Abstract

Few people who did not grow up speaking Zulu have learned the language later. There are limited resources for second language Zulu learning, whether textbooks, readers, or computerised resources. We set out to develop software for this purpose, to support learners’ independent learning. Drawing on research on language learning, we used a number of principles that then informed the design of the programmes. In this paper, we reflect on the applicability of the principles and the difficulties in structuring an application for an agglutinative language.

Introduction

ZuluFootnote1 is the most spoken mother tongue in South Africa, spoken by over a fifth of the population. Zulu is the mother tongue of the vast majority of people in the province of KwaZulu-Natal. According to the website South Africa Info, 78% of people here speak Zulu. It would therefore make sense if this was prioritised as the first additional language (FAL) of the rest of the people in the province. And indeed, since 2014, Zulu has been a compulsory subject for non-African language speaking students at the University of KwaZulu-Natal – yet requiring completion of only one course; hardly enough to learn the language. One could even argue, as does Apter (Citation2017) in her review of Sanders (Citation2016)’s Learning Zulu, that ‘the process of learning Zulu will be as an act of reparation for a foundational violence built into South Africa’s violent heritage of colonial oppression and apartheid’ though ‘no such reparation is really possible’ (2017, p. 1).Footnote2

However, in schools, while Zulu may be offered as a first additional language (FAL), the learners in those classrooms are almost entirely Zulu mother-tongue learners. The lack of learners who take Zulu as their actual first additional language likely has something to do with the history and priorities of South Africans, as well as lack of primary school teachers of Zulu. However, we came to realise that the teaching on offer may also not facilitate the learning of Zulu. In fact, it may provide experiences not dissimilar from those described by Tappe (Citation2009), who writes about being taught Zulu phrases without knowing which part of an utterance was the subject, etc., also making memorisation difficult (p. 85).

Though Zulu is so widely spoken, the novice learners of Zulu as a FAL generally have not attained a degree of proficiency that would allow them to learn from interactions in Zulu (see also Rienties, Lewis, McFarlane, Nguyen, & Toetenel, Citation2018). The common extended use of text with novice learners may also be questionable, since the orthographical features of Zulu make reading difficultFootnote3 (Land, Citation2016). As the written language does not indicate the tonal aspect of Zulu, pronunciation cannot be determined from written language. Further, using eye tracking to study adult readers of different languages, Land concluded that ‘isiZulu text takes more time to read than text in other alphabetic languages for which data is available’ (2015, abstract). Probert and de Vos (Citation2016)’s work on word recognition in Xhosa/English bilingual learners agrees that reading skills are specific to the language.

One of us began to confront these issues when she set out to learn Zulu and simultaneously assist her primary school children to do so. There were textbooks available, but while they helped with grammar and vocabulary, they did not help with pronunciation and developing communication skills in the language. The books in Zulu were targeting mother tongue speakers learning to read, not FAL learners needing to learn the language. Books for adults typically started by introducing all the noun classes, generating a hurdle rather than facilitating entry into the language (more on this below). In addition, the electronic apps we found provided soundtracks but used translation to convey the meaning of Zulu terms. This approach does not seem to work very well, as also discussed below, and it failed to capture the attention of the children.

After several years of Zulu teaching in school, in grade 5, the children could still only recite a few songs and say ‘sawubona’ (hello), ‘unjani?’ (how are you?), and ‘igama lami nguZandi’ (my name is Zandi). In addition, they were demotivated. They confused subject markers and other prefixes (as was also found by Wildsmith–Cromarty, 2003). Clearly, we needed something that allowed learners to develop Zulu communication skills and knowledge of the language more quickly, help them retain it better, and keep them motivated, without requiring substantial teaching time or expensive resources. It was with this background that we set out to interrogate principles for FAL learning, and to use this to develop game-like programmes that would facilitate fun learning of Zulu, to supplement classroom instruction. We hasten to say up front that we are not experts on second language acquisition. Rosanne is a computer scientist who oversaw the technical implementation, and Iben works in mathematics teacher education. Hence, we enlisted the help of Professor of Zulu at the University of KwaZulu-Natal, Noleen Turner. She checked that all grammar was correct, and that all phrasing followed a standard format.

In this paper, we reflect on our experiences with the developmental process. Thus, the paper provides a case of the development of a simple game-based prototype for a Zulu-acquisition application for use by grade 3-6 learners in school or at home, with a focus on the questions: (i) How do key features of Zulu impact the structure of the learning experience we can provide in a computerised game for primary school learners? (ii) What would be reasonable guidelines for an application of this nature, based on previous research? (iii) How well did the prototype work, including, how well did it engage the learners?

In what follows, we work towards specifying the requirements for the application. We first review some of the literature around language learning and computer assisted language learning (CALL) and engage previous research on approaches to second language learning (research question ii). Next, we discuss some features of Zulu which we found necessary to consider in order to make decisions about the structure of the learning experience we attempted to provide through the games (research question i). Against these backgrounds, we consider some of the existing CALL apps and argue for the guidelines we used for the development of the programs (research questions i and ii). Finally, we describe the process and outcomes of developing the games and the results of testing the prototypes with learners (research question iii).

Literature review

Database searches on ‘computer assisted language learning’ and ‘African’, ‘Africa’ or ‘agglutinative’ led to very few results. More articles were found on ‘learning’ and ‘agglutinative language’, on ‘computer assisted language learning’, and on ‘game-based’. In the following, we briefly touch on what we have drawn from previous research. We have excluded learning impairment studies, research on automated speech recognition, and studies of location-based mobile learning.

Of the three articles on computer assisted language learning of African languages, one was from 1989 and upon reading was deemed outdated. Runyakitara is a Bantu language that may fall into disuse because of socio-political factors such as emigration, and hence Katushemererwe and Nerbonne (Citation2015) saw a need to enhance the knowledge of grammar and the written language of learners with ‘mother tongue deficiencies’. This use of CALL to preserve endangered languages has also been discussed by Ward and Genabith (Citation2003). Katushemererwe and Nerbonne found their CALL system useful. In terms of focus of the system, they emphasised nouns because of the (proclaimed) difficulties in learning the various noun classes in Bantu languages.

