Abstract

Objective: The association between violence exposure and health risk behaviours in South African adolescents, and the moderating role of emotion dysregulation were investigated. Design: A multi-ethnic sample of adolescents (N = 925: boy: 47.3%, girl: 52.7%, M age = 16 years, SD = 1.54) completed a survey. Main outcome measures: Violence exposure across different contexts (home-, school-, community-, political victimisation), emotion dysregulation (inability to regulate sadness and anger) and a composite measure of health risk behaviours (smoking, substance use, risky sexual behaviour) were examined. Results: Boys reported more risk behaviours than girls, t (844) = 5.25, p < 0.001. Direct community victimisation was a predictor for boys’ risk behaviours, B = 0.22, p < 0.001. Indirect school victimisation and direct community victimisation were predictors for girls’ risk behaviours, B’s = 0.19, p’s < 0.01. Girls reported higher emotion dysregulation than boys, t (748) = −2.95, p < 0.01. Only for girls, emotion dysregulation moderated the associations of indirect home victimisation, B = 16, p < 0.01, and direct community victimisation, B = 15, p < 0.05, with risk behaviours. Conclusion: Interventions may target emotion regulation skills, particularly for girls, to enhance resilience to the negative effects of violence on behaviours.

Introduction

South Africa is disproportionately affected by violence. Although the political violence of Apartheid1 has subsided by 1994, interpersonal violence is still prominent among the general public. On average, 52 murders, 109 rapes and 470 physical assaults are reported daily (South African Police Service, Citation2016) and the mortality resulting from interpersonal violence is over seven times the global rate (Norman, Matzopoulos, Groenewald, & Bradshaw, Citation2007). Due to the country’s high prevalence of violence, both indirect (i.e. witnessing or hearing) and direct violence victimisation (i.e. personal experience) are common among South African adolescents (Shields, Nadasen, & Pierce, Citation2009). In particular, South African adolescents are exposed to violence across major developmental domains in their lives, including home- (e.g. physical violence between parents), school- (e.g. bullying among learners) and community violence (e.g. robbery or assault) (Kaminer, du Plessis, Hardy, & Benjamin, Citation2013). For example, in a representative sample in the Western Cape Province of South Africa, almost all adolescents (90%) had witnessed community violence, 40% had been a direct victim of community violence, 77% had witnessed home violence, 59% had been a direct victim of home violence and 76% reported either direct or indirect exposure to school violence (Kaminer et al., Citation2013). Given the unique historic context in South Africa, the younger generations may have also heard stories of the brutality and discrimination that happened during Apartheid, against their relatives or people they know (Sui et al., Citation2018).

Exposure to violence has been associated with a range of adverse psychological and behavioural outcomes in adolescents, including anxiety, depression, trauma symptoms, aggression and substance use (Bach & Louw, Citation2010; Finkelhor, Ormrod, & Turner, Citation2007; Mrug, Loosier, & Windle, Citation2008; Sui et al., Citation2018). It is crucial to examine the effects of violence on adolescents to inform interventions, as maladjustments during this developmental period can have a significant impact on their education and economic outcomes, psychosocial functioning and health in adulthood (Botticello, Citation2009; Das-Munshi et al., Citation2016).

Violence exposure and health risk behaviours

Typically, adolescents are sensation and novelty seeking, and have a propensity for risk behaviours (Steinberg, Citation2007). Very often, these behaviours can affect health and contribute to the leading causes of mortality and morbidity among adolescents, i.e. health risk behaviours (El Achhab et al., Citation2016). Examples of health risk behaviours include (but are not limited to) alcohol or drug intoxication, smoking and risky sexual behaviours, which place adolescents at risk for a range of chronic and infectious diseases (Reddy et al., Citation2013). Health risk behaviours during adolescence can be particularly problematic because they are associated with adverse short and long-term psychosocial consequences, including early pregnancy, risk for HIV/AIDS, as well as alcohol dependency or abuse, and criminal behaviours in adulthood (Brown et al., Citation2012; Hessler & Katz, Citation2010). Moreover, health risk behaviours tend to cluster and the majority of adolescents engage in multiple of these behaviours (e.g. both alcohol and drug use; Bobrowski, Czabala, & Brykczynska, Citation2007; Coleman, Wileyto, Lenhart, & Patterson, Citation2014; MacArthur et al., Citation2012).

Violence exposure across different contexts can foster health risk behaviours in adolescents. For example, witnessing community and home violence, and being a direct victim of community violence are significantly and positively related to alcohol and drug use (Begle et al., Citation2011; Lee, Citation2012; Moreira et al., Citation2008). Being a victim of community violence is associated with increased risky sexual behaviours, such as having multiple sexual partners, a high frequency of sexual activity and having sex without condoms (Albus, Weist, & Perez-Smith, Citation2004; Voisin, Jenkins, & Takahashi, Citation2011). Exposure to political violence, or violence motivated by political reasons, is linked to alcohol, cannabis and ecstasy use (Schiff et al., Citation2012). The associations between violence exposure and different types of health risk behaviours have also been documented in several South African studies (Brook, Morojele, Pahl, & Brook, Citation2006; Brook, Rubenstone, Zhang, Morojele, & Brook, Citation2011; Morojele & Brook, Citation2006), emphasising that violence is one of the major environmental stressors that can adversely influence adolescent health-related behaviours.

Violence and emotion dysregulation

Studies have consistently shown that exposure to violence, such as living in a violent community (Sharkey, Tirado-Strayer, Papachristos, & Raver, Citation2012), and being a victim of community violence (Kelly, Schwartz, Gorman, & Nakamoto, Citation2008) or childhood maltreatment (Kim & Cicchetti, Citation2010) are associated with diminished emotion regulation capacities in youth, or emotion dysregulation. Emotion dysregulation is defined as the impaired ability to regulate and tolerate negative emotional states (Dvir, Ford, Hill, & Frazier, Citation2014). Encounters with violence are inherently stressful and may produce heightened emotional arousal (Mrug & Windle, 2010); typically, emotions of sadness and anger (Kliewer et al., Citation2004, Citation2017). An adolescent's perceived capacity to control emotional arousal and to adaptively cope with sadness and anger reflects an important aspect of emotion regulation during this developmental period (Zeman, Shipman, & Suveg, Citation2002).

