Abstract

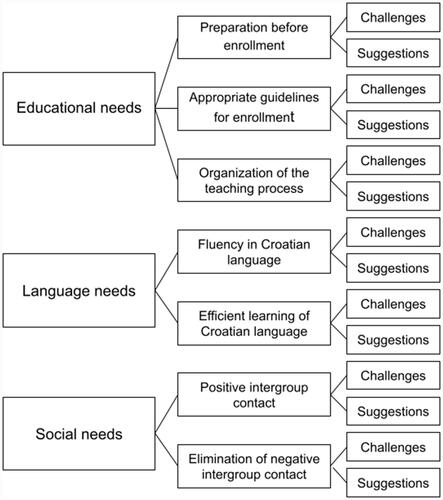

Existing research on the education of refugee children has been conducted in countries with a longstanding tradition of refugee integration. The aim of this study was to gain insight into the integration process of refugee children in Croatian schools. Croatia is a small EU country with limited experience in refugee integration. The phenomenological approach was used to examine the experiences and perspectives of the relevant actors. Interviews and focus group discussions were conducted with refugee children (N = 15), their parents (N = 5), classmates (N = 50), and school staff (N = 54) from six elementary schools in Zagreb. Data analyses suggested three general needs: educational, language, and social, each of them connected to more specific needs, challenges, and suggestions. The results of the study are discussed within the Schachner et al. (Citation2017) framework of immigrant adolescents’ acculturation.

Introduction

This study explores school integration among refugeeFootnote1 children, expanding on previous literature by adding two major advantages: it is carried out in a country with little experience in refugee integration and focuses on the perceptions of different actors in the integration process.

The majority of work examining school integration of refugee children has been conducted in traditionally preferred destination countries, such as the USA, Canada, and Australia, as well as Scandinavian and Western-European countries (Lunneblad, Citation2017; Madziva & Thondhlana, Citation2017; Nakeyar et al., Citation2018; Pastoor, Citation2015). These countries are ethnically and culturally heterogeneous and have years of experience in refugee and migrant integration, including their schooling. Furthermore, recent research has also focused on countries with a large influx of refugees, such as Turkey, Greece, Lebanon, and Jordan (Aydin & Kaya, Citation2017; Crul et al., Citation2019; Salem, Citation2022; Şeker & Sirkeci, Citation2015). In contrast, the number of refugees in Croatia is not large, since it is not viewed as a preferred destination country. Although most refugees arriving in Croatia come from Syria and Iraq, the Arabic-speaking community is still small and the local community remains quite culturally homogenous. As a consequence, schools present a non-diverse environment and are focused on the mainstream culture, which can impede the integration process of refugee children (Schachner et al., Citation2016; Thijs & Verkuyten, Citation2014). In the school year 2019/20, a total of 28 children were enrolled in kindergartens, 32 in primary schools, and eight in secondary schools in Zagreb (I. Prpić, personal communication, January 23, 2020). However, elementary schools, as the key stakeholders in the integration process of children (Čorkalo Biruški et al., Citation2019), are not experienced in teaching foreign speakers, let alone refugees. While there are several laws and regulations prescribing that refugee children need to be included in the regular education system and attend Croatian language courses (Official Gazette No. 70/15), recent research in Croatia has shown that more could be done in the implementation of these legally prescribed rights in practice (Ajduković et al., Citation2019; Šeneta, Citation2019). Policies and procedures related to the schooling of children who do not speak the Croatian language exist, but they are rarely employed. Hence, practices from more diverse countries can be difficult to implement in the Croatian context. Studying the integration process in “new” host countries becomes ever more important since recent reforms of the Common European Asylum System (European Commission, Citation2021) highlight solidarity and responsibility sharing in refugee resettlement and integration between all EU countries.

Research conducted in various contexts has identified some of the needs in the integration of refugees, as viewed from the lens of teachers. For example, teachers of refugee children in Turkey (Şeker & Sirkeci, Citation2015) described challenges related to education (mastering the language and academic underachievement), peer relations (social and cultural integration and communication), and parents (attitudes towards education and integration problems). American teachers indicated that formal teacher training lacks specific information on working with refugees and highlighted the importance of communicating with parents and the initial preparation of both teachers and refugee children for their enrollment (Nagasa, Citation2014), and the Swedish experience also suggests that teacher preparation is needed to ensure adequate support to refugee students (Nilsson & Axelsson, Citation2013; Svensson, Citation2019). From the children’s perspective, it is also important to establish close intergroup relations, which are essential for their well-being. Intergroup friendships can help students integrate into a local community (Mohamed & Thomas, Citation2017), and improve the social competence of their host-society peers (Cameron & Turner, Citation2016), while the lack of meaningful interactions with domicile peers can lead to feelings of isolation and “not belonging” in a host country (Guo et al., Citation2019). Finally, all studies conducted thus far emphasize the importance of language as a precondition to successful integration (Aydin & Kaya, Citation2017; Hek, Citation2005b; Madziva & Thondhlana, Citation2017; Nagasa, Citation2014; Nakeyar et al., Citation2018; O’Toole Thommessen & Todd, Citation2018; Şeker & Sirkeci, Citation2015).

In the line of research on the acculturation of immigrants, when studying the needs in the process of school integration of refugees one should consider relevant indicators of successful integration (Arends-Tóth & van de Vijver, Citation2006). Focusing primarily on the acculturation of immigrant youth, Schachner et al. (Citation2017) developed a framework that encompasses both developmental and acculturation influences, describing acculturation conditions (school, family, and immigrant group) predicting ethnic and mainstream acculturation orientations, which in turn predict acculturation outcomes, i.e. psychological well-being and sociocultural competence. For immigrant (and refugee) children school represents the main source of interaction with the host-society culture. Children’s experiences in the school context are thus particularly important for sociocultural outcomes—academic achievement, host-society language skills, and friendships with host-society peers (Schachner et al., Citation2017). These outcomes are closely related—for example, language fluency is crucial both for success in school and for the development of closer relations with peers, while children with more host-community friends tend to do better in school (Motti-Stefanidi et al., Citation2012). Therefore, the present study will explore the needs of refugee children’s school integration, which, if left unaddressed, present a barrier to achieving sociocultural competence.

