Abstract

Holistic and ecological approaches to mental health support have been identified by many as best-practice approaches for creating and sustaining well-being. Those who experience mental health challenges including, for example, Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD), often struggle to find adequate, sustainable and ongoing care from clinical settings, and recent research shows that additional strategies such as peer support programs, arts approaches, and holistic school-based collaboration work effectively. More generally, the mainstream population continues to suffer from outdated, overly medicalised and frequently inaccurate notions of the experience of poor mental health and the effective support of those who suffer, and peer- and school-integrated approaches go some way toward better education about mental ill-health. This article uses a creative ecologies model (Harris, Citation2016) to help schools implement student- and family-led support programs for students experiencing mental health challenges in school settings.

Keywords:

Introduction

Following the many impacts on mental health and well-being resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic, those in education settings (primary, secondary and tertiary) have been called on to manage and address the added challenges of poor mental health bring their students (Jones et al, Citation2022; Wang et al, Citation2020). In particular, Abdulah et al (Citation2021) have suggested the efficacy of using arts-based approaches in working with young people with increased mental ill-health as a result of their experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic. While the world works to make sense of the global shock, struggles, and irreversible losses by celebrating how much we have learned, how well we have “pivoted”, and how pandemic-related shifts have created innovations in educational experiences and delivery, we look to the ways in which poor mental health in educational settings is still not receiving the resourcing and strategic recalibration that it deserves. By drawing on a “creative ecologies” (Harris, Citation2016; Holman Jones & Harris, Citation2022) model that attends to the whole-of-school environment, rather than the individual, education environments and educators might better serve those struggling with poor mental health, as well as their peers, teachers, educators and families. The creative ecologies model addresses five key areas of intersecting consideration: people (including partnerships), place, policies, processes and products. The underlying evidence-based heuristic builds upon systems theory in fostering creativity and other intangible 21st-century skills in schools or workplaces.

Recent research reflects the growing body of evidence regarding the efficacy of creative arts approaches to supporting young people with poor mental health (Fortuna et al, Citation2020; García-Carrión et al, Citation2019; Jensen & Bonde, Citation2018; O”Reilly et al., Citation2018). One example of recent growth in this approach is in the understanding and treatment of Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD), with creative methods increasingly used by service providers, researchers, and peer groups alike (Chiang et al., Citation2019). Whether used in schools, group therapy contexts, individual counselling or peer support programs, creative methodsFootnote1 allow young people to express themselves in ways that talk-based modalities don't reach. Creative arts approaches can include a wide range of techniques typified by tactile, experiential and generative approaches including but not limited to: video, graphic novels/comics, games creation, drama, visual art, dance/movement, ceramics, installation, animation, hip hop or other musical forms (Harris Citation2017). Particularly for disorders such as BPD, where emotional overwhelm and dysregulation are central to the experience, creative art outlets and activities can remove the need to “explain” what the sufferer is experiencing in words, facilitating instead the sharing of moods, impressions, or other non-literal and non-linear (or outcomes-based) representations of experience (American Art Therapy Association, Citation2022). These kinds of activities and outputs also allow for the exploration of sensory, affective and symbolic management of difficult emotions which can either be shared with others or kept private (Bakare, Citation2009; McNiff, Citation2004). Additionally, creative arts can provide a context and forum for trying out and rehearsing different responses to situations and stimuli, enabling youth to shift and change not only themselves but also their relationships and their environments (Casson Citation2004; Morris, Citation2018).

Borderline personality disorder

During the last twenty years, Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD) has gained more attention and acceptance as a psychiatric diagnosis which is not primarily treatable with medication, a factor that has historically reduced “legitimacy” of conditions in the medical community (Chanen, Citation2015). To be diagnosed with BPD one must meet 5 of the 9 criteria (as defined by the DSM-V and ICD-10) by demonstrating a pervasive pattern of interpersonal instability, self-harm, chronic emptiness, emotional dysregulation, fear of abandonment, dissociative behaviours, identity disturbance and suicidality (Kreisman & Straus Citation2010, p. 19; Lieb et al., Citation2004). However, more recent developments in the research on BPD are showing that criteria like “self-harm” have been historically understood in gendered ways (cutting, in female-identified people, for example, is less common in male-identified people with BPD), while now expanding into more diverse expressions (such as reckless driving, and other kinds of self-endangering behaviours that often present differently in males, etc).

The causes of BPD are not fully understood but are speculated to result from the complex interplay of an individual”s genetic and life circumstances (Kreisman & Straus, Citation2010; Lieb et al., Citation2004). Being subject to adverse experiences in childhood such as sexual abuse and neglect often places individuals at higher risk of developing the disorder (Zanarini et al., Citation2010). The onset of BPD typically develops during adolescence and has been thought to occur predominantly in women, although this is now being challenged as definitions and gendered biases in diagnosis are coming more to light (Chanen, Citation2015; Widiger, Citation1998). Individuals with BPD often experience compounded forms of disadvantage such as: being exposed to highly traumatic environments at crucial developmental periods (Holm et al., Citation2009; Warne & McAndrew Citation2007), experiencing comorbidity with other physical and mental illnesses (Wlodarczyk et al, Citation2018), being subject to incarceration (Lovell & Hardy Citation2014; Shepherd et al., Citation2017), and having decreased social support (Beeney et al., Citation2018).

