Abstract

The purpose of this cross-sectional study was to compare health-related quality of life (HRQoL) and depressive symptoms among peri-postmenopausal women with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) aged ≥43 years relative to premenopausal women with PCOS aged 18–42 years. An online survey link comprising questionnaires about demographics, HRQoL, and depressive symptoms was posted onto two PCOS-specific Facebook groups. Respondents (n = 1,042) were separated into two age cohorts: women with PCOS aged 18–42 years (n = 935) and women with PCOS aged ≥43 years (n = 107). Data from the online survey were analyzed using descriptive statistics, Pearson correlations, and multiple regression via SAS. Results were interpreted through the lens of life course theory. All demographic variables, except for the number of comorbidities, significantly differed between groups. HRQoL among older women with PCOS was significantly better as compared to those aged 18–42 years. Results indicated significant positive linear associations between the HRQoL psychosocial/emotional subscale and other HRQoL subscales and a significant negative association with age. The fertility and sexual function HRQoL subscales were not significantly associated with the psychosocial/emotional subscale among women aged ≥43 years. Women in both groups had moderate depressive symptoms. Study findings demonstrate the need to tailor PCOS management to women’s life stage. This knowledge can inform future research about peri-postmenopausal women with PCOS and age-appropriate and patient-centered healthcare, including requisite clinical screenings (e.g., depressive symptoms) and lifestyle counseling across the lifespan.

Introduction

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is a complex, heterogeneous collection of symptoms attributed to hormonal dysregulation (Azziz, Citation2020). It is the most common cause of subfertility among women, affecting ∼20% of women globally across all races and ethnicities (Engmann et al., Citation2017). Annual costs for diagnosis and treatment of PCOS exceeded $8 billion in the US in 2020 (Riestenberg et al., Citation2022). Of women diagnosed with PCOS, approximately 50% have obesity, 70% have dyslipidemia, and 80% have insulin resistance (Legro et al., Citation2013). These clinical features increase the risk for cardiometabolic diseases (Osibogun et al., Citation2020; Zhu et al., Citation2021) and reproductive cancers (Azziz, Citation2020) by ≥50% while negatively impacting health-related quality-of-life (HRQoL) (Moghadam et al., Citation2018). In addition to these complications, PCOS is associated with psychological morbidity, as women with PCOS are 3-8 times more likely than women without PCOS to have depressive symptoms (Cooney et al., Citation2017) and seven times more likely to attempt suicide (Månsson et al., Citation2008).

Historically, PCOS has been considered a controversial diagnosis given its varied symptom profiles, the debate about diagnostic criteria, and gaps in clinical providers’ knowledge (Soucie et al., Citation2021; Teede et al., Citation2018). As such, healthcare professionals and researchers have increased interest in PCOS within the last ten years. To date, most PCOS studies have only examined cardiometabolic disturbances and health-related quality-of-life (HRQoL) among women of reproductive age (Sharma & Mahajan, Citation2021). However, PCOS is a chronic condition that transcends the reproductive years and requires management across a woman’s lifespan. Older women with PCOS continue to cope with multiple risk factors due to persistent hormonal dysregulation and/or have developed one or more cardiometabolic comorbidities, even though fertility may no longer be relevant.

PCOS-specific health-related quality of life (HRQoL)

HRQoL has been defined as the physical, psychological, and social domains of health, and is seen as distinct areas that are influenced by a person’s experiences, beliefs, expectations, and perceptions (Testa & Simonson, Citation1996). Several generic instruments, such as the 36-Item Short-Form (SF-36®) Survey (RAND, Citation2016), have been developed to measure HRQoL using patients’ commonly reported health outcomes. Whereas generic HRQoL instruments can be used with most any health condition, they lack specificity for certain health conditions such as PCOS.

In 1988, Cronin et al. (Citation2007) created the first PCOS-specific HRQoL instrument by interviewing a clinical population of women with PCOS aged 18–45 years (n = 100) to identify issues associated with PCOS. The final selection of questions was based on the authors’ “clinical sensibility” and factor analysis. The original polycystic ovary syndrome questionnaire (PCOSQ) has 26 items placed in five domains: emotions (8 items), body hair (5 items), weight (5 items), infertility (4 items), and menstrual problems (4 items). As knowledge advanced about PCOS and its effect on HRQoL, researchers from the United Kingdom sought to validate the PCOSQ by determining its factor structure. The PCOSQ was modified (MPCOSQ) by adding four additional questions about acne and separating the domain of menstrual problems into two domains: menstrual symptoms and menstrual predictability (Barnard et al., Citation2007). However, the psychometrics of both the PCOSQ and the MPCOSQ revealed poor face and content validity indices, with low alpha coefficients for the domains of menstrual problems (0.56) and emotions (0.60) (Malik-Aslam et al., Citation2010). Thus, Nasiri-Amiri et al. (Citation2016) conducted a mixed-method, sequential, exploratory design to further define the components of PCOS-specific HRQoL, develop a more comprehensive instrument to assess PCOS-specific HRQoL among Iranian women aged 18–40 years and assess its psychometric properties. The new instrument, the PCOSQ-50, included 50 items in six domains: psychosocial/emotional, fertility, sexual function, obesity/menstrual disorders, hirsutism, and coping. A psychometric assessment of the PCOSQ-50 revealed a mean content validity index and ratio of 0.92 and 0.91, respectively, a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.88, Spearman’s correlation coefficients of test–retest of 0.75, and an intra-class correlation coefficient for the subscales ranging from 0.57 to 0.88 (Nasiri-Amiri et al., Citation2016). Stevanovic et al. (Citation2019) found similar psychometric properties for the PCOSQ-50 when using and assessing the instrument among a small sample of Serbian women.

