ABSTRACT

In response to challenges emerging in society, universities are searching for ways to innovate their courses through novel institutional educational policies and practices. Those efforts, however, are often not informed by knowledge about course innovation characteristics university-wide, and are often not supported by processes of reflection questioning the ‘who’, ‘how’ and ‘for what’ of course innovations. This study applied the multifaceted analytical Course Innovation Framework (CIF) in order to explore characteristics of a large set of intended course innovations in a higher education institution in the Netherlands. The application of the CIF enabled a descriptive analysis of multiple characteristics of the intended course innovations. This analysis unveiled university-wide course innovation trends, upon which university stakeholders reflected in order to responsibly guide and transform policy and practices. The study findings show how the application of the CIF helps to gather situated knowledge on university-wide innovation trends, and how reflection on these trends empowers stakeholders to deliberate the culture and values of educational innovation they wish to promote within their institution.

Introduction

Higher education institutions are currently perceiving a need to re-think their educational policies and practices in the light of several challenges in society. These include the need to address increasingly complex sustainability concerns (König, Citation2015), the process of internationalisation (den Brok, Citation2018), the increasing commitment to bridging science and society (Sengupta et al., Citation2020), and technological advances (Krause, Citation2022). In their attempts to respond to these challenges, universities are introducing various innovations in their curricula and courses. Among these, they are developing novel educational visions and strategies in connection to society (Kamp, Citation2020); experimenting with transformative pedagogies, student-centred learning approaches and formative assessment (López, Citation2017), and implementing new blended and online teaching methods (Bruggeman et al., Citation2021).

Higher education institutions try to stimulate innovation by implementing educational policies and plans and by deploying funding opportunities (e.g., Anakin et al., Citation2018; Lašáková et al., Citation2017). Examples are university-based course-innovation calls and teaching-development grants (e.g., Malfroy & Willis, Citation2018). Those efforts encourage innovation and enable higher education curricula and courses to respond to the challenges mentioned above. However, as suggested by Ellström (Citation2011), consolidating innovation in an institution demands that such logic of ‘production’ is complemented by a logic of ‘development’. While the logic of production focuses on implementing innovation policies and practices, the logic of development looks at the innovation efforts as a source of knowledge development. The latter process thus entails the capacity to build knowledge by exploring the characteristics of innovations. The knowledge acquired can, in turn, inform processes of reflection and responsible deliberation on future innovation policy and practices within an institution. As suggested by Boyce (Citation2003), the challenge of successful transformation and change is not so much about implementing new initiatives as it is about developing and sustaining new ways of knowing and acting within an institution.

Literature acknowledges the pertinence of exploring curricular and course innovations encouraged or funded within a university (Dexter & Seden, Citation2012; Hum et al., Citation2015). In particular, exploring innovations taking place across the university – and thus beyond one single course or programme – is considered an effective method of overcoming scattered efforts and sustaining long-term transformation in a higher education institution (e.g., Bajada et al., Citation2019; Kandiko Howson & Kingsbury, Citation2021). This type of exploration has the potential to collect knowledge that provides valuable support for innovation efforts. However, as mentioned in a literature review by Cai (Citation2017), no studies to date have provided applicable frameworks which comprehensively explore the multiple characteristics of educational innovation efforts, also throughout an entire institution.

In an attempt to respond to this need, and with a focus on course innovation, this study applies the multifaceted analytical Course Innovation Framework (CIF) describing multiple course innovation characteristics. The CIF was constructed conceptually by the authors of this paper (see Tassone et al., Citation2022), by drawing from innovation-based literature and documents. The present study takes a next step by empirically applying the constructed CIF, thereby demonstrating its actual utility. In this endeavour, this study asks the question, ‘How can educational innovation in universities be informed by applying the multifaceted analytical Course Innovation Framework?’. This question is addressed by applying the CIF to a large set of proposed and funded course innovations in one middle-sized life sciences university in the Netherlands, Wageningen University & Research (WUR). Similar to other universities, WUR is investing in educational innovation to best address the issues of sustainability concerns, increased diversity of the student population, the need for flexible learning paths and the use of digital tools (Graham, Citation2018).

By applying the CIF in this university context, this study elaborates on the added value of this application in generating knowledge of university-wide innovation trends and consequent reflection and responsible deliberation on policy and practices. This study could serve as an example to other universities dealing with similar challenges. It could help educational leaders (e.g., managers, policy makers) and educators to comprehensively explore course innovations in order to guide future educational innovation policy and practices in their own context. The paper first presents the CIF. A description of the study context and methodology follows. Then, the findings and reflections sections illustrate the outcomes of the CIF application in the study context. Discussion and conclusions, highlighting the added value of the CIF application, end the paper.

