Abstract

Agroecology is recognised as a socio-political and agricultural praxis and as a scientific domain. However, the dominant anthropocentric narrative that views nature as an exploitable resource is still present in agriculture faculties. In this contribution, we use three avenues to advance the possibilities of linking two counter-hegemonic forces to transform agriculture higher education. Firstly, the article examines the connection between decolonisation as a theoretical concept and the practices of decoloniality unfolding in agroecology. Secondly, we explore the diálogo de saberes, the Latin American approach of knowledge dialogue, as a bridge to connect diverse knowledge systems. The third path correlates literature findings with a Bolivian higher education program that has been around for three decades. Our experience shows that the dyad of agroecology and decolonial turn plays a significant role in transforming agricultural education by opening new paths to engage in a collaborative process between multiple knowledge systems.

Introduction

Ending hunger by 2030 was one of the renewed global commitments for people and the planet of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. The promise plan of action for people is to end poverty and hunger, ensuring that everyone can fulfil their potential with dignity and equality and in a healthy environment. On the other hand, the commitment to the planet is to safeguard its natural resources by taking urgent action on climate change through activities such as sustainable consumption and production (United Nations, Citation2015). Despite these commitments, the outlook of the unprecedented COVID-19 crisis shows that reaching this goal is challenging. Studies show that in 2019, 2 billion people in the world were hungry, and food insecurity for the most vulnerable populations can worsen due to the persistent impact of the COVID19 pandemic (FAO et al., Citation2020).

The globalised industrial food system has not only failed to feed the world but also lead to climate change, displaced communities, destroyed the environment, diversity, and peoples’ health (Figueroa-Helland et al., Citation2018; Vandana, Citation2016). As a counter-hegemonic movement, agroecology has been growing during the last decades to challenge industrial agriculture (Figueroa-Helland et al., Citation2018) and defy power structures in all spheres (Giraldo & Rosset, Citation2018). Agroecology is trying to position itself as a social and alternative model for sustainable food production. It sustains food sovereignty, land, territory, and self-determination (Martínez-Torres & Rosset, Citation2014) by revitalising Indigenous and Local Knowledge (ILK) (Figueroa-Helland et al., Citation2018). It also contributes to empowering local actors through peasant-to-peasant knowledge and wisdom sharing (Altieri & Toledo, Citation2011).

The interest in agroecology as a science has also been proliferating, with a growing number of programs and degrees worldwide (Altieri & Nicholls, Citation2017; Méndez et al., Citation2013). Agroecological education raises awareness about the effects of industrial agriculture on the environment and health, while its emphasis is still on increasing agricultural production, viewing nature as an exploitable resource and giving little attention to the social, political and educational dimensions (Figueroa-Helland et al., Citation2018).

Parallel to this agroecological movement, there is another contra-hegemonic movement in education, advocating to transform knowledge production. The decolonial turn is a critic of hegemonic forms of knowledge production. Its objective is the decoloniality of power, knowledge, and being in all its manifestations – economic, political, cultural, and spiritual (Maldonado-Torres, Citation2019). Some authors consider that to deal with this complexity, it is necessary to develop heterarchical thinking (Castro-Gómez & Grosfoguel, Citation2007, p. 16) – a new language capable of facilitating a dialogue with other knowledge systems and within different paradigms. A creative encounter or Diálogo de Saberes (DS) between culturally differentiated beings (Leff, Citation2004) that do not annihilate other forms of thinking but instead complement each other (Rivera, Citation2012).

This paper examines possible paths to integrate the social and political dimensions in agricultural education by asking (i) what it means to decolonise education? (ii) how the diálogo de saberes can help in this decolonisation process? (iii) what challenges and mutual benefits emerge from bridging two counter-hegemonic movements, agroecology and the decolonial turn, transforming knowledge production? To answer these questions, we use three avenues. Firstly, we investigate the literature (i) to debate agroecology as an agricultural practice, social movement and scientific discipline and (ii) to identify strategies in the Higher Education (HE) literature used by authors to facilitate a dialogue between different knowledge systems. The latter categorises five analytical dimensions – methodological, epistemic, ontological, ethical and socio-political – and diverse workable solutions to deal with barriers inhibiting decolonial practices. Secondly, we explore the possibilities that offer the Latin-American approach of knowledge dialogue, namely the diálogo de saberes (Ghiso, Citation2000; Leff, Citation2004), as a bridge to intertwine agroecology and decolonial education. Finally, this research discusses an agroecological educational program, named Programa de Formación Continua Intercultural y Descolonizador (PFCID), using the five analytical dimensions identified in the literature along with the DS approach. We focus our attention on the program’s evolution, the methodological approach, the target population, and how it intertwines the academic, social, and political dimensions in the educational process. We also reflect on the lessons offered by integrating agroecology and decolonial movements to find new ways to improve our transformative educational goal to face the globalised industrial food system.

The paper starts by stating our positionality, followed by a literature review section discussing agroecology and the decolonial turn. Then, we introduce the PFCID program analysing possible decolonial paths based on the five dimensions identified in the literature review and the challenges of building a pluriverse of knowledge. Later, we discuss the insights of bridging the two counter-hegemonic movements to transform Higher Education (HE). We conclude with a final thought.

Positionality

The authors of this paper are an interdisciplinary group consisting of a Belgian researcher with Colombian origins together with six Bolivians researchers who have been collaborating for three years in the PFCID program. As a team, we started a self and collective reflexivity process about the evolution of the PFCID based on our participation in the different moments of the program, looking at it from different perspectives and disciplines. The interdisciplinary team includes four agronomists with 31, 29, 19 and 12 years working with the PFCID, respectively, one economist (27 years), one specialist in communication science (7 years) and one educational science specialist (3 years) collaborating in the PFCID. All the Bolivian researchers have indigenous or rural origins and were beneficiaries of PFCID before being enrolled as professors, researchers, or collaborators within PFCID. The Belgo-Colombian researcher and first author of this paper initiated the collective reflexivity process, implementing iterative thoughtful conversations about the program’s evolution. Our reflexivity process is not only based on life histories but also guided by the multiple publications and reports produced in the framework of the PFCID during its 30 years of praxis.

Agroecology as an alternative agriculture paradigm

Agroecology is the name given to science developed from ancestral knowledge and traditional agricultural systems that, for centuries, Indigenous people and local communities have used to deal with hostile environments. They have been practising sustainable agriculture to feed their communities without depending on mechanisation, chemicals, or other modern science technologies (Altieri & Nicholls, Citation2017). But agroecology is not only an agricultural practice; it is also a way of being, understanding, living, and feeling the world (Giraldo & Rosset, Citation2018). For Indigenous people and local communities, agroecology is not the technical concept of organic food production (Giraldo & Rosset, Citation2018). Agroecology is the way to guarantee their life, their territory, their culture, and their worldview. It embodies the struggles for food sovereignty, agrarian reform, and land and territory defence (Martínez-Torres & Rosset, Citation2014).