Studies examining these issues are mostly conducted with particular groups in the school integration process, focusing exclusively on the perspectives of refugee children (Bartlett et al., Citation2017; Blanchet-Cohen et al., Citation2017), their parents (Cun, Citation2020; Parker, Citation2016) or school staff (Aydin & Kaya, Citation2017; Şeker & Sirkeci, Citation2015). To our knowledge, there is no research that aims to attain an overall understanding of the issue by including children, their parents, peers, and school staff simultaneously. While refugee children are the main focus of this study, their parents are also recognized as key figures in observing and supporting integration, a notion emphasized by previous studies advocating a family-centered approach to integration (Deng & Marlowe, Citation2013; Hek & Sales, Citation2002; Nagasa, Citation2014). Finally, integration is a two-way process in which the host-community also plays an active role (Ager & Strang, Citation2008). Host-society peers, teachers, and other school staff can facilitate integration, observe obstacles and suggest improvements. Consistencies in the perspectives of these different groups can represent a form of data-source triangulation (Denzin, Citation1978) and point to overarching issues in school integration, while discrepancies in their views can provide a deeper understanding of the nature of this bi-directional process by demonstrating differences in the roles adopted by various stakeholders, the importance given to various issues and potential misunderstandings across stakeholder groups.

Therefore, this study aimed to explore the needs, challenges, and suggestions of relevant actors in the integration of refugee children into elementary schools in Croatia, a country with little experience in educating children of other cultural origins. Specifically, our research questions were as follows: (1) What are the main needs of various actors in the process of school integration of refugee children? (2) What challenges do these actors face during the integration process? (3) What can be done to overcome these challenges?

Method

Research design overview

The present study was conducted in six elementary schools in Zagreb, where most refugees arriving in Croatia live. We follow a phenomenological approach, focusing on lived experiences of the participants (Manen, Citation1997) with different roles in the school integration process. Therefore, to explore the needs, challenges, and suggestions in the integration of refugee children in schools, we interviewed refugee children and their parents, classmates, and school staff. The data was collected using semi-structured interviews with refugees and focus group discussions (FGD) with host-community members. The study was approved by the IRB of the Department of Psychology, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Zagreb.

Study participants

We interviewed 15 refugee children aged between eight and fifteen (M = 11,47 years, SD = 2,39), seven of which were girls. These 15 children made up about 50% of the population of refugees enrolled in Zagreb elementary schools at the time of the study (I. Prpić, personal communication, January 23, 2020). The children predominantly arrived from Iraq and Syria, but also other Middle Eastern countries. All the children spoke Arabic as their native language. Six children were relocated to Croatia from other EU countries in accordance with the Dublin III regulation,Footnote2 six arrived through family reunification and three through resettlement programs from Turkey. At the time of data collection, all the children had already been granted international protection and most had moved into private accommodation. All the children had been living in Croatia for at least a year (up to four years).

To gain deeper insight into refugee children’s social relationships with their peers, we conducted 7 FGDs with 50 host-society children (27 girls) aged 8–14 years, who were classmates of at least one refugee child.

We also conducted 8 FGDs with 49 teachers who had experience in teaching a class with at least one refugee child and one FGD with four school pedagogues and a psychologist from the participating schools. Because the information obtained from teachers, pedagogues, and psychologists were quite similar, they are presented together (N = 54). Most participants were women (N = 51) and their average age was 41.25 years (SD = 11.25).

Finally, we conducted interviews with five parents (three mothers and two fathers) of the refugee children participating in the study. They had all been granted asylum and had been living in Croatia for one to three years. All parents were employed at the time of the study and one was a single parent ().

Participant recruitment

The present study used a purposive recruitment strategy focused primarily on obtaining a diverse sample of refugee children. Information about the number and placement of refugee children in elementary schools in Zagreb was obtained from various governmental and city offices and NGOs and by contacting all elementary schools in the city. Schools were selected according to the characteristics of their students, which enabled the recruitment of gender- and age-balanced samples of refugees. All six invited schools agreed to participate in the research. The recruitment of school teachers and domicile pupils was coordinated with the help of school pedagogues and psychologists in accordance with the predefined criteria. They helped in selecting talkative domicile pupils (both boys and girls), half of whom were close to their refugee peers and half who were not as close. They also recommended teachers experienced in working with refugees. Parents of children in the sample were recruited through the participating schools via Arabic-language letters being sent home. Two contacted parents refused to participate (due to lack of time or interest) and two interviews were cancelled because of the COVID-19 restrictions.

Written (parental) consent was obtained for all the participants via letters sent through the school. For refugee parents, consent forms were provided in Arabic. All participants were informed that the study’s purpose was to gain insight into the process of refugee children’s school integration, explained in an age-appropriate way.

Data collection

The study took place between November 2019 and March 2020. Protocols for interviews and FGDs were designed based on previous research (Hek, Citation2005a; Kenny, Citation2007; Parker, Citation2016; Rana et al., Citation2011) and relevant contextual experiences. Although all the participants responded to questions about school integration of refugee children, protocols differed slightly depending on their role (see Table A in Supplemental Materials for a detailed overview of the questions asked). The main topics covered were: everyday experiences in school, language, and communication, attitudes towards school, and social relationships. Adult participants also commented on school enrollment procedures.

The participants were guaranteed complete confidentiality. Interviews with refugee children and FGDs with their peers and teachers were organized in the schools, while interviews with parents and one FGD with school psychologists and pedagogues took place at the Department of Psychology. The average length of the interviews was 30 min, while FGDs lasted for ∼45 min. The first four authors conducted the interviews and FGDs. We acknowledge the researchers’ position of outsiders when interviewing refugee children and parents; nevertheless, we relied heavily on our extensive experience in working with ethnic minorities and the refugee population as well as on mutual reflections and insights we had during the interviews. After participating in the interview, the children were given small incentives (20 EUR gift cards for the refugees and school supplies for the domicile children). During all the interviews with the refugees, Arabic-speaking interpreters were available if participants opted for an interview in their mother tongue or needed help with expressing themselves in Croatian. To avoid focusing explicitly on a single refugee child during FGDs, teachers who had experience with different refugee children were included in the same group. An identical procedure was employed for the host-society children. With the participants’ permission, the conversations were audio-recorded. In one FGD with teachers, participants did not consent to the recording and therefore detailed notes were taken instead.

