ABSTRACT

In Geneva, Switzerland, students in secondary 1 education are grouped into different tracks according to their academic level. The tracking system in Geneva has been reformed recently. Prior to the reform, the tracks were very hierarchical but less selective; following the reform, the tracks are still very hierarchical but the entry criteria are more selective and there is greater flexibility to move from one track to another. Using longitudinal data, this article compares these two types of tracking system and analyses the inequalities produced in terms of the skills acquired by students and the path taken once compulsory education is completed. Our analysis shows that the new tracking system following the reform has a major impact on students of medium ability. They are more likely being assigned to a lower track, which has a significant adverse impact on their learning and subsequent pathway through education.

Introduction

The question of how to organize secondary education is relevant in all educational contexts. But finding the right answer depends on national practices, the specific objectives of the secondary school system, and the educational ideas prevalent in each country. Separating students into tracks is one way of managing student diversity, while grouping them together in the same class is another. There are also many forms of tracking system, and their effects can be very varied. In this article, we will focus on these systems and the impacts of raising the requirements for entry into the highest tracks. For this, we have drawn from the article by Chmielewski et al. (Citation2013) entitled “Tracking Effects Depend on Tracking Type”. In this article, the authors set out three types of tracking: between-school streaming, within-school streaming, and course-by-course tracking. In our case study, we will focus on a system in which students are streamed within the same school. The effects of this type of system can vary greatly depending on the entry requirements for each track and whether it is possible to move from one track to another during schooling. The aim of this article is therefore to analyze the effects of changing how the tracking system is organized. We studied two cohorts of students who entered secondary school before and after the tracking system was reformed in the canton of Geneva, Switzerland. Officially, the aim of the reform was to make education more suited to the needs of students, while addressing educational inequalities and maintaining high expectations, especially in the higher track. We looked at the effects of raising the requirements for entry into the higher track on students’ schooling and academic skills. More specifically, the aim is to examine the impact it had on students of average ability who, as a result of the reform, were unable to access the higher track.

Tracking

There is no shortage of literature on the effects of tracking. But most of that literature looks at the impact tracking has on students in terms of equity and effectiveness. Based on the typology set out by Mons (Citation2007), there are two main types of school systems: integrated systems, where students are placed in heterogeneous classes, and a separation model, in which students are separated into different classes and/or schools based on their academic ability.

There are three main types of integrated systems (which are either “à la carte”, uniformed, or individualized integration systems), all of which have one long common track for all students. This is the case, for example, in Denmark, Iceland, and Sweden, as well as in Japan and South Korea. In the separation model, there is a shorter common track that ends when primary school is completed. From the start of their secondary education, students are assigned to separate tracks. This system is used in Germany, Austria, and Belgium, as well as in several Swiss cantons.

The model proposed by Mons (Citation2007) shows that when first tracking occurs later, the overall level of students tends to improve, the number of students with academic difficulties decreases, and academic inequalities between students and between schools as well as social disparities in academic achievement remain low. In streamed systems, the overall academic ability of students tends to be lower, with greater educational inequalities. This research is backed by a large number of international findings (e.g., Dupriez & Dumay, Citation2006; Gamoran & Mare, Citation1989; Gorard & Smith, Citation2004; Kerckhoff, Citation1986). All of these studies show that assigning students to lower tracks results in those students being academically weak relative to systems in which students are taught in heterogeneous groups. The research therefore demonstrates that placing students in homogeneous, low-level tracks can adversely affect the education of these students. Furthermore, these systems tend to produce social inequalities (Hanushek & Wößmann, Citation2006; Monseur & Crahay, Citation2008) which can be empirically defined as the link between a student’s social position and their academic results in terms of learning and educational pathway. Streaming students based on academic ability too early in their education tends, in the end, to increase school segregation by social and ethnic background. For example, Oakes (Citation1995) in the British context and Charmillot and Felouzis (Citation2020) in Switzerland show a link between a selection on the basis of academic criteria and social and ethnic segregation at school. This doubles the disadvantage for these students over the long term, and it means that they do not have the same opportunities in terms of post-compulsory education. Gamoran and his colleagues (Citation1995) also showed that schools choose to separate students into different units according to their academic level in a search for academic efficiency. The aim of this logic is to allow schools to achieve their objectives more easily by allocating “separated tasks to specialized subunits” (p. 688). In other words, grouping students in homogeneous tracks according to their academic level should enable the academic differences between peers to be considered more effectively, in particular by providing adapted teaching. This is a principle inspired by organizational theory that considers that in a heterogeneous environment, productivity and effectiveness can be improved by segmentation in structurally homogeneous units. Applied to schooling, this logic has its limits because students are considered to be “raw materials of the school system”. Yet dividing students is far from being a “neutral act” (p. 689). Selecting students based on their academic level almost mechanically causes a distinction according to social, cultural, and racial/ethnic criteria. Therefore, tracked systems prove to be problematic, since their effectiveness goals contradict objectives of equity.

However, these findings are not as clear-cut as they may first appear. The Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) surveys (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development [OECD], Citation2016) show, for example, that France is one of the OECD countries with the highest correlation between students’ performance at 15 years of age and their social background (Felouzis, Citation2020). And yet the French school system is integrated, with one long common track of heterogeneous classes up to the end of lower secondary education. But France also has a very high level of segregation between schools (e.g., Felouzis et al., Citation2019; Ly & Riegert, Citation2015). Segregation in any form – be it through tracking or differences among schools – therefore produces major inequalities. Experimental research has shown that, under certain conditions, streaming students into homogeneous tracks does not affect their education (e.g., Duflo et al., Citation2011; Slavin, Citation1987, Citation1990, Citation1993).

