Abstract

Why are some family SMEs more innovative than others? We use the heterogeneity within family SMEs to explore how their socioemotional wealth (SEW) affects innovativeness. The ubiquity of smaller family firms means that their innovativeness is critical for policymakers, such as those in the United Arab Emirates, seeking innovation-led development. We conduct a multi-case study analysis of SEW and innovativeness in fourteen family SMEs based in the United Arab Emirates. Participants were from a range of sectors and across the employment size-range of family SMEs. None of the most innovative family SMEs had highly family-centric socioemotional wealth. High family-centricity was however evident in all the least innovative firms who survived on reputation and incremental customer or supplier-driven improvements. The least innovative firms were amongst the smallest but not the youngest, with firm age not influential for innovativeness. The paper proposes redressing family-centric SEW preferences to raise the innovativeness of family SMEs. This will involve longer-term decision-making that gives greater consideration to the interests of external stakeholder as well as future generations of the family.

RÉSUMÉ

Pourquoi certaines PME familiales sont-elles plus innovantes que d’autres ? Nous utilisons l’hétérogénéité existant au sein des PME familiales pour examiner comment leur richesse socio-émotionnelle (RSE) affecte leur capacité d’innovation. L’omniprésence des petites entreprises familiales signifie que leur capacité d’innovation est essentielle pour les décideurs politiques, tels que ceux des Émirats arabes unis, en recherche d’un développement basé sur l’innovation. Nous procédons à une analyse par étude de cas multiples de la richesse socio-émotionnelle et de la capacité d’innovation dans quatorze PME familiales basées dans les Émirats arabes unis. Les participants provenaient de divers secteurs et de toutes les tailles d’emploi des PME familiales. Aucune des PME familiales les plus innovantes n’avait une richesse socio-émotionnelle fortement centrée sur la famille. Une forte centralité familiale s’est toutefois révélée évidente dans toutes les entreprises les moins innovantes qui ont survécu grâce à leur réputation et à des améliorations progressives apportées par les clients ou les fournisseurs. Les entreprises les moins innovantes étaient parmi les plus petites, mais pas les plus récentes, l’âge de l’entreprise n’influençant pas la capacité d’innovation. Cet article propose de rectifier les préférences familiales en matière de richesse socio-émotionnelle pour accroître la capacité d’innovation des PME familiales. Cela impliquerait une prise de décision à plus long terme, prenant davantage en compte les intérêts des parties prenantes externes, ainsi que des futures générations de la famille.

Introduction

Family firms, especially smaller ones, are the dominant form of enterprise in many countries (Miller, Steier, and Le Breton-Miller Citation2016) and their innovativeness continues to attract critical attention (Basco Citation2017; Chrisman et al. Citation2015; De Massis et al. Citation2015). Researchers have successfully adapted various theories – resource-based view, agency, and stewardship - to explain family firm innovativeness (Basco Citation2017; Berrone, Cruz, and Gómez-Mejía Citation2012). There are also ongoing efforts to create dedicated family firm theory such as socioemotional wealth (SEW), where further development and testing are needed (Hu and Hughes Citation2020; Pearson, Holt, and Carr Citation2014).

This study responds to continuing calls for more research into the heterogeneity of family firms, rather than the differences between family and non-family firms (Hall and Nordqvist Citation2008; Jennings, Reay, and Steier Citation2015; Newbert and Craig Citation2017). Calabrò et al. (Citation2019) stress the need for a more contextualized understanding of family firms and innovation, while Dibrell and Memili (Citation2019) urge further exploration of heterogeneity of their SEW priorities. Hence, this paper explores family firm innovation using the SEW perspective in the context of the United Arab Emirates (UAE), a regional setting where there is a dearth of research (McKelvie et al. Citation2014; Zahra Citation2011). Our research focus is ‘family SMEs’, family-owned business operating in the UAE with no more than 500 employees. Our purpose is exploratory, in line with most case study investigations of family firms (Leppäaho, Plakoyiannaki, and Dimitratos Citation2016), framed by the research question: How does SEW affect the innovativeness of family SMEs in the United Arab Emirates?

Context is also important as the values and norms of the research setting can influence the behavior of family firms (Howorth et al. Citation2010). The UAE has a national strategy intended to promote an innovation culture, especially among SMEs, aiming to make the country one of the most innovative in the world by 2021 (UAE National Innovation Strategy Citation2015). This national ambition has clear imperatives for family SMEs. The UAE is a fast-developing country in the Middle East, ranking ahead of other Arab countries in the ease of doing business (The World Bank Citation2018). When facing high technological and market dynamism, firms must be more innovative to survive (Kach et al. Citation2016; Miller et al. Citation2015). However, in this national context, Arab traditional family values embracing protectiveness of members and the inclination to put family interests above all else, such as innovation, align with the dominant perception of SEW priorities (Lalonde Citation2013). In contrast, recent local research finds that an innovation culture is more influential in promoting innovation than social or societal culture (Matroushi, Jabeen, and All Citation2018). Family firms in this region do appear to be less open to new thinking, less inclined to implement new ideas, and tend to stick with what they know and how they operate (PWC 2016). According to the Ministry of Economy (Citation2017), the broad SME sector accounts for over 94% of all companies and 86% of private sector employment. Over 80% of these SMEs are family-owned and dominate many industries. The innovativeness of these family SMEs is critical to the success of this strategy in the UAE (PWC 2016), posing a major challenge to policymakers. Hence it is vital to understand the variation in innovativeness among such firms and, as a corollary, offer insights on the long-term survival of non-innovative family SMEs (Chrisman et al. Citation2015).

We contribute to the continuing work on extending the perceptions of SEW and how the resulting heterogeneity affects family firm behavior, including innovativeness (Calabrò et al. Citation2019; Filser et al. Citation2018; Gast et al. Citation2018; Miller et al. Citation2015). We find SEW priorities that remain highly family-centric are inimical for firm-level innovativeness. Such firms also tend to remain small, surviving on their local reputation and with the ongoing support of customers and suppliers (Martínez-Alonso et al. Citation2020). The next section discusses the literature and is followed by an explanation of the research design. We then report findings, conclusions, policy implications and suggestions for further research.

Literature review

We explore the heterogeneity of family SMEs when “extended priorities” (Calabrò et al. Citation2019: 345; Miller and Le Breton-Miller Citation2014) are introduced into SEW, and how this affects the innovativeness of such firms. This is a growing area of research within which there are mixed and sometimes contrary findings (Debicki et al. Citation2017; Filser et al. Citation2018; Gast et al. Citation2018; Gómez-Mejía, Neacsu, and Martin Citation2019; Ng, Dayan, and Di Benedetto Citation2019; Swab et al. Citation2020).