Emotion dysregulation and health risk behaviours

Researchers suggest that emotion regulation capacity is a key factor to overcome the adversities that put young people at risk for maladjustments (Masten & Coatsworth, Citation1998; Smokowski, Mann, Reynolds, & Fraser, 2004). However, many adolescents may not be adequately equipped to regulate their emotions, since the structures involved in emotion regulation are among the last to mature in the developing brain (Bell & McBride, Citation2010). Furthermore, adolescence is a period of transition characterised by significant increases in emotional reactivity and greater sensitivity to stressors (Casey et al., Citation2010). As such, negative affect is likely to emerge frequently during this period and adolescents are vulnerable to emotion dysregulation (McLaughlin, Hatzenbuehler, & Hilt, Citation2009). Emotion dysregulation is predictive of the onset of a variety of health risk behaviours in youth, including risky sexual behaviours, cigarette smoking and alcohol and drug use (Bell & McBride, Citation2010; Brown et al., Citation2012; Hessler & Katz, Citation2010; Wills, Walker, Mendoza, & Ainette, Citation2006; Wills, Simons, Sussman, & Knight, Citation2016).

Emotion dysregulation as a moderator

It is worth noting that not all young people exposed to violence develop behavioural problems (Moffitt et al., Citation2013). Prior research has indicated that violence exposure and emotion dysregulation are each associated with an increased likelihood of health risk behaviours among adolescents (Voisin et al., Citation2011; Wills et al., Citation2016). According to the diathesis-stress model (Spielman, Caruso, & Glovinsky, Citation1987), negative health outcomes are a result of the interaction between an individual’s predispositional vulnerability and an environmental stressor. This suggests variations in the strength of the relationship between violence exposure and one’s behaviour, and that some adolescents may be more likely to develop health risk behaviours if a certain predisposed vulnerability (e.g. psychological problem) is present in addition to the external stressor, i.e. violence exposure. Hence, emotion dysregulation may be a vulnerability factor that aggravates the negative effects of violence, placing adolescents at risk for engaging in health risk behaviours.

Studies have demonstrated the negative influence of emotion dysregulation on youth development. Emotion dysregulation, particularly difficulty in managing sadness and anger, is associated with behavioural problems such as peer‐rated physical and relational aggression (Zeman, Shipman, & Penza-Clyve, 2001; Zeman et al., Citation2002). Emotion dysregulation has also been found to diminish the effectiveness of children’s coping responses to peer victimisation (Cooley, Citation2019). Furthermore, Kliewer et al. (Citation2017) found that emotion dysregulation can exacerbate the effects of cumulative psychosocial risks (e.g. maternal mental health problems, family stress and violence exposure) on youth internalising and externalising problems. Although empirical associations between violence, emotion dysregulation and health risk behaviours have been found in the literature, researchers have not yet extended this work to the moderating role of emotion dysregulation in the relationship between violence exposure across different contexts and health risk behaviours in adolescents. Since adolescence presents a time of thrill seeking as well as important changes in affective experience and regulation, research on the moderating role of emotion dysregulation on health risk behaviours in South African adolescents exposed to violence may be particularly relevant for youth intervention development.

The role of gender

Research has suggested a pattern of gender difference in health risk behaviours in adolescents exposed to violence, such that boys are more likely than girls to use alcohol and drugs when exposed to direct and indirect community victimisation and physical assault (Begle et al., Citation2011; Moreira et al., Citation2008). Gender differences have also been noted in the developmental outcomes during adolescence in general, such that boys are more likely than girls to smoke cigarettes, use drugs, drink alcohol and engage in risky sexual behaviours (Croisant, Haque Laz, Rahman, & Berenson, 2013; Mennis & Mason, 2012; Slone & Mayer, Citation2015), whereas girls are more prone to internalising symptoms such as anxiety, depression (Mrug et al., Citation2008; Slone & Mayer, Citation2015), perceived stress in life and suicide ideation (Sui et al., Citation2018). Girls also have greater difficulties regulating negative emotions than their male counterparts (Bender, Reinholdt-Dunne, Esbjorn, & Pons, Citation2012). Given these differences between boys and girls, we focus on the role of gender in the present study as well.

The present study

There is an increasing evidence that indirect and direct violence exposures are associated with health risk behaviours in adolescents. However, there is no research yet that has simultaneously examined the differential effects of violence across multiple contexts (home-, school-, community- and political victimisation due to Apartheid) on health risk behaviours (smoking, alcohol use, soft drug use, hard drug use and risky sexual behaviour) in South African adolescents, the moderating role of emotion dysregulation in these associations and the role of gender. In this research, we examine these associations in a representative sample of South African adolescents in the Western Cape Province. The results of the study may inform the development of behavioural interventions to reduce health risk behaviours in this vulnerable population of adolescents exposed to violence in South Africa.

Method

Participants

Participants were drawn from the national sample of adolescents that completed the third South African Youth Risk Behaviour Survey (YRBS; Reddy et al., Citation2013). A two-stage cluster sampling procedure was used to recruit participants (see also Kann et al., Citation2016). The current study comprised of a random sample of adolescents in public secondary schools in the Western Cape Province of South Africa. The original sample consisted of 1300 adolescents from Grade 8 to 11 (boy: 45.9%; girl: 54.1%). Since the focus of our study is on health risk behaviours as an outcome of violence exposure, thus, for the analyses, we selected the majority of the adolescents (71.2%) who reported at least one health risk behaviour, making the final sample to be 925 adolescents (boy: 47.3%; girl: 52.7%). Their ages range from 13 to 22 years (M = 16 years for both boys and girls, SD = 1.58 and 1.49, respectively).

Procedure

Participants completed the third South African YRBS (Reddy et al., Citation2013) that examined the national prevalence of adolescent risk behaviours related to infectious disease (e.g. sexual activity), chronic disease (e.g. physical activity), injury and trauma (e.g. traffic safety), and mental health (e.g. substance use). For the purpose of this study, the data on substance use and sexual activity—specifically, smoking, alcohol use, soft drug use, hard drug use and risky sexual behaviour—of adolescents in the Western Cape Province of South Africa were analysed. In addition to the questions of the YRBS, these participants responded to another set of items related to violence exposure across different contexts, namely, home-based, school-based, community-based victimisation and political victimisation of Apartheid. For those who were under the age of 18 years, parental consents were required along with the assent forms. The participants were told to bring their signed assent and consent forms to school the next day and the ones who agreed to participate were invited to complete the questionnaire in the classrooms.

Measures

Indirect home and school victimisation

Indirect exposure to home and school violence was measured by two items adapted from the Survey of Children’s Exposure to Violence (Richters & Saltzman, Citation1990) which were phrased slightly different for each type of violence exposure: ‘How many times in your whole life have you seen people chased by someone who wanted to hurt them in your home/in your school?’ and ‘How many times in your whole life have you seen people beaten up by someone in your home/in your school?’ The responses ranged on a scale from 1 (never) to 4 (many times), and were averaged to form an index of indirect victimisation for each context. Higher scores indicate higher frequency of indirect exposure to violence at home (r = 0.40) and at school (r = 0.47).

