenging for many international students due to various factors such as language barriers, minimal networks, and employer reluctance to take on international students (Jackson, Citation2017; Pham et al., Citation2018). Despite extensive research on challenges to international students in securing placements, there are two notable gaps in the literature: (i) how international students navigate challenges to secure placements and (ii) a related research framework.

The current study employed an integrative framework (Anderson et al., Citation2012; Schlossberg, Citation1981; Vu, Ferns, & Ananthram, Citation2022) to examine international students’ strategies in navigating challenges to secure placements situated in the workplace. Data was collected from international undergraduate students and WIL staff at an Australian university.

The Australian context

Australia is a well-established overseas study destination. ‘More than three million international students have studied in Australia over the last fifty years’ (Australian Government, Citation2021, p. 16). Enhancing opportunities and capacities for international students to participate in placements is a key action in the Australian National WIL Strategy (Universities Australia et al., Citation2015). The Strategy calls for stakeholder collaboration and seeks to mobilize resources from governmental agencies, educational institutions, and employers to enhance the availability of, and accessibility to, placements for international students.

The National WIL Strategy is of strategic importance as ‘[i]nternational students have always been an important source of labour for Australia, both while they are studying and through post-study work rights’ (Australian Government, Citation2021, p. 11). International engineering students, targeted subjects of the current study, are important to the Australian economy as skills requiring engineering expertise are on the Skills Priority List to address the skills shortage in Australia (Australian Government, Citation2021).

Despite national-level efforts exemplified by the National WIL Strategy, visa-related restrictions represent notable system-level barriers for international students. During data collection for the current study, Visa Condition 8104 indicated that onshore international undergraduate students were allowed to work 40 h per fortnight (Australian Government, Citationn.d.), which deterred employers from offering full-time, paid placements (e.g., 40 h per week) to international students. Consequently, securing placements remains challenging for international students, which highlights a need to inform research and practice by examining international students’ lived experiences in securing placements.

Literature review

The literature indicates that many international students struggle to secure placements due to various personal and contextual factors (Felton & Harrison, Citation2017; Pham et al., Citation2018). Personal factors adversely affecting international students in securing placements include lack of local work experience, language deficiency, limited intercultural communication skills, and minimum support networks (Felton & Harrison, Citation2017; Jackson, Citation2017). Contextual factors that present barriers to international students in securing placements include visa-related restrictions on international students' work rights such as working hours limits (Jackson, Citation2016), reluctance of employers to engage with international students (Jackson, Citation2016, Citation2017; Tran & Vu, Citation2016), and intense competition with domestic students for placements (Felton & Harrison, Citation2017). Further, COVID-19 has had negative impacts on international students in securing placements. COVID-related lockdowns, traveling restrictions, social distancing, and the move to online work have led to placement cancelation and limited availability of on-site placements (Dean & Campbell, Citation2020; Kay et al., Citation2020).

Although challenges facing international students in securing placements are established in the literature, students’ strategies in navigating such challenges are under-researched. Research relating to international students’ experiences in securing placements has been largely framed by a deficit-based approach which focuses primarily on international students’ deficits and challenges (Vu, Ferns, & Ananthram, Citation2022). The deficit-based approach has two major limitations. It tends to neglect the role of student agency regarded by Ferns et al. (Citation2022) as a key dimension of WIL quality. This approach, as observed by Tran and Vu (Citation2018, p. 177), is also inclined to stereotype international students, particularly Asian students, as ‘passive and reactive in expressing and addressing their needs’.

In a broader context of international students’ transnational mobility, several researchers have challenged the aforementioned stereotypes against international students (e.g., Tran, Citation2016; Tran & Vu, Citation2018). Empirical findings from Tran and Vu (Citation2018) assert that international students in vocational education were ‘active agents’ (p. 178) as they made ‘initiatives to address their own learning needs’ (p. 177). These authors’ findings highlight the role of international students’ proactivity in enhancing learning and professional development. Such proactivity is associated with ‘agency for becoming’ (termed by Tran & Vu, Citation2018, p. 183). Becoming here ‘encompasses students’ aspirations for educational, social, personal and professional development’ (Tran, Citation2016, p. 1268), thus shaping their subsequent engagement in learning and professional development.

Theoretical framework and research questions

The study adopted Vu, Ferns, & Ananthram’s (Citation2022) Cause–Challenge–Consequence Model (3-C Model) for researching how international students navigate challenges in WIL. The Model was developed through a review study which analyzed and synthesized findings from empirical research over the past decade. Their review was guided by transition theory which was originally developed by Schlossberg (Citation1981) and advanced by Anderson et al. (Citation2012).