Analysis

Verbatim transcripts of FGDs and interviews were anonymized and imported into the NVivo 12 software (QSR International, Citation2018). A coding scheme was developed using an inductive, data-driven approach (Boyatzis, Citation1998). First, we performed “open coding” of a subsample of interviews and FGDs, comparing identified patterns across transcripts. Second, initial codes were developed to link the data to our research questions. These codes were categorized to describe either challenge (identified barriers and issues that hinder the process of school integration of refugee children) or suggestions (explicit propositions on what should be done to improve this process). To strengthen the reliability, the first two authors independently performed an initial coding of 29% of the transcripts from different subsamples, using an interview passage as a coding unit (Boyatzis, Citation1998). Inter-coder reliability was calculated using a “coding comparison” query, which yielded 99% agreement. Disagreements were collectively discussed and initial codes were further refined by the first four authors. Finally, the first two authors independently coded all the transcripts and thematic analysis (Boyatzis, Citation1998) was conducted. Identified 23 challenges and suggestions were combined into three themes that correspond to specific areas of refugee integration. These themes were then divided into subthemes to achieve a meaningful structure. Themes and subthemes were viewed as general and specific needs, which encompass everything necessary for successful school integration, but were deemed currently absent. For each specific need participants reported several challenges and offered various suggestions about how a given need might be approached (). Furthermore, a “matrix coding” query was run to examine the perspectives of refugee children, their parents, peers, and school staff.

Table 1. Overview of subsample characteristics.

Findings

Analysis revealed three themes related to the general needs in the process of integrating refugee children into schools: educational, language, and social needs. Each of them includes several specific needs, which further pertain to challenges in the integration process and suggestions for improving the integration of refugee children in schools (see Table B in Supplemental Materials).

Educational needs

This general need encompasses three specific needs: the need for preparation before the enrollment of refugee children into schools, the need for appropriate guidelines in the process of enrollment, and the need for organization of the teaching process.

Need for preparation before refugee children arrive at school

This issue emerged from challenges and suggestions reported by school staff, domicile children, and refugee parents. Specifically, school staff referred to their lack of skills for working with refugee children, reporting that the arrival of refugee children in their classrooms is usually sudden and that schools often lack sufficient information. Thus, teacher SS1Footnote3 states: “I felt enormously betrayed and left in the lurch because absolutely no one competent ever came and explained ‘this is how you approach a [refugee] child, you have these tools, these possibilities’.” Teachers often expressed the need for “basic information” about the refugee children (e.g. previous schooling or language skills) or specific information related to the children’s refugee status. The lack of information was also reported to contribute to insufficient preparation of domicile children for the arrival of their refugee peers, mentioned by both school staff and domicile pupils. When children are left unprepared or without an explanation for the arrival of a new refugee pupil, they construct their own stories, which can further impede the social integration of refugees. A nine-year-old domicile boy describes his misconceptions about the arrival of his refugee peer:

I found it weird because I also didn’t know why they had arrived. I thought he got a reprimand and had to change schools, that he was bad. And then I was afraid to approach him […]. And for a couple of months or weeks I stayed away from him, as far as I could. And then, when I noticed he didn’t have any friends and no one was hanging out with him, we started, he and I started playing together.

An additional challenge reported by school staff and refugee parents was that parents did not have (sufficient) information about the Croatian education system.

Participants offered various solutions to these challenges. Specifically, school staff suggested accessible and quality training, in which they could acquire knowledge about the cultures of origin of refugee children, teaching practices, and specific issues, such as dealing with the traumatic experiences of some children. Moreover, school staff, refugee parents, and domicile children suggested that refugee families undergo formal preparation before starting school to introduce them to the system. In the words of RP1, a refugee mother:

It is very important that [refugee children] have some sort of preparation about behavior, what everything is going to look like in the classroom, (…), how will others behave, how the teacher is going to teach and so on.

Need for appropriate guidelines in the enrollment process

Two challenges related to enrollment were reported: the unavailability of a (realistic) protocol for initial testing of refugees in schools and questions regarding the placement of a child into a specific grade according to his/her age or knowledge level. While the protocol is mostly relevant for school staff and refugee parents (adults), it affects all groups as decisions made at this time point have long-lasting consequences. On the other hand, all participant subgroups mention the challenge of class placement. Refugee children are often placed in classes with younger pupils to give them more time to catch up on the language skills and the curriculum. However, school staff, as well as refugee and host-society children all, report that this often poses a challenge for social integration. Therefore, a dilemma arises: refugees placed in a class with their own age group often have more difficulties with schoolwork, while those placed in classes with younger pupils have a harder time forming social bonds. In light of these challenges, school staff recommends that a detailed and realistic protocol for enrollment and inclusion of refugees in elementary school be prepared by the Ministry of Education. However, solutions regarding enrollment of refugee children in schools with more than one refugee child of the same age differed. While domicile children felt that refugees should all be enrolled in the same class to support each other, school staff and refugee children had divided opinions, pointing out that splitting children into different classes could be more beneficial for their language skills.

Need for organization of the teaching process

Six different challenges related to the teaching process were reported. School staff and domicile children agreed that teaching refugees requires a lot more time and effort, especially considering the requirements of the official curriculum. This is certainly demanding from the perspective of refugee children as well, as illustrated by the statement from a ten-year-old refugee boy, RC1: “It is very difficult because sometimes we only have two weeks to learn five different subjects and this is hard. Last week, we received 44 questions to learn in two days.” This challenge is closely related to the teacher’s dilemmas regarding how to grade pupils who are not fluent in the Croatian language, as SS2 explained:

This is really a huge problem, what should we grade? We should not adapt [individualize the materials too much] because they are able [to follow the regular program], but we do not know how to grade them when they do not understand us.

Furthermore, school staff also recognize gaps in knowledge among refugee children that are not related to language: “And there were problems with Math too […] not only verbal tasks. There are many omissions, many gaps. And we all know what that means in Math, there is no continuity.” (SS3)

All subgroups mentioned a perceived lack of motivation and a negative attitude towards school among refugee children. This notion is reflected in the words of teacher SS4: “…but I have a feeling that she sometimes likes to say she doesn’t understand, even if she does. I don’t know why, maybe she seeks attention, or she’s lazy.” While this observation was noted by most school staff and a large number of host-society children, only a few of them believed that the real issue was not a primarily motivational one, but rather arose because refugee children could not understand what was going on in the classroom and hence became bored and unmotivated. Instead, most attributed this perceived lack of effort internally and therefore blamed the children for not trying harder. Combined with the fact that teachers perceived working with refugees as more demanding and felt let down by the school system, this sometimes led to burnout. Teacher SS5 describes her experience:

In the beginning, I gave all I could, I was killing myself over it, but, I mean, I have another 4 [pupils with] individualized educational programs in that class. And when I noticed that he’s fooling around a bit (…) and not putting in the effort, I had a feeling… In the beginning I tried so much, during teaching hours [the whole class] studied [counting] to ten in his language, to show them how difficult that is (…). And it lasted for, like, a couple of months, and around February, I slowly, I just gave up. I saw that it didn’t matter.