BPD involves severe psychological suffering, with 10% of those diagnosed with a personality disorder committing suicide by the age of thirty (Grenyer et al. Citation2017; Paris, Citation2006).Footnote2 Results of the largest Australian BPD survey revealed 100% of 99 respondents self-reported experiencing suicidal ideation, with a further 98.9% claiming they had actively self-harmed (Lawn & McMahon, Citation2015, p. 516). Those diagnosed with BPD are more likely to experience poor physical health, due to a lack of basic screening for physical ailments, the impact of long-term pharmacological treatments, and due to high rates of smoking (Castle, Citation2019, p. 553). A longitudinal study conducted in Victoria, Australia found young people 24 years old diagnosed with a personality disorder were more likely to smoke, have lower levels of education, receive welfare and experience depression or anxiety long-term (Moran et al. Citation2016).

However, recent research evidence has also challenged the historically entrenched notion that personality disorders are indicative of a poor prognosis (Agnew et al., Citation2016; Larivière et al., Citation2015; Shepherd et al., Citation2017). Longitudinal BPD studies have shown patients” symptoms can improve significantly throughout their lifetime (Gunderson et al., Citation2011; Stone, Citation2017; Zanarini et al., Citation2010). Qualitative BPD “recovery studies” drawing on the expertise of those with lived experience have demonstrated that BPD can involve a recovery journey or process characterised by hope, improvements in self-confidence and self-efficacy, as well the establishment of meaningful relationships over time (Katsakou et al., Citation2012; Kverme et al., Citation2019; Ng et al., Citation2019).

BPD research and the terminology problem

There are very few consumer-ledFootnote3 and co-designed BPD studies, as “user-involvement” research currently dominates the field. User-involvement is a term given to research that includes consumers in an “advisory” or other non-core role to the project. This is evidenced by the growing body of literature focusing on BPD consumer”s experiences of service provision and recovery (Donald et al., Citation2017a, Citation2017b, Citation2019; Katsakou et al., Citation2012; Kverme et al., Citation2019; Ng et al., Citation2016). In addition, several scholars have called for a rejection of the concept of recovery (in lieu of a refocus on management and sustainability) and questioned the use of qualitative research which draws heavily on patients” biographical narratives (Baik et al., Citation2019; Barr et al., Citation2022; Costa et al., Citation2012).

Narrative approaches often encourage individuals to “tell their story”; such “inward-focused” approaches are potentially problematic for those experiencing a destabilised sense of self and fraught relationships associated with BPD (Morgan et al., Citation2012). Additionally, participants who identify as having experienced poor mental health are frequently invited to tell stories involving recovery. These recovery narratives ask people to share the experience of recovering from a mental illness in a personalised, linear narrative which emphasises self-improvement and determination to “conquer the odds” (Costa et al., Citation2012, p. 15). Since the early 2000s there has been increased demand for recovery narratives to be used in education contexts, research, wellness and charity campaigns, and by activists themselves (Woods et al., Citation2020, p. 3). Those critical stories of recovery highlight the ways in which such “success” narratives further stigmatise those who are not able to achieve recovery as protagonists in “failure” stories which can exacerbate feelings of low self-worth.

Supporters of survivor-led research also argue some forms of mental health-related qualitative research can exploit consumers” stories by engaging in “patient porn” (Costa et al., Citation2012), especially for compelling education messaging and for research fundraising. Research that draws on lived experience data has therefore been critiqued as a practice which harvests the stories of a vulnerable population to advance their academic standing and position (Woods et al., Citation2020). Survivors have argued that the proliferation of these “good, effective or politically acceptable” narratives has resulted in limited and restricted ways of expressing diverse, unique and often resilience-dominated life experiences (ibid, p. 4; Dillon & Hornstein, Citation2013). However, creative arts approaches that use “outward-focused” techniques (including drama and dance as well as poetry and visual arts) and that invite stories of living with (rather than conquering) poor mental health have been shown to can strengthen participant”s identities, increase their ability to maintain relationships and seek effective care, and ultimately enhance the wellbeing of individuals with mental health diagnoses (Gregory Citation2018; Gwinner et al., Citation2015; Morgan et al., Citation2012; Williams et al., Citation2019). Such creative arts approaches adopt a holistic and ecological understanding of mental health and well-being that does not rely largely (or solely) on individuals telling personal stories of recovery and success achieved in isolation or against the odds. In what follows, we explore how we might use creative arts to build and sustain mental wellness for youth in schools using a creative ecologies approach (Harris, Citation2016).

Taking a creative ecologies approach to mental wellness in schools

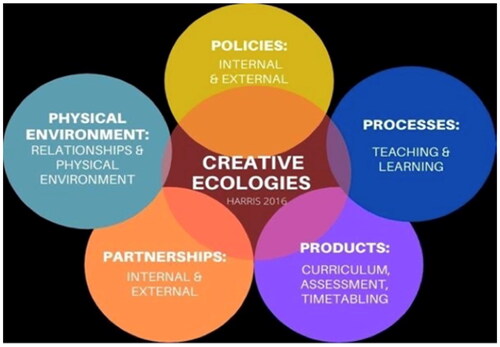

In Creativity and Education (Citation2016), Daniel (A.M.) Harris outlined a 5-pronged approach to fostering creativity in secondary schools. Since that time, the model (and accompanying whole-school audit) has been taken up in a range of educational and non-educational contexts. Here we outline some of the ways in which a creative ecologies approach might be adapted to support better mental health for and by young people in schools ().