In recent times, agroecology has been positioning itself as a new paradigm based on diversity and collaborative work to solve problems generated by the green revolution, such as hunger, rural poverty, and sustainability (Méndez et al., Citation2013; Vandana, Citation2016). The green revolution, supported by modern science and under the motto of development while promising hunger abolition, has denied ancestral, local, and women knowledge. In the name of this denial, development missionaries invaded rural communities to teach Indigenous people and local communities how to plant, what seeds to use, how to increase production (Vandana, Citation2016). This dominant agricultural narrative also spread in Higher Education Institutions (HEIs), making, to a certain extent, agronomy faculties perfect allies for agribusiness. Dominant narratives turned agriculture into a monopoly of destruction that affects the soil with monocultures and chemical products and deteriorates the environment and people’s health while impoverishing them (Cleaver Jr, Citation1972; Vandana, Citation2016). The green revolution and industrial agriculture displaced and destroyed sustainable food systems that have nourished humanity over millennia (Vandana, Citation2016). Still today, agro-industrial monocultures and land-grabbing continue to displace rural communities from their territories (Santos, Citation2014).

Agroecology has been recognised as a social and political movement, an agricultural practice, and a scientific discipline (Altieri & Toledo, Citation2011; Wezel et al., Citation2009). As a social movement, it has been developing on different fronts against the economic, social, and ecological costs originated by agroindustry (Altieri & Nicholls, Citation2017; Méndez et al., Citation2013). It has been pressing to transform the neoliberal discourse on food security towards a focus on food sovereignty (Altieri & Toledo, Citation2011; Martínez-Torres & Rosset, Citation2014). It is struggling to decolonise food production systems through the revitalisation of Indigenous people/culture/knowledge (Figueroa-Helland et al., Citation2018) and empowering local actors through innovation and peasant-to-peasant wisdom sharing (Altieri & Toledo, Citation2011).

As an agricultural practice, agroecology promotes an integrated and sustainable way of understanding agriculture that reconciles the social, environmental, and economic needs of the food production system. It deals with agro-food production from seed to the fork (Altieri & Toledo, Citation2011; Gliessman, Citation2020; Vandana, Citation2016), and in which social movements share their praxis and co-create new knowledge (Martínez-Torres & Rosset, Citation2014).

Agroecology, as a science, has its roots in western ideologies that view nature as an exploitable resource (Figueroa-Helland et al., Citation2018). The agroecology taught in universities has a slant towards the natural sciences, focusing on the agricultural production process, diminishing or ignoring the social and political dimensions (Figueroa-Helland et al., Citation2018; Méndez et al., Citation2013). In a recent synthesis paper analysing the what (required competencies, skills, and attitudes), the how (teaching and learning models), and the who (learners and teachers) of agroecological education, David and Bell (Citation2018) concluded that it is essential to (i) adopt transdisciplinary and experiential learning approaches in agroecological education, (ii) diversify the origins and gender of the students and instructors, (iii) embrace participatory knowledge and (iv) adopt humility and appreciation for the value of other perspectives. At the same time, the paper raised the difficulty of integrating science with a political dimension since ‘scientists may fear a loss of legitimacy as neutral discoverers of truth’ (David & Bell, Citation2018, p. 5) by incorporating the agroecology socio-political dimensions in their teaching and research activities. Other scholars conceded that this situation prevails mainly among academics from the North. In contrast, in the South and especially among Latin American scholars, there is a consensus that transforming agricultural education is made by embracing transdisciplinary, participatory and place-based education, connecting them to the social and political realities (Altieri & Nicholls, Citation2017; McCune & Sánchez, Citation2019; Méndez et al., Citation2017; Rosset et al., Citation2021). These principles are in line with the decolonial turn’s ideals and the core concept of the PFCID program, as will be shown in the following sections.

Decolonising higher education – complexities and challenges

Scholars have long singled out HEIs as a legacy of colonialism that (re)produces modern Western hegemonic colonial schemes based on the presumed universality of their knowledge (Ahenakew et al., Citation2014; Andreotti et al., Citation2015; Bhambra et al., Citation2018; Stein, Citation2019; Tuck & Yang, Citation2012). The colonial is still present until today, not only in the former colonies but also in the neo-colonial powers where the voces perdidas (lost voices) continue to be silenced and ignored by power and privilege (Salinas, Citation2017). Colonial schemes delegitimise other ways of knowing and being and reproducing the violence of modernity – capitalism, colonialism, racism, heteropatriarchy (Andreotti et al., Citation2015; Maldonado-Torres, Citation2016; Stein, Citation2019) and ‘it will not allow itself to be pushed over without resistance’ (Dei, Citation2016, p. 29). Decolonial movements worldwide have shown us that the content, methodologies, and hegemonic power structures remain principally governed by Eurocentric thinking. Therefore, the importance of decolonising knowledge production and the power structures and the being (Maldonado-Torres, Citation2016). Similarly, Tuck and Yang (Citation2012) alert us to the risk of turning decolonisation into empty signifiers, settling surface changes rather than structural transformations. While all of these challenges are already difficult to face, Stein (Citation2019) challenges us further by asking:

How we might unlearn colonial habits of being that we might not even realise we have and learn to be affected by the world in unexpected ways that could then inform possibilities for higher education that are unimaginable from where we currently stand. (Stein, Citation2019, p. 159)

Being aware of the challenges mentioned above and considering that decolonisation implies a variety of definitions, aims, and strategies (Bhambra et al., Citation2018). We decided to examine the recent literature on what it means and what strategies could decolonise HE practice. We identify five dimensions – methodological, epistemological, ontological, ethical and socio-political – for which we sketch in , a non-exhaustive list of possible paths to start a decolonial process.

Table 1. Strategies to decolonise higher education.

The set of strategies structured into five dimensions presented in offers varied and overlapping commitments and examples to advance HE’s structural changes and decolonise knowledge production. At the same time, it gives insights into how to break modernity’s violence while engaging in a collaborative process for multiple knowledge systems’ co-existence.

Linking agroecology and decolonial education

There are various similarities between agroecology and decoloniality. Both are social, political, and academic counter-hegemonic movements pressing to transform neoliberal capitalism dominance. Moreover, as highlighted by Altieri and Nicholls (Citation2017), agroecological movements in Latin America have been promoting several epistemological innovations, some of them linked with decolonising dimensions such as (i) valorisation of IKL, (ii) the use of transdisciplinarity and holistic approaches, and (iii) the promotion of critical self-reflectivity. These three elements are crucial aspects for decolonising power structures in HE and the being. At the same time, they are the pillars of the DS approach.

