ABSTRACT

The syntax or codes used to fit Structural Equation Models (SEMs) convey valuable information on model specifications and the manner in which SEMs are estimated. We requested SEM syntaxes from a random sample of 229 articles (published in 1998–2013) that ran SEMs using LISREL, AMOS, or Mplus. After exchanging over 500 emails, we ended up obtaining a meagre 57 syntaxes used in these articles (24.9% of syntaxes we requested). Results considering the 129 (corresponding) authors who replied to our request showed that the odds of the syntax being lost increased by 21% per year passed since publication of the article, while the odds of actually obtaining a syntax dropped by 13% per year. So SEM syntaxes that are crucial for reproducibility and for correcting errors in the running and reporting of SEMs are often unavailable and get lost rapidly. The preferred solution is mandatory sharing of SEM syntaxes alongside articles or in data repositories.

KEYWORDS:

Structural equation modeling is a popular statistical technique used in many scientific fields to study causality, latent variable models, and associations in experimental, multi-level, cross-sectional, and longitudinal data. Fitting a Structural Equation Model (SEM), such as a measurement model involving constructs like intelligence or personality, or a model predicting economic trends over the years, entails numerous choices concerning the specification of the model and its estimation. For instance, in modelling a hierarchically ordered construct like intelligence, the SEM syntax specifies which manifest variables (IQ subtests) load on which first order factors (e.g., fluid intelligence, spatial intelligence, verbal intelligence), how these first order factors relate to the higher order general intelligence construct, and whether residuals are correlated between different indicators (subtests). Moreover, the SEM syntax provides information on how the model is estimated (e.g., with maximum likelihood or a robust estimation method). Unfortunately, many reviews have shown that the reporting of SEMs in the literature is often inaccurate (Jackson, Gillaspy, and Purc-Stephenson Citation2009), biased (Seaman and Weber Citation2015), or incomplete (In’nami and Koizumi Citation2011; MacCallum and Austin Citation2000; Nunkoo, Ramkissoon, and Gursoy Citation2013; Shah and Goldstein Citation2006). For instance, between 30% and 50% of articles using SEM fail to report the estimation technique used (In’nami and Koizumi Citation2011; Jackson, Gillaspy, and Purc-Stephenson Citation2009; Nunkoo, Ramkissoon, and Gursoy Citation2013) and around 10% of articles using SEM do not provide sufficient information to determine the model specification (MacCallum and Austin Citation2000). Running SEMs is also prone to human error because it entails correctly specifying the model and the correct retrieval of the numerical results from often quite extensive computer outputs. For instance, the automated procedure statcheck (Nuijten et al. Citation2016) recently noted an erroneously reported result in the SEMs reported in Wicherts, Dolan, and Hessen (Citation2005). Luckily the LISREL syntax of those analyses was still available on the first author’s current computer (his fifth since originally running those analyses) to allow a correction of this error (shared via https://pubpeer.com/publications/99075892122FC65B8752F65118B41F).

To allow readers to evaluate the specific model, to scrutinize decisions in setting up the model, to assess the specifics of estimation, and to correct potential errors in running or reporting of SEMs, it is crucial that papers reporting SEMs provide sufficient information to allow independent readers to reproduce the results if they had access to the data or the sufficient statistics (i.e., mean vectors and covariance matrices). Unfortunately, previous results (In’nami and Koizumi Citation2010) have shown that SEM syntaxes are typically unavailable after publication, which reflects a common problem in many scientific fields in the post-publication unavailability upon request of supplementary information (Krawczyk and Reuben Citation2012), underlying data (Alsheikh-Ali et al. Citation2011; Vanpaemel et al. Citation2015; Wicherts et al. Citation2006), and computer code or syntaxes used in the analyses (Howison and Bullard Citation2016). For these reasons, transparency not only with respect to data, but also concerning the syntaxes or codes applied to those data is increasingly being considered crucial in promoting reproducibility of published research results (Stodden et al. Citation2016).

The goal of this study is to assess whether the syntaxes used to run SEMs in three popular SEM packages in published articles are available upon request via email. Based on our own experiences and earlier results, we had the following two expectations: (1) that not all syntaxes would be available, and (2) that the availability of the syntaxes would decline as articles would become older (Vines et al. Citation2014).