Figure 1. Creative ecologies model (Harris Citation2016).

While people are always at the centre of any approach to increasing youth well-being, this model includes some of the most important more-than-human elements in the environment and community in which young people live and work in schools. By taking an ecological, or joined-up approach, students, their peers and their schools (and families, where possible) are able to drive their own wellness through an interconnected web of relationships and resources.

The creative ecologies model focuses on five interconnected domains that together impact the quality of any site or environment. It was developed for use in schools but has been successfully applied to university departments, organisations, curriculum hubs and more. The five domains are policies, processes, products, people/partnerships, and places (or physical environments). The creative ecologies approach foregrounds the need for interconnected and holistic approaches to goal-setting and achieving. It was developed to foster creativity in schools but can be applied to fostering well-being, literacy and other collective goals. Most importantly, the model involves the whole school community, including the more-than-human elements that are so often overlooked, but have significant impacts on the operation of the environment.

In this section, we will step through the heuristic using a composite character “Matthew”, a 16-year-old, male-identifying student in a public high school in Australia. This case study is based on long-form narrative interviews conducted in 2019 with 10 people who identify as living with BPD or as having a BPD diagnosis. The transcripts were double-coded for emergent themes, and the codes were compared and reduced in the second phase. Demographics, like almost all BPD studies historically show, reflected a majority of female teenage participants. As did the interviews, this case focuses on the experience of a male-identifying person in order to address the gendered nature of the diagnosisFootnote4 and the dearth of qualitative data on the experiences of males with BPD (Chugani, Citation2016; NHMRC Citation2012; Wirth-Cauchon, Citation2001). Arts-based research, or creative arts approaches in scholarly work, do not seek to offer finite solutions or “a positivist route that leads to a concretized outcome on a particular topic; rather, ABR, or art making, can present an audience with research findings and encourage its members to make their own interpretation of what they have experienced” (Salvatore Citation2017, p. 267). Thus, we have taken a “composite character” approach to presenting our findings of the ways in which creative approaches can be deployed in schools to assist students with BPD, especially during disruptions like the COVID-19 pandemic. In order to preserve the anonymity of the ten respondents in our interviews, composite characters are an accepted means of coalescing the emergent characteristics without risking identifying participants, a technique used widely in drama and theatre approaches to research (Salvatore, Citation2017). By synthesising the emergent themes and concerns of the 10 participants, this article shows how a school might go about using arts-based methods to address these common challenges in students with BPD.

BPD experience case study: composite character “Matthew”

Matthew has been struggling with emotional dysregulation and risk-taking behaviour for the past two years. Last year, Matthew was diagnosed with BPD and has been participating in a course of Dialectical Behaviour Therapy (DBT), which has shown some good results, but – like many of his peers – Matthew has experienced increased anxiety and depression throughout the isolation of multiple lockdowns and other disruptions during COVID-19. DBT is now the “gold standard” treatment for BPD, which combines aspects of Cognitive Behavioural Therapy with mindfulness practice. It was developed in the late 1970s by American psychiatrist Marsha Linehan, who herself suffered from BPD. Matthew is also taking an anti-anxiety medication which is helping to ameliorate mood swings. Matthew is about to start Year 10, and both his teachers and his parents are keen to come together to further support him and improve his school experience. Matthew and his parents meet with the principal and the Year 10 coordinator to work through a plan to support Matthew during the year. They draw on the creative ecologies model and whole-school audit to address the different areas of influence where Matthew might need support or ask for alternative structures and strategies to sustain his mental well-being.

The benefits of peer support and peer-led creative responses to living with BPD

Both creative approaches and peer support continue to gain visibility and “best practice” in the management of BPD and other mental disorders (Barr et al., Citation2022). In Australia, Project Air at the University of Wollongong provides world-leading research into the best practice treatment of personality disorders and complex mental health challenges. Their focus on education and education settings brings together clinical service providers and schools, the site where most young people with mental health challenges spend much of their lives (https://www.uow.edu.au/project-air/). The researchers at Project Air have been advocating since 2001 for governments to put a higher priority on personality disorders, especially BPD, which remains the most under-researched mental illness today. Their annual conference, (now in its 17th year) brings together consumers, loved ones, clinicians and researchers; the event contributes to the diverse body of evidence that suggests peer support and education is offering more sustainable, affordable ways forward. With waiting lists of up to two years to access DBT treatment programs in many cities, and even longer in remote areas, peer support is emerging as a powerful supplement to traditional options. The expansion of online treatment and “meet-ups” since COVID has also accelerated this form of support.

Online engagement has increased not only accessibility for many but also the uses of creative approaches and arts-based activities (Jewell et al., Citation2022) which can be conducted at home or at various locations. In one recent study, an online program of weekly art sessions with BPD consumers showed that peer facilitation using arts-based skills is appropriate, potentially effective, and enjoyable. As more people with lived experience of BPD come into the research and service provider communities, opportunities for more agentic peer collaboration and support will expand (Chilvers et al., Citation2021). Importantly, creative approaches—as well as attention to the entire ecology in which those with BPD live and work—allow proactive steps to be taken by the BPD (consumer) and decentralise care from clinicians who can be in short supply, and school staff who are similarly overloaded. As explored below, an ecological approach to peer support and peer-led created arts approaches is integral to the support the school environment can provide to Matthew and other youth living with BPD and other mental health challenges.