Indirect and direct community victimisation

Both direct and indirect exposure to community violence were measured by fifteen items adapted from the Survey of Children’s Exposure to Violence (Richters & Saltzman, Citation1990) to suit the South African context. For direct victimisation, the adolescents were asked about being a victim of physical violence, threats and interpersonal crime in the community in life time; whereas for indirect community violence exposure, the items were about whether they had witnessed or heard about these same types of violence. Example questions are: ‘How many times in your whole life have you seen people robbed or mugged by someone?’, ‘…have you been seriously wounded by someone?’ Items were averaged, with higher scores indicating more exposure to direct community victimisation (α = 0.84) and indirect community victimisation (α = 0.90).

Indirect political victimisation

The indirect political victimisation scale was adapted from a previous study (Whitbeck, Hoyt, McMorris, Chen, & Stubben, Citation2001) to measure whether adolescents had heard or knew of any of South Africa’s colonial and historical events of Apartheid that happened to someone in their lives, such as a family, a friend or an acquaintance. The scale has 28 items related to political violence (e.g. forced removal, experience of being imprisoned, and incidents of racial discrimination). Example items are: ‘Have any of your family/friends or anyone you know ever been refused entry into a public place or area because of their race?’, ‘…ever been sent to prison or detained because of political views that opposed the government?’ The response options were ‘yes’, ‘no’, and ‘I don’t know’. The ‘yes’ responses were coded as 1 and summed to obtain an index of indirect exposure to political violence (possible range 0–28; α = 0.83).

Health risk behaviours

Five types of health risk behaviours were measured in the YRBS (Reddy et al., Citation2013): smoking, alcohol use, soft drug use, hard drug use and risky sexual behaviour. Smoking was measured by the frequency of recent cigarette use on a scale from 1 (0 days) to 7 (all 30 days). Alcohol use was measured by the frequency of recent use of alcohol and binge drinking, both on a scale from 1 (never) to 5 (very often). Soft drug use was measured by the frequency of recent marijuana use on a scale from 1 (never) to 5 (very often). Hard drug use was measured by the frequency of life time use of nine types of illegal drugs on a scale from 1 (never) to 5 (very often) that are relevant in the South African contexts, including glue (sniffed), TIK, Mandrax, cocaine, heroin, Whoonga, drug via needle injection, over-the-counter or prescription drugs (e.g. pain killers, cough mixtures and diet pills) and any hallucinant drugs (e.g. ecstasy, LSD, speed or magic mushrooms). Risky sexual behaviour was measured by the frequency of condom use on a scale from 1 (I have never had sex) to 6 (we always use a condom).

Since the scales differed among behaviours and the proportions of the participants who reported each of these health risky behaviours varied between 21.5 and 51.6% (see ), it was decided to dichotomise each risk behaviour such that 0 = no such behaviour at all and 1 = performed the risk behaviour (once or more than once). We then summed the number of risk behaviours and selected the participants with at least one risk behaviour for the analyses, resulting in a composite risk behaviour scale with scores ranging from 1 (one risk behaviour) to 5 (five risk behaviours) (M = 2.01, SD = 1.10, α = 0.55).

Table 1. Proportions of adolescents with and without health risk behaviours.

Emotion dysregulation

Participants’ emotion dysregulation was measured by the anger and sadness dysregulation subscales (10 items) of the Children’s Emotion Management Scales (CEMS; Zeman et al., Citation2002). Example questions are: ‘I do things like slam doors when I am angry’, ‘I wine/fuss about what is making me sad’. Responses ranged from 1 (never) to 5 (always). Scores were averaged, and higher scores indicate higher levels of emotion dysregulation (α = 0.76).

Analysis

Data were analysed using SPSS version 23. Significance was set at α = 0.05. Pearson correlation coefficients were examined to understand the intercorrelations among all the variables. Independent sampled t-tests were conducted to investigate the gender differences in the levels of violence exposure, emotion dysregulation and health risk behaviours. Next, hierarchical multiple regressions were conducted separately for boys and girls to understand the associations between violence exposure across different contexts and health risk behaviours, as well as the moderating role of emotion dysregulation in these associations. For both gender groups, age was entered in step 1, the five types of victimisations and emotion dysregulation were entered as main effects in step 2, and the product terms of each type of victimisation with emotion dysregulation were entered in step 3. All variables were first centred before the interactions were computed to reduce multicollinearity (Aiken & West, Citation1991).

Results

shows the intercorrelations of victimisation across different contexts, emotion dysregulation and the composite measure of health risk behaviours. Age was positively associated with risk behaviours (r = 0.18; p < 0.01). Being a boy was associated with more exposure to indirect school victimisation and direct community victimisation (r = −0.12 and −0.10, respectively; p’s < 0.01). Being a girl was associated with higher emotion dysregulation (r = 0.11; p < 0.01), whereas being a boy was associated with more health risk behaviours (r = −0.17; p’s < 0.01). Indirect school victimisation, indirect community victimisation, and direct community victimisation were positively associated with health risk behaviours (r’s = 0.12–0.27; p’s < 0.01). Higher levels of victimisation across different contexts were associated with more emotion dysregulation (r’s = 0.08–0.14; p’s < 0.01), except for indirect political victimisation (r = −0.14; p < 0.01). Emotion dysregulation was not associated with health risk behaviours (p > 0.05).

Table 2. Intercorrelations, means and standard deviations for all the independent and dependent variables.

When compared with girls, boys reported more exposure to indirect school victimisation, t (739) = 3.28, p < 0.001, and direct community victimisation, t (712) = 2.83, p < 0.01. No gender differences were found for other victimisation scales. Girls reported more emotion dysregulation than boys t (748) = −2.95, p < 0.01. Boys were more likely than girls to engage in health risk behaviours t (844) = 5.25, p < 0.001.

Exposure to violence and emotion dysregulation on health risk behaviours

Standardized regression coefficients and changes in R2 values from the multiple regressions are presented in for boys and girls.

Table 3. Hierarchical multiple regression of the effects of exposure to violence and emotion dysregulation on health risk behaviours in adolescents.

Boys. For boys, age accounted for 5% of the variance in health risk behaviours. When the five types of victimisation and emotion dysregulation were added, the variables together accounted for an additional 6% of the variance. In the final model, the change in variance was not significant. Age and direct community victimisation were unique predictors for health risk behaviours (both B’s = 0.22, p’s < 0.001).