Method

To obtain a relatively representative sample of articles using SEM with three popular SEM software packages, we first used a cited reference search in Web of Science (in February 2014) to create lists of articles referring to various editions of the Mplus manual (e.g., Muthén and Muthén Citation1998–2010; N = 987), editions of the LISREL manual (e.g., Jöreskog and Sörbom Citation1996–2003; N = 1787), or editions of the AMOS manual (e.g., Arbuckle and Wohtke Citation1999; N = 343). Next, we randomly drew samples of N = 100 for each package (after replacing articles that were unavailable via the web or our library), and considered whether indeed these articles ran SEMs using these packages. We excluded 71 articles that referred to one of the three manuals but did not report the running of SEMs on empirical data, resulting in a sample of 229 articles using SEM. The full list of references is available on the Open Science Framework (OSF) page accompanying this article: https://osf.io/hc9rr/.

Next, we attempted to contact the 229 corresponding authors by email. The templates for the emails and the reminders (sent approximately three weeks after the first email when not responded to) are given in the appendix. The OSF page provides the anonymized data file and computer codes used to run our analyses. Emails were sent between January 2016 and May 2016, while the articles were published in the period 1998–2013, with increasing numbers of articles over the years reflecting the increasing popularity of SEM (see ).

Table 1. Distribution of papers and response categories by year.

We did not pre-register our study’s analyses, but followed the analyses used in Vines et al. (Citation2014) to test our prediction that the availability of the scripts would decrease over the years since publication of the articles. We determined our sample size in advance and did not collect or exclude any additional data points. We ran our analyses with R 3.3.3 and share our script and the anonymized data via the accompanying OSF page.

Results

We exchanged a total of 510 emails and ended up obtaining 57 of the 229 requested syntaxes (24.9%). A flowchart is given in . We were unable to contact 20 corresponding authors because their email addresses were no longer in use and we were unable to find their more current email address through a search on Google or Google Scholar. A total of 209 emails were successfully delivered, but 80 of those emails were not answered despite us sending a reminder around three weeks after our first email. One hundred and twenty-nine (61.7% of delivered emails) of the corresponding authors eventually replied to our request email. Forty-one authors indicated that the syntaxes were lost or too hard to relocate (31.8% of responses), while 20 authors made a useful offer to share information (and in several cases even raw data) allowing us to reconstruct the syntax. Eleven authors made promises to share that did not materialize or provided uninformative statements that all the relevant information was in the article (about which we begged to differ) or referred to other authors who failed to respond. We obtained actual syntaxes of 57 SEM articles, representing 24.9% of the total set of syntaxes we set out to obtain and representing 44.2% of the requests that were successfully delivered and replied to.

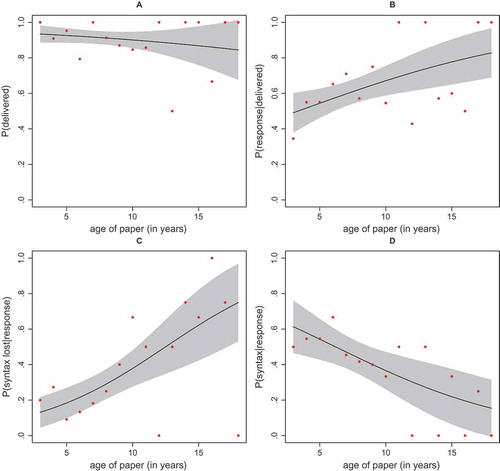

provides a breakdown of the different responses and outcomes by publication year. provides graphical displays of logistic regressions (in line with Vines et al. Citation2014) of the different types of responses and sets predicted by years passed since the articles appeared in print. Panel A shows that articles’ publication years did not predict whether our email to the corresponding author or another author was delivered (logistic regression parameters: b0 = 2.85 (SE = .56) and byear = −0.06 (SE = .06), p = .30). This highlights that we were fairly successful in finding useful email addresses of corresponding authors or co-authors in cases where the email address on the article was no longer in use. Panel B shows for the set of 209 delivered emails the predicted probabilities over the years of a response (of any type) by author. Interestingly, the chances of obtaining a response increased with article age (logistic regression parameters: b0 = −.27 (SE = .34) and byear = .10 (SE = .04), p = .019). We had no clear expectation concerning this trend and have no clear explanation for it.

