ABSTRACT

Effective information mining for legal terminological research in translation is largely determined by the ability to contextualize concepts in their legal framework and to resort to relevant legal sources. Specialized knowledge of these sources thus emerges as a competence marker that is expected to converge with that of comparative law practitioners. Against this background, a survey was conducted in order to examine institutional translators’ use of resources for translation in general and their perceptions of sources for legal translation in particular. The data provided by 234 respondents from 12 international organizations offer a comprehensive portrait of translation professionals and information-mining practices in these settings. Profile features in terms of legal translation frequency, main translation specializations and academic backgrounds were correlated to relevance and reliability scores assigned to the sources used for legal terminological research. The results confirm several hypotheses based on generally accepted indicators of specialization in this field, including the prioritization of monolingual lexicographical resources over bilingual ones and the higher reliability of primary legal sources over institutional terminological databases and previous translations. Common patterns and variations between institutions and profiles, as well as their implications for institutional terminology management and translation quality, are briefly discussed.

1. Introduction

There is broad consensus that translating legal terms encapsulates the most characteristic challenges of legal translation and requires specific methodological competence, including research and information management skills. Terminological decision-making in this field entails situating concepts according to legal parameters such as legal systems and branches of law, and dealing with varying degrees of asymmetry in inter-systemic translation in light of the relevant communicative priorities. This, in turn, often involves comparative legal analysis, for which both strategic and legal information-mining competences are vital. The variability of legal translation scenarios and the dynamic nature of law further accentuate the need to consult reliable resources in order to fill any knowledge gaps and achieve communicative adequacy. This process is more about tailoring solutions on a case-by-case basis than about finding ready-made ‘equivalents’ for all instances in which a particular legal term is used (see e.g. Prieto Ramos, Citation2014; Reichling, Citation2013; Terral, Citation2004). Overall, it is presumed that higher degrees of legal asymmetry or singularity of terms in the translation-oriented legal comparative analysis correlate to higher levels of terminological difficulty and methodological competence required for decision-making.

All the above applies to legal translation-oriented terminological research at international organizations (IOs), including intergovernmental and supranational institutions. Even if the translation of international legal instruments may be considered as a case of intra-systemic translation, notions of international or supranational law do not emerge from a tabula rasa. They may draw on concepts from specific legal traditions and develop their own legal meaning, while deliberately avoiding overlaps with national terms (as stated in principle 5.3.2 of the Joint Practical Guide of the European Parliament, the Council and the Commission (European Union, Citation2015, p. 18)). However, national system-bound terms are also used in texts on the implementation of international instruments and policies at national level, both in monitoring and adjudication procedures (see e.g. Peruzzo, Citation2019; Prieto Ramos, Citation2014, pp. 127–129; Tranchant, Citation2011, pp. 201–202). Institutional translators thus deal with ‘classical’ problems of legal conceptual asymmetry when translating them. As suggested above, they require an advanced level of methodological competence in legal translation.

When a legal terminological problem has been previously analyzed for the communicative situation at hand and, on this basis, a translation proposal has been integrated in terminological resources, these recommendations may prove relevant and useful, provided that they include all the elements required for decision-making. Otherwise, various additional resources may help to complete, clarify or confirm the necessary information. This paper will examine the use of terminological resources among institutional translators, and focus on the level of relevance and reliability assigned to them for legal terminological research in particular. These practices and perceptions will be compared between institutions and translator profiles with a view to identifying variations based on translation specialization and academic background. The data used to support this analysis were obtained through a survey whose design will be described after a short outline of the background to this study.

2. Specialized resources for translation: the case of legal terminological decision-making

Translation competence models generally integrate terminological research and information management within instrumental or methodological competences, for example: ‘use of documentary resources of all kinds, terminological research, information management for these purposes’ within ‘professional and instrumental competence’ in Kelly’s model (Citation2005, p. 32); ‘knowledge related to the use of documentation sources and information technologies applied to translation’ in PACTE’s (Citation2005, p. 610) definition of ‘instrumental sub-competence’; or the abilities to ‘evaluate the relevance and reliability of information sources with regard to translation needs’, and to ‘acquire, develop and use thematic and domain-specific knowledge relevant to translation needs (mastering systems of concepts, methods of reasoning, presentation standards, terminology and phraseology, specialised sources etc.)’ as part of ‘strategic, methodological and thematic competence’ in the latest European Master’s in Translation (EMT) Competence Framework (EMT, Citation2017, p. 7). In the context of translation at intergovernmental organizations (IGOs), Lafeber (Citation2012, p. 112) includes the ‘ability to track down sources to: […] understand the topic, […] check facts, […] mine reference material for accepted phrasing and terminology, and to […] judge the reliability of sources’ under ‘research skills’.

In the case of legal translation, knowledge of specialized sources is related to both thematic and instrumental competences, under the coordination of methodological or strategic competence, in the first ‘integrative’ multi-component competence model in this field (Prieto Ramos, Citation2011, p. 12). Drawing on this model, Scarpa and Orlando (Citation2017) apply the ‘information mining competence’ descriptor of the (now revised) 2009 EMT competence wheel to legal translation, including:

- Identifying specific legal sources (e.g. dictionaries, term bases, glossaries, corpora, experts) and evaluating their reliability

- Being able to differentiate between legal sources with reference to national, international and EU systems and jurisdictions

- Extracting relevant information (documentary, terminological, phraseological) from parallel and comparable documents

- Extracting terminology from relevant documents

- Consulting legal experts so as to better understand and foresee how legal documents may be interpreted by the parties involved or the competent court or both (Scarpa & Orlando, Citation2017, p. 30)

Regardless of taxonomic differences, we can affirm: (1) that terminological research in legal translation can be considered a distinctive interdisciplinary marker of translation specialization, (2) that it is expected to converge to a large extent with the documentary skills of comparative law practitioners, and (3) that legal subject matter components of legal translator training are fundamental to that end (see e.g. Dullion, Citation2015, p. 96). The search for reliable resources may only be effectively oriented if the terminological issues at hand are situated according to the legal communicative parameters mentioned in the introduction, combining both declarative and operative specialized knowledge. Contextualizing concepts in their legal framework and hierarchy of sources (primarily, legislation or treaties, and case-law in common law systems in particular; and scholarly writings as subsidiary sources where relevant) is a key step in determining their precise meaning, before researching target-system legal sources. The relevance and reliability of primary legal sources are uncontested in Legal Translation Studies.

As regards secondary sources, it is widely accepted that monolingual legal dictionaries and lexicographical resources are generally more reliable and informative than bilingual or multilingual ones. This is traditionally related to the fact that the latter often fail to provide all the necessary information to situate concepts and their proposed translations in their legal contexts (see e.g. Biel, Citation2008; De Groot & van Laer, Citation2008; Šarčević, Citation1989).

Other information-mining patterns appear common to all branches of translation practice. Firstly, as confirmed by Désilets et al. (Citation2009) in a contextual inquiry study conducted with eight professional translators in Canada, translators tend to consult and critically judge a diversity of resources rather than trusting a single one. This can be considered a sign of thoroughness in terminological research (see also early translation process research e.g. by Jääskeläinen, Citation1999 and Künzli, Citation2001). Given the growing number of available resources, the evaluation of their relevance and reliability has become paramount. Higher levels of translation expertise may be associated with more nuance and effectiveness in judging tools and tailoring searches according to previous experience and assessments. This may lead to the use of various resources for complementary tasks (e.g. to carry out first look-ups, to expand legal analysis, to find related terms, etc.). Consequently, the above-mentioned widespread perceptions about bilingual legal dictionaries do not necessarily imply that these resources are always of limited or no use. Experience in translation-oriented research will help to discriminate the value of each source depending, among other variables, on the type of information needed, the legal implications and translation directionality. In the case of multi-domain and multilingual resources, reliability may vary between components of the same tool, depending on the topics or languages under examination.

