Abstract

California’s 2014 Sustainable Groundwater Management Act is a grand policy experiment that provides an unprecedented opportunity to analyze five core concepts in environmental governance: cooperation, institutional diversity, environmental justice, state oversight, and leadership. This article summarizes the research questions associated with these core concepts and the contributions of the other articles in this special issue, which emerged from ongoing interactions between a community of SGMA researchers and practitioners. The lessons learned from the special issue provide guideposts for SGMA research going forward, as well as research on environmental and water governance in other contexts.

Introduction

In 2014, California passed the landmark Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (SGMA), which established a state-wide mandate for the creation of new groundwater management institutions for high and medium priority basins in California. SGMA required each basin to establish one or more Groundwater Sustainability Agencies (GSAs) by 2017, which then develop and implement Groundwater Sustainability Plans (GSPs) by 2020 or 2022 depending on basin priority. Once completed, the GSP has twenty years to achieve “sustainability,” defined as avoiding a set of “undesirable results.” Reflecting principles of collaborative governance, the SGMA is expected to consider the local perspectives of multiple stakeholders including disadvantaged communities. Two California state agencies, the Department of Water Resources (DWR) and the State Water Resources Control Board (SWRCB), oversee the SGMA process. SGMA is a dramatic policy change in California, which historically has relied on mostly voluntary groundwater management institutions.

The implementation of SGMA presents an unprecedented opportunity to study one of the most important theoretical questions in the field of environmental governance: the evolution of new governance institutions for managing common-pool resources (Blomquist, Schlager, and Heikkila Citation2004; Brown, Langridge, and Rudestam Citation2016; Ostrom Citation1990; Schlager, Blomquist, and Tang Citation1994). Groundwater is a classic example of a common pool resource that is unsustainable when people ignore the social costs of their individual resource-use decisions. The central focus of Elinor Ostrom’s (Citation1990) Nobel-prize winning research was how people create local governance institutions to catalyze cooperation and resolve conflict in common-pool resource management. SGMA requires local government agencies with water management or land-use responsibilities in high and medium priority basins, so-called “eligible agencies,” to collectively establish institutions for groundwater governance through the formation of GSAs and GSPs. These new institutions are tasked with developing innovative management strategies and governing groundwater use to achieve SGMA’s definition of sustainability.

SGMA is thus a real-world analog to the countless social dilemma experiments that have been conducted since at least the 1950s, which examine the individual, group, and institutional variables related to cooperation, institutional evolution, and collective outcomes (Balliet Citation2010; Dawes and Messick Citation2000; Kollock Citation1998; Komorita Citation2019). But for SGMA, understanding the drivers of cooperation and institutional evolution has crucial social, environmental, and economic implications—the groundwater basins covered by SGMA account for 96% of the pumping in California and groundwater contributes approximately 38% of California’s water supply in average years (DWR Citation2015).

SGMA is an important laboratory for studying environmental justice, equity, and political power in the context of environmental governance. Collective-action research has traditionally been concerned with economic efficiency: how to achieve mutual benefits in the face of incentives that lead to socially undesirable outcomes. More recent research focuses on procedural and distributive justice with respect to how the benefits and costs of collective action are distributed among different actors (Moe Citation2005; Morrison et al. Citation2019, Purdy Citation2012). SGMA includes a mandate for engaging all interested water users and specifically disadvantaged communities. The extent and nature of engagement is reflected in the structure of representation and collective-choice rules governing GSA and GSP decisions, which in turn has implications for procedural justice (Hamilton Citation2018; Tyler and Blader Citation2000). SGMA and its implementation have distributive consequences in terms of who benefits and pays for management actions and how various sustainability goals are experienced (Smith and McDonough Citation2001). The differential power of stakeholders is expressed in their ability to shape the procedural rules and distributional outcomes (Purdy Citation2012). The concept of environmental justice has become a prominent part of the discourse among water policy stakeholders in California.

This special issue brings together researchers and practitioners who are interested in the theoretical and practical questions regarding cooperation and equity in SGMA. Recognizing the research opportunity afforded by SGMA, multiple universities across the country formed SGMA research teams often focusing on a set of case study basins. At the same time, a statewide network of practitioners and facilitators has continued to share lessons on how to effectively promote equity and cooperation in GSA and GSP development. Informal collaborations were initiated with the facilitators and research groups to help improve overall knowledge about SGMA, and to support coordination that could help avoid redundant research efforts in the same basins. As part of these collaborations, UC Davis and DWR co-sponsored a Sustainable Groundwater Management Act Governance Conference in Spring 2018, which informed the following questions that are the foundation of this special issue:

What are the drivers of cooperation among SGMA stakeholders?

How effective will the diversity of institutional arrangements under SGMA be in addressing groundwater sustainability?

How is SGMA addressing questions of environmental justice?

What is the role of the state in shaping SGMA at the local level?

What is the role of facilitation and leadership in SGMA?

The remainder of this introductory article will provide a background and status update of SGMA, and then briefly describe each of these questions and summarize the lessons learned from the special issue articles. We do not intend to provide a full literature review for each of these questions.

The Evolution of a Statewide Mandate for Groundwater Management in California

The legal and cultural context of California’s historic groundwater governance informs its current structure. Leahy (Citation2016) chronicles numerous previous attempts to regulate groundwater use, beginning in 1914, and contrasts the long history of institutional evolution with the remarkably short timeframe it took to negotiate the 2014 SGMA legislation, which Leahy (p.5) remarks is “an example of how what occurs overnight can be a century in the making.” The incremental history of groundwater management is at least in part due to the complexity and invisibility of groundwater in comparison to surface water, which continues to hinder policymakers and users from developing a strong understanding of how groundwater basins worked. An 1861 Ohio court case [Frazier v. Brown, 12 Ohio St. 294] famously concluded that groundwater was too “secret, occult and concealed” to regulate. Even today, using sticks and plumb bobs to find water, water dowsers, sometimes called water witches, are still employed to suggest new well locations (Alley et al. Citation2016). Further, due to highly variable hydrologic conditions no single management regime can be applied to all of California’s groundwater basins. Variation includes the setting of the basin, hydrogeologic information such as lithology; storage; transmissivity, previous groundwater management efforts within the basins, and water quality conditions (DWR Citation2003).

Like much of the western United States, California’s historic groundwater use had long been understood as unsustainable (DWR Citation2015). The complex western legal framework regulating water is generally based on the principles of beneficial use and prior appropriation. Under prior appropriation, the first to use a resource has a continuing right to use it, and that right is senior to others that may also have rights to access the resource. Prior appropriation laws facilitated the federal policy goal to settle the West, as it was believed that certainty in the ability to access water encouraged stability and investment in lands (Bryner and Purcell Citation2003). Thus, the laws in inherently favor the status quo.

In California prior appropriation laws also reflected the patterns of use created by the gold rush (Littlefield Citation1983). Water was an important feature in California gold mining and while a federal legal framework for navigable waterways was developed, diversions to support mining use were often not from a navigable waterway. Further, mining claims were routinely made on public lands and technically trespass. Additional historical issues complicated the ultimate definition of California water rights law (including arguments related to state’s rights during the civil war) but eventually the federal government codified state and local customs to stabilize mining areas (Littlefield Citation1983; Weil Citation1911). Under this structure water can be a bought and sold commodity, and extractive (not necessarily sustainable) use could be understood as beneficial to achieve other policy goals (Littlefield Citation1983; Bryner and Purcell Citation2003). Facilitators supporting GSP deliberations routinely note that groundwater users often believe their water rights are a property right rather than a (public trust) right of water use.