Figure 2. Trend lines predicting deliverance of email (Panel A), response by authors given deliverance of the email (Panel B), loss of syntax given response (Panel C), and sharing of syntax given response (Panel D) by age of paper in years.

Of more relevance is whether the syntaxes were actually still around to be shared. Panel C shows that (for the set of 129 articles in which we obtained a response) the probability of the loss of the syntax increased sharply with article age (logistic regression parameters: b0 = −2.34 (SE = .52) and byear = .19 (SE = .06), p < .001). Specifically, the odds of the syntax getting lost increased by 21% per year, so more and more SEM syntaxes get lost as time passes. The model predicts that 10 years after publication, around 40% of syntaxes would be lost.

The yearly increases in odds of losing the syntax did not significantly differ across the three SEM packages (tested with interactions; χ2 = 1.38, DF = 2, p = .50). The overall yearly drop in odds of losing syntaxes remained high when correcting for the software package (13%, logistic regression parameter byear = .125 (SE = .067), p = .064). The latter analysis (with article age and package as factor) also showed that the Mplus syntaxes were less likely to get lost than did AMOS syntaxes (bAMOS = 1.58, SE = .68, p = .02) and LISREL syntaxes (bLISREL = 1.59, SE = .77, p = .04).

Similarly, Panel D shows (again for the 129 responses) that the probability of us obtaining the actual syntax used in the SEM articles declined with years passed since publication (logistic regression parameters: b0 = .89 (SE = .47) and byear = −.14 (SE = .06), p = .012). The odds of a syntax being available upon request dropped by 13% per year passed since publication of the SEM article. The model predicts the majority of SEM syntaxes to be unavailable around six years after publication. Also, 10 years after publication, around 36% of syntaxes are expected to be shared.

Although the yearly drop in the odds of obtaining a syntax did not significantly differ across the three SEM packages (again tested with interactions; χ2 = .89, DF = 2, p = .64), the logistic regression parameter for year (age of article) was no longer significant when correcting for software package: byear = -.032 (SE = .067), p = .63). The latter analysis that included article age (in years) and the software package as factor, also highlighted that the Mplus syntaxes were more likely to be shared than AMOS syntaxes (bAMOS = −1.65, SE = .51, p = .001) and LISREL syntaxes (bLISREL = −1.87, SE = .62, p = .003).

Discussion

This study, like many previous ones aimed at obtaining supplementary materials (Krawczyk and Reuben Citation2012), data (Vanpaemel et al. Citation2015; Wicherts et al. Citation2006), or computer codes (Howison and Bullard Citation2016; In’nami and Koizumi Citation2010), shows that important information on published studies is often unavailable upon request. This creates a situation in which many, if not most, published results cannot be fully reproduced or verified by readers after a couple of years. Notwithstanding the ease with which it should be possible to share SEM syntaxes via email, the low overall rate of availability of SEM syntaxes (24.8%) in the current study is quite similar to rates found in studies on the post-publication availability of data in psychology (between 24% and 38%; Craig and Reese Citation1973; Vanpaemel et al. Citation2015; Wicherts, Bakker, and Molenaar Citation2011; Wicherts et al. Citation2006; Wolins Citation1962). The marked drop in the odds of availability of SEM syntaxes over the years is in line with previous findings (Vines et al. Citation2014) showing a decline in the availability of data after publication in biology. The current results suggest that (for responding authors) every year the odds of a SEM syntax disappearing increases by over 20%, and that the odds of syntaxes actually being shared also drop by over 10% every year. We obviously do not know the status of syntaxes from the sizeable portion of authors whom we could not contact or who failed to respond to our email.

The current request for syntaxes (see appendix) was not specifically related to the SEM reported in the articles, but was expressed in general terms. Although this could potentially lower the response rate, one could also envision that the impersonality of our requests rendered them less sensitive than requests that would have directly concerned the substance of the article. After all, responding to a critical email concerning the original analyses could also have lowered the response rate. The responses we received from authors were cordial and only one of the contacted authors refused to share syntax (although this author did indicate a willingness to share the underlying data). Many non-sharing authors apologized for having lost the syntax. Our results show that not sharing syntax is common and might reflect a research culture that insufficiently stresses the need to keep data and accompanying syntax for later use.