Innovativeness

Innovation is the successful implementation of new ideas in an organization in the form of new products, services or processes that are a change to normal routines (Anderson et al. Citation2015). Innovation is a key element for organization performance (Camisón and Villar-López Citation2014; Tidd and Thuriaux‐Alemán Citation2016), including in family firms (Kellermanns et al. Citation2012). There is no question that family firms can be more innovative than non-family firms due to longer investment horizons (Cruz and Nordqvist Citation2012; Miller, Steier, and Le Breton-Miller Citation2003; Zellweger, Nason, and Nordqvist Citation2012); less bureaucracy (Hsu and Chang Citation2011; Chu Citation2011); and the patient capital and trust within families (Berrone, Cruz, and Gómez-Mejía Citation2012). Duran et al. (Citation2016) note that, while family firms invest few resources into research and development, they have better innovation outcomes including enhanced competitive advantage (Chirico and Salvato Citation2016). There is also no doubt that some family firms can be innovative and grow over long periods (Bergfeld and Weber Citation2011). But other family firms may be unwilling to pursue innovation because this needs a strong ongoing commitment of resources to R&D, exposing the family assets to significant risks (Zahra et al. Citation2014). Higher risk aversion, coupled with a lack of skills and financial resources, perpetuates an unwillingness to innovate in family firms (Gómez-Mejía et al. Citation2007; Gupta et al. Citation2010; Rosenbusch, Brinckmann, and Bausch Citation2011). External collaborations in support of innovation may also be perceived to endangering autonomy and the unique family ethos, threats the family firm is unwilling to countenance (Gómez-Mejía et al. Citation2011a).

Socioemotional wealth

SEW was first coined by Gómez-Mejía et al. (Citation2007) and serves to integrate stakeholder management and institutional theory to provide a holistic analytical framework for family firms (Berrone, Cruz, and Gómez-Mejía Citation2014). There is still debate about how it affects behavior, specifically innovativeness, what dimensions it should contain (Newbert and Craig Citation2017; Brigham and Payne Citation2019), and how these are to be measured. Following Berrone, Cruz, and Gómez-Mejía (Citation2012, 259), in what some would see now see as a restricted and homogenous notion of SEW, this theoretical perspective posits that “family firms are typically motivated by, and committed to, the preservation of their SEW, referring to non-financial aspects or ‘affective endowments’ of family owners”. Hence, family firm owners’ willingness to commit resources to a potentially risky activity such as innovation would extend beyond purely financial considerations such as return on investment (Hauck and Prügl Citation2015). Considerations around SEW priorities are also central to recent treatments of the paradox of ability and unwillingness underlying family firm innovativeness (Block Citation2012; Chrisman et al. Citation2015; Covin et al. Citation2016; Fahed-Sreih and El-Kassar Citation2017; Gast et al. Citation2018). Despite the centrality of SEW to our understanding of family firm behavior and performance, Calabrò et al. (Citation2019) report only a few empirical studies on family firm innovation using SEW as the theoretical lens while advocating further research on SEW with extended priorities and goals. Previous quantitative studies of the relationship between SEW-innovation have produced mixed results (Hauck and Prügl Citation2015; Filser et al. Citation2018: Gast et al. Citation2018).

What these studies do find is that SEW priorities themselves are indeed heterogeneous, reflecting the different circumstances and characteristics of the family members involved in the business over time. Miller and Le Breton-Miller (Citation2014) and Miller et al. (Citation2015) challenge the hitherto restricted homogenous notion of SEW in which family interests dominate those of all other (non-family) stakeholders. Calabrò et al. (Citation2019: 345) endorse this by recommending further research that “builds on the idea that [family firms] may attach substantial importance to non-family stakeholders to ensure firm survival and the goodwill of the community toward the family.” Craig and Newbert (Citation2020) also recommend broadening the SEW discourse beyond its original restricted scope to include the interests of non-family stakeholders.

Miller et al. (Citation2015) dichotomize this extended notion of SEW as either family-centric or business-centric, the former giving clear preference to the family while valuing and exploiting ‘familiness’ (Habbershon Citation2006). The family is favored ahead of the business with nepotistic appointments and an intent to preserve family control and influence through intra-family succession events. Innovation would be disavowed as being hazardous for the family’s endowment (Duran et al. Citation2016; Block et al. Citation2013). Family-centric SEW can be criticized as underpinning a very short-term, even myopic, focus to family firm decision-making, one that prioritizes the self-interest of the ‘family’ ahead of any obligations, moral or otherwise, to those external stakeholders, such as customers and suppliers, upon whom the family business depends (Berrone, Cruz, and Gómez-Mejía Citation2014; Newbert and Craig Citation2017). Business-centric SEW can place the interests of the business and key stakeholders ahead of family claims and is the more likely to endorse innovation to build a stronger business, one capable of performing well and supporting into the future (Miller and Le Breton-Miller Citation2014).

Firm size and age

The tradition of strong family values in the UAE (Lalonde Citation2013) may indeed supress the heterogeneity of SEW among family firms. Hence, any variation in innovativeness will reflect other drivers of innovation, such as firm size and age. On the matter of firm size and innovation, larger family firms generally have advantages. They will have greater sales and production volumes over which to recoup the returns from product or process innovations. Larger firms have a greater resource base to carry the risks inherent in the pursuit of innovation albeit through a larger bureaucracy and the internal politicization of the innovation process (Herrera and Sánchez-González Citation2013). Firm size has also been shown to influence the relationship between SEW and family firm strategic decision-making (Fang et al. Citation2016). Smaller family-owned firms are invariably more restricted (Cohen and Klepper Citation1996; Shefer and Frenkel Citation2005). Fernández and Nieto (Citation2005) find that these smaller firms generally face extra size-related challenges in accessing the resources and capabilities needed to not only create but also sustain a competitive advantage. Thus, we expect firm size to be positively associated with innovativeness within family SMEs, especially if the family-centricity of SEW also weakens over time with increased firm size (Habbershon Citation2006; Schulze, Lubatkin, and Dino Citation2003), i.e. innovativeness increasing with generational changes due to family successions (Zahra et al. Citation2014). Larger family firms should be more innovative if family control and influence weakens allowing more non-family managers to influence key decisions associated with innovation (Anderson and Reeb Citation2004; Morck and Yeung Citation2003; Stewart and Hitt Citation2012).

Firm age may also capture this as family firms develop through inter-generational successions and attitudes change toward growth, size, and innovation (Berrone, Cruz, and Gómez-Mejía Citation2014; Clifford, Nilakant, and Hamilton Citation1991; Howorth et al. Citation2010; Howorth and Hamilton Citation2012; Woodfield and Husted Citation2019) and an increasing number of non-family members appear among senior management of family businesses and on the board (Fang et al. Citation2016; Howorth et al. Citation2010). The imperative of family harmony and continuity (Chirico Citation2008; Gilding, Gregory, and Cosson Citation2015) and the preservation of the family endowment may also wane overtime as family size falls and other career options present to possible family successors. As the family control and influence reduces, these businesses become less family-centric in their SEW and more able and willing to embrace innovation (Schulze, Lubatkin, and Dino Citation2003; Hauck and Prügl Citation2015). Larger and older family firms are a dominant construct in explaining firm-level innovativeness. These firms should be more innovative due to their scale, economies of growth, and waning family-centric SEW as family successions bring in both new generations and more non-family members into senior management levels.

