Abstract

NGSS scientific and engineering practices include “asking questions” and “obtaining, evaluating and communicating information.” These are skills that students need to learn and practice to become lifelong science learners and they are skills that these instructional resources help teachers to teach.

Harmful false claims about science are proliferating, such as “vaccines cause autism,” “climate change is a hoax,” and “COVID viruses are so small that wearing a mask won’t help.” To help science teachers address this challenge, the nonprofit Media Literacy Now developed a first-of-its-kind online database where teachers can find and access instructional materials to help students resist false and misleading information (see https://medialiteracynow.org/science-resources). Development of the database was funded by a grant from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI).

Acceptance of inaccurate science-related claims has caused significant harm, including hundreds of thousands of unnecessary deaths during the pandemic (Smith and Plumley Citation2022). However, science teachers understand that evaluating information about science is difficult for many students, a fact well documented by research (Breakstone et al. Citation2019). Students need to develop competencies to cope with the glut of information—too much of it inaccurate, false, or misleading—available to them at the touch of a button, including posts on TikTok, Instagram, YouTube, and other social media.

Several states are already addressing the challenge of inaccurate scientific claims. For example, New Jersey Governor Phil Murphy signed a law requiring K-12 media literacy education, saying, “It is our responsibility to ensure our nation’s future leaders are equipped with the tools necessary to identify fact from fiction” (State of New Jersey and Office of the Governor Citation2023).

A key impetus for teaching how to better evaluate information is that science educators know students will continue asking and answering questions about science-related topics after they leave school—questions about treating emerging diseases (such as RSV), mitigating allergies, dieting safely, supporting mental health for family members, whether and how individuals or government should pay for green energy, and which advertisements to believe, to name just a few. For students to continue to learn about science after they leave school, including about topics they never studied, they need to learn how to find trustworthy scientific information. This is the primary recommendation in a report published last September, also funded by HHMI, called Learning to Find Trustworthy Scientific Information (Zucker and McNeill Citation2023).

Evaluating claims about science is well aligned with science and engineering practices in the Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS) (National Research Council Citation2013). “Asking questions” is a fundamental science and engineering practice, and so is “obtaining, evaluating, and communicating information,” as is “engaging in argument from evidence.” Moreover, applying “claim-evidence-reasoning” thinking is both a key to understanding science and an important practice whenever people make informed decisions about science-related issues throughout their lives.

Resources in the database

A team of five experienced science educators scoured dozens of curriculum websites for appropriate lesson plans, videos, and games. We found that there are hundreds, if not thousands, of materials online, and most are free. One internet source alone includes more than 500 media literacy lessons! It is not feasible to list and describe all the resources.

Instead, the goal has been to illustrate the variety of offerings available to teachers and the sources that provide them. Nearly three-dozen sources of materials are included in the database, including five science teacher journals, many nonprofit media literacy education groups, news organizations, PBS LearningMedia, colleges and universities, individual science educators, and even a few providers outside the U.S.

Resources do not always fall neatly into grade level categories because students’ abilities and experiences differ so much. However, searching the database for middle school items results in a list of more than 50 resources. Using some of the resources would take teachers only a few minutes, while another is a series of six lessons each taking a full class period. Many resources include free videos. Some are games. Those that include lesson plans are identified as such. Similarly, resources marked as classroom ready require no additional work by the teacher beyond using the materials thoughtfully.

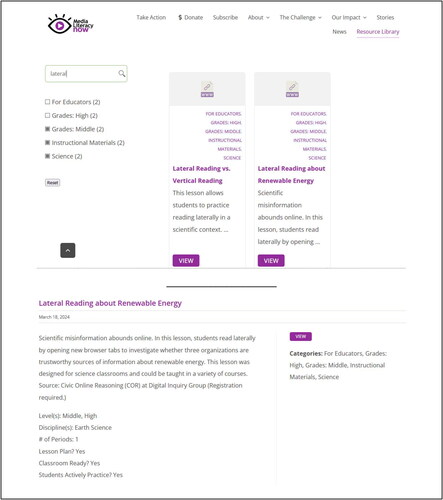

An example of a search of the instructional materials database is shown in , where a user searched for middle school materials that include the word “lateral.” “Lateral reading” is the term used to indicate that people faced with a questionable claim should move away from the web page or website where the claim was made and instead investigate the source of the claim as well as finding out what other sources say about the claim. Research shows that lateral reading helps people resist misinformation (e.g., Brodsky et al. Citation2021).

FIGURE 1: Shown at the top is a sample search and two thumbnail results. Clicking “VIEW” for one of the instructional resources found in the search leads to a longer description of that resource, as shown below for the resource Lateral Reading about Renewable Energy.

Many middle school teachers who use lessons about misinformation know that these activities are important. A California science teacher wrote, “I think my students learned to critically think about things they see that see and to think about purpose. They now know how to do a little research to get more information.” A teacher in Maine said the most important thing about such activities is “to question the reliability of sources and know that not everyone has the best intentions.” However, these are teachers who are already teaching about misinformation. The challenge is to help more science teachers find and use materials that fit their and their students’ needs.

To that end, some resources in the database focus on a particular science discipline, such as Earth Science or Biology, while others are appropriate in almost any classroom. For example, whether and how to use Wikipedia to find trustworthy information is a topic both relevant and important in civics, social studies, and history, as well as in science. Particularly in the elementary grades, but not only there, students need to learn general media literacy skills, such as how to use search engines effectively, or how to differentiate different parts of news articles, such as paid promotions that may appear side-by-side with the news.

Anyone can use this database. Please help us spread the word and increase attention in K-12 science education to mitigating the growing challenge of scientific misinformation. •

Online resource

Media Literacy Now: A searchable database of Instructional materials for teaching about misinformation – https://medialiteracynow.org/science-resources

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Andy Zucker

Andy Zucker ([email protected]) is a former science teacher who has written about K-12 education policy, scientific misinformation, media literacy, and science education standards, including the recent report Learning to Find Trustworthy Scientific Information.

REFERENCES

- Breakstone, J., M. Smith, S. Wineburg, A. Rapaport, J. Carle, M. Garland, and A. Saavedra. 2019. Students’ Civic Online Reasoning: A National Portrait. Stanford History Education Group. https://purl.stanford.edu/cz440cm8408.

- Brodsky, J. E., P. J. Brooks, D. Scimeca, P. Galati, R. Todorova, and M. Caulfield. 2021. “Associations between Online Instruction in Lateral Reading Strategies and Fact-Checking COVID-19 News among College Students.” AERA Open 7: 233285842110389. https://doi.org/10.1177/23328584211038937.

- National Research Council. 2013. Next Generation Science Standards: For States, By States. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

- Smith, P. S., and C. L. Plumley. 2022. K-12 science education in the United States: A landscape study for improving the field. Carnegie Corporation: New York.

- State of New Jersey, Office of the Governor. 2023. January 4. Governor Murphy signs bipartisan legislation establishing first in the nation K-12 information literacy education.

- Zucker, A., and E. McNeill. 2023. Learning to find trustworthy scientific information. Media Literacy Now. https://medialiteracynow.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Learning-to-Find-Trustworthy-Scientific-Information.pdf.