We based our sample on articles in the Institute for Scientific Information (ISI) Web of Science database that referred to manuals of three popular SEM programs. For several reasons, we cannot be certain about the representativeness of our sample for all published SEM articles; not all SEM articles using these packages are listed in ISI Web of Science because not all journals are listed in this database, not all SEM articles actually refer to those manuals in the manner in which we searched them, and other manuals and SEM packages exist. Nonetheless, we do not see any clear reasons why our random sample would not reflect the wider population of SEM applications in the scientific literature. We focused on three different packages that are widely used. We did find articles using Mplus to be more recent than articles using the other two programs and indeed Mplus syntaxes were more often still around and more often shared than syntaxes from AMOS and LISREL. This might represent a confound in our analysis of trends of availability of the syntaxes over the years. However, changes in popularity of different SEM programs, and the different focuses that these programs put on the syntax (notably, Mplus requires syntax, whereas both AMOS and LISREL offer graphical interfaces) do imply changes in the availability of syntaxes needed for reproducibility. Interestingly, several AMOS users expressed some unfamiliarity with the fact that AMOS does allow one to save syntax that is crucial (or at least useful) to rerun the models at a later stage, while all contacted LISREL and Mplus users appeared to appreciate the crux of our request for the syntax. Although we did not include SEM articles using Open Mx (Boker et al. Citation2011) or Lavaan (Rosseel Citation2012), we would expect users of these other SEM packages to be more diligent in keeping syntaxes because of their key role in using these packages. Nonetheless, even there, it continues to be uncommon for SEM applications to share the syntax as part of---or alongside---the articles reporting the SEMs.

Several solutions to counter the poor and increasing unavailability of SEM syntaxes are not expected to work. These ineffective solutions include expressions in articles of promises that such information is available upon request. Such promises are for the most part not fulfilled (Krawczyk and Reuben Citation2012). Also, the links given in articles to ad hoc (faculty) websites to host the syntaxes predominantly lead to “404 not found” error messages (i.e., dead links) with the passage of time (Klein et al. Citation2014; Sampath Kumar and Vinay Kumar Citation2013; Spinellis Citation2003). Both solutions fail because they are based on overly optimistic assumptions that faculty websites are not subject to changes and that researchers are good keepers of their own data, materials, and computer codes.

The term “limitation of journal space” has become an anachronism, so the main solution to keep SEM syntaxes for later use is straightforward. The main solution requires very little extra cost given that codes of most SEM packages are short and the files typically take up fewer than 100 KB each. In fact, none of the syntaxes we obtained was larger than 100 KB, and so sharing online should not pose many technical challenges in this day and age. In our view, reviewers and journal editors should demand codes to be shared either in the appendix of SEM articles or as online supplements on the publisher’s websites. Alternatively, repositories like the Open Science Framework (Nosek, Spies, and Motyl Citation2012; Spies Citation2013), Figshare, Github, and Dataverse offer free and robust locations with persistent identifiers that can be linked to in the articles and allow easy sharing of syntaxes and data. Journal policies that require or explicitly promote sharing of data and code (Stodden, Guo, and Ma Citation2013) have been found to be effective (Giofre et al. Citation2017; Kidwell et al. Citation2016; Nuijten et al. Citation2017) and should be considered by journal editors. Simply putting the syntaxes in such repositories is often not sufficient because they should be findable, accessible, and useful for academic peers. This requires that the syntaxes (and the data) are referenced in the paper using a persistent identifier (e.g., DOI). Moreover, the shared files should be well documented and annexed with comments, and the relevant files should be accompanied by sufficient meta-data that provides potential users with sufficient information to allow full verification of the SEMs reported in research articles (e.g., which syntax was used on which data and variables using which version of a SEM package?). By sharing useful SEM syntaxes using robust locations, we can ensure that syntaxes will remain available, thereby increasing the reproducibility of SEMs in many scientific fields.