Most of the studies we located were equally positive about the effects of using CALL, though a review of over 350 empirical studies found only limited evidence of efficacy of technology use in foreign language learning (Golonka, Bowles, Frank, Richardson, & Freynik, Citation2014). Exceptions were automatic speech recognition and the use of ‘chat’, which they claim had a measurable impact (Golonka et al., Citation2014). However, automatic speech recognition is particularly challenging in agglutinous languages (Li, Pan, Zhao, & Yan, Citation2013), and hence was not considered here.

Studies about game-based systems were also generally positive, but some results indicated that learning a second language was better without the games, and that the gamed-based CALL worked best in the beginning (Chiu, Citation2013), or that blended learning leads to better all-round language learning (Wold, Citation2011). A fair assumption is that while a CALL environment can be designed to support learning, the learning itself will always be co-created through the learners’ interactions with the software and other agents (as also taken up by Sun, Citation2017). However, we cannot assume that classroom activities during Zulu teaching in South African schools focus on meaning-based activities; rather, this teaching tends to follow a more structural approach to language teaching (cf. Tappe, Citation2009; Wildsmith-Cromarty, Citation2009).

Using computer games as the medium, a South African study found that resource-deprived learners learned more and that the preferred game type varied with learners’ background (Herselman, Citation1999). A more recent study from China on game scenarios found that learners improved regardless of the presentation modality (text, text with graphics, and context) but that the learning was related to learners’ cognitive style (Chen, Chen, & Chien, Citation2017). Game-based learning may be particularly useful for learners with high anxiety levels (Yang, Lin, & Chen, Citation2018), while competitive elements were found not to be related to learners’ learning gains, although it could facilitate learners’ motivation (Vandercruysse, Vandewaetere, Cornillie, & Clarebout, Citation2013).

Students are not fooled by the game-based CALL systems, in the sense that they perceive it as a learning environment (Vandercruysse et al., Citation2013). This may also explain why CALL vocabulary instruction works better over the short term (Chiu, Citation2013), or perhaps it has to do with the nature of the games and the built-in variations.

It is difficult to draw guidelines for the practice and development of our applications from these studies, but it still appears to be widely accepted that CALL must be based on theories of second language acquisition (SLA) and on sound pedagogy. Liu, Moore, Graham & Less (2002) list several references for this in their review of research on CALL up to 1990. They also suggest that the majority of previous studies focused on the learning of written communication skills (ibidem, p. 259).

Hence it was necessary to consider what the literature says about the advantages and disadvantages of approaches to SLA, with their different emphases on communicative practice, syntax, vocabulary, and grammar. Before we do so, we hasten to say that aspects of the different approaches may be highly appropriate as supplementary teaching in a classroom with a Zulu teacher – such as vocabulary practice – but our purpose was to construct more of a stand-alone application, and the following considerations are based on this premise.

Recognising that full immersion is rarely a possibility, we will only consider approaches relevant to systematic instruction. The approach to language teaching has varied over time, and different approaches are still in use, meaning that there is not one accepted method of SLA. For instance, McLaughlin lists four main approaches to SLA from the last 100 years:

The grammar-translation approach, with a focus on learning rules of syntax, memorising vocabulary, and translation into the learners’ mother tongue.

The direct method, where oral communication is emphasised, reading and writing only learned later, pronunciation is stressed, and grammar is learned inductively. Translating is rejected.

The audio-lingual method, which is similar to the direct method but stresses more repetitive drill and practice with patterns.

The humanistic approach, which focuses on the needs of the individual learner (McLaughlin, Citation2012: 6)Footnote4

The grammatically-informed syllabus is in crucial ways discordant with natural language acquisition, Krashen (Citation2013) argues. Research suggests that SLA appears to follow many of the stages and processes of mother tongue learning. For instance,

[Harris] proposed that each human languge is a self-organizing system in which both the syntactic and semantic properties of a word are established purely in relation to other words, and that the patterns of a language are learned through exposure to usage in social participation (Ellis, Citation2012:194).

Based on this research, learners should develop basic interpersonal communication skills (BICS) before cognitive/academic language proficiency (CALP), which is more agreable with the direct approach.Footnote5 BICS tends to imply more natural modes of language versus the more formal modes of academic or written language, with meaning in natural languages being more context-dependent and thus more approachable for someone without linguistic competency, as other things such as body language can be decoded for meaning (cf. McLaughlin, Citation2012: 8). As a computer programme cannot provide actual social participation, mimicry thereof must be considered. Indeed, using an interactive game to teach German, Neville, Shelton, and McInnis (Citation2009, abstract) found tentative results that the ‘contextualised, immersive role play may have helped students to learn’.

While we were aware that adults may need awareness of ‘rules’ of the second language in order to acquire it succesfully (Amaral & Meurers, Citation2011, p. 4), and that it may be useful to introduce such rules after the establishment of BICS, we assumed that implicit or inductive learning of grammar would suffice for learners in the introductory stages, that is, ‘exposure to usage’. We also assumed that without immersion in a community speaking Zulu simplified to facilitate inclusion, or the presence of a ‘language parent’, learners with other mother tongues would struggle to acquire the language because of its agglutinative nature and its large number of noun classes with related verb variations. Therefore, we deemed that some attention to grammar was necessary in the construction of a course or an app – without this implying that grammar must be taught explicitly. This would also imply a principled selection of what to include.

As Ellis (Citation2012, p. 196) suggests, ‘language learning involves statistical knowledge, so humans learn more easily and process more fluently high frequency forms and ‘regular’ patterns’. He claims that research in psycholinguistic research has shown that all aspects of language are ‘sensitive to usage frequency’ (ibidem), including comprehension and syntax. It therefore makes sense both to choose linguistic constructions which are more frequent in the natural language, and to make sure these are repeated. This would also apply to vocabulary; 80% of everyday spoken and written English can be understood with a vocabulary of 2000 words (Cervatiuc, Citation2008), and we have been told that something similar applies to Zulu (personal communication).