These latest findings indicate that there are other factors, besides tracking, that can cause inequalities. How tracking is done also has an impact (Chmielewski, Citation2014). This is supported by Mons (Citation2007): “The concept of a comprehensive school can lead to different – and even contradictory – results” (p. 132). Tracking can also be advantageous for students, provided that the quality of education and the academic requirements remain the same (Slavin, Citation1990). The main reason why students in low tracks do not develop the same skills as other students is that they do not have the same learning opportunities (Gamoran, Citation1986). In addition, the social representation of different tracks can have non-cognitive effects, particularly for students in the lowest tracks (Müller & Hofmann, Citation2016). Van Houtte et al. (Citation2012) show that students in a vocational track have lower self-esteem than those in an academic track. The gaps are particularly large in multilateral schools.

Being placed in a low track has an impact on students’ motivation and engagement (Carbonaro, Citation2005). However, the results of research into the non-cognitive effects of tracking are still the subject of debate. Chmielewski et al. (Citation2013) demonstrated, for example, that low-ability students in systems with course-by-course streaming had lower levels of self-esteem than students in fully tracked systems. This is because those students were constantly being compared with academically stronger students, and this had a negative impact on their self-representation.

Another process that explains the negative impact of orientation in a low track is the expectations developed by teachers. There is a long tradition of research in this area. From the work of Rosenthal and Jacobson (Citation1968), to more recent studies (Friedrich et al., Citation2015; Jamil et al., Citation2018), research shows that teachers’ subjective perception of students’ competencies guides classroom teaching practices and student motivation. This ultimately influences their learning outcomes (Jamil et al., Citation2018). These teacher perceptions and expectations depend on multiple factors. They may be linked to stereotypes related to gender (Wang, Citation2012), social background, or minority background (van den Bergh et al., Citation2010). However, these expectations also depend on the organizational context, including whether students belong to a particular grade group or stream (Kelley & Finnigan, Citation2003; Smith & Shepard, Citation1988). Teachers thus develop lower expectations for students in low or medium tracks comparatively to students in a high track.

In the end, two apparently contradictory types of results emerge from the literature on the effects of tracking. A first set of results, based on large-scale surveys, tend to show that tracking reinforces learning inequalities by offering students in different pathways unequal contexts, expectations, programs, and teachers (e.g., Dupriez & Dumay, Citation2006; Felouzis & Charmillot, Citation2013; Gamoran & Mare, Citation1989; Gorard & Smith, Citation2004; Hanushek & Wößmann, Citation2006; Kerckhoff, Citation1986; Monseur & Crahay, Citation2008). A second set of results, based on experimental methods, show positive effects of tracking on the overall level of learning and on the reduction of inequalities. To solve this puzzle, we consider that experimental research measures the specific effects of tracking. In these studies, for example, teachers are drawn by lot to teach in a stream with high or low requirements (e.g., Duflo et al., Citation2011; Slavin, Citation1987, Citation1990, Citation1993), pedagogical goals are explicitly focused on student progress, and expectations of students are high in all streams. In this case, social processes that interfere with the functioning of pathways are eliminated, according to the principles of experimental methods. The situation is quite different in large-scale surveys which simultaneously measure the effects of the pedagogical precepts of tracking (providing pupils with learning adapted to their academic level) and their concrete interaction with other social facts: social segregation linked to orientation processes, composition effects, lower expectations from teachers for pupils in streams with low requirements, differentiated level of teacher training according to the track in which they teach, and so forth. It is for these different reasons that we can argue that there is enough consistency in the research findings based on large-scale survey to suggest that tracking systems tend to increase social inequalities in terms of the skills acquired by students and to reduce the academic performance of the students in the lowest tracks.

The supply of education is not the same for all students in these systems, and this is what heightens educational inequalities and results in students in lower tracks acquiring fewer academic skills. However, since tracking systems can take various forms, more precision is required. In Switzerland, Felouzis and Charmillot (Citation2013) have shown that the different tracking systems used in Swiss cantons are relatively diverse, and, as a result, they also vary in terms of their impact on the skills acquired by students.

This diversity of tracking types will be the focus of this article. More specifically, we will look at the effects of the educational reform introduced in Geneva in 2011. This reform brought in several major changes to the tracking system. First of all, the tracking system was made more selective, especially in terms of the entry requirements for the high track. In the light of the literature, we can therefore assume that the reform will increase inequalities, particularly between students in the middle and higher tracks. However, the reform also sought to increase flexibility by creating gateways between tracks and making it possible for students to repeat a year so that they could be moved up to a higher track.

Our research sought to gain insight into the effects of this reform by looking at two aspects. First, we analyzed what happened when the tracking system became more selective but also more flexible, with more possibilities to move from one track to another during the school year or at year-end. To answer our question as to whether this reform increases social inequalities, we first looked at whether this affected all students in the same way and whether it increased social inequalities. We then sought to gain more insight into the effects of having stricter entry requirements for the high track. Our analysis focused on students who were adversely affected by the reform, that is, those who ended up in the middle track because the entry requirements for the high track became stricter. We also looked at whether being in the middle track (rather than the high track) had an adverse effect on the skills acquired by the end of lower secondary education and, over the longer term, on the path taken by students after completing their compulsory education.

Secondary education reform in Geneva

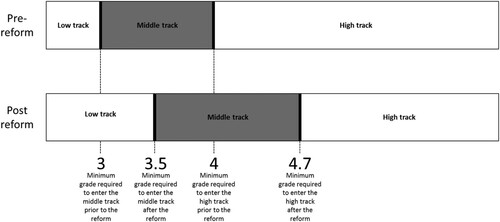

Geneva’s three-track lower secondary school system (known as the cycle d’orientation) was first introduced in the 1970s. Although it has been reformed several times, it is still organized in much the same way as it was when it was first created. It comprises a low track, a middle track, and a high track. We will focus on the 2011 reform, which changed the entry conditions for the different tracks, with stricter requirements for the middle and high tracks. illustrates the changes in the entry requirements for the high track.

