ABSTRACT

In the face of immense pressure from Spanish, the national language, a group of educators in Michoacán are committed to prioritising P’urhepecha in two local primary schools where P’urhepecha is the dominant community language. The history of educational initiatives among the P’urhepecha people illustrates the inconsistent and primarily assimilationist educational environment faced by indigenous populations in Mexico, providing context for the schools’ efforts, which encourage literacy skills in both languages. We analyse the biliteracy development of a group of 4th grade students, qualitatively analysing written production in both P’urhepecha and Spanish, with a focus on patterns in orthographic conventions, lexicon (including borrowing and language mixing), sentence structure, and morpho-syntactic complexity. The students clearly have more developed writing skills in P’urhepecha than in Spanish, producing longer, more coherent texts in their mother tongue, and using more variation in vocabulary and tenses. Yet in both languages, the students find creative and unconventional ways to represent oral language in writing. Through this initial analysis of 24 student essays, we consider the interrelationship among literacy skills in two languages, the impact of this educational initiative in terms of biliteracy development, as well as practical implications for educational practices at the bilingual schools.

Introduction

Over the centuries, educational opportunities for P’urhepecha children in the rural highlands of Michoacán have been limited, and formal education has primarily been available through Spanish-medium instruction. Developing academic skills in P’urhepecha has received relatively little attention. While few would argue against the importance of learning Spanish for educational advancement in Mexico, for many indigenous children the ‘sink-or-swim’ submersion in Spanish in early primary school has been educationally obstructive. Much research has focused on the value of acquiring basic literacy skills in a language familiar to the child, in this case P’urhepecha, skills that can then be transferred to another language (Baker Citation2011; Cummins Citation1981; Francis Citation2011; García Citation2011; Thomas and Collier Citation2003). In theory, literacy skills in a first and second (or additional) language influence each other through an underlying linguistic competence (Cummins Citation1979, Citation1991). Similarly, the development of receptive and productive skills in both speaking and writing are all interrelated in contexts of biliteracy, and the development of biliteracy skills is facilitated when children are encouraged to draw on all their linguistic resources, especially those traditionally seen as less valuable (Hornberger Citation1989, Citation2003; Hornberger and Skilton-Sylvester Citation2000). Often such opportunities are constrained by an ideological environment that favours monolingualism in the dominant language and by a policy environment that limits the implementation of multilingual pedagogies. Sometimes, however, ideological and implementational spaces can be opened up for increasing multilingual practice in educational contexts (Hornberger Citation2002, Citation2005).

In the following section, we provide the historical context of educational opportunities for P’urhepecha-speakers, few of which have built on their existing language skills. Next, we contextualise our study by introducing two Spanish-P’urhepecha bilingual schools in which the indigenous language has been prioritised in all areas of education. We then present our preliminary qualitative exploration of the impact of this educational initiative in terms of biliteracy development, taking into account the relationship between literacy skills in two languages. We conclude with a discussion of the theoretical implications of this analysis regarding the nature of biliteracy as well as practical implications of educational practices in bilingual schools.

Indigenous language and education in Mexico

Education among indigenous groups in Mexico dates back to the time preceding the arrival of the Spanish in 1521. Specifically, institutes for educating P’urhepecha children of various backgrounds existed during the period of the Tarascan StateFootnote1 (c. 1350–1521), in which the medium of instruction was likely P’urhepecha. The early chronicler of P’urhepecha, and the author of its first grammar (1558) and dictionary (1559), Maturino Gilberti, refers to these institutes as Uachao ‘place of the children’ (Tomás and Chapina Citation2008: 67).

P’urhepecha education prior to the imposition of Spanish language and culture followed its own long-standing oral tradition, especially within the family. Indeed, the family was the core of much education, transmitting cultural traditions, ideas, religion and rituals from generation to generation by rote learning (Niniz Romero Citation2015: 52–53). Oral tradition also formed the basis of learning in the Uachao mentioned above. The children of nobility also received moral and written training. The use of P’urhepecha is a practice that we see revived in the two present-day primary schools examined in this study.

The first efforts at ‘educating’ the P’urhepecha during the Colonial period were undertaken by friars of various orders, who emphasised education, evangelisation and vocational training for specific occupations. Basic literacy skills were taught for the purpose of understanding and replicating the catechisms and religious manuals. The friars also learned the indigenous language and taught literacy as well as Christian doctrine, resulting in the production of grammars and dictionaries as early as the mid-sixteenth century, thus predating some European languages in their grammar-writing tradition. From 1533 onwards, seven Jesuit-run schools for indigenous children were in operation in Michoacán, forming part of the largest network of teaching establishments in the province of New Spain. These institutions were considered particularly prestigious for their teaching methods and their high level of instruction (Tomás and Chapina Citation2008: 31).

Given the importance of language in the successful colonisation of Mexico, legislation regarding the teaching of Spanish to indigenous groups began as early as 1550. With the revision of the Law of the Indies in 1680, Charles II (of Spain) sent additional priests to Mexico to educate the large but also largely illiterate population. In 1753, the Spanish Archbishop Manuel José Rubio y Salinas decreed that all parishes must establish Spanish language schools to teach indigenous children. The goal of establishing these schools later became clear: to put an end to the use of national (i.e. indigenous) languages in Mexico to avoid inter-group antagonism and ultimately rebellion (Tomás and Chapina Citation2008: 40).Footnote2