Summary and research question

While high family-centricity may raise the ability to innovate, it can also decrease the willingness to innovate by reinforcing the need to preserve the family estate in perpetuity (Li and Daspit Citation2016; Rosenbusch, Brinckmann, and Bausch Citation2011; Werner, Schröder, and Chlosta Citation2018). There is also heightened unwillingness when innovation requires external collaboration with professional expertise (Classen et al. Citation2012) or the recruitment of knowledge-intensive managers (Gómez-Mejía et al. Citation2011a). Studies have confirmed a negative relationship between innovativeness and the degree of family control and influence, reflecting the unwillingness to compromise the family’s affective endowment (Gómez-Mejía et al. Citation2011b; Martínez-Alonso et al. Citation2020; Munari, Oriani, and Sobrero Citation2010). However, such is the heterogeneity within family firms, several recent studies report relationships between degree of family control and influence and innovativeness as either null (Filser et al. Citation2018; Krasnicka and Steinerowska-Streb Citation2019) or positive and necessary (Gast et al. Citation2018). National policy could seek selectively to resource and fund the growth of family firms, hoping that such initiatives will over time reduce the family-centricity of SEW. However, if family firms, larger and smaller, older, or younger, choose to maintain tight family-centricity, they are then less likely to engage in innovative activities, confounding any association between size and innovativeness (Revilla and Fernandez Citation2012). Hence our research question: How does SEW affect the innovativeness of family SMEs in the United Arab Emirates?

Research design and methods

A multiple-case design is used, following Yin (Citation2014), to investigate innovativeness in fourteen family SMEs in the UAE. Multiple cases are necessary to capture the heterogeneity of smaller family firms and innovation (De Massis et al. Citation2015; Gibbert, Ruigrok, and Wicki Citation2008; Graebner and Eisenhardt Citation2004). The design can also provide more robust findings based on pattern matching logic (Yin Citation2014). We used five selection criteria:

Majority of the firm’s ownership is held by one owning family

At least two members of the owning family hold key managerial positions

All firms had been trading for at least 3 years prior to the field study

All firms had less than 500 employees

Firms were selected to ensure variation in size and industry sector

The first two criteria are our definition of ‘family business’. There is still no consensus on a definition of a family business and we accept that some will view this definition as too restrictive (see Howorth et al. Citation2010). However, majority family ownership has been used in many previous studies and other types of family firms could not readily identified. The third criterion was to allow enough time for any innovation to be developed, especially among the younger firms. The upper size limit of 500 employees confined our sample to one accepted definition of ‘SME’ (OECD Citation2005) while ensuring a range of firm sizes.

We filtered family firms from the database of Khalifa Fund for Enterprise Development and other UAE directories, and then classified these by employment size and industry sector to obtain variation within the sample (Chrisman and Patel Citation2012). Invitation letters were emailed to 210 potential informants and, after several rounds of phone and email follow-ups, fourteen family firms agreed to participate fully in the field study, a relatively large number for a qualitative inquiry. All our SMEs were surviving at the time of the study and so some survivor bias will arise. We were unable to contact owners of family firms that had gone out of business.

The approach means becoming immersed in comprehensive information on each firm and building an understanding from the emerging patterns (De Massis and Kotlar Citation2014; Patton Citation2001; Yin Citation2014). Semi-structured interviews were carried out with either the founding family owner or the next generation family manager. Interviews lasted between 50 minutes and two hours. An interview protocol ensures consistency in the data collection process, outlining key steps and procedures to be followed before, during and after the interview. (The interview guide is in Appendix 1.) A native Arabic speaker with research experience was present during each interview to interpret when necessary. Professional transcribers converted each recording into a written document. The native Arabic speaker conducted follow-up telephone interviews when necessary to clarify information and obtain missing data. Secondary information such as company catalogues, websites, newsletters, and interviewer notes were triangulated with the interview data to enhance construct validity and reliability. The structured section of the interview yielded operational measures of innovativeness following Grundström, Öberg, and Rönnbäck (Citation2012), and SEW centricity based on the criteria used by Kellermanns et al. (Citation2012). These served to focus the unstructured section of the interview on the wider issues of the nature of innovation and the importance of family.

Most quantitative studies measure innovativeness using subjective self-ratings by single informants on multi-item Likert scales where sample sizes do allow internal validity to be confirmed (e.g. Eggers et al. Citation2013; Filser et al. Citation2018; Gast et al. Citation2018). External validity of such measures has to assume that informants have accurate and consistent perceptions of their own innovativeness and that of competitors. In this qualitative study, innovativeness is assessed in interviews by first ascertaining the frequency with which each family firm introduces new products, services, or processes. If the firm introduced one or none in the last three years, it is classified initially as ‘low’; at least three new introductions in three years is deemed ‘high’ intensity. Other firms are classified as ‘moderate’. These classifications were then confirmed by further questions about how our informant’s innovativeness level compared with direct competitors and their innovation process, if there was one (see Interview Guide, Appendix 1). The innovations reported were predominantly incremental in nature, involving mainly improved or new products or services, confirming the findings of Alberti and Pizzurno (Citation2013).

Building on Miller et al. (Citation2015), we extend the measure of family centricity using two dimensions of SEW (see Berrone, Cruz, and Gómez-Mejía Citation2012): (1) family control and influence, including the extent to which non-family members hold senior management positions, and (2) the expressed desire for intra-family transfer ownership to the next generation (following Gilding, Gregory, and Cosson Citation2015). On the first dimension SEW, there is a degree of family control and influence in all our firms given our definition included majority family ownership. Where non-family members are not involved in senior management and there is a strong expressed desire for succession to the next generation of the family, family-centricity is deemed ‘high’. Where non-family members are already among the senior management and there is a weak or no desire at all for continued intra-family succession, then family-centricity is ‘low’. Other combinations are ambiguous, e.g. non-family as senior managers but strong desire to ensure succession and are rated ‘moderate’ on family-centric SEW.

Data analysis followed the steps recommended in previous studies (De Massis and Kotlar Citation2014; Marshall and Rossman Citation2011) and by Gioia, Corley, and Hamilton (Citation2013). We read through the interview transcripts and secondary data several times to get a comprehensive understanding of each firm, organizing the emerging themes into categories using diagrams, tables, and highlighting text (by hand). Then NVivo 12 analysed the information on each firm, arranging properties into the categories identified in the previous step. These first-order categories included types of innovation; motivation to innovate; challenges to innovation; R&D activities; competitive advantage; family control and influence; and succession intentions. The relevant text extracts were then re-arranged within each category, generating second-order codes. For example, under ‘motivation to innovate’, we grouped effectiveness, problem solving, customer demands, and competitor pressures, which we re-coded into a separate category called ‘necessity to innovate’. Emerging categories were crosschecked between firms in an iterative manner until theoretical saturation with no new categories emerging. (A data structure table following Gioia, Corley, and Hamilton Citation2013 is in Appendix 2.) Finally, to help elucidate patterns, we classified firms according to their employment size into three categories following Kushnir (Citation2010): ‘micro’ = 10 or fewer employees; ‘small’ with 11 to 50 employees; and ‘medium’ having between 50 and 500 employees.