Girls. For girls, age was not a significant predictor. When the five types of victimisation and emotion dysregulation were added in the model, the variables together accounted for an additional 9% of the variance. In the final model, the interactions accounted for an additional 5% of the variance. The final model showed that indirect school victimisation and direct community victimisation were unique predictors for health risk behaviours (Both B’s = 0.19, p’s < 0.01). The interaction of indirect home victimisation and emotion dysregulation (B = 16, p < 0.01), and the interaction of direct community victimisation and emotion dysregulation (B = 15, p < 0.05) significantly predicted health risk behaviours.

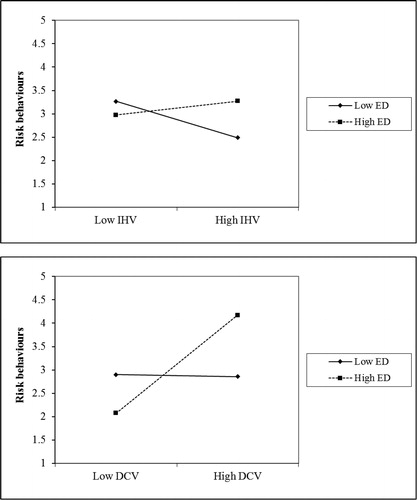

Further, simple slope analyses were conducted to examine these significant interactions (see ). For the interaction between indirect home victimisation and emotion dysregulation, the slopes of the regression line between home victimisation and health risk behaviours were significant for both high emotion dysregulation (B = 0.28, p < 0.001) and low emotion dysregulation (B = −0.28, p < 0.01). This suggests that girls with high emotion dysregulation, i.e. not able to regulate sadness and anger, performed more health risk behaviours when they had high exposure to indirect home victimisation compared to those who had low exposure to indirect home victimisation. Conversely, girls with low emotion dysregulation, i.e. better at regulating sadness and anger, performed less health risk behaviours when they had high exposure to indirect home victimisation compared to those who had low exposure to indirect home victimisation. For the interaction between direct community victimisation and emotion dysregulation, the slope was only significant for girls with high emotion dysregulation (B = 0.39, p < 0.001). Girls with high emotion dysregulation performed more health risk behaviours when they had higher exposure to direct community victimisation compared to those had lower exposure to direct community victimisation. Among adolescent girls with lower emotion dysregulation, the association between direct community victimisation and health risk behaviours was not significant (B = −0.06, p > 0.05).

Discussion

This study builds upon previous literature by supporting the detrimental effects of exposure to violence across different contexts on health risk behaviours in South African adolescents, while providing additional information on the moderating role of emotion dysregulation and the patterns of gender. Consistent with other research (Begle et al., Citation2011; Lee, Citation2012; Moreira et al., Citation2008; Voisin et al., Citation2011), this study showed that three out of five types of victimisation (indirect school victimisation and both indirect and direct community victimisation) were associated with increased risk for health risk behaviours among South African adolescents. Researchers (Harrison, Fulkerson, & Beebe, Citation1997; Hessler & Katz, Citation2010) have viewed the relationship between violence exposure and health risk behaviours in light of coping theory, suggesting that the engagement in risk behaviours might be one way individuals attempt to diminish negative affect (e.g. fear, nervousness) in the face of a stressful encounter (Cramer, Citation2000; Lazarus, Citation1993). Although it may result in a short-term ‘soothing’ effect (Tice, Bratslavsky, & Baumeister, Citation2001), ultimately this coping method is non-adaptive: a study showed that among maltreated adolescents, drinking alcohol with a motive to cope with negative affect is predictive of other problems associated with alcohol use, such as getting into fights and neglect life responsibilities (Goldstein, Vilhena-Churchill, Stewart, & Wekerle, Citation2012).

Our results revealed that boys and girls differed in the associations between the types of violence victimisation and health risk behaviours. Specifically, after accounting for other types of victimisation, being a direct victim of community violence predicted health risk behaviours in boys, whereas exposure to indirect school victimisation predicted health risk behaviours in girls. This result is in line with studies by Begle et al. (Citation2011) and Moreira et al. (Citation2008), who found that exposure to community violence has an effect on boys’ alcohol and drug use. Additionally, our t-tests showed that boys had more exposure to direct community victimisation than girls. In South Africa, boys may be more likely than girls to directly encounter community violence due to the fact that boys spend more time in the neighbourhood (Kaminer et al., Citation2013), which also potentially expose them to the highly available alcohol and drugs in many South African communities (Burton & Leoshcut, 2013), thus increases the likelihood of their health risk behaviours.

Although boys in our study also reported higher rates of indirect school victimisation than girls, this type of violence only had a negative influence on health risk behaviours in girls. The 2012 national school violence survey in South Africa showed that girls experience higher rates of sexual assault in school than their male counterparts, and are more likely than boys to report feelings of fear and anxiety associated with travelling to and from school (Burton & Leoshcut, 2013), suggesting that school violence generates high psychological stress for girls. In addition, an extensive literature has documented that girls are more prone to experiencing internalising symptoms than boys during adolescence (Hilt, Cha, & Nolen-Hoeksema, Citation2008; Mrug et al., Citation2008; Slone & Mayer, Citation2015; Sui et al., Citation2018). Taken together, our results suggest that engaging in health risk behaviours could be one way of girls’ attempt to cope with the adverse emotions aroused by exposure to school violence. This coping mechanism has been noted in Harrison et al. (Citation1997), in which they found that adolescent girls exposed to physical and sexual abuse have an increased likelihood of alcohol and drug use, and a higher proportion of girls than boys use these substances to cope with painful emotions and to escape problems. Additionally, our study showed that health risk behaviours in girls emerged when school violence was indirectly encountered through witnessing, suggesting that girls may be susceptible to the negative influence of violence even if the level of exposure is relatively less intense than direct victimisation. Since this study employed a cross-sectional design, future research should determine whether the gender differences in the effects of violence found in the current research are indeed resulted from these underlying processes.