Despite the establishment of schools and the efforts of various religious orders over a number of centuries, by the beginning of the twentieth century, illiteracy was still a major problem amongst the indigenous peoples of Mexico, contributing to a vast social imbalance. During Porfiriato (1877–1910),Footnote3 indigenous peoples continued to live under opression, with the idea prevalent among the Spanish that they were not even human and were thus incapable of learning. Unsurprisingly, then, education remained out of reach for rural and indigenous communities in this period (see Niniz Romero Citation2015: 65). On the basis of the Decreto de las Escuelas de Instrucción Rudimentaria ‘Decree of Schools of Rudimentary Education’, the first entry-level schools for indigenous peoples were founded in 1911. The aim of these schools was to teach indigenous children to speak, read and write Spanish. However, only two courses were offered annually and they were not obligatory; moreover, no teacher training existed for such institutes. It is therefore unsurprising that this initiative lasted only for a short time, until 1922. However, just a year earlier (in 1921), the Secretariat of Public Education (SEP) had been founded to combat ‘poverty and ignorance’ and to try to resolve the social inequalities partly driven by the continued lack of education for indigenous peoples. The first Secretary of the SEP, Jose Vasconcelos Calderón (in post 1921–1924), following his long-term vision of integrating indigenous and Hispanic citizens into a single Mexican identity, proposed education for children from all social groups (Schmelkes et al. Citation2009: 252). During his tenure, Vasconcelos oversaw the publication of large numbers of textbooks for this newly expanded public school system. This initiative was replicated in 1958, with the creation of the Comisión Nacional de los Libros de Textos Gratuitos ‘National Commission of Free Textbooks’. The published books, however, were monoculturally Spanish and lacked information on indigenous traditions. The 1920s and 1930s saw a number of other initiatives aimed at improving literacy rates; in Michoacán, these included regional and national teacher training programmes, two indigenous internados ‘boarding schools’ (Tomás and Chapina Citation2008), as well as Moisés Sáenz’s short-lived Proyecto Carapan ‘Carapan Project’, targeting one of the four P’urhepecha-speaking regions in Michoacán in order to identify key challenges to indigenous education (Schmelkes et al. Citation2009: 255).

A further step towards a more integrated educational approach was set in motion during the presidency of Lázaro Cárdenas (1934–1940). Building on the ideas of Manuel Gamio,Footnote4 whose new nation-building enterprise required taking the indigenous reality of Mexico into consideration, he created the Departamento de Asuntos Indígenas ‘Department of Indigenous Affairs’ in 1939 (Hernández Citation2003: 16). This department held the first Assembly of Philologists and Linguists the same year in Pátzcuaro, the historic centre of the Tarascan State. On the basis of the recommendations of this meeting, the Proyecto Tarasco ‘Tarascan Project’ was created, with its seat in Paracho. The project fostered literacy and language maintenance in P’urhepecha by teaching literacy in the indigenous language, which then also served as a bridge for becoming literate in Spanish. A team of American and Mexican linguists, led by Morris Swadesh, who later published a grammar of sixteenth-century P’urhepecha (Swadesh Citation1969), conducted fieldwork in several Purepecha villages. The team’s fieldwork enabled the creation of a suitable alphabet, modified from the Spanish alphabet with the addition of diacritics and IPA symbols, such as <š> and <ŋ>, which was used to develop a set of primers for pedagogical purposes, as well as instructional pamphlets regarding, for example, health and sanitation. Literacy classes were taught by twenty specially selected and trained native speakers. According to Barrera-Vásquez (Citation1953: 83), the project was successful, with previously illiterate individuals learning to read and write in P’urhepecha in 30–45 days. The project regrettably ended abruptly in 1940, due to a change in administration, having only operated for about a year (McQuown Citation1946). We can therefore only speculate about the longer-term impact of the programme and its potential for transferring P’urhepecha literacy skills to literacy in Spanish, with its own orthographic conventions.

Literacy campaigns continued and, recognising the need for bilingual teachers for bilingual children, culminated in 1964 with the creation of the Servicio Nacional de Promotores Culturales y Maestros Bilingües ‘National Service of Cultural Promotors and Bilingual Teachers’. Due to its linguistic diversity (which is now just a fraction of what it was in precolonial times, see Gerhard Citation1993 [Citation1972]; Bellamy Citation2018), the state of Michoacán recognised not only P’urhepecha-Spanish bilingual teachers, but also teachers of Mazahua, Otomí and Nahuatl. Children speaking one of these four languages had the option to study in a bilingual environment with a teacher who knew their language: an educational practice that was recognised as beneficial (López Citation2014: 25).

Earlier indigenous education models and initiatives were finally subsumed under the Dirección General de Educación Indígena (DGEI) ‘General Department of Indigenous Education’ in 1978. From this decade onwards, the primary education curriculum DGEI promoted was labelled ‘bilingual and bicultural,’ although in reality this meant a shared curriculum for all children nationally, irrespective of their mother tongue (Hamel Citation2016). Building on these integrationist bilingual and bicultural education attempts of the 1970s, educación intercultural bilingüe (EIB) ‘intercultural bilingual education’ was introduced across Mexico in the 1990s (Hamel Citation2008). EIB aims to integrate ‘content matters and competencies from indigenous funds of knowledge, as well as from national programmes, [and] should be integrated in a culturally and pedagogically appropriate curriculum’ (Hamel Citation2012: 1–2). In contrast to previous educational programmes, EIB aims to enable all children to get to know indigenous culture and language, as well as Spanish, so that they can form sound competencies, values, and ethnic identity (see also López Citation2009, Citation2014; Schmelkes Citation2004).

However, the experience of many children, including those in Michoacán, does not reflect the original aims of EIB. Many P’urhepecha children, depending on the region and village, still grow up using P’urehpecha at home and arrive at school with very little knowledge of Spanish. Most P’urhepecha-speaking children are not schooled in their native language first, or at all, nor do they study their ancestral culture and traditions. Instead, these children continue to be instructed through a system of ‘Castilanization’, with Spanish as the vehicle for literacy and content instruction for all subjects. Under EIB, government-run primary schools officially offer several hours a week of P’urhepecha classes, focusing only on language acquisition, albeit using some P’urhepecha-medium materials in the form of workbooks and storybooks. Thus, for P’urhepecha speakers, the child’s first language is taught as though it were a second language, if at all. The isolation of the indigenous language, here P’urhepecha, from the general curriculum and the lack of attention to children’s primary language can have a negative effect and often leads to a sterile, grammar-centred teaching method. P’urhepecha courses can currently be found at university level, but there are no P’urhepecha-medium secondary schools. Against this regional and national background, the efforts of the bilingual schools in San Isidro and Uringuitiro, described below, stand out as unique.

The history of educational initiatives targeting the P’urhepecha people illustrates the inconsistent and primarily assimilationist educational environment faced by this indigenous population. Over the years, several initiatives prioritised education through the medium of P’urhepecha, opening up an ideological space to counter Spanish-language dominance in education; however, as in the case when funds were cut for the Tarascan Project, the implementional space was limited. Although the EIB introduced in the 1990s opened up implementional space for an increased use of indigenous languages in education, ideological space has been lacking, and most educators have assumed the superiority of a Spanish-dominant educational environment (see Hornberger Citation2002, Citation2005). In recent educational statistics, indigenous populations are consistently shown to be disadvantaged throughout Mexico, averaging fewer years of formal education, lower test scores overall, and lower literacy rates (INEE Citation2008).