The multifaceted analytical Course Innovation Framework (CIF)

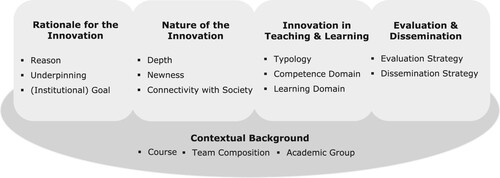

In order to gain insights into various facets of intended course innovations in the university in question, this study used the multifaceted analytical Course Innovation Framework (CIF). The objective of the CIF application is to gather knowledge about trends in course innovation characteristics university-wide, which in turn can support reflection and inform policy and practices. The CIF is structured along five clusters. Each cluster describes various course innovation characteristics, and each characteristic is composed of various descriptors. An elucidation of how the CIF was developed, the CIF clusters, characteristics and descriptors can be found in Tassone et al. (Citation2022), together with the literature underpinning all those aspects. This section summarises only the main aspects of the framework. The following presents the CIF clusters (in bold) and their characteristics (in bullet points), while the subsequent text briefly introduces those clusters. Then, in the section ‘Findings Phase 1’, each CIF cluster, characteristic, and related descriptors, are mapped through tables and further described in the text.

The ‘Contextual Background’ cluster explores the contextual characteristics of the course innovation (e.g., Brans & Bayram-Jacobs, Citation2016). The ‘Rationale for the innovation’ cluster explores the drives of an innovation and its goals (e.g., Hannan et al., Citation1999; WUR, Citation2017). The ‘Nature of the Innovation’ cluster explores the character of the innovation and its connectivity with society (e.g., Gupta et al., Citation2006; Tassone et al., Citation2018). The ‘Innovation in Teaching & Learning’ cluster explores the teaching and learning components and domains (e.g., Barth et al., Citation2007; Van den Akker, Citation2003). The ‘Evaluation & Dissemination’ cluster explores evaluation and dissemination aspects (e.g., Jacobs, Citation2000; Southwell et al., Citation2010).

Context and methodology

Over the years, WUR has encouraged educational innovation by elaborating novel educational visions through policy (e.g., WUR, Citation2017) and by establishing an Educational Innovation Fund. This fund enabled educators to receive grants for innovations in their courses. In order to receive a grant, educators had to submit proposals for course innovation projects with a duration of one to two years, describing all details of their intended innovation and implementation plans. These proposals were judged by a team of university professors and support staff. Within this context, this study explored the proposed course innovations by means of the CIF application, through multiple methodological steps organised in two phases, which will now be elucidated.

Phase 1

Collection of relevant material and CIF interrater reliability

Material describing the proposed innovations was gathered by the authors of this paper. This entailed collecting the texts of all 88 course innovation project proposals funded by the Educational Innovation Fund throughout a three-year period (2015–2017). Then, the consistency in the application of the CIF characteristics and descriptors was explored. Two of the authors individually applied the framework to analyse a sample of six innovation proposals under study, selected randomly from the three years (i.e., two randomly selected proposals from each of the three years). The text of each of the six proposals was analysed with the intent to identify whether the proposed innovation embodied the CIF characteristics, and related descriptors for each cluster. The two authors used their analysis of this random sample to calculate the interrater reliability coefficient Cohen’s Kappa. The resulting Cohen’s Kappa was 0.80, denoting good interrater reliability of the CIF.

Application of the CIF and data analysis

The CIF was applied by the four authors to analyse the characteristics of all 88 course innovation project proposals. The text of each proposal was scrutinised by using the CIF as frame of reference. This scrutiny enabled also to specify sub-descriptors qualifying each CIF descriptor. SPSS software was used to perform a descriptive analysis across all innovation proposals, with a focus on mapping the percentage of proposals that embodied a certain CIF characteristic, descriptor and sub-descriptor, within each cluster. The trends in course innovation characteristics university-wide, that became apparent by means of this analysis, are presented later on in under the section ‘Findings Phase 1’.

Table 1. Descriptive analysis of the ‘Contextual Background’ cluster.

Table 2. Descriptive analysis of the ‘Rationale for the Innovation’ cluster.

Table 3. Descriptive analysis of the ‘Nature of the Innovation’ cluster.

Table 4. Descriptive analysis of the ‘Innovation in Teaching & Learning’ cluster.

Table 5. Descriptive analysis ‘Evaluation & Dissemination’ cluster.