In 2018, Nasiri-Amiri and associates performed exploratory factor and confirmatory analyses to further examine the factor structure of the PCOSQ-50. Based on results, 6 items were omitted, and the coping domain was replaced with a body image domain. The revised version, the PCOSQ-43, had a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.92 and an intra-class correlation coefficient that ranged from 0.91 to 0.94. However, the acceptance and usability of this version is unknown. The PCOSQ-26 and the PCOSQ-50 remain the more commonly applied PCOS-specific HRQoL instruments. To date, further recommendations for all versions include additional application and measurement among different cultural populations of women with PCOS and psychometric testing based on use among larger samples of women with PCOS (Jones et al., Citation2008; Nasiri-Amiri et al., Citation2016, Citation2018; Stevanovic et al., Citation2019).

Life course theory

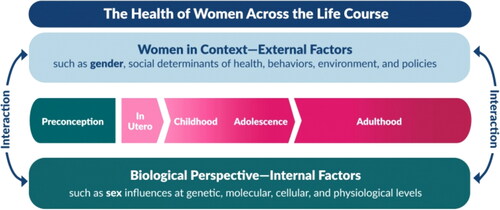

Life course theory served as a theoretical lens for this study. Life course theory is a multidimensional framework of the interaction of biological, social, and environmental factors throughout a woman’s life (Clayton, Citation2021) (see ).

Figure 1. Life course theory (Clayton, Citation2021).

The theory describes a sequence of age-differentiated events and roles embedded in a sociocultural context that people enact over time (Mortimer & Shanahan, Citation2016). These sociocultural contexts include stages of life (e.g., parenthood, menopause), social conditions (e.g., age-related norms), and relationships with other people (e.g., family, friends) during periods of human development (childhood, adolescence, adulthood, etc).

Life course theory is guided by five general principles:

Lifespan development: human development and aging are lifelong processes, and health in one stage of life can affect health later in life;

Agency: individuals have choice within the opportunities and constraints of social contexts, i.e., the agency can be constrained by the context in which women with PCOS live;

Time and place: life course is shaped by historical time and place, which help determine predominant cultural beliefs;

Timing of life events and experiences: developmental antecedents and consequences across a life trajectory vary according to timing (e.g., delayed pregnancy may cause fear, shame, embarrassment, and feelings of failing as a woman) (Kitzinger & Willmott, Citation2002); and

Interdependence: lives are lived interdependently, which impacts interpersonal contexts (Sanchez, Citation2014) i.e., social roles and relationships affect PCOS-specific HRQoL and well-being across the lifespan.

Chronic health conditions impact human development and often alter the sociocultural context for women as they navigate the life course. For example, for women with PCOS, social stigma and lower self-esteem due to symptoms such as acne, excessive male-patterned hair growth, subfertility, and miscarriages often negatively impact establishing or maintaining relationships (Wright et al., Citation2020). Delayed parenthood, PCOS symptoms (e.g., pain), and the advent of other chronic conditions may exacerbate psychosocial challenges and countervail women’s working life or financial status.

As such, we hypothesize that HRQoL among peri-postmenopausal women with PCOS remains compromised, and depressive symptoms remain common. The purpose of our cross-sectional study was to compare HRQoL and depressive symptoms among peri-postmenopausal women with PCOS aged ≥43 years relative to premenopausal women with PCOS aged 18–42 years.

Materials and methods

Study design and participants

Cross-sectional designs to implement survey research are used to explore and describe the prevalence of conditions, risk factors, and outcomes in a population (Setia, Citation2016; Wang & Cheng, Citation2020). In this study, we implemented a cross-sectional study to describe and compare the HRQoL and depressive symptoms between two age cohorts of women with PCOS. After social media recruitment, the total sample size was 935 women with PCOS aged 18–42 years and 107 women with PCOS aged ≥43 years. The study participants were recruited from two PCOS-specific Facebook groups. The inclusion criteria were women who self-reported a PCOS diagnosis. If eligible, women were invited to complete an internet-based survey using Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) to assess PCOS-specific HRQoL and depressive symptoms. The electronic link led potential participants to a website that provided additional details about the study. The introductory description of the study allowed the women to make an informed decision about study participation. Participants were informed that completing the survey would constitute implied consent. The Completely Automated Public Turing test to tell Computers and Humans Apart (CAPTCHA) was used to prevent and minimize false responses. Participants had the option to enter a drawing to win one of twelve US $50 gift cards. In accordance with 45 CFR 46.104(d)(2) and 45 CFR 46.111(a)(7), the University of South Carolina (UofSC) Institutional Review Board provided an “exempt” status for the study (Pro00118636).

Facebook groups

The two PCOS-specific Facebook pages used to post the survey link were titled PCOS Support Group (21,200 members) and PCOS Diet Support (18,000 members). Members of each Facebook page were required to apply for membership, which helped to protect against robotic responses. To gain the privilege of posting a research link, the principal investigator contacted the administrators of each group to explain the study and address any concerns. The administrators then posted the survey link on the message board, thus allowing members to access the survey.