To further complicate the legal landscape, California also subscribes to a Correlative Rights Doctrine, which creates an obligation for landowners overlying a common groundwater source to share the groundwater. This structure also locks in place strict proportionality, meaning that in times of scarcity everyone must proportionally decrease use. This legal framework is similar to that used to manage riparian rights (the right of a landowner to proportionally access a body of water adjacent to their property) in eastern states (Peck Citation2012). When applied to groundwater water, this doctrine creates a perverse disincentive to practicing conservation that is only moderated by a requirement that water use be beneficial. In fact, the application of correlative rights to groundwater also resembled the pumping practices of the oil, gas, and geothermal industries. In those industries it is understood that proportionally sharing a pooled asset is an extractive endeavor that will eventually deplete the shared resource.

Thus, while California’s water belongs to the public, its use is dictated by the investor and landed classes. Based on extensive work by the United Nations and others, there is a general agreement that commercialization affects different socioeconomic groups differently (rich and poor, landowner and landless farmers, women, and children) under different socio-economic, institutional and policy environments (WWAP (United Nations World Water Assessment Programme) Citation2015).

California water policy largely focused on (the visible) surface water. Under California law groundwater and surface water are separately regulated, even though groundwater and surface water are essentially one resource and sustainable management is dependent on the interactions of the two. This feature of the law is particularly problematic to effectuating cooperation between surface water rights holders (that hold discreet rights) and groundwater users whose assets are proportionally pooled. This bifurcation also resulted in groundwater governance evolving into a complex mixture of local institutions sometimes supported by state resources. So while surface water use is closely monitored, in many cases, groundwater basins remained completely open access with no limits on pumping, a literal wild west.

While the need for a statewide groundwater management frame was long understood, California’s approach continued to be incremental and reactive to specific issues like droughts and local conflicts. This patchwork approach resulted in continued groundwater depletion and conflict and a complex tapestry of existing, autonomous groundwater management institutions and litigated or negotiated agreements, some of which have substantial authority to regulate groundwater pumping. The institutions include special districts created through the legislative process, county ordinances, voluntary groundwater management plans (AB3030/SB193, and adjudicated basins (DWR Citation2015)).

As evidenced by the multiple legal and legislative attempts chronicled by Leahy (Citation2016) to manage groundwater use, prior to passage of SGMA, the concept of a statewide regulatory framework to force sustainable use was often described as a political third rail (Beutler Citation2013). During the preparation of California Water Plan Update 2013, 80 stakeholders with significant groundwater expertise joined together in professionally facilitated sessions, over a two-year period, to draft the sections of the Water Plan Update that addressed groundwater management. This same effort also substantially contributed to California’s Groundwater Update 2013 (DWR Citation2015) and informed the stakeholder deliberations used to develop the SGMA legislation.Footnote1 The group collectively found that offering more than suggested best practices for use by local jurisdictions would likely encounter opposition from influential and powerful interests. Thus, their recommendations for the Water Plan Update were restrained in favor of what they believed may adopted (Beutler Citation2013).

The historic drought of 2012–2016, created a tipping point as severe over pumping resulted in widespread groundwater depletion (Famiglietti Citation2014; Lund et al. Citation2018). Lowered groundwater levels put entire communities at risk as wells went dry and subsidence caused significant infrastructure damage. The magnitude of the crisis created by groundwater practices during the drought, as well as pending public trust law suits, the Water Plan deliberations, and evolving legal theories on the state’s jurisdiction in management of groundwater, altered the political dynamic and eventually allowed for the passage of SGMA (Leahy Citation2016).

Status of SGMA Implementation

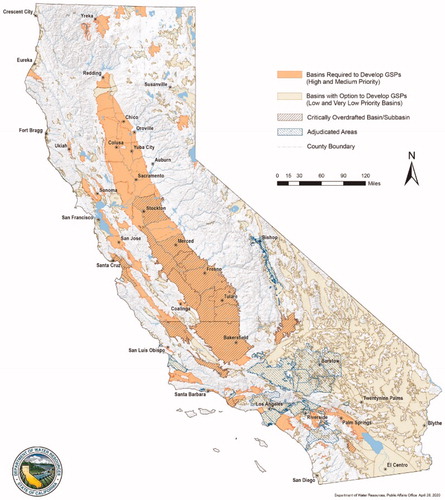

Formally, SGMA is a collection of three pieces of legislation passed by the California Legislature on September 16, 2014: AB1739, SB1168, and SB1319. SGMA required DWR to prioritize the state’s 515 groundwater basins and mandated a timeline for the development of GSAs and GSPs in high and medium priority basins (; DWR Citation2019b). DWR has initiated two rounds of SGMA basin prioritization. The SGMA 2015 Basin Prioritization identified 127 high and medium priority basins requiring GSA development. The SGMA 2019 Basin Prioritization reduced to 94 the number of high and medium priority basins, mostly due to removing adjudicated basins (DWR Citation2019a). GSP development is required for the 94 basins identified in 2019.

GSPs have twenty years to achieve sustainability, defined as avoiding “significant and unreasonable” instances of six undesirable results: long-term declines in groundwater levels, reduction of groundwater storage, land subsidence, seawater intrusion, water quality degradation, and depletions of interconnected surface water. The basic guidelines established by DWR and SWRCB expect local stakeholders to develop institutions and plans that reflect local conditions, including defining and measuring undesirable results, and setting management objectives and thresholds for action (Christian-Smith and Abhold Citation2016).

The public discourse on SGMA often describes it as transformational because it was California’s first attempt at statewide groundwater management. However, as described above, this is not a technically accurate claim. The state had made various forays into statewide policy, including successful legislation establishing incentives for local groundwater planning (e.g., AB3030) and failed legislation containing policy ideas that would inspire aspects of SGMA (Leahy Citation2016). Further, because California is a home-rule state, these previous groundwater management efforts strongly favored local control and thus produced a diverse set of governance arrangements that varied substantially across basins. The existing institutional arrangements and history of interaction has crucial implications for the path of SGMA development (Dennis et al. 2020, this issue). If SGMA had been designed on a clean slate, it may have mirrored other western states and undoubtedly would have looked different. Instead, it was crafted within an existing institutional milieu.