P’urhepecha bilingual education and biliteracy assessment

The implementation of intercultural bilingual education (EIB) in the rural P’urhepecha-speaking villages of San Isidro and Uringuitiro was initially as limited as in most primary schools in Michoacán. Spanish was dominant and educational outcomes were poor. However, in 1995, a small group of dedicated P’urhepecha teachers, including the former director of indigenous education in Michoacán and teachers trained in the principles of intercultural bilingual education, decided that they wanted something different for their schools. They generated parental support and committed to implementing a truly bilingual programme based on mother-tongue education in P’urhepecha with the twin aims of enabling access to education for the children and promoting P’urhepecha language and culture. This project is now known by the bilingual title T’arhexperakua – Creciendo juntos ‘growing together’. Several years later, in 1999, the teachers were joined by a team of researchers, headed by Enrique Hamel, from the Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana-Iztapalapa (Mexico City), first as observers and later as invited consultants, providing practical support in curriculum development, language policy and instruction, and teacher training (see Hamel Citation2006, Citation2008; Hamel et al. Citation2018).

As described by Hamel (Citation2008), ‘[i]n contrast to most indigenous schools in Mexico and elsewhere in Latin America, P’urhepecha had become the legitimate, unmarked language of all bilingual interaction at school, a sociolinguistic achievement still quite exceptional in indigenous education.’ P’urhepecha is, thus, the default medium of instruction, with Spanish introduced gradually over the six years of primary school. Among the basic principles of the two neighbouring schools is the centrality of P’urhepecha for all subjects, not only for specifically indigenous content or cultural values. Spanish is treated as a second or additional language for the students, a language they are not expected to have learned before entering school. However, both languages are used for all subject content, following the principles of content and language integrated learning (CLIL) (Hamel and Francis Citation2006).

According to the plan for second language acquisition, oral Spanish is introduced in Grades 1 and 2 through second-language learning activities and with some incorporation of Spanish into thematic units using CLIL techniques. Spanish reading and writing are not taught systematically in these first two years as the emphasis is on first developing mother-tongue literacy in P’urhepecha. Grades 3 and 4 continue with oral Spanish, adding Spanish reading and writing, and activating transfer of these literacy skills from the first language. Teachers are instructed not to worry about first language interference in orthography and syntax. These grades also include some Spanish in thematic units, including more components of the primary subject materials. In Grades 5 and 6, the teachers are encouraged to teach one or two subjects in Spanish or to divide one subject for partial teaching in each language, the goal being one hour of Spanish per day. Shortcomings in the programme have naturally been identified over the years, triggering improvements in pedagogy and teaching methodology, Spanish as a second language instruction, and the development of a truly intercultural curriculum, initiatives which are still underway (Groff Citation2014; Hamel et al. Citation2004).

Corroborating the findings of Hamel et al., the first author made the following general observations over the course of nine multiple-day site visits in 2012–2014: P’urhepecha was the primary language used (over 75%) in all grades, while Spanish was the marked language in the classroom. Students were accustomed to a complete switch to Spanish for a particular lesson or activity, shouting together after the teacher’s instructions, ‘¡Ahora sólo español!’ ‘Now only in Spanish!’. These complete switches from one language to the other reflect the schools’ preference for separating the languages in the classroom, although more micro-level switches were also observable in some classes (Groff Citation2014). Space was available for students to participate in class, to talk and to interact, including peer-instruction. Contextualised learning was valued through close-to-home examples and hands-on learning. Content-based language teaching, as officially recommended in the school’s second language programme, was evidenced in the use of Spanish for instruction in all subject areas, although this appeared to happen less than the recommended hour a day. Although the educators themselves acknowledged room for improvement, the bilingual schools in San Isidro and Uringuitiro have been described as ‘extremely exceptional and original in the Mexican context’ (Hamel et al. Citation2004: 173). ‘With their new curriculum the teachers defied and overcame a series of ideological and political barriers that prevent a truly bilingual, intercultural, maintenance-oriented education in most cases’ (ibid, see also Hamel et al. Citation2018). Both ideological and implementational spaces have been created for a truly mother-tongue based bilingual programme for P’urhepecha children.

The educational outcomes associated with this programme have naturally been of interest, and the research team has focused some attention on helping the local teachers in the assessment process and writing samples. During initial observations at the schools, Hamel and team found it noteworthy that the students could write coherent texts in both languages by the third year and that in the fifth and sixth years they were writing much better in their second language than they could even speak. Assessments in both languages have shown students’ development across the grades. Unsurprisingly, P’urhepecha skills were consistently stronger than Spanish-language skills. However, Spanish and P’urhepecha language skills were clearly developing in a parallel way across the years, indicating positive transfer of first language skills to the second language (Hamel Citation2009). Given the students’ limited exposure to Spanish, the development of what is known as cognitive academic language proficiency (CALP) was happening primarily though P’urhepecha (ibid; Cummins Citation1991, Citation2000). In a comparison of 161 students from the San Isidro and Uringuitiro schools with 158 students at a parallel school teaching P’urhepecha children only through Spanish, the students at the bilingual schools scored significantly higher in assessments of written expression in both P’urhepecha and Spanish (Hamel Citation2009).

The following section focuses on our analysis of biliteracy development among grade 4 students at the two schools as evident in assessments of written expression. Preliminary analysis of writing samples in P’urhepecha highlights the students’ ability to creatively represent their colloquial version of the language, including lexical borrowings from Spanish incorporated into their native grammatical system (Bellamy and Groff Citation2019). We now extend the qualitative analysis to written production in both P’urhepecha and Spanish.