Findings

The goal of qualitative research study is to find and explain patterns emerging from rich data (Attride-Stirling Citation2001; Cavana, Delahaye, and Sekaran Citation2001; Yin Citation2014). lists our firms by size within each level of innovativeness. Within the limits of multi-case methods, this pattern is consistent with a strong inverse relationship between our two-dimensional measure of family-centric SEW, and firm-level innovativeness. We develop our findings under four sub-themes: patterns of SEW, firm size and innovativeness; contrasting high and low innovators; pattern mismatches; and, finally, the survival of non-innovative family SMEs.

Table 1. Profile of the smaller family firms in this study.

Patterns of SEW, firm size and innovativeness

There is no association here between firm size and age in this group of firms (insignificant rank correlation = +0.07) because we have several non-innovative firms that are both old and micro (firms 10, 12, 13, 14). Firms such as these, while not experiencing much growth, have nevertheless survived decades without being innovative. Using the pattern matching approach (Yin Citation2014), the seven most innovative firms comprise the three largest firms but also four smaller firms (firms 4, 5, 6, 7). While five of the six least innovative firms are micro, firm size is not a prerequisite for innovation. None of the ‘high’ innovative firms have highly family-centric SEW, in sharp contrast to all of the least innovative firms who remain highly family-centric. Continuing with this approach, when we consider the seven ‘high’ innovative firms (1 through 7), none have retained a high level of family centric SEW and only one (firm 7) is in the micro size category. Of the seven least innovative firms (8 through 14), only one, firm 8, is medium-sized and has not retained high family-centricity. The degree of family-centricity is clearly playing an important role in distinguishing between the most and the least innovative of these family SMEs: where family-centricity is high, innovativeness is always low (firms 9 through 14), despite differences in firm size. Conversely when family-centricity weakens (firms 1 through 8), innovativeness is usually high, with the exception of the moderate level of innovativeness in firm 8. Of the seven most innovative firms, three are medium; three are small, and one is micro, employing only ten people. The final pattern between firm size and family-centricity is also apparent with five of the six micro firms retaining high family-centricity but, of the eight larger SMEs, only one (firm 9) is highly family-centric. The pattern between firm size and innovativeness is apparent but less consistent than that between family-centricity and innovativeness, suggesting that the centricity of SEW is more influential for innovativeness than firm size. This finding is interesting given the importance of traditional family values in the UAE which may have limited the heterogeneity of SEW, suppressing any relationship with innovativeness.

Contrasting high and low innovators

summarizes the main patterns and provides selected extracts from firms with exhibiting high and low levels of innovativeness.

Table 2. Innovation in smaller family firms.

The largest three firms (1, 2, and 3) employ between 120 and 400 people. These are mature businesses with some erosion of family control, reflecting mainly the introduction of non-family members into senior management positions. These firms are well-resourced and so more willing to support innovation. Firm 1 has an R&D department and an annual budget allocation to support innovation. Firm 2 has pursued a growth strategy of unrelated diversification (jewellery, watches, real estate, food) and now has third-generation family involved in the business. It has also professionalized its management team with several non-family members now in key managerial positions and able to drive innovation. As stated by the third-generation manager:

‘Our competitiveness is based on reputation of service and selling premium quality product. I am very proud of my grandfather’s reputation in the industry. Our current priority is to expand our business, that’s why we are investing in sweet manufacturing business now, slightly different from our current business in trading and service’. (Firm 2)

The three small firms (4, 5 and 6) employ between 15 and 30 people and include the youngest business, Firm 5, founded in 2015. Firms 4 and 5 are two of the most innovative in the study, and among the smallest. Both founding families are very focused on the business and on innovation, and no intention to retain the business in family ownership. Firm 4 has a non-family member in the top management team, devotes 20-30% of its annual expenditures on innovation. Firm 5, the youngest firm in the study, had already allowed non-family members to spearhead several new service developments. Both these innovative firms are highly customer-focused on their respective markets:

‘Innovation is important in our business…[it] is essential to stay in the market because our market is fast changing and the only way to adapt is to be directly involved in the business’ (Firm 4)

‘[We aim to] stay the first kids’ club in strategy and innovation. We have meetings with the parents, surveys that ask what they are looking for in a kids’ club, and assessment and performance where parents can come to see the progress of their kids’ (Firm 5)

‘It does not make sense to give an outsider to take in charge of the company as I already have capable sons to take the business forward. But this depends on their goals. If my sons want to continue and expand this family business than they are more than welcome. If they want to do something else there would be no holding back. It’s totally up to them!’ (Firm 6)

Pattern mismatches

The previous discussion of our findings has been based around the replication logics evident especially when exploring quite subtle patterns (Yin Citation2014). The imprecision of the pattern matching is due to only three firms: 7, 8, and 9 – see .

Table 3. Firms that do not pattern-match.

Firm 7 has higher innovativeness and weaker family-centricity than observed in other micro firms. Firm 8 has lower innovativeness than we would expect given both its medium size (80 employees) and lower family-centricity. Firm 9 has maintained a high degree of family-centricity given its size (46 employees) but is much less innovative than other firms of similar size. This firm has twelve family members involved in running the business but no outsiders, and still considers itself to be a relatively small business. They do not engage in innovation as they see their business as operating in a buy-then-sell merchandizing model.

Survival of non-innovative family SMEs

Given the importance of innovation for competitive advantage, how do non-innovative family firms survive? Among our six micro firms, five of these (Firm 10-14) match the expected pattern of high family-centricity and low innovativeness, indeed no innovation at all in some instances. All these firms have survived without significant innovation for over 10 years and four have been in operation for at least 30 years. According to De Massis et al. (Citation2015), the ability to innovate is measured by owner’s discretion to direct, allocate, add to, or dispose of resources for innovation purposes. As such, this group of firms might have a high ability to innovate but also a high unwillingness to so do, exemplifying the innovation paradox (Chrisman et al. Citation2015). These micro firms are useful in addressing the corollary to the paradox: if innovation is important for firm performance, how are smaller family firms able to survive? These firms do not emphasize innovation, relying instead on other sources of competitive advantage (Agyapong, Ellis, and Domeher Citation2016). summarizes our qualitative data on these firms and our interpretation of their competitive advantage.

Table 4. Survival strategies in low innovative family firms.

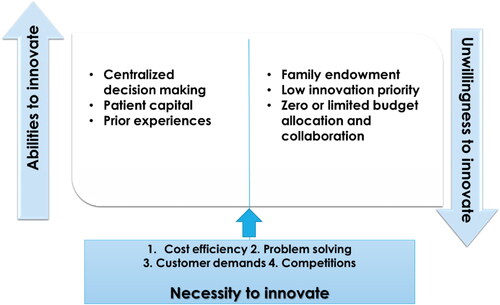

The lack of innovation has not yet forced the exit of these micro family firms. They have each been able to develop other bases of competitive advantage other than they have however all been driven by necessity to regularly adopt small incremental changes under pressure from customers, competitors, and suppliers (Martínez-Alonso et al. Citation2020). Necessity trumps unwillingness to permit enough adaptation to survive but changes are indeed modest and low risk. There is of course some considerable irony in this finding bearing in mind Newbert and Craig (Citation2017) recent critique of (family centric) SEW as being narrowly self-interested and pursued without any ‘moral obligation to protect and promote the interests of those on whom their businesses depend’ (Newbert and Craig Citation2017). Here we demonstrate the vital nature of such dependence on external stakeholders for the long-term survival of some family SMEs that remain too family-centric for their own good. In , we conceptualize how the construct of necessity, reflecting the task environment of customers, competitors, and suppliers, acts as the balance point between ability to innovate and willingness to do so.