Secondly, there is a clear trend towards the use of online resources. In her surveyFootnote1 on professional translators’ needs and expectations about lexicographical resources, Durán Muñoz (Citation2010) found that 56.47% of participants preferred online resources over electronic (24.71%) or paper (18.82%) resources. The most frequently used resources were: specialized bilingual dictionaries (18.94%), search engines (16.13%), terminological databases (8.84%), monolingual specialized dictionaries in the source language (8.63%), Wikipedia (8.63%), monolingual specialized dictionaries in the target language (7.83%) and parallel corpora (5.09%) (ibid.: 62). In another survey conducted in the same context only a few years later,Footnote2 94.5% of participants indicated that they used web-based resources ‘almost always or often’; the most popular were: Google (85.7%), bilingual and monolingual online dictionaries (82.8%), monolingual or aligned online corpora (62.4%) and terminology databases (59.7%), while paper dictionaries only ranked tenth on the list (Alonso, Citation2015, pp. 98–99).Footnote3 Today, the preference for easily accessible online resources is taken for granted across domains as translation work is increasingly digitalized. However, format and quick access are only two aspects of terminological resource evaluation, and certainly not the main ones. As pointed out by De Bessé and Pulitano (Citation1996, p. 44), what matters most is the quality of the content. As an example, in light of translators’ preferences elicited in Durán Muñoz’s survey (such as more information on usage and real examples), this author later concluded that ‘most of the terminological resources that are currently available (especially in electronic format) do not fulfill their requirements’ (Durán Muñoz, Citation2012, p. 82).

In the case of IOs, consultation of in-house resources for translation, including terminological databases and institutional corpora (see e.g. Biel, Citation2018 and Stefaniak, Citation2017), is essential for the sake of harmonization and consistency, as they contain translation precedents and recommendations for institutional communicative purposes. Significant efforts have been made to improve these resources and enhance their accessibility. However, their reliability cannot be taken for granted, as illustrated by several case studies on legal terminological records and institutional translation consistency (Giampieri, Citation2016; Prieto Ramos, Citation2014; Prieto Ramos & Guzmán, Citation2018). Against this background, our study aims to shed light on institutional translators’ use and views of resources for translation, with a focus on the sensitive area of legal terminology and the position of their institutions’ own resources in particular. Given the key role of these resources for terminological decision-making, and the connection between translation process, competence and product, the examination of translators’ information-mining practices and specialized source evaluation can provide insights of relevance for institutional translation quality assurance. To our knowledge, however, no specific study has been devoted so far to the subject within the broad spectrum of international institutional settings.

3. Methodology: survey design and hypotheses

A survey was designed in order to establish potential correlations between the following aspects: translators’ profiles in terms of specialization and background; the terminological resources used for translation in general; and the sources used for legal terminological decision-making in particular. A draft version of the survey was submitted to six practitioners with relevant expertise, including experience in legal and institutional translation and terminology work. Three of them were acting as terminologists for their respective institutions. This testing phase was instrumental to clarify or modify certain questions or categories before the large-scale distribution of the survey.

For the analysis of profiles, the following information was requested:

institution;

employment status (permanent, temporary or regular external translator);

years of translation or revision experience at the institution and overall;

main target language for translation;

main academic background (Translation, Languages / Philology, Humanities (other areas), Law, Economics, Engineering / Sciences, other);

main area of specialization if any (economic and financial, legal and administrative, technical and scientific, other);

frequency of legal translation practice, including texts of law-making or law application or with some kind of legal force or legal terminology.

A comprehensive approach was adopted in order to include as many translation professionals as possible from the relevant settings, regardless of their specific temporary or permanent status, their working arrangements (in-house or remote), or the exact proportion of translation or revision tasks. The main interest was in work patterns and translation expertise as applied in particular institutions, rather than details on locations or contractual situations. Even freelancers working regularly for a specific institution, according to the same institutional translation requirements as in-house translators, could be considered. The survey would be distributed through institutional channels to ensure that this principle would be observed, i.e. only those who worked predominantly for specific institutions could participate. Otherwise, by excluding all translators on temporary contracts or regular external assignments, the study would run the risk of overlooking an increasing proportion of institutional translation. This group, however, was expected to be modestly represented among participants due to the regular work condition set as a requirement to access the survey.

The questions on specialization, academic background and legal translation practice would provide a full portrait of expertise among institutional translators, encompassing both formal training and practical experience. Questions on self-perceived main specialization and the frequency of legal translation (characterized through a basic description of legal functions of texts in institutional settings) were conceived as complementary. Both sets of responses would be triangulated to verify the correspondence between self-perceptions and real practice, and avoid any misunderstanding on the level of acquaintance with legal terminological research. In case of more than one specialization or a ‘mixed’ academic background, more than one category could be chosen and comments could be added.

As regards resources for terminological decision-making, the list validated includes two sets of categories with a common core. In the case of main resources used in general:

monolingual lexicographical resources (such as monolingual dictionaries);

bilingual (or multilingual) lexicographical resources (such as bilingual glossaries and dictionaries);

the institution’s main terminological database;

other institutional databases (to be specified);

corpora of parallel texts / previous translations;

internal glossaries and other institutional sources (such as guidelines);

terminology discussion groups or networks;

other texts on the relevant topics (such as manuals or thematic webpages);

consultation with experts;

other resources (to be specified).

When asked about sources used in dealing with legal terminology, more specific options were provided instead of ‘other texts on the relevant topics’ and ‘consultation with experts’:

primary legal sources (such as legislation or court judgments);

legal scholarly writings (such as law manuals and articles);

thematic webpages;

consultation with legal experts.

In order to avoid overlaps and partial duplications, and to be able to focus on the relevance of source content for terminological decision-making, no category subdivisions were proposed on the basis of format, interface or accessibility (e.g. online versus paper dictionaries). Search engines were not considered as specific sources, but as instrumental tools to access parallel corpora (e.g. Linguee) or find thematic webpages (e.g. Google). Similarly, multilingual repositories and translation memories qualify as corpora of parallel texts or previous translations. In any event, respondents could specify ‘other resources’ if they wished to make an addition to the list.

As mentioned in the introduction, one of the premises of the study is that professional translators use multiple sources whose relevance may vary for different research tasks and stages. With a view to analyzing information-mining practices for translation purposes in general, the frequency of use of resources was examined as a global indicator of relevance (see details in Section 5.1). In fact, this section of the survey was intended as a way of introducing participants to the main categories, and to subsequently compare frequency of use for translation in general with source relevance for legal terminological research. It was only with regard to legal terminology that a second indicator, that of reliability, was added. While this assessment would need to be nuanced for specific purposes and sources (or even source components, as pointed out above), the survey would provide an overall picture of practices, perceptions and potential correlations per professional profile with regard to legal translation.

More specifically, in line with our review of previous research on information mining and specialized resources in legal and institutional translation, three main hypotheses will be tested:

institutional terminological databases (ITBs) and parallel corpora are the main reference source for translation in general at IOs, but not the most reliable for legal terminological decision-making in these settings;

bilingual lexicographical resources (LRs) are less relevant and reliable than monolingual ones for legal terminological work, in contrast to their use for translation purposes in general;

translators with a more marked legal specialization perceive primary legal sources and legal scholarly works as more relevant and reliable for legal terminological research than other translators.