Peer support for family and friendship networks

Matthew”s parents have been participating in a program called Family Connections, a peer education and support program established in the United States by those who trained with DBT founder psychiatrist Marsha Linehan, and that is popular in Australia and New Zealand (Krawitz et al., Citation2016). Drawing on the DBT manual and skills written by Linehan (Citation2014), peer educators deliver a short course to Family Connections participants over 10 weeks, who then remain an informal peer support group after the course concludes. Participants who have been through the training then have the opportunity to become peer trainers through the program. An added benefit of the program is that participants come from many different perspectives and relationships with a loved one suffering from BPD; they might be parents, partners, children, friends or others. This means that in addition to the formal training, participants receive, they are also benefiting from hearing first-hand lived experiences from those in different relationships than their own in a peer support environment.

In this case, Matthew”s mother suggests to the principal that perhaps the Year 10 teachers (or all teachers at the school) might benefit from participation in a Family Connections program - perhaps adapted to schooling contexts – a kind of “School Connections” version. The principal is enthusiastic and agrees to meet with a representative of Family Connections and invite them to present at a staff meeting in the new year. By proceeding in this kind of collective, ecological manner, more ideas are sparked in the working through, an ongoing and iterative process that will continue to generate new ideas (Holman Jones & Harris, Citation2022). Based on this background and research insights, in the next section, we outline a creative ecologies approach that uses creative arts and peer support to enhance and sustain mental well-being for youth like Matthew who live with BPD.

Policies (internal and external): The principal works with Matthew and his parents to review the school policy on mental health, the support of the school counsellor (who works part-time), and the state policies regarding mental health and secondary students in their state. They find that in their state, Victoria, Australia, the state government offers a range of supports, including a “mental health and wellbeing toolkit”, links to external service providers, information that every government (public) secondary school in the state is now funded to employ a qualified Mental Health Practitioner, and an update that by 2026 all primary schools in the state will receive funding to implement whole-school programs for mental health and wellbeing (https://www2.education.vic.gov.au/pal/mental-health-schools/policy). These policies are a result of the 2021 Royal Commission into Victoria”s Mental Health System, with over $200 million in investment in these resources, programs and initiatives (https://www2.education.vic.gov.au/pal/mental-health-fund-menu/policy). Both Matthew and his parents are surprised to discover this level of investment, and it helps Matthew feel less self-conscious about asking for help. The principal reminds the family that these are general supports, but important ones and that the school will work with Matthew and his family to establish their tailored support plan that fits with Matthew”s needs and the school”s resources. This is in line with Victoria Health”s (VicHealth Citation2015) call to promote individual choice and collective responsibility for the health and well-being of all Victorians. A networked and ecological approach challenges the heavily stigmatised and individualised view of mental health challenges (Reupert et al., Citation2017). And in keeping with VicHealth”s long-standing policy and programming efforts to promote mental health and wellbeing through accessing the arts (VicHealth Citation2015), Matthew”s support plan will include robust creative art processes, products, partnerships and physical environments, as outlined below.

Processes (teaching and learning): Matthew is concerned about moving into the more academic demands of Year 10 classes, and he also sometimes finds it hard to start over with new teachers from year to year. Matthew suffers from feelings of overwhelm - both interpersonally and academically - which sometimes lead to angry outbursts toward his teachers or other students. As a result, Matthew has experienced panic attacks, sometimes slams doors or punches walls, walks off the school grounds without permission, or engages in self-harm. Difficulty regulating emotions is a core symptom of BPD, and it has the unwanted effect of alienating others, a pattern which Matthew and his support team are really trying to interrupt. The principal assures Matthew that he will have permission to excuse himself when he is starting to feel overwhelmed and will be allowed to work quietly in the library or other study areas, or in the counsellor”s office. DBT is structured around four core components: mindfulness practice, distress tolerance skills, emotion regulation skills, and interpersonal effectiveness, all of which Matthew has been learning in his group therapy treatment. For Matthew to be able to interrupt his ineffective patterns of feelings and behaviours, he needs both support and also the space to practise the skills. For example, when Matthew becomes overwhelmed and at risk of shouting or other angry outbursts in class, being able to quietly take himself outside, or to the counsellor”s office, and practise the distress tolerance skills, gives him a better chance of calming down and decreasing destructive behaviours. Both Matthew”s parents and the principal recognise the evidence-based research on BPD that advocates for sufferers” need to remove themselves from the situation, conduct their own distress tolerance skills, and have privacy to re-regulate their emotions before they are able to re-join activities with others (Jewell et al., Citation2022; Linehan, Citation2014). This kind of self-agency in monitoring the cycle of emotions is a powerful tool for those with BPD as it works to interrupt or avoid the socially alienating experience of reaching outbursts and their after-effects and consequences.

In addition to providing Matthew decision-making power over and privacy in his efforts to practise distress tolerance and self-regulation, Matthew and his parents ask that he be provided open access to the school”s art space and materials. This access will help Matthew more quickly and fluidly access mindfulness practice to help identify and regulate emotions and to reduce anxiety and maladaptive and harmful behaviours (Art Therapy Resources, Citation2022). Matthew is sceptical about the teachers” willingness to go along with such a plan and is unsure about his ability to use distress tolerance skills to catch his rising emotions early enough. The principal assures Matthew and his parents that they will meet with the Year 10 coordinator and his teachers before classes commence to write up the management plan. As a group, they decide that this is a good plan with Matthew in the driver”s seat, and the adults are able to reassure Matthew that even if it takes him some time to learn and practise his skills, it will most likely be an improvement on leaving things as they have been.

