Abstract

We examine a Twitter attack against our phEmaterialist pedagogy during a UK-wide COVID-19 lockdown. We explore how trolls swarmed together in a collective mocking and ridiculing of images of colorful Play-doh genital models posted as part of a Master’s module we teach. The session explored “clitoral validity” as a feminist pedagogical concept to disrupt phallocentric sexuality education through the modeling of the vulva and clitoris. We focus on a sub-sample of the attack, tweets that explicitly refer to clitoral validity, vulvas, and penises. We develop an analytical frame of networked affect and affective homophily in combination with psychoanalytical concepts to map affective circuits of misogyny and hate. To conclude, we use this episode to shed light on what is at stake for scholars working in feminism and/or gender and sexuality studies using creative, participatory, and arts-based methods and we both trouble and reclaim a position of bad feminist researchers/pedagogues.

Introduction: phematerialism Play-doh pedagogy during the global pandemic

It was February 2021, and we were “Zoom teaching” together the Master Module “Gender, Sexuality and Education” during UK's third nation-wide lockdown. The session focused on feminist Relationships and Sex(uality) Education (RSE). It marked the start of a pedagogical move for students from discussing the theoretical foundations of gender, sexuality, and feminisms to doing activist pedagogies, and putting theories into feminist praxis.

In this Master’s module, we develop a PhEmaterialist framework, which brings together the feminist capacities and possibilities of post-human/new materialist theories and methodologies, enabling new ways of doing research and feminist pedagogy. One goal of PhEmaterialism is to transform the educational researcher into a researcher-pedagogue-activist, who aims to generate material changes beyond academic circuits of exchange (Ringrose et al., Citation2019; Strom et al., Citation2019). PhEmaterialist practice aims to put feminist academics in the public sphere as they negotiate becoming a “public intellectual” (Peters, Citation2015) doing “public pedagogy” and all the attendant risks and burdens that entail.

Our phEmaterialist approach to research, pedagogy, and activism means we work with key collaborators and stakeholders as research partners that then contribute to the teaching module. For a couple of years, we have had “School of Sexuality Education” (SSE) medical advisors taking part in this specific session, running part of the workshops they teach in secondary schools which use Play-doh to create genitals. In-person sessions of former years focused on creating vulvas and the lack of understanding of women’s sexual pleasure, prioritizing the building of the clitoris. Teaching focused on the lack of regard and understanding of women’s anatomy in Western hetero-patriarchal science and medicine (Ringrose et al., Citation2019; Russo, Citation2017) and the silencing of women’s sexual pleasure and desire in sexuality education (Allen, Citation2013). Modeling vulvas with Play-doh is a way of re-mattering and troubling normative discourses and imagery of which genitals count in RSE, using arts-based, participatory and activist pedagogies (Renold, Citation2018). RSE has focused on the penis in terms of protection (condoms), and managing penile expectations (pressures), particularly for girls (Allen, Citation2013) thus what we call the heteronormative phallocentric focus of sexuality education. Our practice of modeling vulvas highlights a discussion on the clitoris, absent from anatomical lessons focused on reproductive organs. This activity challenges the missing discourses of women’s sexual desire in RSE by creating a touchable presence where there has been a normative absence (Allen, Citation2013; Fine, Citation1988; Ringrose et al., Citation2019). How radical to focus on a bodily organ whose primary purpose is “feminine” sexual pleasure!

Indeed, the session was inspired by Patti Lather’s concept of “clitoral validity” (Citation1993), which called for anti-foundational non-complementary ways of countering male-dominated phallogocentric epistemologies (Braidotti, Citation2013) that ground humanist, rational, scientific domains of legitimate knowledge. We were seeking to re-matterialize and extend “clitoral validity”, since Lather used this term in an abstract sense to counter the male-dominated scientific epistemology of what is valid knowledge and social sciences research. Our aim was not only to counter the validity of the phallocentric curriculum of Sexuality Education but also to legitimize working and teaching with Play-doh clitorises and vulvas with MA Students as an affective pedagogical exercise that promotes learning by facilitating and making noticeable the presence of different and interlinked affective waves and bodily capabilities and senses (Barad, Citation2007; Ringrose et al., Citation2019; Citation2019; Strom et al.). Following Hickey-Moody (Citation2013), we consider these bodily responses as having a pedagogical impact and as embodied affective sources of knowledge. Using a child-like medium and play to address a serious academic topic also re-matters dominant ways of thinking/doing teaching and academia. Thus, we counter the normative one-way educational practice of Higher Education by trickling theoretical knowledge into students’ “minds”, through dynamical, embodied, material-affective processes of creating something that touches the topic (genitals, clitoris) (Ringrose et al., Citation2019).

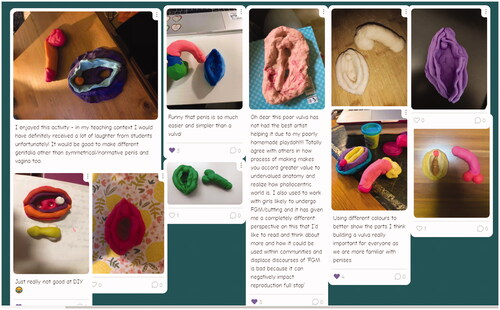

For the 2021 workshop, we had students dispersed around the globe, with diverse cultural contexts around what types of sex education would be offered in their country. The students also had different lockdown conditions, which meant, among others, that not all students could get Play-doh. Yet, convinced of the pedagogical power of matter even when facilitated through an online platform, we provided a recipe for DIY modeling dough and added an interactive activity at the end. This added activity asked MA students to upload pictures of their creations along with their experiences of genital building and reflections on sexuality education to the platform of Padlet, which is an interactive digital space that acts as a bulletin wall where people can share, like and post pictures and comments.

On February 9th, 2021 when we were to deliver the session, however, we were surprised that the SSE medical advisor running the workshop also included the modeling of the penis, which had not been the case in previous years and thus introduced something very different into the session. Students reflected that the presence of the penis could increase binary conceptions of genitality, instead of a full consideration of intersexuality and other aspects we were examining in the module. We later came to notice that the confection of colorful plasticine penises would eventually be perceived as childish, repulsive, and depraved, although none of these reactions took place during the activity. The pictures in the Padlet activity after the genital modeling can be seen in and presented us with a diversity of shapes and sizes, which opened several discussions, including personal sexuality education experiences growing up, genital diversity, heteronormativity, and the beauty industry’s pressures on eliminating pubic hair; as well as discussions on how these strategies could work with teenagers in RSE sessions in schools.

