ABSTRACT

In the wake of the platform economy’s transformative influence on translation work, this study aims to address a critical concern: the alignment of translation workers’ labour conditions with the principles of decent work. Through a quantitative analysis of a subset of questionnaire data collected from translators in Turkey engaging with various digital labour platforms, the findings suggest substantial disparities in meeting the six fundamental conditions of decent work, as defined by the International Labour Organization (ILO). These include insufficient earnings, excessive and asocial working hours, difficulties in achieving work-life balance, absence of a safe and healthy work environment, limited social security access, and a deficiency in social dialogue, representation, and workplace democracy. The identified issues align with the findings of prior studies, which warn that the techno-political developments in the translation industry, coupled with the dominance of capitalist business structures, may introduce new challenges and constraints to translation work and its workers, ultimately leading to exploitative and unsustainable working conditions.

1. Introduction and background

In the last few decades, digital transformations of work have led to significant changes in the translation industry and substantially altered labour conditions of translation workers. This transformation has become more visible especially with widespread use of digital labour platforms for the production and management of translation and other related activities. According to the International Labour Organization (ILO), a United Nations (UN) agency for labour issues, digital labour platforms, hereafter referred to as ‘platforms’, facilitate work by harnessing ‘digital technologies to “intermediate” between individual suppliers (platform workers and other businesses) and clients, or directly engage workers to provide labour services’ (ILO, Citation2021, p. 33). These platforms have brought new work opportunities and flexibility to workers and businesses to connect globally, but they have also made the working conditions more challenging.

Many of the platforms function as translation agencies and have dramatically lowered barriers to entry, allowing anyone proficient in two languages with a computer or smartphone, an internet connection and an email address to participate in translation work. Most of them engage in the recruitment of freelance translation workers through both internal and external online marketplaces. To search and find translation jobs online, thousands of translation workers from all around the world now have profiles on these platforms. According to CSA Research (Citation2020, p. 39), 89% of ca. 7,000 freelancers who responded to their survey reported to regularly engage with platforms (vendor portals, marketplaces and online computer-assisted translation platforms), with an average of five platforms per person. CSA Research (CSA Research, Citation2020, p. 36) also reports that 85% of respondents consider building strong profiles on digital marketplaces important to find translation jobs. Although the digital transformation of translation labour was already well established in pre-pandemic times, the COVID-19 pandemic accelerated this digital transformation across the globe, reducing its evolutionary span from years to months (OECD, Citation2020). Unlike traditional translation agencies, platforms rely heavily on automation, algorithmic management, and peer to peer production methods. Their infrastructures enable the integration of various technologies, teams, data, and processes within a unified digital framework. Therefore, the utilisation of platforms has become a standard practice in the industry. Many traditional translation companies already added this type of work to their business models by engaging with cloud-based translation, vendor management platforms and online translation production technologies, mainly due to project requirements, ease of access/use or simply because of the growth and proliferation of the platform economy.

The ILO (Citation2021, p. 44) reports that platform work is predominantly outsourced by businesses in the Global North to workers in the Global South to reduce costs. This is visible in countries such as Turkey, which is experiencing record inflation, currency depreciation and high level of unemployment. Working with platforms has become one of few options for translation workers from Turkey to earn in foreign currency (USD, EUR, etc.), compensate for the high cost of living and mitigate the effects of hyperinflation on their living costs. The presence of platforms has grown significantly in Turkey in the last decade, transforming into an important marketplace with good potential to provide work and income opportunities. There are no reliable statistics on the translation market in Turkey; yet, when filtered for the English-Turkish language pair, one of the biggest and oldest platforms Proz listed over 23,000 registered translators on its marketplace in February 2024.

While growing exponentially, the platform economy has introduced numerous benefits and challenges within the translation industry. Notably, its positive impact is often recognised through its collaborative, flexibility and accessibility dimensions, integration of various automation systems, and the facilitation of global connectivity (Gough et al., Citation2023; Jiménez-Crespo, Citation2017). However, the ongoing digital transformation of translation within capitalist market dynamics has also been a cause for concern about unfair, unsustainable and exploitative work practices. Working conditions and the platform economy have been discussed in Translation Studies using terms such as (digital and neo) taylorism, (post)fordism, uberisation, technocapitalism and platform capitalism, all of which point to worsening conditions for translation workers (Baumgarten & Cornellà-Detrell, Citation2017; Lambert & Walker, Citation2022; Moorkens, Citation2020b; Olohan, Citation2017; Sadek, Citation2018; Şahin & Oral, Citation2021).

For instance, Garcia (Citation2017), Moorkens (Citation2020a) and Baumgarten and Bourgadel (Citation2023), examined Taylorism in translation crowdsourcing on platforms, and highlighted its drawbacks such as loss of control, status and agency, increased monitoring and algorithmic surveillance, low pay, job security and exploitation, that results in a gradual devaluation of human experience and historical knowledge. In this context, Fırat (Citation2019, Citation2021) investigated the labour conditions of translators living in Turkey and working with platforms. He argues that the translation industry is going through an ‘uberisation’ process due to platform capitalist business models exposing translation workers to risks related to employment status, income, work hours, work-life balance, social protections, agency, bargaining power, platform dependency, risk-reward distribution, and data privacy. According to Giustini (Citation2024), this uberisation process extends to the interpreting side of the profession, leading to similar adverse work conditions for interpreters labouring on platforms, including those associated with monetary factors, algorithmic control, individualisation of employment relations, on-demand availability, and subjugation to a digital form of supply-demand intermediation. In a parallel perspective, Cukur (Citation2023) contends that platforms undermine the well-being and autonomy of translators in various ways, while clients mostly gain from their utilisation. Through a survey involving 804 platform translators, Gough et al. (Citation2023, pp. 67–68) also revealed that a significant majority of platform translators held unfavourable views regarding working on platforms. As per their findings (Gough et al., Citation2023, p. 63), the challenges encompass time constraints, negative competition, translation process-related issues like a shift from self-revision to drafting, a lack of control over workflow or final quality, translating out of context, a lack of trust among collaborators, inadequate training/briefing, variations in translation styles, insufficient remuneration, disparities in translators’ competencies, and technical issues. The Fairwork (Citation2022) project extensively examined working conditions within platform-based translation and transcription companies against five Fairwork principles: fair pay, fair conditions, fair contracts, fair management, and fair representation. The report (Fairwork, Citation2022, pp. 2–3) concludes that the platform companies fall short of meeting basic fair work standards. Particularly, fair pay for online translation and transcription workers is identified as a significant challenge, with eight out of nine platforms failing to demonstrate that the majority of workers earn at least their local minimum wage after costs (Fairwork, Citation2022). Furthermore, in examining the connection between time and remuneration in the translation market, do Carmo (Citation2020, p. 52) argues that the widespread use of post-editing of machine translation output, a common service on various platforms, has not led to an increase in translation rates. Consequently, the value of time spent in translation is depreciated, with translation workers bearing the cost, and the disruptive impact of machine translation further accelerating the devaluation of human translation (do Carmo, Citation2020). Zwischenberger (Citation2023) explored the ethical implications of translation crowdsourcing on platforms for profit-oriented companies and concluded that when translators contribute to such crowdsourcing endeavours via platforms, even voluntarily, they may be exposed to exploitative conditions. Şahin and Gürses (Citation2023) also highlighted how platforms and other technological advancements intensify concerns about payment, privacy, ownership, and confidentiality in translation by arguing that translators’ intellectual property rights are at risk, as their data may be vulnerable to processing and appropriation by major service providers. Carreira (Citation2023) examined the market concentration in the translation industry by a few monopolies and claims that the current industrial landscape of translation may leave freelance translators and similar language professionals working for translation agencies with almost no market power, making it difficult for them to establish favourable working conditions and earn a decent living.