Products (curriculum, assessment, and timetabling): Matthew is a strong student who enjoys academic work, so he does not feel he needs any special consideration in the areas of curriculum and assessment. However, he does raise a concern about timetabling and the added academic stress of moving into Year 10 classes from the more informal Year 9 work that includes much more physical activity. After some discussion, the group put together a plan by which Matthew can have more regular breaks, go for solitary walks or “disengage” from the structured academic work at least 3 times throughout the day. He will not need to request or explain the reasons for these breaks, and the group is able to work out a proposal for his teachers that will cause the least disruption to the class.

In addition, Matthew”s plan includes school-supported and student-led creative movement (such as Open Floor and 5Rhythms Dance) and stress and emotional regulation activities (such as Yoga and mindfulness meditation) before and after school. Such programming is supported by research demonstrating the positive effects of user-led creative movement and meditation practices in supporting youth mental health and well-being (Cook & Ledger, Citation2004; Harden et al., Citation2015; Laird et al., Citation2021).

Partnerships (internal and external): The principal understands that it can be difficult for students to take themselves off to the counsellor”s office, and it can also impact peers” perceptions of Matthew, and/or his relationships with them. No one wants to feel “other” in a school environment, and sometimes the best self-care for BPD involves stepping away from groups which can be emotionally overwhelming. While Matthew, like many young people with BPD, is able to rely on his DBT therapist and the group he does the treatment with, sometimes this can let him down during his time at school. Schools are great at building partnerships for work with outside organisations, but the creative ecologies approach to mental wellbeing strongly suggests partnering with organisations that foreground both creativity and mental health services and activities.

Normalising these services and organisations within a school, a focus on mental wellness replaces a deficit-framed focus on mental ill-health (Baik et al., Citation2019; Caldwell et al., Citation2019). For example, Matthew participates in a local youth theatre group and they often create works addressing mental health in young people. Matthew suggests to the principal that if his theatre troupe was invited to perform for and talk with students and teachers in the school, he would be in a leadership role rather than an “outsider” role in helping his peers understand the BPD experience and the principal agrees. Matthew”s father takes the idea further, asking whether other students at the school might be invited into devising a performance on mental well-being for the whole school, thereby bringing a range of diverse students together on the shared project, including others who may be struggling with poor mental health, but not solely youth who are grappling with those “issues”. They also discuss the possibility of inviting state-based performing arts and mental health support organisations such as Visible Australia (https://visible.org.au) alongside youth and mental health providers like Beyond Blue (https://www.beyondblue.org.au) to run arts and mental health programs at the school.

Places (physical environment (and relationships): Matthew is seen as a student who is very self-motivated, and hard-working but is easily thrown off track by responses he feels are less than supportive. For many students like Matthew, being kept “on task” by well-meaning teachers can feel like invalidation and result in unwanted eruptions or even self-harm. Those who suffer from BPD have pronounced sensitivity to rejection and abandonment, and the perceived invalidation or even a slight dismissal can be experienced as severe rejection or failure. Matthew is able to complete his schoolwork most successfully and satisfactorily when he is allowed to go at his own pace and take breaks when he needs them. By attending to the physical environment and the relationships between Matthew and his teachers and peers, his support team can make space for a disorder in which relationships are often problematic and stressful, and because of this, potentially can be triggering. Matthew suggests that the school could establish more “chill out zones” throughout the premises, which could serve a range of purposes. He also asks for more arts materials in those spaces, to encourage self-expression in addition to distress management and emotional regulation. Access to art materials in non-art common spaces also creates opportunities to develop relationships with peers, drawing on evidence that suggests that engaging in non-directed and open-ended art-making helps youth develop creative skills that reinforce personal competence and connections (Moon, Citation2016; Rehman, Citation2020). By taking a strengths-based approach to Matthew”s need to express and sometimes regulate his emotions, all members of the school can share in growing their knowledge of BPD and the emotional diversities in their community.

Conclusion

As this brief creative ecology analysis suggests, there is much to be gained by taking a holistic and networked approach to address the urgent need to make schools places where poor mental health not only be ameliorated but also where mental well-being flourishes. Further, the ample evidence that shows the more we engage with the arts, the better our health outcomes and the important role that peer support and peer-led creative arts practice can have in magnifying these benefits, indicates that a creative arts ecological approach to mental health and wellbeing in schools has great promise. With the support of recent research and renewed government funding and policy initiatives (including arts initiatives) focusing on improving youth and mental health, educators and schools are well-placed to realise this promise.

Acknowledgement

The authors wish to acknowledge the research assistance of Ripley Stevens, whose background research into BPD aided in our development of the research argument presented in this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).e.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Daniel X. Harris

Professor Daniel Harris is an Australian Research Council Future Fellow, and Co-Director of Creative Agency research lab: www.creativeresearchhub.com. Harris is editor of the book series Creativity, Education and the Arts (Palgrave), and has authored over 100 articles/book chapters, 19 books, as well as plays, films and spoken word performances.