Research on second language learners and children learning languages in general indicates that children tend to use semantically general verbs (go, put, give, do, make) rather than more specific words, and that they rely more on adverbs than on more subtle changes of verbs to identify tense (studies summarised by Ellis, Citation2012). Applying this to the teaching of Zulu, it would make sense to introduce adverbial markers of tense rather than verbal prefix constructions. For instance, using ‘manje’ (now) rather than the prefix ‘se-’ which carries more or less the same meaning.

However, there is one difficulty using general verbs in Zulu. For instance, the language makes a distinction between ‘go’ and ‘go to’ by using different verbs (‘-hamba’ and ‘-ya-’, respectively). Other verbs also have the prepositional component ‘implied’, such as ‘-vela’ which means ‘come from’ or ‘originate from’. Thus, what in English is mostly conveyed by the use of a preposition is sometimes conveyed by the use of a different verb in Zulu.

A second difficulty is that the English verb ‘be’ does not exist in a similar form in Zulu; instead, a range of very different constructions have to be used (see ). Nonetheless, it makes sense to start with more general verbs in Zulu teaching, and therefore also in a game for Zulu SLA.

Table 1. The constructions conveying ‘be’ in Zulu.

There is limited research on the acquisition of Zulu, but some consideration as to the ways in which Zulu children acquire the language was deemed highly relevant, and these are discussed in the next section.

A further distinction has been made between task-based and form-focused language instruction. According to Arslanyilmaz (Citation2013), task-based instruction provides a context and associated task that activates meaningful engagement and thereby learning, whereas form-focused instruction draws learners’ attention to linguistic elements. Form-focused instruction may do so through a focus on meaning, but the obvious task for the learner is to learn the language. Arslanyilmaz’s study compared task-based with form-focused instruction and found the former to be more effective. However, he does summarise previous work and suggests that that the two approaches have different strengths (op. cit.: 304), as well as acknowledges that the findings may depend on the particular setup of the form-focused instruction (op. cit.: 316).

In summary, the research pointed us to a task-based direct approach, using most common vocabulary and fewer agglutinative components, as a first answer to research question ii. We now turn to the specific challenges this provided for the Zulu language.

Considering some challenges with learning Zulu

Zulu is in the language group ‘Bantu’ languages after ‘abantu’ meaning ‘people’. Of course, it shares some grammatical features with a range of other languages, so here we particularly consider the features that are different from English and Afrikaans – the most likely mother tongues of FAL Zulu learners in KwaZulu-Natal.

First, Zulu is an agglutinative language, where words are formed by joining prefixes or suffixes to the stem. Everyday Zulu often combines a substantial number of morphemes to the stem, connecting object pronoun, subject pronoun, dative object pronoun, and verb with other components into one word. For instance, ‘they slaughtered a goat for me’ could be translated into ‘imbuzi bangiyihlabela’ (see ).

Table 2. The construction of ‘bangiyihlabela’ with translations and explanations.

This suggests that more careful attention to sentence structure is necessary when selecting content for lessons whether in class or in an app.Footnote6 Indeed, this has also provided challenges to attempts to automate morphological analysis of Zulu (Pretorius & Bosch, Citation2003).

Second, similar to Swahili, Zulu has a fair number of noun classes,Footnote7 with corresponding verb prefixes or ‘concords’ as they are sometimes referred to. below gives some examples, with the prefixes in bold.

Table 3. Examples of simple sentences where the verb prefix varies with the noun class of the subject noun.

The noun classes were originally, to a large extent, semantically informed – that is, they were reflective of the meaning of the words. For instance, the ‘i-/ama-’ class was used for items that tend not to occur alone in nature – such as eyes, shoulders, eggs, or stones.Footnote8 However, as borrowed words enter the language, they get placed into noun classes more on the basis of their pronunciation, leading to blurring of the original distinctions – such as with ‘ikati’ (cat) or ‘iphoyisa’ (a police officer). Thus, knowing which prefix to use requires more than pattern recognition; it requires some familiarity with the language. These two things suggest that it would be overwhelming to include all noun classes from the beginning of a course; that it would be more effective to introduce them gradually; and that introducing nouns where meaning and noun class are coherent first would be preferable. A study by Suzman (Citation1991, here based on discussion in Zawada & Ngcobo, Citation2008), suggests that Zulu children do indeed learn some noun classes before others, as well as singular before plural. Zawada and Ngcobo suggest that this has to do with prototypicality, frequency of the occurrence of the word classes in spoken Zulu, ease of acquisition, as well as their degree of abstractness.

Third, similar to English and Russian, Zulu makes a distinction between continuous actions and non-continuous actions, which means that two different past tense constructions often appear in the same paragraph. This comes with the added difficulty that they take the negative in very different ways, through the addition of additional morphemes. Furthermore, there is a short and a long form of each two past tenses – recent and distant past. This indicates to us that the normal narrative use of past tense should likely be avoided in the beginning of a course, and that the past tenses should be introduced gradually much later.

Fourth, there is no simple way of negating statements; it depends on the nature of the sentences. This is connected to the range of ways necessary to express the equivalent of ‘to be’ (see ).

Fifth, that possessives change with the noun class of both the subject and the object of the clause makes this too intricate for most learners to recognise, our personal experience suggests. For instance, ‘their cat’ can be ‘ikati labo’ if we are talking about the children’s cat, but ‘ikati lazo’ if we are talking about the girls’ cat; and if it is ‘their dog’ instead, we get ‘inja yabo’ and ‘inja yazo’, respectively. Because both phonemes vary, these possessive terms are hard for learners to recognise (see discussion in Wildsmith-Cromarty, Citation2009, for more on the complexities of these issues).

There are other features of Zulu that invite recognition of patterns, thus being something to consider actively in the selection and sequencing of content. For instance, the verb stem ‘-funda’ (learn) gives rise to the verb stems ‘-fundiswa’ (be learned), ‘-fundela’ (learn/study for), and ‘-fundisa’ (teach), the nouns ‘umfundi’ (learner) and ‘umfundisi’ (teacher or preacher), and the noun ‘isifundo’ (lesson). We have found no research on whether this facilitates or complicates the learning of the language.