Figure 1. Screenshot of the Padlet done during this session with images and comments from students (with their consent).

Pleased with the way the session had worked out despite the constraints of online teaching, Jessica, as in former years with the in-person activity, posted some of the Padlet pictures (consented by the students) and a selfie on Instagram to document the session as seen in . Conscious of the virulence and hate circulating on Twitter, she took out the selfie and posted 4 out of 6 images on Twitter, writing “Fantastic Play-doh genital building session today in Gender, Sexuality, and Education …we discussed how building vulvas is a form of clitoral validity and a rupture of phallocentric Sex Ed”.

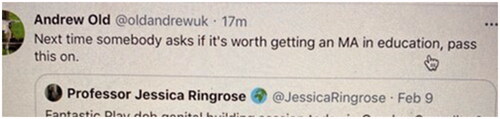

Within a couple of hours, the tweet was retweeted by @oldandrewuk (), a Twitter account with just under 20,000 followers linked to a British educational blog he runs dramatically entitled “Scenes from the Battleground Teaching in British Schools”. He posted the dismissive comment: “Next time somebody asks if it’s worth getting an MA in education, pass this on.”

Rapid negative comments followed this retweet, and so Jessica replied (), already interpreting that something was provoking hostility: “Some men are seriously threatened by play-doh vulvas! My Tweet has gone viral with Twitter trolls who think that women’s sexual empowerment does not belong in the classroom! Guess What? Your aggressive digs just make us feminists stronger! Please retweet if you agree!  ”

”

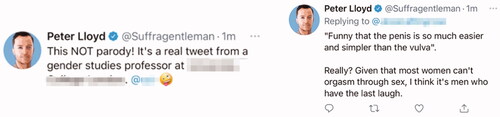

This tweet probably provoked more trolling since shortly after the attack escalated and the first Tweet was retweeted/commented upon by someone we later recognized as a misogynist, anti-feminist shitposter, Peter Lloyd @suffragentleman as seen in . This tweet presented Jessica’s account as a “parody” while calling his followers to mock her: “This is NOT a parody! It’s a real tweet from a gender studies professor (…)”. Shortly thereafter, Peter Lloyd did another tweet responding to one of our students’ comment about their experiences of building a penis (“Funny the penis is so much easier and simpler than the vulva”) saying “Really? Given that most women can’t orgasm through sex alone, I think it’s men who have the last laugh”. From here, the attacks sharply escalated. We contend that something alluring and “sticky” (Ahmed, Citation2004) in these colorful images of Play-doh genitals drove this man to click/tap, see and read each one of the students’ images and then mock them to retrench penile/phallic supremacy.

The combination of Andrew Old and Peter Lloyd’s retweets resulted in an attack upon Ringrose’s Twitter account that, according to Twitter analytics, created over 200,000 Twitter impressions (which is the times the tweets were viewed). Such a huge volume of attention was generated through a massive pile-up of negative comments that were experienced as a visceral embodied attack through the night as Jessica attempted to block abusive posters and report the worst of these openly misogynist tweets. The attack involved a wide range of tactics to shame and ridicule the teaching activity and Ringrose’s public Twitter identity, which we have previously theorized as networked gender-trolling (Xie et al., Citation2022).

In what follows, we focus on exploring the trolling tweets that refer to “clitoral validity” and genitals to shed light on the overlapping discursive-material-affective (Ringrose et al., Citation2019) layers of penile and phallic rebuttals against the shock of feminist research and activism around women’s sexual empowerment. For this analysis, we let ourselves dive in and out of the heterosexualized binary logic of the attacks and then show how the networked Twitter attack captured and re-signified the Play-doh genital models to mock and shame us as “bad academics”. We also use this episode to explore our PhEmaterialist researcher-pedagogue-activist relationalities and what is at stake in navigating a positionality of “public intellectual” (Peters, Citation2015) who challenges mainstream (hetero)normativity and phallocentrism of what is knowable and thinkable about gendered and sexual subjectivities.

Conceptual approach: networked affect, affective intensities, and phallic affective homophily

For our analysis, we hone in on the particularity of social media as connected, networked spaces (Jenkins et al., Citation2013); what media affect scholars call “affective publics” (Papacharissi, Citation2016) or spaces that generate “networked affect” (Hillis et al., Citation2015). As part of this media affect tradition, we understand affect starting from Deleuze and Guattari (Citation1987) notion of the capacity to affect and be affected, looking at how these forces operate in networked spaces through particular technological affordances (Papacharissi, Citation2016; Ringrose, Citation2011). Here, we look at how tweets operate in an affective economy of liking and retweeting that creates visibility, value, and “affective intensities” (Ringrose, Citation2011). Intensities can be fleeting or sustained—they can generate “affective events” on social media where the circulation and repetition of content can work by “pushing affected, networked bodies to sense things strongly in similar ways and by generating waves of affective uniformity resistant to ambivalence” (Sundén & Paasonen, Citation2020, p. 48). Networked affects, therefore, are not free-flowing; they are configured through power relations (Ringrose, Citation2018) and are intensely at work, producing and enhancing trolling swarms.

We explore the power and force relations of the affective circuits of the Twitter attack, aiming to show how the Play-doh genitals triggered affective responses in these networked spaces (Hillis et al., Citation2015). To understand how affective triggering to feminism works, we draw upon psychoanalytical work on collective forms of anti-feminist defensiveness within “the manosphere” (Allan, Citation2016; Crociani-Windland & Yates, Citation2020; Johanssen, Citation2022). The manosphere is a heterogeneous group of online communities with different ideological positions that congeal and unite or create “affective uniformity” around objects of ridicule, scorn, and hate mobilizing misogyny and expressions of masculine aggrieved entitlement (Ging, Citation2019). A psychoanalytically informed affective lens suggests that the popularization of feminism in the public domain triggers defensive anxieties over structural social changes, which disrupt male dominance in the family, employment market, and representational domains (Crociani-Windland & Yates, Citation2020). We suggest the global pandemic has exacerbated this perceived attack against tradition and masculinity since it has intensified already existing inequalities and anxieties linked with precarity and uncertainty, which can be defensively discharged as violent attempts to hold on to the status quo (Crociani-Windland & Yates, Citation2020). We will explore how “male victimhood” discourses (Banet-Weiser, Citation2021) are entangled with defensive affects of grievance, instead of grief (Crociani-Windland & Hoggett, Citation2012) which encourage and justify retaliation against the allegedly responsible for their loss: women and feminists. Given this circuit of shared grievance, the manosphere and trolling networks validate violence, abuse and online harassment (Salter, Citation2018) to collectively push back against elements that are blamed for their own denied vulnerabilities and anxieties (Crociani-Windland & Yates, Citation2020; Johanssen, Citation2022).

