ABSTRACT

There is general support among teachers for inclusion of children with special educational needs, but many lack the confidence and knowledge to support autistic pupils. This can have an adverse effect on their education. Previous studies have explored the attitudes of teachers towards inclusion, but less is known about the experiences of teachers from contrasting school settings regarding autistic pupils. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with twelve teachers from mainstream and special schools. Questions explored the school provision for autistic pupils, including strategies relating to their learning, friendships, bullying and general inclusion. Thematic analysis identified themes describing teachers’ challenges supporting autistic children, strategies they adopt to facilitate achievement and the influence of factors such as staff training/expertise, educational ideology, attitudes and the physical environment. Overall, it is argued that, besides the structural differences between mainstream and special schools, there remain a number of additional factors impacting teachers’ sense of self-efficacy. These are discussed in relation to recent research perspectives advocating an inclusive educational pedagogy.

Introduction

Autism is a neurodevelopmental condition characterised by restricted and repetitive behaviours/interests and impairments in social communication (American Psychiatric Association; DSM-5) affecting over 1% of people in the UK (Brugha et al. Citation2012). Twenty-nine percent of pupils with an Education, Health & Care Plan have Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) recorded as their primary need (Department for Education Citation2019). In line with educational policy in England, the majority of children with a diagnosis of an ASD (73%) are placed in mainstream settings (DfE, 2017). While this affords benefits such as the opportunity to learn and socialise with their peers (Humphrey and Symes Citation2013; Koegel et al. Citation2013), it also presents challenges relating to social-communication difficulties (Attwood Citation2000), victimisation (Humphrey and Symes Citation2011), anxiety and depression (Strang et al. Citation2012; Wood and Gadow Citation2010) and behavioural difficulties (Macintosh and Dissanayake Citation2006). Mainstream teachers are required to make ‘reasonable adjustments’ to enable children with special educational needs (SEN) and disabilities to learn and be included in school life, which can pose a challenge (Greenstein Citation2014). In addition to having specific knowledge of autism, teachers are also expected to implement effective and appropriate teaching approaches (Frederickson, Jones, and Lang Citation2010; Odom, Cox, and Brock Citation2013), make adjustments to the curriculum and provide suitable support and resources (Lindsay et al. Citation2014).

Teachers generally agree inclusion is important for reasons of social justice (Artiles and Harris-Murri Citation2008; Polat Citation2011), but many have little confidence in their capacity to support students with SEN, especially ASD (Frederickson, Jones, and Lang Citation2010; Lindsay et al. Citation2013) and secondary school subject teachers in particular are reported to have significantly lower self-efficacy – beliefs about their capabilities to successfully teach autistic pupils – than school senior managers or SEN co-ordinators (Humphrey and Symes Citation2011).

Little (Citation2017) found that while teachers supported the concept of inclusion, this wasn’t always implemented at an operational level. Furthermore, teachers’ responses often implied that the autistic students create the barrier to social inclusion themselves by not ‘fitting in’ and attitudes such as this may also influence the implementation of inclusive practice. For example, there is greater reluctance for the inclusion of students with more severe disabilities and behavioural difficulties (Avramidis and Norwich Citation2002; Mazurek and Winzer Citation2011). Disruptive behaviours are often the result of anxiety or frustration for autistic children, but lack of understanding can lead a teacher to assume they are unable to conform to school codes of conduct (Little Citation2017). Some argue therefore that what is required is a societal change in attitudes, beliefs and assumptions about disability, diversity and difference (Arduin, Citation2015) and consequent teaching pedagogies that respond to individual difference, without drawing attention to (and thus stigmatising) those with special needs or disabilities (Florian & Black-Hawkins, Citation2011). A successful school experience for autistic children requires active commitment by teachers to the facilitation of academic and social opportunities. Lack of knowledge, together with lack of support systems can have adverse effects on student’s participation at school (Avramidis, Bayliss, and Burden Citation2000; Eldar, Talmor, and Wolf-Zukerman Citation2010) and are obstacles to inclusion (Lindsay et al. Citation2013). It is clear that teachers in mainstream schools face great demands such as large class sizes and pressure to achieve ever increasing pupil outcomes for national tests, league tables and Ofsted inspections while also meeting needs of children with widely diverse backgrounds and abilities. While many schools are generally more aware of their responsibilities, studies indicate that self-efficacy relating to effective inclusion drops significantly between pre-service and the end of the first teaching year (Mintz et al. Citation2020) and more generally, that the goals of inclusion to make education more responsive to the needs of all students, remain unmet (Barnard et al., Citation2000; Batten et al., Citation2006; Humphrey Citation2008).

While previous studies have explored the attitudes of teachers towards inclusion, less is known about the experiences of teachers from contrasting school settings regarding autistic pupils, and in particular their self-efficacy in relation to teaching children on the autistic spectrum. Even though there are contrasts in expertise and resources between mainstream and special schools, a deeper exploration of teacher experiences from both setting types is needed to see if there are generic issues, e.g. at a cultural rather than a structural level, and how these may impact experiences of working with autistic children. In light of this, the present study aimed to use qualitative methods to explore the perspectives of teachers from both mainstream and specialist settings, regarding the main challenges they face and strategies they implement to facilitate the achievement of autistic pupils.