Written expression in Spanish and P’urhepecha

This qualitative analysis is based on 24 written-expression essays produced at the end of the school year by students in one of the two Grade 4 classes in San Isidro. We analysed the essays of the 12 (out of 16) students who were present for both the Spanish and the P’urhepecha assessments. In producing the essays analysed here, students were asked to retell a story that they had just heard orally. The resulting essays gauge both the students’ oral comprehension of the story and, more importantly, their ability to express the story in their own words in writing. The students themselves seemed focused on filling the pages with text, resulting in some repetition and lack of coherence, especially for students with lower Spanish skills. As part of a larger, school-wide assessment, the teachers had scored these essays globally and for content (ability to reproduce 12 different episodes or segments of the story). The students missed many story segments in both languages. Out of 36 possible points (3 per episode), the highest score was only 17. The average score by episode was 5.1 for the Spanish essays and 7.8 for the P’urhepecha essays. In the global scoring, the teachers evaluated the essays in both P’urhepecha and Spanish at 3–4 on average (out of 10), which was defined in the scoring rubric as follows: containing narrative fragments, mention of characters, disconnected phrases and in some cases problems with comprehensibility. The assignment was clearly challenging for the students, and creating a coherent narrative was difficult for them in both languages, but especially in Spanish. Our analysis of these essays focuses more on linguistic features and is an initial attempt to find points of comparison between the essays in the two languages, which we also plan to compare with students’ oral skills. In this section, we will focus on four aspects of the children’s writing competence, namely orthography, lexicon, sentence structure, and morpho-syntactic complexity.

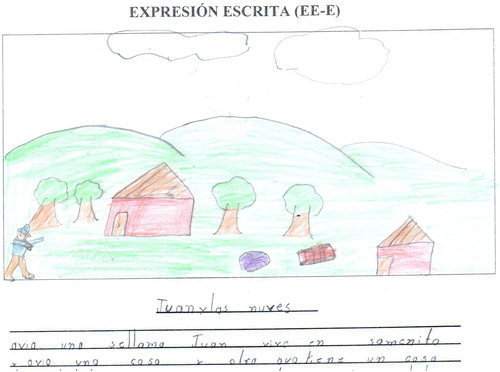

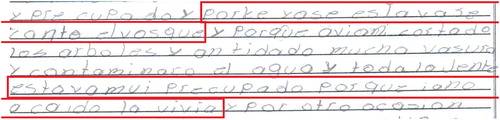

The Spanish story is called Juan y las nubes ‘Juan and the clouds’, a morality story about the importance of looking after the environment (see ). The students’ Spanish skills varied considerably. Most students struggled to express themselves in Spanish, making use of various strategies in their attempts, especially repetition and the use of fixed expressions. Working within a limited Spanish vocabulary, their aspiration to fill the page with writing seemed to motivate the students to keep trying, which may in itself have pedagogical value. The students frequently repeat words and expressions and attempt similar constructions in subsequent sentences, providing opportunities for self-correction in spelling and grammar. For example, a student spelled the word porque ‘because’ as porke and then used the correct spelling in the following line.

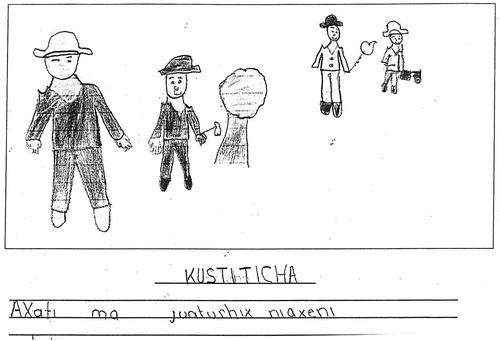

The P’urhepecha story is called kustiticha ‘the musicians’, and recounts the adventures of a group of musicians in a forest (see ). In general, the children performed much better in this task than in the Spanish writing test, producing more text (i.e. complete lines) and providing more complete phrases, even if some are difficult for the outsider to analyse. On the whole, the students expressed themselves more clearly; the key ideas of the story were expressed in a largely comprehensible manner.

Orthography

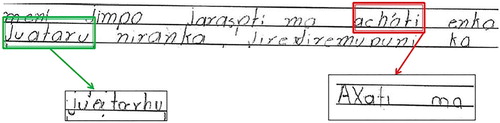

Regarding orthography, the first noticeable feature is the absence of capital letters and full stops in the written texts in both languages. The students clearly did not prioritise capitalisation and punctuation in conveying their message, despite the alphabet poster in the classroom which provides both small and capital letters for writing P’urhepecha. Accent marks, indicating stress in words with non-canonical stress patterns, are also lacking. The Spanish-language texts are full of unconventional spellings that reflect the way the words sound to the students. For example, in the 12 Spanish essays, the town of San Benito is spelled in at least 15 different ways, with alternations in the representation of vowels, alternation between <n> and <m> in San, alternation among, <b>, <v> and <p> in Benito, as well as the combination of the two words into one. These inconsistencies in representation of phonemes and in word splitting are among the many examples of the students’ incorporation of oral features into their writing. An additional example, in a sentence about taking care of the forest, is vamos a cuidar ‘we are going to take care of’, which is expressed in writing as ‘pamosa cuar’ (See ).

The example shown in also demonstrates the frequent use of the letter <v> for <b>, as in ‘vasura’ for basura ‘trash’ and ‘vosque’ for bosque ‘forest’, which is unsurprising since [v] is an allophone of [b] (along with [β]) in spoken Mexican Spanish (Greet Cotton and Sharp Citation1988: 153). Besides deviations from conventions as in the use of <ll> for <y>, we also find <d> for <r> as in ‘han tidado’ for han tirado ‘have thrown’, as well as <c> for <g> as in ‘honcos’ for hongos ‘mushrooms’, which may well reflect the contrast between stops after nasals and their written representation found in the P’urhepecha stories (see below). The omission of orthographic word-initial <n> is also common in words such as había ‘had’ and hongos ‘mushrooms’, where the /h/ is indeed not pronounced. Occasionally word-final <n>, which is present both phonetically and orthographically, is dropped, as in contaminaro(n) ‘they contaminated’. Besides using oral features in their writing, the students show frequent orthographic inconsistencies within the same essay, sometimes indicating self-correction in the writing process.

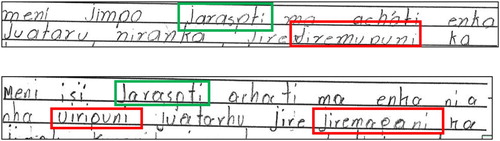

In the P’urhepecha writing samples, a certain amount of inconsistency exists among students, but generally the orthography is more coherent than that of the Spanish texts, indicating an internalisation of the rules taught. The few inconsistencies include the use of the graphemes <ch> and <x> for the sound [tʃ], generally written as <ch>. In written P’urhepecha it is generally accepted that the grapheme <x> represents the sound [ʃ], an orthographic convention introduced in early colonial times, being present already in Gilberti’s (Citation1559) dictionary of the language (see Lemus Jiménez and Márquez Trinidad Citation2012). Additionally, we observe a convergence of <r> (representing the tap rhotic [ɾ]) and <rh> (reflecting the retroflex rhotic [ɽ]), to represent one or the other orthographically.Footnote5 See for examples of all of these spelling discrepancies.