The casual observer, or somebody familiar with theories of common-pool resources, might expect that SGMA would require a single integrated GSA and GSP for each subbasin. In fact, there was considerable political debate about requiring sub-basin level governance structures and the regulations crafted by DWR for implementation of SGMA were also designed to encourage single subbasin GSA and GSP governance structures. However SGMA allows any “eligible agencies” to declare themselves as single-agency GSAs or to join with other eligible agencies to form multi-agency GSAs via a collaborative arrangement such as a memorandum of understanding/agreement or Joint Powers Authority (Méndez-Barrientos, Bostic, and Lubell Citation2019). Eligible agencies are “any local public agency that has water supply, water management, or land use responsibilities within a groundwater basin (SWRCB Citation2017).” Many of these eligible agencies decided to act on their own and form independent GSAs, which many researchers interpret as a strategy to preserve local autonomy or the manifestation of “defensive localism” (Barron and Frug Citation2005). As a result, 264 GSAs were formed by the original June 30, 2017 deadline; 190 of those were single-agency GSA and 74 were multi-agency GSA. Based on a slightly different count of 85 multi-agency GSAs, Méndez-Barrientos, Bostic, and Lubell (Citation2019) report that 3 were formed by a special act of the legislature, 44 were formed by JPA, and 38 by MOA/MOU. Perhaps more importantly from the perspective of basin-level management, Conrad et al. (Citation2018) calculated that 56% of SGMA basins had multiple GSAs, with some basins having as many as 22 agencies. While the tendency to form single-agency GSAs reflects a desire by eligible public agencies to preserve their autonomy in the face of new state authority or a lack of trust in neighboring agencies, the resulting institutional fragmentation necessitates substantial inter-agency coordination to complete and implement GSPs (DuPraw et al. Citation2017).

SGMAs institutional fragmentation translates into the level of GSP plans, which according to regulations accompanying the legislation must be coordinated at the basin level. When a single GSA covers an entire subbasin, that GSA will submit a single, subbasin-wide GSP. In the case of multiple GSAs in a subbasin, they may either join to form a single GSP or each form their own independent GSP that then must form a coordination agreement for plan implementation. By June 2, 2020, there were 46 GSPs submitted by the first deadline of January 31, 2020 with six basins reporting between 3 and 7 GSPs that require a coordination agreement (SWRCB update on SGMA implementation; Stork and Altare Citation2020). Theoretically, institutional fragmentation at the GSA level (i.e.; multiple GSAs per basin) or GSP level (multiple GSPs with coordinated agreement) should reduce the likelihood of cooperation and achieving sustainability. However, this hypothesis remains to be tested with future SGMA research.

Is SGMA going well from an implementation standpoint? This question obviously will provoke diverse perspectives and debate and a complete analysis is beyond the scope of this article. SGMA deadlines have been met and the DWR and SWRCB appear to be providing resources and oversight. There is evidence that the state agencies have learned over time in response to the diverse range of issues that have emerged during the SGMA implementation process. However, the institutional fragmentation that characterizes SGMA is troubling from the perspective of common-pool resource theory, which suggests institutional boundaries should encompass the relevant interdependencies imposed by hydrologic connections within groundwater basins. Furthermore, there are serious questions about representation of disadvantaged communities (Bernacchi et al. Citation2020, Dobbin and Lubell Citation2019), consideration of drinking water quality in GSP (Dobbin et al. Citation2020), the number and distribution of wells expected to become dry even if plans meet minimum thresholds of groundwater depth (Bostic et al. Citation2020; EKI Citation2020), the consideration of drought/climate change in GSPs, and the overall capacity to define and achieve sustainability in the long-run (Miro and Famiglietti Citation2019; Thomas Citation2019). Whether the state has the capacity and political will to credibly enforce SGMA in the case of basins that fail to meet the basic guidelines remains an open question. All this promises that the process of institutional change initiated by SGMA will continue to be a fascinating research topic in the next decades and subject to intense political and policy debate.

Core Research Questions for SGMA

This section briefly introduces each research question and summarizes the main points raised by the collection of papers in this special issue.

Drivers of Cooperation

One way to think about SGMA is that cooperation is the “outcome” or “dependent” variable. A huge branch of social science research, broadly under the rubrics of “collective action” (Hardin Citation1982; Olson Citation1965) or “the evolution of cooperation.” (Axelrod Citation1984; Nowak Citation2006), focuses on the catalysts and barriers to cooperation. The same question motivates the enormous literature on social dilemmas, which consistently identifies communication (Balliet Citation2010), pro-social attitudes (Balliet, Parks, and Joireman Citation2009), leadership (Wilson Citation1995), and sanctioning institutions (Balliet, Mulder, and Van Lange Citation2011) as facilitators of cooperation (see also Fahey and Pralle Citation2016; Lubell Citation2015). Cooperation is also a central question in research on collaborative governance (Armitage Citation2007; Baird et al. Citation2019; Ansell and Gash Citation2007; Emerson, Nabatchi, and Balogh Citation2012), network governance (Provan and Kenis Citation2007), and common-pool resources management (Marshall Citation2013; Ostrom Citation1990). Thus as GSAs formed during the first stage of SGMA implementation, one obvious research question was who coordinated with whom in creating those agencies and why (Milman et al. Citation2018). Questions of cooperation will continue to be important in the coordination and implementation of GSPs.

All the papers in this special issue consider the problem of cooperation. Milman and Kiparsky (2020, this issue) describe “horizontal governance” as the need for institutional collective action among SGMA agencies. Institutional collective action occurs among eligible agencies when they decide to form a collaborative GSA, and then in basins with multiple GSAs that must coordinate in the development of GSPs. An intriguing question that is being researched in connection with SGMA implementation is how inter-agency collaboration functions when it is mandated rather than being a voluntary arrangement between agencies. This has been a topic of inquiry in studies of other settings besides water management (e.g., Brummel, Nelson, and Jakes Citation2012; Caruson and MacManus Citation2006; Cheng Citation2006; Lance, Georgiadou, and Bregt Citation2009; Schafer Citation2016). The article by Milman and Kiparsky examines what “horizontal governance” means in this context.

These formal agencies must also employ strategies of “network governance” for engaging the broader range of stakeholders. This includes disadvantaged communities, environmental groups and other non-governmental agencies, and appropriators that are outside the jurisdictional boundaries of the GSA but still pump water from the basin. SGMA uses the term “interested parties” to describe this network of stakeholders, some of whom are represented on GSA boards or as members of advisory committees.

Participation in SGMA decision-making is one form of cooperation in the context of collective decision-making. Dobbin et al. (Citation2020, this issue) finds that participation by disadvantaged communities is driven by a desire to maintain their access to groundwater and preserve their decision-making autonomy. However, disadvantaged communities face barriers to participation that are not experienced by larger and wealthier organizations. In comparison, Méndez-Barrientos et al. (Citation2020, this issue) find that farmer participation is not clearly driven by perceptions of drought risk or perceived decline in groundwater availability, but rather by their connections to preexisting “hydro-social networks” and a resistance to state authority. Hammond-Wagner and Niles (Citation2020, this issue) similarly find that perceptions of fairness were important to farmer participation in SGMA implementation. These initial qualitative studies provide some intriguing clues about drivers of participation, and research across more basins and users is needed to confirm their generalizability.

Institutional Diversity in SGMA

In the latter stages of her career, Elinor Ostrom (Citation2005, Citation2009) highlighted the diversity of institutional arrangements that humans design in response to the diverse social-ecological contexts they are facing (Ostrom Citation2009). The idea of institutional fit posits that institutions that are customized to local conditions will reduce transaction costs of establishing cooperation and sustaining it over time (Ayres, Edwards, and Libecap Citation2018; Epstein et al. Citation2015; Guerrero et al. Citation2015; Kiparsky et al. Citation2017).

