Abstract

The increasing popularity of radical right, anti-immigrant, neo-nationalist movements can be seen as a response to super-diverse and complex migration and globalization processes challenging the ideology of the ‘nation-state’ and the traditional education system. Based on the question of how English is increasingly viewed as a threat to Swiss national languages and identities, this study presents data from Switzerland, often portrayed as the ideal multilingual country. Such a challenge was nevertheless confirmed through the qualitative analysis of 38 in-depth interviews conducted with students and teachers at three secondary schools in three language regions, policy makers, and open-ended questions from 94 student questionnaires. Language education policies have divided the educational landscape into certain regions prioritizing English over a national language and others adhering to the traditional curriculum. The data reveal strong ideological beliefs, lacking intranational communication, and personal as well as societal struggles of positioning based on linguistic competences, expectations, and policies. This article advocates for interdisciplinary approaches to (language) education as societies’ and students’ needs constantly evolve and calls on all learners’ and educators’ responsibility to counteract such movements.

1. Introduction

The increasing popularity of radical right, anti-immigrant, (neo-)nationalist movements throughout Europe can be seen as a response to super-diverse, complex migration and globalization processes challenging the ideology of the ‘nation-state’ as a linguistically and culturally homogeneous entity (Blommaert and Verschueren Citation1991). As sharply pointed out by Komorowska (Citation2014), ‘thinking of languages is connected with thinking of ethnicity and–whether we like it or not–about nations’ (Komorowska Citation2014, 20). Although these developments have been canvassed in both the media and political scholarly literature (Eger and Valdez Citation2015), a substantial gap remains in language education (McIntosh Citation2020). This is despite the fact that (neo-)nationalism can be seen ‘as an integral and inevitable, if sometimes invisible, part of language teaching, learning, and use’ (Motha Citation2020, 296). Language can impact pedagogical and educational practices and policy, which are already heavily shaped by neoliberal underpinnings and commodification processes (Heller Citation2006). The historically established relationship between nation-state and national language (Hobsbawm Citation2012) ‘with which one becomes aware of the linguistic commonalities towards the “inside” and at the same time tries to distinguish oneself from the “outside”’ (Ruoss Citation2019, 249 [my translation]) are inherently problematic if both nation and language are considered ‘imagined’ or ‘invented’ (Anderson Citation1991; Makoni and Pennycook Citation2007). The one nation–one language paradigm (Bauman and Briggs Citation2000) on the one hand benefits those with privileged access to the local linguistic and cultural background, while successfully censoring others to protect ‘the old ethnicity’ (Heller Citation2006; Bourdieu Citation1991). Languages are thus understood here as resources distributed in unequal ways whose values are socially determined under specific sociohistorical conditions contributing to ‘the construction of social difference and social inequality at a time of transition, when old ethnonationalist ways of constructing belonging are challenged by movement, multiplicity and commodification’ (Heller Citation2006, xi). They are mobilized to pursue sociopolitical and economic agendas which legitimize and (re)produce (existing) ideologies. Such ideologies thus influence the value, prestige, and (symbolic) power (Bourdieu Citation1991) of certain languages and speakers themselves vis-à-vis others and can have felt physical and material consequences on those individuals. Empirical research has further established a pattern of correlations among ideologies, ethnic identity, and the perceived prestige of languages leading to what has been termed the linguistic inferiority principle by Wolfram (Citation1998) especially in migrants (Kasstan, Auer, and Salmons Citation2018) and the endangerment of ethnolinguistic vitality (Yagmur and Ehala Citation2011).

Super-diverse language practices and policies and ‘the wish to pass or necessity…of passing [as a native speaker]’ (Motha Citation2014, 94) are extremely important areas of research given societies’ increasing multilingualism. More specifically, transdisciplinary research is necessary to understand the connection between language learning and teaching, certain national languages, and the resurgence of nationalism, which only twenty years ago had been downplayed as ‘only islands in an overwhelming river of banal cosmopolitanism’ (Beck and Willms Citation2003, 37). Contrarily, the last two decades have however demonstrated a mounting ‘pressure to strengthen borders’ (Billig Citation2017, 308).

A more critical discussion in the field of language education is needed to ‘meet the…needs of additional language users, their education, their multilingual and multiliterate development, social integration, and performance across diverse globalized, technologized, and transnational contexts’ (DFG Citation2016, 24). Finally, this article aims to contribute to a much-needed promotion of nation-conscious language education by examining students’, teachers’, and policy makers’ perspectives on the teaching and use of English as a lingua franca (ELF), by investigating the following research questions:

To what extent do actors in Switzerland’s education system view ELF as a threat to national languages and identities?

What role does ELF play in Swiss society and how does it affect resurgent (neo-)nationalist tendencies?