There are several pronunciation challenges for most non-Bantu language speakers in the use of the three ‘clicks’ symbolised by c, x and q, and their variations, ch, xh, qh, gq, and gx. Because the app would potentially be used without the possibility of feedback from Zulu-speaking teachers, we abstained from including words with clicks. Retrospectively, we are not sure this was a wise decision, as the clicks certainly make words distinct, but the original concern remains. We also did not address the issue of tone in the language, which means that the same word may carry different meanings depending on tone (something well known from Mandarin but not given much attention in Zulu teaching materials).

Before we explain how we approached the task of producing our own CALL package, we want to cast a quick glance over the existing types of CALL applications we have encountered.

Types of existing language apps

There are several different applications available for language learning in general (not in Zulu). McLaughlin makes a distinction between three types of applications depending on whether their focus is:

listening, speaking, and pronunciation;

reading and writing; or

grammar, vocabulary, and data-driven learningFootnote9 (McLaughlin, Citation2012).

These are what Arslanyilmaz refers to as form-focused, so to the above list we could add a category more in line with the humanistic approach:

task-based instruction (Arslanyilmaz, Citation2013).

We focus on comprehension, which may include reading and writing, but not in isolation, so McLaughlin’s categories seem to us to reflect a somewhat artificial distinction. On the other hand, the notion of task-based instruction in CALL adds a more meaning-focused and contextualised approach to learning. We looked at the extent to which these categories are reflected in some examples of CALL applications, and since there is not much to choose from for Zulu, we included applications for teaching SwedishFootnote10.

An example of an application which supports listening, speaking, and pronunciation is the WordUplite’s ‘record’ function, where you can listen to a native speaker saying a word or phrase in Swedish, record yourself doing the same, and then compare the two sound tracks. However, the rest of that application appears to rely strongly on translation of words or phrases to teach meaning, and while they are thematic around topics such as food or greetings, they do not appear to give a systematic introduction to the language, nor do they expect learners to generate language to solve a task. Thus, the application focuses on listening, speaking, pronunciation, and vocabulary, but is neither data-driven nor task-based.

This is similar to Hello South Africa, which shows a word in English together with the Zulu translation and an option to hear the word pronounced, but without the option to check your own pronunciation. It is a phrase book only and is not structured to take learners gradually through sentences of similar structure to provide the frequency that Ellis (Citation2012) claimed to be so important. Thus, this is also neither data-driven nor task-based but focuses on listening and vocabulary. The same is the case for the online introductory Zulu course from UNISA, recently supplemented by an integrated e-dictionary (Faaß & Bosch, Citation2016).Footnote11 These apps therefore limit the learners’ opportunities to create new sentences, and thereby, in our view, do not provide a good entry into the language.

A very popular app is Duolingo. This too is based on translation and targets adults and older learners. It includes sections where the user must repeat sentences into the microphone, but our testing of the app suggests that the pronunciation is not checked. A strength of the app is that it provides the exposure to frequency that Ellis (Citation2012) stressed, through repeated use of vocabulary and syntax. We consider this an approach that combines several of those listed above.

None of these are games, unlike Swedish BB which is a game in which learners match English words with words in Swedish, but with no real variation in the game itself, thus making it unappealing to younger learners. We consider this an example of a vocabulary-focused application.

A different approach is taken by Swedish in a Month which uses pictures only to introduce new words and simple sentences. There is no translation at all, which at times can give rise to misinterpretations (e.g. is fågel a bird or an eagle?), and thus would probably be best used in the presence of a teacher or native speaker. After six examples of new vocabulary or sentences, the same six examples are tested in a simple matching exercise. There is no variation in this ‘game’ component so while the level of challenge it provides appears to be just right for middle school learners, it quickly gets boring and the learners skip the lessons to do the matching exercises through educated guess work (personal observation). On a positive note, the progression is fast yet systematic and gradual, with new sentence constructions being introduced rapidly, and always in context. Though it is not really a data-driven learning programme, the systematic introduction of new terminology that is then used in new iterations of sentences does assist the learners in some pattern generalisation. This, therefore, is an example of a CALL application in the last of McLaughlin’s three categories. It is not a task-based application; the sentences are not contextualised and are clearly constructed to demonstrate the structure of the language rather than support the learner in generating language in connection with completing a task.Footnote12

While this is in no way an exhaustive review, we found most of these applications to be either little more than interactive phrasebooks or based on a grammar-translation approach. Of the ones we looked at, only Swedish in a Month used something that could resemble a more direct approach. This seems in line with the claim about most second language teaching made by Krashen:

In nearly all foreign and second language classes, there is a ‘rule of the day’ as well as vocabulary that students are expected to focus on, often referred to as ‘target’ grammar and vocabulary. In traditional pedagogy, exercises are aimed at the conscious learning of this targeted grammar and vocabulary. They are also included in brief readings, which are generally packed with the targeted items. (2013, p. 102)

In addition, the applications we found were not ‘fun’. The two that included word matching (Swedish BB and Swedish in a Month) did not vary the activity – though the latter tended to have some bizarre and therefore fun examples, such as a plate on a clothes line for the word for ‘clean’. The learners who tried out these applications for us tired of the games quickly.

Clearly, simple-vocabulary CALL applications are the simplest to construct, but they remove the language from its normal context and use. In Zulu, there is the added difficulty that the agglutinative nature of the language can make it hard to separate out the meaning-bearing components. Creating task-based CALL applications requires an additional dimension.

Based on these explorations, we formulated a series of criteria for the applications we had in mind, within the practical restrictions surrounding the process.

Our approach to development of the content of the app

The key decision was to go with a direct method approach, teaching listening and vocabulary as well as grammar, though the latter only implicitly, through a data-driven component. The complexity of working with voice recognition software and the explorative nature of the project meant that we avoided speaking and more task-based content.

Based on our understanding of Zulu, as discussed above, we therefore made some general choices about the selection and sequencing of content (which constitute an answer to research question i):

Adding noun classes gradually, starting with noun classes that describe concrete objects and introducing singular before plural (cf. Zawada & Ngcobo, Citation2008).

Working from simple nouns to subject noun + verb and then on to subject noun + verb + object noun.

Using the most commonly used words as far as possible.

Working in present tense only.

From our understanding of second language learning, we further decided to implement the direct method approach as far as possible through:

Limiting the use of translation, using instead pictures to convey meaning.