Methods

Design

A qualitative design was used with semi-structured interviews.

Participants

Participants were recruited from mainstream and special schools in Southeast England through purposive sampling by phoning/emailing schools and making contact with individuals who had shown willingness to take part through word-of-mouth. Inclusion criteria comprised teachers currently working with pupils on the autistic spectrum who would be willing to discuss their beliefs about the needs and experiences of autistic pupils and the policies and practices regarding autism in their schools.

Twelve teachers were interviewed: six from mainstream and six from special schools with broadly matched socioeconomic status (mainstream schools ranged from 5 to 25% eligibility for free school meals compared to the country average of 28% and special schools ranged from 19 to 29% eligibility compared to the country average for special schools of 50%). Mainstream schools are defined as those run by the local council that principally meet the needs of pupils who do not have SENs. These were mixed-sex schools except for one school (for boys), and ranged in size from 670 to 1970 pupils. Special schools are defined as those for which the main purpose is to provide education for pupils with SENs. Three were mixed-sex, two were for boys only and one school was for girls only. Special school sizes ranged from 70 to 470 pupils. Demographic information of the teachers is shown in . (All names are pseudonyms.)

Table 1. Description of Participants According to Socio-Demographics

Procedure

A semi-structured interview consisted of broad, open-ended questions and explored the general needs of autistic pupils in the school (e.g. ‘Can you tell me a bit about the needs of the autistic pupils at this school’), how they try to meet these needs (e.g. ‘Do the staff play a particular role in facilitating friendships?’) and for mainstream teachers, their thoughts about inclusion (e.g. ‘How well would you say inclusion is working in your school?’). All interviews took place in their respective schools. The semi-structured interview guide (available from the first author on request) supported using flexible strategies, such as probes when necessary (e.g. ‘Can you give me an example of that?’). With permission, the interviews were recorded and transcribed.

A favourable ethical opinion was received from the University Ethics Committee. The information sheet stated that participation was voluntary and that participants were able to withdraw from the study at any time without any explanation.

Data analysis

Thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke Citation2006) was used to identify patterns in the data and capture commonalities whilst at the same time enabling teachers to be located within different school contexts. The method was inductive: themes were strongly linked to the data, rather than being fitted to analytic preconceptions. Analytic stages involved familiarisation with the data by the first author through several detailed readings of interview transcripts, summaries of key points from each interview made and generation of initial thoughts and observations, followed by coding of the data. Coding was done by the first author to allow for continuity between interviewing, coding and analysis, across participants. Once regularities were identified in the data between participants, the codes were then sorted into potential themes and sub-themes in collaboration with the second author. This was followed by refinement of the selection of themes, and finally the analysis of themes and subthemes to ensure that they reflected coded extracts and consideration of how they fit into a broader context. Agreement was achieved between researchers as an iterative process.

Results

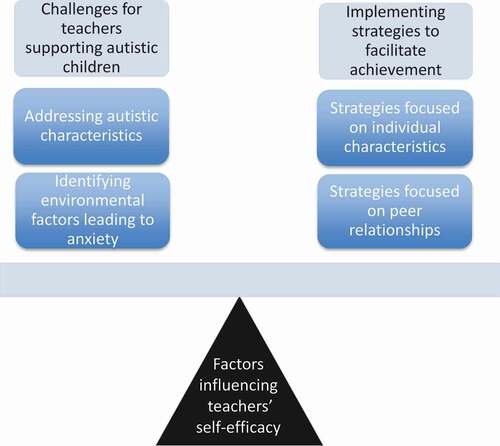

Teachers’ accounts reflected the following themes: i) challenges for teachers supporting autistic pupils; ii) implementing strategies to facilitate achievement and; iii) transcending theme: factors influencing self-efficacy related to meeting the needs of autistic pupils. These themes are discussed and illustrated with exemplar quotes. Overall, it is argued that there is a balance between the challenges for teachers and their ability to implement strategies and that this is influenced by a number of factors affecting their sense of self-efficacy. Unless stated, reference to pupils in the results denotes pupils on the autistic spectrum. represents the relationship between the themes and sub themes.

Theme 1: challenges for teachers supporting autistic children

Teachers described the challenges they faced supporting the needs of autistic children in their school. These either focused on addressing autistic characteristics or identifying environmental factors that may represent triggers for anxiety that can impact on aspects of pupils’ school experience.