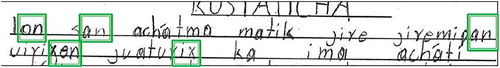

Sometimes, the spelling used by the children represents the underlying phonemic forms rather than the audible phonetic units. In spoken P‘urhepecha, for example, stops following a nasal are voiced, hence, orthographic <mp> is pronounced [mb] and orthographic <nk>/ as [ng]. This would indicate that the (here, voiceless) conventions have been well entrenched through teaching (see also Bellamy and Groff Citation2019: 213). A further influence from the spoken language is the frequent omission of word-final -i, contradicting common orthographic conventions, which represent the underlying requirement for open syllables word-finally (e.g. Chamoreau Citation2003: 48). In , we clearly observe the lack of <i> at the end of the words ioni, sani ‘some, a little’, jiremipan, uirixen ‘run’, and juaturix, which should all terminate in this vowel symbol.

Overall, in the P’urhepecha essays, the students are clearly applying the rules taught at the school. While they do use a combination of phonemic and phonetic representations in writing, there is a great deal of consistency, especially in comparison with the Spanish essays, strongly suggesting that the instructed norm is ‘winning out’.

Lexicon

Turning to the lexicon, the students’ written expression in Spanish reflects their limited vocabulary in that language. Interestingly, they do not borrow from P’urhepecha lexically to expand the content of their essays. Instead, students use some creative constructions to express ideas; for example, the use of muy lloren ‘very they cry’ to express sadness. Other strategies used to compensate for their limited Spanish vocabulary include frequent repetition and the use of fixed expressions common in oral interaction in groups of children but slightly informal for a written essay, such as vénganse todos ‘come on, everyone’ and vámanos ‘let’s go’.

Generally, the lexical items used in the P’urhepecha writing samples are more varied than in the Spanish ones, reflecting a larger active vocabulary. In contrast, unlike in the Spanish writing samples, in P’urhepecha the children have recourse to words from their other language, sometimes as ad hoc loans from Spanish but sometimes also integrated. Notable integrated loans, which also presumably indicate a loss of interest in the task at hand, are: karaju (from the Spanish carajo, a somewhat vulgar exclamation of surprise or annoyance, which occurred in three separate writing samples) and its P’urhepechised plural formation karajucha (not expected in Spanish), and chihadurha (reflecting the Spanish chingadura ‘shit(ty thing)’, which occurred only once). The first term shows the characteristic raising of /o/ to /u/ in word-final position in P’urhepecha, a process that also extends to loanwords from Spanish, indicating that this term has been integrated into the children’s first language.Footnote6

That systematic loans reflect P’urhepecha pronunciation, is shown in their spelling. Take the written form tampor(h)u ‘drum’ from the Spanish tambor, for example. In the P’urhepecha variant, we observe what may be a hypercorrection of the Spanish letter to <b> to <p>, which seems to follow the spelling conventions mentioned above, whereby phonemic rules are followed. Specifically, the underlying P’urhepecha form /mp/ is reflected in the spelling rather than the phonetic realisation [mb], in which the voicing of the nasal phoneme spreads to the following plosive. If the phonetic form were to be followed, we would expect tamboru instead. The word-final /u/ has likely been inserted in order for the word to adhere to rules of P’urhepecha syllable structure, which disallows final closed syllables. The systematic integration of this term likely signifies that it, too, has become an integrated loanword in the P’urhepecha lexicon.

Sentence structure and morpho-syntactic complexity

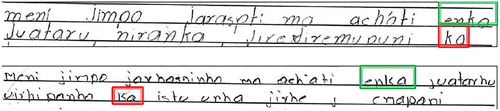

The Spanish essays included many simple and incomplete sentences, although their analysis is complicated by the lack of punctuation and inconsistent spacing between words. Most of the students were working with limited Spanish skills; however, they attempted some complex structures, and the range of abilities varied considerably. For example, one of the more advanced students composed the following segments, which, although not error-free, include past progressive with the reflexive form (underlined), and past and present perfect (in bold); see , examples (1a–b).

(1a) porque ya se estaba secando el bosque y porque habian cortado los arboles

‘because the forest was already being dried out and because they had cut the trees’

(1b) estaba muy preocupado porque ya no ha caido la lluvia

‘[he] was very worried because the rain had not yet fallen’

The sentences in the P’urhepecha stories are generally relatively complete and are for the most part linked together with the coordinator ka ‘and’. The heavy reliance on this conjunction may reflect the traditional P’urhepecha story-telling style, whereby two independent clauses or chain-medial clauses may be linked with this coordinator (Chamoreau Citation2016: 101). Dependent or relative clauses are marked with the subordinator enka, which also contains ka, indicative of this narrative clause-chaining technique. It is noteworthy that the openings of the stories are very similar across essays, although they do not match the opening recounted by the teacher, indicating a clear understanding of the story, familiarity with narrative style/technique and an ability to represent and reproduce it on the page (see ).

Figure 7. Example of story opening with classic narrative techniques (ka ‘and’ in red, and enka relative marker ‘where/when’ in green).

It is immediately obvious that the students are able to reproduce words with considerable morpho-syntactic complexity in P’urhepecha, despite its derivational and inflectional system being far more complex than that of Spanish. In the verbal domain, students use both finite and non-finite forms, as would be expected in a P’urhepecha narrative (see ). As indicated above, the use of non-finite forms, generally with the same subject, is very common. Additionally, we see various examples of verbs conjugated in the aorist (-s-) and past tense (-p-) to indicate ‘a large range of contexts, such as for narrative non-marked aspect, on-going situations with certain stative verbs, general truths with verbs of quality, the proximate past with verbs of action, and the expression of result with certain stative verbs’ (Chamoreau Citationforthcoming). The use of these two tense and aspect markers is fairly consistent in finite clauses, in which third person forms (i.e. the forms terminating in the third person maker -ta) are the most frequent because the hero of the story (thus the default grammatical subject) is a third person entity (thus, not a speech-act participant). That said, first person forms, terminating in -ka, are also found.