Including spoken language if possible.

Focusing on common language on topics to which learners can relate, and which they can use communicatively.

Making it fun and appealing, with some inbuilt variation.

Building in non-trivial repetition of vocabulary and sentence construction.

Not necessarily based on research, Chapelle (1998, here quoted in Liu et al., 2002: 256) suggests seven criteria for developing multimedia CALL:

Making key linguistic characteristics salient.

Offering modification of linguistic input.

Providing opportunities for comprehensible output.

Providing opportunities for learners to notice their errors.

Providing opportunities for learners to correct their linguistic output.

Supporting modified interaction between the learner and the computer.

Acting as a participant in second language learning tasks.

We adhered to the first of these by starting with one noun class only, so that the pattern of noun + verbal prefix could stand out. We also considered the other noun classes but were limited by the programming expertise available. In particular, we wanted the learners to have more input into the programme than always just choosing the right option from a limited list. Of course, as Amaral and Meurers (Citation2011) have pointed out, it is difficult to constrain the learner input into the application so that it can be processed effectively – in our view something which may also limit the options for task-based CALL. It was therefore necessary to construct the activities accordingly. Similarly, there was a limit to how much and how accurately the system could provide feedback, in particular given our desire to avoid a direct grammatical rule focus. As a start, we landed on simply not accepting incorrect responses and allowing learners to try again, while recognising the obvious shortcomings of this choice.

Development and preliminary testing of the products

Four BSc Honours students in Computer Science were approached to develop a series of games and program the prototypes, based on the guidelines described above, together with a structured list of words and sentences to be introduced over time.Footnote13 Two of the students managed to produce prototypes for different age groups, and are included as collaborators on this paper. The other two did not manage to complete prototypes and their work has not been considered here.

The guidelines were derived from the review of previous research, including research on approaches to SLA, but with considerations of the language itself. The literature did not give us a basis for choosing any particular type of games – indeed we had found literature that indicated that the reception of games varied amongst learners – nor could we be guided by the literature in the actual software design. While the literature suggested that learning from a game-based application was not a function of the modality used, we felt that a visually appealing application would be more motivating for the learners, and we included this as a requirement for the programmers. Given the uncertainty about the contexts of use, we also asked for the applications to be easy for young learners to use independently.

One student programmer focused on simple vocabulary for grade 4 learners, or beginning Zulu learners, in an application created using Action Script 3. Action Script was selected as it provides a means of getting a graphic-rich application that requires little specialised software for the end user computer. The user simply needs a browser and an Adobe Flash Player to access the application. The game worked with levels that had to be mastered to move on, much like most entertainment games with which the target group was likely to be very familiar.

Each level had four different games, the first of which actually taught the new nouns through pictures accompanied by sound and written language. Unlike our original intention, not all the nouns came from noun class 1 (mostly used for people) but included well known domestic animals as well (two additional noun classes) – a pragmatic choice by the programmers that we accepted for the prototype.

The games included the well-known hangman, which meant that some spelling was also being tested. This was not an aspect we had actively planned for, but which, given the emphasis in many South African schools on written language, may be a feature that leads to a more positive reception by teachers and school management; though it may be appropriate for a later stage in the learning process.

All four games used the same underlying content and thus learners were given ample opportunity to notice their errors and improve. The games were scored and hence the user had direct feedback and motivation. The variation in the games and the way they were presented limited the boredom factor. An objective of all the games was to provide an opportunity for repetition of tasks without losing the appeal. Progressing through the game allowed the user to move up in ranking, also a progression mechanism well known in commercial entertainment games – in this case from herd boy through to chief (). Female parallels were decided to be added to the final version of the application after the girls in a test group complained!

To test the prototype (in order to answer research question iii), we asked teachers in nearby schools if they would assist, and thus created a convenience sample of grades 3 and 4 learners from a historically advantaged English-medium school. This choice was not informed by previous research within CALL; we simply based the choice on a premise that the test of the prototype should be completed by learners from the target group. The extent of the test was determined by the time made available to us by the school.

Learners tried the programme in a half-hour session, after which they provided written feedback on their experience in a small questionnaire with both open and closed questions. The games were generally well received; all learners were motivated by the scoring scheme and played the same game repeatedly until they felt they had achieved a high enough score. Incidentally mother tongue Zulu learners found the games as interesting as the other learners, because they had generally not previously seen the written form of their language.

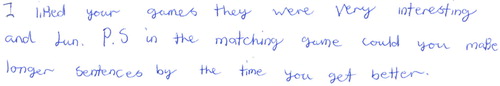

As this learner indicated (), even a grade 4 learner recognises the need to move from single words towards longer sentences to be able to acquire a language!

The second programme worked more with simple sentences, introduced and tested through visuals, using MS Visual Studio 2010 Express Edition, C#, Monogame 3.0.1, and OpenTk 2010. This was the student’s personal preference as he felt more comfortable with this technology. As the programmes were written as a proof of concept application, we did not want to hinder the potential development by forcing a particular technology on the student. We were more interested in what could be achieved in the given time frame and how learners would respond.

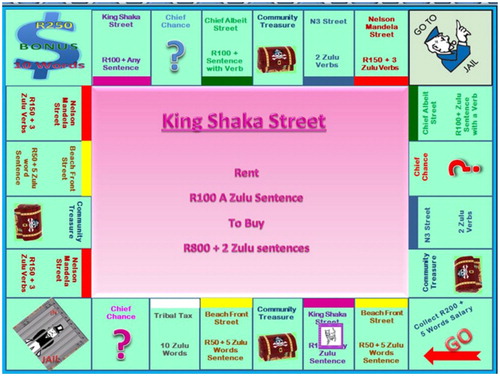

The student had worked hard to come up with new game formats. The first was a memory game where learners had to match pictures and words; the second was a picture-recognition game where the learners had to type in a sentence to match a photo that slowly faded into visibility; a third was ‘word make’ where learners made words by shooting down balloons; and the most complex, a ‘word monopoly’ (see ). This game used the other three games to earn monopoly money, as well as a ‘word tile puzzle’ where learners had to construct a sentence using provided ‘word tiles’. There was some use of translation to provide target sentences, etc., despite our previously stated preferences.