Ostrom (Citation1990) distinguishes between “collective-choice rules” that govern decision-making, versus “operational rules” that structure the property rights regarding resource use. For SGMA, collective-choice rules are reflected in the structure of GSAs and the planning process for GSPs. Operational rules would be the specific management actions included in GSPs to achieve sustainability. Institutional diversity is a hallmark of SGMA due to its delegation of the crafting of institutional rules at the local level – GSAs have been composed of cities, county governments, and a wide range of water districts, either acting alone or in various combinations. While local control potentially increases institutional fit, it can increase the difficulty of establishing and enforcing statewide standards that apply to all GSAs and GSPs.

It is challenging to analyze how institutional diversity relates to policy effectiveness because no single institutional arrangement will be a panacea in all basins (Ostrom Citation2007). The first step is observing the dimensions along which institutions vary and linking this to both policy outputs and resource outcomes. SGMA institutions have at least five dimensions of institutional diversity: formal coordination mechanisms, structures of representation, timing of institutional development, the specific rules and practices for achieving groundwater sustainability, and linkages to other water management processes. For example, collaborative GSAs are more likely to incorporate formal representation of disadvantaged communities (Dobbin and Lubell Citation2019).

Dobbin et al. (Citation2020, this issue) describes how disadvantaged communities experience institutional diversity in both informal norms and formal rules of representation. Some GSAs only involve disadvantaged communities through more general methods of outreach and engagement that build informal networks of participation, rather than formal representation via a “seat at the table” such as board or committee membership. Dobbin et al. (Citation2020, this issue) finds that informal participation may involve more frequent interaction than formal representation, either via advisory committee membership or voting seats on GSA boards. The relationship between informal social norms and formal rules in SGMA is a promising albeit challenging research topic given the difficulty of observing informal norms relative to formal institutional rules. The experience and impact of disadvantaged community participation was similarly diverse in another statewide program that preceded SGMA, known as Integrated Regional Water Management (Balazs and Lubell Citation2014; Hui, Ulibarri, and Cain Citation2020; Lubell and Lippert Citation2011).

Institutional diversity also manifests in the water management strategies (operational rules) being incorporated into GSPs. Langridge and Van Schmidt (2020; this issue) describe how the operational rules employed by adjudicated basins and different GSAs result in different approaches to managing groundwater under climate change and drought. They illuminate how SGMA has altered these approaches including innovations in supply management such as the use of flood flows for managed aquifer recharge and the establishment of groundwater storage drought reserves as well as an increased emphasis on reducing demand through the regulation of pumping. The mix of rules is related to variables that include hydrological structure of the basin, patterns of precipitation, types of water uses, potential conjunctive use of surface and groundwater, and the structure of storage/conveyance infrastructure. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the first set of GSPs that were submitted in 2019–2020 tended to feature supply-augmentation strategies more than demand-reduction ones.

Equity and Environmental Justice

SGMA emerged at a time of increasing concern about equity and environmental justice in California. In 2012, California passed the Human Right to Water (AB685) making it the first state in the country to statutorily recognize that “every human being has the right to safe, clean, affordable, and accessible water adequate for human consumption, cooking, and sanitary purposes.” AB685 places an obligation on state agencies to consider the human right to water in relevant policies and programs. California Water Plan Update 2018 (DWR Citation2019a) includes recommendations to “empower California’s under-represented or vulnerable communities” and more recently on July 28, 2020, Governor Gavin Newsom released a “Water Resilience Portfolio” that recognizes issues faced by disadvantaged communities in several sections.

California uses a socio-economic definition of disadvantaged communities as those with an annual median household income less than 80 percent of the state's annual median household income (Dobbin and Lubell Citation2019). Many disadvantaged communities are also predominantly composed of people of color, especially Latino communities in California’s Central Valley. Existing research has clearly demonstrated that disadvantaged, Latino communities are disproportionately vulnerable to nitrate (Balazs et al. Citation2011) and arsenic pollution (Balazs et al. Citation2012) and water scarcity during drought (Pauloo et al. Citation2019), and less likely to participate in and benefit from water management programs (Balazs and Lubell Citation2014; Lubell and Lippert Citation2011). These patterns of distributional and procedural inequity are rooted in a complex mix of variables related the natural system, built environment, and socio-political context (Balazs et al. Citation2011), including structural racism and historical policies of segregation that influence the extent to which different types of water users are represented by water management institutions (Pannu Citation2012).

SGMA requires GSAs document their stakeholder engagement strategies and to consider the interests of all beneficial uses and users of groundwater in a basin, including Native American tribes and disadvantaged communities. But there is no specific statutory language about how to include disadvantaged communities, which has delegated the issue to agency guidance documents. As result there is a great deal of variance in how GSAs incorporate disadvantaged communities into their governance structure and the effectiveness of their engagement strategies. Dobbin and Lubell (Citation2019) find that only 16% of DACs are represented on GSAs via voting seats or some other formal mechanism with representation more likely for larger and wealthier communities in collaborative GSAs. GSPs also exhibit considerable variation in their attention to drinking water quality in the context of groundwater management, which is one of the most important concerns for DACs (Dobbin et al. Citation2020; Moran and Belin Citation2019).

The papers in this issue further document the barriers to SMGA participation faced by disadvantaged communities and the small water systems that often serve them. Dobbin et al. (Citation2020, this issue) documents how small water systems lack the financial and human resources to access SGMA decision forums, including in some cases GSAs requiring a financial contribution to have a voting seat. In the face of resource scarcity, DACs may face tradeoffs between the long-term investment in sustainable groundwater management versus infrastructure investments for immediate, short-term needs. Even when at the table, small water systems report that SGMA faces some of the same environmental justice problems that occur throughout water management, such as a lack of influence due to knowledge and resource disparities and lack of transparency.

But the special issue papers also document an aspect of equity that is not typically considered: how farmers participate in and perceive SGMA. Agricultural users are considered among the most powerful water interests in California, with their influence based on large farms, well-organized industry groups, senior water rights, strong political networks, and established local institutions like agricultural water districts. But there are also many small farmers with land outside of water district boundaries, who are often from immigrant communities, operating exclusively on shallow groundwater wells (Mountjoy Citation1996; Sowerwine, Getz, and Peluso Citation2015). Méndez-Barrientos et al. (Citation2020 , this issue) demonstrate that SMGA participation is less likely for small farmers who are independent groundwater users that are not networked to existing agricultural water districts.

Relating to distributional equity, Hammond Wagner and Niles (Citation2020, this issue) analyze how farmers perceive the fairness of four different principles of water allocation in GSPs: equal per unit of overlying land, set at historical use, according to variable crop requirements, and proportional to agricultural output. While they found a strong preference among all farmers for overlaying land allocations, that perception was driven more by their experience with SGMA, including perceptions of the overall SGMA process as “fair,” rather than variables related to their self-interests. If stakeholders anchor distributional fairness perceptions in their experience with the SGMA process, there may be an opportunity to craft higher levels of agreement on the preferred allocation strategy than may be expected given diverse self-interests.

Role of the State

SGMA is an example of a multi-level system with a diverse set of local basins and agencies that must respond to a statewide mandate with policy oversight from state agencies, with state-level political discussion about how the state should shape local policy implementation. This multi-level arrangement, which is typical of all environmental policy, highlights at least three important roles for the state. First, the state needs to provide financial, human, and information resources to the local level to reduce transaction costs (Clark and Whitford Citation2011). Second, the state needs to provide oversight to ensure local institutions meet some basic standards, such as accounting for the interests of disadvantaged communities and appropriately defining sustainability (Gunningham Citation2009). Third, the state must collectively learn over time about how to adjust resources and oversight in response to the lessons learned from SGMA implementation in different basins (Heikkila and Gerlak Citation2013). All of these roles are considered in the concept of “state-reinforced self-governance” (DeCaro et al. Citation2017; Sarker Citation2013) and illustrate the classic tension between centralization and decentralization, where central authorities establish statewide goals and standards but allow local actors to craft their own rules.