In contrast, refugee children and their parents perceived that children’s negative attitudes towards school were related either to their inability to understand what was being said in class, a dislike towards certain teachers, or, in rare cases, teasing by peers. Similarly, there was a view among school staff that parents were not sufficiently involved in the education of their children, sometimes ascribing this perceived lack of interest to cultural differences. This is mentioned by a school pedagogue, SS6:

Well, it’s different, say, the teachers noticed that parents at home don’t get involved in the education of the children that we have [in our school]. One parent, [refugee child’s name]’s dad, he is involved. And these [others] aren’t. They have more children, they don't work, but [school] is not that important to them.

While refugee children report that their parents rarely visit the school, they perceive it is mostly because of other duties they have at work and home. As one mother, RP2, explained: “the problem is that my time [is limited] and [along with current obligations, such as the] course and children and work, I can’t manage it all.”

School staff, refugee children, and domicile children all suggest more support for studying outside of class, either in the form of individual help or organized group tutoring. The refugee and domicile children also suggested additional individualization during class. A fifteen-year-old refugee boy, RC2 mentions: “Other teachers should give more information, make it easier for [refugee children], give them simplified school materials, information and so on”. Additionally, school staff with more experience with refugees suggested that the schools should have a “refugee children coordinator” whose job would be to take care of all issues regarding their education. Domicile children also suggested offering material help and implementing concrete changes in schools, such as culturally appropriate school meals.

To sum up the theme of educational needs, while four subgroups of participants mentioned similar challenges and suggestions, their views sometimes differed. Aside from the aforementioned disagreements on perceived reasons for the refugee children’s lack of motivation in school and their parent’s involvement in school, different actors provide more in-depth insights into different aspects of educational needs. For example, teachers predominantly talked about issues related to academic (un)success and difficulties in organizing classes for their refugee pupils. Adult participants focused on the lack of information during the whole school integration process, from enrollment to everyday class functioning, and refugee children talked more about their need for help with schoolwork. Domicile and refugee children tend to mention similar challenges and suggestions. Domicile children emphasized the lack of preparation activities to help them in welcoming a refugee child into the class.

Language needs

Two specific needs regarding the efficient acquisition of language and language fluency arose.

Need for fluency in the Croatian language

This need emerged from reported challenges created by the language barrier. The lack of proficiency in the Croatian language makes enrollment procedures more complex and dependent on the help of interpreters. Once children are enrolled in school, language continues to be an obstacle for teaching and learning, as well as in forming friendships with host-society peers. Fourteen-year-old domicile girl, DC4, explains:

Well, I think that, if they spoke Croatian, at least, like, some basic things, that we would’ve gotten along better (…) that way they could talk more about themselves. For example, what it was like in the other country, (…) do they have some problems at home. (…) And this way, we couldn’t do anything, because [Google] Translator doesn’t work well.

Furthermore, parents’ involvement in their children’s education is also limited due to their limited knowledge of the language. This is reflected in the words of RP2, a refugee mother: “Here, in a foreign country, we [the parents] don’t have a role [in our children’s education], because—the main reason is the language”.

To help reduce the language barrier, school staff, refugee and host-society children recommended using interpreters, who would help during class time and could facilitate communication between parents and the school. For example, RC3, a nine-year-old refugee girl says: “I would bring them a teacher who would help them every time they don’t understand something, and I would bring a teacher who speaks Arabic, to translate for them”. In light of the current shortage of Arabic interpreters in Croatia, we emphasize the suggestion from both children and teachers that even Croatian-speaking teaching assistants could be of great help. This person could be focused solely on a refugee child and be ready to help with the language and school work during and after class. Another suggestion mentioned predominantly by school teachers and host-society children was the adaptation of school materials for children not fluent in Croatian. A twelve-year-old domicile girl, DC5, shares her idea on how these materials might be structured:

I agree [that refugee children should have adapted textbooks] since we have tasks written in German, but translated into Croatian underneath that [in our German class]. So, [they have tasks in] Croatian, and underneath that an Arabic translation.

Need for efficient acquisition of Croatian language among refugee children

The most prominent challenge concerns the insufficient number of hours dedicated to language learning. According to regulations, refugee children have a right to 70 h of Croatian as a second language (CSL) instruction and another 70 h if needed, which is far from enough to be able to understand regular classes. Additional challenges pertain to various organizational aspects of CSL classes, such as long waiting periods for enrollment or organization of classes far from the child's home. However, the main issue reported by teachers was that CSL sometimes interfered with the schedule of the regular school program, which meant that refugee children missed certain portions of the curriculum. In some cases, teachers noted that school achievement deteriorated while attending CSL classes, as described by teacher SS5:

Last year, when he had those Croatian lessons, he did not come to class. And he was even more lost then. So, I didn't see that it helped him [even] a bit, but it hindered him because to some extent, while he was present in class and as we all tried our best [to help], there was some progress. And when he went to that Croatian course, he didn't come to school at all that day. And that's where the breakdown of the system actually began.

Therefore, all subgroups of participants suggested more intensive CSL classes organized for refugee children. However, while refugee children and some teachers suggested that children should learn Croatian before commencing regular school, other teachers highlighted the benefits of early inclusion for the development of language skills. Teachers also offered an alternative strategy to promote language learning where refugee children attend additional CSL classes instead of other school subjects that are heavily dependent on language (e.g. History). Finally, one refugee child suggested that CSL should be organized using a ‘learn-through-play’ strategy.

Overall, language needs showcase both the importance of learning Croatian for successful integration and the lack of the country’s experience with teaching Croatian as a second language. All participants view this general need as most important, but different actors offer different solutions. School staff and refugee children agree that bridging the language barrier should include additional CSL classes and the immediate help of teaching assistants. Domicile children predominantly mention immediate help, while refugee parents focus more on CSL classes. The parent’s attitude is consistent with their view that understanding the language is necessary to assure the family’s successful integration.

Social needs

Two specific social needs arose: the need for positive intergroup contact and the need for the elimination of negative intergroup behaviors.