For this affective analysis, we also use Johanssen’s (Citation2022) psychoanalytic concept of “dis/inhibition” to explore the attacks as motivated by inhibitions awakened by our tweet, triggering a dis-inhibited response that “strikes back” and pushes away what is identified as “dangerous” (e.g. feminism and women’s embodiment and sexuality) to suppress the pulsing inhibition. This “pushing away” we contend is affective (Sundén & Paasonen, Citation2020) and is accomplished through shaming and ridiculing. Moreover, it functions collectively, and in a joined-up way that magnifies and intensifies the affects, via an online piling-up of aligning positions against objects of ridicule. We explore how the trolling mob is highly invested in hetero-patriarchal (Ging, Citation2019), conservative normativity which entails several—but not only—sexual inhibitions. Thus, we argue the trolling attacks are being compelled by defensive responses aiming at vindicating phallogocentric patriarchy, while also aiming to bring collective inhibited anxieties under control.

As we will argue, gender-trolling (Mantilla, Citation2013; Xie et al., Citation2022) is never an individual practice, but a networked, joined-up, more-than-human technologically mediated affectively intensifying pile-up of reactive and offensive posts that converge and target at high speed. Our analysis identifies tactics of irony, mocking, and humor that create a “connective laugh” through what Sundén and Paasonen (Citation2020) call “affective homophily”, the networked expressions of similar feelings that join people together. “Affective homophily” enables us to think of trolling as networked online practices that affectively bond humans and more-than-human together through connective online means and strategies, such as uses of keywords, hashtags, emojis, gifs, and images. We also consider this affective homophily as phallic (Allan, Citation2016), meaning that affects bind around desires for masculine domination against a common feminist threat. It is through mocking the non-conforming that a phallic order is reaffirmed and solidified as a normative reality in an apparently innocent way (Allan, Citation2016; Haslop & O’Rourke, Citation2021).

Methodology: analyzing heterosexualized defensive penile attacks

Our analysis focuses on a sub-sample of a wider sample of 180 trolling replies and quoted retweets we analyzed from the attack (Xie et al., Citation2022). This sub-sample is composed of 43 tweets that explicitly refer to clitoral validity, vulvas, and penises. We chose 17 tweets as exemplars to analyze in-depth here and demonstrate each point. We contend that despite our efforts to trouble heteronormativity, the involuntary introduction of the Play-doh penis introduced a dichotomy that may have favored the (hetero)sexualization of the models and undermined our counternormative objectives. So, when exploring the trolling tweets, we allow ourselves to get caught by the heterosexualized binary display of the attack to prompt us to think at the different layers and circuits that were at play in these penis-against-vulva, phallic-against-clitoral confrontations. We start analyzing the shock produced by “clitoral validity”, and then focus on the binary genital confrontation/competitivity. When possible, we present several tweets together to show their networked affective flows, intensities, and also repetition, a key feature of this particular networked phallic affective homophily that connected bodies, jokes, and laughs to shame and re-establish a phallic gender order.

Mocking the (inhibited) shock at “clitoral validity”

This first section addresses trolling tweets that refer mostly to “clitoral validity” to show the ways the concept was reworked and decontextualized to shame us. As noted, Patti Lather’s (Citation1993) “clitoral validity” is a concept that challenges the boundaries of normative, legitimate knowledge. For Lather, the name of the concept is meant to be “so excessive as to render the term unthinkable/unreadable” (Citation1993, p. 682). Thus, from its origins “clitoral validity” aimed at an affective impact, to shock and provoke, to point out the emergent but not yet thinkable possibilities for opening up beyond the limits of normative framings of “valid” research and knowledge, and to disrupt binary phallogocentric logic within academia (Lather, Citation1993); or create gender trouble (Butler, Citation1990). Attaching this provocative concept to the aesthetic impact of the images of colorful genitals in our tweet “caught” the eye of prominent anti-feminist trolls who tend to search out anti-heteronormative content (Ging & Siapera, Citation2019) or any explicit discussion of sexuality from feminist academics to target, shame, and to drive them off the network. We also show how the re-tweeting trail of our post continuously decontextualizes and relocates it into completely different meanings. What is common, however, is using shame and ridicule to re-direct our feminist pedagogy, challenging our affective force back to recuperate the masculine phallic order.

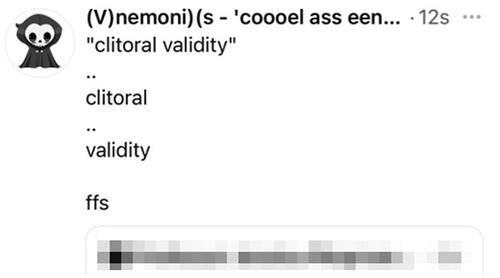

The tweet in expresses the surprise produced by the conjunction of both words. The separation of “clitoral” from “validity” shows the difficulty of thinking about the junction of anything valid and a clitoris. This could be because of misogyny, but also because of the difficulty to think of genitals or sexuality as a serious concern. Particularly in higher education, it seems to produce both cognitive dissonance and affective inhibition. The shock and the underlying inhibition are acknowledged in ffs (for f*ck’s sake), an expression of angry shock or frustrating confusion (Urban Dictionary, Citationn.d.-b). Yet, at the same time, this expression mocks and belittles the concept, as the dis/inhibited (Johanssen, Citation2022) insulting response that shuts down the chance to perceive their sexual inhibition, while this mocking retrenches the phallic order.