Measures

Demographics

The demographic questionnaire included age, race, geographic location, educational attainment, number of children and comorbid conditions, and marital, employment, and insurance status.

PCOS-specific HRQoL

The PCOSQ-50 was used to measure HRQoL. Responses to all items are rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 0 = never (best condition) to 4 = always (worst condition). Each domain results in a subscale score that is calculated as the sum of all answered items divided by the number of answered items in that domain. The total PCOSQ-50 score is calculated as the sum of all answered items divided by the number of answered items. Per the PCOSQ-50 scoring guidelines, missing items are not included when calculating the domain subscale scores or the total PCOSQ-50 score. Lower scores indicate a better HRQoL. Construct validity was reported at 0.92 and test–retest reliability was reported at 0.91 (Nasiri-Amiri et al., Citation2018).

Depressive symptoms

The Personal Health Questionnaire-8 (PHQ-8) was used to assess the presence and severity of depressive symptoms women had experienced within the past 2 weeks. The PHQ-8 consists of eight items with a 4-point rating ranging from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day). As a screening instrument, PHQ-8 scores suggest potential levels depression based on the number of depressive symptoms: 5–9 mild, 10–19 moderate, and ≥20 major (Kroenke et al., Citation2009). Construct validity was reported at 0.75 and internal reliability was reported at 0.81 (Kroenke et al., Citation2009).

Data collection and management

Study data were collected and managed using REDCap hosted at the University of South Carolina. REDCap is a secure, web-based software platform designed to support data capture for research studies, providing (1) an intuitive interface for validated data capture; (2) audit trails for tracking data manipulation and export procedures; (3) automated export procedures for seamless data downloads to common statistical packages; and (4) procedures for data integration and interoperability with external sources (Harris et al., Citation2009, Citation2019).

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author (PJW) upon reasonable request.

Data analyses

Based on a moderate to small effect size and alpha 0.05, a sample size of 100 was the goal for each group. REDCap survey data were exported to SAS for Windows 9.4. (Cary, NC) (SASI, 2013), and then cleaned and analyzed. Descriptive statistics were computed on the variables. For categorical variables, the univariate construction included frequency distribution. For continuous variables, statistics included a measure of central tendency (mean and median) and a measure of dispersion (standard deviation and range). The primary outcomes for this study were the psychosocial/emotional domain subscale of the PCOSQ-50 and the depressive symptoms scale. Our main independent variable was group age. T-test and Pearson correlations were calculated to examine bivariate tests of outcomes by selected variables. Multiple regression was used to examine the relationships between a set of independent variables on the psychosocial/emotional subscale score and the depressive symptoms score.

Results

Group 1: Respondents aged ≥43 (n = 107) were 47.6 ± 4.1 years of age, mostly White (82.6%), well-educated (56% had a college degree), married (72.2%), and employed full-time (59.6%). Most respondents (82%) had one or more chronic conditions, such as high blood pressure or diabetes, in addition to PCOS.

Group 2: Respondents aged 18–42 years (n = 935) were 31.0 ± 5.8 years of age, mostly White (72%), well-educated (56% had a college degree), married (69%), and employed full-time (65%). Nearly three-quarters (74%) of the sample had one or more chronic conditions in addition to PCOS.

All demographic variables except for the number of comorbid conditions significantly differed between women with PCOS aged ≥43 years and women with PCOS aged 18–42 years. See .

Table 1. Group-based demographic and health-related characteristics of the women with PCOS in both age cohorts.

Using social media allowed participation from within and outside the United States (US): 80% of the respondents in both samples were from the US. The 20% from outside the US were from areas such as Australia, Europe, Africa, Southeast Asia, and the United Kingdom (see Appendix for full list by age group).

The means of the total HRQoL and each subscale and the depressive symptoms were calculated and then compared between age groups (). Women with PCOS aged ≥43 years scored lower (thus, better) on total HRQoL and all subscales, except for the sexual function subscale. The difference in the sexual function subscale score was not significant. Among women with PCOS aged ≥43 years, fifty-nine percent (59%) had depressive symptoms indicating moderate to severe depression. While depressive symptom scores appeared better among the older women with PCOS, the difference was not statistically significant (). Notably, the mean score for depressive symptoms among women with PCOS aged ≥43 years, like their younger cohort, indicated moderate depression.

Table 2. Differences in HRQoL and depressive symptoms between younger and older women with PCOS.

Next, Pearson correlations were calculated between the psychosocial/emotional subscale score and each of the other HRQoL subscales scores among women aged 18–42, women aged ≥43 years, and the total sample. reports Pearson correlations between the psychosocial/emotional subscale scores and each age group and the total sample.

Table 3. Relationship between the psychosocial/emotional subscale and HRQoL domains (Aged ≥43 years, aged 18–42 years, and total sample).

For women with PCOS aged 18–42 years, Pearson correlations between age and all HRQoL subscales scores ranged from −0.29 (fertility) and 0.04 (sexual function). Pearson correlations between the psychosocial/emotional HRQoL subscale score and other HRQoL subscale scores ranged from 0.28 (sexual function) to 0.70 (coping). The results indicated a significant negative association between both age and the HRQoL subscales psychosocial/emotional, fertility, obesity/menstrual, and coping. Thus, when age increased within this age group, the listed HRQoL subscales decreased (i.e., improved). When any subscale score increased (i.e., worsened), the psychosocial/emotional HRQoL subscale score also increased (i.e., worsened).