2. English as a lingua franca within Switzerland’s linguistic landscape

2.1. English as a lingua franca

English takes on a complex role in the study’s setting as it has been debated as the ‘fifth national language’ (Watts and Murray Citation2001), yet, despite recent calls from the economic sector, it has never received official status (Becker Citation2023). According to Durham (Citation2016), English in Switzerland can be described as a lingua franca. Seidlhofer (Citation2011, 7 [emphasis in original] has defined English as a lingua franca as ‘any use of English among speakers of different first languages for whom English is the communicative medium of choice, and often the only option’ (Seidlhofer (Citation2011, 7 [emphasis in original]). ELF can thus serve as a mediator in intercultural (inter- and intranational) communication, in an attempt to reject any hierarchical order of different Englishes. Thus, applying the language and communicating in it with little (or no) regard to accuracy or existing native-speaker norms conveys a certain informality and may be regarded as the easier option compared to Switzerland’s other national languages. ELF is further said to provide a ‘neutral’ terrain where linguistic and national borders typically associated with a certain national variety are dissolved. ELF speakers commonly produce meaning, try to establish consensus, and provide mutual support since they might both encounter difficulties when expressing themselves in a language which is not their L1 (Seidlhofer Citation2011).

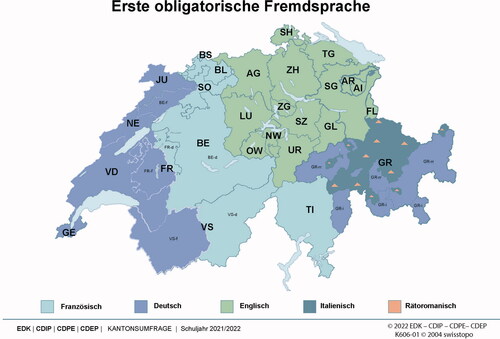

On the other hand, Marácz (Citation2018) remarks that there is an inextricable connection between language and power mechanisms, which persist in ELF communication and create de facto hierarchies among accents and speakers. This situation is exacerbated through institutional language use and learning since, as argued by Skutnabb-Kangas (Citation2009), students’ achievement is measured according to their adoption of such linguistic standards and norms. English’s hegemonization of the local language ecology (Phillipson Citation2018) becomes also manifest in its language education policies. As visible in below, English has divided Switzerland’s cantonsFootnote1 and their education systems along their curricula into two camps: those prioritizing English as a first foreign language to be taught in school and those teaching national languages first. While the cantons around Zurich (ZH) chose to introduce English before the second national language French approximately 20 years ago, the other parts of Switzerland continue to teach the national languages before English.

Figure 1. First mandatory foreign language taught divided by canton (taken from EDK, Citation2022).

2.2. Switzerland’s linguistic landscape

Similar to its neighboring countries, Switzerland’s linguistic landscape of the 21st century is heavily influenced by anglicisms and Anglo-American culture especially in media, tourism, and finance hubs. That said, from a language policy perspective, Switzerland has traditionally focused on its national languages. The four national languages differ substantially in their population of speakers, however: German (62.3%), French (22.8%), Italian (8%), and RomanshFootnote2 (0.5%) (FSO. Citation2022). The existence of four different linguistic regions within one national territory is often regarded as a unique Swiss characteristic. One example of Switzerland’s symbolic equal linguistic treatment is its official Latin name Confœderatio helvetica (Swiss Confederation), adopted in 1879 (Marcacci Citation2020). Switzerland is known to ‘take pride in its multilingualism’ (Kużelewska Citation2016, 125) and often characterized as Willensnation [a nation united by choice] given its linguistic and cultural heterogeneity (Maiolino Citation2013), although Chollet (Citation2011) proposes ‘fractured nation’ instead to raise awareness of the de facto lacking national cohesion and community.

Linguistic freedom and the equality of the four national languages are guaranteed by the Swiss Federal Constitution. However, the territoriality principle dictates that ‘the cantons shall decide on their official languages. In order to preserve harmony between linguistic communities, the Cantons shall respect the traditional territorial distribution of languages and take account of indigenous linguistic minorities’ (Federal Constitution of the Swiss Confederation, Art. 70, 2). Interestingly, Stotz (Citation2006) raised awareness of the fact that the translation of the Swiss Federal Constitution in German, French, Italian, Romansh, and EnglishFootnote3 differs with regard to exactly this article. To wit: compared to ‘preserving harmony’ in English, ‘German Einvernehmen (‘mutual agreement or comity’) is rendered as harmonie in the French version while the Italian text speaks of guaranteeing linguistic peace (per garantire la pace linguistica) as if from south of the Alps the situation appears more perilous’ (Stotz Citation2006, 250 [emphasis in original]).

3. The study

The study is embedded in a phenomenological research design focusing on everyday practices and perspectives of secondary school students (aged 16-19), teachers, and policy makers. Participation was voluntary and written and/or verbal consent was collected beforehand. Cantonal authorities granted permission to collect data in schools after substantial information was provided about the study’s objectives, data collection, and dissemination process. The study took place in three Swiss secondary schools in three different language regions: Grisons (Romansh), Fribourg (French), and Zurich (German). The schools were chosen based on their primary school language and the only positive responses received for data collection. Unfortunately, permission was denied in the Italian-speaking canton of Ticino so that merely 3 out of 4 Swiss language regions are represented. Data were collected from March to October 2020 and included 94 student questionnaires (38 in Grisons, 36 in Zurich, and 20 in Fribourg) and 38 semi-structured, in-depth interviewsFootnote4 (14 with students, 20 with teachers, and 4 with policy makersFootnote5). Given the phenomenological focus of the study, only open-ended questions from the questionnaires were analyzed. The questionnaires were administered first to select interview participants based on their responses to increase heterogeneity. The interviews lasted between 30-90 minutes and were conducted in German, French, and Italian over MS Teams, Skype, and phone due to the Covid-19 pandemic and school closures. The audio-recorded interviews and open-ended questions were transcribed verbatim and analyzed using van Manen’s (Citation2017) phenomenological qualitative data analysis technique in MaxQDA. The phenomenological data analysis allows us to uncover and question individuals’ unconscious beliefs and opinions about a topic of central importance and reveals how they experience it without being necessarily aware of it. The transcripts were read three times to accurately represent participants, reduce my own bias, and coded thematically combining space, body, and time as essential phenomenological codes (van Manen Citation2017). The analysis resulted in the following themes presented in more detail below in different sub-sections:

Societal friction through ELF

Intranational communication

Language, origin, and identity

The education system’s responsibility

Language teaching can be ‘torture’

Increased pressure and expectations through higher English language skills

4. Findings

This section presents the study’s findings on students’, teachers’, and policy makers’ perspectives on the teaching and use of English compared with Switzerland’s national languages and identities and its role in resurgent (neo-)nationalism.Footnote6

4.1. Perceived challenges of globalization and tradition in Swiss society

The analysis has shown that ELF is a major contributor to societal tensions regarding globalization and (neo-)nationalist traditions. In fact, it is viewed as the underlying cause of tensions among the different national language groups by many participants. Contrarily, others believe that ELF should function as a mediator to foster intranational communication, mutual understanding, and social cohesion. Interestingly, these diverging views were not only expressed throughout the entire sample regardless of their age or position (student, teacher, policy maker), but certain participants contradicted themselves by adhering to both perspectives.

4.1.1. Societal friction through ELF

Eleonore (T/ZH), for instance, believes that ELF ‘is asserting itself unnoticed via the language’. Victoria (T/FR) views the tensions to be substantially higher between the French- and German-speaking parts of Switzerland where she witnesses ‘a friction’ and where ‘the other language is…perceived as a competitor’. Julien (T/FR) shares his point of view and says that ‘the French-speaking Swiss have no choice. They HAVE to learn German’. That said, such tensions are also experienced by Romansh-speaking participants such as André (S/GR), who is of the opinion that ‘one language for four different cultures doesn’t really work well’ and who is ‘frustrated’ with how Romansh is ostensibly unjustly treated on a societal level compared to other national languages: ‘Every time it is German, French, and Italian. The worst is when there is a press release in the national languages and ENGLISH’. As further pointed out by Matthias (PM), ‘[English] is NOT, it is important to say, a national language.’ According to him, ‘it [is] disrespectful when the German-speaking part of Switzerland uses English instead of French…I really do find it disrespectful.’ Consequently, the French-speaking part of Switzerland is viewed as ‘more sensitive and respectful…actually interested in the other culture that takes place right on my doorstep’.

Further, André strongly connects Switzerland’s national languages to membership of the local language ecology seemingly disturbed by ELF whose influence ‘is becoming too big.’ More specifically, speaking a national language is seen as prerequisite to being a legitimate resident ‘because you have to be able to communicate with your own people first’, as André explains. Similarly, Henri (T/GR) advocates learning as many national languages as possible since ‘one is not a good world citizen if one does not treat well one’s neighbor.’ In his view, such communication and community integration necessarily take places in the national languages whereas ‘English can be put on the back burner.’ That said, Arthur (S/ZH), although he considers it ‘a problem that you have to use [English] to communicate with other Swiss people’, also believes that the concept of ‘world citizen’ necessarily includes a certain level of proficiency, especially when it comes to politicians representing Switzerland internationally: ‘When I see someone like Ueli Maurer [Federal Councilor] in an interview with CNN where he embarrasses himself in English…that’s how the international community simply sees us then.’ Even in national contexts, the expectation to possess advanced English skills is increasing in analogy to exposure to English through anglicisms, as criticized by Eleonore (T/ZH): ‘It’s totally shocking right now with all these English terms in this Covid crisis…I also don’t understand at all why everything has to be named in English. It’s certainly…still seen as a guiding culture’.

4.1.2. Intranational communication

To counteract societal developments prioritizing ELF as a common means of communication, André (S/ZH) is of the opinion that ‘in the worst case, you can still speak German’, which is considered a more ‘legitimate’ lingua franca as the majority national language than English. Julien says that ‘we have four languages, but we use a fifth one to communicate: ENGLISH’, which, according to him, will exacerbate ‘federal cohesion.’ Etienne (T/FR) has a rather pragmatic point of view based on actual personal linguistic practices and experiences:

When my [French-speaking] children go to [German-speaking] Zurich and want to communicate, they speak English…the state, the nation, sticking together, yes, what’s the point? It’s more important that people communicate. Whether they speak English, Latin or German is basically irrelevant.

Switzerland…has never actually been a nation. Very little actually holds it together, and it is actually a miracle…People always say in the French-speaking part of Switzerland, because they don’t understand each other…we don’t actually listen to the others. That also has advantages. There are also old married couples who no longer listen to each other, and that’s why they’re still together.