Need for positive intergroup contact

Participants from all subgroups mention that contact between the refugee and the host-society children is superficial and limited to the school context, a notion apparent in the words of DC6, a twelve-year-old domicile girl: “Well, it’s alright, but no one hangs out with him after school, actually. He just goes home with his brother. But when we’re in school, everything is normal, everyone hangs out with him.”

Second, school staff, as well as refugee and domicile children, indicated that refugees sometimes favor ingroup contact. This preference is usually perceived as a means through which refugee children support each other and communicate in their native language. As a potential strategy for promoting positive intergroup contact, participants suggested that friendships between refugees and host-society children should be encouraged by school teachers.

Need for elimination of negative intergroup contact

All groups reported negative behavior among host-society children towards their refugee peers, while host society groups also provided examples of negative behavior among refugees. Observed behaviors included teasing, verbal insults, refusing to hang out or share a workspace in school, and sometimes even physical fights. While the number of cases of negative intergroup contact mentioned in FGDs was small, both domicile and refugee children emphasized the importance of responding to this issue. For example, a ten-year-old refugee boy, RC1, said: “If I were a principal, I would do something so that Croatian children don't mock [refugee children], “and a ten-year-old domicile girl, DC7, stated:

Some [pupils] are treating [refugee child] badly, some don’t want to play with him. He asks if they want to play, and they say no. Some say yes, and some say no – I would change it, so that every pupil hangs out with [refugees].

Altogether, social needs reinstate the importance of positive intergroup contact experiences for the promotion of successful refugee integration. Even though some instances of negative behavior were mentioned, overall participants did not accentuate them. On the other hand, the lack of meaningful intergroup contacts is noticed by all the subgroups of participants and seems to present a greater issue when considering the social needs of refugee children.

Overall, the thematic analysis revealed three themes describing the general needs, each of them related to specific needs, challenges, and suggestions on how to improve the integration process of refugee children. Even though different subgroups face somewhat different challenges, they all recognize the educational, language, and social needs of refugee children during the integration process. While these needs describe different issues experienced in the integration of refugee children in elementary schools, they cannot be viewed as entirely separate. Indeed, the language barrier might be viewed as the major source of reported challenges, influencing all aspects of the integration process. This issue is perhaps best illustrated by quoting two teachers: “The largest barrier is the language barrier” (SS7) and “They are average children, it’s just about the language barrier” (SS8).

Discussion

This study aimed to explore the needs, challenges, and suggestions of various groups in the integration of refugee children into Croatian elementary schools. It has expanded on the previous literature in several ways. First, as a study conducted in a country with limited experience in refugee integration, the results might be used to guide future planning, procedures, and modifications in the educational systems of other smaller and less diverse (European) countries. Second, this study has attained a more comprehensive understanding of the issue by triangulating various sources of data obtained from refugee children, their parents, classmates, and school staff. In addition to serving as a form of validation and consolidation of findings, this procedure has also allowed us to compare the viewpoints of different subgroups and take their varying perceptions into account.

The thematic analysis suggests three different, albeit interwoven themes that describe the general needs in the process of school integration of refugee children: educational, language, and social needs. These general needs correspond to sociocultural outcomes of academic success, host-society language fluency, and friendship with host-society peers, as described by Schachner et al. (Citation2017) framework. Identifying the needs creates an opportunity for taking the necessary steps to answer them. In the same theoretical framework, the school presents an important acculturation condition, which encourages positive sociocultural outcomes primarily through mainstream acculturation orientation (Schachner et al., Citation2017). Specific needs identified in this research may guide specific adjustments in the school context.

Educational needs vary in different stages of the integration of refugee children into school. In the beginning, there is a need for adequate preparation of both host-society members and refugees. This preparatory stage promotes feelings of certainty and self-efficacy and thus is important for ensuring successful future adjustment to a new school (Hek, Citation2005b). Additionally, schools need appropriate guidelines for the enrollment of refugees, which would address issues related to language, lack of documents, and gaps in previous education. Once children are enrolled in a class, the teaching process should be organized to accommodate the specific challenges related to refugee education, such as the assessment of pupils who do not speak the host-language, gaps in knowledge, and the inappropriateness of the official curriculum. At this stage, teachers need strategies for motivating refugee children and including refugee parents in their children’s education, a difficult, but necessary process for ensuring successful integration (e.g. Hek & Sales, Citation2002; Nagasa, Citation2014; Şeker & Sirkeci, Citation2015). Language needs encompass specific needs for fluency in the host-language and efficient language learning. Both of these specific needs highlight the importance of language for numerous aspects of integration, from educational processes to intergroup relations and friendships (Tip et al., Citation2019). Finally, identified social needs are in line with intergroup contact literature (Allport, Citation1954; De Coninck et al., Citation2021; Graf & Paolini, Citation2016), accentuating the significance of the promotion of positive and the elimination of negative intergroup contact. Although ingroup friendships of refugee children serve as a form of social support and understanding (Bartlett et al., Citation2017; O’Toole Thommessen & Todd, Citation2018), especially during the early stages of inclusion (De Heer et al., Citation2016), intergroup friendships are important for social integration and developing a sense of belonging (Juvonen & Bell, Citation2018). Similarly, while participants did not report many cases of peer bullying, they emphasized the necessity of counteracting any negative intergroup behaviors. This is especially important when taking into consideration the potential detrimental effects of such behavior on the mental health of refugee children and their connection to the host community (Guo et al., Citation2019).

Our findings corroborated those obtained in countries with far larger numbers of refugees and more experience in migrant education, which has similarly demonstrated a lack of specific training for working with refugees and initial preparation of both teachers and refugee children (Nagasa, Citation2014; Nilsson & Axelsson, Citation2013; Svensson, Citation2019). Furthermore, the results highlight the utmost importance of language for both education and peer communication, a finding consistent with those from other studies (Aydin & Kaya, Citation2017; Hek, Citation2005b; Madziva & Thondhlana, Citation2017; Nagasa, Citation2014; Nakeyar et al., Citation2018; O’Toole Thommessen & Todd, Citation2018; Şeker & Sirkeci, Citation2015). As mentioned earlier, the language barrier is often perceived as “the main challenge”, which hinders social relations, influences education, and is a barrier to parental involvement in their children’s education. Previous research has also identified challenges related to the lack of intergroup contact and social relationships with host-community members (De Heer et al., Citation2016; Guo et al., Citation2019; Şeker & Sirkeci, Citation2015).