This diagram shows the necessity to innovate (see Data structure table in Appendix 2) as a pivot point reflecting an amalgam of external drivers such as the need for cost efficiency, customer demands and other competitive pressures. As these stakeholder pressures grow, the pivot point moves from right (unwilling to innovate) toward the left (abilities to innovate), when some changes can be made. Once done, the pivot returns to the right of the scale and the family-centricity of SEW remains unchanged throughout.

Conclusions and further research

We find some family SMEs in the UAE to be much more innovative than others and associate this with their lower family-centric SEW (Memili and Dibrell Citation2019). These innovative family SMEs are proactive in their innovative endeavors although these are nevertheless mainly incremental and product-oriented, with a strong customer-driven focus. Among these innovative firms, some have never been family-centric while in others, it has waned over time: family firms do not have to be old or large before family-centricity weakens. Our least innovative firms remain highly family-centric, consistent with the traditional family values of the UAE, yet survive based on their local reputation and close relationships with their customers and suppliers. Any innovation in these firms is the result of intermittent prompting by these external stakeholders, the very parties whose interests do not concern family-centric SMEs.

This paper also shows the complex interactions among SEW, firm size and innovativeness. Resource-based scholars highlight the importance of having more resources thus indicating larger size improves firms’ innovation position (Stewart and Hitt Citation2012). From the patterns revealed in this study, firm size matters for family SME innovation, but it is not necessary: our seven most innovative firms included one micro firm and three small firm (cf. Blomback and Wigren Citation2009). However, of the six least innovative firms, five are micro firms and one is small. Centricity of SEW drives innovation in these firms although this in turn appears linked to firm size. Our results suggest that SEW may be more influential for innovativeness than firm size, in these family SMEs in the UAE.

Low entry barriers and the ease of doing business in the UAE ensures ongoing competition pressure, especially from foreign firms, and family SMEs will continue to need prompting to be sufficiently innovative. The UAE National Innovation Strategy for 2021 seeks to promote a culture of innovation generally across all businesses, including family SMEs. We do not dispute this emphasis (Matroushi, Jabeen, and All Citation2018) but our findings suggest that more attention should now be given to mitigating the effects of family-centric SEW, alongside other considerations such as R&D incentives to increase innovation inputs. There could be more education provided on the professionalization of family business management by developing non-family managers (Hall and Nordqvist Citation2008; Howorth et al. Citation2010); the need for succession planning to include key non-family stakeholders (Fox, Nilakant, and Hamilton Citation1996; Gilding, Gregory, and Cosson Citation2015); and the building of more trust-based relationships with these external stakeholders (Newbert and Craig Citation2017).

The research reported here has important limitations. Our findings have no statistical validity. This is a single-country qualitative study with all the firms based in UAE and these findings cannot be extended to other times and places. Our scope was confined to surviving family SMEs and we were not able to extend our exploration to family SMEs who had gone out of business. This is one gap that could be addressed in future research. The influence of higher generation involvement on SEW priorities (Le Breton–Miller and Miller Citation2013; Gu, Lu, and Chung Citation2019) also merits closer study, especially as generational transfer can be a key opportunity to bring change into a family business. A comparison of the innovativeness of firms that have remained family owned through succession and those that have not would also provide useful insights into the effects of SEW. Such studies could be conducted in the Middle East to redress the current Western emphasis in the family business literature.

Author’s declaration

This manuscript has not been published or presented elsewhere in part or in entirety and is not under consideration by another journal. All study participants provided informed consent, and the study design was approved by the appropriate ethics review board. We have read and understood your journal’s policies, and we believe that neither the manuscript nor the study violates any of these. There are no conflicts of interest to declare.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Poh Yen Ng

Poh Yen Ng is Senior Lecturer in Canterbury Christ Church University at the United Kingdom. She has held previous academic positions at United Arab Emirates University and RMIT University. She received her PhD in Management from University of Canterbury, New Zealand. Her research focuses on entrepreneurship, family business, innovation and strategy. Her work has been published in Business Strategy and Environment, Journal of Business Research, Technology Analysis and Strategic Management, Journal of Asia Pacific Business, International Review of Business Research and elsewhere.

Robert T. Hamilton

Bob Hamilton is Emeritus Professor in the Department of Management, Marketing and Entrepreneurship at the University of Canterbury, where he has also served as MBA Programme Director, Faculty Dean and Head of Department. Bob’s PhD is from the University of London. He has held previous academic appointments at London Business School; University of Stirling; and is Visiting Professor at Strathclyde University’s Hunter Centre for Entrepreneurship. Current teaching and research interests are in entrepreneurship and business development, with recent publications on the dynamics of high-growth firms in New Zealand and the regional impact of these firms. He is currently a Consulting Editor of the International Small Business Journal. He has published in Journal of Management Studies, Strategic Management Journal, Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, Journal of Small Business Management, International Marketing Review, International Small Business Journal, International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour & Research, and elsewhere.

References

- Agyapong, A., F. Ellis, and D. Domeher. 2016. “Competitive Strategy and Performance of Family Businesses: moderating Effect of Managerial andInnovative Capabilities.” Journal of Small Business & Entrepreneurship 28 (6): 449–477.

- Alberti, F. G., and E. Pizzurno. 2013. “Technology, Innovation and Performance in Family Firms.” International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation Management 17 (1/2/3): 142–161.

- Anderson, B. S., P. M. Kreiser, D. F. Kuratko, J. S. Hornsby, and Y. Eshima. 2015. “Reconceptualizing Entrepreneurial Orientation.” Strategic Management Journal 36 (10): 1579–1596.

- Anderson, R. C., and D. M. Reeb. 2004. “Board Composition: Balancing Family Influence in S&P 500 Firms.” Administrative Science Quarterly 49 (2): 209–237.

- Attride-Stirling, J. 2001. “Thematic Networks: An Analytic Tool for Qualitative Research.” Qualitative Research 1 (3): 385–405.

- Basco, R. 2017. “Where Do You Want to Take Your Family Firm? A Theoretical and Empirical Exploratory Study of Family Business Goals.” BRQ Business Research Quarterly 20 (1): 28–44.

- Bergfeld, M. M. H., and F. M. Weber. 2011. “Dynasties of Innovation: Highly Performing German Family Firms and the Owners’ Role for Innovation.” International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation Management 13 (1): 80–94.

- Berrone, P., C. Cruz, and L. R. Gómez-Mejía. 2012. “Socio-Emotional Wealth in Family Firms: Theoretical Dimensions, Assessment Approaches, and Agenda for Future Research.” Family Business Review 25 (3): 258–279.