Addressing autistic characteristics

There were many accounts of challenges addressing pupils’ autistic characteristics, relating to their social and learning needs. In particular, teachers described how they needed to help pupils to understand and recognise friendship. Richard relayed a conversation he had with a boy in Year 9 who believed someone couldn’t be a friend if they had different interests:

He says, “I don’t have anything in common with them … my interests are unique to theirs”. So from his perspective, even though pupils are very friendly and nice to him, they don’t have the same interests as him and therefore they’re not his friends. (Richard, Special school)

Teachers described frequently dealing with incidents where pupils felt they were being bullied or held resentments resulting from perceived acts of bullying. While some accounts reflected situations where autistic pupils had amplified incidents or attributed hostile intentions, other examples were given (particularly from mainstream schools) of incidents where pupils had been bullied. Beth described what happened after a group of neurotypical boys in Year 11 physically bullied an autistic boy in Year 10:

After that people came forward … and they brought in pictures taken in school, with this lad, and somebody had drawn, like, a [offensive image] on his back, of his shirt, in a lesson, taken a photograph of it, and posted it on Facebook. (Beth, Mainstream School)

Further challenges related to managing learning differences. They reported struggling to engage pupils due to their rigidity of thinking. For example, if they didn’t believe a particular subject was beneficial to them, or if it failed to relate to their special interest:

[He] just loves chemistry - loves blowing things up, loves experiments. And our focus at the moment is trying to teach him that chemistry is a bigger subject than just that, because he knows a hundred different chemicals … but he needs to understand that there are other areas of that subject to explore. (Nick, Special school)

Identifying environmental factors that lead to anxiety

Many accounts were provided of pupils’ anxiety and how this affected learning and general wellbeing. Alison shared a story about how she’d been affected by a girl in Year 9 who was struggling to cope in the school environment:

She said, “I know I’m different, I know I’m antisocial” and the tears began to roll down her face … and she said, “when I was at junior school I used to stamp my feet and scream at people … sometimes here, I want to stamp my feet and scream at people”, … I think at the minute what worries me about her is her anxiety’s high. (Alison, Mainstream School)

Teachers also described the challenge of identifying the causes of anxiety. Jill explained how pupils suppressed their natural responses, leading others to believe they are coping, when in fact they are holding it in throughout the day. One example of this was Lucy, a pupil in Year 11:

Lucy was talking about how at the end of the day she deconstructs all the sentences that she’s had. She analyses them and then she plans all of her interactions for the next day … it’s a bit like running a laptop with loads and loads of different programmes going on, … it takes her six hours to go to sleep because she is literally reliving her day. (Jill, Special school)

Challenges for teachers in supporting the needs of autistic children were therefore far reaching and were reported across both setting types, including understanding a range of individual difficulties and identifying factors influencing their levels of anxiety, which they perceived as impacting on the pupils’ school experience.

Theme 2: implementing strategies to facilitate achievement

Teachers reported a number of strategies to facilitate achievement for autistic pupils. Similar to Theme 1, these were categorised as strategies to address individual characteristics, and wider environmental strategies, i.e. those focusing on peer relationships.

Strategies focused on individual characteristics

A key practice employed by teachers to support autistic pupils, particularly in special schools, was the provision of a clear structure to the day, through appropriate use of timetables and visuals, managing transitions and alerting pupils of potential change in advance.

If it’s a trip, or if the teacher’s off sick and there’s a cover teacher in place, then we would ensure that the students know in advance what the changes are to the day. (James, Special school)

Similarly, a great deal of attention was given to the clear use of language in special schools.

We have a very heavy focus on language in terms of making sure instructions are given clearly, and in the order that you want the child to do things. So we don’t say “before you go out to break, hand your homework in”, because we know the chances are you’ll go out to break and then hand your homework in. (Catherine, Special school)

Monitoring levels of anxiety displayed by autistic pupils, and strategies for managing it, were also seen to greatly influence pupils’ daily experiences. Jill described a simple method of monitoring anxiety levels that works in her school:

We have things like stress thermometers in classrooms, which is a visual display … the girls come in in the morning and put their name as to where they’re kind of feeling emotionally and then if it’s obviously a red or an orange then we probably need to deal with that straight away, but that’s a great way of flagging to us, without having to have a conversation about it. (Jill, Special school)

Teachers gave examples of where they had provided social communication support for autistic pupils. In mainstream schools these usually occurred during lunch times, whereas in special schools social skills training was woven more extensively into the school day. Richard described the range of opportunities available to pupils in his school:

We’ve got group communication groups, social thinking groups, we’ve got groups where they’re sort of practising social skills … There’s something called ‘the girls’ group’, but it’s more of an informal one. (Richard, special school)

Strategies focused on peer relationships

Teachers also believed that the achievement of pupils was influenced by contact with their peers. Establishing friendships and enjoying shared interests had the potential to produce positive outcomes. Many teachers identified a tendency for autistic pupils to befriend other autistic pupils, often through mutual interests such as computer games. Teachers felt that this was key to successful friendships and allowed electronic devices during break-times as a means of enabling social interaction:

If one of them gets their phone out, they’ll all be flocked around. You know they’re not really having conversations, it’s the interest that has brought them together … they’re comfortable with those people being around them, because they know that they share those same interests. (Christine, Mainstream School)

Teachers would also find extra-curricular opportunities for pupils based around their interests, ranging from Minecraft, Wii and science-fiction to board games and football. Recognising that many pupils don’t tend to join the more competitive sports clubs, so were missing out on vital social sporting opportunities, Isobel’s school decided to open an additional-needs sports academy after school. They were careful to make it open to all to avoid segregation, but at the same time prevent it being dominated by those who are best at sport:

They go out and they play matches, and that’s brilliant because then they see that, it gives them a lot of self-esteem actually, because then they’ve represented the school as well. (Isobel, Mainstream School)

Teachers therefore implemented strategies to facilitate achievement for autistic pupils that focused on individual characteristics and peer relationships. These were apparent in both setting types, and revealed a wide range of ideas that schools could adopt to reduce barriers to learning and achievement.