Phase 2

Reflection workshop

In order to reflect on the identified university-wide trends in course innovation characteristics, a workshop with university stakeholders was organised. An invitation to attend the workshop was sent to the educational policy unit and to the education and learning sciences group of WUR. The workshop was attended by four teachers, five educational policy-makers and six educational researchers. During the workshop two authors presented the trends identified from the CIF application, as showed in . Participants were invited to reflect on those trends and to deliberate on their implications for university policy and practices. Participants used flip charts to write down and to present their thoughts. The text written on flip charts and notes written by the authors were summarised on paper by the first author after the workshop. Then, to make sure the participants’ reflections were accurately summarised, the draft was sent to all participants. The minor changes suggested were integrated and the summary of the participants’ reflection was finalised by the authors. Those reflections are outlined in a later section titled ‘Reflections Phase 2’.

Further reflection

The university-wide trends in course innovations () and the workshop reflections just mentioned were presented by the authors to two leaders of the university management team. The knowledge built through this presentation provided the ground for further reflection and choices in terms of policy and practices. The outcomes of this reflection are mentioned at the end of ‘Reflections Phase 2’.

Findings Phase 1: university-wide trends in course innovations

This section describes the trends that became evident when the CIF was used to explore multiple characteristics of the 88 course innovations destined for implementation in the university context. For each CIF cluster, this section elaborates on the identified university-wide trends, noting what characteristics, and related descriptors and sub-descriptors, appear predominant or are relatively rare. This elaboration is supported by tables depicting, for each CIF cluster, the percentage of proposals (100% = 88) that embody a certain characteristic, descriptor and sub-descriptor. Note that multiple sub-descriptors within the same characteristic can be simultaneously applied to one single proposal.

‘Contextual background’ cluster

As depicted in , the analysis of the course characteristic revealed that the innovations concerned both BSc or MSc course levels, with more emphasis on the former; and concerned various types of courses, with considerable emphasis on obligatory courses and less emphasis on elective courses. Most innovations had a diversified team composition and fostered collaborations between teachers and others, such as student assistants and the education support staff. The involvement of organisations in society was modest, and even more modest was the involvement of programme directors. With regard to the academic groups (i.e., the university group departments working on different academic fields), the proposed innovations were not evenly distributed across the groups of the university. In fact, across the time span of three years, only a few academic groups submitted and received funding for multiple course innovation proposals, while the majority of academic groups submitted and received funding for only one proposal. Proposals fostering collaborations across groups were scarce.

‘Rationale for the innovation’ cluster

As depicted in , investigation of the reason characteristic clarified the ‘why’ of the proposed innovations. Most innovations were driven by challenges in teaching, learning, and assessment and were especially intended to guarantee quality and performance of students’ learning; they were driven as well by changes in student population, especially the increasing number of students, which called for new ways of teaching and assessment. To a lesser degree, innovations were related to challenges with logistics and resources and focused especially on stimulating efficiency, e.g., efficiently organising the teaching activities for a larger group of students. Hardly any proposals mentioned changes in society as a direct reason for innovations in their courses.

Concerning the underpinning, most of the proposed innovations were grounded in experiential underpinning, meaning that they were informed by experiences gained during classes. For example, observation during classes might clarify that innovations in course activities were needed to increase students’ engagement. Few innovations were grounded in theoretical underpinning, meaning that they were informed by educational and learning theories and concepts. For example, one particular learning taxonomy might inspire the re-thinking of the learning outcomes of a course. Similarly few innovations were grounded on empirical underpinning and thus on findings about classroom practices. For example, inspection of the students’ course evaluation might reveal learning challenges faced by students. For a small proportion of proposals, the underpinning could not be defined.

Finally, analysis of the goals of the proposed innovations revealed that all innovations met pre-set university educational goals. The innovations especially attempted to foster rich learning environments, as when the innovation promoted students’ active participation and the provision of effective feedback; and flexibility and personal learning paths, as when the innovation promoted personalised learning trajectories to accommodate students’ individual needs. In a more modest way, innovations focused on ensuring high quality scientific knowledge, as when the innovation promoted the enhancement of solid state-of-the-art knowledge. The proposed innovations tended to connect to multiple university educational goals simultaneously. No new possible goals, beyond those already set by the universities, were identified.

‘Nature of the innovation’ cluster

As depicted in , examination of the newness of the proposed innovations showed that the majority of innovations had an exploitative character. Exploitative innovations focused on drawing from already known pedagogical tools and approaches and on implementing existing good practices, such as replacing a classroom lecture with pre-existing digital tools, for example a video clip providing knowledge on a certain topic. Only a few innovations had an explorative character. Explorative innovations focued on creating something new and on experimenting with newly created tools and approaches, such as the invention of a new game engaging students in complex decision-making activities.