However, in this study, the findings suggest that some needs and challenges might be more pronounced in countries with smaller numbers of refugees and culturally less diverse classroom settings. For example, members of school staff emphasized challenges related to the lack of an official protocol for assessing refugee children during enrollment procedures, for making decisions regarding children’s placement, or for the evaluation and assessment processes. While some guidelines for the education of foreign-speaking children do exist, they are not fully applicable to refugee children, whose complex migration experiences sometimes include switching between multiple education systems or being out of school altogether for several years, and who often face other socio-economic difficulties. The efficient organization of CSL classes is another challenge that might be linked to the limited experience of the country’s educational system with foreign-speaking children, which makes the logistics of CSL classes more complex. In light of the current changes to migration routes, other countries might find these results and recommendations useful in preparing integration procedures.

Our results also support using an integrative approach for examining the integration process. By exploring this issue with various stakeholders simultaneously, this study revealed several differences in the perceptions of different participant groups. For example, while school staff perceived refugee children to be poorly motivated for school, refugee children themselves reported that their dislike for school stemmed from their difficulties with the language. Similarly, school staff perceived refugee parents to be uninvolved and uninterested in their children’s education, but both children and parents stated that this was not the case and instead emphasized issues related to the language barrier, work, and family obligations. Although different stakeholders have somewhat different needs and perspectives, there are also significant consistencies in their views, with three general and nearly all specific needs observed in all participant groups. This consistency across groups contributes to the overall reliability of the results.

Nevertheless, the present study has some limitations. Because refugees spoke Arabic as their first language, interviews were conducted with the assistance of interpreters. Thus, there is a possibility that the meaning of some statements was lost in translation. It is also important to consider the limited experience of host-society members with refugees. Most of our host-society participants have had experience with one particular refugee child, meaning that their views about refugees are determined by the compatibility of their personality traits and mutual interests. Furthermore, all interviewed refugees had been granted asylum at the time of the study, limiting the generalization of our results to other refugees with a similar status. Indeed, the specific needs and challenges faced by asylum-seeking refugees might be influenced by the uncertainty of their legal status in the host-country.

This study has implemented a needs-based approach, to give voice to different actors in the school integration process, allowing them to describe the challenges they face, and provide suggestions on how to improve the current state. In future research this perspective could be complemented by a strength-based approach (Hughes, Citation2014; Mohamed & Thomas, Citation2017), emphasizing resilience and positive adaptation. Similarly, different aspects of integration could be linked more closely with the psychological well-being of the refugee children, in line with the Schachner et al. (Citation2017) framework. It might be beneficial to include and compare the experiences of other relevant actors too, such as school principals, NGOs, and volunteers who support refugee children with schoolwork, as well as officials responsible for education. Furthermore, previous studies have demonstrated differences in understanding the integration process among key stakeholders in large urban areas and smaller towns in Croatia (Ajduković et al., Citation2019). Given the fact that this study was conducted in the capital of Croatia, where all institutions relevant to refugee integration are located, more research is needed to assess the perspectives of host-society and refugee stakeholders from smaller towns or rural areas with limited resources.

Recommendations

Based on the findings of this study, we offer a few recommendations for improving practices that could guide and facilitate refugee children’s school integration:

Preparatory procedures need to address the needs of different actors in the integration process

Officials might prepare basic information for refugees on the national education system, an overview of the school subjects, general school norms, and the rights and obligations of refugee parents and children. Additional child-friendly information might be prepared for refugee children.

Teachers and domicile children need to be informed in advance when a refugee child will join their class. School staff should be provided with training aimed at developing skills for working with children from other cultural and language backgrounds, providing information on how to include multicultural themes into teaching practices, and prepare domicile pupils and introduce a refugee child into the classroom. When teaching involves vulnerable groups, such as refugee children, teachers face a double task—to follow professional norms but also to build relationships with their refugee pupils and support them in the integration process (Hargreaves, Citation2001; Taggert, Citation2011). Their support might be especially important in contexts where there is only one refugee child in the classroom.

Government bodies need to provide clear guidelines about the enrolment and teaching of refugee children

Enrollment procedures need to be uniformed and equally applicable across schools. Guidelines should include precise procedures for the child’s arrival, determining the grade placement of a child, and securing the support of interpreters during the initial discussions with parents and children. Additionally, admission tests that do not rely heavily on language should be prepared, as well as more appropriate forms of host-language fluency tests.

Teachers also need to be informed about methods for adapting various aspects of the educational system to the specific needs of refugees. The adjustment of the grading system is especially important, to avoid demotivating refugee pupils from studying and creating stereotypes about refugees among domicile children. It is possible to adjust standard grading methods until children are sufficiently fluent and to provide more detailed, qualitative feedback, which could encourage their motivation instead (Pulfrey et al., Citation2011).

It is important to address these issues in official guidelines because otherwise, some teachers might not feel they are allowed to offer creative solutions.

Language classes need to be more thorough and better organized

We emphasize the need to invest additional effort in the organization of CSL classes. Clear and consistent communication between schools and officials is needed to ensure that the host-society language classes do not conflict with regular school hours and that they are organized in the schools in which the children are enrolled. Some alternative strategies to language class attendance might be introduced early in the child’s integration, where refugee children could attend some subjects with their host-society peers, but skip those that rely more on language and attend CSL instead. This approach might be especially effective with older pupils. Furthermore, instead of relying on a standard number of required language classes, focusing on the acquisition of a certain level of language knowledge might be more suitable. Alternative methods for bridging the language barrier, such as bilingual school materials or the availability of teaching assistants during and after class, also need to be provided.

Social integration of refugees into the new community and intergroup contact need to be encouraged systematically

Although school staff is typically more focused on educational issues, this study identified a great need for school interventions aimed at improving intergroup attitudes and bringing refugee and host-society children closer together.

Finally, we support the implementation of a whole-family approach to integration by offering language classes to refugee parents and including both refugee children and their parents in activities with host-society members (Deng & Marlowe, Citation2013; Şeker & Sirkeci, Citation2015). Although schools are primarily oriented towards children, an important aspect of children’s integration is a supporting system ready to reach out to parents and establish cooperation. As such, schools might partner with local communities or NGOs and organize activities in which refugees and host-society members could meet, communicate, and collaborate.

TQSE-2021-0250-File002.docx

Download MS Word (36.4 KB)Disclosure statement

We have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Antonija Vrdoljak

Antonija Vrdoljak is a Ph.D. student and research project assistant at the Department of Psychology, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Zagreb in Croatia. Her research interests are related to the field of social psychology, focusing on intergroup relations and refugee integration.