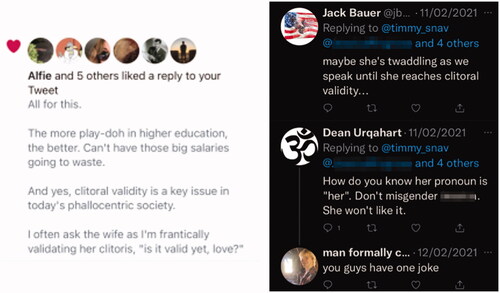

The tweets in show how irony facilitates being as offensive as possible while staying under the social media radar for hate detection. The tweet on the left starts ridiculing the use of Play-doh at universities, reproducing normative masculine-dominated standards for academia. It then criticizes academic elites for gaining “big salaries” for these activities. This mocking could be a defensive response to the (penis = money) envy that might produce the belief that people earn “big salaries” by doing pointless activities. We suggest this troll was triggered not only by feminism but also by the audacity of the (alleged elite) ones who have “big salaries” to “mock” the penis/phallus by portraying it in a powerless plasticine way. Then, in the second half of this tweet, the sarcasm continues by performing a fake agreement with “clitoral validity” and “phallocentric”. This works as the background for the punch line in which clitoral validity is transformed into an elaborated claim for orgasms from angry and sexually unsatisfied women, which is how several shitsposters referred to feminists.

Similarly, the tweet on the right in with “maybe she’s twaddling (...) until she reaches clitoral validity” suggests links between “reach(ing) clitoral validity” and reaching orgasm. Both tweets imply the only way women can be validated is through sex and orgasm, turning the activity into a sexualized and pornified joke about women masturbating. Perhaps this is the only way they can make sense of the retweets in the violence of Twitter “context collapse” where the tweet reaches an unintended audience (Marwick & Boyd, Citation2011).

Also relevant is how the tweets at the right in are all in response to a specific tweet from @timmy_snav, showing how the joke escalates and transforms, reaching other hate discourses as part of the networked affective homophily flow. In this case, from denigrating feminism and women, the joke moves to mock gender pronouns; which was a massive target of parody by the trolls. Accumulating likes, retweets and replies is a key affective dynamic in networked hate banter, where laughing while transgressing together works as bonding “affective homophily” (Sundén & Paasonen, Citation2020), visible and felt through the quantity and repetition enabled through the Twitter platform affordances. Replies, likes, and retweets can create a back and forth of in-humor jokes and wits in a competitive dynamic that provides different sensations of status for the posters to compete in being the most ingenious or funny (Kehily & Nayak, Citation1997; Whittle et al., Citation2019), but also have commonality, homophily and shared allegiance—recognized by “you guys have one joke”. The joking visibility builds and escalates through the Twitter functions of liking, retweeting, quote tweeting, building out as a rhizomatic networked assemblage of mockery and hate that affectively bonds them together against a common threat.

This last tweet in repeats the strategies of the tweets above, with the sarcastic and provocative use of concepts related to feminist research and identity politics (such as “clitoral validity”, “cultural appropriation”, and “phallus”) reaching other affective networked hate circuits, such as colonialism and anti-gender ideologies (Madrigal-Borloz, Citation2021). The Morph figure brings a nostalgic tone, referring to a past where times were “simpler” and better. This nostalgia shows the not only conservative but regressive forces of this tweet. The diversity and dynamism of society seem too complex and filled with “morons”, thus, this tweet expresses a desire to return to a never-existent past where they could be in control of a simpler reality, which resonates with alt-right fantasies (Johanssen, Citation2022).

This tweet mocks feminism by reasoning that clitoral validity demands living like Morphs, meaning penis-less. Validation of the clitoris triggers a massive defensive reaction and fear of emasculation. Anti-feminism tweets like these seek to discount feminist and gender politics through a performance of absurdity, which was also seen in the “grievance studies affair” where academic work was trolled by academics publishing “hoax papers” to expose and belittle academic work said to be biased and corrupted by activism and left ideologies like feminisms (Benner, Citation2018).

“Cock” and “cunt” to shame feminist arts-based pedagogy as bad academia

Considering that our activity aimed at challenging heteronormative and phallic-centered discourses on genitals and sexuality, it triggered several defensive responses. The surprise was frequently provoked by the affective shock of both “clitoral validity” and the colorful Play-doh genital models. Our phEmaterial re-mattering of genitals challenged the usual ways mainstream media portrays (and hides) the diversity of genitals, particularly vulvas. We noted puritan echoes associating sexuality with risk and shame in explicitly degrading tweets. Thus, mocking was not alone in producing affective homophily, there was also shaming and disgust. Some branded us mentally ill or impaired, while others called us perverts or vile. Other tweets expressed embodied reactions, such as it “makes me sick to my gut” among other reactions of rejection and disgust, including concerns about us sexualizing children “leave my grandkids alone you sick bastards” (Xie et al., Citation2022).

Here we explore specific tweets that use genitals to shame our academic work while defending a male-dominated understanding of “proper” academia and knowledge, attacking us for being feminists and researching-teaching about sexuality. We found that both “cock” and “cunt” words worked as pejorative references to genitals, and had an affective shaming force when they were used to portray our work as worthless. As seen in , some trolls used “cunt” to denigrate the vulva, women, and feminism, but also our hands-on pedagogical activity.

In , while bragging about his (alleged) academic achievements, this tweet opposes “theoretical physics”, which stands for proper academia, with “plasticine cunt”. Cunt here refers to something useless or without value, in contrast to his higher education degrees. Thus, this tweet, as well as a bunch of other tweets, ridicules us and defends normative masculinist understandings of knowledge, where not only hard science is better but also theory is at a higher standard than arts-based or any material-based work. Shaming bonds these tweets and posters together, while also pushing us away.

In the same shaming phallic affective homophily, other trolls linked “cock” with non-serious activities or youngster pranks, aiming at shaming us for our unworthy work, as seen in .

This tweet directly laughs, mocks, and pathologizes the activity by calling us “mental”. But this pathologizing refers not to sexual perversion, as we were frequently considered (Xie et al., 2022), but to “childish” behavior that must “Grow up”. The drawn “cock and balls on the back of the toilet door” as a youngster prank signal us as investing in pointless rebellious, akin to pornographic graffiti, or banter aimed at shocking people (Kehily & Nayak, 1997).