Although there is a significant body of research in Translation Studies focusing on the digitisation of translation work, and a growing literature addressing the labour conditions of translation workers, there remains a gap for more empirical studies, particularly with insufficient data from the Global South. More importantly, none of the prior studies have approached the subject from the perspective of Labour Studies or considered international labour standards such as the ILO Decent Work Agenda. Against this overall socioeconomic backdrop, this study provides a critical assessment concerning the working conditions of translation workers in the platform economy. Unlike previous research on digital translation work, this study explores and analyses working conditions from a Labour Studies perspective by utilising six basic decent work standards established by the ILO (Citation2008, Citation2013). To provide an empirical analysis, a quantitative questionnaire was conducted with 48 translation workers from Turkey who are engaged in paid work with platforms. The following section explains the decent work indicators as defined by the ILO. Thereafter, the questionnaire results are presented and discussed in the context of the indicators to understand the labour conditions of translation workers in the platform economy.

2. Decent work

The ILO indicators are particularly relevant to this study for two interrelated reasons. First, they were proposed as a response to the increasing precarity and informality of labour relations in the digital economy. Second, as the UN agency for labour issues, the ILO has a legitimate statute to provide a common framework and understanding of decent work conditions regulated with legally binding conventions in the form of international treaties that may be ratified by UN member states.

Arguably, ILO’s decent work standards satisfy core universal human needs, namely survival, connectedness and self-determination. Researchers from the field of Psychology of Work such as Blustein et al. (Citation2019, np.) point out that ‘the loss of decent work undermines individual and societal well-being’. Since work constitutes a large slice of the time most people spend on earth, decent work can be seen as a fundamental dimension of quality of life. Specific aspects and cultural perceptions of decent work may vary from country to country and person to person and it is not possible to fully agree upon a uniform set of measurements for decent work; however, some concepts and their basic elements are considered universal in the twenty-first century. These include fundamental principles and rights at work such as being free from mistreatment, having workers’ representation and enjoying rights of collective action. Further key values include fair compensation, social security, job safety, a safe and healthy work environment, decent working hours, a good work-life balance, fulfilling and meaningful work, and opportunities for personal development (Ghai, Citation2003; Nizami & Prasad, Citation2017; Pereira et al., Citation2019).

The ILO Decent Work Agenda was first published in 1999 and was further developed with subsequent publications, manuals and interpretation guidelines (ILO, Citation1999, Citation2002, Citation2008, Citation2013, Citation2018a, Citation2022). In addition to being an important objective itself, it has now been included in the official sustainable development agenda of the ILO, UN, EU and many other international organisations. This demonstrates that decent and fair work, a key component of UN Sustainable Development Goal 8, is a central objective and contributor to sustainable development without high levels of poverty and unemployment. Since it was first developed, the Decent Work Agenda has been formalised and operationalised into a series of indicators which are understood as benchmarks or standards of decent work around the world. In its updated formulation, decent work is defined with 11 substantive indicators (ILO, Citation2013, p. 12): (1) Employment opportunities, (2) Adequate earnings and productive work, (3) Decent working time, (4) Combining work, family and personal life, (5) Work that should be abolished, (6) Stability and security of work, (7) Equal opportunity and treatment in employment, (8) Safe work environment, (9) Social security, (10) Social dialogue, employers’ and workers’ representation, (11) Economic and social context for decent work.

Due to the limited scope and length of this article, we have chosen to discuss the following six indicators: (1) Adequate earnings and productive work, (2) Decent working time, (3) Combining work, family and personal life, (4) Safe work environment, (5) Social security, (6) Social dialogue & employers’ and workers’ representation.

These indicators encompass the core elements of decent work and establish the foundation for a minimal set of conditions that define the basics of decent work particularly pertinent to the field of translation. Based on these six indicators, an analysis is performed on questionnaire data from 48 translation workers living in Turkey and working with platforms. Subsequent sections outline the questionnaire methodology and present the findings.

3. Methodology and limitations

The online questionnaire was prepared in English using Qualtrics and underwent a pilot phase with five translators to enhance clarity and coherence. The distribution strategy employed the snowball method during December 2022 and January 2023, where the survey was initially shared within our network in Turkey and expanded further by participants sharing it with others. The questionnaire encompassed a comprehensive list of 65 questions and variables derived from previous literature and existing questionnaires on working conditions (such as Fairwork, Citation2022; Ferraro et al., Citation2018; Fırat, Citation2019; ILO, Citation2018a, Citation2018b, Citation2021; Pesole et al., Citation2018; Urzí Brancati et al., Citation2020). Due to limitations of space, only a subset of questions and visuals are presented in this article, with the intention to report additional details in subsequent publications.