In contrast to other studies (Brown et al., Citation2012; Hessler & Katz, Citation2010; Wills et al., Citation2016), this study showed that the inability to regulate sadness and anger did not directly influence health risk behaviours, possibly due to the reason that health risk behaviours in adolescents are influenced by a complex system of factors, such as mental health problems, attachment style, economic disadvantage, unhealthy family functioning, parental substance abuse and peer influence (Feeney, Peterson, Gallois, & Terry, Citation2000; Pumariega, Burakgazi, Unlu, Prajapati, & Dalkilic, Citation2014; Shek & Liang, Citation2015; Spijkerman, Van den Eijnden, Overbeek, & Engels, Citation2007). An important finding in our study is that emotion dysregulation moderated the relationship between violence exposure and health risk behaviours in girls. Consistent with Bender et al. (Citation2012), our t-tests showed that girls had higher emotion dysregulation than boys. Thus, for girls, their inability to regulate negative emotions may be a risk factor that exacerbates the consequences of violence exposure. Specifically, this study showed that the effects of indirect home victimisation and direct community victimisation were associated with more health risk behaviours in girls when they were unable to regulate sadness and anger. This result is consistent with research by Kliewer et al. (Citation2017), who demonstrated positive associations between cumulative psychosocial risks (including violence) and internalising and externalising symptoms in South African adolescents who had high emotion dysregulation. Similarly, in a sample of young adult women experiencing posttraumatic stress symptoms, emotion dysregulation increased the risk for later alcohol and drug use (Tull, Bardeen, DiLillo, Messman-Moore, & Gratz, Citation2015). From a developmental perspective, adolescent girls may be more vulnerable to psychological distress than boys because girls process stressors differently, such as having a tendency to ruminate—a repetitive and recurrent thinking about the traumatic event and its consequences (Dunn, Gilman, Willett, Slopen, & Molnar, Citation2012). This may create heightened negative effects for girls that interfere with their emotion regulation capacities to cope with violence effectively.

Implications for interventions

The results of this study provide avenues for the development of interventions to reduce health risk behaviours in adolescents exposed to violence. Schools can be prime sites for interventions to reach a large number of adolescents and combat the negative influence of violence on their development (Gevers & Flisher, 2012). For example, an evidence-based ‘Life Skills Training programme’ has been developed and implemented in the USA to combat health risk behaviours in youth through skills training in reducing stress and negative emotions, as well as resisting peer and media pressure to smoke or use substance. The programme has shown to not only positively influence the targeted behaviour (e.g. drug use) but to also generalise to other behaviours (e.g. HIV risk behaviour) (Griffin, Botvin, & Nichols, Citation2006). Other school-based interventions that use similar approaches to enhance social skills and self-management skills have also been found effective in reducing marijuana and alcohol use in adolescents (Das, Salam, Arshad, Finkelstein, & Bhutta, Citation2016; Scott-Sheldon, Carey, Elliott, Garey, & Carey, Citation2014). Akin to these interventions, a programme for South African adolescents specifically focused on health education, skills training in reducing stress and negative emotions, and resistance to peer pressure in high-risk situations may prevent health risk behaviours.

As informed by our result on the moderating role of emotion dysregulation in the association between violence exposure and health risk behaviours in girls, gender-specific risk behaviour interventions may be especially helpful. Emotion regulation reflects a fundamental aspect of youth development and is a modifiable skill that can be trained and acquired (Compas et al., Citation2014; Kliewer, Citation2016). Thus, for girls, one key approach in skills training in interventions could be strengthening their emotion regulation capacities to enhance adaptive coping and help them modulate their behaviours in high risk situations, such as violence exposure. Indeed, research has found that emotion regulation training is effective in combating risk behaviours—for example, a programme that consisted of 12 after-school sessions that focused on emotion education and building skills in emotion regulation (e.g. recognising feelings in self and others), successfully reduced early sexual activities even after 1 year follow-up among adolescents (Houck et al., Citation2016). In addition, it may also be beneficial to involve parents/caregivers in such a programme to provide them with the information about the associations between violence exposure, emotion dysregulation and health risk behaviours in adolescents; but more importantly, to enhance their own emotion regulation capacities, for them to learn how to provide adequate emotional support to their children, and improve child–caregiver relationship and parenting style. These positive influences in the family context are important for young people to appraise their feelings, learn about strategies for emotion management, and achieve competence in controlling emotions, thereby buffer the negative effects of violence exposure (Kliewer et al. Citation2004; Thompson & Meyer, Citation2007).

Limitations and directions for future research

The results of our study offer novel insights, however, several limitations should be noted. This study is cross-sectional in nature, thus, causal relationships cannot be inferred and the results should be interpreted with caution. Although longitudinal studies have established the negative impact of violence on health risk behaviours (Begle et al., Citation2011; Wilson, Woods, Emerson, & Donenberg, Citation2012), a bidirectional relationship is possible, such that engaging in risk behaviours may predispose adolescents to more violence exposure, e.g. by their involvement in drug dealings (Duke, Smith, Oberleitner, Westphal, & McKee, Citation2018; van der Merwe & Dawes, Citation2007; Mrug & Windle, Citation2009). To establish the causal relationships, more longitudinal evidence is needed to fully understand the association between exposure to violence and health risk behaviours in adolescents. Another limitation is that due to the differences in scale formats and the small sample sizes for the participants regarding each risk behaviour, the risk behaviour variable in our study was computed as a composite score—consisting of smoking, alcohol use, soft and hard drug use, and risky sexual behaviour. Although the results are able to provide an overview of the effects of violence on adolescent health risk behaviours, information on the effects of violence on specific behaviours is lost, prohibiting our ability to draw conclusions about the effect of exposure to violence on, e.g. alcohol use versus soft drug use. Future research should distinguish health risk behaviours in order to provide refined and targeted recommendations based on the effects of violence on separate behaviours. Unexpectedly, we also found that girls with low emotion dysregulation reported less health risk behaviours at high levels of exposure to indirect home victimisation, compared to low levels of exposure. This may suggest that low emotion dysregulation is a protective factor for risk behaviours only when the frequency of violence exposure reaches a certain threshold. Future research may explore this in more details. Lastly, only victimisation in the community context was differentiated into indirect and direct exposure in our study. Future research may examine both indirect and direct forms of victimisation for all contexts of exposure, as indirect and direct victimisation across contexts have been found to have a differential impact on youth psychological and behavioural adjustment (Barbarin, Richter, & de Wet, Citation2001; Shields et al., Citation2009; Vermeiren, Schwab-Stone, Deboutte, Leckman, & Ruchkin, Citation2003). This differentiation of violence could potentially enhance the understanding of the negative effects of different types of victimisation and provide more refined recommendations to alleviate these effects.

Conclusion

This study provides insight into the associations between violence exposure across multiple contexts, emotion dysregulation and health risk behaviours in South African adolescents in the Western Cape Province. Gender patterns were found in the association between violence exposure and health risk behaviours and that emotion regulation moderated the effects of violence for girls. The results of the study have implications for the development of interventions to reduce health risk behaviours in adolescents exposed to violence. Building competencies in emotion regulation in adolescents, particularly girls, may be helpful to strengthen resilience to the negative effects of violence on health risk behaviours.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation (NRF) of South Africa under Grant SFH160603167769 (Opinions expressed and conclusions arrived at, are those of the authors and are not necessarily to be attributed to the NRF); National Institute on Drug Abuse, Violence, Drug Use & AIDS under Grant 1R21DA030298.

Data availability statement

Data available on request from the authors. The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, X. S., upon reasonable request.