Stacy Holman Jones

Processor Stacy Holman Jones is the author and/or editor of more than 100 books, articles, chapters and editorials, including the Handbook of Autoethnography (2nd edition), co-edited by Tony Adams and Carolyn Ellis

Notes

1 Creative arts approaches share some methods and similarities with art therapy approaches, but do not in and of themselves constitute 'art therapy'.

2 Other studies with smaller samples suggest suicide rates could be closer to 4% (Kullgren, 1988; Zanarini et al. Citation2010).

3 In this article we use the term 'consumer' to identify those with a BPD diagnosis who are accessing treatment services, although the term remains contested in communities of lived experience and clinicians. Nevertheless, there is little consensus on what is preferable terminology, so for here use the term consumer while acknowledging its insufficiency. For those who identify as having BPD, or who have a diagnosis, but are not accessing medical treatment, we use the term 'survivors'.

4 Upwards of 75% of those diagnosed with BPD are female-identifying (NHMRC Citation2012), but more recent research has begun to indicate that there may be far more male-identifying consumers than previous thought, given expanded definitions of self-harm and other gendered expressions of BPD symptoms.

References

- Abdulah, D. M., Abdulla, B. M. O., & Liamputtong, P. (2021). Psychological response of children to home confinement during COVID-19: A qualitative arts-based research. The International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 67(6), 761–769. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764020972439

- Agnew, G., Shannon, C., Ryan, T., Storey, L., & McDonnell, C. (2016). Self and identity in women with symptoms of borderline personality: A qualitative study. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being, 11(1), 30490. https://doi.org/10.3402/qhw.v11.30490

- American Art Therapy Association. (2022). How art therapy works. https://arttherapy.org/about/

- Art Therapy Resources. (2022). Using art therapy to improve your emotional resilience. https://arttherapyresources.com.au/resilience/

- Baik, C., Larcombe, W., & Brooker, A. (2019). How universities can enhance student mental wellbeing: The student perspective. Higher Education Research & Development, 38(4), 674–687. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2019.1576596

- Bakare, M. O. (2009). Morbid and insight poetry: A glimpse at schizophrenia through the window of poetry. Journal of Creativity in Mental Health, 4(3), 217–224. https://doi.org/10.1080/15401380903192671

- Barr, K. R., Townsend, M. L., & Grenyer, B. F. (2022). Peer support for consumers with borderline personality disorder: A qualitative study. Advances in Mental Health, 20(1), 74–85. https://doi.org/10.1080/18387357.2021.1997097

- Beeney, J. E., Hallquist, M. N., Clifton, A. D., Lazarus, S. A., & Pilkonis, P. A. (2018). Social disadvantage and borderline personality disorder: A study of social networks. Personality Disorders, 9(1), 62–72. https://doi.org/10.1037/per0000234

- Caldwell, D. M., Davies, S. R., Hetrick, S. E., Palmer, J. C., Caro, P., López-López, J. A., Gunnell, D., Kidger, J., Thomas, J., French, C., Stockings, E., Campbell, R., & Welton, N. J. (2019). School-based interventions to prevent anxiety and depression in children and young people: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. The Lancet. Psychiatry, 6(12), 1011–1020. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30403-1

- Casson, J. (2004). Drama, psychotherapy and psychosis: Dramatherapy and psychodrama with people who hear voices. Routledge.

- Chanen, A. M. (2015). Borderline personality disorder in young people: Are we there yet? Journal of Clinical Psychology, 71(8), 778–791. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22205

- Castle, D. J. (2019). The complexities of the borderline patient: how much more complex when considering physical health? Australasian Psychiatry: Bulletin of Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists, 27(6), 552–555. https://doi.org/10.1177/1039856219848833

- Chiang, M., Reid-Varley, W. B., & Fan, X. (2019). Creative art therapy for mental illness. Psychiatry Research, 275, 129–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2019.03.025

- Chilvers, S., Chesterman, N., & Lim, A. (2021). “Life is easier now”: Lived experience research into mentalization-based art psychotherapy. International Journal of Art Therapy, 26(1-2), 17–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/17454832.2021.1889008

- Chugani, C. D. (2016). Recovered voices: Experiences of BPD. The Qualitative Report, 21(6), 1016–1034.

- Cook, S., & Ledger, K. (2004). A service user-led study promoting mental well-being for the general public, using 5 rhythms dance. International Journal of Mental Health Promotion, 6(4), 41–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623730.2004.9721943

- Costa, L., Voronka, J., Landry, D., Reid, J., Mcfarlane, B., Reville, D., & Church, K. (2012). “Recovering our stories”: A small act of resistance. Studies in Social Justice, 6(1), 85–101. https://doi.org/10.26522/ssj.v6i1.1070

- Donald, F., Duff, C., Broadbear, J., Rao, S., & Lawrence, K. (2017a). Consumer perspectives on personal recovery and borderline personality disorder. The Journal of Mental Health Training, Education and Practice, 12(6), 350–359. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMHTEP-09-2016-0043

- Donald, F., Duff, C., Lawrence, K., Broadbear, J., & Rao, S. (2017b). Clinician perspectives on recovery and borderline personality disorder. The Journal of Mental Health Training, Education and Practice, 12(3), 199–209. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMHTEP-09-2016-0044

- Donald, F., Lawrence, K. A., Broadbear, J. H., & Rao, S. (2019). An exploration of self-compassion and self-criticism in the context of personal recovery from borderline personality disorder. Australasian Psychiatry: Bulletin of Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists, 27(1), 56–59. https://doi.org/10.1177/1039856218797418