For women with PCOS aged ≥43 years, Pearson correlations between age and all HRQoL subscales scores ranged from 0.04 (fertility and sexual function) to 0.20 (psychosocial/emotional). Pearson correlations between the psychosocial/emotional HRQoL subscale scores and other HRQoL subscales scores ranged from 0.38 (fertility and sexual function) to 0.81 (coping). The results indicated positive associations with significance between this age group and the psychosocial/emotional and coping subscales. Thus, when age increased within this age group, the psychosocial/emotional and coping subscales also increased (i.e., worsened). When any HRQoL subscale score increased (i.e., worsened), the psychosocial/emotional HRQoL subscale score increased (i.e., worsened) as well.

For the total sample, Pearson correlations between age and the HRQoL subscale scores ranged from −0.35 (psychosocial/emotional) to 0.04 (sexual function). Pearson correlations between the psychosocial/emotional HRQoL subscale score and all other HRQoL subscale scores ranged from 0.26 (sexual function) to 0.71 (coping). Significant negative associations were found between age and all HRQoL subscales except sexual function, such that when age increased, most all HRQoL subscale scores decreased (improved). Significant positive associations were found between the psychosocial/emotional HRQoL subscale score and all other HRQoL subscale scores, such that when any HRQoL subscale score increased (i.e., worsened), the psychosocial/emotional HRQoL subscale score increased (i.e., worsened) as well.

Pearson correlations were calculated between the depressive symptoms scale score and each of the other HRQoL subscales among women aged 18–42, women aged ≥43 years, and the total sample ().

Table 4. Relationship between depressive symptoms scale and HRQoL domains (Aged ≥43 years, aged 18–42 years, and total sample).

Regression analysis was conducted using the psychosocial/emotional subscale score ().

Table 5. Regression model with psychosocial/emotional subscale (aged ≥43 years, aged 18–42 years, and total sample)

For women with PCOS aged 18–42 years, Pearson correlations between the depressive symptoms scale score and the HRQoL subscale scores ranged from 0.20 (sexual function and hirsutism) and 0.63 (psychosocial/emotional). The results indicated a significant positive linear association between depressive symptomology and all HRQoL domains. Thus, when depressive symptoms scores increased (i.e., worsened) within this age group, all HRQoL subscale scores decreased (i.e., improved).

For women with PCOS aged ≥43 years, Pearson correlations between the depressive symptoms scale score and the HRQoL subscale scores ranged from −0.62 (psychosocial/emotional) and −0.28 (hirsutism). Contrary to the younger cohort, the results indicated a significant negative association between depressive symptomology and all HRQoL subscales. Thus, when depressive symptoms scores increased (i.e., worsened) within this age group, the HRQoL subscale scores decreased (i.e., improved).

For the total sample, Pearson correlations between the depressive symptoms scale score and HRQoL subscale scores ranged from 0.15 (sexual function) to 0.52 (psychosocial/emotional). Significant positive linear associations were found between the depressive symptoms scale and all HRQoL subscale scores, such that when depressive symptoms scores increased (i.e., worsened), all HRQoL subscale scores increased (i.e., worsened).

Regression analysis was conducted using the psychosocial/emotional HRQoL subscale ().

For women aged 18–42 years, the results indicated that all variables in the model were statistically significant with psychosocial/emotional subscale scores. The beta coefficient for all variables is positive except for age (β = 1.63, R2 = 0.55).

For women aged ≥43 years, results revealed that only obesity/menstrual, hirsutism, and coping were statistically significant with psychosocial/emotional HRQoL subscale scores (β = −0.14, R2 = 0.72).

For the total sample, the results indicate that all variables in the model were statistically significant with the psychosocial/emotional HRQoL subscale. The beta coefficient for all variables is positive except age (β = 0.76, R2 = 0.61). For every one-year increase in age, the psychosocial/emotional HRQoL subscale is predicted to increase (i.e., improve) by 0.8 point.

cGroup-based analyses show that women ≥43 years had significantly better HRQoL as compared to younger women with PCOS. Thus, as women with PCOS age, their overall HRQoL improves due to significant changes in the obesity/menstrual, hirsutism, and coping HRQoL subscales. The fertility and sexual function HRQoL subscale scores no longer influenced the psychosocial/emotional HRQoL subscale score or total HRQoL score of older women with PCOS.

Lastly, regression analysis was conducted using the depressive symptoms score ().

Table 6. Regression model with depressive symptoms (aged ≥43 years, aged 18–42 years, and total sample)

For women aged 18–42 years, the results indicated that age (β = −0.07), the psychosocial/emotional HRQoL subscale score (β = 3.98), and the coping HRQoL subscale score (β = 1.02) were statistically significant with the depressive symptoms scale (R2 = 0.44).

For women aged ≥43 years, results revealed that the psychosocial/emotional (β = −4.54) and fertility (β = −1.38) HRQoL subscales were statistically significant with the depressive symptoms scale (R2 = 0.51).

With an R2 of 0.30, the results for the total sample indicated that the psychosocial/emotional (β = 2.63) and coping (β = 0.95) HRQoL subscales were statistically significant with the depressive symptoms scale. For every one-unit increase in the depressive symptoms scale, the psychosocial/emotional subscale is predicted to increase (i.e., worsen) by 2.6 points and the coping subscale is predicted to increase (i.e., worsen) by 1.0 point.