Associating our activity with a childhood that needs to “Grow up” is mocking at using Play-doh in teaching MA modules while reinstating normative ideas on higher education “seminars”. It implies that higher education is a waste of time infantilizing students, undermining the seriousness of making Play-doh genitals as an arts-based participatory feminist approach to sexuality education. The paradox here is that if young adults make Play-doh genitals at university, they need to grow up, but it would be considered inappropriate if children were doing the same at school, as the tweets that called us perverts made clear. So, any materializing of genitals in an educational forum is preposterous, and we can feel the defensive barrier clearly from “Hedge Fund”. Hence, we argue that Play-doh’s associations with childhood when put in material interface with sex education may also awaken sexual inhibitions that triggered these attacks.

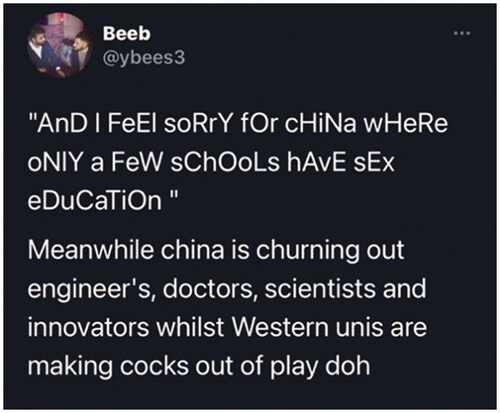

Finally, this hyperbolic tweet in refers to the collapse of Western Academia since “Western unis are making cocks out of play-doh”, in opposition to the uprising of China’s scientific development with “engineers, doctors, scientists”. According to the Urban Dictionary (Citationn.d.-a), using alternating capital letters express sarcasm and mockery, conveying the poster’s belief that it is a good thing that China lacks sex education. This shaming tweet opposes productive and scientific (assumingly masculine) professions which belong to hard sciences against our feminist sexuality education and arts-based pedagogy. By doing this, it is referring to the existence of “good” areas for research and innovation, and “bad” areas, such as sexuality education, but also social sciences, which are unscientific, not productive, and thus, not worthy to study.

The comparison of the West with China could associate with a concern about western world's phallic potency through technological progress. China’s (phallic) power is built on “churning out engineers, doctors, scientists, and innovators”, while the West has a Play-doh “cock”. Maybe the poster in feels that this kind of activity belittles the West against their orientalist perceptions of China. In addition, this concern implies that western people are victims of these stupid people in universities and schools that are concerned about sex education while there are more relevant capitalist and patriarchal pursuits, and thus this form of knowledge-doing is undermining the West as a whole. Tweets opposing the West and China were common, and they drew its affective force from portraying a false (orientalist/cold war) threat by amplifying the impact of our feminist “badness” endangering the whole Western Civilization. Hence, enabling the emergence of victimhood discourses and defensive affects of grievance; a typical antifeminist tactic that uses both sarcastic humor and fear to recuperate the power that is represented as under threat or lost (Banet-Weiser, Citation2021; Ging & Siapera, Citation2019). Finally, the mocking of teaching with Play-doh is in marked contrast to the development of “serious play” work using Lego, which fits with masculinity paradigms of building, engineering, and worthy forums for mental development (Dann, Citation2018).

Penises defending the phallic heterosexual order from feminist vulvas

Within heteronormativity gravitational pulls, many tweets underscored the difficulty of detaching genitalia from mainstream (hetero)pornography, men’s entertainment industries, and consumerist heteromasculinist discourses of sex. Within our pedagogical activity, we aimed to deconstruct and detach from phallocentrism but this move is then lost in the context-collapsed (Marwick & Boyd, Citation2011) multiverse of Twitter. Trolls were easily drawn into heterosexualizing the models as oppositional genitals or sex toys and mocking them to create a binary competition between vulvas and penises, to then reinstate penile superiority and thus the phallic order.

Worst. Dildos. Ever.

“Thanks but I’ll stick with Fleshlight.”

Through joking, irony, and laughter, these tweets heterosexualize the Play-doh genital models, opposing penis and vulva while reinforcing the dominant position of the penetrative erected penis. Both tweets refer to heteronormative sex toys for penetrative sex while showing the quick and “sticky” (Ahmed, Citation2004) heteronormative responses where vulvas are objects for the pleasure of men. On one side, the first tweet makes fun of the impotence of the plasticine penis. On the other side, Fleshlight is a penetration masturbator toy for penises and when comparing it to the Play-doh vulvas (“Thanks but I’ll stick with Fleshlight.”) it considers that plasticine vulva models are simply a poor reproduction of a sex toy meant to pleasure the penis.

Through laughter and banter, these tweets are trying to maintain the heterosexual, phallic order as incontestable truth and common sense (Allan, Citation2016). Yet also they try to keep the dominant role of the erected men/penis’s regarding sexuality. Even though- or precisely because- our post was all about everything except heteromale penises, trolling tweets turned the focus into the penis again: what the penis prefers to be stuck in, how they should be, or how they are just better. Affectively the trolls are triggered by the de-centering of the heterosexual penis and through their connected, “funny” tweet trails and laughs they aim to take back the (allegedly) lost space re-reading the penis as a heteronormative sex organ with penile sexual pleasure at the center.

As we saw in , Peter Lloyd @suffragentleman (an open dig at suffragettes and women’s rights) explicitly read and responded to a comment from one student in the Padlet that was felt as belittling penises as “easier and simpler” to make than vulvas, saying “Given that most women can’t orgasm through sex alone, I think it’s men who have the last laugh”. Lloyd understands sex as penile-vaginal penetrative sex, and male orgasm via this mode as evidence of penis superiority. Lloyd read the genitals as part of a heterosexual rivalry and tried to “bait” his followers into joining in with men “having the last laugh” through identification with this sentiment, which is then enacted via the rapid succession of retweets which connect, amplify and intensify this tweet.

As we saw earlier in , other tweets responded to the Play-doh genitals by calling up Morphs and mocking their lack of penises, as seen in .

The tweet in responds by re-mattering Morphs with a compensating ridiculously large neon green penis and testicles. This Twitterer displayed a special investment in phallic power badges in his Twitter username, “Sir_DixieNormous”, and profile picture with a crown. Symbols of phallic power are the royalty of the pointy crown and the “sir” title but also the direct references to an enormous penis (“DixieNormous”). Interestingly, the username @dick_splint points to the opposite of phallic and penile power since it signals devices for penises that could not have/hold an erection. The profile shows this user likely searches out particular penile material on Twitter for commentary, and phallic and penile potency is part of this person's quotidian concerns, and inhibitions around these issues were triggered by our PhEmaterialist Play-doh genital pedagogy.