References

- Alsheikh-Ali, A. A., W. Qureshi, M. H. Al-Mallah, and J. P. A. Ioannidis. 2011. Public availability of published research data in high-impact journals. PLoS One 6:e24357. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0024357.

- Arbuckle, J. L., and W. Wohtke. 1999. AMOS 4.0 User’s guide. Chicago, IL: Small Waters Corporation.

- Boker, S., M. Neale, H. Maes, M. Wilde, M. Spiegel, T. Brick, J. Spies, R. Estabrook, S. Kenny, T. Bates, P. Mehta, and J. Fox. 2011. OpenMx: An open source extended structural equation modeling framework. Psychometrika 76:306–17. doi:10.1007/s11336-010-9200-6.

- Craig, J. R., and S. C. Reese. 1973. Retention of raw data: A problem revisited. American Psychologist 28:723. doi:10.1037/h0035667.

- Giofre, D., G. Cumming, L. Fresc, I. Boedker, and P. Tressoldi. 2017. The influence of journal submission guidelines on authors’ reporting of statistics and use of open research practices. PLoS One 12:e0175583. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0175583.

- Howison, J., and J. Bullard. 2016. Software in the scientific literature: Problems with seeing, finding, and using software mentioned in the biology literature. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology 67:2137–55. doi:10.1002/asi.23538.

- In’nami, Y., and R. Koizumi. 2010. Can structural equation models in second language testing and learning research be successfully replicated? International Journal of Testing 10:262–73. doi:10.1080/15305058.2010.482219.

- In’nami, Y., and R. Koizumi. 2011. Structural equation modeling in language testing and learning research: A review. Language Assessment Quarterly 8:250–76. doi:10.1080/15434303.2011.582203.

- Jackson, D. L., J. A. Gillaspy, and R. Purc-Stephenson. 2009. Reporting practices in confirmatory factor analysis: An overview and some recommendations. Psychological Methods 14:6–23. doi:10.1037/a0014694.

- Jöreskog, K. G., and D. Sörbom. 1996–2003. LISREL 8: User’s reference guide. Lincolnwood, IL, US: SSI Scientific Software International.

- Kidwell, M. C., L. B. Lazarevic, E. Baranski, T. E. Hardwicke, S. Piechowski, L. S. Falkenberg, C. Kennett, A. Slowik, C. Sonnleitner, C. Hess-Holden, T. M. Errington, S. Fiedler, and B. A. Nosek. 2016. Badges to acknowledge open practices: A simple, low-cost, effective method for increasing transparency. PLoS Biol 14:e1002456. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1002456.

- Klein, M., H. Van De Sompel, R. Sanderson, H. Shankar, L. Balakireva, K. Zhou, and R. Tobin. 2014. Scholarly context not found: One in five articles suffers from reference rot. PloS One 9:e115253. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0115253.

- Krawczyk, M., and E. Reuben. 2012. (Un)Available upon request: Field experiment on researchers’ WILLINGNESS to share supplementary materials. Accountability in Research: Policies and Quality Assurance 19:175–86. doi:10.1080/08989621.2012.678688.

- MacCallum, R. C., and J. T. Austin. 2000. Applications of structural equation modeling in psychological research. Annual Review of Psychology 51:201–26. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.51.1.201.

- Muthén, B. O., and L. K. Muthén. 1998–2010. Mplus user’s guide: Statistical analysis with latent variables. Los Angeles, CA, US: Muthén & Muthén.

- Nosek, B. A., J. Spies, and M. Motyl. 2012. Scientific Utopia: II - restructuring incentives and practices to promote truth over publishability. Perspectives on Psychological Science 7:615–31. doi:10.1177/1745691612459058.

- Nuijten, M. B., J. Borghuis, C. L. S. Veldkamp, L. D. Alvarez, M. A. L. M. Van Assen, and J. M. Wicherts. 2017. Journal data sharing policies and statistical reporting inconsistencies in psychology. osf.io/preprints/psyarxiv/sgbta.

- Nuijten, M. B., C. H. J. Hartgerink, M. A. L. M. Van Assen, S. Epskamp, and J. M. Wicherts. 2016. The prevalence of statistical reporting errors in psychology (1985–2013). Behavior Research Methods 48:1205–26. doi:10.3758/s13428-015-0664-2.