Diálogo de saberes is an approach developed in Latin America in the 70 s. Its origins are linked to the emancipatory movements of Participatory Action Research (PAR) of Fals Borda and the use of popular education by Paulo Freire as a guide for developing critical consciousness (Archila, Citation2017; Ghiso, Citation2000; McCune & Sánchez, Citation2019). To understand the idea behind DS is necessary first to establish the difference between wisdom and knowledge. The Spanish word saberes could be associated with saber (to know – knowledge), but it is also related to sabiduria (wisdom). In looking at the meaning of the word knowledge, the classical definition refers to the idea of justified true belief. Instead, wisdom goes beyond the intellectual or cognitive domain. It is a cultural and collective product that results from the combination of cognition, self-reflection, self-awareness and openness to all kind of experiences that transform the individual in the process (Ardelt, Citation2004). It is not just about what is true; it is about what is right and fair. It is to know ‘how to lead a life that is beneficial for oneself, others, and society’ (Ardelt, Citation2004, p. 272). Having clarity about the meaning of the world saberes, we can understand the philosophy behind the diálogo de saberes.

As Leff (Citation2004) proposes, DS is an encounter of collective identities founded on cultural autonomies, from where an intercultural dialogue unfolds. It starts from recognising the other and their knowledge embodied in feelings, sensualities, and senses. DS deactivates the violence of the forced homogenisation of the diverse world and connects beings and wisdom. Crucial for decolonising HE and knowledge production. It goes beyond a strategy of inclusion and participation using methodological tools such as the pedagogy of solidarity (Gaztambide-Fernández, Citation2012) and the listening dialogue of wisdom (Moreno-Cely et al., Citation2021), among others. DS is a social practice that intertwines the real, the symbolic, and the imaginary in the act of thinking, feeling, and building a diverse world (Leff, Citation2004). DS proposes breaking with the subject-object duality of Western scientific knowledge. It suggests a constructive dialogue of multiple ontologies, epistemologies, and cosmologies, considering all kinds of knowledge as equally valid (Tapia Ponce, Citation2016).

As Grosfoguel (Citation2016) elucidated, Western science has not only denied other ways of knowing. It has also been practising an epistemic and ontological extractivist approach. These extractivist practices exploit ILK and wisdom and redefine them from Western logic to transform them into economic capital. Western sciences appropriate indigenous peoples’ ideas by colonising, subsuming, and stripping them of their political radicalism, spirituality, and cosmology. In this regard, agricultural Western scientific knowledge has been used to shape the agro-industrial food system that uses violent technologies and promotes profit-driven economies while creating knowledge apartheid by diminishing Indigenous wisdom and creativity of Mother Earth (Vandana, Citation2016). This looting symbolically and economically excludes Indigenous peoples who possess this knowledge, deprives them of their resources, and destroys their environment (Grosfoguel, Citation2016). This knowledge apartheid ends up appropriating indigenous agroecological knowledge, leaving aside the spirituality and cosmologies on which they are grounded (Figueroa-Helland et al., Citation2018). As discussed above, the decolonial turn offers multiple strategies to counteract this knowledge apartheid.

Decolonising agroecological education is about opening learning spaces for resistance, liberation, and self-determination. It is learning to establish a more reciprocal relationship with mother Earth and all its occupants. It is learning to build a more equitable world so that the communities’ poverty is no longer the result of their land’s abundant resources (Galeano, Citation1988). We cannot limit teaching agroecology to technical aspects to increase organic production for a capitalist market (Méndez et al., Citation2017). Without the political, social, and spiritual components, agroecology is as deprived as an indigenous person is without land, seeds, and community.

Transforming agriculture HE

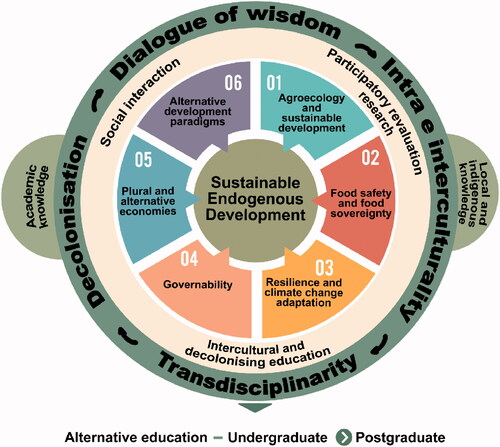

In the following sections, we exemplify how agroecology and decolonisation intertwine in the Programa de Formación Continua Intercultural y Descolonizador – PFCID program. We analyse the PFCID in the light of the five identified analytical dimensions to decolonise HE – methodological, epistemological, ontological, ethical, and socio-political, summarised in .

The PFCID is an educational program developed by the Centro de Investigación Agroecología Universidad Cochabamba (AGRUCO), a research centre that belongs to the agricultural, livestock, and forestry sciences faculty of the Universidad Mayor de San Simon (UMSS). The centre was created in 1985 by an interdisciplinary and multicultural team focusing on agroecology and rural development. For around 30 years, AGRUCO has been developing and implementing an educational program rooted in the Andean cosmovision. The PFCID was born with the idea of dealing with the impacts of the green revolution in Bolivia. But soon, it became a process of mutual learning between the Andean communities and academics from the UMSS, who wanted to activate and motivate the new generations with the continuous sharing of knowledge through the Yachaj-yachachij cycle (learn-teach-learn).

The methodological approach of the PFCID

The PFCID program uses a combination of methodologies strongly connected with the communities and links agroecology with the university’s three pillars. The program is using (i) a Participatory Action Research (PAR) approach, (ii) the revaluation of ILK, (iii) transdisciplinary research, bridging academic disciplines and ILK, and (iv) a project community-based approach to promote social interaction.

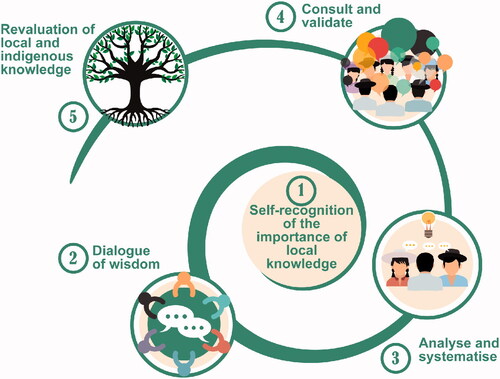

PAR offered the program the possibility of integrating teaching, research, and social interaction with political militancy committed to the local populations’ realities. (Fals-Borda & Rahman, Citation1991). Combining the revaluation of ILK with PAR opened new possibilities for bridging different knowledge systems. Participatory Research for the Revaluation of Indigenous and local knowledge (PRR-ILK) – became the core of PFCID’s methodology. It combines the ideas of PAR and the DS approach. What is innovative about PRR-ILK is the revalorising component, which places the knowledge of communities at the same level as the academic knowledge, putting both in equal dialogue (Tapia Ponce, Citation2016). outlines the PRR-ILK process. First, it does a community self-assessment, highlighting the relevance and pertinence of ILK. The second step consists of establishing a DS by identifying the existing knowledge to be recovered and revalorized. It is followed by the process of analysis and systematisation that later will be presented to communities to be complemented and validated. This validation is carried out among the communities, evaluating the usefulness, effectiveness, and relevance of the knowledge for the local communities. Finally, the knowledge is shared within the communities using different communication forms, like almanacs, posters, booklets.