- Berrone, P., C. Cruz, and L. R. Gómez-Mejía. 2014. “Family-Controlled Firms and Stakeholder Management: A Socioemotional Wealth Preservation Perspective.” Chapter 10 in the Sage Handbook of Family Business, edited by L. Melin, M. Nordqvist, and P. Sharma, 179–195. Hershey, PA, USA: IGI Global.

- Block, J. 2012. “R&D Investments in Family and Founder Firms: An Agency Perspective.” Journal of Business Venturing 27 (2): 248–265.

- Block, J., D. Miller, P. Jaskiewicz, and F. Spiegel. 2013. “Economic and Technological Importance of Innovations in Large Family and Founder Firms: An Analysis of Patent Data.” Family Business Review 26 (2): 180–199.

- Blomback, A., and C. Wigren. 2009. “Challenging the Importance of Size as a Determinant of CSR Activities.” Management of Environmental Quality: An International Journal 20 (3): 255–270.

- Brem, A., and K. I. Voigt. 2009. “Integration of Market Pull and Technology Push in the Corporate Front End and Innovation Management—Insights from the German Software Industry.” Technovation 29 (5): 351–367.

- Brigham, K. H., and G. T. Payne. 2019. “Socioemotional Wealth (SEW): Questions on Construct Validity.” Family Business Review 32 (4): 326–329.

- Calabrò, Andrea, Mariangela Vecchiarini, Johanna Gast, Giovanna Campopiano, Alfredo Massis, and Sascha Kraus. 2019. “Innovation in Family Firms: A Systematic Literature Review and Guidance for Future Research.” International Journal of Management Reviews 21 (3): 317–355.

- Camisón, C., and A. Villar-López. 2014. “Organizational Innovation as an Enabler of Technological Innovation Capabilities and Firm Performance.” Journal of Business Research 67 (1): 2891–2902.

- Cavana, R. Y., B. L. Delahaye, and U. Sekaran. 2001. Applied Business Research – Qualitative and Quantitative Methods, Milton, Australia: Wiley.

- Chirico, F. 2008. “Knowledge Accumulation in Family Firms – Evidence from Four Case Studies.” International Small Business Journal: Researching Entrepreneurship 26 (4): 433–462.

- Chirico, F., and C. Salvato. 2016. “Knowledge Internalization and Product Development in Family Firms: When Relational and Affective Factors Matter.” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 40 (1): 201–229.

- Chrisman, J. J., J. H. Chua, A. De Massis, F. Frattini, and M. Wright. 2015. “The Ability and Willingness Paradox in Family Firm Innovation.” Journal of Product Innovation Management 32 (3): 310–318.

- Chrisman, J. J., and P. C. Patel. 2012. “Variations in R&D Investments of Family and Nonfamily Firms: Behavioral Agency and Myopic Loss Aversion Perspectives.” Academy of Management Journal 55 (4): 976–997.

- Chu, W. 2011. “Family Ownership and Firm Performance: Influence of Family Management, Family Control, and Firm Size.” Asia Pacific Journal of Management 28 (4): 833–851.

- Classen, N., A. Van Gils, Y. Bammens, and M. Carree. 2012. “Accessing Resources from Innovation Partners: The Search Breadth of Family SMEs.” Journal of Small Business Management 50 (2): 191–215.

- Clifford, M., V. Nilakant, and R. T. Hamilton. 1991. “Management Succession and the Stages of Small Business Development.” International Small Business Journal: Researching Entrepreneurship 9 (4): 43–55.

- Cohen, W. M., and S. Klepper. 1996. “Firm Size and the Nature of Innovation within Industries: The Case of Process and Product R&D.” The Review of Economics and Statistics 78 (2): 232–243.

- Covin, J., F. Eggers, S. Kraus, C. Cheng, and M. Cheng. 2016. “Marketing-Related Resources and Radical Innovativeness in Family and Non-Family Firms: A Configurational Approach.” Journal of Business Research 69 (12): 5620–5627.

- Craig, J. B., and S. L. Newbert. 2020. “Reconsidering Socioemotional Wealth: A Smithian-Inspired Socio-Economic Theory of Decision-Making in the Family Firm.” Journal of Family Business Strategy 11 (4): 100353.

- Cruz, C., and M. Nordqvist. 2012. “Entrepreneurial Orientation in Family Firms: A Generational Perspective.” Small Business Economics 38 (1): 33–49.

- De Massis, A., F. Frattini, E. Pizzurno, and L. Cassia. 2015. “Product Innovation in Family versus Nonfamily Firms: An Exploratory Analysis.” Journal of Small Business Management 53 (1): 1–36.

- De Massis, A., and J. Kotlar. 2014. “The Case Study Method in Family Business Research: Guidelines for Qualitative Scholarship.” Journal of Family Business Strategy 5 (1): 15–29.

- Debicki, B. J., Graaff Van de, R. Randolph, and M. Sobczak. 2017. “Socioemotional Wealth and Family Firm Performance: A Stakeholder Approach.” Journal of Managerial Issues 29 (1): 82–111.

- Di Stefano, G., A. Gambardella, and G. Verona. 2012. “Technology Push and Demand Pull Perspectives in Innovation Studies: Current Findings and Future Research Directions.” Research Policy 41 (8): 1283–1295.

- Dibrell, C., and E. Memili. 2019. “A Brief History and a Look to the Future of Family Business Heterogeneity: An Introduction.” In The Palgrave Handbook of Heterogeneity among Family Firms, edited by C. Dibrell and E. Memili, 1–15. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Duran, P., N. Kammerlander, M. Van Essen, and T. Zellweger. 2016. “Doing More with Less: Innovation Input and Output in Family Firms.” Academy of Management Journal 59 (4): 1224–1264.

- Eggers, F., M. Kraus, M. Hughes, S. Laraway, and S. Snycerski. 2013. “Implications of Customer and Entrepreneurial Orientations for SME Growth.” Management Decision 51 (3): 524–546.

- Fahed-Sreih, J., and A. N. El-Kassar. 2017. “Strategic Planning, Performance and Innovative Capabilities of Non-Family Members in Family Businesses.” International Journal of Innovation Management 21 (07): 1750052.

- Fang, H. C., R. V. Randolph, E. Memili, and J. J. Chrisman. 2016. “Does Size Matter? The Moderating Effects of Firm Size on the Employment of Nonfamily Managers in Privately Held Family SMEs.” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 40 (5): 1017–1039.

- Fernández, Z., and M. J. Nieto. 2005. “Internationalization Strategy of Small and Medium-Sized Family Businesses: Some Influential Factors.” Family Business Review 18 (1): 77–89.

- Filser, M., A. De Massis, J. Gast, S. Kraus, and T. Niemand. 2018. “Tracing the Roots on Innovativeness in Family SMEs: The Effect of Family Functionality and Socioemotional Wealth.” Journal of Product Innovation Management 35 (4): 609–628.

- Fox, M., V. Nilakant, and R. Hamilton. 1996. “Managing Succession in the Family-Owned Business.” International Small Business Journal: Researching Entrepreneurship 15 (1): 15–25.

- Gast, J., M. Filser, J. P. Coen Rigtering, R. Harms, S. Kraus, and M.-L. Chang. 2018. “Socioemotional Wealth and Innovativeness in Small- and Medium-Sized Family Enterprises: A Configuration Approach.” Journal of Small Business Management 56 (Sup 1): 53–67.