(Offensive) vulvas turned into anti-feminist hateful insults

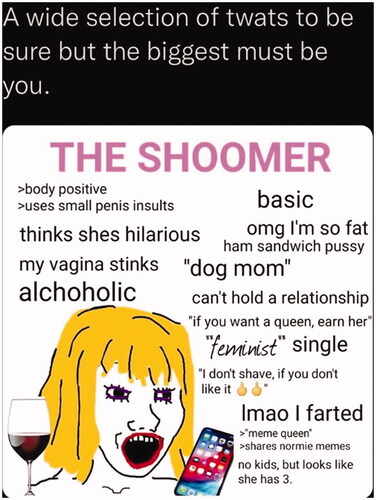

We suggest that the appearance of colorful vulvas on their Twitter feed offended some people who were affectively pushed by and through the networked chains of tweets, which generate a joint sense of entitlement and solidarity (affective homophily), to perform offensive tweets for their Twitter audience. Some trolls used “cunt” to denigrate the vulva, women, feminism, and our hands-on pedagogical activity, as in “You are a bunch of c**ts”. Trolls also provocatively used the vulva for anti-feminist, racist, or transphobic jokes, as we will see in . In this way, vulvas kept being framed as offensive and to be denigrated, and in extension, us too.

The tweet in refers to us as “twats”, both an insult and an offensive way to call the vulva (Urban Dictionary, Citationn.d.-d). The meme also offensively portrays feminist women according to anti-feminist manosphere logic and terms (Ging, Citation2017, Citation2019). “The shoomer” points out the alleged charade feminist women are doing since they are incredibly successful yet terrible at what they do (Urban Dictionary, Citationn.d.-c). “My vagina stinks”, “single”, “dog mom” (instead of real mom), and more; position feminists as disgusting and unable to secure a man, while making pornographic references to “ham sandwich pussy”. Further, these insults enhance several of the myths and “norm-shaming” around vulvas hygiene, looks, and shapes we aimed to contest with our feminist pedagogy.

In the tweets in , the vulva and clitoris were captured with provocative figures and hate speeches related to diversity that were not included in our tweet. This shows how both laughter and hate can work as affective homophily (Sundén & Paasonen, Citation2020) that bonds these attackers and invites for more hate-based mockery to enter in. We see an interaction based on the multicolor feature of some vulva models which caught the posters' attention, who, as the reply interprets, took it as an opportunity for expressing racism and mocking identity politics.

The same logic applies to the mocking of clitoral validity again in by conflating this term with discussions of gendered pronouns and transgender debates on genitalia. This tweet got caught by the clitoris, and transphobically relates genitals to identity to mock gendered non-conforming communities and identity politics. Again and again, we see how the connective flows move in and out of various forms of hate triggered by the material vulvas and the affective shock levied via the discourse of “clitoral validity”.

Conclusion: what’s at stake in being bad?

In this paper, we explored a trolling episode against our PhEmaterialist arts-based participatory and creative methods in teaching, where a networked trolling mob shamed us as “bad” feminist researchers. As we addressed in this analysis, many trolls could not perceive vulvas and penises as other than for sex (porn, sex toys) or related to gender identity politics, which they position as absurd. While the former triggers sexual inhibitions, the latter awakens inhibited anxieties related to uncertainty and the desire to hold to patriarchal categories and the conservative known (Crociani-Windland & Yates, Citation2020). Trolls turned the genital models with which we wanted to challenge phallogocentrism into absurd and shameful objects of disgust. We were framed as unwanted, unnecessary, or even damaging researchers along with gender studies, sexuality studies, and feminism.

This attack turned our feminist productions against us in ways that are almost impossible to contest for a range of different reasons. First, the number and speed of the trolling tweets piling up are experienced as an overwhelming affective mob. Second, the intertwinement of mocking, laughing, and violence enables trolls to banalize the violence of the attack and hit back calling you a “snowflake” (easily offended person) (Haslop et al., Citation2021) or a “feminist killjoy” that can’t take a joke (Ahmed & Bonis, Citation2012). Hence, and as we also experienced, challenging a troll only provokes more trolling. Third, Twitter’s platform and logic work as a striated space that maintains gender order and masculine dominance (Ringrose, Citation2011). Research shows (Mantilla, Citation2013; Marwick & Lewis, Citation2017) that there is no efficient technology to detect and prevent trolling attacks at the level of the affective intensity of a mob build-up, repetitive circulating homophilic attacks based on “humor” and in-jokes. The focus is on limited violent signifiers of sexual violence and proving threats (Burgess & Baym, Citation2020). Thus, the platform leaves the victims to the individualizing logic of reporting to defend themselves from thousands of attacks and figuring out how to classify the attacks with no category for misogyny, for instance (Twitter Help Center, Citationn.d.). Fourth, as above and referring to a wider context, there are no proper protocols in social media platforms nor a law against digital violence, or networked misogyny (which is yet to be defined as a hate crime) that can protect the victims from the intensity and volume of harassment of these attacks. Hence, the only way to cope with the ongoing attack is to close the account and stay away for a while. Just as the trolling intended to cancel the victim off the platform.

We propose, however, that it is crucial to consider trolling as violent, digital, networked, hate-based harassment and as collective acts of piling up aggressions. The use of banter and humor in trolling may facilitate the current underestimation of these aggressions since it makes each individual tweet “ambiguously” violent. Hence, when one considers each tweet on its own, is easy to frame it as “just a joke” and blame the target for feeling offended. Yet we show that laughing and mocking is an affective force with capacities to circulate shaming and hate on Twitter. Hence, we suggest it is the swarm that performs the violent affects of the attack and not a tweet on its own. Most of them alone were not scary direct threats, or seriously hurtful, which is what Twitter policies or the law will respond to. We even laughed with a couple of them because of their audacity, creativity, and drama. Thus, we see a need to change the logic from the “individual agency” of each troll profile (and “human” behind it) to the collective exponential and more-than-human agency and affective force that these piling-up attacks have. In this way, we could start sanctioning participation in these online practices as hate crimes.