Figure 1. Outline of PRR-ILK process. Adapted from (AGRUCO, Citation2000).

PFCDI’s students permanently apply the PRR-ILK in their community-based research projects. In the process, students must deal with the complexity of local reality while doing their research. Students will exchange university classrooms for the ayllu (community) and share daily life with local families, learning about their agricultural practices and their culture, beliefs, and way of life. In this process, the community leaders also change their roles, contributing their knowledge and wisdom to the students’ educational process and developing the research projects. Students must present their results to the community and the academic team; both will evaluate their research results.

The implementation of community-based projects facilitated starting a DS with communities and discovering the richness of the Andean cultures. It nourished robust and long-lasting relationships with those communities by searching together for appropriate solutions to the local needs. The program uses agroecology as a vehicle for endogenous and self-sustainable rural development, prioritising people’s visions, values, and potentials of development (Rist et al., Citation2011). Community-based projects require students to think critically about which solutions might be most technically appropriate and how these might (or might not) support community development principles, including traditional values and decision-making processes (Harvey & Russell-Mundine, Citation2019, p. 7).

The epistemic dimension of PFCID

The purpose of PFCID was to initiate a process of academic and research transformation of higher education in Bolivia. The first attempt to materialise the educational strategy was the implementation of extracurricular courses. These courses targeted agronomy students from six Bolivian public universities from the cities of Cochabamba, La Paz, Oruro, Potosí, Tarija, and Chuquisaca. The lessons were given for more than seven years (1990–1997), reaching the best students enrolled in the agronomy faculties of the country. The purpose of the courses was to share experiences and build an intercultural dialogue around their practices.

For PFCID, intracultural education is an earlier process of intercultural dialogue. Intercultural education is not limited to multi or bilingualism. It requires a profound transformation of the whole education system based on the decolonisation of knowledge (Walsh, Citation2010). In other words, while intercultural education seeks students to recognise the social, economic, political, cultural, environmental, and spiritual diversity, intercultural dialogue pursues to promote an encounter of collective identities based on cultural autonomies (Leff, Citation2004) by diversifying and deracialise the curriculum and, at the same time, revitalise ILK.

The PFCID has a training program from the technical level to the doctoral degree that combines ILK and academic knowledge. It has six focal axes: (1) agroecology and sustainable development, (2) food safety and food sovereignty, (3) resilience and climate change adaptation, (4) plural and alternative economies, (5) governability, and (6) alternative development paradigms. In this complex reality, it is not possible to conceive the technical aspects isolated from the economic, socio-cultural, and spiritual issues. The curriculum combines scientific domains such as agroecology, economics, rural sociology with ILK. It incorporates subjects related to Indigenous technologies but also includes spirituality and Andean cosmologies in the study plan. Therefore, the program proposes implementing a transdisciplinary approach involving natural and social sciences and other knowledge systems. The main elements of the program are synthesised in .

Figure 2. Epistemological foundations of PFCID. Adapted from (AGRUCO, Citation2011).

PFCDI offers tailored specialised courses to the youth, men and women adult learners, Indigenous people, farmers, professionals, and civil servants from diverse cultural backgrounds. The students, professors, and practitioners who were following the classes opened new horizons for the educational program, paving the way to the first version of the agroecology master’s degree.

Other formal education is offered to rural and urban undergraduate and postgraduate students. It includes a bachelor’s program, short courses, and a doctoral program. However, the central core of PFCID is the master’s program (10 promotions since 1998). The program wants to reach persons interested in agroecology and Andean culture and want to be the drivers of academic change in HEIs and promoters of social and economic growth.

Alternative and technical education is followed mainly by the adult rural population that did not complete primary school but wanted to follow introductory courses to improve their agroecological activities. The difference between alternative and technical training is that students enrolled in alternative education only require primary education (read and write). In contrast, students enrolled in technical courses need to have a secondary school diploma.

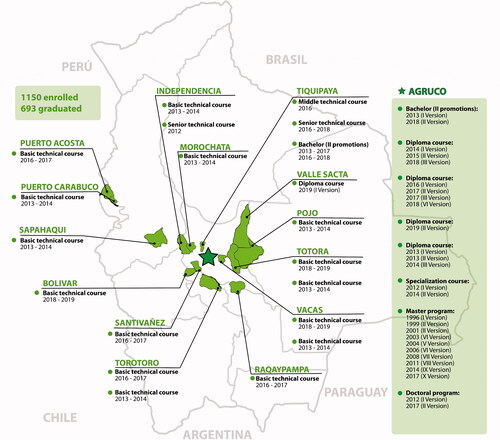

gives an overview of the locations and scope of the modalities offered by PFCID from 1998 until today. Around 1,150 students followed at least one training program. Among them, 536 youth and adults from Indigenous rural communities received tailored alternative and technical courses in their communities. Many of them are working in the municipalities supporting the agricultural sector or are employed by national or international NGOs. A total of 45 students followed the bachelor program, 133 students in the master’s program, and 24 doctoral researchers; however, less than 30% are women. Gender equality is a pending task of the PFCID.

The ontological dimension of PFCID

PFCID goes beyond the training of professionals. For Indigenous peoples, research should not be done if it does not generate benefits and improve the communities’ quality of life (Louis, Citation2007). For this reason, the program adopted the modality of community-based projects not only as an educational strategy but to be reciprocal and accountable to the communities. From an Indigenous perspective, the search for knowledge is considered to be a spiritual journey (Louis, Citation2007, p. 134). However, the emotional, relational, and spiritual have often been marginalised and neglected in academic spaces (Castleden et al., Citation2017; Shahjahan, Citation2005). Therefore, to decolonise HE, we need to start revitalising the spiritual component and incorporate it into the curriculum (Dei, Citation2016).

In the PFCID, honouring cultural protocols was one way to incorporate the spiritual dimension in our praxis. Students not only follow academic courses about Andean epistemologies and ontologies. They are also immersed in daily life with the communities, establishing a relation between the three spheres of life: the material, the social, and the spiritual (Rist & Dahdouh-Guebas, Citation2006). Participants enter in a dialogue with the communities who share their knowledge and their cultural and spiritual wisdom rooted in the harmonious relationship of all beings with Mother Earth.

The ethical dimension of PFCID

Decolonising HE entails as a first step the recognition of the other and the otherness existence. However, there is no existence outside of a co-existence (Gaztambide-Fernández, Citation2012). For Andean people, co-existence is a requirement to maintain balanced, reciprocal, and complementary relationships (Quiroz, Citation2006, p. 60); we exist insofar as we co-exist with our opposite. This co-existence will be possible by building ethical spaces where there is a place for all different knowledge systems. It also implies building equitable relationships based on a pedagogy of solidarity (Gaztambide-Fernández, Citation2012) and justice.

The PFCID contributed to this co-existence process by (i) recovering Andean values, (ii) promoting reciprocal relationships between modern science and ILK through a DS and a transdisciplinary approach, and (iii) re-establishing a responsibility with the other and otherness while reconnecting with the Mother Earth.