Furthermore, various examples of the accurate use of nominal morphology are evident. First is the use of the plural marker -cha, mainly for animates, as in kustaticha ‘‘musician’ (kustati-icha ‘musician-PL). In Bellamy and Groff (Citation2019), we noted that P‘urhepecha plural marking is also extended to Spanish animates in some cases; e.g. pajaritucha ‘little birds’ (pajarito-cha ‘little bird’-PL). This pluralisation is reflected, but only occasionally, in the current analysis, as in the case of kabronicha ‘idiots’ from Spanish cabrón.

Two of the seven cases are used in the writing samples analysed here, namely the objective -ni (which marks both direct and indirect objects) and the locative -rhu (see, e.g. Bellamy Citation2018 for a brief overview of P’urhepecha cases). Examples (2) and (3) illustrate these two cases in useFootnote7:

a jimaku ku-narhi-ku-ni materu achati-ni enka and then cross-SP.LOC.face-NCS-NF other man-OBJ when … ‘and then another man crossed over when … ’

ka juchenio parhats'ikwa-rhu yámu =ksï k'ama-cha-s-ti and my.house table-LOC everything=3.S.PL finish-ADV-PST-3.ASS ‘and they finished everything on our table’

The combination of Spanish and P’urhepecha features at both clause and word levels seems to suggest that the children are exposed to this kind of mixed input. Although the separation of languages in the classroom is officially advocated in our two schools, the features combined by native speakers could be useful in drawing students’ attention to language, which is also an important component of the schools’ curriculum.

Developing biliteracy: observations across languages and contexts

The students in San Isidro are clearly more confident and competent in P’urhepecha than they are in Spanish. This contrast was obvious in interactions with the students and is evident in their writing samples. Although they may have understood the main idea, many of the students found it difficult to reproduce the Spanish story, unlike in P’urhepecha, where the key ideas are developed with greater ease through longer, more complex sentences. Interestingly, our qualitative analysis of the 24 essays highlights the contrast in skills between the languages more than the global and content scores provided by the teachers. The initial qualitative analysis was intended to help identify areas in which comparisons would be possible, also with oral skills in the two languages. Greater competence in the mother tongue may not be surprising, but the superior writing competence in P’urhepecha also reflects the focus of instruction at the school. In the national, regional, and indeed historical context, literacy skills in the mother tongue would normally not be developed. Given the school’s focus on P’urhepecha literacy skills in the first two years, the Spanish literacy skills demonstrated by the students have been developed in less than two years of formal instruction, drawing on the skills already learned in the mother tongue.

The impact of a mother-tongue-based educational programme can be evaluated in many ways and certainly goes far beyond the development of basic literacy skills to personal development and cultural preservation. Although the assessment of academic skills is often overdone in educational contexts, and the results tell an incomplete story, assessments are nonetheless important in evaluating the success of a programme and in guiding improvements. Our contribution to this effort has been a qualitative analysis of written production by twelve Grade 4 students at the San Isidro primary school in the two languages of instruction. While limited in scope, our observations contribute to further analysis of the parallel development of biliteracy skills and bring attention to the importance of a detailed exploration of language-learning outcomes, especially in contexts of biliteracy with a strong power imbalance between the languages.

In general, we have noted a lack of basic writing conventions in the students’ written production in both languages, including a lack of punctuation, inconsistent spelling, few complete sentences, and line filling as a test-completion strategy. On the positive side, the students were not paralysed by fear of conventions and may have had a relatively holistic approach in their writing, focusing on the larger product rather than error-free production of individual sentences. The low priority of such writing conventions in instruction reflects the emphasis on oral, content-based learning in the school, which, in turn, may reflect the traditionally oral nature of P’urhepecha language and knowledge transmission. However, the students’ limitations in these basic writing skills could be overcome through more focused instruction without sacrificing the focus on content. Their absence reflects the educational challenges common in poorer areas of the country. The extreme disparities in Spanish-language skills compared with those in P’urhepecha also highlight the importance of improving second-language instruction so that children exposed to less Spanish outside the school are not disadvantaged at later stages of education. Although assessment was the primary goal of the assignment, the pedagogical value of such an activity could be enhanced if it were more attuned to the ability levels of the students, preventing discouragement and allowing them to build on existing knowledge.

The development of biliteracy in different contexts involves varying degrees of attention to the first and second (or additional) language, to oral versus written skills, and to receptive versus productive skills (Hernández Citation2003). According to Hornberger (Citation2003: 26). ‘ … the more the contexts of their learning allow [students] to draw on all points of the continua, the greater are the chances for their full biliterate development.’ Previous testing at the two bilingual schools shows evidence of the parallel development of first and second language skills, with first language skills consistently dominant, pointing to the positive transfer of writing skills from the first to the second language. In addition, the students’ writing skills in the two schools far exceeded those of a Spanish-dominant comparison school (Hamel Citation2009). In the written expression assessment analysed here, students’ oral comprehension of the text is reflected in their attempt to reproduce it, despite language limitations. This interplay between receptive and productive skills adds pedagogical value to the exercise. The obvious oral features in the students’ writing demonstrate how they draw upon the skills gained in everyday communication, applying them to an academic assignment. The use of oral features also shows the students’ ability to creatively express themselves in writing. Although the P’urhepecha samples display a closer connection to the original story, and therefore appear similar, carefully memorised and copied content is notably absent in this assignment.

In analysing connections between the students’ two languages, our attention is drawn to lexical borrowing from the second language, Spanish, to the first language, P’urhepecha. In our sample, borrowings in the opposite direction are not found, despite the students’ extreme language limitations in Spanish vocabulary. The direction of borrowing points to the higher status and prestige of Spanish (Blokzijl et al. Citation2017; Haspelmath Citation2009). Even when P’urhepecha is prioritised, monolingual preferences are evident in the separation of languages in school policy and classroom practice. Besides a degree of lexical borrowing from Spanish to P’urhepecha, the two languages were kept separate in the assignment presented here. The students’ ability to produce a comprehensible Spanish story (that is, a more coherent and ‘grammatical’ account) might have been facilitated if the children had been encouraged to fill the gaps in their Spanish knowledge with P’urhepecha words or expressions, as recommended in a translanguaging approach (García and Wei Citation2014). However, the separation of the two languages is important at the schools. Although P’urhepecha is given a more prominent place than Spanish in terms of teaching time and attention, reversing the power dynamics between the languages in wider society, the external power dynamics still influence the languages and their users, even in this sheltered environment.