As PhEmaterialist “public intellectuals” (Peters, Citation2015), we are putting our work in the public domain. In our case, both scholars and Ph.D. students are called upon by our institution to perform a digital public persona and to disseminate our work on social media (Ringrose, Citation2018). But there are few strategies to manage the risk or protect academics from the wide range of anti-feminist and misogynistic hostilities we risk when taking up positions of visibility (Banet-Weiser, Citation2018). Universities as institutions must start taking action against these digital politics of hate, beyond the scope of their “reputational damage” and risk to their brand, and protect their staff who put themselves on social media to contribute to the metrics and visibility of universities.

This paper contributes to raising awareness of the digital dynamics and risks of online misogyny (Jane, Citation2017). Responding to a debilitating Twitter attack that sought to shame us as “bad” (and much worse than bad) feminist researchers and teachers, we have mapped out the affective nuance of how the penetrative attacks mobilized, how they worked, and what was triggered. This exploration shows just how shocking, disruptive, and threatening feminist knowledge and re-matterings of the society are. We advocate continuing practising transgressive validity and “piercing lines of taboo” in the making of both pedagogic and research practices and theoretical (anti)foundations (Lather, Citation1993). We firmly stand in an ethico-onto-epistemology (Barad, Citation2007) position that merges ethics and epistemology, making us response-able to make our academic work count and make ripples in the “outside world”. But it also takes time, space and a supportive community to generate the affective distance required to refuse a shaming collective action or the possibility to turn speech intended to hurt into something affirmative (Mäkinen, Citation2016). That is to “stay with” the specific “gender trouble” unleashed (Butler, Citation1990; Haraway, Citation2016). The opportunity to write this paper has helped us create this distance, and reaffirm our commitment to being bad, shocking, and disruptive feminist researchers and pedagogues.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Bárbara Berger-Correa

Bárbara Berger-Correa (she/her) is a psychologist, sex educator and a PhD researcher at the Institute of Education, University College London. She works in the interstices of feminist posthumanist and psychoanalytic theories and her current research focuses on flirting, sexuality and feminist activism among teenagers in Chile.

Jessica Ringrose

Jessica Ringrose is Professor of Sociology of Gender and Education at IOE, UCL's Faculty of Education and Society, where she co-directs the UCL Centre for Sociology of Education and Equity. She also co-runs the AHRC funded research network ‘Postdigital Intimacies’ which works to reconceptualise the entanglement of online and offline and public and private experiences in the age of social media, and is co-founded another global network Phematerialism.org which brings together scholars, artists and practitioners interested in feminist posthumanism and new materialism in education.

Xumeng Xie

Xumeng Xie is a PhD candidate at the Institute of Education, University College London. Her doctoral research draws on digital ethnographic methods and feminist social theory to explore how Chinese young women understand, experience and learn about feminism and gender across offline and online spaces. Xumeng is particularly interested in the affective-discursive aspects of digital feminist practices and how social media has enabled new forms of connections, networks and activism.

Idil Cambazoglu

Idil Cambazoglu is a PhD candidate at the Institute of Education, University College London researching topics around online/offline boys, men and masculinities, youth cultures, and (social) networks and networking. Her doctoral research examines elite-school boys' online/offline performances and cultures of masculinities and masculine materialities in Turkey through semistructured interviews and visual digital methods and methodologies. Idil has an MRes in Sociology with a specialization in gender, politics, and sexuality from EHESS Paris.

References

- Ahmed, S. (2004). Affective economies. Social Text, 22(2), 117–139. https://doi.org/10.1215/01642472-22-2_79-117

- Ahmed, S., & Bonis, O. (2012). Feminist Killjoys (and other willful subjects). Cahiers du Genre, 53(2), 77–98. https://doi.org/10.3917/cdge.053.0077

- Allan, J. A. (2016). Phallic affect, or why men’s rights activists have feelings. Men and Masculinities, 19(1), 22–41. https://doi.org/10.1177/1097184X15574338

- Allen, L. (2013). Girls’ portraits of desire: Picturing a missing discourse. Gender and Education, 25(3), 295–310. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540253.2012.752795

- Banet-Weiser, S. (2018). Empowered: Popular feminism and popular misogyny. Duke University Press.

- Banet-Weiser, S. (2021). Ruined’ lives: Mediated white male victimhood. European Journal of Cultural Studies, 24(1), 60–80. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367549420985840

- Barad, K. (2007). Meeting the universe halfway: Quantum physics and the entanglement of matter and meaning. Duke University Press.

- Benner, J. (2018, October 5). Researchers troll academic journals with ridiculous hoax papers, they still get published. The Josh Benner Blog. https://joshbenner.org/2018/10/04/researchers-troll-academic-journals-with-ridiculous-hoax-papers-they-still-get-published/

- Braidotti, R. (2013). The posthuman. Polity.

- Burgess, J., & Baym, N. (2020). Twitter: A biography. University Press.

- Butler, J. (1990). Gender trouble. Routledge.

- Crociani-Windland, L., & Hoggett, P. (2012). Politics and affect. Subjectivity, 5(2), 161–179. https://doi.org/10.1057/sub.2012.1

- Crociani-Windland, L., & Yates, C. (2020). Masculinity, affect and the search for certainty in an age of precarity. Free Associations: Psychoanalysis and Culture, Media, Groups, Politics, 78, 105–127. https://doi.org/10.1234/fa.v0i78.332

- Dann, S. (2018). Facilitating co-creation experience in the classroom with Lego Serious Play. Australasian Marketing Journal, 26(2), 121–131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ausmj.2018.05.013

- Deleuze, G., & Guattari, F. (1987/2004). A thousand plateaus: Capitalism and schizophrenia (Brian Massumi, Trans. and Foreword). Continuum.

- Fine, M. (1988). Sexuality, schooling, and adolescent females: The missing discourse of desire. Harvard Educational Review, 58(1), 29–54. https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.58.1.u0468k1v2n2n8242

- Ging, D., & Siapera, E. (Eds.). (2019). Gender hate online: Understanding the new anti-feminism. Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-96226-9

- Ging, D. (2017). Alphas, betas, and incels: Theorizing the masculinities of the manosphere. Men and Masculinities, 22(4), 638–657. https://doi.org/10.1177/1097184X17706401

- Ging, D. (2019). Bros v. Hos: Postfeminism, anti-feminism and the toxic turn in digital gender politics. In D. Ging & E. Siapera (Eds.), Gender hate online: Understanding the new anti-feminism. Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-96226-9_3

- Haraway, D. J. (2016). Staying with the trouble: Making kin in the Chthulucene. Duke University Press.