A transition is ‘any event or nonevent that results in changed relationships, routines, assumptions, and roles’ (Anderson et al., Citation2012, p. 39). Student engagement in placement seeking is regarded in the current study as a transition since it results in changed relationships (e.g., social networks), assumptions (e.g., self-perception), and roles (e.g., turning from an information seeker into a placement applicant). Transition theory provides a 4S framework for researching individuals’ transition (Anderson et al., Citation2012, p. 61): Situation (What is happening?); Self (To whom is it happening?); Support (What help is available?); and Strategies (How does the person cope?).

The 3-C Model guided the current study regarding three dimensions of student engagement: (i) Cause – causes of challenges (undesirable aspects of Situation, Self, and Support); (ii) Challenge – specific areas of challenges across students’ WIL journey; and (iii) Consequence of challenges on Strategies adopted by students. Since the current study focused on how students navigate challenges to secure placements, two major aspects of the 3-C Model were adapted. First, the 3-C Model depicts how challenges adversely affect strategies by students, whilst the current study examined the strategies students employ to address challenges. Second, the 4S framework was adapted to the context of international students’ placement seeking in the host country, namely Situation (triggers of student attempts to address challenges to secure placements and their attitudes towards these triggers); Self (student strengths and weaknesses in relation to securing placements in the host country); Support (university-provided support and students’ self-sourced support); and Strategies (timing and tactics regarding how students navigate challenges to secure placements).

A transition is triggered by a change, also known as a crisis (Anderson et al., Citation2012), and individuals’ engagement in a transition is associated with ‘the capacity to navigate change’ (Gale & Parker, Citation2014, p. 16). The current study then sought to establish how international students transition through challenges to secure placements situated in the workplace. Aspects of interest included international students’ personal factors (Self), contextual factors (Situation & Support), interrelations between personal and contextual factors, and student engagement patterns (Strategies). The study addressed three questions:

What challenges do international students face while seeking placements in the host country (Situation)?

What do they perceive as the main causes of those challenges (undesirable aspects of Situation, Self, and Support)?

How do they address those (causes of) challenges to secure placements (Strategies)?

Method

Research context

This study is part of a larger project which examines international students’ engagement before (the focus of this study), during, and after placements. Samples were drawn from the Faculty of Science and Engineering of a Western Australian University. Data was collected amid COVID-19, during July 2020 and March 2021. However, Western Australia was not significantly affected by COVID during this period.

All engineering degrees undergo professional accreditation with Engineers Australia (Engineers Australia, Citation2019). A condition for graduation requires students to self-source and complete 480 h of exposure to professional engineering practice (EPEP) at any time during their university years. The 480 h can be completed through an accumulation of discrete placements. Students fulfill the EPEP requirements through several options such as industry-based projects, industry-based site visits, or work in an engineering or non-engineering firm (Engineers Australia, Citation2019). These options are hereafter collectively referred to as ‘work placements’ or ‘placements’.

Research design

Qualitative research, recommended for examining under-researched phenomena (Creswell & Poth, Citation2017), was employed to investigate how international students navigate challenges to secure placements. Two sets of data were gathered: (i) interviews with international students and (ii) interviews with the university’s WIL staff. Data collected from WIL staff confirmed student data on how they were supported by the university in seeking placements, thereby enabling information validation (Creswell & Poth, Citation2017). Data was collected via semi-structured interviews using open-ended questions, which enabled participants to ‘best voice their experiences unconstrained by any perspectives of the researcher or past research findings’ (Creswell, Citation2012, p. 218).

Participants and data collection

Ethics approval was granted by the participants’ university, with assurance of voluntary participation, informed consent, and participants’ anonymity. Student participants were recruited through online advertisements (e.g., Faculty website) and a snowball approach (Creswell & Poth, Citation2017). International undergraduate engineering students from the university who were seeking or had acquired a placement met the recruitment criteria. Thirteen final-year students were interviewed (). The sample represents multiple nationalities and various engineering disciplines.

Table 1. Student participants.

WIL staff were recruited through Faculty introduction and email invitations. Eight WIL staff participants were interviewed, including the Director of Student Engagement, the Student Experience Coordinator, and the Curriculum Lead. In addition, the Manager and four career consultants from the university’s Career Development Section attended interviews.

All interviews were conducted online (through WebEx), and recordings were transcribed using Otter software. Each of the WIL staff attended an individual 30-minute semi-structured interview about their experiences in, and perceptions of, supporting international students to secure placements.