The prototype was tested on 22 grade 6 learners at a nearby school, all of whom were Afrikaans mother tongue speakers with English as their second language, and who had one scheduled Zulu lesson a week. The test spanned a 90 minute period and ended with the learners completing a short questionnaire. 20 of the learners felt that the session helped them learn Zulu, while 2 were not sure. The popularity of the games varied among learners, but not substantially enough to say that one game was preferred above others.

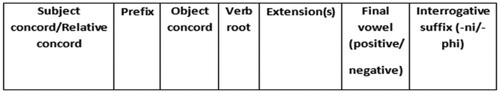

Two additional Honours students were involved in the project. One intended to construct a Zulu sentence constructor, to give learners experience with dialogue, but the student did not manage to complete a usable product. The other was working on a Zulu grammar tutor, which was meant to give learners practice in picking the correct prefixes as they moved between singular and plural, used simple possessives, and changed positive present-tense sentences into negative present-tense. This student worked with a verb morpheme scheme that was potentially useful in informing the programming (see ). However, he appeared unable to move away from the idea of introducing a rule that learners could then ‘test’ themselves on. Neither of these attempts met our requirements and therefore are not discussed in more detail.

The difficulties encountered

Technical challenges and considerations

The nature of the applications required several diverse skills from the student programmers. They were required to develop a graphical interface that was picture-rich and sufficiently intuitive for young learners to use independently. This in itself was a challenge as the students had only previously designed user interfaces for adults. Furthermore, the applications had to be captivating enough to retain the young learners’ interest and provide motivation to continue with the task. For this the students had to go beyond their formal training and develop games that would allow for the desired content to be presented in such a way that it would capture and hold the user’s interest, despite the required and necessary repetitiveness of the task. The biggest challenge was developing a data structure that would enable the structuring of game content to enable the randomness of the ‘Zulu material’ within each level, as well as provide a means for administrators of the programmes to add new content at each level. This task became more complex as more language concepts were introduced.

In retrospect, an application that can be accessed from an Adobe Flash Player enabled browser is more desirable than a standalone application as the former requires minimal user installation. The system that was developed using Action Script required little installation effort at the testing site, whereas the other application required considerable installation time at the testing site that probably limits the potential user-base of the system. It is intended that further development of both systems will continue, and that they will be integrated to form a cohesive Flash product that can be made available for young learners to develop their Zulu language competency in a fun and interactive way.

The actual versus the intended approach

The resulting games mostly minimised the use of translation and there were no complaints about this from the learners. The programmers had managed very well to choose common language and topics to which learners could relate, but the applications did not sufficiently support learners’ communicative use of the language.

Also out of reach within the time span and expertise of these otherwise skilled programming students, was to offer modification of learners’ input, more subtle ways of directing learners to notice their errors, and providing guidance for learners to adjust their input. This is something that could be refined but requires a substantial set of sub-routines in the programmes that can recognise the type of learner error in relation to the level of the game and the learners’ previous errors, and provide a range of different types of support, feedback, or hints.

On the other hand, the apps were very successful at building in non-trivial repetition, through a range of games, which changes the way that learners must interact with the (same) content. For both apps, this seemed to make the app fun and appealing to the learners, as had been intended.

No grammar was made explicit in the apps, in agreement with our intentions. Both apps managed to make some key characteristics of Zulu stand out through the simple combinations of nouns and verbs.

In relation to developing an app for Zulu, with its particular linguistic features, the resulting apps were promising, but some of the language issues we engaged earlier in this paper were not addressed in the app prototypes, so this would need further attention in the future.

As discussed earlier, we preferred a task-based approach where tasks were introduced in context. The contexts of the two prototypes were mostly games, not contexts that could lend meaning to the content per se. We hypothesize – more we cannot do based on experiences from two applications – that in the early stages of learning, pseudo contexts in a game setting may be as effective.

Concluding remarks and discussion

In trying to select and sequence content for the games, we considered the characteristics of Zulu regarding word frequency, the 14 noun classes, the corresponding prefixes, as well as the agglutinative nature of the language and the resulting morphology. We argue that this must be considered carefully in the selection and sequencing of content, so that any application (and indeed any instruction) is built around the nature of the language and what we know about its acquisition. This is not new or unique to Zulu, but this case constitutes the first example of trying to interpret what this means in practice.

Based on existing research, we suggested a set of guidelines for the application, listed previously. Prototypes for two applications for the acquisition of Zulu vocabulary and basic sentence construction were developed based on principles derived from the structure of Zulu and literature on SLA. The prototypes were tested on two convenience-sampled groups of learners, in a single and a double lesson respectively, followed by feedback from the learners. Both applications need to be developed further and tested more widely, but current reflections indicate that the applications can serve as powerful resources to assist with the acquisition of Zulu vocabulary and basic morphology for young learners.

The experiment bodes well for trying to teach Zulu with the supplementary use of games, and based on a direct language approach. Though it requires good understanding of the language to structure a course so that key characteristics emerge from the direct language approach, this appears to make the language more accessible (as also suggested by Arslanyilmaz, Citation2013; Krashen, Citation2013). Given how often people have been taught Zulu with a grammar-translation approach and have found the language too difficult, this is a promising result.

In response to our questions stated in the background section, we would say that it is possible to work around some of the more difficult key features of Zulu to construct a meaningful and fun introductory learning experience in a computerised game for primary school learners. However, the prototypes were not developed far enough to confront the issues of different ways of expressing ‘be’, the addition of several morphemes to the verb stem, the complexity of tenses, the complexity of negations in Zulu, nor the double conjugation of possessives.

In particular, we adhered to the research results on the learning of Zulu children as summarised by Zawada and Ngcobo (Citation2008), starting with the noun classes the Zulu children acquire first, working from prototypicality and frequency of use, as well as using words with a low degree of abstractness. We would encourage others attempting to develop CALL of languages with many noun classes to follow this approach.