Nikolina Stanković

Nikolina Stanković is a research project assistant and Ph.D. candidate at the Department of Psychology, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Zagreb. She is working in the field of social psychology, interested in the topic of intergroup relations and refugee integration.

Dinka Čorkalo Biruški

Dinka Čorkalo Biruški, Ph.D., is a Professor of Social Psychology at the Department of Psychology, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Zagreb, Croatia. For the past 20 years, she has been studying processes of community social recovery after the war, especially in ethnically divided communities, majority-minority relations, and minority identity issues. In addition to the research and teaching engagement, she is also active in the field of public policy, especially in minority education issues.

Margareta Jelić

Margareta Jelić is an associate professor at the Department of Psychology, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Zagreb in Croatia where she teaches courses in social psychology with a focus on interpersonal relations, social influence, and group processes. Her research interests are centred on identity processes, interpersonal and intergroup relations. She has been involved in several projects dealing with majority-minority relations and identity issues.

Rachel Fasel

Rachel Fasel, Ph.D. in Social Psychology, is a post-doctoral researcher at the Institute of Psychology, University of Lausanne, Switzerland. Combining individual and contextual level perspectives, she is interested in how individuals cope and react when confronted with life course stressful events and transitions. Her work focuses on war victimization, economic precariousness experiences, discrimination, stress, and suffering at work, identity, diversity, and gender inequality.

Fabrizio Butera

Fabrizio Butera is a Professor of Social Psychology at the Institute of Psychology, University of Lausanne, Switzerland. His work is concerned with the mechanisms of social influence, and the cognitive, motivational, relational, and structural processes that produce or hinder individual and social change. He has been involved in projects dealing with cooperation and competition in educational systems, and social class inequalities at school in particular.

Notes

1 In the present article, we use the term refugee for both people under international protection and asylum seekers, as defined by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (Citation2011).

2 This regulation, officially known as “Regulation (EU) No 604/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 26 June 2013” is available at: https://bit.ly/2CWXZ51.

3 The ID number used to refer to each participant indicates their subgroup (RC: refugee child; RP: refugee parent; DC: domicile child; SS: school staff) and the order of their first appearance in the article (in this case: SS1). If more than one quote from a single participant occurs in the text, the same ID is used.

References

- Ager, A., & Strang, A. (2008). Understanding integration: A conceptual framework. Journal of Refugee Studies, 21(2), 166–191. https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/fen016

- Ajduković, D., Čorkalo Biruški, D., Gregurović, M., Matić Bojić, J., & Župarić-Iljić, D. (2019). Izazovi integracije izbjeglica u hrvatsko društvo: Stavovi građana i pripremljenost lokalnih zajednica. Ured za ljudska prava i prava nacionalnih manjina Vlade Republike Hrvatske.

- Allport, G. W. (1954). The nature of prejudice. Addison Wesley.

- Arends-Tóth, J., & van de Vijver, F. J. R. (2006). Issues in the conceptualization and assessment of acculturation. In M. H. Bornstein & L. R Cote (Eds.), Acculturation and parent-child relationships: Measurement and development (pp. 33–62). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

- Aydin, H., & Kaya, Y. (2017). The educational needs of and barriers faced by Syrian refugee students in Turkey: A qualitative case study. Intercultural Education, 28(5), 456–473. https://doi.org/10.1080/14675986.2017.1336373

- Bartlett, L., Mendenhall, M., & Ghaffar-Kucher, A. (2017). Culture in acculturation: Refugee youth’s schooling experiences in international schools in New York City. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 60, 109–119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2017.04.005

- Blanchet-Cohen, N., Denov, M., Fraser, S., & Bilotta, N. (2017). The nexus of war, resettlement, and education: War-affected youth’s perspectives and responses to the Quebec education system. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 60, 160–168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2017.04.016

- Boyatzis, R. E. (1998). Transforming qualitative information: Thematic analysis and code development. Sage Publications.

- Cameron, L., & Turner, R. N. (2016). Intergroup contact among children. In L. Vezzali, S. Stathi (Eds.), Intergroup contact theory: Recent developments and future directions (pp. 151–168). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315646510

- Čorkalo Biruški, D., Jelić, M., Pavin Ivanec, T., Pehar, L., Uzelac, E., Rebernjak, B., & Kapović, I. (2019). Obrazovanje nacionalnih manjina i međuetnički stavovi u četiri višeetničke zajednice u Hrvatskoj: Stanje, izazovi, perspektive. Friedrich Ebert Stiftung.

- Crul, M., Lelie, F., Biner, Ö., Bunar, N., Keskiner, E., Kokkali, I., Schneider, J., & Shuayb, M. (2019). How the different policies and school systems affect the inclusion of Syrian refugee children in Sweden, Germany, Greece, Lebanon and Turkey. Comparative Migration Studies, 7(1), 10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40878-018-0110-6

- Cun, A. (2020). Concerns and expectations: Burmese refugee parents’ perspectives on their children’s learning in American schools. Early Childhood Education Journal, 48(3), 263–272. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-019-00983-z

- De Coninck, D., Rodríguez-de-Dios, I., & d’ Haenens, L. (2021). The contact hypothesis during the European refugee crisis: Relating quality and quantity of (in)direct intergroup contact to attitudes towards refugees. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 24(6), 881–901. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430220929394

- De Heer, N., Due, C., Riggs, D. W., & Augoustinos, M. (2016). “It will be hard because I will have to learn lots of English”: Experiences of education for children newly arrived in Australia. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 29(3), 297–319. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2015.1023232

- Deng, S. A., & Marlowe, J. M. (2013). Refugee resettlement and parenting in a different context. Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies, 11(4), 416–430. https://doi.org/10.1080/15562948.2013.793441

- Denzin, N. K. (1978). Sociological methods: A sourcebook (2nd ed.). McGraw-Hill.

- European Commission. (2021). Common European asylum system. https://ec.europa.eu/home-affairs/what-we-do/policies/asylum_en

- Graf, S., & Paolini, S. (2016). Investigating positive and negative intergroup contact: Rectifying a long-standing positivity bias in the literature. In L. Vezzali & S. Stathi (Eds.), Intergroup contact theory: Recent developments and future directions (pp. 92–113). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315646510

- Guo, Y., Maitra, S., & Guo, S. (2019). “I belong to nowhere”: Syrian refugee children’s perspectives on school integration. Journal of Contemporary Issues in Education, 14(1), 89–105. https://doi.org/10.20355/jcie29362

- Hargreaves, A. (2001). Emotional geographies of teaching. Teachers College Record, 103 (6), 1056–1080. https://doi.org/10.1111/0161-4681.00142

- Hek, R. (2005a). The role of education in the settlement of young refugees in the UK: The experiences of young refugees. Practice, 17(3), 157–171. https://doi.org/10.1080/09503150500285115

- Hek, R. (2005b). The experiences and needs of refugee and asylum seeking children in the UK: A literature review. National evaluation of the children’s fund. University of Birmingham.