Each student participant attended three, 45-minute semi-structured interviews. These three interviews typically addressed student experiences before, during, and after placement, respectively. The topics relating to their placement seeking emerged across three interviews. Students were asked to narrate how they sought their most recent placement, and specific questions built on the 4S were employed to facilitate their recall (Appendix).

Analysis

Data was analyzed in two phases: (i) describing individual students’ narrative about securing placements, and (ii) synthesizing findings corresponding to each of the research questions (). An iterative process was employed to ensure rigorous data coding and analysis (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006; Saldaña, Citation2016). Prior to data coding and analysis, interview scripts were imported to NVivo (version 12) to ensure systematic data identification, comparison, and synthesis.

Table 2. Overview of data analysis.

The first data analysis phase focused on student data and included four steps to obtain coherent narratives from students. First, the ‘boundaries’ around each narrative (Riessman, Citation2012) were identified, beginning with recognizing the EPEP requirement and ending with placement seeking outcomes and reflection. Second, since relevant data could ‘emerge in bits and pieces over the course of the interview[s]’ (Riessman, Citation2012, p. 371), student data was thematically coded according to the three research questions. Third, results of data coding were aligned to the three research questions before being arranged in ‘a sequence of ordered events that are connected in a meaningful way … in order to make sense of the world and/or people’s experiences in it’ (Bell, Citation2002, p. 6).

The second phase adopted thematic analysis – ‘a method for identifying, analyzing and reporting patterns (themes) within data’ (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006, p. 79). Themes corresponded to three dimensions of student engagement (see dimensions in ). Data from all students and WIL staff was integrated across three data coding and analysis steps. First, data was coded and aligned to the three dimensions of student engagement. Second, broad themes corresponding to student engagement dimensions were analyzed and identified. Third, the interplay among these themes and its impact on student engagement were analyzed and established. The third step moved beyond thematic analysis and involved a complicated process of analyzing, interpreting, and establishing abstract ideas embedded in data (Saldaña, Citation2016).

Findings

This section reports findings from the interviews with the international student participants, followed by a synthesis of findings from two data sets. provides an overview of the placement seeking details for each of the 13 student participants (identified as ‘S’). All student participants aimed to find post-graduation employment in their chosen career in Australia and were strongly motivated to find discipline-related placements in this country as a pathway to their career goals (e.g., S2, S3, S13). However, at the final interview for the study, two students (S9, S11) were still seeking a placement. The remaining students acquired on-site placements through two major channels: formal application (e.g., S2, S3, S5) and friends’ recommendations (S1, S4, S7, S8). Eight students obtained placements in Australia (e.g., S2, S7), and three in their home country (S5, S6, S13).

Table 3. Outcomes of placement seeking.

Examples of student narratives

Three example narratives are described here, representing diverse experiences and outcomes of international students’ placement seeking: failing to find a placement, seeking volunteering to satisfy the EPEP requirement, and successful placement acquisition.

Narrative 1: failing to find a placement

This student (S9), from Singapore, was studying Chemical Engineering and became aware of the EPEP requirement in second year ‘when friends started talking about it’. She ‘would love to probably get a job in Australia’ after graduation and was strongly motivated to find discipline-related placements in Australia. However, most placement opportunities were for ‘Australians and permanent residents’. Further, placement opportunities accessible to her were highly competitive, which was ‘another huge challenge’. S9 said ‘most of my Aussie friends got placements from their parents … from contacts, family, friends, or their parents’ company’.

S9 sought placements using various information sources. She reported, ‘[I have been] trying to see if my friends can help me, but … they are struggling as well’. She pursued support from the university but discovered most placement opportunities promoted by the university were for domestic students: ‘it’s pretty like useless to international students, we can’t use them’. S9 also attended career fairs where students learnt about local companies, but these forums offered ‘general advice’ only. She began seeking interstate placements: ‘I’ve even tried outside of Perth [where I was studying]. I’ve tried Sydney and Melbourne’.

At the final interview, S9 was still seeking a placement. When asked what she would have done if she had known about the EPEP requirement earlier, she responded, ‘I would have definitely started [seeking placements] earlier for sure, which is something I regret now’. She added, ‘it’s really important to have contacts … [b]ut most of us don’t have that since our families are all back in our home country’.

Narrative 2: seeking volunteering to satisfy the EPEP requirement

This was a Nepalese student (S10) studying Electrical Engineering. He was aware of the EPEP requirement in second year through senior students. S10 aimed to find post-study employment ‘to get a PR [permanent residency]’ and was therefore highly motivated to source placements in Australia. However, S10 observed that there were ‘very limited’ placement opportunities for international students and there was ‘a lot of competition, because there are a lot of students doing it. … There’s no way to get into those ones being international’. Consequently, he decided to seek volunteer opportunities.