In the learning of minority and endangered languages, power dynamics among languages is always an important contextual factor. At the two bilingual schools examined here, an attempt is made to prioritise a language that is widely treated as less important. Racism and discrimination also play a role, and in the P’urhepecha context, these still motivate the loss of indigenous identity along with the loss of language skills. The bilingual schools in San Isidro and Uringuitiro reverse the traditional power dynamics both in order to preserve P’urhepecha language and culture, and for the provision of adequate education to students who are (mostly) still dominant speakers of P’urhepecha. Such bilingual schools open up both ideological and implementational spaces for indigenous languages in academic contexts from which they have largely been excluded, promoting indigenous knowledge, facilitating access to the general curriculum, and allowing for the development of home language skills and the transfer of those skills to the dominant, national language.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded in part through a National Academy of Education / Spencer Foundation Postdoctoral Fellowship awarded to the first author and hosted by the Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana (UAM) Iztapalapa, and through Marie Skłodowska-Curie Individual Fellowships awarded to both authors (grant agreement numbers 752550 and 845430 for the first and second author respectively). We thank our editors and an anonymous reviewer for insightful comments and challenges, as well as Enrique Hamel for additional input and critiques, and for the original access to the field site and data.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID

Cynthia Groff http://orcid.org/0000-0002-9652-2094

Kate Bellamy http://orcid.org/0000-0001-5996-1736

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The Tarascan State or Empire is the name given to the socio-political organisation led by a group of P’urhepecha noblemen, who ruled roughly the same area as the current State of Michoacán. It is the only Mesoamerican State to have successfully repelled the Aztecs.

2 For more on language use for indigenous education in Mexico, see Francis and Reyhner (Citation2002) and Heath (Citation1972).

3 Named after the president of the period, Porfirio Diaz.

4 Manuel Gamio (1883–1960) is often considered to be the founder of modern Mexican anthropology, having completed his PhD with Franz Boas at Columbia University. He was also a leader of the indigenismo movement in Mexico.

5 Note that in some dialects and in the pronunciation of younger speakers, the retroflex rhotic [ɽ] has been replaced by the lateral [l] (Chamoreau Citationforthcoming; Chamoreau Citation1998: 109). However, the lack of confusion between these two phonemes in the children’s writing samples strongly suggests that the phonetic merger has not occurred in their dialect. Rather, [ɾ] and [ɽ] are phonetically close and, since they only occur word-medially, are hard to differentiate in normal speech even though their opposition enables the existence of a small number of minimal pairs.

6 Examples of the Spanish conjunction pero ‘but’ written as peru by various children support this phonetic representation in children’s written (and spoken) P’urhepecha.

7 Abbreviations: 3 – third person; ADV – adverbial; ASS – assertive; NCS – non-coreferential subject; NF – non-finite; OBJ – objective; PL – plural; PST – past tense; S – subject

References

- Baker, C. 2011. Foundations of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

- Barrera-Vásquez, A. 1953. The Tarascan project in Mexico. In The Use of Vernacular Languages in Education, ed. UNESCO, 77–86. Paris: UNESCO.

- Bellamy, Kate. 2018. On the external relations of Purepecha: an investigation into classification, contact and patterns of word formation. PhD diss., Leiden University.

- Bellamy, Kate and Cynthia Groff. 2019. Mother tongue instruction and biliteracy development in P'urhepecha in Central Mexico. In Teaching Writing to Children in Indigenous Languages: Instructional Practices from Global Contexts, ed. Ari Sherris, and Joy Kreeft Peyton, 202–217. New York: Routledge.

- Blokzijl, J., M. Deuchar and M.C Parafita Couto. 2017. Determiner asymmetry in mixed nominal constructions: the role of grammatical factors in data from Miami and Nicaragua. Languages 2, no. 20.

- Chamoreau, Claudine. 1998. Description du purépecha, parlé sur des îles du Lac du Patzcuaro (Mexique). PhD diss., Université Paris V – Henri Descartes.

- Chamoreau, Claudine. 2003. Parlons Purepecha, une langue du Mexique. Paris: L’Harmattan.

- Chamoreau, Claudine. 2016. Non-finite chain-medial clauses on the continuum of finiteness in Purepecha. In Finiteness and Nominalization, ed. Claudine Chamoreau and Zarina Estrada-Fernández, 83–104. Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

- Chamoreau, Claudine. forthcoming. Purepecha: a non-Mesoamerican language in Mesoamerica. In The Languages of Middle America: A Comprehensive Guide, ed. Søren Wichmann. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

- Cummins, Jim. 1979. Linguistic interdependence and the educational development of bilingual children. Review of Educational Research 49, no. 2: 222–251.

- Cummins, Jim. 1981. Bilingualism and Minority-Language Children. Toronto: Ontario Inst. for Studies in Education.

- Cummins, Jim. 1991. Interdependence of first-and second-language proficiency in bilingual children. In Language Processing in Bilingual Children, ed. Ellen Bialystok, 70–89. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Cummins, Jim. 2000. Language, Power and Pedagogy. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

- Francis, Norbert. 2011. Bilingual Competence and Bilingual Proficiency in Child Development. Cambridge, MA and London, England: MIT Press.

- Francis, Norbert and Jon Reyhner. 2002. Language and Literacy Teaching for Indigenous Education: A Bilingual Approach. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

- García, Ofelia. 2011. Bilingual Education in the 21st Century: A Global Perspective. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

- García, Ofelia and Li Wei. 2014. Translanguaging: Language, Bilingualism and Education. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Gerhard, Peter. (1972) 1993. A Guide to the Historical Geography of New Spain (Revised edition). Norman and London: University of Oklahoma Press.

- Gilberti, Maturino. (1559) 1975. Diccionario de la lengua Tarasca o de Michoacan, edición facsimilas, con nota preliminar de José Corona Nuñez. Reprint. Morelia: Balsal.

- Greet Cotton, Eleanor and John M. Sharp. 1988. Spanish in the Americas. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press.