Discussion

Overall, the findings revealed that women aged ≥43 years had better HRQoL relative to women aged 18–42 years. In a cross-sectional study by Forslund et al. (Citation2022), HRQoL and depression were compared between older women with PCOS (52 ± 5 years) and age-matched controls without PCOS. The findings of that study indicated that HRQoL among older women with PCOS was no different than that of older women without PCOS. The authors hypothesized that overall HRQoL must have improved as the women with PCOS aged, and most likely because subfertility is no longer a concern (as evident by similar parity with age-matched controls without PCOS). The authors further posited that older women with PCOS probably develop better coping skills with PCOS and its biopsychosocial consequences (Forslund et al., Citation2022). Findings from our study support these hypotheses, as women with PCOS aged ≥43 years had a higher prevalence of ≥1 children and a significantly improved HRQoL subscale score for coping. As suggested by a principle guiding the life course theory, women’s social roles and responsibilities can dictate the perception of the PCOS biopsychosocial challenges. It can be inferred that subfertility was less of a psychosocial stressor as the majority (83%) of the older women had children, and 94% of the respondents considered themselves peri- or postmenopausal with the remaining 6% (n = 6) unsure. In addition, studies about coping among older adults have consistently found higher levels of coping, resiliency, and adaptability as compared to young adults due to accumulated personal (e.g., self-efficacy, optimism), social (e.g., family), and financial resources (Boehlen et al., Citation2017; Fuller & Huseth-Zosel, Citation2021). Consistent with the life course theory, older women with PCOS may develop increased capabilities to surpass the constraints imposed by PCOS.

Although HRQoL seemed to improve as women with PCOS aged, the findings indicated that obesity/menstrual and hirsutism continue to significantly affect HRQoL among those aged ≥43 years. First, menstrual factors were less likely an issue as over half of the participants identified themselves as menopausal with issues of fertility resolved. However, as suggested by the lifespan development principle of the life course theory, health in earlier life stages affect later life stages. The likelihood of obesity increases as women with PCOS age due to existing obesity, hyperandrogenism, and insulin resistance (Barber et al., Citation2006). Androgen levels remain stable (i.e., high) or decrease but remain relatively high (i.e., above normal range) as women enter menopause and estrogen decreases. Consequently, insulin resistance, abdominal adiposity, and dyslipidemia worsen, and excessive hair growth and balding continue past the menopausal years (Sharma & Mahajan, Citation2021). Notably, women with PCOS reach menopause, on average, 2–4 years later than that of age-matched controls (Forslund et al., Citation2019; Minooee et al., Citation2018.) Thus, PCOS complicates the natural life stage of menopause, and may negatively affect women’s HRQoL, health status, and needs. However, our findings suggest that the more bothersome PCOS sequelae and unique healthcare concerns of the menopausal transition are not included on the PCOSQ-50.

Depressive symptoms are common among women with PCOS of all ages due to the interplay between PCOS psychosocial dynamics and the hormonal disruptions associated with PCOS (Gnawali et al., Citation2021). Thus, unsurprisingly, the level of depression was comparable between the two age cohorts. However, contrary to the younger women with PCOS, the older women with PCOS reported better psychosocial/emotional and coping even when depressive symptomology increased. The prolonged transitional life stages experienced by women with PCOS may explain our finding that indicated women with PCOS aged ≥43 years experienced moderate depressive symptoms based on the depressive symptoms screening. Additionally, older women with PCOS may experience different life (e.g., aging) and health concerns (e.g., menopause, established comorbidity) than the younger women with PCOS, indicating that the PCOS-specific HRQoL scale is not designed for peri-post menopausal women with PCOS. Thus, as depicted in the life course theory, the concerns and priorities of older women with PCOS shift as the women move across their life course.

Additionally, a distinction exists between the presence of depressive symptoms versus a clinical diagnosis of depression (McIntyre, Citation2016). According to Deeks et al. (Citation2010) cross-sectional study, self-report data for depression corresponded with medically diagnosed and clinically assessed depression. However, unknown is the prevalence of women with PCOS reporting or seeking care for depressive symptoms. Depression among women with PCOS has been recognized, and international guidelines now recommend screening for depression among all women with PCOS at the time of diagnosis (Teede et al., Citation2018). We propose that screenings for depression occur throughout a woman’s life course.

The following demographic variables were significantly different between the younger and older cohorts of women with PCOS: age, educational level, employment status, medical insurance, marital status, and number of children. Consistent with the life course theory, each year of life offers opportunities to seek and complete higher education; attain employment relevant to education, and thus medical insurance; marry; and have children. As such, time also revealed women who had experienced divorce or the death of a spouse or partner. Each life phase from adolescence to menopause is extended, such that women with PCOS reach behavioral (e.g., dating) and biological (e.g., pregnancy) milestones later in life than women without PCOS. For example, corresponding to the life course theory general principle, timing of life events and experiences, time to parenthood is often extended for women with PCOS as they have an increased risk of adverse pregnancies prior to, during, and after ovulation induction and assistive reproductive technology compared to age-matched women without PCOS (Liu et al., Citation2020; Qin et al., Citation2013). Biopsychosocial issues associated with each life phase (e.g., adolescence, menopause) influence women’s perceptions of and ability to enact gender social roles (Liu et al., Citation2020), perform responsibilities of partner/caregiver/worker, and engage in self-care behaviors (Sanchez, Citation2014).