Based on the literature review, we put together a list of guidelines for an application of this nature, which seemed reasonable. The guidelines – which we listed previously in the paper – included some principles that concerned the selection and sequencing of the content and some general principles for CALL. Both sets of guidelines worked well, though it proved difficult to make the content task-based using meaningful contexts. These instead were game contexts, which were well received by the learners. The programmers were able to develop the apps according to these guidelines, which indicated that the guidelines were sufficiently specific to lead to successful implementation by programmers.

All in all, the prototypes were positively received by learners and learners progressed well over the short time of testing. This points to further possibilities for the development of computerised support for the direct learning of Bantu languages, rather than using translation of words and phrases as in existing Zulu applications. And while this is no major contribution to restoring constructive inter-cultural and inter-racial relations in South Africa, it is a small step towards bridging cultural language groups and thereby furthering respect between the members of the younger generations. You cannot know the good within yourself if you cannot see it in others. ‘Inkunzi isematholeni’.

Notes on contributors

Iben Maj Christiansen is an associate professor of mathematics education at Stockholm University, who previously lived and worked in KwaZulu-Natal. During this period, she tried hard to learn Zulu and to assist her children in doing the same. It was frustrations with this process which resulted in the idea of computer-assisted Zulu learning. In her regular work, she researches the learning of mathematics student teachers and novice teachers, and mathematics teacher education.

Rosanne Els is a lecturer of computer science at University of KwaZulu-Natal, with a keen interest in education. She oversaw the programming of the apps, which was carried out by Honours students under her supervision. Currently she is considering developmental projects of integrating computer science in mathematics education.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Professor Noleen Turner from the University of KwaZulu-Natal’s isiZulu Department who assisted with the accuracy of the Zulu content and commented on an early draft of this paper. Her input as language specialist was invaluable. We also want to acknowledge the University of KwaZulu-Natal’s Language Board which provided funding for the project.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1 After consulting with language experts, we have opted to use the term ‘Zulu’ to refer to the language of the amaZulu, rather than isiZulu which is the correct Zulu term for the language. We also note that we are well aware that there are many different forms of Zulu spoken in the country, depending on region and education of the speaker.

2 In a roundtable discussion, Lucy Graham made the point that a reason for learning Zulu amongst – as she puts it – white people could be ‘a performative enunciation of mastery, the claim to understanding, knowing, Zulu people’ (Dlamini et al., Citation2016, 829). The issue is obviously complex, in the context of the South African history.

3 A main feature is the agglutination which results in a conjoined writing system and hence in words that are both long and complex. As Land (Citation2016) points out, Zulu also contains a high rate of recurring strings of particular letters, which – we add – may not always carry the same or even similar meanings.

4 Wildsmith-Cromarty (Citation2009, p. 112) claims that the literature on multilingualism and second language development has moved towards a stronger focus on learner agency as well as identity negotiation. We would consider this in line with the humanistic approach of McLaughlin.

5 Though other views obviously exist, such as the sentiment of Laurillard (Citation1991): “The general conclusion of this section is that the communicative approach, with its reliance on induction as the principal means of learning linguistic forms in the target language creates too great a cognitive load for most learners. … We conclude, therefore, that the classroom learner will be better served if we preserve the complexity that language competence entails and the communicative methodology is supplemented by CALL programs which use a didactic method, where the underlying grammatical rules are taught explicitly …” (pp. 147–8)

6 A study of beginning level students of Zulu at higher education in the UK suggests that pre-existing knowledge of a language with a similar structure to Zulu was positively related to students’ self-assessment of progress (Marten & Mostert, Citation2012).

7 According to Zawada and Ngcobo (Citation2008), 16 of the 23 generalised Bantu noun classes exist in Zulu, but only 14 of those are represented, the last two being diminutive noun classes which use a suffix instead of a prefix in Zulu.

8 Another way to describe these two noun classes is that the former refers to “natural phenomena, animals, body parts, collective nouns, undesirable people, augmentatives, derogatives” with plurals in the latter noun class which also includes “mass terms and liquids, time references, mannerisms, modes of action” here from (Zawada & Ngcobo, Citation2008, p. 318), who base their overview on (Canonici, Citation1987) and (Hendrikse, Citation2001).

9 “Data-driven learning” refers to, McLaughlin explains, helping learners notice patterns in the language, for instance by showing a word or phrase in a range of examples (McLaughlin, Citation2012: 9).

10 Amongst the EU countries, Sweden takes in a substantial number of asylum seekers. It thus faces the challenge of teaching Swedish to a significant number of people with very different language backgrounds. Add to this that Sweden is highly digitalised. Thus, we would expect there to be some attention to CALL applications for the learning of Swedish. Since the first version of this paper was written, an interesting new addition to this has been an app which connects newly arrived people with first language Swedish speakers so that they can engage in real conversations.

11 UNISA is the University of South Africa. The course is available on http://www.unisa.ac.za/free_online_course/zulu/zulu.html.

12 Consider, for instance, a phrase such as ‘a glass of green water between boots’.

13 Students in the BSc Honours programme at the University of KwaZulu-Natal must construct a programme which meets the requirements of a ‘customer’ as part of their project-based learning. The first author took the role of ‘customer’ to the students, and the second author supervised the projects.

References

- Amaral, L. A., & Meurers, D. (2011). On using intelligent computer-assisted language learning in real-life foreign language teaching and learning. ReCALL, 23(1), 4–24. doi:10.1017/S0958344010000261

- Apter, E. (2017). Mark Sanders’ learning Zulu. Safundi, 18(1), 1–4. doi:10.1080/17533171.2016.1255446

- Arslanyilmaz, A. (2013). Computer-assisted foreign language instruction: Task based vs form focused. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 29(4), 303–318. doi:10.1111/jcal.12003

- Canonici, N. (1987). The grammatical structure of Zulu. Durban: University of Natal.

- Cervatiuc, A. (2008). ESL vocabulary acquisition: Target and approach. The Internet TESL Journal, 14(1)

- Chen, Z. H., Chen, S. Y., & Chien, C. H. (2017). Students’ reactions to different levels of game scenarios: A cognitive style approach. Journal of Educational Technology & Society, 20(4), 69–77.