- Gibbert, M., W. Ruigrok, and B. Wicki. 2008. “What Passes as a Rigorous Case Study?” Strategic Management Journal 29 (13): 1465–1474.

- Gilding, M., S. Gregory, and B. Cosson. 2015. “Motives and Outcomes in Family Business Succession Planning.” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 39 (2): 299–312.

- Gioia, D., K. Corley, and A. Hamilton. 2013. “Seeking Qualitative Rigor in Inductive Research: Notes on the Gioia Methodology.” Organizational Research Methods 16 (1): 15–31.

- Gómez-Mejía, L. R., C. Cruz, P. Berrone, and J. De Castro. 2011a. “The Bind That Ties: Socio-Emotional Wealth Preservation in Family Firms.” Academy of Management Annals 5 (1): 653–707.

- Gómez-Mejía, L. R., K. T. Haynes, M. Núñez-Nickel, K. J. Jacobson, and J. Moyano-Fuentes. 2007. “Socio-Emotional Wealth and Business Risks in Family-Controlled Firms: Evidence from Spanish Olive Oil Mills.” Administrative Science Quarterly 52 (1): 106–137.

- Gómez-Mejía, L. R., R. E. Hoskisson, M. Makri, D. G. Sirmon, and J. T. Campbell. 2011b. “Innovation and the Preservation of Socio-Emotional Wealth: The Paradox of R&D Investment in Family Controlled High Technology Firms.” Unpublished manuscript. Mays Business School, Texas A&M University.

- Gómez-Mejía, L. R., I. Neacsu, and G. Martin. 2019. “CEO Risk-Taking and Socioemotional Wealth: The Behavioral Agency Model, Family Control, and CEO Option Wealth.” Journal of Management 45 (4): 1713–1738.

- Graebner, M., and K. Eisenhardt. 2004. “The Seller’s Side of the Story: acquisition as Courtship and Governance as Syndicate in Entrepreneurial Firms.” Administrative Science Quarterly 49 (3): 336–403.

- Grundström, C., C. Öberg, and A. Ö. Rönnbäck. 2012. “Family-Owned Manufacturing SMEs and Innovativeness: A Comparison between within-Family Successions and External Takeovers.” Journal of Family Business Strategy 3 (3): 162–173.

- Gu, Q., J. W. Lu, and C. N. Chung. 2019. “Incentive or Disincentive? A Socioemotional Wealth Explanation of New Industry Entry in Family Business Groups.” Journal of Management 45 (2): 645–672.

- Gupta, V., N. Levenburg, L. Moore, J. Motwani, and T. V. Schwarz. 2010. “Family Business in Sub-Saharan Africa versus the Middle East.” Journal of African Business 11 (2): 146–162.

- Habbershon, T. 2006. “Commentary: A Framework for Managing the Familiness and Agency Advantage in Family Firms.” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 30 (6): 879–886.

- Hall, A., and M. Nordqvist. 2008. “Professional Management in Family Businesses: Toward and Extended Understanding.” Family Business Review 21 (1): 51–69.

- Hauck, J., and R. Prügl. 2015. “Innovation Activities during Intra-Family Leadership Succession in Family Firms: An Empirical Study from a Socio-Emotional Wealth Perspective.” Journal of Family Business Strategy 6 (2): 104–118.

- Herrera, L., and G. Sánchez-González. 2013. “Firm Size and Innovation Policy.” International Small Business Journal: Researching Entrepreneurship 31 (2): 137–155.

- Howorth, C., and E. Hamilton. 2012. “Family Businesses.” In Enterprise and Small Business, edited by S. Carter and D. Jones-Evans, 3rd ed., 232–251. Harlow, UK: Pearson Educational.

- Howorth, C., M. Rose, E. Hamilton, and P. Westhead. 2010. “Family Firm Diversity and Development: An Introduction.” International Small Business Journal: Researching Entrepreneurship 28 (5): 437–451.

- Hsu, L. C., and H. C. Chang. 2011. “The Role of Behavioural Strategic Controls in Family Firm Innovation.” Industry & Innovation 18 (7): 709–727.

- Hu, Q., and M. Hughes. 2020. “Radical Innovation in Family Firms: A Systematic Analysis and Research Agenda.” International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour & Research 26 (6): 199–1234.

- Jennings, J., T. Reay, and L. Steier. 2015. “Book Review: The Sage Handbook of Family Business (2014). London: Sage.” Academy of Management Learning & Education 14 (3): 430–436.

- Kach, A., C. Busse, A. Azadegan, and S. M. Wagner. 2016. “Manoeuvring through Hostile Environments: How Firms Leverage Product and Process Innovativeness.” Decision Sciences 47 (5): 907–956.

- Kellermanns, F. W., K. A. Eddleston, R. Sarathy, and F. Murphy. 2012. “Innovativeness in Family Firms: A Family Influence Perspective.” Small Business Economics 38 (1): 85–101.

- Krasnicka, T., and I. Steinerowska-Streb. 2019. “Family Involvement and Innovation in Family Enterprises.” Scientific Papers of Silesian University of Technology, Organization and Management Series No. 136. Katowice, Poland: Silesian University of Technology Publishing House.

- Kushnir, K. 2010. How Do Economies Define Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs)? Companion Note for the MSME Country Indicators 66. Washington DC: IFC World Bank.

- Lalonde, J. F. 2013. “Cultural Determinants of Arab Entrepreneurship: An Ethnographic Perspective.” Journal of Enterprising Communities: People and Places in the Global Economy 7 (3): 213–232.

- Le Breton–Miller, I., and D. Miller. 2013. “Socioemotional Wealth across the Family Firm Life Cycle: A Commentary on “Family Business Survival and the Role of Boards.” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 37 (6): 1391–1397.

- Leppäaho, T., E. Plakoyiannaki, and P. Dimitratos. 2016. “The Case Study in Family Business: An Analysis of Current Research Practices and Recommendations.” Family Business Review 29 (2): 159–173.

- Li, Z., and J. J. Daspit. 2016. “Understanding Family Firm Innovation Heterogeneity: A Typology of Family Governance and Socio-Emotional Wealth Intentions.” Journal of Family Business Management 6 (2): 103–121.

- Marshall, C., and G. B. Rossman. 2011. Designing Qualitative Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Martínez-Alonso, R., M. J. Martínez-Romero, J. Diéguez-Soto, and A. A. Rojo-Ramírez. 2020. “How Family Involvement in Management Affects the Innovative Behavior of Private Firms: The Moderating Role of Technological Collaboration with External Partners.” In Handbook of Research on the Strategic Management of Family Businesses, edited by L. Gnan, I. Barros-Contreras, and J.M. Palma-Ruiz, 128–152. Hershey, PA: IGI Global.

- Matroushi, H., F. Jabeen, and S. All. 2018. “Prioritising the Factors Promoting Innovation on Emirati Female-Owned SMEs: AHP Approach.” International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation Management 22 (3): 220–250.