A dearth of research examined the HRQoL and depressive symptoms among women with PCOS aged ≥43 years, that is, mostly those women in the peri-postmenopausal years. We advocate for the inclusion of more frequent medical screenings, in addition to mental health screenings throughout the life course of women with PCOS. We also call for further research, especially longitudinal studies, to advance the limited knowledge about the unique biopsychosocial health and healthcare needs of older women with PCOS. Older women with PCOS are an understudied, vulnerable population at risk for premature death due to multiple chronic conditions.

Strengths

This study is one of the first to assess HRQoL and depressive symptoms among women aged ≥43 years. Thus, its findings add to the scarce information currently available about women with PCOS in the peri-post-menopausal years. The sample size of the comparison group (women with PCOS aged 18–42 years) comprised the largest cross-sectional study of women with PCOS to date and was well-described across several races and ethnicities. The online format for this study allowed for participant anonymity and was an efficient and effective method to reach a wider range of eligible and diverse respondents.

Limitations

As a cross-sectional research design, the results do not indicate causality between age and HRQoL or depressive symptoms. The sample size of the older cohort of women (n = 107) was significantly smaller than the younger cohort (n = 935). However, the sample size of 107 surpassed the target goal and provided adequate power. Additionally, per Statista (Citation2023), 43.7% of Facebook users are female, with 58% aged 18–42 years and 39.5% aged ≥43 years. Thus, there is a smaller pool of older women who use Facebook, which may have reduced the ability to recruit a larger sample size. More importantly, as indicated in our results, peri-postmenopausal women with PCOS may be coping better with PCOS and be less likely to participate in online forums. Further, many older women with PCOS have never been diagnosed (Soucie et al., Citation2021) and would not self-identify as a member of this population. The survey was administered online, thus confirmation of PCOS diagnosis was not required and all answers required self-reported data. As such, responses were subject to recall and social desirability biases. To help prevent robotic responses, internet safeguards such as CAPTCHA were added. Facebook was used for its PCOS-specific pages, as users must pass an initial level of screening to participate on the page (Boyle et al., Citation2018). In addition, the PCOSQ-50 was developed by Nasiri-Amiri and colleagues after conducting a mixed-method, sequential, exploratory study in 2011–2012 with 23 women diagnosed with PCOS aged 18–40 years (Nasiri-Amiri et al., Citation2016). Thus, the current PCOSQ-50 lacks content specific to women in their peri-postmenopausal years and presents a strong emphasis on menstruation and fertility, issues that may no longer be relevant to older women with PCOS.

Conclusion

The purpose of our cross-sectional study was to compare HRQoL and depressive symptoms among peri-postmenopausal women with PCOS aged ≥43 years relative to premenopausal women with PCOS aged 18–42 years. The main finding of this study was that HRQoL among women with PCOS seems to improve with age, yet depressive symptoms remained high, indicating moderate depressive symptomatology. The results were interpreted using the theoretical lens of life course theory. PCOS affects a woman’s life course by altering biopsychosocial needs, emotional status, and identity. Thus, the life course theory promotes perspective about and opportunity to better manage PCOS and prevent associated comorbidities during key and transitional life stages (Jacob et al., Citation2017).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the women who responded to the survey. The authors acknowledge support from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) F31 Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award (NRSA) Individual Predoctoral Fellowship (1F31 NR019206-01A1). The authors also appreciate the Center for Advancing Chronic Care Outcomes through Research and iNnovation (ACORN) in the College of Nursing at the University of South Carolina for support.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Data availability statement

Datasets can be made available upon reasonable request by emailing the corresponding author.

Institutional Review Board Approval Statement: Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval to conduct an online survey was received on 2/15/2022 (Pro00118636).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Azziz, R. (2020). Epidemiology and pathogenesis of the polycystic ovary syndrome in adults. http://www.uptodate.com/contents/epidemiology-and-pathogenesis-of-the-polycysticovary-syndrome/

- Barber, T. M., McCarthy, M. I., Wass, J. A., & Franks, S. (2006). Obesity and polycystic ovary syndrome. Clinical Endocrinology, 65(2), 137–145. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2265.2006.02587.x

- Barnard, L., Ferriday, D., Guenther, N., Strauss, B., Balen, A. H., & Dye, L. (2007). Quality of life and psychological well-being in polycystic ovary syndrome. Human Reproduction, 22(8), 2279–2286. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/dem108

- Boehlen, F. H., Herzog, W., Schellberg, D., Maatouk, I., Saum, K. U., Brenner, H., & Wild, B. (2017). Self-perceived coping resources of middle-aged and older adults: Results of a large population-based study. Aging & Mental Health, 21(12), 1303–1309. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2016.1220918

- Boyle, J. A., Xu, R., Gilbert, E., Kuczynska-Burggraf, M., Tan, B., Teede, H., Vincent, A., & Gibson-Helm, M. (2018). AskPCOS: Identifying need to inform evidence-based app development for polycystic ovary syndrome. Seminars in Reproductive Medicine, 36(1), 59–65. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0038-1667187