S10 sought support from peers but found this unhelpful. He had little time for socializing: ‘I do two jobs. … I don’t have a lot of time to make friends’. When asked about the support available at the university, S10 responded, ‘I’m not aware of that’. He searched for volunteering opportunities on websites of organizations such as museums, Red Cross and religious organizations. He also called and ‘emailed a lot of organizations’ but was repeatedly rejected. S10 reported, ‘they were talking about the liability issues,’ particularly ‘insurance issues’ associated with international students on placements. Even when S10 explained that his university provided insurance cover for students undertaking volunteering, organizations were reluctant, as ‘they will not risk anything like that’.

S10 eventually acquired two volunteering opportunities: the first was in a motor museum and ‘the next was also voluntary, but for a specific project’. He learnt that ‘definitely, we need to reach out. … It’s not like looking for a position advertised on the website or something’. He believed that such initiatives were effective, emphasizing ‘20 out of 100’ organizations are interested in ‘free labor’.

Narrative 3: successful placement acquisition

S3, from Vietnam, completed the Chemical Engineering degree program shortly before the research interviews. She first knew about the EPEP requirement through conversations with classmates in second year. S3 planned to ‘work in the mining industry in Western Australia’ and subsequently had strong motivation to obtain discipline-related placements.

S3 observed that ‘[s]mall companies here are taking advantage of international students. They offer non-paid placements but ask students to do a lot of work’. She added, ‘most large companies here just take on students who are permanent residents or citizens … [further,] large companies advertise [placements] on different channels’, which led to increased competition. She was concerned about her capability to address that competition: ‘I was not self-confident in my English … [and] I didn’t have local work experience’.

S3 developed a strategic plan to secure Australian-based placements: ‘I got my foot in the door through undertaking volunteering and less desirable placements’. She also engaged in personal development including improving English competence, interpersonal skills, knowledge of local work contexts, resume and cover letter writing, and interview skills. She said, ‘I started thinking and speaking in English only. … I made friends and hung out only with English-speaking people … [and] I watched only English entertainment programs’. She practiced interview skills until she believed she could express herself ‘confidently and impressively’. S3 also deployed various information and support sources while seeking placements, particularly peers and senior students.

When attending the first research interview, S3 had completed four placements in Australia and confirmed three were ‘definitely related to my discipline’. Notably, prior to undertaking the fourth placement, she was offered three opportunities. S3 concluded the first factor to her successful placement acquisition is ‘self-confidence’ built on advanced English proficiency, interpersonal skills, adequate and frequent practice, and prior local work experience. The second factor is the ability to harness personal support networks. S3 believed that what she had learnt from peers and seniors accounted for 60 percent of her placement attainment, as ‘they shared lived and specific experiences and knowledge of particular companies’.

Synthesis of findings

This section interprets and synthesizes data from the students and WIL staff (referred to as ‘WS’), addressing each of the research questions. Data synthesis identified three interrelated themes, each being presented below.

Challenges in finding placements (RQ1): limited placement availability and uphill competition with domestic peers

Despite challenges, student participants did not receive adequate institutional or governmental support, which subsequently triggered their agency to navigate challenges to secure placements. Three key challenges were identified.

First, there was limited placement availability for international students due to cultural, financial, and legal factors (e.g., S10, S13, WS1, WS2). Culturally, there was ‘an inherent bias towards either recruiting Australians or distrusting or being a bit uncertain about hiring international students’ (WS4). Employers are concerned about international students’ limited capability to fit into their organizational culture due to language and cultural differences (S3, WS4, WS6). Financially, employers offer placements usually ‘as a screening tool … [to] source future talents to join their organization’ (WS5) and they are therefore unwilling to take on and invest in international students who employers think will return home (S13, WS1, WS3). Legally, many local firms, particularly small ones, were uncertain about international students’ work rights and the legal process relating to recruiting international students for placements, hence being reluctant to engage with international students (S10, WS3, WS6).

Second, placement opportunities available to international students involved high competition with peers, especially domestic ones. Regarding the competition with domestic peers, ‘it's not a level playing field’ (S8) since ‘local students have an upper hand in applying for a job’ (S2). The student participants who sought a paid placement regarded it as a casual job which they could hardly obtain since they lacked local support networks, knowledge of local work contexts, and local work experience (S5, S11, WS5, WS6).