In Switzerland, grades are on a 6-point scale, where 1 represents the lowest possible grade and 6 represents the highest possible grade and the average is 4. Prior to the reform, students could enter the high track if they obtained a grade of at least 4 out of 6 in each of three core subjects, based on the average grade obtained for coursework and in the end-of-year exams. Following the reform, students are still required to obtain these minimum grades, but they must also have at least 14 points across all core subjects.Footnote1 As a result, students need a higher average grade to enter the high track, as shown in . In addition, the reform introduced more gateways for students to change tracks.

There is a system that allows the best students in a given track to move to a more demanding track. However, this transition can be difficult for some students who have been following a different curriculum often for several months, and have to catch up quickly. Schools offer students extra classes for this purpose. Students can also move up a track by repeating a year. The introduction of these gateways between tracks has had an impact on the pathways in secondary 1 education. Prior to the reform, it was easier to enter the high and middle track, but afterwards most of the changes between tracks were towards a less demanding track. The reform reversed the trend: It became more difficult to enter directly into the high and middle tracks, but at the same time, it led to a sharp increase in changes towards a more demanding track.

Once they have finished their lower secondary education, most students in Geneva go on to do some form of post-compulsory training. The three main forms are:

Upper secondary school (or high school): an academic education that prepares students for direct entry into a university or other higher education institution;

General education: a curriculum that prepares students for further studies in areas such as health care, social work, communications, and applied arts;

Vocational training: often referred to as “apprenticeship-based” training, it provides students with the know-how they need for a given trade. It is designed to prepare students for rapid entry into the job market.

Students who complete the high track in lower secondary education can enter any of the tracks available in post-compulsory education. Most of these students decide to go to high school, which is the most demanding and most prestigious of the three options (between 70% and 75%, depending on the year). For students in the middle track, access to post-compulsory training is much more restrictive. To be admitted to high school, students in the middle track must have an overall average of 5 or more and be strong in mathematics and French. It is extremely rare for them to go to high school because they usually do not meet the criteria for entry into this training. The majority of these students go on to do either general education or vocational training (more or less 57%, depending on the year). Students in the low tracks cannot enter high school. They can only enter general education under very restrictive conditions (in fact, very few of them are able to do so). Some can enter vocational training (sometimes with an entry test). The majority are oriented towards a non-degree course (more or less 53%). The secondary education reform has not changed the guidance criteria.

Research questions and hypotheses

We hypothesize that inequalities result not from the fact that the system is tracked but rather from how the system is organized and how lower ability students are taken into consideration. The Geneva reform is an interesting case because it allows us to compare two tracking systems: Prior to the reform, the tracks were very hierarchical but less selective; following the reform, the tracks are still very hierarchical but the entry criteria are more selective and there is greater flexibility to move from one track to another. We can therefore compare these two types of tracking system and analyze the inequalities produced in terms of the skills acquired by students and the path taken once compulsory education is completed.

More precisely, two questions will be addressed with this analysis:

| (1) | What is the overall effect of the reform? Our goal is to see whether the reform has led to changes in students’ educational pathways. To do so, we analyze whether the reform has had an impact on the track being followed in the 1st and 3rd years of lower secondary school, on the path taken between the 1st and 3rd years of lower secondary school, and on the post-compulsory track taken. Our hypothesis is that, while the reform has changed the pathways in lower secondary education, it has not changed the orientations in post-compulsory education. | ||||

| (2) | What is the effect of the reform on “borderline” students? As we saw earlier, the 2011 reform raised the minimum threshold for entering the highest track (see ). Students with grades around that minimum threshold were the ones most affected by this stricter requirement. A student who would have just made it into the high track before the reform would have been placed in the middle track after the reform. Our hypothesis, based on the mobilized literature, was that these borderline students were the ones most impacted by the reform. Preventing them from entering the high track would have an impact on their entire education thereafter. To test this hypothesis, we analyze the effect of the reform on the skills acquired by the end of lower secondary education and on the path taken into post-compulsory education. | ||||

Methods

Data

The data used for our analyses come from the school database of the Geneva Public Education Department (DIP), which keeps track of students when they enter the canton’s education system. The data are updated every year, making it possible to monitor students throughout their education in the Canton.

This study is based on the longitudinal monitoring of two cohorts of students from their entry (more specifically, from their 1st year in secondary education, to account for students who repeated a year) into lower secondary education until the 2nd year of their post-compulsory training. The study therefore covers a period of 5 years (or up to 7 years for those who repeated one or more years). The first cohort is made up of students who started their secondary education prior to the reform, in the 2010–2011 school year (N = 4,099). The second cohort comprises students who started their secondary education after the reform, in the 2011–2012 school year (N = 4,100).

Variables in the study

Dependent variables

In this study, the effect of the reform was estimated with two outcome variables:

The skills acquired by the end of compulsory secondary education were measured by the students’ mathematics scores in the standardized tests (known as the EVACOM) taken at the end of lower secondary education. These tests aim to assess the knowledge and skills acquired by students relative to the learning outcomes defined in the curriculum.

The path taken into post-compulsory education was measured by a dichotomous variable, which distinguished between students who went to high school, which offers the highest level of training and paves the way to go to university, and those who did not.

Independent variables

Our analysis included six dependent variables:

Gender was measured through a variable made of two categories: male and female.

Social background of students was measured using socioprofessional category (SPC), which was determined based on the parents’ professions. Fifteen initial groups were combined into three categories for the purposes of the analysis: privileged SPC (senior managers), average SPC (staff, middle managers, and small-business owners/self-employed individuals), and disadvantaged SPC (blue-collar workers, miscellaneous, and no profession indicated).

Student’s first language was measured using a categorical variable that differentiates between French speakers (i.e., students who have French as their first language) and non-French speakers.