With regard to the depth of the proposed innovations, analysis made clear that most innovations had an incremental character. Incremental innovations focused on superficial changes within a course while the underlying features of the whole course design remained the same. For example, updating certain learning materials could help the course to function more effectively without implying fundamental changes in the course design. Only a few innovations had a radical character. Radical innovations focused on making a significant change in the design of a course by fundamentally altering the learning objectives, assessment and other aspects of the course. For example, transforming a mono-disciplinary course into a trans-disciplinary one would call for radical changes in the objectives and overall design of the course. An innovation, whether it was radical or incremental with regard to the changes in course design, could be either explorative or exploitative with regard to the changes in the pedagogical tools and approaches. Nonetheless, the combination of incremental and exploitative was most common, and the other combinations, including radical and explorative, relatively rare.

As for the connectivity academia-society characteristic, the innovations proposed to enhance this connectivity were scarce. Very few innovations concerned forms of education for society, which focused on enhancing the students’ understanding of and engagement with societal challenges, e.g., in relation to climate change challenges. Similarly, few innovations concerned the development of forms of education with society, focusing on facilitating an interplay between students and stakeholders in society.

‘Innovation in teaching and learning’ cluster

As depicted in , in terms of typology of the proposed innovations, the study made clear that almost all innovations focused on implementing digital learning materials & resources such as video and software. Many innovations aimed to foster changes in the learning location (at home, in a lab); learning activities (lecture, feedback activities); and a more flexible learning time (before or after class). Some proposals focused on innovations in the assessment strategy (essay writing, field performance); the grouping strategy (learning alone, learning in groups); and the non-digital learning material & resources (handbooks, articles). Only very few proposals focused on changing course rationale, or objectives and content of the course.

With regard to the competence domain, almost half of the proposed innovations intended to foster academic competence such as information literacy, scientific writing. The innovations were also intended to foster operational competence and life competence, albeit to a lesser degree. Operational competence concerned capabilities for becoming a professional beyond academia, such as consultancy competence or teaching competence. Life competence focused on types of competence that are not bound to a specific profession or context and enable students to responsibly navigate their complex world, such as intercultural competence or ethical competence.

The learning domains within which students learn and develop can be diverse. Most of the innovations intended to foster cognitive learning, which is concerned with thinking processes, for example processes of knowledge development or application of knowledge to solve a problem. However, various other domains such as social, metacognitive, affective, and psychomotor learning domains were at least partly intended to be fostered as well. The social learning domain focused on development of social processes like collaborative processes and communication; the metacognitive learning domain focused on processes of metacognition such as planning and reflecting; the affective learning domain concerned affectivity, including motivation and values; while the psychomotor learning domain concerned physical/kinaesthetic processes such as behaviour and use of technologies in labs.

‘Evaluation and dissemination’ cluster

As depicted in , evaluation of the characteristic of evaluation strategy made clear that more than half of the proposed innovations did not include a strategy for evaluating the quality of an innovation. Some innovations contemplated the inclusion of an evaluation strategy without specifying how the evaluation process would take place, while a few others did include and specify the strategy adopted, such as a formative evaluation identifying improvements to be made throughout an ongoing innovation, or a summative evaluation helping to assess the outcome of the innovation.

Finally, with regard to the dissemination strategy, findings indicated that most innovations intended to adopt a dissemination for understanding strategy focusing on providing detailed knowledge about the implemented innovation, e.g., through a journal article providing insights into the content of the innovation. Only a few innovations adopted a dissemination for action strategy focusing on sharing practical insights about the innovation in order to support the possible uptake of the innovation in other contexts, e.g., through a training. Even fewer innovations contemplated dissemination for awareness, focused on raising awareness about the existence of the innovation through brief communications and advertisements, e.g., a flyer. Some proposals, however, did not explicitly mention any dissemination plan.

Reflections Phase 2: implications for policy and practices

The university-wide trends in course innovations just elucidated and the related just presented, were discussed with teachers, educational policy-makers and educational researchers in a workshop setting within the study context, as mentioned in the earlier section on ‘Context and Methodology’. The workshop participants reflected on those trends, spotted critical areas of interventions and defined implications for the university’s educational innovation policy and practices. This section summarises those reflections and related implications and ends with a short description of subsequent developments in policy and practices.

Reflections about the ‘who’ of the innovations

The trends emerging from the analysis of the ‘Contextual Background’ cluster, in relation to the academic group, revealed that innovation efforts were not evenly distributed across the university academic groups. The participants considered whether it would be possible to stimulate more engagement of teachers from less active groups, and across groups. Furthermore, the proposed innovations suggested the formation of a diverse team composition with cross-involvement of teachers, educational assistant and support staff. Still, discussion emerged among workshop participants as to whether the cross-engagement with programme directors and organisations in society could be further promoted. In connection to this last point, the trends related to the ‘Nature of the Innovation’ cluster made evident too that the connectivity academia-society was scarce and that forms of education in connection to society were overlooked.