The final version of the survey was created with LimeSurvey and was widely distributed with the support of the world’s largest network of institutional language services, the International Annual Meeting on Language Arrangements, Documentation and Publications (IAMLADP). It included an introduction on the purpose of the study and the anonymity of responses. These were collected over a period of one month. Institutional partners were consulted during the interpretation of results where relevant to clarify or corroborate certain aspects.

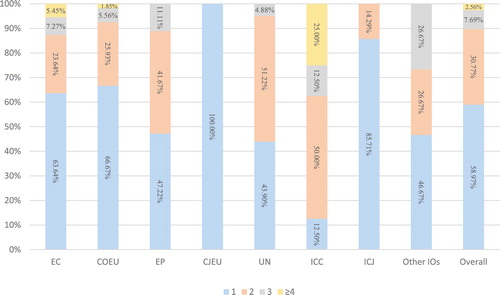

4. Profiles of respondents

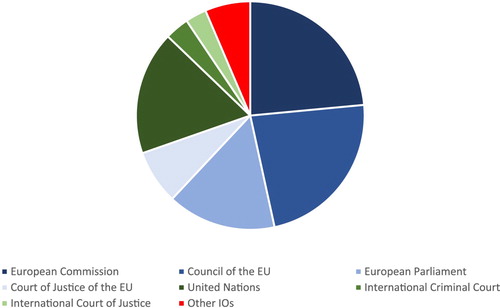

The sample population can be considered representative of translation professionals working for IOs. 234 translation professionals from 12 institutions successfully completed the survey (see ), 163 from EU institutions and 71 from IGOs and international courts. Participants from the largest translation service, the European Commission’s (EC) Directorate-General for Translation (DGT), are the most numerous (55), followed by respondents from the Council of the EU (COEU) (54), the European Parliament (EP) (36) and the Court of Justice of the EU (CJEU) (18) in the case of European supranational institutions; while the United Nations (UN) (41 participants) stood out as the most represented IGO (see ). Certain institutions were proportionally more represented than others considering their translation service sizes (e.g. the COEU, with less staff but more informants than the EP), and some did not provide sufficient data for organization-specific analysis.Footnote4 Overall, however, the response to the survey was deemed very satisfactory for the purposes of the study, and even exceeded expectations.

Table 1. Distribution of participants’ institutions.

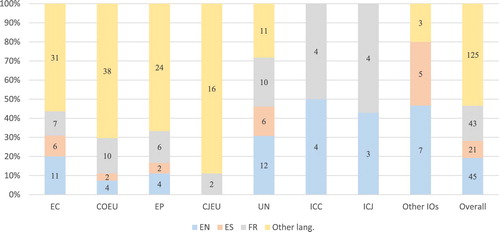

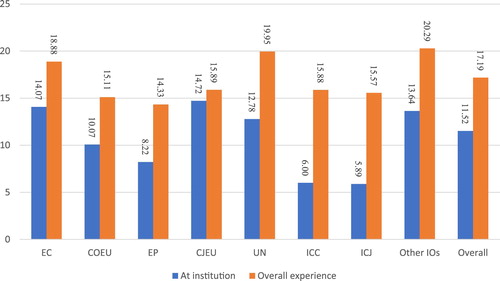

A total of 27 languages of translation were represented, including all EU and UN official languages. The largest groups were translators and revisers working into English (45 respondents or 19.23%), French (43 respondents or 18.38%) and Spanish (21 respondents or 8.97%), collectively accounting for almost half of all informants (see ). This reflects the official status of these languages in both EU institutions and IGOs, as opposed to other languages. As expected, most informants were permanent members of staff (214 = 91.45%), followed by temporary staff (14 = 5.98%) and regular external translators (6 = 2.56%). They were well-established professionals, with an average of 17.16 years of experience in translation, of which 11.52 were with their institutions of affiliation. Among the most statistically significant groups, participants from the COEU and the EP were slightly below average in terms of experience, while those from the EC, the UN and the CJEU were above average (see ). In the latter case, however, this applies only to the experience accumulated at their own institution (an average of almost 15 years), while the same group showed the shortest previous experience in translation of all settings (an average of approximately one year). This contrasts with the average lengths of previous experience of around 5 (EC and COEU), 6 (EP), 7 (UN) and 10 (ICC and ICJ) years. Curiously, therefore, the CJEU and the international courts’ translation staff are found at the two extremes of the scale for that indicator. This can be certainly related to the different entry requirements at these courts: a Law degree is mandatory to work as a translator (or rather ‘lawyer-linguist’, the official job title) at the CJEU, while this is not the case at the ICC or the ICJ.

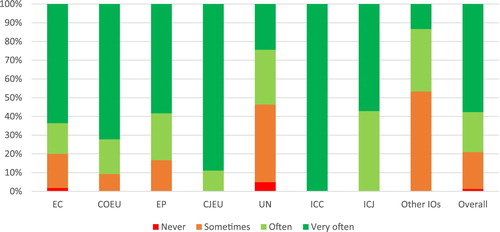

Almost 80% of respondents translated documents of law-making or law application, or with some kind of legal force or legal terminology (see and ), very often (57.69%) or often (21.37%), while almost 20% did it sometimes, and only 1.28% reckoned that they did not do legal translation at their institutions. The highest frequency scores are found at the CJEU and international courts (100% very often or often, only with variations between these two categories), followed by the EU institutions involved in the EU’s ordinary legislative procedure (very often or often for approximately 80% of translators at the EC, 83% at the EP and 91% at the COEU), the UN (54% often or very often) and other IOs (47% often or very often). On average, except for the courts, IGOs’ frequency indexes, albeit high, are the lowest, just below the ‘often’ mark. These figures are roughly in line with the volume of translation work in judicial procedures (typically at the courts), law-making (prevalent at the three EU institutions mentioned), and policy implementation monitoring (most significant at the UN and other IGOs such as the WTO, although not always associated with mandatory legal procedures) (see Prieto Ramos, Citation2017).

Table 2. Frequency of legal translation (per average index score).

The same proportions can be correlated to the main areas of specialization as perceived by translators and revisers (see ). In the case of the EU and international courts, all participants indicated legal and administrative as their main specialization. At the CJEU, two participants (11.11%) also added economic and financial translation. Otherwise, this group had the most homogeneous profile of the survey population. At the ICJ and the ICC, a few translators also had the same domain or technical and scientific translation as their second specialization. The legal and administrative specialization was also, by far, the most prevalent at the other institutions, with scores of around two thirds of informants (in the 60%–70% range). On average, almost 40% of all participants had two or more specializations and 6.41% had none (see ). These figures reflect the thematic diversity of translation in the settings under examination. The highest proportions of multiple specializations were found at the IGOs (53.66% at the UN, including a significant 24.39% with three specializations, and 60% at other IOs) and the EC (49.09%), while participants from the EP (36.11%) and the COEU (27.78%) scored below average. The differences between EU institutions involved in law-making can be related to the additional monitoring function (with an important technical dimension) of the EC. In fact, the second most common specialization stated by respondents from this institution was, together with the UN, technical and scientific translation, while economic and financial translation ranked second at the COEU, the EP and the group of other IOs. Overall, each of these two specializations accounted for around one third of responses, most often combined with legal and administrative translation. 11.54% of informants also mentioned other specializations.

Table 3. Main areas of translation specialization.