Academic ability at the end of primary school was measured by the students’ grades (their annual average on a scale of 1 to 6) attributed by teachers for French and mathematics. We used either the average grades for these two subjects or only the grade in mathematics when looking specifically at academic performance in that subject.

The variable “level-appropriate age” compares the student’s actual age with the theoretical age of students in that year of study. This enabled us to distinguish between students who were at the appropriate level given their age and students who were older than the appropriate age (this mainly involved students who repeated a year).

The variable “reform” indicates whether the student began secondary school before or after the reform was implemented.

Table 1. Sociodemographic characteristics of students.

Participants

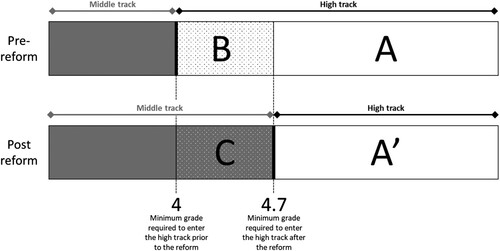

Our analysis focused on “borderline” students (i.e., students whose grades are close to the minimum threshold to enter a given track) – that is to say, those most affected by the reform. More specifically, we looked at two categories of students ().

Figure 2. Secondary school tracking based on students’ academic ability at the end of primary education.

The first category comprises students who were not (or would not have been) affected by the reform. These are the students with the highest level of academic ability, who, regardless of the system in place, would always go into the high track. More specifically, it is made up of:

Group A (N = 1,844): students from Cohort 1 (pre-reform) who entered the high track. Given their school grades, if they had entered secondary school a year later, after the stricter requirements had been brought in, they would still have gone into the high track.

Group A’ (N = 2,083): students in Cohort 2 (post-reform) who entered the high track. If they had entered secondary school a year earlier, before the reform was brought in, they would have met the requirements for entry into the high track.

The second category comprises the student who ended up – or would have ended up – in a different track as a result of the reform. More specifically, it comprises the students who were on the borderline between the high and middle tracks. It is made up of:

Group B (N = 754): students who entered the high track before the reform but who would have been placed in the middle track based on the post-reform entry requirements. These students were therefore placed in a higher track than they would have been if they had entered secondary school after the reform. It is worth noting that some of these students were granted exemptions allowing them to enter the high track based on their school grades. These exemptions have all but disappeared since the reform.

Group C (N = 426): students who entered secondary school after the reform and went into the middle track. However, on the basis of their grades at the end of primary school, they would have been placed in the high track if they had entered secondary school prior to the reform. In other words, these students were placed in a lower track than they would have been prior to the reform. These are the students who were adversely affected by the reform.

This analysis is centered on students in the middle-high track. There was also interest in what happened to students in the middle-low track. However these results have not been presented in this article because, given the small numbers of pupils considered (189 pupils before the reform and 104 pupils after the reform), it was unfortunately not possible to carry out regression analysis that would allow a robust estimate of the effect of the reform.

Descriptive statistics of the sociodemographic makeup of the groups are presented in . It shows that, within Groups B and C (i.e., the students who ended up or would have ended up in the middle track rather than the high track as a result of the reform), there were proportionately more students with characteristics that are negatively correlated with academic success. These include students from modest backgrounds, boys, and students whose first language is not French. This greater academic selectivity, brought in to provide students with an education that is more adapted to their abilities, therefore also resulted in greater social selectivity. This could also mean that the reform had an impact on these students in terms of their post-compulsory education and the skills acquired by the end of compulsory education.

Table 2. Sociodemographic characteristics of the groups.

Analysis strategy

We first measured the overall effect of the reform by comparing the orientations and educational pathways of the entire population of students enrolled before (N = 4,099) and after the reform (N = 4,100).

We then focused on borderline students to estimate the effect of the reform in two areas: the skills acquired by the end of compulsory secondary education and the path taken into post-compulsory education. To do this, we conducted multivariate linear and logistic regression analyses to determine the effect of the reform after controlling for the students’ sociodemographic and academic characteristics. Burris and Welner (Citation2005) adopted a relatively similar analytical approach to study the effects of the detracking reform that occurred in the Rockville Centre School District (Long Island) in the late 1990s.

Skills acquired at the end of lower secondary education

The aim was to analyze the effect of the reform on the skills acquired by the students by the end of compulsory education. We focused on the students’ mathematics scores in the standardized tests taken at the end of lower secondary education. These tests are standardized in terms of their content, pass requirements, correction methods, and grading scale. However, their difficulty varies depending on the track taken. They nevertheless all have a common section that all students must take, so that the results from each track can be compared.

The problem with using these standardized mathematics tests is that they are not designed based on item response theory, which does not allow for direct comparison of the scores of the two cohorts. With item response theory, some test items are used as anchors and are reused to make tests comparable from one year to the other. These anchor items should be kept secret so that comparisons are not invalidated by students’ and teachers’ knowledge of their content. In Geneva, however, all test items are made public, so their content is available to everyone. To get around this problem, we chose to focus on the difference in scores between the groups. Rather than comparing the raw scores for each group, the aim is to determine whether the reform contributed to widening the score gap between borderline students (Groups B and C) and those who were not affected by the reform (Groups A and A’).

For this, we calculated the difference in the scores of students in Group B relative to the average for Group A, and the difference in the scores of students in Group C relative to the average for Group A’.Footnote2 This analytical approach is inspired by studies on the “achievement gap”, which is defined as the difference in scores on standardized tests between different groups of students (Anderson et al., Citation2007).

We then conducted a multiple linear regression analysis on these differences in scores, with the “reform” variable included as a control. A significant effect of this variable would mean that the reform has had an impact on the differences in score. In absolute terms, this analysis reveals nothing about the mathematics results of students in Group C relative to those of the students in Group B. It does, however, enable us to assess whether the results of the students in Group C were closer to or farther from the average results for Group A’ than the results of the students in Group B were from the average for Group A prior to the reform. The existence of interaction effects was also tested in the model specification, but none of these effects were found to be statistically significant. Consequently, they were not included in the final models presented in this study in order to have models that are as parsimonious as possible.