In sum, the trends highlighted above supported a process of reflection about ‘who’ is involved or could be more actively involved in course innovations. The workshop participants acknowledged the inclusive character of some intended innovations. At the same time, they deliberated further enhancement of participation and cross-engagement in innovation efforts through educational policies and funding. The possibilities included offering educational support for proposing and implementing innovations to teachers that are part of academic groups less active in seeking innovation grants; and incentivising more complex inter – and trans-disciplinary collaborative efforts among academic groups, programme directors, and society at large.

Reflections about the ‘how’ of the innovations

The trends emerging from the analysis of the ‘Nature of the Innovation’ cluster, both in terms of newness and depth of the innovations, showed that innovations were rather conventional. They were primarily exploitative, focusing on the implementation of existing good practices, and incremental, focusing on relatively superficial adaptations in a course. While acknowledging the importance of such innovations, workshop participants considered the possibility of advocating more courageous and diverse forms of innovation, namely explorative innovation focusing on experimenting with new ideas, and radical innovation focused on the possibility of more radical changes in the design of a course. On this point, additional insights emerged when reflecting on the data set of multiple clusters, i.e., the ‘Nature of the Innovation’, ‘Rationale for the Innovation’, and ‘Innovation in Teaching & Learning’ clusters. It was remarked that the few explorative and radical innovations that had been proposed were, compared to the more conventional ones, characterised to a greater extent by theoretical underpinning, education for society, innovation of the rationale and objectives of the course, intended learning outcomes in the affective and in the metacognitive learning domain, and enhancement of life competence. Those insights led workshop participants to observe that those more challenging and diverse forms of innovation could be more actively encouraged.

In sum, the trends highlighted in the previous paragraph supported a process of reflection about ‘how’ those innovations were shaped or could be better shaped. The participants deliberated enhancement of courageous and diverse innovation efforts. They suggested to distinguish between a fund enabling the implementation of exploitative and incremental innovations and good practices, and a fund enabling experimentation with more explorative and radical innovations, allowing also for possible failures to learn from. Participants also discussed incentivising innovations focusing on theoretical underpinning, education for society, affective and metacognitive forms of learning, and development of life competence.

Reflections about the ‘for what’ of the innovation

The trends emerging from the ‘Rationale for the Innovation’ cluster made explicit that all course innovations fulfilled pre-set educational innovation institutional goals, (e.g., stimulating active student participation). Fulfilling pre-set institutional goals was an important condition for receiving the grant. This, however, left open the question to what extent educators felt encouraged to focus on other goals they wished to pursue, beyond the pre-set institutional goals. Moreover, the analysis of the reasons for innovating showed that course innovations were predominantly problem-based and thus driven by the resolution of a concrete problem experienced within a certain course, e.g., coping with an increasing number of students. This was further corroborated by the trends visible when examining the underpinning of the innovations, which was above all experiential, and thus grounded in the concrete problems experienced by educators in their classroom practices. In addition, the analysis of the ‘Evaluation and Dissemination’ cluster showed that the majority of innovations did not consider an evaluation strategy. This raised concerns among the participants because, while the university was investing in creating innovations, there was no evaluation of the quality of those innovations, or of what goals were achieved. The fact that a good part of the innovations contemplated plans for a dissemination strategy reinforced even further the interest in formalising evaluation efforts, as a means of being able to disseminate lessons learned and good practices.

In sum, the trends identified in the above paragraph supported a process of reflection about ‘for what’ the innovations were, or could be pursued. Participants deliberated on promoting quality of the innovations by various means. For example, they suggested encouraging reflections about the reason and the goal of the innovation, supporting the embedding of evaluation and dissemination strategies as an integral part of each innovation that received funding.

Development policy and practices

Finally, the study findings of phase 1 and the workshop reflections of phase 2 were shared by the authors with leaders of the university management team in the study context, as explained in the earlier section on ‘Context and Methodology’. This action was undertaken to foster further reflection and the possible development of educational policy and practices. Subsequently, the university management made some decisions touching upon some of the above implications. For example, if teachers wished to introduce course innovations, the university decided to offer educational support within and across various academic groups (the ‘who’), by assigning educational experts as early as the proposal development process. Also, a distinction was made between explorative and exploitative innovation by creating specific innovation funds for each of these (the ‘how’). Furthermore, educational innovation calls were expanded by requesting evaluation of proposed innovations (the ‘for what’). Proposals received only part of their funding in advance, while the remainder was paid only after evaluation took place.