Third, the aforementioned challenges – limited placement opportunities and competition with domestic peers – intensified during COVID-19 due to lockdowns, social distancing, and traveling restrictions (S9, S11, S12, S13). Lockdowns and social distancing exacerbated the limitation of placement opportunities: ‘it's been very difficult to find one just in in terms of COVID and everything. … [O]pportunities are very limited’ (S11) because ‘a lot of people don’t actually want to take in interns’ (S9). COVID-related restrictions also deprived international students of opportunities for self-development to address competition with domestic peers. Building networks and developing communication and interpersonal skills are integral to improving placement seeking capacity. However, students had to stay ‘away from campus trying to adjust to online learning and everything. … [I]t was a purely digital-based interaction’ (S11).

Most student participants were anxious about the potential inability to find a placement to fulfill the graduation pre-requisite. S11, for example, remarked: ‘it’s almost like you’re just thrown to the wolves on your own, and you kind of have to scramble around for information’. Students then recognized a compelling need to practice agency, as S9 remarked: ‘most of us usually have to look on our own, and it's pretty difficult, especially with COVID’.

Perceived causes of challenges (RQ2): interplay between undesirable aspects of personal and contextual factors

There are two important findings relating to Research Question 2: the constitution of challenges and two strands of student attitudes. Findings informed the development of a model which illustrates the constitution of challenges to international students in securing placements in the host country (). Challenges were constituted by the interplay between undesirable aspects of international students’ personal factors (Self) and contextual factors (Situation & Support). Such interplay was characterized by international students being in ‘a foreign kind of environment, something that they haven't grown up with and lived with’ (WS7). The contextual factors featured the EPEP requirement as a graduation condition for both domestic and international student cohorts (Situation), but the university’s support and resources (Support) were the same for both cohorts. A staff participant affirmed, ‘we place no difference on international and domestic students’ (WS7).

The interplay between the Self and Situation indicates that the international student participants suffered disadvantages and were marginalized due to their overseas backgrounds. This was exemplified by local employers unwilling to host international students (S9, S13, WS4, WS6), leading to limited placement availability. Likewise, the interplay between Self and Support shows that international students’ information and support needs were unmet by the university (S5, S9). Some students complained that the university did not provide timely support (e.g., S5, S11): ‘it was such a long and weird process’ (S5). However, a WIL staff participant (WS3) complained about procrastination among some international students: ‘they often leave the activity [the EPEP] till the last minute where we are unable to provide them any real support’.

Regarding their perceptions of, and attitudes towards, the two major challenges and the causes of those challenges, the student participants could be categorized into two groups. The first group tended to focus on undesirable personal factors (Self) as the causes of challenges, whilst the second inclined to attribute challenges to negative contextual factors (Situation & Support). An example of the first group is S3, who recognized a compelling need to develop the Self to become sufficiently capable for competing with domestic students. S3 related, ‘I wasn’t confident at all. … Those who had had internship experience told me that confidence is a crucial factor. … So, I practiced … so that I could be more confident’. In contrast, a student from the second group focused on negative contextual factors: ‘I’ve been looking in Australia. And again, that disadvantage [challenges] was there … so I will come back to Singapore and try to look for placements’ (S9).

Strategies in transitioning through challenges (RQ3): proactive engagement versus reactive engagement

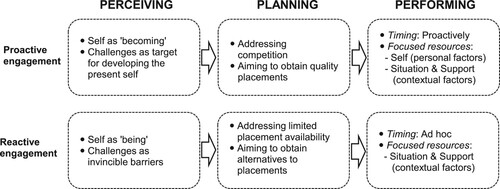

Salient findings were interpreted and distilled into the Perceiving–Planning–Performing Model of Student Engagement in Securing Placements (3-P Model, ). The Model untangles students’ cognitive, attitudinal, and behavioral engagement in a three-stage process of securing placements: perceiving, planning, and performing. The perceiving stage relates to Questions 1 and 2 whilst the other two stages are associated with Question 3. The Model also illustrates two approaches student participants adopted in securing placements, termed in this article as ‘proactive engagement’ and ‘reactive engagement’.

The perceiving stage involves students’ cognitive and attitudinal engagement as it comprises students’ perceptions of Self and attitudes towards (causes of) challenges. This stage entails sophisticated processes of evaluating and interlinking personal factors (Self) and contextual factors (Situation & Support), as indicated earlier. The planning stage entails cognitive engagement as it involves decision making (e.g., whether to address competition) and goal setting (e.g., obtaining a paid placement). The performing stage involves students’ behavioral engagement including observable acts such as attending career fairs and contacting recruiters. Two key aspects of students’ behavioral engagement are timing (proactively, ad hoc) and focused resources (personal/contextual factors).