The socio-political dimension of PFCID

Building on the previous sections, we consider that a decolonisation process’s ultimate goal is social justice. But social justice cannot exist in a world where other knowledge and other ways of understanding reality are marginalised, delegitimised, and denied. In other words, while social justice is the end, epistemic, ontological justice, ethical liberation, and DS are the means to engage in a collaborative action to transform reality. In the following paragraphs, we introduce some of the PFCID transformations at the academic, social, and political levels.

Academic transformation

Disseminating the academic program offered by the PFCID was possible thanks to (i) the participation of many professors from the Bolivian HEIs, and rural development professionals from GOs and NGOs and mainly the community members who followed the bachelor, master’s and doctoral program of the PFCID; (ii) the approach was built in a participatory way, constructed with community leaders, national and international scholars, practitioners and policymakers from diverse disciplines; (iii) a large amount of academic and non-academic publications have been a reference for many scholars working with Indigenous Andean communities.Footnote1

The PFCID managed to establish interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary work at UMSS, signing agreements with social communication, sociology, food engineering, industrial engineering, economics, and auditing faculties. This collaboration allowed us to carry on research and developmental projects, also creating opportunities for graduation for students from the different faculties with the modality of a joint bachelor’s and master’s thesis. It is noteworthy that many community students received grants to continue their higher education through PFCID projects.

Social transformation

The new Bolivian Political Constitution, in its article 93, numeral IV (Estado Plurinacional de Bolivia, Citation2009), offers the possibility for HEIs to establish programs outside the university. These programs, called desconcentracion academica, implement training and teaching according to the local and Indigenous people’s needs in their communities. The PFCID’s bachelor’s program in endogenous development and agroecology has been developed within this framework. The bachelor’s program allowed students to undertake their higher education in their communities. This modality reduces the social, cultural, and economic costs of internal migration. With the bachelor’s program’s modular system, students complete three continuous weeks of face-to-face courses and three weeks in their rural communities of origin. This system leads them to carry out their productive activities as well as non-face-to-face studies. Another meaningful impact is related to students’ knowledge in the training process, which is continuously incorporated into the curriculum and allows the development of new local technology based on the ILK. Some examples of the contributions of Indigenous students participating in the PFCID are the development of local technology for the production and processing of cañahua, a native cereal source of proteins and minerals. They were involved in a development project to improve pirhuas (traditional warehouses for saving crops). Also, in a project about chuño (dehydrated potato) production, revaluing ancestral potato production, and storage techniques (AGRUCO, Citation2011).

Another social transformation was the empowerment of the local communities. Some community leaders who have been trained within PFCID now hold influential positions in municipal administration. It is the case for Fabian Choque, a community leader from Jachapampa, who currently serves as Deputy Mayor of the Challa district in the Tapacarí municipality. Another example is Donato Maldonado, president of the FUPAGEMA Foundation (Foundation for Environmental Management) in the Independencia municipality.

The participation of municipal governments and social organisations, both in the planning and implementation of PFCID, was a success factor that allowed a timely response to local communities’ demands. It also helped to provide further scope to actions in the municipalities, since in some cases, local governments and local NGOs participated in the co-financing of the projects. This dynamic generated with local knowledge-holders allowed the Bolivian university to be closer to the local societal problems.

Political transformation

According to PAR, an intervention should include academic or research aspects and be socio-politically oriented (Fals-Borda & Rahman, Citation1991). The political transformation of PFCID occurred at three levels: (1) public policy, (2) management instruments (programs, projects, and methodologies), and (3) budget allocation to implement the regulations and management tools.

For the first level, public policy, PFCID supported the process of the Constituent Assembly of Bolivia, which aimed to insert the vision of Indigenous peoples into the issue of biodiversity, natural resources, land reform, community justice, and education. The AGRUCO team, together with Indigenous and political leaders, participated in different Commissions. They managed to incorporate critical elements of the PFCID approach in Bolivian legislation, including the National Constitution (2009), the National Education Law (2010), Mother Earth Law (2013), Productive Revolution Law (2013), Organisations Economics Law (2013), Control and Social Participation Law (2015), Integrated State Planning Law (2016); and supreme regulatory decrees, departmental, Indigenous and municipal laws.

For the management instruments, the program took part in a territorial planning project. Their role was to advise on the elaboration of the territorial plans of 24 municipalities in Bolivia. The team worked with NGOs and local leaders, adjusting and contextualising territorial planning methodologies (AGRUCO, Citation2011).

At the local level, one example is a project with an association of agroecological producers in the municipality of Totora. This community association was awarded the provision of school breakfasts at the municipal level (1 million BOB per year). The project has been running for three years (2017–2019), supporting the association’s development and offering healthy food for young people (AGRUCO, Citation2011).

PFCID challenges

PFCID has made a significant contribution to how a decolonising agroecology curriculum may impact communities, students and teachers, opening new opportunities and reflections for the educational system. However, there still a lot of hurdles to overcome if we want to expand this experience.

The PFCID as an integral approach required the implementation of a community-based strategy, which, in turn, needs economic resources. In Bolivia, as in almost all of Latin America, few resources are devoted to scientific research, and those available come from foreign institutions (Camacho et al., Citation2015). Others come from royalties from exploiting various natural resources, mainly mining or loans facilitated by the Inter-American Development Bank (UNESCO, Citation2015). It cannot be said which of the options is the worst. It is a paradox that research depends on the looting and appropriation of natural resources. At the same time, internationalisation represents a constant threat to decolonisation (Sultana, Citation2019) as loans strongly influence national research and innovation policies (UNESCO, Citation2015). Still, the PFCID had no other possibility of financing its activities than with money from these three sources and has been able to make the most of these resources. The problem is that hacking the system and using its resources carries high risks. As explained by Andreotti et al. (Citation2015), there can be a time when it is difficult to recognise who is hacking whom.

As mentioned above, the PFCID program tried to incorporate indigenous and local communities leaders in the evaluation processes. Maintaining and institutionalising this type of practice in academic structures is much more complicated. It is necessary to invest time and resources. Following most funding schemes’ logic, community participation is often considered a community contribution to the project. Paradoxically it is difficult to grant a remuneration to a community expert, which is not the case for academic experts who can be hired and even paid higher wages if they are foreigners.

Although the Bolivian national constitution promotes decolonisation at all levels, the strict structures of higher education institutions and Western scientific knowledge’s supremacy prevent a change at the institutional level. In the 30 years of experience of the program, we have seen that senior professors and mainly those who have been trained under a Western positivist education are the most reluctant to change. Although the PFCID program has tried to give equal value to the different knowledge systems, incorporating cultural and spiritual elements has generated reluctance by academics that still consider ILK as data to be validated by scientific knowledge (Whyte, Citation2018). Therefore, it is necessary to continue offering a decolonised education to the new generations and engage senior professors in the process.