The CIF, the study findings and reflections, were also used by the authors in professional development courses for educational leaders and educators in other universities, in the context of scholarship of teaching and learning (SOTL) and educational leadership courses. In those courses, for example, the CIF clusters and related list of characteristics, descriptors and sub-descriptors (as presented in ) were used to facilitate reflections on the characteristics of course innovations in other universities, and to foster inspiration when defining criteria for developing course innovation proposals and policies. Also, in those courses, the study findings and reflections were presented to enhance awareness about the relevance of gathering and reflecting upon university-wide innovation trends, through the CIF application.

Discussion and conclusions

In order to explore a large set of intended course innovation projects in a higher education institution in the Netherlands, this study successfully applied the multifaceted Course Innovation Framework (CIF). Through the analysis of collected course innovation proposals funded by the university, the study explored the extent to which those proposed innovations embodied the CIF facets or characteristics. This made it possible to detect university-wide trends in course innovation characteristics in the study context, which are presented in in the earlier section ‘Findings Phase 1’. The trends thus identified were presented to university stakeholders. Knowledge of those trends helped stakeholders to obtain a broad overview of what was predominant and what was overlooked in the course innovation endeavours, and to identify evidence-informed considerations for university policy and practices. For example, the trends emerging from the ‘Nature of the Innovation’ cluster, concerning newness, showed that many proposed innovations had an exploitative character and thus focused on implementing pre-existing good practices, while only a few had an explorative character and took the more risky path of experimenting with new ideas. Unveiling those trends enabled stakeholders to form an impression of the nature of university-wide innovation endeavours and to consider whether a change was desirable, for example by incentivising more explorative forms of innovation.

A first conclusion that can be drawn from this study is that the CIF application can help in overcoming the scattered knowledge and atomistic character of course innovation endeavours by gathering evidence about course innovation trends at an institutional level, thus building a solid basis for reflection and decision-making. The added value of the CIF application lies in its potential to support the creation of new course innovation policy and practices, not only in response to societal challenges at the macro-level (Chatterton & Goddard, Citation2000), or to the motivation of an individual educator in a particular course at the micro-level (Hasanefendic et al., Citation2017), but especially in response to situated knowledge about university-wide course innovation trends collected at the meso-level. This form of situated knowledge can shed light on innovation facets in an institution and help to identify critical areas for intervention, thus empowering social learning and institutional transformation. By generating situated knowledge based on the exploration of innovation efforts within a university, the CIF endorses an institutional logic of ‘development’ (Ellström, Citation2011), which as explained earlier, regards innovation as a source of knowledge development. This study shows that the knowledge gathered on the basis of such logic through the CIF can complement, and can actually guide, an institutional logic of ‘production’ focused on implementing and funding innovation.

Furthermore, the trends emerging through the application of the multifaceted CIF enabled stakeholders to reflect upon the culture of innovation they wanted to promote in their institution, as presented in the earlier section ‘Reflections Phase 2’. Such reflections ultimately converged upon a constellation of three overarching topics of deliberation for guiding policy and practices, which include ‘who’ is involved in the innovations, ‘how’ these innovations are shaped, and ‘for what’ these innovations are conducted. Those topics constitute some of the fundamental moral points of focus in responsible innovation endeavours (Bennink, Citation2020). By providing evidence of multiple innovation trends, the application of the CIF has triggered a process of deliberation on those topics in this study case. For example, stakeholders deliberated offering educational support for course innovations in order to encourage the participation of teachers less involved in innovation within and across academic groups (the ‘who’). They also considered encouraging more explorative and radical innovation, such as shifting from a mono-disciplinary to a trans-disciplinary course design and experimenting with new tools and approaches (the ‘how’). Finally, they contemplated promoting a culture of quality of innovation by requesting evaluation of course innovations in order to ponder their purpose and outcomes (the ‘for what’).

A second conclusion that can be drawn from this study is that the application of the CIF can promote also a logic of ‘reflection’ and processes of deliberation concentrating on at least three themes, including the ‘who’, ‘how’ and ‘for what’ of the course innovation. The added value of the CIF application thus lies in its potential to illustrate non-prescriptive multiple trends that can empower university stakeholders to responsibly reflect on and deliberate those themes, bearing in mind the institutional values and culture of educational innovation they wish to promote through policy and practices. Choices about reforming education in an institution are in fact also the outcome of the educational visions and values of the university stakeholders (Annala & Mäkinen, Citation2017).