Theme 3: transcending theme: factors influencing teachers’ self-efficacy to meet the needs of autistic pupils

Transcending themes 1 and 2 were the factors influencing teachers’ self-efficacy to meet the needs of autistic pupils. These factors can be seen to affect best practice, and in particular, the teachers’ perceived ability to implement strategies to facilitate achievement. The relationship between these themes is illustrated in above and will be explained with quotes from teachers with reference to differences between mainstream and specialist settings.

Factors reported to affect the balance between challenges and strategies included educational ideology, teacher attitudes, staff expertise/training, workload/pressures, physical environment and heterogeneity of ASD. Educational ideology was defined as the way in which schools support autistic pupils. For some mainstream schools, a one-size-fits-all approach was reported, e.g. adopting a number of general policies and strategies to support pupils with special educational needs, e.g. social skills group, time-out cards, quiet spaces and diversity week. Other schools, particularly special schools, tended to adopt a more individualised approach, getting to know individual pupils and taking action to meet their needs, managing transitions, monitoring mental health problems, grouping according to social needs and holding regular staff meetings to discuss different perspectives. Catherine described how, in addition to a general attentiveness of teachers to their difficulties, staff also dealt with each problem arising as a distinct case requiring an individual response:

We have a policy that if a child refuses to do something, you have to ask yourself all the different reasons it could be why he’s refusing to do that. Is it because he’s cross with you? Is it because he had an argument with his mum? Is it because he hasn’t understood? Is it because he can’t cope with that change? So all the time the teachers are trying to think, where is this coming from? (Catherine, Special school)

Teachers’ attitudes towards inclusion and neurodiversity also tended to influence self-efficacy. For example, Jill advocated providing young children with an understanding that everybody is different:

I think that there’s something around the de-stigmatisation of autistic kids and people … if we can just be more flexible in our approach and have better neurodiversity, then actually there’ll be less of a problem. If we start seeing the benefits of the way that autistic people think rather than focusing on the deficits that they find difficult, that’s the key to it, isn’t it? (Jill, Special school)

Staff expertise and training were also seen as key factors and varied widely between special and mainstream school settings. Inevitably, special schools tended to hire teachers who are experienced in SEN, trained all staff in autism and had access to speech and language therapists, occupational therapists and other therapies (usually, though not always on site). Therapy could sometimes be integrated into a holistic approach. For example, Janet described how their occupational therapist helps all children in the school with sensory and physical difficulties:

She is always willing to go the extra mile and to provide training, and anything else she can do - and will do things that will benefit the whole, because she knows that a lot of our boys have got sensory/physical difficulties as well. She came up, in consultation with one of us … with a fine and gross motor skills programme. And a lot of that takes part in our PE lessons. (Janet, Special school)

Conversely, teachers from some mainstream settings reported workload/other pressures interfering with additional training in autism. It was clear that all teachers had a genuine desire to support autistic pupils, but that in mainstream settings in particular, the reality was that other pressures and commitments could prevent some of the solutions from being implemented. Alison expressed this clearly in relation to training materials she distributes to school staff:

I think when I compare this school to other places I’ve worked, the school has a greater level of interest, and I think where teachers don’t read and don’t look at the information, it’s not that they’re not interested, it’s just that they have so much to do. They’re trying to get the next thing done. (Alison, Mainstream School)

Environmental factors were also considered to be important determinants of the balance between challenges and implementation of strategies. It was clear that many mainstream schools had made provision for a quiet space for pupils. But in special schools there were also a number of additional considerations, e.g. neutral classrooms to prevent sensory overload, arranging seating to encourage social interactions, visually supported learning and resources/adaptive equipment for fine motor skill development.

A big focus for us is the environment … so the classrooms are small; they have spaces where the students can work independently but spaces where they can work collaboratively as a group. … Display is minimised, but it’s kept very focused because we try to minimise the amount of visual stimulus in the room that could distract or upset the students. (Nick, Special school)

Finally, heterogeneity of autistic characteristics was considered by some teachers to be a barrier to self-efficacy. For example, one teacher felt that mainstream school settings are not always suitable for pupils with high levels of anxiety, particularly when their behaviour impacted on other pupils in the school:

For the students who experience anxiety - a high degree of anxiety - and then start to then display behaviours that impact on others, I think that that’s when we kind of, draw the line … I think the students whose anxiety exhibits itself in behaviour we struggle to include them. (Beth, Mainstream School)

In summary, whilst inclusive educational ideologies, sufficient staff expertise and training and conducive physical environments enabled the implementation of strategies to facilitate achievement, a one-size-fits-all approach, workload pressures and heterogeneity of ASD characteristics tended to affect their self-efficacy and hence their ability to meet the needs of autistic pupils.