Based on this perspective, Etienne (T/FR) advocates ELF as primary language in Switzerland, ‘a pidgin English actually, a relatively low level that everyone more or less masters’. Similarly, Ralf (PM) sees a possibility for greater social inclusion and equity by adopting English as Switzerland’s fifth national language. As he put it: ‘these big companies would like it most if English were introduced as the official language of the Confederation…But maybe also for the immigrant workers…and they are not all people who bring with them an official language of the Confederation’. Conversely, Henri (T/GR) believes that even in Swiss business contexts, ELF is detrimental to rapport-building with employees: ‘If I become a manager in a company in the French-speaking part of Switzerland, if I manage this company in English or in French, then it will become clear very quickly which manager the staff prefers…If I manage these people in French, it’s quite another thing’.

However, even for local Swiss citizens, communication without ELF is not always an option. Students in Grisons do not necessarily learn French or Italian in school, which can exacerbate communication with the Italian- and French-speakers and render ELF necessary in intranational encounters and professional contexts. Problematically, as experienced by Hanna (S/GR), this can cause shame for the lack of French skills, which she compares to her French-speaking peers’ lack of German skills without realizing that they in fact learn German in school. On the other hand, Jovin (S/GR) ‘do[es] not think it’s necessary to learn French anymore’ because English is sufficient for his communicative purposes and German, his second L1, is Switzerland’s majority language. Therefore, Samira (S/ZH), for instance, believes that ‘if [English] is added, it will be even more difficult to communicate’ and she suggests sticking to German since it is spoken by most Swiss residents. A strong preference for German also becomes obvious in Gita’s (T/GR) statement: ‘German is simply everything’. She considers herself ‘conservative ‘ and rejects ELF for intranational communication. As she put it, ‘[ELF] is out of question…I can’t justify it…but I would reject it’. ELF is tolerated even less in official political contexts, as expressed by Nicolas (S/ZH): ‘I would find it a shame if they ended up speaking English in the National Council now just so that Ticino,…French-…and German-speaking Switzerland can work out a draft together’. This opinion is shared by Leonie (S/GR) who believes that ‘English simply doesn’t belong to Switzerland’. Conversely, as Christine (S/GR) points out, English becomes a legitimate (but forced) alternative ‘when I have to communicate with people from abroad’, raising questions as to who ascribes to and is defined as ‘foreign’ versus ‘local’. Additionally, as Jessica (S/GR) explains, imposing strict national language policies because ‘older people…are convinced that there is still Romansh-speaking territory here’ renders social integration more difficult for ‘non-locals’ and leads to ‘chas[ing] them away’.

4.1.3. Language, origin, and identity

Although a more multilingual and open language policy including ELF would benefit speakers of other languages significantly, insisting on Switzerland’s national languages is ‘more a matter of really marking one’s position…it’s simply more about identity, about ego’ (Jovin (S/GR)). On the other hand, ELF, for that matter, ‘is not something that one associates with the identity of Switzerland…[it is a] functional English, but otherwise the [Swiss] culture and the identity is preserved’ (Timo (S/GR)). Similarly, Nesrin (T/ZH) ‘[is] convinced that…English would not help at all. English is more of a language with a purpose…but the national languages and one’s own mother tongue are about identity’. Interestingly, as Timo (S/GR) goes on, such ‘neutral’ and ‘pragmatic’ characteristics detached from identity and culture seemingly correspond well to Switzerland’s perceived political neutrality and diplomatic responsibilities. That said, according to Samira (S/ZH), Switzerland’s quadrilingualism is further strongly linked to pride as well: ‘we are all proud to live in Switzerland and the four national languages are simply part of it and that is something that makes Switzerland’. Sonja (T/ZH) associates Switzerland’s quadrilingualism with nationalism whereas English is indicative of international competitiveness although ‘on an emotional level, that doesn’t make the French and the TicineseFootnote7 so happy’, as Sonja (T/ZH) concludes.

4.2. Perceived challenges of globalization and tradition in Swiss schools

Similar to existing perceptions on English as contributing factor to tensions in Switzerland’s society torn between globalization and (neo-)nationalist traditions, many participants view English as a threat to language learning and teaching historically focused on national languages.

4.2.1. The education system’s responsibility

The majority of the participants are of the opinion, as succinctly expressed by Eleonore (T/ZH), that it is ‘everyone’s obligation to learn a national language’, while David (T/FR), for instance, thinks it is ‘even better if it’s three or four [languages]’. Contrarily, David (T/FR) almost sarcastically states that ‘1% of the students would call [German] their favorite subject. It’s not exactly optimal that there is this resistance against [German]…it doesn’t exist against English, that’s a fact…[but] in my view it is really a mistake to [prioritize English]’. Similarly, Patrick (T/ZH) ‘notice[s] with some shock that students have no awareness at all of why they should learn French. They favor English very strongly’. As well, Matthias (PM) says, they will almost always prioritize English ‘because they find it cooler [and] because [it] is also more present in their everyday life’. Arthur (S/ZH), for instance, confesses to having neglected French in order to entirely focus on English also due to the Cambridge Certificate of Advanced English (CAE) exam, or as he put it, ‘French totally went downhill’ and he feels forced to participate in language exchanges between German- and French-speaking Switzerland typically organized by the school. According to Elisabeth (T/ZH), French lessons are being reduced so that more time can be allocated to English and other subjects such as informatics since they ostensibly correspond better to societal trends and economic interests than French. As Patrick (T/ZH) cautions, however,

the school…[is]not only as a servant of the economy…[it] should definitely be able to set other accents as well…German-speaking Switzerland has a certain responsibility to pay attention to the other languages as well and not just look at these pragmatic arguments.