- Chiu, Y. H. (2013). Computer‐assisted second language vocabulary instruction: A meta‐analysis. British Journal of Educational Technology, 44(2), E52–E56. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8535.2012.01342.x

- Dlamini, J., Graham, L., Mangcu, X., Matlin, N., Mokoena, H., Sanders, M., Wenzel, J., & … Oung, R. J. (2016). Roundtable discussion. Interventions, 18(6), 823–833. doi:10.1080/1369801X.2016.1196143

- Ellis, N. C. (2012). Frequency-based accounts of second language acquisition. In S. M. Gass & A. Mackey (Eds.), The Routledge Handbook of Second Language Acquisition (pp. 193–210). Abingdon: Routledge.

- Faaß, G., & Bosch, S. (2016). An integrated E-dictionary application – The case of an open educational trainer for Zulu. International Journal of Lexicography, p.ecw021,

- Golonka, E. M., Bowles, A. R., Frank, V. M., Richardson, D. L., & Freynik, S. (2014). Technologies for foreign language learning: A review of technology types and their effectiveness. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 27(1), 70–105. doi:10.1080/09588221.2012.700315

- Hendrikse, A. P. (2001). Systematic polysemy in the Southern Bantu noun class system. In Cuyckens, H. & Zawada, B.E. (eds.): Polysemy in Cognitive Linguistics (pp. 185–212). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Herselman, M. E. (1999). South African resource-deprived learners benefit from CALL through the medium of computer games. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 12(3), 197–218. doi:10.1076/call.12.3.197.5707

- Katushemererwe, F., & Nerbonne, J. (2015). Computer-assisted language learning (CALL) in support of (re)-learning native languages: the case of Runyakitara. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 28(2), 112–129. doi:10.1080/09588221.2013.792842

- Krashen, S. (2013). The case for non-targeted, comprehensible input. Journal of Bilingual Education Research and Instruction, 15(1), 102–110.

- Land, S. (2015). Reading and the orthography of isiZulu. South African Journal of African Languages, 35(2), 163–175. doi:10.1080/02572117.2015.1113000

- Land, S. (2016). Automaticity in reading isiZulu. Reading & Writing-Journal of the Reading Association of South Africa, 7(1), 1–13.

- Laurillard, D. (1991). Principles for computer-based software design for language learning. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 4(3), 141–152. doi:10.1080/0958822910040303

- Li, X., Pan, J., Zhao, Q., & Yan, Y. (2013). Discriminative approach to build hybrid vocabulary for conversational telephone speech recognition of agglutinative languages. IEICE Transactions on Information and Systems, 96(11), 2478–2482.

- Liu, M., Moore, Z., Graham, L., & Lee, S. (2002). A look at the research on computer-based technology use in second language learning: A review of the literature from 1990-2000. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 34(3), 250–273. doi:10.1080/15391523.2002.10782348

- Marten, L., & Mostert, C. (2012). Background languages, learner motivation and self-assessed progress in learning Zulu as an additional language in the UK. International Journal of Multilingualism, 9(1), 101–128. doi:10.1080/14790718.2011.614692

- McLaughlin, B. (Ed.). (2012). Second-language acquisition in childhood: School-age children. New York: Psychology Press.

- Neville, D. O., Shelton, B. E., & McInnis, B. (2009). Cybertext redux: Using digital game-based learning to teach L2 vocabulary, reading, and culture. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 22(5), 409–424. doi:10.1080/09588220903345168

- Pretorius, L., & Bosch, S. E. (2003). Computational aids for Zulu natural language processing. Southern African Linguistics and Applied Language Studies, 21(4), 267–282. doi:10.2989/16073610309486348

- Probert, T., & De Vos, M. (2016). Word recognition strategies amongst isiXhosa/English bilingual learners: The interaction of orthography and language of learning and teaching. Reading & Writing-Journal of the Reading Association of South Africa, 7(1), 1–10.

- Rienties, B., Lewis, T., McFarlane, R., Nguyen, Q., & Toetenel, L. (2018). Analytics in online and offline language learning environments: the role of learning design to understand student online engagement. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 31(3), 273–293. doi:10.1080/09588221.2017.1401548

- Sanders, M. (2016). Learning Zulu: A secret history of language in South Africa. Princeton University Press.

- Sun, S. Y. H. (2017). Design for CALL – Possible synergies between CALL and design for learning. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 30(6), 575–599. doi:10.1080/09588221.2017.1329216

- Suzman, S. M. (1991). Language acquisition in Zulu, Unpublished thesis, University of the Witwatersrand.

- Tappe, H. M. (2009). My ways to Rome: Routes to multilingualism. In Todeva, E. & Cenoz, J. (eds.).The Multiple Realities of Multilingualism: Personal Narratives and Researchers’ Perspectives (pp. 75–90). Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter,.

- Vandercruysse, S., Vandewaetere, M., Cornillie, F., & Clarebout, G. (2013). Competition and students’ perceptions in a game-based language learning environment. Educational Technology Research and Development, 61(6), 927–950. doi:10.1007/s11423-013-9314-5

- Ward, M., & Genabith, J. (2003). CALL for endangered languages: Challenges and rewards. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 16(2–3), 233–258. doi:10.1076/call.16.2.233.15885

- Wildsmith-Cromarty, R. (2003). Do learners learn Zulu the way children do? A response to Suzman. South African Journal of African Languages, 23(3), 175–188. doi:10.1080/02572117.2003.10587216

- Wildsmith-Cromarty, R. (2009). Incomplete journeys: A quest for multilingualism. The multiple realities of multilingualism: Personal narratives and researchers’ perspectives (pp. 93–112). Berlin and New York: Mouton de Gruyter.

- Wold, K. A. (2011). Blending theories for instructional design: Creating and implementing the structure, environment, experience, and people (SEEP) model. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 24(4), 371–382. doi:10.1080/09588221.2011.572900

- Yang, J. C., Lin, M. Y. D., & Chen, S. Y. (2018). Effects of anxiety levels on learning performance and gaming performance in digital game‐based learning. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 34(3), 324–334. doi:10.1111/jcal.12245

- Zawada, B., & Ngcobo, M. N. (2008). A cognitive and corpus-linguistic re-analysis of the acquisition of the Zulu noun class system. Language Matters, 39(2), 316–331. doi:10.1080/10228190802579718