- Haslop, C., & O’Rourke, F. (2021). “I mean, in my opinion, I have it the worst, because I am white. I am male. I am heterosexual”: Questioning the inclusivity of reconfigured hegemonic masculinities in a UK student online culture. Information, Communication and Society, 24(8), 1108–1122. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2020.1792531

- Haslop, C., O’Rourke, F., & Southern, R. (2021). #NoSnowflakes: The toleration of harassment and an emergent gender-related digital divide, in a UK student online culture. Convergence, 27(5), 1418–1438. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354856521989270

- Hickey-Moody, A. (2013). Affect as method: Feelings, aesthetics and affective pedagogy. In R. Coleman & J. Ringrose (Eds.), Deleuze and research methodologies (pp. 79–95). Edinburgh University Press.

- Hillis, K., Paasonen, S., & Petit, M. (2015). Networked affect. MIT Press.

- Jane, E. J. (2017). Misogyny online: A short (and Brutish) history. Sage.

- Jenkins, H., Ford, S., & Green, J. (2013). Spreadable media: Creating value and meaning in a networked culture. New York University Press.

- Johanssen, J. (2022). Fantasy, online misogyny and the manosphere: Male bodies of dis/inhibition. Routledge.

- Kehily, M. J., & Nayak, A. (1997). ‘Lads and Laughter’: Humour and the production of heterosexual hierarchies. Gender and Education, 9(1), 69–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540259721466

- Lather, P. (1993). Fertile obsession: Validity after poststructuralism. The Sociological Quarterly, 34(4), 673–693. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1533-8525.1993.tb00112.x

- Madrigal-Borloz, V. (2021). Protection against violence and discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity. United Nations. https://undocs.org/A/76/152

- Mäkinen, K. (2016). Uneasy laughter: Encountering the anti-immigration debate. Qualitative Research, 16(5), 541–556. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794115598193

- Mantilla, K. (2013). Gendertrolling: Misogyny adapts to new media. Feminist Studies, 39(2), 563–570. https://doi.org/10.1353/fem.2013.0039

- Marwick, A. E., & Boyd, D. (2011). I tweet honestly, I tweet passionately: Twitter users, context collapse, and the imagined audience. New Media & Society, 13(1), 114–133. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444810365313

- Marwick, A. E., & Lewis, R. (2017). Media Manipulation and Disinformation Online, Data & Society Research Institute. Retrieved from https://datasociety.net/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/DataAndSociety_MediaManipulationAndDisinformationOnline-1.pdf

- Papacharissi, Z. (2016). Affective publics and structures of storytelling: Sentiment, events and mediality. Information, Communication & Society, 19(3), 307–324. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2015.1109697

- Peters, M. (2015). Interview with Michael Apple: The biography of a public intellectual. Open Review of Educational Research, 2(1), 105–117. https://doi.org/10.1080/23265507.2015.1010174

- Renold, E. (2018). ‘Feel what I feel’: Making da(r)ta with teen girls for creative activisms on how sexual violence matters. Journal of Gender Studies, 27(1), 37–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/09589236.2017.1296352

- Ringrose, J. (2011). Beyond discourse? Using Deleuze and Guattari’s schizoanalysis to explore affective assemblages, heterosexually striated space, and lines of flight online and at school. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 43(6), 598–618. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-5812.2009.00601.x

- Ringrose, J. (2018). Digital feminist pedagogy and post-truth misogyny. Teaching in Higher Education, 23(5), 647–656. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2018.1467162

- Ringrose, J., Warfield, K., & Zarabadi, S. (2019). Feminist posthumanisms, new materialisms and education. Routledge.

- Ringrose, J., Whitehead, S., Regehr, K., & Jenkinson, A. (2019). Play-Doh Vulvas and Felt Tip Dick Pics: Disrupting phallocentric matter(s) in sex education. Reconceptualizing Educational Research Methodology, 10(2–3), 259–291. https://doi.org/10.7577/rerm.3679

- Russo, N. (2017). The still-misunderstood shape of the Clitoris. The Atlantic. Retrieved from https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2017/03/3d-clitoris/518991/

- Salter, M. (2018). From geek masculinity to Gamergate: The technological rationality of online abuse. Crime, Media, Culture: An International Journal, 14(2), 247–264. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741659017690893

- Strom, K., Ringrose, J., Osgood, J., & Renold, E. (2019). Editorial: PhEmaterialism: Response-able research & pedagogy. Reconceptualizing Educational Research Methodology, 10(2–3):1–39. https://doi.org/10.7577/rerm.3649

- Sundén, J., & Paasonen, S. (2020). Who’s laughing now?: Feminist tactics in social media. MIT Press.

- Twitter Help Center (n.d.). Twitter’s policy on hateful conduct. Retrieved November 25, 2021, from https://help.twitter.com/en/rules-and-policies/hateful-conduct-policy

- Urban Dictionary (n.d.-a). ALtErNaTiNg CaPs. Retrieved March 14, 2022, from https://www.urbandictionary.com/define.php?term=aLtErNaTiNg%20CaPs

- Urban Dictionary (n.d.-b). For fuck’s sake. Retrieved October 20, 2021, from https://www.urbandictionary.com/define.php?term=For%20fucks%20sake

- Urban Dictionary (n.d.-c). Shoomer. Retrieved October 20, 2021, from https://www.urbandictionary.com/define.php?term=Shoomer

- Urban Dictionary (n.d.-d). Twat. Retrieved October 20, 2021, from https://www.urbandictionary.com/define.php?term=twat

- Whittle, J., Elder-Vass, D., & Lumsden, K. (2019). ‘There’s a Bit of Banter’: How male teenagers ‘do boy’ on social networking sites. In K. Lumsden & E. Harmer (Eds.), Online othering (pp. 165–186). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-12633-9_7

- Xie, X., Cambazoglu, I., Berger-Correa, B., & Ringrose, J. (2022). Anti-feminist misogynist shitposting: The challenge of feminist academics navigating toxic Twitter. In P. J. Burke, R. Gill, A. Kanai, & J. Coffey (Eds.), Gender in an era of post-truth populism. Bloomsbury Academic.