As regards the participants’ academic background, the most prominent field at all the institutions was Translation, except for the CJEU (where all lawyer-linguists have a background in Law), and the COEU and the EP (where Languages / Philology scored higher than Translation) (see ). Law was the third most frequent academic background of informants and the only one present at all the organizations, with an average of 17.09%. Apart from the CJEU, the ICC (25%) and the group of other IOs (26.67%) registered results above average for this field, and the lowest proportions were those of the UN (4.88%) and the EC (5.45%). Economics ranked fourth with a global average of 7.69%, while the other fields indicated were below 5% (see and ). Under ‘other’ academic qualifications, a broad range of fields were mentioned, particularly within the realm of social sciences: International Studies / Relations (4), Education (4), Journalism (3), Communication (2), European Studies (2), etc.

Table 4. Fields of participants’ academic backgrounds.

Interestingly, the global percentage of participants with a mixed academic background (41%) is in line with the proportion of multiple translation specializations mentioned above. Again, the CJEU was an exception due to the prevailing focus on Law, as opposed to the more diverse responses from the ICC, with the highest score of mixed academic profiles (87.5%), followed by the UN (56.1%), the group of other IOs (53.34%) and the EP (52.78%).

The triangulation of results points to a situation in which institutional legal translation (in a broad sense) is a frequent activity for almost 80% of participants, and also the main area of translation specialization as perceived by institutional translators (particularly at the EU and international courts, and less so the UN and other IGOs). However, translators’ most frequent academic background, Translation, is not as common (55.98%), and even less in the case of Law (average of 17.09% but 100% at the CJEU), as participants’ backgrounds are considerably diverse. This suggests that the specialization in legal and administrative translation (and even translation in general for some groups) is often developed through practical experience and continuous education, whether formal or informal, internal or external. In turn, this is in line with the significant proportion of translation staff who indicated more than one specialization and field of expertise, and with the thematic versatility commonly required of institutional and legal translators.

5. Survey results on use patterns and views of resources

How does the use of resources for translation in general and for legal terminological research in particular vary between the above groups of institutions and profiles? As outlined in Section 3, apart from shedding light on the common patterns, we will focus on the variations in indicators of specialized source management in legal translation in order to test our hypotheses on: the higher relevance of monolingual LRs as opposed to bilingual ones; the reliability of primary legal sources; and the use of ITBs and parallel corpora.

5.1. Overall results

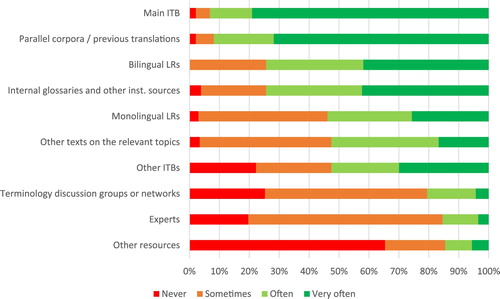

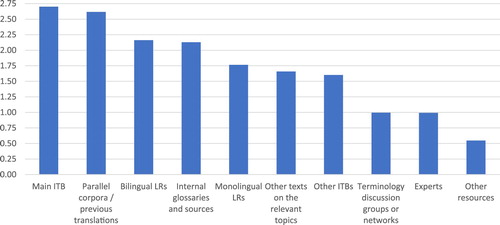

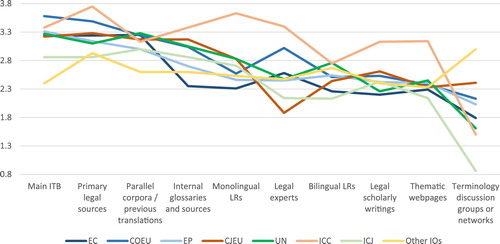

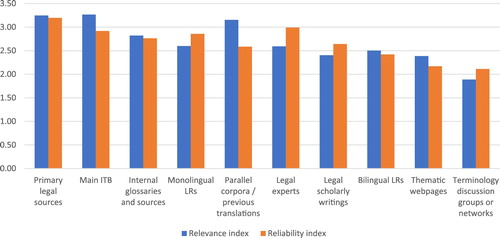

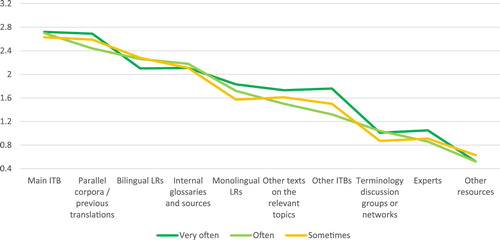

The responses to the question on main resources used for translation in general (see and and ) show a clear pattern of use of internal resources as the most relevant in institutional translation, with the main ITB at the top of the frequency ranking (93.16% very often or often, and an average index of 2.70Footnote5), closely followed by corpora of parallel texts or previous translations (91.88% and 2.62) and internal glossaries and other institutional sources, such as guidelines (74.36% and 2.13). Among external resources, bilingual LRs come first with practically the same score (74.36% and 2.16). They were preferred to monolingual LRs and other texts on the relevant topics, both registering approximately 53% for ‘often’ or ‘very often’ use, and average indexes of 1.76 and 1.66, respectively. The use of ‘other ITBs’ registered a similar level of frequency at an average index of 1.60, but with the most heterogeneous results of all the resources, including a prominent proportion of ‘never’ responses (more than 22%, the same as ‘often’ and only a few percentage points below ‘sometimes’ and ‘very often’). The most frequently used ‘other ITBs’ were: IATE (24 responses), TERMIUM (23) and UNTERM (19).

Finally, the following resources were situated at the lower part of the ranking, with frequency scores between 1 and 0.5: terminology discussion groups or networks, experts and other resources. Among the latter, which were never consulted by more than 65% of participants and only sometimes by 20%, 16 responses specified online searches or search engines (including explicitly Google in 4 cases and Linguee in 2). This represents a partial duplication of other responses in terms of source content, as these tools or ‘searches’ are mostly used as springboards to access the actual content to be mined in terminological research. They are taken for granted as instrumental in the documentation process and were not examined as separate categories in this study as explained in Section 3. While these searches were probably conducted by more informants than those who indicated they did so sometimes (approximately 7%), they were not mentioned or mixed with other content categories by the majority of participants.

Table 5. Terminological resources used for translation in general (by level of frequency).

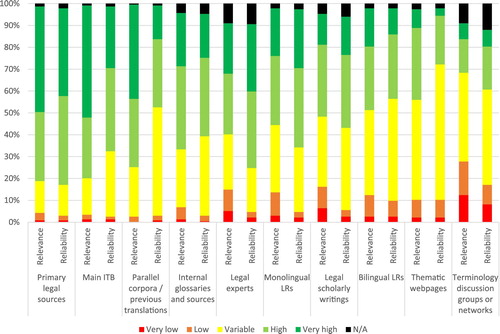

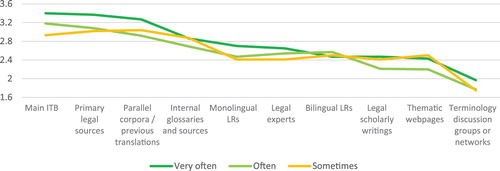

The results on the relevance and reliability of sources in dealing with legal terminology (see and , and )Footnote6 confirm some of the specificities of this specialization and the hypotheses outlined in previous sections. While the main ITB and parallel texts and previous translations are still perceived as most relevant, their reliability for the purpose of legal terminological research is lower than that of primary legal sources and legal experts. The first two source categories recorded the most significant negative difference between relevance and reliability indexes: −0.35 (main ITB) and −0.46 (previous translations). This reflects the mandatory use of these sources despite potential problems with certain translation proposals or precedents. Internal glossaries and other institutional sources come next in terms of relevance, but are also perceived as more reliable than translation precedents for legal terminological research. So are legal scholarly writings and, especially, monolingual LRs, which are considered both more relevant and reliable than bilingual LRs for legal translation. Thematic webpages and terminology discussion groups or networks appear at the bottom of both indexes.