Participants were required to be over 18, have at least six months of translation work experience, have worked with at least one platform, and have received payment for their translation work. In selecting suitable platforms for the study, we primarily relied on the NIMDZI language technology atlas (NIMDZI, Citation2022), which catalogues translation/translator marketplaces and platform language service providers such as Proz, Smartcat, Translated, Gengo, and Stepes. Notably, we excluded online translation tools like Smartling, Crowdin, and Phrase as they function solely as translation production tools without an internal or external marketplace. Recognising the growing prominence of broader service platforms, we also included platforms like Fiverr, Upwork, and Freelancer.com into our study. To eliminate potential ambiguity with translation management systems/portals such as Plunet and XTRF, we implemented various measures to confirm platform eligibility within the study's scope. The questionnaire, along with the call and information sheet, provided precise details about platforms. Participants were presented with a reference list to select platforms they work with, and we explicitly communicated that those not engaged with relevant platforms should refrain from completing the questionnaire.

In acknowledgment of the inherent limitations posed by our research methodology, particularly with the use of snowball sampling, we proactively took steps to mitigate potential self-selection bias. Our approach involved sourcing initial participants from diverse channels, articulating clear inclusion criteria and prioritising participant anonymity to encourage a diverse range of respondents. The study also recognised challenges associated with the dynamic platform economy, such as non-representativeness, response reliability, and anonymity concerns. To address these issues, we employed key screener questions as filters to ensure the inclusion of individuals with specific attributes relevant to the study. Quality control measures included attention test questions to identify suspicious answers and exclude respondents who failed these checks.

4. Decent work in focus: analysing study findings through indicators

4.1. Demographics, professional background and platform engagement

The study covers a diverse profile of participants in terms of basic demographics, professional background, and platform engagement. The age distribution revealed that 44% (n = 21) fell within the 25–34 age group, while 50% (n = 24) were between 35 and 64 years old. Two participants were 18–24, and one was above 65. In terms of gender, 67% (n = 32) identified as female, and 33% (n = 16) as male. Household composition varied, with 37.5% (n = 18) of participants reporting 1–3 people in their households, depending on their earnings. Education levels were predominantly high, with 73% (n = 35) having a university or equivalent education and 23% (n = 11) holding postgraduate degrees such as MA or PhD. One participant had completed high school, and another had some college education.

Concerning employment status, a majority of participants (80%, n = 39) identified translation as a full-time profession, with 62% (n = 30) defining themselves as full-time freelancers, self-employed, or contracted. Some participants (12.5%, n = 6) had fixed salaries in translation or non-translation companies, and a small percentage (4%, n = 2) were students. Additionally, three participants (6%) were small business owners, and one was a stay-at-home parent who also worked as a freelance translator. Regarding professional experience, 54% (n = 26) had been working in the translation industry for over ten years, 29% (n = 14) for five to ten years, and the remaining 17% (n = 8) for one to five years. For 94% of respondents, the primary service offered was translation, while 4 participants offered editing, copywriting, and subtitling as their main services. A majority (80%, n = 39) usually translate from/into English-Turkish, with some participants translating from other languages such as Kurdish, German, Spanish, Romanian, Russian, Uzbek, and Dutch.

Almost all participants are highly experienced in working with platforms, with approximately half (n = 23) having worked with platforms for five to ten years. 13% (n = 6) over ten years and 36% (n = 17) one to five years. Only two participants had less than one year of experience with platforms. The frequency of engagement with platforms varied, but was predominantly high, as 79% (n = 38) reported working with platforms very frequently, frequently, or occasionally, while 21% (n = 10) indicated rare or very rare engagement. Notably, platforms have become full-time workplaces for 43% (n = 21) of participants. 21% (n = 10) spent more than five days per week working on platforms and 23% (n = 11) four to five days. 17% (n = 8) spent between two to three days with platforms and 40% (n = 19) less than two days per week.

Frequency of time on platforms also varied depending on the platform’s model. Naturally, platforms with an integrated CAT tool (Smartcat, Unbabel, Gengo, etc.) were used more frequently than platforms without one (Proz, Fiverr, Upwork, etc.), in which case translation workers usually work outside the platform to produce translations. The reasons for working with platforms included the desire to work with international clients and earn foreign currency (63%, n = 30), freelancing from home (46%, n = 22), having control and flexibility over jobs (42%, n = 20), finding direct clients (42%, n = 20), meeting client requirements (33%, n = 16), and complementing income from other jobs (25%, n = 12). A few participants highlighted that income from platforms was better than salary-based employment due to poor working conditions in their previous jobs or the need to earn money while studying.

When describing their clients on platforms, participants reported working mostly with translation agencies from abroad (65%, n = 31) and local ones (27%, n = 13). Additionally, they engaged with direct clients from abroad (25%, n = 12) and local direct clients (8%, n = 2). Since there are commonly multiple types of clients on platforms, participants were allowed to choose multiple options in this question. For 70% (n = 33) of participants, platform earnings were either an essential (40%, n = 19) or important (30%, n = 14) component of their income, while 27% (n = 13) considered it nice to have but not crucial. 38% (n = 18) reported earning over 50% of their translation income from platforms. 32% (n = 15) earned between 50% and 10% of their translation income from platforms. For 23% (n = 11) of respondents, this proportion was between 9% to 1% of their translation income.

4.2. Adequate earnings and productive work

According to ILO (Citation2013, p. 85), the focus of adequate earnings should be on the percentage of workers with low pay. To measure adequate earnings and productive work, ILO (Citation2013, p. 85) recommends looking at poverty lines and minimum wages by considering any changes in minimal living standards and effects of inflation on welfare.

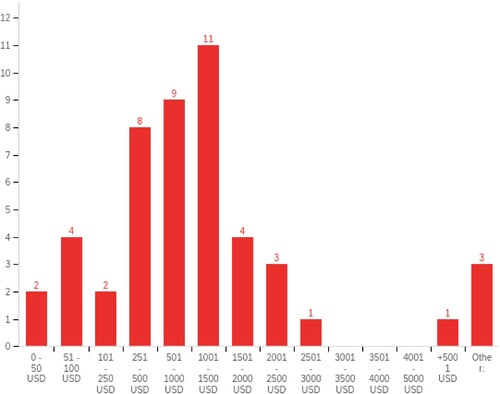

The income of participants from both translation work in general and platforms in particular reveals concerning results. Although the majority possess extensive experience and serve as full-time workers in the translation industry, as illustrates, 35% (n = 17, including others) of participants were able to earn up to $Footnote1500/month from translation work in general, 19% (n = 9) fall within the $501–1,000 range, and 23% (n = 11) earn between $1,001–1,500. A mere 8% (n = 4) reported an income surpassing $2,000 and only two participants reported an income above $2,501 from translation work.