Dennis et al. (2020, this issue) argue that previous groundwater management policies impose path-dependent constraints on SGMA governance. From its early history, California was a home rule state that elected to exempt groundwater from state-level oversight. Consequently, the first phase of state involvement was enabling the development local institutions by providing information, financial resources, and legislative backing. The second phase incentivized local groundwater management, especially with Assembly Bill 3030 (passed in 1991) that provided funding incentives to develop groundwater management plans. While AB3030 plans identified objectives and monitored groundwater basins, they did not contain any real power to regulate pumping. SGMA represents the most recent phase in the evolution of groundwater management, mandating stronger local institutions, but still deferring to local control.

Milman and Kiparsky (2020, this issue) describe the role of the state in the state-local relationship in terms of “vertical governance” with an emphasis on policy implementation. Given the variety of local basins contexts, and the political and practical challenges to writing detailed legislation for each basin, SGMA contains ambiguous language on the exact structure of GSA organization and GSP content including measurements of sustainability. DWR provides guidance and resources for the development of the local plans, and the SWRCB will enforce noncompliance. Effectively implementing SGMA will thus require substantial learning at the state level, as they review whether the structure of the GSAs and the content of GSPs will meet SGMA goals. For example, we know that only 28% of GSAs with DACs in their boundaries include formal representation for disadvantaged communities (Dobbin and Lubell Citation2019) and 56% of GSPs set minimum thresholds for water quality constituents (Dobbin et al. Citation2020). In evaluating SGMA, the state may need to set more explicit standards for such decisions but will need to reconcile the preferences of different stakeholders. The state may also have to reconcile the legal issues raised by GSA authority to restrict groundwater pumping, while SGMA also promises to preserve pumpers’ groundwater rights.

Facilitation and Leadership

Theories of collective action and policy change argue that leadership and political entrepreneurs reduce transaction costs and accelerate processes of innovation and learning (Feiock and Carr Citation2001; Schneider, Teske, and Mintrom Citation1995). Previous research has identified leadership as an important ingredient in all forms of “concurrent” governance considered by Milman and Kiparsky (2020, this issue). Leadership strengthens vertical governance by translating SGMA requirements into local GSAs and GSPs and communicating about best practices across the state. Leadership is needed for horizontal governance and the institutional collective action required to coordinate among water users within a basin. Incorporating other stakeholders through broader network governance also requires leadership (Imperial et al. Citation2016), both within core GSA organizations and among different types of communities who wish to participate.

Leadership comes from two main sources in SGMA. First, DWR contracted with a facilitation team that collaborates with the key actors and technical consultants to help organize a diverse set of local professionals to work within basins. Some basins have hired facilitators independently; that is, not members of the DWR sponsored team. Other basins have not contracted outside facilitation, but rather rely on internal leadership perhaps from staff in an eligible agency. SGMA facilitators who apply the best-practices from the professional field of conflict resolution may be more successful in building cooperation (Coglianese Citation1997; Emerson et al. Citation2009; O’Leary and Bingham Citation2003).

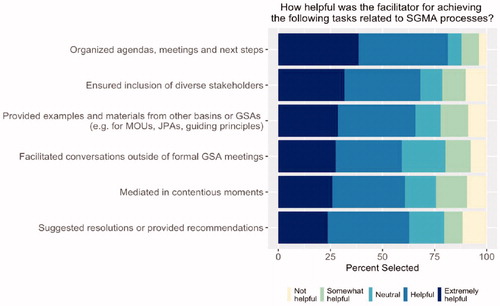

Some limited evidence on facilitation comes from the UC Davis SGMA survey (Méndez-Barrientos, Bostic, and Lubell Citation2019). shows how stakeholders perceived the helpfulness of facilitators for tasks related to the SGMA process. Facilitators were viewed as helpful overall, with evidence that they reduced the transaction costs of involved with all three dimensions of concurrent governance: organizing meetings (horizontal), including diverse stakeholders (network), and diffusing best practices at the statewide level(vertical). This is consistent with other research on the valuable contribution that funding for coordinators played in collaborative planning processes (Koontz and Newig Citation2014; Olvera-Garcia and Neil Citation2020).

Second, leadership also emerges within GSAs and throughout the broad networks of involved stakeholders because developing new groundwater institutions can require politically risky decisions and changes in standard operating procedures. Leadership is needed at the state level to change agency procedures and maintain credible oversight and enforcement. Among disadvantaged communities, leadership can build a diverse network of environmental justice organizations to participate in SGMA as a collective community. Non-governmental organizations and small farmers also benefit from leadership that will coordinate their participate in SGMA processes. It is not clear from existing research the conditions under which such political entrepreneurs are expected to emerge, or what the role of individual attitudes such as “public service motivation” may play (Crewson Citation1997; Perry Citation1997).

Hammond-Wagner and Niles (2020, this issue) is the one paper in this special issue that does provide some explicit lessons about leadership. Farmers reported a clear preference for dispute resolution to occur within GSAs or local arbitration, rather than appealing to higher levels of government such as counties, state agencies, or courts. The preferences for GSA dispute resolution was even stronger among respondents who had an overall positive experience with GSA participation. This reiterates the importance of providing resources to support leadership and conflict resolution at the local level. However, more research is needed to see if this preference for local dispute resolution is shared by all stakeholders. For example, environmental justice advocates often appeal to state agencies to increase the stringency of GSA and GSP evaluation standards if they feel excluded from local processes.

Conclusion

Based on the papers in this special issue, what are the lessons learned from the SGMA experience to date? Cooperation must evolve in three dimensions: horizontally, vertically, and across the broader SGMA stakeholder network. Transaction costs reduce the likelihood of cooperation and create higher barriers to participation among some water user groups. The diversity of institutional arrangements and hydrological conditions that exists across GSAs and GSPs affects the nature of political representation as well as the portfolio of water management strategies that might be adopted to pursue sustainability. All of this reflects enduring environmental injustices in California, with disadvantaged groups facing higher barriers to participation and influence than agricultural and other interests with preexisting connections to established water management institutions. SGMA also reveals overlooked aspects of environmental justice such as how small farmers and independent groundwater users can be represented and provides the State itself with some leverage to ensure that equity and justice considerations are addressed. Leadership from facilitators and other stakeholder organizations is a crucial resource for reducing transaction costs.

Taken together, SGMA illustrates the enduring relevance of the adage “all politics is local.” This is no surprise given the path-dependent history of local water institutional development in California, SGMA’s explicit delegation of authority to local actors, and how the local configuration of social-ecological variables influences the benefits and transaction costs of cooperation. Considerations of institutional fit drive the diversity of formal and informal institutional arrangements that have emerged across basins thus far and how they will change in the future. Some basins have more disadvantaged communities and a longer history of environmental injustice, and some environmental justice communities face higher barriers to participation than others. Some basins are fortunate to have effective facilitation and the emergence of political entrepreneurs and leaders. The state must deliver resources to the local level to reduce transaction costs, learn from local level information, and hold basins accountable to statewide standards. It is this variance in the capacity for collective action across basins that provides such a rich opportunity for environmental governance research.