From the professors’ perspective, they have to deal with limited time, resources, and institutional support. Many academics have hourly contracts, and full-time professors have a considerable teaching load limiting their involvement in research and social interaction activities. Another issue is that the project-based approach demands a lot of time and effort that not all professors are willing to pursue.

Finally, since the coloniality of being is a result of the effects of colonisation’s living experience (Maldonado-Torres, Citation2016), the experience of many Indigenous scholars in Bolivia is related to the loss of their language, their culture, and ancestral knowledge. Many of these Indigenous people that until recently, have been denied their political and cultural existence, ended up rejecting their indigenous condition and all that is related to it (Rivera, Citation2015). Therefore, many efforts are needed to decolonise the being, not only the knowledge production.

Discussion

The present study investigated linking two counter-hegemonic forces: agroecology and the decolonial turn. What are the insights gained by connecting them to transform knowledge production? And what is the role of DS in this transformation? As explained earlier in this article, the DS can be used as a tool to develop (awake) historical and collective consciousness to connect diverse knowledge systems and break with the HE monologues (Moreno-Cely et al., Citation2021). It opens the avenues to imagine alternative futures of a decolonised education that put in dialogue scientific theories developed by diverse knowledge systems and consider equally ILK and wisdom, including their social, cultural, environmental, and spiritual aspects. This equal footing could be the only way to end the knowledge apartheid (Visvanathan, Citation2009) imposed by the Western colonial approach. However, it is a challenge for ILK that has been silenced and diminished for decades. Therefore, it is necessary to create the conditions for the Indigenous and local communities to re(belief) and re(valorise) their ancestral knowledge (Andreotti et al., Citation2015). To this aim, the PRR-ILK method could play an essential role in revitalising ILK and bring it to the HE spheres.

Combining cultural, political and spiritual elements into academic training is imperative for decolonising agriculture education in particular and HE in general. This article offers methodological, epistemic, ontological, ethical and socio-political strategies to decolonise HE and simultaneously re(valorise) ILK instead of instrumentalising it (Ahenakew, Citation2016). The aspiration is to lead to substantial transformations and building an epistemic pluriverse (Grosfoguel, Citation2012), as shown in the PFCID program.

As academics, we have an incredible responsibility in the transformation of HE. It is in our hands to revitalise and value ILK to motivate them to share their knowledge with us through the Yachaj-yachachij cycle (learn-teach-learn). Embracing complexity and uncertainty is the first step, but above all, we have a duty to revive ancestral cultures and sciences that have been diminished by Western science. A diálogo de saberes can help us promoting this co-existence of diverse knowledge systems and decolonising HEIs. However, in parallel, we need to continue to address the multiple violent relations that constitute the ‘Modern/Colonial Capitalist/Patriarchal Western-centric/Christian-centric World-System’(Grosfoguel, Citation2012).

Concluding thoughts

This contribution sought to highlight the possibilities offered by the dyad agroecology and decolonial turn to open new paths to engage in a collaborative process for multiple knowledge systems’ co-existence. The Latin-American diálogo de saberes approach demonstrated to be an essential tool decolonising knowledge, power, and being, through the recognition and revitalisation of ILK, creating new spaces of diversity and transformation. It confirmed that dialogue between different knowledge systems is possible and necessary to transform agroecological education and higher education as a whole. This dialogue of wisdom (in plural) has profound implications across the higher education system and how we produce and use knowledge to advance substantial societal transformations. By sharing our PFCID experience, we wanted to illustrate how social and political struggles are closely related to science and that engaged scholars can impact no only education in the classroom, but also policy and society at large. We argue that decolonising HE requires structural changes in the methodological, epistemological, ontological, ethical and socio-political aspects (). Acknowledging that there are many challenges but the benefits, even the smallest, compensate the efforts. Decolonising HE is a process under construction, neither pure nor perfect but needs collective actions’ engagement and self and collective reflexivity to explore alternative paths to keep it growing. Although many might consider this path utopian, we believe that it is worth trying. As Eduardo Galeano, the Uruguayan writer, said, ‘the point of a utopia is to keep walking.’

Acknowledgments

We want to thank Kim Hardie for the proofreading.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Adriana Moreno Cely

Adriana Moreno-Cely is a Colombia activist-researcher based in Belgium. Her research interest includes collaborative and participatory research approaches, decolonizing knowledge production by bridging diverse knowledge systems and building sustainable territories through re-valuing Indigenous and local knowledge.

Dario Cuajera-Nahui

Dario Cuajera-Nahui is currently a biostatistics and agroecology professor and PhD researcher at the University Mayor de San Simon in Bolivia. His research interests are socio-ecological resilience and territorial planning.

Cesar Gabriel Escobar-Vasquez

Cesar Gabriel Escobar-Vasquez is currently a Rural Sociology professor and PhD researcher at the University Mayor de San Simon in Bolivia. His research interests are territorial planning, governance and local, sustainable development.

Domingo Torrico-Vallejos

Domingo Torrico-Vallejos is an economist at the Universidad Mayor of San Simón. Specialist in rural economy, dialogue of wisdom, and revaluation of indigenous and local knowledge. He is currently working at the Agroecology Center Universidad Cochabamba (AGRUCO) as a project developer and professor of agricultural economics at the Universidad Mayor of San Simón. His research interests are plural and alternative economies and risk management and natural disasters.

Josue Aranibar

Josue Aranibar Romero received the B.Sc. in Social communication. He is currently working towards a master’s degree in agroecology. Specialist in territorial planning and territorial development. With experience in dialogue of wisdom and revaluation of indigenous and local knowledge. He worked as a consultant and researcher at the Agroecology Center Universidad Cochabamba (AGRUCO). He currently works as a consultant and professor of Anthropology in Social Communication at the Universidad Mayor of San Simón. His research interests include transdisciplinary and participatory revalorization research approaches.

Reynaldo Mendieta-Perez

Reynaldo Mendieta-Perez holds a B.Sc. Eng. Degree in Agronomy from Universidad Mayor of San Simón and has a master's degree in agroecology and dialogue of wisdom from the same university. Specialist in agroecology, soil conservation, and has been working with rural communities giving agronomy technical support and training local leaders in agroecological issues. His research interests are participatory methodologies for sustainable development, dialogue of wisdom, revaluation of local knowledge, and transdisciplinarity. He is currently a professor of Agricultural Extension at the Faculty of Agricultural and Livestock Sciences of the Universidad Mayor of San Simón.

Nelson Tapia-Ponce

Nelson Tapia-Ponce PhD is a specialist in Agroecology and family agriculture. He is currently a professor and coordinator of the Agroecology Center Universidad Cochabamba (AGRUCO) postgraduate program at the University Mayor de San Simon in Bolivia. His areas of interests are agroecology and Andean culture.

Notes

References

- AGRUCO. (2000). Políticas y Estrategias de la Investigación en Agroecologia y Revalorización del Saber Local. AGRUCO.