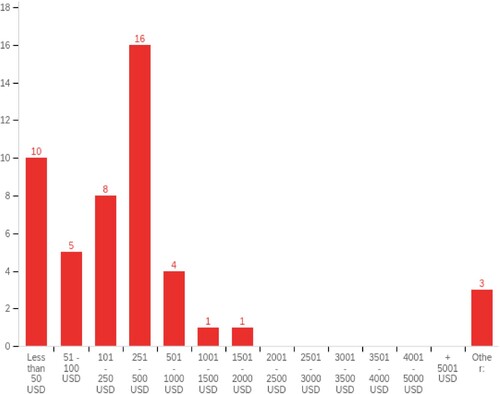

focuses on platform-based income, revealing that while it constitutes a crucial or significant portion of earnings and has transitioned into full-time or part-time occupations for many, a notable 81% (n = 39) of participants are limited to earning a maximum of $500/month from platforms. Additionally, 62% (n = 30) of participants expressed difficulty finding well-paying jobs on platforms, emphasising it being a prevalent challenge.

Substantial expenses also weigh on participants, as 71% (n = 34) allocate a significant portion of their income to accommodation, and 71% (n = 34) spend up to 50% of their income on work-related expenses. Additionally, 50% (n = 24) of participants pay state or private health insurance, with 71% (n = 34) reporting no free training from platforms in the last 12 months, incurring extra costs and time on work-related development.

One of the biggest labour unions in Turkey, BİSAM (Citation2023), report that the poverty line for a family of four (two adults, two children) is set at around $1,500/month in January 2023.Footnote2 This indicates that regardless of the number of household members, 77% (n = 37) of participants fell below this threshold that covers minimum expenses for food, education, health, accommodation, entertainment, heating and transportation. At that same time, BİSAM (BİSAM, Citation2023) had established a starvation line at approximately $450 per month, covering only essential food expenses. This indicates that approximately 35% (n = 17) of participants fell within this threshold. Also, around 37.5% (n = 18) of respondents financially support 1–3 dependents, and among them only 28% (n = 5) exceed the poverty line.

Different unions have varied perspectives on minimum living costs per person, with Türk-İş (Citation2023) suggesting a minimum amount of $600/month/person in January 2023. Examining the translation earnings of participants who did not report dependents, 40% (n = 12) could earn up to $500, falling below the minimum living cost or the state-defined minimum wage of $450 per person. Moreover, regardless of family size, around 65% (n = 31) reported translation income above the state-defined minimum wage ($450/month/person), yet significantly below market wages in many OECD countries.

Despite the majority of participants having extensive translation experience and working full-time in the field, our data reveals that a significant proportion faces financial difficulties. When benchmarked against established poverty lines and minimum living standards, the findings indicate that a substantial number of participants fall below these thresholds. Furthermore, it appears that income from platforms does not adequately contribute to their overall earnings. When assessed against key decent income indicators as outlined in various ILO conventions (ILO, Citation1949, Citation1970) and manuals (ILO, Citation2013, p. 65), the high level of inadequate income from both translation work and platforms suggests most participants may be unable to ensure economic and mental well-being for themselves and their families with only their translation and platform income.

4.3. Decent working time

In the exploration of decent working conditions among participants, another crucial aspect is the enhancement of working time, a key indicator outlined by ILO (Citation2013, p. 91). This dimension encompasses various time-related considerations, including standards defining limits on working hours, minimum weekly rest periods, and the provision of paid annual leave. The ILO (Citation2013, p. 91) emphasises that adequate pay and productive work can be indirectly reflected through indicators on working hours, highlighting those working long hours due to insufficient pay or facing limitations resulting in inadequate income.

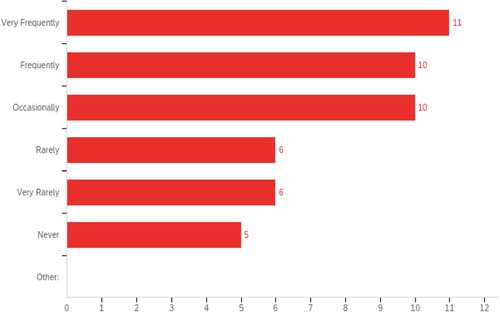

An examination of excessive working hours, defined as working beyond the maximum standard of 48 h per week according to ILO conventions (ILO, Citation1919, Citation1930), reveals another concerning trend among participants. As suggests, only a mere 10% (n = 5) never worked more than 48 h/week, while a substantial 65% (n = 31) reported working over 48 h per week with varying frequency, including 23% (n = 11) very frequently, 21% (n = 10) frequently, and 21% (n = 10) occasionally.

Similar to weekly work hours, the findings indicate that only 8% (n = 4) never work more than eight hours a day. In contrast, a significant number, 57% (n = 27) exceed eight hours a day, of which 17% (n = 6) frequently, 13% (n = 8) very frequently, or 27% (n = 13) occasionally. Moreover, 81% (n = 39) have worked beyond standard working hours after 18:00 h, with 31% (n = 15) doing so frequently, 27% (n = 13) very frequently, and 23% (n = 11) occasionally. Only one participant did not need to work during public/official holidays/weekends while over 83% (n = 40) found themselves working during public holidays or weekends frequently (33%, n = 16), very frequently (27%, n = 13), or occasionally (23%, n = 11). Also, inquiry into paid annual leave demonstrates the financial difficulties translation workers face in terms of being able to afford a break from work. A mere 23% (n = 11) indicated no difficulty in affording a standard four-week break per year. In contrast, a substantial 42% (n = 20) reported financial constraints that hinder their ability to take such a break, with an additional 31% (n = 15) highlighting the necessity to compensate for time off by working hard before or after their holiday period.

Questionnaire results reveal that many respondents surpass relevant ILO work hour conventions (ILO, Citation1919, Citation1930), struggling to make a living while working excessively (over 48 h/week, 8+ hours/day, during holidays/weekends, and after 18:00). Despite high time dedication to work throughout the week and day, their earnings indicate inadequate compensation for this dedication (see Section 4.2), with at least half of the respondents still expressing the need to work even more for their livelihoods. The ILO (Citation2013, pp. 95–98) warns that such prolonged and antisocial work hours may threaten health, disrupt work-life balance, and often signal inadequate pay, reduced productivity, job satisfaction, and motivation.