- Dillon, J., & Hornstein, G. A. (2013). Hearing voices peer support groups: A powerful alternative for people in distress. Psychosis, 5(3), 286–295. https://doi.org/10.1080/17522439.2013.843020

- Fortuna, K. L., Naslund, J. A., LaCroix, J. M., Bianco, C. L., Brooks, J. M., Zisman-Ilani, Y., Muralidharan, A., & Deegan, P. (2020). Digital peer support mental health interventions for people with a lived experience of a serious mental illness: Systematic review. JMIR Mental Health, 7(4), e16460. https://doi.org/10.2196/16460

- García-Carrión, R., Villarejo-Carballido, B., & Villardón-Gallego, L. (2019). Children and adolescents mental health: A systematic review of interaction-based interventions in schools and communities. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 918. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00918

- Gregory, F. (2018). Actresses and mental Illness: Histrionic heroines. Routledge.

- Grenyer, B. F., Ng, F. Y., Townsend, M. L., & Rao, S. (2017). Personality disorder: A mental health priority area. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 51(9), 872–875. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004867417717798

- Gunderson, J. G., Stout, R. L., McGlashan, T. H., Shea, T., Morey, L. C., Grilo, C. M., Zanarini, M. C., Yen, S., Markowitz, J. C., Sanislow, C., Ansell, E., Pinto, A., & Skodol, A. E. (2011). Ten-year course of borderline personality disorder: Psychopathology and function form the Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study. Archives of General Psychiatry, 68(8), 827–837. https://doi.org/10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.37

- Gwinner, K., Knox, M., & Brough, M. (2015). A contributing life”: Living a contributing life as “a person”, “an artist” and “an artist with a mental illness. Health Sociology Review, 24(3), 297–309. https://doi.org/10.1080/14461242.2015.1058176

- Harden, T., Kenemore, T., Mann, K., Edwards, M., List, C., & Martinson, K. J. (2015). The truth N” trauma project: Addressing community violence through a youth-led, trauma-informed and restorative framework. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 32(1), 65–79. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-014-0366-0

- Harris, A. (2016). Creativity and Education. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Harris, A. (2017). Creativity, Religion and Youth Cultures. Routledge.

- Harris, D. (2021). Creative agency. Palgrave.

- Holman Jones, S., & Harris, D. (2022). Against lists: A feminist ecological creativity. In M. Giardina & N.K. Denzin, eds., Transformative visions for qualitative inquiry. Routledge.

- Holm, A. L., Berg, A., Severinsson, E., & Högskolan, K, Sektionen för hälsa och samhälle. (2009). Longing for reconciliation: A challenge for women with borderline personality disorder. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 30(9), 560–568. https://doi.org/10.1080/01612840902838579

- Jensen, A., & Bonde, L. O. (2018). The use of arts interventions for mental health and wellbeing in health settings. Perspectives in Public Health, 138(4), 209–214. https://doi.org/10.1177/1757913918772602

- Jewell, M., Bailey, R. C., Curran, R. L., & Grenyer, B. F. (2022). Evaluation of a skills-based peer-led art therapy online-group for people with emotion dysregulation. Borderline Personality Disorder and Emotion Dysregulation, 9(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40479-022-00203-y

- Jones, S. E., Ethier, K. A., Hertz, M., DeGue, S., Le, V. D., Thornton, J., Lim, C., Dittus, P. J., & Geda, S. (2022). Mental health, suicidality, and connectedness among high school students during the COVID-19 pandemic – Adolescent behaviors and experiences survey, United States, January–June 2021. MMWR Supplements, 71(3), 16–21. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.su7103a3

- Katsakou, C., Marougka, S., Barnicot, K., Savill, M., White, H., Lockwood, K., & Priebe, S. (2012). Recovery in borderline personality disorder (BPD): A qualitative study of service users” perspectives. PLoS One. 7(5), e36517. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0036517

- Krawitz, R., Reeve, A., Hoffman, P., & Fruzzetti, A. (2016). Family Connections™ in New Zealand and Australia: An evidence-based Intervention for family members of people with borderline personality disorder. Journal of the New Zealand College of Clinical Psychologists, 2(25), 20–25.

- Kreisman, J. J., & Straus, H. (2010). I hate you ─ don”t leave me: Understanding the borderline personality, Penguin.

- Kverme, B., Natvik, E., Veseth, M. & Moltu, C. (2019). Moving toward connectedness: A qualitative study of recovery processes for people with borderline personality disorder. Frontiers in Psychology, 10(430), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00430

- Laird, K. T., Vergeer, I., Hennelly, S. E., & Siddarth, P. (2021). Conscious dance: Perceived benefits and psychological well-being of participants. Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice, 44, 101440. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctcp.2021.101440

- Larivière, N., Couture, É., Blackburn, C., Carbonneau, M., Lacombe, C., Schinck, S., David, P., & St-Cyr-Tribble, D. (2015). Recovery, as experienced by women with borderline personality disorder. The Psychiatric Quarterly, 86(4), 555–568. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11126-015-9350-x

- Lawn, S., & McMahon, J. (2015). Experiences of care by Australians with a diagnosis of borderline personality disorder. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 22(7), 510–521. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpm.12226

- Lieb, K., Zanarini, M. C., Schmahl, C., Linehan, M. M., & Bohus, M. (2004). Borderline personality disorder. Lancet, 364(9432), 453–461. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16770-6

- Linehan, M. (2014). DBT Skills training manual. Guilford Publications.