- AGRUCO. (2011). Agroecologia y desarrollo endogeno sustentable para vivir bien: 25 años de la experiencias de Agruco. http://biblioteca.clacso.edu.ar/Bolivia/agruco/20170928052016/pdf_223.pdf

- Ahenakew, C. (2016). Grafting indigenous ways of knowing onto non-indigenous ways of being: The (underestimated) challenges of a decolonial imagination. International Review of Qualitative Research, 9(3), 323–340. doi:10.1525/irqr.2016.9.3.323

- Ahenakew, C., de Oliveira Andreotti, V., Cooper, G., & Hireme, H. (2014). Beyond epistemic provincialism: De-provincializing indigenous resistance. Alternative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples, 10(3), 216–231. doi:10.1177/117718011401000302

- Altieri, M. A., & Nicholls, C. I. (2017). Agroecology: A brief account of its origins and currents of thought in Latin America. Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems, 41(3–4), 231–237. doi:10.1080/21683565.2017.1287147

- Altieri, M. A., & Toledo, V. M. (2011). The agroecological revolution in Latin America: Rescuing nature, ensuring food sovereignty and empowering peasants. Journal of Peasant Studies, 38(3), 587–612. doi:10.1080/03066150.2011.582947

- Andreotti, V., Stein, S., Ahenakew, C., & Hunt, D. (2015). Mapping interpretations of decolonization in the context of higher education. Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society, 4(1), 21–40.

- Archila, M. (2017). Cómo entender el diálogo de saberes. Lasaforum, 48(2), 61–62. https://forum.lasaweb.org/files/vol48-issue2/On-LASA2017-1.pdf

- Ardelt, M. (2004). Wisdom as expert knowledge system: A critical review of a contemporary operationalization of an ancient concept. Human Development, 47(5), 257–285. doi:10.1159/000079154

- Bhambra, G., Gebrial, D., & Nişancıoğlu, K. (2018). Decolonising the university (G. Bhambra, D. Gebrial, & K. Nişancıoğlu (eds.)). Pluto press.

- Burman, A. (2016). Damnés realities and ontological disobedience notes on the coloniality of reality in higher education in the Bolivian Andes and Beyond. In R Grosfoguel, R Hernández & E Rosen Velásquez (eds), Decolonizing the Westernized University: Interventions in Philosophy of Education from Within and Without. Lexington Books, Lanham, pp. 71.

- Camacho, R., Villegas, M., & Mendizabal, C. (2015). Entre la realidad económica y la utopía académica. Revista Cubana de Educacion Superior, 34(1), 81–106.

- Castleden, H., Hart, C., Cunsolo, A., Harper, S., & Martin, D. (2017). Reconciliation and relationality in water research and management in Canada: Implementing indigenous ontologies, epistemologies and methodologies. In Water policy and governance in Canada (Issue November 2016, pp. 69–95). Springer.

- Castro-Gómez, S., & Grosfoguel, R. (2007). Giro decolonial, teoría crítica y pensamiento heterárquico. In S. Castro-Gómez & R. Grosfoguel (Eds.), El giro decolonial Reflexiones para una diversidad epistémica más allá del capitalismo global (pp. 9–24). Siglo del Hombre Editores.

- Chilisa, B. (2017). Decolonising transdisciplinary research approaches: An African perspective for enhancing knowledge integration in sustainability science. Sustainability Science, 12(5), 813–827. doi:10.1007/s11625-017-0461-1

- Cleaver, H. M. Jr, (1972). The contradictions of the green revolution. The American Economic Review, 62(1), 177–186. doi:10.2307/1821541

- David, C., & Bell, M. M. (2018). New challenges for education in agroecology. Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems, 42(6), 612–619. doi:10.1080/21683565.2018.1426670

- Dei, G. J. S. (2016). Decolonizing the University: The challenges and possibilities of inclusive education. Socialist Studies, 11(1), 23–61. DOI: https://doi.org/10.18740/S4WW31

- Dussel, E. (1998). Ética de la liberación en la edad de la globalización y de la exclusión. Editorial Trotta.

- Estado Plurinacional de Bolivia. (2009). Constitución Política (p. 107). Gaceta oficial de Bolivia.

- Fals-Borda, O., & Rahman, M. (1991). Action and knowledge: Breaking the monopoly with participatory action-research (O. Fals-Borda & M. Rahman (eds.)). The Apex Press.

- FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP, & WHO. (2020). The state of food security and nutrition in the world 2020. Transforming food systems for affordable healthy diets. FAO. doi:10.4060/ca9692en

- Figueroa-Helland, L., Thomas, C., & Aguilera, A. (2018). Decolonizing food systems: Food sovereignty, indigenous revitalization, and agroecology as counter-hegemonic movements. Perspectives on Global Development and Technology, 17(1–2), 173–201. doi:10.1163/15691497-12341473

- Galeano, E. (1988). Las venas abiertas de America Latina. Siglo XXI Editores.

- Gaztambide-Fernández, R. A. (2012). Decolonization and the pedagogy of solidarity. Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society, 1(1), 41–67.

- Ghiso, A. (2000). Potenciando la diversidad: Diálogo de saberes, una practica hermeneutica colectiva. Colombia Utopía Siglo, 21, 43–54.

- Giraldo, O. F., & Rosset, P. M. (2018). Agroecology as a territory in dispute: Between institutionality and social movements. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 45(3), 545–564. doi:10.1080/03066150.2017.1353496

- Gliessman, S. R. (2020). Transforming food and agriculture systems with agroecology. Agriculture and Human Values, 37(3), 547–548. doi:10.1007/s10460-020-10058-0

- Grosfoguel, R. (2012). The dilemmas of ethnic studies in the United States: Between liberal multiculturalism, identity politics, disciplinary colonization, and decolonial epistemologies. Human Architecture: Journal of the Sociology of Self-Knowledge, 10(1), 81–89. http://scholarworks.umb.edu/humanarchitecturehttp://scholarworks.umb.edu/humanarchitecture/vol10/iss1/9

- Grosfoguel, R. (2016). Del «extractivismo económico» al «extractivismo epistémico» y «extractivismo ontológico»: una forma destructiva de conocer, ser y estar en el mundo. Tabula Rasa, 24(24), 123–143. doi:10.25058/20112742.60

- Harvey, A., & Russell-Mundine, G. (2019). Decolonising the curriculum: Using graduate qualities to embed Indigenous knowledges at the academic cultural interface. Teaching in Higher Education, 24(6), 789–808. doi:10.1080/13562517.2018.1508131

- Leff, E. (2004). Racionalidad ambiental y diálogo de saberes. POLIS, Revista Latinoamericana, 7, 13–40. http://journals.openedition.org/polis/6232

- Louis, R. P. (2007). Can you hear us now? Voices from the margin: Using indigenous methodologies in geographic research. Geographical Research, 45(2), 130–139. doi:10.1111/j.1745-5871.2007.00443.x

- Maldonado-Torres, N. (2016). Outline of ten theses on coloniality and decoloniality. Foundation Frantz Fanon.