4.4. Combining work, family and personal life

Another key indicator of the ILO decent work examines work, family, and personal life by focusing on the proportion of workers facing the dual burden of professional responsibilities and family commitments (ILO, Citation2013, p. 106).

The excessive and atypical working hours of translators, extending into evenings, nights, and weekends/holidays reported in section 4.3. may contribute to the difficulties in maintaining their family life, friendships, relationships, and navigating emergencies or the care of family members, partners, or friends. Beyond professional obligations, participants also highlighted additional regular responsibilities, such as care work, including cooking and/or housework (92%, n = 43), and the nurturing and/or education (home-schooling) of family members (29%, n = 14). Regarding the interplay of working hours with family or social commitments outside of work, a diverse perspective emerged among participants. 37% (n = 18) of participants said their working hours fit well with family or social commitments outside work, while for 48% (n = 30) it was moderately (27%, n = 13) or slightly well (21%, n = 10), and not well for 15% (n = 7).

Maternity protection and parental leave stand out as other crucial considerations in this complex balance between work and family responsibilities. ILO’s definition (Citation2013, p. 109) emphasises the critical role of such leave in safeguarding the health of individuals and their children, facilitating recovery from childbirth, and allowing dedicated time for nurturing family bonds. However, a mere 10% (n = 5) of participants felt financially equipped to take an 18-week (4.5 months) break during the year, which would be in accordance with the time frame specified for maternity and parental leave according to ILO conventions (ILO, Citation2000b, Citation2000a).

These findings indicate potential limitations faced by participants in allocating sufficient time and resources to non-work activities. Despite the anticipated benefits of flexible work arrangements, such as freelancing and remote work, the prevalence of excessive and unusual working hours contradicts the need for a healthy work-life balance. This may not only blur the boundaries between private and professional life but also has the potential to disrupt social engagements and personal time. Additionally, the low percentage of participants feeling financially prepared for the recommended 18-week maternity and parental leave highlights the need for comprehensive policies and support systems to promote a more sustainable and balanced integration of work, family, and personal life within freelance translation work on platforms. The questionnaire data also suggests that, despite the challenges of long working hours, a notable proportion of participants still value the flexibility afforded by freelancing compared to traditional work arrangements.

4.5. Safe work environment

Ensuring a safe work environment is integral to the concept of decent work, as outlined by ILO (Citation2013, p. 154). This involves not only physical safety but also addressing psycho-social risks to prevent the development of health problems among workers. The present study investigated the psycho-social and physical health conditions and well-being of participants.

In terms of psycho-social health, a substantial 75% (n = 36) of participants have encountered frequent (50%, n = 24) or occasional (25%, n = 12) work-related stress in the last 6–12 months, stemming from factors such as time pressure, workload, and task complexity. Many reported experiencing various psycho-social health issues, including poor sleep quality (68%, n = 32), frequent tiredness (68%, n = 32), reduced energy levels (66%, n = 31), difficulty concentrating on work (64%, n = 30), decreased productivity (51%, n = 24), heightened negative thoughts (49%, n = 23), anxiety (45%, n = 21), loss of interest in once-enjoyable activities (43%, n = 20), trouble sleeping (38%, n = 18), increased sleep duration (38%, n = 18), feelings of inadequacy or failure (34%, n = 16), mild depression (21%, n = 10), moderate depression (15%, n = 7), relationship breakdowns (13%, n = 6), thoughts about suicide (9%, n = 4), appetite loss (9%, n = 4) and severe depression (4%, n = 2).

Regarding physical health, nearly all participants experienced one or more forms of work-related health issues. The prevalent problems included back pain (81%, n = 38), headaches (62%, n = 29), and neck pain (60%, n = 28). Other reported physical issues encompassed carpal tunnel syndrome (17%, n = 8), gastric ulcers (11%, n = 5), hypertension (4%, n = 2), metabolic arthritis (4%, n = 2), sleep deprivation and vision disorders (2%, n = 1), cardiovascular disease (2%, n = 1) and diabetes (2%, n = 1).

In essence, the assessment of the work environment as per ILO conventions (Citation1981a, Citation1985, Citation2006) highlights a prevalence of various psycho-social and physical health issues among participants. Notably, these health concerns could be attributed to prolonged work hours, poor work-life balance, low income, occupational stress, and the sedentary nature of translation work. The findings underscore the urgent need to address the physical and psycho-social well-being of translation workers, as work-related factors and/or poor lifestyle choices could contribute to the prevalence of health issues among participants.

4.6. Social security

Social security, recognised as a fundamental human right by ILO (Citation2013, p. 169), serves as a vital safety net, offering income security to navigate life's significant risks and mitigate poverty. A close examination of the participants’ social protection measures reveals conspicuous gaps in both accessibility and coverage.

Out of all participants, 15% (n = 7) reported lacking health insurance altogether, indicating a significant portion without this essential form of coverage. 50% (n = 24) took personal responsibility to pay for their health insurance, with 31% opting for state insurance and 19% investing in private health insurance. Merely 25% (n = 13) enjoyed national health insurance provided by the state at no cost, while only 17% (n = 9) benefited from employer-paid insurance. Additionally, six participants supplemented their state insurance with private coverage, and two participants relied on their families’ health insurance. When considering retirement planning, the data reveals that a substantial 65% (n = 31) of participants were not actively saving for their future. Moreover, more than 80% (n = 39) expressed concerns about the adequacy of their income during old age. Only a mere 8% (n = 4) felt financially protected in the event of an extended inability to work due to unforeseen circumstances.

Despite ILO’s (Citation1952) emphasis on social security as an inherent right to be ensured without discrimination, the findings indicate that many participants face obstacles in accessing free social security measures. As defined by ILO (Citation2013, p. 169), these measures are designed to safeguard individuals from various vulnerabilities, including income loss due to sickness, disability, maternity, employment injury, unemployment, old age, or the death of a family member. The gaps in social security coverage, coupled with participants’ widespread doubts and anxieties about their future and retirement, demonstrate the pressing need for comprehensive and accessible social security measures for translation workers as a basic human right.