Discussion

This study explored the perspectives of teachers from mainstream and special school settings, providing valuable insights into their experiences relating to the challenges supporting autistic children, the strategies they implement to facilitate achievement and the influence of certain factors on their sense of self-efficacy to meet pupils’ needs.

The first theme highlighted a number of challenges they face as teachers, including addressing a range of autistic characteristics, and identifying environmental factors that lead to anxiety. Results supported previous research indicating the need to support autistic pupils with their understanding of the concept of friendship. For example, Calder, Hill, and Pellicano (Citation2013) reported that some children were confused about whether certain peers were friends or not and described feeling lonely and left out of social groups. Other studies highlight the importance of teaching friendship skills and providing opportunities for pupils to practice these skills (Strain and Bovey Citation2011). The findings also support literature indicating higher levels of bullying of children on the autistic spectrum (Chatzitheochari, Parson & Platt, Citation2014; Symes and Humphrey Citation2010) and the greater risk in mainstream school settings (All Party Parliamentary Group on Autism Citation2017; Cook, Ogden, and Winstone Citation2016). In addition to addressing social needs, teachers talked about the challenge of identifying specific learning needs of pupils, such as rigidity of thinking preventing pupils from moving beyond their own special interests. Studies indicate that special interests used in the curriculum allow pupils to engage and to manage their anxiety (Mintz Citation2008). However, teachers in the present study felt that overemphasis on them could lead to missed opportunities to challenge pupils to learn and communicate in wider contexts.

Another significant challenge identified was the need to recognise triggers for anxiety. Anxiety is common for autistic people (Bellini Citation2006; Kim et al. Citation2000) and research indicates that the triggers can be different compared to the neurotypical population, for example, difficulties predicting others’ behaviour and unanticipated changes in the environment (Gillott, Furniss, and Walter Citation2001). These can lead to frustration, agitation and panic attacks and so impede their ability to cope day-to-day (Gillott and Standen Citation2007). In order to provide solutions that promote adaptive behaviours, accurate identification of the triggers is therefore essential (Bellini Citation2006). Whilst addressing autistic characteristics is important for facilitating achievement, this recognition of the triggers of anxiety represents a greater understanding of the barriers faced by autistic children in school and the importance of understanding how schools can adjust the environment to reduce these barriers.

Theme 2 reflected a number of strategies teachers implemented to facilitate achievement, addressing various learning, social and mental health needs. First, a number of strategies focused on individual characteristics were reported such as providing a clear structure to the day, managing transitions and clear use of language. These strategies are in line with suggestions in the literature regarding successful approaches to helping autistic pupils (Connor Citation1999; Hodgdon Citation2003; Leach and Duffy Citation2009), for example priming (ensuring a child is comfortable with a task before it is set) and visual cues to aid working memory.

Strategies used to monitor levels of anxiety (e.g. stress thermometers and calm boxes) were considered crucial by some teachers. Survey results of an inquiry by the All Party Parliamentary Group on Autism indicated that pupils are often punished for what is seen as ‘poor behaviour’ when in fact the behaviour is a direct result of anxiety, and that focusing on the behaviour rather than the cause of the anxiety is setting the pupil up to fail (NAS, Citation2017). Strategies for correctly identifying and addressing anxiety-related behaviour are therefore essential.

Congruent with the understanding of how schools can help to reduce barriers discussed in Theme 1, Theme 2 also identified a number of strategies designed to facilitate positive social contact with peers, e.g. through extra-curricular opportunities. Differences autistic pupils have reading social situations may impact negatively on their ability to form friendships (Locke et al. Citation2013). Interventions to support their active social engagement with others are therefore vital (Stitchter et al. Citation2012). Many teachers referred to interventions that were specifically focused on development of social skills. While it is important to provide interventions supporting social engagement with others (Lindsay et al. Citation2014) a meta-analysis of 55 single subject design studies suggested that school-based (child-focused) social skills interventions are minimally effective for autistic children (Bellini et al. Citation2007). Suggested reasons for this were the de-contextualised settings and low generalisability to other settings and peers. Instead interventions should be implemented in environments where social interactions can occur naturally with access to neurotypical peers (Koegel, Robinson, and Koegel Citation2009). The strategies described in this study, encouraging contact with peers and forming clubs focusing on common interests are strategies known to successfully influence social participation (Koegel, Robinson, and Koegel Citation2009; Koegel et al. Citation2013).