There are causal links between the three stages of securing placements. Students’ perceptions of their present self and attitudes towards challenges (perceiving stage) shaped their plan to address challenges (planning stage). In turn, their plan guided performance in navigating these challenges (performing stage). As such, differences in perceiving will lead to variations in planning and performing. Such differences can be categorized into two approaches to securing placements, indicated below.

Proactive engagement. The first student group tended to view the Self as ‘becoming’ and challenges as drive for transitioning from their present self to desired self. ‘Becoming is a transition towards an embodiment of the desired change which will demonstrate a transformative movement’ (Natanasabapathy & Maathuis-Smith, Citation2019, p. 376). These students subsequently aimed to acquire quality placements which were paid, discipline-related, and Australian-based. They accordingly planned to address competition to secure desired placements.

The first notable strategy they adopted was to proactively learn about and/or seek placements early in their studies (i.e., strategic timing). A second strategy was addressing both personal (Self) and contextual factors (Situation & Support), hence mobilizing both personal and environmental resources. They sought and used various sources of support and invested in their present self to become sufficiently capable to address competition. For example, S2 transitioned from a timid into a sociable student, driven by the thought that ‘if you want to get a job in the future, you need to know how to communicate with people’. She accordingly developed communication skills and built networks through participating in student clubs and professional associations.

Reactive engagement. The second student group inclined to regard the Self as ‘being’ and challenges as invincible barriers. ‘The state of being reflects how a person’s nature or behavior is at present’ (Natanasabapathy & Maathuis-Smith, Citation2019, p. 376). Due to self-perceived deficiencies (e.g., lack of local work experience), these students were not confident in competing with domestic peers and consequently sought alternatives to placements such as volunteering opportunities that were unrelated to their primary engineering discipline.

These students’ engagement in placement seeking reflected an ad hoc response to the EPEP requirement (i.e., ineffective timing). Some were not aware of the EPEP requirement until the second year of studies (e.g., S9, S10), and others delayed seeking placements until the third year (e.g., S9, S11). A WIL staff participant (WS3) said, ‘we send multiple emails every semester … [through] Blackboard, the unit coordinators, [and] the clubs’, reinforcing that international students possibly felt ‘overwhelmed’ rather than being unaware of the EPEP requirement.

Importantly, students’ decisions on the engagement approach were not necessarily linked with self-confidence. For example, both S2 and S3 identified deficiencies in intercultural communication and limited knowledge of local work contexts. However, they decided to address competition and subsequently developed the Self in preparation for competition. Equally important, students might shift between the two engagement approaches, depending on their strategic plans and specific contexts. S3 addressed limited placement availability to ‘get a foot in the door’ before becoming capable of addressing competition. Conversely, S2 initially chose to address competition but then shifted to addressing limited placement availability after a series of failed attempts.

Discussion

The adapted 3-C Model (Vu, Ferns, & Ananthram, Citation2022) provided a context-specific framework for researching how international student participants transition through challenges to secure placements. This model enabled considering data in context, facilitating the investigation of participants’ narratives of their experiences and perspectives, and factors influencing these experiences and perspectives.

Through applying the adapted 3-C Model, this study furthers transition theory (Anderson et al., Citation2012; Schlossberg, Citation1981) and the 3-C Model (Vu, Ferns, & Ananthram, Citation2022) in the context of international students’ engagement in securing placements. Transition theory does not clarify the interrelation among the 4S. Similarly, the 3-C Model does not explicitly indicate the interplay among the causes of challenges (i.e., undesired aspects of Situation, Self, and Support) or how this interplay affects the Strategies adopted by individuals. The above-mentioned limitations of transition theory and the 3-C Model are concisely addressed by the two models developed in this study. The model of causes of challenges to international students in securing placements () indicates that the interplay between undesirable personal factors (Self) and negative contextual factors (Situation & Support) causes two major challenges for students: limited placement availability and uphill competition with domestic peers. The 3-P Model of Student Engagement in Securing Placements () untangles students’ cognitive, attitudinal, and behavioral engagement in three stages of placement seeking: perceiving, planning, and performing. These two models are useful to inform research and practice that seeks to nurture student agency, particularly in relation to securing placements.

The two models ( and ) suggest that student agency refers to the capacity to (i) evaluate and interlink personal factors (Self) and contextual factors (Situation & Support) to identify the aspects of the present self that need improvement; (ii) accordingly set goals and generate strategies; and (iii) proactively mobilize personal and environmental resources to realize goals (Strategies).