Note

Notes

1 A former system of institutionalized racial segregation in South Africa (1948–1994) in which access to economic resources, medical care and educational and employment opportunity were restricted for people socially classified as ‘non-white’.

References

- Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

- Albus, K. E., Weist, M. D., & Perez-Smith, A. M. (2004). Associations between youth risk behaviour and exposure to violence: Implications for the provision of mental health services in urban schools. Behaviour Modification, 28(4), 548–564. doi:10.1177/0145445503259512

- Bach, J. M., & Louw, D. (2010). Depression and exposure to violence among Venda and Northern Sotho adolescents in South Africa: Original article. African Journal of Psychiatry, 13(1), 25–35. doi:10.4314/ajpsy.v13i1.53426

- Barbarin, O. A., Richter, L., & de Wet, T. (2001). Exposure to violence, coping resources, and psychological adjustment of South African children. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 71, 16–25. doi:10.1037//0002-9432.71.1.16

- Begle, A. M., Hanson, R. F., Danielson, C. K., McCart, M. R., Ruggiero, K. J., Amstadter, A. B., & … Kilpatrick, D. G. (2011). Longitudinal pathways of victimisation, substance use, and delinquency: Findings from the National Survey of Adolescents. Addictive Behaviours, 36(7), 682–689. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.12.026

- Bell, C. C., & McBride, D. F. (2010). Affect regulation and prevention of risky behaviours. Journal of the American Medical Association, 304(5), 565–566. doi:10.1001/jama.2010.1058

- Bender, P. K., Reinholdt-Dunne, M. L., Esbjorn, B. H., & Pons, F. (2012). Emotion dysregulation and anxiety in children and adolescents: Gender differences. Personality and Individual Differences, 53(3), 284–288. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2012.03.027

- Bobrowski, K. J., Czabala, J. C., & Brykczynska, C. (2007). Risk behaviours as a dimension of mental health assessment in adolescents. Archives of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, 1(2), 17–26.

- Botticello, A. L. (2009). A multilevel analysis of gender differences in psychological distress over time. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 19(2), 217–247.

- Brook, D. W., Rubenstone, E., Zhang, C., Morojele, N. K., & Brook, J. S. (2011). Environmental stressors, low well-being, smoking, and alcohol use among South African adolescents. Social Science and Medicine, 72(9), 1447–1453.

- Brook, J. S., Morojele, N. K., Pahl, K., & Brook, D. W. (2006). Predictors of drug use among South African adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health, 38(1), 26–34. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.08.004

- Brown, L. K., Houck, C., Lescano, C., Donenberg, G., Tolou-Shams, M., & Mello, J. (2012). Affect regulation and HIV risk among youth in therapeutic schools. AIDS and Behaviour, 16(8), 2272–2278. doi:10.1007/s10461-012-0220-3

- Burton, P. & Leoshcut, L. (2013). School violence in South Africa: Results of the 2012 national school violence study. Cape Town: Centre for Justice and Crime Prevention.

- Casey, B. J., Jones, R. M., Levita, L., Libby, V., Pattwell, S. S., Ruberry, E. J., et al. (2010). The storm and stress of adolescence: Insights from human imaging and mouse genetics. Developmental Psychobiology, 52, 225–235. doi:10.1002/dev.20447

- Coleman, C., Wileyto, E. P., Lenhart, C. M., & Patterson, F. (2014). Multiple health risk behaviours in adolescents: An examination of Youth Risk Behaviour Survey data. American Journal of Health Education, 45(5), 271–277. doi:10.1080/19325037.2014.933138

- Compas, B. E., Jaser, S. S., Dunbar, J. P., Watson, K. H., Bettis, A. H., Gruhn, M. A., & Williams, E. K. (2014). Coping and emotion regulation from childhood to early adulthood: Points of convergence and divergence. Australian Journal of Psychology, 66(2), 71–81. doi:10.1111/ajpy.12043

- Cooley, J. L. (2019). The interactive effects of coping strategies and emotion dysregulation on experiences of peer victimisation during middle childhood. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences and Engineering. ProQuest Information & Learning. Retrieved from http://login.ezproxy.ub.unimaas.nl/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=psyh&AN=2018-58621-094&site=ehost-live&scope=site

- Cramer, P. (2000). Defense mechanisms in psychology today: Further processes for adaptation. American Psychologist, 55, 637–646. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.55.6.637

- Croisant, S. P., Haque Laz, T., Rahman, M., & Berenson, A. B. (2013). Gender differences in risk behaviours among high school youth. Global Advances in Health and Medicine, 2(5), 16–22. doi:10.7453/gahmj.2013.045

- Das, J. K., Salam, R. A., Arshad, A., Finkelstein, Y., & Bhutta, Z. A. (2016). Interventions for adolescent substance abuse: An overview of systematic reviews. Journal of Adolescent Health, 59(4), 61–75. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.06.021

- Das-Munshi, J., Lund, C., Mathews, C., Clark, C., Rothon, C., & Stansfeld, S. (2016). Mental health inequalities in adolescents growing up in post-apartheid South Africa: Cross-sectional survey, SHaW Study. PloS One, 11(5), e0154478. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0154478

- Duke, A. A., Smith, K. M. Z., Oberleitner, L. M. S., Westphal, A., & McKee, S. A. (2018). Alcohol, drugs, and violence: A meta-meta-analysis. Psychology of Violence, 8(2), 238–249. doi:10.1037/vio0000106

- Dunn, E. C., Gilman, S. E., Willett, J. B., Slopen, N. B., & Molnar, B. E. (2012). The impact of exposure to interpersonal violence on gender differences in adolescent-onset major depression: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). Depression and Anxiety, 29(5), 392–399. doi:10.1002/da.21916

- Dvir, Y., Ford, J. D., Hill, M., & Frazier, J. A. (2014). Childhood maltreatment, emotional dysregulation, and psychiatric comorbidities. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 22, 149–161.

- El Achhab, Y., El Ammari, A., El Kazdouh, H., Najdi, A., Berraho, M., Tachfouti, N., … & Nejjari, C. (2016). Health risk behaviours amongst school adolescents: Protocol for a mixed methods study. BMC Public Health, 16(1), 1209. doi:10.1186/s12889-016-3873-4

- Feeney, J. A., Peterson, C., Gallois, C., & Terry, D. J. (2000). Attachment style as a piedictor of sexual attitudes and behaviour in late Adolescence. Psychology & Health, 14(6), 1105–1122. doi:10.1080/08870440008407370

- Finkelhor, D., Ormrod, R. K., & Turner, H. A. (2007). Poly-victimisation: A neglected component in child victimisation. Child Abuse and Neglect, 31, 7–26. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2006.06.008

- Gevers, A. & Flisher, A. (2012). School-based youth violence prevention interventions. In Ward, C., van der Merwe, A., Dawes, A. (Eds.), Youth violence: Sources and solutions in South Africa (pp. 175–121). Cape Town, South Africa: UCT Press.