Post-compulsory education

We looked at the type of post-compulsory education that students on the borderline between the middle and high tracks entered, and especially whether they went to high school or not. More specifically, we examined whether students in Group C, who were assigned to a lower track because of the reform, were less likely to go to high school than the students in Group B, who were at a similar level at the end of primary education but were assigned to the high track (). It should be noted that, although they were assigned to the middle track, the students in Group C received an education that was more adapted to their level of academic ability (this was the reason for the reform) and had more opportunities to move up a track (the reform made the tracks more flexible). They therefore did have the opportunity to move up to the high track, sometimes even very early on in their secondary education.

Here, we used a logistic regression model with the “reform” variable as a control to determine how this affects their probability of attending high school. The aim was to estimate the extent to which the probability of attending high school changed for two students with the same sociodemographic and academic characteristics, depending on whether they started secondary school before or after the reform, that is, whether or not they were initially assigned to the high track. Appendix 1 provides descriptive statistics for the variables used in the regression analysis. All of the continuous variables were standardized.

Results

The overall effects of the reform

To analyze the effects of the reform, we looked at:

the effects of the reform on the track being followed in the 1st and 3rd years of secondary school;

the effects of the reform on the path taken between the 1st and 3rd years of secondary school. We looked at whether the path was continuous, that is, whether it was difficult for students to change tracks or whether the reform had achieved its goal of making the tracks more flexible. For this, we looked at whether students who entered the middle track stayed there until the end of their secondary education or whether there were more changes between tracks, including both moves upwards into a more demanding track and moves downwards into a less demanding track;

the effects of the reform on the post-compulsory track taken.

illustrates that, after the reform, fewer students entered the high track in the 1st year of lower secondary education (78.5% pre-reform compared with 62.8% post-reform), with more students in the low and middle tracks.Footnote3 This more selective approach could also be seen in the 3rd year of lower secondary education, albeit to a lesser extent: 67% of the students in Cohort 2 were in the high track, compared with 71% prior to the reform. As expected, the reform therefore made the tracking system more selective.

Table 3. Secondary school tracks, and paths through lower secondary education and post-compulsory education.

The changes to the entry requirements for the three tracks also had an impact on students’ pathways through lower secondary education. As planned, it made the tracking system more flexible. There was an increase in the number of students changing tracks: The percentage of students changing tracks between the 1st and the 3rd years of lower secondary education went from 16% to 28%. The direction of these pathways also changed. Prior to the reform, most of the changes in track were downwards, to a less demanding track (12.5% of students). Not many students (2.6%) moved to a higher track. After the reform, the percentage of students moving upwards had increased to 12.5%.

The paths taken by students in their post-compulsory education were very similar in both cohorts: Just over half of the students went on to high school (51.3% pre-reform compared with 52.7% post-reform), around 20% went into vocational training (20.4% pre-reform compared with 20.7% post-reform), around 13% went into general education (13.6% pre-reform compared with 13.3% post-reform), and around 13% joined migrant integration or employment integration programs (14% pre-reform compared with 12.6% post-reform).

The reform also had a limited impact in terms of inequalities. There was very little change in the Cramer’s V measuring the link between the selected post-compulsory education and social background: It was .224 before the reform and .205 after the reform (p < .001). The same was true for the link between post-compulsory education and migratory status (.116 before the reform versus .135 afterwards) and gender (.225 and .249, respectively).

In sum, our analysis shows that the reform had a major impact on the secondary school track assigned to students and their pathway through lower secondary education. Before the reform, the system was less selective upon entry into secondary education, and students were then moved to a lower track if necessary. The reform changed this model. The new system is more selective at the start of secondary education, as it is more difficult to enter the middle and high tracks. At the same time, there is now greater flexibility, and students can be moved between tracks – and especially to a higher track – at any time.

However, the reform did not have a significant impact on the paths taken by students after compulsory secondary education: Students went into the various post-compulsory education options much as they had before, and there was no real change in the extent of inequalities.

At first glance, it may seem surprising that the reform had no impact on the paths taken by students after completing their compulsory education. However, while there was little impact overall, this may hide starker differences within certain categories of students. To determine whether certain students may have been affected more by the reform, we analyzed the impact of the stricter entry requirements for the high track.

Effects of the reform on the skills acquired by the end of compulsory education for borderline students

Until now we have analyzed the overall effect of the reform; we now measure the impact of the reform on the skills acquired by students who were placed in a lower track than they would have been placed in prior to the reform (i.e., Group C). We looked at whether the difference in the scores of students in this group relative to the average for Group A’ was greater than the difference in the scores of students in Group B relative to the average for Group A.

shows that the students’ sociodemographic (i.e., gender, social background, and first language) had no significant impact. However, being older than the level-appropriate age had a positive and significant impact (beta: .5; p < .001), in that being older due to late starts, interrupted schooling, or grade repetition led to a greater difference in the scores of students in Groups B and C relative to the reference Groups A and A’. The initial academic level had a negative and significant impact: the higher a student’s grade in mathematics at the end of primary school, the smaller the difference in scores at the end of lower secondary school (beta: .710; p < .001).

Table 4. Linear regression – difference in results from the average of the reference group for students in Groups B and C at the end of lower secondary school.

Regarding the impact of the reform, the positive coefficient shows that the reform has contributed to widening the score gap for borderline students. Indeed, the difference in the scores of students in Group C relative to Group A’ is 8.3% of a standard deviation higher than the difference in the scores of students in Group B relative to Group A (beta: .083; p = .006). This means that the reform made the situation worse for students in Group C: Being assigned to the middle track from the outset meant that their results by the end of their lower secondary education are further away from the average results of the reference group than those of the same students who had entered secondary education prior to the reform and were instead assigned to the high track.