Figure 10. Sources used for legal terminological decision-making (relevance and reliability indexes).

Table 6. Sources used for legal terminological decision-making.

Consultation with legal experts shows the highest positive difference between relevance and reliability indexes (+0.40). A comparison with this source’s frequency score in translation practice in general () points to the added value of expert advice for legal terminological research. It also suggests that the perception of experts as reliable sources does not mean that they are consulted regularly, but rather as a second or last recourse in case of difficulty. Accessibility and time constraints may also contribute to explaining these results, even if experts include in-house authors or specialists in institutional settings. In linking the general use frequency and the relevance and reliability scores for legal translation, the logic is thus exactly the opposite in comparison with the results for the main ITB and previous translations: these two resource types are regularly consulted as reference sources but are critically scrutinized.

The use of other sources for legal terminological decision-making was left for a separate open question. While 101 respondents (i.e. 43.12% of the survey population) replied to this question, most respondents specified sources already included in other categories, such as national legislation, thematic webpages, particular dictionaries or internal guidelines. The overall impression was that the question was understood by many as an invitation to add comments. As in the case of other resources for translation in general, 16 responses also made generic references to online sources or searches. Only two referred to IATE again as a relevant additional source (different from the main ITB) for legal terminological research. Given the duplications and diversity of responses, no further classification of subcategories of ‘other sources’ proved meaningful for the analysis of relevance and reliability indexes.

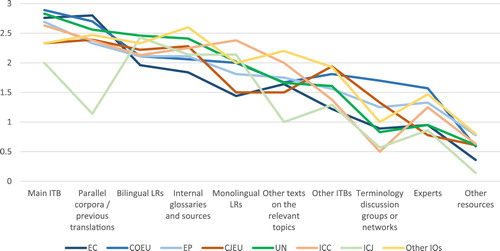

5.2. Variations between institutions

Patterns of resource use for translation in general are similar for most resource categories in all the institutions, with some exceptions and a few remarkable differences (see and ). The main ITBs and parallel corpora and previous translations scored below average at all the courts, particularly the ICJ, where the very low use frequency of the second category strikes as the most significant deviation from the main patterns elicited: 1.48 points below the average index for this resource and half the frequency registered at the CJEU and the ICC. Whereas the verification of precedents is particularly relevant for the translation of judicial genres, respondents from the ICJ seem to rely on previous translations less often than their counterparts in other settings. A number of factors may contribute to explaining these results: the ICJ deals with relatively few cases (just above two on average are adjudicated per year, compared to several hundred at the CJEU; see Prieto Ramos & Pacho Alajanti, Citation2018, p. 189), Court decisions are co-drafted in English and French, and judges’ opinions (subject to translation) are unique for each case, so the volume of re-usable text from previous translations may be more limited than in other contexts. The ICJ is also the only institution whose participants resorted more often to bilingual LRs than to any other source. By contrast, the ICC was the only institution were monolingual LRs were more frequently used than bilingual ones, although only by a small difference.

Figure 11. Terminological resources used for translation in general (frequency index per institution).

Table 7. Terminological resources used for translation in general (frequency index per institution).

The frequency index for the main ITB at the ICJ was also the lowest of the series (2 as opposed to the 2.70 average). This is certainly due to the fact that the ICJ does not have its own ITB, but its translators resort to UNTERM and other ITBs for specific searches. However, this low score is not coupled with a significant frequency of use of other ITBs (1.29, the second lowest index among the institutions), as opposed to the CJEU and ‘other IOs’, where below-average scores for the main ITB are found alongside above-average scores for other ITBs and internal glossaries and other institutional sources. Within the group of other IOs, the latter category is even the most frequently used (index of 2.60). This may be explained by the fact that some medium-size institutions such as the IMF and the WTO do not maintain fully-fledged terminological databases but rather glossaries. Given the multiple topics addressed by IGOs, translators at these institutions are also expected to consult the ITBs of other organizations and other resources relevant to their texts within the multilateral system. In fact, ‘other texts on the relevant topics’ recorded the highest use frequency of all the participant groups. Among the ‘other ITBs’, those of specialized agencies, such as FAOTERM and ILOTERM, were resorted to proportionally more often than in other settings, even if UNTERM stood out as the main external ITB, followed by IATE and TERMIUM. The most frequent ‘other ITBs’ specified within EU institutions were CuriaTerm (14 responses),Footnote7 UNTERM (13) and TERMIUM (11).Footnote8 At the UN, they were IATE (16) and TERMIUM (6), followed by ITBs of specialized agencies.

In the case of the CJEU, the combination of frequency scores for main and other ITBs and for internal glossaries reflects a specific situation in which part of the records of their main database, CuriaTerm (identified as such by 11 of 18 respondents, as opposed to IATE), particularly its collection of terminological data records Comparative Multilingual Legal Vocabulary, is integrated in IATE. During the migration of CuriaTerm into IATE (planned for completion between 2019 and 2020), both ITBs co-existed at the CJEU. As confirmed by internal informants, the first one was globally associated with the Court’s needs in legal terminology, while the second was regarded as the main ITB for other technical and EU terminology. At the same institution, experts obtained the lowest frequency score, probably because lawyer-linguists, as jurists themselves, feel less compelled to consult legal experts when translating CJEU documents. In the lower part of the frequency ranking, only COEU translators also seemed to resort to experts less often than to terminology discussion groups or networks, while the reverse applies to the remaining organizations.

Apart from these variations, the resource use patterns identified in Section 5.1 are found across the board, and are remarkably similar in the case of the main EU law-making institutions and the UN. Interestingly, however, the diversity of resources used often or very often (considering indexes of 1.80 or higher) vary as follows, from more to fewer source categories: 7 in the group of other IGOs; 6 at the COEU and the ICC; 5 at the CJEU, the EP and the UN; and 4 at the EC and the ICJ.

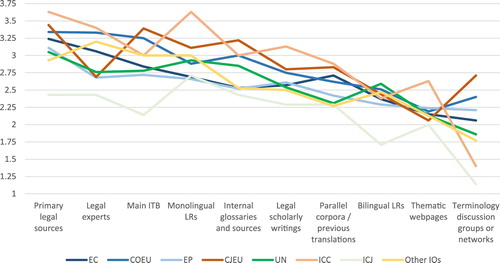

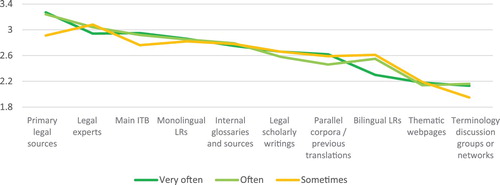

As regards resources for legal terminological research, the number of categories regarded as highly relevant drops dramatically in the case of the ICJ and the group of other IGOs, and exceptionally rises to 8 at the ICC, more than at any other institution (see and and ). Participants from this Court clearly placed legal sources and monolingual LRs at the top of the reliability scale, in line with legal translation experts’ perceptions of specialized sources (see Section 1): primary legal sources and monolingual LRs (both at 3.63), legal experts (3.40) and legal scholarly writings (3.13). These scores, the highest for these four categories among all groups, are not surprising considering the nature of legal terminological work at the ICC. The need to investigate very specific culture-bound concepts related to criminal law from various jurisdictions, such as criminal acts and ethnic epithets, sometimes in less standardized ‘situation languages’ (see Tomić & Beltrán Montoliu, Citation2013), explains the crucial importance of resorting to primary sources, experts and legal doctrine in each relevant language and local context for translation purposes. Also unsurprisingly, thematic webpages scored higher than at other institutions.