Some student participants exercised agency through proactively identifying their desired future self (e.g., a successful applicant for a paid placement), which guided their subsequent action in seeking placements. Such proactivity is in line with Tran and Vu’s (Citation2018) observation that ‘agency for becoming’ precedes students’ actual engagement. Several student participants also proactively mobilized support sources in and outside their university to develop their present self to enhance capacity to secure placements. This agentic behavior by student participants is reflective of their ability to ‘draw on external opportunities to internalize experience’ (Tran & Vu, Citation2018, p. 177).

Practical implications

The research findings offer implications for strategies at the national, institutional, and individual levels (). As suggested by , challenges to international students in securing placements can be addressed by improving both students’ personal factors (Self) and contextual factors (Situation & Support). This discussion addresses the Australian higher education context as an example.

Table 4. Responses to challenges for international students in securing placements.

Addressing limited placement availability

The National WIL Strategy stipulates the imperative to ‘[i]ncrease opportunities for international students to participate in WIL’ (Universities Australia et al., Citation2015, p. 11). However, as a WIL staff member remarked, ‘employers are not controlled by the university, so employer perception has a massive impact on whether an individual will secure work or not’ (WS2). This highlights the critical role of government agencies in enhancing industry engagement through promoting the benefits of hosting international students and/or providing incentives.

Further, employer prejudice towards the collective international student cohort (e.g., communication incompetency) leads to unwillingness to host them (Tran & Vu, Citation2016). The onus is on universities and governmental agencies to enhance industry engagement by addressing employer prejudice stemming from overgeneralization of international students. As a WIL staff participant remarked, ‘employers are more likely to be persuaded if they can see the person rather than a subgroup’ of international students (WS4).

Addressing competition in securing placements

The Strategy also stresses the need to ‘[i]mprove the capacity for international students to participate in WIL opportunities’ (Universities Australia et al., Citation2015, p. 12). Despite emphasizing the imperative to ‘develop resources to increase the preparedness of international students to participate in WIL’ (p. 12), the Strategy does not explicitly state the importance of nurturing international students’ capacity to exercise agency to secure placements. It is essential for universities to nurture students’ agency in preparation for their transition into today’s fast-changing world of work (Vu, Bennett, & Ananthram, Citation2022). This includes enhancing students’ capacity to exercise agency in placement seeking and subsequent job seeking. Strategies to nurture student agency could be informed by the two models formulated in this study ( and ).

Limitation of the study

The study focused on international engineering students at an Australian university. Future cross-disciplinary and cross-institution research will provide additional perspectives. Comparative studies across universities could reveal the influence of institutional support and location (e.g., urban and remote institutions) on students’ experiences in securing placements.

Conclusion

This study established unique insights into how international students exercise agency to secure work placements. The findings address two gaps in the literature: (i) international students’ strategies in navigating challenges to secure work placements and (ii) a related research framework. Salient findings were distilled into the Perceiving-Planning-Performing Model (3-P Model, ), untangling international student participants’ cognitive, attitudinal, and behavioral engagement in perceiving (causes of) challenges, planning strategies to address challenges, and performing strategies to overcome challenges to secure placements.

International students face notable challenges caused by the interplay between personal factors (Self) and contextual factors (Situation & Support). Therefore, securing placements requires personalized ways of engagement, hence student agency. It is essential for educational institutions to support international students to build capacity for practicing agency. Further, strategic collaboration between educational institutions and governmental agencies is vital to enhancing employer engagement with international students. Improving international students’ capacity for securing placements and post-graduation employment will, in turn, enhance the potential of this student cohort as a source of labor force to address skills shortage in host countries.

Acknowledgement

Thai Vu is a recipient of an Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Anderson, M., Goodman, J., & Schlossberg, N. K. (2012). Counseling adults in transition: Linking Schlossberg's theory with practice in a diverse world (4th ed.). Springer Publishing Company.

- Aprile, K. T., & Knight, B. A. (2020). The WIL to learn: Students’ perspectives on the impact of work-integrated learning placements on their professional readiness. Higher Education Research & Development, 39(5), 869–882. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2019.1695754

- Australian Government. (2021). Australian strategy for international education 2021-2030. https://www.englishaustralia.com.au/documents/item/1461

- Australian Government. (n.d.). Visa conditions. https://immi.homeaffairs.gov.au/visas/already-have-a-visa/check-visa-details-and-conditions/conditions-list

- Bell, S. E. (2002). Photo images: Jo Spence’s narratives of living with illness. Health, 6(1), 5–30. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363459302006001442

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Creswell, J. W. (2012). Educational research: Planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research (4th ed.). Pearson.

- Creswell, J. W., & Poth, C. N. (2017). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches. Sage.