Effects of the reform on the educational pathway in post-compulsory education for borderline students

The analysis showed that all the variables used in the model had a statistically significant effect on the probability of going to high school (). The sign of each coefficient was in line with our expectations. For the same academic level, students from a privileged social background increased the probability of entering high school (positive coefficients). Conversely, being male, being older than the level-appropriate age at the end of primary school, and coming from a disadvantaged social background were all characteristics that reduced the probability of entering high school (negative coefficients). The only less intuitive positive effect was that associated with the student’s first language, as students whose first language is not French were more likely to go to high school than students whose first language is French. This can largely be explained by the fact that many of the students in Groups B and C with French as their first language were students who experienced greater academic difficulties.

Table 5. Effects of sociodemographic characteristics, of academic ability at the end of primary school, and of the reform on the probability of going to high school.

With regard to the effect of the reform, we observed that students with the same sociodemographic and academic characteristics (particularly in terms of their academic ability at the end of primary school) were less likely to go to high school if they started their lower secondary education in the middle track. This means that, all other things being equal, students who entered a lower track as a result of the reform did indeed have less of a chance of getting into high school at the end of compulsory education than similar students who were assigned to the high track prior to the reform. The odds ratio associated with the “reform” variable quantifies this phenomenon: All other things being equal, a student in Group B was 1.37 times more likely to go to high school than a similar student in Group C.

Discussion

This article provides insights on several levels. For the purposes of our analysis, we decided to focus on students whose placement in one of the lower secondary school tracks was directly affected by the reform, that is, students who are academically average. These students represent only a small proportion of the students in the canton, but by focusing on this group, we were able to more closely analyze the effects of the reform, which made it more difficult to enter the track that eventually leads to high school. Our analysis shows that while a reform of this type can have very little impact on the school population as a whole, it can have a major impact on students that share certain characteristics. Our aim was therefore to determine what consequences these stricter entry conditions have on the education of medium-ability students and to put forward hypotheses to explain this.

Our methodology involved comparing two groups: Group B comprised students who entered the high track prior to the reform and who, based on their grades, would have been placed in another track after the reform; Group C was made up of students who entered a lower track after the reform but would have been placed in the high track prior to the reform.

Our analysis showed a significant, albeit relatively small, effect of the reform on students’ skills at the end of lower secondary school. All other things being equal, the achievement gap between students in Group C and those not affected by the reform (i.e., students with the highest level of academic ability) is wider than the pre-reform achievement gap between students in Group B and high achievers. As a result, students in Group C were less likely to be admitted to high school. In other words, for students deemed to be of medium ability at the end of primary school, being assigned to a lower track had a significant adverse impact on their learning and subsequent pathway through education.

We would like to put forward two hypotheses to explain these findings. The first is that expectancy effects had an impact on teaching. Students in Group B were categorized as high-potential and those in Group C as medium-potential, which meant that they were not taught in the same way and followed less ambitious teaching programs. These expectancy effects, which were first brought to light within social psychology in the 1960s (Rosenthal & Jacobson, Citation1966), and which now constitutes a long tradition of research (Friedrich et al., Citation2015; Jamil et al., Citation2018; Kelley & Finnigan, Citation2003), explain how assigning students to a low, medium, or high group can affect their progression. They point to one of the shortcomings of wanting to adapt teaching to the students’ level. In other words, ability grouping, at the center of adaptation strategies in the so-called differentiated pedagogy, does not generally promote either equity or efficiency (Duru-Bellat & Mingat, Citation1997; Grisay, Citation1993; Merle, Citation1998; Mingat, Citation1991).

A second hypothesis, which does not contradict the first, is that there was a composition effect, which can be defined as the impact that the overall academic ability and social and ethno-racial makeup of the class has on learning and ambition. The students in Group C were taught in classes where the average socioeconomic and academic level was lower than for the students in Group B. This hypothesis is supported by studies such as the meta-analysis conducted by van Ewijk and Sleegers (Citation2010). Research on educational effectiveness has shown that the weakest students are also the most sensitive to the effect of the schooling context (Bressoux, Citation1994; Duru-Bellat, Citation2003; Duru-Bellat & Mingat, Citation1997). Recent studies (Petrucci & Roos, Citation2020) have shown that in Geneva at the end of compulsory schooling, students in the middle track appeared to be less motivated than their peers in the high track and were more subject to truancy. They also showed less positive attitudes towards school, had less confidence in their academic abilities, and considered themselves less able to cope with learning difficulties. They also have, on average, a greater sense of loss of control over their own lives.

But to what extent does each of these hypotheses explain our findings? To determine this, we would have to conduct an ad hoc analysis of the data in order to separate out these two potential sources of inequality and their impact on students’ learning and educational path.

Finally, it is worth considering whether there is a link between our findings and the initial objectives of the reform studied in this article. The legislators’ aim was to limit access to the high track in order to improve the academic level of the students in that track. And this aim was achieved, based on the situation 1 year after the reform was brought in: there were fewer students in the high track, and their academic level was higher than before the reform. But the price for this was that medium-ability students probably acquired fewer skills and did not progress as well in their education. In other words, the improvement in the overall level of students in the high track was achieved through a process of selection rather than as a result of an improvement in the teaching provided.

The findings of this study must be seen in light of some limitations. The first is that our analysis focuses on the effects of the reform for students in the middle and higher track. To fully understand the effect of this reform, it would be relevant to also analyze its effects on dynamics between the lowest and middle track. The second limitation is that our analysis focuses on the orientation towards high school. However, this is not the only way to access higher education. In Switzerland, students who follow a vocational training in upper secondary education can obtain a Federal Vocational Baccalaureate, which then gives access to universities of applied science. It would therefore be pertinent to examine how the reform has influenced the orientation towards a vocational training.