Figure 13. Sources used for legal terminological decision-making (reliability index per institution).

Table 8. Sources used for legal terminological decision-making (relevance and reliability indexes per institution).

The CJEU registered the second best scores for the same four most reliable sources as the ICC, except for legal experts (for the reasons explained above): primary legal sources (3.44), monolingual LRs (3.11) and legal scholarly writings (2.80). The other main difference from the ICC is the high ratings of internal LRs, with the best reliability indexes of all the institutions (main ITB at 3.39 and own glossaries at 3.22, as opposed to 3 for both categories at the ICC, and survey averages of 2.92 and 2.76, respectively). This can be related to the tailored approach to translation-oriented terminological work adopted by lawyer-linguists in the creation of resources such as the Comparative Multilingual Legal Vocabulary integrated in CuriaTerm (their main ITB for legal terminology) and IATE. Also in connection with translators’ involvement in terminology work, the outstanding reliability index of terminology discussion groups at the CJEU seems to reflect the perceived value of internal coordination measures to that end among lawyer-linguists.Footnote9

The other major institutions align with the global trends outlined in Section 5.1, within similar score ranges. Interestingly, among EU institutions involved in law-making, the COEU, whose survey participants registered the highest legal translation frequency of the three institutions (see ), also delivered the best reliability scores of the three respondent groups to primary legal sources, monolingual LRs, legal experts and legal scholarly writings, but also to the main ITB and internal glossaries. Perceptions of the latter two categories may be related to the traditionally good reputation of terminological records generated by the COEU.

At all the institutions, monolingual LRs are more trusted than bilingual ones for legal translation, while parallel corpora and previous translations show significant decreases between relevance and reliability indexes. The most remarkable one is found at the UN, with a difference of −0.97. This organization is, together with the ICJ, the only one where internal glossaries are more trusted than the main ITB for legal terminological research. In the case of the ICJ, they are the main terminological resource created internally (as the Court does not have its own ITB), while UNTERM moves from a high use frequency for translation in general (the second highest score of all settings –see –) to an average relevance score for legal translation and a very significant drop in reliability (−0.49), as opposed to −0.20 in the case of internal glossaries. These came third in the reliability ranking at the UN after primary legal sources and monolingual LRs, and second at the ICJ, together with primary legal sources and legal experts, and only after monolingual LRs. The most striking finding about the ICJ, however, is the low relevance and, in particular, reliability ratings registered in almost all categories.Footnote10 Finally, the other setting where primary legal sources were not regarded as the most reliable for legal translation was the group of other IGOs, which was also the context where participants reported the lowest legal translation frequency (see ). Legal experts, monolingual LRs and main ITB scored better in terms of reliability, although primary legal sources were regarded as more relevant.

5.3. Variations between profiles

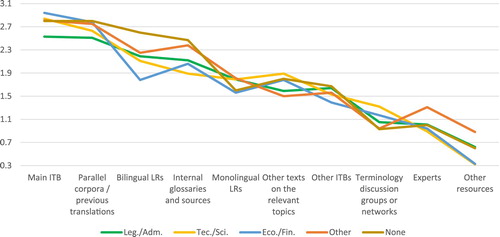

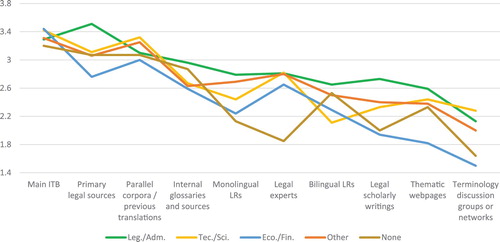

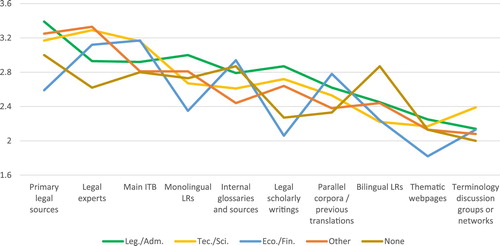

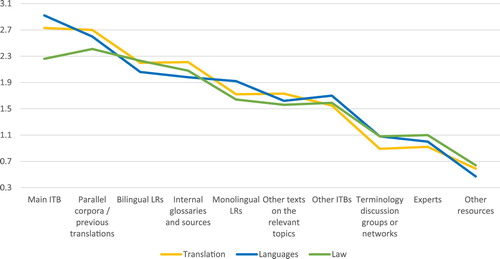

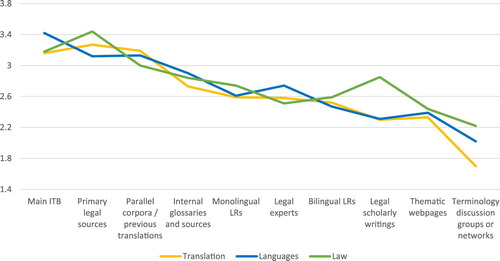

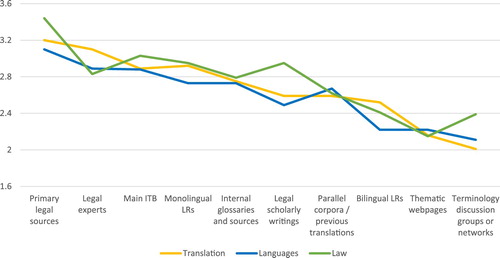

Differences based on legal translation frequency, translation specialization and academic background were globally more limited than variations between institutions, especially in the use of resources for translation in general. The survey findings also corroborate our hypotheses with regard to the use of specialized sources for legal translation: all profile indicators of higher legal expertise correlate with higher relevance and reliability scores of primary legal sources, legal scholarly writings and monolingual LRs. The indicators associated with such profiles were those previously identified according to:

legal translation frequency ( and , and ): very often (135 respondents), as opposed to often (50) and sometimes (46);

main translation specialization ( and , and ): legal and administrative translation as only specialization (73), as opposed to only technical and scientific (19), economic and financial (18), other specializations (16) and no specialization (15);

academic background ( and , and ): respondents trained in Law (39), as opposed to Translation graduates without additional Law qualifications (132) and those holding qualifications in Languages or Philology and no additional academic background in Law or Translation (53).Footnote11

Figure 14. Terminological resources used for translation in general (frequency index per legal translation frequency).

Figure 15. Sources used for legal terminological decision-making (relevance index per legal translation frequency).

Figure 16. Sources used for legal terminological decision-making (reliability index per legal translation frequency).

Figure 17. Terminological resources used for translation in general (frequency index per translation specialization).

Figure 18. Sources used for legal terminological decision-making (relevance index per translation specialization).

Figure 19. Sources used for legal terminological decision-making (reliability index per translation specialization).

Figure 20. Terminological resources used for translation in general (frequency index per academic background).

Figure 21. Sources used for legal terminological decision-making (relevance index per academic background).

Figure 22. Sources used for legal terminological decision-making (reliability index per academic background).

Table 9. Terminological resources used for translation in general (frequency index per legal translation frequency).

Table 10. Sources used for legal terminological decision-making (relevance and reliability indexes per legal translation frequency).

Table 11. Terminological resources used for translation in general (frequency index per translation specialization).

Table 12. Sources used for legal terminological decision-making (relevance and reliability indexes per translation specialization).

Table 13. Terminological resources used for translation in general (frequency index per academic background).