- Goldstein, A. L., Vilhena-Churchill, N., Stewart, S. H., & Wekerle, C. (2012). Coping motives as moderators of the relationship between emotional distress and alcohol problems in a sample of adolescents involved with child welfare. Advances in Mental Health, 11(1), 67–75. doi:10.5172/jamh.2012.11.1.67

- Griffin, K., Botvin, G., & Nichols, T. (2006). Effects of a school-based drug abuse prevention program for adolescents on HIV risk behaviour in young adulthood. Prevention Science, 7(1), 103–112. doi:10.1007/s11121-006-0025-6

- Harrison, P. A., Fulkerson, J. A., & Beebe, T. J. (1997). Multiple substance use among adolescent physical and sexual abuse victims. Child Abuse and Neglect, 21(6), 529–539. doi:10.1016/S0145-2134(97)00013-6

- Hessler, D. M. & Katz, L. F. (2010). Associations between emotional competence and adolescent risky behaviour. Journal of Adolescence, 33, 241–246. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2009.04.007

- Hilt, L. M., Cha, C. B., & Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2008). Nonsuicidal self-injury in young adolescent girls: Moderators of the distress-function relationship. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76(1), 63–71. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.76.1.63

- Houck, C. D., Barker, D. H., Hadley, W., Brown, L. K., Lansing, A., Almy, B., & Hancock, E. (2016). The 1-year impact of an emotion regulation intervention on early adolescent health risk behaviours. Health Psychology, 35(9), 1036–1045. doi:10.1037/hea0000360

- Kaminer, D., du Plessis, B., Hardy, A., & Benjamin, A. (2013). Exposure to violence across multiple sites among young South African adolescents. Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology, 19(2), 112. doi:10.1037/a0032487

- Kann, L., McManus, T., Harris, W. A., Shanklin, S. L., Flint, K. H., Hawkins, J., & … Zaza, S. (2016). Youth Risk Behaviour Surveillance – United States, 2015. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Surveillance Summaries (Washington, D.C.: 2002), 65(6), 1–174. doi:10.15585/mmwr.ss6506a1

- Kelly, B. M., Schwartz, D., Gorman, A. H., & Nakamoto, J. (2008). Violent victimisation in the community and children’s subsequent peer rejection: The mediating role of emotion dysregulation. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 36, 175–185. doi:10.1007/s10802-007-9168-6

- Kim, J., & Cicchetti, D. (2010). Longitudinal pathways linking child maltreatment, emotion regulation, peer relations, and psychopathology. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 51, 706–716. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02202.x

- Kliewer, W. (2016). Victimisation and biological stress responses in urban adolescents: Emotion regulation as a moderator. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 45(9), 1812–1823. doi:10.1007/s10964-015-0398-6

- Kliewer, W., Cunningham, J. N., Diehl, R., Parrish, K. A., Walker, J. M., Atiyeh, C., & … Mejia, R. (2004). Violence exposure and adjustment in inner-city youth: Child and caregiver emotion regulation skill, caregiver-child relationship quality, and neighborhood cohesion as protective factor. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 33(3), 477–487. doi:10.1207/s15374424jccp3303_5

- Kliewer, W., Pillay, B., Swain, K., Rawatlal, N., Borre, A., Naidu, T., & … Vawda, N. (2017). Cumulative risk, emotion dysregulation, and adjustment in South African Youth. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 26(7), 1768–1779. doi:10.1007/s10826-017-0708-6

- Lazarus, R. S. (1993). Coping theory and research: Past, present, and future. Psychosomatic Medicine, 55, 234−247.

- Lee, R. (2012). Community violence exposure and adolescent substance use: Does monitoring and positive parenting moderate risk in urban communities? Journal of Community Psychology, 40(4), 406–421. doi:10.1002/jcop.20520

- MacArthur, G. J., Smith, M. C., Melotti, R., Heron, J., Macleod, J., Hickman, M., … & Lewis, G. (2012). Patterns of alcohol use and multiple risk behaviour by gender during early and late adolescence: The ALSPAC cohort. Journal of Public Health, 34(suppl_1), i20–i30. doi:10.1093/pubmed/fds006

- Masten, A. S. & Coatsworth, J. D. (1998). The development of competence in favorable and unfavorable environments. American Psychologist, 53(2), 205–220. doi:10.1037//0003-066X.53.2.205

- McLaughlin, K. A., Hatzenbuehler, M. L., & Hilt, L. M. (2009). Emotion dysregulation as a mechanism linking peer victimisation to internalising symptoms in adolescents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 77(5), 894–904. doi:10.1037/a0015760

- Mennis, J., & Mason, M. J. (2012). Social and geographic contexts of adolescent substance use: The moderating effects of age and gender. Social Networks, 34(1), 150–157. doi:10.1016/j.socnet.2010.10.003

- Moffitt, T. E., Arseneault, L., Baucom, D., Caspi, A., Chen, E., Danese, A., … Kuper-Yamanaka, M. (2013). Childhood exposure to violence and lifelong health: Clinical intervention science and stress biology research join forces. Development and Psychopathology, 25(4), 1619–1634. doi:10.1017/S0954579413000801

- Moreira, T. C., Belmonte, E. L., Vieira, F. R., Noto, A. R., Ferigolo, M., & Barros, H. M. (2008). Community violence and alcohol abuse among adolescents: A sex comparison. Jornal De Pediatria, 84(3), 244–250.

- Morojele, N. K., & Brook, J. S. (2006). Substance use and multiple victimisation among adolescents in South Africa. Addictive Behaviours, 31(7), 1163–1176. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.09.009

- Mrug, S., & Windle, M. (2009). Initiation of alcohol use in early adolescence: Links with exposure to community violence across time. Addictive Behaviours, 34(9), 779–781. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.04.004

- Mrug, S., Loosier, P. S., & Windle, M. (2008). Violence exposure across multiple contexts: Individual and joint effects on adjustment. The American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 78(1), 70–84. doi:10.1037/0002-9432.78.1.70

- Mrug, S., & Windle, M. (2010). Prospective effects of violence exposure across multiple contexts on early adolescents’ internalizing and externalizing problems. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 51, 953–961. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02222.x

- Norman, R., Matzopoulos, R., Groenewald, P., & Bradshaw, D. (2007). The high burden of injuries in South Africa. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 85(9), 695–702. doi:10.2471/BLT.06.037184

- Pumariega, A. J., Burakgazi, H., Unlu, A., Prajapati, P., & Dalkilic, A. (2014). Substance abuse: Risk factors for Turkish youth. Bulletin of Clinical Psychopharmacology, 24(1), 5–14. doi:10.5455/bcp.20140317061538

- Reddy, S. P., James, S., Sewpaul, R., Sifunda, S., Ellahebokus, A., Kambaran, N. S., & Omardien, R. G. (2013). Umthente Uhlaba Usamila: The 3rd South African national youth risk behaviour survey 2011.