4.2.2. Language teaching can be ‘torture’

Eleonore (T/ZH) also finds such developments problematic and thus advocates for a stronger institutional promotion of national languages to ‘resist ‘ English domination. As she reported, ‘apparently, [French teaching] is torture, there is no other way to put it’. The ‘battle between English and our national languages’ (Matthias, PM) exacerbates the already overwhelming linguistic situation for heritage language-speaking children, according to Elisabeth (T/ZH), because ‘the children…speak Serbian at home, then they would have to learn [Swiss German], have to learn High German, learn English from the 2nd grade and then French from the 4th grade. And as you can see, they’re not fluent in ANY language’.

In Henri’s (T/GR) experience, often, language learning is considered to be ‘an ordeal, torture and if it has to be, then only one [language] and that is English’, alluding to the fact that (learning) English is vastly preferred over other national languages by most students. Jeanne (T/FR) is convinced that ‘at the level of academic career, English takes the lead over French and German’, whereas this ‘pragmatic view’ is criticized by Matthias (PM): ‘[this] is more of a business-oriented view that focuses on effectiveness and efficiency…, English is THE language, that when we talk about globalization and internationalization, our students must learn English as quickly as possible’. That said, as policy maker, he also takes the blame for such a development and argues that ‘the EDK [The Swiss Conference of Cantonal Ministers of Education] has failed’ in developing and implementing nation-wide (binding) language education policies accounting for Switzerland’s quadrilingualism, the (social) importance of its national languages, and the increasing influence of ELF. A common solution including each of the 26 cantons’ interests would also be considered necessary by Nicole (T/GR), for instance, since parents seem to favor school programs prioritizing English and are unhappy with those which do not (officially) do so: ‘…those cantons like Grisons would say that Zurich is much better at teaching English. My child should also learn English. Why should he learn Romansh? It doesn’t help my child at all’. According to Victoria (T/FR), the situation is somewhat less tense in Ticino since they typically automatically have to learn both German and French to study and work in other parts of Switzerland. She thinks that the teaching of German and French is conducted much more ‘equally…than…in the French-speaking canton where German MUST be learned’.

4.2.3. Increased pressure and expectations through higher English language skills

On the one hand, when talking about their teaching practices, especially English teachers revealed how its omnipresence in the media and particularly students’ free-time activities have facilitated teaching and increased students’ motivation to learn it. Importantly, however, on the other hand, as pointed out by Sabine (T/ZH), the colloquial exposure to and usage of English by her students has also contributed to the deterioration of grammatical and orthographic accuracy and thus complicated her tasks to a certain extent: ‘there are different registers,…[which] then [mix] with an informal influencer YouTuber vernacular…What works in a text message, what works when I make a video of myself?’

Interestingly, English even influences L1 classes in German-speaking Switzerland, as Sonja (T/ZH) explains. Given the diglossic situation of Swiss German and standard German, students rely on German (academic) language exposure to also develop their L1, which is impeded when biology or history classes are taught in English to promote content and integrated language learning. Her quote captures the diglossic complexity very well: ‘if [history] is only taught in English, then perhaps one loses the competence to be able to express oneself well in the mother tongue or for us just the school language, or how should I call it?’ Paradoxically, however, speaking English in class is more natural for her than German despite having studied both languages at university and being a ‘native speaker’ of (Swiss) German: ‘I feel more comfortable when I can speak English in the classroom than when I have to speak High German’.

That said, the high level of English in Swiss upper secondary schools, especially those that offer CAE certificates, puts enormous pressure and responsibility on teachers as well as students. Jovin (S/GR), for instance, reported that ‘in the year before the Advanced [English exam] I always had a guilty conscience if I have not watched something in English and now I really savor it that I have passed the Advanced and currently watch only German to compensate’. Nicole (T/GR), as a representative of the teacher perspective, experiences an increase of pressure during the last two years before graduation ‘because as a teacher, you still have the feeling that they have to pass, otherwise I’m not a good teacher’. Problematically, the challenge of passing the CAE in addition to regular curricular requirements has an impact on teachers’ identification as successful teachers and students’ learning habits and even spare time activities.

5. Discussion

Switzerland with a strong political and curricular emphasis on its four national languages, historically established linguistic and cultural traditions, and highly complex local language ecology composed of national standard and dialectal varieties and many heritage languages is struggling to reconcile underlying societal forces of globalization and (neo-)nationalist traditions legitimately and equitably. Similar to what has been observed by Heller (Citation2006), Switzerland’s national languages and the learning and promotion thereof by the public education system is an effective and often unquestioned measure to preserve the ‘old ethnicity’. The old ethnicity is reproduced in perspectives held even by students who, as André, believe that knowing national languages is important ‘to communicate with one’s own people first’.