- Groff, Cynthia. 2014. Biliteracy development in primary school: bilingual education in the Mexican indigenous-language context. Paper presented at early language learning theory and practice, June 12–14, Umeå, Sweden.

- Hamel, Rainer Enrique. 2006. Indigenous literacy teaching in public primary schools: a case of bilingual maintenance education in Mexico. In One Voice, Many Voices: Recreating Indigenous Language Communities, ed. T.L. McCarty and O. Zepeda, 149–176. Tempe: Arizona State University Center for Indian Education.

- Hamel, Rainer Enrique. 2008. Bilingual education for indigenous communities in Mexico. In Bilingual Education. Vol. 5 of The Encyclopedia of Language and Education, 2nd ed., ed. James Cummins and Nancy H. Hornberger, 311–322. New York: Springer.

- Hamel, Rainer Enrique. 2009. La noción de calidad desde las variables de equidad, diversidad y participación en la educación bilingüe intercultural. Revista Guatemalteca de Educación 1, no. 1: 177–230.

- Hamel, Rainer Enrique. 2012. Multilingual education in Latin America. In The Encyclopedia of Applied Linguistics, ed. C. A. Chapelle. Hoboken, NJ: Blackwell Publishing. doi:10.1002/9781405198431.wbeal0787.

- Hamel, Rainer Enrique. 2016. Bilingual education for indigenous peoples in Mexico. In Bilingual and Multilingual Education. Encyclopedia of Language and Education, 3rd ed., ed. O. Garcia, A. Lin and S. May, 1–13. Cham: Springer.

- Hamel, Rainer Enrique and Norbert Francis. 2006. The teaching of Spanish as a second language in an indigenous bilingual intercultural curriculum. Language, Culture and Curriculum 19, no. 2: 171–188.

- Hamel, Rainer Enrique, María Brumm, Antonio Carrillo Avelar, Elisa Loncon, Rafael Nieto and Elías Silva Castellón. 2004. ¿Qué hacemos con la castilla? La enseñanza del español como segunda lengua en un currículo intercultural bilingüe de educación indígena. Revista mexicana de investigación educativa 9, no. 20: 83–107.

- Hamel, Rainer Enrique, Ana Elena Erape Baltazar and Betzabé Márquez Escamilla. 2018. La construcción de la identidad p’urhepecha a partir de la educación intercultural bilingüe propia. Trabalhos em Linguística Aplicada 57, no. 3: 1377–1412. doi:10.1590/010318138653739444541.

- Haspelmath, M. 2009. Lexical borrowing: concepts and issues. In Loanwords in the World’s Languages: A Comparative Handbook, ed. M Haspelmath and U. Tadmor, 35–54. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton.

- Heath, Shirley Brice. 1972. Telling Tongues: Language Policy in Mexico: Colony to Nation. New York: Teachers College Press.

- Hernández, Natalio. 2003. De la educación indígena a la educación intercultural: La experiencia de México. In La Educación Indígena en las Américas / Indigenous Education in the Americas (Spanish Edition with English Translations), ed. World Learning, 15–24. Brattleboro: School for International Training. https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/sop/1.

- Hornberger, Nancy H. 1989. Continua of biliteracy. Review of Educational Research 59, no. 3: 271–296.

- Hornberger, Nancy H. 2002. Multilingual language policies and the continua of biliteracy: An ecological approach. Language Policy 1, no. 1: 27–51.

- Hornberger, Nancy H., ed. 2003. Continua of Biliteracy: An Ecological Framework for Educational Policy, Research, and Practice in Multilingual Settings. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

- Hornberger, Nancy H. 2005. Opening and filling up implementational and ideological spaces in heritage language education. Modern Language Journal 89, no. 4: 605.

- Hornberger, Nancy H. and Ellen Skilton-Sylvester. 2000. Revisiting the continua of biliteracy: international and critical perspectives. Language and Education 14, no. 2: 96–122.

- INEE (Instituto Nacional de Evaluación Educativa). 2008. La educación para poblaciones en contextos vulnerables: Informe Anual 2007. México: INEE.

- Lemus Jiménez, Alicia and Joaquin Márquez Trinidad. 2012. Jiuatsï 1: Cuaderno de Enseñanza de la Lengua P'urhepecha I. Cherán: Instituto Tecnológico Superior P'urhepecha.

- López, Luis E. 2009. Reaching the unreached: indigenous intercultural bilingual education in Latin America. Paper commissioned for the EFA Global Monitoring Report 2010. UNESCO.

- López, Luis E. 2014. Indigenous intercultural bilingual education in Latin America: widening gaps between policy and practice. In The Education of Indigenous Citizens in Latin America, ed. Regina Cortina, 19–49. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

- McQuown, Norman. 1946. Primers. Maya-Spanish, Otomi-Spanish, Tarascan-Spanish, Nahuatl-Spanish, Nahuat-Spanish—secretary of public education national Campaign against illiteracy, institute of literacy training in indigenous languages, Mexico, DF, 1946—99,140,192,139 and 166 pages, respectively. Boletin Bibliografico de Antropologia Americana 9: 263–265.

- Niniz Romero, Dora María. 2015. La normal indígena de Michoacán, su diseño curricular. Morelia: Instituto Michoacano de Ciencias de la Educación.

- Schmelkes, Sylvia. 2004. La educación intercultural: Un campo en proceso de consolidación. Revista Mexicana de Investigación 9, no. 20: 9–13.

- Schmelkes, S., G. Águila and M.A. Núñez. 2009. Alfabetización de jóvenes y adultos indígenas en México. In Alfabetización y multiculturalidad. Miradas desde América Latina, ed. L.E. López and U. Hanemann, 237–290. Guatemala City: UNESCO-UIL, GTZ.

- Swadesh, Muaricio. 1969. Elementos del tarasco antiguo. Mexico City: Instituto de Investigaciones Históricas, UNAM.

- Thomas, W. P. and V. P. Collier. 2003. The multiple benefits of dual language: dual language programs educate both English learners and native English speakers without incurring extra costs. Educational Leadership 61, no. 2: 61–64.

- Tomás, Casimiro Leco and J. Guadalupe Tehandón Chapina. 2008. La escuela normal indígena de Michoacán: Historia, pedagogía e identidad étnica. Morelia: Universidad Michoacana de San Nicolas de Hidalgo/Instituto de Investigaciones Económicas y Empresariales/Escuela Normal Indígena de Michoacán.