Table 14. Sources used for legal terminological decision-making (relevance and reliability indexes per academic background).

Variations in relevance and reliability indexes per legal translation frequency were the most modest, particularly between the ‘very often’ and ‘often’ categories. They were more marked in the case of translation specializations: the most significant divergences from legal expertise indicators were found among respondents specializing in economic and financial translation, followed by those with no main specialization. Finally, the results by academic background show how institutional translators trained in Law are more predisposed to relying on primary legal sources and legal scholarly writings than their colleagues with other backgrounds. Among the other two major groups examined, Translation graduates assigned similar scores to monolingual LRs and their perceptions of legal sources appeared closer to those of Law graduates than those of Languages or Philology graduates, which may be associated with distinctive training in legal translation and its benefits in terms of information mining, thematic and methodological competences. This interpretation, however, calls for further exploration, as would be the case for other potential factors such as training measures or years of experience.

A comparison of the selected cluster of profile indicators associated with higher legal expertise (see ) shows the remarkable similarity of relevance and reliability scores for legal terminological decision-making among these groups. The comparison also suggests a significant level of convergence of patterns through translation practice (and, presumably, professional training and development) across institutions, especially considering the diverse sizes and affiliations of the sub-populations compared (135, 73 and 39 respondents in each group as presented, respectively, in , covering all institutional settings).

Table 15. Sources used for legal terminological decision-making (comparison of relevance and reliability indexes between profiles).

6. Conclusions

Our findings shed light on institutional translators’ use and perceptions of sources for legal terminological research as a marker of specialized translation competence. This study has entailed not only a correlative analysis of profile features against relevance and reliability ratings of sources used for legal translation, but also a comparison with patterns of use of resources for translation in general, including the analysis of variations between institutions. The description of the participants’ profiles, essential for comparative purposes, has proved extremely rich in light of the wide scope of the survey population. It confirms the overall prominence of legal and administrative translation at IOs, as supported by crossing legal translation frequency ratings and self-perceptions of main specialization. The results delineate three levels of legal specialization in accordance with the nature of the IOs’ translation work for institutional missions: the CJEU and international courts (essentially devoted to judicial proceedings); EU institutions primarily involved in law-making (EC, COEU, EP); and the UN and other IGOs (with a comparatively higher emphasis on monitoring processes and a less marked perception of legal specialization).

Except for the homogeneous legal profile of lawyer-linguists at the CJEU, academic backgrounds are diverse, although predominantly in Translation and Languages, and more rarely in Law (17.09% of respondents had legal qualifications of some kind), which suggests that many participants with no legal studies or formal training in legal translation develop their knowledge of specialized sources for translation-oriented legal analysis through professional practice or continuous education. Nonetheless, a significant proportion of respondents indicated more than one academic field and one translation specialization (overall averages converging at approximately 40%), which is indicative of the diversity and versatility of institutional translation teams. This is not surprising considering the multiple domains covered by IOs and the accumulated translation experience of the participants (on average, 17 years, including 6 before joining the institution of affiliation).

Survey results confirm translators’ recourse to a wide range of sources, as well as the priority given to internal resources (especially, the main ITBs and previous translations) for the mandatory verification of internal recommendations, conventions and precedents in institutional translation. However, the reliability of these resources obtained lower ratings than their relevance levels for legal terminological research, and it is primary legal sources that were the most trusted resources for these purposes across the board (hypothesis 1). The reverse applied to legal experts: their reliability scored better than their relevance, as they are not necessarily consulted as a first recourse, particularly among translators with a legal expertise themselves. As also hypothesized, monolingual LRs were perceived as more relevant and reliable for legal translation than bilingual LRs, although they were less frequently used than the latter for translation in general (hypothesis 2). This trend was particularly marked in the case of higher levels of legal specialization (as triangulated through indicators of legal translation frequency, main area of translation and academic background), which also correlated to higher relevance and reliability scores of primary legal sources and legal scholarly works (hypothesis 3). Based on the same indicators, the comparative analysis of profiles revealed a significant inter-institutional convergence of perceptions through legal translation frequency, despite persistent differences between main specializations (particularly between legal and administrative, and economic and financial) and academic backgrounds. Translation graduates’ ratings of legal sources, however, were closer to those of legal profiles than those of Languages graduates. Previous training in legal translation and information management among respondents of the first group could account for the difference.

The most salient divergences between institutions were not necessarily explained by these profile variations, but were often associated to the nature of terminological research (e.g. diversity of legal sources of relevance to the ICC), the availability of adapted resources (e.g. the ICJ not having its own ITB as opposed to the highly regarded CuriaTerm at the CJEU) or the quality of legal terminology components of such resources (e.g. sharp contrast between UNTERM’s general use patterns and reliability scores for legal translation, and remarkable difference between relevance and reliability of previous translations also at the UN). Some of these findings actually point to legal lexicographical gaps and consistency issues elicited in previous case studies, as mentioned above, and are worth further examination, especially with a view to improving resource reliability. Likewise, the connection between legal source mining skills and legal translation quality is worth exploring. If we assume that advanced knowledge of specialized sources supports better oriented and more effective legal analysis for translation, the correlations outlined here can be regarded as the tip of an iceberg, and can inform detailed analyses of translation processes and products. From an institutional perspective, the nuance provided on multiple co-existing profiles at IOs also yields insights that can be used to refine recruitment approaches, job assignments, training measures or translation quality assurance practices.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Diego Guzmán for his valuable assistance with data processing, as well as all institutional informants for their kind cooperation in the framework of the LETRINT project.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes on contributor

Fernando Prieto Ramos is a full professor and director of the Centre for Legal and Institutional Translation Studies (Transius) at the University of Geneva’s Faculty of Translation and Interpreting. Former lecturer and researcher of the Centre for Translation and Textual Studies at Dublin City University, he regularly publishes and delivers guest lectures on legal and institutional translation, and has received several academic awards, including a European Label Award for Innovative Methods in Language Teaching from the European Commission and a Consolidator Grant for his project on ‘Legal Translation in International Institutional Settings’ (LETRINT). He has also translated for various organizations since 1997, including five years of in-house service at the World Trade Organization (dispute settlement team).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 402 replies from translation professionals in the Spanish context, of which 61.96% had formal training in translation and 36.57% had legal translation as a specialization domain (the second most frequent was business translation at 34.82%).

2 302 participants, including 90 (21.8%) working for a local, national or international institution, and 41% with a legal-economic/sworn translation specialization (ibid.: 95–96).

3 Gallego Hernández (Citation2015) obtains similar data: more than 80% of the 581 informants use bilingual dictionaries and Google often or very often in their research.

4 Considering the size of the translation services and the number of official languages in each case, the results for the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO), the World Trade Organization (WTO) and the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) (with 6–3 responses) were not considered statistically adequate for such purposes, even if their respondents contributed to the global results. They were included in ‘other IOs’. However, for the same reasons, and because of the legal nature of their work, the cases of the International Criminal Court (ICC) and the International Court of Justice (ICJ) were isolated for individual analysis where relevant. Respondents from these Courts actually accounted for the highest proportions of their corresponding populations (around 35% and 47% of the relevant staff, respectively, according to figures from internal informants).

5 Frequency values, as specified in : very often = 3; often = 2; sometimes = 1; never = 0.

6 Values used for the calculation of relevance and reliability indexes, as specified in this table: very high = 4; high = 3; variable = 2; low = 1; very low = 0.

7 Including CJEU respondents who indicated IATE as their main ITB, and respondents from other EU institutions who identified CuriaTerm as the source of terminological records within IATE, even if CuriaTerm cannot be consulted from outside the CJEU.