- Dean, B. A., & Campbell, M. (2020). Reshaping work-integrated learning in a post-COVID-19 world of work. International Journal of Work-Integrated Learning, 21(4), 355–364.

- Engineers Australia. (2019). Accreditation management system. https://www.engineersaustralia.org.au/About-Us/Accreditation/AMS-2019

- Felton, K., & Harrison, G. (2017). Supporting inclusive practicum experiences for international students across the social sciences: Building industry capacity. Higher Education Research & Development, 36(1), 88–101. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2016.1170766

- Ferns, S. J., Rowe, A. D., & Zegwaard, K. E. (2022). Advances in research, theory and practice in work-integrated learning. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003021049

- Gale, T., & Parker, S. (2014). Navigating student transition in higher education: Induction, development, becoming. In H. Brook, D. Fergie, M. Maeorg, & D. Michell (Eds.), Universities in transition: Foregrounding social contexts of knowledge in the first year experience (pp. 13–41). https://doi.org/10.20851/universities-transition-01

- Gribble, C., Blackmore, J., & Rahimi, M. (2015). Challenges to providing work integrated learning to international business students at Australian universities. Higher Education, Skills and Work-Based Learning, 5(4), 401–416. https://doi.org/10.1108/HESWBL-04-2015-0015

- IJWIL (International Journal of Work-Integrated Learning). (n.d.). Defining WIL. https://www.ijwil.org/

- Jackson, D. (2016). Deepening industry engagement with international students through work-integrated learning. Australian Bulletin of Labour, 42(1), 38–61.

- Jackson, D. (2017). Exploring the challenges experienced by international students during work-integrated learning in Australia. Asia Pacific Journal of Education, 37(3), 344–359. https://doi.org/10.1080/02188791.2017.1298515

- Kay, J., McRae, N., & Leoni, R. (2020). Two institutional responses to work-integrated learning in a time of COVID-19: Canada and Australia. International Journal of Work - Integrated Learning, 21(5), 491–503.

- Natanasabapathy, P., & Maathuis-Smith, S. (2019). Philosophy of being and becoming: A transformative learning approach using threshold concepts. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 51(4), 369–379. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2018.1464439

- Pham, T., Bao, D., Saito, E., & Chowdhury, R. (2018). Employability of international students: Strategies to enhance their experience on work-integrated learning (WIL) programs. Journal of Teaching and Learning for Graduate Employability, 9(1), 62–83. https://doi.org/10.21153/jtlge2018vol9no1art693

- Riessman, C. K. (2012). Analysis of personal narratives. In J. F. Gubrium, J. A. Holstein, A. Marvasti, & K. D. McKinney (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of interview research: The complexity of the craft (2 ed., pp. 367–379). SAGE. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781452218403

- Saldaña, J. (2016). The coding manual for qualitative researchers (3rd ed.). Sage.

- Schlossberg, N. K. (1981). A model for analyzing human adaptation to transition. The Counseling Psychologist, 9(2), 2–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/001100008100900202

- Tran, L. H. N. (2019). Motivations for studying abroad and immigration intentions: The case of Vietnamese students. Journal of International Students, 9(3), 758–776. https://doi.org/10.32674/jis.v0i0.731

- Tran, L. H. N., & Nguyen, T. M. D. (2019). Developing and validating a scale for evaluating internship-related learning outcomes. Higher Education, 77(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-018-0251-4

- Tran, L. T. (2016). Mobility as ‘becoming': A Bourdieuian analysis of the factors shaping international student mobility. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 37(8), 1268–1289. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2015.1044070

- Tran, L. T., & Vu, T. T. P. (2016). ‘I’m not like that, why treat me the same way?’ The impact of stereotyping international students on their learning, employability and connectedness with the workplace. The Australian Educational Researcher, 43(2), 203–220. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-015-0198-8

- Tran, L. T., & Vu, T. T. P. (2018). Agency in mobility: Towards a conceptualisation of international student agency in transnational mobility. Educational Review, 70(2), 167–187. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2017.1293615

- Universities Australia, BCA, ACCI, AIG, & ACEN. (2015). National strategy on work integrated learning in university education. http://cdn1.acen.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/National-WIL-Strategy-in-university-education-032015.pdf

- Vu, T., Bennett, D., & Ananthram, S. (2022). Learning in the workplace: Newcomers’ information seeking behaviour and implications for education. Studies in Continuing Education, https://doi.org/10.1080/0158037X.2022.2041593

- Vu, T., Ferns, S., & Ananthram, S. (2022). Challenges to international students in work-integrated learning: A scoping review. Higher Education Research & Development, 41(7), 2473–2489. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2021.1996339

Appendix

Sample student interview questions.