Capitalizing on the research opportunity afforded by SGMA requires more effort along with innovations in research design. Given SGMA’s twenty-year time horizon, longitudinal research designs are needed to analyze change. Such research will benefit from co-production with stakeholders and greater integration between the social and biophysical sciences, for example to link governance indicators to biophysical indicators of sustainability. We need investment in quantitative social science research to better generalize the insights provided by the qualitative research that is represented in many of the papers in this issue. This does not mean discontinuing qualitative research that provides deeper analysis of the social processes driving collective action in SGMA. But research in more basins provides a comparative perspective that reflects the diversity of social-ecological systems in California. We need more information about how different types of water users are experiencing SGMA: disadvantaged communities, farmers, agency leaders/staff, facilitators, and others. Achieving such a spatially comprehensive, long-term, co-produced, and integrated research endeavor is not easy. It requires research groups to solve their own collective-action problems and a high-level of investment from government and foundation research funds. Let’s get to it.

Notes

1 The Water Plan stakeholder group included many individuals that helped to draft SGMA language and/or served as technical experts and advisors to the key decision makers that negotiated final bill language. A full list of group members may be found in the Acknowledgements section of the California Water Plan Update 2013.

References

- Alley, W. M., L. Beutler, M. E. Campana, S. B. Megdal, and J. C. Tracy. 2016. Groundwater visibility: The missing link. Ground Water 54 (6):758–61. doi:10.1111/gwat.12466.

- Ansell, C., and A. Gash. 2007. Collaborative governance in theory and practice. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 18 (4):543–71. doi:10.1093/jopart/mum032.

- Armitage, D. 2007. Governance and the commons in a multi-level world. International Journal of the Commons 2 (1):7–32. doi:10.18352/ijc.28.

- Axelrod, R. 1984. The evolution of cooperation. New York: Basic Books.

- Ayres, A. B., E. C. Edwards, and G. D. Libecap. 2018. How transaction costs obstruct collective action: The case of California’s groundwater. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management 91:46–65. doi:10.1016/j.jeem.2018.07.001.

- Baird, J., R. Plummer, L. Schultz, D. Armitage, and Ö. Bodin. 2019. How does socio-institutional diversity affect collaborative governance of social-ecological systems in practice? Environmental Management 63 (2):200–14. doi:10.1007/s00267-018-1123-5.

- Balazs, C. L., and M. Lubell. 2014. Social learning in an environmental justice context: A case study of integrated regional water management. Water Policy 16 (S2):97–120. doi:10.2166/wp.2014.101.

- Balazs, C. L., R. Morello-Frosch, A. E. Hubbard, and I. Ray. 2012. Environmental justice implications of arsenic contamination in California’s San Joaquin Valley: A cross-sectional, cluster-design examining exposure and compliance in community drinking water systems. Environmental Health 11 (1):84. doi:10.1186/1476-069X-11-84.

- Balazs, C., R. Morello-Frosch, A. Hubbard, and I. Ray. 2011. Social disparities in nitrate-contaminated drinking water in California’s San Joaquin Valley. Environmental Health Perspectives 119 (9):1272–8. doi:10.1289/ehp.1002878.

- Balliet, D. 2010. Communication and cooperation in social dilemmas: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Conflict Resolution 54 (1):39–57. doi:10.1177/0022002709352443.

- Balliet, D., L. B. Mulder, and P. A. Van Lange. 2011. Reward, punishment, and cooperation: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin 137 (4):594–615. doi:10.1037/a0023489.

- Balliet, D., C. Parks, and J. Joireman. 2009. Social value orientation and cooperation in social dilemmas: A meta-analysis. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations 12 (4):533–47. doi:10.1177/1368430209105040.

- Barron, D. J., and G. E. Frug. 2005. Defensive localism: View of the field from the field. Journal of Law & Politics 21 (3):261–92.

- Bernacchi, L. A., A. S. Fernandez-Bou, J. H. Viers, J. Valero-Fandino, and J. Medellín-Azuara. 2020. A glass half empty: Limited voices, limited groundwater security for California. The Science of the Total Environment 738:139529. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.139529.

- Beutler, L. 2013. Personal accounts based on interviews with group members prior to development of the California Water Plan Update Process Guide, Vol. 4, 2015.

- Blomquist, W. A., E. Schlager, and T. Heikkila. 2004. Common waters, diverging streams: Linking institutions to water management in Arizona, California, and Colorado. Washington, DC: Resources for the Future.

- Bostic, D., K. Dobbin, R. Pauloo, J. Mendoza, M. Kuo, and J. London. 2020. Sustainable for whom? The impact of groundwater sustainability plans on domestic wells. UC Davis Center for Regional Change. https://regionalchange.ucdavis.edu/publication/sustainable-whom-impact-groundwater-sustainability-plans-domestic-wells

- Brown, A., R. Langridge, and K. Rudestam. 2016. Coming to the table: Collaborative governance and groundwater decision-making in coastal. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 59 (12):2163–78. doi:10.1080/09640568.2015.1130690.

- Brummel, R. F., K. C. Nelson, and P. J. Jakes. 2012. Burning through organizational boundaries? Examining inter-organizational communication networks in policy-mandated collaborative bushfire planning groups. Global Environmental Change 22 (2):516–28. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2011.12.004.

- Bryner, G., and E. Purcell. 2003. Groundwater law sourcebook of the western United States. Natural Resources Law Center, University of Colorado at Boulder 6:2, 14–20.

- Caruson, K., and S. A. MacManus. 2006. Mandates and management challenges in the trenches: An intergovernmental perspective on homeland security. Public Administration Review 66 (4):522–36. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6210.2006.00613.x.

- Cheng, A. S. 2006. Build it and they will come? Mandating collaboration in public lands planning and management. Natural Resources Journal 46 (4):841–58.

- Christian-Smith, J., and K. Abhold. 2016. Measuring what matters: Setting measurable objectives to achieve sustainable groundwater management in California. Cambridge, MA: Union of Concerned Scientists

- Clark, B. Y., and A. B. Whitford. 2011. Does more federal environmental funding increase or decrease states’ efforts? Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 30 (1):136–52. doi:10.1002/pam.20547.

- Coglianese, C. 1997. Assessing consensus: The promise and performance of negotiated rulemaking. Duke: Duke University Law Journal.

- Conrad, E., T. Moran, M. DuPraw, D. Ceppos, J. Martinez, and W. Blomquist. 2018. Diverse stakeholders create collaborative, multilevel basin governance for groundwater sustainability. California Agriculture 72 (1):44–53. doi:10.3733/ca.2018a0002.

- Crewson, P. E. 1997. Public-service motivation: Building empirical evidence of incidence and effect. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 7 (4):499–518. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.jpart.a024363.

- Dawes, R. M., and D. M. Messick. 2000. Social dilemmas. International Journal of Psychology 35 (2):111–6. doi:10.1080/002075900399402.

- DeCaro, D. A., B. C. Chaffin, E. Schlager, A. S. Garmestani, and J. B. Ruhl. 2017. Legal and institutional foundations of adaptive environmental governance. Ecology and Society: A Journal of Integrative Science for Resilience and Sustainability 22 (1):1–32. doi:10.5751/ES-09036-220132.