- Lovell, LJ., & Hardy, G. (2014). Having a diagnosis of borderline personality disorder in a forensic setting: A qualitative exploration. Journal of Forensic Practice, 16(3), 228–240.

- McNiff, S. (2004). Art heals: How creativity cures the soul, Shambala. Shambhala Publications.

- Moon, B. L. (2016). Art-based group therapy: Theory and practice. Charles C Thomas.

- Moran, P., Romaniuk, H., Coffey, C., Chanen, A., Degenhardt, L., Borschmann, R., & Patton, G. C. (2016). The influence of personality disorder on the future mental health and social adjustment of young adults: a population-based, longitudinal cohort study. The Lancet. Psychiatry, 3(7), 636–645. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30029-3

- Morgan, L., Knight, C., Bagwash, J., & Thompson, F. (2012). Borderline personality disorder and role of art therapy: a discussion of its utility from the perspective of those with a lived experience. International Journal of Art Therapy, 17(3), 91–97. https://doi.org/10.1080/17454832.2012.734836

- Morris, N. (2018). Dramatherapy for borderline personality disorder: Empowering and nurturing people through creativity. Routledge.

- Ng, F. Y. Y., Townsend, M. L., Miller, C. E., Jewell, M., & Grenyer, B. F. S. (2019). The lived experience of recovery in borderline personality disorder: A qualitative study. Borderline Personality Disorder and Emotion Dysregulation, 6(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40479-019-0107-2

- Ng, F. Y. Y., Bourke, M. E., & Grenyer, B. F. S. (2016). Recovery from borderline personality disorder: A systematic review of the perspectives of consumers, clinicians, family and carers. PloS One, 1, 11(8), e0160515. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0160515

- NHMRC. (2012). Clinical practice guideline for the management of borderline personality disorder. NHMRC.

- O”Reilly, M., Svirydzenka, N., Adams, S., & Dogra, N. (2018). Review of mental health promotion interventions in schools. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 53(7), 647–662. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-018-1530-1

- Paris, J. (2006). Managing suicidality in patients with borderline personality disorder. Psychiatric Times, 23(8), 34.

- Rehman, A. (2020). An exploration of artistic creation in makerspaces and youth identity. [Doctoral dissertation]. University of Ontario Institute of Technology (Canada).

- Reupert, A., Price-Robertson, R., & Maybery, D. (2017). Parenting as a focus of recovery: A systematic review of current practice. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 40(4), 361.

- Salvatore, J. (2017). Ethnodrama and ethnotheatre. In Patricia Leavy (Ed.). Handbook of Arts-Based Research (pp. 267–287). Guilford Press.

- Shepherd, A., Sanders, C., & Shaw, J. (2017). Seeking to understand lived experiences of personal recovery in personality disorder in community and forensic settings: A qualitative methods investigation. BMC Psychiatry, 17(1), 282–210. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-017-1442-8

- Stone, M. H. (2017). Borderline patients: 25 to 50 years later, with commentary on outcome factors. Psychodynamic Psychiatry, 45(2), 259–296. https://doi.org/10.1521/pdps.2017.45.2.259

- VicHealth (2015). VicHealth Mental Wellbeing Strategy 2015-2019. Available at: https://www.vichealth.vic.gov.au/sites/default/files/VicHealth-Mental-Wellbeing-Strategy-2015-2019.pdf

- Wang, X., Hegde, S., Son, C., Keller, B., Smith, A., & Sasangohar, F. (2020). Investigating mental health of US college students during the COVID-19 pandemic: Cross-sectional survey study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(9), e22817. https://doi.org/10.2196/22817

- Warne, T., & McAndrew, S. (2007). Bordering on insanity: Misnomer, reviewing the case of condemned women. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 14(2), 155–162.

- Widiger, T. A. (1998). Invited essay: Sex biases in the diagnosis of personality disorders. Journal of Personality Disorders, 12(2), 95–118. https://doi.org/10.1521/pedi.1998.12.2.95

- Wirth-Cauchon, J. (2001). Women and borderline personality disorder. Rutgers University Press.

- Williams, E., Dingle, G. A., Jetten, J., & Rowan, C. (2019). Identification with arts-based groups improves mental wellbeing in adults with chronic mental health conditions. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 49(1), 15–26. https://doi.org/10.1111/jasp.12561

- Wlodarczyk, J., Lawn, S., Powell, K., Crawford, G. B., McMahon, J., Burke, J., Woodforde, L., Kent, M., Howell, C., & Litt, J. (2018). Exploring general practitioners” views and experiences of providing care to people with borderline personality disorder in primary care: A qualitative study in Australia. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(12), 2763. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15122763

- Woods, W. C., Arizmendi, C., Gates, K. M., Stepp, S. D., Pilkonis, P. A., & Wright, A. G., (2020). Personalized models of psychopathology as contextualized dynamic processes: An example from individuals with borderline personality disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 88(3), 240.

- Zanarini, M. C., Frankenburg, F. R., Reich, D. B., & Fitzmaurice, G. (2010). Time to attainment of recovery from borderline personality disorder: A 10-year prospective follow-up study. American Journal of Psychiatry, 167(6), 663–667. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09081130