Acknowledgement

This article came out of the research project entitled “How to organize secondary education in Switzerland”, which received funding from the Swiss National Science Foundation (project No. 100019_156702/1).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Franck Petrucci

Franck Petrucci is a researcher at the Research in Education Service of the Canton of Geneva (Switzerland). His research focuses on measuring the contextual effect on students’ performance.

Barbara Fouquet-Chauprade

Barbara Fouquet-Chauprade, PhD, is a senior lecturer and researcher at the Faculty of Psychology and Educational sciences, University of Geneva (Switzerland). Her work focuses on the design, the implementation, and the effects of education policies, on educational inequalities, and on school segregation and priority education policies.

Samuel Charmillot

Samuel Charmillot, PhD, is a lecturer and researcher at the Faculty of Psychology and Educational sciences, University of Geneva (Switzerland). His research focuses on the links between the organization of education systems, school segregation, and educational inequalities.

Georges Felouzis

Georges Felouzis, PhD, is a full professor at the Faculty of Psychology and Educational sciences, University of Geneva (Switzerland). His research focuses on education policies in Switzerland and France, on educational inequalities, and on international comparisons in education.

Notes

1 To simplify matters, shows the entry requirements as an overall average. In reality, students must meet both of the requirements indicated, that is, they have to obtain a grade of at least 4 in each of the three core subjects AND a grade of at least 14 for the three subjects combined. So a student who obtains a grade of 4.25 in each of the three subjects (making a total of 12.75 points) would not be allowed to enter the high track. The entry conditions for the middle track have also been strengthened with the reform. Prior to the reform, students could enter the middle track if they obtained a grade of at least 3 out of 6 in each three core subjects. After the reform, it is necessary to obtain a grade of at least 3.5 in the core subjects and to score at least 11.5 points for the three subjects combined.

2 We calculated the difference in the standardized score and in absolute terms to determine the standard deviation of the students in Groups B and C from the average for Groups A or A’.

3 Before the reform, there was a system of heterogeneous classes in some schools (this concerns about 500 students in three different schools). In these schools, classes were completely heterogeneous in first grade. As a result, these students are not included in . In third grade, however, classes were not entirely heterogeneous: There were ability groups for mathematics and German. Using these ability groups, the Geneva Public Education Department (DIP) officially defined students’ profiles corresponding to the different tracks (DIP, Citation2011): Students with a high level in mathematics or German were assigned to the high track. Those who did not have a high level in one of the two subjects were assigned to the middle track.

References

- Anderson, S., Medrich, E., & Fowler, D. (2007). Which achievement gap? Phi Delta Kappan, 88(7), 547–550. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/003172170708800716

- Bressoux, P. (1994). Note de synthèse. Les recherches sur les effets-écoles et les effets-maîtres [Summary note. Research on school effects and teacher effects]. Revue Française de Pédagogie, 108, 91–137.

- Burris, C. C., & Welner, K. G. (2005). Closing the achievement gap by detracking. Phi Delta Kappan, 86(8), 594–598. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/003172170508600808

- Carbonaro, W. (2005). Tracking, students’ effort, and academic achievement. Sociology of Education, 78(1), 27–49. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/003804070507800102

- Charmillot, S., & Felouzis, G. (2020). Modes of grouping students, segregation and education inequalities. A longitudinal analysis of a cohort of students in Switzerland. Revista Iberoamericana sobre Calidad, Eficacia y Cambio en Educación, 18(4), 31–56. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.15366/reice2020.18.4.002

- Chmielewski, A. K. (2014). An international comparison of achievement inequality in within- and between-school tracking systems. American Journal of Education, 120(3), 293–324. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1086/675529

- Chmielewski, A. K., Dumont, H., & Trautwein, U. (2013). Tracking effects depend on tracking type: An international comparison of students’ mathematics self-concept. American Educational Research Journal, 50(5), 925–957. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831213489843

- Département de l’Instruction Publique. (2011). Après la scolarité obligatoire. Edition 11/12 [After compulsory education. 11/12 issue].

- Duflo, E., Dupas, P., & Kremer, M. (2011). Peer effects, teacher incentives, and the impact of tracking: Evidence from a randomized evaluation in Kenya. American Economic Review, 101(5), 1739–1774. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.101.5.1739

- Dupriez, V., & Dumay, X. (2006). Inequalities in school systems: Effect of school structure or of society structure? Comparative Education, 42(2), 243–260. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/03050060600628074

- Duru-Bellat, M. (2003). Les apprentissages des élèves dans leur contexte: Les effets de la composition de l’environnement scolaire [Students’ learning in context: The effects of the composition of the school environment]. Carrefours de l’éducation, 16(2), 182–206. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3917/cdle.016.0182

- Duru-Bellat, M., & Mingat, A. (1997). La constitution de classes de niveau dans les collèges: Les effets pervers d’une pratique à visée égalisatrice [The construction of level classes in secondary schools: The perverse effects of a practice that aims to equalize]. Revue Française de Sociologie, 38(4), 759–789.

- Felouzis, G. (2020). Les inégalités scolaires [Educational inequalities] (2nd ed., collection “Que-sais-je”). Presses Universitaires de France.

- Felouzis, G., & Charmillot, S. (2013). School tracking and educational inequality: A comparison of 12 education systems in Switzerland. Comparative Education, 49(2), 181–205. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/03050068.2012.706032

- Felouzis, G., Fouquet-Chauprade, B., & Charmillot, S. (2019). School segregation in France: The role of public policies and stakeholder strategies. In X. Bonal & C. Bellei (Eds.), Understanding school segregation: Patterns, causes and consequences of spatial inequalities in education (pp. 29–44). Bloomsbury Academic.