- Dennis, E. M., W. Blomquist, A. Milman, and T. Moran. 2020. Path dependence, evolution of a mandate and the road to statewide sustainable groundwater management. Society & Natural Resources (2020): 1–13.

- Department of Water Resources (DWR). 2003. California’s Groundwater Bulletin 118 Update 2003. https://water.ca.gov/Programs/Groundwater-Management/Bulletin-118

- Department of Water Resources (DWR). 2015. California’s Groundwater Update 2013. https://water.ca.gov/-/media/DWR-Website/Web-Pages/Programs/Groundwater-Management/Data-and-Tools/Files/Statewide-Reports/California-Groundwater-Update-2013/California-Groundwater-Update-2013—Statewide.pdf

- Department of Water Resources (DWR). 2019a. California Water Plan Update 2018. https://water.ca.gov/-/media/DWR-Website/Web-Pages/Programs/California-Water-Plan/Docs/Update2018/Final/California-Water-Plan-Update-2018.pdf

- Department of Water Resources (DWR). 2019b. Sustainable Groundwater Management Act 2019 Basin Prioritization. https://water.ca.gov/Programs/Groundwater-Management/Basin-Prioritization

- Dobbin, K. B., and M. Lubell. 2019. Collaborative governance and environmental justice: Disadvantaged community representation in California sustainable groundwater management. Policy Studies Journal doi:10.1111/psj.12375.

- Dobbin, K., D. Bostic, M. Kuo, and J. Mendoza. 2020. SGMA and the human right to water: To What extent do submitted groundwater sustainability plans address drinking water uses and issues? UC Davis Center for Environmental Policy and Behavior. https://environmentalpolicy.ucdavis.edu/sites/g/files/dgvnsk6866/files/files/person/Final%20Report%20-%20English.pdf

- DuPraw, M. E., S. D. Vittorio, D. Ceppos, M. D. Wylie, M. Kopell, S. Lucero, T. Carlone, M. Meyer, and S. Horii. 2017. Groundwater sustainability plans. The Water Report. Issue 162:1–11.

- EKI: Environment and Water. 2020. Estimated numbers of Californians Reliant on domestic wells impacted as a result of the sustainability criteria defined in selected San Joaquin Valley groundwater sustainability plans and associated costs to mitigate those impacts. White paper prepared for the California Water Foundation. https://waterfdn.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Domestic-Well-Impacts_White-Paper_2020-04-09.pdf

- Emerson, K., T. Nabatchi, and S. Balogh. 2012. An integrative framework for collaborative governance. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 22 (1):1–29. doi:10.1093/jopart/mur011.

- Emerson, K., P. J. Orr, D. L. Keyes, and K. M. McKnight. 2009. Environmental conflict resolution: Evaluating performance outcomes and contributing factors. Conflict Resolution Quarterly 27 (1):27–64. doi:10.1002/crq.247.

- Epstein, G., J. Pittman, S. M. Alexander, S. Berdej, T. Dyck, U. Kreitmair, K. J. Rathwell, S. Villamayor-Tomas, J. Vogt, and D. Armitage. 2015. Institutional fit and the sustainability of social–ecological systems. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability 14 (0):34–40. doi:10.1016/j.cosust.2015.03.005.

- Fahey, B. K., and S. B. Pralle. 2016. Governing complexity: Recent developments in environmental politics and policy. Policy Studies Journal 44 (S1):S28–S49. doi:10.1111/psj.12159.

- Famiglietti, J. S. 2014. The global groundwater crisis. Nature Climate Change 4 (11):945–8. doi:10.1038/nclimate2425.

- Feiock, R., and J. B. Carr. 2001. Incentives, entrepreneurs, and boundary change: A collective action framework. Urban Affairs Review 36 (3):382–405. doi:10.1177/10780870122184902.

- Guerrero, A. M., Ö. Bodin, R. R. J. McAllister, and K. A. Wilson. 2015. Achieving social-ecological fit through bottom-up collaborative governance: An empirical investigation. Ecology and Society 20 (4):41. doi:10.5751/ES-08035-200441.

- Gunningham, N. 2009. The new collaborative environmental governance: The localization of regulation. Journal of Law and Society 36 (1):145–66. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6478.2009.00461.x.

- Hamilton, M. 2018. Understanding what shapes varying perceptions of the procedural fairness of transboundary environmental decision-making processes. Ecology and Society 23 (4):48. doi:10.5751/ES-10625-230448.

- Hammond, W., R. Courtney,, and, M. T. Niles. 2020. What is fair in groundwater allocation? Distributive and procedural fairness perceptions of California’s Sustainable Groundwater Management Act.” Society & Natural Resources (2020): 1–22.

- Hardin, R. 1982. Collective action. Washington, DC: Resources for the Future.

- Heikkila, T., and A. K. Gerlak. 2013. Building a conceptual approach to collective learning: Lessons for public policy scholars. Policy Studies Journal 41 (3):484–512. doi:10.1111/psj.12026.

- Hui, I., N. Ulibarri, and B. Cain. 2020. Patterns of participation and representation in a regional water collaboration. Policy Studies Journal 48 (3):754–81. doi:10.1111/psj.12266.

- Imperial, M. T., S. Ospina, E. Johnston, R. O'Leary, J. Thomsen, P. Williams, and S. Johnson. 2016. Understanding leadership in a world of shared problems: Advancing network governance in large landscape conservation. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 14 (3):126–34. doi:10.1002/fee.1248.

- Kiparsky, M., A. Milman, D. Owen, and A. T. Fisher. 2017. The importance of institutional design for distributed local-level governance of groundwater. Water 9 (10):755. doi:10.3390/w9100755.

- Kollock, P. 1998. Social dilemmas: The anatomy of cooperation. Annual Review of Sociology 24 (1):183–214. doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.24.1.183.

- Komorita, S. S. 2019. Social dilemmas. New York: Routledge.

- Koontz, T. M., and J. Newig. 2014. From planning to implementation: Top-down and bottom-up approaches for collaborative watershed management. Policy Studies Journal 42 (3):416–42. doi:10.1111/psj.12067.

- Lance, K. T., Y. Georgiadou, and A. K. Bregt. 2009. Cross-agency coordination in the shadow of hierarchy: ‘Joining up’ government geospatial information systems. International Journal of Geographical Information Science 23 (2):249–69. doi:10.1080/13658810801909615.

- Langridge, R. , and N. D. Van Schmidt. 2020. Groundwater and drought resilience in the SGMA Era. Society & Natural Resources (2020): 1–12.

- Leahy, T. C. 2016. Desperate times call for sensible measures: The making of the California Sustainable Groundwater Management Act. Golden Gate University Environmental Law Journal 9:5.

- Littlefield, D. R. 1983. Water rights during the California gold rush: Conflicts over economic points of view. The Western Historical Quarterly 14 (4):415–34. Volume Issue October Pages. doi:10.2307/968199.

- Lubell, M. 2015. Collaborative partnerships in complex institutional systems. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability 12:41–7. doi:10.1016/j.cosust.2014.08.011.