- Clayton, J. A. (2021). NIH takes a life course approach to researching and promoting healthy aging in women. https://orwh.od.nih.gov/about/director/messages/nih-takes-life-course-approach-researching-and-promoting-healthy-aging

- Cooney, L. G., Lee, I., Sammel, M. D., & Dokras, A. (2017). High prevalence of moderate and severe depressive and anxiety symptoms in polycystic ovary syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Human Reproduction, 32(5), 1075–1091. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/dex044

- Cronin, L., Guyatt, G., Griffith, L., Wong, E., Azziz, R., Futterweit, W., Cook, D., & Dunaif, A. (2007). Development of a health-related quality-of-life (PCOSQ) for women with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism, 83(6), 1976–1983. https://doi.org/10.1210/jcem.83.6.4990

- Deeks, A. A., Gibson-Helm, M., & Teede, H. J. (2010). Anxiety and depression in polycystic ovary syndrome: A comprehensive investigation. Fertility and Sterility, 93(7), 2421–2423. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.09.018

- Engmann, L., Jin, S., Sun, F., Legro, R. S., Polotsky, A. J., Hansen, K. R., Coutifaris, C., Diamond, M. P., Eisenberg, E., Zhang, H., & Santoro, N. (2017). Racial and ethnic differences in the polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) metabolic phenotype. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 216(5), 493.e1–493.e13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2017.01.003

- Forslund, M., Landin-Wilhelmsen, K., Schmidt, J., Brannstrom, M., Trimpou, P., & Dahlgren, E. (2019). Higher menopausal age but no differences in parity in women with polycystic ovary syndrome compared with controls. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica, 98(3), 320–326. https://doi.org/10.1111/aogs.13489

- Forslund, M., Landin-Wilhelmsen, K., Krantz, E., Trimpou, P., Schmidt, J., Brannstrom, M., & Dahlgren, E. (2022). Health-related quality of life in perimenopausal women with PCOS. Clinical and Experimental Obstetrics & Gynecology, 49(2), 052. https://doi.org/10.31083/j.ceog4902052

- Fuller, H. R., & Huseth-Zosel, A. (2021). Lessons in resilience: Initial coping among older adults during the covid-19 pandemic. The Gerontologist, 61(1), 114–125. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnaa170

- Gnawali, A., Patel, V., Cuello-Ramírez, A., Al Kaabi, A. S., Noor, A., Rashid, M. Y., Henin, S., & Mostafa, J. A. (2021). Why are women with polycystic ovary syndrome at increased risk of depression? Exploring the etiological maze. Cureus, 13(2), e13489. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.13489

- Harris, P. A., Taylor, R., Thielke, R., Payne, J., Gonzalez, N., & Conde, J. G. (2009). Research electronic data capture (REDCap) – A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. Journal of Biomedical Informatics, 42(2), 377–381. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010

- Harris, P. A., Taylor, R., Minor, B. L., Elliott, V., Fernandez, M., O'Neal, L., McLeod, L., Delacqua, G., Delacqua, F., Kirby, J., & Duda, S. N. (2019). The REDCap consortium: Building an international community of software partners. Journal of Biomedical Informatics, 95, 103208., https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103208

- Jacob, C. M., Baird, J., Barker, M., Cooper, C., Hanson, M. (2017). The importance of a life course approach to health: Chronic disease risk from preconception through adolescence and adulthood. World Health Organization: White Paper. 1–41. https://www.who.int/life-cours…health/en/

- Jones, G. I., Hall, J. M., Balen, A. H., & Ledger, W. L. (2008). Health-related quality of life measurement in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: A systematic review. Human Reproduction Update, 14(1), 15–25. https://doi.org/10.1093/humupd/dmm030

- Kitzinger, C., & Willmott, J. (2002). The thief of womanhood’: Women’s experience of polycystic ovarian syndrome. Social Science & Medicine, 54(3), 349–361. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(01)00034-X

- Kroenke, K., Strine, T. W., Spitzer, R. L., Williams, J. B. W., Berry, J. T., & Mokdad, A. H. (2009). The PHQ-8 as a measure of current depression in the general population. Journal of Affective Disorders, 114(1–3), 163–173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2008.06.026

- Legro, R. S., Arslanian, S. A., Ehrmann, D. A., Hoeger, K M., Hassan Murad, M., Pasquali, R., & Welt, C. K. (2013). Diagnosis and treatment of polycystic ovary syndrome: an endocrine society clinical practice guideline. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism, 98(12), 4565–4592. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2013-2350

- Liu, M., Murthi, S., & Poretsky, L. (2020). Polycystic ovary syndrome and gender identity. The Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine, 93(4), 529–537.