Limitations of the CIF application, and possibilities for future research, are worth mentioning at this point. The CIF itself has some limitations. Certain CIF characteristics are connected to each other and overlap at least in part. This situation applies to the competence and learning domains (an academic competence can often concern a cognitive learning process), as well as to depth and newness (a significant change in the course design can often require the exploration of new teaching approaches). As it stands now, the CIF does not show connections and overlaps across characteristics. It can also be questioned whether there are other relevant innovation characteristics not yet integrated in the framework, especially if the CIF would be applied to other levels of innovation (e.g., educational programmes). With regard to the data upon which the CIF was applied, it can be challenging to rely on the text of course innovation proposals as a data source. On a few occasions during our study, explanations of certain aspects of the proposal text were short, abstract or totally absent, making it difficult or impossible to identify certain characteristics (e.g., the underpinning of some innovations was categorised as ‘not defined’).

Additionally, the implications described for policy and practices concerning the ‘who’, the ‘how’ and the ‘for what’ of the innovation are based on the reflections of stakeholders when discussing the trends identified in innovation characteristics. While this suggests that the multiple trends emerging from the application of the CIF enable reflections on those three themes, the CIF however does not yet include prompts that directly facilitate stakeholders’ reflections on those themes. It is also important to note that the implications described in this study are context-specific, as they are related to the trends emerging in a specific university. Nevertheless, literature on educational curricula broadly acknowledges the need to address some of those implications; indeed, the need to enhance participation, connectivity with society, and quality of innovation are also highlighted elsewhere (Tassone et al., Citation2018). Furthermore, this study shows that the CIF findings supported educators and educational leaders in engaging into reflective and deliberative processes, while the leaders (specifically the managers) were the ones to pursue implementation of new policy and practices based on the outcomes of those processes in our study context. The study however did not focus on exploring factors that can hamper reflection and implementation choices, as for example personal resistance to change, lack of participatory decision-making and slow management operations (Lašáková et al., Citation2017).

Future studies might further expand the CIF and explore its application in other contexts, and in cross-institutional initiatives. Such studies might also consider other levels of innovation (e.g., educational programmes), other data sources (e.g., interviews), the inclusion of reflection prompts, and the elaboration of factors that can help or hamper reflections and implementation of new institutional educational innovation choices, based on the application of the CIF. Also, this research focused on intended innovations. However, new insights could emerge when using the CIF to explore the rich interplay between intended innovation, and implemented and attained innovation, as suggested in literature (McCrory et al., Citation2021).

To conclude, this study demonstrates how to apply the CIF and suggests the CIF can be a relevant tool for higher education institutions that are searching for ways to guide and transform course innovation policy and practices. The added value of the CIF application lies in its potential to unveil university-wide trends in course innovation characteristics and, based on those trends, to empower an institutional logic of reflection and value-based decision-making that can help consolidating responsible course innovation policy and practices.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Anakin, M., Spronken-Smith, R., Healey, M., & Vajoczki, S. (2018). The contextual nature of university-wide curriculum change. International Journal for Academic Development, 23(3), 206–218. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2017.1385464

- Annala, J., & Mäkinen, M. (2017). Communities of practice in higher education: contradictory narratives of a university-wide curriculum reform. Studies in Higher Education, 42(11), 1941–1957. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2015.1125877

- Bajada, C., Kandlbinder, P., & Trayler, R. (2019). A general framework for cultivating innovations in higher education curriculum. Higher Education Research & Development, 38(3), 465–478. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2019.1572715

- Barth, M., Godemann, J., Rieckmann, M., & Stoltenberg, U. (2007). Developing key competencies for sustainable development in higher education. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, 8(4), 416–430. https://doi.org/10.1108/14676370710823582

- Beddewela, E., Anchor, J., & Warin, C. (2021). Institutionalising intra-organisational change for responsible management education. Studies in Higher Education, 46(12), 2789–2807. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2020.1836483

- Bennink, H. (2020). Understanding and managing responsible innovation. Philosophy of Management, 19(3), 317–348. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40926-020-00130-4

- Boyce, M. E. (2003). Organizational learning is essential to achieving and sustaining change in higher education. Innovative Higher Education, 28(2), 119–136. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:IHIE.0000006287.69207.00

- Brans, C., & Bayram-Jacobs, D. (2016). Bottom-up views on innovation in higher engineering education. A qualitative study within three technical universities. 4TU Centre for Engineering Education.