The findings revealed a transcending theme describing various factors influencing teachers’ self-efficacy related to meeting the needs of autistic pupils. This theme illustrated potential differences in experiences, thoughts and beliefs between mainstream and special school teachers. Whilst factors such as staff training/expertise and resources are understandably more evident in specialist settings, other factors such as educational ideology, teacher attitudes, and attention to the physical environment varied widely. There was a tendency in mainstream settings to adopt generic approaches such as time-out cards, quiet spaces and diversity week. These were helpful, but previous studies have stressed the importance for schools to know their students as individuals with unique needs rather than drawing assumptions about the level and type of support required (Hebron Citation2017). While teachers in mainstream settings expressed a general desire to ensure the successful inclusion of autistic pupils, sometimes other commitments prevented strategies being implemented. In line with previous research (Ruble, Usher, and McGrew Citation2011) there was a definite sense that the variability of pupils’ autistic characteristics led to perceptions of the challenges being too great to meet their needs. Indeed in some instances, their reduced self-efficacy to meet these needs was attributed to these ‘deficits’, as previously noted by Little (Citation2017) rather than to the barriers manifest in the external factors such as the school environment, outlined in previous studies (Billington Citation2006; Hebron Citation2017). This is detrimental for autistic pupils and can result in exclusion when individual needs are not being met (Little Citation2017). Every child should be equally valued within the school culture (Dybvik Citation2004) and be enabled access and active participation, whatever their needs (Humphrey Citation2008; Swain, Nordness, and Leader-Janssen Citation2012). Some teachers in this study provided excellent examples of school communities that were committed to supporting inclusive practice. However, where challenges were perceived to be too great, their sense of efficacy towards implementing strategies to meet the various challenges was undermined.

There are limitations of the present study. Geographically, participants were from Southeast England so might reflect some bias in terms of the social economic status and ethnic origins of pupils in the schools. In addition, the teachers interviewed were members of senior management or special educational needs coordinators who arguably possessed higher levels of knowledge/expertise and therefore may not represent the full range of thoughts and beliefs of regular teachers who don’t hold these roles.

Implications

Since the prevailing emphasis in the UK is biased towards inclusion and personal choice regarding school placement it is important that all staff have a clear understanding of what constitutes inclusion within their school (Eldar, Talmor, and Wolf-Zukerman Citation2010), and sufficient resources are provided to cater for the needs of all, including specific information and training on how best to implement these resources (Lauchlan and Greig Citation2015). These findings have implications for the development of inclusive strategies. It is clear that teachers face many challenges supporting autistic children, and that in mainstream school settings this can be particularly demanding when combined with pressures to meet the needs of large classes of pupils with a diverse set of individual differences. Nevertheless, many of the strategies employed could be implemented more widely with minimal impact on resources or expertise (e.g. appropriate use of timetables and visuals, managing transitions, anxiety thermometers and clubs based on special interests). There is however substantial scope for increased training of school staff concerning the academic and social needs of autistic pupils if the challenges are to become more manageable, effective strategies implemented and teachers’ self-efficacy increased.

Disclosure statement

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Anna Cook

Anna Cook is a Teaching Fellow in Developmental Psychology. Her work focuses on autism, inclusion and bullying and she has published papers on the school experiences of autistic adolescents, and the impact of contact with autistic pupils on the attitudes of typically developing peers.

Jane Ogden

Jane Ogden is a Professor of Health Psychology. Jane has published over 200 refereed papers and 8 books. Much of her research has involved the evaluation of a range of different interventions across settings including schools, hospitals and the community and has focused on both adults and children.

References

- All Party Parliamentary Group on Autism. 2017. Autism and Education in England 2017. London: National Autistic Society.

- American Psychiatric Association. 2013. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC.

- Arduin, S. (2015). A review of the values that underpin the structure of an education system and its approach to disability and inclusion. Oxford Review of Education, 41, 105–121

- Artiles, A. J., and N. Harris-Murri, Rostenberg. 2008. Inclusion as Social Justice: Critical Notes on Discourses, Assumptions and the Road Ahead. Theory into Practice 45 (3): 260–268. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15430421tip4503_8.

- All Party Parliamentary Group on Autism and The National Autistic Society 2017. Autism and education in England 2017 Retrieved from: https://www.autism-alliance.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/APPGA-autism-and-education-report.pdf.

- Attwood, T. 2000. “Strategies for Improving the Social Integration of Children with Asperger Syndrome.” Autism 4 (1): 85–100. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361300004001006.

- Avramidis, E., and B. Norwich. 2002. “Teachers’ Attitudes Towards Integration/inclusion: A Review of the Literature.” European Journal of Special Needs Education 17 (2): 129–147. https://doi.org/10.1080/08856250210129056.

- Avramidis, E., P. Bayliss, and R. Burden. 2000. “A Survey into Mainstream Teachers’ Attitudes Towards the Inclusion of Children with Special Educational Needs in the Ordinary School in One Local Education Authority.” Educational Psychology 20 (2): 191–211. https://doi.org/10.1080/713663717.