Yet, the established linguistic status quo captured in such ideologies but also enshrined officially in language laws, education policies, and regulations such as the territoriality principle is increasingly challenged by movements, transitions, and reterritorialization processes heavily shaping the local language ecology and redefining the term ‘ethnic’ in the Swiss context. Interestingly, Romansh, spoken by 0.5% of the population and primarily in the canton of Grisons, is in fact the sole ‘indigenous’ language in Switzerland whereas its official languages–German, French, and Italian–are shared with the neighboring countries. Arguably, this can be seen as one of the reasons why such distinct Swiss linguistic markedness as materialized in a plethora of local dialects, linguistic pride, and negative attitudes toward ‘foreign’ languages and even ELF exists. As the data have further shown, such markedness is often linked to nationalist tendencies, advocating that the official national languages have a higher legitimacy within the Swiss context than English, for instance, although most Swiss residents are not fluent speakers of the national language(s) and intranational communication and exchange suffer from this lack of understanding and mutual language (Durham Citation2016). This is rather indicative of Chollet’s (Citation2011) assessment of Switzerland as a ‘fractured nation’, which is ostensibly kept alive through (neo-)nationalist tendencies and movements as the image of the traditional Willensnation lives on.

Further, the additional and intensive measures taken to promote the minority national language Romansh in Grisons’ secondary schools, for instance, leads to the institutional neglection of French (and Italian), considered crucial for students’ professional and academic development. English, on the other hand, is not only prioritized over the other official national languages as a mandatory subject but even more strongly through the CAE. As the data indicate, this puts additional pressure on both English teachers and students since some of the former equate their students’ successful passing of the CAE with their teaching skills whereas some of the latter immerse themselves in English-speaking media not to ‘[have] a guilty conscience’ (Jovin). This fixation on English is legitimized through economic and pragmatic arguments such as global access to information, economy, and other opportunities (Tupas and Rudby Citation2015), which are depicted as unattainable for speakers of (only) Switzerland’s national languages. Ironically, ELF seems to serve its purpose as interlingual and intercultural mediator more successfully within Switzerland, despite strong ideologies in favor of national languages for linguistic practices among Swiss residents, than on an international scale. Also, although English use in Switzerland rather corresponds to lingua franca interactions (Ronan Citation2016), the English varieties such as American or British English taught in Swiss schools continue to reproduce native-speaker ideals, often expected and imitated by teachers and students alike (Becker Citation2023). As pointed out by Marácz (Citation2018), ELF is an ‘illusion’ and the dominance and power English as a language and the teaching industry exert onto Switzerland’s national but also heritage languages are real (Phillipson Citation2018), despite sometimes being obfuscated.

Finally, generally speaking, the teaching and use of ELF is viewed as a threat to Swiss national languages and identities by some participants while it is simultaneously appreciated and highly promoted by almost all. ELF seems to be an unstoppable societal development, which nevertheless poses certain significant challenges to the education system and also the (imaginary) constitution of especially multilingual countries. In the case of Switzerland, ELF can to a certain extent be seen as an endangerment to its ethnolinguistic vitality (Yagmur and Ehala Citation2011) because it is perceived as the most important and prestigious international language and associated with unlimited access, opportunities, and mobility. This is so much so the case that it hegemonizes Switzerland’s educational and linguistic landscape by dividing its 26 autonomous cantons into two camps: those prioritizing the teaching of English over a national language and those adhering to the traditional curriculum in which a national language is introduced before English. The majority of the present study’s participants therefore viewed English as a troublemaker or even threat since it monopolizes curricula and teaching practices and homogenizes the de facto linguistic diversity through individuals’ ideologies. At the same time, it exacerbates and intensifies nationalist traditions which arise out of protectionist behavior and attitudes toward the ‘international infiltrator’. In order to preserve the historically established status quo and contribute duly to the Willensnation, whose most important characteristics are its linguistic and cultural diversity, the learning and use of national languages is indispensable. Most of the participants romanticized Switzerland’s quadrilingualism, partly oblivious to the fact that in reality there is very little exchange, let alone social cohesion or mutual understanding if members of the different language regions possess only little (or no) knowledge of the others’ languages. In order to counteract nationalist tendencies and their reproduction in language teaching and use, more awareness of such societal developments is urgently needed.

6. Conclusion

This study has shown that language choices are often not made on pragmatic or reasonable grounds but incorporate historical struggles and (nationalist) traditions (Gramsci Citation1971) to unify heterogeneous groups of individuals into one community or nation (Anderson Citation1991). In the case of Switzerland, where four national and many more heritage languages exist, societal tensions are extremely high and are currently being intensified by the seeming omnipresence and high value and utility of English. Apart some exceptions, however, English was not considered to be the most significant language of individuals’ identity. Considered ‘strange’ or ‘foreign’ by some without being able to provide an explanation for such attributions, English does not seem compatible with the sense of belonging provided by the regional varieties of the national languages spoken across Switzerland. As participants reiterated, those clearly function as identity markers. It could however be argued that English has in fact found its place in Switzerland and functions–albeit unconsciously–as a fifth national language and intranational communication is indeed hardly conceivable without ELF at its center. Without official representation of English and continuing sociopolitical efforts to prioritize local national languages, the question remains of how (if at all) non-locals who move to Switzerland–either forced or voluntarily–will be able to successfully integrate into society and the education system with less advanced knowledge of the national language(s). And further, even among those, ‘striking a balance between these languages remains challenging’ (McIntosh Citation2020, 3).