- Bruggeman, B., et al. (2021). Experts speaking: Crucial teacher attributes for implementing blended learning in higher education. The Internet and Higher Education, 48, 100772. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2020.100772

- Cai, Y. (2017). From an analytical framework for understanding the innovation process in higher education to an emerging research field of innovations in higher education. The Review of Higher Education, 40(4), 585–616. https://doi.org/10.1353/rhe.2017.0023

- Chatterton, P., & Goddard, J. (2000). The response of higher education institutions to regional needs. European Journal of Education, 35(4), 475–496. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-3435.00041

- Den Brok, P. (2018). Cultivating the growth of life-science graduates: On the role of educational ecosystems. Inaugural lecture. Wageningen University and Research. https://research.wur.nl/en/publications/cultivating-the-growth-of-life-science-graduates-on-the-role-of-e

- Dexter, B., & Seden, R. (2012). ‘It’s really making a difference’: how small-scale research projects can enhance teaching and learning. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 49(1), 83–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/14703297.2012.647786

- Ellström, P. E. (2011). Informal learning at work: Conditions, processes and logics. The Sage Handbook of Workplace Learning, 105–119.

- Graham, R. (2018). The global state of the art in engineering education. MIT Research report. https://www.rhgraham.org/reports/.

- Gupta, A. K., Smith, K. G., & Shalley, G. E. (2006). The interplay between exploration and exploitation. The Academic of Management Journal, 49(4), 693–706. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2006

- Hannan, A., English, S., & Silver, H. (1999). Why innovate? Some preliminary findings from a research project on ‘innovations in teaching and learning in higher education’s. Studies in Higher Education, 24(3), 279–289. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079912331379895

- Hasanefendic, S., Birkholz, J. M., Horta, H., & van der Sijde, P. (2017). Individuals in action: bringing about innovation in higher education. European Journal of Higher Education, 7(2), 101–119. https://doi.org/10.1080/21568235.2017.1296367

- Hum, G., Amundsen, C., & Emmioglu, E. (2015). Evaluating a teaching development grants program: Our framework, process, initial findings, and reflections. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 46, 29–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2015.02.004

- Jacobs, C. (2000). The evaluation of educational innovation. Evaluation, 6(3), 261–280. https://doi.org/10.1177/13563890022209280

- Kamp, A. (2020). Navigating the landscape of higher engineering education. Coping with decades of accelerating change ahead. 4TU Centre for Engineering Education.

- Kandiko Howson, C., & Kingsbury, M. (2021). Curriculum change as transformational learning. Teaching in Higher Education, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2021.1940923

- König, A. (2015). Changing requisites to universities in the 21st century: Organizing for transformative sustainability science for systemic change. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 16, 105–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2015.08.011

- Krause, K. L. D. (2022). Vectors of change in higher education curricula. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 54(1), 38–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220272.2020.1764627

- Lašáková, A., Bajzíková, Ľ, & Dedze, I. (2017). Barriers and drivers of innovation in higher education: Case study-based evidence across ten European universities. International Journal of Educational Development, 55, 69–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2017.06.002

- López, M. A. R. (2017). European higher education area-driven educational innovation. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 237, 1505–1512. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2017.02.237

- Malfroy, J., & Willis, K. (2018). The role of institutional learning and teaching grants in developing academic capacity to engage successfully in the scholarship of teaching and learning. International Journal for Academic Development, 23(3), 244–255. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2018.1462188

- McCrory, G., Holmén, J., Holmberg, J., & Adawi, T. (2021). Learning to frame complex sustainability challenges in place: Explorations into a transdisciplinary “challenge Lab” curriculum. Frontiers in Sustainability, 2, 63. https://doi.org/10.3389/frsus.2021.714193

- Sengupta, E., Blessinger, P., & Mahoney, C.2020). University-community partnerships for promoting social responsibility in higher education. Emerald Group Publishing.

- Southwell, D., Gannaway, D., Orrell, J., Chalmers, D., & Abraham, C. (2010). Strategies for effective dissemination of the outcomes of teaching and learning projects. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 32(1), 55–67. https://doi.org/10.1080/13600800903440550

- Tassone, V. C., Biemans, H. J., den Brok, P., & Runhaar, P. (2022). Mapping course innovation in higher education: A multi-faceted analytical framework. Higher Education Research & Development, 41(7), 2458–2472. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2021.1985089

- Tassone, V. C., O’Mahony, C., McKenna, E., Eppink, H. J., & Wals, A. (2018). (Re-)designing higher education curricula in times of systemic dysfunction: A responsible research and innovation perspective. Higher Education, 76(2), 337–352. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-017-0211-4

- Van den Akker, J. (2003). Curriculum perspectives: An introduction. In J. Van den Akker, W. Kuiper, & U. Hameyer (Eds.), Curriculum landscape and trends (pp. 1–10). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-1205-7_1

- Wang, C. L. (2015). Mapping or tracing? Rethinking curriculum mapping in higher education. Studies in Higher Education, 40(9), 1550–1559. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2014.899343

- WUR. (2017). Vision for education Wageningen University and Research, the next step. https://www.wur.nl/en/show/Wageningen-University-Vision-for-Education.htm.