4.7. Social dialogue, representation and workplace democracy

As highlighted to be an important component of ILO decent work indicators (Citation2013, p. 190), social dialogue, representation and workplace democracy play a pivotal role in fostering a workplace where workers and employers can engage in meaningful conversations about work-related matters. This indicator illuminates the existence of worker rights and democratic values, including accountability, discussion, collective bargaining, votes, and consent within the workplace.

None of the participants reported belonging to any trade or labour union, a significant observation considering the fundamental right, as outlined by ILO conventions (ILO, Citation1948, Citation1981b), to have access to freedom of association, organisation, and collective bargaining. A mere 27% (n = 13) were affiliated with a translation association or organisation. This stark lack of trade union and translation association membership raises concerns about the absence of collective representation and negotiation for translators. 98% (n = 47) reported that platforms did not formally communicate with them about their willingness to recognise, or bargain with, a representative body of workers or trade union. Questions probing individual bargaining power revealed another disconcerting reality, since 80% (n = 38) agreed that competition on platforms resulted in low bargaining power with their clients, and 82% (n = 39) believed it led to an overall reduction in their rates.

Concerning the democratic governance within platforms, the survey results revealed a landscape where translation workers had minimal to no influence or participation in decision-making processes. A staggering 90% (n = 43) reported that platforms did not seek their opinion before implementing changes to terms and agreements of the platforms. Almost all participants (94–98%, n = 47-45) found it impossible to influence organisational structures, strategic plans, and decisions, indicating a lack of involvement in decision-making processes. Around 90% (n = 43) expressed not having a say in improving working conditions on platforms.

The findings reveal a stark disparity between the principles of social dialogue, worker's voice, workplace democracy, and the reality faced by translation workers on platforms. The absence of trade union membership among participants raises concerns about the collective representation and negotiation capabilities of translation workers. The lack of collective bargaining, exacerbated by platform competition, is a noteworthy issue, with a majority of participants experiencing diminished bargaining power and reduced rates. Within platforms, participants face a landscape of minimal to no influence or participation in decision-making processes and work conditions, which reflects a critical gap in democratic governance.

4.8. Summary and discussion

In summary, the findings suggest that even though the majority of participants in this study works full-time in the translation industry with extensive experience, and relies heavily on platforms for earnings, a significant portion of participants fall below the threshold of earning sufficient translation income to meet basic living standards, especially considering the elevated cost of living in Turkey. A substantial majority find themselves below the poverty line defined by labour unions in the country. Additionally, work-related expenses and lack of future work and income opportunities through training and education further compounds the financial struggles of many translation workers. The findings also reveal excessive and unusual working hours endured by almost all respondents, surpassing relevant ILO conventions. This may not only jeopardise the physical and mental well-being of translation workers but also disrupt work-life balance, signalling potential inadequacies in pay and reduced productivity. Despite the perceived flexibility of freelancing, the prevalence of long working hours introduces challenges that may impact personal time and social engagements. The study also reveals a significant prevalence of work-related stress and psycho-social health issues among participants including poor sleep quality, fatigue, decreased productivity, anxiety and mild to severe depression, along with physical health problems such as back and neck pains and headaches. The gaps in social security coverage and widespread anxieties about the future emphasise the urgent necessity for comprehensive and accessible social security measures as a fundamental human right. Furthermore, the findings indicate a disparity between the working conditions on translation platforms and the principles of social dialogue, worker’s voice and workplace democracy. The current digital workplaces fall short in supporting democratic governance and recognising the collective bargaining power of representative bodies or trade unions for translation workers. This deficiency is exacerbated by the competitive nature of platforms, contributing to a decline in individual bargaining power and resulting in an overall reduction in translation rates.

The identified obstacles, such as inadequate earnings, excessive working hours, and financial struggles, can potentially compromise the quality of translation work. Translation workers facing economic stress and enduring long working hours may find it challenging to maintain the high level of creativity, precision, attention to detail, and linguistic nuances required in their tasks. The observed threats to the physical and mental well-being of translation workers, including health concerns and disrupted work-life balance, may lead to burnout, diminished life quality and reduced productivity. Workers dealing with these challenges may struggle to maintain focus, efficiency, and job satisfaction, directly impacting their ability to deliver high-quality translation outputs.

If the current adverse labour conditions persist, the translation industry may face difficulties in retaining and attracting skilled translation professionals. Translation workers experiencing financial strain, limited income and growth opportunities, and inadequate social security measures may seek alternative career paths or industries with more favourable working conditions. The industry’s reputation may also be at stake if translation workers continue to face exploitative and unsustainable working conditions. This could raise ethical concerns, impacting how clients and stakeholders perceive the integrity and reliability of translated content. The industry’s commitment to fair labour practices, social responsibility and adherence to international standards can be questioned. Considering the predominant female workforce in the translation industry and among questionnaire respondents, substandard working conditions could disproportionately affect women, potentially worsening existing gender-based inequalities and reinforcing patriarchal dynamics. Similarly, given that platforms are a crucial income source for translators from the Global South working with platforms originating in the Global North (ILO, Citation2021, p. 44), these conditions may contribute to the exacerbation of historical inequalities rooted in colonialism.

5. Conclusions

By conducting a quantitative analysis of a subset of questionnaire results, this study centred on assessing the alignment of translation workers’ labour conditions with the ILO’s principles of decent work. The findings indicate that translation workers in Turkey, particularly those engaged in the platform economy, experience labour conditions that fall short of meeting the six fundamental decent work standards defined by ILO. While platforms have facilitated easy access to translation work globally, the analysis reveals prominent challenges related to aspects such as adequate earnings, decent working hours, work-life balance, occupational safety, social security, and social dialogue, representation and workplace democracy. These decent work indicators are based on ILO conventions that are legally binding for many UN states and necessary for maintaining basic human rights, well-being, and sustainable development goals. This implies that a significant portion of translation workers in Turkey might be exposed to working conditions that are exploitative and unsustainable, which infringes upon fundamental human rights.

As articulated through ILO conventions and recommendations, translation workers should benefit from labour and social protection rights, irrespective of their contractual status, workplace or country of birth. According to ILO (Citation2021, p. 237), this means that employers, business owners and policy makers are responsible for ensuring decent and fair work for workers ‘because they can materially influence their working conditions’. ILO’s conventions and Decent Work Agenda have been put into practice with centuries of struggles and discussions over human and labour rights, and they still define basic statutory universal employment rights. Therefore, a truly emancipatory development in the twenty-first century of work should prioritise improved, not worsened, work conditions.