- Richters, J. E., & Saltzman, W. (1990). Survey of exposure to community violence: Self report version. Rockville, MD: National Institute of Mental Health.

- Schiff, M., Pat-Horenczyk, R., Benbenishty, R., Brom, D., Baum, N., & Astor, R. A. (2012). High school students’ posttraumatic symptoms, substance abuse and involvement in violence in the aftermath of war. Social Science and Medicine, 75(7), 1321–1328. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.05.010

- Scott-Sheldon, L. J., Carey, K. B., Elliott, J. C., Garey, L., & Carey, M. P. (2014). Efficacy of alcohol interventions for first-year college students: A meta-analytic review of randomized controlled trials. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 82(2), 177–188. doi:10.1037/a0035192

- Sharkey, P. T., Tirado-Strayer, N., Papachristos, A. V., & Raver, C. C. (2012). The effect of local violence on children's attention and impulse control. American Journal of Public Health, 102(12), 2287–2293. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2012.300789

- Shek, D. L., & Liang, J. (2015). Risk factors and protective factors in substance abuse in Chinese adolescents in Hong Kong. In T. Y. Lee, D. L. Shek, R. F. Sun, T. Y. Lee, D. L. Shek, R. F. Sun (Eds.), Student well-being in Chinese adolescents in Hong Kong: Theory, intervention and research (pp. 237–253). New York, NY: Springer Science + Business Media.

- Shields, N., Nadasen, K., & Pierce, L. (2009). A comparison of the effects of witnessing community violence and direct victimisation among children in Cape Town, South Africa. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 24(7), 1192–1208. doi:10.1177/0886260508322184

- Slone, M., & Mayer, Y. (2015). Gender differences in mental health consequences of exposure to political violence among Israeli adolescents. Children and Youth Services Review, 58, 170–178. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2015.09.013

- Smokowski, P., Mann, E., Reynolds, A., & Fraser, M. (2004). Childhood risk and resiliency factors and late adolescent adjustment in inner city minority youth. Children and Youth Services Review, 26, 63–91. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2003.11.003

- South African Police Service. (2016). Annual report 2015/2016. Retrieved from https://www.saps.gov.za/about/stratframework/annual_report/2015_2016/saps_annual_report_2015_2016.pdf

- Spielman, A. J., Caruso, L. S., & Glovinsky, P. B. (1987). A behavioural perspective on insomnia treatment. Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 10(4), 541–553. doi:10.1016/S0193-953X(18)30532-X

- Spijkerman, R., Van den Eijnden, R. M., Overbeek, G., & Engels, R. E. (2007). The impact of peer and parental norms and behaviour on adolescent drinking: The role of drinker prototypes. Psychology & Health, 22(1), 7–29. doi:10.1080/14768320500537688

- Steinberg, L. (2007). Risk taking in adolescence: New perspectives from brain and behavioural science. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 16(2), 55–59. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8721.2007.00475.x

- Sui, X., Massar, K., Kessels, L. T. E., Reddy, P. S., Ruiter, R. A. C., Sanders-Phillips, K. (2018). Violence exposure in South African adolescents: Differential and cumulative effects on psychological functioning. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 34, 1–27. doi:10.1177/0886260518788363

- Thompson R. A., & Meyer S. (2007). Socialization of emotion regulation in the family. In Gross J. J. (Ed.) Handbook of emotion regulation (pp. 249–268). New York: Guilford Press.

- Tice, D. M., Bratslavsky, E., & Baumeister, R. F. (2001). Emotional distress regulation takes precedence over impulse control: If you feel bad, do it! Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 80(1), 53–67. doi:10.1037//0022-3514.80.1.53

- Tull, M. T., Bardeen, J. R., DiLillo, D., Messman-Moore, T., & Gratz, K. L. (2015). A prospective investigation of emotion dysregulation as a moderator of the relation between posttraumatic stress symptoms and substance use severity. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 29, 52–60. doi:10.1016/j.janxdis.2014.11.003

- van der Merwe, A. & Dawes, A. (2007). Youth violence: A review of risk factors, causal pathways and effective intervention, Journal of Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 19(2), 95–113. doi:10.2989/17280580709486645

- Vermeiren, R., Schwab-Stone, M., Deboutte, D., Leckman, P., & Ruchkin, V. (2003). Violence exposure and substance use in adolescents: Findings from three countries. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 42(10), 1261.

- Voisin, D. R., Jenkins, E. J., & Takahashi, L. (2011). Toward a conceptual model linking community violence exposure to HIV-related risk behaviours among adolescents: Directions for research. Journal of Adolescent Health, 49(3), 230–236. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.01.002

- Whitbeck, L. B., Hoyt, D. R., McMorris, B. J., Chen, X., & Stubben, J. D. (2001). Perceived discrimination and early substance abuse among American Indian children. Journal of Health and Social Behaviour, 42(4), 405–424. doi:10.2307/3090187

- Wills, T. A., Simons, J. S., Sussman, S., & Knight, R. (2016). Emotional self-control and dysregulation: A dual-process analysis of pathways to externalising/internalising symptomatology and positive well-being in younger adolescents. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 163, 37–45. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.08.039

- Wills, T. A., Walker, C., Mendoza, D., & Ainette, M. G. (2006). Behavioural and emotional self-control: Relations to substance use in samples of middle and high school students. Psychology of Addictive Behaviours: Journal of the Society of Psychologists in Addictive Behaviours, 20(3), 265–278. doi:10.1037/0893-164X.20.3.265

- Wilson, H. W., Woods, B. A., Emerson, E., & Donenberg, G. R. (2012). Patterns of violence exposure and sexual risk in low-income, urban African American girls. Psychology of Violence, 2(2), 194. doi:10.1037/a0027265

- Zeman, J., Shipman, K., & Penza-Clyve, S. (2001). Development and initial validation of the Children’s Sadness Management Scale. Journal of Nonverbal Behaviour, 25(3), 187–205.

- Zeman, J., Shipman, K., & Suveg, C. (2002). Anger and sadness regulation: Predictions to internalising and externalising symptoms in children. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 31(3), 393–398. doi:10.1207/S15374424JCCP3103_11