- Friedrich, A., Flunger, B., Nagengast, B., Jonkmann, K., & Trautwein, U. (2015). Pygmalion effects in the classroom: Teacher expectancy effects on students’ math achievement. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 41, 1–12. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2014.10.006

- Gamoran, A. (1986). Instructional and institutional effects of ability grouping. Sociology of Education, 59(4, 185–198. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/2112346

- Gamoran, A., & Mare, R. D. (1989). Secondary school tracking and educational inequality: Compensation, reinforcement, or neutrality? American Journal of Sociology, 94(5), 1146–1183. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1086/229114

- Gamoran, A., Nystrand, M., Berends, M., & Lepore, P. C. (1995). An organizational analysis of the effects of ability grouping. American Educational Research Journal, 32(4), 687–715. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3102/00028312032004687

- Gorard, S., & Smith, E. (2004). An international comparison of equity in education systems. Comparative Education, 40(1), 15–28. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/0305006042000184863

- Grisay, A. (1993). Le fonctionnement des collèges et ses effets sur les élèves de sixième et de cinquième [The functioning of junior high schools and its effects on sixth and fifth graders] (Education et Formations: Les Dossiers, No. 32). Ministère de l'éducation nationale.

- Hanushek, E. A., & Wößmann, L. (2006). Does educational tracking affect performance and inequality? Differences- in-differences evidence across countries. The Economic Journal, 116(510), C63–C76. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0297.2006.01076.x

- Jamil, F. M., Larsen, R. A., & Hamre, B. K. (2018). Exploring longitudinal changes in teacher expectancy effects on children’s mathematics achievement. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education, 49(1), 57–90. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5951/jresematheduc.49.1.0057

- Kelley, C. J., & Finnigan, K. (2003). The effect of organizational context on teacher expectancy. Educational Administration Quarterly, 39(5), 603–634. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0013161X03257299

- Kerckhoff, A. C. (1986). Effects of ability grouping in British secondary schools. American Sociological Review, 51(6), 842–858. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/2095371

- Ly, S. T., & Riegert, A. (2015). Mixité sociale et scolaire et ségrégation inter- et intra-établissement dans les collèges et lycées français [Social and academic mix and between and within school segregation in French middle and high schools]. Conseil national d’évaluation du système scolaire.

- Merle, P. (1998). L’efficacité de l’enseignement [Teaching effectiveness]. Revue Française de Sociologie, 39(3), 565–589. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/3322985

- Mingat, A. (1991). Expliquer la variété des acquisitions au cours préparatoire: Les rôles de l'enfant, la famille et l’école [Explaining the diversity of learning in the first grade: The roles of the child, the family and the school]. Revue Française de Pédagogie, 95, 47–63.

- Mons, N. (2007). Les nouvelles politiques éducatives: La France fait-elle les bons choix? [The new educational policies: Is France making the right choices?]. Presses Universitaires de France.

- Monseur, C., & Crahay, M. (2008). Composition académique et sociale des établissements, efficacité et inégalités scolaires: Une comparaison internationale [Academic and social composition of schools, efficiency and school inequalities: An international comparison]. Revue Française de Pédagogie, 164, 55–66. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.4000/rfp.2128

- Müller, C. M., & Hofmann, V. (2016). Does being assigned to a low school track negatively affect psychological adjustment? A longitudinal study in the first year of secondary school. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 27(2), 95–115. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09243453.2014.980277

- Oakes, J. (1995). Two cities’ tracking and within-school segregation. Teachers College Record, 96(4), 681–690.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2016). PISA 2015 results (Volume I): Excellence and equity in education. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264266490-en

- Petrucci, F., & Roos, E. (2020). Atteinte des compétences fondamentales dans le canton de Genève: Que nous enseignent les enquêtes COFO 2016 et 2017? [Achievement of core skills in the canton of Geneva: What do the 2016 and 2017 COFO surveys tell us?]. Service de la recherche en éducation.

- Rosenthal, R., & Jacobson, L. (1966). Teachers’ expectancies: Determinants of pupils’ IQ gains. Psychological Reports, 19(1), 115–118. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1966.19.1.115

- Rosenthal, R., & Jacobson, L. (1968). Pygmalion in the classroom: Teacher expectation and pupils’ intellectual development. Holt, Rinehart and Winston

- Slavin, R. E. (1987). Ability grouping and student achievement in elementary schools: A best-evidence synthesis. Review of Educational Research, 57(3), 293–336. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543057003293

- Slavin, R. E. (1990). Achievement effects of ability grouping in secondary schools: A best-evidence synthesis. Review of Educational Research, 60(3), 471–499. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543060003471

- Slavin, R. E. (1993). Ability grouping in the middle grades: Achievement effects and alternatives. Elementary School Journal, 93(5), 535–552. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1086/461739

- Smith, M. L., & Shepard, L. A. (1988). Kindergarten readiness and retention: A qualitative study of teachers’ beliefs and practices. American Educational Research Journal, 25(3), 307–333. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3102/00028312025003307

- van den Bergh, L., Denessen, E., Hornstra, L., Voeten, M., & Holland, R. W. (2010). The implicit prejudiced attitudes of teachers: Relations to teacher expectations and the ethnic achievement gap. American Educational Research Journal, 47(2), 497–527. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831209353594

- van Ewijk, R., & Sleegers, P. (2010). Peer ethnicity and achievement: A meta-analysis into the compositional effect. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 21(3), 237–265. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09243451003612671

- Van Houtte, M., Demanet, J., & Stevens, P. A. J. (2012). Self-esteem of academic and vocational students: Does within-school tracking sharpen the difference? Acta Sociologica, 55(1), 73–89. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0001699311431595

- Wang, M.-T. (2012). Educational and career interests in math: A longitudinal examination of the links between classroom environment, motivational beliefs, and interests. Developmental Psychology, 48(6), 1643–1657. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027247