- Barnard, J., Prior, A., & Potter, D. (2000). Inclusion and autism: Is it working. London: National Autistic Society

- Batten, A., Corbett, C., Rosenblatt, M., Withers, L., & Yuille, R. (2006). Autism and education: the reality for families today. London: The National Autistic Society

- Bellini, S. 2006. “The Development of Social Anxiety in Adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorders.” Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities 21 (3): 138–145. https://doi.org/10.1177/10883576060210030201.

- Bellini, S., J. K. Peters, L. Benner, and A. Hopf. 2007. “A Meta-analysis of School-based Social Skills Interventions for Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders.” Remedial and Special Education 28 (3): 153–162. https://doi.org/10.1177/07419325070280030401.

- Billington, T. 2006. “Working with Autistic Children and Young People: Sense, Experience and the Challenges for Services, Policies and Practices.” Disability & Society 21 (1): 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687590500373627.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Brugha, T., S. A. Cooper, S. McManus, S. Purdon, J. Smith, F. J. Scott, … F. Tyrer. 2012. Estimating the Prevalence of Autism Spectrum Conditions in Adults: Extending the 2007 Adult Psychiatric. http://www.wecommunities.org/MyNurChat/archive/LDdownloads/Est_Prev_Autism_Spec_Cond_in_Adults_Report.pdf

- Calder, L., V. Hill, and E. Pellicano. 2013. “‘Sometimes I Want to Play by Myself’: Understanding What Friendship Means to Children with Autism in Mainstream Primary Schools.” Autism 17 (3): 296–316. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361312467866.

- Chatzitheochari, S., S. Parson, and L. Platt. 2014. Bullying Experiences among Disabled Children and Young People in England: Evidence from Two Longitudinal Studies. Department of Quantitative Social Science Working Paper, 11–14.

- Connor, M. 1999. “Children on the Autistic Spectrum: Guidelines for Mainstream Practice.” Support for Learning 14 (2): 80–86. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9604.00107.

- Cook, A., J. Ogden, and N. Winstone. 2016. “The Experiences of Learning, Friendships and Bullying of Boys with Autism in Mainstream and Special School Settings: A Qualitative Study.” British Journal of Special Education 43 (3): 250–271. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8578.12143.

- Department for Education. 2019. Special Educational Needs in England. Available at: January 2019. https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/special-educational-needs-in-england-january-2019

- Dybvik, A. 2004. “Autism and the Inclusion Mandate.” Education Next 4: 42–49.

- Eldar, E., R. Talmor, and T. Wolf-Zukerman. 2010. “Successes and Difficulties in the Individual Inclusion of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) in the Eyes of Their Coordinators.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 14 (1): 97–114. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603110802504150.

- Florian, L., & Black-Hawkins, K. (2011). Exploring inclusive pedagogy. British Educational Research Journal, 37, 813–828

- Frederickson, N., A. P. Jones, and J. Lang. 2010. “Inclusive Provision Options for Pupils on the Autistic Spectrum.” Journal of Research in Special Education Needs 10 (2): 63–73. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-3802.2010.01145.x.

- Gillott, A., F. Furniss, and A. Walter. 2001. “Anxiety in High-functioning Children with Autism.” Autism 5 (3): 277–286. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361301005003005.

- Gillott, A., and P. J. Standen. 2007. “Levels of Anxiety and Sources of Stress in Adults with Autism.” Journal of Intellectual Disabilities 11 (4): 359–370. https://doi.org/10.1177/1744629507083585.

- Greenstein, A. 2014. “Is This Inclusion? Lessons from a Very Special Unit. International.” Journal of Inclusive Education 18 (4): 379–391. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2013.777130.

- Hebron, J. 2017. “The Transition from Primary to Secondary School for Students with Autism Spectrum Conditions.” In Supporting Social Inclusion for Students with Autism Spectrum Disorders, edited by C. Little, 84–99. London: Routledge.

- Hodgdon, L. 2003. Visual Strategies for Improving Communication. Troy, MI: Quirk Roberts Publishing.

- Humphrey, N. 2008. “Including Pupils with Autistic Spectrum Disorder in Mainstream Schools.” Support for Learning 23 (1): 41–47. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9604.2007.00367.x.

- Humphrey, N., and W. Symes. 2011. “Peer Interaction Patterns among Adolescents with Autistic Spectrum Disorders (Asds) in Mainstream School Settings.” Autism 15 (4): 397–419. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361310387804.

- Humphrey, N., and W. Symes. 2013. “Inclusive Education for Pupils with Autistic Spectrum Disorders in Secondary Mainstream Schools: Teacher Attitudes, Experience and Knowledge.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 17 (1): 32–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2011.580462.

- Kim, J. A., P. Szatmari, S. E. Bryson, D. L. Streiner, and F. J. Wilson. 2000. “The Prevalence of Anxiety and Mood Problems among Children with Autism and Asperger Syndrome.” Autism 4 (2): 117–132. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361300004002002.

- Koegel, L. K., S. E. Robinson, and R. L. Koegel. 2009. “Empirically Supported Intervention Practices for Autism Spectrum Disorders in Schools and Community Settings: Issues and Practices.” Issues in Clinical Child Psychology 2: 149–176.