- Nunkoo, R., H. Ramkissoon, and D. Gursoy. 2013. Use of structural equation modeling in tourism research: Past, present, and future. Journal of Travel Research 52:759–71. doi:10.1177/0047287513478503.

- Rosseel, Y. 2012. lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. Journal of Statistical Software 48:1–36. doi:10.18637/jss.v048.i02.

- Sampath Kumar, B. T., and D. Vinay Kumar. 2013. HTTP 404-page (not) found: Recovery of decayed URL citations. Journal of Informetrics 7:145–57. doi:10.1016/j.joi.2012.09.007.

- Seaman, C. S., and R. Weber. 2015. Undisclosed flexibility in computing and reporting structural equation models in communication science. Communication Methods and Measures 9:208–32. doi:10.1080/19312458.2015.1096329.

- Shah, R., and S. M. Goldstein. 2006. Use of structural equation modeling in operations management research: Looking back and forward. Journal of Operations Management 24:148–69. doi:10.1016/j.jom.2005.05.001.

- Spies, J. 2013. The Open Science Framework: Improving Science by Making It Open and Accessible. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Virginia. https://osf.io/t23za/.

- Spinellis, D. 2003. The decay and failures of web references. Communications of the ACM 46:71–77. doi:10.1145/602421.602422.

- Stodden, V., P. Guo, and Z. Ma. 2013. Toward reproducible computational research: An empirical analysis of data and code policy adoption by journals. PLoS One 8:e67111. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0067111.

- Stodden, V., M. McNutt, D. H. Bailey, E. Deelman, Y. Gil, B. Hanson, M. A. Heroux, J. P. A. Ioannidis, and M. Taufer. 2016. Enhancing reproducibility for computational methods. Science 354:1240–41. doi:10.1126/science.aah6168.

- Vanpaemel, W., M. Vermorgen, L. Deriemaecker, and G. Storms. 2015. Are we wasting a good crisis? The availability of psychological research data after the storm. Collabra 1:1–5. doi:10.1525/collabra.13.

- Vines, T. H., A. Y. K. Albert, R. L. Andrew, F. Debarre, D. G. Bock, M. T. Franklin, K. Gilbert, J.-S. Moore, S. Renaut, and D. Rennison. 2014. The availability of research data declines rapidly with article age. Current Biology 24:94–97. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2013.11.014.

- Wicherts, J. M., M. Bakker, and D. Molenaar. 2011. Willingness to share research data is related to the strength of the evidence and the quality of reporting of statistical results. PLoS ONE 6:e26828. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0026828.

- Wicherts, J. M., D. Borsboom, J. Kats, and D. Molenaar. 2006. The poor availability of psychological research data for reanalysis. American Psychologist 61:726–28. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.61.7.726.

- Wicherts, J. M., C. V. Dolan, and D. J. Hessen. 2005. Stereotype threat and group differences in test performance: A question of measurement invariance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 89:696–716. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.89.5.696.

- Wolins, L. 1962. Responsibility for raw data. American Psychologist 17:657–58. doi:10.1037/h0038819.

Appendix

Template of first email and reminder sent to corresponding authors

Title: Request script/syntax [software package]

———————————————————————————————–

Dear Dr. [corresponding author surname],

We are currently conducting a systematic study of how the fit of structural equation models in LISREL, Mplus, or AMOS is normally reported in the scientific literature. Your study entitled “[article title]” published in [publication year] is part of our random sample and so we would like to include it. However, in order to do so we would need some additional information on your analyses. Therefore, we wondered whether you would be willing to share with us the script/syntax you used to generate the results in [software package] in your paper. We do not need the full data file, but would like to more fully appreciate the model specifications you used. We will only use the information for this stated purpose and will report results only on the aggregated level (i.e., without specifically discussing your article).

Thank you for considering our request.

Kind regards,

———————————————————————————————–

Dear Dr. [corresponding author surname],

This is a kind reminder of our request (below) for the [software package] script/syntax of your study entitled “[article title]” for use in our study. We understand that you might be too busy to help us for now. We would appreciate it if you could indicate whether you will be able to send us the script/syntax in the coming week or so.

Thank you for considering our request.

Best wishes,