The techno-political developments of our century include platform business models that integrate various language tools such as artificial intelligence and machine translation, and promise convenience, efficiency and global accessibility for various translation and communication services. Nevertheless, human involvement still remains a crucial part of digital translation work. However, beneath the surface of expected progress, translation workers are confronted with an array of adversities and risks that have been altering the nature and sustainability of the translation profession fundamentally, rather than allowing them to fully enjoy the benefits of digitisation. Translation workers have long been operating as freelancers even prior to the advent of platforms, without access to employment conditions such as minimum wage, pensions, paid leave, or guaranteed benefits. The critical distinction in the current platform context appears to be a matter of scale, with precarious work conditions and the absence of traditional employment benefits becoming more pronounced as the platform economy continues its worldwide expansion, launching in its wake increasingly complex and tech-powered labour control mechanisms.

Considering the historical importance of translation as an integral component of societal, economic, and technological development, it is imperative to address these challenges and establish conditions that foster the well-being and fair treatment of translation workers, whether on platforms or traditional workplaces. Therefore, this study calls for further research that explores the labour conditions of translation workers and alternative business models from around the globe in conjunction with policies geared to achieve decent, fair, democratic and sustainable translation work.

Acknowledgements

We express our heartfelt appreciation to the respondents who participated in the questionnaire, the anonymous reviewers, and the diligent journal editors for their invaluable contributions to this work. A special thanks to Prof Constantin Orasan, Dr Graham Hieke and Jo Nean for their support and significant contributions for this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Gökhan Fırat

Gökhan Fırat is a postgraduate researcher at the University of Surrey's Centre for Translation Studies, focusing on the working conditions of translation workers, particularly on digital labour platforms and in translation cooperatives. With over a decade of experience in the publishing and translation industries, Gökhan worked in various roles such as book translator, editor, project coordinator, operations manager, business development manager and technology consultant. Gökhan holds a BA in translation and interpreting and completed his MA in translation studies, concentrating on the impact of the current techno-political transformations on translation and its workers.

Joanna Gough

Joanna Gough holds an MA in english philology from Adam Mickiewicz University, Poland and an MA in translation from the University of Surrey. In 2016 she received her PhD in the area of information behaviour of professional translators. Shortly after that, she was appointed as a lecturer in translation studies at the University of Surrey. Joanna's research interests encompass a variety of language and technology-related subjects, such as tools and resources for translators, process-oriented translation research, technology-supported collaborative translation and many more. With an interest in the business and industry aspects of the translation profession, she is a keen advocate of cooperation between academia and industry. Joanna is a member of the ITI Professional Development Committee and a LocLunch Ambassador.

Joss Moorkens

Joss Moorkens is an associate professor at the School of Applied Language and Intercultural Studies at Dublin City University (DCU), a science lead at the ADAPT Centre and a member of DCU's Institute of Ethics and Centre for Translation and Textual Studies. He has written on the topics of translation technology, machine translation, translation quality evaluation, translator precarity and translation ethics. He is the general coeditor of translation spaces with Prof. Dorothy Kenny and co-ditor of a number of books and journal special issues. He is also a co-author of the textbooks Translation Tools and Technologies (Routledge 2023) and Automating Translation (Routledge 2024).

Notes

1 $ = USD.

2 In January 2023, the starvation line was approximately 8,782 TRY and the poverty line was 30,379 TRY in Turkey, with an exchange rate of $1 = 19 TRY. Due to inflation and currency fluctuations, these figures are updated monthly. By January 2024, after a year, $1 equaled around 30 TRY, with the starvation line at 15,033 TRY ($500) and the poverty line at 51,998 TRY ($1,750).

References

- Baumgarten, S., & Bourgadel, C. (2023). Digitalisation, neo-Taylorism and translation in the 2020s. Perspectives, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/0907676x.2023.2285844

- Baumgarten, S., & Cornellà-Detrell, J. (2017). Introduction. Target. International Journal of Translation Studies, 29(2), 193–200. https://doi.org/10.1075/target.29.2.001int

- BİSAM. (2023). Açlık ve yoksulluk sınırı Ocak 2023 dönem raporu [Starvation and poverty lines in Turkey January 2023 report]. DİSK/Birleşik Metal-İş Sınıf Araştırmaları Merkezi. https://www.birlesikmetalis.org/index.php/tr/guncel/basin-aciklama/1991-bisam-0123

- Blustein, D. L., Kenny, M. E., di Fabio, A., & Guichard, J. (2019). Expanding the impact of the psychology of working: Engaging psychology in the struggle for decent work and human rights. Journal of Career Assessment, 27(1), 3–28. https://doi.org/10.1177/1069072718774002

- Carreira, O. (2023). Market concentration in the language services industry and working conditions for translators. Perspectives, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/0907676x.2023.2214318

- CSA Research. (2020). The state of the linguist supply chain translators and interpreters in 2020. https://insights.csa-research.com/reportaction/305013106/Toc?SearchTerms=State%20of%20the%20Linguistic%20Supply%20Chain%202020

- Cukur, L. (2023). Towards an ethical framework for evaluating paid translation crowdsourcing and its consequences. The Translator, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/13556509.2023.2278226

- do Carmo, F. (2020). ‘Time is money’ and the value of translation. Translation Spaces, 9(1), 35–57. https://doi.org/10.1075/ts.00020.car

- Fairwork. (2022). Fairwork 2022 translation & transcription platform report. https://fair.work/en/fw/publications/fairwork-tt-report-2022/

- Ferraro, T., Pais, L., Rebelo, N., Santos, D., & Moreira, J. M. (2018). The decent work questionnaire: Development and validation in two samples of knowledge workers. International Labour Review, 157(2), 243–265. https://doi.org/10.1111/ilr.12039

- Fırat, G. (2019). Commercial translation and professional translation practitioners in the era of cognitive capitalism: A critical analysis [MA thesis]. Boğaziçi University. https://transint.bogazici.edu.tr/sites/transint.boun.edu.tr/files/582045.pdf

- Fırat, G. (2021). Uberization of translation. Impacts on working conditions. The Journal of Internationalization and Localization, 8(1), 48–75. https://doi.org/10.1075/jial.20006.fir

- Garcia, I. (2017). Translating in the cloud age: Online marketplaces. Hermes – Journal of Language and Communication in Business, (56), 59–70. https://doi.org/10.7146/hjlcb.v0i56.97202.