- Lubell, M., and L. Lippert. 2011. Integrated regional water management: A study of collaboration or water politics-as-usual in California, USA. International Review of Administrative Sciences 77 (1):76–100. doi:10.1177/0020852310388367.

- Lund, J., J. Medellin-Azuara, J. Durand, and K. Stone. 2018. Lessons from California’s 2012–2016 drought. Journal of Water Resources Planning and Management 144 (10):04018067. doi:10.1061/(ASCE)WR.1943-5452.0000984.

- Marshall, G. R. 2013. Transaction costs, collective action and adaptation in managing complex social-ecological systems. Ecological Economics 88:185–94. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2012.12.030.

- Méndez-Barrientos, L., D. Bostic, and M. Lubell. 2019. Implementing SGMA: Results from a stakeholder survey. https://environmentalpolicy.ucdavis.edu/sites/g/files/dgvnsk6866/files/inline-files/SGMA%20Survey%20report_CEPB.pdf

- Milman, A., and M. Kiparsky. 2020. Concurrent governance processes of California’s Sustainable Groundwater Management Act. Society & Natural Resources (2020): 1–12.

- Milman, A., L. Galindo, W. Blomquist, and E. Conrad. 2018. Establishment of agencies for local groundwater governance under California’s Sustainable Groundwater Management Act. Water Alternatives 11 (3):458–80.

- Miro, M. E., and J. S. Famiglietti. 2019. A framework for quantifying sustainable yield and California’s Sustainable Groundwater Management Act. Sustainable Water Resources Management 5 (3):1165–77. doi:10.1007/s40899-018-0283-z.

- Méndez-Barrientos, L. E., A. DeVincentis, J. Rudnick, R. Dahlquist-Willard, B. Lowry, and, K. Gould. 2020. Farmer participation and institutional capture in common-pool resource governance reforms. The case of groundwater management in California. Society & Natural Resources (2020): 1–22.

- Moe, T. 2005. Power and political institutions. Perspectives on Politics 3 (02):217–33. doi:10.1017/S1537592705050176.

- Moran, T., and A. Belin. 2019. A guide to water quality requirements under the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act. Stanford Water in the West. https://stacks.stanford.edu/file/druid:dw122nb4780/A%20Guide%20to%20Water%20Quality%20Requirements%20under%20SGMA.pdf

- Morrison, T. H., W. N. Adger, K. Brown, M. C. Lemos, D. Huitema, J. Phelps, L. Evans, P. Cohen, A. M. Song, R. Turner, et al. 2019. The black box of power in polycentric environmental governance. Global Environmental Change 57:101934. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2019.101934.

- Mountjoy, D. C. 1996. Ethnic diversity and the patterned adoption of soil conservation in the strawberry hills of Monterey, California. Society & Natural Resources 9 (4):339–57. doi:10.1080/08941929609380979.

- Nowak, M. A. 2006. Five rules for the evolution of cooperation. Science 314 (5805):1560–3. doi:10.1126/science.1133755.

- O’Leary, R., and L. B. Bingham. 2003. The promise and performance of environmental conflict resolution. Washington, DC: Resources for the Future.

- Olson, M. 1965. The logic of collective action. Boston: Harvard University Press.

- Olvera-Garcia, J., and S. Neil. 2020. Examining how collaborative governance facilitates the implementation of natural resource planning policies: A water planning policy case from the great barrier reef. Environmental Policy and Governance 30 (3):115–27. doi:10.1002/eet.1875.

- Ostrom, E. 1990. Governing the commons. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Ostrom, E. 2005. Understanding institutional diversity. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Ostrom, E. 2007. A diagnostic approach for going beyond panaceas. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 104 (39):15181–7. doi:10.1073/pnas.0702288104.

- Ostrom, E. 2009. A general framework for analyzing sustainability of social-ecological systems. Science 325 (5939):419–22. doi:10.1126/science.1172133.

- Pannu, C. 2012. Drinking water and exclusion: A case study from California’s Central Valley. California Law Review 100 (1):223–68.

- Pauloo, R., H. Dahlke, G. Fogg, H. Guillon, A. Fencl, and A. Escriva-Bou. 2019. Domestic well vulnerability to drought duration and unsustainable groundwater management in California's Central Valley, v2, UC Davis, Dataset, doi:10.25338/B8Q31D.

- Peck, J. C. 2012. The evolving nature of water rights as property rights in the United States. University of Kansas School of Law, paper reprinted by Canadian Bar Association (http://www.cba.org/cba/cle/PDF/ENV11_Peck_Paper.pdf, referenced August 31, 2020).

- Perry, J. L. 1997. Antecedents of public service motivation. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 7 (2):181–97. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.jpart.a024345.

- Provan, K. G., and P. Kenis. 2007. Modes of network governance: Structure, management, and effectiveness. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 18 (2):229–52. doi:10.1093/jopart/mum015.

- Purdy, J. M. 2012. A framework for assessing power in Collaborative governance processes. Public Administration Review 72 (3):409–17. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6210.2011.02525.x.

- Sarker, A. 2013. The role of state-reinforced self-governance in averting a tragedy of the irrigation commons in Japan. Public Administration 91 (3):727–43.

- Schafer, J. G. 2016. Mandates to coordinate: The case of the Southern Nevada Public Lands Management Act. Public Performance & Management Review 40 (1):23–47. doi:10.1080/15309576.2016.1177555.

- Schlager, E., W. Blomquist, and S. Y. Tang. 1994. Mobile flows, storage, and self-organized institutions for governing common-pool resources. Land Economics 70 (3):294–317. doi:10.2307/3146531.

- Schneider, M., P. Teske, and M. Mintrom. 1995. Public entrepreneurs: Agents for change in American government. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Smith, P. D., and M. H. McDonough. 2001. Beyond public transporation: Fairness in natural resource decision making. Society and Natural Resources 14 (3):239–49. doi:10.1080/089419201750111056.

- Sowerwine, J., C. Getz, and N. Peluso. 2015. The myth of the protected worker: Southeast Asian micro-farmers in California agriculture. Agriculture and Human Values 32 (4):579–95. doi:10.1007/s10460-014-9578-3.

- State Water Resources Control Board (SWRCB). 2017. Frequently asked questions on groundwater sustainability agencies. https://www.waterboards.ca.gov/water_issues//programs/gmp/docs/eligbility/gsa_faq.pdf

- Stork, N., and C. Altare. 2020. State water resources control board: Update on SGMA implementation. https://mavensnotebook.com/2020/06/10/state-water-board-update-on-sgma-implementation-2/

- Thomas, B. F. 2019. Sustainability indices to evaluate groundwater adaptive management: A case study in California for the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act. Hydrogeology Journal 27 (1):239–48. doi:10.1007/s10040-018-1863-6.

- Tyler, T. R., and S. L. Blader. 2000. Cooperation in groups: Procedural justice, social identity, and behavioral engagement. New York: Psychology Press.

- Weil, S. C. 1911. Water rights in the Western States. 3rd ed., 85–117. San Francisco: Bancroft-Whitney Company.

- Wilson, R. K. 1995. “Say it ain’t so, Uncle Joe,” leadership, cooperation and collective dilemmas. Annual Meeting of the Midwest Political Science Association, April 6.

- WWAP (United Nations World Water Assessment Programme). 2015. The United Nations World Water Development Report 2015: Water for a Sustainable World. Paris, UNESCO.