8 EURAMIS (European Advanced Multilingual Information System) was also mentioned in responses by EU institutional translators. Strictly speaking, however, this resource is not an ITB, but rather works like a translation memory with a concordancing tool that enables terminological searches.

9 This information, as well as the overall interpretation of differences between the three Courts examined, was corroborated after consulting with informants from the relevant institutions.

10 Interestingly, the shape of the line formed by the ICJ’s reliability scores in is extremely similar to that of ICC respondents, albeit systematically lower.

11 Other academic backgrounds were not compared here because they were not quantitatively or qualitatively relevant for this purpose (see ).

References

- Alonso, E. (2015). Analysing the use and perception of Wikipedia in the professional context of translation. Journal of Specialised Translation, 23, 89–116. https://jostrans.org/issue23/art_alonso.pdf

- Biel, Ł. (2008). Legal terminology in translation practice: Dictionaries, googling or discussion forums? SKASE Journal of Translation and Interpretation, 3(1), 22–38. http://www.skase.sk/Volumes/JTI03/pdf_doc/BielLucja.pdf

- Biel, Ł. (2018). Corpora in institutional legal translation: Small steps and the big picture. In F. Prieto Ramos (Ed.), Institutional translation for international governance: Enhancing quality in multilingual legal communication (pp. 25–36). Bloomsbury.

- De Bessé, B., & Pulitano, D. (1996). Which terms should firms or organisations include in their terminology banks?: The case of the Canton of Berne. In H. Somers (Ed.), Terminology, LSP and translation: Studies in language engineering in honour of Juan C. Sager (pp. 35–46). John Benjamins.

- De Groot, G.-R., & van Laer, C. J. P. (2008). The quality of legal dictionaries: An assessment. Maastricht Faculty of Law Working Paper 2008/6.

- Désilets, A., Melançon, C., Patenaude, G., & Brunette, L. (2009, August 29). How translators use tools and resources to resolve translation problems: An ethnographic study. In Proceedings of the Machine Translation Summit XII - Workshop ‘Beyond Translation Memories: New Tools for Translators’. http://mt-archive.info/MTS-2009-Desilets-2.pdf

- Dullion, V. (2015). Droit comparé pour traducteurs : de la théorie à la didactique de la traduction juridique. International Journal for the Semiotics of Law – Revue Internationale de Sémiotique Juridique, 28(1), 91–106. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11196-014-9360-2

- Durán Muñoz, I. (2010). Specialized lexicographical resources: A survey of translators’ needs. In S. Granger, & M. Paquot (Eds.), eLexicography in the 21st century: New challenges, new applications. Proceedings of eLex2009 (pp. 55–66). Presses Universitaires de Louvain.

- Durán Muñoz, I. (2012). Meeting translators’ needs: Translation-oriented terminological management and applications. Journal of Specialised Translation, 18, 77–92. https://www.jostrans.org/issue18/art_duran.pdf

- EMT. (2017). European Master's in Translation. Competence Framework 2017. European Commission. https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/info/files/emt_competence_fwk_2017_en_web.pdf

- European Union. (2015). Joint Practical Guide of the European Parliament, the Council and the Commission for persons involved in the drafting of European Union legislation. Publications Office of the European Union.

- Gallego Hernández, D. (2015). The use of corpora as translation resources: A study based on a survey of Spanish professional translators. Perspectives, 23(3), 375–391. https://doi.org/10.1080/0907676X.2014.964269

- Giampieri, P. (2016). A critical comparative analysis of online tools for legal translations. The Italian Law Journal, 2(2), 445–461. http://www.iusimpresa.it/risultati.php?anno=2016&numero=2&id_rivista=330&id_editore=7

- Jääskeläinen, R. (1999). Tapping the process: An exploratory study of the cognitive and affective factors involved in translating. University of Joensuu Publications in the Humanities.

- Kelly, D. (2005). A handbook for translator trainers. St. Jerome.

- Künzli, A. (2001). Experts versus novices : l’utilisation de sources d’information pendant le processus de traduction. Meta: Translators’ Journal, 46(3), 507–523. https://doi.org/10.7202/003363ar

- Lafeber, A. (2012). Translation skills and knowledge – Preliminary findings of a survey of translators and revisers working at inter-governmental organizations. Meta: Translators’ Journal, 57(1), 108–131. https://doi.org/10.7202/1012744ar

- PACTE. (2005). Investigating translation competence: Conceptual and methodological issues. Meta: Translators’ Journal, 50(2), 609–619. https://doi.org/10.7202/011004ar

- Peruzzo, K. (2019). When international case-law meets national law: A corpus-based study on Italian system-bound loan words in ECtHR judgments. Translation Spaces, 8(1), 12–38. https://doi.org/10.1075/ts.00011.per

- Prieto Ramos, F. (2011). Developing legal translation competence: An integrative process-oriented approach. Comparative Legilinguistics – International Journal for Legal Communication, 5, 7–21. https://doi.org/10.14746/cl.2011.5.01

- Prieto Ramos, F. (2014). Parameters for problem-solving in legal translation: Implications for legal lexicography and institutional terminology management. In A. Wagner, K.-K. Sin, & L. Cheng (Eds.), The Ashgate handbook of legal translation (pp. 121–134). Ashgate.

- Prieto Ramos, F. (2017). Global law as translated text: Mapping institutional legal translation. Tilburg Law Review, 22(1–2), 185–214. https://doi.org/10.1163/22112596-02201009

- Prieto Ramos, F., & Guzmán, D. (2018). Legal terminology consistency and adequacy as quality indicators in institutional translation: A mixed-method comparative study. In F. Prieto Ramos (Ed.), Institutional translation for international governance: Enhancing quality in multilingual legal communication (pp. 81–101). Bloomsbury.

- Prieto Ramos, F., & Pacho Alajanti, L. (2018). Comparative interpretation of multilingual law in international courts: Patterns and implications for translation. In F. Prieto Ramos (Ed.), Institutional translation for international governance: Enhancing quality in multilingual legal communication (pp. 181–201). Bloomsbury.

- Reichling, C. (2013). Terminologie juridique multilingue comparée. In C. Mauro, & F. Ruggieri (Eds.), Droit pénal, langue et Union européenne (pp. 129–163). Bruylant.

- Šarčević, S. (1989). Conceptual dictionaries for translation in the field of law. International Journal of Lexicography, 2(4), 277–293. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijl/2.4.277

- Scarpa, F., & Orlando, D. (2017). What it takes to do it right: An integrative EMT-based model for legal translation competence. Journal of Specialised Translation, 27, 21–42. https://jostrans.org/issue27/art_scarpa.pdf

- Stefaniak, K. (2017). Terminology work in the European Commission: Ensuring high-quality translation in a multilingual environment. In T. Svoboda, Ł Biel, & K. Łoboda (Eds.), Quality aspects in institutional translation (pp. 109–121). Language Science Press.

- Terral, F. (2004). L’empreinte culturelle des termes juridiques. Meta: Translators’ Journal, 49(4), 876–890. https://doi.org/10.7202/009787ar

- Tomić, A., & Beltrán Montoliu, A. (2013). Translation at the International Criminal Court. In A. Borja Albi, & F. Prieto Ramos (Eds.), Legal translation in context: Professional issues and prospects (pp. 221–242). Peter Lang.

- Tranchant, I. (2011). Les méthodes de traduction et la terminologie juridique : L’expérience du département de langue française de la Commission européenne. In M. Cornu, & M. Moreau (Eds.), Traduction du droit et droit de la traduction (pp. 199–206). Dalloz.