- Ghai, D. (2003). Decent work: Concept and indicators. International Labour Review, 142(2), 113–145. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1564-913X.2003.tb00256.x

- Giustini, D. (2024). ‘You can book an interpreter the same way you order your uber': (Re)interpreting work and digital labour platforms. Perspectives, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/0907676x.2023.2298910

- Gough, J., Temizöz, Ö, Hieke, G., & Zilio, L. (2023). Concurrent translation on collaborative platforms. Translation Spaces, 12(1), 45–73. https://doi.org/10.1075/ts.22027.gou

- ILO. (1919). Convention C001 - Hours of Work (Industry) Convention, 1919 (No. 1).

- ILO. (1930). Convention C030 - Hours of Work (Commerce and Offices) Convention, 1930 (No. 30).

- ILO. (1948). Convention C087 - Freedom of Association and Protection of the Right to Organise Convention, 1948 (No. 87).

- ILO. (1949). C095 - Protection of Wages Convention, 1949 (No. 95). In NORMLEX (No. C095).

- ILO. (1952). Convention C102 - Social Security (Minimum Standards) Convention, 1952 (No. 102).

- ILO. (1970). C131 - Minimum Wage Fixing Convention, 1970 (No. 131). In ILO (No. C131).

- ILO. (1981a). C155 - Occupational Safety and Health Convention, 1981 (No. 155).

- ILO. (1981b). Convention C154 - Collective Bargaining Convention, 1981 (No. 154).

- ILO. (1985). C161 - Occupational Health Services Convention, 1985 (No. 161).

- ILO. (1999, June). Report of the director-general: Decent work. In 87th International labour conference. International Labour Office, Geneva. https://www.ilo.org/public/english/standards/relm/ilc/ilc87/rep-i.htm

- ILO. (2000a). Convention C183 - Maternity Protection Convention, 2000 (No. 183).

- ILO. (2000b). Recommendation R191 - Maternity Protection Recommendation, 2000 (No. 191).

- ILO. (2002). Measuring decent work with statistical indicators (No. 2).

- ILO. (2006). C187 - Promotional Framework for Occupational Safety and Health Convention, 2006 (No. 187).

- ILO. (2008). Measuring decent work: Tripartite meeting of experts on measurement of decent work. International Labour Organisation.

- ILO. (2013). Decent work indicators: Guidelines for producers and users of statistical and legal framework indicators (Vol. 2). https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---dgreports/---integration/documents/publication/wcms_229374.pdf

- ILO. (2018a). Decent work in the platform economy. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---dgreports/---ddg_p/documents/publication/wcms_728139.pdf

- ILO. (2018b). Digital labour platforms and the future of work: Towards decent work in the online world. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---dgreports/---dcomm/---publ/documents/publication/wcms_645337.pdf

- ILO. (2021). World employment and social outlook 2021: The role of digital labour platforms in transforming the world of work. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---dgreports/---dcomm/---publ/documents/publication/wcms_771749.pdf

- ILO. (2022). Decent work in the platform economy. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_norm/---relconf/documents/meetingdocument/wcms_855048.pdf

- Jiménez-Crespo, M. A. (2017). Crowdsourcing and online collaborative translations (Vol. 131). John Benjamins Publishing Company.

- Lambert, J., & Walker, C. (2022). Because we’re worth it. Translation Spaces, 11(2), 277–302. https://doi.org/10.1075/ts.21030.lam

- Moorkens, J. (2020a). “A tiny cog in a large machine”: Digital taylorism in the translation industry. Translation Spaces, 9(1), 12–34. https://doi.org/10.1075/ts.00019.moo

- Moorkens, J. (2020b). Translation in the neoliberal era. In E. Bielsa & D. Kapsaskis (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of translation and globalization (pp. 323–336). Taylor and Francis Inc. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003121848-27

- NIMDZI. (2022). Language technology atlas - list of translation marketplaces and platforms. https://www.nimdzi.com/nimdzi-language-technology-atlas-2022/

- Nizami, N., & Prasad, N. (2017). Decent work: Concept, theory and measurement. Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-2194-7_27.

- OECD. (2020). Digital transformation in the age of COVID-19: Building resilience and bridging divides, digital economy outlook 2020 supplement. www.oecd.org/digital/digital-economy-outlook-covid.pdf.

- Olohan, M. (2017). Technology, translation and society. Target. International Journal of Translation Studies, 29(2), 264–283. https://doi.org/10.1075/target.29.2.04olo

- Pereira, S., dos Santos, N., & Pais, L. (2019). Empirical research on decent work: A literature review. Scandinavian Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 4(1), https://doi.org/10.16993/sjwop.53

- Pesole, A., Urzí Brancati, M. C., Fernández-Macías, E., Biagi, F., & González Vázquez, I. (2018). Platform workers in Europe: Evidence from the COLLEEM survey.

- Sadek, G. (2018). Translation: Rights and agency: A public policy perspective for knowledge, technology and globalization [Doctoral dissertation]. University of Ottawa. https://ruor.uottawa.ca/server/api/core/bitstreams/9cf2efad-b8b6-4a76-bf67-84d8b4c30b84/content

- Şahin, M., & Gürses, S. (2023). A call for a fair translatiosphere in the post-digital era. Parallèles, 1–17.

- Şahin, M., & Oral, S. B. (2021). Translation and interpreting studies education in the midst of platform capitalism. Journal of Specialised Translation, (36), 276–300. https://khazna.ku.ac.ae/en/publications/translation-and-interpreting-studies-education-in-the-midst-of-pl.

- TÜRK-İŞ. (2023, January). Açlık ve yoksulluk sınırı [Starvation and poverty lines in Turkey]. https://www.turkis.org.tr/ocak-2023-aclik-ve-yoksulluk-siniri/.

- Urzí Brancati, M. C., Pesole, A., & Fernández-Macías, E. (2020). New evidence on platform workers in Europe: Results from the second COLLEEM survey. Publications Office of the European Union. https://doi.org/10.2760/459278

- Zwischenberger, C. (2023). Online collaborative translation: Probing its suitability as a meta-concept and its exploitative potential linked to labour/work. In C. Zwischenberger & A. Alfer (Eds.), Translaboration in analogue and digital practice. Transkulturalität - translation - transfer (Vol. 57, pp. 213–241). Frank & Timme. https://doi.org/10.57088/978-3-7329-9036-8_9.