Given the study’s qualitative focus and narrow sample, future studies adopting a quantitative approach with representative samples across society including and differentiating among groups (age, race, class, etc.) could very well complement the data presented here. It would also be interesting to examine the ideological and sociopolitical mechanisms impacting ELF in Switzerland’s monolingual neighboring countries, such as Germany or France, for instance. Such studies could contribute to better understand the interplay of language(s), politics, and (neo-)nationalism in contexts where right-wing parties are gaining in significance and are posing a threat to democracy, creating instability across all of Europe. Different methodologies can further be envisaged to capture existing media discourses or through comparing different national contexts using multi-sited ethnographies, for instance, to document how (neo-)nationalism is not only expressed through language but also enacted or visualized through cultural artefacts.

Since the study focused on educational sphere actors, the following recommendations are made: language is used to legitimize one’s position in society, to prove one’s belonging, and develop one’s (linguistic/cultural) identity. If the education system fails to accommodate incoming students and to offer scaffolding in 1) heritage language promotion and 2) additional support in the medium of instruction, it (re)produces in- and out-groups based on their linguistic competences (Bourdieu Citation1991). Thus, policies need to be drafted and enacted that are mindful of subjective dimensions of language but also take into account friction that stems from competing societal processes of globalization and super-diversity on the one hand and (neo-)nationalism and protectionism on the other. Also, such policies are in need of constant changing as societies’ – and therefore future generations’ – needs evolve. It is the school’s responsibility to train students to understand their true meanings and interdependencies through interdisciplinary approaches including sociology, political science, geography, and language education. It is further the school’s responsibility to educate its students in democracy, to teach them to form and express their own opinion, and thereby counteract (neo-) nationalist movements that endanger diversity, progress, and equity. Finally, it is our responsibility as language educators to use our voice to speak up for democracy, regardless of the language we use.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (21.1 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Notes

1 A canton is the administrative division used in Switzerland, similar to a state in other countries.

2 Romansh is an umbrella term covering five regional dialects (idioms) derived from Latin and used in the canton of the Grisons and has been recognized as a Swiss national language since 1938 (Becker Citation2023).

3 Since English is not an official language of the Swiss Confederation, the English version of the Federal Constitution is only a translation and is not legally binding.

4 The semi-structured interview guides as well as the questionnaire are attached as supplemental online material. Some of the questionnaire items are inspired by the European Language Portfolio to ensure students’ familiarity with the topics and terminology.

5 All names have been changed to guarantee participants’ anonymity. In the findings section, their pseudonyms are used along with information on their position (student, teacher, policy maker) and place of residence (Fribourg (FR), Zurich (ZH), and Grisons (GR)).

6 Some of the quotes used here are analyzed within a different theoretical framework in Becker Citation2023.

7 Individuals living in the canton of Ticino (Italian-speaking Switzerland).

References

- Becker, A. 2023. Identity, power, and prestige in Switzerland’s multilingual education. Transcript.

- Anderson, B. 1991. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. London/New York: Verso.

- Bauman, R., and C. L. Briggs. 2000. “Language Philosophy as Language Ideology: John Locke and Johann Gottfried Herder.” In Regimes of Language: Ideologies, Polities, and Identities, edited by P. V. Kroskrity, 139–204. Santa Fe, New Mexico: School of American Research Press.

- Beck, U., and J. Willms. 2003. Conversations with Ulrich Beck. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

- Billig, M. 2017. “Banal Nationalism and the Imagining of Politics.” In Everyday Nationhood: Theorising Culture, Identity and Belonging after Banal Nationalism, edited by M. Skey and M. Antonsisch, 307–321. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Blommaert, J., and J. Verschueren. 1991. “The Pragmatics of Minority Politics in Belgium.” Language in Society 20 (4): 503–531. doi:10.1017/S0047404500016705.

- Bourdieu, P. 1991. Language and Symbolic Power. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

- Chollet, A. 2011. “Switzerland as a ‘Fractured Nation.” Nations and Nationalism 17 (4): 738–755. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8129.2011.00520.x.

- Durham, M. 2016. “English as a Lingua Franca: Forms and Features in a Swiss Context.” Cahiers du Centre de Linguistique et des Sciences du Langage 48: 107–118.

- EDK. 2022. “First Mandatory Foreign Language.” https://www.edk.ch/de/bildungssystem/kantonale-schulorganisation/kantonsumfrage/b-11-fremdsprachen-sprache-beginn

- Eger, M. A., and S. Valdez. 2015. “Neo-Nationalism in Western Europe.” European Sociological Review 31 (1): 115–130. doi:10.1093/esr/jcu087.