- Hek, R., & Sales, R. (2002). Supporting refugee and asylum seeking children: An examination of support structures in schools and the community. Haringey & Islington Education Departments.

- Hughes, G. (2014). Finding a voice through “‘The tree of life’: a strength-based approach to mental health for refugee children and families in schools”. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 19(1), 139–153. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359104513476719

- Juvonen, J., & Bell, A. N. (2018). Social integration of refugee youth in Europe: Lessons learned about interethnic relations in U.S. schools. Polish Psychological Bulletin, 49(1), 23–30. https://doi.org/10.24425/119468

- Kenny, E. (2007). The integration experience of Somali refugee youth in Ottawa, Canada: “Failure is not an option for us” [Master's thesis]. Carleton University. Retrieved from: https://curve.carleton.ca/57fef27b-f068-4f1a-9b10-e432dbb8822d

- Lunneblad, J. (2017). Integration of refugee children and their families in the Swedish preschool: Strategies, objectives and standards. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 25(3), 359–369. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350293X.2017.1308162

- Madziva, R., & Thondhlana, J. (2017). Provision of quality education in the context of Syrian refugee children in the UK: Opportunities and challenges. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education, 47(6), 942–961. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057925.2017.1375848

- Manen, M. V. (1997). Researching lived experience: Human science for an action sensitive pedagogy. Routledge.

- Mohamed, S., & Thomas, M. (2017). The mental health and psychological well-being of refugee children and young people: An exploration of risk, resilience and protective factors. Educational Psychology in Practice, 33(3), 249–263. https://doi.org/10.1080/02667363.2017.1300769

- Motti-Stefanidi, F., Berry, J., Chryssochoou, X., Sam, D. L., & Phinney, J. (2012). Positive immigrant youth adaptation in context: Developmental, acculturation, and social-psychological perspectives. In A. S. Masten, K. Liebkind, & D. J. Hernandez (Eds.), Realizing the potential of immigrant youth (pp. 117–158). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139094696.008

- Nagasa, K. (2014). Perspectives of elementary teachers on refugee parent-teacher relations and the education of their children. Journal of Educational Research and Innovation, 3(1), 1. https://digscholarship.unco.edu/jeri/vol3/iss1/1

- Nakeyar, C., Esses, V., & Reid, G. J. (2018). The psychosocial needs of refugee children and youth and best practices for filling these needs: A systematic review. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 23(2), 186–208. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359104517742188

- Nilsson, J., Axelsson, M. (2013). “Welcome to Sweden…”: Newly arrived students' experiences of pedagogical and social provision in introductory and regular classes. Intercultural Electronic Journal of Elementary Education, 6(1), 137–164.

- O’Toole Thommessen, S. A., & Todd, B. K. (2018). How do refugee children experience their new situation in England and Denmark? Implications for educational policy and practice. Children and Youth Services Review, 85, 228–238. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2017.12.025

- Parker, B. D. (2016). Iraqi refugee mothers’ perceptions of parental involvement and experiences within school systems [Master's thesis]. University of Tennessee. Retrieved from: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/4301/

- Pastoor, L. d W. (2015). The mediational role of schools in supporting psychosocial transitions among unaccompanied young refugees upon resettlement in Norway. International Journal of Educational Development, 41, 245–254. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2014.10.009

- Pulfrey, C., Buchs, C., & Butera, F. (2011). Why grades engender performance-avoidance goals: The mediating role of autonomous motivation. Journal of Educational Psychology, 103(3), 683–700. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0023911

- QSR International. (2018). NVivo qualitative data analysis software; Version 12.

- Rana, M., Qin, D. B., Bates, L., Luster, T., & Saltarelli, A. (2011). Factors related to educational resilience among Sudanese unaccompanied minors. Teachers College Record: The Voice of Scholarship in Education, 113(9), 2080–2114. https://doi.org/10.1177/016146811111300905

- Salem, H. (2022). Realities of school ‘integration’: Insights from Syrian refugee students in Jordan’s double-shift schools. Journal of Refugee Studies, 34(4), 4188–4206. https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/feaa116

- Schachner, M. K., Noack, P., Van de Vijver, F. J. R., & Eckstein, K. (2016). Cultural diversity climate and psychological adjustment at school-equality and inclusion versus cultural pluralism. Child Development, 87(4), 1175–1191. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12536

- Schachner, M. K., van de Vijver, F. J., & Noack, P. (2017). Contextual conditions for acculturation and adjustment of adolescent immigrants – integrating theory and findings. Online Readings in Psychology and Culture, 8(1). https://doi.org/10.9707/2307-0919.1142

- Şeker, B. D., & Sirkeci, I. (2015). Challenges for refugee children at school in eastern Turkey. Economics & Sociology, 8(4), 122–133. https://doi.org/10.14254/2071-789X.2015/8-4/9

- Šeneta, A. (2019). Pravo na obrazovanje djece izbjeglica integriranih u zagrebačku osnovnu školu [Unpublished master’s thesis]. Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Zagreb.

- Svensson, M. (2019). Compensating for conflicting policy goals: Dilemmas of teachers' work with asylum-seeking children in Sweden. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 63(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2017.1324900

- Taggert, G. (2011). Don't we care? The ethics and emotional labour of early years professionalism. Early Years, 31(1), 85–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/09575146.2010.536948

- Thijs, J., & Verkuyten, M. (2014). School ethnic diversity and students' interethnic relations. The British Journal of Educational Psychology, 84(Pt 1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12032

- Tip, L. K., Brown, R., Morrice, L., Collyer, M., & Easterbrook, M. J. (2019). Improving Refugee Well-Being With Better Language Skills and More Intergroup Contact. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 10(2), 144–151. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550617752062

- UN High Commissioner for Refugees (2011). The 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees and its 1967 Protocol. https://www.unhcr.org/about-us/background/4ec262df9/1951-convention-relating-status-refugees-its-1967-protocol.html