- McKelvie, A., A. McKenny, G. Lumpkin, and J. Short. 2014. “Corporate Entrepreneurship in Family Businesses: Past Contributions and Future Opportunities.” Chapter 17 in the Sage Handbook of Family Business, edited by L. Melin, M. Nordqvist, and P. Sharma, 340–363. Hershey, PA, USA: IGI Global.

- Memili, E., and C. Dibrell, eds. 2019. The Palgrave Handbook of Heterogeneity Among Family Firms. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Miller, D., and I. Le Breton-Miller. 2014. “Deconstructing Socioemotional Wealth.” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 38 (4): 713–720.

- Miller, D., L. Steier, and I. Le Breton-Miller. 2003. “Lost in Time: Intergenerational Succession, Change, and Failure in Family Business.” Journal of Business Venturing 18 (4): 513–531.

- Miller, D., L. Steier, and I. Le Breton-Miller. 2016. “What Can Scholars Learn from Sound Family Businesses?” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 40 (3): 445–455.

- Miller, D., M. Wright, I. Le Breton-Miller, and L. Scholes. 2015. “Resources and Innovation in Family Businesses: The Janus-Face of Socio-Emotional Preferences.” California Management Review 58 (1): 20–40.

- Ministry of Economy 2017. “The impact of SMEs on the UAE's economy.” Retrieved October 25, 2018, from UAE Government website: https://www.government.ae/en/information-and-services/business/crowdfunding/the-impact-of-smes-on-the-uae-economy

- Morck, R., and B. Yeung. 2003. “Agency Problems in Large Family Business Groups.” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 27 (4): 367–382.

- Munari, F., R. Oriani, and M. Sobrero. 2010. “The Effects of Owner Identity and External Governance Systems on R&D Investments: A Study of Western European Firms.” Research Policy 39 (8): 1093–1104.

- Newbert, S., and J. Craig. 2017. “Moving beyond Socioemotional Wealth: Toward a Normative Theory of Decision Making in Family Business.” Family Business Review 30 (4): 339–346.

- Ng, P. Y., M. Dayan, and A. Di Benedetto. 2019. “Performance in Family Firm: Influences of Socioemotional Wealth and Managerial Capabilities.” Journal of Business Research 102: 178–190.

- OECD 2005. OECD SME and Entrepreneurship Outlook: 2005. Paris: OECD.

- Patton, M. Q. 2001. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Pearson, A., D. Holt, and J. Carr. 2014. “Scales in Family Business Studies.” Chapter 28 in the Sage Handbook of Family Business, edited by L. Melin, M. Nordqvist, and P. Sharma, 551–572. Hershey, PA, USA: IGI Global.

- PWC 2016. Family Business Survey. Retrieved 2017, from PWC Middle East Region: https://www.pwc.com/m1/en/publications/family-business-survey/middle-east-family-business-survey-2016.pdf

- Revilla, A. J., and Z. Fernandez. 2012. “The Relation between Firm Size and R&D Productivity in Different Technological Regimes.” Technovation 32 (11): 609–623.

- Rosenbusch, N., J. Brinckmann, and A. Bausch. 2011. “Is Innovation Always Beneficial? A Meta-Analysis of the Relationship between Innovation and Performance in SMEs.” Journal of Business Venturing 26 (4): 441–457.

- Schulze, W. S., M. H. Lubatkin, and R. N. Dino. 2003. “Exploring the Agency Consequences of Ownership Dispersion among the Directors of Private Family Firms.” Academy of Management Journal 46 (2): 179–194.

- Shefer, D., and A. Frenkel. 2005. “R&D, Firm Size and Innovation: An Empirical Analysis.” Technovation 25 (1): 25–32.

- Stewart, A., and M. A. Hitt. 2012. “Why Can’t a Family Business Be More like a Nonfamily Business? Modes of Professionalization in Family Firms.” Family Business Review 25 (1): 58–86.

- Swab, R. G., C. Sherlock, E. Markin, and C. Dibrell. 2020. “SEW” What Do We Know and Where Do We Go? A Review of Socioemotional Wealth and a Way Forward.” Family Business Review 33 (4): 424–445.

- The World Bank 2018. Doing Business 2018: Reforming to Create Jobs. Washington: World Bank.

- Tidd, J., and B. Thuriaux‐Alemán. 2016. “Innovation Management Practices: cross‐Sectorial Adoption, Variation, and Effectiveness.” R&D Management 46 (S3): 1024–1043.

- UAE National Innovation Strategy. 2015. Dubai: UAE Ministry of Cabinet Affairs. Last accessed January 15, 2018. https://government.ae/en/about-the-uae/strategies-initiatives-and-awards/federal-governments-strategies-and-plans/national-innovation-strategy

- Werner, A., C. Schröder, and S. Chlosta. 2018. “Driving Factors of Innovation in Family and Non-Family SMEs.” Small Business Economics 50 (1): 201–218.

- Woodfield, P. J., and K. Husted. 2019. “How Does Knowledge Sharing across Generations Impact Innovation?” International Journal of Innovation Management 23 (08): 1940004.

- Yin, R. K. 2014. Case Study Research: Design and Method (5th edition). Thousand Oaks. California: Sage.

- Zahra, S. A. 2011. “Doing Research in the (New) Middle East: Sailing with the Wind.” Academy of Management Perspectives 25 (4): 6–21.

- Zahra, S. A., R. Labaki, S. Gawad, and S. Sciascia. 2014. “Family Firms and Social Innovation: Cultivating Organizational Embeddedness.” Chapter 22 in the Sage Handbook of Family Business, edited by L. Melin, M. Nordqvist, and P. Sharma, 442–459. Hershey, PA, USA: IGI Global.

- Zellweger, T. M., R. S. Nason, and M. Nordqvist. 2012. “From Longevity of Firms to Transgenerational Entrepreneurship of Families: Introducing Family Entrepreneurial Orientation.” Family Business Review 25 (2): 136–155.

Appendix 1.

Interview guide

Company background:

Year founded? Number of employees? Industry?

Annual R&D and innovation budget?

What is something unique about this company compared to competitors?

Interviewee information:

Current position? Age? Education level?

Generation in the family involved in this business? Total time with this business? Prior employment experience?

What is one thing that makes you proud about this company?

Governance:

Who makes most of the company decisions? How many members are there in your family who works in the company? What positions do they hold?

What are the contributions of the family member/s in improving the company’s innovation? Do you have any expectation(s) regarding one or more family members continuing with the company in the future? Why?

Would you mind if it were someone outside the family to take-charge of the company in the future? Is the family a consideration factor in terms of decision-making at the company?

Innovation:

What was the company’s first innovation/product? During the last 3 years, how many new product or service was introduced in this company?

Please explain the new products/services briefly, especially how and why they were introduced.

Do you think that this company is more innovative than its direct competitors? Why?

How is product innovation process managed and organized in the company? What are the roles of employees, customers and external partners in your innovation projects?

Challenges to innovate:

Did the company any face any problem/issue when developing new product/service? If yes, what were the problems/issues?

How did the company overcome the problems/issues? In your opinion, what is the greatest challenge to innovate? Do you think innovation is critical for your company’s survival? If yes, why? If no, why not?

In your opinion, what is the most important factor for a company to become innovative?