- FSO. 2022. “Languages.” https://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/en/home/statistics/population/languages-religions/languages.html

- Geeraerts, D. 2003. “Cultural Models of Linguistic Standardization.” In Cognitive Models in Language and Thought. Ideology, Metaphors and Meanings, edited by R. Dirven, R. Frank, and M. Pütz, 25–68. Berlin/Boston: Mouton de Gruyter.

- Gramsci, A. 1971. Selections from the Prison Notebooks. New York: International Publishers.

- Heller, M. 2006. Linguistic minorities and Modernity: A Sociolinguistic Ethnography. 2nd. ed. London/New York: Continuum.

- Hobsbawm, E. J. 2012. Nations and nationalism since 1780: Programme, myth, reality (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Kasstan, J. R., A. Auer, and J. Salmons. 2018. “Heritage-Language Speakers: Theoretical and Empirical Challenges on Sociolinguistic Attitudes and Prestige.” International Journal of Bilingualism 22 (4): 387–394. doi:10.1177/1367006918762151.

- Komorowska, H. 2014. “Analyzing Linguistic Landscapes. A Diachronic Study of Multilingualism in Poland.” In Teaching and Learning in Multilingual Contexts: Sociolinguistic and Educational Perspectives, edited by A. Otwinowska and G. De Angelis, 19–31. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

- Kużelewska, Elżbieta. 2016. “Language Policy in Switzerland.” Studies in Logic, Grammar and Rhetoric 45 (1): 125–140. doi:10.1515/slgr-2016-0020.

- Maiolino, A. 2013. “ Die Willensnation Schweiz im Spannungsfeld konkurrierender Transzendenzbezüge.” In Demokratie und Transzendez: Die Begründung politischer Ordnungen, edited by H. Vorländer, 449–472. Bielefeld: Transcript.

- Makoni, S., and A. Pennycook. 2007. “Disinventing and Reconstituting Languages.” In Disinventing and Reconstituting Languages, edited by S. Makoni and A. Pennycook, 1–41. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

- Marácz, L. 2018. “Languages, Norms and Power in a Globalized Context.” In The Politics of Multilingualism: Europeanisation, Globalization and Linguistic Governance, edited by F. Grin and P. A. Kraus, 223–243. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

- Marcacci, M. 2020. “Confoederatio Helvetica (CH).” Historisches Lexikon der Schweiz. https://hls-dhs-dss.ch/de/articles/009827/2020-09-15/

- McIntosh, K. 2020. “Introduction: Re-Thinking Applied Linguistics and Language Teaching in the Face of Neo-Nationalism.” In Applied linguistics and Language Teaching in the Neo-Nationalist Era, edited by K. McIntosh, 1–13. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Motha, S. 2014. Race, empire, and English language teaching: Creating responsible and ethical anti-racist practice. Teachers College Press.

- Motha, S. 2020. “Afterword: Towards a Nation-Conscious Applied Linguistics Practice.” In Applied linguistics and Language Teaching in the Neo-Nationalist Era, edited by K. McIntosh, 295–309. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Phillipson, R. 2018. “English, the Lingua Nullius of Global Hegemony.” In The Politics of Multilingualism: Europeanisation, Globalization and Linguistic Governance, edited by F. Grin and P. A. Kraus, 275–304. John Benjamins Publishing Company.

- Ronan, P. 2016. “Perspectives on English in Switzerland.” Cahiers du Centre de Linguistique et des Sciences du Langage 48: 9–26.

- Ruoss, E. 2019. Schweizerdeutsch und Sprachbewusstsein: Zur Konsolidierung der Deutschschweizer Diglossie im 19. Jahrhundert. Berlin: De Gruyter.

- Seidlhofer, B. 2011. Understanding English as a Lingua Franca. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Skutnabb-Kangas, T. 2009. “Multilingual Education for Global Justice: Issues, Approaches, Opportunities.” In Social Justice through Multilingual Education, edited by T. Skutnabb-Kangas, R. Phillipson, A. K. Mohanty, and M. Panda, 36–62. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

- Stotz, D. 2006. “Breaching the Peace: Struggles around Multilingualism in Switzerland.” Language Policy 5 (3): 247–265. doi:10.1007/s10993-006-9025-4.

- The Douglas Fir Group (DFG). 2016. “A Transdisciplinary Framework for SLA in a Multilingual World.” The Modern Language Journal 100: 19–47.

- Tupas, R., and R. Rudby. 2015. “Introduction: From World Englishes to Unequal Englishes.” In Unequal Englishes: The Politics of Englishes Today, edited by R. Tupas, 1–17. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- van Manen, M. 2017. Researching lived experience: Human science for an action sensitive pedagogy, (2nd ed.). Taylor & Francis Group.

- Watts, R. J., and H. Murray, eds. 2001. Die fünfte Landessprache? Englisch in der Schweiz. Zürich: vdf Hochschulverlag.

- Wolfram, W. 1998. “Black Children Are Verbally Deprived.” In Language Myths, edited by L. Bauer and P. Trudgill, 142–152. London: Penguin.

- Yagmur, K., and M. Ehala. 2011. “Tradition and Innovation in the Ethnolinguistic Vitality Theory.” Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 32 (2): 101–110. doi:10.1080/01434632.2010.541913.