- Koegel, R. L., S. Kim, L. K. Koegel, and B. Schwartzman. 2013. “Improving Socialization for High School Students with ASD by Using Their Preferred Interests.” Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 43 (9): 2121–2134. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-013-1765-3.

- Lauchlan, F., and S. Greig. 2015. “Educational Inclusion in England: Origins, Perspectives and Current Directions.” Support for Learning 30 (1): 69–82. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9604.12075.

- Leach, D., and M. L. Duffy. 2009. “Supporting Students with Autism Spectrum Disorders in Inclusive Settings.” Intervention in School and Clinic 45 (1): 31–37. https://doi.org/10.1177/1053451209338395.

- Lindsay, S., M. Proulx, H. Scott, and N. Thomson. 2014. “Exploring Teachers’ Strategies for Including Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder in Mainstream Classrooms.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 18 (2): 101–122. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2012.758320.

- Lindsay, S., M. Proulx, N. Thomson, and H. Scott. 2013. “Educators’ Challenges of Including Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder in Mainstream Classrooms.” International Journal of Disability, Development and Education 60 (4): 347–362. https://doi.org/10.1080/1034912X.2013.846470.

- Little, C., Ed. 2017. Supporting Social Inclusion for Students with Autism Spectrum Disorders. London: Routledge.

- Locke, J., C. Kasari, E. Rotheram-Fuller, M. Kretzmann, and J. Jacobs. 2013. “Social Network Changes over the School Year among Elementary School-aged Children with and without an Autism Spectrum Disorder.” School Mental Health 5 (1): 38–47. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-012-9092-y.

- Macintosh, K., and C. Dissanayake. 2006. “Social Skills and Problem Behaviours in School-aged Children with High-functioning Autism and Asperger’s Disorder.” Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 36 (8): 1065–1076. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-006-0139-5.

- Mazurek, K., and M. Winzer. 2011. “Teacher Attitudes toward Inclusive Schooling: Themes from the International Literature.” Education and Society 29 (1): 5–25. https://doi.org/10.7459/es/29.1.02.

- Mintz, J. 2008. “Working with Children with Asperger’s Syndrome in the Mainstream Classroom: A Psychodynamic Take from the Chalk Face.” Psychodynamic Practice 14 (2): 169–180. https://doi.org/10.1080/14753630801961743.

- Mintz, J., P. Hick, Y. Solomon, A. Matziari, F. Ó’Murchú, K. Hall, … D. Margariti. 2020. “The Reality of Reality Shock for Inclusion: How Does Teacher Attitude, Perceived Knowledge and Self-efficacy in Relation to Effective Inclusion in the Classroom Change from the Pre-service to Novice Teacher Year?” Teaching and Teacher Education 91: 103042. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2020.103042.

- Odom, S. L., A. W. Cox, and M. E. Brock. 2013. “Implementation Science, Professional Development, and Autism Spectrum Disorders.” Exceptional Children 79 (3): 233–251. https://doi.org/10.1177/001440291307900207.

- Polat, F. 2011. “Inclusion in Education: A Step Towards Social Justice.” International Journal of Educational Development 31 (1): 50–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2010.06.009.

- Ruble, L. A., E. L. Usher, and H. H. McGrew. 2011. “Preliminary Investigation of the Sources of Self-Efficacy among Teachers of Students with Autism.” Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities 26 (2): 67–74. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088357610397345.

- Stitchter, J. P., K. V. O’Connor, M. J. Herzog, K. Lierheimer, and S. D. McGhee. 2012. “Social Competence Intervention for Elementary Students with Aspergers Syndrome and High Functioning Autism.” Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 42 (3): 354–366. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-011-1249-2.

- Strain, P. S., and E. H. Bovey. 2011. “Randomized, Controlled Trial of the LEAP Model of Early Intervention for Young Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders.” Topics in Early Childhood Special Education 31 (3): 133–154. https://doi.org/10.1177/0271121411408740.

- Strang, J. F., L. Kenworthy, P. Daniolos, L. Case, M. C. Wills, A. Martin, and G. L. Wallace. 2012. “Depression and Anxiety Symptoms in Children and Adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorders without Intellectual Disability.” Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders 6 (1): 406–412. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2011.06.015.

- Swain, K. D., P. D. Nordness, and E. M. Leader-Janssen. 2012. “Changes in Preservice Teacher Attitudes toward Inclusion.” Preventing School Failure 56 (2): 75–81. https://doi.org/10.1080/1045988X.2011.565386.

- Symes, W., and N. Humphrey. 2010. “Peer-group Indicators of Social Inclusion among Pupils with Autistic Spectrum Disorders (ASD) in Mainstream Secondary Schools: A Comparative Study.” School of Psychology International 31 (5): 478–494. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034310382496.

- Wood, J. J., and K. D. Gadow. 2010. “Exploring the Nature and Function of Anxiety in Youth with Autism Spectrum Disorders.” Clinical Psychology Science and Practice 17 (4): 281–292. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2850.2010.01220.x.