- Maldonado-Torres, N. (2019). Ethnic studies as decolonial transdisciplinarity. Ethnic Studies Review, 42(2), 232–244. doi:10.1525/esr.2019.42.2.232

- Martínez-Torres, M. E., & Rosset, P. M. (2014). Diálogo de saberes in La Vía Campesina: Food sovereignty and agroecology. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 41(6), 979–997. doi:10.1080/03066150.2013.872632

- McCune, N., & Sánchez, M. (2019). Teaching the territory: Agroecological pedagogy and popular movements. Agriculture and Human Values, 36(3), 595–610. doi:10.1007/s10460-018-9853-9

- Méndez, V. E., Bacon, C. M., & Cohen, R. (2013). Agroecology as a transdisciplinary, participatory, and action-oriented approach. Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems, 37, 3–18. doi:10.1080/10440046.2012.736926

- Méndez, V. E., Caswell, M., Gliessman, S. R., & Cohen, R. (2017). Integrating agroecology and participatory action research (PAR): Lessons from Central America. Sustainability, 9(5), 705–719. doi:10.3390/su9050705

- Moreno-Cely, A., Cuajera-Nahui, D., Escobar-Vasquez, C., Vanwing, T., & Tapia-Ponce, N. (2021). Breaking monologues in collaborative research: Bridging knowledge systems through a listening-based dialogue of wisdom approach. Sustainability Science, 16(3), 919–913. doi:10.1007/s11625-021-00937-8

- Quiroz, V. (2006). Pensamiento andino y critica postcolonial. Un estudio de Rosa Cuchillo de Oscar Colchado. Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos.

- Restrepo, P. (2014). Legitimation of knowledge, epistemic justice and the intercultural university: Towards an epistemology of ‘living well’. Postcolonial Studies, 17(2), 140–154. doi:10.1080/13688790.2014.966416

- Rist, S., Boillat, S., Gerritsen, P., Schneider, F., Mathez-Stiefel, S., & Tapia, N. (2011). Endogenous knowledge: Implications for sustainable development. In U. Wiesmann & H. Hurni (Eds.), Research for sustainable development: Foundations, experiences, and perspectives. Perspectives of the Swiss National Centre of Competence in Research (NCCR) NorthSouth (pp. 119–146).University of Bern.

- Rist, S., & Dahdouh-Guebas, F. (2006). Ethnosciences – A step towards the integration of scientific and indigenous forms of knowledge in the management of natural resources for the future. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 8(4), 467–493. doi:10.1007/s10668-006-9050-7

- Rivera, S. (2012). Ch’ixinakax utxiwa: A reflection on the practices and discourses of decolonization. South Atlantic Quarterly, 111(1), 95–109. doi:10.1215/00382876-1472612

- Rivera, S. (2015). Violencia e interculturalidad Paradojas de la etnicidad en la Bolivia de hoy. Revista Telar Del Instituto Interdisciplinario de Estudios Latinoamericanos, 10(15), 49–70. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=5447270

- Rosset, P. M., Barbosa, L. P., Val, V., & McCune, N. (2021). Pensamiento Latinoamericano Agroecológico: The emergence of a critical Latin American agroecology? Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems, 45(1), 42–23. doi:10.1080/21683565.2020.1789908

- Salinas, C. J. (2017). Transforming academia and theorizing spaces for Latinx in higher education: Voces perdidas and voces de poder. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 30(8), 746–758. doi:10.1080/09518398.2017.1350295

- Santos, B. d S. (2014). Epistemologies of the South. Justice against epistemicide. Routledge.

- Shahjahan, R. A. (2005). Spirituality in the academy: Reclaiming from the margins and evoking a transformative way of knowing the world. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 18(6), 685–711. doi:10.1080/09518390500298188

- Simpson, L. B. (2014). Land as pedagogy: Nishnaabeg intelligence and rebellious. Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society, 3(3), 1–25.

- Smith, L. T. (2012). Decolonizing methodologies: Research and indigenous people. In Zed Books (2nd ed.). Zed Books.

- Stein, S. (2019). Beyond higher education as we know it: Gesturing towards decolonial horizons of possibility. Studies in Philosophy and Education, 38(2), 143–161. doi:10.1007/s11217-018-9622-7

- Sultana, F. (2019). Decolonizing development education and the pursuit of social justice Farhana Sultana. Human Geography, 12(3), 31–46. doi:10.1177/194277861901200305

- Tapia Ponce, N. (2016). El diálogo de saberes y la investigación participativa revalorizadora: Contribuciones y desafíos al desarrollo sustentable. In S. Rist & F. Delgado B. (Eds.), Ciencias, diálogo de saberes y transdisciplinariedad. Aportes teórico metodológicos para la sustentabilidad alimentaria y del desarrollo (pp. 89–118). Plural Editores.

- Todd, Z. O. E. (2016). An indigenous feminist’s take on the ontological turn: ‘Ontology’ is just another word for colonialism. Journal of Historical Sociology, 29(1), 4–22. doi:10.1111/johs.12124

- Tuck, E., & Wayne Yang, K. (2019). Indigenous and decolonizing studies in education. In L. Tuhiwai Smith, E. Tuck, & K. Wayne Yang (eds.), Mapping the long view. Routledge.

- Tuck, E., & Yang, W. (2012). Decolonization is not a metaphor. Decolonization, Indigeneity, Education, & Society, 1(1), 1–40.

- UNESCO. (2015). UNESCO science report: Towards 2030. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000235406

- United Nations. (2015). Transforming our world: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. United Nations.

- Vandana, S. (2016). Who really feeds the World? The failures of agribusiness and the promise of agroecology. North Atlantic Books.

- Visvanathan, S. (2009). The search for cognitive justice. Social Science Nomad. http://www.india-seminar.com/2009/597.htm

- Walsh, C (2010). Interculturalidad Critica y Educación Intercultural. In Viaña, L. Tapia & C. Walsh (Eds.), Construyendo Interculturalidad Crítica. Bolivia, Instituto Internacional de Integración del Convenio Andrés Bello, p. 75–96.

- Wezel, A., Bellon, S., Doré, T., Francis, C., Vallod, D., & David, C. (2009). Agroecology as a science, a movement and a practice. Agronomy for Sustainable Development, 29(4), 503–515. doi:10.1051/agro/2009004

- Whyte, K. (2018). What do indigenous knowledges do for indigenous peoples? In M. Nelson & D. Shilling (Eds.), Traditional ecological knowledge: Learning from indigenous practices for environmental sustainability (Issue March, pp. 57–82). Cambridge University Press.

- Wu, J., Eaton, P. W., Robinson-Morris, D. W., Maria, F. G., Han, S., Wu, J., Eaton, P. W., Robinson-Morris, D. W., & Maria, F. G. (2018). Perturbing possibilities in the postqualitative turn: Lessons from Taoism (道) and Ubuntu. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 31(6), 504–516. doi:10.1080/09518398.2017.1422289