- Liu, S., Mo, M., Xiao, S., Li, L., Hu, X., Hong, L., Wang, L., Lian, R., Huang, C., Zeng, Y., & Diao, L. (2020). Pregnancy outcomes of women with polycystic ovary syndrome for the first in vitro fertilization treatment: A retrospective cohort study with 7678 patients. Frontiers in Endocrinology, 11(575337), 575337. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2020.57337

- Malik-Aslam, A., Reaney, M. D., & Speight, J. (2010). The suitability of polycystic ovary syndrome-specific questionnaires for measuring the impact of PCOS on quality of life in clinical trials. Value in Health, 13(4), 440–446. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1524-4733.2010.00696.x

- Månsson, M., Holte, J., Landin-Wilhelmsen, K., Dahlgren, E., Johansson, A., & Landén, M. (2008). Women with polycystic ovary syndrome are often depressed and anxious: A case-control study. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 33(8), 1132–1138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2008.06.003

- McIntyre, R. S. (2016). Implementing treatment strategies for different types of depression. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 77(Suppl 1), 9–15. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.14077su1c.02

- Minooee, S., Ramezani Tehrani, F., Rahmati, M., Mansournia, M. A., & Azizi, F. (2018). Prediction of age at menopause in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Climacteric, 21(1), 29–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/13697137.2017.1392501

- Moghadam, Z. B., Fereidooni, B., Saffari, M., & Montazeri, A. (2018). Measures of health-related quality of life in PCOS women: A systematic review. International Journal of Women’s Health, 10, 397–408. https://doi.org/10.2147/IJWH.S165794

- Mortimer, J. T., & Shanahan, M. J. (2016). Handbook of the life course. Springer International.

- Nasiri-Amiri, F., Ramezani Tehrani, F., Simbar, M., Montazeri, A., & Mohammadpour, R. A. (2016). Health-related quality of life questionnaire for polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOSQ-50): Development and psychometric properties. Quality of Life Research, 25(7), 1791–1801. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-016-1232-7

- Nasiri-Amiri, F., Tehrani, F. R., Simbar, M., Montazeri, A., & Mohammadpour, R. A. (2018). The polycystic ovary syndrome health-related quality of life questionnaire: Confirmatory factor analysis. International Journal of Endocrinology, 16(2), e12400. https://doi.org/10.5812/ijem.12400

- Osibogun, O., Ogunmoroti, O., & Michos, E. D. (2020). Polycystic ovary syndrome and cardiometabolic risk: Opportunities for cardiovascular disease prevention. Trends in Cardiovascular Medicine, 30(7), 399–404. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tcm.2019.08.010

- Qin, J. Z., Pang, L. H., Li, M. J., Fan, X. J., Huang, R. D., & Chen, H. Y. (2013). Obstetric complications in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology, 11(2013), 56. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7827-11-56

- RAND. (2016, October 16). 36-item short form survey from the rand medical outcomes study. RAND Corporation. http://www.rand.org/health/surveys_tools/mos/mos_core_36item.html

- Riestenberg, C., Jagasia, A., Markovic, D., Buyalos, R. P., & Azziz, R. (2022). Health care related economic burden of polycystic ovary syndrome in the United States: Pregnancy-related and long-term health consequences. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism, 107(2), 575–585. https://doi.org/10.1210/clinem/dgab613.3

- Sanchez, N. (2014). A life course perspective on polycystic ovary syndrome. International Journal of Women’s Health, 6(6), 115–122. https://doi.org/10.2147/IJWH.S55748

- SAS Institute Incorporated. (2013). SAS for Windows 9.4. SAS Institute Inc.

- Setia, M. S. (2016). Methodology series module 3: Cross-sectional studies. Indian Journal of Dermatology, 61(3), 261–264. https://doi.org/10.4103/0019-5154.182410

- Sharma, S., & Mahajan, N. (2021). Polycystic ovarian syndrome and menopause in forty plus women. Journal of Mid-Life Health, 12(1), 3–7. https://doi.org/10.4103/jmh.jmh_8_21

- Soucie, K., Samardzic, T., Schramer, K., Ly, C., & Katzman, R. (2021). The diagnostic experience of women with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) in Ontario, Canada. Qualitative Health Research, 31(3), 523–534. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732320971235

- Statista. (2023, May 11). Facebook-Statistics and facts. Statista. https://www.statista.com/topics/751/facebook

- Stevanovic, D., Bozic-Antic, I., Stanojlovic, D., Milutinovic, D. V., Bjekic-Macut, J., Jancic, J., & Macut, D. (2019). Health-related quality of life questionnaire for polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOSQ-50): A psychometric study with the Serbian version. Women & Health, 59(9), 1015–1025. https://doi.org/10.1080/03630242.2019.1587664015-1025

- Teede, H. J., Misso, M. L., Costello, M. F., Dokras, A., Laven, J., Moran, L., Piltonen, T., Norman, R. J., Andersen, M., Azziz, R., Balen, A., Baye, E., Boyle, J., Brennan, L., Broekmans, F., Dabadghao, P., Devoto, L., Dewailly, D., Downes, L., … Yildiz, B. O. (2018). Recommendations from the International evidence-based guideline for the assessment and management of polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertility and Sterility, 110(3), 364–379. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2018.05.004

- Testa, M. A., & Simonson, D. C. (1996). Assessment of quality-of-life outcomes. The New England Journal of Medicine, 334(13), 835–840. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199603283341306

- Wright, P. J., Corbett, C. F., & Dawson, R. M. (2020). Social construction of the biopsychosocial and medical experiences of women with PCOS. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 76(7), 1728–1736. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.14371

- Wang, X., & Cheng, Z. (2020). Cross-sectional studies: Strengths, weaknesses, and recommendations. CHEST Journal, 158(1S), S65–S71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2020.03.012

- Zhu, T., Cui, J., & Goodarzi, M. O. (2021). Polycystic ovary syndrome and risk of type 2 diabetes, coronary heart disease, and stroke. Diabetes, 70(2), 627–637. https://doi.org/10.2337/db20-0800